Abstract

We report results from a large qualitative study regarding the process of parents coming to understand the child has autism starting from the time of initial developmental concerns. Specifically, we present findings relevant to understanding how parents become motivated and prepared for engaging in care at this early stage. The study included primary data from 45 intensive interviews with 32 mothers and 9 expert professionals from urban and rural regions of Ontario, Canada. Grounded theory methods were used to guide data collection and analysis. Parents’ readiness (motivation and capacity) for engagement develops progressively at different rates as they follow individual paths of meaning making. Four optional steps account for their varied trajectories: forming an image of difference, starting to question the signs, knowing something is wrong, and being convinced it’s autism. Both the nature of the information and professional help parents seek, and the urgency with which they seek them, evolve in predictable ways depending on how far they have progressed in understanding their child has autism. Results indicate the need for sensitivity to parents’ varying awareness and readiness for involvement when engaging with them in early care, tailoring parent support interventions, and otherwise planning family-centered care pathways.

Lay Abstract

What is already known about the topic?

Parents of children with autism often learn about their child’s autism before diagnosis and can spend long periods seeking care (including assessment) before receiving a diagnosis. Meanwhile, parents’ readiness to engage in care at this early stage can vary from parent to parent.

What this paper adds?

This study revealed how parents come to understand their child has autism—on their own terms, rather than from just talking to professionals. It also explained how parents’ growing awareness of their child’s autism leads them to feel more motivated to engage in care by seeking information and pursuing services. Four “optional steps” described how parents’ growing readiness to engage in care at this early stage can vary, depending on their personal process.

Implications for practice, research, or policy

The results suggest ways that professionals can be more sensitive (a) to parents’ varying awareness of autism and (b) to their varying readiness for being involved in early care. They also suggest ways to tailor parent supports to their individual situation and design care that is more family centered. Not all parents want high levels of involvement. Depending on their personal process, some parents may need care and support that is directed at them before feeling ready for professionals to engage them in care directed at the child.

Keywords: caregiver, family-centered care, grounded theory, patient engagement, patient-centered care, pre-diagnosis

In response to the growing emphasis on family-centered care models, autism service providers internationally are increasingly involving parents and caregivers in the planning and delivery of intervention and services. In Ontario, Canada, for example, guidance for implementing the province’s Autism Program encourages active family engagement in service planning to promote individualized family-centered services (ASD Clinical Expert Committee, 2017). In addition, there is a growing prominence of parent-mediated intervention models that involve training caregivers to deliver naturalistic, developmental, behavioral intervention (NDBI) at high intensity throughout the child’s day, requiring substantial caregiver time, energy, and commitment (Schreibman et al., 2015)—some for young children whose diagnosis is not yet confirmed (Brian, Smith, Zwaigenbaum, Roberts, & Bryson, 2015). Such parent involvement is theoretically desirable because it potentially increases effectiveness by capitalizing on parents’ expert knowledge of the child and their ability to generalize behaviors and skills beyond the clinic to the child’s everyday life. Furthermore, by reducing intensity and cost of therapist involvement, public systems can distribute scarce resources to benefit more parents. Within such care models, however, parents are being asked to be involved earlier, often close to diagnosis, when emotional (Davis & Carter, 2008; Osborne, McHugh, Saunders, & Reed, 2008) and work-related (Singh, 2016) burdens are known to be especially high. Insisting on high levels of engagement for all parents at this early stage may have unintended consequences on a subset of those who are not ready to meet the additional demands placed on them, exacerbating parenting stress, which can in turn reduce intervention effectiveness (Osborne, McHugh, Saunders, & Reed, 2007, 2008) and be a barrier to achieving optimal outcomes for the family and child (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2000; Reed & Osborne, 2012).

More specific qualitative understanding of the mechanisms explaining parents’ varying levels of readiness for engagement could facilitate incorporating greater sensitivity in planning or implementing family-centered care models, especially for those parents just entering care systems who have minimal prior exposure to autism. In addition, such knowledge may be conceptually useful for developing autism-specific tools to assess parents’ psychosocial functioning and support needs, the need for which is described elsewhere (Reed & Osborne, 2012; Zaidman-Zait, 2018).

In the case of autism, parents sometimes learn about their child’s condition before diagnosis and commonly pass through a prolonged process of seeking care that precedes it. According to a recent UK survey, for example, parents first noticed developmental concerns in 96% of cases, and the interval from first concern to diagnosis averaged 4.6 years (Crane, Chester, Goddard, Henry, & Hill, 2016). This pre-diagnosis interval comprises two smaller intervals: the time from first noticing concerns to the first clinical encounter and the interval from parents’ first clinical encounter to address developmental concerns to final diagnosis, often called the diagnostic process. Several studies have noted parents’ general sense of uncertainty and need for answers at this pre-diagnosis stage (e.g. Carlsson, Miniscalco, Kadesjö, & Laakso, 2016; Midence & O’Neill, 1999). Additional research indicates how, by the time of diagnosis, parents (a) can feel overwhelmed by and yet have varying needs for information (e.g. Osborne & Reed, 2008) and (b) have different personal support needs (e.g. Carlsson et al., 2016; Legg & Tickle, 2019). Both illustrate the need for sensitivity to parents’ varying readiness for engagement in care at early stages.

Much of the literature on parents’ pre-diagnosis experience presents findings with reference to the clinical diagnostic process, which inevitably varies by jurisdiction (e.g. consider differences between Sweden and the United Kingdom: Carlsson et al., 2016; Crane et al., 2016). Focus on this clinical process is unlikely to fully account for the parent’s social psychological process, which is only partly defined by clinical interactions. We have argued previously (Gentles, Nicholas, Jack, McKibbon, & Szatmari, 2019) that parents’ actions of engaging in autism-related care, including their path to diagnosis, are best understood by focusing on the meanings they attribute to aspects of their broader personal situation or lifeworld (Barry, Stevenson, Britten, Barber, & Bradley, 2001), which exists predominantly outside clinical settings. We are unaware of prior research that provides theoretical knowledge from a lifeworld perspective of the natural process by which caregivers initially (often pre-diagnosis) become ready and motivated to engage in care at an individual level.

Here, we provide a detailed qualitative account of the process of parents coming to understand their child has autism starting from the time of first concern, with a specific focus on aspects that explain how parents become socially and psychologically engaged in care at the earliest stages of their journey. This is the second substantive report from a large qualitative study whose broader aim was to explain how Ontario parents of children with autism navigate autism-related intervention and care over much of the lifespan—spanning milestones from pre-diagnosis to preparing for adulthood (Gentles et al., 2019). In that initial report, we elaborated the overall theory with a focus on engagement in care at a more general level across their long-term navigating journey. Notably, the part of parents’ journey for which data were most densely available was the initial phase. This report thus serves to further develop that broad theory of engaging in autism-related care by elaborating on what was the most developed and informative example from the study: the mostly pre-diagnosis process of coming to understand the child has autism. We present this example to illustrate in-depth several key aspects of parents’ evolving motivation and readiness for engagement and promote greater clinical understanding when involving them at this early phase of the diagnostic process.

Importantly, while this report is intended to inform clinical support for families, rather than focus on caregivers’ experience of the clinical pathways and interactions leading to diagnosis (e.g. Boshoff, Gibbs, Phillips, Wiles, & Porter, 2018; Ho, Yi, Griffiths, Chan, & Murray, 2014), it addresses parents’ independent process of reaching personal certainty of their child’s autism, stemming from their lifeworld interactions, clinical and otherwise. Here, we define both engagement and care according to the person-centered perspective of the overall study (Gentles et al., 2019): engagement is a parent’s “readiness and motivation at a given point in time to be involved in [personally] navigating intervention to address a [personally-defined] health concern” (p. 6), while care is defined according to how parents broadly defined intervention, “as any therapy, service, or modification a parent or care professional considers using to address an autism-related concern” (p. 3). Here, concerns are defined as being from the parent’s perspective and include any circumstance or condition attributable to their child’s autism (e.g. signs, comorbid conditions) that they perceive as sufficiently problematic to motivate taking personal action to address (p. 7).

Methods

Ethics approval for human research (HHS/McMaster REB, 11457) and written consent from all participants was obtained. We conducted 45 in-depth interviews (four participants completing two interviews) with 32 mothers (while only mothers were invited, fathers co-participated in three cases) and 9 professionals with experience supporting parents. Select documents were also reviewed including books from parent and professional perspectives, books or movies mentioned by parents, and participant-referenced web sites; these secondary sources provided educational and contextual background, and typed notes taken on them were coded and used in analytic memos. Participants were purposefully selected from diverse sources across Ontario, capturing maximally varying demographic perspectives and experiences (Gentles et al., 2019). Professionals were purposefully selected for their long-standing commitment and empathy supporting parents and could thus share crosscutting observations and examples from extended experience. While little professional data are cited directly here, professionals contributed substantively by helping confirm and refine analytic interpretations that had been developed toward the end of data collection (as did several parents who similarly participated in late-stage interviews). Importantly, secondhand interpretations of parents’ experience and action needed to be transparently supported by credible examples or data for inclusion in the analysis.

Grounded theory methods were used to guide concurrent iterative data collection and analysis (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Theoretical sampling was used to inform ongoing data collection by selecting examples of important categories to be developed, often by asking new questions in interviews (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Gentles, Charles, Ploeg, & McKibbon, 2015; Glaser, 1978; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Parents completed an initial phone survey to collect demographic and other pre-specified data, and all participants completed 90-minute intensive qualitative interviews face-to-face or by phone, which were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Following a flexible interview guide, participants were asked about experiences and actions navigating intervention from the time parents first noticed developmental signs—including secondary reports about fathers’ experiences and actions (in the three dyad interviews, the father’s roles were discussed openly by both parents). Notably, all parents provided valuable data about coming to understand their child had autism. Analysis featured constant comparison used in coding and category development, analytic memo writing, conceptual diagrams, and integrative writing, all done to consistently promote analytic depth and ensure findings were grounded in primary participant data.

We used the social theory of symbolic interactionism as an explicit framework, structuring the analysis according to parents’ meaning making and action/interactional processes (Blumer, 1969). Thus, rather than portray behavior (which implies an observer perspective, ignorant of actors’ inner worlds and motivations), we instead sought to understand and portray parents’ first-person action, including the meaning-making that underlies and explains it. As such, parents invariably were interpreted as the experts in their unique situations, and their actions navigating intervention (engaging in care) were not judged by outside standards. It is important to note here that throughout we use the word problematic in a symbolic interactionist sense to refer to aspects of parents’ perceptions or ideas about the things in their situation (e.g. child behaviors, signs) that motivate them to consider one or more lines of action to bring about some kind of change; the word is never used to describe any participant’s broad orientation or attitude to autism (e.g. as fundamentally negative or undesirable)—indeed, by the time of interview, most parents communicated an accepting understanding of autism, which they perceived as essential to who their child was.

Reporting procedures that crosslink participant data (e.g. using pseudonyms) have been avoided in this report to maintain privacy (Morse & Coulehan, 2014). Every participant provided substantive data that were used in the analysis or writing, and the data presented here (quotes, attributable narrative descriptions) originate from a variety of participants (i.e. no one participant’s data dominates). Quantitative descriptors (e.g. multiple, several, a majority) have been verified with the data as referring to proportions of participants in this sample and may not be representative of the population. Member checking was achieved in a manner consistent with grounded theory by gauging participants’ reactions about coherence of the analysis with parent experience and where there was coherence, directing subsequent discussion to generate new properties of those categories (Charmaz, 2006, p. 111). A detailed account of reflexivity methods and the primary researcher’s (S.J.G.) position and identity as a non-clinician is published elsewhere (Gentles, Jack, Nicholas, & McKibbon, 2014); briefly, self-awareness was used to prioritize parents’ perspectives and minimize effects of researchers’ backgrounds on the analysis. Data management and analysis were supported by software (NVivo 10; QSR). By prioritizing first-hand and person-centered perspectives, the methodological approach supported identifying relevant factors and mechanisms underlying individual-level processes like engagement (as defined above). Further details about the study are freely accessible (Gentles et al., 2019).

Results

Parent participant characteristics

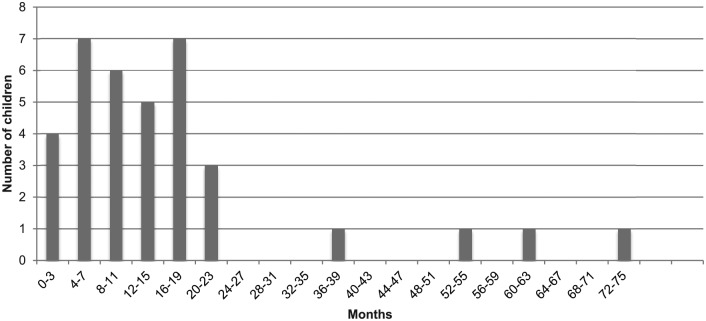

The 32 parent participants represented varied experiences including diverse rural (22%) and urban (78%) regions of Ontario, child ages (range 2.5–18 years), number of children with autism (up to 5), ethnocultural backgrounds, and experience navigating intervention at the time of interview (range: 1–9 years; Gentles et al., 2019). Median age at diagnosis was 36 months (range: 20–126 months), and median age at first concern was 23 months (range: 7–73 months). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the intervals from first concern to diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of intervals from first concern to diagnosis (36 children of 32 parents).

Location within the broader theory of navigating intervention

Previously (Gentles et al., 2019), we described four inter-related meaning-making processes that explain parents’ actions of navigating and engaging in autism-related intervention and care: informing the self, seeing what is involved, adapting emotionally, and defining concerns—defined in Table 1. The process of coming to understand the child has autism outlined in depth in the following section is a significant example of the process of defining concerns. Here, parents specifically define the overarching developmental concern of autism itself (although parents often also define other more specific concerns, pre-diagnosis, for example, speech problems).

Table 1.

Four meaning-making processes relevant to parents engaging in autism-related intervention and care and manifestations pre-diagnosis.

| Process | Description (Gentles, Nicholas, Jack, McKibbon, & Szatmari, 2019) | Relevant pre-diagnosis manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Defining concerns | Perceiving issues related to autism as problematic, and ultimately concerning enough to motivate them to want to take action to address; concerns are thus the impetus for action related to engaging in care; they can be general, like the child’s long-term happiness, or specific, like functional speech | • Coming to understand the child has autism |

| Informing the self | Obtaining and internalizing information through reflective experience, observation, or seeking or passively receiving information from a variety of sources (professionals, social acquaintances, the child with autism, books, Internet, etc.) to develop knowledge and understanding about a concern or about options for addressing it. | • Re how to identify autism

• Re what to expect with autism • Re what to do first about autism |

| Adapting emotionally | Responding internally by successfully adapting to the emotionally difficult implications parents may define their situation as having for themselves or their child; success generally prepares and motivates parents for engaging in care. | • Accepting the possibility of autism

• Releasing culturally based hopes and expectations for the child’s future • Accepting an uncertain and frightening future for the child • (See Gentles et al., 2019 for aspects relevant at later stages) |

| Seeing what is involved | Experiencing the work involved in, and learning about the care systems they must interact with after, taking action themselves to navigate care. | • Less relevant, pre-diagnosis (prior to experience navigating care) |

The process of coming to understand the child has autism illustrates two key theoretical aspects: first, the impetus or motivation for parents’ responses and action does not necessarily develop suddenly but rather usually takes time to evolve over multiple steps of meaning-making; and second, the other meaning-making processes—in this case, informing the self and adapting emotionally—are inextricably linked with the process of defining concerns. Together, these processes prepare and motivate the parent for the early actions to engage in care.

Coming to understand the child has autism

Parents follow variable paths to the initial awareness that their child has autism. Most parent participants became aware well before the official diagnosis, which prompted them to take the action of pursuing a diagnostic assessment, usually because diagnosis was seen as necessary to access funded services. Only a minority became aware after diagnostic assessment. In either case, parents commonly passed through several steps to achieve this awareness. Here, we define a series of four possible steps that parents may generally undergo: forming an image of difference, starting to question the signs, knowing something is wrong, and being convinced it’s autism—all based on the personal meanings and interpretations parents constructed themselves.

Parents may skip earlier steps on their individual path to awareness, and thus, not all steps apply to all parents. Moreover, the duration spent within any one step varies according to unique personal factors and external interactions that lead to awareness. As certainty about the existence of a developmental concern grew, parents generally became progressively motivated to pursue more types of action, corresponding to their progressing readiness for engagement. First, we address the important influences that parents’ prior images, or understandings, have on how readily they pass through these steps.

Importance of prior images of the child and of autism

Most parents start out naïve about the possibility that their child is on the autism spectrum—excepting parents who have encountered autism in a previous child. Coming to understand the child has autism therefore often begins, before noticing any suggestive problems, with the parent’s initial images of their child and their parental role. Parents ultimately transform these prior images as they pass successive thresholds of awareness regarding their child’s autism. One major influence on the speed of the process is the varying strength of parents’ attachment to prior images, especially early expectations for the future. In one mother’s case, attachment to the prior image of her child was particularly strong due to limited fertility:

Well, we had really put her on a pedestal before that because . . . I mean, probably even more so than other parents. I thought I might never have a baby . . . So [learning she had autism] was really hard. It was the first time that the perfection disappeared.

For mothers like this, adapting emotionally (Table 1) was difficult and prolonged. She further described having to release her hold on dreams she had for her daughter’s future such as getting married and having children, which was highly distressing: “I spent about a week or ten days feeling like she had died. It was . . . yeah, it was really, really overwhelming. And I was just so sad.”

A second factor influencing parents’ readiness to transform prior images of their child is their initial understanding and emotional attitude toward autism itself. The following mother, who had developed a more detailed initial image of autism from her experience growing up with a brother with Asperger’s disorder, described her attitude after learning her son had autism in unexpectedly positive terms:

It was joy. And I know that that’s very backward for a lot of people. But I absolutely adore my brother [who had autism before my son]. I mean, he’s at [University] doing his Master’s right now, and was accepted to the doctorate program for engineering. But he’s decided not to do it. But he’s a very intelligent man and surpassed all kinds of barriers that service providers and doctors had sort of said would be in place. So right away my view of autism is very different than a lot of people’s. I’ve talked to friends who would say, “I would be devastated if my child had autism.” And I’m like, “Why!?” Because to me, it’s not as much of a barrier as it is to others. So it was joy, because I absolutely delight in my brother. He’s an absolutely amazing person and makes me laugh left, right, and center. And so I thought, ‘I’m going to have one of those. I’m going to have a boy like that. This is awesome.

Due to her positive image of autism, this mother showed remarkable emotional readiness to accept the possibility of autism and subsequently revised her image of her son quickly and easily.

Most parents in this study, however, started out less familiar with autism. They reported having at least some initial picture informed, for example, by fuzzy memories of the movie Rain Man (1988; Dustin Hoffman as Raymond Babbitt). Such incomplete images were usually associated with initially uncertain and negative expectations for the future. Consequently, many described reacting to the discovery of autism with powerful feelings of fear and sadness.

First step: forming an image of difference

A majority of parents began the process of coming to understand their child has autism by simply noticing what initially seemed like minor signs in their child. Parents commonly described responding to initial perceptions of these signs either by starting to see their child as slightly different in some respect and often “thinking nothing of it.” Importantly, parents did not perceive these signs as worrisome or problematic enough to represent a concern requiring action. Parents thus did not take action to further investigate or seek information about perceived signs at this step. Rather, the only action taken was to observe the child.

One mother reported noticing difference in her son in the first year of life,

When he was born, when we took him home, one thing that I noticed about him right away was that he preferred to be alone . . . If he was crying and he was having a difficult time settling, if you would just put him in his crib and close the door and walk out, that’s what would make him happy. And I always thought that was a little bit strange, because I do have nieces and nephews and none of them were like that. People would tell me he’s just one of those babies. Some babies get over-stimulated.

In this and other cases, mothers formed their images of difference based on comparison with other children. This mother did not interpret the signs as a reason for concern at least partly because others told her not to worry. Other parents recalled hearing reassurances like, “boys will be boys,” “all kids do that,” or “he’s just a late bloomer.” Sometimes parents formulated their own reassuring explanations why their child’s behavior was not problematic. Often parents later regretted accepting reassuring rationalizations, because they felt it delayed action and intervention. Parents likewise regretted ignoring more worrisome intuitions, or failing to critically challenge reassuring feedback, as one mother reflected:

So you have a tendency to trust your doctor and go, ‘OK, everything’s fine.’ Because you want everything to be fine. So you kind of push your own doubts away. If the doctor thinks everything’s fine, surely everything must be fine and we’re just seeing things that aren’t there. In hindsight, I wish I had listened to myself more.

Another factor that delayed some parents at this step was that they were raising their first child. Thus, they lacked knowledge of developmental milestones—the necessary reference points for forming an image of difference. Parents shared comments like, “He was my first baby, so I had no clue about how things were supposed to go.” Some eventually informed themselves by consulting parenting books or other sources. Others discovered the significance of the signs they observed after interacting with professionals or others with expert knowledge.

When parents first realized a difference was potentially problematic, they generally responded by starting to question the signs, or occasionally by skipping ahead to knowing something was wrong.

Second step: starting to question the signs

A parent can start to question the signs when the child’s behaviors she observes trigger an initially vague suspicion that a sign is problematic enough to warrant further investigation. This step is thus the parent’s first interpretive formulation that something is sufficiently unusual to motivate taking action. This is not action to intervene, but rather to assess and begin defining a potential problem that may be reason for concern. Parents’ motivation and engagement here is therefore limited to information gathering and reflection, whose goal is defining the problem enough to know whether further action is needed and what to do next.

This commonly begins with noticing one or more signs perceived as mildly problematic. For many parents, some information about these signs came from other professionals, such as daycare providers, positioned to observe the child for extended periods. Often, parents gradually integrated multiple signs, from multiple settings, over a period of time that, together, suggested there was something perhaps mildly concerning with their child. One mother recalled how she slowly moved beyond seeing her son as just different:

It wasn’t until, I guess, just after he turned a year. He hated his first birthday party, which surprised me. He screamed through the whole thing. And Christmas that year was hard . . . I remember we’d gone to playgroup. He wasn’t playing with the other kids. He would sit with me, which wasn’t untypical because there were other kids that just sat with their parents. He wasn’t interested in toys. He wasn’t interested in venturing away from me. One of the other moms was saying the other day he was eating soup on his own and I was like, “Wow!” So I just kept putting things in the back of head and thinking, “Oh. Oh,” you know.

Some parents began tracking emerging signs in written logs. Whether awareness developed gradually or suddenly, parents’ perceptions eventually crossed a threshold for taking action to pursue information more insistently.

Non-specific versus autism-specific signs

Parents approached information-seeking differently depending on whether they were naïve or aware of autism as a possibility. Autism-naïve parents sought the roots of what they perceived to be isolated problems unrelated to autism—such as pursuing tests for possible hearing problems, or speech and language assessment for perceived speech delays—prior to and independent of any diagnostic assessment. Such parents usually progressed to knowing something was wrong non-specifically to autism, often seeking input from professionals who subsequently helped them consider autism as an underlying concern.

Alternatively, parents who became aware and emotionally accepted the possibility of autism in this step eventually sought information about specific signs of autism. For example, several found information about established red flags for autism, questioning whether these matched signs they observed in their child. For these parents, questioning signs frequently led directly to being convinced the child had autism (i.e. skipping the step knowing something is wrong).

In seeking information, many parents first consulted clinicians, often a family physician. Clinicians could respond by affirming the problematic nature of the sign, or by denying or playing down its significance. Professional affirmation, either of an unspecified problem or of autism itself, rapidly transformed the parent’s vague suspicion into a real concern, leading to either knowing something is wrong or being convinced it is autism. Professional denial, however, often delayed parents understanding their child had autism. At this pre-concern stage, parents were less insistent their questioning and observations be taken seriously and accepted professional denial with less protest.

Some parents were encouraged to start questioning the signs by a tactful professional, usually after questioning a sign they were unaware indicated autism. Since some types of professionals are unqualified to diagnose autism, many took care to avoid using the label and instead employed roundabout ways to raise the parent’s awareness. Parents described how professionals’ prompts raised questions in their own minds that led them to seek further information, such as by investigating red flags for autism or initiating conversations to develop awareness. Other parents were encouraged to question the signs by relatives or acquaintances with expert knowledge. This helped gently guide parents past feelings of denial, speeding awareness of their child’s autism, and thus readiness to engage in care.

Parents generally began proactively informing themselves at the point of starting to question the signs. Parents who considered autism a possibility described researching, often to seek specific information they learned existed from knowledgeable experts. Such parents almost always began by using Internet search engines like Google. At this stage, parents usually focused only on information informing whether their child had autism—being less concerned with information about the meaning of autism, until later.

Third step: knowing something is wrong

Eventually, parents interpret that the signs they have observed in their child indicate a problem sufficiently concerning to warrant urgent attention and action. For example, multiple parents, after initially seeking clinical assessments to investigate perceived speech or hearing problems, ultimately perceived these narrow functional problems to indicate a broader more serious developmental impairment, causing worry and a sense of urgency to take action. We note that parents themselves used the word “wrong” in multiple instances to convey the more serious nature of a perceived emerging concern that they recognized had the potential to significantly impact their child’s future. In many cases, parents reached a point of knowing something is wrong after interacting with knowledgeable others (professionals, acquaintances, relatives), who interpreted the signs and guided them to grasp the serious nature of the problem earlier than they otherwise would have.

The transition to this step can be gradual, particularly when parents are not ready to abandon rationalizations for not being concerned about the signs they observe. One mother described finally overcoming such rationalizations as follows:

Actually, I worried for a long time because I was telling myself, ‘No, it’s going to happen next month. He’ll talk next month. It’s gonna be next month,’ you know. I knew something was wrong. But then I was telling myself, ‘You know what, maybe it’s a little too early. You know, kids, sometimes they develop in different ways. So maybe he’s taking a little longer. He will talk. He will talk.’ That’s what I was telling myself. But then I said, ‘Uh-oh, that’s it. We have to do something now.’

While knowing something is wrong generally features continued questioning of poorly understood signs by seeking information, it is also when most parents begin experiencing a pronounced sense of urgency for action to intervene due to feelings of fear and anxiety about their child’s wellbeing, uncertainty about the nature of the problem, and implications for the future. Thus, the goal of understanding the problem here is not to determine whether intervention is necessary, but rather to quickly understand the problem clearly enough to know how to intervene.

Autism-naïve parents usually first identified worrisome but non-specific social functioning or developmental problems, or non-autism diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as reasons for concern. This increased motivation for informing the self usually led to first contact with information regarding the possibility of autism.

Role of adapting emotionally

Adapting emotionally, specifically the three early aspects listed in Table 1, is an essential part of coming to understand the child has autism, especially in this step. The first aspect that parents can struggle with is accepting the possibility of autism (sometimes occurring earlier, in starting to question the signs). Described above, prior images of the child and of autism substantially influenced how difficult or slow this could be.

Denial, as identified by parents themselves, represented the most apparent emotional barrier to accepting the possibility of autism. It generally delayed readiness for action and ultimately slowed engagement in parent-desired care. Importantly, denial precluded reaching the point of knowing something is wrong despite signs of developmental problems. In many cases in this study, it was the father who remained resistant to accepting that something was wrong, sometimes even after the child was positively diagnosed with autism. The denial behaviors of partners sometimes became a barrier, reducing the mother’s motivation and capacity to take action in response to knowing something is wrong. Some fathers were in such denial they obstructed the mother’s pursuit of a diagnosis or intervention—for example, by limiting access to financial resources or transportation.

Knowing something is wrong is also when many parents begin the emotional process of releasing (and recasting) culturally-based hopes and expectations for their child’s future (see Table 1, Adapting emotionally), as they start imagining the possible long-term implications of a serious developmental problem—commonly involving milestones like university, marriage, employment, or living independently. (Illustrating how such expectations are not uniform across cultures, one Northern Ontario participant described how some Indigenous families’ initial reactions could differ from those of non-Indigenous families, with some communities traditionally holding more open attitudes, customs, and expectations regarding development and inclusion. Note, however, that “culture” here is not restricted to ethnocultural groups, but can refer to the set of ideas, attitudes, and practices shared by any social group. For example, the important cultural influences include those of smaller social groups, such as the formative effects of a parent’s own family growing up.) The main manifestation of difficulty with this aspect of emotionally adapting is transient grieving, due to abrupt loss of cherished hopes for the future. One mother reflectively distinguished the idea of giving up culturally based hopes for the future, from the more visceral feeling parents recalled experiencing at the time, of actually losing one’s child entirely:

But for [my husband and me], when we’ve talked about it since, we grieved for the kids we thought we were getting. You know, you think you’re getting your neurotypical, normal children that are going to run and play. You have this idea in your head of how they’re going to grow up, and the things that you’re going to do with them. And when somebody tells you, “Oh, they might have autism . . .” all those things are sort of ripped away from you. And you have to grieve those pictures in your head that you’re never going to be able to do with them. Or, that’s what we thought then.

Grieving transiently delayed parents’ readiness for taking early action such as seeking or accepting more certain information about the possibility of autism or pursuing initial forms of intervention. But it was invariably transient, as parents adapted to realities of their new situation. Most parents, however, could modify their expectations more incrementally, avoiding intense grieving.

Parents who accepted the possibility of autism (but were not yet convinced it is autism) usually became driven to research the condition further, specifically to understand its meaning and how to intervene. Numerous autism-aware parents described strong emotional reactions to the online information they encountered at this point—usually fearful. Indeed, for many such parents, informing the self became inseparable at this point from another process, accepting an uncertain and frightening future for their child, in which parents struggle to accept new images and expectations to replace the ones they let go of. The difficult part of this process for parents often involved managing the fears that some online information sources caused.

Parents described being scared by what they felt in hindsight were unbalanced portrayals of autism, depicting only dramatic impairment and bleak outcomes (e.g. institutionalization, no autonomy) that they did not understand at the time might not apply to their child. These often exaggerated images made accepting an uncertain and frightening future for their child too emotionally overwhelming for many parents, delaying their psychological readiness to take action. As one mother, speaking on behalf of both parents, recalled, “I think both of us were probably a little afraid of what we’d read. So we read sparingly. We’d see [something about autism], we’d read . . . and then we’d kind of back off.” Another parent shared how fear affected her attitude to researching,

And that was about all I could handle. I couldn’t go to any other websites at that point because I was still in shock, because I thought my whole life . . . or actually [our son’s] whole life was over, at that point. I was positive—I said: ‘We’re going to have to institutionalize him.’

The earlier aspects of adapting emotionally therefore powerfully influence parents’ readiness. Not only can specific difficulties cause critical delays in readiness for action, but the same worries and fears could sometimes be powerful motivators for action.

Taking action by seeking professionals’ help

Seeking professionals’ help was the most common action parents took before diagnosis. At the point of knowing something was wrong, they requested more direct and specific help than in earlier steps—either for intervention to address specific concerns or for referrals to specialists to definitively identify a problem. Parents actively sought referrals from family physicians, followed referrals or recommendations from community-based professionals, and sometimes self-referred to community or regional child services—in many cases unaware that the underlying problem involved autism.

Parents were also more insistent, motivated by certainty that something was wrong and their mounting sense of urgency. Parents therefore became frustrated when access was blocked, such as by dismissive responses from professionals. Because parents were certain about the existence of problems requiring intervention, they often expended extra personal resources (time, energy, money) to pursue alternative solutions when obstacles blocked or delayed needed help.

Fourth step: being convinced it is autism

Parents generally reach the point of being convinced it is autism either by (a) reaching certainty independently after integrating the signs observed in their child with information about indicators for autism or (b) after being informed by others with expertise.

Most parents who described reaching certainty independently recalled checking off many of the red flags for autism or noticing what they understood were distinct signs of “classic autism.” Other parents, meanwhile, described how observing exceptions to classic autism threw them off because such signs justified denying autism, delaying them reaching certainty. Consequently, parents could follow extended paths, involving numerous professionals and extra researching, before becoming convinced of autism. Parents regarded such delays as avoidable and regrettable because they postponed early intervention perceived as crucial to optimizing their child’s trajectory.

Only a minority of parents reached certainty after being informed by others—clinicians, trusted acquaintances, or relatives—perceived to have appropriate knowledge or training. Adapting emotionally to this information took longer when the news triggered initial denial and shock. Such responses were more common among the small minority of parents who were still naïve about the possibility of autism upon being informed. One mother, having reached the point of knowing something was wrong with her son, thought he had ADHD and was shocked to learn the signs she observed indicated autism:

I knew nothing about autism . . . I thought, “No, no, no.” Because he has [ADHD], he can’t have [autism], you know. So it hit us like a . . . we hit a brick wall when we sat there and we actually received the diagnosis. I was almost in disbelief.

Another autism-naïve mother described the intense emotion of rapidly going from knowing something is wrong to being convinced it was autism as, “the most unreal, anxiety-provoking, nightmarish feeling.” Many parents described confusion at first being told their child had autism, commonly seeking further information for clarification, usually on the Internet. Several parents who entered a state of shock after being informed their child had autism described closing themselves off to what professionals around them were saying.

Multiple professionals interviewed described how some parents’ outward expressions of denial could be confrontational and heated, reflecting the threat this information posed to them emotionally. Parents in this situation clearly needed more time for the early aspects of adapting emotionally before being ready to engage. Upon reaching full certainty of autism, however, parents’ motivation for action rapidly increased.

Discussion

This in-depth account of parents’ early-stage process of coming to understand the child has autism fills two important knowledge gaps: First, it provides a useful empirical illustration of important theoretical aspects of the emergent process of parents navigating autism-related services and intervention, supporting an earlier, broader report of how caregivers become increasingly motivated and capable of engaging in care (Gentles et al., 2019). Second, it provides a detailed account of parents’ social psychological experience and action prior to diagnosis of autism, which has received little attention from a lifeworld, rather than clinically referenced, perspective.

Parents’ experience of the diagnostic process has been characterized by numerous qualitative studies from multiple jurisdictions, including two systematic reviews representing 32 unique studies (Boshoff et al., 2018; Legg & Tickle, 2019) and additional non-reviewed studies (e.g. Crane et al., 2018; Hennel et al., 2016; Ho et al., 2014; Mitchell & Holdt, 2014; Singh, 2016; van Tongerloo, van Wijngaarden, van der Gaag, & Lagro-Janssen, 2015). Some of this literature covers parents’ pre-diagnosis experience, providing findings that are positioned as useful to clinicians supporting families before and around diagnosis. Importantly, and consistent with our research, a subset of studies observed parents’ proactive engagement in pursuing the diagnosis and otherwise seeking clinical help for pre-diagnosis concerns (reviewed in Boshoff et al., 2018). For example, Carlsson and colleagues (2016) described how Swedish parents prior to any clinical interactions had a low sense of urgency, initially perceiving their child as different in a non-worrisome sense—similar to our observations for the initial step of forming an image of difference—which then gave way to more proactive information seeking. We also observed similar patterns to those reported in Boshoff and colleagues (2018), of parents “not feeling heard” (p. 5) by uncooperative clinicians on their pathway to diagnosis after identifying emerging concerns. These empirical accounts of emerging pre-diagnosis action by parents should by now establish an important fact, currently underrecognized in most other literature on parents’ engagement in autism services including diagnosis: that parents often achieve some level of awareness and proactive engagement with services before diagnosis and that diagnosis is rarely the first cue for seeking clinical care to address autism-related concerns.

Notably, the available research usually traces pre-diagnosis experience with reference to clinical processes and interactions culminating in diagnosis, rather than parents’ independent meaning-making including interactions that are not necessarily centered in the clinical world. While this is useful for mapping experience through clinical pathways (as they vary by jurisdiction), it becomes problematic when aspects of parents’ internal experience are incorporated into a temporal arrangement referenced to the external clinical event, diagnosis. For example, Legg and Tickle (2019), in temporally arranging parents experiences relative to the clinical diagnosis, place the processes “acceptance and adaptation” post-diagnosis. Their model cannot, however, account for cases where these processes may happen before diagnosis. Similarly, Midence and O’Neill (1999) describe UK parents’ accepting their child’s autism as integral to their child only as a post-diagnosis phenomenon. By considering parents’ meaning-making from a broad set of interactions, not just clinical, we have demonstrated with specificity how comparable emotional processes, including releasing culturally-based hopes and expectations for their child’s future, can also happen before diagnosis.

A useful approach to interpreting transferability of findings like ours, involving parents’ meaning-making and action, is to consider informational context, especially the paths of diffusion and discourses arising from new scientific knowledge. For example, Liu, King, and Bearman (2010) demonstrated how information diffusion simultaneously contributed to the increased prevalence, spatial clustering, and decreasing age of diagnosis of autism in California over time. Considering such contextual effects is useful to inform the appropriate integration of findings from individual studies within qualitative syntheses across contexts—for example, by contextualizing older findings that conflict with more recent or local studies when they are explainable by ecological differences, such as the prevailing awareness and acceptance of autism.

Indeed, the high levels of proactive engagement we observed most parents reach during and after coming to understand their child had autism (Gentles et al., 2019) may be a relatively recent Western phenomenon and be subject to further change. Gray (2001) described three narratives Australian parents used to create coherence from the disordering effects of autism on the family and parent’s identity: one that accepted the prevailing narrative of autism offered by the local autism treatment center—“accommodation”; and two less common ones that disputed it—“resistance” by defining a more engaged advocacy role, and “transcendence” by drawing on religious faith. In our study, conducted almost 15 years later, most parents’ stories best fit the “resistance” narrative. More recent to Gray, Lilley (2011) described 13 Australian mothers constructing counter-narratives along their varied pathways to diagnosis that best fit with “resistance,” ultimately providing a “temporary disidentification from the diagnostic process” (p. 207). Subsequently, based on interviews with 23 US families, Singh (2016) described how parents both embraced the prevailing medical model (pursuing a clinical autism diagnosis) and challenged its limitations from defining the disorder negatively. Responding to parents’ disillusionment with limiting models, research recognizing the value of strengths-based approaches in the autism diagnostic setting has emerged (Sabapathy et al., 2017), which may further change the contextual conditions surrounding the parents’ increasing clinical engagement in diagnostic processes going forward.

This study was predominantly about mothers. Aware of the risks of being “gender blind” (Ryan & Runswick Cole, 2009; Traustadottir, 1991)—where oppressive imbalances in the roles and experience of mothers are rendered invisible—we highlight some of the ways gender was relevant. From the outset, we chose to focus primarily on mothers since they were known to assume the most responsibility for caring for children with special needs (Marcenko & Meyers, 1991), engage most in autism care-related information seeking (Mackintosh, Myers, & Goin-Kochel, 2005), and bear the greater stress burden (Gray & Holden, 1992)—all of which proved empirically true in this study. In addition, by examining fathers’ roles via mothers’ accounts (and their direct participation in three interviews), we observed interactions indicating both commonality and some gender differences. First, mothers generally spent more time with the child, being more likely to stay at home either for maternity leave or decisions to forgo employment; consequently, they were better positioned to perceive and interpret signs necessary to understanding the child had autism. Second, consistent with some research (Legg & Tickle, 2019), fathers tended to hold onto denial for longer, which made some uncooperative as partners, reducing mothers’ motivation and capacity for action and rarely, obstructing action at this early stage. These findings provide some explanation of how oppressive structures relate to the early development of what has been described alternately as mothers’ “special competence” (Ryan & Runswick Cole, 2008) and “warrior-hero identity” (Sousa, 2011)—which have merely shifted the historical burden on mothers to increased advocacy roles that, while more visible, remain undervalued.

Clinical implications

This research reinforces the need for sensitivity to parents’ widely varying states of awareness and understanding of their child’s autism when seeking to engage them at early stages of their clinical journey. It is reasonable to expect that some parents at the point of diagnosis, for example, may be far along in this process, having some foundational knowledge of autism and being highly motivated to work with professionals who can help. For others who are still early in this process, however, insisting on high levels of engagement, such as by providing extensive verbal or written information at diagnosis, may have unintended psychological consequences and yield resistant or unmotivated responses. Consequently, clinicians can consider attending to two things: first, appraising the parent’s level of motivation, which can range from ambivalence to powerful insistence, as one indicator of how far they have progressed in a process defined by increasing urgency; second, probing the parent on what other information, professionals, actions or work they have already engaged in as a means to understand their readiness for engagement.

Other work has emphasized the merits of attending to parents’ psychological support needs around the time of diagnosis to improve both family and child outcomes beyond what can be achieved by timely diagnosis and treatment (Reed & Osborne, 2012). To support this, authors have advocated for autism-specific tools to assess parents’ psychosocial functioning and support needs starting from the time of diagnosis, which could be useful to connect subgroups of parents to tailored intervention to increase their capacity for engaging in care (Reed & Osborne, 2012; Zaidman-Zait, 2018; Zaidman-Zait et al., 2017). The findings here highlight two important ways that parents vary that may be relevant to assessing, categorizing, and triaging them to targeted psychosocial support. First, some parents must overcome the barrier of denial, a form of avoidance that prevents them accepting and acting on the possibility of autism in the first place—which other research has recognized as an early potential response to signs of autism (Altiere & von Kluge, 2009; Boshoff et al., 2018; Crane et al., 2018; Luong, Yoder, & Canham, 2009). Denial was regarded with regret by some parents who recognized in hindsight it delayed them in seeking care, a finding suggested recently elsewhere (Crane et al., 2018, p. 3764). Second, some, but not all, parents pass through a personal process of grieving, which delays them adapting emotionally, specifically releasing culturally based hopes and expectations for their child’s future.

Importantly, these findings provide explicit rationale for separating and logically ordering any support to address these two delays to readiness—since denial that prevents accepting the possibility of autism must be overcome before grieving is possible. This distinction is salient for two reasons: (a) these processes are sometimes still confounded with each other in the literature (Fernańdez-Alcántara et al., 2016; Mitchell & Holdt, 2014) despite major concerns with a stage model of grieving (Stroebe, Schut, & Boerner, 2017) and (b) the findings suggest that appropriate clinical support should be tailored differently for denial than for grieving, in view of the fact that parents in this study described them as separate sources of delay to engaging in care.

Especially in early reports, grief has been portrayed as the standard response to receiving an autism diagnosis (discussed in Russell & Norwich, 2012). Consequently, Ryan and Runswick-Cole (2008) note, “positive or even neutral family experiences . . . remain under-represented” (p. 202). By contrast, findings here suggest the importance of not treating grieving as a universal or necessary aspect of parents’ internal process. Not only did grieving arise inconsistently for parents in this study, but one mother’s example of happiness at discovering autism derived from her prior understandings suggests a useful alternative perspective to balance the potential damage of grief-promoting perspectives. As autistic self-advocate, Jim Sinclair, articulated in 1993 (republished 2012), grieving taken too far may damage the parent–child relationship by implying that the grieving parent’s love for the child they had expected outweighs any love for the autistic child they have. The perspective articulated by Sinclair (and other contributors to the neurodiversity movement) has likely influenced later parents’ attitudes and discourses, as Cascio (2012) observed. Indeed, the increasingly prevalent discourses like neurodiversity emphasizing strengths in autism appeared to explain some parents’ non-grieving responses in our study, and highlighting this perspective may represent a constructive cognitive strategy to support parents struggling with grief.

Limitations and next steps

As acknowledged previously (Gentles et al., 2019), since this study included primarily mothers of younger children and adolescents with autism, the findings do not sufficiently represent the perspectives of important subgroups of Ontario parents, including fathers, and those for whom English is a second language. While the limited data available here suggest many aspects of coming to understand the child has autism are likely transferrable to fathers, some differences, such as more prolonged denial, were observed. This has implications for applying the findings to support these other groups. Indeed findings elsewhere linking gender differences in the process of grieving to strained marital communication and misunderstanding (Potter, 2016; Wing, Clance, Burge-Callaway, & Armistead, 2001) suggest that attending to differences with fathers could have implications for appropriate family support. Moreover, there is an ethical imperative to correct the research imbalance disadvantaging fathers (Braunstein, Peniston, Perelman, & Cassano, 2013; Lashewicz, Shipton, & Lien, 2017). Research has identified issues in some ethnocultural subgroups of parents for whom English is a second language, but mostly outside Ontario. For example, stigma in the Somali population in the United Kingdom is associated with a lack of vocabulary describing autism among that community (Selman et al., 2018). The significant populations of Somali, and other origins, within Ontario provide an opportunity to further explore such findings.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed account of how parents of children with autism come to understand that their child has autism, contributing to the emerging knowledgebase of parents’ experience before diagnosis. Furthermore, it provides perhaps the first explanatory account of how parents become ready for engagement in care at this early stage. The findings indicate the need for sensitivity to parents’ varying state of awareness and knowledge of their child’s autism when engaging them in early care and the need to tailor parent support interventions to address specific challenges on the path to coming to understand their child has autism.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the parents and professionals who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Stephen Gentles was supported for this doctoral research by two Strategic Training Initiative in Health Research fellowships funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research—an Autism Research Training Fellowship (jointly funded by the Sinneave Family Foundation) and Knowledge Translation Canada Fellowship—and a research award from Autism Ontario.

ORCID iD: Stephen J Gentles  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2004-1451

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2004-1451

References

- Altiere M. J., von Kluge S. (2009). Searching for acceptance: Challenges encountered while raising a child with autism. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 142–152. doi: 10.1080/13668250902845202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASD Clinical Expert Committee. (2017). Ontario Autism Program Clinical Framework (1–35). Toronto, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services. [Google Scholar]

- Barry C. A., Stevenson F. A., Britten N., Barber N., Bradley C. P. (2001). Giving voice to the lifeworld. More humane, more effective medical care? A qualitative study of doctor-patient communication in general practice. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 487–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boshoff K., Gibbs D., Phillips R. L., Wiles L., Porter L. (2018). A meta-synthesis of how parents of children with autism describe their experience of advocating for their children during the process of diagnosis. Health and Social Care in the Community, 39, 233–215. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein V. L., Peniston N., Perelman A., Cassano M. C. (2013). The inclusion of fathers in investigations of autistic spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brian J. A., Smith I. M., Zwaigenbaum L., Roberts W., Bryson S. E. (2015). The Social ABCs caregiver-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: Feasibility, acceptability, and evidence of promise from a multisite study. Autism Research, 9, 899–912. doi: 10.1002/aur.1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson E., Miniscalco C., Kadesjö B., Laakso K. (2016). Negotiating knowledge: Parents’ experience of the neuropsychiatric diagnostic process for children with autism. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51, 328–338. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio M. A. (2012). Neurodiversity: Autism pride among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50, 273–283. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.3.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. C. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, England: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Crane L., Batty R., Adeyinka H., Goddard L., Henry L. A., Hill E. L. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3761–3772. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L., Chester J. W., Goddard L., Henry L. A., Hill E. (2016). Experiences of autism diagnosis: A survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism, 20, 153–162. doi: 10.1177/1362361315573636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N. O., Carter A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1278–1291. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernańdez-Alcántara M., García-Caro M. P., Pérez-Marfil M. N., Hueso-Montoro C., Laynez-Rubio C., Cruz-Quintana F. (2016). Feelings of loss and grief in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 55, 312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles S. J., Charles C., Ploeg J., McKibbon K. A. (2015). Sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. The Qualitative Report, 20, 1772–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Gentles S. J., Jack S. M., Nicholas D. B., McKibbon K. A. (2014). A critical approach to reflexivity in grounded theory. The Qualitative Report, 19(44), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gentles S. J., Nicholas D. B., Jack S. M., McKibbon K. A., Szatmari P. (2019). Parent engagement in autism-related care: A qualitative grounded theory study. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 7(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2018.1556666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. (1978). Advances in the methodology of grounded theory: Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: The Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray D. E. (2001). Accommodation, resistance and transcendence: Three narratives of autism. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 1247–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray D. E., Holden W. J. (1992). Psychosocial well-being among the parents of children with autism. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 18, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hennel S., Coates C., Symeonides C., Gulenc A., Smith L., Price A. M., Hiscock H. (2016). Diagnosing autism: Contemporaneous surveys of parent needs and paediatric practice. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 52, 506–511. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho H. S., Yi H., Griffiths S., Chan D. F., Murray S. (2014). ‘Do It Yourself’ in the parent-professional partnership for the assessment and diagnosis of children with autism spectrum conditions in Hong Kong: A qualitative study. Autism, 18(7), 832–844. doi: 10.1177/1362361313508230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashewicz B. M., Shipton L., Lien K. (2017). Meta-synthesis of fathers’ experiences raising children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 69, 117–131. doi: 10.1177/1744629517719347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg H., Tickle A. (2019). UK parents’ experiences of their child receiving a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Autism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1362361319841488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley R. (2011). Maternal intimacies: Talking about autism diagnosis. Australian Feminist Studies, 26, 207–224. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2011.574600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.-Y., King M., Bearman P. S. (2010). Social influence and the autism epidemic. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 1387–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong J., Yoder M. K., Canham D. (2009). Southeast Asian parents raising a child with autism: A qualitative investigation of coping styles. The Journal of School Nursing, 25, 222–229. doi: 10.1177/1059840509334365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh V., Myers B., Goin-Kochel R. (2005). Sources of information and support used by parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 12, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Marcenko M., Meyers J. C. (1991). Mothers of children with developmental disabilities: Who shares the burden? Family Relations, 40, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Midence K., O’Neill M. (1999). The experience of parents in the diagnosis of autism: A pilot study. Autism, 3, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C., Holdt N. (2014). The search for a timely diagnosis: Parents’ experiences of their child being diagnosed with an Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 26, 49–62. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2013.849606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M., Coulehan J. (2014). Maintaining confidentiality in qualitative publications. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 151–152. doi: 10.1177/1049732314563489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne L. A., McHugh L., Saunders J., Reed P. (2007). Parenting stress reduces the effectiveness of early teaching interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1092–1103. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0497-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne L. A., McHugh L., Saunders J., Reed P. (2008). A possible contra-indication for early diagnosis of autistic spectrum conditions: Impact on parenting stress. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne L. A., Reed P. (2008). Parents’ perceptions of communication with professionals during the diagnosis of autism. Autism, 12, 309–324. doi: 10.1177/1362361307089517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. A. (2016). “I received a leaflet and that is all”: Father experiences of a diagnosis of autism. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45, 95–105. doi: 10.1111/bld.12179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky I., Nelson G. (2000). Promoting child and family wellness: Priorities for psychological and social interventions. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10, 85–105. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P., Osborne L. A. (2012). Diagnostic practice and its impacts on parental health and child behaviour problems in autism spectrum disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 97, 927–931. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell G., Norwich B. (2012). Dilemmas, diagnosis and de-stigmatization: Parental perspectives on the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 229–245. doi: 10.1177/1359104510365203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S., Runswick Cole K. (2008). Repositioning mothers: Mothers, disabled children and disability studies. Disability & Society, 23, 199–210. doi: 10.1080/09687590801953937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S., Runswick Cole K. (2009). From advocate to activist? Mapping the experiences of mothers of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00438.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabapathy T., Madduri N., Deavenport-Saman A., Zamora I., Schrager S. M., Vanderbilt D. L. (2017). Parent-reported strengths in children with autism spectrum disorders at the time of an interdisciplinary diagnostic evaluation. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 38, 181–186. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L., Dawson G., Stahmer A. C., Landa R., Rogers S. J., McGee G. G., . . . Halladay A. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2411–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman L. E., Fox F., Aabe N., Turner K., Rai D., Redwood S. (2018). ‘You are labelled by your children’s disability’: A community-based, participatory study of stigma among Somali parents of children with autism living in the United Kingdom. Ethnicity & Health, 23, 781–796. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1294663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J. (2012). Don’t mourn for us. Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies, 1(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Singh J. S. (2016). Parenting work and autism trajectories of care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 38, 1106–1120. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa A. C. (2011). From refrigerator mothers to warrior-heroes: The cultural identity transformation of mothers raising children with intellectual disabilities. Symbolic Interaction, 34, 220–243. doi: 10.1525/si.2011.34.2.220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A., Corbin J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H., Boerner K. (2017). Cautioning health-care professionals: Bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying, 74, 455–473. doi: 10.1177/0030222817691870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traustadottir R. (1991). Mothers who care: Gender, disability, and family life. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 211–228. doi: 10.1177/019251391012002005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Tongerloo M. A. M. M., van Wijngaarden P. J. M., van der Gaag R. J., Lagro-Janssen A. L. M. (2015). Raising a child with an autism spectrum disorder: “If this were a partner relationship, I would have quit ages ago.” Family Practice, 32, 88–93. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing D. G., Clance P. R., Burge-Callaway K., Armistead L. (2001). Understanding gender differences in bereavement following the death of an infant: Implications for treatment. Psychotherapy, 38, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Zait A. (2018). Profiles of social and coping resources in families of children with autism spectrum disorder: Relations to parent and child outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 2064–2076. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3467-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Zait A., Mirenda P., Duku E., Vaillancourt T., Smith I. M., Szatmari P., . . . Thompson A. (2017). Impact of personal and social resources on parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21, 155–166. doi: 10.1177/1362361316633033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]