Abstract

Background

Syphilis is re-emerging globally in general and HIV-infected populations, and repeated syphilis episodes may play a central role in syphilis transmission among core groups. Besides sexual behavioral factors, little is known about determinants of repeated syphilis episodes in HIV-infected individuals—including the potential impact of preceding syphilis episodes on subsequent syphilis risk.

Methods

In the prospective Swiss HIV cohort study, with routine syphilis testing since 2004, we analyzed HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM). Our primary outcome was first and repeated syphilis episodes. We used univariable and multivariable Andersen-Gill models to evaluate risk factors for first and repeated incident syphilis episodes.

Results

Within the 14-year observation period, we included 2513 HIV-infected MSM with an initially negative syphilis test. In the univariable and multivariable analysis, the number of prior syphilis episodes (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] per 1-episode increase, 1.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.31), having occasional sexual partners with or without condomless anal sex (aHR, 4.99; 95% CI, 4.08–6.11; and aHR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.10–3.07), and being currently on antiretroviral therapy (aHR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.21–2.16) were associated with incident syphilis.

Conclusions

In HIV-infected MSM, we observed no indication of decreased syphilis risk with repeated syphilis episodes. The extent of sexual risk behavior over time was the strongest risk factor for repeated syphilis episodes. The observed association of antiretroviral therapy with repeated syphilis episodes warrants further immunological and epidemiological investigation.

Keywords: HIV, immunity, repeated infection, risk factor, syphilis

Syphilis is re-emerging globally in general and HIV-infected populations as a major threat to individual and public health [1, 2]. Syphilis can be easily transmitted—often in asymptomatic stages—and may lead to independent syphilis outbreaks and sustained epidemics [1, 3]. Repeated syphilis episodes may play a central role in syphilis transmission dynamics among so-called core groups and high-volume repeaters [4, 5]; however, besides sexual behavioral aspects, little is known about risk factors for repeated syphilis episodes in HIV-infected individuals. It has been speculated that repeated syphilis episodes induce or boost a host immune reaction, which may ultimately decrease the likelihood of acquiring further syphilis episodes [1, 6]. In HIV-infected populations, however, epidemiological data on the potential impact of syphilis immunity and other factors such as antiretroviral therapy (ART) on the occurrence of repeated syphilis episodes are scarce [7]. This information may help to improve targeted syphilis prevention strategies for high-risk individuals and to guide current syphilis vaccine developments [8].

In HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM), we aimed to identify risk factors for incident syphilis and in particular for repeated syphilis episodes. We especially wanted to assess whether syphilis risk is associated with the number of preceding syphilis episodes.

METHODS

Swiss HIV Cohort Study

The Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS; www.shcs.ch) is a nationwide, prospective multicenter cohort study with semi-annual visits and blood collections—having enrolled >20 000 HIV-infected adults living in Switzerland since 1988 [9]. The SHCS is representative of the HIV epidemic in Switzerland and covers around 80% of new HIV infections in Switzerland since 1996 [9, 10]. The data collection is coded, and a written informed consent is required before study inclusion. In the SHCS, a standardized protocol is used for data collection. Sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical data are recorded at study entry, and several laboratory tests are routinely performed at registration [9]. Clinical, treatment, and laboratory information (eg, cluster of differentiation 4 [CD4] cell counts, HIV viral load) are recorded twice per year during follow-up visits. Behavioral information, such as condom use, type of partners (occasional and/or stable), alcohol use, and drug use in the last 6 months are self-reported during follow-up visits. Additional interim laboratory evaluations are recorded, if available.

The SHCS is registered on the Swiss National Science Foundation longitudinal platform (www.snf.ch/en/funding/programmes/longitudinal-studies) and is accepted by the responsible ethical committees in Switzerland (www.shcs.ch/206-ethic-committee-approval-and-informed-consent).

Participants

We restricted our study population within the SHCS to MSM, who account for >80% of syphilis episodes and are disproportionally burdened by syphilis [2, 11, 12]. We included MSM who had their first nontreponemal and treponemal syphilis test—with a negative result—performed after January 1, 2004, and who had at least 2 consecutive syphilis tests recorded in the database. The observation period ended on January 1, 2018.

Syphilis Testing and Outcome Measures

Syphilis testing in the SHCS includes both concurrent nontreponemal and treponemal assays [10, 11]: The nontreponemal assay comprises either the Veneral Diseases Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test; the treponemal assay involves a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination/Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPPA/TPHA), Liaison (CLIA), Architect (CMIA) test, or a IgG/IgM immunoassay (Elecsys Syphilis immunoassay). Since the restart of routine syphilis testing in the SHCS in 2004, MSM have been tested for syphilis annually, whereas other individuals are tested for syphilis once every 2 years. Additionally, individual syphilis tests at the discretion of treating physicians (eg, in case of suspicion of active infection) are recorded in the SHCS.

Our primary outcome was incident syphilis episodes (first and repeated episodes): We defined repeated syphilis episodes as a reported positive nontreponemal and treponemal test following a syphilis episode and subsequent ≥4-fold titer reduction or negativity in nontreponemal testing and a consecutive ≥4-fold titer increase with a titer value of at least 8 in nontreponemal testing. We defined first syphilis episodes as a reported positive nontreponemal and treponemal test in individuals with a negative first treponemal test within the study period. As we could not infer the infection date precisely and due to short time intervals between negative and positive syphilis tests, we used the date of positive nontreponemal and treponemal testing as the infection date estimate.

Data Analysis

To identify risk factors for incident syphilis episodes and to account for recurrent events, we fitted univariable and multivariable semiparametric Anderson-Gill models—an extension of the Cox proportional-hazard model, with static and time-updated covariables, as described previously [13].

Based on previous reports, an explorative analysis, and clinical opinion, we evaluated the following independent variables in the univariable and multivariable analysis [10]: year of birth, ethnicity (white or nonwhite), education level at baseline (with or without continuing education after high school), year of HIV infection, and year of syphilis testing; furthermore, we evaluated the following time-updated variables, which represent the individuals’ behavior in the previous 6 months; that is, alcohol use (with or without consumption of alcohol more than once a month), smoking status (with or without smoking of >1 cigarette per day), recreational use of intravenous and/or nonintravenous drugs (with or without use of recreational drugs), CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, ART (on or off ART), and sexual risk behavior (MSM with no occasional partners, MSM with occasional partners but no condomless anal intercourse, or MSM with occasional partners having condomless anal intercourse). In the final multivariable model, we excluded recreational drug use and alcohol consumption, as these variables were largely missing for the years 2004 to 2007; we included both variables in a sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition, we did not include HIV viral load in the final multivariable model due to potential collinearity with CD4 cell count and ART. Continuous variables were categorized in cases of evidence of departure from linearity. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis using a marginal-mean model (Supplementary Figure 2). We used complete-case analyses in all survival models.

In the final multivariable model, the proportional hazards assumption was met (Supplementary Figure 3), and respective deviance residuals to examine influential observations are reported in Supplementary Figure 4. We performed all analyses in R, version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We used the coxph function from the survival package in R to fit the Anderson-Gill models and the survminer package for model diagnostics.

RESULTS

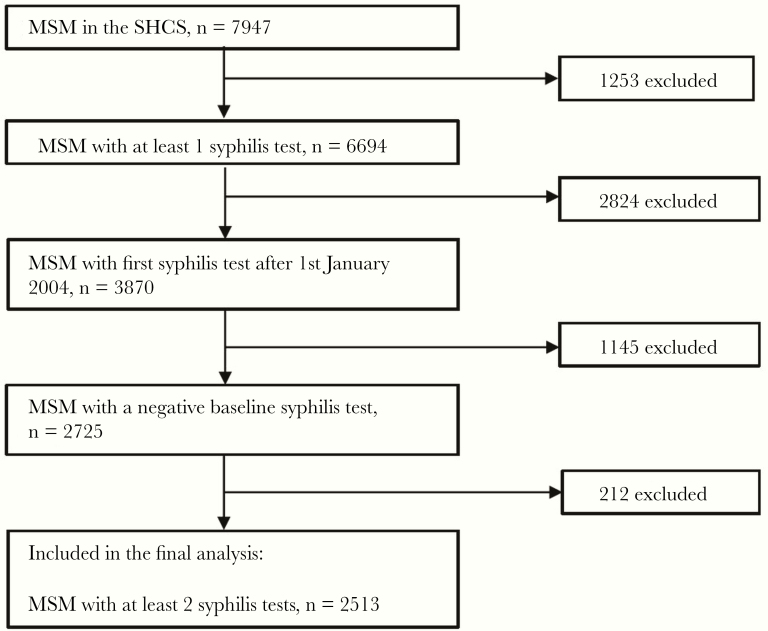

Within the 14-year observation period, 2513 HIV-infected MSM with an initially negative syphilis test formed the study population at risk (Figure 1). Of these 2513 individuals, 657 (26.1%) had at least 1 syphilis episode and 144 (5.7%) had at least 2 syphilis episodes; 42 (1.7%) MSM had 3 or more syphilis episodes (Table 1). Overall, MSM with an initially negative syphilis test were followed up for 15 002 person-years before they were lost to follow-up or had a first syphilis episode; similarly, MSM who had a first syphilis episode were followed up for a total of 2184 person-years.

Figure 1.

Study population. Abbreviations: MSM, men who have sex with men; SHCS, Swiss HIV Cohort Study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| No. Previous Syphilis Episodes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Overall | |

| MSM, No. (%)a | 2513 (100) | 657 (26.1) | 144 (5.7) | 42 (1.7) | 13 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.04) | 2513 |

| Total person-years of follow-up | 15 002.4 | 2184.1 | 359.7 | 80.6 | 17.7 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 17 653.1 |

| Incidence rate of syphilis per 1000 person-years (CI) | 44 | 66 | 117 | 161 | 226 | 202 | 538 | ─ | 49 |

| (41–47) | (56–78) | (86–158) | (94–278) | (85–602) | (28–1431) | (─) | (46–52) | ||

| Median syphilis testing rate per person-year (IQR) | 1.24 | 1.79 | 2.11 | 2.69 | 3.37 | 3.55 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 1.30 |

| (1.04–1.59) | (1.35–2.38) | (1.58–3.12) | (1.85–3.32) | (2.37–3.67) | (2.92–4.02) | (─) | (─) | (1.08–1.68) | |

| White ethnicity, No. (%)b | 2239 (89) | 583 (89) | 129 (90) | 38 (90) | 11 (85) | 4 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 2239 (89) |

| Median year of birth (IQR) | 1971 | 1972 | 1972 | 1972 | 1973 | 1966 | 1977 | 1977 | 1971 |

| (1964–1979) | (1965–1979) | (1965–1977) | (1965–1978) | (1968–1976) | (1959–1974) | (─) | (─) | (1964–1979) | |

| Median age at HIV infection (IQR) | 35 | 35 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 46 | 28 | 28 | 35 |

| (29–43) | (29–41) | (29–40) | (29–41) | (29–41) | (37–49) | (─) | (─) | (29–43) | |

| Continuing education after high school, No. (%)b | 1259 (50) | 334 (51) | 66 (46) | 23 (55) | 8 (62) | 3 (75) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1259 (50) |

| Median nadir CD4 (IQR) | 367 | 561 | 541 | 552 | 522 | 528 | 539 | 542 | 362 |

| (251–505) | (424–725) | (425–678) | (459–761) | (427–744) | (407–654) | (─) | (─) | (248–495) | |

| Ever used a recreational drug, No. (%)b,c | 673 (27) | 227 (35) | 58 (40) | 20 (48) | 4 (31) | 2 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 778 (31) |

| Alcohol consumption more than once a month for at least 6 mo during the entire follow-up, No. (%)b | 2178 (87) | 556 (85) | 132 (92) | 37 (88) | 12 (92) | 4 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 2254 (90) |

| Current smoker, No. (%)b | 1285 (51) | 301 (46) | 65 (45) | 19 (45) | 6 (46) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1321 (52) |

| Ever had an occasional partner, No. (%)b | 1885 (75) | 554 (84) | 126 (88) | 39 (93) | 12 (92) | 4 (100) | 1 | 1 (100) | 1941 (77) |

| Ever had condomless anal intercourse with an occasional partner, No. (%)b | 1028 (41) | 364 (55) | 99 (69) | 30 (71) | 8 (62) | 3 (75) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1168 (46) |

Abbreviations; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men.

aPercentage of total individuals at risk with no prior syphilis episodes.

bColumn percentages.

cRecreational drug use was defined as intravenous or nonintravenous use of drugs for recreational purposes.

Crude incidence rates of repeated syphilis episodes in MSM increased with the number of previous syphilis episodes—ranging from 66 episodes per 1000 person-years in MSM with 1 previous episode to 538 episodes per 1000 person-years in MSM with 6 previous episodes (Table 1). Overall, the median syphilis testing rate was 1.30 tests per person-year; we describe time trends in syphilis testing in Supplementary Figure 5. Compared with MSM with ≤1 prior syphilis episode, individuals with repeated syphilis episodes were younger and more frequently had an occasional partner and exposure to condomless anal intercourse with an occasional partner.

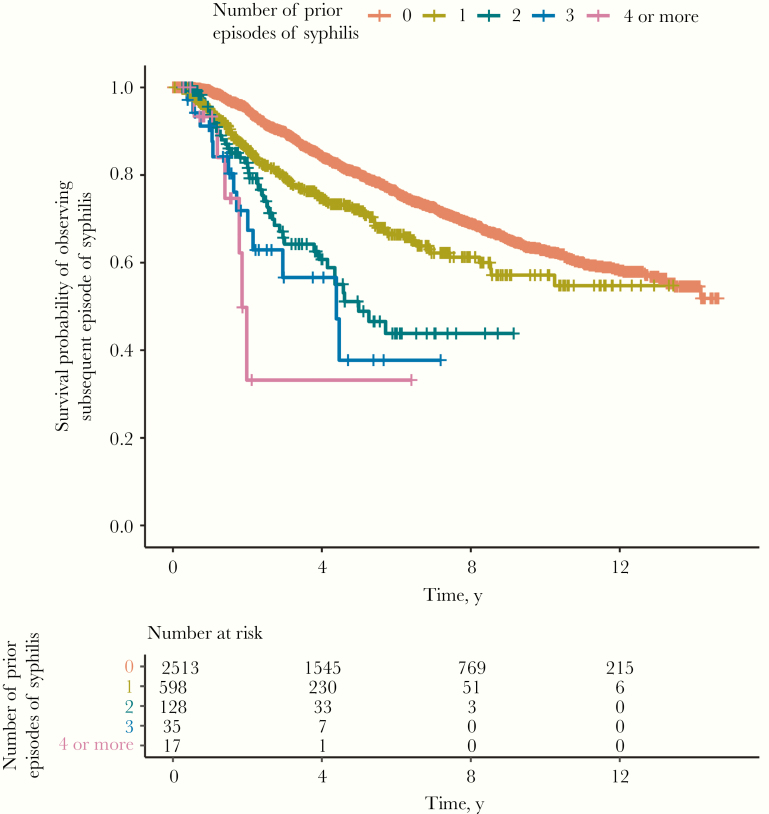

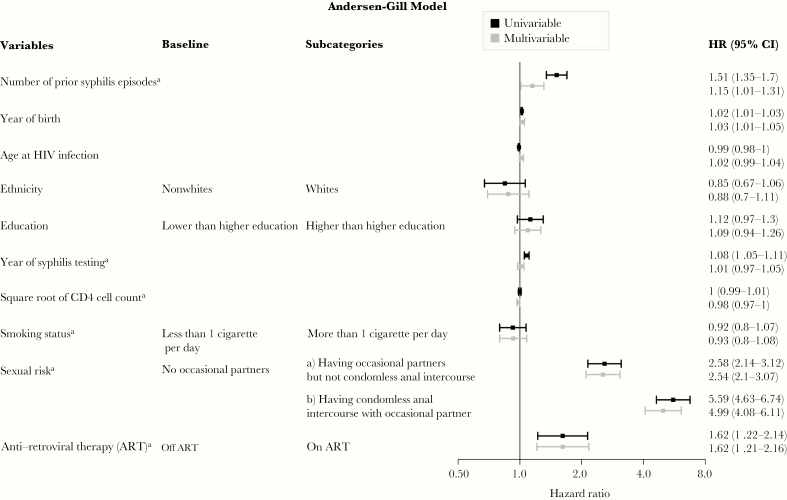

The cumulative probability of an incident syphilis episode increased with the number of previous syphilis episodes (Figure 2). In the univariable analysis, the number of prior syphilis episodes (crude hazard ratio [HR] per 1-episode increase, 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35–1.7), having occasional sexual partners with or without condomless anal sex (crude HR, 5.59; 95% CI, 4.63–6.74; and crude HR, 2.58; 95% CI, 2.14–3.12), and being currently on ART (crude HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.22–2.14) depicted the strongest association with subsequent incident syphilis episodes (Figure 3). In the multivariable analysis, the number of prior syphilis episodes (adjusted HR per 1-episode increase, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01–1.31), having occasional sexual partners with or without condomless anal sex (adjusted HR, 4.99; 95% CI, 4.08–6.11; and adjusted HR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.10–3.07), and being currently on ART (adjusted HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.21–2.16) remained associated with the occurrence of incident syphilis episodes. These findings were robust in the sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Repeated syphilis episodes in HIV-infected men who have sex with men; Kaplan-Meier estimates. Time is depicted since the previous syphilis episode, or since inclusion in the study in cases of absent previous syphilis episode.

Figure 3.

Risk factors for repeated syphilis episodes in HIV-infected men who have sex with men; Andersen-Gill model estimates. All effect estimates are expressed per 1-unit increase if no categories are stated. aTime-updated variables. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In the SHCS, we observed a high rate of syphilis among HIV-infected MSM with previous syphilis episodes, which may be explained largely by the sexual risk behavior and the high background risk of syphilis among MSM populations [2, 12]. We identified several risk factors for the occurrence of syphilis episodes in MSM, which are in line with previous studies investigating risk factors for first incident syphilis episodes among HIV-infected individuals and specifically among HIV-infected MSM [2, 14]. However, insufficient adjustment for changing sexual risk behavior might have led to residual confounding in some studies, and repeated syphilis episodes were often not modeled longitudinally [14, 15].

Previous studies have reported that repeated syphilis episodes may be less symptomatic and that the plasma cytokine and VDRL/RPR titer responses differ between individuals with initial and repeated syphilis episodes [16, 17]. Other studies found no difference in the clinical presentation of patients with initial and repeated syphilis episodes [15, 18, 19]. Interestingly, we observed no evidence of a decreased syphilis risk among HIV-infected MSM with repeated syphilis episodes; however, we cannot examine with the present study whether a partial attenuation, that is, less symptomatic repeated syphilis episodes, could be possible: Detailed clinical information on respective symptoms and signs was not collected in the SHCS database. In the present study, per 1-unit increase in the number of previous syphilis episodes, there was some evidence of a marginal positive association with the occurrence of subsequent syphilis episodes. The respective 95% CI of the adjusted HR ranged from 1.01 to 1.31. In the sensitivity analysis, the corresponding 95% CI of the adjusted effect estimate ranged from 0.99 to 1.34, with little (nonsignificant) evidence of an association between the number of syphilis episodes and the occurrence of subsequent syphilis episodes (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 2). However, these 2 point estimates are largely consistent, as the respective effect sizes for previous syphilis episodes are comparable. Nevertheless, a causal, positive association between the number of preceding syphilis episodes and the risk for consecutive syphilis episodes is unlikely but necessitates further immunological investigation. The small potential effect of previous syphilis episodes may be explained by residual and/or unmeasured confounding effects in high-risk individuals (eg, frequency of unprotected anal sex, number of occasional partners), which are not collected in the SHCS. Still, our finding is in accordance with a previous study performed among MSM in HIV care in Ontario, Canada, which reported a 3-fold increased rate of syphilis in individuals with a past syphilis diagnosis [20]. In line with this study, our cohort was restricted to HIV-infected MSM in order to account for potential confounding effects of seroadaptive or serosorting behavior (ie, choosing sex partners based on HIV status), which may facilitate syphilis transmission among MSM [21].

In our individual-level analysis, the observation period was too short to examine potential long-term cycles in syphilis incidence. It has been speculated that repeated syphilis episodes induce or boost a host immune reaction, which may ultimately decrease the propensity of acquiring further syphilis episodes and which may have an impact of syphilis transmission dynamics at the population level [4, 16]. In contrast to gonorrhea, Grassly et al. showed in an ecological modeling study that syphilis epidemics may represent a rare example of endogenous oscillation in syphilis incidence with an 8–11-year period that is predicted by the natural dynamics of syphilis infection and the associated partially protective immunity [6]. However, the hypothesis of endogenous cycling has been questioned [22].

In HIV-infected individuals, preliminary results from cohort studies, mathematical models, and reports have suggested that ART may be associated with increasing syphilis incidence due to changing sexual behavior and a multitude of effects of ART on the innate and adaptive immune system [7, 23–25]: The findings of the present cohort study, in which we modeled repeated syphilis episodes, are consistent with these investigations and reports; however, it is still uncertain whether the ART–syphilis relationship is causal, due to potential residual and unmeasured confounding (especially for sexual risk behavior such as the frequency of sexual intercourse with occasional partners [24, 25]) and the likely effect of HIV and ART on false-positive RPR serologies [26].

Our study has limitations. First, our syphilis episode definitions are based on results of nontreponemal and treponemal syphilis tests, as repeated syphilis episodes are often asymptomatic and as data on syphilis symptoms/signs and treatments have not been collected systematically in the SHCS database. Second, some individuals may not have been counted as having a repeated syphilis episode (ie, false negatives) due to a serofast state (ie, nontreponemal titers neither increase nor decrease 4-fold) after treatment of a prior syphilis episode [27]. This may have led to an underestimation of the true incidence of repeated syphilis episodes and may have negatively confounded the association between previous syphilis episodes and subsequent incident syphilis infections; thus, the observed positive association between previous syphilis and subsequent syphilis episodes may be stronger. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual and unmeasured confounding; for instance, the frequency of sexual intercourse and the number of occasional sexual partners are not collected in the SHCS database. Fourth, our study findings may not be generalizable to other populations with different risk profiles and immunological responses to syphilis [28].

However, our study has major strengths. First, our analyses were based on a large prospective cohort study with standardized, routine syphilis testing. Second, we analyzed risk factors for incident syphilis episodes in a well-defined population over a very long observation period—with a high retention proportion among participants. Third, our statistical models accounted for recurrent events and changes in risk behavior over time; this allowed us to longitudinally estimate the impact of repeated syphilis episodes on consecutive syphilis risk.

Conclusions

In HIV-infected MSM, we observed no indication of decreased syphilis risk with repeated syphilis episodes. The extent of sexual risk behavior over time was the strongest risk factor for recurrent syphilis episodes. The observed association of ART with repeated syphilis episodes may not be causal and warrants further epidemiological and immunological investigation.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Members of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS). Anagnostopoulos A, Battegay M, Bernasconi E, Böni J, Braun DL, Bucher HC, Calmy A, Cavassini M, Ciuffi A, Dollenmaier G, Egger M, Elzi L, Fehr J, Fellay J, Furrer H, Fux CA, Günthard HF (president of the SHCS), Haerry D (deputy of “Positive Council”), Hasse B, Hirsch HH, Hoffmann M, Hösli I, Huber M, Kahlert CR (chairman of the mother & child substudy), Kaiser L, Keiser O, Klimkait T, Kouyos RD, Kovari H, Ledergerber B, Martinetti G, Martinez de Tejada B, Marzolini C, Metzner KJ, Müller N, Nicca D, Paioni P, Pantaleo G, Perreau M, Rauch A (chairman of the scientific board), Rudin C, Scherrer AU (head of data center), Schmid P, Speck R, Stöckle M (chairman of the clinical and laboratory committee), Tarr P, Trkola A, Vernazza P, Wandeler G, Weber R, Yerly S.

Financial support. This study has been financed within the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #177499), by SHCS project #843, and by the SHCS research foundation. The data were gathered by 5 Swiss university hospitals, 2 Cantonal hospitals, 15 affiliated hospitals, and 36 private physicians (listed in http://www.shcs.ch/180-health-care-providers).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS):

A Anagnostopoulos, M Battegay, E Bernasconi, J Böni, D L Braun, H C Bucher, A Calmy, M Cavassini, A Ciuffi, G Dollenmaier, M Egger, L Elzi, J Fehr, J Fellay, H Furrer, C A Fux, H F Günthard, D Haerry, B Hasse, H H Hirsch, M Hoffmann, I Hösli, M Huber, C R Kahlert, L Kaiser, O Keiser, T Klimkait, R D Kouyos, H Kovari, B Ledergerber, G Martinetti, B Martinez de Tejada, C Marzolini, K J Metzner, N Müller, D Nicca, P Paioni, G Pantaleo, M Perreau, A Rauch, C Rudin, A U Scherrer, P Schmid, R Speck, M Stöckle, P Tarr, A Trkola, P Vernazza, G Wandeler, R Weber, and S Yerly

References

- 1. Hook EWR. Syphilis. Lancet 2017; 389:1550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shilaih M, Marzel A, Braun DL, et al. ; and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study Factors associated with syphilis incidence in the HIV-infected in the era of highly active antiretrovirals. Medicine 2017; 96:e5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gesink D, Wang S, Norwood T, et al. Spatial epidemiology of the syphilis epidemic in Toronto, Canada. Sex Transm Dis 2014; 41:637–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenyon C, Lynen L, Florence E, et al. Syphilis reinfections pose problems for syphilis diagnosis in Antwerp, Belgium - 1992 to 2012. Euro Surveill 2014; 19:20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hsu KK, Molotnikov LE, Roosevelt KA, et al. Characteristics of cases with repeated sexually transmitted infections, Massachusetts, 2014–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grassly NC, Fraser C, Garnett GP. Host immunity and synchronized epidemics of syphilis across the United States. Nature 2005; 433:417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rekart ML, Ndifon W, Brunham RC, et al. A double-edged sword: does highly active antiretroviral therapy contribute to syphilis incidence by impairing immunity to Treponema pallidum? Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93:374–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lithgow KV, Cameron CE. Vaccine development for syphilis. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017; 16:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schoeni-Affolter F, Ledergerber B, Rickenbach M, et al. Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39:1179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shilaih M, Marzel A, Yang WL, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study Genotypic resistance tests sequences reveal the role of marginalized populations in HIV-1 transmission in Switzerland. Sci Rep 2016; 6:27580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thurnheer MC, Weber R, Toutous-Trellu L, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study Occurrence, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment of syphilis in the prospective observational Swiss HIV Cohort Study. AIDS 2010; 24:1907–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abara WE, Hess KL, Neblett Fanfair R, Bernstein KT, Paz-Bailey G. Syphilis trends among men who have sex with men in the United States and Western Europe: a systematic review of trend studies published between 2004 and 2015. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0159309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amorim LD, Cai J. Modelling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2015; 44:324–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008–2015. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0168642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katz KA, Lee MA, Gray T, Marcus JL, Pierce EF. Repeat syphilis among men who have sex with men—San Diego County, 2004–2009. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kenyon C, Osbak KK, Apers L. Repeat syphilis is more likely to be asymptomatic in HIV-infected individuals: a retrospective cohort analysis with important implications for screening. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Courjon J, Hubiche T, Dupin N, et al. Clinical aspects of syphilis reinfection in HIV-infected patients. Dermatology 2015; 230:302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brewer TH, Peterman TA, Newman DR, Schmitt K. Reinfections during the Florida syphilis epidemic, 2000–2008. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lang R, Read R, Krentz HB, et al. A retrospective study of the clinical features of new syphilis infections in an HIV-positive cohort in Alberta, Canada. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e021544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burchell AN, Allen VG, Gardner SL, et al. ; OHTN Cohort Study Team High incidence of diagnosis with syphilis co-infection among men who have sex with men in an HIV cohort in Ontario, Canada. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fujimoto K, Flash CA, Kuhns LM, et al. Social networks as drivers of syphilis and HIV infection among young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2018; 94:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Breban R, Supervie V, Okano JT, et al. Is there any evidence that syphilis epidemics cycle? Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8:577–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tuddenham S, Shah M, Ghanem KG. Syphilis and HIV: is HAART at the heart of this epidemic? Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93:311–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu QH, Xu JJ, Zou HC, et al. Risk factors associated with prevalent and incident syphilis among an HIV-infected cohort in Northeast China. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park WB, Jang HC, Kim SH, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of early syphilis in HIV-infected patients. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35:304–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oboho IK, Gebo KA, Moore RD, Ghanem KG. The impact of combined antiretroviral therapy on biologic false-positive rapid plasma reagin serologies in a longitudinal cohort of HIV-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seña AC, Wolff M, Martin DH, et al. Predictors of serological cure and Serofast State after treatment in HIV-negative persons with early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:1092–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hutchinson CM, Rompalo AM, Reichart CA, Hook EW 3rd. Characteristics of patients with syphilis attending Baltimore STD clinics. Multiple high-risk subgroups and interactions with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:511–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.