Abstract

Developmental patterns of personality pathology traits are not well delineated from childhood through late adolescence. In the present study, participants (N= 675, 56% female) were recruited to create three cohorts of 3rd (n = 205), 6th (n = 248), and 9th (n = 222) graders to form an accelerated longitudinal cohort design. We assessed six PD (avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, schizotypal) traits based on DSM-IV trait diagnostic conceptualizations via parent report at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months. According to parent report, mean levels of avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits all declined for both boys and girls. The changes in dependent and histrionic traits were of medium effect size, and the changes in avoidant, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits were of small effect size. Over the three years of the study, the traits of each PD also demonstrated moderate to high rank-order stability.

Personality disorders (PDs) are costly and distressing on both an individual and societal level and may lead to higher levels of global impairment than other forms of psychopathology, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) (Skodol, 2018). PDs are associated with substantial physical and mental health comorbidities (Dixon-Gordon, Conkey, & Whalen, 2018) along with disproportionately high health care service utilization (Quirk et al., 2016). Individuals with schizotypal and borderline PDs have higher rates of unemployment and twice the probability of disability status than those with MDD (Skodol et al., 2005). Given widely held views that personality traits do not form into stable dispositions until adulthood, PDs were historically assessed and evaluated primarily in adults. Personality pathology is understudied in youth; however, this does not mean that PD traits are uncommon in children and adolescents. Indeed, it has been estimated that 6% to 17% of adolescents in community settings meet criteria for one or more PD diagnoses (Kongerslev et al., 2015) and their peak prevalence may occur during early and middle adolescence (Bernstein et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1999). Previous studies have reliably and validly measured traits of narcissism (Barry et al., 2003, 2007; Thomaes et al., 2008) and borderline (Crick et al., 2005) in pre-adolescents.

Mapping normative developmental trajectories of PD traits in youth can inform future work on etiological risk factors of personality pathology. However, few studies have examined the longitudinal development of PD traits during adolescence, and almost none have done so during childhood (Kongerslev et al., 2015). To our knowledge, only one prior longitudinal study, the Children in the Community (CIC) study (Cohen et al., 2005), included repeated assessments of multiple forms of PD traits (i.e., avoidant, borderline, dependent, depressive, histrionic, narcissistic, paranoid, obsessive-compulsive, passive-aggressive, schizoid, and schizotypal), defined and based on DSM-III criteria. In this community sample, PD traits were measured in 1983 (mean age = 14), approximately two years later in 1985–86 (mean age =16), and six years after that in 1992 (mean age = 22). The CIC study contributed essential longitudinal data on descriptive developmental patterns for DSM-based PD traits into adulthood and helped to establish that PD traits could be reliably assessed over time in youth.

In this study, we describe dimensional traits of avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PDs; these six PDs were selected because they demonstrated the highest prevalence at the diagnosis level in the CIC study (Johnson et al., 2000). Avoidant and dependent PD have been associated with impaired psychosocial functioning in adolescence and adulthood (Bernstein et al., 1993; Crawford et al., 2005). Avoidant PD, characterized by social inhibition and hypersensitivity to negative evaluation, has been associated with negative childhood experiences (Eikenaes et al., 2015; Rettew et al., 2003; Waxman et al 2014). Dependent PD involves excessive neediness and clinginess beyond that which is developmentally normative; dependent PD traits are associated with unprotected sex and suicidality in adolescents (Johnson et al., 1999; Lavan & Johnson, 2002). Individuals with histrionic PD may demonstrate extreme emotionality and attention-seeking behavior. Emotional neglect in childhood has been linked to histrionic PD traits (Lobbestael et al., 2010), and histrionic PD has been significantly associated with obesity and symptoms of eating disorders in adolescents (Chen et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2006). Narcissistic PD traits, characterized by exaggerated self-appraisal and entitlement along with impaired empathy or intimacy, have been associated with aggression and delinquency in youth (Barry, Frick, & Killian, 2003; Barry, Frick, Adler, & Grafeman, 2007; Thomaes et al., 2008). Borderline PD (BPD), marked by instability in self-image and personal relationships, affective lability, and disinhibition, has been studied more often in youth samples than other PDs (Crowell et al., 2009; Skodol et al., 2002). Adolescents with BPD have poorer functioning and more comorbid psychopathology than those with other PDs (Chanen et al 2007; Chen et al., 2006). Also associated with substantial disability (Skodol, 2018), schizotypal PD is defined by cognitive and perceptual dysregulation, unusual beliefs and experiences, and interpersonal detachment. Schizotypal PD traits may begin to emerge during middle childhood and represent a prodrome for psychosis (Jones et al., 2015). Antisocial PD traits were not examined in the current study; the developmental trajectories of antisocial PD and its earlier manifestations (i.e., oppositional defiant/conduct disorder) have been previously detailed in multiple examinations (e.g., Cohen et al., 2005; Van Hulle et al., 2009; Lahey, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2003; Raine, 2018; Tuvblad et al., 2016).

Mean level changes in PD traits

Mean level change refers to the degree to which the average level of a trait in a population changes over time. In the CIC study, mean levels of all PD traits (e.g., avoidant, borderline, dependent, depressive, histrionic, narcissistic, paranoid, obsessive-compulsive, schizoid, and schizotypal) declined linearly through adolescence and young adulthood (Johnson et al., 2000). Other longitudinal work in community samples has found mean levels of borderline PD traits decreased over time in childhood (Crick et al., 2005) and adolescence (Bornovalova et al., 2009). In contrast, in a small outpatient sample of older adolescents aged 15 to 18, there was no change in trait levels of any PD (including borderline) over two years (Chanen et al., 2004).

Although to date, no study besides CIC has repeatedly assessed multiple forms of PD traits over time in children and adolescents, there has been much more work examining trajectories of normative personality traits in youth. Emerging dimensional classifications of personality traits conceptualize PD traits as existing on the same continuum with normal-range personality traits and functioning as extreme versions of normative traits (Shiner & Allan, 2018). Existing literature on normative development of personality traits can inform studies concerned with personality pathology in children and adolescents (Shiner, 2009; Shiner & Tackett, 2014). PDs are associated with low conscientiousness and agreeableness (Krueger et al., 2012; Samuel & Widiger, 2008). On average, individuals increase in conscientiousness and agreeableness as they mature from childhood to young adulthood (Roberts et al., 2006); although evidence suggests mean levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness decrease as individuals enter adolescence (DePauw, 2017; Shiner & Tackett, 2014).

Rank order stability in PD traits

Rank order stability refers to how individuals maintain their standing on a trait level compared to others in a population, over time. Thus we can assess if youth who are high on PD traits relative to their peers at one timepoint remain high relative to peers at subsequent timepoints. The CIC study and other relevant studies (e.g., Chanen et al., 2004; Venta et al., 2014; Vito et al., 1999) have shown moderate rank-order stability in PD trait levels across development. For example, in the CIC study, correlations between avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PD traits at baseline (1983) and two to three years later (1985–6) ranged from .29 (schizotypal) to .57 (narcissistic); overall, it appears that children and adolescents high in PD traits relative to their peers maintain that rank over time (Johnson et al., 2000). Similar to personality pathology traits, children display moderate stability in normative personality traits and rank-order stability increases with maturation (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000; Shiner & Tackett, 2014).

The present study

Recently, several experts have pointed out the need for replication of the CIC study and for establishing trajectory patterns of PD traits from earlier in childhood (e.g., Kongerslev et al., 2015; Newton-Howes, Clark, & Chanen, 2015). The present study built on the foundational knowledge set by the CIC study and delineated descriptive DSM-IV based PD trait patterns in a sample assessed across narrower time intervals and at younger ages than that represented in previous work to examine both mean-level change and rank-order stability over time. More closely spaced assessments in samples of children and adolescents more precisely describe trajectories in PD traits that occur across this broad developmental period from late childhood through late adolescence. The present study conducted baseline assessments of PD traits (avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal), beginning with children in 3rd, 6th and 9th grades who were followed at 18-month intervals for three years.

Whether mean level changes in dimensional personality pathology traits differ between boys and girls during development has yet to be definitively established. The CIC study did not find significant gender differences in PD trait trajectories from childhood through adolescence in a community setting (Johnson et al., 2000). Additionally, a small study of older adolescents found that changes in PD traits over two years did not differ by gender (Chanen et al., 2004). However, studies of the development of normative personality traits suggest that girls and boys may show differences in neuroticism, a trait associated with personality pathology (Shiner, 2015; Shiner, in press). The present study examined gender as moderator of PD trait trajectories over development from childhood to adolescence.

The primary aim of the present study was to delineate developmental patterns in personality pathology traits (avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal) across childhood and adolescence by mapping the trajectories of six DSM-IV based PD syndromes from ages 8 to 18. We evaluated both mean level changes in PD traits and the rank-order stability of PD traits over time. Our study extended the age range for the first assessment of PD traits downward to 8 years old and assessed PD traits in cohorts of 3rd, 6th and 9th graders over three years, using an accelerated longitudinal cohort design that allowed for a total of seven time points of assessment from ages 8 to 18. Given the lack of previous research on PD traits in children, we did not make a priori predictions about the specific trajectories of the six PD traits or the presence of gender differences in trajectories.

Method

Participants and procedure

This study used data from the Genes, Environment, and Mood (GEM) Study and included 675 youth and a parent recruited from public schools in the Denver and central New Jersey metro areas (for additional details on study, see Hankin et al., 2015). Participants were recruited based on grade in school in cohorts of 3rd (n = 205), 6th (n = 248), and 9th (n = 222) graders to form an accelerated longitudinal cohort design. Brief information letters were sent home directly to the participating school districts of families with a child in third, sixth, or ninth grades. Of the families to whom letters were sent, 1135 parents responded to the letter and called the laboratory for more information. Of the families who initially contacted the laboratory, 675 (59% participation rate) qualified as study participants. The remaining 460 (41%) were considered nonparticipants: 4 (1%) because the child had an autism spectrum disorder or low IQ; 13 (3%) were non–English-speaking; 330 (71%) declined after learning about the study’s requirements; and 113 (25%) were scheduled but did not arrive for assessment. Exclusion criteria included child autism spectrum disorder, psychosis, and the presence of intellectual or developmental disabilities.

The youth sample (56% female) was generally comparable to the ethnic and racial characteristics of the overall population of the United States, although there were relatively fewer Latina/o (12%) participants. Youth were 70% Caucasian, 12% African-American, 9% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 9% other/multiracial. The same parent (92% female) participated at all timepoints. The racial background of parents was 73% Caucasian, 11% African-American, 8% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 8% other/multiracial. At baseline, 76% of parents were married or cohabiting, 29% had completed “some college”, and 29% had finished “a four year degree”. Median annual family income was $86,500, and 18.3% of youth received free/reduced lunch. Inclusion criteria for participants included English fluency. Each parent visited the laboratory for an in-person, initial visit and provided informed written consent for their participation. Each child’s parent completed assessments of the child’s personality disorder traits at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months to yield 3 assessment points per individual grade cohort, or a total of 7 assessment points spanning ages 8–18. Participants were compensated monetarily at all assessments. The institutional review boards approved all procedures.

Measures

The Adolescent Personality Disorders Questionnaire (APD; Johnson et al., 2000) is an 81-item questionnaire to assess personality pathology traits in children and adolescents. The APD is a dimensional measure, derived from symptom counts of DSM-based PD diagnoses. In this version of the APD, items were selected to correspond with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Respondents are asked to rate how true each statement is for them on a 4-point Likert scale. Valid self-reports of PD traits may be difficult to obtain with children; parents and other informants may more useful reporters of personality pathology in youth (Tackett et al., 2010; 2014). The CIC study combined both youth and parent reports in the assessment of PD traits. For the current study, parent report was assessed at all time points, and subscales for the six PDs were calculated by summing scores from the appropriate items. The APD subscales have demonstrated acceptable reliability and convergent and prospective validity in youth samples (Crawford et al., 2005, Johnson et al., 1999). Across timepoints of the current study, internal consistency for the avoidant subscale ranged from .85 to .88, for the dependent subscale from .80 to .83, for the histrionic subscale from .84 to .88, for the narcissistic subscale from .85 to .89, for the borderline subscale from .85 to .90, and for the schizotypal subscale from .64 to .70.

Analytic plan

To estimate mean-level trajectories separately for each PD, latent growth curve modeling (LGCM) analyses were conducted in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to handle missing data. First, we fit unconditional means (no-growth), linear growth, and quadratic growth models for the traits of each PD. In accordance with the accelerated longitudinal cohort design (Duncan et al., 1996), cohort equality constraints were set for the means of the intercept (and slope/s), variances for the intercept (and slope/s), covariances between the intercept and slope (for linear and quadratic models), and residual variances for timepoints where cohorts overlapped (e.g., 36 month assessment for 3rd graders/baseline assessment for 6th graders). On the best fitting model (no-growth, linear, or quadratic) for each set of PD traits, gender was included as a covariate and regressed on the intercept (and slope/s) of the model.

“Good fit” for models was defined as RMSEA as less than or equal to .06, confirmatory fit index (CFI) greater than or equal to .95 and SRMR less than or equal to .08. “Acceptable fit” was defined as RMSEA less than or equal to .08, and CFI greater than or equal to .90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). If no-growth, linear, or quadratic models for a given PD had comparable model fit, models were compared to each other on Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) in order to determine the best fitting, acceptable model for each PD trait trajectory.

Accelerated longitudinal cohort designs assume that data sampled from adjacent age cohorts over time-limited longitudinal intervals can be linked to approximate a single, continuous growth curve (Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1996). Creating an accelerated longitudinal cohort model for each PD (avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits) treats the cohorts of 3rd, 6th and 9th graders as if they were sampled from a common population over 7 assessment time points spanning ages 8–18. As described in Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker (2006), fit statistics were used to assess if the accelerated longitudinal cohort model provided an adequate fit to the data. Acceptable fit for the accelerated longitudinal model supports that there is sufficient convergence across cohorts to specify a common growth trajectory for the full sample. If model fit statistics for the no-growth, linear growth, and quadratic growth models of a PD trait were poor using the accelerated longitudinal cohort design, then the trajectories of growth were modeled for the 3rd, 6th, and 9th grade cohorts independently, relaxing equality constraints so that all model parameters were estimated separately for each cohort.

Lastly, rank-order stability was assessed by computing Pearson correlations between trait levels at baseline, 18 month assessment, and 36 month assessment, separately for each PD (avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal).

Results

Descriptive analyses

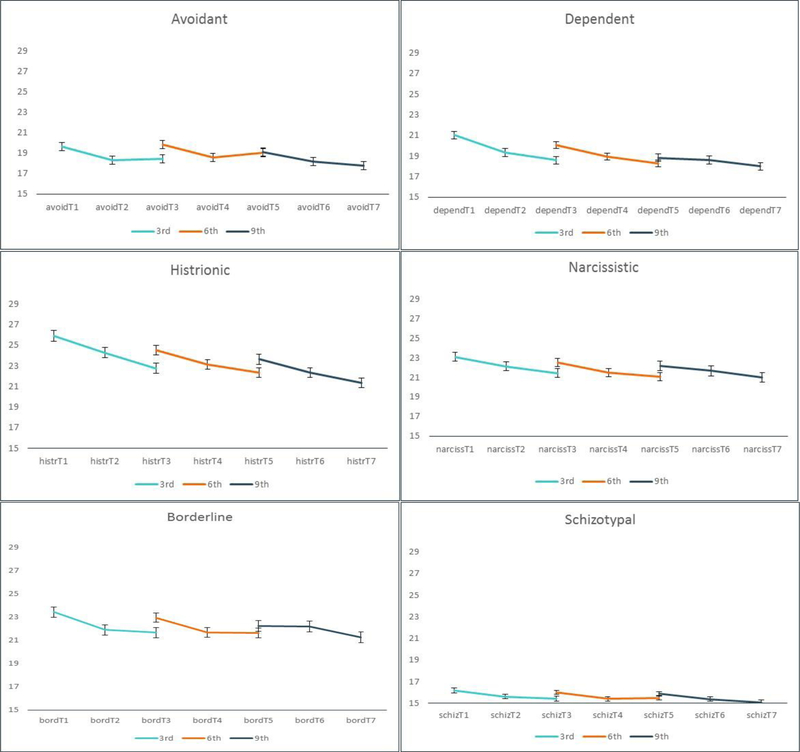

Study and analytic plan were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/sv5x3/). Descriptive statistics for parent report of PD traits are reported by gender in Table 1. Descriptive plots of PD trait means of each grade cohort across assessments are illustrated for parent report (Figure 1). Correlations among primary variables are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for parent report of PD traits by gender

| Time 1 | 3rd M(SD) | 6th M(SD) | 3rd M(SD) | 6th M(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant (range 12–36) | 19.52(5.71) | - | 19.78(5.29) | - |

| Dependent (range 12–37) | 20.60(5.04) | - | 21.51(5.17) | - |

| Histrionic (range 13–44) | 25.80(6.34) | - | 24.40(6.37) | - |

| Narcissistic (range 14–37) | 26.92(5.91) | - | 25.79(6.96) | - |

| Borderline (range 17–49) | 29.34(8.00) | - | 26.61(7.66) | - |

| Schizotypal (range 13–30) | 16.07(3.33) | - | 16.34(3.11) | - |

| Time 2 | ||||

| Avoidant (range 12–42) | 18.36(5.26) | - | 18.29(4.69) | - |

| Dependent (range 12–45) | 18.84(5.25) | - | 19.87(5.01) | - |

| Histrionic (range 13–52) | 23.73(6.88) | - | 23.08(6.38) | - |

| Narcissistic (range 14–53) | 24.92(6.99) | - | 24.16(6.20) | - |

| Borderline (range 17–47) | 24.94(6.69) | - | 23.52(6.99) | - |

| Schizotypal (range 13–38) | 15.45(3.62) | - | 15.83(2.74) | - |

| Time 3 | ||||

| Avoidant (range 12–41) | 18.61(5.80) | 20.06(5.29) | 18.28(5.58) | 19.49(6.24) |

| Dependent (range 12–44) | 18.04(4.81) | 20.56(4.86) | 19.20(4.93) | 19.28(4.40) |

| Histrionic (range 13–46) | 25.20(6.04) | 25.62(6.77) | 23.60(5.24) | 25.17(5.96) |

| Narcissistic (range 14–45) | 24.92(7.29) | 24.89(5.79) | 24.15(5.52) | 25.96(6.66) |

| Borderline (range 17–45) | 25.54(7.66) | 26.78(7.29) | 24.16(6.55) | 27.16(7.63) |

| Schizotypal (range 13–31) | 15.13(2.12) | 16.13(3.02) | 15.74(2.95) | 15.82(2.32) |

| Time 4 | 6th M(SD) | 9th M(SD) | 6th M(SD) | 9th M(SD) |

| Avoidant (range 12–40) | 18.73(5.73) | - | 18.34(5.42) | - |

| Dependent (range 12–35) | 19.36(5.29) | - | 18.24(4.59) | - |

| Histrionic (range 13–43) | 26.50(6.78) | - | 25.67(6.05) | - |

| Narcissistic (range 14–40) | 25.08(6.67) | - | 26.55(6.13) | - |

| Borderline (range 17–51) | 26.47(7.73) | - | 25.02(7.15) | - |

| Schizotypal (range 13–28) | 15.61(3.11) | - | 15.12(2.09) | - |

| Time 5 | ||||

| Avoidant (range 12–35) | 19.49(5.87) | 18.51(5.23) | 18.35(5.71) | 19.82(5.70) |

| Dependent (range 12–39) | 19.01(5.28) | 18.35(4.80) | 17.22(3.67) | 19.46(5.49) |

| Histrionic (range 13–47) | 25.81(6.02) | 26.70(6.00) | 24.90(6.29) | 26.36(5.64) |

| Narcissistic (range 14–48) | 24.03(5.96) | 26.47(6.28) | 25.87(7.04) | 27.98(6.44) |

| Borderline (range 17–47) | 26.69(7.58) | 29.12(8.27) | 23.68(5.30) | 27.13(7.60) |

| Schizotypal (range 13–31) | 15.78(2.90) | 15.47(2.83) | 15.13(2.31) | 16.44(3.49) |

| Time 6 | ||||

| Avoidant (range 12–38) | - | 17.80(5.87) | - | 18.71(6.43) |

| Dependent (range 12–33) | - | 18.19(5.13) | - | 19.16(5.28) |

| Histrionic (range 13–47) | - | 26.29(6.40) | - | 26.72(5.90) |

| Narcissistic (range 14–45) | - | 25.39(7.13) | - | 28.65(7.06) |

| Borderline (range 17–56) | - | 27.57(8.68) | - | 27.85(8.67) |

| Schizotypal (range 13–30) | - | 15.17(2.14) | - | 15.70(3.25) |

| Time 7 | ||||

| Avoidant (range 12–39) | - | 17.55(5.40) | - | 18.10(5.53) |

| Dependent (range 12–32) | - | 17.63(4.57) | - | 18.45(5.06) |

| Histrionic (range 13–39) | - | 25.13(6.46) | - | 24.34(4.97) |

| Narcissistic (range 14–43) | - | 23.76(7.17) | - | 26.49(7.99) |

| Borderline (range 17–44) | - | 25.91(8.30) | - | 25.19(7.48) |

| Schizotypal (range 13–24) | - | 14.73(2.10) | - | 15.59(2.79) |

Figure 1.

Parent report of PD trait means for each grade cohort across each timepoint. Bars represent plus and minus one standard error.

Table 2.

Correlations of PD traits at each timepoint.

| TIME 1 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .61 | .39 | .46 | .53 | .41 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .54 | .46 | .56 | .35 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .64 | .59 | .24 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .55 | .35 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .55 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 2 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .76 | .53 | .61 | .69 | .69 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .58 | .57 | .65 | .63 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .73 | .64 | .41 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .73 | .50 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .60 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 3 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .66 | .32 | .41 | .58 | .55 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .51 | .47 | .60 | .54 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .65 | .61 | .29 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .64 | .42 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .57 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 4 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .67 | .43 | .53 | .62 | .62 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .63 | .60 | .65 | .58 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .67 | .64 | .48 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .66 | .58 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .72 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 5 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .65 | .31 | .39 | .57 | .51 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .54 | .46 | .66 | .56 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .68 | .64 | .37 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .63 | .45 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .61 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 6 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .75 | .46 | .57 | .67 | .61 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .58 | .63 | .72 | .53 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .75 | .70 | .46 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .77 | .54 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .74 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

| TIME 7 | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1 | Avoidant | -- | .69 | .48 | .57 | .62 | .57 |

| 2 | Dependent | -- | .64 | .60 | .67 | .64 | |

| 3 | Histrionic | -- | .78 | .73 | .55 | ||

| 4 | Narcissistic | -- | .78 | .61 | |||

| 5 | Borderline | -- | .72 | ||||

| 6 | Schizotypal | -- | |||||

PD trait mean-level trajectories

In the current study, fit statistics indicated that the accelerated longitudinal cohort model for each of the six PD traits was an acceptable or good fit to the data. As stated in Duncan et al., 2006, “such results justify the use of a cohort-sequential model to approximate a true longitudinal curve in these data and suggest that the three cohorts were sampled from the same true longitudinal population” (p. 76). Using the accelerated longitudinal cohort design, linear models of avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PD traits by parent report each demonstrated acceptable or good fit statistics (Table 3) and fit better than their no-growth counterparts (Table S1). In the avoidant and schizotypal models, linear slope variance was constrained to zero to allow convergence. When the quadratic model of growth was tested for avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits, the quadratic slope was non-significant, and fit statistics were not better than for the linear models (Table S1). For all six sets of PD traits, the linear model was therefore chosen as the best fitting and most parsimonious model. When gender was added as a covariate to the accelerated longitudinal cohort design, fit statistics for the best fitting (linear) models for all PD traits models improved or stayed stable; however, there were no significant gender differences in intercept or slope in any of these models. Fit statistics for best fitting models of PD traits using parent report with and without gender as a covariate are listed in Table 3 and model parameters for the best fitting models are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Model fit for best fitting latent growth models of PD traits.

| Model | χ2 (df) | CFI | RMSEA [90% CI] | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Gender as a Covariate | |||||||

| Avoidant | Linear growth1 | 34.28 (25) | .99 | .04 [.00, .07] | .08 | 10519.13 | 10533.91 |

| Dependent | Linear growth | 59.28 (23) | .95 | .08 [.06, .11] | .12 | 10000.81 | 10018.26 |

| Histrionic | Linear growth | 47.63 (23) | .97 | .07 [.04, .10] | .10 | 10773.00 | 10790.34 |

| Narcissistic | Linear growth | 30.03 (23) | .99 | .04 [.00, .07] | .07 | 10691.49 | 10708.83 |

| Borderline | Linear growth | 69.39 (23) | .95 | .10 [.07, .12] | .11 | 10533.91 | 10551.25 |

| Schizotypal | Linear growth1 | 51.17 (25) | .94 | .07 [.04,. 10] | .16 | 8285.66 | 8300.41 |

| With Gender as a Covariate | |||||||

| Avoidant | Linear growth1 | 46.28 (37) | .99 | .03 [.00, .06] | .08 | 11509.35 | 11532.30 |

| Dependent | Linear growth | 76.05 (35) | .95 | .07 [.05, .09] | .11 | 10991.08 | 11016.73 |

| Histrionic | Linear growth | 56.87 (35) | .98 | .05 [.03, .08] | .09 | 11748.80 | 11774.26 |

| Narcissistic | Linear growth | 38.85 (35) | .99 | .02 [.00, .05] | .07 | 11669.09 | 11694.54 |

| Borderline | Linear growth | 82.00 (35) | .96 | .08 [.06, .10] | .10 | 11512.66 | 11538.12 |

| Schizotypal | Linear growth1 | 67.10 (37) | .94 | .06 [.04, .08] | .14 | 9275.93 | 9298.88 |

Note:

slope variance constrained to zero.

AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion (sample size adjusted); CFI = comparative fit index; CI = confidence interval; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual. “Good fit” for models was defined as RMSEA as less than or equal to .06, confirmatory fit index (CFI) greater than or equal to .95 and SRMR less than or equal to .08. “Acceptable fit” was defined as RMSEA less than or equal to .08, and CFI greater than or equal to .90.

Table 4.

Mean and variance estimates for best-fitting models of PD traits

| Mean (b) | SE (b) | Mean (β) | SE (β) | Variance (b) | SE (b) | Covariance (b) | SE (b) | Covariance (β) | SE (β) | Cohen’s d ΔPD traits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant Intercept | 19.01* | 0.39 | 4.23* | 0.17 | 20.16* | 1.39 | - | - | - | - | 0.34 |

| Avoidant Slope1 | −0.93 | 0.65 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Dependent Intercept | 20.47* | 0.35 | 4.88* | 0.37 | 17.58* | 2.57 | −1.19 | 5.07 | −0.25 | 0.36 | 0.62 |

| Dependent Slope | −3.25* | 0.58 | −2.86* | 11.35 | 1.29 | 10.19 | −1.19 | 5.07 | −0.25 | 0.36 | |

| Histrionic Intercept | 25.30* | 0.48 | 4.35* | 0.30 | 33.86* | 4.42 | −6.27 | 8.78 | −0.24 | 0.23 | 0.69 |

| Histrionic Slope | −4.86* | 0.78 | −1.09* | 0.53 | 19.96 | 18.42 | −6.27 | 8.78 | −0.24 | 0.23 | |

| Narcissistic Intercept | 22.69* | 0.44 | 4.55* | 0.36 | 24.88* | 3.76 | −3.81 | 7.82 | −0.14 | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| Narcissistic Slope | −2.01* | 0.75 | −0.36* | 0.17 | 30.61 | 17.06 | −3.81 | 7.82 | −0.14 | 0.24 | |

| Borderline Intercept | 22.92* | 0.44 | 4.26* | 0.30 | 28.95* | 3.86 | −10.69 | 7.43 | −0.36 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Borderline Slope | −1.89* | 0.73 | −0.35* | 0.16 | 29.70 | 15.42 | −10.69 | 7.43 | −0.36 | 0.15 | |

| Schizotypal Intercept | 15.84* | 0.21 | 7.42* | 0.30 | 4.56* | 0.35 | - | - | - | - | 0.38 |

| Schizotypal Slope1 | −0.68 * | 0.34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note:

slope variance constrained to zero.

Cohen’s d values compare mean PD trait levels at the first timepoint and the last timepoint.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the change in mean PD traits from the first timepoint to the last timepoint ranged from .3 to .7 (Table 4). The standard interpretation would categorize the changes in dependent and histrionic traits as medium effects, and the changes in avoidant, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits as small effects (Cohen, 1998).

Avoidant PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 19.01, SD = 0.39) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −0.93, SD = 0.54); this supported a decline in avoidant traits over time. Linear slope variance was constrained to zero to allow convergence.

Dependent PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 20.47, SD = 0.35) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −3.25, SD = 0.58) with non-significant variance; this supported a decline in dependent traits over time. There was a non-significant covariance between the intercept and slope (M = −1.19, SD = 5.07).

Histrionic PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 25.30, SD = 0.48) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −4.86, SD = 0.78) with non-significant variance; this supported a decline in histrionic traits over time. There was a non-significant covariance between the intercept and slope (M = −6.27, SD = 8.78).

Narcissistic PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 22.69, SD = 0.44) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −2.01, SD = 0.75) with non-significant variance; this supported a decline in narcissistic traits over time. There was a non-significant covariance between the intercept and slope (M = −3.81, SD = 7.82).

Borderline PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 22.92, SD = 0.44) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −1.89, SD = 0.73) with non-significant variance; this supported a decline in borderline traits over time. There was a non-significant covariance between the intercept and slope (M = −10.69, SD = 7.43).

Schizotypal PD traits.

For the best-fitting linear model (Table 4), there was a significant intercept (M = 15.84, SD = 0.21) with significant variance and negative slope (M = −0.68, SD = 0.34); this supported a decline in schizotypal traits over time. Linear slope variance was constrained to zero to allow convergence.

Rank order stability in PD traits

Traits for each PD at baseline were significantly correlated with the same PD traits at 18 months and at 36 months, and traits for each PD at 18 months were significantly correlated with the same PD traits at 36 months (Table 5). Correlations between the same PD traits at baseline and 18 months ranged from 0.49 for schizotypal PD traits to 0.72 for both histrionic and borderline PD traits. Correlations between the same PD trait levels at 18 and 36 months ranged from 0.59 for schizotypal PD traits to 0.77 for histrionic PD traits. Correlations between the same PD traits at baseline and 36 months ranged from 0.44 for schizotypal PD traits to 0.69 for histrionic PD traits.

Table 5.

Rank order stability at baseline (Time 1), 18 months (Time 2), and 36 months (Time 3).

| Traits | Time 1 - Time 2 | Time 1 - Time 2 | Time 1 - Time 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant | .63 | .67 | .56 |

| Dependent | .69 | .73 | .61 |

| Histrionic | .72 | .77 | .69 |

| Narcissistic | .69 | .73 | .66 |

| Borderline | .72 | .74 | .60 |

| Schizotypal | .49 | .59 | .44 |

Discussion

Personality disorder (PD) traits are prevalent prior to adulthood; however, developmental patterns in PD traits from childhood through adolescence have not been clearly delineated. Using an accelerated longitudinal cohort design, the current study examined the mean-level trajectories and rank-order stability patterns of six DSM-IV based PD syndromes over time. Results showed that mean-levels traits of all six PD syndromes declined over ages 8 to 18, and rank-order stability was moderate to high. According to parent report, avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PD traits of their children all declined linearly over ages 8 to 18. In addition, the current study did not find strong or systematic gender differences in the slopes of any of the six PD trait trajectories. Parents reported that boys and girls started out with comparable levels of avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PD traits at age 8, and declined similarly in all PD traits through age 18. Effect sizes for the mean-level changes in dependent and histrionic trait levels from the first to the last timepoint were medium; whereas, those for avoidant, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits were small.

The present study augments existing knowledge on developmental trajectories of parent reported DSM-based PD traits from childhood through late adolescence. The reported declines in all PD traits and lack of significant gender differences in trait trajectories from ages 8 to 18 align with previous work in a community setting assessing DSM-IV PD traits. In the CIC study, Johnson and colleagues (2000) found declines in all PD trait levels across childhood and adolescence with no significant gender differences in trait trajectories. In the CIC study, the overall decline in mean PD trait levels from childhood to young adulthood was estimated to be of small effect size (r = −.32) (Johnson et al., 2000), which was similar to the effect sizes found in the current study. Others have also found borderline PD traits to decline from 4th to 6th grade and from mid adolescence to young adulthood (Crick et al., 2005; Bornovalova et al., 2009). Moreover, parents’ report of declines in PD traits in their children over time are congruent with studies of normative personality trait development that find increases in emotional stability during adolescence and young adulthood (Donnellan & Robins, 2009; Morey & Hopwood, 2013; Roberts et al. 2006).

We found rank-order stability of the six PD traits over development to be stronger than found in the CIC; Johnson et al., (2000) found low to moderate stability on PD traits over the first two years as well as the subsequent six years of the study. In the CIC study, correlations between avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal PD traits at baseline (1983) and two to three years later (1985–6) ranged from .29 (schizotypal) to .57 (narcissistic). We found moderate to high stability for the six PD traits, which reflects that found in more recent studies of personality pathology (e.g., .47 to .58, Crick et al., 2005; .64 to .72, De Clercq, Van Leeuwen et al., 2009) and normal range personality traits in children and adolescents (e.g., .44 to .72, Ferguson, 2010; .43 to .72, Klimstra et al., 2009).

Adolescence has been conceived of as a period of heightened vulnerability to psychopathology broadly (e.g., Paus et al., 2008). Our results showing mean-level declines in parent reports of PD traits may seem to contradict the accepted notion that common psychiatric disorders increase in prevalence from childhood through adolescence. In addition, children appear to decrease in traits of conscientiousness and agreeableness (both associated with PDs, e.g., Samuel & Widiger, 2008) in the transition from childhood to adolescence (DePauw, 2016; Shiner & Tackett, 2014). The current study found that levels of mean PD traits declined during childhood and adolescence, which is congruent with earlier work; age was inversely associated with PD trait levels in the CIC study and findings were consistent with “an essentially linear decline from age 9 to 27” (Cohen et al., 2005, p. 469). However, we also did not examine PD diagnoses during the same time frame and evidence suggests that rates of PD diagnoses are at their peak during early adolescence; indeed, the CIC study found that PD disorders were most prevalent at ages 12–13 (Bernstein et al., 1993; Cohen et al., 2005). As significant distress or impairment are needed for a diagnosis of PD, it may be that PD diagnoses peak in early adolescence because distress or impairment due to PD traits is higher during this time.

A decline in PD traits may also represent normative maturation and socialization processes that proceed somewhat linearly throughout childhood and adolescence. For example, dependent PD traits may diminish as youth become more and more developmentally ready to assume responsibility for their own needs and less fearful of separation from their parents. Although declines in PD traits represent developmentally normative maturation, higher levels of PD traits than same-age are worthy of attention by researchers and clinicians. For instance, PD traits in early adolescence predict psychosocial disability in adulthood (Winograd, Cohen, & Chen, 2008). Higher levels of PD traits in childhood may also foreshadow lifelong difficulties with personality pathology. The current study and earlier work have found at least moderate stability of personality pathology from childhood through adulthood (e.g., Cohen et al., 2005; Chanen et al., 2004; Venta et al., 2014). Results suggest that youth who are high on PD traits relative to their same–age peers at one timepoint will remain high relative to peers throughout development and into adulthood. Some individuals may not only maintain higher levels of PD traits but actually increase in personality pathology during childhood and adolescence; 21% in the CIC study showed increases in PD traits (Johnson et al., 2000). Not experiencing a normative decline in PD traits and maintaining higher levels PD traits may predict clinical levels of personality pathology in adulthood. Individuals who show relatively high levels of PD at a young age may be good candidates for indicated prevention programs (Chanen & McCutcheon, 2013). Early intervention with youth divergent from normative PD trait trajectories may prevent the later onset of severe personality pathology and psychosocial disability (Chanen & Thompson, 2018).

Our assessment of PD traits (Adolescent Personality Disorders Questionnaire, APD; Johnson et al., 2000) has been validated in youth samples (beginning at age 9; Cohen et al., 2005) and allows us to directly compare findings with the CIC study (Cohen et al., 2005). The APD is a dimensional measure; however, its items are derived from symptoms of categorical DSM-IV PD diagnoses. Although the DSM-5 (DSM-5-II; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) retains the ten categorical PD syndromes that appear in the DSM-IV, significant evidence does not support this traditional categorical approach (Sharp et al., 2015; Widiger, Livesley, & Clark, 2009). However, DSM-5 also includes (Section III, Emerging Measures and Models; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) an alternative dimensional-categorical hybrid structure of PD traits that considers impairment in self and interpersonal functioning and contains five broad areas of maladaptive personality traits (e.g., disinhibition, antagonism) as well as 6 PD types (borderline, obsessive-compulsive, avoidant schizotypal, antisocial, narcissistic). Further, the APD was adapted directly from measures used with adults and future research may want to incorporate measures based on the dimensional trait perspective of personality pathology, such as those developed “from the bottom up” specifically for use with children and adolescents (e.g., De Clercq et al., 2006; Tackett, 2013). Dimensional trait measures drawing from the literature of normative personality structure and directly developed for use with children correspond well with personality pathology in adults (DIPSI; De Clercq et al., 2006; De Clercq, De Fruyt et al., 2009). As there is still research needed to definitely establish the exact developmental course of PD traits, we cannot yet determine if the measurement occasions of our study are ideal for the true rate of change of PD traits in this population. Future work could examine the alignment between intervals of assessment and the expected changes in PD traits seen across childhood and adolescence. Measurement invariance analyses using dimensional “bottom up” measures would also support that the observed change in assessment measures reflects the true developmental course of PD.

The present study delineated developmental trajectories of personality pathology traits by examining mean-level change and rank-order stability of traits of six common DSM-based PDs from childhood through late adolescence. According to parent report, mean levels of avoidant, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, and schizotypal traits all declined linearly for both genders and the traits of each PD also demonstrated moderate to high rank-order stability. The declines in PD traits, lack of significant gender differences in trait trajectories, and level of stability align with previous longitudinal work evaluating PD traits in youth and congruent with studies that find increases in adaptive personality traits over development. Results may help inform future longitudinal developmental studies using dimensional trait measures directly developed for use with youth. A decline in PD traits throughout childhood and adolescence may represent normative maturation and developmental processes. Early intervention with youth divergent from normative PD trait trajectories may prevent the later onset of clinical levels of personality pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health to Benjamin L Hankin, R01MH077195, R01MH105501, R21MH102210, R01MH109662, and to Jami F. Young, R01MH077178.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Elissa J. Hamlat, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Jami F. Young, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Benjamin L. Hankin, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CT, Frick PJ, & Killian AL (2003). The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(1), 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CT, Frick PJ, Adler KK, & Grafeman SJ (2007). The predictive utility of narcissism among children and adolescents: Evidence for a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(4), 508–521. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, & Shinsato L (1993). Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1237–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, & McGue M (2009). Stability, change, and heritability of borderline personality disorder traits from adolescence to adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Development and Psychopathology, 21(4), 1335–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, & McCutcheon L (2013). Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: Current status and recent evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(s54), s24–s29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, & Thompson KN (2018). Early intervention for personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Allot KA, Clarkson V, & Yuen HP (2004). Two-year stability of personality disorder in older adolescent outpatients. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(6), 526–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, Crawford TN, Kasen S, Johnson JG, & Berenson K (2006). Relative impact of young adult personality disorders on subsequent quality of life: findings of a community-based longitudinal study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(5), 510–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Huang Y, Kasen S, Skodol A, Cohen P, & Chen H (2015). Impact of adolescent personality disorders on obesity 17 years later. Psychosomatic Medicine, 77(8), 921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Crawford TN, Johnson JG, & Kasen S (2005). The Children in the Community Study of developmental course of personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(5), 466–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TN, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Kasen S, First MB, Gordon K, & Brook JS (2005). Self-reported personality disorder in the children in the community sample: convergent and prospective validity in late adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(1), 30–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Murray–Close D, & Woods K (2005). Borderline personality features in childhood: A short-term longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 17(4), 1051–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, & Linehan MM (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 495–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Van Leeuwen K, & Mervielde I (2006). The structure of maladaptive personality traits in childhood: A step toward an integrative developmental perspective for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(4), 639–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, & Widiger TA (2009). Integrating a developmental perspective in dimensional models of personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, Van Leeuwen K, Van Den Noortgate W, De Bolle M, & De Fruyt F (2009). Childhood personality pathology: Dimensional stability and change. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 853–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw S (2017). Childhood personality and temperament In Widiger T (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Conkey LC, & Whalen DJ (2018). Recent advances in understanding physical health problems in personality disorders. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, & Robins RW (2009). The development of personality across the lifespan In Corr P & Matthews G (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 191–204). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, & Hops H (1996). Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods, 1(3), 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, & Strycker LA (2006). Alcohol use from ages 9 to 16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81(1), 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikenaes I, Egeland J, Hummelen B, & Wilberg T (2015). Avoidant personality disorder versus social phobia: The significance of childhood neglect. PloS one, 10(3), e0122846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JRZ, Smolen A, Jenness JL, Gulley LD, … Oppenheimer CW (2015). Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Cohen P, Kasen S, Ae S, Hamagami F, Js B, … Brook JS (2000). Age-related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(35), 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, & Brook JS (2006). Personality disorder traits evident by early adulthood and risk for eating and weight problems during middle adulthood. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(3), 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Kasen S, & Brook JS (1999). Personality disorders in adolescence and risk of major mental disorders and suicidality during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(9), 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, Seal ML, Pantelis C, & Tonge B (2015). The Melbourne assessment of Schizotypy in kids: A useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. BioMed Research International, doi: 10.1155/2015/635732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, Hale III WW, Raaijmakers QA, Branje SJ, & Meeus WH (2009). Maturation of personality in adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 898–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongerslev MT, Chanen AM, & Simonsen E (2015). Personality disorder in childhood and adolescence comes of age: A review of the current evidence and prospects for future research. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, 3(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Derringer J, Markon KE, Watson D, & Skodol AE (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1879–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, & Caspi A (Eds.). (2003). Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavan H, & Johnson JG (2002). The association between axis I and II psychiatric symptoms and high-risk sexual behavior during adolescence. Journal of Personality Disorders, 16(1), 73–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbestael J, Arntz A, & Bernstein DP (2010). Disentangling the relationship between different types of childhood maltreatment and personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(3), 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, & Hopwood CJ (2013). Stability and change in personality disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 499–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7 ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Howes G, Clark LA, & Chanen A (2015). Personality disorder across the life course. The Lancet, 385(9969), 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, & Giedd JN (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SE, Berk M, Chanen AM, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Brennan-Olsen SL, Pasco JA, & Williams LJ (2016). Population prevalence of personality disorder and associations with physical health comorbidities and health care service utilization: A review. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(2), 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A (2018). Antisocial personality as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Annual review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 259–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettew DC, Zanarini MC, Yen S, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Shea MT, … & Gunderson JG (2003). Childhood antecedents of avoidant personality disorder: A retrospective study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(9), 1122–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, & DelVecchio WF (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126(1), 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, & Viechtbauer W (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, & Widiger TA (2008). A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(8), 1326–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Wright AGC, Christopher Fowler J, Christopher Frueh B, Allen JG, Oldham J, & Clark LA (2015). The structure of personality pathology: Both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(2), 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, & Allen TA (2018). Developmental psychopathology In Livesley J & Larstone R (Eds.), Handbook of Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment (2nd ed., pp. 309–323). New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, & Tackett JL (2014). Personality disorders in children and adolescents In Mash EJ, & Barkley RA (Eds.), Child Psychopathology (3rd ed., pp. 848–896). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL (2009). The development of personality disorders: Perspectives from normal personality development in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 715–734.sh [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE (2018). Impact of personality pathology on psychosocial functioning. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, … & Sanislow CA (2002). Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(2), 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, … Stout RL (2005). The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS): Overview and Implications. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(5), 487–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL (2010). Measurement and assessment of child and adolescent personality pathology: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 463–466. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Balsis S, Oltmanns TF, & Krueger RF (2009). A unifying perspective on personality pathology across the life span: Developmental considerations for the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 687–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Kushner SC, De Fruyt F, & Mervielde I (2013). Delineating personality traits in childhood and adolescence: Associations across measures, temperament, and behavioral problems. Assessment, 20(6), 738–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, Stegge H, & Olthof T (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: narcissism, self‐esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development, 79(6), 1792–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuvblad C, Wang P, Bezdjian S, Raine A, & Baker LA (2016). Psychopathic personality development from ages 9 to 18: Genes and environment. Development and psychopathology, 28(1), 27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle CA, Waldman ID, D’Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Rathouz PJ, & Lahey BB (2009). Developmental structure of genetic influences on antisocial behavior across childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 711–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venta A, Herzhoff K, Cohen P, & Sharp C (2014). The longitudinal course of borderline personality disorder in youth In Handbook of Borderline Personality Disorder in Children and Adolescents (pp. 229–245). Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Vito ED, Ladame F, & Orlandini A (1999). Adolescence and personality disorders: Current perspectives on a controversial problem In Derksen J, Maffei C, & Groen H (Eds.), Treatment of Personality Disorders (pp. 77–95). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, & Clark LA (2009). An integrative dimensional classification of personality disorder. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd G, Cohen P, & Chen H (2008). Adolescent borderline symptoms in the community: Prognosis for functioning over 20 years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(9), 933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.