Abstract

Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes involved in signaling pathways that affect hematopoiesis and immune cell functions. JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 play different roles in numerous diseases of the immune system and have also been considered as potential targets for cancer therapy. In the present study, the susceptibility of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib against these three JAKs was elucidated using the 500-ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and free energy calculations based on MM-PB(GB)SA, QM/MM-GBSA (PM3 and SCC-DFTB), and SIE methods. The obtained results revealed that tofacitinib could interact with all JAKs at the ATP-binding site via electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bond formation, and in particular van der Waals interaction. The conserved glutamate and leucine residues (E957 and L959 of JAK1, E930 and L932 of JAK2, and E903 and L905 of JAK3) located in the hinge region stabilized tofacitinib binding through strongly formed hydrogen bonds. Complexation with the incoming tofacitinib led to a closed conformation of the ATP-binding site and a decreased protein fluctuation at the glycine loop of the JAK protein. The binding affinities of tofacitinib/JAKs were ranked in the order of JAK3 > JAK2 ∼ JAK1, which are in line with the reported experimental data.

1. Introduction

Janus kinases (JAKs) are nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, which are classified into four members consisting of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. JAKs are involved in the growth, development, survival, and differentiation of different types of cells. In particular, JAKs play a major role in hematopoiesis and in controlling the cytokine-dependent immune systems.1,2 Cytokine binding to its receptor activates JAKs, which in turn phosphorylates tyrosine within the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor, and then activates signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), promoting dimerization and translocating to the nucleus for turning on the gene expression.3,4 JAK1, JAK2, and TYK2 are ubiquitously expressed in lymphoid cells of mammals, while JAK3 is expressed in hematopoietic cells.5,6 JAK1 is crucial for a different family of cytokine receptors employing gp130 as a co-receptor.7,8 JAK2 is associated with hormone-like cytokines, and it transduces signals through some interferons (IFNs) and gp130-containing receptors. JAK3 is characterized by its exclusive association with cytokine receptors that contain a common γ chain (cc).9 JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 are potential targets for the treatment of hematological disorders such as acute leukemia, myeloproliferative disorder, and lymphoproliferative disorder,10−14 while TYK2 is involved in various autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as a primary immunodeficiency hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome.15,16 In this work, we focus on hematological disorders, therefore only JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors are mentioned.

Dysregulated JAK-STAT functionality can lead to various immune diseases and cancers.17 Therefore, JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 have been characterized as attractive targets for the development of anticancer drugs. The first-generation JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib and tofacitinib approved by the FDA for the treatment of myeloproliferative and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively) bind to the ATP-binding pocket of the tyrosine kinase domain, blocking several downstream signaling cascades.9 Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor for JAK1 and JAK2 by interfering with the recruitment of STATs to cytokine receptors. Additionally, tofacitinib has been reported to potentially inhibit JAK1/2/3 as well as Tyk2 with even higher efficiency.9,18

The complexation between tofacitinib and JAKs (JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3) has been studied experimentally and theoretically. The three-dimensional (3D) structures of JAK1 and JAK3 in complex with tofacitinib were crystallized,19,20 while the X-ray structure of JAK2 was co-crystalized with pyrrole-3-carboxamide.21 They have sequence identity from CLUSTALW22 in a range of 46–55% and sequence similarity of 61–71% (see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). By superimposition on the three complexes (Figure 1A), the active conformation of JAKs, in which the activation loop (A loop) is closed into the active site, is found in the ligand-bound form.9 The amino acid sequences in the glycine-rich loop (G loop), hinge region, catalytic loop, and A loop are conserved to some extent (Figure 1B). These conserved regions have a sequence identity of 65–78% (Figure S1).22 The proline residue in the hinge region of JAKs could introduce the rigidity into this region.23 The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of tofacitinib against JAKs was in the range of 1.7–3.7, 1.8–4.1, and 0.75–1.6 nM for JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3, respectively.20,24−26 On the other hand, another type of Janus kinase, TYK2, showed the IC50 values for tofacitinib to be higher than the above-mentioned three types of JAKs, with the values being 16 and 34 nM.26,27 The last 2 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggested that the residues E903 and L905 of JAK3 strongly stabilize the tofacitinib binding.28 The pharmacophore model of docked tofacitinib with JAK3 showed one hydrogen bond (HB) donor, two HB acceptors, and one hydrophobic interaction.29

Figure 1.

(A) Superimposition of JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 crystal structures (tofacitinib and pyrrole-3-carboxamide represented in gray and blue stick models) in which the highly conserved sequences of the four important parts: catalytic loop, hinge region, glycine-rich loop (G loop), and activation loop (A loop), are shown by a large worm style structure, where their sequence alignment is given in (B). (C) Tofacitinib binding at the active site of JAKs and its chemical structure (D).

In this study, we aimed to investigate the tofacitinib susceptibility (Figure 1C,D), including binding patterns, intermolecular interactions, and binding affinity against the three JAKs in terms of drug–target interaction using MD simulations extensively performed up to 500 ns with three randomly selected initial velocities (1.5 μs in total for each complex). In addition, the protein motion of apo and holo forms of JAK (without and with tofacitinib bound) was calculated using principal component analysis (PCA). The obtained information could be used as theoretical guidance for further developing novel anti-JAK(s) drug candidates.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. System Stability of Simulated Models

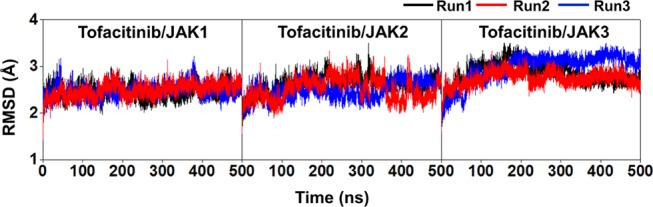

The stability of the tofacitinib/JAK complexes was considered in terms of root-mean-square displacement (RMSD, Figure 2) plotted along the simulation time of 500 ns. In each system, the RMSD results from the three independent simulations showed similar patterns. The RMSD values of JAK1 and JAK2 complexes continuously increased at the first 50 ns and stably maintained at a fluctuation of ∼2.0–3.5 Å, whilst RMSD values of JAK3 complexes continuously increased at 150 ns and maintained at a fluctuation of ∼2.50–3.50 Å until the end of simulation time. The change in the fluctuation pattern of JAK1 and JAK3 complexes was lower than that of JAK2. The RMSD value of JAK2 was increased after 300 ns and reached equilibrium at ∼350 ns for simulations (run1 and run3). Although the situation was different in run2, the high fluctuation was found in a similar pattern upon simulation time. Thus, the last 150 ns MD trajectories of each system (considered as an equilibrium state, which was also supported by the number of hydrogen bonds and contact atoms involved in the drug–protein interactions plotted upon simulation time in Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4) were used for further analysis.

Figure 2.

All-atom RMSD plot of the tofacitinib/JAK(s) complexes. The data are derived from the three independent simulations with different initial velocities.

2.2. Key Binding Residues

To investigate the key binding amino acids involved in tofacitinib binding to the three JAKs, the ΔGbind,residue calculations based on the MM/GBSA method were performed on the 100 snapshots taken from the last 150 ns of all simulations. The energy contributions of a particular residue and drug orientation at the binding pocket of the three focused JAKs are displayed in Figure 3. The negative and positive ΔGbind,residue values represent the ligand stabilization and destabilization, respectively. The contributions from the residues 839–1045 in JAK1, 839–1000 in JAK2, and 815–990 in JAK3 are presented. Note that ΔGbind,residue values of tofacitinib binding with each JAK from the three independent simulations were not significantly different.

Figure 3.

(A) Per-residue decomposition free energy (ΔGbindresidue) of the domain of three JAKs for the binding of tofacitinib from three independent simulations and the binding orientation of tofacitinib inside the binding pocket drawn from the MD snapshot. The lowest and highest energies are ranged from dark magenta to yellow, respectively. The electrostatic and van der Waals (vdW) energy contributions are given in (B) using the data derived from the average three independent simulations.

The hydrophobic residues V889, F958, L959, and L1010 of JAK1, V863 and L983 of JAK2, and V836 and L956 of JAK3 exhibited the energy contribution of <−1.0 kcal/mol (Figure 3A). Interestingly, tofacitinib was strongly stabilized by leucine residue located in the hinge region, in which the binding energies were observed as follows: −1.92 ± 0.01 kcal/mol from L959 of JAK1 (light pink), −1.66 ± 0.10 kcal/mol from L932 of JAK2 (green), and −1.50 ± 0.27 kcal/mol from L905 of JAK3 (green). In addition, L828 (green) and L956 (magenta) from JAK3 gave the binding free energies lower than L855 (green) and L983 (light magenta) from JAK2 as well as G882 (green) and L1010 (pink) from JAK1. These findings agree well with a previous study reporting that the two hydrophobic regions, pyrrolopyrimidine and piperidine rings, of tofacitinib can tightly interact with L905, L956, and L828 of JAK3.28 It was mentioned that the hydrophobic interaction plays an important role in tofacitinib/JAK1(3) complexation, especially hydrophobic residues V889, F958, L959, and L1010 of JAK1.28,30,31 In agreement with these former studies, our calculations revealed that the pyrrolopyrimidine and piperidine rings of tofacitinib were sandwiched between the hydrophobic residues of the N-terminal lobe, including (i) V889, A906, V938, and F958 for JAK1, (ii) V863 and V911 for JAK2, and (iii) V836, V884, L905, and A853 for JAK3. In addition, the methyl group of the piperidine ring pointed toward the C-terminal lobe, making van der Waals contacts with S963 and L959 for JAK1, L932 and S936 for JAK2, and C909 for JAK3.

Apart from hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bond formations with the glutamate located in the hinge region also played an important role in stabilizing tofacitinib. Strong electrostatic contributions for drug binding were observed as follows: −2.17 ± 0.03 kcal/mol from JAK1 E957 (light pink); −2.23 ± 0.06 kcal/mol from JAK2 E930 (light pink); and −2.08 ± 0.03 kcal/mol from JAK3 E903 (pink) (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, the electrostatic contribution (ΔEelec + ΔGsolv,polar) of E957 in JAK1, E930 in JAK2, and E903 in JAK3 showed the energy contribution value less than van der Waals contribution (ΔEvdw + ΔGsolv,nonpolar). Since these glutamic residues in three types of JAKs are the acidic amino acid, they can form interaction with some basic groups of pyrrolopyrimidine and piperidine rings (such as imino group).28 The number of HBs of all systems along simulation times are summarized in Figure S3. They exhibited very strong HBs with the pyrrolopyrimidine core structure of tofacitinib as shown in Figure 4A (99.9 ± 0.0 and 94.8 ± 0.2% for JAK1 E957 and L959; 99.9 ± 0.0 and 89.7 ± 1.7% for JAK2 E930 and L932; 100 ± 0.0 and 80.9 ± 1.2% for JAK3 E903 and L905). This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that E957 of JAK1, as well as E903 and L905 residues of JAK3, played an important role in stabilizing the core structure of pyrrolopyrimidine binding at the ATP-binding site.28,32 Moreover, the pyrrolopyrimidine core structure of the other first analogues of the drug, including ruxolitinib,33 oclacitinib,34 and baricitinib35 was also strongly stabilized by hydrogen bonding in the hinge region of JAKs in a manner similar to tofacitinib binding.36

Figure 4.

Percentage of hydrogen bond occupation with the two important residues, glutamate, and leucine, in the hinge region of JAKs. The data were derived from the last 150 ns of the three different simulations determined using the criteria between the hydrogen bond donor (HD) and hydrogen acceptor (HA) as follows: (i) ≤3.5 Å for distance and (ii) ≥120° for the angle.

2.3. Solvent Accessibility and the Number of Surrounding Atoms

To characterize the solvent accessibility toward the ligand-binding pocket, the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) calculation on the amino acid residues within the 3.5 Å sphere of tofacitinib was performed. The obtained results are summarized in Figure 5A. It can be seen that the SASA values for the JAK1 and JAK2 complexes of ∼200–500 Å2 were somewhat higher than that for the JAK3 system (by ∼100 Å2). Without drug binding (apo form), more water molecules were detected at the active site as seen by enhanced SASA values to ∼600–900 Å2 for JAK2/3 and ∼500–800 Å2 for JAK1. From the plot of radial distribution function (RDF) in Supporting Information Figure S5, there are ∼0.9 and ∼0.5 water molecules stabilized by the N19 nitrogen of tofacitinib, as seen by a sharp peak at 3.5 Å in JAK1 and a board peak at 3.3 Å in JAK1 and JAK2/3, respectively. A similar phenomenon was found in the simulations of JAK1 and JAK3, including crystal waters in the systems. Note that a water molecule was detected close to this nitrogen in the crystal structures of tofacitinib/JAK1 and tofacitinib/JAK3 with a distance of 2.5 and 3.0 Å.

Figure 5.

(A) SASA on the residues and (B) number of surrounding atoms within the 3.5 Å sphere of tofacitinib from the three independent simulations.

Furthermore, the number of surrounding atoms of tofacitinib (using the criteria of any atom within the 3.5 Å sphere of the ligand) were counted. Figure 5B shows that the number of surrounding atoms around tofacitinib was ranked in the order of JAK3 (∼18 atoms) > JAK1 ∼ JAK2 (∼15 atoms). For % occupation in the number of contact atoms in Figure S6, in JAK2 and JAK3 tofacitinib showed the contact atoms with all four conserved regions (G loop, hinge, catalytic loop, and A loop), while no contact atom with the catalytic loop was detected in JAK1. Instead, drug contacted with K908 of JAK1 nearby the G loop (69%). Again, the glutamate and leucine residues at the hinge region (JAK1 E957 and L959; JAK2 E930 and L932; JAK3 E903 and L905) strongly supported the drug binding (>70%). Interestingly, all three atom types (carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen) of L828 in the G loop and the oxygen atom of A966, the residue adjacent to the DFG motif in the activation loop (Figure S1), could contact with tofacitinib in JAK3. The residue A966 has hydrophobicity more than G993 in JAK2.36 These findings suggested that the binding pocket residues in JAK3 were close-packed. In other words, tofacitinib was deeply buried and fitted well in the ATP-binding site of JAK3 greater than the others.

2.4. Binding Affinity of Tofacitinib

End-point ΔGbind calculations with MM-PBSA, MM-GBSA, QM/MM-GBSA (PM3 and SCC-DFTB methods treated on ligand atoms), and solvated interaction energy (SIE) were applied to predict and compare the binding affinity of tofacitinib/JAK complexes on the same series of 100 MD snapshots used in ΔGbind,residue calculation. The ΔGbind values averaged over the three different simulations are given in Table 1 in comparison to the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of tofacitinib from the previous studies.

Table 1. Predicted ΔGbind of Tofacitinib in Complex with Three Kinds of JAKs from the MM-PB(GB)SA, QM/MM-GBSA, and SIE Methods Compared to the Reported IC50 Values from Previous Works20,24,26,27.

| ΔGbind | JAK1 | JAK2 | JAK3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGbind(MM-PBSA) | –16.93 ± 0.87 | –15.34 ± 0.80 | –19.04 ± 0.71 |

| ΔGbind(MM-GBSA) | –20.61 ± 0.86 | –19.34 ± 1.79 | –24.47 ± 0.69 |

| ΔGbind(PM3/MM-GBSA) | –21.69 ± 3.01 | –18.24 ± 0.60 | –26.88 ± 2.00 |

| ΔGbind(SCC-DFTB/MM-GBSA) | –31.75 ± 2.74 | –28.55 ± 1.00 | –40.15 ± 2.31 |

| ΔG(SIE) | –8.74 ± 0.42 | –8.96 ± 0.43 | –9.09 ± 0.37 |

| IC50 (nM) | |||

| (20) | 81 | 80 | 34 |

| (26) | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| (27) | 3.7 | 3.1 | 0.8 |

| (24) | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.75 |

| this workb | NA | 26.9 | 20.6 |

| ΔGExpa (kcal/mol) | |||

| (20) | –9.67 | –9.68 | –10.18 |

| (26) | –11.58 | –11.44 | –11.99 |

| (27) | –11.50 | –11.60 | –12.40 |

| (24) | –11.96 | –11.92 | –12.44 |

Experimental binding free energies (ΔGExp) were converted from the reported IC50 values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation of ΔG = RT ln(IC50).37

The inhibitory activities of tofacitinib against the kinase activity of JAK2 and JAK3 from this study were determined by the enzyme-based assay, where the IC50 curves are shown in Figure S7.

Both MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA approaches gave the same order of ΔGbind as follows: JAK3 (−19.04 and −24.47 kcal/mol) < JAK1 (−16.93 and −20.61 kcal/mol) ∼ JAK2 (−15.34 and −19.34 kcal/mol). Overall, the estimation of binding affinity from the QM/MM-GBSA method is significantly better than MM-GBSA.38 In our study, both PM3/MM-GBSA and SCC-DFTB/MM-GBSA methods also gave the similar phenomena of binding free energies with the MM/PB(GB)SA as ΔGbind of JAK3 (−26.88 and −40.15 kcal/mol) < JAK1 (−21.69 and −31.75 kcal/mol) ∼ JAK2 (−18.24 and −28.55 kcal/mol). The ΔGbind results predicted from the SIE method also gave the highest binding affinity for the tofacitinib/JAK3 complex. The obtained information suggested that the drug could inhibit this protein target more efficiently than JAK1 and JAK2, in correspondence with the magnitude of experimental ΔGbind values (JAK3 −10.18 to −12.44 kcal/mol < JAK1 −9.67 to −11.96 kcal/mol ∼ JAK2 −9.68 to −11.92 kcal/mol) converted from IC50 values (JAK3 of 0.75–34 nM < JAK1 of 1.7–81 nM ∼ JAK2 of 1.8–80 nM).20,24,26,27

2.6. Motion of Proteins

PCA or covariance analysis is a statistical method used to identify the most relevant collective motions along MD trajectories.39 Among the three complexes, the tofacitinib/JAK3 system with the lowest binding free energy was chosen to investigate the motion of apo and holo proteins. The last 150 ns MD trajectories were used for PCA analysis. The PCA screen plot of PC modes is plotted in Figure 6A. The covariance matrix of atomic fluctuation data was diagonalized to build a two-dimensional (2D) projection on the first two PCs (Figure 6B). The first principle component PC1 is shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

(A) PCA screen plot of PC modes and (B) the 2D projection of two PC modes, PC1 and PC2, derived from MD trajectories of the JAK3 apo form (left) and the tofacitinib/JAK3 complex (right). (C) PC1 Porcupine plot of the apo form and holo form of JAK3, where the arrow head indicates the direction of motion, while the length indicates the amplitude of motion.

The first twenty PC mode values showed the accumulated variances of apo and holo forms in Figure 6A. Tofacitinib bound at the ATP-binding site of JAK3 could increase the percentage of variances of PC1 from 12.32 to 21.66% with a lower distribution in 2D projection on the first two PCs (Figure 6B). In Figure 6C, the G loop region of the apo JAK3 protein was flipped away to the upper site with a high amplitude. Interestingly, when the ATP-binding site of JAK was accommodated by tofacitinib, the motion of the JAK3’s G loop was flipped into the binding site resulting in a closed conformation, similar to the motion of Akt, a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase, driven by butoxy mansonone G binding.40 Thus, a high fluctuation of protein motions likely observed in apo JAK can be dramatically reduced upon tofacitinib binding with a consequence of structural change from open conformation to closed conformation.

3. Conclusions

In this research, the drug–target interactions of tofacitinib with the three JAKs (JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3) at the molecular level were extensively studied using 500 ns MD simulations with three different initial velocities (1.5 μs in total). The obtained results revealed that tofacitinib interacted with all kinds of JAKs at the active site. The two important Glu and Leu residues of JAK1 (E957 and L959), JAK2 (E930 and L932), and JAK3 (E903 and L905) in the hinge region strongly stabilized tofacitinib binding via the formation of two strong hydrogen bonds. Most of the key binding residues provided the ligand stabilization through the vdW interaction, whilst such Glu highly contributed to tofacitinib via electrostatic attraction. Tofacitinib fitted well within the active site of all protein targets, in particular JAK3, as clearly seen by the higher number of surrounding atoms. All MM-PB(GB)SA, QM/MM-GBSA, and SIE binding free energy calculations predicted that the binding affinity of tofacitinib toward JAK3 was greater than that toward the other two JAKs, in good agreement with the reported IC50 values. Additionally, tofacitinib binding could feasibly reduce the fluctuation of the protein motion, in particular at the glycine loop of proteins, inducing the closed conformation. Our results provided a better understanding of how tofacitinib inhibits JAKs at the molecular level, and the trajectories from this study can be further used for finding more potent inhibitors against JAKs such as pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Computational Methods

4.1.1. System Preparation

The 3D structures of JAK1 and JAK3 were obtained from the protein data bank (PDB codes: 3EYG(19) and 3LXK(20)). All missing residues (residues 946–950 in JAK1 and 1038–1044 in JAK3) were completed using the SWISS-MODEL.41 The obtained homology model was then validated by the Ramachandran plot using PROCHECK.42 The Supporting Information in Figure S2 showed that both models were mostly found in the favored region with a value of 92.6% for JAK1 and 92.1% for JAK3. Since there is no co-crystal structure of the JAK2-tofacitinib complex, the pyrrole-3-carboxamide in JAK2 (PDB code: 4D0X(21)) was replaced by tofacitinib via superimposition with the tofacitinib/JAK1(3) complex using the UCSF Chimera package.43 The protonation states of all ionizable amino acids were characterized using PROPKA 3.0.44

4.1.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Each tofacitinib/JAK complex was prepared by all-atom MD simulations with three different initial velocities using the pmemd CUDA in AMBER1645 in periodic boundary conditions with the isobaric-isothermal (NPT) ensemble. Details of simulations were as described for other biological systems.46−48 The FF14SB49 and GAFF50 force fields were applied for protein and tofacitinib, respectively. To generate the partial charges of inhibitor, the 3D structure of tofacitinib was optimized by the HF/6-31(d) level of theory as per previous studies51−53 using the Gaussian09 program.54 The electrostatic potential (ESP) charges and restrained ESP (RESP) charges of the ligand were generated using parmchk of AMBER16. The systems were soaked in the boxes of explicit water using the TIP3P model (∼10 750 molecules for JAK1, ∼10 696 molecules for JAK2, and ∼10 439 molecules for JAK3). The time step was set as 2 fs at a constant pressure of 1 atm.55 The short-range cutoff of 12 Å was used for nonbonded interactions, while long-range electrostatic interactions were treated by Ewald’s method.56 Temperature and pressure were controlled by the Berendsen algorithm.57 The SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms.58 The simulated models were heated up to 310 K with the relaxation time for 100 ps. The temperature was controlled by a Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 2.0 ps. Finally, the unrestrained NPT simulation was performed for 500 ns. The MD trajectories were recorded every 500 steps for analysis. The RMSD analysis of each system was performed using all atoms. The intermolecular HB occupation, SASA, the number of contacts, and the motion of proteins were evaluated using the CPPTRAJ module.59 Besides, the MM-PB(GB)SA and QM/MM-GBSA ΔGbind and ΔGbind,residue were calculated by the MM/PBSA.py module.60 Note that in the QM/MM approach, tofacitinib was quantum-mechanically treated by the semiempirical method PM3 and the self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method (SCC-DFTB),61 whereas the remaining region was described by molecular mechanics using the FF14SB force field. The same sets of MD snapshots were used to predict the ΔGbind based on the solvated interaction energy (SIE) method.62 SIE is an end-point physics-based scoring function for predicting binding affinities in aqueous solution, which is calculated by an interaction energy contribution, desolvation free energy contribution, electrostatic component, and nonpolar component.62

4.2. Experimental Section

4.2.1. Janus Kinase Inhibitory Activity Assay

The IC50 of tofacitinib toward the kinase activity of JAK2 and JAK3 were measured using the ADP-Glo Kinase Assay Kit (Promega). The reaction contains 2.5 ng/μL of JAK2 (Sigma-Aldrich, SRP0171) or JAK3 (Sigma-Aldrich, SRP0173) with 5 μM ATP and 2 ng/μLpoly(glu·tyr) in a buffer (40 mM Tris–HCI pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin). The reactions were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, 5 μL of the ADP-Glo reagent was added and incubated for 40 min. After that, 10 μL of kinase detection reagent was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the luminescence measurement of the ATP product was performed using a microplate spectrophotometer (Synergy HTX Multi-Mode reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT). All assays were performed in triplicate. The inhibition (%) of tofacitinib was calculated in comparison to control the reaction with no inhibitor. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Thailand Research Fund (grant number RSA6280085). K.S. thanks the Science Achievement Scholarship of Thailand for the Ph.D. scholarship, the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund, GCUGR1125623024D), and the Overseas Presentations of Graduate Level Academic Thesis from Graduate School. K.S. thanks the ASEAN-European Academic University Network (ASEA-UNINET) for a short research visit. The Computational Chemistry Center of Excellence and the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC-2) are acknowledged for facilities and computing resources. We also thank Dr. Kowit Hengphasatporn for the artwork.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b02800.

Alignment and identity table of amino acid sequences of three kinds of JAKs (whole sequences and conserved regions); Ramachandran plot of the JAK1 model and JAK3 model; number of hydrogen bonds formed between tofacitinib and three JAKs; number of contacts of atoms within the 3.5 Å sphere of tofacitinib; radial distribution function (RDF) of water oxygens around the N19 nitrogen of tofacitinib; percentage of the number of contact atoms within 3.5 Å sphere of tofacitinib for three JAKs; IC50 curves of tofacitinib against the kinase activity of JAK2 and JAK3 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Schindler C.; Levy D. E.; Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20059–20063. 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang W.; Xin M.; Chen P.; Gui L.; Zhao X.; Tang F.; Wang J.; Liu F. Identification of 4-(2-furanyl)pyrimidin-2-amines as Janus kinase 2 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 75–83. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan C.; Kreis S.; Margue C.; Behrmann I. Jaks and cytokine receptors - An intimate relationship. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1538–1546. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J. J.; Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity 2012, 36, 542–550. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka K.; Saharinen P.; Pesu M.; Holt V. E. T.; Silvennoinen O.; O’Shea J. J. The Janus kinases (Jaks). Genome Biol. 2004, 5, 253 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven R. J.; Xu L.; Weiner T. M.; Fridell Y.-W.; Dent G. A.; Srivastava S.; Varnum B.; Liu E. T.; Cance W. G. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases Expressed in Metastatic Colon-Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 1995, 60, 791–797. 10.1002/ijc.2910600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasbinder M. M.; Alimzhanov M.; Augustin M.; Bebernitz G.; Bell K.; Chuaqui C.; Deegan T.; Ferguson A. D.; Goodwin K.; Huszar D.; Kawatkar A.; Kawatkar S.; Read J.; Shi J.; Steinbacher S.; Steuber H.; Su Q.; Toader D.; Wang H.; Woessner R.; Wu A.; Ye M.; Zinda M. Identification of azabenzimidazoles as potent JAK1 selective inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 60–67. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese B.; Au-Yeung C. K.; Herrmann A.; Diefenbach S.; Haan C.; Kuster A.; Wortmann S. B.; Roderburg C.; Heinrich P. C.; Behrmann I.; Muller-Newen G. Long term association of the cytokine receptor gp130 and the janus kinase Jak1 revealed by FRAP analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39205–39213. 10.1074/jbc.M303347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Nielsen T. E.; Clausen M. H. FDA-approved small-molecule kinase inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 422–439. 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springuel L.; Hornakova T.; Losdyck E.; Lambert F.; Leroy E.; Constantinescu S. N.; Flex E.; Tartaglia M.; Knoops L.; Renauld J. C. Cooperating JAK1 and JAK3 mutants increase resistance to JAK inhibitors. Blood 2014, 124, 3924–3931. 10.1182/blood-2014-05-576652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atak Z. K.; Gianfelici V.; Hulselmans G.; De Keersmaecker K.; Devasia A. G.; Geerdens E.; Mentens N.; Chiaretti S.; Durinck K.; Uyttebroeck A.; Vandenberghe P.; Wlodarska I.; Cloos J.; Foa R.; Speleman F.; Cools J.; Aerts S. Comprehensive Analysis of Transcriptome Variation Uncovers Known and Novel Driver Events in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003997 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullighan C. G.; Zhang J. H.; Harvey R. C.; Collins-Underwood J. R.; Schulman B. A.; Phillips L. A.; Tasian S. K.; Loh M. L.; Su X. P.; Liu W.; Devidas M.; Atlas S. R.; Chen I. M.; Clifford R. J.; Gerhard D. S.; Carroll W. L.; Reaman G. H.; Smith M.; Downing J. R.; Hunger S. P.; Willman C. L. JAK mutations in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 9414–9418. 10.1073/pnas.0811761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T.; Toki T.; Kanezaki R.; Xu G.; Terui K.; Kanegane H.; Miura M.; Adachi S.; Migita M.; Morinaga S.; Nakano T.; Endo M.; Kojima S.; Kiyoi H.; Mano H.; Ito E. Functional analysis of JAK3 mutations in transient myeloproliferative disorder and acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia accompanying Down syndrome. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 141, 681–688. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnafi V.; Le Noir S.; Lhermitte L.; Gardin C.; Legrand F.; Vallantin X.; Malfuson J. V.; Ifrah N.; Dombret H.; Macintyre E. JAK1 mutations are not frequent events in adult T-ALL: a GRAALL study. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 148, 178–179. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K.; Laurence A.; O’Shea J. J. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 273–287. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesgidou N.; Eliopoulos E.; Goulielmos G. N.; Vlassi M. Insights on the alteration of functionality of a tyrosine kinase 2 variant: a molecular dynamics study. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i781–i786. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J. J.; Schwartz D. M.; Villarino A. V.; Gadina M.; McInnes I. B.; Laurence A. The JAK-STAT Pathway: Impact on Human Disease and Therapeutic Intervention. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 311–328. 10.1146/annurev-med-051113-024537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K.; Jesson M. I.; Li X.; Lee J. L.; Ghosh S.; Alsup J. W.; Warner J. D.; Tanaka M.; Steward-Tharp S. M.; Gadina M.; Thomas C. J.; Minnerly J. C.; Storer C. E.; LaBranche T. P.; Radi Z. A.; Dowty M. E.; Head R. D.; Meyer D. M.; Kishore N.; O’Shea J. J. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 4234–4243. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N. K.; Bamert R. S.; Patel O.; Wang C.; Walden P. M.; Wilks A. F.; Fantino E.; Rossjohn J.; Lucet I. S. Dissecting Specificity in the Janus Kinases: The Structures of JAK-Specific Inhibitors Complexed to the JAK1 and JAK2 Protein Tyrosine Kinase Domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 387, 219–232. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrencik J. E.; Patny A.; Leung I. K.; Korniski B.; Emmons T. L.; Hall T.; Weinberg R. A.; Gormley J. A.; Williams J. M.; Day J. E.; Hirsch J. L.; Kiefer J. R.; Leone J. W.; Fischer H. D.; Sommers C. D.; Huang H. C.; Jacobsen E. J.; Tenbrink R. E.; Tomasselli A. G.; Benson T. E. Structural and Thermodynamic Characterization of the TYK2 and JAK3 Kinase Domains in Complex with CP-690550 and CMP-6. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 400, 413–433. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasca M. G.; Nesi M.; Avanzi N.; Ballinari D.; Bandiera T.; Bertrand J.; Bindi S.; Canevari G.; Carenzi D.; Casero D.; Ceriani L.; Ciomei M.; Cirla A.; Colombo M.; Cribioli S.; Cristiani C.; Della Vedova F.; Fachin G.; Fasolini M.; Felder E. R.; Galvani A.; Isacchi A.; Mirizzi D.; Motto I.; Panzeri A.; Pesenti E.; Vianello P.; Gnocchi P.; Donati D. Pyrrole-3-carboxamides as potent and selective JAK2 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 4998–5012. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D.; Higgins D. G.; Gibson T. J. Clustal-W - Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucet I. S.; Fantino E.; Styles M.; Bamert R.; Patel O.; Broughton S. E.; Walter M.; Burns C. J.; Treutlein H.; Wilks A. F.; Rossjohn J. The structural basis of Janus kinase 2 inhibition by a potent and specific pan-Janus kinase inhibitor. Blood 2006, 107, 176–183. 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Boluda J. C.; Gomez M.; Perez A. JAK2 inhibitors. Med. Clin. 2016, 147, 70–75. 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changelian P. S.; Flanagan M. E.; Ball D. J.; Kent C. R.; Magnuson K. S.; Martin W. H.; Rizzuti B. J.; Sawyer P. S.; Perry B. D.; Brissette W. H.; McCurdy S. P.; Kudlacz E. M.; Conklyn M. J.; Elliott E. A.; Koslov E. R.; Fisher M. B.; Strelevitz T. J.; Yoon K.; Whipple D. A.; Sun J. M.; Munchhof M. J.; Doty J. L.; Casavant J. M.; Blumenkopf T. A.; Hines M.; Brown M. F.; Lillie B. M.; Subramanyam C.; Shang-Poa C.; Milici A. J.; Beckius G. E.; Moyer J. D.; Su C. Y.; Woodworth T. G.; Gaweco A. S.; Beals C. R.; Littman B. H.; Fisher D. A.; Smith J. F.; Zagouras P.; Magna H. A.; Saltarelli M. J.; Johnson K. S.; Nelms L. F.; Des Etages S. G.; Hayes L. S.; Kawabata T. T.; Finco-Kent D.; Baker D. L.; Larson M.; Si M. S.; Paniagua R.; Higgins J.; Holm B.; Reitz B.; Zhou Y. J.; Morris R. E.; O’Shea J. J.; Borie D. C. Prevention of organ allograft rejection by a specific Janus kinase 3 inhibitor. Science 2003, 302, 875–878. 10.1126/science.1087061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. M.; Jesson M. I.; Li X. O.; Elrick M. M.; Funckes-Shippy C. L.; Warner J. D.; Gross C. J.; Dowty M. E.; Ramaiah S. K.; Hirsch J. L.; Saabye M. J.; Barks J. L.; Kishore N.; Morris D. L. Anti-inflammatory activity and neutrophil reductions mediated by the JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor, CP-690,550, in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. J. Inflammation 2010, 7, 41 10.1186/1476-9255-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M.; Yamazaki S.; Yamagami K.; Kuno M.; Morita Y.; Okuma K.; Nakamura K.; Chida N.; Inami M.; Inoue T.; Shirakami S.; Higashi Y. A novel JAK inhibitor, peficitinib, demonstrates potent efficacy in a rat adjuvant-induced arthritis model. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 133, 25–33. 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. L.; Cheng L. P.; Wang T. C.; Deng W.; Wu F. H. Molecular modeling study of CP-690550 derivatives as JAK3 kinase inhibitors through combined 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and dynamics simulation techniques. J. Mol. Graph. Modell. 2017, 72, 178–186. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehringer M.; Forster M.; Pfaffenrot E.; Bauer S. M.; Laufer S. A. Novel Hinge-Binding Motifs for Janus Kinase 3 Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Structure-Activity Relationship Study on Tofacitinib Bioisosteres. CheMedChem 2014, 9, 2516–2527. 10.1002/cmdc.201402252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itteboina R.; Ballu S.; Sivan S. K.; Manga V. Molecular docking, 3D QSAR and dynamics simulation studies of imidazo-pyrrolopyridines as janus kinase 1 (JAK 1) inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 64, 33–46. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balupuri A.; Balasubramanian P. K.; Cho S. J. 3D-QSAR, docking, molecular dynamics simulation and free energy calculation studies of some pyrimidine derivatives as novel JAK3 inhibitors. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja H.; Chadha N.; Singh P. K.; Kaur M.; Bahia M. S.; Silakari O. Putative dual inhibitors of Janus kinase 1 and 3 (JAK1/3): Pharmacophore based hierarchical virtual screening. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018, 76, 109–117. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstovsek S.; Mesa R. A.; Gotlib J.; Levy R. S.; Gupta V.; DiPersio J. F.; Catalano J. V.; Deininger M.; Miller C.; Silver R. T.; Talpaz M.; Winton E. F.; Harvey J. H.; Arcasoy M. O.; Hexner E.; Lyons R. M.; Paquette R.; Raza A.; Vaddi K.; Erickson-Viitanen S.; Koumenis I. L.; Sun W.; Sandor V.; Kantarjian H. M. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Ruxolitinib for Myelofibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 799–807. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales A. J.; Bowman J. W.; Fici G. J.; Zhang M.; Mann D. W.; Mitton-Fry M. Oclacitinib (APOQUEL (R)) is a novel Janus kinase inhibitor with activity against cytokines involved in allergy. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 37, 317–324. 10.1111/jvp.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keystone E. C.; Taylor P. C.; Drescher E.; Schlichting D. E.; Beattie S. D.; Berclaz P. Y.; Lee C. H.; Fidelus-Gort R. K.; Luchi M. E.; Rooney T. P.; Macias W. L.; Genovese M. C. Safety and efficacy of baricitinib at 24 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 333–340. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R. Jr. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in the treatment of inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 111, 784–803. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. C. The power issue: determination of K-B or K-i from IC50 - A closer look at the Cheng-Prusoff equation, the Schild plot and related power equations. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2001, 46, 61–71. 10.1016/S1056-8719(02)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu C. L.; Yan G. Y.; Shi J. Y.; Li R. Assessing the performance of docking scoring function, FEP, MM-GBSA, and QM/MM-GBSA approaches on a series of PLK1 inhibitors. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1452–1458. 10.1039/C7MD00184C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A.; Linssen A. B. M.; Berendsen H. J. C. Essential Dynamics of Proteins. Proteins 1993, 17, 412–425. 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalapbutr P.; Wonganan P.; Chavasiri W.; Rungrotmongkol T. Butoxy Mansonone G Inhibits STAT3 and Akt Signaling Pathways in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers: Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. Cancers 2019, 11, 437 10.3390/cancers11040437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.; Bertoni M.; Bienert S.; Studer G.; Tauriello G.; Gumienny R.; Heer F. T.; de Beer T. A. P.; Rempfer C.; Bordoli L.; Lepore R.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; Macarthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. Procheck - a Program to Check the Stereochemical Quality of Protein Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26, 283–291. 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M. H. M.; Sondergaard C. R.; Rostkowski M.; Jensen J. H. PROPKA3: Consistent Treatment of Internal and Surface Residues in Empirical pK(a) Predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 525–537. 10.1021/ct100578z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz A. W.; Williamson M. J.; Xu D.; Poole D.; Le Grand S.; Walker R. C. Routine Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 1. Generalized Born. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 1542–1555. 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decha P.; Rungrotmongkol T.; Intharathep P.; Malaisree M.; Aruksakunwong O.; Laohpongspaisan C.; Parasuk V.; Sompornpisut P.; Pianwanit S.; Kokpol S.; Hannongbua S. Source of high pathogenicity of an avian influenza virus H5N1: Why H5 is better cleaved by furin. Biophys. J 2008, 95, 128–134. 10.1529/biophysj.107.127456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanich J.; Rungrotmongkol T.; Sindhikara D.; Phongphanphanee S.; Yoshida N.; Hirata F.; Kungwan N.; Hannongbua S. A 3D-RISM/RISM study of the oseltamivir binding efficiency with the wild-type and resistance-associated mutant forms of the viral influenza B neuraminidase. Protein Sci. 2016, 25, 147–158. 10.1002/pro.2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongkaew S.; Yotmanee P.; Rungrotmongkol T.; Kaiyawet N.; Meeprasert A.; Kaburaki T.; Noguchi H.; Takeuchi F.; Kungwan N.; Hannongbua S. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Reveals the Selective Binding of Human Leukocyte Antigen Alleles Associated with BehCet’s Disease. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135575 10.1371/journal.pone.0135575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier J. A.; Martinez C.; Kasavajhala K.; Wickstrom L.; Hauser K. E.; Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. M.; Wolf R. M.; Caldwell J. W.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalapbutr P.; Wonganan P.; Charoenwongpaiboon T.; Prousoontorn M.; Chavasiri W.; Rungrotmongkol T. Enhanced Solubility and Anticancer Potential of Mansonone G By beta-Cyclodextrin-Based Host-Guest Complexation: A Computational and Experimental Study. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 545. 10.3390/biom9100545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalapbutr P.; Thitinanthavet K.; Kedkham T.; Nguyen H.; Theu L. T. H.; Dokmaisrijan S.; Huynh L.; Kungwan N.; Rungrotmongkol T. A theoretical study on the molecular encapsulation of luteolin and pinocembrin with various derivatized beta-cyclodextrins. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1180, 480–490. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalapbutr P.; Darai N.; Panman W.; Opasmahakul A.; Kungwan N.; Hannongbua S.; Rungrotmongkol T. Atomistic mechanisms underlying the activation of the G protein-coupled sweet receptor heterodimer by sugar alcohol recognition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10205 10.1038/s41598-019-46668-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; A Petersson G.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Fox D.. et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Kammarabutr J.; Mahalapbutr P.; Nutho B.; Kungwan N.; Rungrotmongkol T. Low susceptibility of asunaprevir towards R155K and D168A point mutations in HCV NS3/4A protease: A molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Graph. Modell. 2019, 89, 122–130. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York D. M.; Darden T. A.; Pedersen L. G. The Effect of Long-Range Electrostatic Interactions in Simulations of Macromolecular Crystals - a Comparison of the Ewald and Truncated List Methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 8345–8348. 10.1063/1.465608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hünenberger P. H. Thermostat algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2005, 173, 105–149. 10.1007/b99427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B.; Bekker H.; Berendsen H. J. C.; Fraaije J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D. R.; Cheatham T. E. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for Processing and Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Trajectory Data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 3084–3095. 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S.; Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2015, 10, 449–461. 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dral P. O.; Wu X.; Sporkel L.; Koslowski A.; Thiel W. Semiempirical Quantum-Chemical Orthogonalization-Corrected Methods: Benchmarks for Ground-State Properties. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 1097–1120. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b01047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naïm M.; Bhat S.; Rankin K. N.; Dennis S.; Chowdhury S. F.; Siddiqi I.; Drabik P.; Sulea T.; Bayly C. I.; Jakalian A.; Purisima E. O. Solvated interaction energy (SIE) for scoring protein-ligand binding affinities. 1. Exploring the parameter space. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 122–133. 10.1021/ci600406v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.