In this study, using electronic health record data for a multisite, multistate primary care cohort, we evaluate WCC adherence among children with IOE.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

For children with intrauterine opioid exposure (IOE), well-child care (WCC) provides an important opportunity to address medical, developmental, and psychosocial needs. We evaluated WCC adherence for this population.

METHODS:

In this retrospective cohort study, we used PEDSnet data from a pediatric primary care network spanning 3 states from 2011 to 2016. IOE was ascertained by using physician diagnosis codes. WCC adherence in the first year was defined as a postnatal or 1-month visit and completed 2-, 4-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month visits. WCC adherence in the second year was defined as completed 15- and 18-month visits. Gaps in WCC, defined as ≥2 missed consecutive WCC visits, were also evaluated. We used multivariable regression to test the independent effect of IOE status.

RESULTS:

Among 11 334 children, 236 (2.1%) had a diagnosis of IOE. Children with IOE had a median of 6 WCC visits (interquartile range 5–7), vs 8 (interquartile range 6–8) among children who were not exposed (P < .001). IOE was associated with decreased WCC adherence over the first and second years of life (adjusted relative risk 0.54 [P < .001] and 0.74 [P < .001]). WCC gaps were more likely in this population (adjusted relative risk 1.43; P < .001). There were no significant adjusted differences in nonroutine primary care visits, immunizations by age 2, or lead screening.

CONCLUSIONS:

Children <2 years of age with IOE are less likely to adhere to recommended WCC, despite receiving on-time immunizations and lead screening. Further research should be focused on the role of WCC visits to support the complex needs of this population.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Children of mothers with opioid use disorder have increased risk for adverse health and developmental outcomes. Well-child care visits provide an important opportunity to support these children and their families through screening, anticipatory guidance, and connection to resources.

What This Study Adds:

In this retrospective analysis of children <2 years of age, we found decreased well-child care adherence associated with intrauterine opioid exposure. Further research should be focused on pediatric engagement of mothers with opioid use disorder to support their complex needs.

In 2017, the opioid crisis was deemed a public health emergency by the US Department of Health and Human Services.1 Increasingly, pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) and their children are part of this crisis, giving rise to a range of unique health care challenges related to intrauterine opioid exposure (IOE). It is now estimated that every 15 minutes in the United States, another infant is born experiencing the constellation of withdrawal symptoms resulting from IOE known as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).2 A large and growing body of research has been focused on their perinatal care, including NAS prevention and treatment. However, for all children with IOE (regardless of whether they experienced NAS), important gaps remain in understanding health care use and outcomes after discharge from the hospital.3–5

Within a primary care setting, well-child care (WCC) visits provide an important opportunity for providers to identify and address information gaps, behavioral and developmental concerns, growth and nutritional challenges, and medical and psychosocial issues.6 Previous studies reveal the benefits of a number of aspects of WCC, including, but not limited to, immunizations, developmental screening, anticipatory guidance, maternal depression screening, and reading promotion.7–12 Among children <2 years of age, WCC adherence is associated with improved health outcomes, including reduced hospitalizations and emergency department use, as well as improved kindergarten readiness.13–15

Unfortunately, numerous challenges for mothers with OUD threaten their engagement in pediatric primary care. In addition to traditional barriers, such as lack of transportation, time constraints, and family crises, additional challenges include perceived stigmatization and discrimination.16 Mothers with OUD may feel overwhelmed by parenting and by their own engagement in substance use treatment or may feel guilty, judged, or removed from the care of their child.17,18 One recent study of mothers in treatment for OUD suggests that one-third of their children did not adhere to recommended WCC during infancy, and this outcome worsened over time.19 To date, there is a lack of large-scale studies in which WCC adherence is evaluated among children with IOE. Our objective was to determine the association between IOE and WCC adherence over the first 2 years of life in a multistate primary care cohort. We hypothesized that, independent of other clinical and social risk factors, IOE would be associated with decreased WCC adherence.

Methods

Study Population and Setting

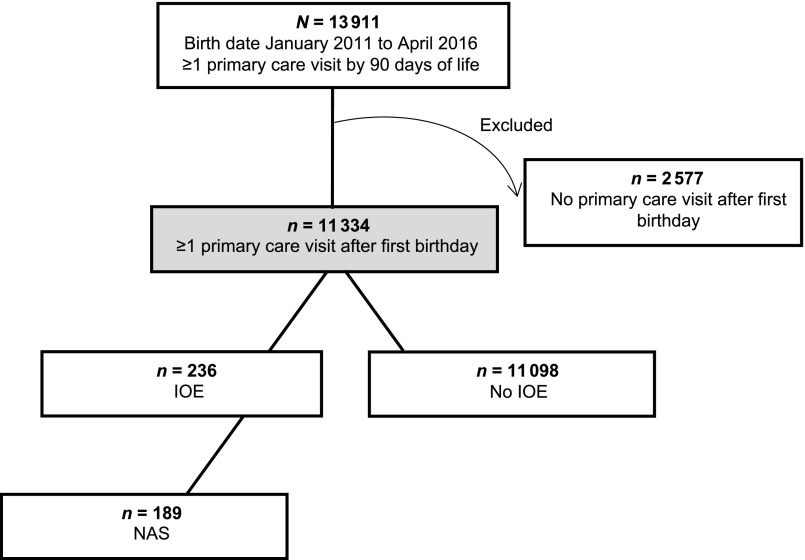

Data for this retrospective cohort study were obtained from PEDSnet, a longitudinal electronic health record database comprising 8 of the largest US pediatric academic health centers. PEDSnet currently contains 191 data elements across 15 domains, examples of which include patient age, race, zip code, and encounter dates. Data quality processes are performed by the PEDSnet Coordinating Center on quarterly cycles.20 Our analysis included all children born January 1, 2011, to April 30, 2016, who completed a visit within 90 days of life at 1 of 35 primary care sites within a single children’s health system spanning Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Florida. Infants ≥90 days old at their first appointment were excluded because of concerns that they might have received initial primary care elsewhere. Although this had the effect of omitting those with a prolonged neonatal hospitalization, we anticipated that most children requiring NAS treatment would have been discharged from the hospital within this time frame.21,22 To help further ensure that the cohort represented those who had established care within this system, thereby minimizing missing data bias, we excluded children without any type of primary care visit after their first birthday. The sample derivation is depicted in Fig 1. This study was approved by the Nemours Children’s Health System Institutional Review Board.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of sample derivation. The arrow curving outward depicts observations excluded from the analysis. The gray box depicts the final cohort included for analysis.

Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was WCC adherence based on American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations and derived from Current Procedural Terminology codes. The following time intervals were used to define WCC visits up to the second birthday: 0 to 14 days (postnatal), 15 to 41 days (1 month), 42 to 90 days (2 months), 91 to 150 days (4 months), 151 to 210 days (6 months), 211 to 335 days (9 months), 336 to 425 days (12 months), 426 to 517 days (15 months), and 518 to 730 days (18 months). WCC adherence in the first year was defined as a completed postnatal or 1-month visit and completed 2-, 4-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month visits. WCC adherence in the second year was defined as completing 15- and 18-month visits. Gaps in WCC throughout the first 2 years were also evaluated, defined as missing ≥2 consecutive WCC visits.

Secondary outcomes included the number of nonroutine visits over the first 2 years of life, immunization status by age 2 years, and lead level screening at 1 year.23 On-time immunization status was defined as receipt of the combined 7-vaccine series (4:3:1:3:3:1:4) by age 2 per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which includes ≥4 doses of the diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine, ≥3 doses of the poliovirus vaccine, ≥1 dose of the measles-containing vaccine, ≥3 or ≥4 doses (depending on product type) of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, ≥3 doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, ≥1 dose of the varicella vaccine, and ≥4 doses of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.24 On-time lead screening was defined as screening performed by 425 days of life or 2 months after the first birthday.

IOE was measured by using physician-recorded diagnosis data, which, in PEDSnet, include visit and problem list diagnoses. In PEDSnet, diagnosis data are standardized by using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terminology (SNOMED-CT), a terminology with greater granularity than the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). For this study, IOE was ascertained by using a combination of SNOMED-CT and ICD codes because correspondence between these 2 terminologies is often not 1:1, with some ICD codes mapping to multiple, more specific SNOMED-CT codes and, conversely, some SNOMED-CT codes mapping to multiple, more specific ICD codes (see Supplemental Table 5).

On the basis of existing literature on WCC use, we assessed clinical and sociodemographic covariates, including child race, ethnicity, sex, insurance type, birth weight, and gestational age.25–27 An indicator variable identifying complex chronic conditions was derived by using a previously established classification system.28 Given the known association between community-level effects and health care use, patient zip code was linked to US Census Bureau data to derive an area-level measure of the percentage of residents living below the federal poverty level.29,30 Publicly available rural-urban commuting area codes from the US Department of Agriculture were also used to assign metropolitan zip codes of residence. On the basis of distribution of this variable, zip codes were classified as nonmetropolitan if designated as micropolitan, a small town, or rural.31

Analysis

Bivariate comparisons were conducted by using χ2 (proportions) and Wilcoxon rank tests (nonnormally distributed count measures). Next, multivariable regression modeling was used to test the association between IOE and a binary outcome of WCC adherence in the first year of life, with adjustment for all covariates. Because WCC adherence was not a rare outcome (occurring in >10% of the sample), we used generalized linear models with a log link and Poisson distribution to produce an unbiased estimate of the adjusted relative risk (aRR).32,33 To account for the increased possibility of prolonged birth hospitalization during the first months of life among infants with IOE, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis by relaxing the definition of WCC adherence in the first year, measuring only those visits at 4, 6, 9, and 12 months of age. We then performed a separate analysis to test the association between IOE and WCC adherence in the second year to determine if findings attenuated or were consistent over time. We used this same approach to test the association between IOE and ≥1 WCC gap over the first 2 years. Next, we tested the association between IOE and the count of nonroutine visits using multivariable negative binomial regression (a likelihood ratio test of overdispersion was used to confirm that Poisson distribution was not appropriate). Finally, we used generalized linear models as above to evaluate on-time immunization status and lead screening. For all regression models, multicollinearity was assessed by using variance inflation factors, and clustering by primary care site was adjusted by using robust variance estimation. The percentage of missing data across all analytic variables was low (<5%); therefore, a case-complete analysis, rather than imputation methods, was performed.34 All analyses were conducted by using Stata 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

In total, 11 334 children were included in the analytic cohort (Fig 1). Of this sample, 236 (2.1%) had a diagnosis of IOE, the majority of whom (80.1%) were classified as having NAS. As shown in Table 1, those with IOE were significantly more likely to be white and insured by Medicaid compared with children without IOE. Children with IOE also had a lower average birth weight and were more likely to live in higher-poverty areas. No differences were observed in gestational age, diagnosis of complex chronic condition(s), sex, or metropolitan residence.

TABLE 1.

Study Population by IOE

| IOE, n = 236 | No IOE, n = 11 098 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Race, % (n) | <.001 | ||

| White | 69.1 (163) | 34.8 (3865) | |

| African American | 15.7 (37) | 44.4 (4925) | |

| Asian American | 0 (0) | 2.9 (323) | |

| Other | 13.6 (32) | 13.8 (1532) | |

| Unknown | 1.7 (4) | 4.1 (453) | |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | .01 | ||

| Hispanic | 11.0 (26) | 12.5 (1387) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 88.6 (209) | 83.5 (9265) | |

| Unknown | 0.4 (1) | 4.0 (446) | |

| Insurance, % (n) | <0.001 | ||

| Medicaid | 97.9 (231) | 66.7 (7404) | |

| Private | 1.4 (4) | 32.8 (3645) | |

| Other or unknown | 0.4 (1) | 0.4 (49) | |

| Birth wt, g, mean | 3048.4 | 3353.1 | <.001b |

| Gestational age, wk, mean | 38.0 | 38.2 | .14b |

| Complex chronic condition, % (n) | 16.5 (39) | 15.9 (1762) | .78a |

| Child sex male, % (n) | 50.0 (118) | 51.9 (5763) | .56a |

| Area-level poverty, % | 17.5 | 15.9 | .02a |

| Metropolitan versus nonmetropolitan zip code, % (n) | 97.5 (230) | 95.2 (10 566) | .11a |

| Outcomes | |||

| WCC adherence, % (n) | |||

| Birth to 12 mo | 25.9 (61) | 54.7 (6068) | <.001a |

| 4–12 mo | 39.8 (94) | 58.2 (6459) | <.001a |

| 12–24 mo | 41.5 (98) | 57.5 (6377) | <.001a |

| ≥1 WCC gap, % (n) | 42.8 (101) | 27.8 (3085) | <.001a |

| No. nonroutine visits, median (IQR) | 9.5 (7–14) | 11 (8–15) | .005b |

| On-time immunization status,c % (n) | 83.9 (198) | 85.8 (9526) | .40a |

| Lead screening at 1 y, % (n) | 62.3 (147) | 52.9 (5875) | .004a |

Totals for some variables may not add to 100% because of missing data. IQR, interquartile range.

χ2 P value.

Wilcoxon rank test P value.

Receipt of the combined 7-vaccine series (4:3:1:3:3:1:4) by age 2 y per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which includes ≥4 doses of the diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine, ≥3 doses of the poliovirus vaccine, ≥1 dose of the measles-containing vaccine, ≥3 or ≥4 doses (depending on the product type) of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, ≥3 doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, ≥1 dose of the varicella vaccine, and ≥4 doses of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

WCC Adherence

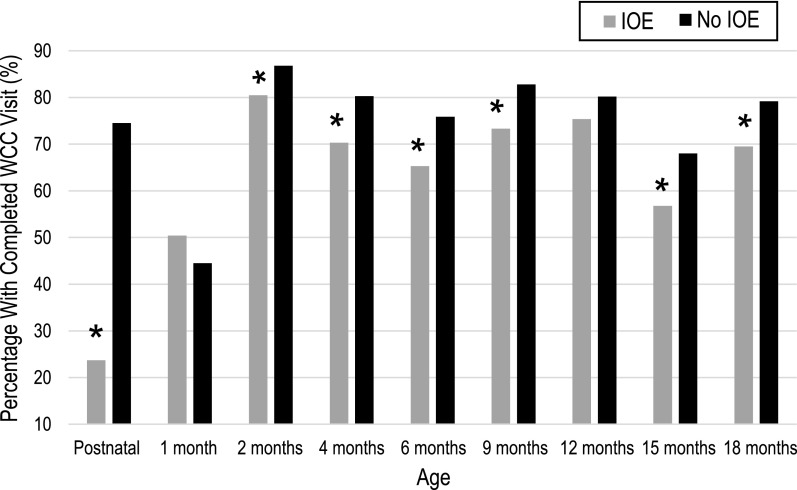

Overall, 54.1% of all children in the study adhered to recommended WCC in the first year, and 57.1% in the second year. As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences between children with and without IOE (25.9% vs 54.7% in the first year and 41.5% vs 57.5% in the second year; P < .001). The median number of WCC visits was lower among children with IOE compared with those without (median [interquartile range]: 6 [5–7] vs 8 [6–8]; P < .001). Attendance was highest in both groups for the 2-month WCC visit (see Fig 2).

FIGURE 2.

WCC visit completion over time. Gray bars represent children with IOE. Black bars represent children without IOE. The y-axis represents the percentage who completed at least 1 WCC visit during each age interval, shown on the x-axis. * P < .05.

In the multivariable regression, IOE was associated with decreased WCC adherence in the first year (aRR 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–0.74; Table 2). Additional factors associated with WCC adherence included race, ethnicity, insurance, low birth weight, and area-level poverty. In the sensitivity analysis for evaluating WCC adherence starting at 4 months, the effect size associated with IOE was smaller but still significant (aRR 0.74; 95% CI 0.66–0.83; results not shown); however, the association with low birth weight was no longer significant (aRR 1.01; 95% CI 0.96–1.16). Other model parameters were substantively unchanged in the sensitivity analysis.

TABLE 2.

aRRs for WCC Adherence Over the First and the Second Year of Life

| WCC Adherence Over the First Year, aRR (95% CI)a | WCC Adherence Over the Second Year, aRR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| IOE | 0.54 (0.39–0.74)* | 0.77 (0.68–0.87)* |

| Child race | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| African American | 0.79 (0.70–0.89)* | 0.84 (0.77–0.92)* |

| Asian American | 0.93 (0.85–1.02) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) |

| Other | 0.88 (0.80–0.96)* | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) |

| Unknown | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | Reference | Reference |

| Hispanic | 1.10 (1.02–1.18)* | 1.13 (1.09–1.18)* |

| Unknown | 1.05 (0.89–1.22) | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Medicaid | 0.71 (0.65–0.78)* | 0.77 (0.74–0.80)* |

| Other or unknown | 0.88 (0.70–1.09) | 0.82 (0.66–1.03) |

| Low birth wt <2500 g | 0.85 (0.79–0.91)* | 1.06 (1.00–1.12)* |

| Complex chronic condition | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 1.06 (1.02–1.11)* |

| Child sex | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

| Area-level povertyb | 0.99 (0.98–0.99)* | 0.99 (0.99– <1.00)* |

| Metropolitan residence | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

Generalized linear models with a log link and Poisson distribution.

Adjusted for all variables listed in the table, year of birth as a fixed effect, and clustering by practice by using robust variance estimation.

The coefficient represents a change in the relative risk per 1% increase.

P < .05.

In the second year, IOE was associated with decreased WCC adherence (aRR 0.58; 95% CI 0.46–0.73; Table 2). In contrast to the model of WCC adherence in the first year, low birth weight and complex chronic conditions were significantly associated with increased WCC adherence (Table 2).

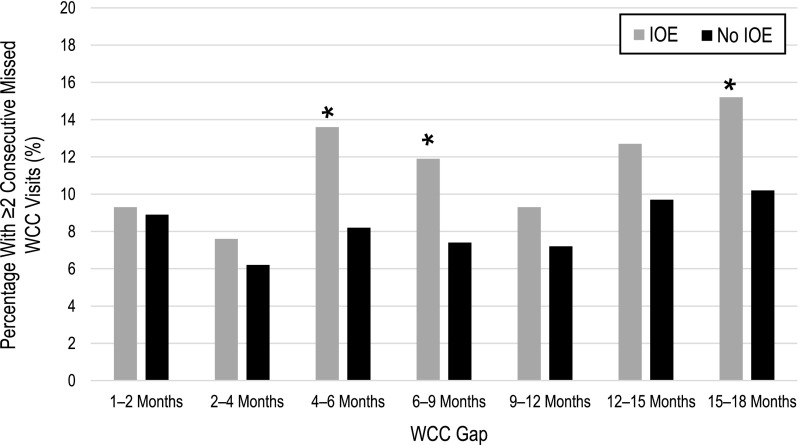

Gaps in WCC

As shown in Fig 1, 42.8% of children with IOE, versus 27.8% of children who were not exposed, had at least 1 WCC gap during the first 2 years (χ2 P < .001). Gaps in WCC most commonly occurred during the 15- to 18-month period (27.3% of the entire cohort), with significant differences between children with IOE and children who were not exposed at 4 to 6, 6 to 9, and 15 to 18 months (see Fig 3). In the multivariable analysis, IOE was associated with an increased likelihood of ≥1 WCC gap during the first 2 years (aRR 1.43; 95% CI 1.20–1.71, Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Gaps in WCC visits over time. Gray bars represent children with IOE. Black bars represent children without IOE. The y-axis represents the percentage with ≥2 consecutive missing WCC visits during each age interval, shown on the x-axis. * P < .05.

TABLE 3.

aRRs for ≥1 WCC Gap Over the First 2 Years of Life

| ≥1 WCC Gap Over the First 2 y, aRR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|

| IOE | 1.43 (1.20–1.71)* |

| Child race | |

| White | Reference |

| African American | 1.36 (1.18–1.56)* |

| Asian American | 1.24 (1.04–1.48)* |

| Other | 1.26 (1.09–1.46)* |

| Unknown | 0.93 (0.69–1.26) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | Reference |

| Hispanic | 0.84 (0.72–0.98)* |

| Unknown | 1.08 (0.84–1.39) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | Reference |

| Medicaid | 2.00 (1.58–2.53)* |

| Other or unknown | 1.53 (0.90–2.63) |

| Low birth wt <2500 g | 0.90 (0.81– <1.00)* |

| Complex chronic condition | 0.82 (0.75–0.90)* |

| Child sex | |

| Female | Reference |

| Male | 0.97 (0.91–1.02) |

| Area-level povertyb | 1.02 (1.01–1.02)* |

| Metropolitan residence | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) |

Generalized linear models with a log link and Poisson distribution.

Adjusted for all variables listed in the table, year of birth as a fixed effect, and clustering by practice by using robust variance estimation.

The coefficient represents a change in the relative risk per 1% increase.

P < .05.

Secondary Outcomes

As shown in Table 1, the median number of nonroutine visits was lower among children with IOE, and the percentage of children with on-time immunizations was ∼85% in both groups. The percentage with lead screening was higher among children with IOE (62% vs 53% of children who were not exposed). However, in the multivariable regression, there was no significant difference in these secondary outcomes on the basis of IOE status (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Secondary Outcomes, Adjusted Incident Rate Ratios, and aRRs

| IOE, aIRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Nonroutine primary care visits by age 2 y | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| On-time immunization status by age 2 y | 1.00 (0.95–1.05)a |

| Lead screening at age 1 y | 1.13 (0.99–1.28)a |

The multivariable negative binomial regression was adjusted for race, ethnicity, insurance, low birth weight status, complex chronic condition, sex, area-level poverty, metropolitan residence, and year of birth; clustering by practice was adjusted by using robust variance estimation. aIRR, adjusted incident rate ratio.

The multivariable generalized linear regression with a log link and Poisson distribution was adjusted for race, ethnicity, insurance, low birth wt status, complex chronic condition, sex, area-level poverty, metropolitan residence, and year of birth; clustering by practice was adjusted by using robust variance estimation.

Discussion

Among children <2 years of age, IOE was associated with decreased WCC adherence. Other child characteristics, such as low birth weight and complex chronic conditions, were associated with a neutral or negative effect on WCC adherence in the first year, potentially because of prolonged birth hospitalization or other competing acute care needs. However, in the second year, these characteristics were associated with increased WCC adherence, suggesting a protective effect against delays in care after early infancy. Conversely, the association between IOE and decreased WCC adherence was persistent over time. Our findings suggest that children with IOE are often “catching up” on WCC components, such as immunizations and lead screening, during nonroutine visits when their families seek care for more urgent conditions. Findings from this birth cohort from areas of the United States that have been significantly impacted by the opioid crisis provide new information regarding opportunities to improve preventive care for this population.35

For children affected by IOE, WCC visits are an important opportunity for primary care providers to address parental knowledge gaps, assess illness and injury risk, and evaluate child growth and development.4,6,36–38 These opportunities include surveillance and management of ongoing opioid withdrawal symptoms such as feeding difficulty, fussiness, and sleeplessness.39 Tailored discussions about opioid use while breastfeeding may play an important role.40 Other key topics for children with IOE include barriers to implementing safe sleep precautions, screening for strabismus and other visual disturbances, and, when exposed, testing for hepatitis C seroconversion.41–44 Among mothers with OUD, previous research has demonstrated low responsiveness to child cues, heightened tendency toward physical provocation, low ability to promote child learning, and limited understanding of basic development.45–48 WCC visits are a time to review motor and cognitive developmental expectations, encourage positive parenting strategies that optimize development, and connect families to early intervention services (including hearing and vision supports and speech, physical, and occupational therapy). Perhaps most importantly, WCC visits are an opportunity to assess parenting stress, coping skills, and quality of parent-child interaction and to refer to other community resources as needed.45,46,49 The benefits of such WCC services for young children have been previously described and extend beyond immunizations or other procedures that could be added on during a nonroutine visit.12,50

There is limited research on WCC adherence among children impacted by the opioid crisis.3,19 One recent retrospective study using a national insurance database revealed higher rates of all health care use (admissions, ED visits, and outpatient visits) in this population, with an overall lower proportion of care attributed to WCC visits.51 Our findings are also consistent with previous research revealing socioeconomic disparities in WCC adherence.27 Some of the key drivers hypothesized to impact WCC adherence include transportation issues, time constraints, family crisis events, and low perceived value of primary care.26,52 Mothers with OUD may also encounter challenges such as stigmatization and discrimination, legal and child custody concerns, and mental health issues.4,53 Furthermore, mothers with OUD are often burdened by a significant history of trauma, which is associated with lower satisfaction with and more negative attitudes toward parenting.47,54,55

Given these challenges, increasing WCC visits for this population may require changes to current models of care that increase perceived value for families, maternal empowerment, and trust in the health care system. Research from 1 maternal substance use treatment facility suggests that less than half of mothers feel their child’s pediatrician spends sufficient time with their child, and less than one-third feel they were asked about their viewpoints as a mother.56 One approach to address these concerns may be group-based WCC visits, which would afford more provider time, peer-to-peer interaction, and in-depth discussion.57–59 Previous research of a group-based mindful parenting intervention for this population demonstrated promising results in improving maternal stress and parenting.60,61 Patient-centered medical homes may improve WCC adherence through better patient outreach, care coordination, and provider continuity.62 Home visiting programs have also shown potential to increase WCC adherence among low-income families.63 Further research is needed to determine the impact these approaches may have in reducing stigma, increasing WCC engagement, and ultimately improving outcomes for children affected by IOE.

Although strengths of this study include a large recent study cohort spanning multiple states and the inclusion of both publicly and privately insured children, there are several limitations. First, we relied on billing codes for ascertainment of opioid exposure, which may lead to misclassification bias. We anticipated some underestimation of IOE on the basis of variation in maternal drug testing as well as physician documentation of known exposure in the pediatric electronic medical record. In 1 population-based cohort study with universal maternal urine drug testing at delivery, the reported IOE rate was slightly higher than that in our sample.64 As reflected in the high rate of NAS (80%) among those in our cohort with IOE, undercoding of IOE is more likely to occur for children not requiring treatment of NAS. These codes also provide limited insight into the type of opioid exposure, severity of NAS if diagnosed, or disposition of the child into maternal custody versus foster or kinship care. Furthermore, we lacked information on other known maternal predictors such as health literacy and social support, education level, adherence to prenatal care, marital status, and employment. However, we hypothesize that many of these factors are colinear with maternal substance use during pregnancy, and so although we could not discern the independent effects of each of these per se, the diagnosis of IOE is sufficient to serve as a marker of high-risk status for children in a pediatric office setting. We also lacked data from outside the primary care network; therefore, it is possible we underestimated WCC adherence among families who transferred care elsewhere. To minimize this, we used a conservative approach of restricting the analysis to infants with at least 1 visit within the network during the second year of life. When this restriction is removed, the negative effect sizes for IOE are slightly increased. This suggests that families of infants affected by IOE may be more likely to relocate their care. Finally, in this study, we did not evaluate adverse outcomes that may have resulted from decreased WCC adherence. Future work may focus on the impact of improved WCC adherence on salient outcomes for this population (eg, hospitalizations, subspecialty referrals, infant sleep safety, and parental approaches to discipline).

Conclusions

Children with IOE are less likely to adhere to WCC as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Use of nonroutine primary care is similar to that of children who were not exposed, as are rates of on-time immunization and lead screening. Given the growing awareness of the child health, safety, and developmental risks associated with maternal OUD, further research may focus on identifying and implementing health system interventions to promote the engagement of this population in preventive care to support their complex medical and psychosocial needs.

Glossary

- aRR

adjusted relative risk

- CI

confidence interval

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IOE

intrauterine opioid exposure

- NAS

neonatal abstinence syndrome

- OUD

opioid use disorder

- SNOMED-CT

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terminology

- WCC

well-child care

Footnotes

Dr Goyal conceptualized and designed this study, oversaw all aspects of the data collection and analysis, and drafted and critically revised the manuscript; Drs Rohde and Short contributed to the study design, assisted in interpretation of findings, edited the manuscript, and provided critical revisions for important scientific content; Dr Patrick contributed to the study design, assisted in interpretation of findings, and critically revised the manuscript for important scientific content; Dr Abatemarco supervised the study design and analysis and critically revised the manuscript for important scientific content; Dr Chung supervised the study design and analysis, assisted in interpretation of findings, edited the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important scientific content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by an Institutional Development Award from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant U54-GM104941 (principal investigator: Binder-Macleod). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS acting secretary declares public health emergency to address national opioid crisis. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretary-declares-public-health-emergency-address-national-opioid-crisis.html. Accessed October 10, 2018

- 2.Winkelman TNA, Villapiano N, Kozhimannil KB, Davis MM, Patrick SW. Incidence and costs of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants with Medicaid: 2004-2014. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pryor JR, Maalouf FI, Krans EE, Schumacher RE, Cooper WO, Patrick SW. The opioid epidemic and neonatal abstinence syndrome in the USA: a review of the continuum of care. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(2):F183–F187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spehr MK, Coddington J, Ahmed AH, Jones E. Parental opioid abuse: barriers to care, policy, and implications for primary care pediatric providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(6):695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maguire DJ, Taylor S, Armstrong K, et al. . Long-term outcomes of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal Netw. 2016;35(5):277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kocherlakota P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/2/e547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guevara JP, Gerdes M, Localio R, et al. . Effectiveness of developmental screening in an urban setting. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn AL, Mogilner LN, Dreyer BP, et al. . The impact of a clinic-based literacy intervention on language development in inner-city preschool children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson CS, Higman SM, Sia C, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, Duggan AK. Medical homes for at-risk children: parental reports of clinician-parent relationships, anticipatory guidance, and behavior changes. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pease A, Ingram J, Blair PS, Fleming PJ. Factors influencing maternal decision-making for the infant sleep environment in families at higher risk of SIDS: a qualitative study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1):e000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regalado M, Halfon N. Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years: review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(12):1311–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Grossman DC, Solomon C, Tseng CW. Well-child care visits and risk of ambulatory care-sensitive hospitalizations. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(5):354–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittard WB III, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment and infant health outcomes in Medicaid-insured infants in South Carolina. J Pediatr. 2007;151(4):414–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittard WB III, Hulsey TC, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. School readiness among children insured by Medicaid, South Carolina. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gressler LE, Shah S, Shaya FT. Association of criminal statutes for opioid use disorder with prevalence and treatment among pregnant women with commercial insurance in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleveland LM, Bonugli R. Experiences of mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(3):318–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleveland LM, Gill SL. “Try not to judge”: mothers of substance exposed infants. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2013;38(4):200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung EK, Brumbley M, Hand D, et al. . Receipt of prenatal care and well-child care among drug-dependent women and their young children In: Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; May 6–9, 2017; San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 20.PEDSnet. PEDSnet data quality program. Available at: https://pedsnet.org/data/data-quality/. Accessed March 1, 2019

- 21.Corr TE, Hollenbeak CS. The economic burden of neonatal abstinence syndrome in the United States. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1590–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall ES, Isemann BT, Wexelblatt SL, et al. . A cohort comparison of buprenorphine versus methadone treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr. 2016;170:39–44.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagan JF. Jr, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kang Y. Vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(40):1123–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal NK, Folger AT, Sucharew HJ, et al. . Primary care and home visiting utilization patterns among at-risk infants. J Pediatr. 2018;198:240–246.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donnell HC, Trachtman RA, Islam S, Racine AD. Factors associated with timing of first outpatient visit after newborn hospital discharge. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(1):77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf ER, Hochheimer CJ, Sabo RT, et al. . Gaps in well-child care attendance among primary care clinics serving low-income families. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20174019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Census Bureau 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=CF. Accessed November 27, 2019

- 30.Jones MN, Brown CM, Widener MJ, Sucharew HJ, Beck AF. Area-level socioeconomic factors are associated with noncompletion of pediatric preventive services. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(3):143–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural-urban commuting area codes. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/. Accessed January 15, 2018

- 32.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall A, Altman DG, Royston P, Holder RL. Comparison of techniques for handling missing covariate data within prognostic modelling studies: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merhar SL, McAllister JM, Wedig-Stevie KE, Klein AC, Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter BB. Retrospective review of neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Perinatol. 2018;38(5):587–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nygaard E, Moe V, Slinning K, Walhovd KB. Longitudinal cognitive development of children born to mothers with opioid and polysubstance use. Pediatr Res. 2015;78(3):330–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGlone L, Mactier H. Infants of opioid-dependent mothers: neurodevelopment at six months. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91(1):19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hudak ML, Tan RC; Committee on Drugs; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics . Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/2/e540 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(3):135–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiteri Cornish K, Hrabovsky M, Scott NW, Myerscough E, Reddy AR. The short- and long-term effects on the visual system of children following exposure to maternal substance misuse in pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(1):190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill AC, Oei J, Lewis NL, Younan N, Kennedy I, Lui K. Strabismus in infants of opiate-dependent mothers. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(3):379–385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Committee on Infectious Diseases American Academy of Pediatrics Hepatitis C In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 30th ed Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:423–430 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman HJ, Damus K, Hillman L, Krongrad E. Risk factors for SIDS. Results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development SIDS Cooperative Epidemiological Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;533:13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnard M, McKeganey N. The impact of parental problem drug use on children: what is the problem and what can be done to help? Addiction. 2004;99(5):552–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burns KA, Chethik L, Burns WJ, Clark R. The early relationship of drug abusing mothers and their infants: an assessment at eight to twelve months of age. J Clin Psychol. 1997;53(3):279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizzo RA, Neumann AM, King SO, Hoey RF, Finnell DS, Blondell RD. Parenting and concerns of pregnant women in buprenorphine treatment. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2014;39(5):319–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suchman NE, Luthar SS. Maternal addiction, child maladjustment and socio-demographic risks: implications for parenting behaviors. Addiction. 2000;95(9):1417–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGlade A, Ware R, Crawford M. Child protection outcomes for infants of substance-using mothers: a matched-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiks AG, Hunter KF, Localio AR, Grundmeier RW, Alessandrini EA. Impact of immunization at sick visits on well-child care. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):898–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu G, Kong L, Leslie DL, Corr TE. A longitudinal healthcare use profile of children with a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr. 2019;204:111–117.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coker TR, Chung PJ, Cowgill BO, Chen L, Rodriguez MA. Low-income parents’ views on the redesign of well-child care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):194–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutter MB, Gopman S, Leeman L. Patient-centered care to address barriers for pregnant women with opioid dependence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44(1):95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conroy E, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, Nelson EC. Child maltreatment as a risk factor for opioid dependence: comparison of family characteristics and type and severity of child maltreatment with a matched control group. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(6):343–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sansone RA, Whitecar P, Wiederman MW. The prevalence of childhood trauma among those seeking buprenorphine treatment. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(1):64–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Short VL, Goyal NK, Chung EK, Hand DJ, Abatemarco DJ. Perceptions of pediatric primary care among mothers in treatment for opioid use disorder. J Community Health. 2019;44(6):1127–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeLago C, Dickens B, Phipps E, Paoletti A, Kazmierczak M, Irigoyen M. Qualitative evaluation of individual and group well-child care. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):516–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnston JC, McNeil D, van der Lee G, MacLeod C, Uyanwune Y, Hill K. Piloting CenteringParenting in two Alberta public health well-child clinics. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(3):229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mittal P. Centering parenting: pilot implementation of a group model for teaching family medicine residents well-child care. Perm J. 2011;15(4):40–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gannon M, Mackenzie M, Kaltenbach K, Abatemarco D. Impact of mindfulness-based parenting on women in treatment for opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2017;11(5):368–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Short VL, Gannon M, Weingarten W, Kaltenbach K, LaNoue M, Abatemarco DJ. Reducing stress among mothers in drug treatment: a description of a mindfulness based parenting intervention. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(6):1377–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zutshi A, Peikes D, Smith K, et al. . The Medical Home: What Do We Know, What Do We Need to Know? A Review of the Earliest Evidence on the Effectiveness of the Patient-Centered Medical Home Model. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. Available at: https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/medical-home-what-do-we-know-what-do-we-need-know-review-earliest-evidence-effectiveness-of-the-patient-centered-medical-home-model. Accessed January 16, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goyal NK, Ammerman RT, Massie JA, Clark M, Van Ginkel JB. Using quality improvement to promote implementation and increase well child visits in home visiting. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;53:108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hall ES, Wexelblatt SL, Greenberg JM. Surveillance of intrauterine opioid exposures using electronic health records. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(6):486–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]