Abstract

Caudate nucleus volume is enlarged in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is associated with restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs). However, the trajectory of caudate nucleus volume in RRBs of young children remains unclear. Caudate nucleus volume was measured in 36 children with ASD and 18 matched 2–3-year-old subjects with developmentally delayed (DD) at baseline (Time 1) and at 2-year follow-up (Time 2). The differential growth rate in caudate nucleus volume was calculated. Further, the relationships between the development of caudate nucleus volume and RRBs were analyzed. Our results showed that caudate nucleus volume was significantly larger in the ASD group at both time points and the magnitude of enlargement was greater at Time 2. The rate of caudate nucleus growth during this 2-year interval was faster in children with ASD than DD. Right caudate nucleus volume growth was negatively correlated with RRBs. Findings from this study suggest developmental abnormalities of caudate nucleus volume in ASD. Longitudinal MRI studies are needed to explore the correlation between atypical growth patterns of caudate nucleus and phenotype of RRBs.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Autism spectrum disorder, Caudate nucleus development, Restricted, Repetitive behavior

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by qualitative impairments in social interaction as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors (RRBs). RRBs are the core symptoms of ASD, and are diagnostic of autism, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), RRBs remain the key diagnostic criteria. The category of RRBs is very broad, and includes such behaviors as motor stereotypies (e.g., turns in circles), repetitive use of parts of objects (e.g., buttons on clothes), adherence to nonfunctional routines (e.g., insists on taking certain routes/paths), and compulsive behavior (e.g., need for things to be even or symmetrical).

Increasing evidence suggests that RRBs first emerge in toddlers and preschoolers, even as early as 8 months of age in children later diagnosed with ASD (Watson et al., 2007, Kim and Lord, 2010). The wide variety of repetitive behaviors also occur in typically developing (TD) young children, including intellectual disability, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), Parkinson's disease, and Tourette syndrome (TS) (Evans et al., 1997, Boyer and Liénard, 2006). However, difficulties in classification and quantification complicate systematic research of repetitive behavior in distinct neuropsychiatric disorders (Langen et al., 2011). Several studies have found increased RRBs in both adults and young children even as young as 18–24 months of age with ASD compared with developmentally delayed (DD) controls (Richler et al., 2007, Morgan et al., 2008).

Previous structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of individuals with clinical disorders investigating neuroanatomical correlates of repetitive behavior has suggested changes in basal ganglia, particularly caudate and putamen. For example, results of imaging studies with medication-naive TS patients, have indicated reductions in caudate and putamen volumes (Bloch et al., 2005) although increases (Fredericksen et al., 2002) and similar volumes (Zimmerman et al., 2000) have also been reported. In addition, smaller caudate nucleus volume in children predicted increased severity of TS symptoms in adulthood (Bloch et al., 2005, Hyde et al., 1995). In terms of OCD, Radua and Mataix-Cols (2009) conducted a voxel-wise meta-analysis using 12 MRI studies, which showed increased gray matter volume in basal ganglia, including putamen and caudate nucleus. This analysis also indicated a correlation between OCD severity and increased magnitude of basal ganglia volume.

However, previous cross-sectional structural MRI studies exploring the neurobiology of RRBs are limited in ASD. Sears et al. (1999) found a significant negative association between caudate nucleus volume and three Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI) repetitive behavior items: difficulties with minor changes in routine, compulsions/rituals, and complex mannerisms. Hollander et al. (2005) reported increased right caudate nucleus volume in ASD, which were positively correlated with higher order RRBs of ADI. The same pattern was observed when putamen volumes were correlated with repetitive behavior scores. Using adult and adolescent samples, Rojas et al. (2006) largely replicated these results in a later study. In two studies using a wider age range (7–25 years), Langen et al., 2007, Langen et al., 2009 also reported larger caudate nucleus volume in highly functional ASD individuals compared with typically developing controls. These investigators reported either no significant correlations with Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) repetitive behavior scores (Langen et al., 2007) or a negative correlation with insistence on sameness cluster (Langen et al., 2009). Estes et al. (2011), however, examined basal ganglial morphometry in 3–4-year-old children with ASD compared with DD and TD controls. After controlling for cerebral volume no differences in caudate nucleus volume was found between ASD and TD children but the difference between ASD and DD participants persisted. Further, no systematic relationship between caudate nucleus volume and RRBs was observed for any of the three measures of RRBs. This observation was at odds with the recent results of Wolff et al. (2013) who reported that the compulsive and ritual subscales of Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised were significantly positively associated with caudate nucleus volume in 3–6-year-old ASD children. To date, in the longitudinal study of caudate nucleus development in autism, Langen et al. (2014) reported that an increase in the growth rate of striatal structures, especially caudate nucleus in individuals with autism mean age was 9.9, compared with typically developing controls. Faster striatal growth was correlated with more severe RRBs (insistence on sameness). Abnormally high caudate volumes in early childhood, typically between 10 and 15 years of age, and then abnormal decline in adulthood were found in 100 male participants with ASD compared with 56 typically developing controls scanned over an 8-year period (Lange et al., 2015).

In general, most cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have focused on adults or school-age children with ASD and the early trajectory of caudate nucleus from infancy through middle childhood remains unclear. It is necessary to determine whether young children with ASD have greater volumes and atypical growth patterns of caudate nucleus than other children, and whether volumes of caudate nucleus correlate with RRBs. Therefore, in the present longitudinal study, we evaluated caudate nucleus development during a 2-year interval in 2–3-year-old children with ASD and DD subjects. The following hypotheses were tested:

-

1.

Caudate nucleus is enlarged in ASD children compared with DD children.

-

2.

The ASD sample exhibits changes in early developmental growth trajectory of caudate nucleus; and

-

3.

Caudate nucleus morphological growth is correlated with RRBs.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We included data from the original sample of approximately 116 scans in our ongoing 2-year longitudinal neuroimaging imaging project. Data included: (1) two neuroimaging datasets; (2) a consistent diagnosis at both times and (3) good quality scans. Eight scans were excluded. MRI scans were acquired in 54 individuals at both time points individually: 36 with ASD and 18 with DD matched for gender, age, developmental quotient (DQ) and intelligence quotient (IQ) (see Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing Brain Hospital of Nanjing Medical University in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Participants: clinical demographics.

| ASD (M ± SD) | DD (M ± SD) | t/x2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 36 | 18 | ||

| Gender (male:female) | 30:6 | 13:5 | 0.913 | 0.339 |

| Δ in age: (years) | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | −1.098 | 0.277 |

| Time 1 | ||||

| Age (years) | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.195 | 0.238 |

| DQ | 66.22 ± 9.6 | 66.18 ± 15.4 | 0.008 | 0.993 |

| ADI-R: Social Deficits | 21.8 ± 5.8 | 15.1 ± 6.5 | 3.785 | <0.001*** |

| ADI-R: Abnormalities in Communication | 12.6. ± 4.6 | 8.1 ± 4.8 | 3.247 | 0.002** |

| ADI-R: Ritualistic-Repetitive Behavior | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 4.268 | <0.001*** |

| Higher order RRBs | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 2.230 | 0.030* |

| Lower order RRBs | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 3.065 | 0.004** |

| Time 2 | ||||

| Age (years) | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | <0.001 | 1.000 |

| IQ | 89.2 ± 27.87 | 80.3 ± 32.3 | 0.886 | 0.382 |

| ADI-R: Social Deficits | 19.7 ± 5.5 | 15.1 ± 7.6 | 2.212 | 0.033* |

| ADI-R: Abnormalities in Communication | 13.1 ± 4.9 | 8.2 ± 5.1 | 2.904 | 0.006** |

| ADI-R: Ritualistic-Repetitive Behavior | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 3.790 | <0.001*** |

| Higher order RRBs | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 2.674 | 0.010* |

| Lower order RRBs | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 2.532 | 0.015* |

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DD, developmentally delayed; DQ, developmental quotient; IQ, intelligence quotient; ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; Δ in age, the interval between two scans.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Subjects with ASD based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR) diagnostic criteria as well as standardized clinical assessments including the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al., 1997) were handled by licensed child and adolescent psychiatrists. Children in the DD group did not meet the criteria for ASD, but demonstrated delay in intellectual ability. Subjects with any systemic diseases, a family history of head injury, genetic syndromes, neurological disorders or psychiatric illness were excluded from participation.

2.2. Assessments

Developmental quotient, intelligence quotient and RRBs were evaluated using the following measures by a specifically trained rater.

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-Chinese Version (BSID-C, Yi et al., 1993) is a standardized instrument designed to assess the infant level of development. The instrument yields a Mental Developmental Index (MDI) score and a Psychomotor Developmental Index (PDI) score from which motor age and cognitive age can be obtained, respectively. The DQ is a ratio of the functional age to the chronological age calculated using the following formula: DQ = ((motor age + cognitive age)/(chronological age) × 2) × 100.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT, Shanghai Institute of Pediatrics, 1985) is a receptive vocabulary test in which the children point to one of four pictures on a page that is named by the examiner. The total score can be converted to a percentile rank, mental age, and an IQ score.

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R, Lord et al., 1997), used to diagnose ASD in children and adults, has demonstrated validity and reliability in assessing very young children (Richler et al., 2007). The ADI-R is a standardized parent interview that assesses social reciprocity, communication and RRBs, with each item rated on a 3-point scale (0, 1, 2). The RRBs domain includes four sub-domains defined as: C1, encompassing preoccupation or circumscribed pattern of interest; C2, compulsive adherence to nonfunctional routines or rituals; C3, stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms; and C4, preoccupation with part-objects or nonfunctional elements of materials. C1 and C2 domains reflect the higher order or “insistence on sameness” factor, whereas C3 and C4 reflect the lower order or repetitive sensory motor behaviors (Hollander et al., 2005).

2.3. Image acquisition

MRI scans were performed on a 3.0 T scanner (Siemens, Germany) using a birdcage gradient head coil. Before MRI scan, each subject was sedated using 10% chloral hydrate with parental consent. The head of the participant was gently restrained with foam cushions. High-resolution T1-weighted images were obtained using a three-dimensional spoiled gradient recalled-echo (SPGR) pulse sequence with the following scanning parameters: TR = 2530 ms, TE = 3.34 ms, flip angle = 7°, inversion time = 1100 ms, FOV = 256 mm × 256 mm, matrix = 256 × 192, the slice thickness = 1.33 mm, total scanning time is 8.7 min. The head was positioned parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure (AC–PC) plane.

2.4. Tracing for caudate nucleus and intracranial volume

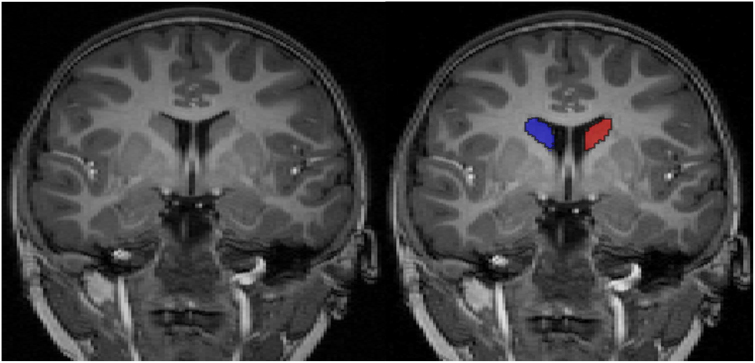

Caudate nucleus segmentation was performed with ITK-SNAP version 1.4, a semi-automated 3D segmentation tool by an experienced rater blinded to the clinical data and supervised by a professional neuroradiologist. Details of complete caudate nucleus semi-automated tracing protocol are described in prior publications (http://ibis-network.org/unc/mri/roiprotocols.htm). Briefly, however, controlled by a user-defined threshold window, initialization, and propagation parameters, the 3D segmentation of snap automatically finds tissue boundaries and labels the structure of interest (as identified by initialization). The output segmentation label can then be manually edited according to manual segmentation protocol. Segmentation of the caudate nucleus in coronal view is displayed in Fig. 1. Intrarater reliabilities estimated using intraclass correlation coefficients was 0.95 for caudate nucleus.

Fig. 1.

Caudate nucleus (left/right) in the coronal plane is shown in blue and red. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Intracranial volume (ICV) was determined from the T1-weighted MRI images using an automated method within Freesurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), an automated parcellation program. Briefly, Freesurfer is a fully automated method used to process talairach alignment, intensity normalization (Sled et al., 1998), removal of skull and non-brain tissue with a hybrid watershed/surface deformation procedure (Segonne et al., 2007), automated Talairach transformation, and segmentation of the subcortical white matter and deep gray matter volumetric structures (Fischl et al., 2002, Fischl et al., 2004). This software provides automated brain segmentation of structures and enables determination of brain volumes in a large number of subjects (Fischl et al., 2002, Morey et al., 2009, Pardoe et al., 2009).

2.5. Statistical analysis

2.5.1. Clinical demographics and RRBs scores

Group differences in age, gender, DQ, IQ and ADI-R scores were performed using a series of t-test or chi-square analyses at the baseline and 2-year follow-up.

2.5.2. Cross-sectional analyses of caudate nucleus at Time 1 and Time 2

Two-tailed, independent, two-sample t-tests were used to test group differences in caudate nucleus volume. ANCOVA was performed with ICV as an additional covariate at the baseline and 2-year follow-up, respectively.

2.5.3. Development of caudate nucleus during the 2-year interval

For longitudinal analyses, the volumetric growth rate in caudate nucleus volume was calculated for each participant using the following equation: (Time 2 Volume − Time 1 Volume)/Time 1 Volume. Two-tailed, independent, two-sample t-tests were performed to test group differences in caudate nucleus volumetric growth rate. The ANCOVA was performed with the interval between scans and the growth rate for ICV as covariates.

Further, mixed models estimated group differences in caudate nucleus growth. Separate models were computed for left caudate nucleus volume and right caudate nucleus volume. Diagnostic group (ASD vs. DD) was a fixed-effects factor and age was a time-varying covariate in each model. A significant age effect specified caudate nucleus volume growth with increasing age. A significant diagnostic group effect indicated differences in caudate nucleus volume between individuals with ASD and DD, irrespective of age.

2.5.4. Correlation between development of caudate nucleus and RRBs

Correlations between the development of caudate nucleus volume (Time 2 Volume − Time 1 Volume) and RRBs (Time 2 score − Time 1 score) were calculated from the ADI-R using Pearson correlations for the ASD group with or without growth of ICV.

3. Results

No significant differences were seen between the two groups in terms of gender, age, DQ and IQ. Compared with the DD group, the ASD group demonstrated significantly higher RRBs scores on the ADI-R: Ritualistic-Repetitive Behavior including total scores, higher order (C1, C2) scores and lower order (C3, C4) scores (see Table 1).

3.1. Cross-sectional analyses of caudate nucleus at Time 1 and Time 2

Caudate nucleus volume at Time 1 and Time 2 and ANCOVA results are shown in Table 2. The volumes of left and right caudate nucleus were significantly larger in the ASD group compared with the DD group at both time points, even after adjusting for ICV that showed a significant effect of diagnosis on caudate nucleus for subjects with ASD. Further, the magnitude of differences in caudate nucleus was greater at Time 2. At Time 1, the differences in volume of the left and right caudate nucleus between the ASD and DD groups were approximately 7.1% and 8.0% respectively, which increased to approximately 10.3% and 12.1% at Time 2.

Table 2.

Caudate nucleus volume at Time 1 and Time 2 in ASD and DD subjects.

| ASD | DD | Difference |

t-Test |

ANCOVAa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M ± SD) cm3 | (M ± SD) cm3 | t | p | F | p | ||

| Time 1 | |||||||

| Left caudate | 3.24 ± 0.39 | 3.01 ± 0.39 | 7.1% | 2.041 | 0.046* | 5.564 | 0.002** |

| Right caudate | 3.38 ± 0.36 | 3.11 ± 0.37 | 8.0% | 2.492 | 0.016* | 7.184 | <0.001*** |

| Time 2 | |||||||

| Left caudate | 3.77 ± 0.49 | 3.38 ± 0.41 | 10.3% | 2.894 | 0.006** | 16.098 | <0.001*** |

| Right caudate | 3.95 ± 0.41 | 3.47 ± 0.46 | 12.1% | 3.904 | <0.001*** | 18.874 | <0.001*** |

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

Using intracranial volume as covariate.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

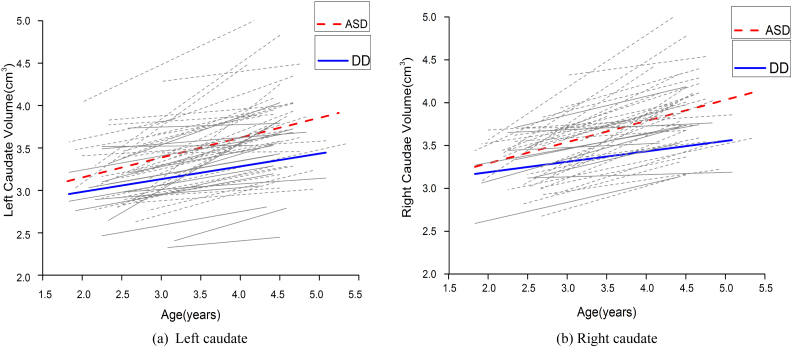

3.2. Group differences in development of caudate nucleus during the 2-year interval

Caudate volume growth rate and ANCOVA results are shown in Table 3. Left and right caudate nucleus volume increased 16.8% and 17.5%, respectively, with time in participants with ASD. The DD group showed a 12.8% and11.4% increase in left and right caudate nucleus volume, respectively, during the 2-year interval. The growth rate of the right caudate nucleus (t = 2.109, p = 0.040) was significantly increased in children with ASD compared with the DD group. Although the growth rate of the left caudate nucleus was larger in children with ASD than in the DD group, it was not statistically significant. Combining the growth rate of ICV or the interval between the two scans resulted in a significant effect of diagnosis on the growth rate of the right caudate nucleus. Fig. 2 presents individual and group-averaged growth trajectories of caudate nucleus structures during the 2-year interval between scans separately for participant groups.

Table 3.

Caudate volume growth rate: ASD vs. DD.

| Volume growth rate |

t-Test |

ANCOVAa |

ANCOVAb |

ANCOVAc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | DD | t | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Left caudate | 16.8 ± 11.7% | 12.8 ± 9.9% | 1.235 | 0.222 | 1.724 | 0.095 | 1.618 | 0.219 | 1.737 | 0.194 |

| Right caudate | 17.5 ± 10.6% | 11.4 ± 8.3% | 2.109 | 0.040* | 4.878 | 0.032* | 4.813 | 0.033* | 5.001 | 0.030* |

The interval between two scans was included as covariate.

The growth rate for ICV was included as covariates.

The interval between two scans and the growth rate for ICV were included as covariates.

p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of caudate nucleus growth in participants with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (red and gray dotted lines) and developmentally delayed (DD) subjects (blue and gray solid lines). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Mixed models show that irrespective of diagnosis, significant volume increases with age were observed for caudate nucleus including the left caudate nucleus (F = 2.722, p < 0.001) and right caudate nucleus (F = 2.420, p < 0.001). Patients with ASD had significantly higher left (F = 15.244, p = 0.002) and right (F = 17.833, p < 0.001) caudate nucleus volume across all ages relative to DD. There was no significant interaction effect for caudate nucleus volume.

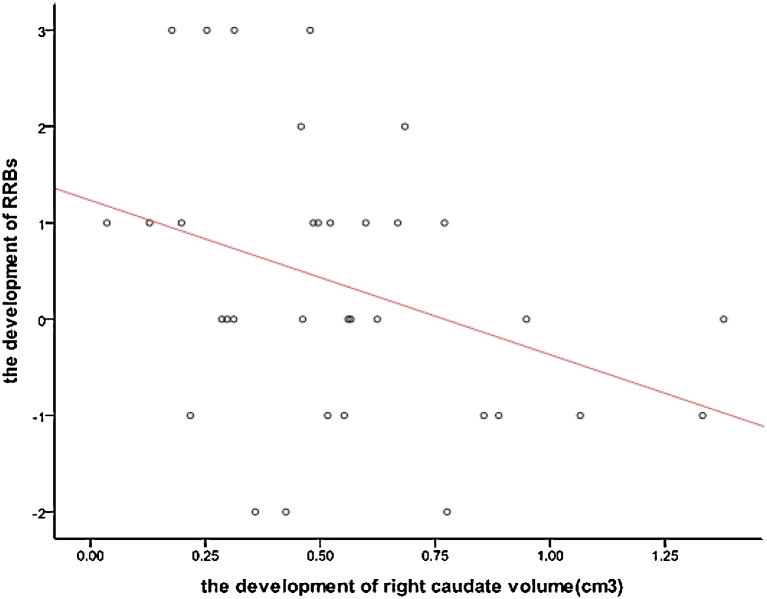

3.3. Correlation between development of caudate nucleus and RRBs

Pearson correlations were used to analyze the association between growth of RRBs measures with caudate nucleus volume in children with ASD. Significant negative correlations were found between the growth of ADI-R: Ritualistic-Repetitive Behavior in higher order RRBs scores (C1, C2) and right caudate nucleus volume (p = 0.040, r = −0.354) (see Fig. 3). After correcting for ICV growth, the relationship remained significant. No significant relationships were found between the growth of lower order (C3, C4) RRBs scores and growth in left or right caudate nucleus volume (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between the development of right caudate nucleus volume and higher order RRBs.

Table 4.

Correlation between the development of caudate nucleus volume and RRBs in ASD.

| Higher order RRBs |

Lower order RRBs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| Left caudate | −0.323 | 0.062 | −0.018 | 0.921 |

| Right caudate | −0.354 | 0.040* | 0.036 | 0.842 |

| Left caudatea | −0.326 | 0.064 | 0.036 | 0.841 |

| Right caudatea | −0.356 | 0.043* | 0.031 | 0.865 |

Using the growth of intracranial volume as covariate.

p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the developmental course of caudate nucleus volume in 2–3-year-old children with ASD. Our results indicate that the ADI-R: Ritualistic-Repetitive Behavior scores can be used to distinguish children with ASD from those with DD even at this young age. Two previous studies, both using the ADI-R, have shown significantly elevated RRBs scores in ASD children as young as 2 years (Richler et al., 2010) or 3–4 years (Estes et al., 2011) compared with DD children. We observed larger caudate nucleus volume in our ASD participants compared with age-matched DD participants at both time points. This finding is consistent with cross-sectional results reported by recent studies (Langen et al., 2007, Estes et al., 2011). The magnitude of caudate nucleus enlargement was larger at Time 2 suggesting that the pathological enlargement of caudate nucleus in ASD begins before age 3 and continues to increase for the next 2 years relative to the DD group.

Our longitudinal data suggest an increased caudate nucleus volume in the ASD and DD groups, including 2–3-year-old and 4–5-year-old children. In the ASD group, we found a 16.8% increase in left caudate volume over a 2-year interval compared with 12.8% and 17.5% increase in right caudate volume. The increase was only 11.4% for the DD group. Thus, the magnitude of caudate nucleus volume depends closely on the age of the sample, with older samples showing increasing magnitude of enlargement. In general, these findings suggest an abnormal acceleration in growth rate of the caudate nucleus during the 2 years consistent with the published longitudinal analysis of striatum growth in autism. Langen et al. (2014) found that the growth rate of striatal structures primarily involving caudate nucleus in their autism group was increased relative to typically developing control group between an average age of 9.9 years and 12.3 years. The annual growth rate in caudate nucleus volume was doubled. These results were supported by a study of a larger group of autistic individuals and typical controls with an age ranging between 10 and 15 years (Lange et al., 2015). The growth patterns may suggest an increasing tendency of development with ASD differing from the growth pattern seen in typically developing or pre-school DD children.

Neuroimaging results relevant to RRBs have largely been generated using subjects with ASD who are significantly older than the study participants. In the first of these publications, the caudate nucleus was reported to be enlarged in adults and young adolescents with high-functioning autism compared with typical matched controls (Sears et al., 1999). Additionally, caudate nucleus volume was negatively associated with three ADI items: compulsions and rituals, difficulties with minor change, and complex motor mannerisms. This was the first use of manual tracing of the basal ganglia to investigate the relationship between basal ganglia and RRBs in ASD. These results were supported by a study of a smaller group of autistic individuals and typical controls (Hollander et al., 2005) and a voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to detect regional gray matter volumetric changes in autism associated with RRBs (Rojas et al., 2006). However, correlations between repetitive behavior and caudate nucleus volume were not always significant. No significant correlations with ADI-R scores for higher-order or lower-order repetitive behavior and any striatal structures were found (Langen et al., 2007). In a later study, using a larger sample size, this group reported a negative correlation between caudate nucleus volume and insistence on sameness symptom cluster (Langen et al., 2009).

Few prior studies have addressed the relationship between caudate nucleus volume and RRBs in pre-school children with ASD. An exception is a recent study, which examined RRBs and its relationship to morphometric measures of the basal ganglia in 3–4-year-old children with ASD most of whom were lower functioning (Estes et al., 2011). The ASD group continued to demonstrate larger basal ganglia nuclei relative to the DD group even after cerebral volume adjustment, although this did not include left striatum, left putamen, or right putamen. No significant relationships were found between ADI, ADOS or ABC repetitive behavior scores and caudate nucleus volume, although ADOS scores were negatively correlated with volumetric measurements of other basal ganglia. These investigators suggest that newer imaging analytic methods and use of repetitive behavior scales that distinguish ‘higher order’ from ‘lower order’ RRBs (Turner, 1999) might uncover group differences. We found abnormal changes in right caudate nucleus volume and negative correlations with RRBs volume after distinguishing different components of RRBs in pre-school children with ASD. This finding is inconsistent with a longitudinal study that reported faster caudate and putamen growth was positively associated with increased severity in repetitive behavior (insistence on sameness) in school children with ASD (Langen et al., 2014). These inconsistencies underscore the need for studies with a larger sample size and increased length of follow-up.

A number of studies have confirmed that cortico-striatal-cortical loops play an important role in repetitive behavior (Remijnse et al., 2006, Turner et al., 2006, Sowell et al., 2008). Our study provides evidence that morphologic alterations of the caudate nucleus within cortico-striatal-cortical circuits contribute to the development of higher order RRBs behaviors for the period ranging from 2 to 5 years. Higher order RRBs in ASD may be associated with abnormal functional relationships between the caudate and other brain areas within the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuitry. Underlying mechanisms include an imbalance in direct and indirect pathways of the corticostriatal feedback loops (Bechard and Lewis, 2012, Westenberg et al., 2007). Future studies will need to include similar approaches to measure other brain regions exhibiting these pathways and cortical-basal ganglia circuitry in general.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study was confined to caudate nucleus excluding other parts of striatum. Caudate nucleus volume alone likely does not represent a comprehensive association with RRBs. Other studies have suggested that abnormalities in putamen and globus pallidus may be correlated with RRBs (Hollander et al., 2005), although the results still need confirmation. Second, we selected DD rather than typically developing children, which may limit our findings. The sample size is quite modest for a structural MRI study. Third, the ADI-R limits our understanding of the different levels of RRBs measures. Therefore, longitudinal imaging studies are warranted to determine the relationship between developmental alterations in basal ganglia and RRBs, comparing ASD and typically developing children as well as children with other developmental delays, with larger sample sizes.

5. Conclusion

Our findings reveal abnormally increased caudate nucleus volume in 2–3-year and 4–5-year-old children with ASD compared with DD group. The difference in caudate nucleus volume was increased in 4–5-year-old children. Our longitudinal data suggest that the caudate nucleus volume continues to accelerate with age. However, the trajectories of abnormal growth for caudate nucleus differ between ASD and DD within a 2-year interval. The development of caudate nucleus volume in ASD was larger than in DD group and significantly negatively correlated with the higher order (C1, C2) repetitive behavior scores whether or not adjusted for intracranial volume (ICV). These findings suggest the role of different pathophysiological processes in the development of caudate nucleus and underscore the importance of caudate nucleus in the pathophysiology of RRBs in 2–5-year-old children with ASD.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that there are no known conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participants including patients and their families for their support. This work was supported by The Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2012CB517900), Major projects of National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 14ZDB161), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91132705) and The Key Program of Medical Development of Nanjing (No. ZKX10023).

References

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bechard A., Lewis M.H. Modeling restricted repetitive behavior in animals. Autism – Open Access. 2012;S1:006. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M.H., Leckman J.F., Zhu H.T., Peterson B.S. Caudate volumes in childhood predict symptom severity in adults with Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2005;65:1253–1258. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180957.98702.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P., Liénard P. Why ritualized behavior? Precaution systems and action parsing in developmental, pathological and cultural rituals. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2006;29:595–613. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x06009332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A., Shaw D.W., Sparks B.F., Friedman S., Giedd J.N., Dawso G., Bryan M., Dager S.R. Basal ganglia morphometry and repetitive behavior in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2011;4:212–220. doi: 10.1002/aur.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.W., Leckman J.F., Carter A., Reznick J.S., Henshaw D., King R.A., Pauls D. Ritual, habit, and perfectionism: the prevalence and development of compulsive-like behavior in normal young children. Child Dev. 1997;68:58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Salat D.H., van der Kouwe A.J., Makris N., Ségonne F., Quinn B.T., Dale A.M. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S69–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Salat D.H., Busa E., Albert M., Dieterich M., Haselgrove C., van der Kouwe A., Killiany R., Kennedy D., Klaveness S., Montillo A., Makris N., Rosen B., Dale A.M. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen K.A., Cutting L.E., Kates W.R., Mostofsky S.H., Singeret H.S., Cooper K.L., Lanham D.C., Denckla M.B., Kaufmann W.E. Disproportionate increases of white matter in right frontal lobe in Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2002;58:85–89. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E., Anagnostou E., Chaplin W., Licalzi E., Wasserman S., Esposito K., Haznedar M.M., Soorya L., Buchsbaum M. Striatal volume on magnetic resonance imaging and repetitive behaviors in autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde T.M., Stacey M.E., Coppola R., Handel S.F., Rickler K.C., Weinberger D.R. Cerebral morphometric abnormalities in Tourette's syndrome: a quantitative MRI study of monozygotic twins. Neurology. 1995;45:1176–1182. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.H., Lord C. Restricted and repetitive behaviors in toddlers and preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule ADOS. Autism Res. 2010;3:162–173. doi: 10.1002/aur.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen M., Durston S., Kas M.J., van Engeland H., Staal W.G. The neurobiology of repetitive behavior: …and men. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011;35:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen M., Durston S., Staal W.G., Palmen S.J., van Engeland H. Caudate nucleus is enlarged in high-functioning medication-naive subjects with autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen M., Schnack H.G., van Engeland H., Nederveen H., Bos D., Lahuis B.E., Durston S. Changes in the developmental trajectories of striatum in autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen M., Bos D., Noordermeer S.D.S., van Engeland H., Nederveen H., Durston S. Changes in the development of striatum are involved in repetitive behavior in autism. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;76:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange N., Travers B.G., Bigler E.D., Prigge M.B., Froehlich A.L., Nielsen J.A., Cariello A.N., Zielinski B.A., Anderson J.S., Fletcher P.T., Alexander A.A., Lainhart J.E. Longitudinal volumetric brain changes in autism spectrum disorder ages 6–35 years. Autism Res. 2015;8:82–93. doi: 10.1002/aur.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C., Pickles A., McLennan J., Rutter M., Bregman J., Folstein S., Fombonne E., Leboyer M., Minshew N. Diagnosing autism: analyses of data from the Autism Diagnostic Interview. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1997;27:501–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1025873925661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey R.A., Petty C.M., Xu Y., Hayes J.P., Wagner R., Lewis D.V., Styner M., McCarthy G., LaBar K.S. A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing for quantifying hippocampal and amygdala volumes. Neuroimage. 2009;45:855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L., Etherbya M., Barber A. Repetitive and stereotyped movements in children with autism spectrum disorders late in the second year of life. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49:826–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoe H.R., Pell G.S., Abbott D.F., Jackson G.D. Hippocampal volume assessment in temporal lobe epilepsy: how good is automated segmentation? Epilepsia. 2009;50:2586–2592. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J., Mataix-Cols D. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive compulsive disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2009;195:393–402. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remijnse P.L., Nielen M.M., van Balkom A.J., Cath D.C., van Oppen P., Uylings H.B., Veltman D.J. Reduced orbitofrontal-striatal activity on a reversal learning task in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:1225–1236. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler J., Bishop S.L., Kleinke J.R., Lord C. Restricted and repetitive behaviors in young children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007;37:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler J., Huerta M., Bishop S.L., Lord C. Developmental trajectories of restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests in children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010;22:55–69. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas C., Peterson E., Winterrowd E., Reite M.L., Rogers S.J., Tregellas J.R. Regional gray matter volumetric changes in autism associated with social and repetitive behavior symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears L.L., Vest C., mohamed S., Bailey J., Ranson B.J., Piven J. An MRI study of the basal ganglia in autism. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. 1999;23:613–624. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(99)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segonne F., Pacheco J., Fischl B. Geometrically accurate topology-correction of cortical surfaces using nonseparating loops. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2007;26:518–529. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.887364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sled J.G., Zijdenbos A.P., Evans A.C. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S.H., Liu X.H., Yang Z.W., Wan G.B. The revising of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) in China. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 1993;1:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Institute of Pediatrics, Shanghai Xinhua Hospital . Shanghai Second Medical University; Shanghai: 1985. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell E.R., Kan E., Yoshii J., Thompson P.M., Toga A.W., Peterson B.S. Thinning of sensorimotor cortices in children with Tourette syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:637–639. doi: 10.1038/nn.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner K.C., Frost L., Linsenbardt D., Mcilroy J.R., Müller R.A. Atypically diffuse functional connectivity between caudate nuclei and cerebral cortex in autism. Behav. Brain Funct. 2006;2:34. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. Annotation: Repetitive behaviour in autism: a review of psychological research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1999;40:839–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L.R., Baranek G.T., Crais E.R., Steven R.J., Dykstra J., Perryman T. The first year inventory: retrospective parent responses to a questionnaire designed to identify one-year-olds at risk for autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007;37:49–61. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg H.G., Fineberg N.A., Denys D. Neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: serotonin and beyond. CNS Spectrosc. 2007;12:14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J.J., Hazlett H.C., Lightbody A.A., Reiss A.L., Piven J. Repetitive and self-injurious behaviors: associations with caudate volume in autism and Fragile X syndrome. J. Neurodev. Disorders. 2013:5–12. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman A.M., Abrams M.T., Giuliano J.D., Denckla M.B., Singer H.S. Subcortical volumes in girls with Tourette syndrome: support for a gender effect. Neurology. 2000;54:2224–2229. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]