Abstract

Regulation of ATP production by mitochondria, critical to multicellular life, is poorly understood. Here we investigate the molecular controls of this process in heart and provide a framework for its Ca2+-dependent regulation. We find that the entry of Ca2+ into the matrix through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) in heart has neither an apparent cytosolic Ca2+ threshold nor gating function and guides ATP production by its influence on the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) potential, ΔΨm. This regulation occurs by matrix Ca2+-dependent modulation of pyruvate and glutamate dehydrogenase activity and not through any effect of Ca2+ on ATP Synthase or on Electron Transport Chain Complexes II, III or IV. Examining the ΔΨm dependence of ATP production over the range of −60 mV to −170 mV in detail reveals that cardiac ATP synthase has a voltage dependence that distinguishes it fundamentally from the previous standard, the bacterial ATP synthase. Cardiac ATP synthase operates with a different ΔΨm threshold for ATP production than bacterial ATP synthase and reveals a concave-upwards shape without saturation. Skeletal muscle MCU Ca2+ flux, while also having no apparent cytosolic Ca2+ threshold, is substantially different from the cardiac MCU, yet the ATP synthase voltage dependence in skeletal muscle is identical to that in the heart. These results suggest that while the conduction of cytosolic Ca2+ signals through the MCU appears to be tissue-dependent, as shown by earlier work1, the control of ATP synthase by ΔΨm appears to be broadly consistent among tissues but is clearly different from bacteria.

ATP consumption in heart is the highest of any tissue and, even with the phosphocreatine regenerating system, the ATP reserve is minimal ― lasting less than 1 minute if ATP production were to be stopped instantaneously2,3. It is thus not surprising that mitochondria, the primary source of ATP production, play an important role in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology4. Mitochondria are similarly important in other high-energy-consuming tissues such as brain, kidney, liver and skeletal muscle5,6. Despite the critical importance of mitochondria in producing ATP, there is little time-resolved quantitative data on how mitochondria work7,8. Here we provide quantitative information on how cardiac mitochondria generate ATP, how ATP production is powered by ΔΨm, and how ΔΨm is regulated by Ca2+ concentration in the mitochondrial matrix ([Ca2+]m).

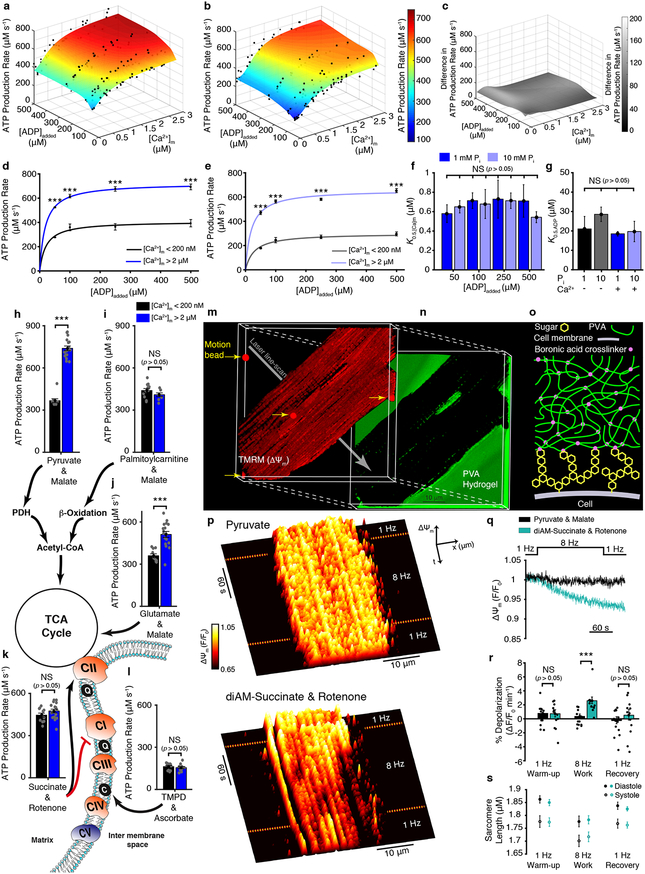

Fig. 1a–b show surface plots of ATP production measured as functions of [Ca2+]m and the added concentrations of ADP ([ADP]). Fluorescence [Ca2+]m and luminescence ATP measurements were performed together from isolated heart mitochondria and quantitatively calibrated in each test condition (Extended Data Figs. 1–3). These data show that elevated [ADP] and [Ca2+]m robustly stimulate ATP production (Fig. 1a–e), with a half-activation concentration of ~20 μM for [ADP] (Fig. 1g) and ~600 nM for [Ca2+]m (Fig.1d–f). ADP and [Ca2+]m work by different mechanisms. Elevated [ADP] increases the ADP flux into the mitochondrial matrix, mediated by the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), thus increasing substrate availability for the ATP synthase to augment ATP production9,10 (also see Supplemental Discussion 2.1). On the other hand, increasing the steady-state availability of inorganic phosphate (Pi) from 1 mM (physiological) to 10 mM (super-physiological) diminished ATP production (Fig. 1b, 1f and 1g). Fig. 1c shows the absolute value of the difference. These results are the first determination of the dependence of ATP production on the three key variables, [Ca2+]m, [ADP] and [Pi], and provide an important context for additional physiologic investigations.

Figure 1. [Ca2+]m sensitive ATP production by mitochondria.

a. The dependence of ATP production (μM/s) on [Ca2+]m and [ADP]added at 1 mM Pi (n= 37, 38, 38, 29 for 500, 250, 100, 50 μM ADP added, respectively). b. Same as (a) but at 10 mM Pi (n= 28, 27, 30, 42 for 500, 250, 100, 50 μM ADP added, respectively). c. The difference in ATP production rates between 1 mM Pi and 10 mM Pi. d. Dependence of ATP production (μM/s) on ADP at 1 mM Pi when [Ca2+]m is < 200 nM (black circles, n= 3, 3, 3, 5 for 50, 100, 250, 500 μM ADP added, respectively) or > 2 μM (blue circles, n= 8, 7, 6, 9 for 50, 100, 250, 500 μM ADP added, respectively). Data are fit to a Michaelis–Menten equation. e. Same as (d) but at 10 mM Pi when [Ca2+]m is <200 nM (grey circles, n= 8, 6, 3, 7 for 50, 100, 250, 500 μM ADP added, respectively) or 2 μM (light blue circles, n= 5, 7, 5, 5 for 50, 100, 250, 500 μM ADP added, respectively). Data are fit to Michaelis–Menten equation. f. [Ca2+]m at which ATP production rate is half maximal (K0.5,[Ca]m) for [ADP]added at both 1 and 10 mM Pi. Each bar shows the K0.5,[Ca]m constant of each of the eight fit lines shown as surface plots in a-b (K0.5,[Ca]m ± s.e. of fit in μM, fitted sample size is given in a-b, individual data points shown in a-b). g. [ADP]added at which ATP production is half maximal (K0.5,ADP) for [Ca2+]m <100 nM (−) and >2 μM (+) at both 1 and 10 mM Pi. Each bar shows the K0.5,ADP constant of each of the four fit lines shown in d-e (K0.5,[Ca]m ± s.e. of fit in μM, fitted sample size is given in d-e, individual data points shown in a-b). h-l. ATP production rate at low [Ca2+]m (<200 nm, black bar) and high [Ca2+]m (>2 μM, blue bar) using the indicated combination of carbon substrates and metabolic inhibitors (n= 10–20 per group). Abbreviations used in the diagram: PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; CI, Complex 1; CII, Complex 2; CIII, Complex 3; CIV, Complex 4; CV, Complex 5 (i.e. ATP synthase); Q, ubiquinone; C, cytochrome c. m. 3D reconstruction of confocal Z-stack images of a cardiomyocyte loaded with the fluorescent indicator TMRM (tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate, 50 nM). n. The fluorescence of fluorescein-containing poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) hydrogel that embeds the cell shown in (m). o. Diagram showing boronic acid crosslinker linking cell-surface sugars to the PVA hydrogel. p. Fluorescence surface plot demonstrating spatiotemporal changes of ΔΨm. Measurements are done on cardiomyocyte paced by field-stimulation to contract at 1 or 8 Hz in a bath (extracellular) solution that contains top; pyruvate (1 mM) and malate (0.5 mM), or bottom; diAM-succinate (succinic acid diacetoxymethyl ester, 10 μM) and rotenone (5 μM). q. Average ΔΨm fluorescence time course using pyruvate + malate (black, n = 13 cells) and diAM-succinate + rotenone (turquoise, n = 12 cells). r. Quantification of ΔΨm depolarization expressed as percent change per minute. s. Sarcomere length measured simultaneously in the experiments shown in q. The sample size (n) in all panels represents the number of independent experiments. Data in d-e, h-l, and r-s are mean ± s.e.m. One-way two-tailed ANOVA with Bonferroni correction in d-g, and two-sample two-tailed t-test in h-l and r. * P < 0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

The above findings (Figs. 1a–1g) demonstrate regulation of ATP production by [Ca2+]m, but shed no light on the mechanisms. Fig. 1h–l present experiments designed to identify the nodes of Ca2+ regulation: they probe the [Ca2+]m sensitivity of ATP production powered by diverse metabolic substrates. We examined different carbon sources such as carbohydrates and amino acids that are metabolized through the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle). We also examined lipids, which undergo catabolic steps in the mitochondrial matrix ― they only enter the TCA cycle after β-oxidation, during which they regenerate abundant NADH and FADH2 and are broken down to acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA. We have identified specific carbon substrates that enable the [Ca2+]m-sensitive ATP production and other that do not (Fig. 1j–l). The extensive mitochondrial literature makes no such differentiation between mitochondrial substrates, and regards mitochondrial ATP production as Ca2+-dependent in general (see Supplemental Discussion 2.2–2.3). Our findings show that the entry of glutamate and pyruvate into the TCA cycle is regulated by [Ca2+]m, and it is through this regulation that increasing [Ca2+]m augments ATP production. Glutamate and pyruvate are the metabolic products of amino acids and carbohydrates. Our findings thus identify [Ca2+]m as key in regulating mitochondrial utilization of carbohydrates and amino acids. These findings are consistent with predictions made by earlier work with purified mitochondrial dehydrogenases11,12. Our results, however, supported by NADH measurements (Extended Data Figs. 1d), contradict other published predictions. Our results indicate that neither b-oxidation (of lipids) nor complexes II, III, IV or V (ATP synthase) are significantly regulated by [Ca2+]m despite arguments to the contrary13,14 (see Supplemental Discussion 2.2–2.3).

Sensitivity to [Ca2+]m enables ATP production to ramp up with elevated cellular workload. To test the physiological impact of the [Ca2+]m sensitivity on ATP production we examined ΔΨm in cardiac myocytes under conditions where they are electrically and mechanically active (see Supplementary Video. 1). We provided specific carbon substrates that enable [Ca2+]m-sensitive ATP production (pyruvate), and also substrates that support high-rate ATP production that is insensitive to [Ca2+]m (i.e., membrane-permeant diAM-succinate in combination with rotenone to block ETC Complex I, see Fig. 1k). We first examined the effect of pyruvate on changes in ΔΨm when a single cardiac cell is integrated into an optically clear but mechanically resistive poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) hydrogel (Fig. 1m–o)15. The cell was mechanically coupled to the hydrogel by attaching its surface carbohydrates (glycans) to the hydrogel through a 4-armed PEG-boronic acid crosslinker (Fig. 1o; chemical synthesis in Methods section and Extended Data Fig. 4). Attachment to the PVA gel significantly increased the mechanical load on the cell. The cell stimulation frequency was increased from 1 to 8 Hz. Notably, despite increased ATP consumption at 8 Hz, there was no change in ΔΨm when metabolic substrates that impart Ca2+-sensitivity on ATP production were present (pyruvate). This suggests that when ΔΨm was being maintained by NADH production through Ca2+-sensitive metabolism, the electron transport chain (ETC) could keep ΔΨm hyperpolarized (also see Extended Data Fig. 1d). In stark contrast, ΔΨm depolarized during elevated workload when we supplied substrates that support ATP production that is not boosted by [Ca2+]m (diAM-succinate + rotenone). With these substrates present, upon return to low workload conditions, the rate of ΔΨm depolarization subsides (Fig. 1q–r). These findings indicate that at elevated workload only Ca2+-dependent ATP production is sustainable and does not result in a decline of ΔΨm.

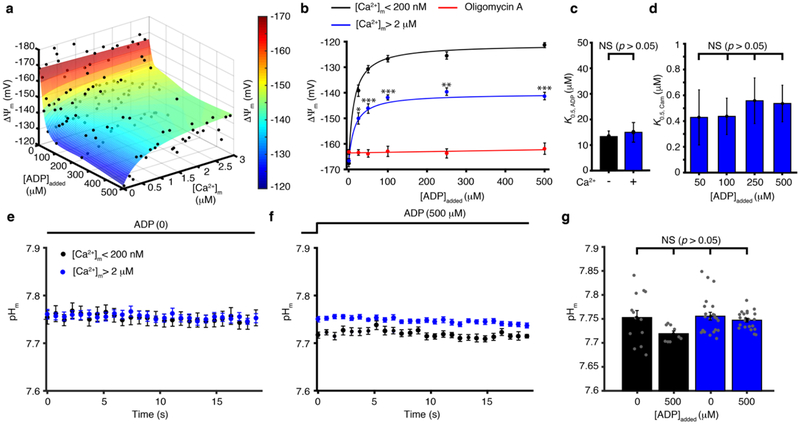

While these findings (Figs. 1m–1s) suggest that [Ca2+]m plays a major physiological role in regulating ΔΨm, they shed no light on the quantitative relationship between the three critical components of ATP production — ADP (the substrate), Ca2+ (the regulator), and ΔΨm (the energy source). These relationships are investigated under conditions where they can be controlled or measured quantitatively using isolated cardiac mitochondria. Our findings are shown in the surface plot in Fig. 2a. The value of ΔΨm mapped in the surface plot represents the points of balance between ETC proton efflux and proton influx via ATP synthase and any other pathway such as the ANT. ATP synthase consumes energy stored in ΔΨm by coupling proton influx to the conversion of ADP to ATP16. ANT consumes energy stored in ΔΨm to exchange ADP with ATP. In the absence of extra-mitochondrial ADP (and hence in the absence of mitochondrial ADP), ATP synthase does not produce ATP and does not consume energy (i.e., there is no proton influx). Under this condition, ΔΨm is stable and energized at about −170 mV. However, when extra-mitochondrial [ADP] is elevated to 500 μM, ATP production is strongly stimulated. Under the same condition, if [Ca2+]m is very low (< 200 nM), then the ATP production leads to significant depolarization of ΔΨm to about −120 mV. However, with an elevated [Ca2+]m (~3 μM) to stimulate NADH production, the same 500 μM [ADP] increases ATP production with a more energetic ΔΨm of -145 mV (Fig. 2a–b). From these data, higher [ADP] augments ATP production but causes depolarization of ΔΨm, with half-maximal depolarization occurring at [ADP] ≈ 12 μM (Fig. 2c). This depolarization is significantly counteracted by an increase in [Ca2+]m, with a half-maximal activation at [Ca2+]m ≈ 500 nM (Fig. 2d). Thus, our findings demonstrate that the [Ca2+]m-sensitive processes that support the utilization of energy in carbon sources to regenerate NADH13,14,17 stimulate higher proton efflux by the ETC and produce a more hyperpolarized ΔΨm. We find that this effect of [Ca2+]m on ΔΨm develops gradually (seconds) and does not follow fast changes in [Ca2+]m (see Extended Data Fig. 5). Importantly, over the full range of the [Ca2+]m- and ADP-regulated ATP production as mapped in Fig. 1a and Fig. 2a, there is no significant change in pHm, as shown in Fig. 2e–g. Under these same conditions there is an approximately 30-fold change of [Ca2+]m, a 20-fold change of [ADP], a 1.5-fold change in ΔΨm, leading to a 3-fold change of ATP production. These observations suggest that although proton movement across the inner membrane enables the ATP synthase to work, ΔΨm itself is the critical regulator of ATP production. Taken together, Fig. 2 shows the importance of [Ca2+]m in enhancing NADH generation, which is critical in keeping ΔΨm hyperpolarized without material influence on pHm.

Figure 2. [Ca2+]m control of ΔΨm.

a. Steady-state ΔΨm is plotted as a function of [Ca2+]m and [ADP]added (n= 22, 18, 25, 20, 21, 27 for 0, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM [ADP]added, respectively). b. Steady-state ΔΨm is plotted as a function of [ADP]added when [Ca2+]m is < 200 nM (black circles, n= 24, 42, 16, 20, 14, 12 for 0, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM [ADP]added, respectively or is > 2 μM (blue circles, n= 15, 6, 11, 5, 6, 10 for 0, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM [ADP]added, respectively) or in the presence of 15 μM Oligomycin A (red circles, n= 12, 18, 17, 18, 18, 14 for 0, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 μM [ADP]added, respectively). Data are fit to a Michaelis–Menten equation. c. [ADP]added at which ΔΨm depolarization is half-maximal for [Ca2+]m <200 nm (−) and >2 μM (+). Each bar shows the K0.5, ADP constant of each of the two fit lines shown in b (K0.5, ADP ± s.e. of fit in μM, fitted sample size is given in b, individual data points shown in a). d. [Ca2+]m at which ΔΨm depolarization is half-maximal for [ADP]added of 50, 100, 250 and 500 μM. Each bar shows the K0.5, Cam constants of each of the four fits shown as surface plot in a (K0.5, Cam ± s.e. of fit in μM, fitted sample size is given in a, individual data points shown in a). e. The time-course of pHm (measured with the fluorescent indicator BCECF - Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1) when [Ca2+]m is <200 nM (black circles, n= 13), or > 2 μM (blue circles, n= 23) in the absence of ADP. f. Same as (e) but in the presence of 500 μM ADP (black circles, n= 9, blue circles, n= 22). g. Quantification of pHm in e-f (n= 13, 9, 23, 22). The sample size (n) in all panels represents the number of independent experiments. Data in b, and e-g are mean ± s.e.m. One-way two-tailed ANOVA with Bonferroni correction in b, d, g and two-sample two-tailed t-test in c. * P < 0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

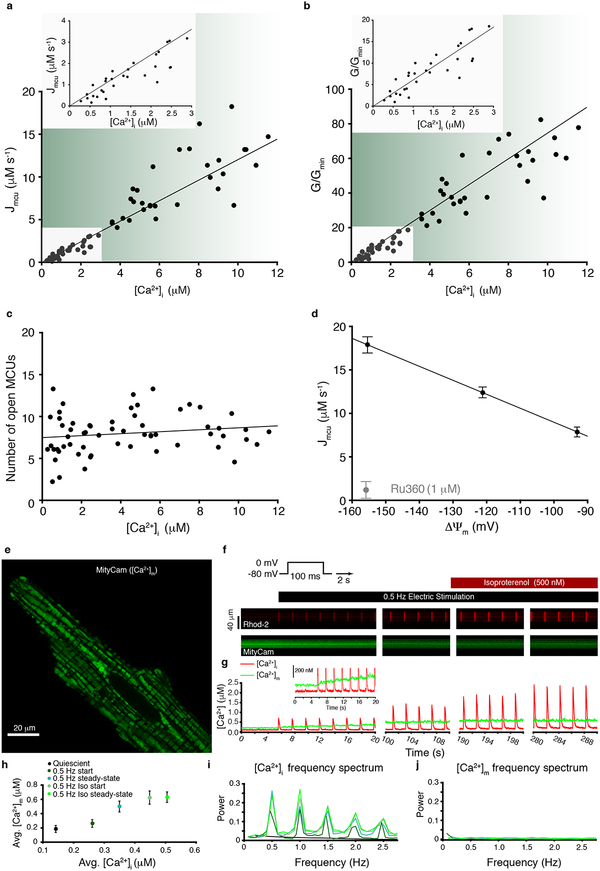

Next, we investigate how physiological activity leads to changes of [Ca2+]m. First, we examine the movement of cytosolic Ca2+ into the mitochondrial matrix. [Ca2+]m increases when Ca2+ enters the mitochondria through the MCU channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane, the only known route of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx1,18–22. By this route, as [Ca2+]i increases to trigger contraction in heart, it also enters the matrix through MCU and thereby elevates [Ca2+]m which, as we saw in Fig.1, boosts ATP production. Measurements of MCU-mediated Ca2+ influx into the cardiac mitochondrial matrix under physiological conditions are shown in Figs. 3a–d. Measuring Ca2+ influx quantitatively at high temporal resolution is challenging at physiological [Ca2+]i because MCUs are sparse (15–65 per cardiac mitochondrion1) and have low single-channel conductance (~0.1 fS at 500 nM [Ca2+]i and ΔΨm = −160 mV, see Methods and Williams et. al., 2013). Nevertheless, we were able to make these biophysical measurements for the first time using stopped-flow fluorometry, where Ru360-inhibitable mitochondrial Ca2+ influx was quantified with millisecond resolution (Extended Data Fig. 6). Fluo-4 or fluo-4FF was used to measure extramitochondrial (i.e., cytosolic) [Ca2+]i, while [Ca2+]m and ΔΨm were measured with fura-2 and TMRM, respectively; all measurements were performed under identical conditions (see Methods). Fig. 3a shows MCU-mediated Ca2+ influx as a function of [Ca2+]i while Fig. 3b shows the relative MCU conductance as a function of [Ca2+]i (see Methods). These measurements are used to obtain the number of open MCU channels as a function of [Ca2+]i (For more details see Supplemental Discussion section 2.4) Our data provide an unambiguous result — the number of open MCU channels remains essentially unchanged over the physiological range of [Ca2+]i in cardiac mitochondria, as shown in Fig. 3c. Furthermore, our data show a surprisingly simple result: As the availability of the conducting ion increases so does its flux, and as ΔΨm becomes less negative, MCU-mediated Ca2+ flux decreases, following the electrochemical driving force for Ca2+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix (see Fig. 3d). The result is surprising because other investigators have reported that the MCU has a [Ca2+]i “threshold”23,24 of ~1 μM for conducting Ca2+, below which no Ca2+ flux is seen. In contrast, we see no threshold, a finding which suggests that a threshold may not be a common feature of all tissues (Supplemental Discussion section 2.5). Furthermore, the [Ca2+]i-gating functions of the MCU23,24 that regulate the number of open MCU channels are not observed by us in cardiac mitochondria under the conditions of these experiments. The putative purpose of the gating/threshold combination is to limit excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ loading23,24. However, our quantitative measurements suggest that this can be achieved by the low number of MCU channels in heart. Furthermore, the behavior of cardiac myocyte MCUs shown here suggests that [Ca2+]m should track [Ca2+]i in heart without excessive weight being given to elevated [Ca2+]i transients.

Figure 3. [Ca2+]m dynamics and MCU Ca2+ conductance.

a. Stopped-flow measurement of the MCU-dependent Ca2+ influx (Jmcu) scaled to a liter of cytosol (see Methods and ref7). Jmcu (μM ·s−1) is plotted as a function of measured [Ca2+]i (n= 63 independent experiments, each with [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]m and ΔΨm measured). Inset shows zoomed-in region between 0 and 3 μM [Ca2+]i. Linear least-squares fit to the filled circles is shown (slope = 1.2.). Stopped-flow data are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6. b. MCU conductance (G) for each of 63 experiments shown in (a) normalized to the minimal conductance (Gmin) of each dataset (G/Gmin) plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i where G = JmcuC*10−6/(ΔΨm*10−3-(RT/2F)*ln([Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m), (see Methods). Inset shows zoomed-in region between 0 and 3 μM [Ca2+]i. Linear least-squares fit line to the filled circles is shown (slope = 6.1). c. Number of open MCUs per mitochondrion (NPo) plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i. Taken from (b) after dividing by the number of mitochondria per liter cytosol (see Methods) and dividing by the [Ca2+]i-dependent unitary conductance of MCU7,18. Linear least-squares fit to the filled circles is shown (slope = 0.116, intercept = 7.48). d. MCU Ca2+ influx (Jmcu, μM ·s−1) plotted as a function of ΔΨm. [Ca2+]i and ΔΨm were measured as in (a) but using a multi-well plate reader. ΔΨm was set by using a K+ gradient and the K+ ionophore valinomycin (see Methods and Fig. 4). [Ca2+]i was set to 15 μM (n= 4, 7, 4 independent experiments for ΔΨm = −155, −122, −92 mV groups, respectively). MCU blocker Ru360 (1 μM) reduced JMCU to near zero (n= 6 independent experiments). Data are mean ± s.e.m. e. Deconvolved Airyscan confocal image showing the fluorescence of the mitochondrially-targeted Ca2+-sensor MityCam expressed in a cardiomyocyte. Note distinct MityCam localization in individual mitochondria. f. Confocal line-scan images from a cardiomyocyte expressing MityCam; top panels show the fluorescence of Rhod-2 (tripotassium salt, loaded via the patch-clamp pipette); lower panels show MityCam fluorescence. To stimulate [Ca2+]i transients the membrane potential is stepped repeatedly from a holding level of −80 mV to 0 mV every 2 seconds. Isoproterenol (500 nM) is applied at the times indicated. Note that Ca2+ binding reduces the fluorescence of MityCam. g. The time-course of changes in [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m from the respective fluorescence measurements shown in panel f. The experiments shown in panels e-j were repeated independently with similar results (n=9 cells).h. Time-averaged [Ca2+]m vs. time-averaged [Ca2+]i (n= 9 cells). Data are mean ± s.e.m. i-j. Fast Fourier transform showing the frequency composition of [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m signals (n= 9 cells).

Part two of our examination of the movement of cytosolic Ca2+ into the mitochondrial matrix focuses on simultaneous measurements of [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m under physiological conditions in patch-clamped ventricular myocytes. The physiological context of cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ is shown in Fig. 3e–j in myocytes patch-clamped and stimulated by 100-ms depolarizations at 0.5 Hz. [Ca2+]m was measured with a mitochondrially-targeted fluorescent Ca2+ sensor, MityCam, (characterized in Extended Data Fig. 7), while Rhod-2 salt loaded into the cytosol via the patch pipette reported [Ca2+]i. The calibrated confocal fluorescence images and signals are shown in Fig. 3e–g. These data show that in the quiescent state, [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m are stable and [Ca2+]m is 50–100 nM higher then [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3g–h). Every depolarization-triggered heartbeat evokes a [Ca2+]i transient (Fig. 3g and i). With repeated depolarizations, the [Ca2+]i transient peaks become larger (as sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content increases with stimulation), while the diastolic [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m both rise slowly (Fig. 3g, j). These findings demonstrate that rhythmic elevations of [Ca2+]i do not cause synchronized large transients of [Ca2+]m (Fig. 3i–j). Instead, a series of cytosolic Ca2+ transients causes a gradual beat-dependent elevation of [Ca2+]m. Thus, in a physiological context, a single heartbeat cannot materially change [Ca2+]m. Rather, a series of heartbeats and their pattern control [Ca2+]m and ATP production.

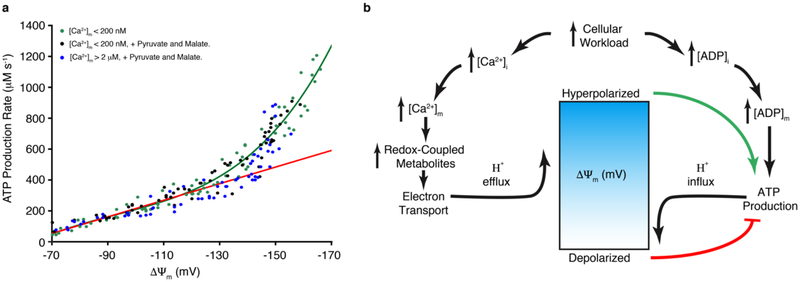

The clear role of ΔΨm in regulating ATP production, as shown in Figs. 1–2, is examined quantitatively in Fig. 4. Isolated mitochondria were used in these experiments without high-energy substrate, and were depleted of [Ca2+]m for the initial experiments to minimize the [Ca2+]m -dependent contributions. ΔΨm was controlled independently using valinomycin (a K+ ionophore25) in combination with the K+ gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane; ΔΨm was measured and calibrated with TMRM. With all other factors held constant, ATP production was measured as a function of ΔΨm (see Methods). The resulting findings were unexpected. The curve is concave-upward and shows ATP production accelerating as ΔΨm is increasingly hyperpolarized. To examine further the role of [Ca2+]m, the experiment was repeated at high [Ca2+]m and in the presence of high-energy substrate – with all other conditions held constant. Fig. 4a shows that the relationship was virtually identical in high and low [Ca2+]m – confirming our earlier findings that [Ca2+]m does not directly regulate the ATP synthase (Fig. 1k–l).

Figure 4. ΔΨm control of ATP production.

a. The dependence of ATP production (μM/s) on ΔΨm in the absence of carbon substrate and at [Ca2+]m < 200 nM (green circles, n= 77 independent experiments), or with Pyruvate and Malate at [Ca2+]m < 200 nM (black circles, n= 72 independent experiments), or with Pyruvate and Malate at [Ca2+]m > 2 μM (blue circles, n= 65 independent experiments). ΔΨm was set by using a fixed K+ gradient and the K+ ionophore valinomycin (see Methods). The green line is an empirical fit to the data and the red line corresponds to expected ATP production based on linear changes in driving force (ΔGdrive), where ATP production rate = k • ΔGdrive and the kinetic coefficient (k) is assumed to be constant (see Supplementary Information section 1.1 for more details). b. Proposed model for voltage-energized Ca2+-sensitive ATP production. In this physiological feedback mechanism, mitochondrial ATP production is tuned to cellular ATP consumption by cellular Ca2+ signals and ADP availability. Both [Ca2+]i and [ADP]i rise during an increase in workload but have opposing effects on ΔΨm. A rise in cytosolic [ADP] increases ADP availability to ATP synthase, which couples ATP production to influx of H+ into the mitochondrial matrix. A rise in [Ca2+]i increases [Ca2+]m to stimulate the production of redox-coupled metabolites that provide energy for the electron transport chain (ETC) to pump protons (H+) out of the mitochondrial matrix. The dynamic balance of H+ influx by ATP synthase and H+ efflux by the ETC sets ΔΨm, which in the presence of [Ca2+]m will be hyperpolarized, thus, energizing ATP production by ATP synthase.

The IMM voltage-dependence of ATP production by ATP synthase (Complex V) in cardiac mitochondria reveals how protons in the intermembrane space use ΔΨm to power the synthase. Up to now, the known voltage dependence of bacterial ATP synthase has been used as the model system for predicting the behavior of the mammalian ATP synthase25–28. The bacterial ATP synthase produces 0 ATP at 0 mV, and ATP production rises sigmoidally, saturating at −120 mV, with half-saturation at −70 mV25–28. Our data in Fig. 4a is the first report of the voltage-dependence of the mammalian ATP synthase. The shape of the curve and its quantitative characteristics should provide clues into the inner workings of the mammalian ATP synthase. The shape of the curve is a surprise ― it is concave-upwards over the range of ΔΨm examined and does not suggest saturation. Additionally, in sharp contrast with the bacterial ATP synthase, which reaches 37% of its maximal rate at −65 mV25, the mammalian enzyme produces essentially no ATP until an apparent “threshold” voltage of -65 mV is reached. Thermodynamically, the −65 mV threshold suggests that when ΔΨm is more positive than about −65 mV, there is insufficient energy when protons are bound to the synthase to enable ATP to be synthesized. Furthermore, Fig. 4a also shows the increase in ATP production from −70 to −120 mV. Over this voltage range, the rates of ATP production are consistent with the need for 3 protons transported across the IMM by ATP synthase for every ATP molecule synthesized from ADP (red line in Fig. 4a). This follows a “standard model” of harnessing the energy of protons moving through the voltage field across the inner membrane to produce ATP28. On the other hand, at potentials more negative than −120 mV, the measured rates of ATP production exceed the red line. The slope of the data over the range −130 to −170 rises to approximately four times that predicted by the red line. This finding is thus completely unexpected and has not been seen before. Mechanistically, we do not know why ATP production increases so quickly with ΔΨm. We propose that the number of protons that move across the voltage field of the IMM via a single ATP synthase cycle can increase as ΔΨm hyperpolarizes negative to −120 mV. In which case, this high rate of ATP production at more hyperpolarized IMM voltages is due to an increase in the stoichiometry of the ATP synthase (more protons moved per ATP produced), which we call “adaptive stoichiometry”. A second possibility is a nonlinear voltage-dependent increase in the “rotation” of the C-ring of ATP synthase with unchanged stoichiometry, which may be termed “adaptive kinetics”. While one or more of these hypothesized voltage-sensitive mechanisms may apply, we do not yet have experimental techniques that enable us to determine which. Nevertheless, it is clear from the data that the voltage-dependence shown in Fig. 4a differs radically from the measured voltage-dependence of the bacterial ATP synthase. This feature may represent an improvement of metabolic adaptation in mammalian systems. It enables a higher rate of ATP production when it is needed and when the energy is available in the form of ΔΨm. Additional discussion of several likely important features of the mammalian ATP synthase is presented in the Supplemental Discussion section 2.6 and in Supplemental Information section 1.1.

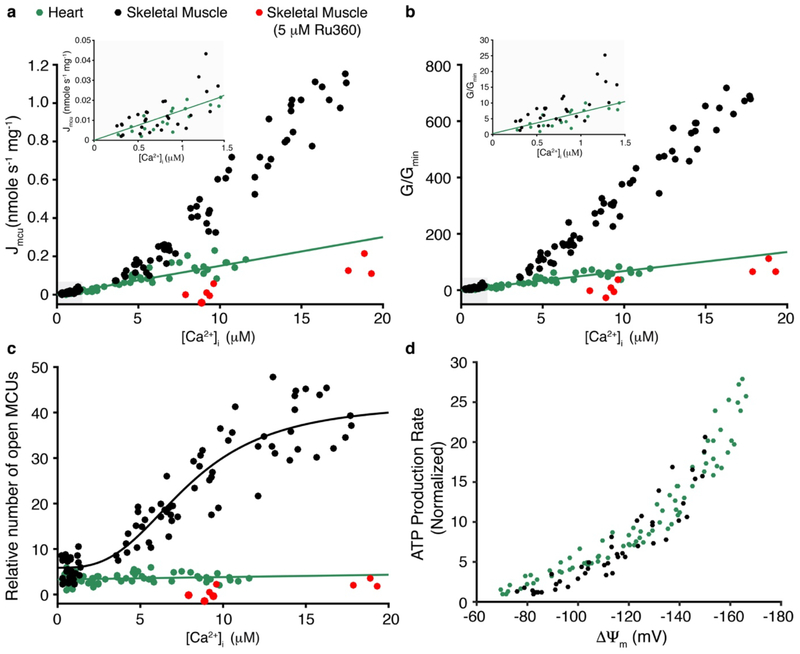

Our examination of ATP production and its regulation in the heart is diagrammed in Fig. 4b. We found that mitochondrial production of ATP is controlled by ΔΨm, which is sensitive to [ADP] and to [Ca2+]m. We propose that the ΔΨm dependence of ATP production that we show here in cardiac mitochondria is a general feature of mammalian mitochondria. In support of this view, we carried out similar experiments with skeletal muscle mitochondria, and found the same ΔΨm dependence of ATP production (see Extended Data Fig. 8). Nevertheless, these and other and tissue-specific mitochondrial features need further study. For example, in virtually all tissues the basal and dynamic ATP consumption rates are likely to be different2,3. Furthermore, the dynamic [Ca2+]i signals are also generally cell-type- and tissue-specific29,30. Moreover, we and others show that MCU properties vary significantly in different eukaryotic species19 and tissues1 (see Extended Data Fig. 8 that compares our measurements of cardiac MCU to skeletal muscle MCU). Taken together, our findings and the developed quantitative tools lay the foundation to reshape our thinking and approach to energy utilization under physiological and pathophysiological conditions and in mitochondrial diseases.

METHODS

Mitochondria isolation.

6–10-week-old Sprague-Dawley male rats (250–300 gr, from ENVIGO, USA, stain code # 002) were anesthetized using Isofluorane (10 minutes) and administered heparin IP (720 U per Kg, 5 minutes). A thoracotomy and fast excision of the heart was performed, with removal of the atria. The ventricles were minced in ice cold isolation buffer (IB) containing (in mM): KCl 100, MOPS 50, MgSO4 5, EGTA 2, NaPyruvate 10, K2HPO4 10. The minced tissue was washed repeatedly with IB until clear of blood. The remainder of the preparation was conducted in a cold room (4 °C). 20 mL of IB containing tissue was transferred to a Potter-Elvehjem grinder and homogenized at high speed for 2 seconds followed by 4 repetitive homogenizations with a 1-micron clearance pestle on low. The homogenate was centrifuged for 8 min at 600g after which the supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube. The pellet was resuspended with 10 mL IB and centrifuged for 8 min at 600g. The second supernatant was pooled with the first and centrifuged again for 8 min at 600g. The final supernatant was transferred to a clean centrifuge tube and spun at 3200g for 8 min. The resulting supernatant was discarded and the pellet is the mitochondria sample. The mitochondria were then resuspended in resuspension buffer base solution (RB) consisting of (in mM): KCl 100, MOPS 50, K2HPO4 1 or 10. The RB1 was RB supplemented with NaPyruvate (10 mM), EGTA (10 or 40 μM), and with the acetoxymethyl (AM) ester forms of either a calcium indicator (Rhod-2 AM (3 μM) or Fura-2 AM (5 μM)) or the pH indicator BCECF AM (10 μM). Mitochondria were loaded with the respective dye for 30 min after which they were pelleted at 3200g for 8 min. The pellet was then resuspended in RB2 which is RB supplemented with NaPyruvate (1 mM) and depending on the experiment; either EGTA (40 μM) or 10 μM Fluo-4 was used. Mitochondria in RB2 are pelleted at 3200g for 8 min. A third and final resuspension and pelleting was done using RB3 consisting of RB and either EGTA (40 μM) or 10 μM Fluo-4. The concentration of mitochondria in mg/mL was quantified by Lowry assay with a typical rat heart yielding ~15 mg mitochondrial protein. Mitochondria isolated from this preparation exhibited typical respirometry outputs (Qubit MitoCell 37 °C - State 3: 178.4 ± 10.6 nmol/mg/min, State 4 + Oligomycin A: 11.6 ± 1.02 nmol/mg/min, RCR 12.3 ± 1.46, Substrate 1 mM Pyruvate and 0.5 mM Malate) and (Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer 37 °C - State 3: 110.2 ± 11.5 nmol/mg/min, State 4 + Oligomycin A: 11.6 ± 2.6 nmol/mg/min, RCR 9.4 ± 1.6, Substrate 10 mM Glutamate and 5 mM Malate). Skeletal muscle mitochondria were isolated from the gastrocnemius muscle using the protocol described above but with the following modification. The harvested muscle tissue was minced in ice cold isolation buffer (IB) containing 5 mM of EGTA and no pyruvate. Mitochondria isolated from this preparation exhibited typical respirometry outputs (Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer 37 °C - State 3: 87 ± 7.4 nmol/mg/min, State 4 + Oligomycin A: 9.2 ± 2.9 nmol/mg/min, RCR 9.5 ± 1.2, Substrate 10 mM Glutamate and 5 mM Malate). All procedures and protocols involving animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Isolation of adult cardiomyocyte.

Isolated ventricular myocytes were obtained from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g, from ENVIGO, USA, stain code # 002). Rats were deeply anesthetized by inhalation of vaporized isoflurane and heparinized (720 U per Kg). Ten minutes after heparin was injected, the heart was rapidly excised and rinsed with ice cold 500 μM EGTA isolation buffer containing 130 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.33 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM D-glucose, 10 mM Taurine, 25 mM HEPES, and 0.01 unit/mL insulin (pH 7.4) (adjusted with NaOH). The aorta was quickly cannulated for Langendorff perfusion. The heart coronary arteries were perfused at 37 °C for 2 min with EGTA isolation buffer and then perfused for 7 min with isolation buffer supplemented with 1 mg/mL collagenase (type II; Worthington Bio- chemical, USA), 0.06 mg/mL protease (XIV), 0.06 mg/mL Trypsin, and 0.3 mM CaCl2. The ventricles were cut down, minced, and kept in the same buffer for additional 6 minutes at 36° C. The myocardium was dispersed to form a cell suspension, which was then filtered through a Nylon mash filter (300 μm). The filtrate was spun at 180 g and the cell containing pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer supplemented with 2 mg/mL BSA. Ca2+ is gradually added at 4 increments of 0.4 mM every 12 minutes. Cells were allowed to pellet by sedimentation, resuspended in NT solution, and were used within 4 hours of isolation. All procedures and protocols involving animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

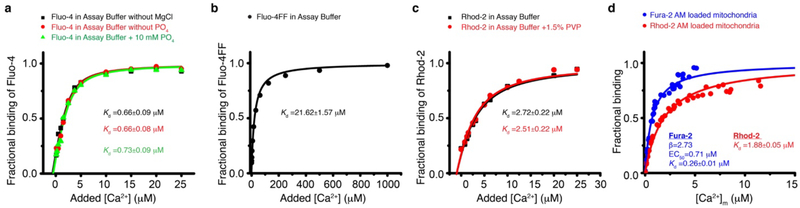

Measuring the dissociation constants of Ca2+ indicators.

Fluorescence titration curves with Ca2+ were done to measure the [Ca2+] dissociation constants (Kd) of the indicators used (see Extended Data Fig. 2). The Kd of Fluo-4, Fluo-4FF, and Rhod-2 are measured in the relevant experimental buffers using the method by Eberhard M & Erne P31 as shown in Extended Data Fig. 2 a–c. The Kd of Fura-2 and Rhod-2 loaded via their acetoxymethyl (AM) form into the matrix of isolated mitochondria was measured using the Ca2+ ionophore Ionomycin to equilibrate the free mitochondrial Ca2+([Ca2+]m) with the free extra mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]extra, free), (see Extended Data Fig. 2 d).

Measurements of mitochondrial ATP production & [Ca2+]m.

Measurements of mitochondrial ATP production rate and [Ca2+]m were carried out using a BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar plate reader. Rhod-2 AM loaded mitochondria (0.1 mg per mL) are mixed in ATP production assay buffer (AB) consisting of (in mM): KGluconate 130, KCl 5, K2HPO4 1 or 10, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, EGTA 0.04, BSA 0.5 mg/mL, D-Luciferin (Sigma) 0.005, Luciferase (Roche) 0.001 mg/mL. A luminescence standard curve was performed daily over a range of 100 nM to 1 mM ATP with Oligomycin A (15 μM) treated mitochondria, see Extended Data Fig. 1 a–c. The mitochondria were incubated for 2 minutes prior to the start of the assay with Ca2+ (0–50 μM added) and metabolic substrates. Assays were initiated by injection of 100 μL of ADP (50–500 μM) and luciferin/luciferase in AB to bring the final volume to 200 μL. Luminescence signal is recorded for 20 seconds with 1 second integration. In the absence of ADP only ~10 nM ATP is present in the system. An automated sequence was used to assess each well first for luminescence then subsequently for fluorescence, see Extended Data Fig. 1 a–c for representative traces and analysis. ATP production rates are scaled to a liter of cardiomyocyte cytosol (μM s−1, scaling is based on 80 gram mitochondrial protein per liter cardiomyocyte cytosol)7. [Ca2+]m was measured via Rhod-2 fluorescence (excitation: 554 ± 4 nm, emission: 607 ± 24 nm) with a FMax and FMin obtained daily (FMin at 2 mM EGTA, FMax at 2 mM Ca2+). The quantitative [Ca2+]m values were obtained according to the following equation (1):

| (1) |

Were Kd,R2m = 1.74 μM, obtained as described above, also see Extended Data Fig. 2 d. Critical for each isolated mitochondria test was the purification of ADP stocks. Briefly; Na ADP (Sigma) or K ADP (Sigma) were dissolved in a reaction buffer containing (in mM): Na ADP or K ADP 500, Glucose 10, Tris 50, MgCl2 5, and 50 U/mL Hexokinase, pH 7.4. The reaction was given 1 hour at 30 °C after which the solution was filtered using filtered centrifugal tubes with a molecular cut-off of 3,000 Dalton (Amicon Ultra, Milipore, Ireland). The concentration of the ADP stock was re-assessed by measuring absorbance at 260 nm and using an extinction coefficient of 15,400 M−1cm−1 according to the Beer–Lambert law.

Measurements of ΔΨm & [Ca2+]m.

Measurements of ΔΨm and [Ca2+]m were carried out using either a BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar plate reader or Stopped-Flow instrument (SF-300×, KinTek, USA). In these experiments, Fura-2 AM loaded mitochondria (0.25 mg per mL) were mixed in ATP production assay buffer (AB) without BSA and supplemented with 0.5 μM TMRM (2 μM TMRM per 1 mg per mL mitochondrial protein). The CLARIOstar was used for experiments testing ΔΨm depolarization over a range of both Ca2+ (0–50 μM added) and ADP (0–500 μM) using Pyruvate (1 mM) and Malate (0.5 mM) for substrate. After 2 minutes of incubation with substrate and Ca2+, assays were initiated by injection of 100 μL of ADP to bring the final volume to 200 μL. TMRM (excitation: 546 ± 4 nM and 573 ± 5 nm, emission: 619 ± 15 nm) and Fura-2 (excitation: 335 ± 6 nM and 380 ± 6 nm, emission: 490 ± 15 nm) fluorescence were measured within the same well for 20 seconds. Stopped flow measurements were done using the same buffers and 3 distinct protocols. Protocol 1 - mitochondria were pre-incubated for 2 minutes with Ca2+ then stimulated with 500 μM ADP. Protocol 2 - mitochondria with [Ca2+]m of less than 50 nM were simultaneously stimulated with 500 μM ADP and high Ca2+. Protocol 3 - mitochondria with [Ca2+]m of less than 50 nM were pre-mixed with 500 μM ADP, followed by mixing with high Ca2+ while keeping constant 500 μM ADP. All 3 protocols were executed for 20 seconds. TMRM (excited with 546 nm and 573 nm, 593–643 nm emission) and Fura-2 (excited with 340 nm and 380 nm, 491–501 nm emission) signals were measured in parallel for each injection set. The [Ca2+]m was obtained according to the following equation (2):

| (2) |

where, Kd,F2m = 0.26 μM, was obtained as described above (see Extended Data Fig. 2 d). The β (F380,min/F380,max) was measured daily (typically 2.5–2.8). Fura-2 RMax (340 nm/380 nm) and RMin were obtained daily for both Stopped-Flow and plate-reader assays. TMRM signal was calibrated using the ratiometric Scaduto & Grotyohann method32 as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 e–h. The protonophore 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) was used to depolarize ΔΨm to different levels to generate the standard curves of TMRM calibration as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 e–h.

Measurements of pHm & [Ca2+]m.

Measurements of pHm and [Ca2+]m were carried out using a BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar plate reader. In these experiments, Rhod-2 AM and BCECF AM co-loaded mitochondria (0.25 mg per mL) were mixed in AB. The mitochondria were incubated for 2 minutes prior to the start of the assay with Ca2+ (0–50 μM added) and Pyruvate (1 mM) and Malate (0.5 mM). Assays were initiated by injection of 100 μL of ADP (0 or 500 μM) in AB to bring the final volume to 200 μL. BCECF (excitation: 430±5 nm and 500±5 nm, emission: 540±10 nm) and Rhod-2 signals were recorded for 20 seconds. FMax and FMin was obtained daily for each indicator (BCECF: FMin pH = 4.5, FMax pH= 9). The pKa of BCECF-AM in isolated mitochondria was determined to be 7.26 using mitochondria treated with 1 μM FCCP and allowed to equilibrate with the extra-mitochondrial pH using an array of different pH buffers (see Extended Data Fig. 1 i–j for excitation and emission spectra). Acid-loading experiments using iso-osmotic solutions of Na Acetate are done to ensure BCECF-AM remained within the mitochondria, see Extended Data Fig. 1 k.

Measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx.

Measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx were carried-out using Stopped-Flow instrument (SF-300×, KinTek, USA). For physiological extra-mitochondrial free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]extra,free < 4 μM) experiments, Fura-2 AM loaded mitochondria (4 mg per ml) in uptake assay buffer (uAB) were rapidly mixed by the Stopped-Flow with equal volume of uAB supplemented with Ca2+. Thereby, a step-wise increase of [Ca2+]extra,free occurs within 1 ms from about 50 nM to as high as 3 μM. The uAB consisted of (in mM): KCl 130 (Trace Select, Sigma Aldrich), HEPES 20, Pyruvic acid 10, Malic acid 5, K2HPO4 1,MgCl2 1, and Fluo-4 0.003 (Pentapotassium Salt, Thermo Fisher), pH 7.2 with KOH. Na+ was not added to the uAB or to the isolation buffer in which the mitochondria were suspended and kept (i.e., RB). The uAB is made with analytical grade deionized water (OmniSolv® LC-MS, Sigma Aldrich) and contained less than 50 nM of residual [Ca2+]. Under these experimental conditions, Fluo-4 is the single significant buffer of extra-mitochondrial Ca2+ (See Extended Data Figs. 2 and 6). Therefore, Fluo-4 fluorescence can be used for measurements of [Ca2+]extra,free and the total extra-mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]extra,Total) both in units of μM using the following equation (3):

| (3) |

where FFluo-4,Min is the fluorescence intensity of Fluo-4 in the absence of calcium (measured with 2 mM of EGTA in the uAB), FFluo-4,Max is the fluorescence of the calcium saturated Fluo-4 (measured with 2 mM [Ca2+] in the uAB). The Ca2+ dissociation constant of Fluo-4 (Kd,Fluo4) is taken as 0.72 μM (See Extended Data Fig. 2). Fluo-4 binds to Ca2+ with 1-to-1 stoichiometry allowing the calculation of [Fluo-4:Ca2+] in units of μM using the following equation (4):

| (4) |

The sum of [Ca2+]extra,free and the concentration of Ca2+ bound to Fluo-4 ([Fluo-4:Ca2+]) yield the [Ca2+]extra,Total using the following equation (5):

| (5) |

The first derivative of the time-dependent measured [Ca2+]extra,Total is the mitochondrial Ca2+ influx. In these experiments, mitochondrial Ca2+ influx is completely blocked by 1 μM of Ru360, and is therefore identified as MCU flux (Jmcu) and scaled to a liter of cardiomyocyte cytosol (μM s−1 scaling is based on 80 gram mitochondrial protein per liter cardiomyocyte cytosol)7. To measure [Ca2+]m mitochondria were loaded with Fura-2 AM (calibration described above) and loaded with TMRM to measure ΔΨm in mV (calibration described above). The total MCU Ca2+ conductance (Gmcu) was obtained from the measurements of Jmcu, [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]m, and ΔΨm according to the following equation (6):

| (6) |

where Vi is the myoplasm volume 18 pL and is the Nernst reversal potential for Ca2+. The number of open MCU channels per mitochondrion are obtained from the measurements of Jmcu, [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]m, and ΔΨm according to the following equation (7):

| (7) |

where gmcu is single channel MCU conductance (gmcu, max = 3.25 pS, Km. mcu = 19 mM [Ca2+]i7,18,33). For experiments where [Ca2+]extra,free is stepped to values between 4–12 μM, Fluo-4FF (Kd,Fluo4FF = 21.6 μM, see Extended Data Fig. 2) was used instead of Fluo-4. These experiments were carried-out with a lower concentration of mitochondria for 5 seconds (1 mg per ml post mix) with uAB supplemented with 10 μM of EGTA. Since EGTA is saturated with Ca2+ when the [Ca2+]extra,free is greater than 3.5 μM, these experiments were analyzed in the same manner as the experiments with Fluo-4. Fluo-4 and Fluo-4FF were excited at 485 nm, 520–542 emission. Fura-2 were excited with 340 nM and 380nm, 491–501 emission. TMRM was excited at 546 nM and 573 nm, 593–643 emission.

Valinomycin ΔΨm clamp: mitochondrial ATP production & mitochondrial Ca2+ influx.

ΔΨm clamp experiments were carried out using a BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar plate reader. The ΔΨm clamp was achieved using valinomycin and a K+ gradient established between the mitochondria and the extra-mitochondrial solution. The extra-mitochondrial solution is varied from 0 to 70 mM while the mitochondrial matrix contained the same amount of K+ at the beginning of each experiment (loaded to a steady-state level of K+ the during the ~3 hour isolation procedure in buffers with 100 mM K+). Two primary buffers were used (in mM): 1) K+ Free Buffer - Gluconic Acid 130, Tetramethyl Ammonium Hydroxide 130, NaH2PO4 1, MgCl2 1, HEPES 20, and EGTA 0.04, pH 7.2 with HCl. 2) High K+ Buffer - KGluconate 130, KCl 5, NaH2PO4 1, MgCl2 1, HEPES 20, and EGTA 0.04 pH, 7.2 with KOH. Buffers were supplemented with D-Luciferin (Sigma) 0.005, Luciferase (Roche) 0.001 mg/mL and 2 μM TMRM per 1 mg per mL mitochondrial protein. Valinomycin was used at a final concentration of 1 μM. For ATP production experiments, a 0.5 μL of 100 mg per mL mitochondria stock was added to a well and re-suspended with a desired amount of high K+ buffer. Three groups were assessed: 1) no substrate and [Ca2+]m < 200 nM, 2) 1 mM pyruvate and 0.5 mM malate with [Ca2+]m < 200 nM, and 3) 1 mM pyruvate and 0.5 mM malate with [Ca2+]m > 2 μM. One injector was then used to add a desired amount of K+ free buffer bringing the volume of the well to 190 μL. An initial TMRM and Fura2 measurement was recorded for 30 s allowing the mitochondria to establish a steady-state ΔΨm. ATP production was initiated with an injection of 10 uL 10 mM ADP (final [ADP] 500 μM) and 2 seconds mixing. Luminescence was measured for 15 seconds with 1 second integration (calibrated daily). A final TMRM measurement was recorded for 15 seconds to ensure no change in ΔΨm over the course of the experiment. For mitochondrial Ca2+ influx vs ΔΨm; the assay was conducted (in the absence of NaH2PO4 and only 10 μM EGTA) with parallel measurement of TMRM and Ca2+ influx using Fluo-4FF (as described above). Ca2+ influx experiments were conducted at a [Ca2+]extra,free of 15–17 μM.

Encapsulation of cardiomyocytes in a resistive hydrogel and measurements of ΔΨm and sarcomere length.

The 14% Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) hydrogel was prepared daily; 14 gr PVA was dissolved in 100 mL NT solution by stirring at 90 °C, spun down at 200 G to remove air, and kept at 25 °C. Equal volumes of isolated cardiomyocyte suspension and PVA hydrogel were mixed on the glass bottom of a plastic imaging chamber (Lab-Tek™ Chambered No 1 Coverglass) and supplemented with cell-to-gel linker to a final concentration of 7.5% linker (i.e., 4-armed PEG-boronic acid, see next section for synthesis details and Extended Data Fig. 4). Prior to mixing of cardiomyocytes with the hydrogel, the cells were incubated for 20 minutes in NT solution (36 °C) supplemented with 50 nM TMRM. This NT solution contained Pyruvate (1 mM) and Malate (0.5 mM), or diAM-Succinate (Succinic acid diacetoxymethyl ester, 10 μM) and rotenone (5 μM), or Succinate (1 mM) and rotenone (5 μM). Incubations and subsequent experiments were done in solutions of the same composition. The hydrogel was given 4 minutes to cross-link after which the plastic imaging chamber was connected to electric stimulation wires and placed inside a microscope stage-top incubator (INU TIZW, TOKAI HIT, Japan). The system was given another 10 minutes of incubation at 36 °C. Confocal measurements of ΔΨm (with TMRM) and simultaneous video-based myocyte sarcomere length measurements were then performed (see supplementary video). Line-scan confocal imaging was carried out, scanning every 10 ms along the traverse axis of a single cardiomyocyte with the 561 laser line (Zeiss 880 Airyscan, Germany). Sarcomere length measurements from a live video image at a frame rate of 300 Hz were carried out using 900B:VSL system (Aurora Scientific, Canada). Field electrical stimulation (40 Volt/cm) to trigger contraction at either 1 Hz or 8 Hz was done using MyoPacer (ION optix, USA).

Synthesis of 4-armed PEG-boronic acid

With stirring, “4-ArmPEG-NH2” (nominal MW 5,000, Biochempeg Scientific; 1 g, ~2.0 × 10−4 mol) was dissolved in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, dried over CaH2; 3 mL). Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 0.550 mL, 3.16 × 10−3 mol) and 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid (0.262 g, 1.58 × 103 mol) were added sequentially to the stirred solution. Thereafter, 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-benzotriazolium hexafluorophosphate 3-oxide (HBTU; 0.599 g, 1.58 × 103 mol) was added and stirring of the reaction mixture was continued under argon. As the reaction progressed, the viscosity of the mixture increased. To achieve steady stirring required incremental additions of dry DMF totaling 20 mL. The reaction mixture was stirred for 20 hr after reagent addition was complete. Thereafter, the mixture was added gradually to vigorously stirred anhydrous ethyl ether (400 mL), whereupon a solid was deposited on the walls of the flask. After stirring for another 20 min, the clear ether solution was decanted and discarded. The deposited solid was rinsed with anhydrous ether (2 × 50 mL). The flask containing the solid residue was purged with a gentle stream of nitrogen to drive off residual ether. The solid residue was dissolved in water (38 mL) to give a slightly turbid, light yellow solution, which was filtered to remove fine particulates. The filtrate was rapidly frozen in liquid N2 and lyophilized to yield a yellow gel. The gel was dissolved in water (8 mL), transferred into dialysis tubing (Float-A Lyser G2, MWCO 100 – 500 Da; Spectrum Laboratories), and dialyzed at room temperature against water (2 L, 18 MΩ·cm). The water was changed three times; each change was made after 24 hr of dialysis. The content of the dialysis tubing was transferred into a flask, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and lyophilized to yield a light-yellow solid (1.282 g, ~92% yield). The product was stored under argon at −20 °C until use. The 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of the 4-armed PEG-boronic acid, recorded in DMSO-d6, is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The spectrum shows the expected resonances corresponding to the phenylboronbic acid moieties at the termini of the PEG arms, at (δ) 8.50 (CONH, broad triplet), 8.18 (BOH, singlet), and 7.82 (CHCH, doublet of doublets). Also observed is the expected broad resonance at 3.50, corresponding to the numerous ethylene linkages in the PEG arms.

Synthesis of succinic acid bis(acetoxymethyl) ester (“diAM succinate”)

Succinic acid bis(acetoxymethyl) ester (structure shown in Supplementary Figure 2) was synthesized by alkylation of the dicarboxylate formed in situ with bromomethyl acetate34,35. In brief, succinic acid was first treated with 2 equivalents of tetra-n butylammonium hydroxide (~40% solution in methanol); volatile solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was dried overnight under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in dry DMSO; to this solution were added 2 equivalents of diisopropylethylaimine and 4 equivalents of bromomethyl acetate. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 70 °C under inert gas for 5 h. The DMSO was removed under vacuum and the residue was taken up in 2 M KHSO4 and extracted with ethyl acetate. The extract was dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and reduced by rotary evaporation to a residue, which was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate in hexane as eluant) to yield the diAM ester as a white solid. The 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of diAM succinate, acquired in CDCl3, is shown in Supplementary Figure 2; the spectrum shows the three expected singlet resonances at (δ) 5.75 (OCH2O), 2.71 (CH2CH2), and 2.12 (CH3CO). High-resolution mass spectrometry (ESI+ mode) showed a base peak at 263.07703, corresponding to [M+H]+, C10H15O8, which requires 263.076695.

Cardiomyocyte [Ca2+]m and [Ca2+]i Measurements.

Cardiomyocytes were perfused throughout experiments with a normal Tyrode’s (NT) bath solution containing (in mM): KCl 5, HEPES 5, glucose 5.5, MgCl2 0.5, NaCl 140, NaH2PO4 0.33, CaCl2 1.8, and Cytochalasin-D 0.08, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. A whole-cell voltage-clamp protocol was used for electric triggering of [Ca2+]i transients (EPC10, HEKA Elektronik, Germany). The membrane potential of a patched cardiomyocyte was stepped from a holding potential of −80 mV to 0 mV for 100 ms every two seconds (0.5 Hz). Microelectrode pipettes (Series Resistance 1.7–2.2 MΩ) were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM): KCl 20, K aspartate 100, tetraethylammonium chloride 20, HEPES 10, MgCl2 4.5, di-sodium ATP 4, di-sodium creatine phosphate 1, Rhod-2, Tripotassium Salt, 0.05, pH 7.2. To simultaneously measure [Ca2+]m and [Ca2+]i, confocal line-scan imaging was carried-out along the transverse axes of a patch-clamped cardiomyoytes. [Ca2+]m was measured using a mitochondrial targeted Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent protein-probe MityCam36 48 hours after adenoviral transduction at 600 MOI (excited by the 488 nm Aragon laser line, emission 505–530 nm), [Ca2+]i was measured with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator Rhod-2 (Tripotassium salt) dialyzed into the cytosol via the patch pipette (excited by the 543 nm Helium-neon laser line, emission 570–650 nm). For calibration of the fluorescence signals, at the end of each trial the patched cardiomyocyte was perfused sequentially with two calibration solution applied via a local micro-perfusion. The first solution was a NT solution devoid of Ca2+ (chelated with 5 mM EGTA) and supplemented with the Ca2+ ionophore, Ionomycin (2 μM). The second was a NT solution with 10 mM Ca2+ supplemented with Ionomycin (2 μM). For more details about the calibration please see Boyman et. al., 201437. [Ca2+]i in μM is obtained from the measured Rhod-2 fluorescence (FRhod) according to the following equation (8):

| (8) |

where FRhod,Min is the fluorescence intensity of Rhod-2 in the absence of Ca2+, FRhod,Max is the fluorescence of the Ca2+ saturated Rhod-2. The Ca2+ dissociation constant of Rhod-2 (Kd,R2) is taken as 2.5 μM (See Extended Data Fig. 2c).

[Ca2+]m in μM is obtained from the measured MityCam fluorescence (FMityCam) according to the following using the following equation (9):

| (9) |

where FMityCam,Max is the fluorescence intensity of MityCam in the absence of Ca2+, FMityCam,Min is the fluorescence of the Ca2+ saturated MityCam. The Ca2+ dissociation constant of MityCam (Kd,MityCam) is taken as 0.2 μM (See Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Luminescence measurements of NADH.

Rhod-2 AM loaded mitochondria (2 mg per mL) were mixed in assay buffer (AB) consisting of (in mM): KGluconate 130, KCl 5, K2HPO4 1 or 10, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, EGTA 0.04, BSA 0.5 mg/mL. The mitochondria were incubated for 2 minutes prior to the start of the assay with nominally free- Ca2+ AB or with AB supplanted with Ca2+ (to raise [Ca2+]m to > 2 μM) and metabolic substrates (either 1 mM pyruvate + 0.5 mM malate, or 1 mM glutamate + 0.5 mM malate, or 0.1 mM palmitoylcarnitine + 2.5 mM malate). The [Ca2+]m was measured, and mitochondria were mixed with 500 μM ADP for one minute before flash frozen by dipping the mitochondria samples in liquid nitrogen. The subsequent procedures and NADH measurements were carried out with a luminescence assay kit according to the manufacturer protocol (Promega, USA). All luminescence and fluorescence measurements were carried out with a BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar plate reader.

Statistics.

All results are presented as mean ± s.e.m. All experiments were repeated independently with at least three separate sample preparations. All experiments require fresh heart tissue, thus statistical analysis was carried out in parallel with experiments to determine when further repetition was no longer required. Statistical analysis was performed using either OriginPro 2018 or Matlab R2016a statistical package all with α = 0.05. Where appropriate, column analyses were performed using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test (for two groups) or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (for groups of three or more). Data fitting convergence was achieved with a minimal termination tolerance of 10−6. P values less than 0.05 (95% confidence interval) were considered significant. All data displayed a normal distribution and variance was similar between groups for each evaluation. Detailed statistical information is included as Supplementary Table linked to the online version of this article.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Mitochondrial ATP production, NADH, voltage, and pH.

a. Time-course of fire-fly Luciferase luminescence signal measured from 9 wells after addition of ATP to each well. In this calibration procedure, different amounts of [ATP] are added to each of the 9 wells as indicated to the right of each line ([ATP]added in μM). The inset shows the measured luminescence versus [ATP]added. Purple shaded area highlights the “Working Range” in which the luminescence signal is a linear function of [ATP]. b. Measurements of [ATP] produced by isolated mitochondria. The calibration procedure shown in (a) is used to convert the measured luminescence signal to [ATP]. The inset shows the measured mitochondrial matrix free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) associated with the ATP measurements in (b). c. ATP production rate based on the linear fit to measurements in (b) and scaled to units of μmol per liter cytosol per second (μM s−1, scaling is based on 80 g mitochondrial protein per liter cardiomyocyte cytosol, for more details see main methods section and Williams et. al., 2014). d. The increase in [NADH] at high [Ca2+]m (>2 μM) relative to [NADH] at low [Ca2+]m (<200 nM) using the indicated combination of carbon substrates (P&M, Pyruvate and Malate; G&M, Glutamate and Malate; PC&M, PalmitoylCarnitine and Malate, n=4 isolated mitochondria preparations per group, * P < 0.05 by two-sided t-test). Data are mean ± s.e.m. [Ca2+]m was measured with Rhod-2. [NADH] measurements were carried out with a luminescence assay kit (Promega, USA, for additional details see Supplementary Methods section 1.4). e. Measured TMRM fluorescence ratio (F573/F46) over the maximal fluorescence ratio from the dataset. Mitochondria are exposed to 2,4-dinitrophenol ([DNP] in μM) as indicated. f. Measured extra-mitochondrial TMRM concentration. g. The mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨm) in mV is obtained from the measurements in (f) according to the method by Scaduto RC & Grotyohann LW 1999. h. ΔΨm and its corresponding TMRM fluorescence ratio. Linear fit lines are as indicated in the inset. The calibration results shown in panels e-h were verified repeatedly on a daily bases with similar results obtained. i. Excitation and emission spectra of mitochondria loaded with BCECF (2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester). 15 independents measurements are shown at the indicated pH levels (1 μM FCCP is used to equilibrate pHm and the extra-mitochondrial buffer pH) with the similar spectrum shown. j. Measured fluorescence ratio from BCECF-loaded mitochondria at the indicated mitochondrial pH values (pHm). The calibration was verified in two mitochondrial preps with similar results obtained k. The pHm measurements following exposure to sodium acetate at the indicated concentrations. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (Results are from 3 independent experiments in each of the indicated 7 concentrations of sodium acetate).

Extended Data Figure 2. Calibration of fluorescence measurements with Ca2+ indicators.

a. Fluo-4 Ca2+ titration curve. Shown is the fraction of Ca2+-bound Fluo-4 bound at the indicated added [Ca2+]. Each point is a triplicate average. Titration curves are carried out in the indicated buffers. b. Fluo-4FF Ca2+ titration curve. Shown is the fraction of Ca2+-bound Fluo-4FF at the indicated added [Ca2+]. Each point is a triplicate average. c. Rhod-2 Ca2+ titration curve. Shown is the fraction of Ca2+-bound Rhod-2 at the indicated added [Ca2+]. Each point is a triplicate average. Titration is done in the absence and presence of PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) in the assay buffer. d. Ca2+ titration curve for Fura-2AM- or Rhod-2AM-loaded mitochondria. Shown is the fraction of Ca2+-bound Fura-2 or Rhod-2 at the indicated free Ca2+ concentration in the mitochondrial matrix ([Ca2+]m). Each point is a triplicate average. 1 μM FCCP and 1 μM of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin are used to equilibrate [Ca2+]m with the extra-mitochondrial free [Ca2+] (i.e., [Ca2+]extra, free). The [Ca2+]extra, free is measured with Fluo-5N. Equations fit to the data for panels a-d are detailed in the main methods section.

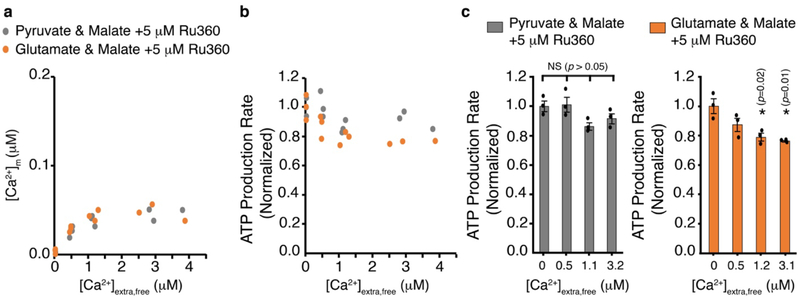

Extended Data Figure 3. Measurements of mitochondrial ATP production when the MCU is blocked by RU360.

a. Measurements of [Ca2+]m in isolated cardiac mitochondria plotted as a function of the measured free extramitochondrial [Ca2+] (i.e., [Ca2+]extra,free) in the presence of the selective MCU blocker RU360 (5 μM). Grey circles are measurements done in the presence of pyruvate (1mM) & malate (0.5 mM). n= 12 independent experiments. Orange circles are measurements done in the presence of glutamate (1 mM) & malate (0.5 mM). n= 12 independent experiments. [Ca2+]m was measured with Fura-2 loaded into the mitochondrial matrix via its acetoxymethyl (AM) ester, [Ca2+]extra,free was measured with Fluo-4 in the extra mitochondrial buffer. b. Measurements of ATP production plotted as a function of the measured [Ca2+]extra,free. The measurements of ATP production rates are normalized to the measurements at nominally zero [Ca2+]extra,free. c. ATP production at the indicated measured [Ca2+]extra,free (from experiments in a-b). Grey bars (left) are ATP production with pyruvate & malate. Orange bars (right) are ATP production with glutamate & malate. Data are mean ± s.e.m. n=3 isolated mitochondria preparations per group, * P < 0.05 by one-way two tailed ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

Extended Data Figure 4. Synthesis of 4-armed PEG-boronic acid.

Abbreviations used: HBTU, 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-benzotriazolium hexafluorophosphate 3-oxide; DIPEA, diisopropylethylamine; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide. The detailed description of the synthesis procedure is in the methods section.

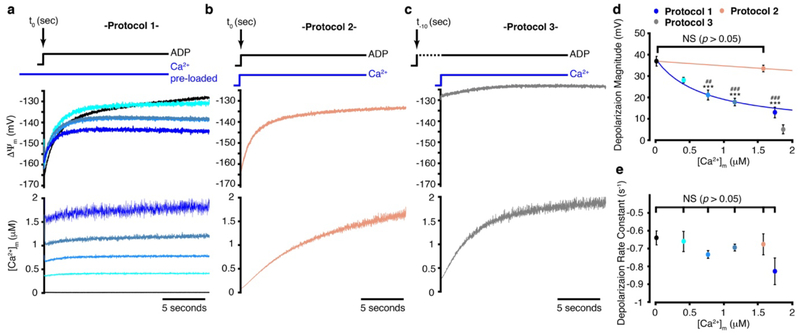

Extended Data Figure 5. ΔΨm kinetics during mitochondrial ATP production.

a. Time-dependent stopped-flow measurement of ΔΨm (upper panel) and of the corresponding [Ca2+]m (lower panel). In this protocol (#1), mitochondria were incubated with increasing extra-mitochondrial free Ca2+ and at t = 0, 500 μM [ADP] was added to the mitochondrial mix. Time-dependent depolarization of ΔΨm is shown as is the near steady-state of [Ca2+]m. Black line: [Ca2+]m= 50 nM (n=8); turquoise: [Ca2+]m= 480 nM (n=3); light blue: [Ca2+]m= 750 nM (n=6); grey-blue: [Ca2+]m= 1.2 μM (n=8); navy blue: [Ca2+]m= 1.7 μM (n=4). b. Same as (a) but in this protocol (#2), [Ca2+]m and [ADP] (500 μM) were increased simultaneously at t = 0 (salmon-colored line, n=7). The injected Ca2+ was set so that the [Ca2+]m achieved a level between 1.5 and 2 μM at 20 s. c. Same as (b) but in this protocol (#3), [ADP] (500 μM) rises 10 seconds before [Ca2+]m was increased at t =0 (grey line, n=6). The injected Ca2+ was set so that the [Ca2+]m achieved a level between 1.5 and 2 μM at 20 s, gray line. In panels a-c the sample size (n) represent the number of independent experiments. d. The magnitude of ΔΨm depolarization in experiments a-c. The sample size is the same as in panels a-c. (* and # denotes statistical comparisonto black and beige data, respectively). e. Exponential rate constant of ΔΨm depolarization in experiments a-b. The sample size is the same as in panels a-b. In d-e data are mean ± s.e.m.* P < 0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 by one-way two-tailed ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Extended Data Figure 6. Stopped-flow measurements of MCU Ca2+ flux and its driving force.

a and e. Representative stopped-flow time-dependent measurements of extra-mitochondrial free Ca2+ (i.e., [Ca2+]extra,free). Mitochondria in uptake assay buffer (uAB) with low [Ca2+]extra,free (<100 nM) are mixed with uAB buffer with added [Ca2+] 1 ms before fluorescence measurements begin. The levels of added [Ca2+] are set so that at the beginning of the measurements the [Ca2+] added will be as indicated in the inset. In (a) [Ca2+]extra,free is measured with Fluo-4 in the uAB and in (e) with Fluo-4FF. b and f. The corresponding time-dependent measurements of matrix free Ca2+ (i.e., [Ca2+]m). Insets showing the corresponding time-dependent measurements of ΔΨm. c and g. The corresponding time-dependent measurements of total extra-mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]extra,Total). The [Ca2+]extra,Total is obtained from the Fluo-4 or Fluo-4FF signals (for more details see the methods section). d and h. MCU Ca2+ influx (Jmcu) is the first derivative of the [Ca2+]extra,Total. The Jmcu is scaled to units of μmol per liter cytosol per second (μM s−1, scaling is based on 80 g mitochondrial protein per liter cardiomyocyte cytosol, for more details see main methods section and Williams et. al., 2014). The shown stopped flow experiments were repeated independently 63 times with similar results at each [Ca2+]extra,free as indicated in Fig 3a.

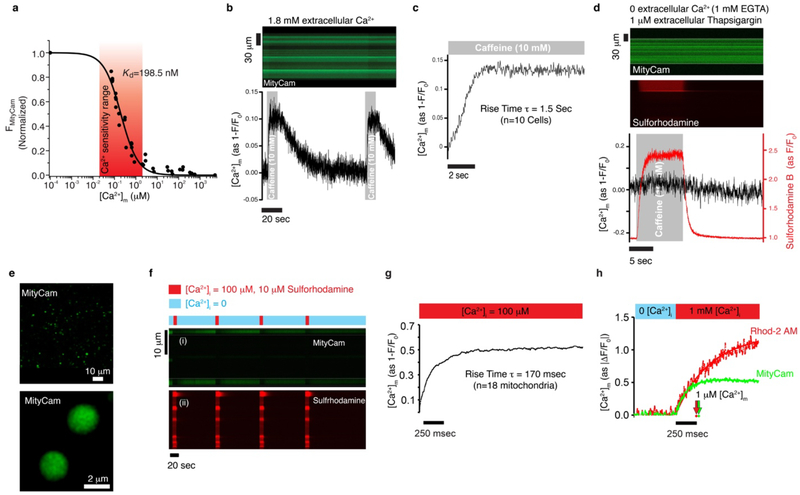

Extended Data Figure 7. Characterization of MityCam; a mitochondrially targeted Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent-protein probe expressed in heart muscle cells.

a. MityCam fluorescence versus [Ca2+]m. Note that Ca2+ binding decreases MityCam fluorescence. Measurements are in saponin-permeabilized cardiomyocytes; [Ca2+]m is set using the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (2 μM). The extracellular (bath) solution contains Rhod-2 (tripotassium salt, cell-impermeant) to measure the bath [Ca2+], a proton ionophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP, 500 nM) to set the mitochondrial pH, rotenone (400 nM) to block the ETC and the production of ROS, and oligomycin (5 mM) to block reverse-mode consumption of ATP by the ATP synthase, pH 7.8. Fit curve is a single-site binding model (n = 30 cells). b. Top: Confocal line-image from an intact cardiomyocyte expressing MityCam. Bottom: The time-course of changes in [Ca2+]m from the confocal fluorescence measurements. Caffeine (10 mM) was applied for 10 seconds via a local micro-perfusion system to rapidly trigger Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum at the indicated times (highlighted with gray shading). The experiment was repeated independently with n=10 cells with similar results. c. The average time-course of changes in [Ca2+]m following caffeine applications. d. Confocal line-image from an intact cardiomyocyte expressing MityCam in a bath solution devoid of Ca2+ (chelated by 1 mM EGTA) and treated with thapsigargin (1 μM) for 10 minutes prior to imaging to deplete the sarcoplasmic reticulum of Ca2+. Top panel shows MityCam fluorescence; middle panel shows the fluorescence of sulforhodamine (sulforhodamine is included in the micro-perfusion solution to indicate the exact duration of 10 mM caffeine application). Lower panel shows the time-course of changes in [Ca2+]m from the confocal fluorescence measurements. Note that throughout the entire time course of the experiment the extracellular solution is devoid of Ca2+ and also contains 1 μM thapsigargin. The experiment was repeated independently with n=11 cells with similar results. e. Confocal images of cardiac mitochondria isolated from MityCam expressing cardiomyocytes. f. Measurements of [Ca2+]m from isolated single mitochondria expressing MityCam. Top panel (i) shows MityCam fluorescence; lower panel (ii) shows sulforhodamine fluorescence, which indicates the duration of micro-perfusion of 100 μM Ca2+ (see bars above the top panel). Mitochondria isolated from MityCam-expressing cardiomyocytes are adhered to a glass coverslip for confocal microscopy measurements. Rapid step (2–3 ms rise time) of [Ca2+] from 0 (1 mM EGTA) to 100 μM is achieved via a micro-perfusion system. Sulforhodamine is included in the solution applied via the micro-perfusion system to indicate when a mitochondrion is exposed to the solution containing 100 μM Ca2+. The experiment in e-f were repeated independently with n=18 mitochondria with similar results. g. the average time-course of changes in [Ca2+]m following the step increase of Ca2+ from 0 to 100 μM (black line). h. Same as (g) but for comparison to another Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent indicator, MityCam-expressing mitochondria are also loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Rhod-2 via its acetoxymethyl (AM) ester form (Rhod-2 AM). To accelerate the rate of [Ca2+]m rise [Ca2+] is raised to 1 mM, all solutions also contain ionomycin (5 μM), FCCP (5 μM), oligomycin (1 μM), pH = 7.8. Green trace for MityCam (n=12 mitochondria) and red for Rhod-2 (n=9 mitochondria). The time at which 1 μM [Ca2+]m is measured is indicated by arrows, this time point is obtained by converting the shown fit lines to units of μM [Ca2+]m. For additional details see Boyman et al., 2014.

Extended Data Figure 8. MCU conductance and voltage dependence of ATP production in heart and skeletal muscle.

a. Measurement of the MCU-dependent Ca2+ influx (Jmcu) (nmole mg−1 s−1) in cardiac mitochondria (green circles, from Fig. 3), skeletal muscle (black circles), and skeletal muscle with Ru360 (5 μM) (red circles) is plotted as a function of measured [Ca2+]i (n = 63, n = 87, and n = 12 independent experiments, respectively, each with [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]m and ΔΨm measured). Linear least-squares fit to the heart mitochondria data is shown (slope = 0.015). b. MCU conductance (G) for each measurement shown in (a) normalized to the minimal conductance (Gmin) of the cardiac dataset (G/Gmin) plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i. Linear least-squares fit line to the heart mitochondria data is shown (slope = 6.1). c. Relative number of open MCUs per mitochondrion plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i. Taken from (b) after dividing by the [Ca2+]i-dependent unitary conductance of MCU and normalized to the minimal number of open MCUs of the cardiac dataset. Linear least-squares fit to the heart mitochondria data is shown (slope = 0.051, intercept = 3.3). For skeletal muscle data under [Ca2+]i of 1.5 μM the measurements were done using stopped flow as described in Extended Data Fig 5. Jmcu at [Ca2+]i above 1.5 μM was collected using a multi-well plate reader with ΔΨm set using a K+ gradient and the K+ ionophore valinomycin. Skeletal muscle data is fit to a modified Hill equation with a K0.5 of 7.9 μM and a Hill coefficient of 2.95. d. The dependence of ATP production on ΔΨm in the absence of carbon substrates and at [Ca2+]m < 200 nM. The measurements of ATP production rates are normalized to the minimal production rate of each data set. Measurements from heart mitochondria are shown in green circles (n= 77, replotted from Fig. 4a), the measurements from skeletal muscle mitochondria are in shown in black circles (n= 45 independent experiments). ΔΨm was set by using a fixed K+ gradient and the K+ ionophore valinomycin (see Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B.M. Polster, C.W. Ward, G.S.B. Williams, R.J. Khairallah, and Mariusz Karbowski for helpful suggestions. This research was supported by American Heart Association grants SDG 15SDG22100002 (to L.B.) and 16PRE31030023 (to A.P.W.); By NIH R01 HL106056 and R01 HL105239 and U01 HL116321 (to W.J.L.); By the Medical Scientist Training Program and Training Program in Integrative Membrane Biology, NIH 2T32GM092237–06 and 5T32GM008181–28 (to A.P.W).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Fieni F, Lee SB, Jan YN & Kirichok Y Activity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter varies greatly between tissues. Nat Commun 3, 1317, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2325 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobus WE Respiratory control and the integration of heart high-energy phosphate metabolism by mitochondrial creatine kinase. Annu Rev Physiol 47, 707–725, doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.47.030185.003423 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z et al. Specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues across adulthood: evaluation by mechanistic model of resting energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr 92, 1369–1377, doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29885 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy E et al. Mitochondrial Function, Biology, and Role in Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Res 118, 1960–1991, doi: 10.1161/RES.0000000000000104 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMauro S & Schon EA Mitochondrial respiratory-chain diseases. N Engl J Med 348, 2656–2668, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022567 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latorre-Pellicer A et al. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA matching shapes metabolism and healthy ageing. Nature 535, 561–565, doi: 10.1038/nature18618 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ & Lederer WJ Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 10479–10486, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300410110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyman L, Williams GS & Lederer WJ The growing importance of mitochondrial calcium in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 11150–11151, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514284112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chance B & Williams GR Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. I. Kinetics of oxygen utilization. J Biol Chem 217, 383–393 (1955). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klingenberg M The ADP-ATP translocation in mitochondria, a membrane potential controlled transport. J Membr Biol 56, 97–105 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denton RM, Randle PJ & Martin BR Stimulation by calcium ions of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphate phosphatase. Biochem J 128, 161–163 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormack JG & Denton RM The effects of calcium ions and adenine nucleotides on the activity of pig heart 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem J 180, 533–544 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glancy B & Balaban RS Role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of cellular energetics. Biochemistry 51, 2959–2973, doi: 10.1021/bi2018909 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormack JG & Denton RM Mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and the role of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of energy metabolism. Dev Neurosci 15, 165–173 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jian Z et al. Mechanochemotransduction during cardiomyocyte contraction is mediated by localized nitric oxide signaling. Sci Signal 7, ra27, doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005046 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell P Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature 191, 144–148 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandes R, Maier LS & Bers DM Regulation of mitochondrial [NADH] by cytosolic [Ca2+] and work in trabeculae from hypertrophic and normal rat hearts. Circ Res 82, 1189–1198 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G & Clapham DE The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427, 360–364, doi: 10.1038/nature02246 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bick AG, Calvo SE & Mootha VK Evolutionary diversity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Science 336, 886, doi: 10.1126/science.1214977 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luongo TS et al. The Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Matches Energetic Supply with Cardiac Workload during Stress and Modulates Permeability Transition. Cell Rep 12, 23–34, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.017 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong JQ et al. The Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Selectively Matches Metabolic Output to Acute Contractile Stress in the Heart. Cell reports 12, 15–22, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y et al. The mitochondrial uniporter controls fight or flight heart rate increases. Nat Commun 6, 6081, doi: 10.1038/ncomms7081 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallilankaraman K et al. MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell 151, 630–644, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.011 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antony AN et al. MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake dictates survival and tissue regeneration. Nat Commun 7, 10955, doi: 10.1038/ncomms10955 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaim G & Dimroth P ATP synthesis by F-type ATP synthase is obligatorily dependent on the transmembrane voltage. EMBO J 18, 4118–4127, doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4118 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen MH & Jafri MS Mitochondrial calcium signaling and energy metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1047, 127–137, doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.012 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimroth P, von Ballmoos C, Meier T & Kaim G Electrical power fuels rotary ATP synthase. Structure 11, 1469–1473 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]