Abstract

Dyspnea is the most common symptom experienced by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). To avoid exertional dyspnea, many patients adopt a sedentary lifestyle which predictably leads to extensive skeletal muscle deconditioning, social isolation, and its negative psychological sequalae. This “dyspnea spiral” is well documented and it is no surprise that alleviation of this distressing symptom has become a key objective highlighted across COPD guidelines. In reality, this important goal is often difficult to achieve, and successful symptom management awaits a clearer understanding of the underlying mechanisms of dyspnea and how these can be therapeutically manipulated for the patients’ benefit. Current theoretical constructs of the origins of activity-related dyspnea generally endorse the classical demand–capacity imbalance theory. Thus, it is believed that disruption of the normally harmonious relationship between inspiratory neural drive (IND) to breathe and the simultaneous dynamic response of the respiratory system fundamentally shapes the expression of respiratory discomfort in COPD. Sadly, the symptom of dyspnea cannot be eliminated in patients with advanced COPD with relatively fixed pathophysiological impairment. However, there is evidence that effective symptom palliation is possible for many. Interventions that reduce IND, without compromising alveolar ventilation (VA), or that improve respiratory mechanics and muscle function, or that address the affective dimension, achieve measurable benefits. A common final pathway of dyspnea relief and improved exercise tolerance across the range of therapeutic interventions (bronchodilators, exercise training, ambulatory oxygen, inspiratory muscle training, and opiate medications) is reduced neuromechanical dissociation of the respiratory system. These interventions, singly and in combination, partially restore more harmonious matching of excessive IND to ventilatory output achieved. In this review we propose, on the basis of a thorough review of the recent literature, that effective dyspnea amelioration requires combined interventions and a structured multidisciplinary approach, carefully tailored to meet the specific needs of the individual.

Keywords: COPD, Dyspnea, Respiratory physiology

Key Summary Points

| Dyspnea is the most common symptom in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), resulting in significant morbidity and alleviating dyspnea is a key objective of COPD management |

| Dyspnea is believed to result from disruption of the normal relationship between inspiratory neural drive (IND) to breathe and the dynamic response of the respiratory system |

| Therapeutic interventions including bronchodilators, exercise training, ambulatory oxygen, inspiratory muscle training, and opiates can reduce dyspnea by reducing neuromechanical dissociation of the respiratory system |

| Dyspnea management is challenging, and effective management requires combined interventions and a multidisciplinary approach tailored to the individual patient |

Introduction

Dyspnea is defined as “a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity” and is the most common symptom in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [1]. Chronic dyspnea decreases engagement in physical activity and is associated with reduced health-related quality of life and increased mortality [2, 3]. The mechanisms of dyspnea are complex and incompletely understood, and effective management of this distressing symptom is difficult. However, a personalized, patient-focused approach based on an understanding of the underlying mechanisms can yield meaningful benefits for many.

The overarching objectives of this review are (1) to consider current constructs of the neurophysiological mechanisms of activity-related breathlessness in patients with COPD, (2) to examine mechanisms of benefit of a variety of therapeutic interventions currently at our disposal, and (3) to review the evidence of the clinical efficacy of these treatments.

For the purpose of this review, the terms dyspnea, breathing discomfort, and breathlessness are used interchangeably. As a result of space constraints, the effects of endoscopic or surgical lung volume reduction and non-invasive mechanical ventilation are not discussed. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Current Constructs of Dyspnea Causation

Quoting the renowned Canadian physiologist Norman Jones [4]: “breathlessness can be seen to result from the imbalance between the demand for breathing and the ability to achieve the demand.” Accordingly, breathlessness is invariable when there is a mismatch between increased inspiratory neural drive (IND) and an inadequate mechanical response of the respiratory system. This general “imbalance” concept is intuitively appealing and widely supported. This phenomenon has variously been termed demand–capacity imbalance, efferent–afferent dissociation, neuromuscular or neuromechanical dissociation.

Normally in health, unpleasant respiratory sensation is avoided as spontaneous breathing is unimpeded and neuromechanical harmony of the respiratory system is intact [5]. However, unpleasant respiratory sensation can be provoked in healthy volunteers during experimental chemical and respiratory mechanical loading [6–10]. For example, when spontaneous tidal volume (VT) expansion is constrained in the face of increased or persistent chemostimulation, unpleasant respiratory sensations (e.g., “sense of air hunger”) are consistently perceived [11]. The same is true of young healthy subjects during exercise: combined chemical (added 0.6 L dead space, equivalent to CO2 rebreathing) and external mechanical loading (chest wall strapping to constrain VT expansion) amplified intensity of breathing discomfort and exercise intolerance to a much greater extent than either intervention in isolation [12].

Neurophysiology of Dyspnea

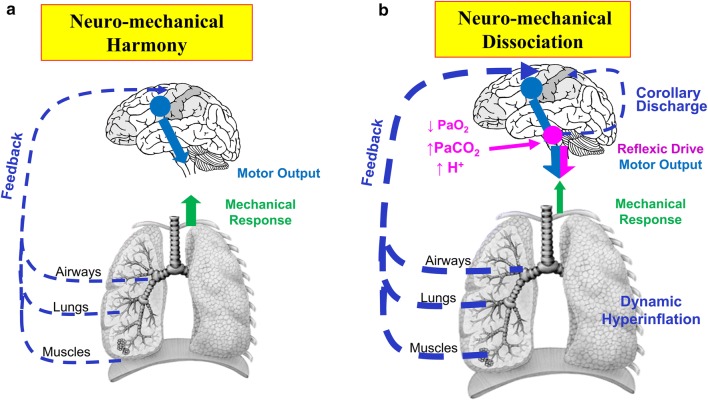

Briefly, information on the amplitude of motor command output from respiratory control centers in the medulla and cerebral cortex is relayed to the somatosensory cortex via central corollary discharge or efferent copy (Fig. 1) [13–15]. Direct chemostimulation of medullary-pontine centers is immediately associated with perceived severe breathing difficulty in healthy volunteers, even in the absence of any respiratory muscle activity [16]. It is believed that increased motor command output from cortical motor centers, in response to experimentally increased inspiratory muscle impedance or weakness, is consciously perceived as increased perceived respiratory effort [6, 16]. During external mechanical loading, diverse afferent inputs from sensory receptors throughout the respiratory system are altered or disrupted and this information is conveyed to respiratory control centers and the somatosensory cortex. The collective sensory information from both central (brain) and peripheral (respiratory system) sources is centrally integrated and the net effect of efferent–afferent dissociation results in conscious perception of unpleasant respiratory sensations, e.g., unsatisfied inspiration [13–15].

Fig. 1.

a Neuromechanical harmony and b dissociation in a patient with COPD during exertion. a Synchronous activation of the respiratory and locomotor muscles with progressive motor command output increases to maintain ventilation with activity initiation. b Arterial oxygen desaturation, increased [H+], and increased VCO2 with corresponding chemostimulation of medullary centers and increased IND as exercise continues. Resting and dynamic hyperinflation and resulting mechanical constraints lead to neuromechanical dissociation and distressing unsatisfied inspiration during exertion. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, [H+] hydrogen ion concentration, IND inspiratory neural drive, PaCO2 arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, PaO2 arterial partial pressure of oxygen, VCO2 carbon dioxide production.

Reprinted from Clin Chest Med, 40(2): Denis E. O’Donnell, Matthew D. James, Kathryn M. Milne, J. Alberto Neder, The pathophysiology of dyspnea and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 343–366, Copyright (2019), with permission from Elsevier

Beyond a certain threshold, escalating breathing difficulty is experienced as an imminent threat to life or well-being, demanding immediate behavioral action [17]. Recent studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain have shown that when neuromechanical dissociation is experimentally induced by uncoupling of chemical stimulus and mechanical response, there is increased activation of limbic and paralimbic centers which, combined with sympathetic nervous system overactivation, results in anxiety, panic, and affective distress [18].

Exertional Dyspnea in COPD

The demand–capacity imbalance theory is supported by a number of studies which show strong statistical correlations between the rise in dyspnea intensity during exercise and simultaneous increase in a number of physiological ratios which ultimately reflect increased neuromechanical disruption (Table 1). Collectively, these data support the notion that dyspnea increases as a function of increasing IND (from bulbo-pontine and cortical respiratory control centers) in the face of an ever-decreasing capacity of the respiratory system to respond.

Table 1.

Physiologic ratios highly correlated with increasing dyspnea throughout exercise

| Physiologic ratio | Response during exercise and significance |

|---|---|

| VE/MVC [103, 104] | Ventilation increasing to maximum capacity |

| Pes/Pes,max [6, 105] | Respiratory effort approaches maximum volitional value |

| VT/IC [88, 89, 106] | Mechanical constraints on tidal volume become critical |

| EMGdi/EMGdi,max [19, 20] | Tidal IND to the diaphragm approaches maximum volitional value |

EMGdi diaphragmatic electromyography, EMGdi/EMGdi,max inspiratory neural drive, IC inspiratory capacity, IND inspiratory neural drive, MVC maximum ventilatory capacity, Pes esophageal pressure, Pes,max maximum esophageal pressure, VT tidal volume, VE minute ventilation

Increased Inspiratory Neural Drive

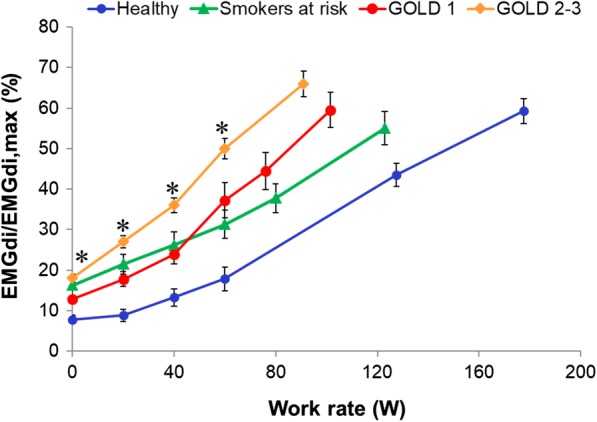

Diaphragm electromyography (EMGdi), measured using an esophageal catheter with multiple paired electrodes, generally gives a more accurate assessment of IND (EMGdi/EMGdi,max) than minute ventilation (VE) or esophageal pressures which are strongly influenced by the prevailing dynamic mechanical constraints in COPD [19–23]. During cycle ergometry in patients with COPD (compared with age- and sex-matched healthy controls), EMGdi/EMGdi,max is increased at rest and at any given level of oxygen consumption (VO2) and VE [24–26]. The slope of diaphragmatic activation versus work rate becomes steeper as pulmonary gas exchange and mechanical abnormalities worsen with COPD disease progression (Fig. 2) [24–26]. Remarkably, one recent study showed that the dyspnea-EMGdi/EMGdi,max slope is similar in subjects with COPD and those with interstitial lung disease (ILD) who have a similar resting inspiratory capacity (IC) reduction. This relationship held despite marked intergroup differences in lung compliance, breathing pattern, operating lung volumes, respiratory muscle recruitment pattern, and pulmonary gas exchange abnormalities [24]. Thus, dyspnea intensity/IND slopes were constant in these two diverse conditions despite vast differences in the source and type of afferent sensory inputs to the brain.

Fig. 2.

Inspiratory neural drive during exercise represented by diaphragmatic activation as a percentage of maximal diaphragmatic activation (EMGdi/EMGdi,max) across healthy controls, smokers, and spectrum of COPD. Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 significantly different from healthy controls at a given work rate. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EMGdi/EMGdi,max index of inspiratory neural drive to the crural diaphragm, GOLD Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, SEM standard error of the mean.

Adapted from Guenette JA, et al. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease grade 1 COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1177–1187. Adapted from Elbehairy AF, et al. Mechanisms of exertional dyspnoea in symptomatic smokers without COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):694–705. Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2019 American Thoracic Society. Faisal A, Alghamdi BJ, Ciavaglia CE, Elbehairy AF, Webb KA, Ora J, Neder JA, O’Donnell DE. 2016. Common mechanisms of dyspnea in chronic interstitial and obstructive lung disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 193(3):299–309. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society

Mechanisms of Increased Inspiratory Neural Drive in COPD

Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities and Acid–Base Imbalance

The causes of increased IND during exercise in COPD include chemical and mechanical factors (Table 2) [19, 20, 24–26]. In both healthy controls and subjects with COPD, IND increases as metabolic carbon dioxide output (VCO2) increases during exercise. Thus, exercise hyperpnea is very closely linked to pulmonary CO2 gas exchange. In COPD, ventilation–perfusion mismatch in the lung leads to inefficient pulmonary gas exchange. Dysfunction of the lung microvasculature occurs to a variable extent across the entire severity spectrum of COPD [27–29]. In mild COPD during exercise, physiological dead space, the ventilatory equivalent for CO2 (VE/VCO2)—a measure of ventilatory efficiency—and alveolar ventilation (VA) are all elevated, compared with healthy controls [27]. It is now clear that these high ventilatory requirements when combined with expiratory flow limitation (EFL) lead to worsening dynamic mechanics and earlier exercise cessation [27, 30, 31]. Additionally, the associated tachypnea and shallow breathing during exercise further increase dead space to tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) [28].

Table 2.

Stimulus for increased inspiratory neural drive to the diaphragm

| Chemical | Mechanical | Other |

|---|---|---|

|

Increased VCO2: Increased physiologic dead space Early metabolic acidosis Increased work of breathing Hypoxemia Ergoreceptor activation |

Increased respiratory muscle loading/weakness |

Altered cardiovascular afferent activity Increased sympathetic system activation |

VCO2 carbon dioxide production

Critical arterial hypoxemia (< 60 mmHg) due to the presence of lung units with low ventilation–perfusion ratios combined with low mixed venous O2 will stimulate peripheral and central chemoreceptors and further increase IND [32–35]. The rate of rise of IND during exercise is also strongly influenced by augmented chemosensitivity as manifested by a lower partial pressure of arterial CO2 (PaCO2) at rest. The respiratory control centers adjust to maintain PaCO2 within a narrow range during rest and exercise: the lower the resting PaCO2 level, the higher the IND, VA, and VE during exercise [35, 36]. The co-existence of increased chemosensitivity and high physiological dead space greatly augments IND and associated dyspnea.

In COPD, skeletal muscle deconditioning (reduced oxidative capacity) manifests as metabolic acidosis at relatively low VO2 (low anaerobic threshold)—an additional powerful ventilatory stimulus [37–41]. Exercise hyperpnea is also provoked by ascending sensory inputs from thinly myelinated (type III and IV) afferents in the active locomotor muscles [34] responding to mechanical distortion and metabolite accumulation during exercise [42].

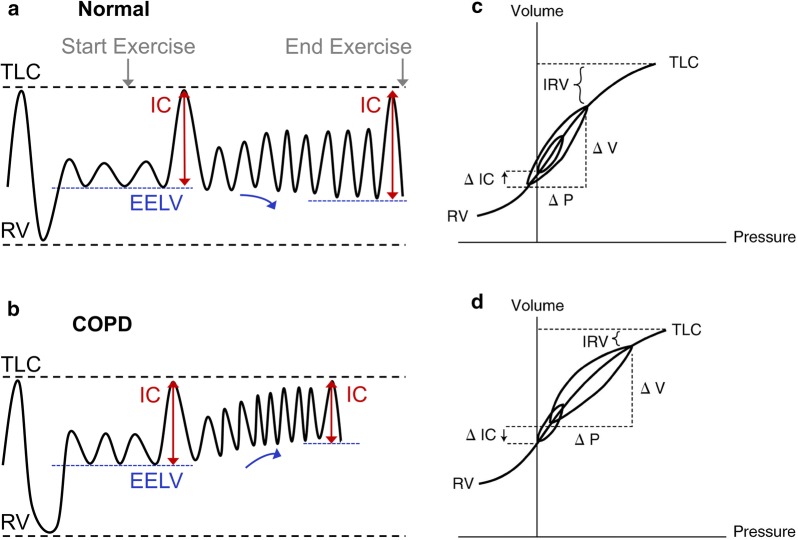

Dynamic Respiratory Mechanics

While expiratory flow limitation (EFL) is the hallmark of COPD, associated lung hyperinflation has important negative sensory consequences [43]. Emphysematous destruction of the lungs’ connective tissue matrix leads to increased lung compliance and this resets the balance of forces between inward lung recoil pressure and outward chest wall recoil at end-expiration. As a result, the relaxation volume of the respiratory system (i.e., end-expiratory lung volume, EELV) is increased compared with healthy controls (Fig. 3). In patients with EFL, EELV is also dynamically determined and is a continuous variable that is influenced by the prevailing breathing pattern. If breathing frequency (Bf) increases abruptly (and expiratory time decreases and/or VT increases) in patients with significant EFL, air trapping is inevitable, given the slow mechanical time-constant for lung emptying in COPD. Thus, during exercise, EELV increases temporarily and variably above its resting value: this is termed dynamic lung hyperinflation [44–50].

Fig. 3.

Change in EELV, IC, and IRV during exercise in a normal lungs and b COPD demonstrating change in position of VT relative to TLC on pressure–volume curve (c, d) of the respiratory system. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EELV end-expiratory lung volume, IC inspiratory capacity, IRV inspiratory reserve volume, RV residual volume, TLC total lung capacity, VT tidal volume.

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2019 American Thoracic Society. O’Donnell DE. 2006. Hyperinflation, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 3(2):180–184. The Annals of the American Thoracic Society is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society

The resting IC and inspiratory reserve volume (IRV) indicate the operating position of VT relative to total lung capacity (TLC) and the upper curvilinear portion of the relaxed respiratory system S-shaped pressure–volume relationship (Fig. 3). Breathing close to TLC means that the inspiratory muscles are foreshortened, functionally weakened, and must contend with increased elastic and inspiratory threshold loading (to overcome auto-positive end-expiratory pressure, PEEP). The difference between end-inspiratory lung volume (EILV) and TLC (i.e., the size of the IRV) largely dictates the relationship between IND and the mechanical/muscular response of the respiratory system and hence the degree of dyspnea experienced throughout exercise. In other words, the dynamic decrease in IRV provides crucial information about the extent of neuromechanical dissociation of the respiratory system and correlates strongly with dyspnea intensity ratings. The smaller the resting IC and IRV (the greater the increase in resting EELV), the shorter the time during exercise before VT reaches an inflection or plateau and dyspnea abruptly escalates. Thus, when the VT/IC ratio reaches approximately 0.7 during exercise, a widening disparity occurs between IND and the VT response [51]. IND continues to rise and VT expansion becomes progressively constrained and eventually fixed, representing the onset of severe neuromechanical dissociation [43]. At this point the qualitative descriptor “increased breathing effort” is displaced by “unsatisfied inspiration” as the dominant descriptor of dyspnea [52].

Dynamic hyperinflation results in a relatively rapid and shallow breathing pattern: the attendant increased velocity of shortening of the inspiratory muscles results in functional muscle weakness, decreases dynamic lung compliance, worsening pulmonary gas exchange (higher VD/VT) and negative cardiopulmonary interactions (reduced venous return and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction) [53–56]. With increasing mechanical impairment and progressive resting lung hyperinflation as COPD progresses, these abnormal physiological events appear at progressively lower exercise intensities.

Improving Inspiratory Neural Drive

Can We Reduce Inspiratory Neural Drive?

Unfortunately, high physiological dead space is virtually immutable in COPD especially when the cause is emphysematous destruction of the pulmonary vascular bed. First-line dyspnea-relieving therapies such as bronchodilators, which reduce regional lung hyperinflation and improve breathing pattern, result in only small increases in VA and VE with essentially no change in dead space ventilation, at least in mild to moderate COPD [57]. In more advanced COPD, modest increases in pulmonary blood flow can occur following bronchodilators and endoscopic lung volume reduction [58, 59]. Inhaled or oral vasodilator therapy also has the potential to improve pulmonary blood flow in selected patients with COPD [60]. However, the overall sensory benefits of improving regional pulmonary blood flow will depend on the net effect on ventilation–perfusion matching and in particular the degree of attenuation of wasted ventilation and reduction of IND. A summary of the interventions for dyspnea management reviewed below is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of therapeutic interventions, respective mechanisms, and examples of previously studied therapies for dyspnea alleviation in COPD

| Goal | Therapy | Mechanism | Example of use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce IND | Oa2 |

Inhibition of carotid chemoreceptor stimulation Delay lactate accumulation ↓DH (achieved by ↓Bf) |

Selection of oxygen delivery system, device, and flow rate must be tailored to the patient to best support mobility and quality of life [107]. Delivery system options include: Liquid oxygen Stationary or portable oxygen concentrator Compressed gas cylinders Device options include: Nasal cannula Simple mask Reservoir nasal cannula |

| Opiates | Alteration of central processing of dyspnea-stimulating afferent signals |

Initial dose and titration of opioids must be personalized with monitoring for adverse effects. Previously studied opioids in COPD: Orally administered morphine (both immediate release and sustained release) dose range 5 mg to 40 mg [72] |

|

| Improve respiratory mechanics | Bronchodilators |

↓DH (improve airway conductance and ↓time constant, ↑IC and delay critical ↓IRV) ↓Mechanical loading (↓elastic and inspiratory threshold loads) and ↑functional inspiratory muscle strength |

Previously studied LABA/LAMA combinations [90, 92]: Tiotropium–olodaterol 5–5 μg inhaled daily Umeclidinium bromide–vilanterol 62.5–25 μg inhaled daily |

| IMTb | ↑Functional inspiratory muscle strength at given VE and operating lung volumes |

Previously studied IMT [96]: 30 breaths (4–5 min sessions) twice to three times daily using handheld POWERbreathe KH2 device for 8 weeks |

|

| Combined | Exercise training |

↓Lactate production, VCO2, VE at given exercise intensity ↓DH (achieved by ↓Bf) |

Previously studied exercise training programs: High intensity (90% of the AT work rate) exercise for 5 days/week for 8 weeks [37] Interval training (100% peak work rate for 30 s alternating with 30 s unloaded pedaling) for 40 min/day, 2 days/week for 12 weeks [108] General exercise training program including cycle exercise and resistance training 3 days/week for 6 weeks [109] Pulmonary rehabilitation should include [85, 110]: Exercise training (endurance or interval training and resistance training) Education Psychosocial support Minimum 8 weeks duration Can occur in the inpatient or outpatient setting |

AT anaerobic threshold, Bf breathing frequency, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DH dynamic hyperinflation, IC inspiratory capacity, IMT inspiratory muscle training, IND inspiratory neural drive, IRV inspiratory reserve volume, LABA long-acting beta-2 agonist, LAMA long-acting muscarinic antagonist, PImax maximum inspiratory pressure

aSurvival benefit demonstrated in subjects with resting PaO2 ≤ 55 mmHg or PaO2 < 60 mmHg with cor pulmonale, right heart failure, or erythrocytosis [64, 65]. Qualification for long-term domiciliary oxygen varies by jurisdiction

bIn patients with COPD and inspiratory muscle weakness defined as PImax < 70 cmH2O [96]

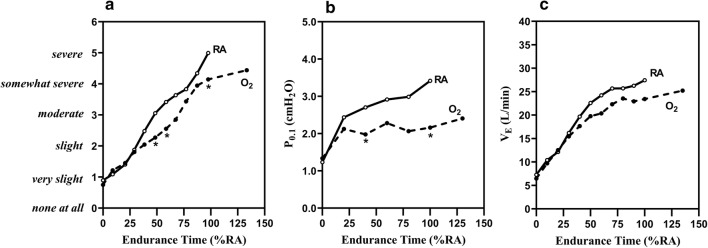

Supplemental Oxygen

Hyperoxia inhibits carotid chemoreceptor stimulation of VE during exercise by reducing Bf, resulting in a reduction in VE by approximately 3–6 L/min (Fig. 4) [61]. Additionally, improved O2 delivery to the active locomotor muscles delays lactate accumulation (hydrogen ion stimulation), and likely alters afferent inputs from peripheral muscle ergoreceptors. The effects of O2 on IND and VE are more pronounced in patients with significant baseline arterial hypoxemia but some individuals with milder exercise arterial O2 desaturation can also benefit [33, 61–63]. Other established benefits of supplemental O2 include reduced dynamic hyperinflation secondary to reduced Bf, improved cardiocirculatory function (e.g., reduced pulmonary artery resistance), and delayed skeletal muscle fatigue [34]. The relative contribution of these altered physiological responses to dyspnea relief during exercise will vary across individuals.

Fig. 4.

Improvement in a dyspnea, b P0.1 (a surrogate measure of inspiratory neural drive), and c VE with administration of oxygen in patients with moderate to severe COPD and mild exertional oxygen desaturation, not qualifying for ambulatory home oxygen. RA room air, P0.1 airway occlusion pressure, VE minute ventilation.

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2019 American Thoracic Society. O’Donnell DE, Bain DJ, Webb KA. 1997. Factors contributing to relief of exertional breathlessness during hyperoxia in chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 155(2):530–535. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society

Landmark clinical trials assessing the use of oxygen therapy in COPD have demonstrated the mortality benefit of continuous ambulatory oxygen in patients with significant hypoxemia [64, 65]. A recent systematic review examined 44 studies that assessed the impact of supplemental ambulatory oxygen on symptoms in patients with COPD who did not qualify for supplemental oxygen on the basis of thresholds from landmark studies (mean PaO2 > 55 mmHg). Oxygen supplementation reduced dyspnea in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary exercise testing compared to patients exercising without oxygen; however, evidence of an effect on daily activities was limited [63–65].

Opiates

Respiratory depression is a well-recognized complication of opioid therapy in susceptible older patients with more advanced COPD [66–72]. In clinically stable patients with COPD, careful upward titration of opiate medication is generally safe in selected patients. Abdallah et al. [73] have recently shown that a single dose of fast-acting, orally administered morphine in patients with COPD was associated with improvements in dyspnea and exercise endurance but with considerable variation in response [73]. Of interest, this subjective improvement occurred in the absence of significant decreases in IND (EMGdi/EMGdi,max), Bf, and VE. The authors speculated that opiates may alter the central processing of sensory signaling related to dyspnea and may influence the affective dimension by acting on abundant opioid receptors in cortico-limbic centers of the brain.

Although opioids are recommended for dyspnea management in patients with chronic lung disease [1], a recent systematic review of 26 studies that investigated the role of various opiates for palliation of refractory breathlessness in advanced disease determined that opiates provided a minor improvement in breathlessness scores compared to placebo (− 3.36 from baseline on 100 mm visual analog scale [VAS]; minimal clinically important difference [MCID] − 9) [74]. These studies, which included patients with refractory breathlessness despite optimal medical management, provided weak evidence for oral and parenteral administration of opiates, and no evidence for nebulized administration [74]. A recently published randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the impact of regular sustained-release orally administered morphine for chronic breathlessness (modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] ≥ 2) in patients with a range of diagnoses, including COPD, found no difference in dyspnea severity reduction between orally administered morphine and placebo arms of the study [75]. However, subjects in the morphine arm used less as needed rescue immediate release orally administered morphine [75].

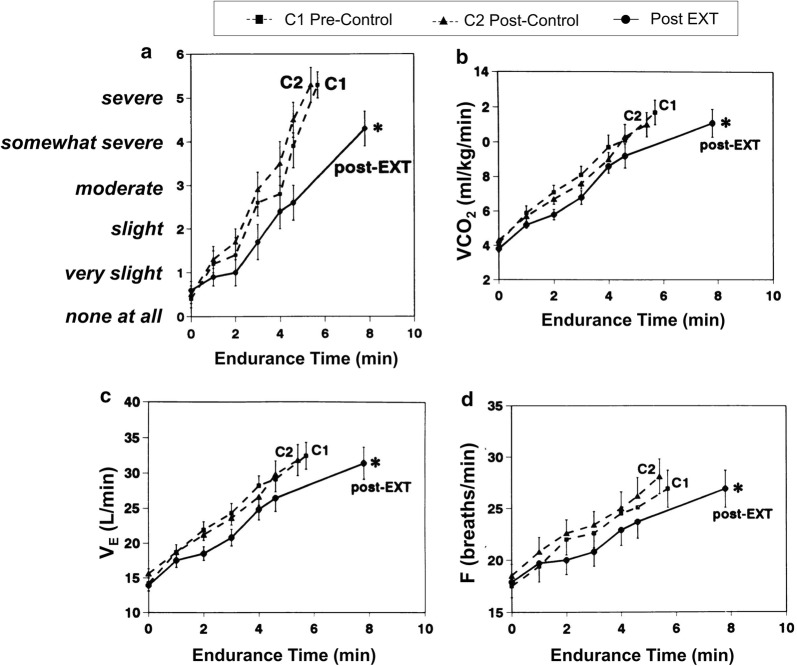

Exercise Training

In one important study, a high intensity exercise training (EXT) program was associated with consistent physiological training effects such as reduced lactic acid, VCO2, and VE at a given exercise intensity (Fig. 5) [37]. Such improvements in acid–base status likely reduce IND and dyspnea by altering central and peripheral chemoreceptor activation, in part reflecting altered activation patterns of locomotor muscle ergoreceptors. The associated reduced Bf has been shown to reduce dynamic hyperinflation with consequent delay of intolerable dyspnea [76–79]. However, it is now clear that important improvements in activity-related dyspnea, quality of life, and perceived self-efficacy can occur in the absence of consistent physiological training effects in patients with more advanced COPD [80]. Thus, supervised multicomponent, pulmonary rehabilitation programs appear to positively modify behavior and address the important affective component of dyspnea [81]. This is corroborated by a recent study which demonstrated that pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD consistently altered brain activity in stimulus valuation networks, measured by brain fMRI [82]. A systematic review of 65 RCTs of pulmonary rehabilitation programs demonstrated significant improvement in dyspnea and pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended in international guidelines for patients with COPD and persistent dyspnea [83–85]. It was noted that these programs enhanced the patients’ sense of control over their condition and significantly improved health-related quality of life [83].

Fig. 5.

Reduced a exertional breathlessness during constant-load cycle exercise after exercise training (EXT) or control intervention in patients with COPD. Slopes of b carbon dioxide output (VCO2), c ventilation (VE), and d breathing frequency also fell significantly after EXT. *p < 0.05. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EXT exercise training, F breathing frequency, VCO2 carbon dioxide production, VE minute ventilation, VT tidal volume.

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2019 American Thoracic Society. O’Donnell DE, McGuire M, Samis L, Webb KA. 1998. General exercise training improves ventilatory and peripheral muscle strength and endurance in chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 157(5):1489–1497. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society

Improving Ventilatory Capacity: Respiratory Mechanics and Muscle Function

Reducing Lung Hyperinflation

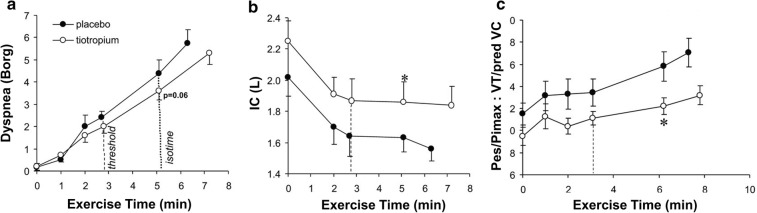

Bronchodilators improve airway conductance and shorten the time constant for lung emptying. In this way, they reduce lung hyperinflation [86]. The resultant increase in IC and IRV allows greater VT expansion and higher VE during exercise with a delay in reaching critical mechanical limits where dyspnea becomes intolerable [30]. Increased IC at rest and during exercise means that VT occupies a lower position on the sigmoidal pressure–volume curve of the relaxed respiratory system (Fig. 6). Thus, the net effect is reduced intrinsic mechanical loading (i.e., elastic and inspiratory threshold loads) and increased functional strength of the inspiratory muscles. Ultimately, lung deflation partially restores a more harmonious relationship between IND and VT displacement: less effort is now required for a given or greater VT (Fig. 6) [87–89].

Fig. 6.

Ventilatory responses to CWR exercise between tiotropium and placebo demonstrating reduced b dynamic hyperinflation with c improved musculo-mechanical coupling and a reduced dyspnea. CWR constant work rate, IC inspiratory capacity, Pes/PImax tidal esophageal pressure relative the maximum esophageal inspiratory pressure, VT tidal volume.

Adapted from O’Donnell DE, Hamilton AL, Webb KA. Sensory-mechanical relationships during high-intensity, constant-work-rate exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(4):1025–1035

The superiority of dual combined long-acting beta-2 agonist and muscarinic antagonist (LABA/LAMA) bronchodilators relative to the individual mono-components is modest at best [90, 91]. A systematic review of 99 RCTs indicates that while dual long-acting bronchodilators often reduce dyspnea, increase lung function (improved forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FEV1), and improve quality of life compared to single long-acting bronchodilators or LABA/inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) combinations [92], these results are not consistent and vary in magnitude. Current guidelines recommend LABA/LAMA combination therapy for patients whose symptoms are not controlled by a single long-acting bronchodilator [84, 93–95].

Inspiratory Muscle Training (IMT)

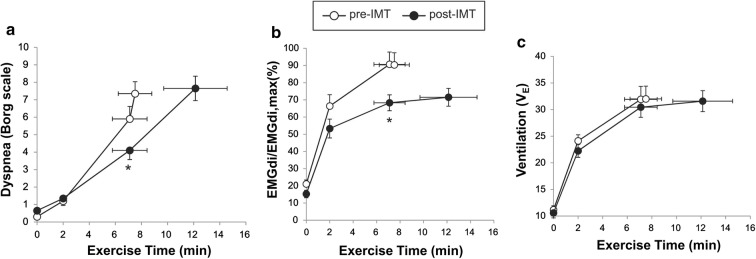

In a recent study Langer et al. [96] showed that supervised IMT in patients with severe COPD and baseline inspiratory muscle weakness was associated with increased inspiratory muscle strength, reduced dyspnea, and improved exercise tolerance compared with sham training (Fig. 7). In the active IMT group, IND fell significantly over the increased exercise endurance time (> 3 min) during which VE was sustained at approximately 30 L/min (Fig. 7). Of interest, IND (EMGdi/EMGdi,max) was diminished after IMT in a setting of no change in VE, breathing pattern, or operating lung volumes. This study, therefore, supports the notion that when the inspiratory muscles are weakened in COPD, the rise in IND during exercise reflects increasing motor command output from cortical centers in the brain to maintain force generation commensurate with the ventilatory demand. The increased IND under these conditions contributed to exertional dyspnea: reduced IND and dyspnea as muscle function improved supports this contention.

Fig. 7.

Improvement in a dyspnea, b inspiratory neural drive (EMGdi/EMGdi,max), and c ventilation following IMT in patients with COPD and evidence of inspiratory muscle weakness. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EMGdi/EMGdi,max index of inspiratory neural drive to the crural diaphragm, IMT inspiratory muscle training, VE minute ventilation.

Adapted from Langer D, Ciavaglia C, Faisal A, Webb KA, Neder JA, Gosselink R, Dacha S, Topalovic M, Ivanova A, O’Donnell DE. Inspiratory muscle training reduces diaphragm activation and dyspnea during exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2018;125(2):381–392

A meta-analysis of 32 RCTs on the effects of IMT in patients with COPD spanning all disease severities showed that IMT led to a significant reduction in dyspnea (Borg score − 0.9 units; TDI + 2.8 units) compared to patients without IMT [97]. A systematic review of studies that evaluated the utility of IMT in patients with COPD showed that IMT reduces symptoms of dyspnea (Borg scale − 0.52 units difference, IMT vs. control; baseline and transition dyspnea index [BDI-TDI]: 2.30 units difference, IMT vs. control). The minimal clinically important difference for TDI is 1 unit [98]. There was no benefit of adjunctive IMT in patients completing a pulmonary rehabilitation program [99].

Challenges of Dyspnea Management in COPD

Effective dyspnea management for patients with COPD presents an important challenge requiring comprehensive clinical history taking and a basic understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms of dyspnea as discussed. Multiple contributory factors often exist and need to be identified and treated to optimize individual management. These include negative effects of obesity or malnutrition, anxiety and depression, and impairment in cardiocirculatory and musculoskeletal function. The symptom of dyspnea is a uniquely personal experience and difficult to quantify numerically with magnitude-of-tasks questionnaires (mMRC) or even multicomponent questionnaires which evaluate intensity, quality, affective dimension, and impact on quality of life (BDI-TDI) [98, 100, 101].

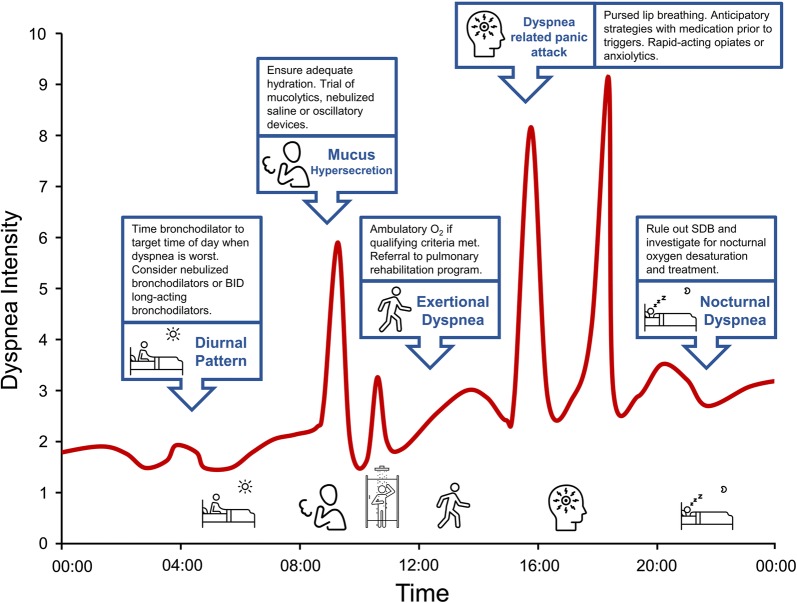

Patients with COPD may present with very different individual dyspnea profiles (Fig. 8). Some patients experience increased nighttime and early morning dyspnea. Distressing dyspnea is often provoked by bouts of coughing and difficult sputum expectoration. Dyspnea may be predominantly associated with physical activity or be characterized by a gradual increase in intensity and fatigue throughout the day, punctuated by episodes of “breakthrough” dyspnea or crisis. Each scenario requires a personalized approach to management that ideally is tailored to the individual’s dyspnea profile.

Fig. 8.

Individual dyspnea intensity profile of a patient with COPD and highlighted management interventions targeting dyspnea triggers and underlying physiological mechanisms. BID twice daily, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SDB sleep disordered breathing. Icons presented in the figure from the Noun Project

According to most current recommendations [1], the first step in alleviating dyspnea in COPD is to optimize bronchodilator therapy to improve respiratory mechanics and muscle function, thus increasing exercise capacity. The second step is to promote regular physical activity or, if at all possible, to enroll the patient in a supervised, multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation program. A recent study has demonstrated that patients with moderate to severe chronic activity-related breathlessness are not referred to pulmonary rehabilitation programs despite evidence that these patients derive benefit [102]. Potential additional benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation include improved peripheral muscle function and acid–base balance with reduced IND and secondary improvements in dynamic respiratory mechanics and muscle function. Individualized inspiratory muscle training may benefit some patients with advanced COPD who have objective inspiratory muscle weakness. For selected individuals with severe dyspnea and significant arterial O2 desaturation during (SpO2 < 88% O2 for more than two consecutive minutes) a weight-bearing endurance test, a trial of ambulatory O2 treatment should be considered to facilitate increased physical activity. Opiates are generally reserved for patients with incapacitating dyspnea and need to be carefully supervised.

Taken together, the majority of clinical trials on efficacy of common treatment interventions report only minor gains in dyspnea alleviation compared with placebo. This reflects the vast pathophysiological heterogeneity of COPD with consequent variability in response patterns to any single intervention. Many dyspnea assessment instruments, currently at our disposal, lack the sensitivity to measure the longitudinal impact of single or combined interventions on the daily burden of dyspnea. It must be emphasized that multidisciplinary management is generally required for refractory dyspnea and this should be tailored to the specific needs of the individual, determined by careful evaluation. Thus, refinements in evaluation of patterns of precipitation of dyspnea and individual daily profiles might offer greater precision in the future development of more effective symptom management.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Dr. DE O’Donnell has received research funding via Queen’s University from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Respiratory Research Network, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim and has served on speaker bureaus, consultation panels and advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis. Dr. JA Neder has received research funding via Queen’s University from Boehringer Ingelheim and has served on speaker bureaus, consultation panels and advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis. Mr. Matthew D. James, Dr. Kathryn M. Milne, and Dr. Juan Pablo de Torres have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.9970322.

References

- 1.Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4):435–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pumar MI, Gray CR, Walsh JR, Yang IA, Rolls TA, Ward DL. Anxiety and depression-important psychological comorbidities of COPD. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(11):1615–1631. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maltais F, Decramer M, Casaburi R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(9):e15–e62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones NL. The ins and outs of breathing: how we learnt about the body’s most vital function. Bloomington: iUniverse; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen D, Ofir D, O’Donnell DE. Effects of pregnancy, obesity and aging on the intensity of perceived breathlessness during exercise in healthy humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Killian KJ, Gandevia SC, Summers E, Campbell EJ. Effect of increased lung volume on perception of breathlessness, effort, and tension. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57(3):686–691. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.3.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Manshawi A, Killian KJ, Summers E, Jones NL. Breathlessness during exercise with and without resistive loading. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61(3):896–905. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane R, Adams L, Guz A. Is low-level respiratory resistive loading during exercise perceived as breathlessness? Clin Sci. 1987;73:627–634. doi: 10.1042/cs0730627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell EJ, Gandevia SC, Killian KJ, Mahutte CK, Rigg JR. Changes in the perception of inspiratory resistive loads during partial curarization. J Physiol. 1980;309:93–100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moosavi SH, Topulos GP, Hafter A, et al. Acute partial paralysis alters perceptions of air hunger, work and effort at constant P(CO(2)) and V(E) Respir Physiol. 2000;122:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banzett RB, Lansing RW, Brown R, et al. ‘Air hunger’ from increased PCO2 persists after complete neuromuscular block in humans. Respir Physiol. 1990;81(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(90)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Donnell DE, Hong HH, Webb KA. Respiratory sensation during chest wall restriction and dead space loading in exercising men. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(5):1859–1869. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Eldridge FL, Wagner PG. Respiratory-associated thalamic activity is related to level of respiratory drive. Respir Physiol. 1992;90(1):99–113. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90137-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Eldridge FL, Wagner PG. Respiratory-associated rhythmic firing of midbrain neurones in cats: relation to level of respiratory drive. J Physiol. 1991;437:305–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eldridge FL, Millhorn DE, Waldrop TG. Exercise hyperpnea and locomotion: parallel activation from the hypothalamus. Science. 1981;211(4484):844–846. doi: 10.1126/science.7466362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandevia SC, Killian K, McKenzie DK, et al. Respiratory sensations, cardiovascular control, kinaesthesia and transcranial stimulation during paralysis in humans. J Physiol. 1993;470:85–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Leupoldt A, Sommer T, Kegat S, et al. The unpleasantness of perceived dyspnea is processed in the anterior insula and amygdala. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(9):1026–1032. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1821OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoeckel MC, Esser RW, Gamer M, Buchel C, von Leupoldt A. Brain responses during the anticipation of dyspnea. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6434987. doi: 10.1155/2016/6434987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolley CJ, Luo YM, Steier J, Rafferty GF, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Neural respiratory drive and breathlessness in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(2):355–364. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolley CJ, Luo YM, Steier J, et al. Neural respiratory drive in healthy subjects and in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(2):289–297. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00093408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lou YM, Hart N, Mustfa N, Lyall RA, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Effect of diaphragm fatigue on neural respiratory drive. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90(5):1691–1699. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou YM, Lyall RA, Harris ML, et al. Effect of lung volume on the oesophageal diaphragm EMG assessed by magnetic phrenic nerve stimulation. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(6):1033–1038. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lou YM, Moxham J. Measurment of neural respiratory drive in patients with COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;146(2–3):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faisal A, Alghamdi BJ, Ciavaglia CE, et al. Common mechanisms of dyspnea in chronic interstitial and obstructive lung disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(3):299–309. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0841OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guenette JA, Chin RC, Cheng S, et al. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease grade 1 COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1177–1187. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00034714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbehairy AF, Guenette JA, Faisal A, et al. Mechanisms of exertional dyspnoea in symptomatic smokers without COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):694–705. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00077-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbehairy AF, Ciavaglia CE, Webb KA, et al. Pulmonary gas exchange abnormalities in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: implications for dyspnea and exercise intolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(12):1384–1394. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0157OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neder JA, Berton DC, Muller PT, et al. Ventilatory inefficiency and exertional dyspnea in early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(Supplement_1):S22–S29. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1033FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hueper K, Vogel-Claussen J, Parikh MA, et al. Pulmonary microvascular blood flow in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema: the MESA COPD study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(5):570–580. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2120OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chin RC, Guenette JA, Cheng S, et al. Does the respiratory system limit exercise in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1315–1323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1970OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Lam YM, O’Donnell DE. Mechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(6):622–629. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1064OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amann M, Regan MS, Kobitary M, et al. Impact of pulmonary system limitations on locomotor muscle fatigue in patients with COPD. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299(1):314–324. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00183.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Donnell DE, D’Arsigny C, Webb KA. Effects of hyperoxia on ventilatory limitation during exercise in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(4):892–898. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2007026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponikowski PP, Chua TP, Francis DP, Capucci A, Coats AJ, Piepoli MF. Muscle ergoreceptor overactivity reflects deterioration in clinical status and cardiorespiratory reflex control in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104(19):2324–2330. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.098491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porszasz J, Emtner M, Goto S, Somfay A, Whipp BJ, Casaburi R. Exercise training decreases ventilatory requirements and exercise-induced hyperinflation at submaximal intensities in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128(4):2025–2034. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ward SA, Whipp BJ. Kinetics of the ventilatory and metabolic responses to moderate-intensity exercise in humans following prior exercise-induced metabolic acidaemia. New Front Respir Control. 2009;669:323–326. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5692-7_66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casaburi R, Patessio A, Ioli F, Zanaboni S, Donner CF, Wasserman K. Reductions in exercise lactic acidosis and ventilation as a result of exercise training in patients with obstructive lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(1):9–18. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patessio A, Casaburi R, Carone M, Appendini L, Donner CF, Wasserman K. Comparison of gas exchange, lactate, and lactic acidosis thresholds in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am RevRespir Dis. 1993;148(3):622–626. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maltais F, Leblanc P, Simard C, et al. Skeletal muscle adaptation to endurance training in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(2):442–447. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maltais F, Simard AA, Simard C, Jobin J, Desgagnés P, Leblanc P. Oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle and lactic acid kinetics during exercise in normal subjects and in patients with COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1):288–293. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sue DY, Chung MM, Grosvenor M, Wasserman K. Effect of altering the proportion of dietary fat and carbohydrate on exercise gas exchange in normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139(6):1430–1434. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.6.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gagnon P, Bussieres JS, Ribeiro F, et al. Influences of spinal anesthesia on exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):606–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Donnell DE. Hyperinflation, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(2):180–184. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-093DO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olafsson S, Hyatt RE. Ventilatory mechanics and expiratory flow limitation during exercise in normal subjects. J Clin Invest. 1969;48(3):564–573. doi: 10.1172/JCI106015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dodd DS, Brancatisano T, Engel LA. Chest wall mechanics during exercise in patients with severe chronic air-flow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129(1):33–38. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stubbing DG, Pengelly LD, Morse JLC, Jones NL. Pulmonary mechanics during exercise in subjects with chronic airflow obstruction. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49:511–515. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Similowski T, Yan S, Gauthier AP, Macklem PT, Bellemare F. Contractile properties of the human diaphragm during chronic hyperinflation. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(13):917–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Donnell DE, Travers J, Webb KA, et al. Reliability of ventilatory parameters during cycle ergometry in multicentre trials in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(4):866–874. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00168708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puente-Maestu L, Palange P, Casaburi R, et al. Use of exercise testing in the evaluation of interventional efficacy: an official ERS statement. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):429–460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00745-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palange P, Ward SA, Carlsen KH, et al. Recommendations on the use of exercise testing in clinical practice. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(1):185–209. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Donnell DE, Guenette JA, Maltais F, Webb KA. Decline of resting inspiratory capacity in COPD: the impact on breathing pattern, dyspnea, and ventilatory capacity during exercise. Chest. 2012;141(3):753–762. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Ora J, Wadell K, O’Donnell DE. Evolution of dyspnea during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact of critical volume constraints. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(12):1367–1373. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-1128OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laveneziana P, Palange P, Ora J, Martolini D, O’Donnell DE. Bronchodilator effect on ventilatory, pulmonary gas exchange, and heart rate kinetics during high-intensity exercise in COPD. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;107(6):633–643. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laveneziana P, Valli G, Onorati P, Paoletti P, Ferrazza AM, Palange P. Effect of heliox on heart rate kinetics and dynamic hyperinflation during high-intensity exercise in COPD. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(2):225–234. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1643-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiappa GR, Borghi-Silva A, Ferreira LF, et al. Kinetics of muscle deoxygenation are accelerated at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in patients with COPD: relationship to central cardiovascular dynamics. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(5):1341–1350. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01364.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berton DC, Barbosa PB, Takara LS, et al. Bronchodilators accelerate the dynamics of muscle O2 delivery and utlisation during exercise in COPD. Thorax. 2010;65(7):588–593. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.120857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elbehairy AF, Webb KA, Laveneziana P, Domnik NJ, Neder JA, O’Donnell DE. Acute bronchodilator therapy does not reduce wasted ventilation during exercise in COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2018;252–253:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vogel-Claussen J, Schönfeld C-O, Kaireit TF, et al. Effect of indacaterol/glycopyrronium on pulmonary perfusion and ventilation in hyperinflated COPD patients (CLAIM): a double-blind, randomised, crossover trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1086–1096. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-0995OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Estepar RS, Kinney GL, Black-Shinn JL, et al. Computed tomographic measures of pulmonary vascular morphology in smokers and their clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(2):231–239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iyer KS, Newell J, Jin D, et al. Quantitative dual-energy computed tomography supports a vascular etiology of smoking-induced inflammatory lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(6):652–661. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1196OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peters MM, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Combined physiological effects of bronchodilators and hyperoxia on exertional dyspnoea in normoxic COPD. Thorax. 2006;61(7):559–567. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.053470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Donnell DE, Bain DJ, Webb KA. Factors contributing to relief of exertional breathlessness during hyperoxia in chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(2):530–535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ekström M, Ahmadi Z, Bornefalk‐Hermansson A, Abernethy A, Currow D. Oxygen for breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who do not qualify for home oxygen therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(11):CD006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(3):391–398. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stuart-Harris C, Bishop JM, Clark TJH, et al. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema: report of the Medical Research Council working party. Lancet. 1981;317(8222):681–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vozoris NT, Wang X, Austin PC, et al. Adverse cardiac events associated with incident opioid drug use among older adults with COPD. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(10):1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vozoris NT, Wang X, Fischer HD, et al. Incident opioid drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):683–693. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01967-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vozoris NT, Wang X, Fischer HD, et al. Incident opioid drug use among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(1):161–170. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jensen D, Alsuhail A, Viola R, Dudgeon DJ, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Inhaled fentanyl citrate improves exercise endurance during high-intensity constant work rate cycle exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(4):706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson MJ, Bland JM, Oxberry SG, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. Opioids for chronic refractory breathlessness: patient predictors of beneficial response. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(3):758–766. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00139812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rocker GM, Simpson AC, Horton R, et al. Opioid therapy for refractory dyspnea in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patients’ experiences and outcomes. CMAJ Open. 2013;1(1):E27–E36. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20120031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ekstrom M, Nilsson F, Abernethy AA, Currow DC. Effects of opioids on breathlessness and exercise capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(7):1079–1092. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abdallah SJ, Wilkinson-Maitland C, Saad N, et al. Effect of morphine on breathlessness and exercise endurance in advanced COPD: a randomised crossover study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1701235. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01235-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnes H, McDonald J, Smallwood N, Manser R. Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3(3):CD011008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011008.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Currow David, Louw Sandra, McCloud Philip, Fazekas Belinda, Plummer John, McDonald Christine F, Agar Meera, Clark Katherine, McCaffery Nikki, Ekström Magnus Pär. Regular, sustained-release morphine for chronic breathlessness: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2019;75(1):50–56. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Donnell DE, Webb KA. Exertional breathlessness in patients with chronic airflow limitation: the role of lung hyperinflation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148(5):1351–1357. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Somfay A, Porszasz J, Lee SM, Casaburi R. Dose-response effect of oxygen on hyperinflation and exercise endurance in nonhypoxaemic COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(1):77–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00082201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Donnell DE, D’Arsigny C, Fitzpatrick M, Webb KA. Exercise hypercapnia in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of lung hyperinflation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):663–668. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2201003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Wadell K, Neder JA, O’Donnell DE. Does expiratory muscle activity influence dynamic hyperinflation and exertional dyspnea in COPD? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;199:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wadell K, Webb KA, Preston ME, et al. Impact of pulmonary rehabilitation on the major dimensions of dyspnea in COPD. COPD. 2013;10(4):425–435. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.758696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gordon CS, Waller JW, Cook RM, Cavalera SL, Lim WT, Osadnik CR. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on symptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2019;156(1):80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herigstad M, Faull OK, Hayen A, et al. Treating breathlessness via the brain: changes in brain activity over a course of pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1701029. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01029-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2019 report). 2019. https://goldcopd.org/. Accessed 5 Sept 2019.

- 85.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O’Donnell DE, Laveneziana P. The clinical importance of dynamic lung hyperinflation in COPD. COPD. 2006;3:219–232. doi: 10.1080/15412550600977478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Donnell DE, Hamilton AL, Webb KA. Sensory-mechanical relationships during high-intensity, constant-work-rate exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(4):1025–1035. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01470.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O’Donnell DE, Sciurba F, Celli B, et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on lung hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPD. Chest. 2006;130(3):647–656. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Donnell DE, Voduc N, Fitzpatrick M, Webb KA. Effect of salmeterol on the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(1):86–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00072703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Calzetta L, Ora J, Cavalli F, Rogliani P, O’Donnell DE, Cazzola M. Impact of LABA/LAMA combination on exercise endurance and lung hyperinflation in COPD: a pair-wise and network meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2017;129:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Calzetta L, Rogliani P, Matera MG, Cazzola M. A systematic review with meta-analysis of dual bronchodilation with LAMA/LABA for the treatment of stable COPD. Chest. 2016;149(5):1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oba Y, Keeney E, Ghatehorde N, Dias S. Dual combination therapy versus long‐acting bronchodilators alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;(12):CD012620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14:5B–32B. doi: 10.1155/2007/830570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wedzicha JA, Calverley PMA, Albert RK, et al. Prevention of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1602265. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02265-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):179–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Langer D, Ciavaglia CE, Faisal A, et al. Inspiratory muscle training reduces diaphragm activation and dyspnea during exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol. 2018;125:381–392. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01078.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gosselink R, De Vos J, van den Heuvel SP, Segers J, Decramer M, Kwakkel G. Impact of inspiratory muscle training in patients with COPD: what is the evidence? Eur Respir J. 2011;37(2):416–425. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00031810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mahler DA, Waterman LA, Ward J, McCusker C, ZuWallack R, Baird JC. Validity and responsiveness of the self-administered computerized versions of the baseline and transition dyspnea indexes. Chest. 2007;132(4):1283–1290. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beaumont M, Forget P, Couturaud F, Reychler G. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in COPD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(7):2178–2188. doi: 10.1111/crj.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Banzett RB, O’Donnell CR, Guilfoyle TE, et al. Multidimensional dyspnea profile: an instrument for clinical and laboratory research. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(6):1681–1691. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00038914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Banzett RB, Moosavi SH. Measuring dyspnoea: new multidimensional instruments to match our 21st century understanding. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1602473. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02473-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kochovska Slavica, Fazekas Belinda, Hensley Michael, Wheatley John, Allcroft Peter, Currow David C. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multisite, Pilot, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Regular, Low-Dose Morphine on Outcomes of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in COPD. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2019;58(5):e7–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Means JH. Dyspnea: medical monograph. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1924. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cournand A, Richards DW. Pulmonary insufficiency, Part IL discussion of a physiological classification and presentation of clinical tests. Am Rev Tuberc. 1941;44:26–41. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bradley TD, Chartrand DA, Fitting JW, Killian KJ, Grassino A. The relation of inspiratory effort sensation to fatiguing patterns of the diaphragm. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134(6):1119–1124. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Donnell DE, Revill SM, Webb KA. Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(5):770–777. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2012122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jacobs SS, Lederer DJ, Garvey CM, et al. Optimizing home oxygen therapy: an official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(12):1369–1381. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201809-627WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vogiatzis I, Nanas S, Roussos C. Interval training as an alternative modality to continuous exercise in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(1):12–19. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01152001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.O’Donnell DE, McGuire M, Samis L, Webb KA. General exercise training improves ventilatory and peripheral muscle strength and endurance in chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(5 Pt 1):1489–1497. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9708010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–1386. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.