Abstract

Background

The four approaches to hysterectomy for benign disease are abdominal hysterectomy (AH), vaginal hysterectomy (VH), laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) and robotic‐assisted hysterectomy (RH).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of different surgical approaches to hysterectomy for women with benign gynaecological conditions.

Search methods

We searched the following databases (from inception to 14 August 2014) using the Ovid platform: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE; EMBASE; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO. We also searched relevant citation lists. We used both indexed and free‐text terms.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which clinical outcomes were compared between one surgical approach to hysterectomy and another.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently selected trials, assessed risk of bias and performed data extraction. Our primary outcomes were return to normal activities, satisfaction, quality of life, intraoperative visceral injury and major long‐term complications (i.e. fistula, pelvi‐abdominal pain, urinary dysfunction, bowel dysfunction, pelvic floor condition and sexual dysfunction).

Main results

We included 47 studies with 5102 women. The evidence for most comparisons was of low or moderate quality. The main limitations were poor reporting and imprecision.

Vaginal hysterectomy (VH) versus abdominal hysterectomy (AH) (nine RCTs, 762 women)

Return to normal activities was shorter in the VH group (mean difference (MD) ‐9.5 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐12.6 to ‐6.4, three RCTs, 176 women, I2 = 75%, moderate quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups for the other primary outcomes.

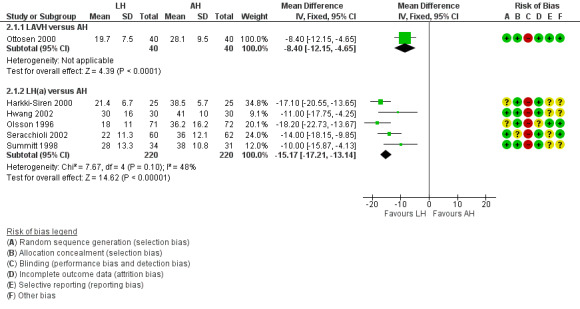

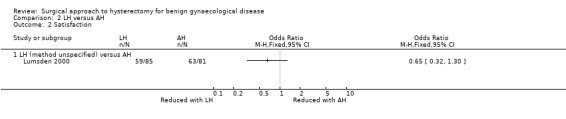

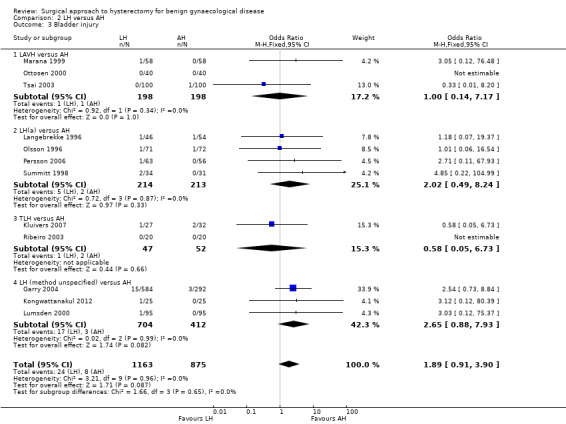

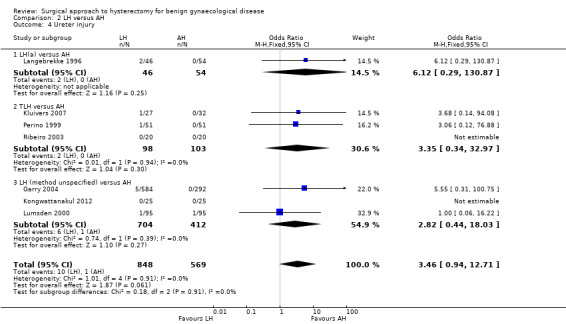

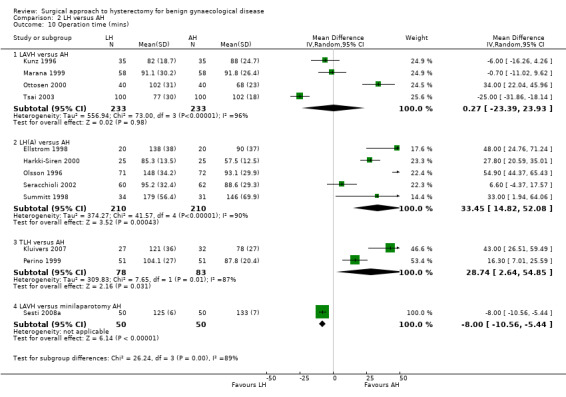

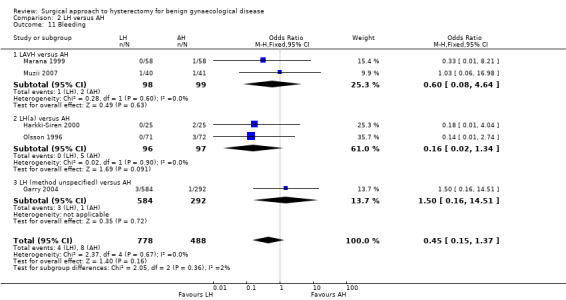

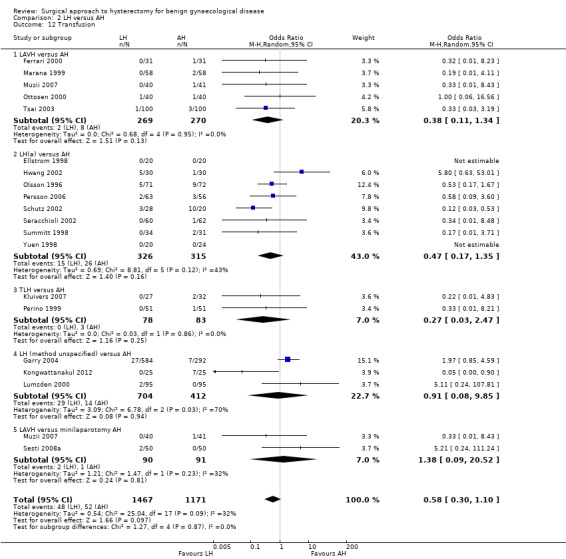

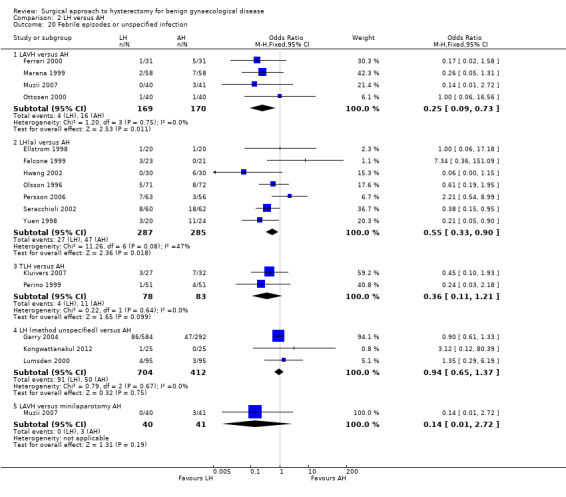

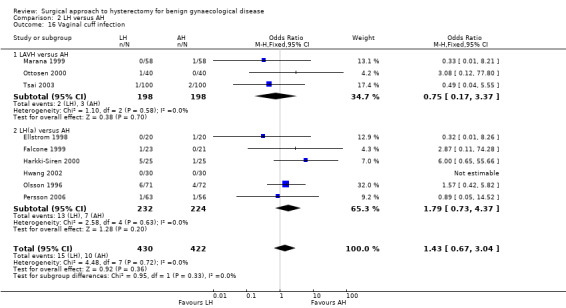

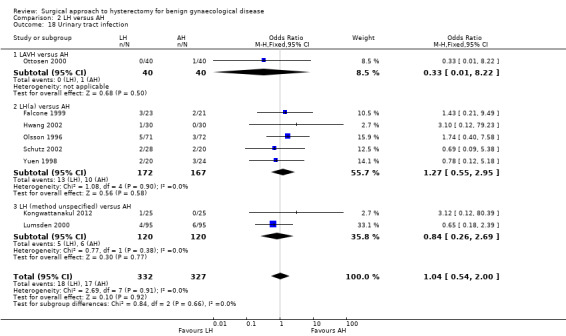

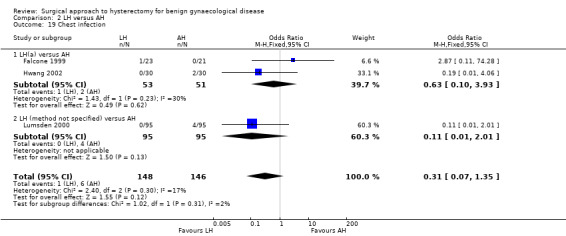

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) versus AH (25 RCTs, 2983 women)

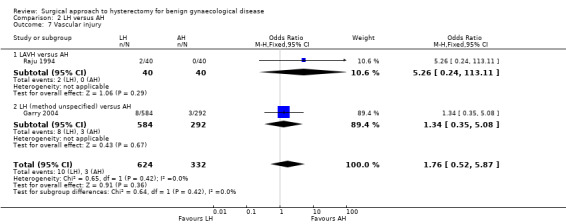

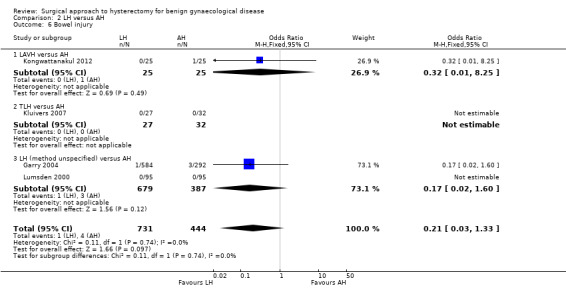

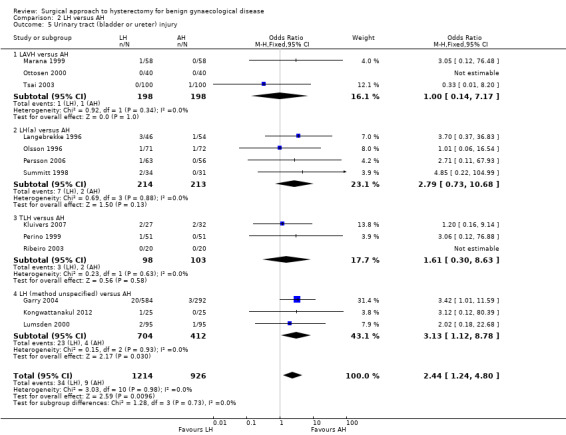

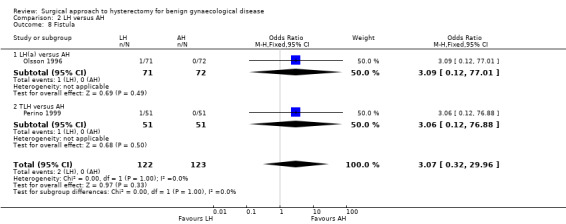

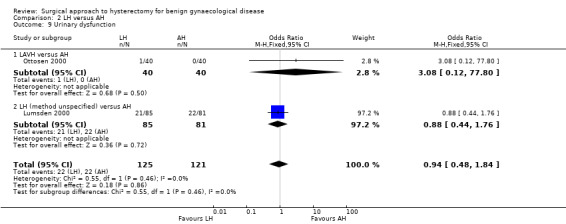

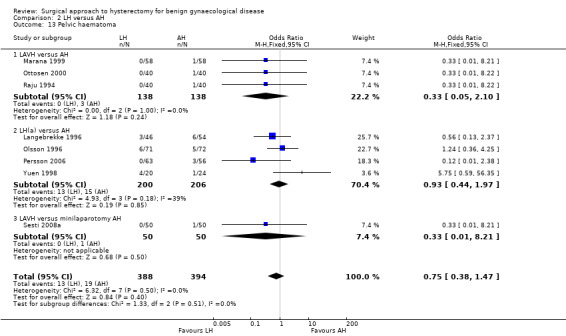

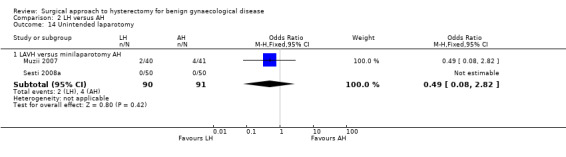

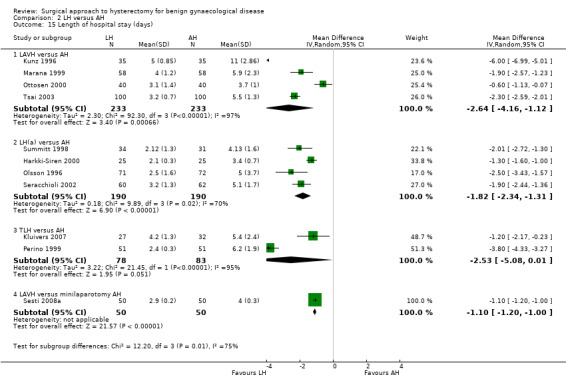

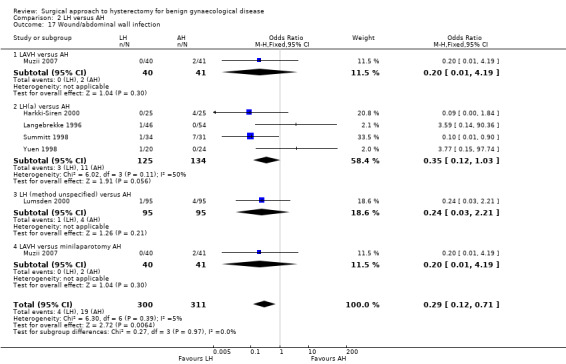

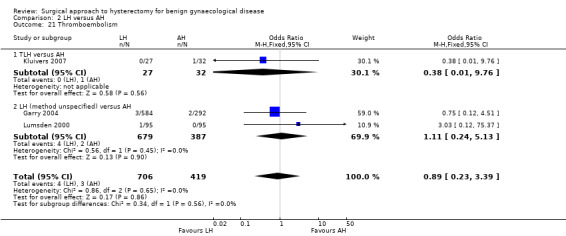

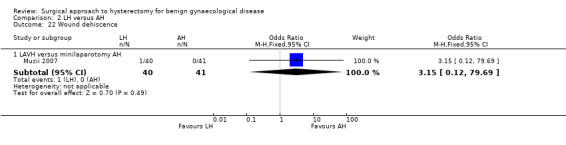

Return to normal activities was shorter in the LH group (MD ‐13.6 days, 95% CI ‐15.4 to ‐11.8; six RCTs, 520 women, I2 = 71%, low quality evidence), but there were more urinary tract injuries in the LH group (odds ratio (OR) 2.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.8, 13 RCTs, 2140 women, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups for the other primary outcomes.

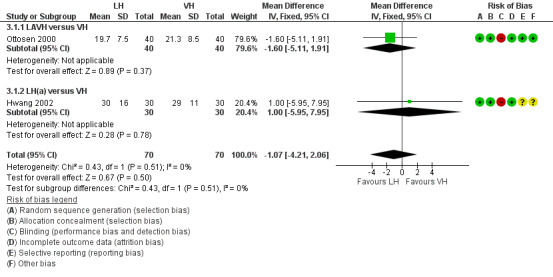

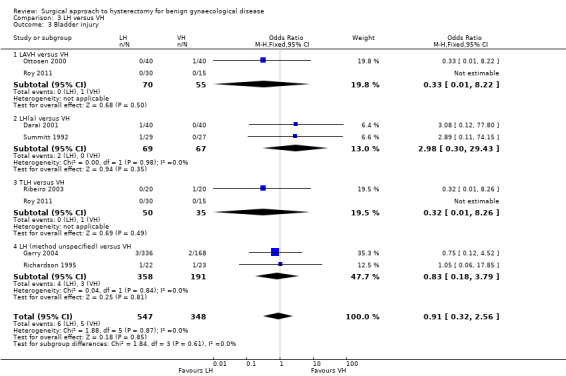

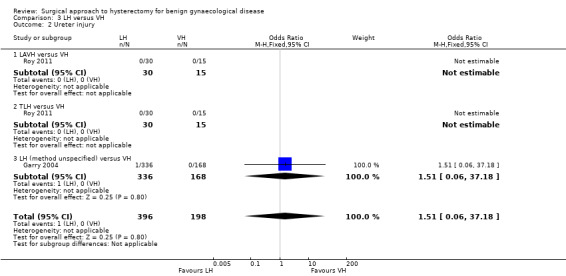

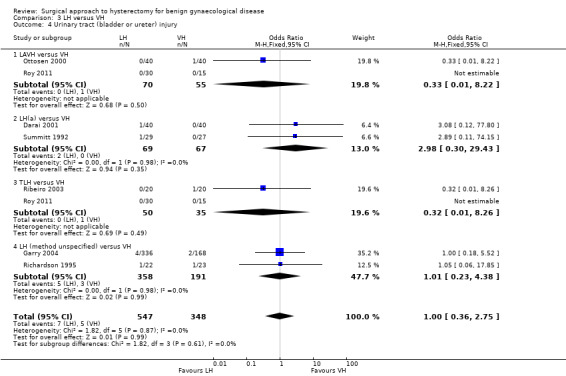

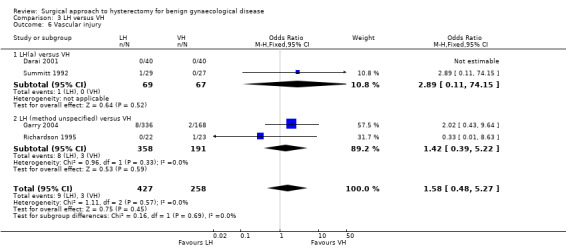

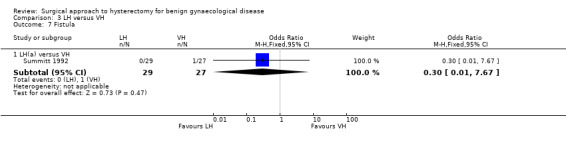

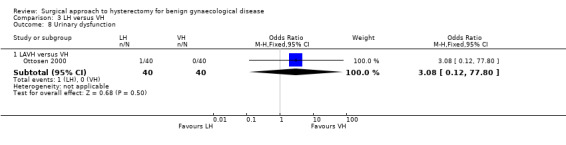

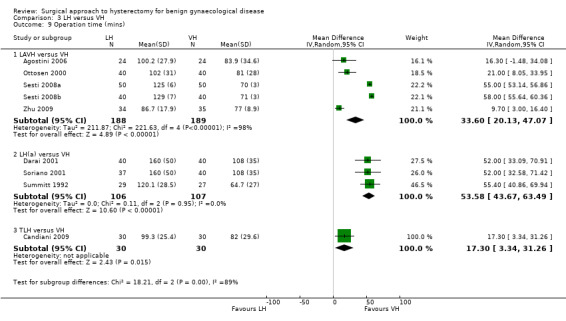

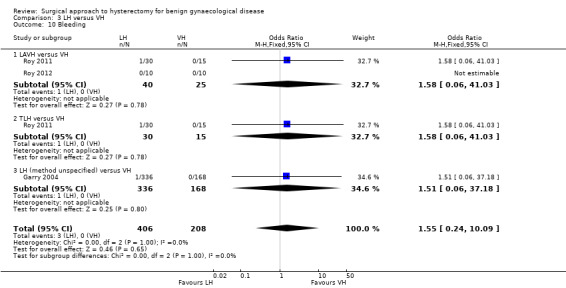

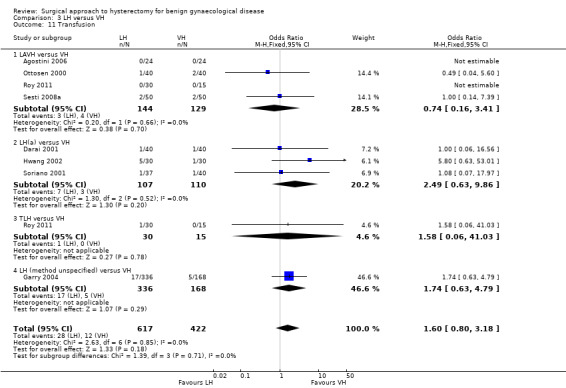

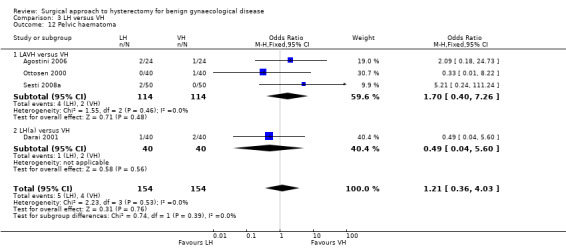

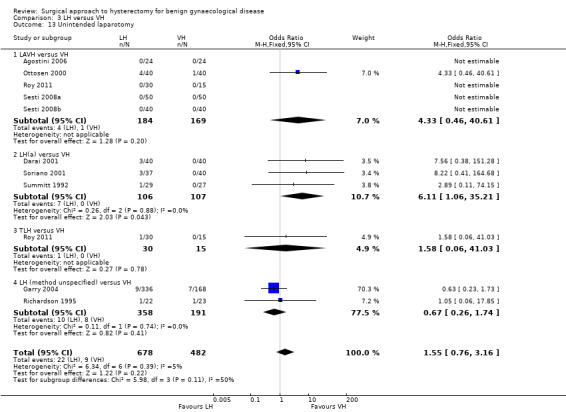

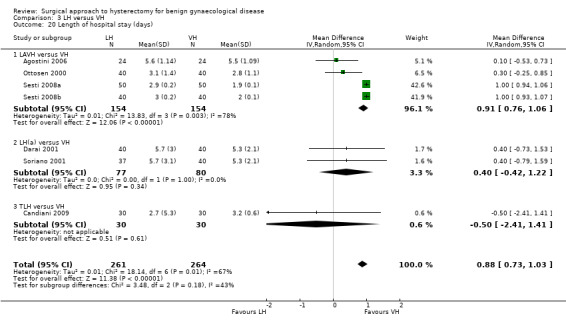

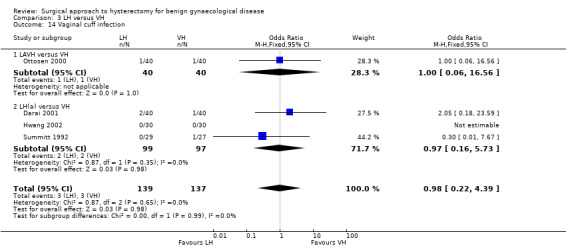

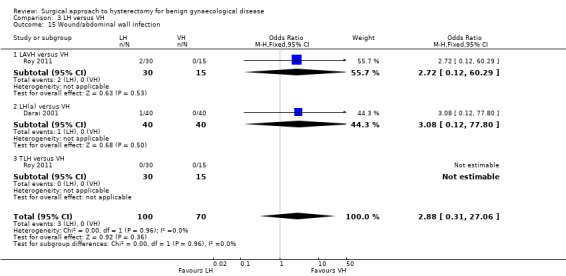

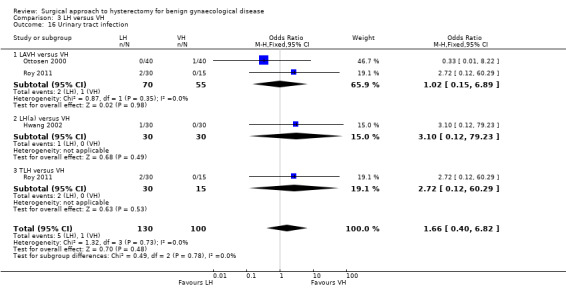

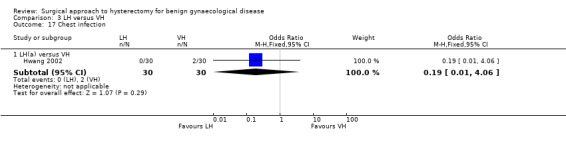

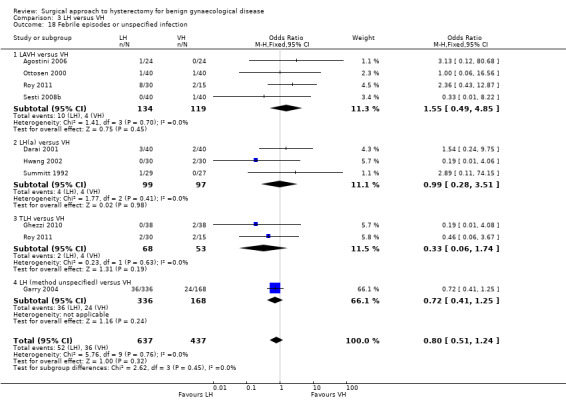

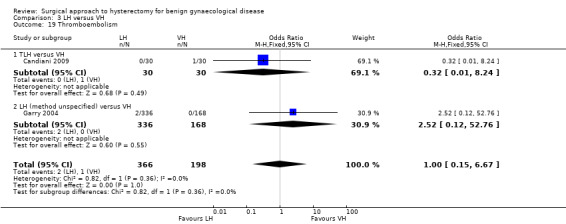

LH versus VH (16 RCTs, 1440 women)

There was no evidence of a difference between the groups for any primary outcomes.

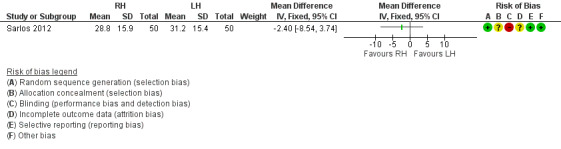

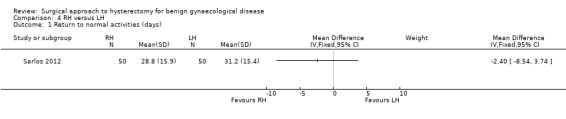

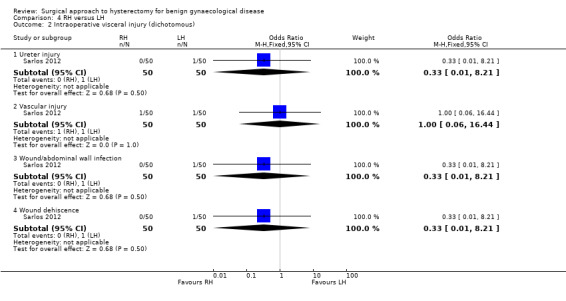

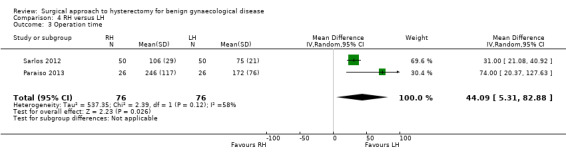

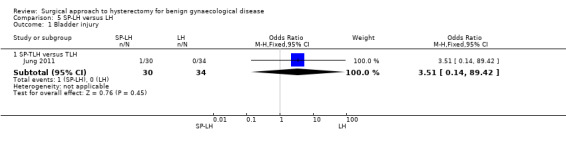

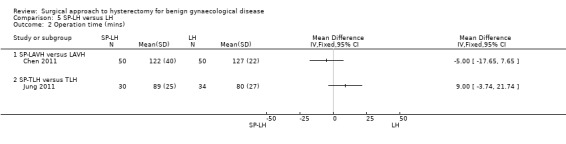

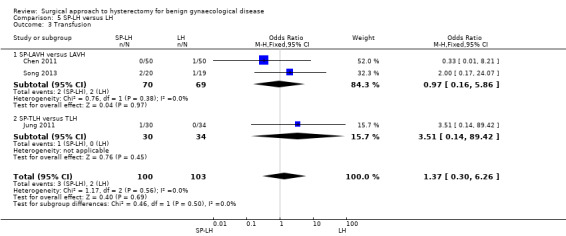

Robotic‐assisted hysterectomy (RH) versus LH (two RCTs, 152 women)

There was no evidence of a difference between the groups for any primary outcomes. Neither of the studies reported satisfaction rates or quality of life.

Overall, the number of adverse events was low in the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

Among women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease, VH appears to be superior to LH and AH, as it is associated with faster return to normal activities. When technically feasible, VH should be performed in preference to AH because of more rapid recovery and fewer febrile episodes postoperatively. Where VH is not possible, LH has some advantages over AH (including more rapid recovery and fewer febrile episodes and wound or abdominal wall infections), but these are offset by a longer operating time. No advantages of LH over VH could be found; LH had a longer operation time, and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) had more urinary tract injuries. Of the three subcategories of LH, there are more RCT data for laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy and LH than for TLH. Single‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy and RH should either be abandoned or further evaluated since there is a lack of evidence of any benefit over conventional LH. Overall, the evidence in this review has to be interpreted with caution as adverse event rates were low, resulting in low power for these comparisons. The surgical approach to hysterectomy should be discussed and decided in the light of the relative benefits and hazards. These benefits and hazards seem to be dependent on surgical expertise and this may influence the decision. In conclusion, when VH is not feasible, LH may avoid the need for AH, but LH is associated with more urinary tract injuries. There is no evidence that RH is of benefit in this population. Preferably, the surgical approach to hysterectomy should be decided by the woman in discussion with her surgeon.

Plain language summary

Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological diseases

Review question

Cochrane authors evaluated which is the most effective and safe surgery for hysterectomy in women with benign gynaecological disease.

Background

Hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease, mostly abnormal uterine bleeding, prolapse or uterine fibroids, is one of the most frequent gynaecological procedures (30% of women by the age of 60; 590,000 procedures annually in the USA). It can be performed through several approaches. Abdominal hysterectomy involves removal of the uterus through an incision in the lower abdomen. Vaginal hysterectomy involves removal of the uterus via the vagina, without an abdominal incision. Laparoscopic hysterectomy involves 'keyhole surgery' through small incisions in the abdomen. The uterus may be removed vaginally or, after morcellation (cutting it up), through one of the small incisions. There are various types of laparoscopic hysterectomy, depending on the extent of the surgery performed laparoscopically compared to that performed vaginally. More recently, laparoscopic hysterectomy has been performed robotically. In robotic surgery, the operation is done by a robot, while the (human) surgeon steers the robot from a chair in the corner of the operating room. It is important to be well informed about the relative benefits and harms of each approach to make best informed choices for each woman needing hysterectomy for a benign disease.

Study characteristics

We analysed 47 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). A RCT is a type of study in which the people being studied are randomly allocated one or other of the different treatments being investigated. This type of study is usually the best way to evaluate whether a treatment is truly effective, i.e. truly helps the patient. A systematic review systematically summarises the available RCTs on a subject.

A total of 5102 women participated. Comparisons were vaginal versus abdominal hysterectomy (nine trials, 762 women), laparoscopic versus abdominal hysterectomy (25 trials, 2983 women), laparoscopic versus vaginal hysterectomy (16 trials, 1440 women) and laparoscopic versus robot‐assisted hysterectomy (two trials, 152 women); in addition there were studies in which three comparisons were made (four trials, 410 women). There were also studies included in which different types of laparoscopic hysterectomies were compared, including single‐port versus multi‐port (three trials, 203 women), total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy (one trial, 101 women) and mini‐laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy (one trial, 76 women). The main outcomes were return to normal activities, satisfaction, quality of life and surgical complications.

Key results

We found that vaginal hysterectomy resulted in a quicker return to normal activities than abdominal hysterectomy. There was no evidence of a difference between them for our other main outcomes.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy also resulted in a quicker return to normal activities than abdominal hysterectomy. However, laparoscopic hysterectomies had a greater risk of damaging the bladder or ureter. There was no evidence of a difference between laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy or between laparoscopic and robot‐assisted hysterectomy for our main outcomes.

We conclude that vaginal hysterectomy should be performed whenever possible. Where vaginal hysterectomy is not possible, both a laparoscopic approach and abdominal hysterectomy have their pros and cons and these should be incorporated in the decision‐making process.

The evidence is current to August 2014.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence for most comparisons was of low or moderate quality. The main limitations were poor reporting of study methods and wide confidence intervals around the estimate of effect.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. It is the most frequently performed major gynaecological surgical procedure, with millions of procedures performed annually throughout the world (Garry 2005). Hysterectomy can be performed for benign and malignant indications. Approximately 90% of hysterectomies are performed for benign conditions, such as fibroids causing abnormal uterine bleeding (Flory 2005). Other indications include endometriosis/adenomyosis, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and prolapse.

Abnormal menstrual bleeding affects women of all ages and is the most common gynaecological reason for referral to secondary care (Spencer 1999). There are a variety of potential causes for abnormal or heavy menstrual bleeding; these include the abovementioned fibroids, endometrial polyps of hyperplasia, adenomyosis, infectious diseases, (early) pregnancy complications or (pre)malignant conditions of the endometrium. However, in a large proportion of women no definitive diagnosis will be confirmed. Several more or less invasive therapies exist for heavy menstrual bleeding; oral contraceptives or the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) are often offered as a first‐line treatment when uterine abnormalities are ruled out. A recent review showed that the LNG‐IUS is the first‐line medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding, with combined hormonal contraceptives as second choice (Lethaby 2015). During the last decade, several new techniques for endometrial ablation have been developed. The effectiveness of these techniques has been described in another Cochrane review (Lethaby 2013). As a result of this variety of treatment options, a patient with heavy menstrual bleeding finds herself confronted with a wide range of possible medical and surgical interventions. Since hysterectomy is the only treatment that provides permanent symptom relief, a rather large proportion of women with the abovementioned conditions will eventually choose to have their uterus removed. This is demonstrated by the fact that rates of hysterectomy have declined less than expected with the introduction of new treatment modalities (Pynnä 2014).

Description of the intervention

Approaches to hysterectomy may be broadly categorised into four options: abdominal hysterectomy (AH); vaginal hysterectomy (VH); laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) where at least some of the operation is conducted laparoscopically (Garry 1994), and robotic‐assisted hysterectomy (RH).

Abdominal hysterectomy: The AH has traditionally been the surgical approach for gynaecological malignancy, when other pelvic pathology is present such as endometriosis or adhesions, and in the context of an enlarged uterus. It remains the 'fallback option' if the uterus cannot be removed by another approach. Mini‐AH refers to an approach to hysterectomy where the abdominal incision does not exceed 7 cm (Sesti 2008a).

Vaginal hysterectomy: VH was originally used only for prolapse but has become more widely utilised for menstrual abnormalities such as dysfunctional uterine bleeding, when the uterus has a fairly normal size. Compared to AH, VH was (and still is) regarded as less invasive and seems to have the advantages of fewer blood transfusions, less febrile morbidity (fever) and less risk of injury to the ureter. However, the disadvantages are more bleeding complications and greater risk of bladder injury (Mäkinen 2013; Moen 2014a).

Laparoscopic hysterectomy: LH usually refers to a hysterectomy where at least part of the operation is undertaken laparoscopically (Garry 1994). This approach requires general laparoscopic surgical expertise. The proportion of hysterectomies performed by LH has gradually increased and, although the surgery tends to take longer, its proponents argue that the main advantages are the possibility of diagnosing and treating other pelvic diseases such as endometriosis, of carrying out adnexal surgery including the removal of the ovaries, the ability to secure thorough intraperitoneal haemostasis (direct laparoscopic vision enables careful sealing of bleeding vessels at the end of the procedure), and a more rapid recovery time from surgery compared to AH (Garry 1998). Three sub‐categorisations of LH have been described (Reich 2003), as follows:

Laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) is where part of the hysterectomy is performed by laparoscopic surgery and part vaginally, but the laparoscopic component of the operation does not involve division of the uterine vessels.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (which we have abbreviated to LH(a)) is where the uterine vessels are ligated laparoscopically but part of the operation is performed vaginally.

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) is where the entire operation (including suturing of the vaginal vault) is performed laparoscopically and there is no vaginal component except for the removal of the uterus. TLH requires the highest degree of laparoscopic surgical skills.

Single‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy and mini‐laparoscopic hysterectomy: In the last decade, single‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy (SP‐LH) and mini‐laparoscopic hysterectomy (mini‐LH, where the incisions do not exceed 3 mm, Ghezzi 2011) have been introduced into the endoscopic field.

Robotic‐assisted hysterectomy: RH has been performed since 1998. In this review RH is considered as a separate approach, which may have its own learning curve, surgical pitfalls and accompanying costs.

A total hysterectomy is the removal of the entire uterus including the cervix. When the cervix is not removed this is known as a subtotal or supracervical hysterectomy. Subtotal hysterectomies are most easily performed abdominally or laparoscopically, although it is possible to conserve the cervix in a VH or LAVH (Lethaby 2012).

The first reported elective hysterectomy was performed through a vaginal approach by Conrad Langenbeck in 1813. The first elective abdominal hysterectomy, a subtotal operation (where the cervix was conserved), was performed by Charles Clay in Manchester in 1863 (Sutton 1997). These approaches remained the only two options until the latter part of the 20th century. The first laparoscopic hysterectomy (LAVH) was reported by Harry Reich in 1989 (Reich 1989). He also reported the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) in 1993. Robotic‐assisted hysterectomies have been performed since 1998.

Several patient factors may influence the surgeon's choice of approach to hysterectomy. For example, multiparous women with heavy menstrual bleeding who opt for hysterectomy may well be suitable for a vaginal approach. However, in the same case but with the suspicion of endometriosis based on dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia or both, the surgeon will more likely be inclined to an abdominal or laparoscopic approach. With regards to enlarged myomatous uteri, surgeons' experience and skills will largely determine the surgical approach to hysterectomy.

In common with the overall hysterectomy rate, the proportion of hysterectomies currently being performed by different approaches varies markedly across countries, within countries, and even between individual surgeons working within the same unit. As mentioned, each gynaecologist will have different indications for the approach to hysterectomy for benign disease, based largely on their own array of surgical skills and the patient characteristics such as uterine size and descent, extra‐uterine pelvic pathology, previous pelvic surgery and other features such as obesity, nulliparity and the need for oophorectomy. Even though VH has been widely considered to be the operation of choice for abnormal uterine bleeding, the VALUE study has shown that, in 1995 in the UK, 67% of the hysterectomies performed for this indication were AH (Maresh 2002). Previous caesarean section, for example, is often considered to be a contraindication for VH. However, this is not supported by cumulative data from four studies indicating no significant difference in complication rates in hysterectomy patients following caesarean section (8 of 430 (1.86%) versus 11 of 1227 (0.89%), P value = 0.12) (Agostini 2005).

Mäkinen 2001 reported a prospective study on the learning curve in 10,110 hysterectomies for benign indications, of which 5875 were AH, 1801 were VH and 2434 were LH. As far as injuries to adjacent organs were concerned, the surgeons' experience significantly correlated inversely with the occurrence of urinary tract injuries in LH and the occurrence of bowel injuries in vaginal hysterectomy. In a following study the overall complication rates fell significantly in LH and markedly in VH over the course of 10 years (Mäkinen 2013). Encouraging vaginal surgery amongst gynaecologists has been shown to be an effective method of increasing VH rates (Mäkinen 2013; Moen 2014a). Finland had a VH rate as low as 7% in the 1980s. Following annual meetings on gynaecological surgery where vaginal and laparoscopic surgery were encouraged, and individual training provided, the VH rate increased to 44% in 2006 (Mäkinen 2013). In the same period of time, ureter injuries decreased, which represents an impressive national learning curve. In addition, the rate of LH increased (from 24% to 36%), with decreasing complication rates (Mäkinen 2013).

How the intervention might work

This review will focus on the benefits and harms of the different surgical approaches to hysterectomy for benign indications. From the patient's perspective, quality of life may well be the most important outcome, especially in surgery for benign indications. Consequently, we will choose patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) as primary outcomes. Injuries to adjacent organs are of concern in hysterectomy and their rates of occurrence differ with the various approaches to hysterectomy and surgical experience level (Brummer 2011; Mäkinen 2001; Mäkinen 2013). It is important to have adequate knowledge of the differences in adverse outcomes in several approaches to hysterectomy, in order to inform patients properly and to gain informed consent based on an adequate amount of data. Furthermore, operation times differ with the different approaches to hysterectomy. Longer operating times are even more likely with RH. In general it is presumed that the vaginal and laparoscopic approach will lead to a quicker recovery compared with open surgery, mainly because of less pain and quicker mobilisation due to smaller incisions.

In the current era of limited healthcare resources, the costs of surgery will likely play a more important role in decision making. Several studies have looked at the subject of the cost‐effectiveness of several types of hysterectomy (Bijen 2009; Pynnä 2014; Sarlos 2010; Tapper 2014). Overall, it is expected that VH will have the lowest costs, followed by AH and LH. Due to the high purchase costs and the use of expensive disposables, RH is likely to be the least cost‐effective. However, there is lack of well‐designed studies that also take societal costs (e.g. the costs of sick leave) into consideration.

Apart from the surgical approach to hysterectomy, other aspects of the surgical technique may have an effect on the outcome of surgery. Examples of this include total versus subtotal (where the cervix is not removed) hysterectomy (Lethaby 2012); Doderlein VH or LAVH versus standard VH or LAVH; techniques to support the vaginal vault; bilateral elective oophorectomy versus ovarian conservation (Orozco 2014); and other strategies used mainly by those conducting laparoscopic surgery with the aim of reducing the likelihood of complications, including the use of vaginal delineators, rectal probes and illuminated ureteric stents. These other aspects are not within the scope of this review (other than for assessing trial quality).

Why it is important to do this review

Since there are multiple approaches to hysterectomy, each with their procedure‐specific advantages and disadvantages, it is important to know which procedure is superior with respect to patient‐related outcomes. In general, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) deliver the highest quality of evidence. When the quality of RCTs of surgical interventions is sufficiently good, this yields information unrivalled in its quality compared to studies of other designs that assess surgical interventions. It was interesting to note that in 1998 there was not a single RCT comparing AH and VH (Garry 1998). The introduction of the newer approaches to hysterectomy (LH, SP‐LH and RH) has stimulated much greater interest in the scientific evaluation of all forms of hysterectomy. However, the more approaches exist, the more complex it becomes to decide on the best approach for each individual woman. This decision cannot be made without up‐to‐date evidence. Nor can it be made without knowing and respecting the informed preferences of patients. This review summarises the existing evidence presented in all published RCTs on benign conditions for hysterectomy. After finding and appraising the existing evidence, and integrating its inferences with clinical expertise, clinicians need to attempt a decision that reflects their patient's values and circumstances (Hoffmann 2014). This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2004, and previously updated in 2006, 2008 and 2009.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of different surgical approaches to hysterectomy for women with benign gynaecological conditions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), in which one surgical approach to hysterectomy was compared to another approach.

We excluded non‐randomised studies, as they are associated with a higher risk of bias.

Types of participants

Studies of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease (uterine fibroids, heavy menstrual bleeding, metrorrhagia of (suspicion of) adenomyosis) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded studies of women with gynaecological cancer. When trials included both women with benign and malignant disease, we requested from the authors a breakdown of data in order to include only women with benign disease. If this information was not forthcoming, we excluded the trial.

We defined dropouts as cases in which hysterectomy was cancelled after randomisation or randomised cases were excluded from analysis by the researchers. We did not regard loss to follow‐up as dropout.

Types of interventions

Surgical approaches to removal of the uterus, where at least one approach was compared with another, were eligible for inclusion. Approaches were as follows:

Abdominal hysterectomy (AH, including mini‐AH): AH involves removal of the uterus through an incision in the lower abdomen.

Vaginal hysterectomy (VH): VH involves removal of the uterus via the vagina, with no abdominal incision.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH, including mini‐LH and single‐port (SP)‐LH): LH involves the use of laparoscopy to perform hysterectomy. We made the distinction between the subcategories of LH based on whether ligation of the uterine vessels was undertaken laparoscopically and whether suturing of the vaginal vault was undertaken vaginally (see Table 4) and this is further explained in the Background section. Thus we further subdivided LH in the analysis into LAVH, LH(a), TLH and non‐categorisable LH (where there is insufficient information or the types of LH are too heterogeneous to otherwise sub‐categorise). There are two other main classifications of LH available in the literature (Nezhat 1995; Richardson 1995) and these are summarised in Table 5 and Table 6, but we did not use these in the meta‐analysis. We defined SP‐LH as LH through one single port. Mini‐LH involves the approach to LH through ports not exceeding 3 mm.

Robotic hysterectomy (RH): RH involves a hysterectomy approach using a robotic system, allowing more ergonomic movements that are easier to perform and are more precise in filtering tremor. One surgeon is seated in a robot console and handles the laparoscope and two to three laparoscopic instruments. RH is generally performed in a similar fashion to a TLH with suturing of the vaginal vault via the robot.

1. Sub‐categorisation of laparoscopic hysterectomy.

| Type of LH | LH versus AH RCTs | LH versus VH RCTs | LH versus LH RCTs |

| LAVH | Ferrari 2000 | Agostini 2006 | Chen 2011 |

| Kunz 1996 | Ottosen 2000 | Roy 2011 | |

| Marana 1999 | Roy 2011 | Song 2013 | |

| Muzii 2007 | Roy 2012 | ||

| Ottosen 2000 | Sesti 2008(a) | ||

| Raju 1994b | Sesti 2008(b) | ||

| Sesti 2008(a) | |||

| Tsai 2003 | |||

| LH(a) | Ellstrom 1998 | Darai 2001 | |

| Falcone 1999 | Hwang 2002 | ||

| Harkki‐Siren 2000 | Soriano 2001 | ||

| Hwang 2002 | Summitt 1992 | ||

| Langebrekke 1998 | Zhu 2009 | ||

| Olsson 1996 | |||

| Persson 2006 | |||

| Schutz 2002 | |||

| Seracchioli 2002 | |||

| Summitt 1998 | |||

| Yuen 1998 | |||

| Zhu 2009 | |||

| TLH | Kluivers 2007 | Candiani 2009 | Ghezzi 2011 |

| Perino 1999 | Ghezzi 2010 | Jung 2011 | |

| Ribeiro 2003 | Morelli 2007 | Paraiso 2013 | |

| Ribeiro 2003 | Roy 2011 | ||

| Roy 2011 | Sarlos 2012 | ||

| Non‐categorisable LH | Garry 2004 | Garry 2004 | |

| Kongwattanakul 2012 | Richardson 1998 | ||

| Lumsden 2000 |

AH: abdominal hysterectomy LAVH: laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy LH: laparoscopic hysterectomy RCT: randomised controlled trial TLH: total laparoscopic hysterectomy VH: vaginal hysterectomy

2. Staging of laparoscopic hysterectomy ‐ Richardson 1995.

| Stage | Laparoscopic content |

| 0 | Laparoscopy done but no laparoscopic procedure before vaginal hysterectomy |

| 1 | Procedure includes laparoscopic adhesiolysis and/or excision of endometriosis |

| 2 | Either or both adnexa freed laparoscopically |

| 3 | Bladder dissected from the uterus laparoscopically |

| 4 | Uterine artery transected laparoscopically |

| 5 | Anterior and/or posterior colpotomy or entire uterus freed laparoscopically |

3. Steps of laparoscopic hysterectomy ‐ Nezhat 1995.

| Step | Laparoscopic content |

| 1 | Severing the round ligaments and dissection of the upper portion of the broad ligament |

| 2 | Severing the tubo‐uterine junction and the utero‐ovarian ligament if the adnexa are to be preserved, or severing the infundibulopelvic ligaments |

| 3 | Severing the uterine vessels |

| 4 | Preparation of the bladder flap |

| 5 | Severing the cardinal uterosacral ligaments complex |

| 6 | Performing anterior and posterior culdotomy and separation of the cervix |

| 7 | Closure of the vaginal cuff |

We thus excluded trials comparing, for example, different vessel sealing techniques within one approach.

Subtotal versus total hysterectomy is the scope of another Cochrane review (Lethaby 2012); we excluded trials making this comparison from the present review. We also excluded trials evaluating different surgical approaches to subtotal hysterectomy. However, if a minority of the women (less than 33%) had a subtotal hysterectomy and the comparison was made versus any of the three approaches outlined above then we included the trial.

Clinical data had to be reported in the included studies, thus excluding studies reporting only differences in laboratory results. If no relevant clinical outcomes were reported (i.e. not in the methods and results section), this was a criterion for exclusion.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the following outcomes:

Primary outcomes

Return to normal activities

Satisfaction and quality of life

-

Intra‐operative visceral injury

Bladder injury

Ureter injury

Urinary tract (bladder or ureter) injury

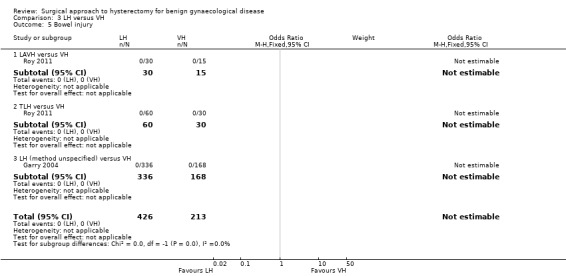

Bowel injury

Vascular injury

-

Major long‐term complications

Fistula

Pelvi‐abdominal pain

Urinary dysfunction

Bowel dysfunction

Pelvic floor condition (prolapse)

Sexual dysfunction

Secondary outcomes

Operation time

Other intra‐operative complication

-

(Sequelae of) bleeding, including

Substantial bleeding

Transfusion

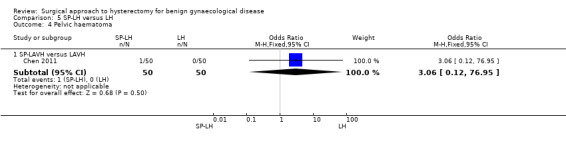

Pelvic haematoma

Unintended laparotomy for approaches not involving routine laparotomy

-

-

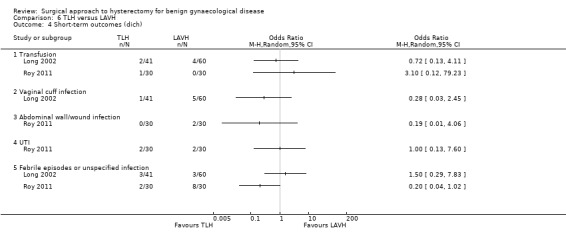

Short‐term outcomes and complications

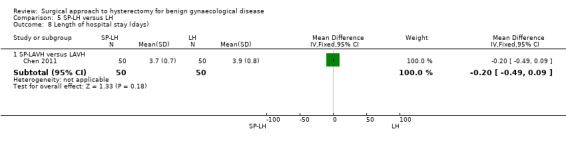

Length of hospital stay

-

Infections

Vaginal cuff

Abdominal wall or wound

Urinary tract infection

Chest infection

Febrile episodes or unspecified infections

Thromboembolism

Unintended laparotomy for approaches not involving routine laparotomy

-

Short‐term outcomes and complications

Length of hospital stay

-

Infections

Vaginal cuff

Abdominal wall or wound

Urinary tract infection

Chest infection

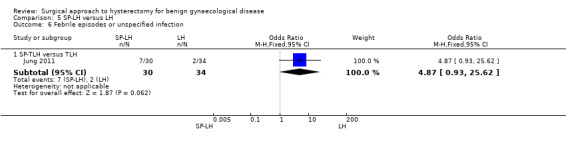

Febrile episodes or unspecified infections

Thromboembolism

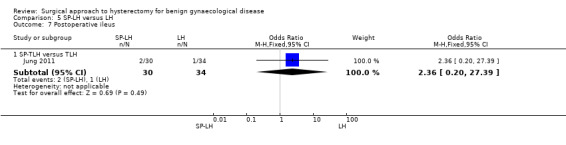

Postoperative ileus

Wound dehiscence

Costs

We sought data on the cost of treatment but we intended to describe these data qualitatively and not to include the information in the meta‐analysis since 'cost' could be defined differently in different studies depending upon whether studies incorporate the cost of sequelae. Different healthcare systems could produce markedly different results.

We used all types of outcome measures for meta‐analysis or described them in the review. This included composite outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all published and unpublished RCTs in August 2014, without language restriction and in consultation with the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Electronic searches

We will repeat the search for trials every two years and update the review if new trials are found. We searched the following electronic databases, trial registers and websites: the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature). We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials, which appears in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0 chapter 6, 6.4.11) (Higgins 2011). We combined the EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL searches with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#random).

The appendices display detailed search strategies, as follows:

Cochrane MDSG Specialised Register (Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in all fields (on Ovid platform July 2014) (Appendix 2);

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to 2014 week 32) (Appendix 3);

EMBASE (1980 to 2014 Week 32) (Appendix 4);

CINAHL (Appendix 5);

Biological Abstracts (1969 to August 2008, not included in searches beyond 2008) (Appendix 6);

PsycINFO (1806 to August Week 1 2014) (Appendix 7).

Other electronic sources of trials included:

-

trial registers for ongoing and registered trials:

DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) on The Cochrane Library (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/cochrane_cldare_articles_fs.html);

Web of Knowledge (http://wokinfo.com/);

OpenGrey (http://www.opengrey.eu/);

LILACS (Literaturo Latino Americana e do Ciências da Saúde) database (http://regional.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=en);

PubMed; and

Google Scholar.

We searched the Clinical Trials Register, a registry of federally and privately funded US clinical trials, with the same keywords only for the initial Cochrane review in 2006 (Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of articles retrieved by the search and contacted experts in the field to obtain additional data. We handsearched relevant journals and conference abstracts that are not covered in the MDSG register in liaison with the Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors performed an initial screen of titles and abstracts retrieved by the search. We retrieved the full texts of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors independently examined these full‐text articles for compliance with the inclusion criteria and selected studies eligible for inclusion in the review.

At least two of four review authors (ET, EC, AL, NJ) performed the selection of trials for inclusion in the initial Cochrane review (Johnson 2005b). Two different review authors (TN and KK) performed the selection of trials for the first update in 2009 (Nieboer 2009) and three review authors (JA, TN and KK) performed this for the current update.

We corresponded with study investigators as required, to clarify study eligibility. We resolved disagreements as to study eligibility by discussion or by referral to a third review author.

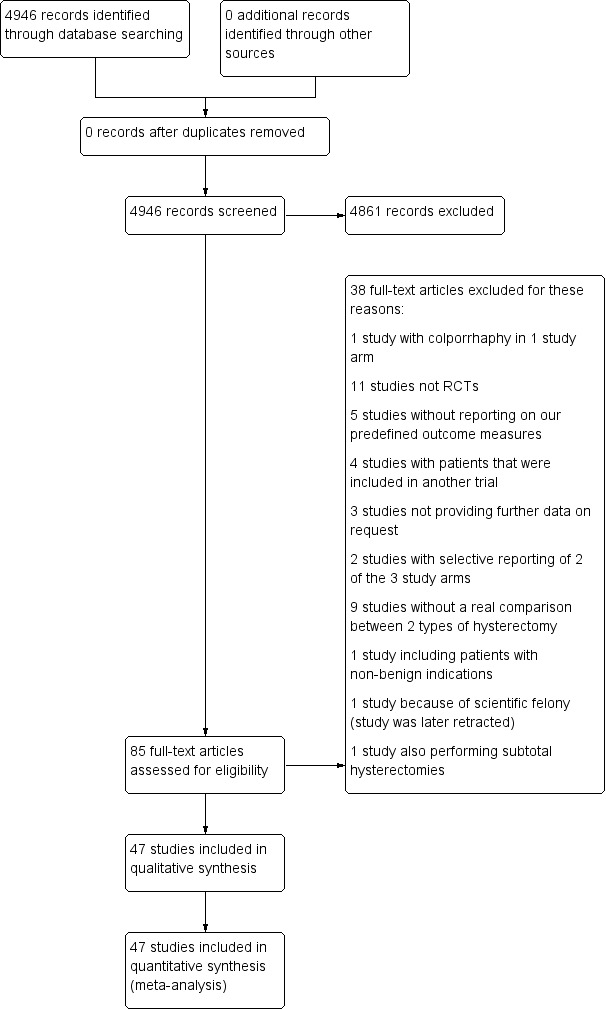

We documented the selection process with a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We excluded trials from the review if they made comparisons other than those specified above. A selection of these trials is detailed in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. Classically we excluded studies if they did not report on differences in clinical outcomes, but did report laboratory results or different anaesthesia techniques or sealing techniques of vessels (e.g. electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing) in hysterectomy patients. Trials are reported in the table Characteristics of excluded studies if there are other reasons for exclusion than those mentioned above.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (at least two review authors from ET, EC, AL, NJ, TN, JA, KK) independently extracted data from eligible studies using a data extraction form designed and pilot‐tested by the authors. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by referral to a third review author. Data extracted included study characteristics and outcome data (see data extraction table for details, Appendix 9). Where studies had multiple publications we collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report is the unit of interest in the review, and such studies have a single study ID with multiple references. We corresponded with study investigators for further data on methods, results or both, as required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (at least two review authors from ET, AL, TN, JA and KK) independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011) for: selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); reporting bias (selective reporting); and other bias. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by referral to a third review author. We described all judgements fully and presented the conclusions in the 'Risk of bias' tables, which we incorporated into the interpretation of the review findings by means of sensitivity analyses (see below).

If randomisation and allocation concealment were not sufficiently reported, we labelled these as unclear or high risk of bias (depending on the extent of description and whether the method described was satisfactory).

If blinding was not performed or not reported, we judged this as high risk of bias.

We considered dropout rates and/or loss to follow‐up below 5% as low risk of bias. If dropouts or losses to follow‐up were not reported or were between 10% and 15%, we judged this as unclear risk of bias. If the dropouts or losses to follow‐up were substantial (i.e. more than 15%), we labelled this as high risk of bias.

If primary and/or secondary outcomes were not (pre)defined and/or a selection of outcomes was reported, we labelled this as unclear or high risk of bias.

Finally, we evaluated the studies included for any other potential bias, such as baseline data not comparable between groups or no description of surgeon experience. (Lack) of surgeon's experience could be particularly important when interpreting the results on, for instance, adverse events or operation time. This seems particularly important for the laparoscopic procedures, as studies have suggested that this technique has a specific learning curve. However, there is no clear‐cut consensus based on current evidence as to how many procedures a surgeon needs to perform (for all types of hysterectomies) to pass this learning curve. Therefore, if a study stated that a surgeon had sufficient experience (without mentioning a specific number) we did not consider this as a potential risk of bias. Depending on the extent of any other bias identified in the study, we judged this as unclear or high risk of bias. If three or more potential other biases were identified, we marked this as high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed statistical analysis in accordance with the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We analysed the data using an intention‐to‐treat model, where data were available.

We expressed dichotomous data as the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study and calculated Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). An increase in the odds of a particular outcome is displayed graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre line, and a decrease in the odds of an outcome is displayed graphically to the left of the centre line.

For continuous data (e.g. length of hospital stay), if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) between treatment groups. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales (e.g. change in haemoglobin), we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). We reversed the direction of effect of individual studies, if required, to ensure consistency across trials. We treated ordinal data (e.g. quality of life scores) as continuous data. We presented 95% CIs for all outcomes.

Where data to calculate ORs or MDs were not available, we utilised the most detailed numerical data available that facilitated similar analyses of included studies (e.g. test statistics, median and (interquartile) ranges, P values). We did not repeat or check values of skewness or kurtosis from the individual studies. We did not include outcome variables that were reported only graphically in the review. We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they were presented in the review, taking account of legitimate differences.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per woman randomised. We briefly summarised data that did not allow valid analysis (e.g. descriptive data) in additional tables and did not carry out meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed the included studies for the number of women lost to follow‐up and exclusions from analysis after randomisation (dropouts). We did not impute missing variables for meta‐analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by the measure of the I2 statistic. We took an I2 measurement greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003; Higgins 2011).

Where statistical heterogeneity (i.e. I2 > 50%) was apparent after pooling of data, we noted this and interpreted statistically significant results cautiously after further analysis using a random‐effects statistical model.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

We stratified the analyses by the type of comparison and the subcategories within hysterectomy approaches.

We used a fixed‐effect model to calculate a pooled estimate of effect in meta‐analyses. If significant statistical heterogeneity was confirmed by the I2 statistic (I2 > 50%), we used a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We analysed the overall category laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) and, where possible, the sub‐categorisation of LH (Table 4).

We took any statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, particularly if there was any variation in the direction of effect. Where there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we considered whether this was related to the subcategory of approach to hysterectomy.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to examine the stability of the results in relation to the following factors.

Exclusion of trials that we judged as at unclear risk of bias with regard to adequate sequence generation in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Exclusion of trials comparing a surgical approach performed by one surgeon (or group of surgeons) with another surgical approach performed by a second (group of) surgeon(s).

The effect of analysing studies of LH subcategories compared to studies of LH pooled as an overall category.

Assessment of quality of evidence

We created Summary of findings tables and measured and reported the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcomes (return to normal activities, urinary tract, bowel and vascular injuries, bleeding and unintended laparotomy) based on the GRADE criteria. We classified the quality of the evidence for each comparison as high, moderate, low or very low (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In our initial search, we identified 4946 articles. Of these, 85 articles were potentially eligible and we retrieved them in full text. We identified nine of these as published abstracts from conference proceedings. The data from two abstracts were published in RCTs included in this review (Cucinella 2000; Hahlin 1994), and we included two studies after additional information was received from the authors (Darai 2001; Miskry 2003). We excluded two studies because they proved not to be randomised studies (Møller 2001; Park 2003). For three studies no inclusion or exclusion decision could be made because insufficient information was available (and there was no response to our request for additional information on study design) (Davies 1998; Pabuccu 1996; Petrucco 1999).

We included 47 studies that met our inclusion criteria. We excluded 36 further studies from the review for reasons that are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We identified no additional studies through searching reference lists. See the study tables: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Where Olsson 1996 is mentioned in the review, we have used the data from Ellstrom 1998b where applicable. The eVALuate trial population was studied in two papers (Garry 2004; Sculpher 2004), and study quality was summarised under Garry 2004. There were two more studies on different outcomes and outcome measures from the same randomised study population: Persson 2006 and Persson 2008 were summarised under Persson 2006; and the long‐term follow‐up study by Nieboer 2012 was summarised under Kluivers 2007. Both Persson 2006 and Kluivers 2007 were already included in the 2009 update. One additional study was identified, which is awaiting classification (Sesti 2014).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for an overview of the included studies.

Study design

All of the included trials had a parallel‐group design. Thirty‐seven of the trials were single‐centre studies (nine from Italy; two from Sweden; four from Taiwan; three from the USA; two each from the UK, Korea, China, India, Brazil, France and Germany; and one each from Finland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Thailand and Hong Kong). Of the 10 multicentre trials, four trials recruited from two centres (Darai 2001 based in France; Langebrekke 1996 based in Norway; Miskry 2003 based in the UK; Paraiso 2013 based in the USA). Three trials recruited from three centres (Summitt 1998 based in the USA; Lumsden 2000 based in the UK; Muzii 2007 based in Italy). One trial from Italy recruited from four centres (Marana 1999); one Swedish trial recruited from five centres (Persson 2006); and a trial based in the UK with additional centres in South Africa (Garry 2004) recruited from 30 centres.

Participants

The 47 studies involved 5102 women.

The reported mean age of participants in the study groups ranged from 38 (Summitt 1992) to 55 years (Agostini 2006).

All of the included studies recruited women who needed a hysterectomy for benign causes; seven studies specifically included women who underwent hysterectomy for symptomatic uterine fibroids (Benassi 2002; Ferrari 2000; Hwang 2002; Long 2002; Ribeiro 2003; Sesti 2008a; Tsai 2003).

Vaginal hysterectomy (VH) versus abdominal hysterectomy (AH)

Benassi 2002 included women with symptomatic enlarged fibroid uteri. Silva Filho 2006 included women with myoma and a uterine size less than 300 cm3. Chakraborty 2011 and Miskry 2003 included women who needed hysterectomy for a benign condition.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) versus AH (including LH with bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy (LH‐BSO) versus AH‐BSO, and LAVH versus minilaparotomy‐AH)

Fourteen of the 21 studies that compared LH with AH specifically included women who were scheduled for an abdominal hysterectomy or who had contraindications for a vaginal hysterectomy (Ellstrom 1998; Falcone 1999; Ferrari 2000; Harkki‐Siren 2000; Kluivers 2007; Kongwattanakul 2012; Lumsden 2000; Marana 1999; Muzii 2007; Olsson 1996; Seracchioli 2002; Summitt 1998; Tsai 2003; Yuen 1998).

LH (including all forms of LH) versus VH

Studies (n = 3) either included women if their uterine size was larger than a certain number (e.g. more than 280 g (Darai 2001; Soriano 2001) or between 300 g and 1500 g (Roy 2012)) or studies (n = 5) excluded women if their uterine size was greater than, for instance, 14 (Ghezzi 2010) or 16 weeks of pregnancy (Richardson 1995; Sesti 2008b; Summitt 1992). One study specifically included women with symptomatic or rapidly growing myoma (Sesti 2008b).

VH versus LH (vLH as it was called in the trial) and AH versus LH (aLH as it was called in the trial)

Garry 2004 included women scheduled for hysterectomy for non‐malignant conditions.

LH (including laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH)) versus AH (including mini‐AH) versus VH

Four of the five trials specifically included women with uterine fibroids: e.g. leiomyomas of less than 15 cm (Ottosen 2000), leiomyomas of more than 8 cm and a maximum of three myomas (Hwang 2002), symptomatic myoma (Sesti 2008a), or any fibroid (Ribeiro 2003). The fifth study included women who were scheduled for hysterectomy with a uterine volume of 10 to 12 weeks of gestation and who had delivered at least one child (Zhu 2009).

Robotic‐assisted hysterectomy (RH) versus LH

Both Paraiso 2013 and Sarlos 2012 included patients who were scheduled for a hysterectomy for benign conditions. In Sarlos 2012, uterine weight had to be less than 500 g.

Single‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy (SP‐LH) versus LH

The three trials included women who had an indication for hysterectomy, no evidence of gynaecologic malignancy and an appropriate status for laparoscopic surgery (ASA 1 or 2) (Chen 2011; Jung 2011; Song 2013). Uterine size was also used as an exclusion criterion: more than 12 weeks gestation (Jung 2011); more than 20 weeks (Song 2013), and greater than 120 mm x 80 mm x 80 mm (Chen 2011).

LAVH versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH)

In Long 2002, women were included if they had contraindications for vaginal hysterectomy (a uterine weight greater than 280 g, previous pelvic surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, need for adnexectomy, lack of uterine descent and limited vaginal access).

LAVH versus TLH versus VH

In Roy 2011, women were included if they had benign pathology of the uterus and medical therapy had failed.

LH versus mini‐LH

Ghezzi 2011 included women with benign gynaecological conditions requiring hysterectomy.

Interventions

Surgical procedures

VH versus AH (five trials)

Five trials compared VH with AH (Benassi 2002; Chakraborty 2011; Miskry 2003; Silva Filho 2006); one included a laparoscopic arm as well (Ottosen 2000). Hysterectomies were performed by standard technique for each route.

LH versus AH (21 trials)

Twenty‐one trials compared LH to AH (Ellstrom 1998; Falcone 1999; Ferrari 2000; Garry 2004; Harkki‐Siren 2000; Hwang 2002; Kluivers 2007; Kunz 1996; Langebrekke 1996; Lumsden 2000; Marana 1999; Muzii 2007; Perino 1999; Raju 1994; Ribeiro 2003; Seracchioli 2002; Sesti 2008a; Schutz 2002; Summitt 1998; Tsai 2003; Yuen 1998). These included four trials that randomised women to LH, AH and VH (Garry 2004; Hwang 2002; Ottosen 2000; Ribeiro 2003). Raju 1994 compared LH and bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy (LH‐BSO) with AH‐BSO. Ellstrom 1998 stratified the two randomised groups (LH and AH) into total and subtotal hysterectomies. Muzii 2007 performed mini‐laparotomy for AH (with a moving surgical field or window using three separate retractors). Sesti 2008a compared LAVH and AH.

LH versus VH (10 trials)

Ten trials included a comparison of laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) with vaginal hysterectomy (VH) (Agostini 2006; Candiani 2009; Darai 2001; Garry 2004; Ghezzi 2010; Richardson 1995; Roy 2012; Sesti 2008b; Soriano 2001; Summitt 1992), including four trials randomising women to LH, AH and VH and including the trial comparing TLH, LAVH and VH. Garry 2004 was a very large RCT comparing LH (called vLH in the trial) with VH and LH (called aLH in the trial) with AH; it was essentially two concurrent RCTs as part of the same study.

RH versus LH (two trials)

Paraiso 2013 and Sarlos 2012 compared conventional laparoscopic to robotically assisted hysterectomy.

SP‐LH versus LH (three trials)

Chen 2011 compared SP‐LAVH versus LAVH, whereas Jung 2011 and Song 2013 compared SP‐LH versus TLH.

LAVH versus TLH (one trial)

Long 2002 compared two types of laparoscopic hysterectomy, which was LAVH versus TLH.

LH versus mini‐LH (one trial)

Ghezzi 2011 compared two types of laparoscopic hysterectomy, which was mini‐LH versus LH.

LH subcategories

Although all the trials used variations of the terms 'laparoscopic‐assisted vaginal hysterectomy' (LAVH) or 'laparoscopic hysterectomy', their definition varied according to what stages of the hysterectomy were completed laparoscopically and the point at which the operation continued vaginally. We included all trials with hysterectomies that had some laparoscopic component in the overall LH category. Using the Richardson 1995 'Staging of laparoscopic hysterectomy' table (see Table 5) we were able to categorise 39 of the 45 included studies that involved LH according to the amount of laparoscopic content. We also subcategorised these trials involving LH as either LAVH, LH(a) or TLH, depending on the extent of the surgery performed either laparoscopically or vaginally (see Table 4). If any trial included women undergoing different Richardson LH stages in the LH arm, we arbitrarily categorised the stage firstly, as the stage to which the surgeons had intended to go; secondly, if that information was not available, to the LH stage that most women underwent surgery; or thirdly, to the most advanced LH stage that women underwent. According to Richardson staging, one trial involved stage zero LH (Ottosen 2000), four trials were stage two (Agostini 2006; Kunz 1996; Marana 1999; Raju 1994), nine trials were stage three (Chen 2011; Ferrari 2000; Muzii 2007; Roy 2011; Roy 2012; Sesti 2008a; Sesti 2008b; Song 2013; Tsai 2003), 10 trials were stage four where the uterine artery was transected laparoscopically (Darai 2001; Ellstrom 1998; Olsson 1996; Persson 2006; Schutz 2002; Soriano 2001; Summitt 1992; Summitt 1998; Yuen 1998; Zhu 2009), and 14 trials were stage five (Candiani 2009; Falcone 1999; Ghezzi 2010; Ghezzi 2011; Harkki‐Siren 2000; Hwang 2002; Jung 2011; Kluivers 2007; Langebrekke 1996; Paraiso 2013; Perino 1999; Ribeiro 2003; Sarlos 2012; Seracchioli 2002). For two trials we were unable to sub‐categorise the LH procedures and we described these as 'non‐categorisable LH' (Chakraborty 2011; Kongwattanakul 2012). Richardson 1995 had LHs of all stages from 0 to 5, and two trials did not stipulate the LH stages performed (Garry 2004; Lumsden 2000). In Long 2002, the LAVH treatment arm was a stage three whilst the TLH arm was a stage five.

Surgeons' experience

The surgeons' experience or level of training was reported in 33 of the trials. Eighteen of these trials specified that the same group of surgeons performed operations for both interventions (Benassi 2002; Candiani 2009; Chen 2011; Ghezzi 2010; Ghezzi 2011; Hwang 2002; Jung 2011; Kongwattanakul 2012; Lumsden 2000; Paraiso 2013; Roy 2011; Roy 2012; Sarlos 2012; Seracchioli 2002; Sesti 2008a; Sesti 2008b; Silva Filho 2006; Song 2013). In seven of these trials, the experience was specified in detail, e.g. in Candiani 2009 at least 50 of both procedures and in Jung 2011 at least 100 LH and 30 SP‐LH. In five trials, surgeons for one intervention were different to those performing the other intervention (Kluivers 2007; Langebrekke 1996; Long 2002; Olsson 1996; Raju 1994). In some trials the surgeons consisted only or partly of residents operating under supervision (e.g. Kluivers 2007; Ottosen 2000; Schutz 2002; Summitt 1998). In five trials specific information on surgical experience was lacking (Agostini 2006; Darai 2001; Falcone 1999; Perino 1999; Zhu 2009).

Outcomes

With respect to our primary outcomes, 16 studies reported on time needed to return to normal activities (Harkki‐Siren 2000; Hwang 2002; Langebrekke 1996; Miskry 2003; Olsson 1996; Ottosen 2000; Paraiso 2013; Persson 2006; Raju 1994; Richardson 1995; Roy 2011; Roy 2012; Sarlos 2012; Schutz 2002; Seracchioli 2002; Summitt 1998).

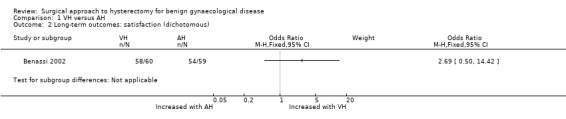

Two studies reported on satisfaction (Benassi 2002; Lumsden 2000), and seven studies reported on quality of life (Garry 2004; Kluivers 2007; Lumsden 2000; Olsson 1996; Persson 2006; Roy 2011; Silva Filho 2006). Song 2013 reported the cosmetic satisfaction after single‐port and multi‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy as primary outcome.

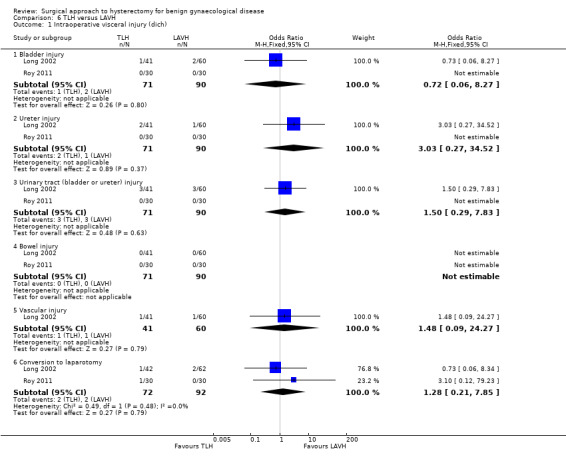

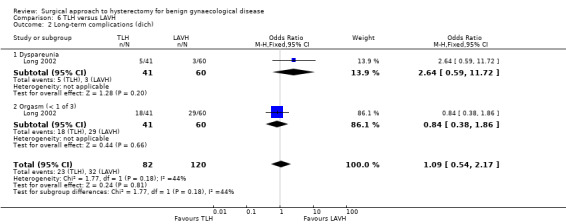

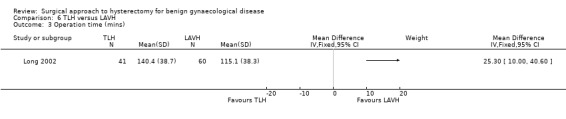

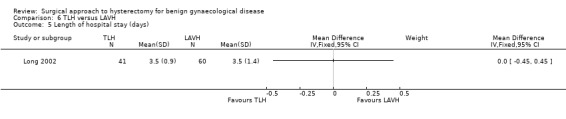

Twenty‐three studies reported on intra‐operative visceral injury (Benassi 2002; Chakraborty 2011; Darai 2001; Garry 2004; Jung 2011; Kluivers 2007; Kongwattanakul 2012; Langebrekke 1996; Long 2002; Lumsden 2000; Marana 1999; Olsson 1996; Ottosen 2000; Perino 1999; Persson 2006; Raju 1994; Ribeiro 2003; Richardson 1995; Roy 2011; Sarlos 2012; Summitt 1992; Summitt 1998; Tsai 2003).

Six studies reported on major long‐term complications (Long 2002; Lumsden 2000; Olsson 1996; Ottosen 2000; Perino 1999; Summitt 1992).

. Forty‐five trials assessed the length of postoperative hospital stay and 10 included an analysis of costs. An assessment of quality of life was reported in 11 trials; four trials included sexual activity or body image in the analysis (Candiani 2009; Garry 2004; Long 2002; Song 2013).

Most of the trials assessed the operation times and intra or postoperative complications. Lumsden 2000 and Garry 2004 split the complications into major and minor. Ellstrom 1998 reported on the difference in erythrocyte volume fraction. Febrile morbidity was measured in 13 trials, pulmonary function in one trial (Ellstrom 1998), and 12 trials reported any operations that were converted to abdominal surgery (Darai 2001; Garry 2004; Kluivers 2007; Marana 1999; Muzii 2007; Ottosen 2000; Persson 2006; Richardson 1995; Seracchioli 2002; Soriano 2001; Summitt 1992; Summitt 1998).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies for an overview of the excluded studies, including the reasons why they were excluded from the review.

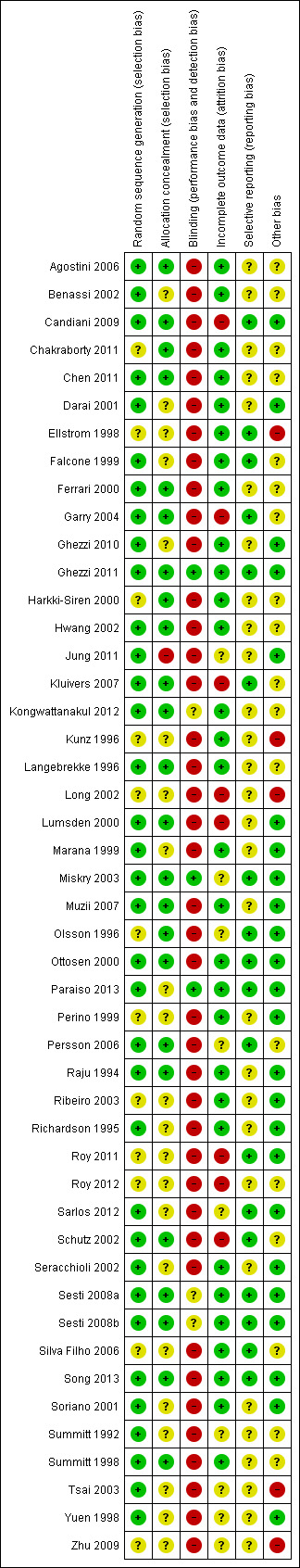

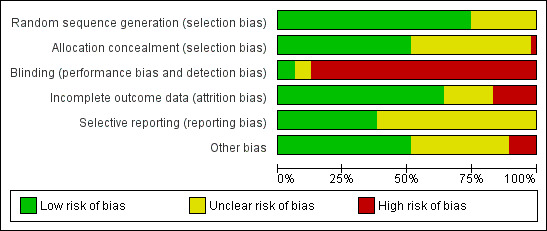

Risk of bias in included studies

An overview of the risk of bias is provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Two studies fulfilled all criteria for adequate management of risk of bias (Ghezzi 2011; Miskry 2003). Several studies fulfilled all criteria, except one (Candiani 2009; Garry 2004; Ottosen 2000; Paraiso 2013; Schutz 2002; Sesti 2008a; Song 2013). Three studies met none of the criteria for adequate management of risk of bias (Long 2002, LH versus LAVH; Roy 2011, TLH versus LAVH versus VH; Roy 2012, LH versus VH; and Zhu 2009, AH versus LH versus VH).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Seventeen studies randomised using a computer (Agostini 2006; Candiani 2009; Chen 2011; Ferrari 2000; Garry 2004; Ghezzi 2010; Ghezzi 2011; Hwang 2002; Miskry 2003; Muzii 2007; Ottosen 2000; Raju 1994; Schutz 2002; Sesti 2008a; Sesti 2008b; Song 2013; Summitt 1998). Langebrekke 1996 and Richardson 1995 used a table of random digits for randomisation. Ten trials used a computer‐generated randomisation code (Benassi 2002; Darai 2001; Falcone 1999; Lumsden 2000; Marana 1999; Seracchioli 2002; Soriano 2001; Summitt 1992; Roy 2012; Tsai 2003; Yuen 1998); one performed randomisation through a computer‐generated randomisation schedule with random block sizes (Paraiso 2013). Eleven trials did not report the randomisation method (Chakraborty 2011; Ellstrom 1998; Harkki‐Siren 2000; Jung 2011; Kunz 1996; Long 2002; Olsson 1996; Perino 1999; Ribeiro 2003; Roy 2011; Zhu 2009). Overall, we considered 35 studies to have low risk of bias and 12 studies to have unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Twenty studies used sealed, opaque envelopes (Agostini 2006; Candiani 2009; Chen 2011; Ferrari 2000; Ghezzi 2010; Ghezzi 2011; Harkki‐Siren 2000; Hwang 2002; Kluivers 2007; Langebrekke 1996; Miskry 2003; Muzii 2007; Olsson 1996; Ottosen 2000; Persson 2006; Raju 1994; Sesti 2008a; Sesti 2008b; Song 2013; Summitt 1998). For instance, Persson 2006 numbered the envelopes according to a random list, and Kluivers 2007 sealed the envelopes after which they were shuffled and numbered by a third party. Two trials used a telephone (Garry 2004; Schutz 2002). Twenty trials did not report whether allocation was concealed (Benassi 2002; Chakraborty 2011; Darai 2001; Ellstrom 1998; Falcone 1999; Jung 2011; Kunz 1996; Long 2002; Lumsden 2000; Marana 1999; Paraiso 2013; Perino 1999; Ribeiro 2003; Roy 2011; Seracchioli 2002; Soriano 2001; Summitt 1992; Roy 2012; Tsai 2003; Yuen 1998; Zhu 2009). We identified no studies as having high risk of bias; in 21 studies it was unclear and 26 studies had low risk of bias.

Blinding

One trial reported sham abdominal dressings until discharge from hospital after VH (Miskry 2003). Another trial comparing mini‐LH and LH covered the incisions with the same size of plasters (Ghezzi 2011). Paraiso 2013 reported blinding of patients for the intervention. In Kongwattanakul 2012 and Sesti 2008a, the researchers were blinded. One trial reported blinding of the interviewer one month after surgery (Silva Filho 2006). All other trials included in this review did not apply any blinding of participants, clinicians or researchers, resulting in high risk of performance and detection bias. Overall, three studies had low risk of bias, three unclear risk of bias and 41 studies high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We considered attrition bias low in 32 trials, unclear in seven trials and high in eight trials.

Dropouts

Twenty‐eight trials reported no dropouts. Nineteen trials reported dropouts, with the dropout rate ranging from 1.7% to 20%. Table 7 lists the trials that reported dropouts with the dropout circumstances. In five trials the dropouts were excluded from the data analysis (Long 2002; Lumsden 2000; Persson 2006; Summitt 1998; Yuen 1998), whereas the other three either included the data in the analysis where possible (Falcone 1999; Kluivers 2007; Paraiso 2013; Sarlos 2012), or performed a sensitivity analysis for the missing data (Garry 2004). Three trials had women withdraw pre‐operatively: Falcone 1999 (4 out of 48), Garry 2004 (34 out of 1380) and Persson 2006 (1 out of 119). In the Lumsden 2000 study, seven women withdrew pre‐operatively and case records were not available for three more. Two and one women respectively refused their assigned procedure in the Summitt 1998 and Kluivers 2007 studies; in the Yuen 1998 study, four women declined their assigned operation and a further two women refused to participate postoperatively. In the Long 2002 trial, excluded post‐randomisation were: three women undergoing conversion to laparotomy, seven with incomplete records and three with combined procedures. A further 53 were excluded because they did not have indications of uterine fibroids or adenomyosis. In the Persson 2006 trial, five patients allocated to AH and one to LH withdrew after giving informed consent prior to the operation or withdrew in the postoperative period before the five‐week follow‐up. In the Paraiso 2013 trial, six patients dropped out before the intervention was performed after randomisation. These were analysed in the allocated intervention arm.

4. Studies reporting dropouts.

| Trial | No. dropouts | Details |

| Chen 2011 | 2 | Excluded from analysis postoperatively, because they underwent accessory adnexal surgery |

| Falcone 1999 | 4 (1 LH; 3 AH) | Withdrew pre‐operatively |

| Garry 2004 | 34 (23 LH (11 aLH; 12 vLH); 6 AH; 5 VH) | Withdrew pre‐operatively |

| Long 2002 | 13 | 3 laparotomy conversions were excluded from analysis; 7 incomplete records; 3 combined procedures that were excluded post‐randomisation |

| Lumsden 2000 | 10 | 10 dropouts were not analysed. 7 women did not attend surgery and 3 records were not available |

| Kluivers 2007 | 1 | Refused assignment procedure |

| Lumsden 2000 | 10 | 7 withdrew pre‐operatively; 3 case records not available |

| Paraiso 2013 | 6 | 6 withdrew after randomisation but before the intervention was performed |

| Persson 2006 | 6 | 5 allocated to AH and 1 to LH withdrew after informed consent prior to the operation or withdrew in the postoperative period before the 5‐week follow‐up |

| Roy 2011 | 9 | 5 excluded because they needed adenectomy during surgery and 4 excluded from all analyses because they did not show up for follow‐up after intervention |

| Roy 2012 | 1 | 1 LH patient excluded from analysis due to conversion |

| Sarlos 2012 | 5 | After randomisation 5 did not complete the study and were excluded from the analysis |

| Song 2013 | 1 | 1 lost to follow‐up because of dissatisfaction with hospital care |

| Summitt 1998 | 2 | Refused assignment procedure |

| Yuen 1998 | 6 | 4 declined operation; 2 refused to participate postoperatively |

AH: abdominal hysterectomy aLH: laparoscopic cases in the abdominal arm of the eVALuate trial LH: laparoscopic hysterectomy VH: vaginal hysterectomy vLH: laparoscopic cases in the vaginal arm of the eVALuate trial

Loss to follow‐up

In eight trials the follow‐up period was not specified (and considered an unclear risk of bias), the number analysed in the follow‐up period was not reported, or the loss to follow‐up was between 5% to 10% of the patient population (Persson 2006; Sarlos 2012; Summitt 1992; Tsai 2003; Yuen 1998; Zhu 2009). Seven studies lost more than 10% of their patient population in the follow‐up period (Candiani 2009; Kluivers 2007; Long 2002; Lumsden 2000; Roy 2011; Roy 2012; Schutz 2002).

Intention‐to‐treat

Twenty‐eight trials reported no dropouts. Of the 19 RCTs reporting dropouts, seven reported analysis by intention‐to‐treat (ITT), defined as all randomised women reported upon according to their group of randomised allocation (Falcone 1999; Garry 2004; Kluivers 2007; Paraiso 2013; Persson 2006; Sarlos 2012; Sesti 2008a). The remaining RCTs reporting dropouts did not report ITT analysis of all randomised women. One further trial that had no dropouts did not analyse by ITT but according to the treatment received, which was different to the assigned treatment in two cases: the operation was converted from LH to AH and these women were analysed in the AH group (Tsai 2003).

Selective reporting

In 29 studies insufficient information was available to determine whether primary or secondary outcomes had been predefined. These studies had therefore an unclear risk of reporting bias. Eighteen studies had low risk of bias. We considered no studies to have a high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged the risk of potential other bias as follows: low risk of bias in 24 studies, unclear risk of bias in 17 studies and high risk of bias (three or more other potential sources of bias) in six studies.

Differences in baseline characteristics

In three studies, baseline characteristics between intervention groups were not comparable (Chakraborty 2011; Hwang 2002), or baseline characteristics were not reported (Kongwattanakul 2012). In Kluivers 2007, the AH group had more residents as a first surgeon than the other two groups. In the other studies no other bias could be identified. In the Long 2002 trial, women were randomised to treatment groups before a large number (i.e. 66) of the women were excluded. Therefore, the women in each treatment group may not have been a true representation of the original randomised groups.

Surgeon's experience

The surgeon's experience or level of training was reported in 30 of the trials and was not considered as a potential source of bias. In the remaining 17 studies the surgeon's experience was not reported or specified or varied substantially between groups. The studies by Benassi 2002, Chakraborty 2011, Chen 2011, Ellstrom 1998, Ferrari 2000, Hwang 2002, Kunz 1996 and Tsai 2003 did not report or specify the surgeon's experience for the interventions evaluated. In five trials, surgeons for one intervention were different to those performing the other intervention: Olsson 1996 (LH carried out by two out of five senior registrar grade surgeons trained in LH, AH carried out by two out of 10 senior registrar grade surgeons trained in AH); Langebrekke 1996 (LH performed exclusively by the two authors, AH performed by any skilled gynaecologist in the department); Raju 1994 (LAVH performed by one of the authors, AH by one of the authors or a senior registrar grade surgeon); Kluivers 2007 (LH was performed or supervised (resident 39%) by three out of 10 experienced gynaecologists (at least 100 LHs), AH performed or supervised by all 10 gynaecologists); and Long 2002 (one surgeon performed all LAVH, another performed all TLH). Residents were the first surgeon in 39% of LH and 88% of AH. In Agostini 2006, the five surgeons were experienced in vaginal surgery but laparoscopic experience was not reported. In Ottosen 2000, 15 gynaecological surgeons with assistants performed the operations; their experience varied and there were cases of residents performing operations under supervision. In Schutz 2002, 71% of LH were performed by the attending physician and 29% by a resident under supervision, and 40% of AH were performed by the attending physician and 60% by the resident under supervision. One trial used only gynaecological residents to perform all the operations with the assistance of the attending physician (Summitt 1998). It is unlikely that any of the latter three trials used the same group of surgeons for both intervention groups. In three other trials it was unclear if the surgeons performing the operations were different: Darai 2001 (all experienced in laparoscopic and vaginal surgery but no mention of who performed each intervention); Perino 1999 (LH by team of three laparoscopic surgeons with experience of more than 100 LHs, no details provided for AH arm); and Falcone 1999 (one of the senior authors performed all the LH operations with the assistance of a pelvic surgery fellow or resident, but no mention of the AH group). In four of the trials, surgeons of all grades and experience carried out the operations. In Garry 2004, each surgeon recruited to the trial had to have performed 25 of each procedure, however cases could be used for teaching if the main assistant was the designated surgeon.

Source of funding

Three studies received funding from pharmaceutical or surgical instrumentation companies: Falcone 1999 received part of the funding from Ethicon Endosurgery Inc; Harkki‐Siren 2000 received a part of its funding from the Research Foundation of the Orion Corporation; Summitt 1998 received all of its funding from US Surgical Corporation, USA.

Other bias

If a trial lacked information, such as a description of one of the interventions or details on the inclusion or exclusion criteria, we considered this a possible source of other bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease.

| Vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with benign gynaecological disease Settings: hospital Intervention: vaginal versus abdominal hysterectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | Vaginal hysterectomy | |||||

| Return to normal activities (days) | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the AH group was 42.7 days | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the VH group was 9.5 lower (12.6 to 6.4 lower) | — | 176 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | — |

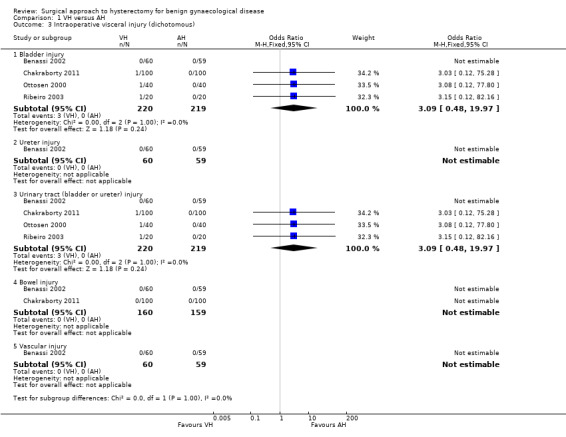

| Urinary tract (bladder or ureter) injury | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 3.09 (0.48 to 19.97) | 439 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | There were no urinary tract injuries in one study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AH: abdominal hysterectomy; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; VH: vaginal hysterectomy | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1There was a large difference in return to normal activities between the different studies; the analysis had high heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) but consistent direction of effect. 2In 2 studies there was doubt about the method used for random sequence generation. 3There were only three events altogether, all in the VH arms.

Summary of findings 2. Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease.

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with benign gynaecological disease Settings: hospital Intervention: laparoscopic versus abdominal hysterectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | |||||

| Return to normal activities (days) | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the AH group was 36.3 days | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the LH group was 13.6 lower (15.4 to 11.8 lower) | — | 520 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | — |

| Urinary tract (bladder or ureter) injury | 10 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (12 to 46) | OR 2.44 (1.24 to 4.80) | 2140 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | — |

| Bowel injury | 7 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 11) | OR 0.21 (0.03 to 1.33) | 1175 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | — |

| Vascular injury | 9 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (5 to 51) | OR 1.76 (0.52 to 5.87) | 956 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | — |

| Bleeding | 16 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (2 to 19) | OR 0.45 (0.15 to 1.37) | 1266 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AH: abdominal hysterectomy; CI: confidence interval; LH: laparoscopic hysterectomy; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1In some studies there was doubt about the method used for random sequence generation or allocation of patients. Furthermore, one study did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis. 2There was a large difference in return to normal activities between the different studies; the analysis had moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 48%) but consistent direction of effect. 3Wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. 4In some studies there was doubt about the method used for random sequence generation or allocation of participants.

Summary of findings 3. Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus vaginal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease.

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus vaginal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with benign gynaecological disease Settings: hospital Intervention: laparoscopic versus vaginal hysterectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Vaginal hysterectomy | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | |||||

| Return to normal activities (days) | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the VH group was 25.2 days | The mean return to normal activities (days) in the LH group was 1.1 lower (4.2 lower to 2.1 higher) | — | 140 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | — |

| Urinary tract (bladder or ureter) injury | 16 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 42) | OR 1.0 (0.36 to 2.75) | 865 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | — |

| Vascular injury | 12 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (6 to 58) | OR 1.58 (0.48 to 5.27) | 745 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | — |

| Bleeding | 29 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (9 to 70) | OR 2.45 (0.38 to 15.78) | 644 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | — |

| Unintended laparotomy | 24 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (19 to 73) | OR 1.55 (0.76 to 3.15) | 1160 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; LH: laparoscopic hysterectomy; OR: odds ratio; VH: vaginal hysterectomy | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. 2In some studies there was doubt about the method used for random sequence generation or allocation of patients. 3Wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. 4In one study it was unclear how participants were allocated to their study group. 5In two studies it was unclear how participants were randomised and allocated.

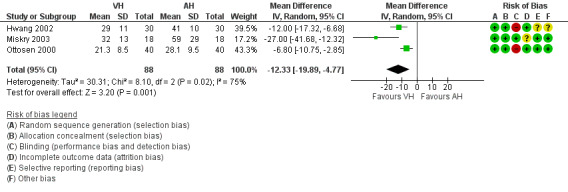

1 Vaginal hysterectomy (VH) versus abdominal hysterectomy (AH)

Primary outcomes

1.1 Return to normal activities

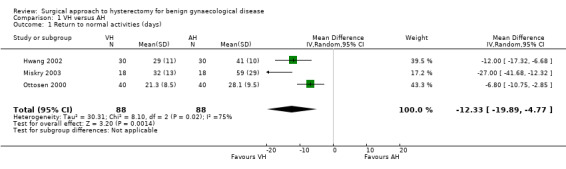

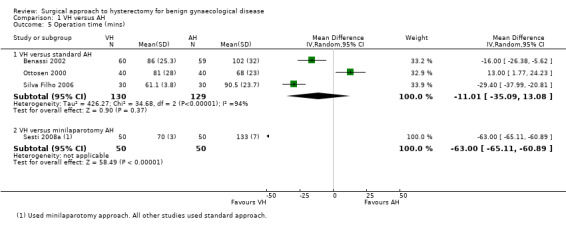

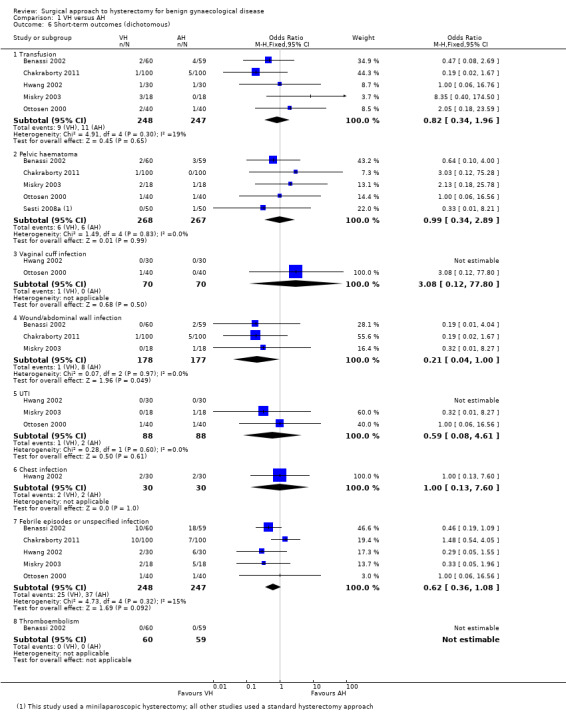

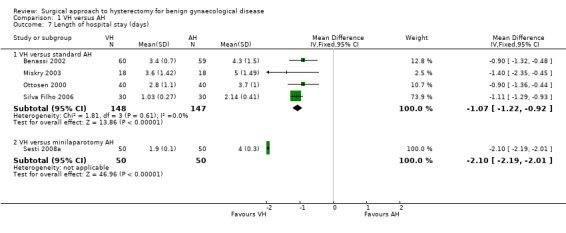

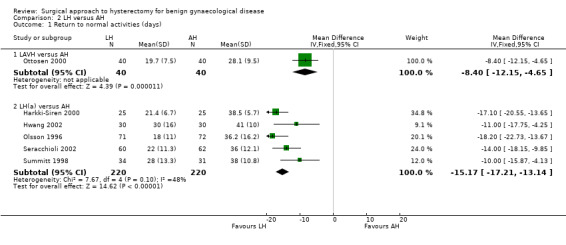

For vaginal versus abdominal hysterectomy, patients returned to normal activities sooner after VH (mean difference (MD) ‐12.33, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐19.89 to ‐4.77; three randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 176 women, I2 = 75%, moderate quality evidence) (Figure 4; Analysis 1.1).

4.