Abstract

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) is one of the autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disorders that shows progressive cerebellar ataxia as a cardinal symptom. This disease is caused by a 2.5- to 3.8-kb-long complex pentanucleotide repeat containing (TGGAA)n, (TAGAA)n, (TAAAA)n, and (TAAAATAGAA)n in an intron of the gene called BEAN1 (brain expressed, associated with Nedd4). By comparing various pentanucleotide repeats in this particular locus among control Japanese and Caucasian populations, it was found that (TGGAA)n was the only sequence segregating with SCA31, strongly suggesting the pathogenicity of (TGGAA)n. The complex repeat also lies in an intron of another gene, TK2 (thymidine kinase 2), which is transcribed in the opposite direction, indicating that the complex repeat is bi-directionally transcribed as noncoding repeats. In SCA31 human brains, (UGGAA)n, the BEAN1 transcript of SCA31 mutation was found to form abnormal RNA structures called RNA foci in cerebellar Purkinje cell nuclei. Subsequent RNA pulldown analysis disclosed that (UGGAA)n binds to RNA-binding proteins TDP-43, FUS, and hnRNP A2/B1. In fact, TDP-43 was found to co-localize with RNA foci in human SCA31 Purkinje cells. To dissect the pathogenesis of (UGGAA)n in SCA31, we generated transgenic fly models of SCA31 by overexpressing SCA31 complex pentanucleotide repeats in Drosophila. We found that the toxicity of (UGGAA)n is length- and expression level–dependent, and it was dampened by co-expressing TDP-43, FUS, and hnRNP A2/B1. Further investigation revealed that TDP-43 ameliorates (UGGAA)n toxicity by directly fixing the abnormal structure of (UGGAA)n. This led us to propose that TDP-43 acts as an RNA chaperone against toxic (UGGAA)n. Further research on the role of RNA-binding proteins as RNA chaperones may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for SCA31.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Ataxia, non-coding repeat, cerebellum, RNA foci, repeat-associated translation, RNA-binding protein, TDP-43, RNA chaperone, Drosophila

Pentanucleotide TGGAA Repeat Is Tightly Associated with Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 31

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) is one of a group of disorders that shows progressive cerebellar ataxia as a cardinal symptom with an autosomal dominant inheritance. This disease was first described when one of us (KI) and his colleagues found their families are mapped to a long arm of chromosome 16 [1]. We mapped the causative gene to chromosome 16q22.1 [2], followed by identification of a single-nucleotide exchange (C-to-T) in the 5′ untranslated region of a gene, PLEKHG4 (also called puratrophin-1) that encodes a protein with a spectrin repeat and Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange-factor domain [3]. However, 2 affected subjects without this single-nucleotide exchange were subsequently found [4, 5], indicating that this is a polymorphism rarely found in Japanese population. In fact, many affected individuals across different families shared many rare variants in the critical 2-megabase chromosomal region. Thus, SCA31 was considered to have a strong founder effect [5]. In support of notion, SCA31 was not found in any other countries except Japan [6, 7]. Fortunately, we were able to narrow down 1 border of the critical region at this C-to-T in PLEKHG4, and the other border at rs11640843 with a recombination among affected individuals demonstrating a new 900-kb critical region [5].

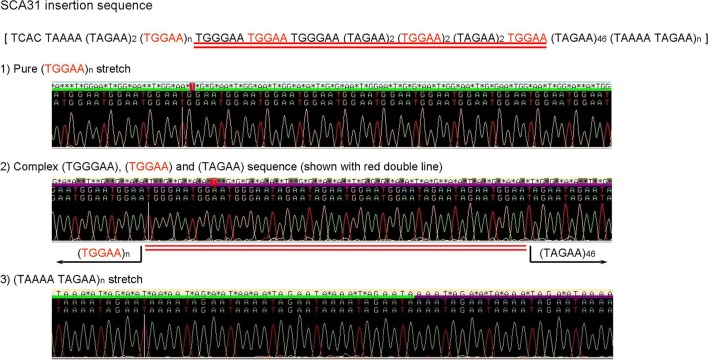

By a tiling search of small rearrangement by Northern blot analysis in conjunction with tiling-path shotgun sequencing of the newly set critical SCA31 chromosomal region in 16q22.1, a mutation shared by all family members with founder chromosomes was found to be a 2.5- to 3.8-kb-long insertion [8]. Cloning and sequencing of this insertion revealed that the internal sequence was a complex pentanucleotide repeat containing (TGGAA)n, (TAGAA)n, (TAAAA)n, and (TAAAATAGAA)n (Fig. 1). The length of this insertion was inversely correlated with the age of onset in SCA31 patients. In contrast, this insertion was not seen in a larger set of control chromosomes with only a few exceptions. The vast majority (99.7%) of Japanese had a short TAAAA repeat of only 8 to 20 repeats. Sequencing the rare, large insertions in control revealed that the internal sequences were different from those in SCA31 subjects: the sequences were either a long pure stretch of (TAAAA)n or a complex repeat with (TAAAA)n, (TAGAA)n, and (TAAAATAGAA)n. The (TGGAA)n was never observed in controls. In addition, presence of TGGAA repeat in SCA31 patients was also replicated in other researchers on different sets of patients [9]. From these observations, (TGGAA)n was the only repeat segregating with the phenotype, suggesting its importance in pathogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Pentapeptide repeat in the SCA31 locus. Reprinted with permission from American Journal of Human Genetics, 68: 355–367, 2009 [8]

The insertion initially appeared to be unrelated to nearby genes, BEAN1 (brain expressed, associated with Nedd4) and TK2 (thymidine kinase 2). However, extensive 3′-RACE experiments revealed that these 2 genes both had multiple downstream exons that had not been deposited in the public databases. This means that the 2.5- to 3.8-kb-long insertion is in an intronic region shared by 2 different genes, BEAN1 and TK2 [8]. Although BEAN1 drives brain-specific expression, TK2 was expressed in all tissues that we examined. As predicted, the TGGAA repeat was transcribed as UGGAA repeat in SCA31 brains.

Identification of SCA31 repeat clarified clinical picture of SCA31. Typical clinical features can be found in some case reports and cohort studies [10–12]. Sakakibara and her colleagues [10] studied 6 SCA31 patients. Their average age of onset was 63.8 years. When compared with their own SCA6 patients, they found that SCA31 patients’ clinical features were much more confined to cerebellar dysfunction, whereas their SCA6 patients showed pyramidal tract signs and psychiatric features besides cerebellar ataxia. Itaya and her colleagues described 1 SCA31 subject who additionally showed blepharospasm [11]. Their patient developed dysarthria at his age of 56. Clinical examination at his age of 58 revealed slight ataxia of the trunk and lower limbs as well as dysarthria and blepharospasm. Magnetic resonance imaging of his brain revealed cerebellar atrophy most pronounced in the upper vermis, which is typical for SCA31. Nakamura and his colleagues collected 44 patients with SCA31 and underwent a 4-year prospective study [12]. They evaluated patients yearly using the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and the Barthel Index (BI). They showed the annual progression of the SARA score was 0.8 ± 0.1 points/year and that of the BI was − 2.3 ± 0.4 points/year (mean ± standard error). Nakamura described that their patients developed ataxic symptoms at 58.5 ± 10.3 years, become wheelchair-bound at 79.4 ± 1.7 years, and died at 88.5 ± 0.7 years. This is the first study to show natural course and disease progression of SCA31.

Founder Effect in SCA31 and Its Implication

As described, the SCA31 shows a strong founder effect. Although SCA31 is a common ataxia in Japan, this disease is very rare even in neighboring countries such as Korea [7], Taiwan [13], and China [14, 15]. SCA31 was found in Brazilian SCA patients; however, these SCA31 patients were all descendants of Japanese immigrants [16]. In accord with this notion, SCA31 with (TGGAA)n was never found in the Caucasian SCA families (n = 320) in French and German cohorts nor in the 588 healthy control subjects [17]. Interestingly, nearly 5.5% of the whole SCA and control groups harbored expansions of different pentanucleotide repeats. The most common repeat was (TACAA)n. Other repeats such as (GAAAA)n, (TGAAA)n, and (TAACA)n were also seen. Unlike the SCA31 insertion consisted of 3 different repeats (TGGAA)n, (TAGAA)n, and (TAAAA)n, the repeats found in Caucasians were all pure stretches. The most common (TACAA)n sometimes showed expansion up to 6.5 kb without clinical manifestation.

This observation indicates 2 things. First, the SCA31 locus in which the vast majority of human beings harbors a short TAAAA repeat (8–20 repeats) can be expanded. The TAAAA can become unstable and expanded as we encountered long (TAAAA)n in Japanese controls. However, all the expanded sequences in Caucasians were all single-nucleotide mutant versions of TAAAA. For example, (TACAA)n is a single A-to-C transition form. Such a mutation may make the SCA31 locus unstable. Second, the TGGAA repeat is the only sequence so far that leads to human disease. Considering that the TAGAA give rise to TGGAA by a single-nucleotide A-to-G transition, it seems likely that the TGGAA repeat, hence SCA31, originates from the TAGAA repeat which has been seen only in Japanese so far.

Neuropathology of SCA31

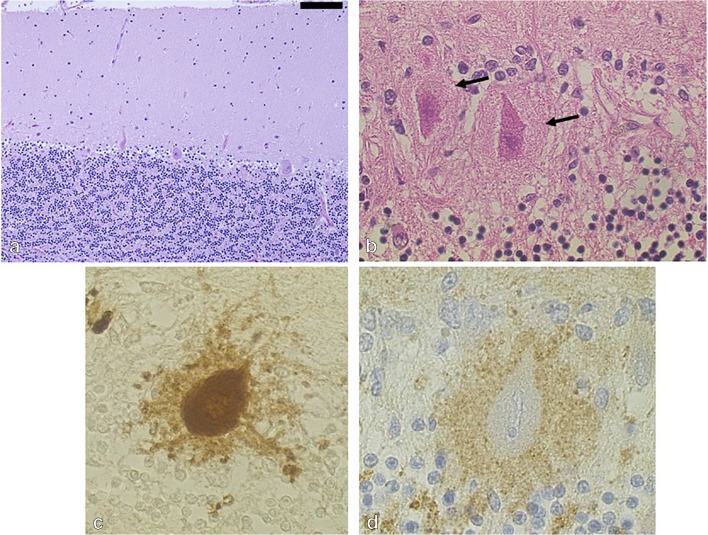

As SCA31 clinically shows progressive ataxia with a purely cerebellar syndrome, and magnetic resonance imaging shows isolated cerebellar atrophy, the neuropathology of SCA31 is expected to be confined to the cerebellar cortex. The first neuropathological study on a 95-year-old female patient who had had SCA31 for 20 years indeed disclosed cerebellar cortical degeneration with Purkinje cell predominant neuronal loss [18] (Fig. 2A). What is very unique to SCA31 was that the Purkinje cell often showed shrinkage of its cell body. In addition, an ill-defined amorphous structure was often seen surrounding the Purkinje cell body [18]. On hematoxylin and eosin staining of the cerebellar tissues, shrunken Purkinje cell body appeared dense pink, whereas the amorphous structure gave pale pink, resembling the halo of the Lewy body in Parkinson’s disease (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemistry against calbindin-D28k, a useful Purkinje cell marker, revealed sprouts form the Purkinje cell body (Fig. 2C), which are infrequently observed in other conditions. The Purkinje cell’s somatic sprout has been described as a pathological hallmark of Menkes’ disease, in which synaptic inputs to the Purkinje cell are known to be dramatically decreased. Although SCA31 is similar to Menkes’ disease in terms of the Purkinje cell’s sprouts, synaptophysin immunohistochemistry disclosed accumulation of presynaptic terminals (Fig. 2D). Thus, the Purkinje cell degeneration in SCA31 appears distinct from that in Menkes’ disease. The structure of the SCA31 Purkinje cell is also different from other ataxias such as SCA6. Ubiquitin-positive inclusions are sometimes seen in the amorphous structure. As this structure was so remarkable, several brain samples with this figure were suspected to be SCA31 and undergone for SCA31 mutation screen, later proven to have SCA31 insertions. One of us (KI) and his mentor, Mizusawa newly coined a word, “halo-like amorphous materials” to this structure as the pathological hallmark of SCA31 [19] (Fig. 2B). As described later in this chapter, the pentapeptide repeat protein specifically translated from the transcript of TGGAA repeat was seen mainly in the amorphous materials.

Fig. 2.

Histopathology of SCA31 patients’ Purkinje cells. (A) A moderate Purkinje cell dropout. Bar = 100 μm. (B) A Purkinje cell body surrounded by the halo-like amorphous materials (arrow). (C) Calbindin-D28k immunohistochemistry. Numerous calbindin-positive somatic sprouts are seen from the Purkinje cell. (D) Increased immunoreactivity against synaptophysin, a presynaptic marker protein, surrounding the Purkinje cell. Reprinted with permission from Neurology. 65: 629–632, 2005. [18]

Yoshida and his colleagues investigated 2 SCA31 brain samples [20]. They not only found the halo-like amorphous materials in their samples, but also found that Purkinje cells surrounded by the amorphous materials tend to show bent, elongated, and often folded nuclei with fragmented Golgi apparatus in the cell soma.

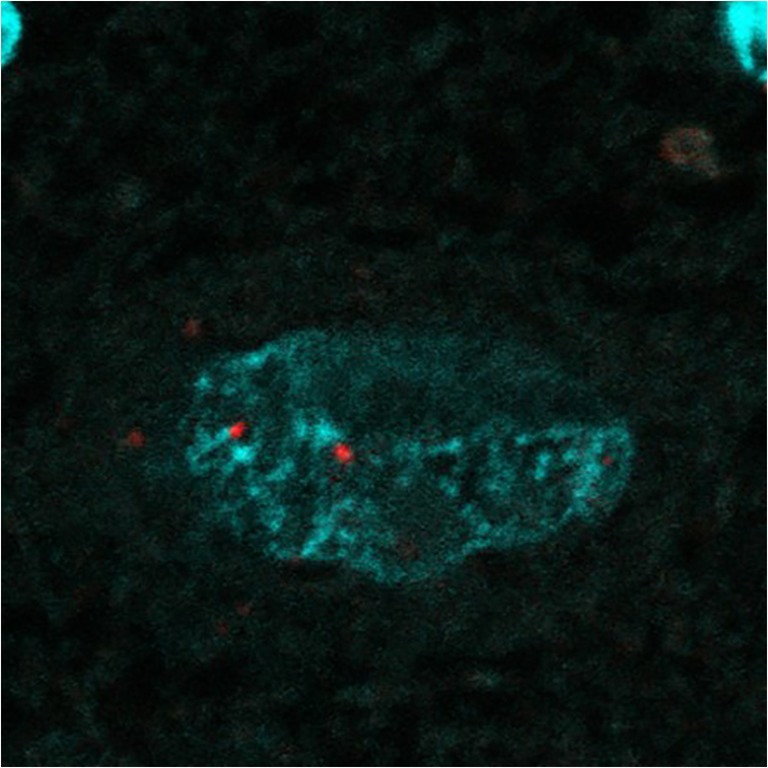

From the genetic observation, the (TGGAA)n transcribed into (UGGAA)n as BEAN1 transcripts has been implicated as an important factor of SCA31 pathogenesis. To gain further insight into the SCA31 pathogenesis, in situ hybridization using RNA probes against (UGGAA)n or (UAGAAUAAAA)n was performed. Yusuke Niimi and his colleagues identified RNA foci within SCA31 Purkinje cells’ nuclei labeled positive with a locked nucleic acid (LNA)-oligonucleotide (TTCCA)5 probe [21] (Fig. 3). Similar RNA foci were also detected by probes against (UAGAAUAAAA)n [21]. They also tested whether (UGGAA)n is toxic than (UAGAAUAAAA)n in cultured cells. They created transient and stable expression cell systems and found that cell toxicity and formation of RNA foci were both consistently observed upon the expression of (UGGAA)n. These observations led us to conclude that (UGGAA)n could be toxic in cells.

Fig. 3.

(UGGAA)n containing RNA foci in human SCA31 Purkinje cell. Reprinted with permission from Neuropathology, 33:600–611, 2013. [21]

Animal Models of SCA31 and Their Implication in the Molecular Pathogenesis and Therapies

Establishment of Drosophila Models of SCA31

To elucidate the molecular pathomechanisms of SCA31, establishing animal models is indispensable. We first tried to establish Drosophila models of SCA31 to express an expanded (UGGAA)n repeat RNA [22], because Drosophila provides a rapid and powerful tool to model human neurodegenerative diseases [23], and Drosophila models of SCA8 expressing (CUG)n repeat RNAs have been successfully established [24]. We first subcloned an SCA31-specific expanded (TGGAA)n repeat followed by complex repeats consisting of (TAGAA)n, (TAAAA)n, and (TAAAATAGAA)n, from SCA31 patients, and established transgenic flies expressing expanded (UGGAA)n repeats (UGGAAexp) RNA under the UAS/GAL4 system. We also designed control transgenic flies carrying complex (TAGAA)n, (TAAAA)n, and (TAAAATAGAA)n repeats that are found in the normal Japanese population.

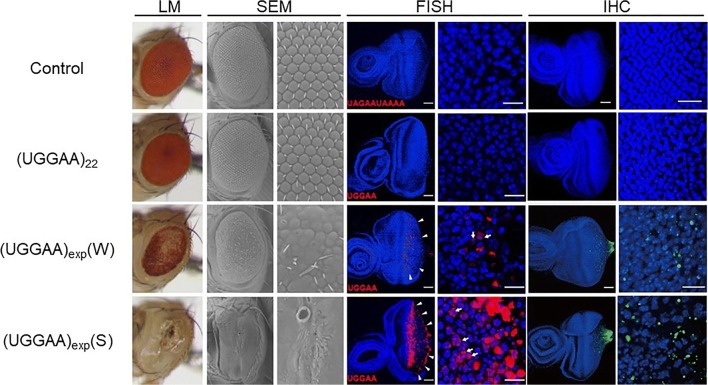

Upon their expression in the compound eyes of flies using the GMR-GAL4 driver, we found that UGGAAexp (80–100 repeats) RNA caused remarkable eye degeneration depending on its expression level, whereas control repeat and short UGGAA22 RNA, which happened to be generated by spontaneous contraction of the TGGAA repeats, had no significant effect (Fig. 4). We next expressed UGGAAexp in the nervous system after the eclosion using the inducible elav-GeneSwitch driver, and found that the expression of UGGAAexp exhibited a shorter lifespan and progressive locomotor defects, while control repeat and UGGAA22 did not. RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed extensive accumulation of UGGAAexp RNA as RNA foci in eye imaginal discs of UGGAAexp-expressing flies (Fig. 4), consistent with the pathology of SCA31 patients [18]. We next examined whether pentapeptide repeat (PPR) proteins are produced by the repeat-associated translation from the UGGAA repeat RNA in flies expressing UGGAAexp. Indeed, PPR proteins were detected by anti-PPR antibodies in eye imaginal discs of UGGAAexp flies depending on its RNA level, whereas no PPR was detected in the UGGAA22 flies (Fig. 4). In human SCA31 cerebellar tissues, we also found PPR protein aggregates mainly in the amorphous materials surrounding the Purkinje cell. From these results, we successfully established Drosophila models of SCA31 showing UGGAAexp-mediated neurotoxicity accompanied by formation of RNA foci and production of PPR proteins, which faithfully recapitulate the pathological features of SCA31 patients [22].

Fig. 4.

Expression of UGGAAexp RNA causes compound eye degeneration accompanied by RNA foci formation and PPR protein production in Drosophila. Light microscopy (LM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of compound eyes, and RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses of eye imaginal discs of flies expressing the control repeats, UGGAA22, or UGGAAexp. UGGAAexp(W): weak expression line, UGGAAexp(S): strong expression line. Reprinted with permission from Neuron, 94(1):108–124.e7, 2017 [22]

Novel Function of TDP-43 as an RNA Chaperone for UGGAA Repeat RNA Aggregation and Repeat-Associated Translation in SCA31 Flies

Considering that proteins sequestered in RNA foci have been reported to play an important role in the pathogenesis of noncoding repeat expansion disorders [25], Sato N. and our colleagues screened for potential UGGAAexp-binding proteins by in vitro RNA pulldown assay using nuclear fraction of PC12 cells. Similar approach using mouse brain lysates was performed by our co-investigators N. Charlet-Berguerand and C. Sellier. Interestingly, several ALS/FTD-linked RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) were identified as UGGAA-binding proteins, such as TDP-43 (TAR DNA-binding protein, 43 kDa), FUS, and hnRNPs. After confirming TDP-43 in the (UGGAA)n-bound protein fraction, we further confirmed co-localization of TDP-43 with RNA foci in human SCA31 Purkinje cells, and thus decided to focus on TDP-43 to analyze its role in the SCA31 pathology [22].

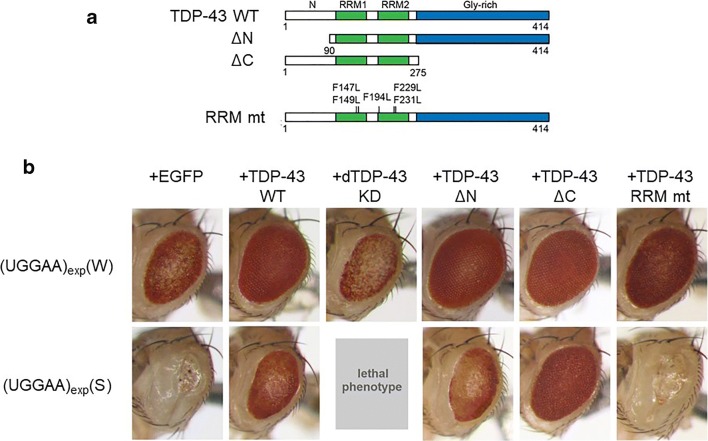

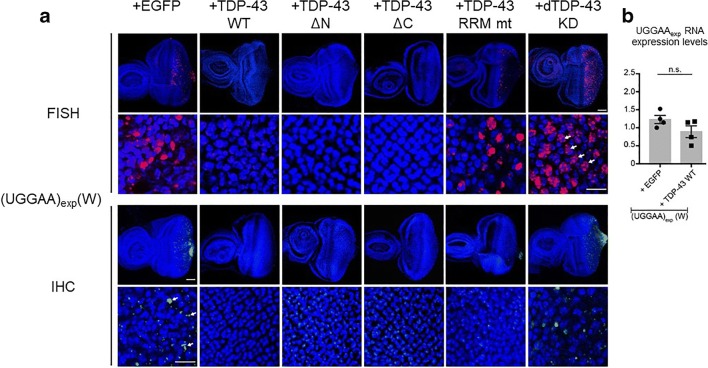

To explore the potential roles of TDP-43 in UGGAAexp-mediated toxicity, we crossed flies expressing UGGAAexp with those expressing human TDP-43. Surprisingly, co-expression of TDP-43 strikingly suppressed compound eye degeneration in the UGGAAexp-expressing flies (Fig. 5). In contrast, RNA interference (RNAi)–mediated knockdown of endogenous Drosophila TDP-43 significantly enhanced eye degeneration in the UGGAAexp flies, indicating a crucial role of TDP-43 in UGGAAexp-mediated toxicity in vivo (Fig. 5). However, TDP-43 carrying mutations in the RNA recognition motif (RRM), which has reduced RNA-binding activity (RRM mutant), failed to suppress UGGAAexp-mediated eye degeneration, further suggesting that the RNA-binding ability of TDP-43 is essential for its suppression of UGGAAexp-mediated toxicity (Fig. 5) [22].

Fig. 5.

Co-expression of TDP-43 suppresses compound eye degeneration in SCA31 flies expressing UGGAAexp RNA via its RNA-binding ability. (a) Schematic diagram of TDP-43 WT, TDP43 mutants with N- or C-terminus-deletion (DN or DC), or RNA recognition motif (RRM) mutations (RRM mt). (b) LM images of compound eyes of flies coexpressing TDP-43 variants or endogenous dTDP43 RNAi with UGGAAexp. Reprinted with permission from Neuron, 94(1):108–124.e7, 2017 [22]

We next examined RNA foci of UGGAAexp RNA by FISH and found that co-expression of TDP-43 significantly reduced the formation of RNA foci in UGGAAexp-expressing flies, whereas co-expression of TDP-43 RRM mutant did not (Fig. 6). RT-PCR analyses confirmed that UGGAAexp RNA expression levels were not altered by co-expression of TDP-43 (Fig. 6), suggesting that TDP-43 does not promote the degradation of UGGAAexp RNA, but rather prevents RNA foci formation, resulting in neutralization of toxic UGGAAexp RNA via their direct interactions. Subsequent circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analyses were done by our colleagues led by C.E. Pearson demonstrated that the binding of TDP-43 to UGGAA repeat RNA alters its structure and prevents its aggregation, indicating that TDP-43 functions as an RNA chaperone for UGGAA repeat RNA [22, 26]. We also examined the repeat-associated translation and found that co-expression of TDP-43 significantly reduced the production of PPR proteins in UGGAAexp-expressing flies (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Co-expression of TDP-43 suppresses RNA foci formation and PPR protein production in SCA31 flies expressing UGGAAexp RNA. (a) RNA FISH and IHC analyses of eye imaginal discs of UGGAAexp(W) flies coexpressing TDP-43 variants, or dTDP-43 RNAi. (b) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of UGGAAexp RNA expression in UGGAAexp(W) flies coexpressing TDP-43. Reprinted with permission from Neuron, 94(1):108-124.e7, 2017 [22]

We also asked whether other UGGAAexp-binding RBPs function as an RNA chaperone for UGGAA repeat RNA, as does TDP-43. Co-expression of FUS or hnRNPA2B1 dramatically suppressed compound eye degeneration in UGGAAexp-expressing flies, as TDP-43 did. Moreover, both FUS and hnRNPA2B1 attenuated the accumulation of RNA foci and the production of PPR proteins without affecting the UGGAAexp RNA expression levels, confirming their functions as RNA chaperones [22]. In contrast, molecular chaperones, such as HSP70 or HSP40, did not affect the eye degeneration in UGGAAexp-expressing flies. Considering that similar therapeutic effects of other RBPs on noncoding repeat expansion disorders have been reported, such as MBNL1 for both CUG repeat in DM1 [27] and CCUG repeat in DM2 [28], hnRNPA2/B1 for CGG repeat in FXTAS [29], we speculate that these RBPs might also function as RNA chaperones to alter the repeat RNA structure.

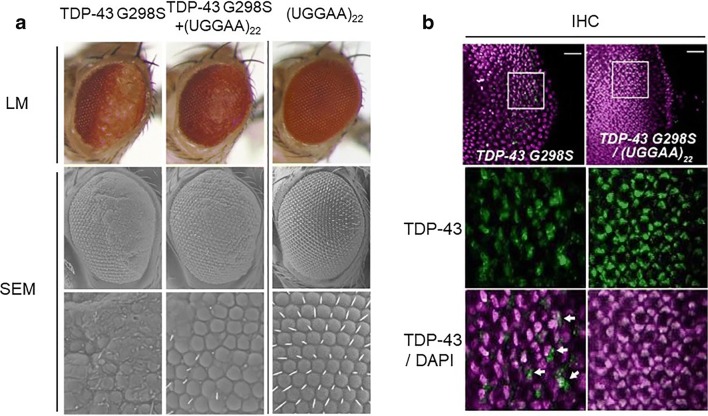

UGGAA Repeat RNA Conversely Suppresses ALS/FTD-Linked RBP Toxicity

Our studies highlighted a novel role of TDP-43, FUS, and hnRNPA2B1 as RNA chaperones for UGGAAexp repeat RNA. On the other hand, aggregations of these RBPs are involved in the pathogenesis of ALS/FTD [30]. Overexpression of TDP-43 in experimental animals has been shown to cause neurodegeneration accompanied by its aggregation [31]. Given that the UGGAA repeat binds with these RBPs, it is possible that RBP toxicity may be ameliorated by binding RNAs. To verify this hypothesis, we crossed flies expressing ALS-linked mutant TDP-43 G298S with the UGGAA22 flies, which do not show any toxicity. Although TDP-43 G298S-expressing flies exhibited considerable compound eye degeneration, co-expression of UGGAA22 significantly suppressed the eye degeneration as well as mutant TDP-43 aggregation (Fig. 7) [22]. This result is consistent with previous reports showing that UG repeat RNA or CLIP34nt RNA which bind to TDP-43 inhibit its aggregation in vitro [32, 33]. We also confirmed that co-expression of UGGAA22 also suppressed compound eye degeneration of flies expressing either FUS or mutant hnRNPA2B1 D290V.

Fig. 7.

Co-expression of UGGAA22 RNA suppresses TDP-43 aggregation and compound eye degeneration in ALS flies expressing TDP-43 G298S. (a) LM and SEM images of compound eyes of flies expressing TDP-43 G298S mutant, UGGAA22, and TDP-43 G298S mutant with UGGAA22. (b) IHC analyses of eye imaginal discs of TDP-43 G298S flies coexpressing UGGAA22. Reprinted with permission from Neuron, 94(1):108-124.e7, 2017 [22]

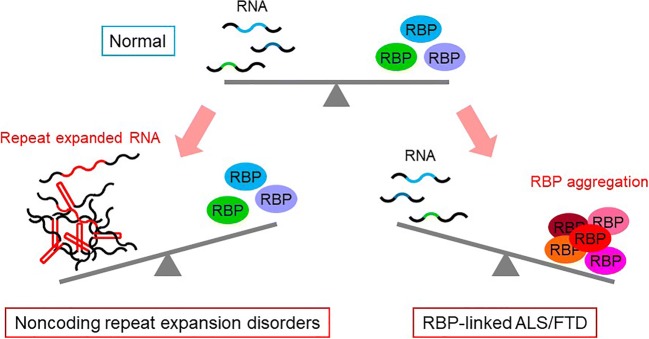

These results reveal that functional cross-talk of the RNA-RBP network regulates their own quality and homeostasis, suggesting that balancing the RNA-RBP cross-talk is a potential therapeutic approach for both noncoding repeat expansion disorders and RBP proteinopathies (Fig. 8) [22]. Our hypothesis that imbalance in the RNA-RBP cross-talk leads to their aggregation is further supported by a recent study demonstrating that RNA buffers the phase separation of RBPs [34].

Fig. 8.

Imbalance between RNA and RBP homeostasis in noncoding repeat expansion disorders and ALS/FTD

Perspectives

Currently, there is no fundamental treatment for SCA31. Therefore, RBP may provide a new idea for SCA31 therapeutics. Toward further elucidating the pathomechanisms of SCA31 and developing its potential therapies, we are now developing mouse models of SCA31. If we indeed see RNA foci containing (UGGAA)n in mouse Purkinje cells, immediate need would be to validate the effect of RBP such as TDP-43 in the mouse Purkinje cell degeneration. Given that the RNA-RBP cross-talk is the case in SCA31 mouse models and also in humans, (UGGAA)n-binding peptide may dampen its toxicity, which may further lead to a development of SCA31 therapeutics. Finally, disturbance of RNA-RBP cross-talk may not be the only possible mechanism of SCA31 pathogenesis. Further studies would be needed to discover mechanisms that (TGGAA)n leads to Purkinje cell predominant neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions, and especially Prof. Hidehiro Mizusawa for the supervision of our study, Dr. Nozomu Sato for cloning SCA31 insertion and identifying UGGAA-binding proteins, and Dr. Taro Ishiguro for the Drosophila study. This work was supported in part by a grant from Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (H.M.) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency; by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Synapse and Neurocircuit Pathology and Brain Protein Aging and Dementia Control) (25110741, 17H05699 to Y.N.) and the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences (Integrated Research on Neuropsychiatric Disorders) (JP15dm0107026 to Y.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan; by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (H.M. and K.I.) and for Scientific Research (C) (B) (K.I.), and for Challenging Exploratory Research (24659438 to Y.N.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Research on Development of New Drugs (H24-Soyaku-Sogo-002 to Y.N.), and on the Research Committee for Ataxic Diseases (H23-Nanchi-014 to Y.N.) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; by a grant for Practical Research Projects for Rare/Intractable Diseases (15ek0109102h, 16ek0109102h, 17ek0109102h, 18ek0109302h to KI; JP16Aek0109018, JP19ek0109222, JP19ek0109316 to Y.N.) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; and by Intramural Research Grants for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders (27-7, 27-9 to Y.N.) from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Mitsubishi Foundation, Natural Science (KI).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nagaoka U, Takashima M, Ishikawa K, et al. A gene on SCA4 locus causes dominantly-inherited pure cerebellar ataxia. Neurology. 2000;54:1971–1975. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li M, Ishikawa K, Toru S, Tomimitsu H, Takashima M, Goto J, Takiyama Y, Sasaki H, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Toda T, Kanazawa I, Mizusawa H. Physical map and haplotype analysis of 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA) type III in Japan. J Hum Genet. 2003;48:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s100380300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa K, Toru S, Tsunemi T, Li M, Kobayashi K, Yokota T, Amino T, Owada K, Fujigasaki H, Sakamoto M, Tomimitsu H, Takashima M, Kumagai J, Noguchi Y, Kawashima Y, Ohkoshi N, Ishida G, Gomyoda M, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Saito Y, Murayama S, Yamonouchi H, Mizutani T, Kondo I, Toda T, Mizusawa H. An autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia linked to chromosome 16q22.1 is associated with a single-nucleotide substitution in the 5′ untranslated region of the gene encoding a protein with spectrin repeat and Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange-factor domain. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:280–296. doi: 10.1086/432518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohata T, Yoshida K, Sakai H, Hamanoue H, Mizuguchi T, Shimizu Y, Okano T, Takada F, Ishikawa K, Mizusawa H, Yoshiura K, Fukushima Y, Ikeda S, Matsumoto N. A 16C>T substitution in the 5’UTR of the puratrophin-1 gene is prevalent in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia in Nagano. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:461–466. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amino T, Ishikawa K, Toru S, Ishiguro T, Sato N, Tsunemi T, Murata M, Kobayashi K, Inazawa J, Toda T, Mizusawa H. Redefining the disease locus of 16q22.1-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:643–649. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edener U, Bernard V, Hellenbroich Y, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Zühlke C. Two dominantly inherited ataxias linked to chromosome 16q22.1: SCA4 and SCA31 are not allelic. J Neurol. 2011;258(7):1223–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee PH, Park HY, Jeoung SY, et al. 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia in a Korean family. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e16–e17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato N., Amino T., and Kobayashi K. et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) is associated with “inserted” pentanucleotide repeat including (TGGAA)n. Am J Hum Genet 68: 355–367, 2009.

- 9.Sakai H, Yoshida K, Shimizu Y, Morita H, Ikeda S, Matsumoto N. Analysis of an insertion mutation in a cohort of 94 patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 from Nagano, Japan. Neurogenetics. 2010;11(4):409–415. doi: 10.1007/s10048-010-0245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakakibara S, Aiba I, Saito Y, Inukai A, Ishikawa K, Mizusawa H. Clinical features and MRI findings in spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) comparing with spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2014;54(6):473–479. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.54.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itaya S, Kobayashi Z, Ozaki K, Sato N, Numasawa Y, Ishikawa K, Yokota T, Matsuda H, Shintani S. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 with blepharospasm. Intern Med. 2018;57(11):1651–1654. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.0068-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura K, Yoshida K, Matsushima A, Shimizu Y, Sato S, Yahikozawa H, Ohara S, Yazawa M, Ushiyama M, Sato M, Morita H, Inoue A, Ikeda SI. Natural History of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 31: a 4-Year Prospective Study. Cerebellum. 2017;16(2):518–524. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YC, Liu CS, Lee TY, et al. SCA31 is rare in the Chinese population on Taiwan. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:426.e23–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouyang Y, He Z, Li L, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 exists in Northeast China. J. Neurol Sci 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Yang K, Zeng S, Liu Z, et al. Analysis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 related mutations among patients from mainland China. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2018;35(3):309–313. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedroso JL, Abrahao A, Ishikawa K, et al. When should we test patients with familial ataxias for SCA31? A misdiagnosed condition outside Japan? J Neurol Sci. 2015;355:206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa K, Dürr A, Klopstock T, et al. Pentanucleotide repeats at the spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) locus in Caucasians. Neurology. 2011;77:1853–1855. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182377e3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owada K, Ishikawa K, Toru S, et al. A clinical, genetic, and pathologic study in a family with 16q-linked ADCA type III. Neurology. 2005;65:629–632. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173065.75680.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa K, Mizusawa H. The chromosome 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (16q-ADCA): a newly identified degenerative ataxia in Japan showing peculiar morphological changes of the Purkinje cell. The 50th Anniversary of Japanese Society of Neuropathology Memorial Symposium: Milestones in Neuropathology from Japan. Neuropathology. 2010;30:490–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2010.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida K, Asakawa M, Suzuki-Kouyama E, et al. Distinctive features of degenerating Purkinje cells in spinocerebellar ataxia type 31. Neuropathology. 2014;34:261–267. doi: 10.1111/neup.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niimi Y, Takahashi M, Sugawara E, et al. Abnormal RNA structures (RNA foci) containing a penta-nucleotide repeat (UGGAA)n in the Purkinje cell nucleus is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 pathogenesis. Neuropathology. 2013;33:600–611. doi: 10.1111/neup.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishiguro T, Sato N, Ueyama M, et al. Regulatory Role of RNA Chaperone TDP-43 for RNA Misfolding and Repeat-Associated Translation in SCA31. Neuron. 2017;94(1):108–124.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueyama M, Nagai Y. Repeat Expansion Disease Models. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1076:63–78. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0529-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mutsuddi M, Marshall CM, Benzow KA, et al. The spinocerebellar ataxia 8 noncoding RNA causes neurodegeneration and associates with staufen in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2004;14:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Echeverria GV, Cooper TA. Brain Res. 2012;1462:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajkowitsch L, Chen D, Stampfl S, et al. RNA chaperones, RNA annealers and RNA helicases. RNA Biol. 2007;4:118–130. doi: 10.4161/rna.4.3.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanadia RN, Shin J, Yuan Y, Beattle SG, Wheeler TM, Thornton CA, Swanson MS. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zu T, Cleary JD, Liu Y, et al. Neuron, 95: 1292–1305.e5, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sofola OA, Jin P, Qin Y, et al. RNA-binding proteins hnRNP A2/B1 and CUGBP1 suppress fragile X CGG premutation repeat-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of FXTAS. Neuron. 2007;55:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nussbacher JK, Tabet R, Yeo GW, Lagier-Tourenne C. Disruption of RNA Metabolism in Neurological Diseases and Emerging Therapeutic Interventions. Neuron. 2019;102(2):294–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budini M, Baralle FE, Buratti E. Targeting TDP-43 in neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18(6):617–632. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.896905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang YC, Lin KF, He RY, et al. Inhibition of TDP-43 aggregation by nucleic acid binding. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann JR, Gleixner AM, Mauna JC, et al. RNA binding antagonizes neurotoxic phase transitions of TDP-43. Neuron. 2019;102:321–338.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maharana S, Wang J, Papadopoulos DK, et al. RNA buffers the phase separation behavior of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Science. 2018;360:918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]