Abstract

Background:

Evidence regarding the efficacy of psychotherapy in adolescents with borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptomatology has not been previously synthesized.

Objective:

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in order to assess the efficacy of psychotherapies in adolescents with BPD symptomatology.

Methods:

Seven electronic databases were systematically searched using the search terms BPD, adolescent, and psychotherapy from database inception to July 2019. Titles/abstracts and full-texts were screened by one reviewer; discrepancies were resolved via consensus. We extracted data on BPD symptomatology, including BPD symptoms, suicide attempts, nonsuicidal self-injury, general psychopathology, functional recovery, and treatment retention. Data were pooled using random-effects models.

Results:

Of 536 papers, seven trials (643 participants) were eligible. Psychotherapy led to significant short-term improvements in BPD symptomatology posttreatment (g = −0.89 [−1.75, −0.02]) but not in follow-up (g = 0.06 [−0.26, 0.39]). There was no significant difference in treatment retention between the experimental and control groups overall (odds ratio [OR] 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92 to 1.12, I 2 = 52%). Psychotherapy reduced the frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury (OR = 0.34, 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.74) but not suicide attempts (OR = 1.03, 95% CI, 0.46 to 2.30).

Conclusions:

There is a growing variety of psychotherapeutic interventions for adolescents with BPD symptomatology that appears feasible and effective in the short term, but efficacy is not retained in follow-up—particularly for frequency of suicide attempts.

Keywords: child and adolescent psychiatry, personality disorder, psychotherapy

Abstract

Contexte :

Les données probantes sur l’efficacité de la psychothérapie chez les adolescents présentant la symptomatologie du trouble de la personnalité limite (TPL) n’ont pas été précédemment synthétisées.

Objectif :

Mener une revue systématique et une méta-analyse des essais cliniques randomisés (ECR) afin d’évaluer l’efficacité des psychothérapies chez les adolescents présentant une symptomatologie du TPL.

Méthodes :

Une recherche systématique a été menée dans 7 bases de données électroniques à l’aide des termes de recherche TPL, adolescent et psychothérapie depuis la date de création de la base de données jusqu’en juillet 2019. Les titres/résumés et les textes complets ont été examinés par un réviseur; les disparités ont été résolues par consensus. Nous avons extrait des données sur la symptomatologie du TPL, notamment les symptômes du TPL, les tentatives de suicide, l’automutilation non suicidaire, la psychopathologie générale, le rétablissement fonctionnel, et la rétention en traitement. Les données ont été regroupées à l’aide des modèles à effets aléatoires.

Résultats :

Sur 536 articles, 7 essais (643 participants) étaient admissibles. La psychothérapie entraînait des améliorations significatives à court terme de la symptomatologie du TPL post-traitement (g = −0.89 [−1.75, −0.02]), mais pas au suivi (g = 0.06 [−0.26, 0.39]). Il n’y avait pas de différence significative de rétention en traitement entre le groupe expérimental et le groupe témoin en général (Rapports de cotes [RC] 1.02; IC à 95% 0.92 à 1.12; I 2 = 52%). La psychothérapie réduisait la fréquence de l’automutilation non suicidaire (RC = 0.34; IC à 95% 0.16 à 0.74), mais pas celle des tentatives de suicide (RC = 1.03; IC à 95% 0.46 à 2.30).

Conclusions :

Il existe une variété croissante d’interventions psychothérapeutiques pour les adolescents présentant une symptomatologie du TPL qui semblent faisables et efficaces à court terme, mais l’efficacité ne persiste pas au suivi, en particulier en ce qui concerne la fréquence des tentatives de suicide.

Introduction

There is a growing recognition that borderline personality disorder (BPD) has its onset in adolescence and that it reaches increasing stability in early adulthood.1–3 In the community, the diagnosis of BPD in adolescents is estimated to be 3%1,4 and increases to 22% in outpatient clinics.5 Historically, diagnosing BPD in adolescents has been a topic of controversy; often the fear of stigmatizing young patients may prevent clinicians from considering BPD as a clinically appropriate diagnosis.3,5 However, a body of evidence indicates that BPD is reliably diagnosed in adolescence and its reliability and validity is comparable with adults.6

BPD is a debilitating mental disorder characterized by a pervasive pattern of instability in affect, identity, interpersonal relationships, and behavioral dysregulation. Alongside a vast array of comorbidities, parasuicidal behaviors and suicide are commonly associated problems.7 BPD is the most common personality disorder in clinical populations, associated with intensive use of mental health services. Adolescents who engage in self-harm are a challenging population to manage because of safety concerns as well as noncompliance.8

Compared with other personality disorders, functional impairment in this population is considerable and is enduring even after patients no longer meet symptom criteria for BPD. At 20-year follow-up, borderline symptoms in adolescents predict decreased life satisfaction, decreased relationship quality, poor social support, low academic and occupational attainment, and higher consumption of health services.9 Despite the absence of a full-fledged disorder, there is enough distress and dysfunction so that patients can benefit from appropriate intervention.6

Earlier diagnosis may lead to timely psychoeducation and intervention, allowing adolescents with emerging BPD to potentially develop skills necessary for improved long-term functioning.2,8 BPD places a large clinical burden on the health-care system raising the importance of early intervention programs which could alter the trajectory toward more adaptive developmental pathways.10 Although the efficacy of psychotherapy in adults with BPD is well established, it is unclear whether psychotherapy is effective for adolescents with BPD symptomatology. Several manualized psychotherapies have been specifically developed for adolescents with BPD. These include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), emotion regulation training (ERT), mentalization-based therapy (MBT), and a combination of psychodynamic and cognitive behavioral therapy such as cognitive analytic therapy (CAT).11–13 Although the therapeutic framework differs among these modalities, common treatment components include individual and family psychoeducation, skills training, and family therapy.

A previous literature review2 of treatment for youth with BPD illustrated that evidence assessing psychotherapeutic treatments was lacking. The review found only one randomized controlled trial with reported benefits from MBT compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in terms of BPD symptoms, self-harm, and depressive symptoms. An updated synthesis and compilation of evidence will assist in informing current treatment decisions in this vulnerable population. To our knowledge, this is the first published systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating psychotherapeutic interventions for adolescents with BPD symptomatology.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to assess the efficacy of psychotherapies in adolescents for BPD-related outcomes at posttest and where possible, at follow-up.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses.14

Eligibility Criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which a psychotherapeutic modality was compared with a control condition for adolescents with BPD symptomatology were considered eligible. We captured adolescents with BPD symptomatology, both adolescents with borderline personality traits and adolescents who met criteria for BPD. In this study, all participants had a minimum of two symptoms of BPD (according to a validated diagnostic instrument, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]).

Studies were excluded if adolescents were not the primary patient population. English language restrictions were applied.

As the focus of this review was on the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for adolescents with BPD, psychotherapy was defined broadly as any psychological intervention that emphasized verbal communication, structured and purposeful therapist–patient encounters, and the establishment of a therapeutic relationship. The most commonly observed psychotherapeutic modalities for BPD in adolescents include DBT, MBT, and cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT). No constraints were placed on the nature of the control group, which could include TAU, waitlist, or alternative psychotherapeutic modalities (such as supportive).

We considered the following outcome measures on the basis of adult studies of effectiveness of psychotherapy for BPD:

Severity of symptoms (including BPD-specific measures, such as parasuicide, suicidal behavior; general psychopathology, including internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, anxiety, depression, substance use) as determined by scores on validated BPD symptom scales, clinician judgment, or self-report;

Frequency of parasuicidal or suicidal behaviors;

Functional recovery, as determined by scores on validated global function scales, clinician judgment, or self-report;

Number of participants who completed the scheduled psychotherapy treatment (otherwise known as “treatment retention”);

Number of participants who engaged in subsequent follow-up or referrals for BPD treatment (otherwise known as “engagement in follow-up”);

Number of participants who experienced serious adverse events, such as death by suicide; and

Number of participants who required additional mental health service use for BPD symptoms, such as emergency room visits, outpatient follow-up, medication use, general psychopathology, anxiety, or depression.

Search Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed in November 2017, with a repeat and expanded search conducted in July 2019. We searched seven electronic databases for relevant articles: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Allied and Complementary Medicine, and Web of Science. We applied a comprehensive search strategy that consisted of combinations of the terms “borderline personality disorder” “adolescents,” and “psychotherapy” (the full search strategy is presented in Supplemental Appendix 1). In addition, we conducted backward searches of reference lists of included articles for further potentially eligible studies as well as reference lists from previous reviews or meta-analyses. However, we did not identify any additional articles through either of these routes.

Study Selection

One author (JW) independently assessed the titles, abstracts, and full-texts retrieved from the systematic search according to the identified inclusion and exclusion criteria. All full-texts retrieved were screened in duplicate (AB). All authors agreed on decisions about the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All disagreements were resolved through consensus.

Data Extraction and Management

One author (AB) independently extracted key information from the included studies using a data collection form to record information against the outcome measures. Data were confirmed by consultation with the other review authors. Key findings of studies were summarized descriptively in the first instance, and the capacity for quantitative meta-analysis was considered.

The following data were collected from each study: study characteristics (sample size, study design, country of study), participant characteristics (gender and age breakdown, instrument used to make BPD diagnosis), experimental and control group characteristics (type of intervention, duration, and mode of delivery of psychotherapy [manualized, background of therapist, supervision]), and outcomes (types of instruments used to measure effectiveness of therapy). In addition, sufficient data were collected to enable an assessment of the risk of bias of included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, which is a validated instrument for accessing the quality of randomized controlled trials.15 This tool rates seven domains of potential bias in a RCT: randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of evaluators, attrition/dropout, selective outcome report, and other potential sources of bias (such as funding). The risk of bias assessment was performed by two independent assessors (JW and SKK). Interrater agreement κ statistics were computed, and disagreement was resolved by discussion among assessors and with another author (AB); consensus ratings are presented here.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (such as completion of treatment or adverse event frequency), we calculated risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous outcomes (such as scores on various rating scales or the number of times participants used a particular health service), we calculated standardized mean differences (SMD) to account for variability in the outcome measure. The between-group effect size was calculated as the difference between the intervention and control groups at posttest, follow-up, and overall (Hedges g), corrected for small sample sizes. Data across multiple follow-up points were averaged at the study level for each outcome category.

Unit of Analysis Issues

Although none of the included studies involved more than two treatment arms (e.g., two psychotherapies compared to placebo), had this occurred, we would have compared each “active” psychotherapy to the placebo in separate subgroups in order to avoid double-counting of participants. If a trial reported data on multiple outcomes in the same category, the mean effect size was calculated using previously described procedures16 so that each trial reported just one overall effect size in a category at each time point.

Dealing with Missing Data

We intended to contact the original investigators to request any relevant missing data; however, this was not undertaken as there was sufficiently well-reported data in the primary studies and in their respective appendices/supplementary materials.

Assessment of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed grossly by reviewing variations across studies in terms of participant, intervention, and outcome characteristics. More formal assessments of heterogeneity were conducted quantitatively (using the I 2 statistic, with a value of 50% or higher indicating statistically significant heterogeneity) and qualitatively (by visual inspection of the forest plots).17 As there was evidence of significant heterogeneity, a random-effects model analysis model was conducted. We then conducted a sensitivity analyses to weigh the relative influence of each individual study on the pooled effect size.

Subgroup Analysis and Investigation of Heterogeneity

This review intended to consider several potential contributions to heterogeneity via subgroup analysis, including gender, age, severity of BPD symptoms, modality of psychotherapy, and duration of intervention. A subgroup analysis was conducted for BPD symptom measures posttest (immediately following study end), in follow-up (weeks to months after the final intervention was provided), and overall; however, additional subgroup analyses were not undertaken due to insufficient respective sample sizes.

Assessment of Reporting Bias

We examined publication bias qualitatively by examining funnel plots for symmetry.18

Results

Results of the Search

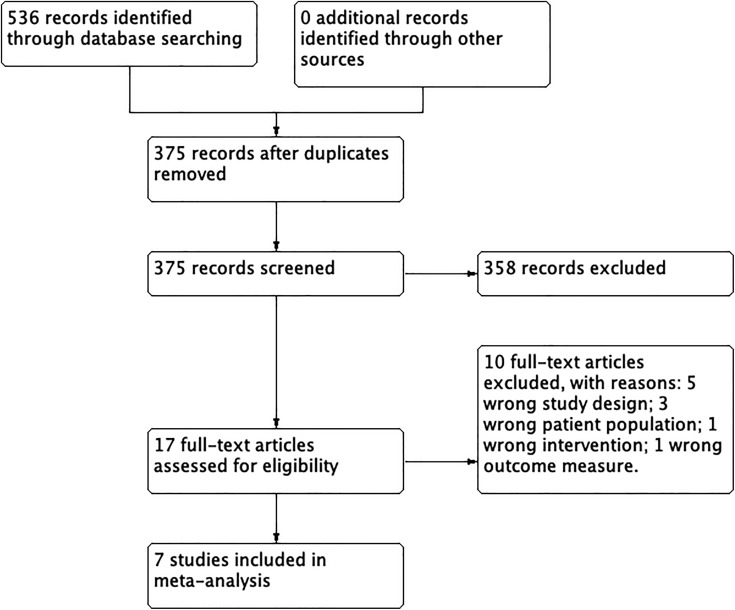

Our search strategy identified a total of 536 citations. After duplicates were removed, 375 unique citations remained, which were subsequently screened by title and abstract. Of these, 358 irrelevant records were removed. Of the 17 remaining articles, 10 were excluded at the full-text stage: 5 involved nontrial designs, 3 involved nonadolescent populations, 1 did not involve psychotherapy, and 1 did not report efficacy-relevant outcomes. Ultimately, seven randomized controlled trials met final inclusion criteria for the qualitative and quantitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses flow diagram of systematic review process.

Description of Studies

The seven trials included in the meta-analysis represented a total of 643 adolescents with BPD. All participants had a minimum of two symptoms of DSM-IV BPD (and in one study,19 the minimum was three symptoms of BPD according to the DSM-5). The average number of BPD criterion met by this patient population varied across each study (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Select Characteristics from Trials Reporting Psychotherapy for Adolescents with Borderline Personality Traits.

| Study | Study Arms and Number of Participants | Age, Years | Eligibility Criteria | Number of BPD Criteria Fulfilled by Total Sample, Mean (Range) | Total Sample With BPD Diagnosis at Baseline, n (%) | Primary Outcome Measures | Treatment Duration | Total Study Duration, Months | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chanen24

Australia |

CAT—41 GCC—37 |

15 to 18 | Outpatients with at least two criteria of DSM-IV BPD and specified risk factors of BPD | 4.4 (2 to 8) | 32 (41) | SCID-II YSR Parasuicidal behavior SOFAS |

24 weekly sessions | 24 | No difference between groups at follow-up, both improved. CAT improved more rapidly |

| McCauley19

USA |

DBT—72 IGST—65 |

12 to 18 | Community, inpatient, and outpatients with a prior lifetime suicide attempt and three or more DSM-V BPD criteria | NS | 92 (53) | SASII SIQ-JR |

6 months | 12 | DBT was superior to IGST for reducing suicide attempts, nonsuicidal self-injury, and self-harm at 6 months. No advantage seen at 12 months. DBT had higher completion rate |

| Mehlum20

Norway |

DBT-A—39 EUC—38 |

12 to 18 | Outpatients with at least two episodes of self-harm, one within the last 16 weeks. At least two criteria of DSM-IV BPD | 4 (2)a | 15 (21) | SCID-II Parasuicidal behavior SIQ-JR SMFQ MADRS BHS BSL Hospital/ER visits |

19 weekly sessions | 4 | DBT-A was superior to EUC in reducing self-harm, suicidal ideation, and depressive symptoms. No difference between groups for borderline symptoms. Both groups had good treatment retention and use of ER services was low |

| Mehlum25

Norway |

DBT-A—39 EUC—38 |

12 to 18 | Outpatients with at least two episodes of self-harm, one within the last 16 weeks. At least two criteria of DSM-IV BPD or one plus two subthreshold-level criteria | 4 (2)a | 15 (21) | SCID-II Parasuicidal behavior SIQ-JR SMFQ MADRS BHS BSL Hospital/ER visits |

19 weekly sessions | 12 | DBT-A was superior in reducing self-harm frequency over a 52-week follow-up period. No other differences in other outcomes were significant at the 52-week period (DBT-A group remained constant; EUC group improved) |

| Roussouw21

UK |

MBT-A—40 TAU—40 |

12 to 17 | At least one episode of self-harm within the past month and two DSM-IV BPD symptom criteria | NS 73% fulfilled ≥ five criteria |

NS | RTSHI DSH CI-BPD MFQ BPFS-C HIF ECR |

12 months | 12 | MBT-A was superior to TAU in reducing self-reported self-harm, depression, and borderline symptoms. At 12 months, 58% of TAU group met CI-BPD criteria, but only 33% of MBT-A group met criteria (P < 0.05). No difference in risk-taking |

| Schuppert22

Netherlands |

ERT + TAU—23 TAU—20 |

14 to 19 | At least mood instability criterion of DSM-IV BPD and one more criterion | NS | NS | BPDSI MERLC YSR |

17 weekly sessions + two booster sessions | 4 | Both groups improved equally on BPD symptoms. ERT + TAU had improved internal locus of control and greater control over mood swings. High attrition rate (28% lacked posttreatment data) |

| Schuppert23

Netherlands |

ERT + TAU—54 TAU—55 |

14 to 19 | At least two criteria of DSM-IV BPD | 6.17 (3 to 9) 73% fulfilled ≥ five criteria |

NS | SCID-II BPDSI SADS-PL LPI-ed MERLC CDI SNAP |

17 weekly sessions + two booster sessions | 6 (ERT+ TAU only) | Both groups improved equally on the severity of BPD symptoms, psychopathology, and quality of life posttest. At posttest, 19% of ERT + TAU group had remission based on BPDSI score vs. 12% of TAU group. At 6-month follow-up, 33% of ERT + TAU group had remittance |

Note. CAT = cognitive analytic therapy; DBT-A = dialectical behavioral therapy for adolescents; MBT-A = mentalization-based treatment for adolescents; IGST = individual and group supportive therapy; ERT = emotion regulation training; SCI = structured clinical interview; DSH = documented self-harm; GCC = good clinical care; EUC = enhanced usual care; TAU = treatment as usual; NS = not specified; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Abbreviations for Primary Outcomes: BPD symptomatology—SCID-II = structured clinical interview for DSM–IV axis II disorders; BSL = borderline symptom list; CI-BPD = childhood interview for DSM-IV borderline personality disorder; BPFS-C = Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children; BPDSI = Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index-IV. Internalizing and externalizing—YSR = Youth Self-Report Questionnaire. Global functioning—SOFAS = Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. Parasuicidal behavior—SIQ-JR = Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire; SASII = suicide attempt self-injury interview; RTSHI = Risk-Taking and Self-Harm Inventory. Depression—SMFQ = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; MADRS = Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory. Hopelessness—BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale. Mentalization—HIF = How I Feel Questionnaire. Attachment—ECR = experience of close relationships. Trauma—SADS-PL = schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia present and lifetime version modules on traumatic experiences. Emotional dysregulation—LPI-ed = Life Problems Inventory subscale Emotional Dysregulation. ADHD—SNAP = Swanson, Nolan and Pelham Teacher and Parent Rating Scale.

aMehlum (2014) and (2016) reported the BPD criteria fulfilled as median (interquartile range).

Of these, 324 participants were in the investigated treatment group and 319 were in the control group. Three trials targeted patients with BPD diagnosed using a structured clinical interview, while the remaining four trials targeted patients with BPD symptoms with recent documented self-harm. Four trials had a stand-alone design (where the experimental and control groups received entirely different treatments), and the remaining three trials had an add-on design (where the experimental group received the control group intervention in addition to further psychotherapy). The percentage of females ranged from 85% to 96%, with ages ranging from 12 to 18 years. The best represented approaches were DBT (three trials) and ERT (two trials); the remaining two trials used MBT and CAT, respectively. Three trials had TAU as the control treatment, two trials used enhanced usual care, one trial used good clinical care, and one trial used individual and group supportive therapy; the control treatment was manualized in three trials. The treatment developer was an author in three trials. In six trials, one of the authors supervised therapists directly. Treatment duration ranged from 5 to 24 months, and the number of sessions (for individual and group therapy taken together) ranged from 12 to 28. Regarding BPD symptomatology measures, four trials20–23 provided posttreatment efficacy measures, two trials24,25 provided follow-up efficacy measures, and one trial19 did not provide data on BPD symptom measures using score-based rating tools.

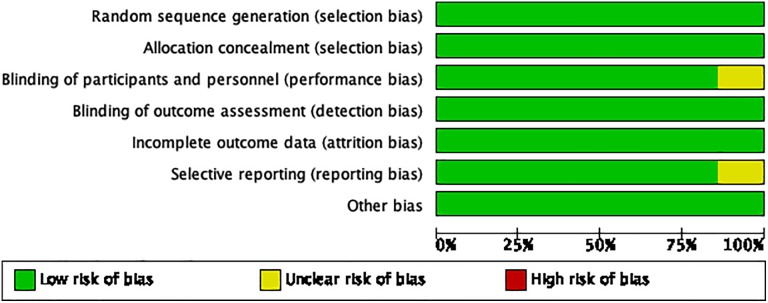

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Overall, the risk of bias in included studies was generally low, and the studies were rated as being of very high quality. All seven trials reported adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment (two used self-report measures only), and were rated as having a low risk of bias for selective reporting and incomplete outcome data. There were no disagreements between the two raters regarding the quality of the studies. For summary, consensus results of the judged risk of bias across the included studies for each domain from the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, please refer to Figures 2 and 3. There was limited evidence of publication bias in our results given the observed symmetry of the funnel plot of standard error (Supplemental Appendix 4).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: Authors’ judgments about each risk of bias represented as percentage across all included studies.

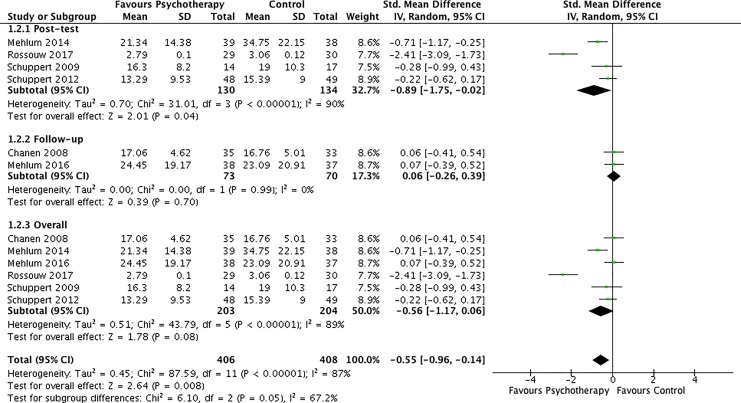

Figure 3.

Forest plot of borderline personality disorder symptom outcomes. Shown are standardized posttest follow-up and overall effect sizes of comparisons between investigated psychotherapies and control conditions for BPD symptoms for included trials.

Effects of Interventions

Meta-analysis was conducted for six outcomes: (1) BPD symptom improvement—at treatment completion and in follow-up, (2) treatment retention (defined as the number of participants completing the primary study end point), (3) externalizing symptoms, (4) internalizing symptoms, (5) functional recovery, (6) frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury, and (7) frequency of suicide attempts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Outcomes from Meta-Analysis.

| Outcome | Number of Trials | Participants | Statistical Method | Effect Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD symptoms posttest | 4 | 264 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | −0.89 [−1.75, −0.02] |

| BPD symptoms follow-up | 2 | 143 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [−0.26, 0.39] |

| BPD symptoms overall | 6 | 407 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | −0.56 [−1.17, 0.06] |

| Externalizing symptoms | 2 | 94 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | −0.28 [−0.69, 0.13] |

| Internalizing symptoms | 3 | 189 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [−0.26, 0.31] |

| Functioning | 4 | 315 | Std. mean difference (random, 95% CI) | −0.04 [−0.26, 0.18] |

| Treatment retention | 7 | 643 | Odds ratio (random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.61, 1.10] |

| Nonsuicidal self-injuries | 7 | 558 | Odds ratio (random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.16, 0.74] |

| Suicide attempts | 4 | 355 | Odds ratio (random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.46, 2.30] |

Note. BPD = borderline personality disorder; CI = confidence interval; std = standard.

Severity of Symptoms

The symptoms that were meta-analyzed included BPD-specific measures (such as parasuicide, suicidal behavior) and general psychopathology (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms) that were measured by validated instrument. When stand-alone and add-on designs were pooled, psychotherapy had a significant and large effect on reducing overall BPD symptoms following completion of the scheduled psychotherapy (g = −0.89 [−1.75, −0.02], I 2 = 90%, four studies, Figure 3). However, this effect diminished in follow-up and was found to no longer remain statistically significant (g = 0.06 [−0.26, 0.39], I 2 = 0%, two studies, Figure 3). When the total, overall symptom scores were pooled, there was no statistically significant improvement in BPD symptom measures between the experimental and control groups across studies (g = −0.56 [−1.17, 0.06], I 2 = 89%, six studies, Figure 3). The heterogeneity for the postintervention and overall meta-analyses of BPD symptoms was quite high (I 2 values of 90% and 89%, respectively), justifying the use of random-effects meta-analysis and SMD. The finding that there was no overall reduction in symptom severity was found to be robust as there was no change in the statistical significance when a sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing one each of the six studies individually.

Three studies22–24 reported the efficacy of psychotherapy for internalizing and externalizing psychopathology scores as derived from the Youth Self-Report26 Questionnaire, a widely used instrument that assesses behavioral and emotional functioning in young people aged 11 to 18 years. Similarly, psychotherapy did not have a statistically significant effect on the overall severity of externalizing symptoms (g = −0.28 [−0.69, 0.13], Supplemental Appendix 3) or internalizing symptoms (g = 0.02 [−0.26, 0.31], Supplemental Appendix 3).

Functional Recovery

Functional recovery was determined by improvements in scores on validated global function scales before and after psychotherapeutic treatment, such as the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale.27 In the four studies20,23–25 that reported such measures, there was no significant difference in functional outcomes overall (g = −0.04 [−0.26, 0.18], I 2 = 0%, four studies, Supplemental Appendix 3).

Treatment Retention

Treatment retention was defined as the number of participants completing the primary study end point. There was no significant difference in treatment retention between the experimental and control groups overall (odds ratio [OR] = 1.02, 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.12, I 2 = 52%, seven studies, Supplemental Appendix 3).

Suicide Attempts and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Four studies19,20,24,25 reported the frequency of suicide attempts at the completion of treatment (relative to baseline), while all seven studies reported the frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury at treatment completion. Compared to the control group, participants receiving psychotherapy had significantly less frequent nonsuicidal self-injury (OR = 0.34, 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.74, I 2 = 76%, seven studies, Supplemental Appendix 3). However, there was no difference in the frequency of suicide attempts (OR = 1.03, 95% CI, 0.46 to 2.30, I 2 = 56%, four studies, Supplemental Appendix 3) between experimental and control arms.

Discussion

Summary of Results

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of psychotherapies for BPD in adolescents. We included seven trials of either stand-alone (an independent experimental treatment vs. TAU or another control) or add-on designs (an experimental treatment superimposed to TAU vs. TAU alone). We examined treatment effect on BPD symptoms, suicide attempts, nonsuicidal self-injury, and several related outcomes such as internalizing and externalizing symptoms and global functioning. For some outcome categories, trials are lacking, and thus, findings should be viewed as tentative and inconclusive. The most significant results are that psychotherapy had a significant and large effect on BPD symptoms (g = −0.89 [−1.75, −0.02], I 2 = 90%) and nonsuicidal self-injury (OR = 0.34, 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.74), but these were not maintained in follow-up (g = 0.06 [−0.26, 0.39], I 2 = 0%) or overall (g = −0.56 [−1.17, 0.06], I 2 = 89%). Similarly, psychotherapy did not have a statistically significant effect on externalizing symptoms (g = −0.28 [−0.69, 0.13]), internalizing symptoms (g = 0.02 [−0.26, 0.31]), or functioning (g = −0.04 [−0.26, 0.18]).

Significance of Findings

Overall, our findings suggest that psychotherapies for adolescents with subsyndrome BPD are effective for not only BPD-specific symptomatology but also externalizing and internalizing symptoms—particularly in the short term—and also reduce the frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury. However, treatments were not effective at reducing the frequency of suicide attempts. As well, the efficacy of these treatments was not statistically significant in long-term follow-up—an effect that mirrors findings from the adult BPD literature.12 As commonly recognized in adults with BPD, there is often no difference at follow-up although both treatment arms improve posttreatment. One potential explanation cited in the adult literature is that these highly structured comparator treatments may be just as effective because they contain components thought to be important in psychotherapy, specifically their consistency and continuity as well as the therapeutic relationship.11,12 For example, McMain and colleagues examined the clinical efficacy of adults with BPD who received 1 year of DBT versus general psychiatric management in a single-blind trial and found that both groups had reductions in BPD symptoms, self-reported suicidal behavior, ED visits, and interpersonal functioning.13

Furthermore, our studies were associated with substantial heterogeneity in the number of BPD symptoms reported (ranging from 2 to 9 of the DSM criteria), the age and sex distribution of the participants, whether they were taking concurrent medications, the presence or absence of psychiatric and medical comorbidity, previous treatments, and severity of specific BPD symptoms (e.g., number of previous suicide attempts). Despite this heterogeneity, the results showed that psychotherapeutic intervention does reduce symptoms of BPD significantly in short-term follow-up. This is an important point that would likely be valuable to patients and their families. While the effects of psychotherapy are attenuated in follow-up, research should focus on understanding the reasons for this phenomenon alongside efforts to lengthen sustained benefits such as booster sessions or longer treatment strategies should be undertaken. In clinical practice, it would be important for clinicians to provide patients and their families with realistic treatment expectations given that the effects of psychotherapy are not sustained in follow-up. It is not clear why psychotherapeutic interventions had no effect on suicide attempts. We cannot rule out the possibility that trials with larger sample sizes, longer duration, and greater power might find a statistically significant difference in suicidal behavior in follow-up.

It is important to note that BPD exists on a continuum of clinical severity. Our findings are likely generalizable to adolescents with “milder” BPD symptoms given that many of these trials only required two criteria of the DSM-IV diagnosis for inclusion. There was one trial where three DSM-IV criteria were necessary for inclusion. The liberal inclusion criteria, few exclusion criteria, and community hospital setting for these studies add to the strengths of their external validity. These studies provide further support that various psychotherapeutic interventions can be successfully delivered to this population and that this patient population can adhere to treatment. Although promising, none of our studies assessed whether the proportion of patients who fulfilled BPD criteria changed or remained stable following psychotherapy.

Study Quality and Heterogeneity

Although the results posttest are encouraging, the clinical interpretation is difficult because of large heterogeneity. There was significant diversity of clinical interventions as well as methodological differences. In addition, most included studies had small sample sizes with relatively brief durations of follow-up.

Limitations

When considering the results of our meta-analysis, there are a few limitations to consider. Due to the low yield of studies, a more extensive subgroup and meta-regression analysis was not possible—which would have helped account for the heterogeneity observed across studies. For example, we were unable to determine whether there were differences between study design (stand-alone vs. add-on) or types of psychotherapy (DBT vs. CBT).

Our study sample was predominantly female, and this may limit the generalizability of our findings to adolescent males with BPD symptoms. As well, other outcome measures such as health service use and general psychopathology were not measured consistently across studies, precluding meta-analysis for all outcomes. Some outcome categories or subgroups included data from a small number of trials, rendering resultant effect sizes potentially uncertain. While our search strategy was broad, we still may have missed trials that addressed personality disorders in general but ultimately had a sample composed of patients with BPD. The inclusion of English-only studies may also have led to selection bias. As well, the use of adjunctive medication was not consistently reported and could have confounded psychotherapy effects.

Finally, the inclusion criteria were chosen to capture all adolescents with BPD symptomatology. Our patient population had a minimum of two symptoms according to the DSM criteria. We do not know whether this group is generalizable to adolescents who meet the full criteria for BPD, and their responses to treatment may differ. Treatment engagement and adherence may be more challenging in adolescents with severe and well-established BPD. There were insufficient data unfortunately to conduct meaningful subgroup of meta-regression on the number of BPD symptoms to determine whether this explained efficacy differences or heterogeneity. It is important to determine whether similar findings emerge with alternative inclusion criteria such as adolescents with BPD, or male patients.

Conclusions

There are a growing variety of psychotherapeutic interventions for adolescents with subsyndromal and BPD that appear feasible and have preliminary evidence of short-term efficacy for BPD symptoms and nonsuicidal self-injury. At present, there are too few studies to draw firm conclusions about the benefits of the psychotherapies evaluated, particularly in the long-term. Future research should focus on understanding the reasons for this phenomenon. Efforts to lengthen sustained benefits such as booster sessions or longer treatment strategies should be undertaken.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, 878975_Appendices for Psychotherapies for Adolescents with Subclinical and Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Jennifer Wong, Anees Bahji and Sarosh Khalid-Khan in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Jennifer Wong and Anees Bahji had full access to all the data in the study and take shared responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Jennifer Wong contributed to study concept, design, drafting the manuscript, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. Sarosh Khalid-Khan contributed to study concept, design, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, and for study supervision. Anees Bahji contributed to drafting the manuscript, for statistical analysis, and to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jennifer Wong, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8353-5937

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8353-5937

Anees Bahji, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3490-314X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3490-314X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L. Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(8):1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biskin RS, Paris J, Renaud J, Raz A, Zelkowitz P. Outcomes in women diagnosed with borderline personality disorder in adolescence. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):168–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newton-Howes G, Clark LA, Chanen A. Personality disorder across the life course. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385(9969):727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zanarini MC, Horwood J, Wolke D, Waylen A, Fitzmaurice G, Grant BF. Prevalence of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder in two community samples: 6,330 English 11-year olds and 34,653 American Adults. J Personal Disord. 2011;25(5):607–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chanen AM, McCutcheon LK. Personality disorder in adolescence: the diagnosis that dare not speak its name. Personal Ment Health. 2008;2(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller AL, Muehlenkamp JJ, Jacobson CM. Fact or fiction: diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(6):969–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-V: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; [accessed 2013 May 22] doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chanen AM, Kaess M. Developmental pathways to borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winograd G, Cohen P, Chen H. Adolescent borderline symptoms in the community: prognosis for functioning over 20 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(9):933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chanen AM. Outcomes in women diagnosed with borderline personality disorder in adolescence. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(3):175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biskin RS, Paris J. Management of borderline personality disorder. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;184(17):1897–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, Palomba D, Barbui C, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, et al. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1365–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Rothstein HR. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehlum L, Tormoen AJ, Ramberg M, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1082–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1304–1313.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schuppert HM, Giesen-Bloo J, van Gemert TG, et al. Effectiveness of an emotion regulation group training for adolescents—a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2009;16(6):467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schuppert HM, Timmerman ME, Bloo J, et al. Emotion regulation training for adolescents with borderline personality disorder traits: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1314–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, et al. Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder using cognitive analytic therapy: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2008;193(6):477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marsh HW, Parada RH, Ayotte V. A multidimensional perspective of relations between self-concept (Self Description Questionnaire II) and adolescent mental health (Youth Self-Report). Psychol Assess. 2004;16(1):27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rybarczyk B. Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. New York (NY): Springer, 2011. p. 2313–2313. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, 878975_Appendices for Psychotherapies for Adolescents with Subclinical and Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Jennifer Wong, Anees Bahji and Sarosh Khalid-Khan in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry