Abstract

The aims of the current study were to examine the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment on current relationships with parents, and whether the quality of current relationships with parents mediates the associations between childhood maltreatment and psychological health in late adulthood. Using two decades of longitudinal data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, multilevel structural equation modeling was employed to examine the associations between reports of childhood maltreatment, aspects of current relationships with parents (i.e., perceived closeness, contact frequency, and exchange of social support), and psychological well-being/distress of adult children. Key results indicated that reports of maternal childhood abuse and neglect predicted lower levels of perceived closeness with aging mothers, which were subsequently associated with reduced psychological well-being of adult children. We did not find evidence of mediation between reports of paternal childhood abuse/neglect, current relationships with fathers, and psychological outcomes. Our findings suggest a significant linkage between childhood and later-life intergenerational relationships. Adults who were maltreated by their mother as children may continue to experience challenges in this relationship. Further research is needed to examine how these past and current relational dynamics affect caregiving experiences and outcomes. In addition, when intervening with adults with a history of childhood maltreatment, practitioners should evaluate contemporary relationship quality with the abusive mother and help address any unresolved emotional issues with the parent.

Keywords: childhood abuse and neglect, intergenerational solidarity theory, later-life intergenerational relations, psychological well-being and distress

The quality of relationships with parents is positively associated with better well-being across the life course (Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Birditt, 2013; Bengtson, 2001). Adults who have been independent of parental care and protection for many years can benefit psychologically from a positive and close relationship with their aging parents (Fingerman, Sechrist, & Birditt, 2012; Fuller-Iglesias, Webster, & Antonucci, 2015). At the same time, demographic and family changes have extended the years of shared lives across generations, and adult children deal with an increased demand for the long-term care needs of their aging parents (Bengtson, Lowenstein, Putney, & Gans, 2003; Bozhenko, 2011). Prior studies suggest that a higher quality relationship with older parents can help to relieve the burden and strain associated with caregiving, and thus reduce the risk of harmful health effects associated with taking on caregiving roles (Fingerman et al., 2012; Merz, Schuengel, & Schulze, 2009).

Previous research has focused on identifying significant predictors of intergenerational relationship quality (Suitor, Sechrist, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011), although there has been a lack of attention to life course factors that explain how early childhood experiences shape the pattern and quality of relationships with parents in late adulthood. Prior research has also overlooked the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment––a major dysfunction in early child-parent relationships––on later-life intergenerational relationships. A few studies suggest that adults with a history of childhood maltreatment remain connected to their abusive parent and experience challenges in caregiving (Kong & Moorman, 2015; Kong, 2018b), but it is not clear whether and how childhood maltreatment affects adults’ relationship quality with aging parents and subsequent implications for health and well-being. Furthermore, these previous studies focused on cross-sectional associations.

To address this gap in the literature, the current study examined the associations between childhood maltreatment, relationships with aging parents, and psychological well-being and distress in late adulthood. The key strength and contribution of this study is the focus on longitudinal data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) that spans two decades, in order to examine the evidence for continued difficulties in parent-child relationships across the life course and related psychological effects for adults with a history of childhood maltreatment.

Theoretical Framework: The Effects of Parental Childhood Maltreatment on Later-Life Intergenerational Relationships

The current study uses Bengtson’s intergenerational solidarity theory (Bengtson, 1996; Bengtson, 2001) as a guiding framework to examine later-life intergenerational relationships of adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. One of the key contributions of Bengtson and colleagues has been the investigation of patterns of integration or social cohesion (i.e., solidarity) between aging parents and their adult children (Bengtson & Oyama, 2007; Bengtson & Roberts, 1991). Intergenerational solidarity is conceptualized as a multi-dimensional construct that consists of six distinct but related elements. This construct includes emotional affection, similarity in outlook and values, normative obligation, association (contact), structure including geographic proximity, and exchange of social support (Bengtson & Roberts, 1991). These aspects of solidarity have a significant positive impact on the psychological functioning of adult children. Previous studies have consistently shown that greater emotional closeness with aging parents can enhance the psychological well-being of adult children (Fingerman et al., 2012; Merz, Consedine, Schulze, & Schuengel, 2009; Merz et al., 2009). In addition, close and frequent interactions through contact and support exchanges are associated with greater psychological well-being and fewer depressive symptoms (Davey, Janke, & Savla, 2004; Taylor et al., 2015; Umberson, 1992).

Another important tenet of intergenerational solidarity theory emphasizes a life-course approach to explain factors contributing to current intergenerational relationship quality (Bengtson & Allen, 1993; Steinbach. 2012). One principle of the life course perspective posits that human development and aging are lifelong processes (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003). In other words, understanding behaviors and choices of individuals requires taking into account experiences in earlier stages of life. Accordingly, the quality of intergenerational relationship in later life illuminates the experience and characteristics of early parent-child relationships (George & Gold, 1991). Applying these theoretical viewpoints led us to hypothesize associations among childhood maltreatment, current relational quality, and psychological adjustment in adulthood. Namely, adults with a history of childhood maltreatment may continue their relationship with the perpetrating parent, but aspects of solidarity that reflect relationship quality may have been undermined due to the victimization experience. Specifically, a lack of cohesion in several dimensions (i.e., perceived closeness, contact, and exchange of social support) may ultimately compromise the psychological well-being and functioning of these adult children.

Prior Studies Linking Childhood Maltreatment and Parent-Adult Child Relationships

Only a handful of studies have examined the lingering effect of childhood maltreatment on the relationship with a previously abusive parent in late adulthood, particularly in the context of caregiving. Using the 2004–2005 WLS, Kong and Moorman (2015) found that approximately 10–20% of the caregiver sample reported histories of childhood maltreatment and that providing care to a previously abusive or neglectful parent was associated with more frequent depressive symptoms compared to their non-maltreated counterparts. Similarly, for participants in the study of Midlife in the United States (MIDUS), providing care to a previously abusive parent was negatively associated with psychological functioning; low self-esteem mediated this association (Kong, 2018b).

The adverse effect of childhood maltreatment on caregiving outcomes raises the question of how parental childhood maltreatment affects relationship quality between adults who were abused/neglected as children and their perpetrating parent. Whitbeck and colleagues (1991; 1994) partially addressed the issue, finding that retrospective reports of childhood parental rejection and hostility were associated with adult children expressing less emotional cohesion with aging parents, and this current relationship quality was associated with providing less frequent assistance to parents. Relatedly, Kong and Moorman (2016) examined the association between maternal childhood abuse and the frequency of providing social support to aging mothers. Findings indicated that adults who experienced maternal childhood abuse tend to provide less emotional support to their aging mothers. Recent work of Kong (2018a) analyzed the 2004–2005 WLS, finding that histories of maternal childhood abuse and childhood neglect were associated with lower levels of emotional closeness with mothers, which was in turn associated with lower psychological well-being.

The Present Study

Based on previous research, we hypothesized that aspects of current relationship quality with parents would mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and psychological functioning. The current study addressed several conceptual and methodological gaps in the literature. First, whereas previous research using the WLS examined cross-sectional associations (e.g., Kong, 2018a), this study utilized longitudinal data, collected at three time points across two decades to fully incorporate intergenerational relationships over the span of later adulthood. Second, we examined the effects of childhood maltreatment on the relationship with the maltreating parent as well as the other parent (i.e., examining the effects of the impact of maternal abuse on the current relationship with fathers and that of paternal abuse on the relationship with mothers). Third, we examined the effects of different types of maltreatment (verbal abuse, physical abuse, neglect) on parental relationship quality and adults’ psychological functioning. Lastly, we included both positive and negative psychological functioning outcomes (i.e., psychological well-being and distress). The specific hypotheses were the following: 1) a history of childhood maltreatment undermines the quality of the current relationship with an abusive parent in terms of perceived closeness, frequency of contact, and exchanges of social support with the parent; and 2) current parental relationship quality (closeness, contact, support) mediates the association between childhood maltreatment and psychological functioning in later adulthood.

Methods

Data Set and Study Sample

The WLS is a longitudinal study of 10,317 individuals, representing a randomly selected one-third of all seniors who graduated from high schools in Wisconsin in 1957. The surveys conducted in 1993–1994 (Wave 1), 2004–2005 (Wave 2), and 2010–2011 (Wave 3) offer extensive psycho-social, life-course data of the graduates through their mid- and late adulthood. The retention rates have been high among the surviving graduates. In Wave 1, 87.2% of surviving graduates (n = 8,493) completed the telephone survey and 80.9% of the telephone sample (n = 6,875) completed the mail survey. Across Waves 1 through 3 (i.e., approximately 17 years), the overall response rate for surviving graduates was 73.8%.

The current study used data from Waves 1 through 3 to examine long-term associations between childhood maltreatment (measured at Wave 2), later-life relationships with parents (measured at three-time points), and psychological functioning in late adulthood (measured at three-time points). The final study sample included individuals who reported that their mothers or fathers were alive at the time of data collection at least one time-point in the three waves. In order to best assess the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment by a parent, our analyses focused on two groups – one group consisted of respondents whose mothers were alive and thus reported relationship quality with mothers at least one wave (i.e., the Relationship with Mothers group) and the other group consisted of respondents who fathers were alive and reported relationship quality with fathers at least one wave (i.e., the Relationship with Fathers group). In the Relationship with Mothers group, 4,696 respondents reported their living mothers at Wave 1, 1,570 at Wave 2, and 431 at Wave 3 (See Table 1). The number of respondents who provided at least one data point was 4,736. In the Relationship with Fathers group, 2,134 respondents reported their living fathers at Wave 1, 375 at Wave 2, and 46 at Wave 3. The number of respondents who provided at least one data point was 2,152. Participants in the two groups were not mutually exclusive. There were 1,479 respondents who reported that both of their parents were alive at Wave 1. At Wave 2, 162 respondents reported both parents alive. At Wave 3, 13 respondents reported both parents alive. Because separate analyses were conducted, respondents with both living parents were included in the Relationships with Mothers and Relationships with Fathers groups.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics of Key Variables

| Relationship with Mothers | Relationship with Fathers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Mean(SD) | %/Min./Max. | N/Mean(SD) | %/Min./Max. | |

| Sample Size | ||||

| Wave 1 (1993–1994) | 4,696 | - | 2,134 | - |

| Wave 2 (2004–2005) | 1,570 | - | 375 | - |

| Wave 3 (2010–2011) | 431 | - | 46 | - |

| Childhood Problemsa | ||||

| Verbal abuse by mother | 186 | 5.34 | 84 | 5.35 |

| Physical abuse by mother | 287 | 8.24 | 140 | 8.97 |

| Verbal abuse by father | 339 | 9.55 | 153 | 9.55 |

| Physical abuse by father | 430 | 12.15 | 211 | 13.21 |

| Neglected | 415 | 11.61 | 169 | 10.54 |

| Relationship with Parentsb | ||||

| Perceived closeness | 3.49 (0.66) | 1/4 | 3.38 (0.74) | 1/4 |

| Frequency of contact | 112.38 (119.83) | 0/365 | 88.74 (103.45) | 0/365 |

| Support exchangec | 1.20 (1.15) | 0/3 | 1.18 (1.16) | 0/3 |

| Psychological Functioningb | ||||

| Psychological well-being | 4.91 (0.66) | 1.7/6 | 4.90 (0.67) | 2.1/6 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.79 (0.42) | 02.65 | 0.81 (0.42) | 0/2.65 |

| Sociodemographic Covariates | ||||

| Gendera | ||||

| Male | 2,183 | 46.49 | 1,009 | 47.28 |

| Female | 2,513 | 53.51 | 1,125 | 52.72 |

| Agea | 54.13 (0.49) | 53/56 | 54.11 (0.48) | 53/56 |

| Educational attainmenta | 13.66 (2.29) | 12/21 | 13.79 (2.31) | 12/20 |

| Marital statusb | ||||

| Married | - | 81.24 | - | 82.66 |

| Non-married | - | 18.76 | - | 17.34 |

| Self-rated healthb | ||||

| Excellent/verygood/good | - | 87.93 | - | 88.56 |

| Fair/poor | - | 12.07 | - | 11.44 |

| Birth yeara | ||||

| 1937 | 83 | 1.77 | 32 | 1.50 |

| 1938 | 666 | 14.19 | 287 | 13.45 |

| 1939 | 3,719 | 79.21 | 1,709 | 80.08 |

| 1940 | 227 | 4.83 | 106 | 4.97 |

| Childhood Covariatesa | ||||

| Family-related adversity | 0.28 (0.55) | 0/3 | 0.21 (0.49) | 0/3 |

| Father’s education | 9.94 (3.39) | 0/26 | 10.26 (3.33) | 0/26 |

Notes. The Relationship with Mothers (or Fathers) group consisted of respondents whose mothers (or fathers) were alive across the three waves and reported relationship quality with mothers (or fathers) at each wave. The percentage of variables were calculated based on valid response cases excluding missingness.

denotes values at Wave 1.

denotes grand-means of participants across three-time points.

Support exchange was assessed in regard to both parents.

No consistent pattern of attrition was observed. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine sociodemographic characteristics predicting attrition at Wave 2 and Wave 3. The binary dependent variable was attrition status (0 = retained, 1 = attrited). Socio-demographic covariates (i.e., gender, marital status, self-reported health, years of education, father’s education, birth year, and the variables of childhood experience were entered as predictors (i.e., childhood abuse, neglect, family-related adversity). The results showed that in the Relationship with Mothers group, younger respondents were less likely to attrit at Wave 2 and adults with a history of maternal physical abuse were less likely to attrit at Wave 3. In the Relationship with Fathers group, younger respondents and those who reported better health at baseline were more likely to attrit at Wave 2. Also, respondents who reported more years of fathers’ education were less likely to attrit at Wave 3.

Measures

Independent variables

Childhood maltreatment was assessed by self-reported retrospective measures of abuse and neglect, which is a common approach in research linking childhood maltreatment with later-life health and well-being (e.g., Springer, Sheridan, Kuo & Carnes, 2007).

Childhood abuse.

At Wave 2 respondents reported their experience of parental abuse in childhood. Drawn from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980), parental verbal abuse was measured by the following item: “Up until you were 18, to what extent did your (a) mother, (b) father insult or swear at you?” Physical abuse was measured by an item: “Up until you were 18, to what extent did your (c) mother, (d) father treat you in a way that you would now consider physical abuse?” Respondents rated the items using a four-point Likert scale: “Not at all (1),” “a little (2),” “some (3),” and “a lot (4).” The verbal abuse items asked about parents’ specific behaviors while the physical abuse items asked about respondents’ interpretation of parents’ behaviors; thus, we dichotomized the measures in a different way to delineate abuse experiences. Consistent with prior research (Irving & Ferraro, 2006), respondents who reported “some” or “a lot” for items a and b were coded as being verbally abused as children; “a little” and “not at all” responses were coded as not being verbally abused. To assess physical abuse (items c and d), those who reported “a little,” “some,” or “a lot” as opposed to “not at all” were coded as being physically abused as children (Goodwin, Hoven, Murison, & Hotopf, 2003).

Childhood neglect.

Drawn from the well-validated Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., 1994), child neglect was assessed by an item: “Up until you were 18, how often did you know that there was someone to take care of you and protect you?” Respondents rated the items using a five-point Likert scale: “Never (1),” “rarely (2),” “sometimes (3),” “often (4),” and “very often (5).” Those who reported “never,” “rarely”, and “sometimes” were coded as being neglected as children; those who responded “often,” and “very often” were coded as not being neglected.

Mediators

Relationships with parents.

We included three mediators that assessed perceived closeness with a parent, frequency of contact with a parent, and exchanges of support with both parents (Bengtson, 1996), which were measured repeatedly over the three waves. First, perceived closeness was measured by an item: “How close are you and your a) mother, and b) father?” Respondents rated these items using a four-point Likert scale: “Not at all close (1),” “not very close (2),” “somewhat close (3),” and “very close (4).” Second, the frequency of contact was measured by an item: “How frequently do you have contact with your a) mother, and b) father per year?” Responses greater than 365 were collapsed into one category to remove outliers (Carr, 1997). We note that at Wave 1 and 2, a randomly selected 50% of respondents with living parents responded to the questions regarding perceived closeness and contact frequency1. Lastly, support exchanges with parents were assessed by four indicators: provided instrumental support, received instrumental support, provided emotional support, and received emotional support. Provided instrumental support was measured by aggregating the two following items: “During the past month, did you give help to your parents with (a) transportation, errands or shopping?; (b) housework, yard work, repairs or other work around the house?” Received instrumental support was measured by aggregating the two following items: “During the past month, did you receive help from your parents with (a) transportation, errands or shopping?; (b) housework, yard work, repairs or other work around the house?” Provided emotional support was measured by an item: “During the past month, did you give advice, encouragement, moral or emotional support to your parents?” Received emotional support was measured by an item: “During the past month, did you receive advice, encouragement, moral or emotional support from your parents?” Each item was coded as a binary variable (1 = yes; 0 = no), and the items were summed; the actual range of exchanges of support with parents was 0 to 6. Values greater than 3 were collapsed into one category to deal with skewness.

Dependent variables

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), which was administered at each of the three waves. Each item used an eight-point scale (0 ~ 7) to indicate the number of days in the past week that respondents experienced specific symptoms, such as not being able to shake off the blues even with help from others and having trouble keeping their mind on what they were doing. The total score was calculated by averaging the 20 items (Cronbach’s alpha at WLS I: 0.88). The square root was taken to deal with skewness (i.e., skewness values were greater than 2).

Psychological well-being.

A total of 20 items were administered over the three waves to assess psychological well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). The items asked about respondents’ feelings of autonomy (e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions even if they are contrary to the general consensus.”; 3 items), environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live.”; 3 items), personal growth (e.g., “I have the sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time.”; 3 items), positive relations with others (e.g., “people would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others.”; 4 items), purpose in life (e.g., “I am an active person in carrying out the plans I set for myself.”; 4 items), and self-acceptance (e.g., “In general, I feel confident and positive about myself.”; 3 items). Response choices for each item were based on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6), and the 20 items were averaged to create a total score (Wilson et al., 2013; Cronbach’s alpha at WLS I: 0.89).

Control variables

Socio-demographic covariates.

We included current socio-demographic characteristics as controls, including gender, marital status (married vs. non-married as a reference category), education (in years), birth year, and self-reported health status (good or excellent vs. very poor, poor, or fair as a reference category). Marital status and self-reported health status variables were treated as time-varying; gender and education variables were treated as time invariant.

Other childhood experiences.

To control for adverse experiences that often co-occur with childhood maltreatment, family-related adversity variable was measured with three questions that asked about having witnessed domestic violence (e.g., “up until you were 18, how often did you see a parent or one of your brothers or sisters get beaten at home?”), having lived with a problem drinker or alcoholic (“when you were growing up, that is during your first 18 years, did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic?”), and not having lived with both parents (“did you live with both parents most of the time up until 1957?”). A total score was created by summing the number of yes responses (range: 0 ~ 3). In addition to family-related adversity, the father’s level of education was included to control for childhood socioeconomic status.

Analytic Strategy

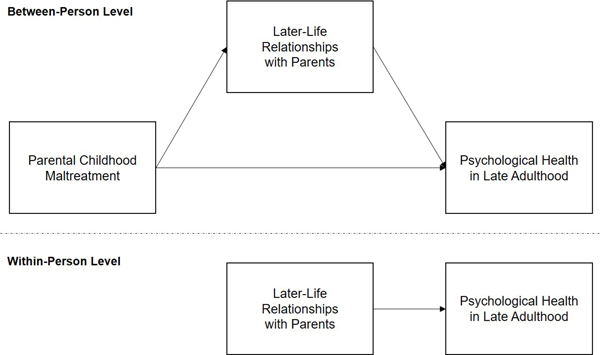

Using Mplus Version 6, we conducted multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM). Utilizing longitudinal data not only incorporates individuals’ intergenerational relationships in middle and late adulthood across two decades but also increases statistical power and reliability of measures. When applied to longitudinal data, MSEM partitions the variance of a time-varying variable into latent within-person components (fluctuations over time relative to the person’s own mean) and latent between-person components (person-level means across time points), which then estimate separate between- and within-person covariance matrices (Preacher et al., 2010). Our mediational model involved time-invariant, Level-2 predictors (i.e., childhood abuse and neglect); time-varying, Level-1 mediators (i.e., perceived closeness, the frequency of contact, and social support exchange); and time-varying, Level-1 outcomes (i.e., psychological well-being and depressive symptoms). MSEM is advantageous in terms of estimating indirect effects in a mediational model that includes Level-2 predictors without introducing conflation or bias (Preacher et al., 2010). As shown in Figure 1, our focal interest was in examining whether and how between-person variability in later-life relationships with parents would mediate a history of childhood maltreatment and psychological outcomes.

Figure 1.

Analytic Model of Multi-Level Mediation

Robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) was applied in the analysis, and missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach. In terms of evaluating the goodness of fit of the hypothesized model, we assessed separate model fit at the within- and between-person levels by producing estimates of saturated covariance matrices at each level (Ryu, 2014). The model fit was evaluated based on the following criteria of the goodness-of-fit indices: (a) comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95, (b) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .05, and (c) standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08.

Results

Table 1 shows summary statistics for key variables for each subgroup (i.e., the Relationship with Mothers group, and the Relationship with Fathers group). In both groups, less than 15% of respondents reported maternal childhood abuse and approximately a quarter of respondents reported paternal childhood abuse. Also, approximately 10% of respondents reported having been neglected during childhood. At Wave 1, half of the respondents were female and the average age was 54 years. Respondents reported less than one experience of family-related adversity during childhood, on average. Means, standard deviation and bivariate correlations of the variables are available in Supplementary Tables 1–2.

MSEM Estimates of Direct and Indirect Effects

Table 2 and 3 provide the results of associations from the MSEM analyses based on the primary aims of this study. Overall, the models fit the data well (Relationship with Mothers: χ2 =573.29, p <.001; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.04; Relationship with Fathers: χ2 = 280.71, p <.001; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.94; SRMR = 0.04).

Table 2.

MSEM Estimates of Direct Effects

| Relationship with Mothers Group |

Relationship with Fathers Group |

|

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Est (SE) | Unstandardized Est (SE) | |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Perceived closeness | −0.41 (0.09)*** | 0.06 (0.15) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Frequency of contact | −19.23 (10.56) | −5.38 (14.94) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Support exchange | −0.15 (0.09) | −0.04 (0.15) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Perceived closeness | 0.01 (0.06) | −0.37 (0.12)** |

| Verbal abuse by father → Frequency of contact | 3.61 (7.76) | −12.48 (10.57) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Support exchange | −0.06 (0.08) | −0.05 (0.13) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Perceived closeness | −0.27 (0.07)*** | −0.02 (0.13) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Frequency of contact | −9.03 (9.34) | −19.67 (10.76) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Support exchange | −0.01 (0.09) | −0.01 (0.13) |

| Physical abuse by father → Perceived closeness | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.09) |

| Physical abuse by father → Frequency of contact | −12.07 (7.13) | −6.30 (9.16) |

| Physical abuse by father → Support exchange | 0.05 (0.07) | −0.01 (0.11) |

| Neglected → Perceived closeness | −0.26 (0.05)*** | −0.22 (0.09)* |

| Neglected → Frequency of contact | −15.21 (6.85)* | −2.11 (10.12) |

| Neglected → Support exchange | −0.22 (0.06)*** | 0.06 (0.11) |

| Perceived closeness → Psychological well-being | 0.13 (0.05)** | 0.18 (0.08)* |

| Perceived closeness → Depressive symptoms | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.04) |

| Frequency of contact → Psychological well-being | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Frequency of contact → Depressive symptoms | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Support exchange → Psychological well-being | 0.15 (0.06)** | 0.10 (0.11) |

| Support exchange → Depressive symptoms | −0.05 (0.03) | 0.11 (0.08) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Psychological well-being | 0.12 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.10) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Depressive symptoms | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Psychological well-being | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.05 (0.08) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Depressive symptoms | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Psychological well-being | 0.11 (0.05)* | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Physical abuse by mother →Depressive symptoms | −0.04 (0.03) | −0.06 (0.05) |

| Physical abuse by father → Psychological well-being | −0.10 (0.05)* | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Physical abuse by father → Depressive symptoms | 0.06 (0.03)* | 0.05 (0.04) |

| Neglected → Psychological well-being | −0.10 (0.04)* | −0.07 (0.07) |

| Neglected → Depressive symptoms | 0.09 (0.03)*** | 0.10 (0.05) |

Note. Significance levels are denoted as p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 3.

Relationship with Mothers: MSEM Estimates of Indirect Effects

| Between-person indirect effects | Unstandardized |

|---|---|

| Est (SE) | |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Perceived closeness with mothers → | −0.06 (0.02)* |

| Psychological well-being (PWB) | |

| Verbal abuse by father → Perceived closeness with mothers → PWB | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Perceived closeness with mothers → PWB | −0.04 (0.02)* |

| Physical abuse by father → Perceived closeness with mothers → PWB | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Neglected → Perceived closeness with mothers → PWB | −0.03 (0.01)** |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Contact frequency with mothers → PWB | 0.02 (0.01) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Contact frequency with mothers → PWB | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Contact frequency with mothers → PWB | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by father → Contact frequency with mothers → PWB | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Neglected → Contact frequency with mothers → PWB | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Support exchange → PWB | −0.02 (0.02) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Support exchange → PWB | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Support exchange → PWB | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by father → Support exchange → PWB | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Neglected → Support exchange → PWB | −0.03 (0.02)* |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Perceived closeness with mothers → | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Depressive symptoms (DEP) | |

| Verbal abuse by father → Perceived closeness with mothers → DEP | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Perceived closeness with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Physical abuse by father → Perceived closeness with mothers → DEP | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Neglected → Perceived closeness with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Contact frequency with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.01) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Contact frequency with mothers → DEP | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Contact frequency with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Physical abuse by father → Contact frequency with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Neglected → Contact frequency with mothers → DEP | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Verbal abuse by mother → Support exchange → DEP | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Verbal abuse by father → Support exchange → DEP | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Physical abuse by mother → Support exchange → DEP | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Physical abuse by father → Support exchange → DEP | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Neglected → Support exchange → DEP | 0.01 (0.01) |

Note. N = 4,696 (Wave 1). Significance levels are denoted as p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

First, in the Relationship with Mothers group, reports of having been verbally or physically abused by the mother during childhood were associated with lower levels of perceived closeness with mothers (b = −0.41; b = −0.27, ps = .000). Reports of having been abused by the father were not significantly associated with the relationship with mothers in later life. Reports of having been neglected were associated with lower perceived closeness (b = −0.26, p = .000), less frequent contact with mothers (b = −15.21, p = .026), and less exchange of support with parents (b = −0.22, p = .000). In turn, perceived closeness with mothers and levels of support exchange were positively associated with the level of psychological well-being (b = 0.13, p = .003; b = 0.15, p = .008, respectively). We found significant mediational associations such that reports of having been verbally abused, physically abused, or neglected were associated with lower levels of psychological well-being partly through lower levels of perceived closeness with mothers (b =−0.06, p = .010; b = −0.04, p = .020; b = −0.03, p = .008, respectively; See Table 3). Also, reports of having been neglected were associated with lower levels of psychological well-being partly through lower levels of support exchange with parents (b = −0.03, p = .030). Unexpectedly, we found the positive direct effects of maternal physical abuse on psychological well-being after controlling for the mediator (b = 0.11, p = .04). We did not find significant mediational associations for the paths involving reports of childhood maltreatment, relationships with mothers, and depressive symptoms.

In the Relationship with Fathers group, reports of having been verbally abused by the father or neglected were associated with lower levels of perceived closeness with fathers (b = −0.37, p = .001; b = −0.22, p = .016, respectively). In turn, perceived closeness with fathers was positively associated with the level of psychological well-being of adult children (b = 0.18, p = .017), although we did not find evidence of mediation.

For a sensitivity check, we re-estimated the MSEM model using the original Likert-scale measures of childhood abuse and neglect. A few differences were found in the mediational associations. In the Relationship with Mothers group, reports of having been physically abused by the mother were not significantly associated with perceived closeness with mothers at the .05 significance level (b = −0.08, p = .088) as they were with the dichotomized abuse measure. The mediation effect for mothers’ greater physical abuse, perceived closeness, and psychological well-being was not statistically significant (b = −0.01, p = .161). In the Relationship with Fathers group, the size and significance of the coefficients were substantially similar to those found with the dichotomized measures.

Supplementary Analyses

Temporal ordering of the mediational associations.

To tease apart the temporal order among key variables, we estimated the cross-lagged mediational model in which the dependent variable was psychological well-being, with childhood abuse and neglect as the key predictors and intergenerational relationship as the mediator (e.g., Michl, McLaughlin, Shepherd, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2013). For example, the childhood abuse and neglect measures were expected to have direct effects on psychological well-being at Wave 3, controlling for psychological well-being at Wave 1. Childhood abuse and neglect measures were also expected to have a negative association with perceived closeness with mothers at Wave 2, controlling for Wave 1 perceived closeness with mothers. Perceived closeness with mothers at Wave 2 was expected to show a positive association with Wave 3 psychological well-being, controlling for Wave 1 emotional closeness with mothers and psychological well-being. This model allowed us to investigate whether childhood abuse and neglect predicted changes in perceived closeness with mothers and whether those changes predicted subsequent changes in psychological well-being.

The results showed that the mediation linking mother’s verbal abuse, changes in perceived closeness with mothers between Wave 1 and Wave 2, and changes in psychological well-being between Wave 2 and Wave 3 was only marginally significant in the expected direction (p = .095). The mediational links involving the mother’s physical abuse and neglect as key predictors were not statistically significant. Considering the rigorous analytic approach of cross-lagged panel models, the high attrition of the study sample may have led to less statistical power than was present for the longitudinal models. We also conducted the reverse causality analysis with psychological health as the mediator and intergenerational relationship as the dependent variable, which did not yield a significant mediational association.

Later-life relationships with a non-abusive parent.

We did not find any significant associations between reports of paternal childhood abuse and later relationships with mothers (after controlling for the reports of maternal abuse); likewise, no significant associations were observed between reports of maternal childhood abuse and later relationships with fathers (after controlling for the reports of paternal abuse). To estimate more precise associations with a non-abusive parent, we re-estimated our model after excluding respondents who reported having been abused by both parents. First, in the Relationship with Mothers group, we excluded respondents who reported having been verbally or physically by mothers and then estimated the mediational associations involving reports of paternal childhood abuse, relationships with mothers, and psychological functioning outcomes. There were no significant associations between reports of paternal childhood abuse and the relationships with mothers, except that father’s physical abuse was associated with less frequent contact with mothers (b = −19.55, p = .015). Second, in the Relationship with Fathers group, we excluded respondents who reported having been verbally or physically by fathers and estimated the associations involving reports of maternal childhood abuse, relationships with fathers, and psychological functioning outcomes. We did not find any significant associations between reports of maternal childhood abuse and the relationships with fathers.

Multiple group analysis between men and women.

Gender of an adult child is a key predictor of parent-adult child relationship quality (Birditt, Miller, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2009). Prior studies suggest that women have more frequent contact with their parents, greater feelings of closeness, and are more likely to exchange support with them (Swartz, 2009). Thus, we conducted multi-group SEM analyses to compare parameter estimates between male and female adult children using the baseline data. We first estimated a model with all parameters allowed to be unequal between men and women. We then constrained each parameter to be equal across men and women and conducted chi-square difference tests to identify the source of non-invariance between men and women (Bollen, 1989). The results indicated that the significant mediational associations were consistent between men and women, but we noted a few differences. In the Relationship with Mothers group, reports of mother’s physical abuse were associated with less contact with the mothers for women, but not for men (men: b = 0.17, p =.377; women: b = −0.37, p = .031). In the Relationship with Fathers group, we did not find meaningful differences between men and women. For example, the effects of the father’s physical abuse were positively associated with support exchange for men but negatively associated with support exchange for women, both of which were not statistically significant.

Discussion

The aims of this study were twofold. We first sought to link the reports of childhood maltreatment with aspects of adults’ relationship quality with aging parents, through their mid-50s through 70s. Second, we sought to investigate whether and how contemporary relationships with parents mediated the association between reports of childhood maltreatment and psychological outcomes in late adulthood. Our findings suggested that adults who reported past victimization may continue to experience challenges in their relationship with the perpetrating parent.

Effect of Childhood Maltreatment on Relationships with Aging Parents

Our first hypothesis was supported in that adults with a history of childhood abuse showed lower levels of perceived closeness with abusive mothers and fathers compared to their non-abused counterparts. Also, adults with a history of childhood neglect reported their relationships with aging mothers as less emotionally close, less frequent in contact, and characterized by fewer exchanges of support. In addition, they reported their relationships with aging fathers as less emotionally close than did those who were not neglected. These results are partially consistent with our previous work (Kong, 2018a), which showed that reports of maternal childhood abuse and neglect were concurrently associated with a lower level of affectual solidarity with aging mothers, as well as the findings of Savla and colleagues (2013) that a history of childhood abuse was associated with a lower level of emotional closeness with family members (excluding spouses/partners) in mid- and late-adulthood. Using longitudinal data over a span of two decades, the current study further supports life-long linkages in intergenerational relationships for adults who were maltreated as children: dysfunctional parent-child relationships persist until late adulthood in a way that undermines the levels of perceived closeness and interactions through contact and social support exchanges with the perpetrating parent.

Interestingly, we did not find significant associations between childhood maltreatment and later relationships with a non-abusive parent (i.e., examining the association between reports of maternal abuse and relationships with fathers, and the association between reports of paternal abuse on relationships with mothers), except that father’s physical abuse was associated with less frequent contact with mothers. Our speculation is that there might be individual differences within these parent-adult child dyads. For example, some abused adults might be more attached to their non-abusive parent, particularly if that individual was also victimized by the partner and they developed protective strategies together (Hemphreys, Mullender, Thiara, & Skamballis, 2006; Radford & Hester, 2001). Others may be disconnected or even enraged toward a non-abusive parent who failed to properly protect them from the abusive parent (Mullender et al., 2002). Future research might explore this complexity in the relationships between previously victimized adults and their non-abusive parent, perhaps through qualitative investigations, to identify distinctive dynamics within this group of dyads and their differential impacts on relational and psychological outcomes.

Perceived Closeness with Aging Mothers as a Mediator

Our second hypothesis was partially supported in that perceived closeness with aging mothers significantly mediated the associations between reports of maternal childhood abuse and neglect and the psychological well-being of adult children. According to the intergenerational solidarity literature, the measure of perceived closeness (i.e., “are you close to your mother/father?”) represents affectual solidarity—the emotional complexity involving a range of intimacy and distance within intergenerational relations (Bengtson & Roberts, 1991; Hammarstrom, 2005; Monserud, 2008). Affectual solidarity is one of the most important aspects of intergenerational solidarity (Roberts, Richards, & Bengtson, 1991); studies have shown that affective sentiments in a parent-adult child relationship can enhance the psychological well-being of adult children, reduce conflicts within the relationships, and result in positive outcomes of caregiving (Merz et al., 2009; Crispi, Schiaffino, & Berman, 1997; Fauth et al., 2012). This result also supports other studies showing that the evaluation of the emotional quality of relationships has more of an impact on health and well-being than other objective characteristics of relationships, such as social network size or social support exchange (Antonucci, Fiori, Birditt, & Jackey., 2010; Antonucci, Fuhrer, & Dartigues, 1997). Nonetheless, we would like to note that the indirect associations were not supported in the cross-lagged mediational model, which requires cautious interpretation of the results. In addition, although the coefficients of the indirect associations were statistically significant, their size is not substantively large.

It is also worth noting the positive direct effects of maternal physical abuse on psychological well-being for adult children with living mothers. Maternal abuse during childhood may contribute to strengthening some aspects of positive psychological functioning, such as personal growth (Kong, 2018) especially after controlling for the current relationship quality with the abusive mother. Similar results were highlighted by prior studies on post-traumatic growth which suggest that positive change can result from one’s struggle with a life challenge or even a traumatic event (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2001).

We also note that perceived closeness with mothers, but not fathers, was the salient mediating factor linking reports of childhood maltreatment and later psychological well-being. This result may be attributed to that mothers would have been their primary care-takers for the majority of the study respondents. Attachment theorists argue that a secure attachment with a primary caretaker is the single most important source of positive child development (Bowlby, 1988; Davila & Levy, 2006). Our findings may indicate that beyond childhood and adolescence (Moylan et al., 2010; Perry, 2001; Trickett, Negriff, & Peckins, 2011), relationship quality with mothers may be associated with adult children’s psychological well-being, particularly for those with a history of childhood maltreatment. Although the gender of the parent mattered, the gender of offspring did not make a difference in terms of the overall mediational patterns according to the results of the supplementary analysis. This is somewhat inconsistent with prior researching showing that women tend to invest more in intergenerational relationships through frequent interactions and strong emotional bonds (Swartz, 2009). We cautiously conclude that the ways in which the negative health effects of childhood maltreatment are manifested through later parent-adult child relationships may not differ between men and women.

Lastly, the mediation involving having been neglected, support exchange with parents, and psychological well-being was statistically significant. Having less exchange of support with aging parents, which may be consistent with their childhood experience, may undermine psychological health of adults with a history of childhood neglect. This is somewhat contrary to the result that the level of support exchanged with parents was not predicted by a history of childhood abuse, nor did it mediate the association between reports of childhood maltreatment and psychological outcomes. These results suggest that, despite earlier abuse, adults who were abused as children may interact with parents through social support exchanges as much as non-abused adults do (Kong & Moorman, 2006; Kong, 2018b). Furthermore, psychological effects associated with the interaction might have been suppressed, potentially by filial or cultural norms of supporting aging parents (Rossi & Rossi, 1991). Alternatively, the non-significant associations might be explained by the measure of support exchange which did not ask about specific mothers or fathers but referred to both parents.

Limitations

This study has limitations to consider. First, while retrospective self-reports of childhood abuse and neglect are commonly used in research linking childhood maltreatment to later-life health and well-being, such reports may involve recall errors (Fallon et al., 2010). Particularly, the physical abuse items were more subject to measurement error by allowing respondents to self-define physical abuse experiences rather than report specific behaviors of parents. It would be ideal for future research to incorporate a prospective research design. Second, the use of secondary data entailed limitations in available measures. The childhood neglect and support exchange items were not specific to mothers or fathers but indicative of both parents, which prevented us from examining associations specific to the perpetrating parent. In addition, a measure of normative obligation was not available, and this construct constitutes an essential aspect of some intergenerational relationships. Prior studies have shown that strong filial norms serve as the source of strong affection and frequent interactions in intergenerational relationships (Parrott & Bengtson, 1999; Schwarz, Trommsdorff, Albert, & Mayer, 2005). The experience of parental maltreatment during childhood may weaken this normative tie to parents and detract from other aspects of a relationship such as a contact frequency. On the other hand, filial norms may facilitate abused adults’ relationship maintenance with their aging parents. Future research may explore the effect of parental childhood maltreatment on normative obligations in later adulthood and how this belief system may impact other aspects of intergenerational relationships, as well as the health and well-being of adult children. Third, the current analytic framework could not disentangle temporal order between the quality of relationships and psychological adjustment. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that adults’ psychological adjustment might have affected the quality of relationships with their aging parents. To address this concern, future research may explore how trajectories of relationship quality with parents are associated with prospective health outcomes for adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Next, the unique characteristics of the WLS participants may limit the generalizability of the study findings. Specifically, the respondents were limited to those living in the Wisconsin area. Also, the majority of study participants were non-Hispanic white, economically wealthy, and having at least a high school education. These sample characteristics may suggest that our results are conservative as we found significant mediational associations in a study sample with protective socio-economic characteristics. Lastly, as noted, extensive attrition occurred in our sample. The attrition analysis indicated a few significant differences between those who left the study and those who did not, but no consistent patterns were identified across the two groups.

Implications

Despite these limitations, this study makes several significant contributions. First, adults with a history of childhood maltreatment continue their relationships with aging parents, which may negatively impact the psychological well-being of these adult children. This new knowledge can serve to better understand abused adults’ experience and outcomes of caregiving for their perpetrating parent (Kong & Moorman, 2016; Kong, 2018b). The key to ameliorating negative caregiving outcomes may lie in properly addressing the relationship with the perpetrating parent (Merz, et al., 2009). Future studies should empirically test this speculation by examining a history of child maltreatment, current relationship quality with aging parents, and caregiving outcomes all together in the same model. Other inquiries may include examining the caregiving status as a factor, or a moderator, to affect later-life relationship quality with abusive/neglectful parents.

This study’s findings also have important implications for practice. In regard to intervening with adults with a history of childhood maltreatment, practitioners may need to evaluate contemporary relationship quality with the abusive parent in order to identify strategies to relieve the stress associated with this relationship. Practitioners can also help these abused adults become more aware that their relationship with an abusive mother may be a source of negative psychological outcomes. These interventions can help guide abused adults to address emotionally unresolved issues with the parent. Further research will be needed to suggest more concrete intervention strategies and to promote resilience in these abused adults. For example, researchers may identify the individual and contextual characteristics of adults with a history of childhood maltreatment who report positive psychological outcomes in their relationship with an abusive parent. Furthermore, investigating relationships with aging parents in connection with other family members, including the family of origin and family of procreation, warrants future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging Grants T32 AG049676 (D. Almeida) and K02 AG039412 (L. Martire) to The Pennsylvania State University.

Footnotes

There has been no prior dissemination of the ideas and data appearing in the manuscript.

At Wave 1, a randomly selected 50% of respondents reported their current relationships with parents (i.e., perceived closeness and contact frequency) and these respondents were followed up at Wave 2 to respond to the same set of questions. At Wave 3, all participating respondents responded to these questions. For a sensitivity check, we limited the study sample to respondents who were randomly selected at Wave 1 and those with a living parent at the time of data collection. We then followed up on those with living parents at Wave 2 and 3. This changed the sample size (Relationship with Mothers group – Wave 1: 2,432, Wave 2: 772, Wave 3: 213; Relationship with Fathers group – Wave 1: 1,067, Wave 2: 190, Wave 3: 29), but yielded substantially similar results to those obtained with the entire sample (results available upon request).

Contributor Information

Jooyoung Kong, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Lynn M. Martire, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, & Birditt KS (2013). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54, 82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Fiori KL, Birditt KS, & Jackey LMH (2010). Convoys of social relations: Integrating life-span and life-course perspectives In Lerner RM, Lamb ME, Freund AM (Eds.), The handbook of life-span development (pp. 434–473). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Fuhrer R, & Dartigues J. (1997). Social relations and depressive symptomatology in a sample of community-dwelling French older adults. Psychology and Aging, 12(1), 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL (1996). Continuities and discontinuities in intergenerational relationships over time In Bengtson VL (Eds.), Adulthood and aging: Research on continuities and discontinuities (pp. 271–307). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, & Allen KR (1993). The life course perspective applied to families over time In Boss P, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, & Steinmetz SK (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 469–504). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Lowenstein A, Putney NM, & Gans D. (2003). Global aging and the challenge to families In Bengtson VL & Lowenstein A. (Eds.), Global aging and challenges to families (pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, & Oyama PS (2007). Intergenerational solidarity: Strengthening economic and social ties In Bengtson VL & Achenbaum WA (Eds.), The changing contract across generations (pp. 3–23). New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, & Roberts REL (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 856–870. doi: 10.2307/352993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, … Ruggiero J. (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Miller LM, Fingerman KL, & Lefkowitz ES (2009). Tensions in the parent and adult child relationship: Links to solidarity and ambivalence. Psychology and Aging, 24, 287–295. doi: 10.1037/a0015196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989) Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bozhenko E. (2011). Adult child-parent relationships: On the problem of classification. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1625–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. (1997). The fulfillment of career dreams at midlife: Does it matter for women’s mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(4), 331–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispi E, Schiaffino K, & Bermann W. (1997). The contribution of attachment to burden in adult children of institutionalized parents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 37, 52–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, Janke M, & Savla J. (2004). Antecedents of intergenerational support: Families in context and families as context In Silverstein M. & Schaie KW (Eds.), Intergenerational relations across time and place: Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, & Levy K. (2006). Introduction to the special section on attachment theory and psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 989–993. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, & Crosnoe R. (2003). The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory In Mortimer JT& Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course (pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon B, Trocme N, Fluke J, MacLaurin B, Tonmyr L, & Yuan Y. (2010). Methodological challenges in measuring child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth E, Hess K, Piercy K, Norton M, Corcoran C, Rabins P, … & Tschanz J. (2012). Caregivers’ relationship closeness with the person with dementia predicts both positive and negative outcomes for caregivers’ physical health and psychological well-being. Aging and Mental Health, 16, 699–711. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.678482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Sechrist J, & Birditt K. (2012). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology, 59, 64–70. doi: 10.1159/000342211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Iglesias HR, Webster NJ, & Antonucci TC (2015). The complex nature of family support across the life span: Implications for psychological well-being. Developmental Psychology, 51, 277–288. doi: 10.1037/a0038665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, & Gold DT (1991). Life course perspectives on intergenerational and generational connections. Marriage and Family Review, 16, 67–88. doi: 10.1300/J002v16n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Hoven CW, Murison R, & Hotopf M. (2003). Association between childhood physical abuse and gastrointestinal disorders and migraine in adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1065–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstrom G. (2005). The construct of intergenerational solidarity in a lineage perspective: A discussion on underlying theoretical assumption. Journal of Aging Studies, 19, 33–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphreys C, Mullender A, Thiara R, & Skamballis A. (2006). ‘Talking to my mum’: Developing communication between mothers and children in the aftermath of domestic violence. Journal of Social Work, 6, 53–63. doi: 10.1177/1468017306062223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irving SM, Ferraro KF (2006). Reports of abusive experiences during childhood and adult health ratings: Personal control as a pathway? Journal of Aging and Health, 18, 458–485. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J. (2018a). Childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being in later life: the mediating effect of contemporary relationships with the abusive parent. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, e39–e48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J. (2018b). Effect of caring for an abusive parent on mental health: The Mediating role of self-esteem. The Gerontologist, 58, 456–466. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, & Moorman SM (2015). Caring for my abuser: Childhood maltreatment and caregiver depression. The Gerontologist, 55, 656–666. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, & Moorman SM (2016). History of childhood abuse and intergenerational support to mothers in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 926–938. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merz E, Consedine N, Schulze H, & Schuengel C. (2009). Wellbeing of adult children and ageing parents: associations with intergenerational support and relationship quality. Ageing and Society, 29, 783–802. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merz E, Schuengel C, & Schulze H. (2009). Intergenerational relations across 4 years: Well-being is affected by quality, not by support exchange. The Gerontologist, 49, 536–548. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, & Russo MJ (2010). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monserud MA (2008). Intergenerational relationships and affectual solidarity between grandparents and young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 182–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00470.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullender A, Hague G, Imam U, Kelly L, Malos E. and Regan L. (2002). Children’s Perspectives on Domestic Violence. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott T, & Bengtson VL (1999). The effects of earlier intergenerational affection, normative expectations, and family conflict on contemporary exchanges of help and support. Research on Aging, 21, 73–105. doi: 10.1177/0164027599211004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. (2001). Violence and childhood: How persisting fear can alter the developing child’s brain In Schetky D. & Benedek E. (Eds.), Text book of child and adolescent forensic psychiatry (pp. 221–238). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, & Zhang Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford L. and Hester M. (2001). Overcoming mother blaming? Future directions for research on mothering and domestic violence, In Graham-Bermann S. and Edleson J. (Eds.), Domestic violence in the lives of children (pp. 135–156). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, Richards L, & Bengtson VL (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in families: Untangling the ties that bind. Marriage and Family Review, 16, 11–46. doi: 10.1300/J002v16n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, & Rossi PH (1991). Normative obligations and parent-child help exchange across the life course In Pillemer K. and McCartney K. (Eds.), Parent-child relations throughout life (pp. 201–223). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Keyes CLM (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu E. (2014). Model fit evaluation in multilevel structural equation models. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla JT, Roberto KA, Jaramillo-Sierra AL, Gambrel LE, Karimi H, & Butner LM (2013). Childhood abuse affects emotional closeness with family in mid- and later life. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37, 388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz B, Trommsdorff G, Albert I, & Mayer B. (2005). Adult parent-child relationships: Relationship quality, support, and reciprocity. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 396–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00217.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, & Carnes M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 517–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach A. (2012). Intergenerational relations across the life course. Advances in life course research, 17, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2012.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, & Steinmetz S. (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New York, NY: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Gilligan M, & Pillemer K. (2011). Intergenerational relations in later life families In Settersten R. & Angel J. (Eds.), Handbook of sociology of aging (pp. 161–178). New York, NY: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz TT (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 191–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Lincoln KD, & Chatters LM (2015). Extended family and friendship support networks are both protective and risk factors for major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms among African-Americans and Black Caribbeans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203, 132–140. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Negriff S, Ji J, & Peckins M. (2011). Child maltreatment and adolescent development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00711.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 664–674. doi: 10.2307/353252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, & Huck SM (1994). Early family relationships, intergenerational solidarity, and support provided to parents by their adult children. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 49, S85–S94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Simons R, & Conger R. (1991). The effects of early family relationships on contemporary relationships and assistance patterns between adult children and their parents. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 46, S330–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.S330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Yu L, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, & Bennett DA (2013). The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychology and Aging, 28, 304–313. doi: 10.1037/a0031196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.