Abstract

Asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) and direct reductive amination (DRA) are both efficient transformations frequently utilized in industry. Here we combine the asymmetric hydrogenation of prochiral olefins and direct reductive amination of aldehydes in one step using hydrogen gas as the common reductant and a rhodium-Segphos complex as the catalyst. With this strategy, the efficiency for the synthesis of the corresponding chiral amino compounds is significantly improved. The practical application of this synthetic approach is demonstrated by the facile synthesis of chiral 3-phenyltetrahydroquinoline and 3-benzylindoline compounds.

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Homogeneous catalysis, Stereochemistry, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) and direct reductive amination (DRA) are both frequently utilized in chemical industry. Here, the authors combine these two transformations to efficiently convert in one step prochiral olefins into chiral amino compounds.

Introduction

Since the manufacture of l-dopa was realized as the first successful industrial-scale asymmetric catalytic process1, asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) has become the main driving force for asymmetric catalysis2–7, and the most frequently utilized homogeneous enantioselective catalytic tranformation in large scale8–17. The striding progress in AH research was evinced by Knowles18 and Noyori19 winning the Nobel prize. AH bears a few outstanding merits: first of all hydrogen gas as the reductant offers 100% atom economy; at the same time, there is a vast library of readily available chiral ligands; more importantly, the catalytic activity is prominent. The catalyst loading can be as low as 0.00002 mol%20. As a result, many important fine chemicals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are manufactured via AH of C=C, C=O and C=N bonds, including l-menthol (the most manufactured chiral compound), metolachlor (the best-selling chiral herbicide), dextromethorphan, fluoxetine and sitagliptin2–17.

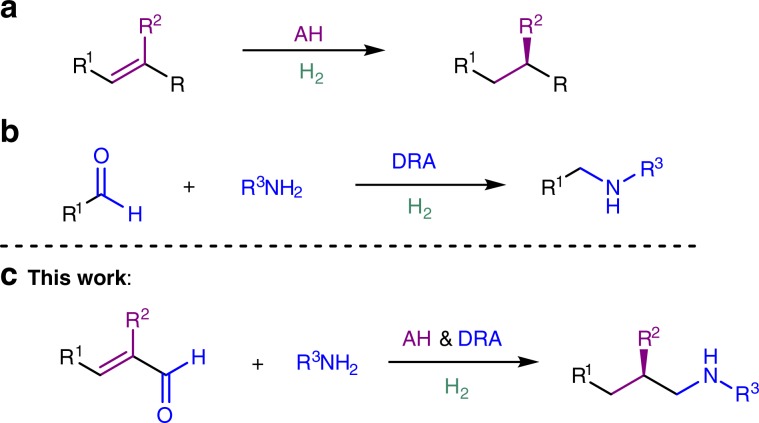

At the other hand, direct reductive amination (DRA), a one-pot procedure for the construction of C–N bond in which the mixture of carbonyl compound and nitrogen-containing compound is subjected to a reducing agent with H2O as the sole by-product, is a key transformation in organic chemistry21–41. It has been developed into one of the most practical methods for the synthesis of amino pharmaceutical compounds. Common reducing agents include H2, borohydride, formate, silane, isopropyl alcohol and Hantzsch esters. Transition metal-catalyzed DRA using molecular hydrogen as the reducing reagent is highly sustainable in terms of reaction waste control and atom-economy. As both AH and DRA share the same reductant, H2, we propose to combine these two reactions to make the procedure for the synthesis of chiral amino compounds more concise and proficient (Fig. 1). To achieve this purpose, two major challenges have to be addressed: the discovery of a catalytic system which can perform reduction of two different types of bonds (C=N and C=C bonds) and the suppression of side-reactions, namely aldehyde and/or olefin reduction, which might take place before the proposed AH–DRA reaction sequence. We envisioned two strategies that may help to tackle those problems. One is the application of a transition metal which could efficiently coordinate and reduce both the imine bond and the olefin bond. The other is the addition of appropriate additives which facilitate the imine formation and the reduction thereafter, and alleviate the inhibition effect from the amine reactant, imine intermediate and the amine product on the catalyst. Fan and co-workers just disclosed an elegant Ir/Ru-catalyzed AH and DRA of quinoline-2-carbaldehydes with anilines42.

Fig. 1. The combination of asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) and direct reductive amination (DRA).

a Asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins. b Direct reductive amination of aldehydes. c This work: the combination of asymmetric hydrogenation and direct reductive amination.

Herein, we describe our efforts toward the integration of AH of olefins and DRA of aldehydes into a one-step cascade reaction. Through the incorporated AH and DRA sequential reactions in one step, the synthetic efficiency of related chiral amino compounds is significantly improved.

Results

Establishment of feasibility

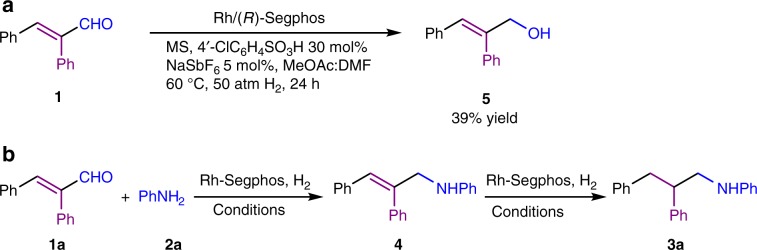

In our previous direct asymmetric reductive amination research, iridium catalyst demonstrated prominent reactivity toward imine reduction43–45. So [Ir(cod)Cl]2 precursor along with (R)-Segphos was initially evaluated in the reaction of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 1a and aniline 2a. Unfortunately only side-product 5 was obtained. Since Brønsted acids have been extensively used in reductive amination to promote the imine formation and imine reduction46–50, 30 mol% p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH) was added to the reaction. As expected, TsOH boosted the imine formation and imine reduction to afford 21% product 3a at 64% ee, with 75% intermediate 4 been formed (Table 1, entry 2). When the metal precursor was switched to [Rh(cod)Cl]2, TsOH again exercised positive effects on the reaction (entry 4). At the same time, it suppressed the aldehyde direct reduction. From the results, we can see rhodium was more capable of olefin reduction than iridium. In the brief solvents screening (Table 1, entries 4–8), ethyl acetate, which possesses moderate coordinating ability, provided the highest ee. Next, a few Brønsted acids were examined (Table 1, entries 8–11), among which 4-chlorobenzenesulfonic acid facilitated the catalytic system for better reactivity as well as higher stereoselectivity than other acids. Then the influence of the counterion of the cationic Rh complex was studied51,52. The results demonstrated that the coordinating anions, such as iodide (Table 1, entry 16) and acetate (Table 1, entry 12), deactivated the reaction, while the noncoordinating anion hexafluoroantimonate improved both the reactivity and the selectivity (Table 1, entry 14). Since the coordinating species had influence on the reaction selectivity, we tried some solvents with coordination ability. It turned out the addition of N,N-dimethyllformamide (DMF) to MeOAc (at the ratio of 1:4) enhanced the reaction ee to 98% (Table 1, entry 17). A control experiment, in which aniline 2a was not added, afforded 5 in 39% yield with 61% substrate 1a remaining under the same reaction conditions as in entry 17 (Fig. 2a). The above results demonstrated that the construction of the C–N bond beforehand helped to pave the way for the C=C bond reduction (Fig. 2b).

Table 1.

Initial AH & DRA investagation of 2,3-diphenylacrylaldehyde 1a and aniline 2a.a

| Entry | Metal precursor | Solvent | Additiveb | Yield of 3a (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [Ir(cod)Cl]2 | THF | – | – | – |

| 2 | [Ir(cod)Cl]2 | THF | TsOH | 21 | 64 |

| 3 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | THF | – | – | – |

| 4 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | THF | TsOH | 46 | 82 |

| 5 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | TsOH | 68 | 75 |

| 6 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | CH2Cl2 | TsOH | 91 | 52 |

| 7 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | toluene | TsOH | 89 | 63 |

| 8 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | MeOH | TsOH | 57 | 18 |

| 9 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | PhCO2H | – | – |

| 10 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H | 85 | 81 |

| 11 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | MeSO3H | 52 | 70 |

| 12 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H NaOAc | 57 | 81 |

| 13 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H NaBF4 | 72 | 86 |

| 14 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H NaSbF6 | 90 | 93 |

| 15 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H NaBArf | 34 | 67 |

| 16 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | EtOAc | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H KI | 33 | 60 |

| 17 | [Rh(cod)Cl]2 | MeOAc/DMF 4:1 | 4′-ClC6H4SO3H NaSbF6 | 98 | 98 |

aReaction conditions: [Rh]/Segphos/1a/2a = 1:1.1:100:100; 1a 0.1 mmol, solvent 2 mL, 60 °C, 24 h. Segphos = 5,5′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-4,4′-bi-1,3-benzodioxole. MS = molecular sieves, 0.1 g. Yields were isolated yields. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by chiral HPLC.

bThe amount of added Brønsted acids was 30 mol%. The amount of added counterions was 5 mol%.

Fig. 2. The order of reduction of C=N and C=C bonds.

a The reduction of 1 without the addition of aniline 2a. b The reduction of 1 with the addition of aniline 2a.

Examination of substrate scope

With the optimal conditions using the rhodium/Segphos catalyst and the additive set in hand, we first explored the scope of the α,β-unsaturated aldehydes in the AH and DRA reactions with aniline 2a (Table 2). In most cases, the aldehyde substrates could be transformed into the corresponding chiral amino compounds in excellent enantioselectivity and high yields. Regarding the substituted aromatic groups connected to the chiral center (R2) of the products, when the substituents were on para- or meta-positions, the corresponding products were obtained with more than 95% ee and 90% yields, regardless of their electron-donating (3b–3e, 3h–3j) or electron-withdrawing (3f–3g, 3k) properties; but when the substituents were on ortho-positions (3l–3n) or as 1-naphthyl group (3p), the reaction required higher catalyst loading and/or reaction temperature, probably due to the greater steric hindrance. The additive set and catalytic system also worked well for heteroaromatic substrate 1q and aliphatic group substituted 1r. It is worth mentioning that protic groups –OH (3e) and –NHAc (3i), and reducible group –CN (3k) were well-tolerated in the reactions. As for the various –R1 substrates, the results were similar to that of the –R2 substituted ones. As for the limitations of the reaction, the catalytic system did not work well when R1 and R2 were both alkyl groups (3zb), or the α-substituent was switched to β-position (3zc). Alkyl amine was also not suitable for this method (3zd). The reactions of 2-phenylbut-2-enal (1ze) with 2a did not lead to the desired products. As for 3,4-diphenylbut-3-en-2-one (1zf), most of the starting material 1zf remained untouched.

Table 2.

Investigation of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde scope.a

|

aReaction conditions: [Rh]/Segphos/1/2a = 1:1.1:100:100; 1 0.3 mmol, solvent 4 mL with the MeOAc/DMF ratio at 4:1, 60 °C, 24 h. MS = molecular sieves, 0.3 g. Yields were isolated yields. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by chiral HPLC. PMP = 4-methoxyphenyl.

b2 mol% Rh–(R)-DM-Segphos was used. No NaSbF6 was added. DM-Segphos = 5,5′-Bis[di(3,5-xylyl)phosphino]-4,4′-bi-1,3-benzodioxole.

c2 mol% catalyst was used.

dThe amine source was p-anisidine. The reaction temperature was 70 °C.

eThe amine source was p-anisidine.

Then the scope of anilines was explored using the same catalytic system under the optimized conditions. The results are summarized in Table 3. All selected anilines, with substituents at para- (3ab–3ad), meta- (3ae–3ag) and ortho- (3ah–3aj) positions, or having electronic-withdrawing or electronic-donating groups, reductively coupled with the 2,3-diphenylacrylaldehyde substrate 1a smoothly to afford the desired products in excellent ees and yields. Notably the protic –OH group (2i) again tolerated in this transformation. In addition, sterically hindered anilines, with ortho-substituents (2 h, 2j) and 1-naphthyl group (2k), were all suitable nitrogen sources for the successful convertion of 1a.

Table 3.

Examination of the aniline scope.a

|

aReaction conditions: [Rh]/Segphos/1a/2 = 1:1.1:100:100, 1a 0.3 mmol, solvent 4 mL with the MeOAc/DMF ratio at 4:1, 60 °C, 24 h. MS = molecular sieves, 0.3 g. Yields were isolated yields. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by chiral HPLC.

Practical applications

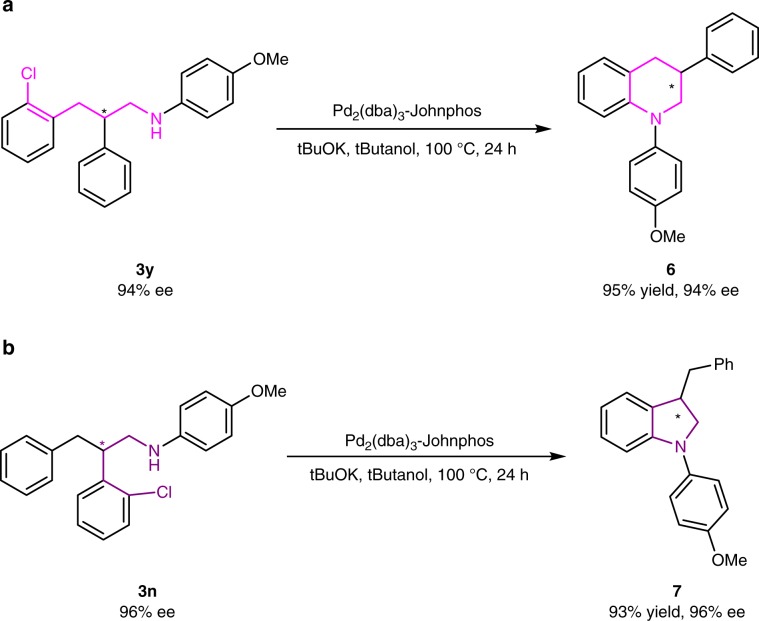

To further showcase the utility of this AH and DRA conbination strategy, we next made efforts on the transformations of these N-(2,3-diarylpropyl)aniline products 3. Tetrahydroquinolines are prevailing natural alkaloids and artificially synthesized molecules, which have found frequent applications in pharmaceutical and agrochemical industry53–56. The AH of readily available quinolines is the most convenient and straightforward access to these compounds6,57. But the 3-substituted tetrahydroquinolines could not be prepared through this route, since under the typical acidic AH reaction conditions, the 1,4-dihydroquinoline intermediates would undergo isomerization to form 1,2-dihydroquinoline, in which it is hard to control the stereoselectivity6,58. Using our methodology, product 3y from the 3-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-phenylacrylaldehyde 1y substrate could easily been converted into the chiral 3-phenyl-tetrahydroquinoline product 6 via the Buchwald–Hartwig cross-coupling reaction (Fig. 3a), in which the ee value was not affected59–61. Similarly, product 3n from the 2-(2-chlorophenyl)-3-phenylacrylaldehyde 1n substrate could be cyclized to form the 3-benzylindoline alkaloid 7 (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Synthesis of a 3-tetrahydroquinoline and a 3-indoline.

a The transformation of 3y for the synthesis of 3-phenyl-tetrahydroquinoline 6. b The transformation of 3n for the synthesis of 2-benzyl-indoline 7.

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully integrated in one-pot two efficient reactions, AH and DRA, which share the common reductant, namely hydrogen gas. Catalyzed by the rhodium-Segphos complex, the DRA of aldehydes and the AH of prochiral olefins took place sequencially to afford the chiral amino compounds. The rhodium catalyst precursor was capable of performing the reduction of two different types of bonds. The addition of 30 mol% of 4-chlorobenzenesulfonic acid facilitated the imine formation, imine reduction and the C=C bond reduction. Noncoordinated counterion of the cationic rhodium complex hexafluoroantimonate improved both the reaction reactivity and the stereoselectivity. With our protocol, useful chiral amino compounds can be synthesized in a more convenient and effective manner.

Methods

General procedure for asymmetric reductive amination

In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, [Rh(cod)Cl]2 (5 μmol) and (R)-Segphos (11 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous CH3COOCH3 (1.0 mL), stirred for 20 min, and equally divided into 10 vials charged with aldehyde (0.1 mmol) and aniline (0.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH3COOCH3 solution (0.5 mL). Then 4-Cl–PhSO3H (0.3 equiv.) and NaSbF6 (0.05 equiv) were added and the total solution was made to 2.0 mL (MeOAc:DMF = 4:1) for each vial. The resulting vials were transferred to an autoclave, which was charged with 50 atm of H2, and stirred at 60 °C for 24 h. The hydrogen gas was released slowly and the solution was quenched with aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution. The organic phase was concentrated and passed through a short column of silica gel to remove the metal complex to give the crude products, which were purified by column chromotography and then analyzed by chiral HPLC to determine the enantiomeric excesses.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21772155) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

S.Y. established the reaction conditions. G.G. and C.L. prepared the substrates. S.Y., L.Wang., L.Wan., H.H. and H.G. expanded the substrate scope. M.C. conceived and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The experimental procedure and characterization data of new compounds are available within the Supplementary Information. Any further relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks John Brown and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haizhou Huang, Email: huanghai30@163.com.

Huiling Geng, Email: genghuiling@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Mingxin Chang, Email: mxchang@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-14475-x.

References

- 1.Vineyard BD, Knowles WS, Sabacky MJ, Bachman GL, Weinkauff DJ. Asymmetric hydrogenation. Rhodium chiral bisphosphine catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:5946–5952. doi: 10.1021/ja00460a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohkuma, T., Kitamura, M. & Noyori, R. In Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis 2nd edn (ed Ojima, I.) (Wiley, New York, 2000).

- 3.Tang W, Zhang X. New chiral phosphorus ligands for enantioselective hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3029–3269. doi: 10.1021/cr020049i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie J-H, Zhu S-F, Zhou Q-L. Transition metal-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogenation of enamines and imines. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1713–1760. doi: 10.1021/cr100218m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D-S, Chen Q-A, Lu S-M, Zhou Y-G. Asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroarenes and arenes. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2557–2590. doi: 10.1021/cr200328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verendel JJ, Pàmies O, Diéguez M, Andersson PG. Asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins using chiral crabtree-type catalysts: scope and limitations. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2130–2169. doi: 10.1021/cr400037u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Butt NA, Zhang W. Asymmetric hydrogenation of nonaromatic cyclic substrates. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:14769–14827. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genet J-P. Asymmetric catalytic hydrogenation. Design of new Ru catalysts and chiral ligands: from laboratory to industrial applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:908–918. doi: 10.1021/ar020152u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz CS, Krska SW. Unlocking the potential asymmetric hydrogenation at Merck. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1320–1326. doi: 10.1021/ar700141v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaser, H. & Federsel, H. (eds.) Asymmetric Catalysis On Industrial Scale: Challenges, Approaches And Solutions 2nd edn (Wiley-VCH, 2010).

- 11.Palmer AM, Zanotti-Gerosa A. Homogenous asymmetric hydrogenation: recent trends and industrial applications. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2010;13:698–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busacca CA, Fandrick DR, Song JJ, Senanayake CH. The growing impact of catalysis in the pharmaceutical industry. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:1825–1864. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201100488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ager DJ, de Vries AHM, de Vries JG. Asymmetric homogeneous hydrogenations at scale. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3340–3380. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15312b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magano J, Dunetz JR. Large-scale carbonyl reductions in the pharmaceutical industry. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012;16:1156–1184. doi: 10.1021/op2003826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ager DJ. Popular synthetic approaches to pharmaceuticals. Synthesis. 2015;47:760–768. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1379733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayler JD, Leahy DK, Simmons EM. A pharmaceutical industry perspective on sustainable metal catalysis. Organometallics. 2019;38:36–46. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo CSG, Morris RH. Catalytic homogeneous asymmetric hydrogenation: successes and opportunities. Organometallics. 2019;38:47–65. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles WS. Asymmetric hydrogenations (Nobel lecture 2001) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1998–2007. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<1998::AID-ANIE1998>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noyori R. Asymmetric catalysis: science and opportunities (Nobel lecture 2001) Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003;345:15–32. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200390002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie J-H, Liu X-Y, Xie J-B, Wang L-X, Zhou Q-L. An additional coordination group leads to extremely efficient chiral iridium catalysts for asymmetric hydrogenation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7329–7332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nugent TC, El-Shazly M. Chiral amine synthesis–recent developments and trends for enamide reduction, reductive amination, and imine reduction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:753–819. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200900719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez S, Peters JA, Maschmeyer T. The reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones and the hydrogenation of nitriles: mechanistic aspects and selectivity control. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002;344:1037–1057. doi: 10.1002/1615-4169(200212)344:10<1037::AID-ADSC1037>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripathi RP, Verma SS, Pandey J, Tiwari VK. Recent development on catalytic reductive amination and applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 2008;12:1093–1115. doi: 10.2174/138527208785740283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Magid AF, Mehrman SJ. A review on the use of sodium triacetoxyborohydride in the reductive amination of ketones and aldehydes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006;10:971–1031. doi: 10.1021/op0601013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storer RI, Carrera DE, Ni Y, MacMillan DWC. Enantioselective organocatalytic reductive amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:84–86. doi: 10.1021/ja057222n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhuebel D, Sun Y, Matsumura K, Sayo N, Saito T. Direct asymmetric reductive amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11316–11317. doi: 10.1021/ja905143m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakchaure VN, Zhou J, Hoffmann S, List B. Catalytic asymmetric reductive amination of α-branched ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4612–4614. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savile CK, et al. Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from ketones applied to sitagliptin manufacture. Science. 2010;329:305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1188934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Pettman A, Bacsa J, Xiao J. A versatile catalyst for reductive amination by transfer hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7548–7552. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao X, Xie Y, Su C, Liu M, Shi Y. Organocatalytic asymmetric biomimetic transamination: from α-keto esters to optically active α-amino acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12914–12917. doi: 10.1021/ja203138q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strotman NA, et al. Reaction development and mechanistic study of a ruthenium catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric reductive amination en route to the dual orexin inhibitor Suvorexant (MK-4305) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8362–8371. doi: 10.1021/ja202358f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werkmeister S, Junge K, Beller M. Copper-catalyzed reductive amination of aromatic and aliphatic ketones with anilines using environmental-friendly molecular hydrogen. Green Chem. 2012;14:2371–2374. doi: 10.1039/c2gc35565e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon RC, Richter N, Busto E, Kroutil W. Recent developments of cascade reactions involving ω-transaminases. ACS Catal. 2014;4:129–143. doi: 10.1021/cs400930v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pavlidis IV, et al. Identification of (S)-selective transaminases for the asymmetric synthesis of bulky chiral amines. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:1076–1082. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagadeesh RV, et al. MOF-derived cobalt nanoparticles catalyze a general synthesis of amines. Science. 2017;358:326–332. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou H, Liu Y, Yang S, Zhou L, Chang M. One-pot N-deprotection and catalytic intramolecular asymmetric reductive amination for the synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:2725–2729. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aleku GA, et al. A reductive aminase from Aspergillus oryzae. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:961–969. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallardo-Donaire J, et al. Direct asymmetric ruthenium-catalyzed reductive amination of alkyl−Aryl ketones with ammonia and hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:355–361. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan X, et al. Asymmetric synthesis of chiral primary amines by ruthenium-catalyzed direct reductive amination of alkyl aryl ketones with ammonium salts and molecular H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:2024–2027. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lou Y, et al. Dynamic kinetic asymmetric reductive amination: synthesis of chiral primary β-amino lactams. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:14193–14197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayol O, et al. A family of native amine dehydrogenases for the asymmetric reductive amination of ketones. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:324–333. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0249-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Pan Y, He Y-M, Fan Q-H. Consecutive intermolecular reductive amination/asymmetric hydrogenation: facile access to sterically tunable chiral vicinal diamines and N‐heterocyclic carbenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:16831–16834. doi: 10.1002/anie.201909919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H, Liu X, Zhou L, Chang M, Zhang X. Direct asymmetric reductive amination for the synthesis of chiral β-arylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:5309–5312. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Zhou L, Chang M. Direct catalytic asymmetric reductive amination of aliphatic ketones utilizing diphenylmethanamine as coupling partner. Org. Lett. 2017;19:1942–1945. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Z, et al. Secondary amines as coupling partners in direct catalytic asymmetric reductive amination. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:4509–4514. doi: 10.1039/C9SC00323A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogl EM, Groeger H, Shibasaki M. Towards perfect asymmetric catalysis: additives and cocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1570–1577. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1570::AID-ANIE1570>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Z, Jin W, Jiang Q. Brønsted acid activation strategy in transition-metal catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of N-unprotected imines, enamines, and N-heteroaromatic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:6060–6072. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong L, Sun W, Yang D, Li G, Wang R. Additive effects on asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:4006–4123. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blaser, H.-U., Buser, H.-P., Jalett, H.-P., Pugin, B. & Spindler, F. Iridium ferrocenyl diphosphine catalyzed enantioselective reductive alkylation of a hindered aniline. Synlett.1999, 867−868 (1999).

- 50.Li C, Villa-Marcos B, Xiao J. Metal-Brønsted acid cooperative catalysis for asymmetric reductive amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6967–6969. doi: 10.1021/ja9021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smidt SP, Zimmermann N, Studer M, Pfaltz A. Enantioselective hydrogenation of alkenes with iridium–PHOX catalysts: a kinetic study of anion effects. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:4685–4693. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno A, et al. PGSE NMR diffusion overhauser studies on [Ru(Cp*)(η6‐arene)][PF6], plus a variety of transition-metal, inorganic, and organic salts: an overview of ion pairing in dichloromethane. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:5617–5629. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sridharan V, Suryavanshi P, Men´endez JC. Advances in the chemistry of tetrahydroquinolines. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7157–7259. doi: 10.1021/cr100307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott JD, Williams RM. Chemistry and biology of the tetrahydroisoquinoline antitumor antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1669–1730. doi: 10.1021/cr010212u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bentley KW. β-Phenylethylamines and the isoquinoline alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:444–463. doi: 10.1039/B509523A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barton, D. H. R., Nakanishi, K. & Meth-Cohn, O. (eds.) Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry (Elsevier, Oxford, 1999).

- 57.Zhou Y. Asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroaromatic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1357–1366. doi: 10.1021/ar700094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang D-W, et al. Highly enantioselective iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of 2-benzylquinolines and 2-functionalized and 2,3-disubstituted quinolones. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:2780–2787. doi: 10.1021/jo900073z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paul F, Patt J, Hartwig JF. Palladium-catalyzed formation of carbon-nitrogen bonds. Reaction intermediates and catalyst improvements in the hetero cross-coupling of aryl halides and tin amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5969–5970. doi: 10.1021/ja00092a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guram AS, Buchwald SL. Palladium-catalyzed aromatic aminations with in situ generated aminostannanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7901–7902. doi: 10.1021/ja00096a059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruiz-Castillo P, Buchwald SL. Applications of palladium-catalyzed C-N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:12564–12649. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The experimental procedure and characterization data of new compounds are available within the Supplementary Information. Any further relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.