Abstract

The present study explored the potential effect of pterostilbene as a prophylactic treatment on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced intestinal injury of broiler chickens by monitoring changes in mucosal injury indicators, redox status, and inflammatory responses. In total, 192 one-day-old male Ross 308 broiler chicks were randomly divided into four groups. This trial consisted of a 2 × 2 factorial design with a diet factor (supplemented with 0 or 400 mg/kg pterostilbene from 1 to 22 d of age) and a stress factor (intraperitoneally injected with saline or LPS at 5.0 mg/kg BW at 21 da of age). The results showed that LPS challenge induced a decrease in BW gain (P < 0.001) of broilers during a 24-h period postinjection; however, this decrease was prevented by pterostilbene supplementation (P = 0.031). Administration of LPS impaired the intestinal integrity of broilers, as indicated by increased plasma diamine oxidase (DAO) activity (P = 0.014) and d-lactate content (P < 0.001), reduced jejunal villus height (VH; P < 0.001) and the ratio of VH to crypt depth (VH:CD; P < 0.001), as well as a decreased mRNA level of jejunal tight junction protein 1 (ZO-1; P = 0.002). In contrast, pterostilbene treatment increased VH:CD (P = 0.018) and upregulated the mRNA levels of ZO-1 (P = 0.031) and occludin (P = 0.024) in the jejunum. Consistently, pterostilbene counteracted the LPS-induced increased DAO activity (P = 0.011) in the plasma. In addition, the LPS-challenged broilers exhibited increases in nuclear accumulation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) p65 (P < 0.001), the protein content of tumor necrosis factor α (P = 0.033), and the mRNA abundance of IL-1β (P = 0.042) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3; P = 0.019). In contrast, pterostilbene inhibited the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 (P = 0.039) and suppressed the mRNA expression of IL-1β (P = 0.003) and NLRP3 (P = 0.049) in the jejunum. Moreover, pterostilbene administration induced a greater amount of reduced glutathione (P = 0.017) but a lower content of malondialdehyde (P = 0.023) in the jejunum of broilers compared with those received a basal diet. Overall, the current study indicates that dietary supplementation with pterostilbene may play a beneficial role in alleviating the intestinal damage of broiler chicks under the conditions of immunological stress.

Keywords: broiler, immunological stress, intestinal injury, lipopolysaccharide, oxidative damage, pterostilbene

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the worldwide increase in the demand for animal products has resulted in the use of intensive systems, which make animals more vulnerable to various stress stimulators including immunologic stress. The intestines of some animals are prone to infection, since they are continuously exposed to a large load of antigens from food, resident bacteria, and invading viruses (Söderholm and Perdue, 2001). Disruption of intestinal homeostasis is linked to a defective mucosal barrier with an increased permeability, leading to bacterial translocation and subsequent intestinal inflammation (Nakagawa et al., 2009). In poultry production, intestinal inflammation is a serious and common disease that decreases production and can even cause sudden death. This usually takes place during the growing phase when the intestinal mucosa displays immaturities in the anatomy and function (Nanthakumar et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016a). Many attempts have been tried to fight infections or prevent the onset of intestinal inflammation in poultry production through dietary supplementation with plant-derived active substances (Shen et al., 2010; Sahin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Kamboh et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017). However, the low-water solubility, short half-life, and poor in vivo bioavailability of natural agents often limit their efficacy in practical production (Liu et al., 2009). Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify nutritional factors that can contribute to preventing and/or treating intestinal inflammation with superior bioavailability and convenience.

Pterostilbene (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4′-hydroxystilbene), a natural dimethylether analog of resveratrol, is a phytoalexin generally found in blueberries and Pterocarpus marsupium heartwood (Roupe et al., 2006). Emerging evidence indicates that pterostilbene has attractive preventive and therapeutic properties in a range of diseases associated with inflammation (Chang et al., 2012; Choo et al., 2014; Zhang and Zhang, 2016; Kosuru et al., 2018). Interestingly, pterostilbene usually exhibits stronger anti-inflammatory potencies when compared with its parent compound (Chang et al., 2012; Choo et al., 2014). The substitution of hydroxy with the methoxy group increases the lipophilicity and oral absorption of pterostilbene, which consequently improves its membrane permeability and biological potency (Athar et al., 2007; Perecko et al., 2010; Kapetanovic et al., 2011). It has been reported that pterostilbene shows 95% bioavailability when administered orally, while resveratrol has only 20% bioavailability (Lin et al., 2009). As a result, pterostilbene could be a better candidate with great promise for further research. To the best of our knowledge, the role of pterostilbene in alleviating the intestinal inflammation of broiler chicks remains obscure. This investigation is therefore aimed at evaluating the protective effects of pterostilbene on intestinal morphology, antioxidant function, and inflammatory status of broiler chicks under immunological stress circumstances.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

We obtained approval for the current research from the Nanjing Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Permit number SYXK-2017-0007). In this study, 192 one-day-old male Ross 308 broiler chicks were randomly allocated into four groups in a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement. Each group contained six replicates with eight birds per replicate. Four treatment groups were designated as follows: (i) in the CON-SS group, birds received a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; (ii) in the PT-SS group, birds received a basal diet with a 400 mg/kg supplement of pterostilbene (#537-42-8; BOC Sciences, New York) and received an injection of sterile saline; (iii) in the CON-LPS group, birds received a basal diet and an injection of Escherichia coli O55:B5 lipopolysaccharide (LPS; #L2880; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO); and finally (iv) in the PT-LPS group, birds received a basal diet with a 400 mg/kg supplement of pterostilbene and received an injection of LPS. The dosage of pterostilbene was determined according to the added levels of its parent compound resveratrol in the diets of broilers to prevent and/or treat different stressful events (Sridhar et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017a,b). All birds were contained in three-level wired battery cages in an environmentally controlled room kept at 32 to 34 °C from 1 to 7 d of age. The temperature of the room was then gradually reduced to 26 °C at the rate of 3 to 4 °C/wk and kept constant thereafter. Light was kept on a cycle of 23 h on and 1 h off for the duration of the experiment. The birds had access to mash feed and water ad libitum during the 22-d feeding trial. The basal diet was formulated according to the National Research Council (1994) to meet the nutritional requirements of the chicks, and its composition and nutrient levels are given in Supplemental Table S1. At 21 d of age, LPS at 5.0 mg/kg BW was injected intraperitoneally into the broilers in the CON-LPS and PT-LPS groups, while the broilers in the CON-SS and PT-SS groups were injected with 0.86% sterile saline. The LPS treatment was dissolved in 0.86% sterile saline and dosed based on the results obtained from a previous study (Xie et al., 2000).

Growth performance

The BW and feed intake of the birds were measured at 1, 21, and 22 d of age on a cage basis. ADG, ADFI, and G:F were determined before the LPS challenge (from 1 to 21 d of age), and BW gain was determined after the LPS challenge (from 21 to 22 d of age).

Sample collection

At 24 h postinjection, six broilers from each group (one broiler from each replicate) were randomly selected for sampling. Heparinized blood collected from the wing vein was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to gather plasma samples that were then stored at –80 °C until analysis. After that, the broilers were decapitated and eviscerated immediately. Jejunal tissues were rapidly collected and sections roughly 1.5 cm in length were sliced at the middle position and fixed in chilled 4% paraformaldehyde for morphometric evaluation. Approximately 20 cm sections of the jejunum were opened longitudinally at the same position and cleaned with an ice-cold phosphate buffer solution. Mucosa samples were collected by scraping a sterile glass microscope slide that was then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

Determination of diamine oxidase (DAO) activity and d-lactate content

The activity of DAO in the plasma samples was determined according to the specifications of a commercial kit obtained from the Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering (#A088-1-1; Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The kit for plasma d-lactate concentration was purchased from the AAT Bioquest (#AAT-13811; Sunnyvale, CA).

Jejunal morphology

The specimens of the jejunal tissues were first fixed in a paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h at room temperature. After that, they were dehydrated through an upgraded series of ethanol and xylene soaking, and then were embedded in paraffin blocks. Cross sections of the tissue segments were sliced at a thickness of 5 µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A rater blinded to the treatments measured the villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD) using an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) that was coupled with NIS-Elements 3.0 Imaging Software.

Analysis of jejunal redox status

Colorimetric kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering) were used for the determination of total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC; #A015-1-2), superoxide dismutase (SOD; #A001-1-2), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px; #A005-1-2) activities, as well as for reduced glutathione (GSH; #A006-1-1) and malondialdehyde (MDA; #A003-1-2) contents to evaluate jejunal antioxidant capacity and the severity of lipid peroxidation of broilers.

Messenger RNA quantification

Total RNA was removed from roughly 50 mg of jejunal mucosa through the process of adding 1.0 mL of TRIzol Reagent (#9109; TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, Liaoning, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA extracted pellets were washed with cold 75% ethanol twice, then were air-dried and dissolved in 50 μL of RNase-free water to ensure purity, concentration, and integrity for analysis. A NanoDrop ND-1000UV spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) was used to measure the purity and concentration of total RNA at 260 and 280 nm. Electrophoresis verified the RNA integrity on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with Ultra GelRed (#GR501-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology) was used to reverse-transcribe 1 μg of total RNA into complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Real-time PCR was conducted on a QuantStudio 5 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, CA) using a ChamQTM SYBR qPCR Master Mix Kit (#Q311-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The real-time PCR conditions were: preheat denature at 95 °C for 30 s, perform 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, then anneal at 60 °C for 30 s. At the end of the PCR procedure, melting curve analysis of the amplification products was performed following this process: one cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, then a temperature increase from 65 to 95 °C with a temperature change rate at 0.5 °C/s. The primers were designed using the Primer-Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Supplemental Table S2 presents details of the primer sequences for the target and reference genes toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), IL-1β, IL-10, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3), tight junction protein 1 (ZO-1), occludin (OCLN), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and β actin (ACTB). First, relative expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the reference gene, and then they were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Western blot analysis

The total and nuclear proteins of jejunal mucosal tissues were isolated using commercial kits obtained from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (#P0013B for total protein extraction; #P0028 for nuclear protein extraction; Nantong, Jiangsu, China). The protein content was quantified by a bicinchoninic acid protein quantification kit (#P0010; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Then, equal amounts of proteins were denatured for 5 min by boiling in an SDS–PAGE Sample Loading Buffer (#P0015; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). A 10% SDS–PAGE was used to separate samples that were then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk powder in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.2% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, membranes were washed twice with TBST and then incubated overnight along with appropriate primary antibodies at 4 °C. These antibodies were anti-nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) p65 (#10745-1-AP; Proteintech, Chicago, IL; 1:1,000 dilution), anti-tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α; #17590-1-AP; Proteintech; 1:750 dilution), anti-Histone H3 (#ab1791; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:3,000 dilution), and anti-ACTB (#60008-1-Ig; Proteintech; 1:2,000 dilution). Following incubation, the blots were triple washed then processed using corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. They were again triple washed for 5 min. After that, an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (#WBKLS0100; Millipore) was used to develop blots, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A Kodak-X-Omat film (Kodak Japan, Tokyo, Japan) on a DuPont Lighting plus intensifying screen highlighted the immunoreactive bands. A quantitative analysis was performed using the Gel-Pro Analyzer program (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Statistical analysis

Prior to LPS challenge, the ADG, ADFI, and G:F of broilers were analyzed by Student’s t-test using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (ver. 22.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). After LPS challenge, the significance and interaction of the main effects (LPS and Diet) were measured using two-way ANOVA with the general linear model procedure of SPSS software (ver. 22.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to separate the means after a one-way ANOVA test when the P-value of interaction of the main effects was significant at P < 0.05. Data are presented as means with their SE.

Results

Growth performance

Before the LPS challenge, administration of pterostilbene did not affect the ADG, ADFI, or G:F of broilers from 1 to 21 d of age (P > 0.05; Table 1). Compared with the nonchallenged broilers, LPS stimulation significantly decreased the BW gain of broilers at 24 h postinjection (P < 0.001). However, pterostilbene alleviated the reduction in BW gain in the LPS-injected broilers rather than the control broilers (P = 0.031).

Table 1.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on the growth performance of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers1

| Items2 | CON-SS | PT-SS | CON-LPS | PT-LPS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Diet | L × D | |||||

| Before LPS challenge (1 to 21 d of age) | |||||||

| ADG, g/d | 38.51 ± 0.83 | 38.84 ± 0.66 | 38.48 ± 1.11 | 38.94 ± 0.94 | — | 0.647 | — |

| ADFI, g/d | 54.56 ± 1.05 | 53.01 ± 0.78 | 54.36 ± 1.36 | 53.63 ± 1.26 | — | 0.307 | — |

| G:F, g/g | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | — | 0.085 | — |

| During LPS challenge (21 to 22 d of age) | |||||||

| BW gain, g/d | 50.00 ± 2.06a | 48.71 ± 4.22a | 20.98 ± 2.69c | 33.81 ± 2.83b | <0.001 | 0.073 | 0.031 |

1Values are means ± SE, n = 6.

2CON-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; CON-SS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and diet); LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PT-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; PT-SS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of sterile saline.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike lowercase, superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0.05) between groups.

Plasma DAO activity and d-lactate content

Administration of LPS-induced significant increases in plasma DAO activity (P = 0.014) and d-lactate content (P < 0.001) of broilers compared with the nontreated controls (Table 2). In contrast, pterostilbene treatment counteracted the increased DAO activity (P = 0.011) caused by LPS injection.

Table 2.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on plasma diamine oxidase activity and d-lactate content of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers1

| Items2 | CON-SS | PT-SS | CON-LPS | PT-LPS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Diet | L × D | |||||

| DAO, units/L | 23.57 ± 1.48b | 25.61 ± 2.69b | 38.12 ± 3.76a | 25.32 ± 2.05b | 0.014 | 0.054 | 0.011 |

| d-Lactate, μmol/L | 790.09 ± 76.25 | 696.40 ± 99.18 | 1353.34 ± 129.53 | 1081.44 ± 92.09 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.389 |

1Values are means ± SE, n = 6.

2CON-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; CON-SS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; DAO, diamine oxidase; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and diet); LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PT-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; PT-SS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of sterile saline.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike lowercase, superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0.05) between groups.

Jejunal morphology

Compared with the controls, LPS injection resulted in sharp declines in the jejunal VH (P < 0.001) and VH:CD (P < 0.001) of broilers (Table 3). Treatment with pterostilbene obviously increased the ratio of VH to CD (P = 0.018) in the jejunum of broilers compared with those that received a basal diet. No difference was observed for the jejunal CD among groups (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on the jejunal morphology of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers1

| Items2 | CON-SS | PT-SS | CON-LPS | PT-LPS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Diet | L × D | |||||

| VH, μm | 911.12 ± 63.16 | 972.03 ± 51.11 | 670.99 ± 22.38 | 803.67 ± 45.55 | <0.001 | 0.057 | 0.462 |

| CD, μm | 152.38 ± 10.71 | 158.06 ± 16.21 | 181.28 ± 14.82 | 164.96 ± 10.41 | 0.193 | 0.693 | 0.417 |

| VH:CD, μm/μm | 6.02 ± 0.30 | 6.32 ± 0.36 | 3.79 ± 0.22 | 4.91 ± 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.159 |

1Values are means ± SE, n = 6.

2CD, crypt depth; CON-LPS = broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; CON-SS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and Diet); LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PT-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; PT-SS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of sterile saline; VH, villus height; VH:CD, the ratio of villus height to CD.

Jejunal antioxidant function

Broilers exposed to LPS exhibited increases in GSH-Px activity (P = 0.022) and MDA content (P = 0.008) but showed a decrease in GSH concentration (P = 0.005) from the nontreated broilers (Table 4). Conversely, feeding a pterostilbene-supplemented diet to broilers dramatically increased GSH concentration (P = 0.017) and decreased MDA concentration (P = 0.023) in the jejunum compared with those given a basal diet. Also, pterostilbene supplementation reversed the LPS-induced increased SOD activity in the jejunum (P = 0.010). However, pterostilbene treatment had no effect on T-AOC and GSH-Px activities (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on the jejunal antioxidant function of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers1

| Items2 | CON-SS | PT-SS | CON-LPS | PT-LPS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Diet | L × D | |||||

| T-AOC, units/mg protein | 0.83 ± 0.10 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.072 | 0.364 | 0.624 |

| SOD, units/mg protein | 25.36 ± 3.45b | 30.99 ± 2.18ab | 40.25 ± 4.47a | 26.83 ± 2.95b | 0.127 | 0.261 | 0.010 |

| GSH-Px, units/mg protein | 4.78 ± 0.90 | 4.77 ± 1.25 | 8.52 ± 0.71 | 6.19 ± 1.19 | 0.022 | 0.273 | 0.274 |

| GSH, nmol/mg protein | 2.64 ± 0.13 | 2.99 ± 0.22 | 2.01 ± 0.14 | 2.55 ± 0.17 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.590 |

| MDA, nmol/mg protein | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.129 |

1Values are means ± SE, n = 6.

2CON-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; CON-SS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and Diet); LPS lipopolysaccharide; MDA, malondialdehyde; PT-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; PT-SS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of sterile saline; SOD, superoxide dismutase; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike lowercase, superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0.05) between groups.

Jejunal gene expression

Table 5 summarizes the expression levels of genes associated with inflammation and tight junction in the jejunum of the broilers. Compared with the nonchallenged broilers, LPS significantly increased the expression levels of IL-1β (P = 0.042) and NLRP3 (P = 0.019) but decreased mRNA abundance of ZO-1 (P = 0.002). However, pterostilbene supplementation decreased the expression of these genes (P < 0.05) and also increased the mRNA expression of OCLN (P = 0.024) in the jejunum. Neither the LPS challenge nor pterostilbene administration altered the mRNA abundance of TLR4 or IL-10 (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on the expression levels of jejunal genes related to inflammation and tight junction of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers1

| Items2 | CON-SS | PT-SS | CON-LPS | PT-LPS | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Diet | L × D | |||||

| TLR4 | 1.00 ± 0.36 | 0.68 ± 0.14 | 1.58 ± 0.24 | 0.92 ± 0.19 | 0.117 | 0.064 | 0.500 |

| IL-1β | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 1.62 ± 0.19 | 0.79 ± 0.18 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.148 |

| IL-10 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.18 ± 0.21 | 1.01 ± 0.17 | 1.09 ± 0.17 | 0.823 | 0.453 | 0.767 |

| NLRP3 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.15 | 4.01 ± 1.30 | 1.25 ± 0.23 | 0.019 | 0.041 | 0.067 |

| ZO-1 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.38 ± 0.22 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.692 |

| OCLN | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.16 | 1.16 ± 0.13 | 0.241 | 0.024 | 0.676 |

1Values are means ± SE, n = 6

2CON-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; CON-SS, broilers fed a basal diet and an injection of sterile saline; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and Diet); LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; OCLN, occludin; PT-LPS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of lipopolysaccharide; PT-SS, broilers fed a basal diet supplemented with 400 mg/kg pterostilbene and an injection of sterile saline; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; ZO-1, tight junction protein 1.

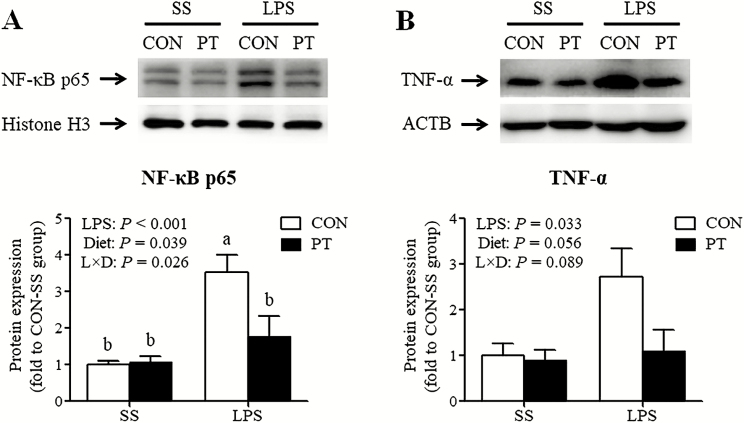

Jejunal NF-κB p65 and TNF-α protein expression

Compared with untreated broilers, birds treated with LPS showed a sharp rise in the expression abundance of nuclear NF-κB p65 protein (P < 0.001) in the jejunal mucosa (Figure 1A). A similar effect was observed for the content of jejunal TNF-α protein (P = 0.033) in the LPS-stimulated broilers compared with the untreated controls (Figure 1B). In contrast, pterostilbene supplementation inhibited the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 (P = 0.039). In addition, the LPS and diet had a significant interaction effect on the nuclear protein accumulation of NF-κB p65 (P = 0.026); the LPS-treated broilers fed a pterostilbene-supplemented diet had a significant decrease in nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 in the jejunum.

Figure 1.

Effect of dietary pterostilbene supplementation on the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor κ B p65 (A) and the protein expression of tumor necrosis factor α (B) in the jejunum of lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers. The column and its bar represented the means value and SE (n, 6 birds/group), respectively. a,bMean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P < 0.05) between groups. CON, broilers fed a basal diet from 1 to 22 d of age; L × D = the interaction effect of main effects (LPS and Diet); LPS, broilers received an injection of lipopolysaccharide at 21 d of age; NF-κB, nuclear factor κ B; PT, broilers fed a pterostilbene-supplemented diet from 1 to 22 d of age; SS, broilers received an injection of sterile saline at 21 d of age; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that broilers that consumed a pterostilbene-supplemented diet exhibited an increased BW gain during a 24-h post-LPS stimulation. The beneficial effect shown in this study may be associated with the ability of pterostilbene to improve intestinal morphology and to alleviate mucosa damage. Also, pterostilbene supplementation may facilitate the participation and coordination of jejunal immune and antioxidant defense systems of the LPS-treated broilers, which may help in elevating the absorption efficiency of nutrients and health status of the small intestines.

So far, no literature is available describing the potential effect of pterostilbene on animal growth performance; however, recent reports have demonstrated that resveratrol, the parent compound of pterostilbene, is capable of improving the growth performance of broilers (Liu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017a; He et al., 2019). Liu et al. (2014) showed that resveratrol could act as a feed additive in the diet of broilers to alleviate the compromised growth performance induced by cyclic heat stress. Likewise, an increase of BW was observed in heat-stressed broilers upon supplementation of diets with resveratrol (Zhang et al., 2017a). The findings of the current study substantiate the results from previous studies and further confirm that resveratrol and its analogs may act as a promising anti-stress supplement with which to alleviate growth performance descent of broilers under stressful circumstances.

Intestinal mucosa structure is the primary factor in absorption of nutrients and protection of the host from the internal environment of the gut. There is plenty of evidence that LPS stimulation contributes to the impairment of intestinal health and barrier function (Zhu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015; Deng et al., 2017). The findings of the present study indicate that the jejunal morphology was damaged by LPS challenge, corresponding to the increases in plasma DAO activity and d-lactate content, which have been suggested as blood indicators in the evaluation of damage of the intestinal mucosa (Fukudome et al., 2014). Diamine oxidase is a highly active intracellular enzyme amply expressed in the upper chorial cells of the intestinal mucosa. The impairment of intestinal mucosa can induce the leakage of DAO from villus tips into blood circulation, and therefore circulatory DAO activity has been recognized as a sensitive parameter to monitor the extent of intestinal injury (Luk et al., 1983; Wolvekamp and De Bruin, 1994). Available evidence obtained from various animal studies has demonstrated that an increase of plasma DAO activity occurs when intestinal mucosa is damaged (Chen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). d-Lactate, another marker, is a metabolic end product of intestinal bacteria that can pass through intestinal epithelium into blood circulation under the conditions of intestinal barrier failure, resulting in an elevation of its concentration in the blood (Szalay et al., 2003). Therefore, the results of our study indicate that LPS challenge is detrimental to intestinal morphology and barrier function, and this may be a causal factor for the compromised growth performance of the LPS-challenged broilers.

Toll-like receptor 4 has been identified as a major receptor for LPS stimulation with the participation of cluster of differentiation 14 and myeloid differentiation 2 (Nagai et al., 2002), which in turn induces the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway, regulating the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators (Kagan and Medzhitov, 2006). Nuclear factor κB is an amply expressed transcription factor that primarily regulates immunity and inflammatory responses. Since a well-regulated inflammatory process is vital for intestinal homeostasis, while an uncontrolled, excessive inflammatory response can cause injury, like lipid peroxidation, to the intestines. In this study, we observed a substantial increase of nuclear NF-κB p65 protein in the jejunum of LPS-treated broilers along with an accompanying increase in the production of TNF-α and IL-1β, which may contribute to severe intestinal inflammation and concomitant oxidative damage. It is noteworthy that LPS stimulation resulted in increased GSH-Px activity in the present research; nevertheless, this increase may not be sufficient to counteract the lipid peroxidation in the jejunum of broilers with evidence of an increased MDA content.

In addition to its role in intestinal inflammation, LPS stimulation also affects the expression and structure of intestinal junction proteins. Growing evidence demonstrates that bacterial LPS disturbs the expression levels of intestinal tight junctions, including ZO-1, OCLN, and claudin family members (Park et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2017). Similarly, a reduced ZO-1 expression was also seen in the jejunum of broilers exposed to the LPS challenge. Moreover, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines arising from LPS-induced inflammation, such as TNF-α, has a negative effect on the structure of junction proteins (Wang et al., 2005). Such effects may be associated with the disruption of intestinal permeability in the LPS-treated animals (Gu et al., 2011; de Souza Khatlab et al., 2019), since the paracellular permeability and barrier integrity of intestines are generally regulated by tight junction complexes between epithelial cells. Collectively, the underlying mechanisms involved in the increased levels of plasma DAO and d-lactate may be the excessive intestinal inflammation and the defective expression of junction proteins caused by LPS stimulation.

Several studies have shown that resveratrol and its analogs can modulate the barrier function of the gastrointestinal tract (Ling et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2016; Lv et al., 2018). An experiment by Bereswill et al. (2010) assessed the protective effect of resveratrol in a murine model of acute intestinal inflammation and showed that oral treatment with resveratrol prevented bacterial translocation by maintaining intestinal integrity. Similarly, an in vitro study by Ling et al. (2016) demonstrated that pretreatment of cell monolayers with resveratrol preserved gut barrier function by strengthening the physical barrier. Polydatin, a glucoside of resveratrol, was also found to attenuate colonic oxidative damage and epithelial barrier disruption in rats (Lv et al., 2018). In the current research, we found that pterostilbene, the dimethyl ether analog of resveratrol, effectively reversed the increased plasma DAO activity caused by LPS stimulation, corresponding to the improvements in the jejunal VH:CD ratio as well as the mRNA expression of ZO-1 and OCLN. This suggests that pterostilbene as a protectant could alleviate gut mucosal damage and preserve jejunal morphological structure of broilers under stressful circumstances.

Our results showed that pterostilbene protected the chickens from LPS-induced intestinal inflammation by inactivating NF-κB signals and suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators. The nuclear accumulation of p65 protein, a key member of the NF-κB family, was vastly reduced from pterostilbene treatment, which is directly responsible for the transcriptional activation of various pro-inflammatory cytokines (Barnes and Karin, 1997). This observed decrease may partially explain the decreased mRNA abundance of IL-1β in the jejunum of birds receiving a pterostilbene-supplemented diet. This is supported by the findings obtained from several in vitro studies wherein pterostilbene was found to exhibit strong anti-inflammatory properties under stressful conditions (Paul et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016b). This was shown by the inhibition of transcription and production of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Paul et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2013); the downregulated expression levels of pro-inflammatory enzymes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 (Paul et al., 2009); and the prevention of monocyte adhesion (Liu et al., 2016b).

Interestingly, the mRNA abundance of NLRP3 was also decreased after pterostilbene supplementation in this study. NLRP3 is a key component of the inflammasome, which is an intracellular danger sensor of the innate immune system. Once NLRP3 is activated, it triggers caspase-1-dependent processing of inflammatory mediators, which in turn promotes the maturation of active pro-inflammatory cytokines and the initiation of pyroptotic cell death (Menu and Vince, 2011). Early reports have revealed that NLRP3 may play a role in the pathogenesis of intestinal disorders and inflammatory diseases, in which the NLRP3 inflammasome is abnormally activated (Bauer et al., 2010; Ozaki et al., 2015). In the current work, the mechanism by which pterostilbene normalized NLRP3 expression may be involved in its regulatory role in the activity of NF-κB, which is responsible for regulating NLRP3 transcription through binding to the NF-κB sites in the NLRP3 promoter region (Qiao et al., 2012). The current observation may therefore provide additional support for the benefit of pterostilbene in attenuating intestinal inflammation and verify the involvement of the NF-κB signals in this process.

The beneficial effect of pterostilbene in improving intestinal integrity may also be attributed to its resistance to oxidative stress. The antioxidant activity of resveratrol and its analog, pterostilbene, may ascribe to their ability as a free radical scavenger as they contain hydroxyl groups. Of note, replacement of two hydroxyl groups with methoxy groups endows pterostilbene with a preferable antioxidant capacity (Lee et al., 2003). In our study, the GSH depletion and MDA overproduction were observed with the LPS challenge; however, administration with pterostilbene effectively restored GSH and MDA contents almost to the control levels. In agreement with our findings, an increased MDA accumulation in the acetaminophen-treated rats was attenuated by pterostilbene pretreatment (El-Sayed et al., 2015). Chiou et al. (2011) found that pterostilbene suppressed the expression of aldose reductase, a biomarker of oxidative stress, and facilitated the transcriptional activities of glutathione reductase and heme oxygenase-1 via the upregulation of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (NRF2). In fact, pterostilbene has been identified as a potent activator of NRF2 through a reporter protein complementation imaging assay by Ramkumar et al. (2013). Thus, future studies are required to fully elucidate the mechanism(s) through which pterostilbene could regulate the intestinal redox signals of LPS-challenged broilers.

In conclusion, the currently available data reveal that pterostilbene administration has beneficial roles in improving BW gain, preserving intestinal morphology, and attenuating intestinal inflammation and mucosal damage of broiler chickens under immunological stress. Such effects may have an important implication for using pterostilbene toward the development of a promising immunomodulator in poultry production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31802094), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant nos. BK20180531 and BK20190537), the Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China (grant nos. 2018M632320 and 2019T120436), and the Open Project of Shanghai Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology (grant no. klab201710).

Conflict of interest statementThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Athar M., Back J. H., Tang X., Kim K. H., Kopelovich L., Bickers D. R., and Kim A. L.. . 2007. Resveratrol: a review of preclinical studies for human cancer prevention. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 224:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. J., and Karin M.. . 1997. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer C., Duewell P., Mayer C., Lehr H. A., Fitzgerald K. A., Dauer M., Tschopp J., Endres S., Latz E., and Schnurr M.. . 2010. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut. 59:1192–1199. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereswill S., Muñoz M., Fischer A., Plickert R., Haag L. M., Otto B., Kühl A. A., Loddenkemper C., Göbel U. B., and Heimesaat M. M.. . 2010. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin and simvastatin in acute small intestinal inflammation. PLoS One. 5:e15099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Rimando A., Pallas M., Camins A., Porquet D., Reeves J., Shukitt-Hale B., Smith M. A., Joseph J. A., and Casadesus G.. . 2012. Low-dose pterostilbene, but not resveratrol, is a potent neuromodulator in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 33:2062–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Mao X., He J., Yu B., Huang Z., Yu J., Zheng P., and Chen D.. . 2013. Dietary fibre affects intestinal mucosal barrier function and regulates intestinal bacteria in weaning piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 110:1837–1848. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou Y. S., Tsai M. L., Nagabhushanam K., Wang Y. J., Wu C. H., Ho C. T., and Pan M. H.. . 2011. Pterostilbene is more potent than resveratrol in preventing azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon tumorigenesis via activation of the NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated antioxidant signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59:2725–2733. doi: 10.1021/jf2000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Q. Y., Yeo S. C. M., Ho P. C., Tanaka Y., and Lin H. S.. . 2014. Pterostilbene surpassed resveratrol for anti-inflammatory application: potency consideration and pharmacokinetics perspective. J. Funct. Foods. 11:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.10.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng B., Wu J., Li X., Men X., and Xu Z.. . 2017. Probiotics and probiotic metabolic product improved intestinal function and ameliorated LPS-induced injury in rats. Curr. Microbiol. 74:1306–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1318-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed el. -. S. M., Mansour A. M., and Nady M. E.. . 2015. Protective effects of pterostilbene against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 29:35–42. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukudome I., Kobayashi M., Dabanaka K., Maeda H., Okamoto K., Okabayashi T., Baba R., Kumagai N., Oba K., Fujita M., . et al. 2014. Diamine oxidase as a marker of intestinal mucosal injury and the effect of soluble dietary fiber on gastrointestinal tract toxicity after intravenous 5-fluorouracil treatment in rats. Med. Mol. Morphol. 47:100–107. doi: 10.1007/s00795-013-0055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L., Li N., Gong J., Li Q., Zhu W., and Li J.. . 2011. Berberine ameliorates intestinal epithelial tight-junction damage and down-regulates myosin light chain kinase pathways in a mouse model of endotoxinemia. J. Infect. Dis. 203:1602–1612. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Li S., Arowolo M. A., Yu Q., Chen F., Hu R., and He J.. . 2019. Effect of resveratrol on growth performance, rectal temperature and serum parameters of yellow-feather broilers under heat stress. Anim. Sci. J. 90:401–411. doi: 10.1111/asj.13161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. L., Lin Y. J., Ho C. T., and Yen G. C.. . 2013. The inhibitory effect of pterostilbene on inflammatory responses during the interaction of 3T3-L1 adipocytes and RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61:602–610. doi: 10.1021/jf304487v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. C., and Medzhitov R.. . 2006. Phosphoinositide-mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 125:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboh A. A., Hang S. Q., Khan M. A., and Zhu W. Y.. . 2016. In vivo immunomodulatory effects of plant flavonoids in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers. Animal. 10:1619–1625. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116000562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic I. M., Muzzio M., Huang Z., Thompson T. N., and McCormick D. L.. . 2011. Pharmacokinetics, oral bioavailability, and metabolic profile of resveratrol and its dimethylether analog, pterostilbene, in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 68:593–601. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1525-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatlab A. S., Del Vesco A. P., de Oliveira Neto A. R., Fernandes R. P. M., and Gasparino E.. . 2019. Dietary supplementation with free methionine or methionine dipeptide mitigates intestinal oxidative stress induced by Eimeria spp. challenge in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 10:58. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0353-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuru R., Kandula V., Rai U., Prakash S., Xia Z., and Singh S.. . 2018. Pterostilbene decreases cardiac oxidative stress and inflammation via activation of AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in fructose-fed diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 32:147–163. doi: 10.1007/s10557-018-6780-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Lee S. H., Gadde U. D., Oh S. T., Lee S. J., and Lillehoj H. S.. . 2017. Dietary Allium hookeri reduces inflammatory response and increases expression of intestinal tight junction proteins in LPS-induced young broiler chicken. Res. Vet. Sci. 112:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K., Lee S. Y., In S. W., Choi H. K., Lim M. A., Chung K. H., and Chung H. S.. . 2003. Lidocaine intoxication: two fatal cases. Arch. Pharm. Res. 26:317–320. doi: 10.1007/bf02976962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang H., Chen Y. P., Yang M. X., Zhang L. L., Lu Z. X., Zhou Y. M., and Wang T.. . 2015. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens supplementation alleviates immunological stress and intestinal damage in lipopolysaccharide-challenged broilers. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 208:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. S., Yue B. D., and Ho P. C.. . 2009. Determination of pterostilbene in rat plasma by a simple HPLC-UV method and its application in pre-clinical pharmacokinetic study. Biomed. Chromatogr. 23:1308–1315. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K. H., Wan M. L., El-Nezami H., and Wang M.. . 2016. Protective capacity of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound, against deoxynivalenol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29:823–833. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Fan C., Yu L., Yang Y., Jiang S., Ma Z., Hu W., Li T., Yang Z., Tian T., . et al. 2016b. Pterostilbene exerts an anti-inflammatory effect via regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress in endothelial cells. Cytokine. 77:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Fu C., Yan M., Xie H., Li S., Yu Q., He S., and He J.. . 2016a. Resveratrol modulates intestinal morphology and HSP70/90, NF-κB and EGF expression in the jejunal mucosa of black-boned chickens on exposure to circular heat stress. Food Funct. 7:1329–1338. doi: 10.1039/c5fo01338k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Hao H., Xie H., Lv H., Liu C., and Wang G.. . 2009. Oxidative demethylenation and subsequent glucuronidation are the major metabolic pathways of berberine in rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 98:4391–4401. doi: 10.1002/jps.21721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. L., He J. H., Xie H. B., Yang Y. S., Li J. C., and Zou Y.. . 2014. Resveratrol induces antioxidant and heat shock protein mRNA expression in response to heat stress in black-boned chickens. Poult. Sci. 93:54–62. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., and Schmittgen T. D.. . 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk G. D., Bayless T. M., and Baylin S. B.. . 1983. Plasma postheparin diamine oxidase. Sensitive provocative test for quantitating length of acute intestinal mucosal injury in the rat. J. Clin. Invest. 71:1308–1315. doi: 10.1172/jci110881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv T., Shen L., Yang L., Diao W., Yang Z., Zhang Y., Yu S., and Li Y.. . 2018. Polydatin ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by decreasing oxidative stress and apoptosis partially via Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 64:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menu P., and Vince J. E.. . 2011. The NLRP3 inflammasome in health and disease: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 166:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04440.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Akashi S., Nagafuku M., Ogata M., Iwakura Y., Akira S., Kitamura T., Kosugi A., Kimoto M., and Miyake K.. . 2002. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat. Immunol. 3:667–672. doi: 10.1038/ni809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H., Tsunooka N., Yamamoto Y., Yoshida M., Nakata T., and Kawachi K.. . 2009. Intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced bacterial translocation and lung injury in atherosclerotic rats with hypoadiponectinemia. Surgery. 145:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanthakumar N., Meng D., Goldstein A. M., Zhu W., Lu L., Uauy R., Llanos A., Claud E. C., and Walker W. A.. . 2011. The mechanism of excessive intestinal inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis: an immature innate immune response. PLoS One. 6:e17776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC 1994. Nutrient requirements of poultry. 9th rev. ed.Washington, DC: National Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki E., Campbell M., and Doyle S. L.. . 2015. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 8:15–27. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S51250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Rimando A. M., Lee H. J., Ji Y., Reddy B. S., and Suh N.. . 2009. Anti-inflammatory action of pterostilbene is mediated through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in colon cancer cells. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.). 2:650–657. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E. J., Thomson A. B., and Clandinin M. T.. . 2010. Protection of intestinal occludin tight junction protein by dietary gangliosides in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 50:321–328. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ae2ba0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perecko T., Drabikova K., Rackova L., Ciz M., Podborska M., Lojek A., Harmatha J., Smidrkal J., Nosal R., and Jancinova V.. . 2010. Molecular targets of the natural antioxidant pterostilbene: effect on protein kinase C, caspase-3 and apoptosis in human neutrophils in vitro. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. Suppl. 2:84–90. doi: 10.1159/000287255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y., Wang P., Qi J., Zhang L., and Gao C.. . 2012. TLR-induced NF-κB activation regulates NLRP3 expression in murine macrophages. FEBS Lett. 586:1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar K. M., Sekar T. V., Foygel K., Elango B., and Paulmurugan R.. . 2013. Reporter protein complementation imaging assay to screen and study Nrf2 activators in cells and living animals. Anal. Chem. 85:7542–7549. doi: 10.1021/ac401569j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roupe K. A., Remsberg C. M., Yáñez J. A., and Davies N. M.. . 2006. Pharmacometrics of stilbenes: seguing towards the clinic. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 1:81–101. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin K., Orhan C., Akdemir F., Tuzcu M., Iben C., and Sahin N.. . 2012. Resveratrol protects quail hepatocytes against heat stress: modulation of the Nrf2 transcription factor and heat shock proteins. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.). 96:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2010.01123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. B., Piao X. S., Kim S. W., Wang L., and Liu P.. . 2010. The effects of berberine on the magnitude of the acute inflammatory response induced by Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 89:13–19. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderholm J. D., and Perdue M. H.. . 2001. Stress and gastrointestinal tract. II. Stress and intestinal barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280:G7–G13. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.1.G7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar M., Suganthi R. U., and Thammiaha V.. . 2015. Effect of dietary resveratrol in ameliorating aflatoxin B1-induced changes in broiler birds. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 99:1094–1104. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalay L., Umar F., Khadem A., Jafarmadar M., Fürst W., Ohlinger W., Redl H., and Bahrami S.. . 2003. Increased plasma D-lactate is associated with the severity of hemorrhagic/traumatic shock in rats. Shock. 20:245–250. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200309000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Graham W. V., Wang Y., Witkowski E. D., Schwarz B. T., and Turner J. R.. . 2005. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am. J. Pathol. 166:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Li Z., Han Q., Guo Y., Zhang B., and D’inca R.. . 2016. Dietary live yeast and mannan-oligosaccharide supplementation attenuate intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction induced by Escherichia coli in broilers. Br. J. Nutr. 116:1878–1888. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. F., Li Y. L., Shen J., Wang S. Y., Yao J. H., and Yang X. J.. . 2015. Effect of Astragalus polysaccharide and its sulfated derivative on growth performance and immune condition of lipopolysaccharide-treated broilers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 76:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolvekamp M. C. J., and De Bruin R. W. F.. . 1994. Diamine oxidase: an overview of historical, biochemical and functional aspects. Digest. Dis. 12:2–14. doi: 10.1159/000171432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Rath N. C., Huff G. R., Huff W. E., and Balog J. M.. . 2000. Effects of Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide on broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 79:33–40. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z., Yang Y., Dai X., Xu S., Li T., Zhang Q., Zhao K. S., and Chen Z.. . 2016. Polydatin ameliorates injury to the small intestine induced by hemorrhagic shock via SIRT3 activation-mediated mitochondrial protection. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 20:645–652. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2016.1177023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang L., Zhao X. H., Chen X. Y., Yang L., and Geng Z. Y.. . 2017b. Dietary resveratrol supplementation prevents transport-stress-impaired meat quality of broilers through maintaining muscle energy metabolism and antioxidant status. Poult. Sci. 96:2219–2225. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhang L., Zeng X., Zhou L., Cao G., and Yang C.. . 2016. Effects of dietary supplementation of probiotic, Clostridium butyricum, on growth performance, immune response, intestinal barrier function, and digestive enzyme activity in broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coli K88. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 7:3. doi: 10.1186/s40104-016-0061-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., and Zhang Y.. . 2016. Pterostilbene, a novel natural plant conduct, inhibits high fat-induced atherosclerosis inflammation via NF-κB signaling pathway in Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) deficient mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 81:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhao X. H., Yang L., Chen X. Y., Jiang R. S., Jin S. H., and Geng Z. Y.. . 2017a. Resveratrol alleviates heat stress-induced impairment of intestinal morphology, microflora, and barrier integrity in broilers. Poult. Sci. 96:4325–4332. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H. L., Liu Y. L., Xie X. L., Huang J. J., and Hou Y. Q.. . 2013. Effect of L-arginine on intestinal mucosal immune barrier function in weaned pigs after Escherichia coli LPS challenge. Innate Immun. 19:242–252. doi: 10.1177/1753425912456223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.