Abstract

In an era of large-scale science-related challenges and rapid advancements in groundbreaking science with major societal implications, communicating about science is critical. The profile of science communication has increased over the last few decades, with multiple sectors calling for such activities. As scientists respond to calls for public-facing communication, we need to evaluate where the scientific community stands. We conducted a unique census of science faculty at land-grant universities across the United States intended to spur the next generation of science communicators and research. Despite scientists’ strong approval of science communication efforts, potential areas of tension, attributable to lack of institutional support and confidence in communication skills, constrain these efforts.

Keywords: science communication, engagement with science, public universities

Many within the scientific community and beyond advocate for reinvigorating the public image of science and promoting engagement efforts between scientists and lay audiences (1). The salience and encouragement of science communication have increased in recent decades, in part to foster trust in and use of science-based decision making within the United State (1). Despite renewed interest in public communication efforts, little systematic work has charted the landscape to date. As a step toward understanding possible shifts within academic culture regarding public engagement, we need a clear picture of scientists’ involvement in, attitudes toward, and abilities to pursue science communication. To begin revealing the landscape, we present results from a unique survey of tenure-track scientists at 46 land-grant universities across the United States.

Based on 6,242 valid responses, we find tenure-track scientists at these institutions strongly approve participation in science communication activities aiming to excite people about science or increase public trust in the scientific community. More importantly, we identify a strong endorsement of interactive objectives, such as learning what people think about specific issues. However, despite support for science communication and engagement, we find potential areas of tension related to the institutional climate identified by these scientists and confidence in their own abilities to adequately conduct such efforts.

In the scientific community, calls for communication efforts emanate from various organizations and researchers, including reports from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (2, 3) and efforts by the Center for Public Engagement with Science and Technology at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Rather than simply promoting the image of science, some argue that public communication efforts should focus on engagement activities that meaningfully involve nonexperts in productive discussions useful to policymaking (4) through “intentional, meaningful interactions that provide opportunities for mutual learning between scientists and members of the public” (AAAS). Additionally, a stream of discipline-specific editorials and journal articles have extolled the value of thoughtful science communication and engagement activities (5).

Often following norms set by colleagues and their institutions, faculty members have traditionally viewed science communication as a peripheral component of their jobs (6). However, there are signs of a cultural shift taking place within academia regarding perceptions and pursuits of public engagement activities (7) as science faculty and their institutions continue to grapple with their involvement in societal debates about science issues and the use of science in policy decision making (8). Coupled with a burgeoning movement within public universities to recommit to service aspects of faculty expectations (8), we may be entering a period of significant reorientation regarding the relationship between academic scientists’ careers and the pursuit of science communication.

A growing body of research in recent years has addressed science communication and academic scientists’ involvement, including factors that promote or inhibit these activities (9–11). Past empirical research on scientists’ public communication efforts has primarily relied on small- or medium-sized convenience or discipline-specific samples of researchers, often recruited through disciplinary or professional organizations. To advance the field, we conducted a large-scale census survey of science faculty at 73 colleges and universities within the US land-grant system endowed by the 1862 and 1890 Morrill Acts. As recipients of public funding steeped in founding traditions of public service and impact (12), land-grant universities should be strong supporters of science communication and encourage direct and meaningful engagement with their constituents and society.

Using university websites, a research team compiled contact information for all 100,000+ land-grant faculty and invited them to participate in a science communication survey conducted from May to June 2018, yielding 10,706 completed surveys and a 14.1% response rate (RR2). The project was reviewed and exempted by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (ID: 2018-0432). We initially contacted faculty at 73 institutions, but only 46 institutions were included in the final sample after removing those with fewer than 20 completed surveys or that were not representative of their faculty gender distribution. Narrowed to tenured and tenure-track social, life, and physical scientists, our results use a final sample of 6,242 scientists. The census-type approach avoids convenience sampling issues plaguing prior studies in the field, although self-selection into the study (e.g., active communicators may be more inclined to respond) remains a known challenge. A response wave comparison suggests we reached different segments of the faculty population, based on tenure status and outreach involvement, with less active communicators responding later in the survey period. Although census methodology does not require formal testing, we include P values to assist interpretation of findings.

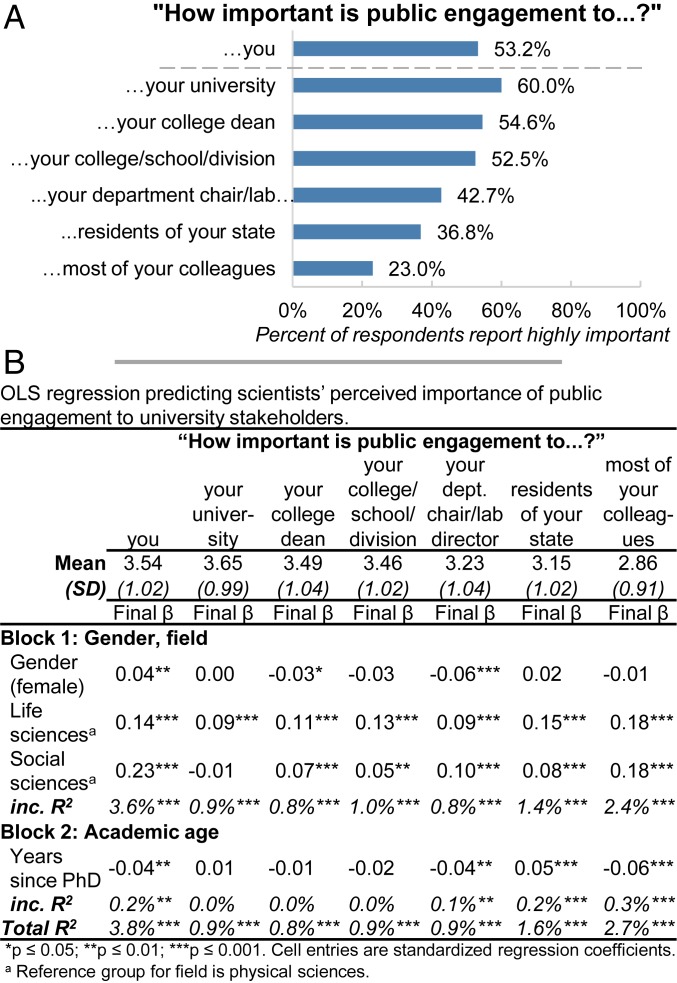

Our results reveal a complex landscape of public communication among land-grant science faculty. Faculty reported high levels of activity in public outreach: 98.3% of respondents participated in at least one science communication activity over the year, with 80.6% of respondents engaged in adult-focused activities (e.g., science cafés or deliberative forums). A majority (53.2%) indicated that pursuing public engagement activities is highly important to them, with younger science faculty (based on academic age, or years since PhD) placing significantly higher importance on such activities (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Perceived importance of public engagement. (A) Percentage of scientists rating public engagement as highly important (“very” or “extremely”) to the university stakeholders. (B) Ordinary least-squares regression predicting perceived importance of engagement. Compared to their colleagues, younger career scientists were more likely to rate engagement as more important for themselves, their chairs, and their colleagues. (Importance measured on 5-point scale: 1, “not at all”; 2, “slightly”; 3, “moderately”; 4, “very”; 5, “extremely.”)

Faculty’s reported participation and importance might suggest a supportive climate for science communication, yet their perceptions of the culture surrounding public engagement at their institutions expose areas of tension. Asked about the importance placed on engagement by key university-related groups, faculty indicated they received inconsistent messages from different sectors and leaders (Fig. 1A). Under one-half of respondents (43.0%) thought high-level administrators had made public engagement a priority at their institutions, contributing to a perceived lack of institutional support. More immediately, faculty respondents believed public engagement was not important to their colleagues (23.0% thought it was highly important), and only around one-half (55.6%) thought scientists who participate in science communication are well regarded by their peers, leaving a substantial 37.4% undecided about their high engagement peers. Critically, faculty did not believe that engagement was important to residents of their community (only 36.8% thought it was highly important). Viewing public engagement as relatively unimportant to colleagues, certain university leaders, and state residents may suppress engagement efforts, or at least scientists’ willingness to share their involvement.

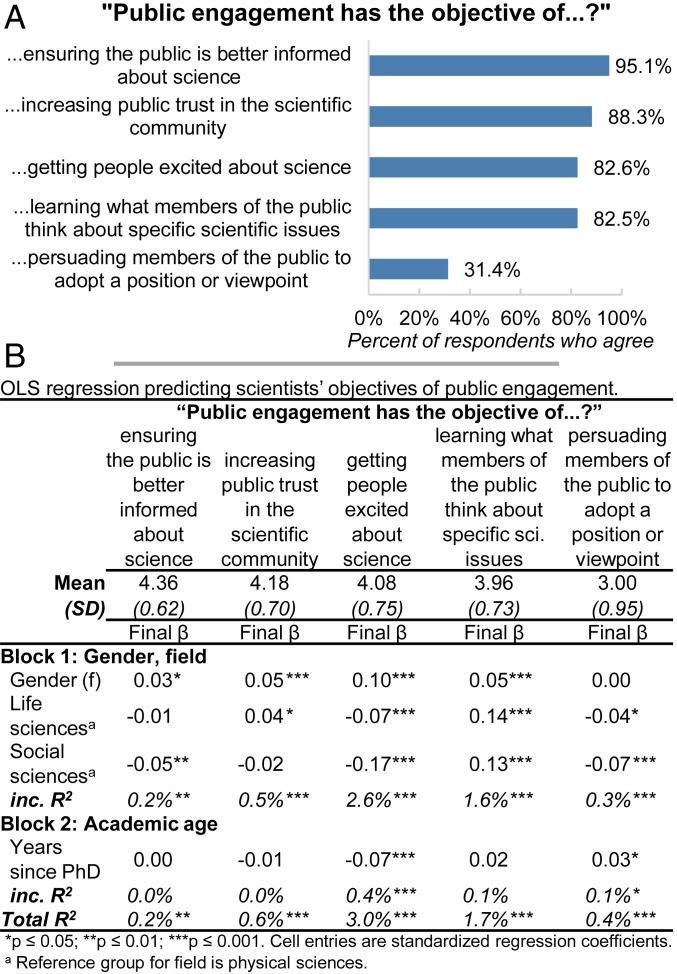

Participation in science communication may be stimulated, at least in part, by shifting views of the objectives of public engagement rather than institutional support (Fig. 2A). Departing from traditional views of outreach (to inform and persuade nonexperts), respondents strongly endorsed more holistic, interactive objectives: “getting people excited about science” (82.6% agreement), “increasing public trust in the scientific community” (88.3% agreement), and “learning what members of the public think about specific issues” (82.5% agreement). Mixed support (31.4% agreement; 37.1% unsure) remains for a deficit approach to science communication based in persuasion. Support for these objectives varied by gender: female scientists were more supportive of holistic objectives, but not of persuasion. Additionally, we find evidence that scientists earlier in their careers view engagement more as a way to get people excited about science and less to persuade them (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Objectives of public engagement. (A) Percentage of scientists agreeing (“agree” or “strongly agree”) with the objectives of public engagement. (B) Ordinary least-squares regression predicting scientists’ agreement with public engagement objectives. Younger career scientists saw engagement as getting people excited about science rather than persuading, compared to their colleagues. Female scientists were consistently more supportive of each objective than their male colleagues, except for persuasion. (Agreement measured on 5-point scale: 1, “strongly disagree”; 2, “disagree”; 3, “neither disagree nor agree”; 4, “agree”; 5, “strongly agree.”)

Science faculty members, then, believe science communication is important and embrace more engaged and public-minded goals and approaches. However, what do these faculty think of their own communication skills? Respondents with past engagement experience saw positive outcomes for themselves as audiences gave them “food for thought” (82.0% agreement). Perhaps reflecting overconfidence in their skills (13), 62.1% of scientists felt it was easy to adjust to different audiences and 66.8% thought it was easy to explain scientific facts to lay audiences. However, many still found these tasks difficult or were unsure. Of greater challenge was managing critical objections from audiences (27.0% of respondents finding it difficult and 31.1% unsure).

Our results suggest land-grant university scientists’ own attitudes toward public communication are broadly supportive of more inclusive and productive efforts in this domain, with even higher levels of support among the next generation of scientists. Scientists’ views of whether their peers, university administrators, and constituents value science communication, however, suggest these efforts occur despite a perceived lack of institutional and collegial support. That many faculty feel unsupported at these institutions indicates scientists, and perhaps especially younger faculty, face an uphill battle in pursuing the critical work called for by so many.

Scientists’ public communication efforts will play an increasingly important role in shaping perceptions and support for science and public institutions, particularly as scientists and universities redefine and defend their roles in American society. To achieve this, scientists participating in communication efforts require support from their institutions and communities. In this changing environment, a small but increasing recognition for service and public engagement exists within the academic community (14). As vitally important as institutional support, scientists must consider the science of science communication and use insights from the social sciences to inform sound science communication practices (1). Future research should address how institutions can support and encourage faculty communication efforts. Science communication impacts its participants—scientists and nonexpert members of the public—but as these efforts expand, our expectations of the purposes, outcomes, and rewards should evolve, both in the public sphere and the halls of academia. Science and the world change rapidly, and so must we.

Data Availability.

Additional information on the survey protocol and robustness checks are in the project report (https://uwmadison.box.com/v/LGProject-MethodsReport). The data are available in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Morgridge Institute for Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1916740117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , Human Genome Editing: Science, Ethics, and Governance (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson A. A., Brossard D., Scheufele D. A., Xenos M. A., “Online talk: How exposure to disagreement in online comments affects beliefs in the promise of controversial science” in Citizen Voices: Performing Public Participation in Science and Environment Communication, Phillips L., Carvalho A., Doyle J., Eds. (Intellect, Chicago, 2012), pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jefferson A. J., Kenney M. A., Hill T. M., Selin N. E., Universities can lead the way supporting engaged geoscientists. Eos 99, 2018EO111567 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land Grant Universities , Returning to Our Roots: The Engaged Institution (National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges, Washington, DC, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin S. M., Jaeger A. J., O’Meara K., The state of community engagement in graduate education: Reflecting on 10 years of progress. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 20, 151–156 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman A. J., et al. , Academic Engagement in Public and Political Discourse: Proceedings of the Michigan Meeting, May 2015 (Michigan Publishing, Ann Arbor, MI, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nisbet M. C., Markowitz E. M., Expertise in an age of polarization: Evaluating scientists’ political awareness and communication behaviors. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 658, 136–154 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudo A., Besley J. C., Scientists’ prioritization of communication objectives for public engagement. PLoS One 11, e0148867 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besley J. C., Dudo A., Yuan S., Lawrence F., Understanding scientists’ willingness to engage. Sci. Commun. 40, 559–590 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDowell G. R., Land-Grant Universities and Extension into the 21st Century: Renegotiating or Abandoning a Social Contract (Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cross K. P., Not can, but will college teaching be improved? New Dir. Higher Educ. 1977, 1–15 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alperin J. P., et al. , How Significant Are the Public Dimensions of Faculty Work in Review, Promotion, and Tenure Documents? (Humanities Commons, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional information on the survey protocol and robustness checks are in the project report (https://uwmadison.box.com/v/LGProject-MethodsReport). The data are available in SI Appendix.