The unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS), also known as the vegetative state (VS), is one of the most dramatic outcomes of acquired brain injury. Despite spontaneous eye opening and independent vital functions, VS/UWS patients cannot functionally communicate their thoughts or feelings and appear completely unaware of their surroundings and themselves.1, 2 VS/UWS has confronted families, clinicians, society, and science with a variety of clinical and ethical quests and dilemmas for >50 years.3, 4

Uncertainty about the natural course of VS/UWS plays a major part in many of these challenges. With a prevalence of 0.2 to 6.1 patients per 100,000 inhabitants,5 it is classified as a rare to ultrarare medical condition.6 Available figures on recovery and survival arise mostly from well‐organized clinical environments in which VS/UWS patients receive specialized postacute care.7, 8, 9 These, however, do not represent standard practice.10, 11 Fins coined the term “disordered care” to describe the dire straits patients with disorders of consciousness and their families in the USA were in in 2013.10 The evidence with regard to the expected outcome in patients in VS/UWS was characterized as “limited” in a 2018 review by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN).12, 13

Data about survival and end‐of‐life scenarios in VS/UWS are of particular importance to the ongoing international debate on decision‐making in prolonged disorders of consciousness (PDOC). The view on discontinuation of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) in these patients varies greatly between countries.4, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17 Although in the United States, discontinuation of ANH has been lawful since the Cruzan ruling in 1990,18 the responsibility for clinical decision‐making lies with the incapacitated patient's surrogates and may involve the court (eg, the case of Terri Schiavo19). The United Kingdom recently moved the responsibility for end‐of‐life decisions in PDOC from the courtroom back to the clinic.20, 21 In France, the summer of 2019 brought a tug of war about the discontinuation of ANH in a patient who had been in VS/UWS for 11 years.22 Those involved in, or confronted by, such paradigm shifts and public discussions, are in need of clear scientific descriptions of how VS/UWS patients fare in real‐life settings.

Since the 1990s, a medical–ethical–legal framework in the Netherlands has allowed for withdrawal of ANH in VS/UWS once chances of recovery of consciousness have become negligible.4, 23, 24 Contrary to the USA, in the Netherlands the responsibility for such decisions lies with the treating physician. Up until 2019, specialized PDOC rehabilitation was only reimbursed for patients younger than 25 years. Next to this threshold for postacute rehabilitation, over the years a highly professional long‐term care practice developed. A specific academic medical specialty for working in nursing homes and in primary care was established. This medical discipline, called "elderly care medicine" (formerly known as nursing home medicine), is dedicated to patient‐centered care for the elderly, but also for young patients with the severest sequelae of neurological diseases.25, 26 Dutch elderly care medicine has a tradition of research whose topics include VS/UWS. Specifically, decision‐making and end‐of‐life scenarios in VS/UWS have been studied retrospectively and in case reports since the 1990s.27, 28, 29, 30, 31

The Netherlands have the lowest VS/UWS prevalence documented worldwide.5, 32 Nonetheless, prolonged and extremely prolonged VS/UWS, even beyond 25 years after the causative injury, occurs as well, often associated with conflicts between relatives and medical staff about life‐prolonging medical treatment.29, 30, 31, 32

A nationwide dynamic cohort study, carried out between 2012 and 2018, allows us to present the outcomes of VS/UWS patients in this particular context. Extensive descriptions of the study methods and results are available as Supplementary Material at https://ukonnetwerk.nl/outcomes_from_a_vicious_circle_supplements.

The study involved hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and patients cared for at home. Level of consciousness was quantified with the Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (CRS‐R),33 at inclusion and during up to 6 years of follow‐up, by the same formally trained and experienced clinician (W.S.v.E.). Patients’ families were invited to actively participate in the assessment. Treating physicians provided their patients’ clinical characteristics. Patients’ trajectories through the health care system and aspects of the care they received were investigated/recorded/registered as well. When an included patient died, the treating physician was asked to fill in a questionnaire on the cause of death, its circumstances, and events and decisions preceding it. All posthumous data were verified with the treating physician by telephone, to prevent misinterpretation regarding treatment scenarios and causes of death, which are difficult to capture in questionnaires.34 Physicians were also invited to share any challenges, positive experiences, or peculiarities they had encountered while caring for the included patient.

As VS/UWS is extremely rare in the Netherlands,32 we allowed for variable time post ictus at inclusion and scheduled follow‐up accordingly. This meant that a patient included at 1 month post ictus would receive 4 measurements within the first year, whereas someone in VS/UWS included at 3 years post ictus would be assessed once per year.

Over the course of 6 years, 59 patients possibly eligible for inclusion were clinically evaluated by the researcher; 28 of them (47%) were found to be in a minimally conscious state (MCS). This resulted in a study population of 31 patients with a diagnosis of VS/UWS. Nineteen patients (61%) were included within 1 year after the incident, and the average time post ictus at inclusion was 3.5 years (standard deviation [SD] = 7 years, range = 1 month–33 years). Seventy‐one percent of included patients had sustained nontraumatic brain injury, most often during an out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (10/31 patients, 32% of the total group).

Of the 28 patients who had already been discharged from hospital at baseline, only 1 (4%) had followed specialized rehabilitation in a clinical rehabilitation center within the Netherlands. Six patients (21%) had received a correct level of consciousness diagnosis (either VS or UWS) at hospital discharge. The others’ conditions were described as “poor neurological recovery,” a Glasgow Coma Scale score, or by stating the etiology (eg, “subarachnoid hemorrhage”). At nursing home admission, a diagnosis of VS/UWS was made in 11 cases (39%). There was no mention of CRS‐R scores accompanying any of the hospital or nursing home diagnoses.

The treating physician was an elderly care physician in 18 of 31 cases (58%), a resident or junior doctor in 10 cases (32%), a neurologist in 3 cases, and a general practitioner in 1 case.

During the total course of the study, 6 patients emerged from VS/UWS (see Supplementary Material for the extensive methodology and results). Three patients were alive in VS/UWS when the study ended. Four patients, all confirmed to be alive when the study ended, were lost to follow‐up because of nonrespondent physicians. Eighteen of 31 patients died during the course of the study. Eleven of them did so within 2 years post ictus; the others died between 4 and 33 years post ictus. Mean age at death was 50 years (SD = 12 years, range = 26–67 years). We will now zoom in on the data we obtained in relation to the end of life in VS/UWS patients.

Scenarios of dying are listed in the Table. Three patients were unexpectedly found deceased, 1 presumably due to an epileptic seizure causing hypoxemia, whereas the causes of death in the other 2 remained unclear, even after autopsy in 1 case. Another patient died due to sudden respiratory failure despite curative treatment. Two died after a decision not to treat a new, life‐threatening complication (eg, pneumonia). Nine of 18 deaths (50%) occurred after withdrawal of ANH.

Table 1.

End‐of‐Life Scenarios in Deceased Vegetative State/Unresponsive Wakefulness Syndrome Patients (n = 18)

| Sex; Age, yr | Etiology | Time Post Ictus |

|---|---|---|

| Cessation of ANH | ||

| M; 45 | TBI | 4 mo |

| M; 57 | OHCA | 5 mo |

| M; 45 | OHCA | 5 mo |

| F; 44 | TBI | 9 mo |

| M; 26 | Non‐TBI miscellaneous | 1 yr |

| F; 55 | Non‐TBI miscellaneous | 7 yr, 4 mo |

| F; 50 | SAH | 7 yr, 4 mo |

| F; 38 | TBI | 20 yr |

| F; 59 | OHCA | 33 yr, 5 mo |

| New life‐threatening complication, no treatment | ||

| F; 65 | Non‐TBI miscellaneous | 1 yr, 1 mo |

| M; 66 | OHCA | 1 yr, 2 mo |

| New life‐threatening complication, died despite treatment | ||

| F; 66 | OHCA | 5 yr, 3 mo |

| Unexpected death of unknown cause | ||

| F; 29 | Non‐TBI miscellaneous | 5 mo |

| F; 52 | Non‐TBI miscellaneous | 1 yr, 9 mo |

| F; 54 | SAH | 9 yr, 6 mo |

| Missing | ||

| F; 35 | OHCA | 4 mo |

| M; 50 | TBI | 8 mo |

| M; 55 | OHCA | 4 yr, 5 mo |

ANH, artificial nutrition and hydration; F, female; M, male; OHCA, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

All physicians in charge of these 9 cases were elderly care physicians, 4 of whom had expressed the intention to withdraw ANH in this case earlier in the study. Based on the questionnaires (n = 9) and telephone verification (n = 7), every decision to withdraw ANH was tied to a specific event or development. This “trigger” was a somatic complication such as an infection in 5 cases. A factor unrelated to the patient's clinical condition led to the decision in the other 4. Two arose from the research itself (eg, repeated confirmation of the diagnosis by an expert not affiliated with the patient's care facility). In the other 2, a dysfunctional feeding tube led to ANH being withdrawn. All physicians considered themselves responsible for this decision; 3 of them felt they shared responsibility with the patient's relatives. According to the physicians, none of the decisions was made without the relatives’ consent.

Detailed information on the patient's last days was obtained in 7 cases. After discontinuation of ANH, all patients were, either proactively or reactively, treated with midazolam and morphine to alleviate signs of possible discomfort. Antiepileptic drugs were abruptly stopped in the 3 patients who had been receiving them; 2 of them developed seizures. The time span between withdrawal of ANH and death varied. Two patients, both with severe complications and comorbidity (ileus, diabetes mellitus type 1), died within 48 hours. Four others survived for >1 week, 1 somatically healthy man in his 40s even for 18 days. In 3 of these cases lasting for >1 week, treating physicians mentioned unprompted that they had felt the “emaciation” (physicians’ quotes) that occurred after ANH was discontinued to have compromised the “patient's dignity” (physicians’ quotes). Two physicians spontaneously reported being asked by family members “to euthanize the patient” (physicians’ quotes). In accordance with the strict euthanasia regulations in place in the Netherlands, these requests were not granted.35

How do these observations relate to what was already known about dying in PDOC? Somatic complications are associated with mortality in VS/UWS, either despite treatment or after a decision to withhold treatment.29, 30, 36 In a retrospective Dutch study on 43 VS/UWS deaths between 2000 and 2003, death after withholding treatment for a new complication was the primary scenario in 56% of cases.30 A decade later, the primary scenario at the end of life in VS/UWS patients in the Netherlands has become death after withdrawal of ANH, in 50% of cases. This is a substantial increase compared to 2000–2003, when this happened in only 21% of deaths.30

Dutch law states that any medical treatment has to be in accordance with medical professional standards and requires the patient's consent or that of their surrogate.37 It is the treating physician's responsibility to ensure that the treatment he or she provides meets both criteria. In unresponsive patients receiving medical treatment in the form of ANH, this reverse burden of proof is complex in 2 ways.

First, the medical professional standard regarding ANH in VS/UWS is not entirely clear. As we mentioned above, in the late 1990s authoritative Dutch reports stated that ANH should not be continued if it at best results in prolonging life in VS/UWS with no chance of recovery.4, 23, 24 The exact moment this chance has passed, however, cannot be determined with certainty. Although the recent AAN guideline states that a patient's prognosis should not be considered poor within the first 28 days postinjury, it does not explicitly mention when recovery does become unlikely.12 It is now generally accepted that patients may recover consciousness well into the second year after their injuries,12, 38 but their functional outcome, let alone quality of life, is unknown. Moreover, there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of VS/UWS. Clinical misdiagnosis occurs in about 40% of cases.32, 39, 40 To complicate matters further, even among adequately assessed VS/UWS patients, in a significant proportion brain activity patterns compatible with higher cognitive function can be detected with advanced diagnostic techniques.41, 42, 43 Such techniques are not yet part of routine clinical care. In other words, in trying to predict the yield of ANH in VS/UWS in a purely medical sense, a physician faces serious diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty.

Second, the process of determining whether an individual patient in clinical VS/UWS would have given consent to receive ANH is challenging. The patients cannot speak for themselves. The family is invariably struck by a combination of hope, grief, and uncertainty, and sometimes feelings of guilt and anger, that parallels the emotions relatives experience in missing person cases.44 This further aggravates the already complex task of speaking on behalf of a loved one. Shared decision‐making takes time and skill, especially in prolonged disorders of consciousness,10, 13, 28, 29, 45, 46 and requires adequate psychosocial guidance of the patient's family. In addition, the family must weigh the same uncertain diagnostic prognostic information the physician has at their disposal.

In our study, the decision to discontinue ANH was made by the physician, never by a junior doctor or resident and, according to the physicians involved, never against the relatives’ wishes. Although the physicians in our cohort considered it their responsibility to discontinue ANH, in all 9 cases the timing of ANH withdrawal was linked to a specific and sometimes seemingly haphazard event such as a new complication or a dysfunctional percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy system. The timeframe in which life‐prolonging treatment in VS/UWS may be stopped, also called “the window of opportunity,” is classically situated in the first year after onset.47, 48 In our study, however, we observed such decisions being made in patients in extremely prolonged VS/UWS as well, even after >33 years. It seems that these heavy deliberations require the momentum of an external trigger, and that that trigger may even appear after decades of status quo.

Dying after discontinuation of ANH has been described as peaceful and calm in previous publications.27, 29, 36, 49, 50 and this is an observation shared by various physicians in our study. Some patients, however, developed seizures after the sudden discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs, and others’ bodies changed unrecognizably due to emaciation. Especially when a prolonged period of time, up to 18 days, went by between the moment of ANH withdrawal and the patient passing away, physicians described a “burden of witness,”50 as experienced by both themselves and the patients’ families. In 3 cases, they even considered this process to have compromised the patient's dignity. Symptomatic treatment, including palliative sedation, is unlikely to relieve this burden.51 In the absence of a patient's own willful and consistent request for active life termination, and of definite unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement, euthanasia is illegal in the Netherlands.35 The question remains whether a family's suffering could ever be reason to discard these requirements, or that that would that lead to a slippery slope.

Our cohort of 31 VS/UWS patients in the Netherlands paints a bleak picture of the situation of some of the most vulnerable patients in modern neurological practice. Seventy‐nine percent received an incorrect and/or outdated diagnosis at hospital discharge. Only 1 patient was allowed specialized clinical rehabilitation. Patients emerging to (minimal) consciousness were far outnumbered by those who died, and 50% of VS/UWS deaths were preceded by a physician's decision to discontinue ANH.

Our study also testifies of the challenges of investigating an ultrarare condition with a high mortality in the absence of adequate routine diagnostics, in a context of fragmented care without a central registry. Recruitment proved difficult, and some patients were lost even after years of follow‐up. It is likely that we missed patients recovering relatively soon after their injuries. Kaplan–Meier curves and recovery rates could not be calculated due to variable times postictus at inclusion and inclusion bias. Moreover, single assessment–based determination of level of consciousness has been associated with diagnostic error,52 especially if no accessory diagnostics are deployed. The possibility of having underestimated the included patients’ level of consciousness becomes greater when we consider that in only 9% of CRS‐R assessments were no factors possibly influencing the measurements identified. However, research publications on VS/UWS populations have rarely taken such factors into account, nor have repeated assessments (eg, 5 measurements within 14 days52) been deployed in nationwide, prospective studies.

“Why bother,” one might ask, “investing in future epidemiological research on PDOC anyway?”

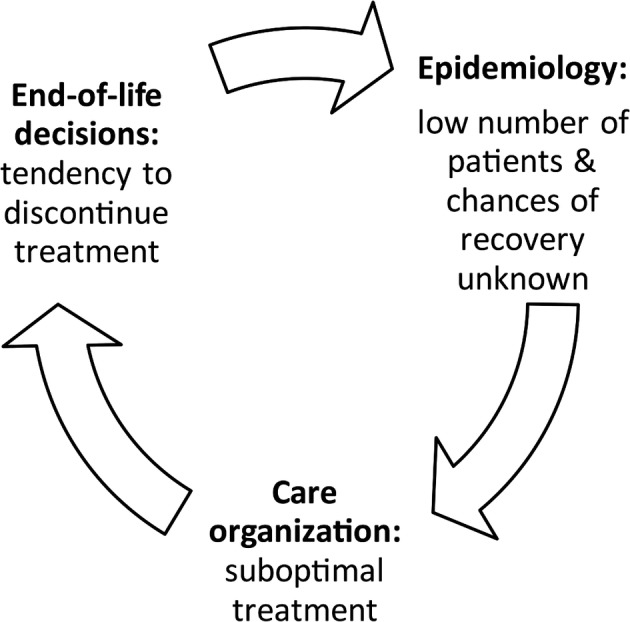

To answer this harsh but fair question, we should first acknowledge that modern medicine has a special obligation to patients who survive the worst kinds of acquired brain injury with PDOC. After all, if it were not for the medical–technological advances of the past 50 years, none of these individuals would have survived in the state they are in. Unfortunately, in many cases this survival leads to a vicious circle. In VS/UWS, epidemiology, organization of care, and end‐of‐life decisions are strongly interconnected (Fig.). Step 1: The group of patients seems small and recovery is rarely witnessed, especially by those responsible for care in the acute phase. Step 2: Because of the supposed small numbers and modest chances of meaningful recovery, care is organized ad hoc, resulting in misdiagnosis, shattered expertise, and lack of specialized rehabilitation and family counseling. Step 3: Decisions about whether to continue life‐supporting treatment are made without solid diagnosis or scientifically sound prognostics, often by a physician without knowledge of the possible long‐term outcomes and without a concrete roadmap to adequate postacute and long‐term care. This brings us back to step 1; the number of patients and their chances of recovery remain small due to a tendency to discontinue life‐prolonging treatment, and those who survive continue to receive suboptimal care.

Figure 1.

Interconnection of epidemiology, organization of care, and end‐of‐life decisions in vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome.

In order to break this vicious circle, recommendations flowing from our study results address clinicians, scientists, and policy makers and revolve around 3 themes. First of all, patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness deserve accurate and timely diagnoses. The distinction between VS/UWS and MCS is of major clinical importance; minimal signs of consciousness are associated with intact nociception and better chances of recovery,12, 53 and also translate to different ethical considerations. A mobile, outreaching team of experts could provide routine on‐site CRS‐R assessments and refer patients to specialized diagnostic facilities while simultaneously instructing local staff and relatives on behavioral signs of consciousness. It would seem useful to anonymously store these data in a central registry, so that up‐to‐date prevalence, incidence, and other epidemiologic outcomes would become available. Second, physicians must be facilitated to reach specific competencies needed in PDOC care, for example, diagnostics, therapeutic regimes, interdisciplinary collaboration, informing and guiding the patient's family, and end‐of‐life decisions, when (or preferably before) they are put in charge of such patients. Third, the way in which treatment decisions are made by physicians, how they are experienced by the families involved, and what their results are in terms of quality of life and quality of dying, have been described in monographs (eg, Fins46) but must be studied further using qualitative and quantitative methods combined. Such studies could identify the critical factors contributing to relatively early, late, and absent treatment decisions, and help construct the optimal trajectory for decision‐making in PDOC along the chain of care that supports patients, families, and health care professionals alike, as recommended in recent guidelines and reports from the AAN, the Royal College of Physicians, and the Brain Foundation Netherlands.12, 20, 54

That critical decisions about the medical treatment of some of the most helpless patients in modern medicine can be made by dedicated physicians, in close deliberation with those patients’ relatives and without judicial, legal, or media interference, can be considered a merit. However, the very responsibility that comes with this merit compels us to also provide optimal facilitation of recovery during the period of time when that recovery might take place. Patients’ potential must be supported with the same personalized care and compassion as the decision to discontinue treatment when that hoped‐for recovery does not occur. With adequate collaboration between scientists, clinicians, and policymakers, neither patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness, nor their families, should have to fall between the cracks of a disordered care system.

Author Contributions

W.S.v.E., J.C.M.L., and R.T.C.M.K. contributed to the conception and design of the study; W.S.v.E. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data; all authors drafted a significant proportion of the manuscript.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material at https://ukonnetwerk.nl/outcomes_from_a_vicious_circle_supplements

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the Stichting Beroepsopleiding Huisartsen.

We thank the patients, their families, and our colleagues for their cooperation.

References

- 1. Jennett B, Plum F. Persistent vegetative state after brain damage. A syndrome in search of a name. Lancet 1972;1:734–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laureys S, Celesia GG, Cohadon F, et al. Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC Med 2010;8:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. French JD. Brain lesions associated with prolonged unconsciousness. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1952;68:727–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Beaufort I. Patients in a vegetative state—a Dutch perspective. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2373–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Erp WS, Lavrijsen JC, van de Laar FA, et al. The vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:1361–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richter T, Nestler‐Parr S, Babela R, et al. Rare disease terminology and definitions—a systematic global review: report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Value Health 2015;18:906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Avesani R, Dambruoso F, Scandola M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 492 patients in a vegetative state in 29 Italian rehabilitation units. What about outcome? Funct Neurol 2018;33:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yelden K, Duport S, James LM, et al. Late recovery of awareness in prolonged disorders of consciousness—a cross‐sectional cohort study. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:2433–2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seel RT, Douglas J, Dennison AC, et al. Specialized early treatment for persons with disorders of consciousness: program components and outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1908–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fins JJ. Disorders of consciousness and disordered care: families, caregivers, and narratives of necessity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1934–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beljaars DE, Valckx WJ, Stepan C, et al. Prevalence differences of patients in vegetative state in the Netherlands and Vienna, Austria: a comparison of values and ethics. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015;30:E57–E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giacino JT, Katz DI, Schiff ND, et al. Practice guideline update recommendations summary: Disorders of consciousness: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Neurology 2018;91:450–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fins JJ, Bernat JL. Ethical, palliative, and policy considerations in disorders of consciousness. Neurology 2018;91:471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demertzi A, Ledoux D, Bruno MA, et al. Attitudes towards end‐of‐life issues in disorders of consciousness: a European survey. J Neurol 2011;258:1058–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asai A, Maekawa M, Akiguchi I, et al. Survey of Japanese physicians' attitudes towards the care of adult patients in persistent vegetative state. J Med Ethics 1999;25:302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jennett B. The vegetative state: medial facts, ethical and legal dilemmas. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moratti S. The Englaro Case: withdrawal of treatment from a patient in a permanent vegetative state in Italy. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2010;19:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Annas GJ. Nancy Cruzan and the right to die. N Engl J Med 1990;323:670–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quill TE. Terri Schiavo—a tragedy compounded. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1630–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royal College of Physicians. Clinically‐assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH) and adults who lack the capacity to consent. Guidance for decision‐making in England and Wales. 2018.

- 21. Wade DT. Clinically assisted nutrition and hydration. BMJ 2018;362:k3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilkinson D, Savulescu J. Current controversies and irresolvable disagreement: the case of Vincent Lambert and the role of 'dissensus'. J Med Ethics 2019;45:631–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Health Council of the Netherlands. Patients in a vegetative state [in Dutch] . Report No.: 1994/12. The Hague, the Netherlands, 1994.

- 24. Royal Dutch Medical Association . Medical end‐of‐life practice for incompetent patients: patients in a vegetative state [in Dutch]. Houten, the Netherlands/Diegem, Belgium: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, 1997:77–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koopmans RTCM, Lavrijsen JCM, Hoek F. Concrete steps toward academic medicine in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koopmans R, Pellegrom M, van der Geer ER. The Dutch move beyond the concept of nursing home physician specialists. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:746–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lavrijsen JCM, Van den Bosch JSG. Medical treatment for patients in a vegetative state; a contribution of nursing home medicine [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1990;134:1529–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lavrijsen J, van den Bosch JSG, Olthof H, Lenssen P. Allowing a patient in a vegetative state to die in hospital with a nursing home physician as the primary responsible physician [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005;149:947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lavrijsen J, van den Bosch H, Koopmans R, et al. Events and decision‐making in the long‐term care of Dutch nursing home patients in a vegetative state. Brain Inj 2005;19:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lavrijsen JC, van den Bosch JS, Koopmans RT, van Weel C. Prevalence and characteristics of patients in a vegetative state in Dutch nursing homes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:1420–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Span‐Sluyter C, Lavrijsen JCM, van Leeuwen E, Koopmans R. Moral dilemmas and conflicts concerning patients in a vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: shared or non‐shared decision making? A qualitative study of the professional perspective in two moral case deliberations. BMC Med Ethics 2018;19:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Erp WS, Lavrijsen JC, Vos PE, et al. The vegetative state: prevalence, misdiagnosis, and treatment limitations. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:85e9–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. The Multi‐Society Task Force on PVS . Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (1). N Engl J Med 1994;330:1499–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:618–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Royal Dutch Medical Association. The role of the physician in the voluntary termination of life . Utrecht, the Netherlands: Royal Dutch Medical Association, 2011.

- 36. Turner‐Stokes L. A matter of life and death: controversy at the interface between clinical and legal decision‐making in prolonged disorders of consciousness. J Med Ethics 2017;43:469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Medical Treatment Contract Act [in Dutch] . The Hague, the Netherlands: Dutch Ministry of Health, 1994.

- 38. Estraneo A, Moretta P, Loreto V, et al. Late recovery after traumatic, anoxic, or hemorrhagic long‐lasting vegetative state. Neurology 2010;75:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andrews K, Murphy L, Munday R, Littlewood C. Misdiagnosis of the vegetative state: retrospective study in a rehabilitation unit. BMJ 1996;313:13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurol 2009;9:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schiff ND. Cognitive motor dissociation following severe brain injuries. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1413–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, et al. Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. Science 2006;313:1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stafford CA, Owen AM, Fernandez‐Espejo D. The neural basis of external responsiveness in prolonged disorders of consciousness. Neuroimage Clin 2019;22:101791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parr H, Stevenson O, Woolnough P. Searching for missing people: families living with ambiguous absence. Emot Space Soc 2016;19:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kitzinger C, Kitzinger J. Withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration from minimally conscious and vegetative patients: family perspectives. J Med Ethics 2015;41:157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fins JJ. Rights come to mind: brain injury, ethics and the struggle for consciousness. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Minderhoud JM. Traumatic brain injuries [in Dutch]. Houten, the Netherlands/Mechelen, Belgium: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum, 2003.

- 48. Kitzinger J, Kitzinger C. The 'window of opportunity' for death after severe brain injury: family experiences. Sociol Health Illn 2013;35:1095–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chamberlain P. Death after withdrawal of nutrition and hydration. Lancet 2005;365:1446–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kitzinger J, Kitzinger C. Deaths after feeding‐tube withdrawal from patients in vegetative and minimally conscious states: a qualitative study of family experience. Palliat Med 2018;32:1180–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Royal Dutch Medical Association. Guideline for palliative sedation . Utrecht, the Netherlands: Royal Dutch Medical Association, 2009.

- 52. Wannez S, Heine L, Thonnard M, et al. The repetition of behavioral assessments in diagnosis of disorders of consciousness. Ann Neurol 2017;81:883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boly M, Faymonville ME, Schnakers C, et al. Perception of pain in the minimally conscious state with PET activation: an observational study. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brain Foundation of the Netherlands. Towards more awareness: Appropriate care for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. The Hague, the Netherlands: Netherlands Brain Foundation, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material at https://ukonnetwerk.nl/outcomes_from_a_vicious_circle_supplements