This qualitative study identifies sources of burnout and potential remedies after conducting focus group discussions and interviews among primary care practitioners at a large US academic medical center.

Key Points

Question

What are the contributors to high burnout and low professional fulfillment among primary care practitioners?

Findings

In this qualitative study of burnout involving 26 participants, frontline primary care practitioners expressed a sense of professional dissonance, or discomfort from working in a system that seems to hold values counter to their own as clinicians. Factors they mentioned that may be more specific to primary care practitioners included an authority-responsibility mismatch and feeling undervalued.

Meaning

In this study, primary care practitioners identified many contributors to burnout and low professional fulfillment but also suggested possible solutions in which institutions may want to invest to resolve dissonance, reduce burnout rates, and improve professional fulfillment in primary care.

Abstract

Importance

Burnout negatively affects physician health, productivity, and patient care. Its prevalence is high among physicians, especially those in primary care, yet few qualitative studies of burnout have been performed that engage frontline primary care practitioners (PCPs) for their perspectives.

Objective

To identify factors contributing to burnout and low professional fulfillment, as well as potential solutions, by eliciting the views of PCPs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

For this qualitative study, focus group discussions and interviews were conducted between February 1 and April 30, 2018, among 26 PCPs (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) at a US academic medical center with a network of 15 primary care clinics. Participants were asked about factors contributing to burnout and barriers to professional fulfillment as well as potential solutions related to workplace culture and efficiency, work-life balance, and resilience.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Perceptions of the factors contributing to burnout and low professional fulfillment as well as potential solutions.

Results

A total of 26 PCPs (21 physicians, 3 nurse practitioners, and 2 physician assistants; 21 [81%] women) from 10 primary care clinics participated. They had a mean (SD) of 19.4 (9.5) years of clinical experience. Six common themes emerged from PCPs’ experiences with burnout: 3 external contributing factors and 3 internal manifestations. Participants described their workloads as excessively heavy, increasingly involving less “doctor” work and more “office” work, and reflecting unreasonable expectations. They felt demoralized by work conditions, undervalued by local institutions and the health care system, and conflicted in their daily work. Participants conveyed a sense of professional dissonance, or discomfort from working in a system that seems to hold values counter to their values as clinicians. They suggested potential solutions clustered around 8 themes: managing the workload, caring for PCPs as multidimensional human beings, disconnecting from work, recalibrating expectations and reimbursement levels, promoting PCPs’ voice, supporting professionalism, fostering community, and advocating reforms beyond the institution.

Conclusions and Relevance

In sharing their perspectives on factors contributing to burnout, frontline PCPs interviewed during this study described dissonance between their professional values and the realities of primary care practice, an authority-responsibility mismatch, and a sense of undervaluation. Practitioners also identified possible solutions institutions might consider investing in to resolve professional dissonance, reduce burnout rates, and improve professional fulfillment.

Introduction

Burnout—commonly defined as a work-related syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced accomplishment1,2—negatively affects physicians’ health and productivity as well as patient care.3,4,5 Several studies have estimated burnout rates at 50% or greater among US physicians, with even higher rates estimated among primary care physicians.6,7,8,9 Left unaddressed, high burnout rates in medicine threaten the long-term health of the profession.

In attempting to identify underlying contributors to burnout, cross-sectional studies of physicians have found independent relationships between burnout and individual factors, such as sex and age, as well as work-related factors, such as hours and clerical burden.3 Although potentially pertinent factors such as career stage and specialty have been examined in previous studies, primary care–specific factors and solutions are less well understood. In contrast to survey-based studies and editorials, there are a limited number of qualitative studies of burnout that focus exclusively on US primary care and engage frontline clinicians to provide their varied perspectives; most qualitative studies have been based in other countries or included specialist physicians.10,11,12

In this study, we conducted focus group discussions among primary care practitioners (PCPs) to elicit their views about the factors contributing to burnout and low professional fulfillment as well as their recommendations for potential solutions. Our goal was to achieve a greater understanding of burnout from the perspective of frontline PCPs that could help inform future individual, organizational, and system-level interventions and investments.

Methods

Setting, Participants, and Study Design

In this qualitative study, we conducted focus groups and interviews at Brigham Health, a large multispecialty academic medical center with 15 primary care internal medicine clinics located in urban and suburban areas of eastern Massachusetts. Potential participants were identified from a master listserv and recruited via email invitation sent to the division’s 189 PCPs (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants).

Participants provided written informed consent and attended 1-hour sessions in person or by web conference. Lunch was offered, but attendees received no other compensation for their participation. There were 4 focus group discussions, each including from 3 to 11 participants, and 2 in-person interview sessions. All focus group discussions and interviews were conducted between February 1 and April 30, 2018. This project was undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at Brigham Health and, as such, was not formally supervised by the institutional review board per their policies.

Interview Guide

The interview guide was developed using information from the literature on burnout as well as a conceptual model and survey material from the Stanford University WellMD Center.13 The guide (eAppendix in the Supplement) included open-ended questions on causes of burnout, barriers to professional fulfillment, and potential solutions. For consistency with prior work on physician well-being, we distinguished between burnout and professional fulfillment, which are negative and positive potential sequelae, respectively, of work-related stress.14,15,16 There were additional questions about workplace culture and efficiency, work-life balance, and resilience. Because our institution separately collected and has been responding to feedback on the usability of the electronic health record (EHR) system, we did not focus on EHR-specific issues.

Qualitative Analysis

A practicing primary care physician (E.P. or K.M.S.) moderated all sessions, following a semistructured format. There was at least 1 observer in each session. We offered focus groups and interviews until adequate saturation was reached for thematic content analysis. All sessions were recorded, and the recordings were deidentified and transcribed.

Two of us (S.D.A. and K.M.S.), both primary care physicians, reviewed the transcripts, independently coded the data, and produced a list of themes and subthemes following a grounded theory approach.17 Researchers used Word and Excel, version 16.0 (Microsoft Corp), for managing the data. The preliminary themes were reviewed by the entire research team, which included 1 qualitative research expert (R.R.) and 3 primary care physicians (S.D.A., E.P., and K.M.S.). The 2 coders then iteratively compared and clarified themes, reconciled any discrepancies with a third investigator (R.R.), and produced a final set of themes.

Results

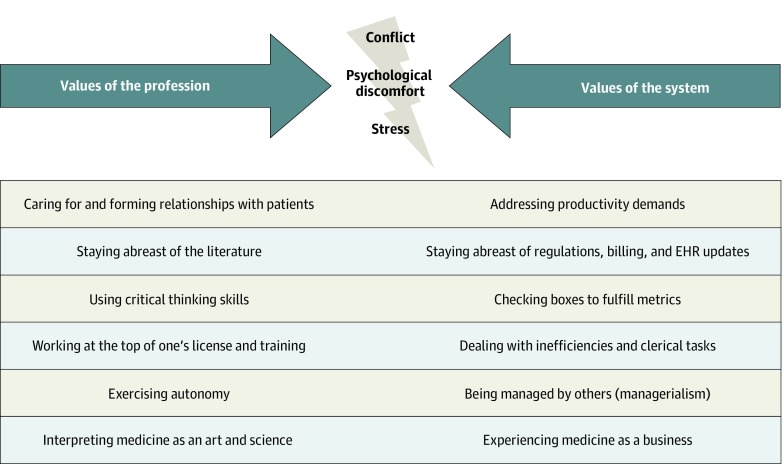

A total of 26 PCPs (21 physicians, 3 nurse practitioners, and 2 physician assistants; 21 [81%] women) from 10 affiliated practices participated in at least 1 of the 4 focus group discussions or at least 1 of 2 interview sessions (Table). The participants had a mean (SD) of 19.4 (9.5) years of clinical experience. The composition of the focus groups was similar to that of the overall primary care division with regard to sex, clinical time, and experience. All participants conveyed some degree of burnout or lack of professional fulfillment, and 6 qualitative themes emerged—3 external factors and 3 internal manifestations. The PCPs expressed a general sense of professional dissonance between their values as clinicians and the values of the system in which they were working (Figure). Participants then discussed potential solutions for addressing burnout (Box).

Table. Characteristics of Primary Care Practitioners in the Study and the Division Population.

| Characteristics | Participants in Focus Groups and Interviews (n = 26) | Entire Primary Care Division (N = 189) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 5 (19) | 61 (32) |

| Female | 21 (81) | 128 (68) |

| Experience, mean (SD), y | 19.4 (9.5) | 19.5 (10.8) |

| Time at current practice, mean (SD), y | 8.8 (6.5) | 8.9 (7.5) |

| Clinical time, in full-time equivalents, mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | 21 (81) | 160 (85) |

| Practice setting, No. (%) | ||

| Hospital | 2 (8) | 70 (37) |

| Community clinic | 24 (92) | 119 (63) |

Figure. Professional Dissonance.

Tension between professional values (left) and system values (right) can produce psychological discomfort, conflict, and stress. EHR indicates electronic health record.

Box. Solutions to Burnout.

-

Help PCPs manage the workload.

-

(Factors addressed: quantity of work, content of the work, feelings of demoralization and internal conflict)

Hire additional support staff

Off-load office tasks from PCPs

Empower support staff and promote retention

Examine PCP workflows and address pain points, including the flow of incoming requests via the EHR

-

-

Care for PCPs as multidimensional human beings

-

(Factors addressed: demoralization, feelings of being undervalued or conflicted)

Institute family-friendly policies (eg, flexible work schedules, support childcare and eldercare)

Promote employee safety in the workplace

-

-

Encourage off-duty PCPs to disconnect from work

-

(Factors addressed: quantity of work, feelings of demoralization and internal conflict)

Provide telephone coverage (eg, answering service) after hours, on weekends, and during vacations and other absences

Track “work-after-work” hours (eg, after-hours work on the EHR)

-

-

Recalibrate expectations and reimbursement

-

(Factors addressed: responsibility-authority mismatch, feeling of being undervalued)

Compensate PCPs for work done apart from office visits

Reevaluate targets: the number of clinical sessions, patients per session, and/or relative value units that constitute a full-time equivalent

Explicitly define expectations of PCPs

-

-

Promote the PCPs’ voice

-

(Factors addressed: responsibility-authority mismatch)

Open lines of PCP communication with leadership and specialty departments

Manage frontline PCPs with a bottom-up approach

-

-

Support professionalism

-

(Factors addressed: content of the work, feelings of demoralization and internal conflict)

Align the system with professional values

Promote opportunities for learning and staying abreast of medical literature

Eliminate or redesign pay-for-performance initiatives

Protect PCPs’ relationships and time with patients

-

-

Foster community

-

(Factor addressed: demoralization)

Provide time, funds, and opportunities to get to know colleagues

-

-

Advocate reforms beyond the institution

-

(Factors addressed: content of the work, demoralization, feeling of being undervalued)

Reduce documentation requirements

Align EHRs with the needs of clinicians

Increase reimbursements from payers for primary care work

-

External Contributors to Burnout and Low Professional Fulfillment

Quantity of Work

All participants mentioned the sheer quantity of work. One PCP commented, “Every day, I start with a pile of work that is insurmountable.” The workload was variously described as “unrealistic,” “overwhelming,” and “undoable.” A few participants described an increasing workload (“at every meeting, we are asked something new to do”), and several participants noted that work “bleeds into the time you should be enjoying yourself.”

Content of Work

All participants expressed dissatisfaction that their jobs seemed to involve less “doctor” work and increasingly more “office” work. Examples of office work included charting for billing or population health documentation purposes, fielding electronic messages and telephone calls, and processing paperwork. Participants highlighted 2 key aspects of office work that made it particularly dissatisfying. First, it was incongruous with their training and qualifications: “Increasingly what we do is manage a lot of data and numbers and processes, and we get further away from taking care of people and diagnosing diseases and the stuff I went to medical school for.” Second, the office work was unnecessarily complex or inefficient: “A simple task took me over an hour to do.” Several lamented the multiple “back-and-forths” needed to get anything done, whether dealing with staff, pharmacies, or insurance companies.

Responsibility-Authority Mismatch

Many participants described the scope of their responsibilities in caring for patients as ever enlarging while their authority over their work was decreasing. Feeling “dumped on” by the system, many mentioned that their specialist colleagues routinely left drug refills, prior authorizations, test results, and workups to the PCPs. Others described how patients who were unable to contact other departments would “turn to [the PCP] for their last chance to get things done.” Several brought up requests they had received from patients outside of office visits: “There’s an increasing need and emphasis around instantly responding to things,” a PCP commented; another said, “Some patients act like you are their instant message buddy.” Additional examples pointed to unrealistic expectations on the part of other clinical staff and the emergency department, who were reported often to default to the statement “That has to be done by the PCP.”

Several participants described a lack of “boundaries…in terms of what we own and what we don’t own.” One participant said, “We are a giant funnel, and we take everyone in”; another said, “Everyone else is defining us.” As one participant summarized the situation, “The pendulum has swung so far on patient satisfaction and patient expectation that no one has thought about the repercussions on [PCPs] and their ability to handle what is expected of them.” Despite high and growing levels of responsibility, participants felt that they lacked the resources to handle all those demands and/or the ability to push back: “There is no way to put limits or say no and really demand that we get treated better.”

Internal Manifestations

Demoralization

Participants described how external factors contributing to burnout also were manifested internally: “It’s demoralizing when you never have a sensation that your job is actually completed for the day.” Participants highlighted several aspects of practice that contributed to their feeling demoralized about work conditions. Specifically, many participants commented on how, increasingly, “the business part of our profession looks more important than the medical part.” As one participant said, “It just feels like it’s all about the money.…It sacrifices the morale of the people.” Furthermore, several participants felt that the lack of responsiveness to the needs of PCPs, such as the need for adequate EHR support, contributed to the suboptimal work conditions. A few participants also felt burdened by seemingly punitive rules, including time requirements for finishing notes, and by linkage between salaries and population health metrics. One remarked, “You are being punished for something that is completely out of your control.”

Undervaluation

Another common feeling was that of being undervalued by the local institution and the broader health care system. Many participants said their salaries did not accurately reflect their daily work: “I’m doing an awful lot more work that is not being compensated.” Some participants highlighted the distinction between cognitive and procedural work: “Our tools are our brains; but because that is so much more nebulous than a procedure, it is not as respected or preserved.” Several participants noted, “The current way [the job] is funded and paid for is not in line with the values of taking care of patients.”

Participants noted at least 3 other factors that fueled the perception of being undervalued: lack of boundaries in terms of responsibilities, insufficient communication with leadership and specialists, and inadequate acknowledgment of the difficulties of primary care.

Internal Conflict

Many PCPs offered examples of recurring dilemmas that gave rise to internal conflict in their daily work: typing while in the examining room (to avoid drowning in notes later) vs giving patients their undivided attention; doing “what’s right for the patient” vs “having to bill or see X number of patients”; and wanting to take a lunch break or stay abreast of the medical literature but not having any time to do so. Others described conflict between their responsibilities at home and at work. Overall, participants said that in moments of conflict they relied on their sense of professionalism to preserve excellence in patient care, but they expressed concern for the future: “I think we are doing a good job, but that is being held up by people’s strong sense of professionalism.… My fear is that if that is all it rests upon, then it will all collapse at some point.”

Potential Solutions

Managing the Workload

Participants unanimously agreed that workload reduction was needed and could be achieved by off-loading work and eliminating inefficiencies. The EHR in-basket was identified as one important area for improvement, suggesting a need for specialized workflows to address the constant influx of messages, results, refills, and other requests. One participant described this wish: “Life would be wonderful if there was a full-time assistant who sat next to me, shared my patient panel with me, and helped with all the phone calls, emails, results, triage, and prescription refills.”

Participants had several recommendations to improve the state of current initiatives. First, hiring more support staff should not be viewed as a zero-sum game. (In the words of 1 participant, “Anything we use, like a scribe, we have to pay for ourselves by increasing the number of patients we see.”) Second, nursing and support staff should be trained to work independently, without requiring constant delegation of tasks, which was “actually not more help, but more work in a different way.” Third, a few participants who discussed setbacks caused by staff turnover recommended that staff retention be given higher priority.

Caring for PCPs as Multidimensional Human Beings

Several participants discussed a desire for leadership to foster a cultural shift within the institution that would lead to recognition of PCPs as multidimensional human beings. For example, they wanted flexible work schedules and family-friendly policies that would make it easier to balance family and work. One participant said, “This job does not seem to support any kind of ability to [take care of family members], such as [taking time off] to be at their doctors' appointments or running home for an emergency.”

Disconnecting From Work

Most participants stressed the need for initiatives allowing PCPs to disconnect from work after hours and during vacation and sick days. They described current coverage policies as inadequate because they burdened other PCPs and resulted in a buildup of work for the absentee. As one participant said, “We have to have a system where a person can go on vacation, forget work, and not worry about what’s going to happen [when they get back] on Monday.”

Recalibrating Expectations and Reimbursement

Many participants thought the expectations of a full-time equivalent PCP were in need of recalibration to more realistic and sustainable levels. As one participant put it, “The idea that a full-time job for primary care is 8 sessions is sort of insane.… Currently, the amount of work that requires is unrealistic if you don’t want to work 80 hours per week.” Many participants discussed a related theme, the reimbursement structure, saying that it should better reflect the changing nature of primary care: “The work [we] do outside of seeing a patient should be compensated.”

Promoting PCPs’ Voice

Most participants expressed a desire for improved communication with specialist colleagues and institutional leaders. They wanted to participate in deciding the boundaries of their jobs and to have avenues for conveying those boundaries to specialists, staff, and patients. Several voiced a wish for “greater accountability from other parts of the hospital or departments for what they do, so it doesn’t always funnel back to us.” Participants believed that leadership had an important role in promoting the PCPs’ voice by fostering bottom-up management in which frontline PCPs would actively participate in decisions affecting their salaries and daily work.

Supporting Professionalism

Many participants described how their high workloads crowded out activities they perceived as critical to their professional identity and high-quality patient care. For example, many PCPs spoke of staying abreast of the literature: “Anyone who is doing that is doing it at home, during their free time or before going to bed, and that’s not the time we should be doing things that are absolutely essential to our job.” Several participants noted that constant busyness precluded the ability to pursue other academic interests or focus on career development.

One participant, highlighting other aspects of professionalism, voiced a desire to be “allowed to judge what is important to [the patient]” rather than “checking boxes and making sure I’m ordering every test that is required even though it may not be clinically correct for the patient.” Another said, “To me, professional fulfillment is having good relationships with patients and coworkers. [We need to eliminate] those kinds of things that interfere with relationships.”

Fostering Community

Participants uniformly agreed that personal training in resilience was not something they needed, citing their belief that PCPs are already resilient people at baseline. Instead, they advocated for time and opportunities to interact with colleagues and staff: “I really love my coworkers.…I wish I had more time to spend with them.”

Advocating for Reforms Beyond the Institution

Participants thought that their institution, given its size and clout, could play a leading role in advocating for broader changes in the realm of primary care. Specific examples included reducing onerous regulations governing documentation, and increasing reimbursements from payers for primary care services.

Discussion

We identified 6 qualitative themes in the experiences reported by PCPs as contributing to burnout and low professional fulfillment. In general, PCPs expressed a sense of professional dissonance, or discomfort experienced while working in a system that seems to have values counter to theirs. Our study echoes the importance of factors identified in other studies, such as workload, efficiency, control, and work-life integration,18,19,20 but expands on prior work in several important ways.

First, we focused exclusively on PCPs, a group of medical professionals with a notably high prevalence of burnout,7,8,9 and found that they emphasized some factors that may be more specific to primary care, such as a responsibility-authority mismatch. The boundaries of primary care, which is commonly viewed as the safety net of the health care system, are becoming ever more blurred. Even as the scope of PCPs’ responsibilities has increased, their authority to accomplish the job has decreased. Furthermore, participants in our study thought that much of their work went unseen21 and uncompensated and therefore was undervalued.

Second, this study reinforced the importance of professional dissonance as a key aspect of physician burnout and low professional fulfillment.22,23,24,25,26 Each of the contributing factors we identified, as well as many identified in other studies, such as meaning in work,18 may be better understood within the framework of professional dissonance, which helps explain how those factors lead to burnout. Derived from the theory of cognitive dissonance developed by social psychologists Festinger27 and Aronson,28 professional dissonance is the psychological discomfort or stress that occurs when values embraced by a professional group conflict with the values intrinsic to the settings in which they work; more specifically, it occurs when conflict arises between professional values and the requirements of the job.29,30 The PCPs in our study described many examples of an uncomfortable tension between honoring the professional values and traditions that brought them to a career in medicine vs responding to the demands of the current health care system. Although further research is needed to understand how PCPs might consciously or subconsciously relieve the stress induced by professional dissonance, the presence of that dissonance may help explain why some physicians reduce their clinical hours or retire early.31,32,33,34 Opting out and exiting a position earlier than expected has been found in other fields when levels of dissonance have become unbearable.35

Third, participants in our study proposed many solutions to reduce burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Some of these interventions have been described previously,36,37,38,39,40,41 but PCPs emphasized solutions based on their particular relevance to primary care; for example, promoting PCPs’ voice and recalibrating expectations to address the responsibility-authority mismatch. These solutions require leadership and institutional support. After we conducted the PCP focus groups, our division responded to this quality improvement initiative by hiring additional registered nursing support and optimizing workflows, initiating efforts to move away from relative value unit–based to panel-based compensation, programming time into schedules for work tasks other than direct patient care, and increasing stipends for professional development. Experience at our institution shows that committed efforts to understand and address burnout can make a positive difference.42

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, the results may not be generalizable to other specialties, institutions, or types of practices. We purposely limited our analysis to PCPs in order to elucidate the most important factors for this group of medical professionals. Our study took place within a single urban academic medical center, and the results should be interpreted in this context. Nonetheless, our focus groups included PCPs from 10 different clinics, including urban and suburban community-based practices, and we believe many of the themes that emerged from our discussions will resonate with clinicians at other institutions. Second, our study was not designed to detect sex-related differences. It is possible that potential contributing factors and solutions may differ on the basis of PCPs’ sex.43 Third, we asked participants in our study to limit their discussion of the EHR, which was previously found to be associated with burnout and was already being addressed at our institution.19,44,45 This planned limitation encouraged a richer discussion of non–EHR-related contributing factors. Fourth, burnout and professional satisfaction, although they may overlap, are distinct issues, and the elimination of the former does not guarantee the achievement of the latter.14,15,16 In analyzing PCPs’ perceptions, we did not distinguish themes by whether they applied to high burnout or low professional satisfaction because there was substantial overlap. However, it is likely that some themes are more relevant to one vs the other.46 Fifth, the findings of this qualitative study are hypothesis generating, and we are unable to make causal claims.

Conclusions

In this qualitative study, frontline PCPs expressed a general sense of professional dissonance because the realities of their practice did not align with their professional values. Factors that may be specific to PCPs include an authority-responsibility mismatch and feeling undervalued. Participants identified many solutions in which institutions should consider investing. To reduce high burnout rates in primary care, the diverse perspectives of frontline PCPs should be elicited, and PCPs should be actively engaged in the development and implementation of solutions.

eAppendix. Interview Guide

Footnotes

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; PCPs, primary care practitioners.

References

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. The Maslach burnout inventory manual In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. 3rd ed Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 1997:191-218, https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/documents/faculty_staff_docs/EvaluatingStress.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103-111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-1832. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/sites/public/lifestyle/2018. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed November 11, 2019.

- 8.Del Carmen MG, Herman J, Rao S, et al. Trends and factors associated with physician burnout at a multispecialty academic faculty practice organization. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190554. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibeoni J, Bellon-Champel L, Mousty A, Manolios E, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A. Physicians’ perspectives about burnout: a systematic review and metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1578-1590. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05062-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agana DF, Porter M, Hatch R, Rubin D, Carek P. Job satisfaction among academic family physicians. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):622-625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Britt H, Pratt R. “Seeing the patient is the joy:” a focus group analysis of burnout in outpatient providers. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):273-278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Physician wellness research/surveys. Stanford Medicine WellMD website. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/center1/survey.html. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- 14.Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00117-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):11-24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: efficiency, resilience, wellness. NEJM Catalyst https://catalyst.nejm.org/physician-well-being-efficiency-wellness-resilience/. Published August 7, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2019.

- 17.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Burriss TC, Shanafelt TD. Providing primary care in the United States: the work no one sees. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1420-1421. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ofri D. Perchance to think. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(13):1197-1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1814019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum LD. Physicians’ goodness and guilt—emotional challenges of practicing medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):607-608. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talbot SG, Dean W Physicians aren’t “burning out”: they’re suffering from moral injury. STAT https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/. Published July 26, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 25.Cole TR, Carlin N. The suffering of physicians. Lancet. 2009;374(9699):1414-1415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61851-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khullar D, Wolfson D, Casalino LP. Professionalism, performance, and the future of physician incentives. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2419-2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aronson E. Back to the future: retrospective review of Leon Festinger’s “A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance”. Am J Psychol. 1997;110(1):127-137. doi: 10.2307/1423706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor MF, Bentley KJ. Professional dissonance: colliding values and job tasks in mental health practice. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41(4):469-480. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-5084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor MF. Professional dissonance. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work. 2007;77(1):89-99. doi: 10.1300/J497v77n01_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuger A. Moving on. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1763-1765.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29742371&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1801485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sax PE. Why experienced HIV/ID doctors leave clinical practice. NEJM Journal Watch blog. https://blogs.jwatch.org/hiv-id-observations/index.php/experienced-hiv-id-doctors-leave-clinical-practice/2018/05/13/. Posted May 13, 2018. Accessed July 4, 2019.

- 33.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-790. doi: 10.7326/M18-1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Scheckler WE, et al. Understanding physicians’ intentions to withdraw from practice. Health Care Manage Rev. 2001;26(1):7-19. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harkness G, Levitt P. Professional dissonance. Sociol Dev (Oakl). 2017;3(3):232. doi: 10.1525/sod.2017.3.3.232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Gill PR, Satele DV, West CP. Effect of a professional coaching intervention on the well-being and distress of physicians: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;(10):1406-1414. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):272-278. doi: 10.1370/afm.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, Poplau S, Warde C, West CP. 10 Bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):18-20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2597-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faculty development and wellbeing [homepage]. Brigham and Women’s Physicians Organization website. https://fdw.brighamandwomens.org. Accessed November 22, 2019.

- 43.Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E; Physician Moms Group Study Group . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100-e106. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, et al. Physicians’ well-being linked to in-basket messages generated by algorithms in electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1073-1078. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herzberg F. One more time: how do you motivate employees? In: Gruneberg MM, ed. Job Satisfaction—A Reader. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 1976:17-32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-02701-9_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Interview Guide