Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Desmoid tumors (or aggressive fibromatosis) are locally infiltrative connective-tissue tumors that can arise in any anatomic location; they can be asymptomatic, or they can result in pain, deformity, swelling, and loss of mobility and/or threaten visceral organs with bowel perforation, hydronephrosis, neurovascular damage, and other complications. Existing clinical trial endpoints such as the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) and progression-free survival are inadequate in capturing treatment efficacy. This study was designed to develop a novel clinical trial endpoint by capturing patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

METHODS:

Following best practices in qualitative methodology, this study used concept elicitation (CE) interviews to explore desmoid patients’ perspectives on key disease-related symptoms and impacts. Qualitative analysis was performed to determine the relative frequency and disturbance of symptoms and impacts as well as other characteristics of these concepts. A draft PRO scale was then developed and tested with cognitive interviewing. Information from the interviews was subsequently incorporated into the refined PRO scale.

RESULTS:

CE interviews with desmoid patients (n = 31) helped to identify salient concepts and led to a draft scale that included symptom and impact scales. Cognitive interviews were completed with additional patients (n = 15) across 3 phases. Patient input was used to refine instructions, revise and/or remove items, and modify the response scale. This resulted in an 11-item symptom scale and a 17-item impact scale.

CONCLUSIONS:

This is the first disease-specific PRO instrument developed for desmoid tumors. The instrument is available as an exploratory endpoint in clinical trials. This study highlights the feasibility and challenges of developing PRO instruments for rare diseases.

Keywords: clinical outcome assessments, drug development tool, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) patient-reported outcome (PRO) guidance, neoplasms, patient-centered outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Desmoid tumors (DTs) are locally aggressive connective-tissue sarcomas that have high morbidity and low mortality.1 These are rare or orphan cancers with an annual incidence of 1000 patients in the United States. The disease predominantly affects young adults and can arise in any anatomic location but favors the extremities, joints, and abdomen. Depending on its location, patients can present with pain, a loss of range of movement or immobility, bowel obstructions and/or perforations, hydronephrosis, and a host of other symptoms. Treatment for desmoid tumors can include a wait-and-watch strategy, surgery, ablation, systemic therapies (cytotoxic, hormonal, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors), and/or radiation in appropriately selected patients.2 Prospectively conducted clinical trials in DTs use standard endpoints such as Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) response rates and progression-free survival to measure treatment efficacy.3 These surrogate endpoints for overall survival may not be appropriate for a disease with low mortality and importantly fail to capture whether treatments truly improve symptoms and/or affect daily living. To date, there are limited data on the qualitative impact among patients affected by DTs.4,5

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are direct measurements of patient experiences without any filtration or interpretation by a clinician or health care worker.6–8 Measuring a patient’s symptoms and function is an additional dimension or endpoint that qualifies traditional endpoints such as response rates and/or overall survival. PRO measures enable patients, families, and clinicians to make rational, transparent, and patient-centered decisions weighing the impact of treatments on survival, quality of life, side effects, and financial burdens. The value of integrating PROs for symptom monitoring was recently demonstrated in a large, randomized trial of various chemotherapies, which showed significant improvements in quality of life and overall survival in comparison with the standard of care.9,10 Similarly, integration of electronic PROs into the clinic for the routine management of patients is feasible and appears to improve the quality of care for patients and physician satisfaction.11 Although there has been a significant charge to incorporate PROs into routine care and clinical practice,7,9,10 the capture of this subjective information has been particularly challenging in oncology for a multitude of reasons.12

We sought to prospectively develop a novel regulatory and clinical trial endpoint to characterize the subjective experience in patients with DTs, an ultrarare cancer. Although a recent review indicated the need for a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) tool for patients with DTs,13 an important step in the regulatory context is to ensure that the PRO measure is uniquely developed for DTs to complement existing HRQOL instruments such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30,14 the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System,15 and the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory,16 which are not specific to a disease or condition. We sought to develop a PRO tool that captures desmoid-related symptoms and impacts in accordance with the 2009 guidance for industry from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling.17

Therefore, the objectives of the current study were 2-fold. The first objective was to prospectively explore and understand the symptoms of adult patients living with DTs, their experience with treatment, and the impact of the disease on their lives via concept elicitation (CE).18 The second objective was to conduct cognitive interviews (CIs)19,20 in a second cohort of DT patients to assess patients’ understanding of the instructions, items, and response scales of the instrument and make additional refinements toward establishing the content validity for a PRO for DTs that could be used as a clinical trial endpoint.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants

We sought to include adult patients who had (either at the time of the study or previously) localized or multifocal DTs affecting a variety of anatomic locations. Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 to 75 years and could speak English. The study population also included patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, a genetic condition that is correlated with a higher occurrence of DTs. Patients were ineligible if they were currently enrolled in a therapeutic clinical trial, were physically unable to participate in a 60-minute phone interview, or were affiliated or had a family member affiliated with one of the following: the US FDA or any other government agency that approves medications, an advertising agency, a marketing research company, or a pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. The New England Independent Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from patients before online screening.

Procedure

Five independent, senior academic physicians with expertise in desmoid surgery or medical oncology were interviewed to better understand the disease process and their perspectives on symptoms, signs, and impacts on patient lives.

Two moderators trained in qualitative methodology and content validation interviewing conducted the interview sessions, with a single moderator per patient. To ensure consistency between and across interviews, the content and process of each interview were shared with all team members. Cisco WebEx software was used to conduct and audio-record all interviews. Patients were free to discontinue their participation at any time.

Concept elicitation

CE interviews began with the moderator asking patients to spontaneously identify symptoms and/or impacts that they attributed to their DTs. Patients were then presented with a list of symptoms and impacts that was developed through a review of the literature and expert consultation. The patients were asked if they recognized items from the list that they did not mention during the initial part of the interview. For the final portion of the interview, patients were asked to rate the level of disturbance for each of the identified symptoms or impacts on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (NRS), where 0 indicated “not disturbing at all” and 10 indicated “extremely disturbing.” Supporting Table 1 contains a list of sample CE interview questions.

CE analytic framework

De-identified transcripts were made from all CE interviews. The primary goal of transcript analysis was to organize and catalog patient summaries of symptoms and impacts reported during the interviews via content analysis and ATLAS.ti software.21 A custom code book was created on the basis of participants’ demographics, information about their DT diagnosis and treatment, personal descriptions of desmoids, and the symptom and impact data capture forms. Each transcript was analyzed to determine whether the symptom or impact was mentioned by each respondent on the basis of content analysis of their verbatim responses and whether this mention was spontaneous or required recognition from the list. As part of this process, patient statements reflecting similar concepts were grouped together under the same code. For example, patient statements of “I have trouble sleeping through the night” and “sometimes I can’t fall asleep” would both be included within the theme “difficulty sleeping.” The analyst’s discretion was used to make these decisions. In cases in which this categorization was unclear, moderator discretion or team consensus was used. The frequency of symptoms and impacts was calculated as well as ratings of the average disturbance of symptoms and impacts. Saturation of concept was defined as the point at which additional patient interviews did not contribute unique concepts or information.18 CE interview results were used to develop a draft PRO questionnaire. The response options, recall period, and PRO measure formatting were selected in accordance with FDA recommendations.17

CIs and analytic framework

Before the start of each CI, the moderator asked each patient to log into a WebEx conference line and complete the questionnaire electronically. Upon measure completion, the moderator conducted the interview. The CI guide was developed in accordance with best practice guidelines for conducting CIs when PRO instruments are being developed for use in clinical trials,19 and it included interview probes that addressed patient comprehension of (1) instructions, (2) instrument items (ie, the meaning of the specific symptom, functional impact, and/or other aspect of health status), and (3) response options, including how patients selected their response and interpreted different response units on the scale (eg, what a 0 meant on a 0–10 NRS). Patients were also asked to identify any areas that they found to be confusing, problematic, or irrelevant to their experience.

Audio recordings of the CIs were used by the project team to create detailed notes from each phase of CIs that included information from every patient about the meaning of each section/item in the assessment. After each phase of CIs, any problems or concerns noted by the interviewers were summarized for review by the project team. This review allowed for a quick assessment of patient comprehension and revision of the instrument to facilitate subsequent CI phases.

RESULTS

Concept Elicitation

Thirty-one patients (mean age, 44 years; standard deviation, 13 years; 77% female) completed the CE phase, and the demographics are described in Table 1. The majority of the patients had at least a college degree (71%) and were symptomatic (84%). Tumor site and type varied among all patients. Interviews took approximately 60 minutes to complete.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Information for Concept Elicitation and Cognitive Interviews

| Concept Elicitation (n = 31 [100%]) |

Cognitive Interviews (n = 15 [100%]) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | Mean (SD) | 44 (13) | 45 (12) |

| Median | 43 | 46 | |

| Range | 20–68 | 29–69 | |

| Sex, No. (%) | Male | 7 (23) | 4 (27) |

| Female | 24 (77) | 11 (73) | |

| Highest level of education completed, No. (%) | High school or less | 2 (6) | 1 (7) |

| Some college or associate degree | 7 (23) | 6 (40) | |

| College graduate (4-y degree) | 9 (29) | 1 (7) | |

| Some postcollege education but not graduate degree | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Graduate school degree | 10 (32) | 7 (47) | |

| Symptomatology, No. (%) | Symptomatic | 26 (84) | 14 (93) |

| Asymptomatic | 5 (16) | 1 (7) | |

| Tumor site, No. (%)a | Joint/extremity | 7 (23) | 5 (28) |

| Abdominal wall | 7 (23) | 5 (28) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 8 (26) | 4 (21) | |

| Head/neck | 6 (19) | 1 (6) | |

| Other | 6 (19) | 3 (17) | |

| Tumor type, No. (%) | FAP-associated | 5 (16) | 2 (13) |

| Non-FAP, nonrecurring | 16 (52) | 5 (33) | |

| Non-FAP, recurring | 10 (32) | 8 (53) | |

Abbreviations: FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; SD, standard deviation.

The tumor site counts sum to more than 31 because some patients had multiple tumors.

The 31 interviews were split into 3 “groups” to assess saturation. Group assignment was determined by the chronological order of interview completion. Saturation details for patients and the total number of new concepts that appeared in each interview group are detailed in Table 2. The new appearance of a concept was identified by an X in the transcript group column where it first appeared. Most of the coded concepts were identified in the first group. Because no new concepts were discovered in the second group and only 1 was discovered in the third group (ie, renal/kidney failure), it was determined that saturation was achieved.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of Mentions, Median Disturbance Rating, and Saturation of Symptoms and Impacts for Patients With Desmoid Tumors From Concept Elicitation Interviews by Interview Group (n = 31)

| Overall Symptoms or Impactsa | Frequency of Mentions |

Median Disturbance Rating |

Interview Group Where First Mentioned |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (Interviews 1–10) |

Group 2 (Interviews 11–20) |

Group 3 (Interviews 21–31) |

|||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Disfigurement/altered appearance | 25 | 5.00 | X | ||

| Nerve pain (localized/radiating) | 22 | 6.00 | X | ||

| Decreased range of motion | 21 | 4.00 | X | ||

| Muscle pain (localized/radiating) | 20 | 6.75 | X | ||

| Fatigue | 20 | 5.00 | X | ||

| Nausea | 18 | 4.50 | X | ||

| Hair thinning | 18 | 5.75 | X | ||

| Scarring | 16 | 2.25 | X | ||

| Lack of energy | 15 | 5.50 | X | ||

| Soreness/muscle aches | 14 | 3.50 | X | ||

| Discomfort | 14 | 6.00 | X | ||

| Hot flashes | 13 | 4.50 | X | ||

| Weight loss | 12 | 4.00 | X | ||

| Weakness | 12 | 6.00 | X | ||

| Gastrointestinal issues/dysfunction | 12 | 5.00 | X | ||

| Diarrhea | 11 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Chemo brain | 11 | 5.75 | X | ||

| Nerve damage/pain | 11 | 2.50 | X | ||

| Stiffness | 10 | 3.00 | X | ||

| Dizziness | 10 | 5.25 | X | ||

| Easily full with small amount of food | 9 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Vomiting | 9 | 7.00 | X | ||

| Hand-foot syndrome | 9 | 8.00 | X | ||

| Mouth sores | 8 | 8.50 | X | ||

| Skin sensitivity | 7 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Swelling | 6 | 5.00 | X | ||

| Bloody bowel movements | 5 | 5.50 | X | ||

| Ovarian cysts | 5 | 5.00 | X | ||

| Darkening of skin | 5 | 2.50 | X | ||

| Fever | 4 | 3.00 | X | ||

| Difficulty eating | 3 | 6.00 | X | ||

| Endometriosis | 2 | 5.50 | X | ||

| Renal/kidney failure | 1 | 10.00 | X | ||

| Impacts | |||||

| Fear | 26 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Difficulty sleeping | 24 | 7.50 | X | ||

| Concern about lack of knowledge among health professionals | 23 | 8.00 | X | ||

| Anxiety | 22 | 6.75 | X | ||

| Ongoing medical uncertainty | 22 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Lack of information from health care providers | 20 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Concern for other family members | 20 | 6.25 | X | ||

| Inability to do daily activities | 20 | 6.75 | X | ||

| Depression | 20 | 8.00 | X | ||

| Frustration | 18 | 7.00 | X | ||

| Isolation | 17 | 7.00 | X | ||

| Financial difficulties | 16 | 8.00 | X | ||

| Anger | 15 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Hopelessness | 14 | 8.50 | X | ||

| Stress/difficulty over making treatment decisions | 14 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Inability to do work | 14 | 6.75 | X | ||

| Altered body image/function | 12 | 4.75 | X | ||

| Treatment dissatisfaction | 12 | 7.75 | X | ||

| Low self-esteem | 10 | 6.50 | X | ||

| Worry over becoming pregnant | 7 | 6.00 | X | ||

| No. of new symptoms in each group | 32 | 0 | 1 | ||

| % of total new symptoms (total = 33) | 97 | 0 | 3 | ||

| No. of new impacts in each group | 20 | 0 | 0 | ||

| % of total new impacts (total = 20) | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

Descending frequency of mentions.

A total of 33 unique symptoms were identified (Table 2). Those most frequently mentioned included “disfigurement/altered appearance,” “nerve pain,” “decreased range of motion,” “fatigue,” and “nausea.” Twenty unique impacts were elicited from patients, with “fear,” “difficulty sleeping,” “concern about lack of knowledge among health professionals,” “anxiety,” and “ongoing medical uncertainty” cited most frequently.

Initial Draft of the PRO Instrument

Four key symptom domains (ie, Location [1 item], Pain [7 items], Physical Function [3 items], and Vitality [5 items]) and 5 impact domains (ie, Appearance [2 items], General Impact [1 item], Physical Function/Mobility [6 items], Psychological [6 items], and Sleep [4 items]) were identified, and they resulted in a 35-item draft instrument. A 24-hour recall period was selected for the symptom domain, whereas a 7-day recall period was selected for impacts. The 0 to 10 severity NRS (ie, from “none” [0] to “as bad as you can imagine” [10]) was selected for all symptom items with the exception of the location item, which asked patients to indicate the location(s) of their DTs from a list. A 0 to 10 NRS was also used for impact items; however, the scale anchors varied for amount (ie, “how much”; from “none” [0] to “a great deal” [10]), frequency (ie, “how often”; from “never” [0] to “all the time” [10]), satisfaction (ie, from “not at all” [0] to “as much as you can imagine” [10]), and severity (ie, from “never” [0] to “as bad as you can imagine” [10]).

Cognitive Interviews

CIs were conducted with 15 patients (mean age, 45 years; standard deviation, 12 years; 73% female) independent of the CE sample across 3 phases. Only 1 patient had an education level of high school or less, and most were symptomatic (93%). As with CE, tumor site and type varied. Table 2 contains demographic and clinical information for the CI participants. Interviews took approximately 60 minutes to complete.

After phase 1 of the CIs (n = 5), an item on “swelling in other areas” was added per patient suggestion. Instructions for the impact scale were modified and separated into frequency and disturbance sections to enhance clarity. In addition, a 5-point verbal descriptor scale (ie, “none of the time,” “a little of the time,” “some of the time,” “most of the time,” and “all the time”) was included for the impact items that included frequency (ie, how often) to be evaluated against the 0 to 10 NRS in phase 2.

Upon the conclusion of phase 2 of the CIs (n = 5), a decision was made on the basis of patient feedback to remove mention of attributing symptoms to DTs in the instructions. Six items were removed because of irrelevancy to DTs or redundancy with similar questions (ie, “zapping pain,” “muscle ache,” “throbbing pain,” “worn out,” “impact of difficulty sleeping,” and “difficulty bending, lifting, or stooping”). The “swelling in other areas” item that was added after phase 1 was deleted on the basis of patient feedback. In addition, examples in the “moderate activities” item were revised (ie, playing with children and taking a long walk) per patient suggestion. Patients preferred the 5-point verbal descriptor scale for frequency-based impact items. As such, the 0 to 10 NRS was removed for these questions. Per patient suggestion, an item to assess “weakness around your tumor” was added to compare with the “muscle weakness around your tumor” item in phase 3.

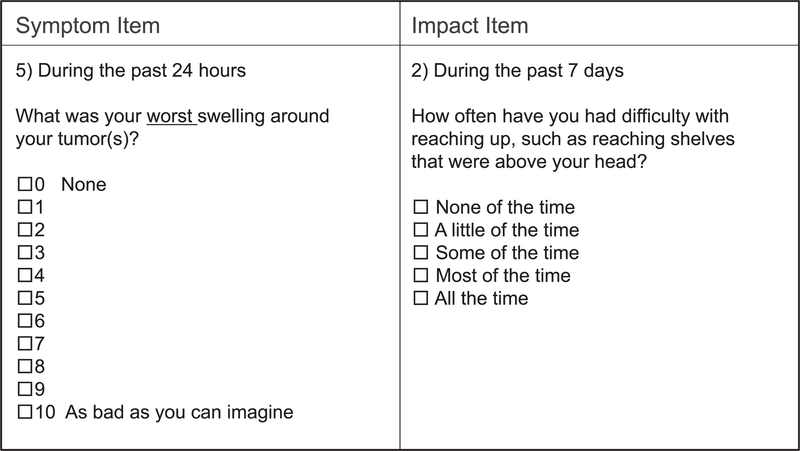

Phase 3 of the CIs was completed among 5 additional patients. The “weakness around your tumor” item added after phase 2 was removed because patients preferred the specificity of “muscle weakness.” In addition, the “worst feeling of tiredness” item was removed because of redundancy with preferred items. The resulting questionnaire includes 28 items that capture symptoms and impacts related to DTs. Table 3 includes a summary tracking matrix of all items that were modified and/or removed, including the justification for any modifications and the phase during which the changes were made. The final version is termed the Gounder/DTRF Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale (GODDESS) and includes symptom (11-item) and impact (17-item) scales (available to all with a material transfer agreement). Examples of GODDESS items are included in Figure 1.

TABLE 3.

Summary Tracking Matrix Showing GODDESS Modified/Removed Terms and Reasons for Modification

| Section | Initial Version | Modified Version | Reason(s) for Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructions | The following questions ask about the impact having desmoid tumor(s) has had on your life in the past 7 days. Please select the one response choice that best represents your answer | The next set of questions are about how often you have felt things about your health in the past 7 days. | Instructions were separated into frequency and disturbance sections to improve clarity by question type (phase 1) |

| The next set of questions are about how much you have felt things about your health in the past 7 days | |||

| The following questions ask about your desmoid tumor symptoms during the past 24 hours. Please select the one response choice that best represents your answer | The following questions ask about your health during the past 24 hours. Please select the one response choice that best represents your answer | The attribution factor was removed to prevent bias and encourage patients to think about their general experiences (phase 2) | |

| Response scale | Frequency (“how often”) items—0–10 scale; 0 = never, 10 = all the time | Frequency (“how often”) items—none of the time, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time, all the time | Patients thought that a descriptive frequency scale would be easier to answer for frequency-type questions (phase 1) |

| Item removal | During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst feeling of zapping pain? | Removed | Patients were unclear what zapping means and described it in various different ways. Three patients did not think that it was relevant (phase 2) |

| During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst feeling of muscle ache? | Removed | Patients thought that this was very similar to dull pain or did not find it relevant to their experiences (phase 2) | |

| During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst feeling of throbbing pain? | Removed | Patients defined this in various ways (eg, pulsating, lesser version of shooting, or swollen) or did not find it relevant to them (phase 2) | |

| During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst feeling of being worn out? | Removed | All patients thought that this was the same as or very similar to fatigue. Most reported fatigue as the preferred form (phase 2) | |

| During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst swelling in other areas due to your tumor(s)? | Removed | Patients did not think that this was relevant or preferred that we ask about the worst swelling around their tumor(s) (phase 2) | |

| During the past 7 days how often did difficulty sleeping (including falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up early) interfere with your usual daily activities? | Removed | Patients thought that the number of sleep-related questions was repetitive. They thought that this question is covered later in the item on daily activities (phase 2) | |

| During the past 7 days what was your worst difficulty bending, lifting, or stooping? | Removed | This was no longer needed because of overlap with the symptom question on range of motion (phase 2) | |

| During the past 24 hours how bad was your worst feeling of tiredness? | Removed | Patients thought that this item was similar to others and identified fatigue as a more relevant, all-encompassing term to describe their experiences (phase 3) | |

| During the past 24 hours what was your worst weakness around your tumor(s)? | Removed | The item was added after phase 2 because patients were confused with the inclusion of the word “muscle” if their muscle had been removed. The item was removed after phase 3 because patients preferred the specificity of “muscle weakness” | |

| Item modification | During the past 24 hours what was your worst swelling around your tumor? | During the past 24 hours what was your worst swelling around your tumor(s)? | A change was implemented in all instances to be inclusive of those with more than 1 tumor (phase 1) |

| During the past 24 hours what was your worst difficulty moving, twisting, or bending near your tumor? | At its worst, how difficult was moving (for example twisting or bending) near your tumor(s)? | Patients were interpreting this question in different ways. They would think of 3 items differently (“difficulty moving” was understood by all) and would tend to answer this item according to the sensation that was most relevant to them (phase 2) | |

| During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty doing moderate activities (such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf)? | During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty doing moderate activities (such as pushing a vacuum cleaner, playing with children, or taking a long walk)? | Patients did not think that bowling, golfing, and pushing a table were regular moderate activities that they encountered. The item was changed to reflect the patient-suggested activities (phase 2) Examples were now included in parentheses for congruency across items (phase 2) | |

| During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty doing vigorous activities such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports? | During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty doing vigorous activities (such as running, lifting heavy objects, or participating in strenuous sports)? | Examples were now included in parentheses for congruency across items (phase 2) | |

| During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty bending, lifting, or stooping? | During the past 7 days how often have you had difficulty moving (for example twisting or bending) near your tumor(s)? | Patients were interpreting this question in different ways. They would think of 3 items differently (“difficulty moving” was understood by all) and would tend to answer this item according to the sensation that was most relevant to them (phase 2) | |

Abbreviation: GODDESS, Gounder/DTRF Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale.

Figure 1.

Sample items from the Gounder/DTRF Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale (GODDESS).

DISCUSSION

To date, disease-specific PROs approved for use in the regulatory setting have been established only for prostate cancer,22 non–small cell lung cancer,23 tenosynovial giant cell tumors,24 and myelodysplastic syndrome.22 Here, we describe the feasibility and prospective establishment of content validity of the first PRO instrument for DTs. GODDESS is a 28-item questionnaire that meets FDA regulatory requirements for a disease-specific (content validation) PRO instrument and is currently undergoing prospective psychometric validation in 2 ongoing, prospective, pivotal registration trials in DTs (NCT03785964 and NCT03459469). After the establishment of psychometric properties consistent with FDA guidance, GODDESS may become a new regulatory endpoint in clinical trials and an important tool in the routine management of patients with DTs in the clinic.

Before our work, clinicians often described pain and functional loss as the symptoms that affected patients with DTs. Our study is one of the first to provide a detailed window into the myriad of symptoms and psychosocial impacts of this disease on the lives of patients.5 As expected, the symptoms and impacts preliminarily show variation by anatomical location, as seen with abdominal desmoids, which cause nausea and early satiety. In addition to pain and functional impairments, health care workers should also address fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, fear, and body dysmorphia. Psychosocial impacts that may be unique to DTs are the frustrations of having a locally infiltrative tumor that is neither malignant (rarely fatal) nor benign and the difficulty in communicating this to family and society at large.

Lastly, this study demonstrates the feasibility and challenges of developing a disease-specific PRO for a rare disease. Industry, regulatory agencies, patient advocacy, and academia recognize the importance of PROs in drug development; however, there are many barriers to successful development and implementation. The first barrier is the fact that the prospective development of a disease-specific instrument following FDA guidance is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and costly.17,23,25 Although this is feasible for common cancers, such initiatives are extremely challenging for rare cancers (or diseases), which now constitute 25% of all malignancies. For rare cancers or diseases, the challenges include 1) the identification of stakeholders (ie, academia, industry, and patient advocacy) who will lead the development effort, 2) the timely engagement of regulatory agencies such as the Clinical Outcome Assessment Qualification (Office of Hematology and Oncology Products) program within the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research to obtain guidance, 3) the acquisition of research funding support, 4) the identification and accrual of patients with rare cancers requiring collaboration across multiple institutions, and, lastly, 5) subsequent validation of the PRO tool in prospective studies.26

Our efforts required successful collaboration among academia, patient advocacy, and industry. The research and development of this instrument were funded by the Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation, a nonprofit patient advocacy group. The patient advocacy group highlighted this study at patient meetings and through its online portals. Lastly, collaboration with academia to involve physicians with DT expertise was essential.

Although HRQOL instruments such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 3014 and the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory16 are routinely implemented in oncology trials, these are not used as primary endpoints in the regulatory setting. Although European regulators (ie, the European Medicines Agency) are more likely to expect and include these instruments as secondary endpoints in label claims, these instruments currently do not satisfy FDA requirements for qualification for use for a label claim because they are not disease-specific instruments.17,25 This is illustrated in the label claims for new oncology drugs approved between 2006 and 2013: 14 of 42 new drugs had PRO-based claims in Europe, and only 1 of 43 did in the United States.27

In conclusion, we describe the methodology, feasibility, and challenges of developing a disease-specific PRO for rare tumors. GODDESS is now translated into Spanish, Dutch, French, Italian, German, and Japanese and is available as an exploratory endpoint for further research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jeanne Whiting, Marlene Portnoy, and all the patients at the Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation and Kannan Krishnamurthy and Howah Hung at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Research and Technology Office.

FUNDING SUPPORT

This study was funded by the Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation and core facility support by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Cancer Center Core Grant P30-CA008748–53.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The Gounder/DTRF Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale (GODDESS) is copyrighted by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and commercial licensing fees are used toward research funds for Mrinal M. Gounder. The other authors made no disclosures.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gounder MM, Thomas DM, Tap WD. Locally aggressive connective tissue tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J, et al. An update on the management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a European consensus initiative between Sarcoma Patients EuroNet (SPAEN) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG). Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2399–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, et al. Sorafenib for advanced and refractory desmoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2417–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Younger E, Wilson R, van der Graaf WTA, Husson O. Health-related quality of life in patients with sarcoma: enhancing personalized medicine. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1642–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husson O, Younger E, Dunlop A, et al. Desmoid fibromatosis through the patients’ eyes: time to change the focus and organisation of care? Support Care Cancer. 2018;27:965–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer care—hearing the patient voice at greater volume. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes—harnessing patients’ voices to improve clinical care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes: an essential component of oncology drug development and regulatory review. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:595–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Uronis H, et al. Validation of the Patient Care Monitor (version 2.0): a review of symptom assessment instrument for cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E. Missing patients’ symptoms in cancer care delivery—the importance of patient-reported outcomes. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2: 433–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timbergen MJM, van de Poll-Franse LV, Grunhagen DJ, et al. Identification and assessment of health-related quality of life issues in patients with sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a literature review and focus group study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:3097–3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaronson NKA, Bergman S, Bullinger B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Published December 2009. Accessed June 27, 2019 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf

- 18.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14:978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. SAGE Publications Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muir T. User’s Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gnanasakthy A, Barrett A, Evans E, D’Alessio D, Romano C. A review of patient-reported outcomes labeling for oncology drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA (2012–2016). Value Health. 2019;22:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarrier KP, Atkinson TM, DeBusk KP, Liepa AM, Scanlon M, Coons SJ. Qualitative development and content validity of the Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC-SAQ), a patient-reported outcome instrument. Clin Ther. 2016;38:794–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelhorn HL, Ye X, Speck RM, et al. The measurement of physical functioning among patients with tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT) using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Food and Drug Administration. Qualification Process for Drug Development Tools. Published January 2014. Accessed June 27, 2019 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm230597.pdf

- 26.Atkinson TM, Gounder MM. Reply to Younger E. et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1643–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basch E, Geoghegan C, Coons SJ, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer drug development and US regulatory review: perspectives from industry, the Food and Drug Administration, and the patient. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.