Since its first appearance in 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has affected >25 countries, with >2,400 cases and an extremely high fatality rate of >30%. The total number of mortalities due to MERS is already greater than that due to severe acute respiratory syndrome. MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has been confirmed to be the etiological agent. So far, dromedaries are the only known animal reservoir for MERS-CoV. Previously published serological studies showed that sera of Bactrian camels were all negative for MERS-CoV antibodies. In this study, we observed that 41% of the Bactrian camel sera and 55% of the hybrid camel sera from Dubai (where dromedaries are also present), but none of the sera from Bactrian camels in Xinjiang (where dromedaries are absent), were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies. Based on these results, we conclude that in addition to dromedaries, Bactrian and hybrid camels are also potential sources of MERS-CoV infection.

KEYWORDS: Bactrian camel, hybrid camel, MERS coronavirus, antibody

ABSTRACT

So far, dromedary camels are the only known animal reservoir for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Previous published serological studies showed that sera of Bactrian camels were all negative for MERS-CoV antibodies. However, a recent study revealed that direct inoculation of Bactrian camels intranasally with MERS-CoV can lead to infection with abundant virus shedding and seroconversion. In this study, we examined the presence of MERS-CoV antibodies in Bactrian and hybrid camels in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates (where dromedaries are also present), and Bactrian camels in Xinjiang, China (where dromedaries are absent). For the 29 serum samples from Bactrian camels in Dubai tested by the MERS-CoV spike (S) protein-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (S-ELISA) and neutralization antibody test, 14 (48%) and 12 (41%), respectively, were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies. All the 12 serum samples that were positive with the neutralization antibody test were also positive for the S-ELISA. For the 11 sera from hybrid camels in Dubai tested with the S-ELISA and neutralization antibody test, 6 (55%) and 9 (82%), respectively, were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies. All the 6 serum samples that were positive for the S-ELISA were also positive with the neutralization antibody test. There was a strong correlation between the antibody levels detected by S-ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers, with a Spearman coefficient of 0.6262 (P < 0.0001; 95% confidence interval, 0.5062 to 0.7225). All 92 Bactrian camel serum samples from Xinjiang were negative for MERS-CoV antibodies tested using both S-ELISA and the neutralization antibody test. Bactrian and hybrid camels are potential sources of MERS-CoV infection.

IMPORTANCE Since its first appearance in 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has affected >25 countries, with >2,400 cases and an extremely high fatality rate of >30%. The total number of mortalities due to MERS is already greater than that due to severe acute respiratory syndrome. MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has been confirmed to be the etiological agent. So far, dromedaries are the only known animal reservoir for MERS-CoV. Previously published serological studies showed that sera of Bactrian camels were all negative for MERS-CoV antibodies. In this study, we observed that 41% of the Bactrian camel sera and 55% of the hybrid camel sera from Dubai (where dromedaries are also present), but none of the sera from Bactrian camels in Xinjiang (where dromedaries are absent), were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies. Based on these results, we conclude that in addition to dromedaries, Bactrian and hybrid camels are also potential sources of MERS-CoV infection.

OBSERVATION

Since its first appearance in 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) has affected more than 25 countries in 4 continents, with more than 2,400 cases and an extremely high fatality rate of more than 30%. The total number of mortalities due to MERS is already greater than that due to severe acute respiratory syndrome. MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a betacoronavirus from subgenus Merbecovirus, has been confirmed to be the etiological agent (1). Human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 was found to be the cellular receptor for MERS-CoV (2). Subsequent detection of MERS-CoV and its antibodies in dromedary, or one-humped, camels (Camelus dromedarius) in various countries in the Middle East and North Africa have suggested that these animals are probably the reservoir for MERS-CoV (3–5). Other betacoronaviruses in bats from the subgenus Merbecovirus (e.g., Tylonycteris bat CoV HKU4, Pipistrellus bat CoV HKU5, Hypsugo bat CoV HKU25), and hedgehogs were found to be closely related to MERS-CoV (6–9).

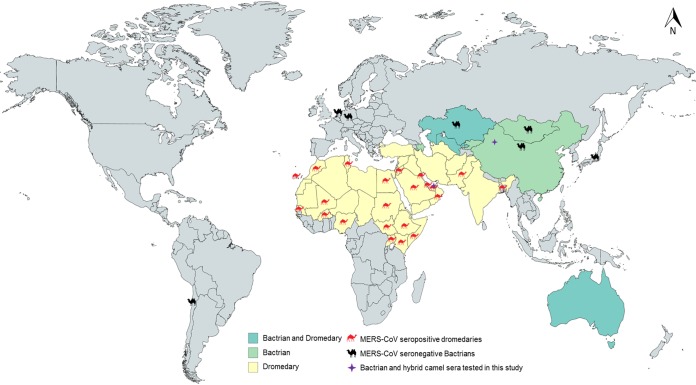

In addition to the dromedaries, there are two additional surviving Old World camels, the Bactrian, or two-humped, camels (Camelus bactrianus) and the wild Bactrian camels (Camelus ferus), both inhabitants of Central Asia. Moreover, a dromedary and a Bactrian camel can mate and result in a hybrid camel offspring. Previous published serological studies showed that sera of Bactrian camels were all negative for MERS-CoV antibodies, suggesting that Bactrian camels may not be a reservoir of MERS-CoV (Fig. 1) (10–14). However, a recent study revealed that direct inoculation of Bactrian camels intranasally with MERS-CoV can lead to infection with abundant virus shedding and seroconversion (15). Therefore, we hypothesize that those Bactrian camels, and even the hybrid camels, that reside in countries where there are dromedaries can be infected with MERS-CoV. To test this hypothesis, we examined the presence of MERS-CoV antibodies in Bactrian and hybrid camels in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates (where dromedaries are also present), and Bactrian camels in Xinjiang, China (where dromedaries are absent), using a MERS-CoV spike (S) protein-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and neutralization antibody test.

FIG 1.

Geographical distribution of dromedaries and Bactrians. Places with MERS-CoV-seropositive dromedaries (red camels) and MERS-CoV-seronegative Bactrians (black camels) from previous studies are labeled.

A total of 29 and 11 serum samples, respectively, were collected from 29 Bactrian camels and 11 hybrid camels from a private collection in Dubai (April to May 2019) (Table 1), and 92 serum samples were collected from Bactrian camels on a camel farm in Xinjiang (November 2012) (16). Antibodies against the S protein of MERS-CoV were tested using microplates precoated with purified (His)6-tagged recombinant receptor-binding domain of S (RBD-S) of MERS-CoV and detected with 1:8,000 diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-llama IgG (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) conjugate (S-ELISA) (17). The cutoff of the ELISA was defined as three standard deviations above the mean absorbance value of 10 dromedary serum samples that tested negative with the neutralization antibody test. The neutralization antibody test was performed by incubating serially diluted camel sera with 100 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) MERS-CoV for 2 hours before infecting the Vero cells for 1 hour. The cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed for 5 days, and the sera were regarded as positive for neutralizing antibody if no CPE was observed in the infected cells (18). All tests were performed in triplicate.

TABLE 1.

MERS-CoV neutralizing antibody titer of Bactrian and hybrid camel sera

| Neutralizing antibody titer | No. of samples (%) for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dubai Bactrian camel (n = 29) | Dubai hybrid camel (n = 11) | Xinjiang Bactrian camel (n = 92) | |

| <10 | 17 (58.6) | 2 (18.2) | 92 (100) |

| 10 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 20 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 40 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 80 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 160 | 1 (3.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| 320 | 2 (6.9) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

| 640 | 9 (31.1) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0) |

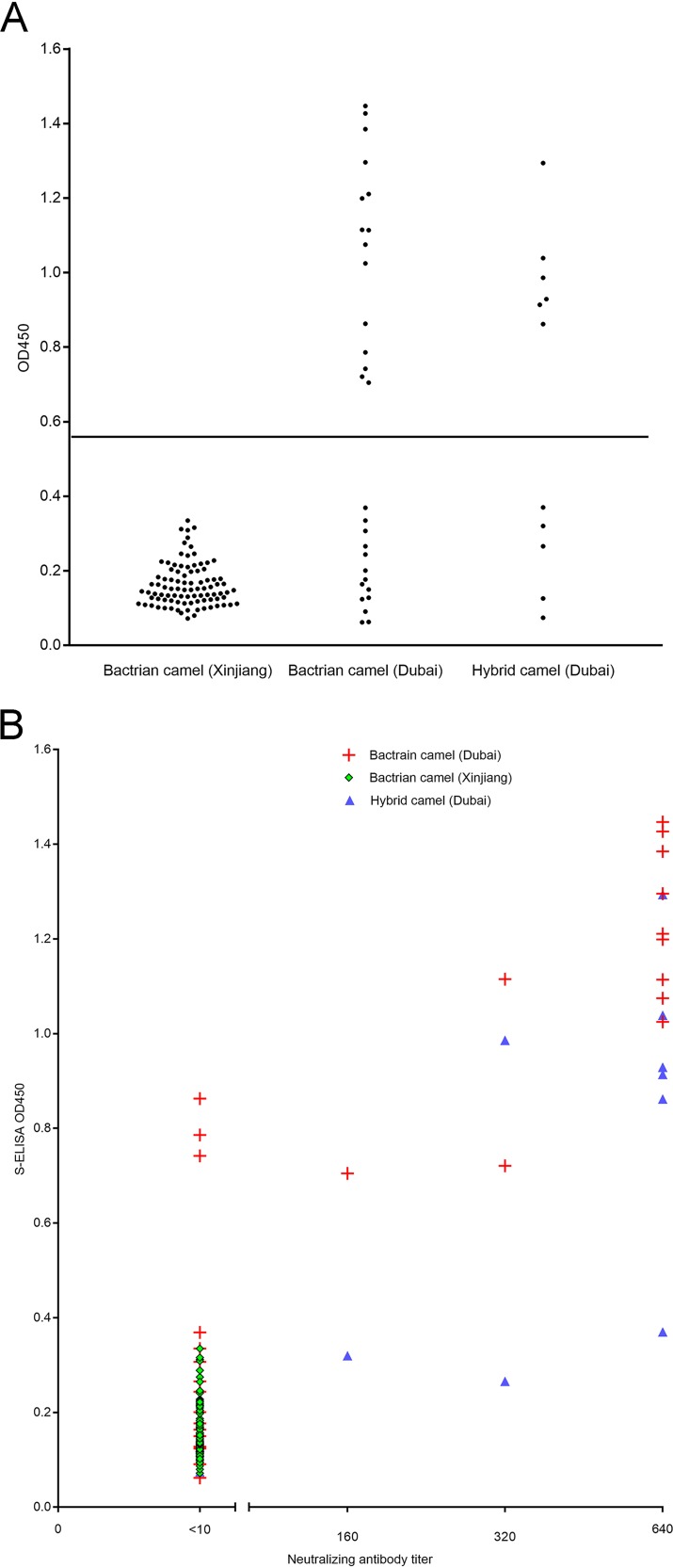

For the 29 serum samples from Bactrian camels in Dubai tested with the S-ELISA and neutralization antibody test, 14 (48%) and 12 (41%), respectively, were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies (Fig. 2A and Table 1). All the 12 serum samples that were positive with the neutralization antibody test were also positive for the S-ELISA. For the 11 serum samples from hybrid camels in Dubai tested with the S-ELISA and neutralization antibody test, 6 (55%) and 9 (82%), respectively, were positive for MERS-CoV antibodies (Fig. 2A and Table 1). All the 6 serum samples that were positive for the S-ELISA were also positive with the neutralization antibody test. There was a strong correlation between the antibody levels detected by S-ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers, with a Spearman coefficient of 0.6262 (P < 0.0001; 95% confidence interval, 0.5062 to 0.7225) (Fig. 2B). All 92 Bactrian camel serum samples from Xinjiang were negative for MERS-CoV antibodies tested with both S-ELISA and the neutralization antibody test (Fig. 2A and Table 1).

FIG 2.

(A) Scatter plot showing MERS-CoV antibody levels detected using S-ELISA in Bactrian and hybrid camel sera from Dubai and Xinjiang. The test results were plotted as optical density at 450 nm (OD450) values. The horizontal line indicates the cutoff value (0.557) for positive diagnosis. (B) Scatter plot showing correlation between antibody levels detected using S-ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers of Bactrian and hybrid camel sera for MERS-CoV.

We showed that MERS-CoV antibodies were present in Bactrian and hybrid camels from Dubai. When the reservoir of MERS-CoV was first discovered in dromedaries (3), it was wondered whether Bactrian camels are also another possible source of the virus. However, in all the studies that looked for MERS-CoV in both wild (China, n = 190; Kazakhstan, n = 95; Mongolia, n = 200) and captive (the Netherlands, n = 2; Chile, n = 2; Japan, n = 5; Germany, n = 16) Bactrian camels, it was found that none of the Bactrian camels, as tested with neutralization antibody test, ELISA, immunofluorescence assay, plaque reduction neutralization test, and/or protein microarray, had MERS-CoV antibodies (10–14). However, the sera from all these studies were obtained from Bactrian camels in geographical regions where there were no dromedaries that were positive for MERS-CoV or its antibodies. Interestingly, in a recent study that investigated the susceptibility of Bactrian camels to MERS-CoV, upon intranasal inoculation with 107 TCID50 of MERS-CoV, the Bactrian camels developed clinical signs of transient upper respiratory tract infections, such as nasal discharge and coughing, with shedding of up to 106.5 to 106.8 plaque forming units/ml of MERS-CoV from the upper respiratory tract and development of neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV (15). This suggested that Bactrian camels can be susceptible to MERS-CoV infection and may actually be another possible reservoir for MERS-CoV. In the present study, we showed that MERS-CoV antibodies were present in 41% of the Bactrian camels and 55% of the hybrid camels from a private collection in Dubai using two independent assays. These camels were kept as hobby animals. They had occasional contacts with dromedaries from camel farms that breed dromedaries for racing. MERS-CoV has been consistently detected in these camel farms in the last few years, and the MERS-CoV seropositive rate increased as the age of the dromedaries increased (17). The Bactrian camels were imported from Kazakhstan more than 10 years ago, whereas the hybrid camels were the offspring of mating between dromedaries and the Bactrian camels. Some of the hybrid camels were sometimes used for camel racing and therefore had more frequent contacts with dromedaries. It is likely that some of the Bactrian and hybrid camels might have acquired the MERS-CoV during their contacts with dromedaries that were shedding the virus, and the virus subsequently infected other Bactrian and hybrid camels in the collection.

To prevent MERS in humans, it might be worthwhile to immunize Bactrian and hybrid camels in addition to the dromedaries. So far, as determined from the results of phylogenomic analyses, several clades of MERS-CoV are circulating in dromedaries. Although it seems that the ultimate origin of MERS-CoV was from bats (6), there are still significant differences between the genome sequences of these betacoronaviruses in bats from the subgenus Merbecovirus and MERS-CoV, suggesting that interspecies jumping from bats to camels may not be a very recent event, and hence the dromedaries are probably the reservoir of MERS-CoV where the virus was transmitted to humans. In the last few years, a number of MERS-CoV vaccines have been developed for their potential use in dromedaries (19–23). In this study, our results indicated that Bactrian and hybrid camels are also potential sources of MERS-CoV infection. Therefore, Bactrian and hybrid camels, in addition to the dromedaries, should be immunized in order to reduce the chance of transmitting the virus to humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is partly supported by the Theme-based Research Scheme (project no. T11-707/15-R), University Grant Committee; the University Development Fund, The University of Hong Kong; and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Ministry of Education, China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2012. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, Dekkers DH, Müller MA, Dijkman R, Muth D, Demmers JA, Zaki A, Fouchier RA, Thiel V, Drosten C, Rottier PJ, Osterhaus AD, Bosch BJ, Haagmans BL. 2013. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Müller MA, Gutierrez C, Godeke GJ, Meyer B, Muth D, Raj VS, Smits-De Vries L, Corman VM, Drexler JF, Smits SL, El Tahir YE, De Sousa R, van Beek J, Nowotny N, van Maanen K, Hidalgo-Hermoso E, Bosch BJ, Rottier P, Osterhaus A, Gortázar-Schmidt C, Drosten C, Koopmans MP. 2013. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:859–866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau SK, Wernery R, Wong EY, Joseph S, Tsang AK, Patteril NA, Elizabeth SK, Chan KH, Muhammed R, Kinne J, Yuen KY, Wernery U, Woo PC. 2016. Polyphyletic origin of MERS coronaviruses and isolation of a novel clade A strain from dromedary camels in the United Arab Emirates. Emerg Microbes Infect 5:e128. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu DK, Hui KP, Perera RA, Miguel E, Niemeyer D, Zhao J, Channappanavar R, Dudas G, Oladipo JO, Traoré A, Fassi-Fihri O, Ali A, Demissié GF, Muth D, Chan MC, Nicholls JM, Meyerholz DK, Kuranga SA, Mamo G, Zhou Z, So RT, Hemida MG, Webby RJ, Roger F, Rambaut A, Poon LL, Perlman S, Drosten C, Chevalier V, Peiris M. 2018. MERS coronaviruses from camels in Africa exhibit region-dependent genetic diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:3144–3149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718769115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau SK, Li KS, Tsang AK, Lam CS, Ahmed S, Chen H, Chan KH, Woo PC, Yuen KY. 2013. Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 87:8638–8650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01055-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau SK, Zhang L, Luk HK, Xiong L, Peng X, Li KS, He X, Zhao PS, Fan RY, Wong AC, Ahmed SS, Cai JP, Chan JF, Sun Y, Jin D, Chen H, Lau TC, Kok RK, Li W, Yuen KY, Woo PC. 2018. Receptor usage of a novel bat lineage C betacoronavirus reveals evolution of MERS-related coronavirus spike proteins for human DPP4 binding. J Infect Dis 218:197–207. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corman VM, Kallies R, Philipps H, Göpner G, Müller MA, Eckerle I, Brünink S, Drosten C, Drexler JF. 2014. Characterization of a novel betacoronavirus related to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in European hedgehogs. J Virol 88:717–724. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01600-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau SK, Luk HK, Wong AC, Fan RY, Lam CS, Li KS, Ahmed SS, Chow FW, Cai JP, Zhu X, Chan JF, Lau TC, Cao K, Li M, Woo PC, Yuen KY. 2019. Identification of a novel betacoronavirus (Merbecovirus) in Amur hedgehogs from China. Viruses 11:980. doi: 10.3390/v11110980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan SM, Damdinjav B, Perera RA, Chu DK, Khishgee B, Enkhbold B, Poon LL, Peiris M. 2015. Absence of MERS-coronavirus in Bactrian camels, Southern Mongolia, November 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1269–1271. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.150178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu R, Wen Z, Wang J, Ge J, Chen H, Bu Z. 2015. Absence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Bactrian camels in the West Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China: surveillance study results from July 2015. Emerg Microbes Infect 4:e73. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer B, Müller MA, Corman VM, Reusken CB, Ritz D, Godeke GJ, Lattwein E, Kallies S, Siemens A, van Beek J, Drexler JF, Muth D, Bosch BJ, Wernery U, Koopmans MP, Wernery R, Drosten C. 2014. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20:552–559. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miguel E, Perera RA, Baubekova A, Chevalier V, Faye B, Akhmetsadykov N, Ng CY, Roger F, Peiris M. 2016. Absence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in camelids, Kazakhstan, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 22:555–557. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.151284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirato K, Azumano A, Nakao T, Hagihara D, Ishida M, Tamai K, Yamazaki K, Kawase M, Okamoto Y, Kawakami S, Okada N, Fukushima K, Nakajima K, Matsuyama S. 2015. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection not found in camels in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 68:256–258. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adney DR, Letko M, Ragan IK, Scott D, van Doremalen N, Bowen RA, Munster VJ. 2019. Bactrian camels shed large quantities of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) after experimental infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:717–723. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1618687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Teng JL, Lau SK, Sridhar S, Fu H, Gong W, Li M, Xu Q, He Y, Zhuang H, Woo PC, Wang L. 2019. Transmission of a novel genotype of hepatitis E virus from Bactrian camels to cynomolgus macaques. J Virol 93:e02014-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02014-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wernery U, Rasoul IH, Wong EY, Joseph M, Chen Y, Jose S, Tsang AK, Patteril NA, Chen H, Elizabeth SK, Yuen KY, Joseph S, Xia N, Wernery R, Lau SK, Woo PC. 2015. A phylogenetically distinct MERS coronavirus detected in a dromedary calf from a closed dairy herd in Dubai with rising seroprevalence along age. Emerg Microbes Infect 4:e74. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo PC, Lau SK, Wernery U, Wong EY, Tsang AK, Johnson B, Yip CC, Lau CC, Sivakumar S, Cai JP, Fan RY, Chan KH, Mareena R, Yuen KY. 2014. Novel betacoronavirus in dromedaries of the Middle East, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20:560–572. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong CY, Ong HK, Yeap SK, Ho KL, Tan WS. 2019. Recent advances in the vaccine development against Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. Front Microbiol 10:1781. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haagmans BL, van den Brand JM, Raj VS, Volz A, Wohlsein P, Smits SL, Schipper D, Bestebroer TM, Okba N, Fux R, Bensaid A, Solanes Foz D, Kuiken T, Baumgärtner W, Segalés J, Sutter G, Osterhaus AD. 2016. An orthopoxvirus-based vaccine reduces virus excretion after MERS-CoV infection in dromedary camels. Science 351:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adney DR, Wang L, van Doremalen N, Shi W, Zhang Y, Kong WP, Miller MR, Bushmaker T, Scott D, de Wit E, Modjarrad K, Petrovsky N, Graham BS, Bowen RA, Munster VJ. 2019. Efficacy of an adjuvanted Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein vaccine in dromedary camels and alpacas. Viruses 11:212. doi: 10.3390/v11030212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alharbi NK, Padron-Regalado E, Thompson CP, Kupke A, Wells D, Sloan MA, Grehan K, Temperton N, Lambe T, Warimwe G, Becker S, Hill AV, Gilbert SC. 2017. ChAdOx1 and MVA based vaccine candidates against MERS-CoV elicit neutralising antibodies and cellular immune responses in mice. Vaccine 35:3780–3788. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthumani K, Falzarano D, Reuschel EL, Tingey C, Flingai S, Villarreal DO, Wise M, Patel A, Izmirly A, Aljuaid A, Seliga AM, Soule G, Morrow M, Kraynyak KA, Khan AS, Scott DP, Feldmann F, LaCasse R, Meade-White K, Okumura A, Ugen KE, Sardesai NY, Kim JJ, Kobinger G, Feldmann H, Weiner DB. 2015. A synthetic consensus anti-spike protein DNA vaccine induces protective immunity against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med 7:301ra132. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]