Summary

Wallerian degeneration is a neuronal death pathway that is triggered in response to injury or disease. Death was thought to occur passively until the discovery of a mouse strain, i.e. Wallerian degeneration slow (WLDS), which was resistant to degeneration. Given that the WLDS mouse encodes a gain-of-function fusion protein, its relevance to human disease was limited. The later discovery that SARM1 (sterile alpha and toll/interleukin receptor (TIR) motif-containing protein 1) promotes Wallerian degeneration, suggested the existence of a pathway that might be targeted therapeutically. More recently, SARM1 was found to execute degeneration by hydrolyzing NAD+. Notably, SARM1 knockdown or knockout prevents neuron degeneration in response to a range of insults that lead to peripheral neuropathy, traumatic brain injury, and neurodegenerative disease. Herein, we discuss the role of SARM1 in Wallerian degeneration and the opportunities to target this enzyme therapeutically.

Keywords: SARM1, neurodegeneration, NAD+, therapeutics

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

SARM1 plays a causative role in traumatic brain injury, peripheral neuropathies, and neurodegenerative diseases, identifying this enzyme as a promising therapeutic target. In this review Loring and Thompson summarize the structure, function, and mechanism of SARM1 and highlight potential mechanisms by which this enzyme triggers neuronal death.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury, peripheral neuropathy, and neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease) account for a major cause of morbidity and mortality and present a growing financial burden, especially in aging populations as there are no approved treatments. These diseases are characterized by axonal cell death that is termed ‘Wallerian-like’ due to its morphological and mechanistic similarities to the degeneration that occurs after nerve injury in vitro, i.e. Wallerian degeneration (Coleman, 2005; Conforti et al., 2014; George et al., 1995). Wallerian degeneration was first described in 1850 following Augustus Waller’s first nerve transection experiments. These studies showed that when an axon is cut or crushed, the portion of the axon distal to the injury site degenerates. In Wallerian-like diseases, metabolic stress or injury triggers microtubule and neurofilament breakdown, resulting in granular disintegration of the distal axonal cytoskeleton (Coleman, 2005). This process is characterized by three phases: 1) the initiation phase that occurs after injury. This phase lasts ~12 h and can be delayed by temperature reduction (Tsao et al., 1999); 2) the latent phase occurs next and lasts ~24–36 h in cell culture and ~36 h in mice (Conforti et al., 2014). During this phase the axon remains morphologically intact, however, cooling can no longer delay degeneration (Tsao et al., 1999). Moreover, the immune system is activated and gene expression data show that the local levels of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors are increased and phagocytes begin to accumulate and infiltrate damaged areas (Sta et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2017); and 3) the final execution phase where the axon distal to the sight of injury undergoes catastrophic fragmentation and granular disintegration (Figure 1A) (Beirowski et al., 2005; Conforti et al., 2014). Since this pathological cell death program was thought to occur passively, drug discovery programs were not focused on identifying agents that could block this process.

Figure 1. Phases of Wallerian degeneration, WLDS and NMNAT isozymes, and the NNMNAT-dependent enzymatic reaction.

A. Wallerian degeneration is characterized by 3 phases: 1) the initiation phase where injury occurs; 2) a latent phase during which the axon remains intact and the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors increases; and 3) an execution phase characterized by abrupt fragmentation and granular disintegration of the axon portion distal to the site of lesion. B. The WLDS chimera is composed of the N-terminal 70 amino acids of UBE4B, 18 amino acids from the untranslated region of NMNAT1 and the full length NMNAT1 gene. The three isozymes are also shown with their subcellular localizations highlighted. C. Reaction catalyzed by NMNATs.

The fortuitous discovery of the Wallerian degeneration slow mutant (WLDS), which delays degeneration, challenged the notion that neuronal death is a passive process (Bisby et al., 1995; Mack et al., 2001). The WLDS mutant was inadvertently discovered during a study of macrophage recruitment to injured neurons. These mutant mice, then known as C57/Bl6/Ola, showed no macrophage recruitment in response to axonal injury (Lunn et al., 1989). Further studies determined that injured axons were not degenerating, and thus were not emitting the proinflammatory signals that typically recruit macrophages. In fact, these mutant axons remained intact for 2–3 weeks post-axonomy. By contrast, wild type axons degenerate within 36 h (Lunn et al., 1989). Interestingly, when the mutant axons eventually degrade, the process is more gradual and the axons waste away, rather than the abrupt catastrophic fragmentation and granular disintegration that occurs with wild type neurons. This degenerative pathway is highly conserved as the WLDS mutation confers delayed degeneration in mice, rats, flies, zebrafish, and primary human neuronal cultures (Kitay et al., 2013; Laser et al., 2006; Lunn et al., 1989; MacDonald et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2010).

After several rounds of backcrossing, the WLDS mutant was found to be a tandem triplication localized to mouse chromosome four (Coleman et al., 1998). The mutation results in the overexpression of a chimeric fusion protein consisting of the N-terminal 70 amino acids of Ubiquitination factor E4B (UBE4B), 18 amino acids from the untranslated region of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Adenyltransferase 1 (NMNAT1), and the remaining full length NMNAT1 protein (Figure 1B) (Mack et al., 2001). Ubiquitin ligases typically facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin to protein substrates to mark them for degradation. In this context, however, the truncated portion of UBE4B lacks enzymatic activity. Instead, these amino acids mislocalize NMNAT1 to the cytosol; NMNAT1 is normally found exclusively in the nucleus (Berger et al., 2005; Mack et al., 2001). NMNAT1 is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the formation of NAD+ from nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and ATP (Figure 1C). The three isozymes in humans and other mammals display unique subcellular localizations, with NMNAT1 being predominantly expressed in the nucleus, whereas NMNAT2 and NMNAT3 are expressed in the cytoplasm and mitochondria, respectively (Berger et al., 2005).

WLDS confers protection by substituting for cytosolic NMNAT2, which is far more labile and actively degraded post-injury as part of this cell death pathway (Gilley and Coleman, 2010). Mitochondrial depolarization results in reduced NMNAT2 axonal transport and synthesis, causing NMNAT2 levels to fall (Loreto et al., 2019). In turn, NAD+ levels fall precipitously and the NMN/NAD+ ratio increases, whereas WLDS neurons maintain NAD+ levels post-injury (Gilley and Coleman, 2010; Loreto et al., 2019). In axons severed from the cell body, supplementation with NAD+ or nicotinamide is sufficient to prevent Wallerian degeneration suggesting a local mechanism for WLDS/NMNAT in preventing axon degeneration (Wang et al., 2005). Moreover, exogenous lentiviral administration of NMNAT2 delays degeneration (Sasaki and Milbrandt, 2010). Notably, more robust protection from axonal degeneration occurs when the nuclear localization sequence in NMNAT1 is mutated, with axons remaining intact for up to 7 weeks post injury (Beirowski et al., 2009). These data indicate that the aberrant localization of NMNAT1 to the cytosol helps maintain the cytosolic NAD+ pool and confer protection from degeneration (Gerdts et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2005).

Consistent with the protection observed in vitro, the WLDS mutant prevents or delays degeneration in a wide variety of neurodegenerative disorders, including animal models of peripheral nerve injury, traumatic brain injury, toxic neuropathy, optic nerve injury, glaucoma, and Parkinson’s disease (Table 1) (Beirowski et al., 2008; Cheng and Burke, 2010; Hasbani and O’Malley, 2006; Howell et al., 2007; Lunn et al., 1989; Sajadi et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2013). In the context of peripheral nerve injury, superior cervical ganglia (SCG) explants from WLDS mice were protected for 72 h after injury compared with wild type explants where degeneration was evident 8 h post-injury (Mack et al., 2001; Osterloh et al., 2012). WLDS mice were also recalcitrant to degeneration in the context of traumatic brain injury (TBI). Specifically, mice showed reduced cognitive and behavioral deficits, which was indicated by spatial and motor learning tests, immediately after TBI (Fox and Faden, 1998). WLDS neurons and mice were also protected from toxic neuropathy. For example, wild type neurons exposed to vincristine, a chemotherapy, rapidly degenerated while WLDS neurons resisted degeneration and resumed growth after the insult (Wang et al., 2013b). Along these lines, WLDS mice showed reduced behavioral pathology compared with wild type mice post-vincristine treatment (Wang et al., 2002). Moreover, WLDS expression was sufficient to prevent optic nerve degeneration in WLDS mice and axonal glaucoma for a least 2 weeks in rats (Beirowski et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013b). Finally, the WLDS mutation is protective in the context of Parkinson’s Disease as WLDS mice treated with the catecholaminergic toxin 6-hydroxydopamine exhibited reduced loss of dopaminergic neurons (Sajadi et al., 2004). In total, these studies demonstrate that the WLDS mutation inhibits Wallerian degeneration.

Table 1.

WLDS gain-of-function and SARM1 loss-of-function show protection from neurodegeneration in mice and rats.

| Disease Indication | WLDS Mutant | SARM1 Knockout | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Nerve Injury | • Neurons remain intact for 14 days post-injury. | • Severed axons in SARM1 knockout mice remain intact for 14 days compared to 3 days in wild type mice. | (Hill et al., 2016; Lunn et al., 1989; Osterloh et al., 2012) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | • Pronounced delay in motor and cognitive impairment in WLDS mice. •Wild type mice began to improve at a faster rate than WLDS mice. |

• Histological evidence shows reduced axonal injury and maintained integrity in SARM1 knockout mice. • Physiological and behavioral deficits not evident. |

(Fox and Faden, 1998; Fox et al., 1998; Henninger et al., 2016) |

| Toxic Neuropathy | • Rat DRG neurons are resistant to degeneration for 10 days without die back. • DRG neurons show evidence of regrowth. • Mice show reduced behavioral and physiological pathology. |

• Degeneration prevented in SARM1 knockout mice. • Behavioral and physiological deficits not evident in knockouts. |

(Geisler et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2001) |

| Optic Nerve Injury | • Delay of degeneration and retinal ganglion cell collapse in WLDS mice. | • SARM1 deficiency delays degeneration in retinal ganglion cells. • SARM1 deletion leads to electrophysiologically normal axons |

(Beirowski et al., 2008; Fernandes et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2013b) |

| Glaucoma | • WLDS delays degeneration for at least 2 weeks in rats. | • SARM1 deficiency delays degeneration in retinal ganglion cells. • SARM1 deletion leads to electrophysiologically normal axons |

(Beirowski et al., 2008; Fernandes et al., 2018; Howell et al., 2007; Howell et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013) |

| Parkinson’s Disease | • WLDS mouse neurons resistant to degeneration after administration of catecholaminergic neurotoxin. • Neuronal processes typically lost during disease course are maintained. |

• T.B.D. | (Cheng and Burke, 2010; Sajadi et al., 2004) |

Discovery of SARM1.

dSARM, the Drosophila orthologue of Sterile Alpha and Toll Interleukin Receptor Motif-containing protein 1 (SARM1), was initially discovered in 2001 through a series of amino acid sequence similarity comparisons (Mink et al., 2001). These studies showed that dSARM is highly conserved in mice, C. elegans, and humans; having ~40% homology to the human protein (Mink et al., 2001). It was later found that human SARM1 functions as an adaptor protein in the innate immune response. The role of SARM1 in innate immunity is discussed below.

In 2012, Osterloh et al. found that dSARM plays a role in neurodegeneration during a Drosophila melanogaster screen for mutants that suppress Wallerian degeneration (Osterloh et al., 2012). Three mutant lines [i.e., l(3)896, l(3)4621), and l(3)4705] conferred resistance to Wallerian degeneration. Next generation sequencing and lethality mapping revealed that all three were loss-of-function mutations within the dSARM gene (Osterloh et al., 2012). Expression of wild type dSARM in these mutants restored the axonal degeneration phenotype, indicating that dSARM plays an active role in the degeneration process (Gerdts et al., 2013). The discovery of dSARM strengthened the theory that Wallerian degeneration is an active rather than passive process. Moreover, dSARM was the first endogenous gene found to delay Wallerian degeneration when ablated.

SARM1 deficiency was subsequently shown to prevent degeneration in mouse neurons post-injury (Gerdts et al., 2013; Osterloh et al., 2012). In these experiments, SCGs from SARM1 knockout mice were resistant to degeneration post-axonomy similarly to WLDS (for ~72 h), whereas wild type SCGs degenerated within 8 h (Osterloh et al., 2012). shRNA knockdown of SARM1 in mouse dorsal root ganglia (DRG) also suppressed degeneration post-axonomy (Gerdts et al., 2013). DRGs from SARM1 knockout mice also fail to degenerate post-axonomy or when treated with vincristine (Gerdts et al., 2013). By contrast, the degeneration phenotype is rescued by the lentiviral delivery of the SARM1 gene, again indicating that SARM1 is essential for the degenerative process.

SARM1 knockout is at least the same if not more protective than the WLDS mutation in several animal models (Table 1). Notably, knockdown of SARM1 12 h before and up to 2 h after injury prevents axonal degeneration (Gerdts et al., 2015). In a mouse model of axonopathy, SARM1 knockout prevents neuronal degeneration and perinatal lethality to the same degree as WLDS; however, targeting SARM1 is more robust as SARM1 knockouts live to old age with no phenotype while WLDS mice develop a hind limb defect at three months of age (Gilley et al., 2017). In the context of traumatic brain injury, SARM1 knockouts do not display behavioral and motor deficits. By contrast, these effects are merely delayed in the presence of the WLDS mutation. SARM1 deficiency also suppresses the degeneration associated with toxic neuropathy and glaucoma to a similar degree as WLDS. These findings provide strong preclinical validation that SARM1 is a novel therapeutic target for treating diseases associated with Wallerian-like degeneration. However, at this point, the molecular mechanism(s) by which SARM1 triggers neuronal degeneration were not known.

Role of SARM1 in the Innate Immune Response.

Prior to the discovery that SARM1 activates neuron degeneration, SARM1 was known to regulate innate immunity (Carty et al., 2006; Mink et al., 2001). SARM1 was originally presumed to function in these processes because it possesses a C-terminal Toll Interleukin Receptor (TIR) domain (Figure 2). In addition to the TIR domain, SARM1 is comprised of two sterile alpha motif (SAM) domains, and an N-terminal armadillo/HEAT repeat (ARM) domain. SAM and ARM domains are generally mediate protein-protein interactions and, in the context of SARM1, promote dimerization and/or oligomerization; SARM1 dimerization was confirmed by FRET and pull down experiments (Gerdts et al., 2013; Summers et al., 2016).

Figure 2. The domain architecture of the five TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins in humans, NAD+ hydrolase mechanism catalyzed by SARM1, and Proposed Activation Mechanism.

A. Schematic depicting the domain architecture of MyD88, MAL, TRIF, TRAM and SARM1. MyD88 is comprised of a death domain (DD), an intermediary domain (ID), and a C-terminal TIR domain. MAL consists of a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2)-binding motif (PIP2) and a C-terminal TIR domain. TRIF has a tumor-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor (TRAF6)-binding motif (T6BM), a TIR domain and a receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motif (RHIM). TRAM is solely composed of a TIR domain. SARM1 consists of an N-terminal HEAT/Armadillo (ARM) domain, two SAM domains and a C-terminal TIR domain. B. SARM1 cleaves NAD+ to form nicotinamide and a mixture of ADPR and cADPR. C. A stimulus relieves inhibition by the ARM domain allowing for dimerization and activation of NAD+ hydrolase activity.

TIR domains are found in other immune cell modulators, including Myeloid Differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), MyD88-adaptor–like protein (Mal), TIR-domain-containing adaptor molecule (TRIF), and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) (Figure 2A). In response to various stimuli (e.g., viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protists), Toll-like receptors (TLRs) dimerize and activate intracellular signaling pathways through these TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins (i.e., MyD88, Mal, TRIF, and TRAM), which ultimately stimulate the transcription and synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and interferons (Panneerselvam and Ding, 2015).

Early studies of SARM1 evaluated its ability to stimulate the immune system as it was presumed that SARM1 would function similarly to other human TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins (Liberati et al., 2004). However, SARM1 did not induce NF-κB dependent transcription (Liberati et al., 2004). Therefore, the function of SARM1 remained ambiguous until Carty et al. showed that SARM1 expression blocked downstream TRIF signaling via the TLR3 and TL4 pathways, suggesting that in humans SARM1 negatively regulates the innate immune response (Carty et al., 2006). Notably, SARM1 overexpression results in a dose-dependent decrease in TRIF signaling while SARM1 knockdown has the opposite effect (Carty et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2010).

Further support for an anti-inflammatory role came in the context of melioidosis, which is the bacterial infection of macrophages (Pudla et al., 2011). Within thirty minutes of infection, SARM1 expression in macrophages is increased, purportedly to reduce the host inflammatory response. SARM1 knockdown decreased bacterial survival in macrophages relative to wild type infection, suggesting that bacterial clearance by the immune system is more effective in the absence of SARM1 (Pudla et al., 2011). SARM1 homologs in fruit flies and shrimp also negatively regulate the immune system (Akhouayri et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013a). The role of SARM1 as a negative regulator of the innate immune response may prevent an overactive and potentially fatal immune response (Bowie and O’Neill, 2000; O’Neill and Bowie, 2007). Despite support for an immunoregulatory role, SARM1 knockout mice show normal immune responses which may suggest that there are redundancies in this pathway or that SARM1 is not a critical regulator of the immune system (Kim et al., 2007).

Interestingly, C. elegans encodes only two TIR domain-containing proteins. Of these proteins, Tir-1 is the recognized orthologue of SARM1 and the only orthologue of a human TIR domain-containing adaptor protein. Given the role of TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins in human TLR signaling, Tir-1 was presumed to be the cytosolic adaptor of Tol-1, the ortholog of human TLRs. Instead, voltage-gated calcium channels and calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II stimulate Tir-1 signaling through the p38-MAPK pathway resulting in L/R asymmetry and increased expression of antimicrobial genes independently of Tol-1 (Chuang and Bargmann, 2005; Couillault et al., 2004; Kurz et al., 2007; Liberati et al., 2004). siRNA knockdown and genetic ablation of Tir-1 rendered C. elegans more susceptible to fungal and bacterial infections, indicating that contrary to the role of SARM1 in humans, Tir-1 is immunostimulatory (Couillault et al., 2004; Liberati et al., 2004). Longevity and development were unaffected by Tir-1 knockout or knockdown, suggesting that Tir-1 may be involved in the response to stress (Couillault et al., 2004; Liberati et al., 2004).

Contrary to the other four TIR adaptor proteins in humans, SARM1 is primarily expressed in the brain. Within the brain, SARM1 is expressed in neurons, where it contributes to microtubule stability, neuronal polarity, axonal outgrowth, dendritic arborization, and the neuronal immune response (Lin et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Interestingly, SARM1 is not present in microglia. In neurons, SARM1 activation stimulates the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Lin et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). The fact that neuronal inflammatory and antiviral cytokine levels are altered in SARM1 knockout mice lends support to a role for SARM1 in this neuronal pathway (Lin et al., 2014). SARM1 stimulates the Jnk-c-Jun axis through the MAPK pathway to initiate this neuronal inflammatory response. Notably, this effect is inhibited when the SARM1-Jnk-c-Jun pathway is blocked. However, deletion of c-Jun has no effect on axon degeneration, but prevents the neuronal immune response, supporting the proposition that SARM1 functions via different pathways to initiate its prodegenerative and immunostimulatory functions (Ghosh et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). Like the prodegenerative pathway, overexpression of full length SARM1 is not sufficient to stimulate the neuronal inflammatory response, but forced dimerization of the TIR domains does appear to initiate the response in the absence of neuronal injury (Wang et al., 2018).

SARM1 also regulates inflammasome formation and chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Carty et al., 2019; Gurtler et al., 2014). Inflammasomes form in response to infection or injury, which leads to interleukin-1ß (IL-1ß) secretion or pyroptosis (Carty et al., 2019). It was unknown how these different responses were regulated until Carty et al. showed that increased SARM1 expression promotes pyroptosis and reduces IL-1ß secretion, whereas SARM1 knockdown decreased pyroptosis and elevated IL-1ß secretion (Carty et al., 2019).

The SARM1 TIR domain hydrolyzes NAD+.

The specific mechanism by which SARM1 promotes axonal degeneration was unclear until Sasaki et al. showed that in response to injury SARM1 deficient axons have NAD+ levels similar to those present in uninjured controls (Sasaki et al., 2016). Given that NAD+ loss is associated with degeneration, these data indicated that SARM1 might regulate NAD+ levels (Gerdts et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Since SARM1 is an adaptor protein in the innate immune response, the field expected that SARM1 would promote NAD+ degradation by associating with an NAD+ metabolizing enzyme rather than possessing any intrinsic enzymatic activity. This hypothesis was also consistent with the fact that the ARM, SAM, and TIR domains, present in SARM1, were not known to possess enzymatic activity in any other proteins and generally mediate protein-protein interactions. Consequently, when NAD+ hydrolase activity was detected in SARM1 preparations, it was thought to be due to the co-purification of an NAD+ hydrolase. However, proteomic analyses did not reveal any known NAD+ hydrolases in a multitude of SARM1 preparations (Essuman et al., 2017). Eventually, a series of rigorous experiments in E. coli, and a cell free protein expression system, demonstrated that SARM1 itself can hydrolyze NAD+ to form nicotinamide and a mixture of ADPR and cyclic ADPR (Figure 2B) (Essuman et al., 2017). Thus, SARM1 has both glycohydrolase and cyclase activities (Essuman et al., 2017). These findings were highly significant because they clarified the opposing effects of WLDS (NAD+ synthesis) and SARM1 (NAD+ degradation) on Wallerian degeneration and further highlighted NAD+ metabolism as a key feature of this death pathway (Figure 3A) (Essuman et al., 2017). Moreover, they showed for the first time that a TIR domain can possess enzymatic activity.

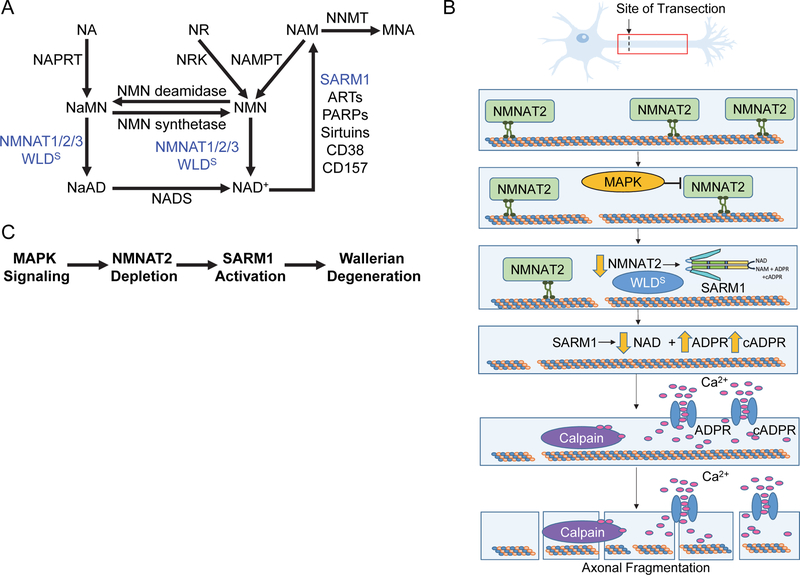

Figure 3. NAD+ biosynthetic pathways and model for SARM1-mediated degeneration.

A. The metabolic pathways that contribute to the synthesis and degradation of NAD+, highlight the roles of NMNAT and SARM1, in axonal protection and destruction, respectively. (NA = nicotinic acid; NR = nicotinamide riboside; NAM = nicotinamide; NNMT = nicotinamide N-methyl transferase; MNA = 1-methyl nicotinamide; NAPRT = nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase; NRK = nicotinamide riboside kinase; NAMPT = nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NaMN = nicotinic acid mononucleotide; NMN = nicotinamide mononucleotide; NMNAT = nicotinamide mononucleotide adenyltransferase isoforms 1, 2, and 3; NaAD = nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide; NADS = NAD synthase) B. SARM1-mediated cleavage of NAD+ is proposed to hold a pivotal role in the execution of degeneration. Under normal conditions, NMNAT2 is constantly transported by anterograde transport. Injury or disease disrupts the microtubule assembly, transport ceases and the levels of the labile isoform fall, activating SARM1. SARM1 activation leads to cleavage of NAD+ and accumulation of ADPR and cADPR, which can activate Ca2+ channels. Increasing calcium levels activates calcium-activated cysteine proteases, calpains, which can cleave microtubules and neurofilaments leading to degeneration. C. Pathway depicting upstream triggers that lead to SARM1 activation and Wallerian degeneration.

SARM1 also possesses a polybasic and hydrophobic N-terminal 27 amino acid mitochondrial localization sequence (MLS) that has been suggested to promote its association with the outer mitochondrial membrane (Gerdts et al., 2013; Panneerselvam et al., 2012). Notably, some evidence suggests that mitochondrial localization increases in response to viral stress or overexpression (Mukherjee et al., 2013; Panneerselvam et al., 2013). Moreover, deletion of SARM1 results in abnormal mitochondrial shape and a delay in mitochondrial-depolarization-induced neuron death (Loreto et al., 2015; Summers et al., 2014). However, the role of this N-terminal motif remains unclear as SARM1 was reported to be diffusely localized throughout the axon under normal conditions (Osterloh et al., 2012) and deletion of the MLS only reduces its association with mitochondria, but does not affect its prodegenerative activity in neurons (Gerdts et al., 2013; Summers et al., 2014).

Model for SARM1-Mediated Degeneration.

As described above, Wallerian degeneration is triggered by metabolic stress or injury, which leads to microtubule and neurofilament breakdown, resulting in granular disintegration of the distal axonal cytoskeleton (Coleman, 2005). Under normal conditions, NMNAT2 is constantly turned over in the axon and replenished via anterograde transport from the cell body (Figure 3B) (Gilley and Coleman, 2010). When the microtubule assembly is disrupted by injury or disease, NMNAT2 transport ceases and the levels of this labile isoform fall rapidly. SARM1 is thought to be activated by the falling levels of NMNAT2, which leads to depletion of NAD+ and accumulation of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), a NMNAT substrate and NAD+ precursor (Gerdts et al., 2015; Loreto et al., 2015). Disruption of axonal mitochondrial membrane potential alone, via the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, also leads to NMNAT2 depletion and an increased NMN/NAD+ ratio (Loreto et al., 2019). This is associated with SARM1 activation and axon degeneration in wild type SCG neurites but not in SARM1 knockouts, which is consistent with the theory that mitochondrial depolarization and NMNAT2 turnover act upstream of SARM1 (Loreto et al., 2019; Summers et al., 2014). Notably, knockout of SARM1 in mice rescues fatal NMNAT2 deficiency, allowing for survival for 24 months without any defects (Gilley et al., 2015). These data further highlight that the levels of NAD+ need to be maintained for neuronal survival.

Although the mechanisms that restrain SARM1 activity in the cell are largely unknown, metabolic stress or injury is thought to relieve autoinhibition mediated by the ARM domain (Figure 2C). The SAM domains can then dimerize, which in turn promotes the dimerization of the TIR domains, leading to increased enzymatic activity (Gerdts et al., 2013; Summers et al., 2016). Support for this model came initially from work in C. elegans showing that the deletion of the first 144 amino acids of TIR-1, which encodes a portion of the ARM domain, enhances TIR-1 signaling (Chuang and Bargmann, 2005). Further evidence came from studies showing that deletion of the ARM domain constitutively activates SARM1 leading to degeneration in the absence of a stressor (Gerdts et al., 2013). Notably, deletion of both the ARM and SAM domains prevents SARM1-mediated NAD+ depletion and subsequent degeneration, suggesting that both the SAM and TIR domains are required for enzymatic activity. Gerdts et al. showed that in the absence of the SAM domains, chemically forced dimerization of the TIR domains (by rapamycin-dependent dimerization of Frb/Fkbp), induces NAD+ hydrolase activity and cell death, further highlighting the importance of TIR domain dimerization for enzymatic activity (Summers et al., 2016). Along these lines, an ARM-SAM construct lacking the TIR domain, acts as a dominant negative and dose dependently inhibits wild type SARM1-mediated NAD+ hydrolase activity (Gerdts et al., 2013). In total, these findings are consistent with the notion that upon insult or injury, inhibition is relieved allowing for SAM and TIR dimerization and increased NAD+ hydrolase activity.

Since SARM1 activation triggers the depletion of NAD+, the ensuing energy crisis could trigger cell death. Alternatively, cell death may arise from the increased amounts of ADPR and cADPR, which are signaling molecules that bind to calcium channels, including the Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) and Ryanodine receptors, to stimulate calcium influx (Figure 3B). Calcium influx also contributes to axonal degeneration as calcium blockers can delay, but not prevent, degeneration (Adalbert et al., 2012; Fliegert et al., 2007; Villegas et al., 2014). Consistent with a role for calcium in this model, WLDS prevents the spike in calcium levels that immediately precedes degeneration (Adalbert et al., 2012; Avery et al., 2012). A prolonged increase in intracellular calcium leads to proteolysis of calpastatin, a calpain-inhibitor, resulting in full scale activation of the calpains (i.e., Ca2+-activated cysteine proteases). Calpains then proteolyze microtubules, microtubule-associated proteins and neurofilaments leading to granular disintegration and fragmentation, which is characteristic of phase 3 of Wallerian degeneration (Yang et al., 2013b). Notably, SARM1 knockout prevents the depletion of calpastatin in addition to inhibiting degeneration (Yang et al., 2013a). Similarly, overexpression of calpastatin protects against granular disintegration. By contrast, shRNA knockdown of calpastatin accelerates injury-induced degeneration (Figure 3B) (Yang et al., 2013a). In total, these data highlight potential roles for both NAD+ depletion and ADPR/cADPR signaling in triggering neuronal cell death. Although NAD+ depletion is associated with Wallerian degeneration, the specific triggers remain unclear. Moreover, loss of the drosophila axonal BTB and BACK domain protein, Axundead (Axed), prevents injury-induced axon degeneration similarly to dSARM loss (Neukomm et al., 2017). In fact, loss of Axed also blocks axonal degeneration caused by constitutively active dSARM, suggesting that dSARM activity/NAD+ depletion alone is insufficient to cause degeneration and that Axed acts downstream of dSARM.

NMN Hypothesis.

Compelling evidence supports a role for NMN as a prodegenerative trigger (Table 2). Initial evidence came from the protective effects of NMN deamidase, a bacterial enzyme that converts NMN into nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN), thereby depleting NMN without manipulating NAD+ levels (Di Stefano et al., 2017; Di Stefano et al., 2015). Further support comes from a recent study, showing that NMN and an NMN mimetic, CZ-48, activate in vitro SARM1 activity by ~3-fold (Zhao et al., 2019). Also supporting the NMN hypothesis is the observation that expression of NMNAT1 and NMN deamidase conferred more robust protection than expression of nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT), nicotinamide riboside (NR), or nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK), which all result in increased NAD+ levels (Sasaki et al., 2016).

Table 2.

Contradicting Hypotheses on the Roles of NAD+ and NMN in Triggering Degeneration.

| Hypothesis | Support | Refute |

|---|---|---|

| NAD Hypothesis | • NAD supplementation is axoprotective (Gerdts et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). • NMNAT1 is axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016) • NAMPT and NRK expression and NR supplementation are axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). • Enzymatically inactive NMNAT is not axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). |

• NMN deamidase is axoprotective (Di Stefano et al., 2017; Di Stefano et al., 2015). • Loss of Axed is sufficient to prevent dSARM-induced degeneration (Neukomm et al., 2017). |

| NMN Hypothesis | • NMN deamidase is axoprotective (Di Stefano et al., 2015). • NMNAT1 is axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). • NAMPT and NRK expression and NR supplementation are axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). • Enzymatically inactive NMN deamidase is not axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). |

• Coexpression of both NMN deamidase and NMN synthetase is axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). • NAMPT and NRK expression and NR supplementation are axoprotective (Sasaki et al., 2016). |

On the other hand, co-expression of NMN deamidase and NMN synthetase, which abolishes the NMN depletion effects of NMN deamidase (NMN levels were elevated above that of control), still confers protection against degeneration (Sasaki et al., 2016). These data argue against NMN being the degenerative trigger. Both NMNAT1 and NMN deamidase fail to block SARM1-mediated NAD+ consumption when they are rendered enzymatically inactive by mutations (Loreto et al., 2015; Sasaki et al., 2016; Sasaki et al., 2009). These findings suggest that the modulation of the NAD+/NMN ratio is essential for their protective capacity; however, it has also been hypothesized that these enzymes could physically interact with SARM1 to restrain its activity. It has also been proposed that NMNAT2 inhibits SARM1 in a similar manner, and that SARM1 is activated by the post-injury depletion of NMNAT2.

MAPK Signaling as a Potential Upstream Trigger for SARM1 Activation.

Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling is thought to promote NMNAT2 turnover and this process serves a pro-degenerative role by stimulating SARM1 activity (Figure 3C) (Walker et al., 2017). Consistent with this model, NAD+ depletion and axonal degeneration are delayed post-injury when MAPK signaling is blocked. However, if SARM1 is activated independent of injury, blocking MAPK signaling has no effect on NAD depletion and axonal degeneration, suggesting that MAPK signaling acts upstream of SARM1 (Figure 3C) (Walker et al., 2017). In addition to promoting NMNAT2 turnover, MAPK signaling was reported to activate SARM1 via the phosphorylation of S548 (Murata et al., 2018). This conclusion was based on the observation that either a JNK inhibitor or a non-phosphorylatable SARM1 mutant modestly decreased SARM1 activity (~2-fold) (Murata et al., 2018). Since S548 is present within a SAM domain, its phosphorylation might relieve autoinhibition, promote SARM1 dimerization, or both. Notably, neuronal cells acquired from a familial Parkinson’s Disease patient had higher levels of S548 phosphorylation compared to a healthy control patient. Additionally, exposure to paraquat, which induces oxidative stress, activated SARM1 by ~2-fold relative to healthy control cells and this increase correlated with an increase in S548 phosphorylation (Murata et al., 2018). Although these two lines of evidence suggest that MAPK signaling acts upstream to activate SARM1, SARM1 was also reported to activate MAPK signaling as part of the neuronal immune response (Wang et al., 2018), leading to ATP depletion and axonal degeneration; this activation is blocked in SARM1 knockouts (Yang et al., 2015). While these conflicting reports need to be reconciled, they may suggest that feedback mechanisms exist to potentiate the response.

SARM1 Conservation.

Relative to the other four human TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins, SARM1 is the most conserved between different species and the mouse, zebrafish, and drosophila orthologues all hydrolyze NAD+ and promote neurodegeneration (Essuman et al., 2017; Summers et al., 2016). Phylogenetic analyses originally suggested that SARM1 and its orthologues have closer evolutionary ties to prokaryotic TIR domains versus metazoan TIR domains; however, recent evidence indicates that structurally, SARM1 is more closely related to plant and animal TIR domains (Essuman et al., 2017; Horsefield et al., 2019; Summers et al., 2016). Interestingly, TIR domain-containing proteins from archaea, bacteria, and plants can also hydrolyze NAD+, whereas many TLR and adaptor proteins lack NAD+ hydrolase activity, begging the question of whether these proteins evolved divergently to lose their enzymatic activity (Essuman et al., 2018; Horsefield et al., 2019).

A key distinguishing feature of Wallerian degeneration compared to other cell death programs is the hydrolysis of NAD+ to form ADPR and cADPR, which is followed by ATP depletion, mitochondrial stress, and swelling of the plasma membrane (Gerdts et al., 2015). Notably, neither pan-caspase inhibition nor anti-apoptotic factor block this form of cell death, differentiating it from apoptosis (Summers et al., 2014). The fact that Wallerian degeneration is not blocked by inhibitors of other programmed cell death pathways, including necroptosis, parathantos, and ferroptosis, suggests that it represents a distinct cell death pathway (Summers et al., 2014).

SARM1 Structure and Function.

Although SARM1 structure and function largely remains an enigma, some progress has been made (see below). TIR domains typically contain several loops (e.g., the BB and DD loops) that are essential for TIR domain signaling (Figure 4) (Summers et al., 2016). The BB loop, which was identified in SARM1 using a secondary structure prediction algorithm, is highly conserved and its mutation negatively affects interactions between SARM1 and MyD88 and TRIF (Carlsson et al., 2016; Summers et al., 2016). Recently, it was reported that the BB loop also forms a major self-association interface between TIR domains (Horsefield et al., 2019). BB loop mutations (e.g., E596K, K597E, and G601P) also prevent degeneration post-axonomy in DRGs (Summers et al., 2016). In the G601P mutant, the BB loop folds over the catalytic cleft, projecting K597 into the active site to interact with E642, which has been suggested to simulate the inactive conformation (Horsefield et al., 2019). The E596K and G601P mutants prevent degeneration triggered by the rapamycin-dependent dimerization of the TIR domain, implying that they impact dimerization. By contrast, the K597E mutant does not prevent degeneration in this context and, in fact, hydrolyzes NAD+ with comparable kinetics to wild type (Summers et al., 2016). These data suggest that K597 is essential for activation of full length SARM1, but dispensable in the context of the constitutively active construct (Summers et al., 2016). The protective effect of the K597E mutation in full length SARM1 is thought to be due to an enhanced (by ~3-fold) association with the ARM domain (Summers et al., 2016).

Figure 4. Insights into SARM1 Structure.

A. SARM1 TIR domain with the BB loop (blue), DD loop (orange) and SS loop (magenta) regions highlighted (PDBID: 6O0Q). B. Amino acid sequence alignments of enzymatically active and inactive TIR domains highlighting the presence of the SS loop (identical residues are highlighted in blue, similar residues in orange and different in green). TIR domains lacking the SS loop do not possess enzymatic activity C. Overlay of SARM1 (Orange), CMP hydrolase (green), and CD38 (blue) highlighting their catalytic residues (PDBID: 6O0Q, 2I65 and 4JEM). D. The SAM domains of SARM1 adopt an octameric structure according to the crystal structure (PDBID: 6QWV). E. Proposed catalytic mechanism. E642 has been proposed to be a nucleophile that attacks the anomeric carbon leading to release of nicotinamide and the formation of a covalent intermediate. Nucleophilic attack by water or N1 of the adenosine moiety regenerates the enzyme. Alternatively, E642 could stabilize the formation of an electrophilic oxocarbenium ion.

The DD loop is poorly conserved, and mutation of its residues have no effect on the degenerative capacity of SARM1 (Summers et al., 2016). In addition to the BB and DD loops, SARM1 uniquely possesses an extended loop between the ßc and αc elements that is referred to as the SARM-specific (SS) loop (Figure 4A). The primary structure of this loop is highly conserved amongst orthologues that hydrolyze NAD+ and it is absent in TIR domains that lack enzymatic activity (Summers et al., 2016). Mutation of residues within the SS-loop (e.g., D627, K628, C629) reduce the degenerative capacity of SARM1, supporting a role for the loop in promoting catalysis (Summers et al., 2016). Along these lines, mutagenesis of residues adjacent to the SS loop (e.g., L626M and D632K) resulted in normal degeneration post-axonomy or negatively affected SARM1 expression in DRGs (Summers et al., 2016).

The discovery that SARM1 possesses enzymatic activity presented the question of how it catalyzes NAD+ cleavage. One hypothesis is that residues in the SS loop are responsible (Summers et al., 2016). An alternative hypothesis arose from domain prediction analyses that identified structural similarity with other nucleotide hydrolases that employ a glutamate to promote catalysis (Figure 4C, 4E) (Essuman et al., 2017). E642 in SARM1 (adjacent to the SS loop) aligns closely with the key active site glutamates in CMP hydrolase and nucleoside 2-deoxyribosyltransferase, suggesting that it is the key catalytic residue in SARM1. Mutation of E642A failed to cleave NAD+ or induce degeneration post vincristine treatment in DRGs, supporting its proposed role as a catalytic residue (Essuman et al., 2017; Horsefield et al., 2019). Furthermore, the catalytic glutamates in the plant TIRs, L6 (E135), RUN1 (E100), and RPS4 (E88) closely align with E642 in SARM1 and mutations to alanine eliminate activity (Horsefield et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2019). In fact, 131 of 146 TIR domains in the plant genus Arabidopsis conserve the putative catalytic glutamate (Wan et al., 2019). Non-enzymatic TIR domains possess glutamates in similar protein regions but these do not align structurally (Horsefield et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2019).

Recently, electron microscopy studies revealed that SARM1 forms an octameric ring in solution (Horsefield et al., 2019; Sporny et al., 2019). Although such an octameric structure is unique for SAM domain-containing proteins, the apoptosome and inflammasome, which also promote cell death, form similar oligomeric structures. Sporny et al. also determined the crystal structure of the two tandem SAM domains (SAM1 and SAM2) (Sporny et al., 2019). Consistent with the electron microscopy data, the SAM domains adopt an octameric configuration (Figure 4D). Structurally the tandem SAM domains are similar, with five alpha helices that adopt the canonical SAM-domain fold in each domain separated by a 10-amino acid linker (Horsefield et al., 2019; Sporny et al., 2019). The 3rd and 5th α-helices of SAM1 directly interact with α2 of SAM2 forming a head-tail orientation. Notably, mutation of residues that line the multimer interface in the first (D454K, I461D, K464D) and second (L531D, V533D) SAM domains decrease the degenerative capacity of SARM1 to the same extent as their effect on multimerization, with SAM1 mutations having a more significant impact. To inhibit octamer formation, Horsefield et al. designed a monomeric mutant (L442R, I461D, L514D, L531D and V533D) that eliminated NAD+ hydrolase activity (Horsefield et al., 2019).

As the first TIR domain with intrinsic enzymatic activity, SARM1 sets a precedent that other TIR domains may also possess unknown enzymatic activities that could have implications in disease. Investigation into the structure and mechanism of SARM1 will enable the characterization of other TIR domains through structural alignments and modelling. In addition, comparison to other NAD+ hydrolases would elucidate the conservation of its structure and mechanism. As the least characterized NAD+ hydrolase, SARM1 could also function in unknown disease mechanisms like other NAD+ hydrolases, which play roles in diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and proinflammatory diseases (Imai and Guarente, 2014; Quarona et al., 2013).

Prospects of Targeting SARM1 in Peripheral Neuropathy and TBI.

The underlying etiology of many neurological diseases, including peripheral neuropathy, traumatic brain injury, and neurodegenerative diseases, is progressive axonal degeneration. Since SARM1 acts as an executioner in this pathway, molecules that block SARM1 activity could completely change the prognosis for these disease types.

Peripheral neuropathies affect more than 20 million people in the United States alone (Geisler et al., 2016). One major cause of peripheral neuropathy is chemotherapies. While such drugs (e.g., taxol and vincristine) inhibit cancer cell growth, they also disrupt the structural integrity of axons resulting in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). As noted above, SARM1 knockout mice are resistant to the development of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy (Geisler et al., 2016). Normally, wild type mice experience mechanical and heat hyperalgesia, decreased action potentials in tail nerve, and degeneration of myelinated axons upon vincristine treatment, yet these symptoms were absent in the SARM1 knockouts (Geisler et al., 2016). SARM1 deficiency also protects mice in paclitaxel and high fat diet-induced neuropathies as well as optic neuropathies (Fernandes et al., 2018; Turkiew et al., 2017). Thus, SARM1 inhibitors could be used in combination with chemotherapy to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy as well as acting as first line therapeutics to treat other peripheral neuropathies.

TBI is a major cause of death and disability worldwide with an estimated 150–200 per million people severely affected every year. Currently, there are no viable options to treat or prevent its pathology; however, SARM1 knockout mice show promising results (Fleminger and Ponsford, 2005; Henninger et al., 2016). Specifically, SARM1 knockout mice experience less axonal injury and maintained axonal integrity, as evidenced by decreased ß-amyloid precursor protein aggregates in corpus collusum axons and suppressed plasma levels of phosphorylated neurofilament subunit H (Henninger et al., 2016). The knockout mice maintained neuronal energy levels as assessed by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, indicating that the neurons remain functional in the context of SARM1 deficiency. Most importantly these molecular assessments translated into improved behavioral outcomes post-TBI; the SARM1 knockout mice lacked deficits evident in wild type mice according to a variety of metrics (Henninger et al., 2016). Additionally, SARM1 knockdown increases interleukin-6 and interferon-ß levels in the brain, the expression of which has been correlated with increased neuroprotection and regeneration, which could contribute to the improved outcomes post-TBI (Lin et al., 2014; Longhi et al., 2011; Penkowa et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2010).

Proof of concept studies have further validated SARM1 as a therapeutic target. Specifically, adeno-associated viral delivery of an inactive mutant form of SARM1, which acts as a dominant negative due to its homooligomerizing properties, is sufficient to delay axon degeneration associated with nerve transection in mice (Geisler et al., 2019). Notably, this dominant negative construct suppressed degeneration for >10 days, which is as potent as that seen in the genetic SARM1 knockouts, suggesting efficacy towards gene therapy derived treatments for these diseases (Geisler et al., 2019).

Although these data are impressive, and no negative effects have been noted in these contexts, it is important to recognize that SARM1 functions in innate immunity and neuronal development. Specifically, SARM1 is a negative regulator of TLR signaling (see above) and regulates dendritic arborization, axonal outgrowth, and neuronal polarization. Moreover, some evidence suggests that SARM1 knockouts experience deficits in associative memory, cognitive flexibility, and social interaction (Chen et al., 2011; Lin and Hsueh, 2014). Therefore, it remains to be determined whether inhibiting SARM1 will be associated with adverse effects long-term.

Significance.

Therapeutically targeting SARM1 will likely be efficacious for a range of neurological diseases. Treatment in the early stages of these diseases could prevent disease manifestation, and in later stages, disease progression. Further study is also warranted to understand this unique enzyme and determine whether inhibition of SARM1 will show efficacy in other neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, the ties between immune regulation and neurodegeneration could potentially allude to a complex interplay between the immune system and neurodegenerative disorders. The high degree of SARM1 conservation through evolution from prokaryotes to eukaryotes indicates that SARM1 homologues could possess an indispensable niche in other species and potentially fill an important cADPR-generating role in some tissues. An understanding of which may be key to unlocking the role of SARM1 in neurodegeneration and immune regulation. Tackling questions such as these as well as what residues are key to catalysis, how SARM1 is stimulated, and regulated will propel the design of therapeutics and our understanding of this remarkable ‘new’ enzyme.

Highlights.

Loss of SARM1 prevents neurodegeneration.

SARM1 is both a TIR adaptor protein and an NAD+ hydrolase.

NAD+ hydrolase activity of SARM1 relies on SAM domain-mediated octamer formation.

SARM1 is a promising therapeutic target for many neurological disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM109767 (to P.R.T.).

Abbreviations:

- SARM1

Sterile Alpha and Toll Interleukin Receptor Motif-containing protein 1

- TIR

Toll/Interleukin Receptor

- WLDS

Wallerian Degeneration Slow

- NMNAT1

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Adenyltransferase 1

- UBE4B

Ubiquitination factor E4B

- NMN

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide

- SCG

Superior Cervical Ganglia

- TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury

- dSARM

drosophila SARM1

- ARM

armadillo/HEAT repeat

- MyD88

Myeloid Differentiation primary response gene 88

- Mal

MyD88-adaptor–like protein

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adaptor molecule

- TRAM

TRIF-related adaptor molecule

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- IL-1ß

interleukin-1ß

- DRG

Dorsal Root Ganglia

- TRPM2

Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2

- NaMN

Nicotinic acid Mononucleotide

- MLS

Mitochondrial Localization signal

- NAMPT

Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyl Transferase

- NR

Nicotinamide Riboside

- NRK

Nicotinamide Riboside Kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- CIPN

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

P.R.T. is a consultant for Disarm Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

- Adalbert R, Morreale G, Paizs M, Conforti L, Walker SA, Roderick HL, Bootman MD, Siklos L, and Coleman MP (2012). Intra-axonal calcium changes after axotomy in wild-type and slow Wallerian degeneration axons. Neuroscience 225, 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhouayri I, Turc C, Royet J, and Charroux B (2011). Toll-8/Tollo negatively regulates antimicrobial response in the Drosophila respiratory epithelium. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery MA, Rooney TM, Pandya JD, Wishart TM, Gillingwater TH, Geddes JW, Sullivan PG, and Freeman MR (2012). WldS prevents axon degeneration through increased mitochondrial flux and enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering. Curr Biol 22, 596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B, Adalbert R, Wagner D, Grumme DS, Addicks K, Ribchester RR, and Coleman MP (2005). The progressive nature of Wallerian degeneration in wild-type and slow Wallerian degeneration (WldS) nerves. BMC Neurosci 6, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B, Babetto E, Coleman MP, and Martin KR (2008). The WldS gene delays axonal but not somatic degeneration in a rat glaucoma model. Eur J Neurosci 28, 1166–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B, Babetto E, Gilley J, Mazzola F, Conforti L, Janeckova L, Magni G, Ribchester RR, and Coleman MP (2009). Non-nuclear Wld(S) determines its neuroprotective efficacy for axons and synapses in vivo. J Neurosci 29, 653–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Lau C, Dahlmann M, and Ziegler M (2005). Subcellular compartmentation and differential catalytic properties of the three human nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase isoforms. J Biol Chem 280, 36334–36341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisby MA, Tetzlaff W, and Brown MC (1995). Cell body response to injury in motoneurons and primary sensory neurons of a mutant mouse, Ola (Wld), in which Wallerian degeneration is delayed. J Comp Neurol 359, 653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A, and O’Neill LA (2000). The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal generators for pro-inflammatory interleukins and microbial products. J Leukoc Biol 67, 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson E, Ding JL, and Byrne B (2016). SARM modulates MyD88-mediated TLR activation through BB-loop dependent TIR-TIR interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty M, Goodbody R, Schroder M, Stack J, Moynagh PN, and Bowie AG (2006). The human adaptor SARM negatively regulates adaptor protein TRIF-dependent Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Immunol 7, 1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty M, Kearney J, Shanahan KA, Hams E, Sugisawa R, Connolly D, Doran CG, Munoz-Wolf N, Gurtler C, Fitzgerald KA, et al. (2019). Cell Survival and Cytokine Release after Inflammasome Activation Is Regulated by the Toll-IL-1R Protein SARM. Immunity 50, 1412–1424 e1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Lin CW, Chang CY, Jiang ST, and Hsueh YP (2011). Sarm1, a negative regulator of innate immunity, interacts with syndecan-2 and regulates neuronal morphology. J Cell Biol 193, 769–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HC, and Burke RE (2010). The Wld(S) mutation delays anterograde, but not retrograde, axonal degeneration of the dopaminergic nigro-striatal pathway in vivo. J Neurochem 113, 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CF, and Bargmann CI (2005). A Toll-interleukin 1 repeat protein at the synapse specifies asymmetric odorant receptor expression via ASK1 MAPKKK signaling. Genes Dev 19, 270–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M (2005). Axon degeneration mechanisms: commonality amid diversity. Nat Rev Neurosci 6, 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Conforti L, Buckmaster EA, Tarlton A, Ewing RM, Brown MC, Lyon MF, and Perry VH (1998). An 85-kb tandem triplication in the slow Wallerian degeneration (Wlds) mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 9985–9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Gilley J, and Coleman MP (2014). Wallerian degeneration: an emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 394–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, Sabatier L, Guichou JF, Kohara Y, and Ewbank JJ (2004). TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat Immunol 5, 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, Loreto A, Orsomando G, Mori V, Zamporlini F, Hulse RP, Webster J, Donaldson LF, Gering M, Raffaelli N, et al. (2017). NMN Deamidase Delays Wallerian Degeneration and Rescues Axonal Defects Caused by NMNAT2 Deficiency In Vivo. Curr Biol 27, 784–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano M, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Orsomando G, Mori V, Gilley J, Brown R, Janeckova L, Vargas ME, Worrell LA, Loreto A, et al. (2015). A rise in NAD precursor nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) after injury promotes axon degeneration. Cell Death Differ 22, 731–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2017). The SARM1 Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor Domain Possesses Intrinsic NAD(+) Cleavage Activity that Promotes Pathological Axonal Degeneration. Neuron 93, 1334–1343 e1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essuman K, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Mao X, Yim AKY, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2018). TIR Domain Proteins Are an Ancient Family of NAD(+)-Consuming Enzymes. Curr Biol 28, 421–430 e424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KA, Mitchell KL, Patel A, Marola OJ, Shrager P, Zack DJ, Libby RT, and Welsbie DS (2018). Role of SARM1 and DR6 in retinal ganglion cell axonal and somal degeneration following axonal injury. Exp Eye Res 171, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleminger S, and Ponsford J (2005). Long term outcome after traumatic brain injury. BMJ 331, 1419–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegert R, Gasser A, and Guse AH (2007). Regulation of calcium signalling by adenine-based second messengers. Biochem Soc Trans 35, 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, and Faden AI (1998). Traumatic brain injury causes delayed motor and cognitive impairment in a mutant mouse strain known to exhibit delayed Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci Res 53, 718–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, Fan L, LeVasseur RA, and Faden AI (1998). Effect of traumatic brain injury on mouse spatial and nonspatial learning in the Barnes circular maze. J Neurotrauma 15, 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, and DiAntonio A (2016). Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain 139, 3092–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Huang SX, Strickland A, Doan RA, Summers DW, Mao X, Park J, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2019). Gene therapy targeting SARM1 blocks pathological axon degeneration in mice. J Exp Med 216, 294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EB, Glass JD, and Griffin JW (1995). Axotomy-induced axonal degeneration is mediated by calcium influx through ion-specific channels. J Neurosci 15, 6445–6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Brace EJ, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2015). SARM1 activation triggers axon degeneration locally via NAD(+) destruction. Science 348, 453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2013). Sarm1-mediated axon degeneration requires both SAM and TIR interactions. J Neurosci 33, 13569–13580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AS, Wang B, Pozniak CD, Chen M, Watts RJ, and Lewcock JW (2011). DLK induces developmental neuronal degeneration via selective regulation of proapoptotic JNK activity. J Cell Biol 194, 751–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, and Coleman MP (2010). Endogenous Nmnat2 is an essential survival factor for maintenance of healthy axons. PLoS Biol 8, e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Orsomando G, Nascimento-Ferreira I, and Coleman MP (2015). Absence of SARM1 rescues development and survival of NMNAT2-deficient axons. Cell Rep 10, 1974–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Ribchester RR, and Coleman MP (2017). Sarm1 Deletion, but Not Wld(S), Confers Lifelong Rescue in a Mouse Model of Severe Axonopathy. Cell Rep 21, 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtler C, Carty M, Kearney J, Schattgen SA, Ding A, Fitzgerald KA, and Bowie AG (2014). SARM regulates CCL5 production in macrophages by promoting the recruitment of transcription factors and RNA polymerase II to the Ccl5 promoter. J Immunol 192, 4821–4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbani DM, and O’Malley KL (2006). Wld(S) mice are protected against the Parkinsonian mimetic MPTP. Exp Neurol 202, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger N, Bouley J, Sikoglu EM, An J, Moore CM, King JA, Bowser R, Freeman MR, and Brown RH Jr. (2016). Attenuated traumatic axonal injury and improved functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in mice lacking Sarm1. Brain 139, 1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CS, Coleman MP, and Menon DK (2016). Traumatic Axonal Injury: Mechanisms and Translational Opportunities. Trends Neurosci 39, 311–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsefield S, Burdett H, Zhang X, Manik MK, Shi Y, Chen J, Qi T, Gilley J, Lai JS, Rank MX, et al. (2019). NAD(+) cleavage activity by animal and plant TIR domains in cell death pathways. Science 365, 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GR, Libby RT, Jakobs TC, Smith RS, Phalan FC, Barter JW, Barbay JM, Marchant JK, Mahesh N, Porciatti V, et al. (2007). Axons of retinal ganglion cells are insulted in the optic nerve early in DBA/2J glaucoma. J Cell Biol 179, 1523–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell GR, Soto I, Libby RT, and John SW (2013). Intrinsic axonal degeneration pathways are critical for glaucomatous damage. Exp Neurol 246, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, and Guarente L (2014). NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol 24, 464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Zhou P, Qian L, Chuang JZ, Lee J, Li C, Iadecola C, Nathan C, and Ding A (2007). MyD88–5 links mitochondria, microtubules, and JNK3 in neurons and regulates neuronal survival. J Exp Med 204, 2063–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitay BM, McCormack R, Wang Y, Tsoulfas P, and Zhai RG (2013). Mislocalization of neuronal mitochondria reveals regulation of Wallerian degeneration and NMNAT/WLD(S)-mediated axon protection independent of axonal mitochondria. Hum Mol Genet 22, 1601–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz CL, Shapira M, Chen K, Baillie DL, and Tan MW (2007). Caenorhabditis elegans pgp-5 is involved in resistance to bacterial infection and heavy metal and its regulation requires TIR-1 and a p38 map kinase cascade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 363, 438–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laser H, Conforti L, Morreale G, Mack TG, Heyer M, Haley JE, Wishart TM, Beirowski B, Walker SA, Haase G, et al. (2006). The slow Wallerian degeneration protein, WldS, binds directly to VCP/p97 and partially redistributes it within the nucleus. Mol Biol Cell 17, 1075–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati NT, Fitzgerald KA, Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Golenbock DT, and Ausubel FM (2004). Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 6593–6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, and Hsueh YP (2014). Sarm1, a neuronal inflammatory regulator, controls social interaction, associative memory and cognitive flexibility in mice. Brain Behav Immun 37, 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, Liu HY, Chen CY, and Hsueh YP (2014). Neuronally-expressed Sarm1 regulates expression of inflammatory and antiviral cytokines in brains. Innate Immun 20, 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi L, Gesuete R, Perego C, Ortolano F, Sacchi N, Villa P, Stocchetti N, and De Simoni MG (2011). Long-lasting protection in brain trauma by endotoxin preconditioning. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31, 1919–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto A, Di Stefano M, Gering M, and Conforti L (2015). Wallerian Degeneration Is Executed by an NMN-SARM1-Dependent Late Ca(2+) Influx but Only Modestly Influenced by Mitochondria. Cell Rep 13, 2539–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto A, Hill CS, Hewitt VL, Orsomando G, Angeletti C, Gilley J, Lucci C, Sanchez-Martinez A, Whitworth AJ, Conforti L, et al. (2019). Mitochondrial impairment activates the Wallerian pathway through depletion of NMNAT2 leading to SARM1-dependent axon degeneration. bioRxiv, 683342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lunn ER, Perry VH, Brown MC, Rosen H, and Gordon S (1989). Absence of Wallerian Degeneration does not Hinder Regeneration in Peripheral Nerve. Eur J Neurosci 1, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JM, Beach MG, Porpiglia E, Sheehan AE, Watts RJ, and Freeman MR (2006). The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron 50, 869–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack TG, Reiner M, Beirowski B, Mi W, Emanuelli M, Wagner D, Thomson D, Gillingwater T, Court F, Conforti L, et al. (2001). Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat Neurosci 4, 1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SM, O’Brien GS, Portera-Cailliau C, and Sagasti A (2010). Wallerian degeneration of zebrafish trigeminal axons in the skin is required for regeneration and developmental pruning. Development 137, 3985–3994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink M, Fogelgren B, Olszewski K, Maroy P, and Csiszar K (2001). A novel human gene (SARM) at chromosome 17q11 encodes a protein with a SAM motif and structural similarity to Armadillo/beta-catenin that is conserved in mouse, Drosophila, and Caenorhabditis elegans. Genomics 74, 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Woods TA, Moore RA, and Peterson KE (2013). Activation of the innate signaling molecule MAVS by bunyavirus infection upregulates the adaptor protein SARM1, leading to neuronal death. Immunity 38, 705–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata H, Khine CC, Nishikawa A, Yamamoto KI, Kinoshita R, and Sakaguchi M (2018). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated phosphorylation of SARM1 regulates NAD(+) cleavage activity to inhibit mitochondrial respiration. J Biol Chem 293, 18933–18943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neukomm LJ, Burdett TC, Seeds AM, Hampel S, Coutinho-Budd JC, Farley JE, Wong J, Karadeniz YB, Osterloh JM, Sheehan AE, et al. (2017). Axon Death Pathways Converge on Axundead to Promote Functional and Structural Axon Disassembly. Neuron 95, 78–91 e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LA, and Bowie AG (2007). The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, Sheehan AE, Avery MA, Hackett R, Logan MA, et al. (2012). dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science 337, 481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panneerselvam P, and Ding JL (2015). Beyond TLR Signaling-The Role of SARM in Antiviral Immune Defense, Apoptosis & Development. Int Rev Immunol 34, 432–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panneerselvam P, Singh LP, Ho B, Chen J, and Ding JL (2012). Targeting of pro-apoptotic TLR adaptor SARM to mitochondria: definition of the critical region and residues in the signal sequence. Biochem J 442, 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panneerselvam P, Singh LP, Selvarajan V, Chng WJ, Ng SB, Tan NS, Ho B, Chen J, and Ding JL (2013). T-cell death following immune activation is mediated by mitochondria-localized SARM. Cell Death Differ 20, 478–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Yuan Q, Lin B, Panneerselvam P, Wang X, Luan XL, Lim SK, Leung BP, Ho B, and Ding JL (2010). SARM inhibits both TRIF- and MyD88-mediated AP-1 activation. Eur J Immunol 40, 1738–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkowa M, Camats J, Giralt M, Molinero A, Hernandez J, Carrasco J, Campbell IL, and Hidalgo J (2003). Metallothionein-I overexpression alters brain inflammation and stimulates brain repair in transgenic mice with astrocyte-targeted interleukin-6 expression. Glia 42, 287–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudla M, Limposuwan K, and Utaisincharoen P (2011). Burkholderia pseudomallei-induced expression of a negative regulator, sterile-alpha and Armadillo motif-containing protein, in mouse macrophages: a possible mechanism for suppression of the MyD88-independent pathway. Infect Immun 79, 2921–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarona V, Zaccarello G, Chillemi A, Brunetti E, Singh VK, Ferrero E, Funaro A, Horenstein AL, and Malavasi F (2013). CD38 and CD157: a long journey from activation markers to multifunctional molecules. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 84, 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi A, Schneider BL, and Aebischer P (2004). Wlds-mediated protection of dopaminergic fibers in an animal model of Parkinson disease. Curr Biol 14, 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, and Milbrandt J (2010). Axonal degeneration is blocked by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (Nmnat) protein transduction into transected axons. J Biol Chem 285, 41211–41215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Nakagawa T, Mao X, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2016). NMNAT1 inhibits axon degeneration via blockade of SARM1-mediated NAD(+) depletion. Elife 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Vohra BP, Lund FE, and Milbrandt J (2009). Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase-mediated axonal protection requires enzymatic activity but not increased levels of neuronal nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. J Neurosci 29, 5525–5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporny M, Guez-Haddad J, Lebendiker M, Ulisse V, Volf A, Mim C, Isupov MN, and Opatowsky Y (2019). Structural Evidence for an Octameric Ring Arrangement of SARM1. J Mol Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sta M, Cappaert NL, Ramekers D, Baas F, and Wadman WJ (2014). The functional and morphological characteristics of sciatic nerve degeneration and regeneration after crush injury in rats. J Neurosci Methods 222, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers DW, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2014). Mitochondrial dysfunction induces Sarm1-dependent cell death in sensory neurons. J Neurosci 34, 9338–9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers DW, Gibson DA, DiAntonio A, and Milbrandt J (2016). SARM1-specific motifs in the TIR domain enable NAD+ loss and regulate injury-induced SARM1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E6271–E6280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao JW, George EB, and Griffin JW (1999). Temperature modulation reveals three distinct stages of Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci 19, 4718–4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiew E, Falconer D, Reed N, and Hoke A (2017). Deletion of Sarm1 gene is neuroprotective in two models of peripheral neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 22, 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas R, Martinez NW, Lillo J, Pihan P, Hernandez D, Twiss JL, and Court FA (2014). Calcium release from intra-axonal endoplasmic reticulum leads to axon degeneration through mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci 34, 7179–7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LJ, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, Brace EJ, Milbrandt J, and DiAntonio A (2017). MAPK signaling promotes axonal degeneration by speeding the turnover of the axonal maintenance factor NMNAT2. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker PA, Harting MT, Jimenez F, Shah SK, Pati S, Dash PK, and Cox CS Jr. (2010). Direct intrathecal implantation of mesenchymal stromal cells leads to enhanced neuroprotection via an NFkappaB-mediated increase in interleukin-6 production. Stem Cells Dev 19, 867–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Essuman K, Anderson RG, Sasaki Y, Monteiro F, Chung EH, Osborne Nishimura E, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J, Dangl JL, et al. (2019). TIR domains of plant immune receptors are NAD(+)-cleaving enzymes that promote cell death. Science 365, 799–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Wang B, Wendu RL, Bi HE, Cao GF, Ji C, Jiang Q, and Yao J (2013a). Protective role of Wallerian degeneration slow (Wld(s)) gene against retinal ganglion cell body damage in a Wallerian degeneration model. Exp Ther Med 5, 621–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fox MA, and Povlishock JT (2013b). Diffuse traumatic axonal injury in the optic nerve does not elicit retinal ganglion cell loss. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72, 768–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhai Q, Chen Y, Lin E, Gu W, McBurney MW, and He Z (2005). A local mechanism mediates NAD-dependent protection of axon degeneration. J Cell Biol 170, 349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JT, Medress ZA, Vargas ME, and Barres BA (2015). Local axonal protection by WldS as revealed by conditional regulation of protein stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 10093–10100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MS, Davis AA, Culver DG, and Glass JD (2002). WldS mice are resistant to paclitaxel (taxol) neuropathy. Ann Neurol 52, 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MS, Fang G, Culver DG, Davis AA, Rich MM, and Glass JD (2001). The WldS protein protects against axonal degeneration: a model of gene therapy for peripheral neuropathy. Ann Neurol 50, 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang S, Liu T, Wang H, Liu K, Wang Q, and Zeng W (2018). Sarm1/Myd88–5 Regulates Neuronal Intrinsic Immune Response to Traumatic Axonal Injuries. Cell Rep 23, 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weimer RM, Kallop D, Olsen O, Wu Z, Renier N, Uryu K, and Tessier-Lavigne M (2013a). Regulation of axon degeneration after injury and in development by the endogenous calpain inhibitor calpastatin. Neuron 80, 1175–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wu Z, Renier N, Simon DJ, Uryu K, Park DS, Greer PA, Tournier C, Davis RJ, and Tessier-Lavigne M (2015). Pathological axonal death through a MAPK cascade that triggers a local energy deficit. Cell 160, 161–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YB, Pandurangan M, Jeong D, and Hwang I (2013b). The effect of troglitazone on lipid accumulation and related gene expression in Hanwoo muscle satellite cell. J Physiol Biochem 69, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S, Tang X, Yu J, Liu J, Ding F, and Gu X (2017). Microarray and qPCR Analyses of Wallerian Degeneration in Rat Sciatic Nerves. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Wu K, Yang M, Xu L, Huang L, Liu H, Tao X, Huang S, and Xu A (2010). Amphioxus SARM involved in neural development may function as a suppressor of TLR signaling. J Immunol 184, 6874–6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZY, Xie XJ, Li WH, Liu J, Chen Z, Zhang B, Li T, Li SL, Lu JG, Zhang L, et al. (2019). A Cell-Permeant Mimetic of NMN Activates SARM1 to Produce Cyclic ADP-Ribose and Induce Non-apoptotic Cell Death. iScience 15, 452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Zhang L, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J, and Gidday JM (2013). Protection of mouse retinal ganglion cell axons and soma from glaucomatous and ischemic injury by cytoplasmic overexpression of Nmnat1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]