Abstract

Neurodegenerative disease is characterized by the progressive deterioration of neuronal function caused by the degeneration of synapses, axons, and ultimately the death of nerve cells. An increased understanding of the mechanisms underlying altered cellular homeostasis and neurodegeneration is critical to the development of effective treatments for disease. Here, we review what is known about neuronal cell death and how it relates to our understanding of neurodegenerative disease pathology. First, we discuss prominent molecular signaling pathways that drive neuronal loss, and highlight the upstream cell biology underlying their activation. We then address how neuronal death may occur during disease in response to neuron intrinsic and extrinsic stressors. An improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying neuronal dysfunction and cell death will open up avenues for clinical intervention in a field lacking disease-modifying treatments.

Unlike most cells in the body, which readily turn over to maintain tissue homeostasis, postmitotic neurons harbor minimal regenerative capacity and must survive for the lifetime of an organism to ensure nervous system function. Although neuronal cell death is essential to promote proper nervous system development (Yamaguchi and Miura 2015), neuronal loss in the adult inevitably leads to functional decline and underlies disease progression in neurodegenerative indications ranging from acute insults such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke, to chronic conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). These and other chronic neurodegenerative diseases affect millions of individuals worldwide, with no treatments available that are able to slow the rate of decline.

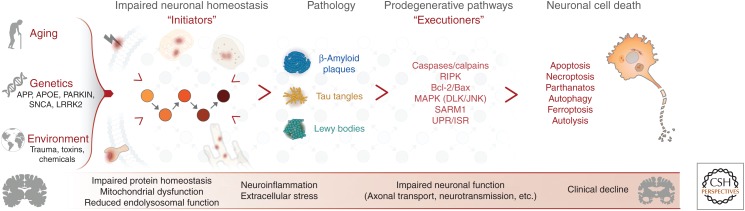

Human neuropathological studies using postmortem AD, PD, and ALS tissue have identified stereotyped patterns of neuronal degeneration that develop sequentially at different brain and spinal cord regions and match the clinical severity of disease (Braak and Braak 1991; Braak et al. 2003; Brettschneider et al. 2015). This loss of neurons is often accompanied by additional pathologies, including impaired axonal transport and synaptic function, mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction, oxidative stress, microglial activation, and protein aggregates that can be visualized in diseased neurons. A combination of aging, genetic risk, and environmental factors is thought to disrupt neuronal homeostasis and contribute to these pathologies—the “initiators” of neuronal degeneration. The subsequent engagement of known cell death pathways in neurons—the “executioners” of cell death—has been described across multiple neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting that common molecular signaling events may at least in part underlie disease-associated functional decline.

Although our understanding of the genetics and pathology of neurodegenerative disease has improved rapidly in recent years, the biology of neurodegeneration is complex, and there remains an unsatisfying disconnect between the initiators that can be observed as a component of disease pathology and the subsequent activation of neuronal cell death executioners. Determining which cell death pathways are relevant during disease progression and the mechanisms by which they are activated remains a key question in the field, and unraveling these mechanisms has the potential to drive the development of a new generation of targeted therapeutics that modify neurodegenerative disease progression.

PATHWAYS REGULATING NEURONAL CELL DEATH

Much of what we know about the executioners of cell death in neurons comes from studies of acute neuronal injury or neuronal development. Here, we discuss several of these pathways and highlight what is known about their role in neuronal degeneration.

Evidence for Apoptosis, Necroptosis, and Other Death Pathways in Neurons

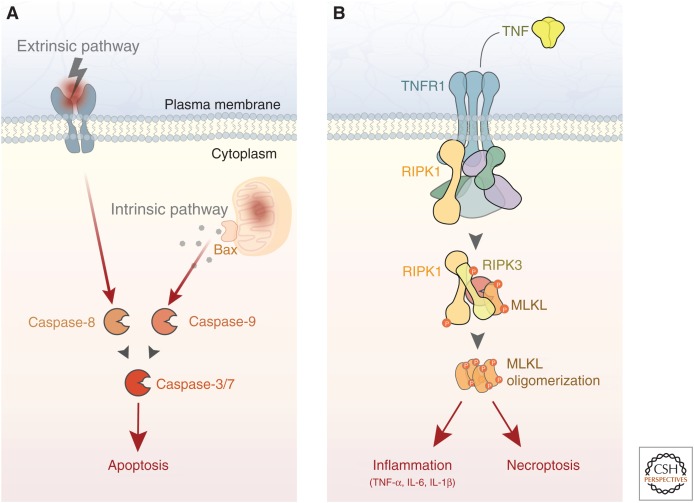

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death characterized by DNA fragmentation, degradation of cytoskeletal and nuclear proteins, and eventual phagocytosis by immune cells. It is executed by the caspase family of proteins, which make up a proteolytic cascade that ultimately results in cell death (Elmore 2007). Neuronal apoptosis occurs during development of the central nervous system to remove excess neurons, and can be observed in adult neurons following acute insults ranging from excitotoxicity to mechanical injury (Yuan and Yankner 2000). Apoptosis can be initiated downstream from death receptor activation via caspase-8 (extrinsic pathway), but more commonly occurs following mitochondrial damage via caspase-9 (intrinsic pathway) (Fig. 1A). These pathways converge on caspase-3, which is required for neuronal apoptosis (Kuida et al. 1996). Caspase-7, another executioner caspase important for apoptosis in other cell types, may also contribute but appears to play a less essential role in neurons (Zhang et al. 2000; Slee et al. 2001). Consistent with these findings, mice lacking caspase-3 expression display excess neurons at birth and reduced apoptosis in a number of contexts (Kuida et al. 1996; Leonard et al. 2002).

Figure 1.

Apoptosis and necroptosis are executioners of neuronal cell death. (A) Neuronal apoptosis is executed by the caspase family of proteases. In the extrinsic pathway, death receptor engagement by secreted or membrane-bound death ligands leads to caspase-8 activation. In the intrinsic pathway, mitochondrial damage activates caspase-9 through back-mediated release of mitochondrial proteins. The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways converge on caspase-3 (and to a lesser extent in neurons, caspase-7), ultimately resulting in cell death. (B) Neuronal necroptosis is induced by several stimuli, including TNF signaling. Downstream from receptor activation, RIPK3 phosphorylates MLKL, leading to plasma membrane permeabilization and cell death. In addition to necroptosis, RIPK activity also mediates a cell-autonomous inflammation response that exacerbates neurodegeneration. TNF, Tumor necrosis factor; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1; RIPK, receptor-interacting kinase protein; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; IL, interleukin.

Mitochondrial damage-mediated apoptosis in neurons requires the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein Bax, which forms channels in the mitochondrial membrane that promote the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria and subsequent activation of caspase-9 (Kroemer et al. 2007). This pathway functions to regulate neuronal apoptosis even in scenarios in which the primary insult does not involve mitochondrial damage, such as trophic factor withdrawal (Kristiansen and Ham 2014), suggesting that mitochondrial permeabilization broadly contributes to neuronal apoptosis. Neurons lacking Bax expression are strongly protected from degeneration and do not display caspase activation even after prolonged insult (Deckwerth et al. 1996; Vila et al. 2001; Libby et al. 2005).

Necroptosis is a more recently discovered form of programmed cell death that is caspase-independent and harbors cellular characteristics of necrosis (Vanden Berghe et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017). Various stimuli can induce necroptosis, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, as well as viral infection. Downstream from TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), a complex containing receptor-interacting kinase proteins 1 and 3 (RIPK1/3) phosphorylates mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) to induce its oligomerization (Fig. 1B). Other pathways can lead to MLKL phosphorylation in a RIPK1-independent fashion (Silke et al. 2015). Phosphorylated MLKL subsequently forms pores in the plasma membrane, leading to neuronal death and release of proinflammatory factors from the cell. Several reports indicate that RIPK signaling contributes to neuronal loss in various in vivo models (Ito et al. 2016; Caccamo et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017; Iannielli et al. 2018). In some studies, RIPK1 has been shown to act directly in neurons to regulate degeneration (Re et al. 2014; Iannielli et al. 2018; Arrazola et al. 2019), whereas others suggest that RIPK1 regulates necroptosis in other central nervous system cell types (Ofengeim et al. 2015; Ito et al. 2016). Interestingly, RIPK1 has also been shown to mediate a cell-autonomous proinflammatory response, rather than cell death, in peripheral immune cell populations and microglia (Najjar et al. 2016; Ofengeim et al. 2017; Yuan et al. 2019). Taken together, these results suggest that RIPK1 function may contribute both directly and indirectly to neuronal degeneration.

In addition to apoptosis and necroptosis, several other cell death pathways have been observed in neurons, including ferroptosis (iron-dependent necrosis), autolysis (lysosomal cell death), and autophagy (death by “self-eating”), among others. Complicating the picture of neuronal cell death is the observation that there is significant cross talk between several of these pathways, a topic that has been reviewed previously (Fricker et al. 2018).

The Neuronal Stress Response: A Master Regulator of Cell Death

Cell death in neurons often occurs following a stress response via signals such as the c-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway. The JNK signaling pathway has been extensively characterized in neurons, and is required for a variety of functions, including mediating the response to neuronal injury (Borsello and Forloni 2007; Tedeschi and Bradke 2013; Yarza et al. 2015; Siu et al. 2018). The mixed lineage dual leucine zipper kinase (DLK) is an essential upstream regulator of stress-dependent JNK signaling in neurons (Holzman et al. 1994; Ghosh et al. 2011), and is activated in response to neurotrophic growth factors, neuronal and axonal injury, oxidative stress, and misfolded proteins, among other factors (Tedeschi and Bradke 2013; Simon and Watkins 2018; Siu et al. 2018). DLK-dependent phosphorylation of JNK results in its translocation to the nucleus and phosphorylation of transcription factors including c-Jun, which induce a transcriptional stress response culminating in apoptosis in the central nervous system (Yang et al. 1997; Behrens et al. 1999; Fernandes et al. 2012). DLK appears to act as a central node that regulates neuronal degeneration during development, following neuronal injury, and in chronic neurodegenerative disease. Neurons lacking DLK signaling fail to mount a normal transcriptional injury response, display attenuated caspase activation, and are strongly protected from degeneration following insult (Pozniak et al. 2013; Watkins et al. 2013; Patel et al. 2015; Le Pichon et al. 2017; Siu et al. 2018).

DLK activity can also impact protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)-dependent phosphorylation of the translation eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) in neurons following acute injury (Larhammar et al. 2017). PERK signaling is a component of the unfolded protein response (UPR) as outlined below, and DLK-dependent activation of this pathway has been shown to contribute to neuronal degeneration. These results suggest that DLK signaling acts broadly downstream from neuronal insults through impacting multiple stress response pathways. Recent reviews provide more information regarding how cellular context and other signaling pathways impact the disparate outcomes downstream from DLK signaling (Tedeschi and Bradke 2013; Simon and Watkins 2018; Siu et al. 2018).

Axon Degeneration: Programmed Destruction of Neuronal Processes

Axon degeneration, characterized by the elimination of axonal processes and loss of neuronal connectivity, is an early clinical feature of most neurodegenerative disorders, ranging from acute insults to chronic neurodegenerative disease (Burke and O'Malley 2013; Johnson et al. 2013; Benarroch 2015; Cashman and Höke 2015; Tagliaferro and Burke 2016; Kim et al. 2018). Recent data have shown that axon degeneration is an active process, dependent on both local axonal signaling events and transcriptional regulation within the neuronal cell body. Furthermore, it can occur in the absence of, or in conjunction with, neuronal apoptosis and is thought to contribute to functional decline in many disease indications (Simon et al. 2016; Simon and Watkins 2018).

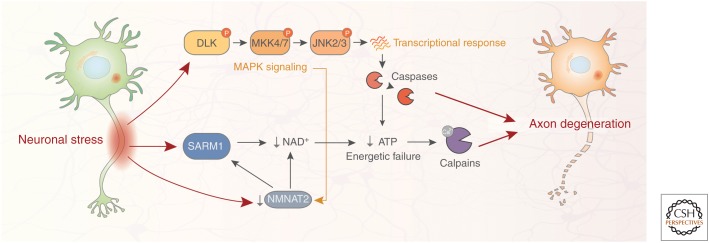

Multiple pathways have been shown to contribute to axon degeneration, with the mechanism being dependent on the context examined (Fig. 2; Gerdts et al. 2016). In many experimental paradigms, including trophic factor withdrawal and addition of chemotherapeutic compounds known to cause neuropathy, the DLK/JNK signaling pathway acts as a central regulator of axon degeneration (Miller et al. 2009). DLK-dependent degeneration of axons appears to be governed by similar pathways to those that regulate neuronal cell death and requires the activation of caspase signaling (Ghosh et al. 2011).

Figure 2.

Neuronal signaling pathways regulating axon degeneration. Axon degeneration is an active process involving several signaling pathways engaged by diverse neuronal stressors, both extracellular (e.g., axonal injury, toxins/chemotherapeutic agents) and intracellular (e.g., impaired protein homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction). Axonal damage results in both depletion of the protective axonal maintenance factor NMNAT2 and activation of SARM1, leading to a reduction of NAD+ levels, depletion of axonal ATP, and activation of proteolytic calpains. Neuronal stress also results in phosphorylation of DLK, a master kinase of the neuronal stress response that regulates both axon degeneration and neuronal apoptosis. DLK activation leads to phosphorylation of downstream kinases MKK4/7 and JNK2/3, and ultimately induces a prodegenerative caspase signaling cascade that activates calpains. There is cross talk between the SARM1 and DLK pathways; DLK signaling promotes NMNAT2 turnover, thereby enhancing SARM1-mediated axon degeneration. SARM1, sterile α and TIR motif-containing protein 1; NMNAT2, nicotinamide nucleotide adenylyltransferase 2; JNK, c-Jun amino-terminal kinase; DLK, dual leucine zipper kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase.

In Wallerian degeneration paradigms, in which the axon is lesioned and disconnected from the cell body, sterile α and TIR motif-containing protein 1 (SARM1) is necessary and sufficient for axon degeneration, and axons of SARM1 knockout mice are protected in several in vivo neurodegeneration models (Osterloh et al. 2012; Gerdts et al. 2013, 2016; Henninger et al. 2016; Turkiew et al. 2017; Ziogas and Koliatsos 2018). Upon axonal damage or stress, SARM1, which harbors intrinsic NADase activity, becomes activated and hydrolyses NAD, resulting in reduction of axonal ATP levels and ultimately degradation of neurofilaments and axonal fragmentation via the calpain family of proteases (Gerdts et al. 2013, 2016). Axonal injury also decreases the levels of the NAD biosynthetic enzyme NMNAT2, which normally acts in part to inhibit SARM1 activity (Gilley et al. 2015). This reduction in NMNAT2 both decreases NAD levels and increases SARM1 signaling, thereby exacerbating axon degeneration. Furthermore, the DLK signaling pathway has been found to promote degradation of NMNAT2, thus promoting SARM1-mediated axon degeneration, although the functional contribution of DLK signaling to Wallerian degeneration appears relatively minor (Xiong et al. 2012; Summers et al. 2016; Walker et al. 2017). Interestingly, both trophic factor withdrawal and Wallerian degeneration pathways culminate in the activation of the calpains. Accordingly, inhibition of calpains either with small molecules or via overexpression of the calpain inhibitor calpastatin is sufficient to protect axons from degeneration (Yang et al. 2013). Additional signaling mechanisms that contribute to axon degeneration have been reviewed elsewhere (Rishal and Fainzilber 2014; Simon and Watkins 2018).

MECHANISMS OF NEURONAL CELL DEATH IN DISEASE

It is thought that several diverse stressors can initiate intracellular events in neurons that lead to neuronal cell death in chronic neurodegenerative disease, often in parallel. These initiators include toxic aggregation of misfolded proteins, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, defects in the endolysosomal system, and oxidative stress (Dawson and Dawson 2017; Hetz and Saxena 2017). Here, we review how several prevalent initiators impact neuronal death in disease, with an emphasis on the pathologies observed in AD and PD.

Protein Homeostasis

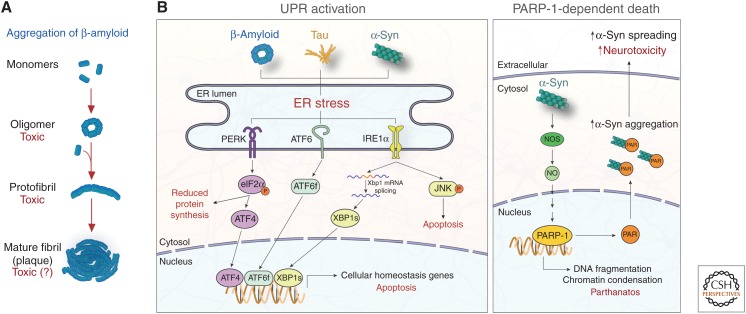

A common pathological trait of neurodegenerative disorders, including AD and PD, is the aggregation of toxic misfolded proteins that are associated with synaptic dysfunction and degeneration of neuronal populations. In AD, this consists of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau, while PD pathology is characterized by intracellular inclusions of α-synuclein (α-syn), termed Lewy bodies (Ross and Poirier 2004; Smith and Mallucci 2016; Hetz and Saxena 2017). Although the precise mechanisms that trigger the conversion from normal to misfolded protein are unresolved, Aβ, tau, and α-syn comprise a portion of the “metastable proteome,” a set of proteins whose cellular concentrations are high relative to their intrinsic solubility and are therefore biased to misfolding (Ciryam et al. 2013, 2016; Kundra et al. 2017). This bias increases with aging, the greatest risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. The biochemical properties of misfolded proteins facilitate the recruitment of normal proteins into growing toxic oligomers, accelerating the process of aggregation (Fig. 3A; Jarrett and Lansbury 1993; Meisl et al. 2017). Furthermore, in preclinical models, misfolded tau and α-syn have been shown to propagate from cell to cell (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010; Kfoury et al. 2012; Brettschneider et al. 2015; Soto and Pritzkow 2018). Initially controversial, cumulative evidence suggests that aggregates spread via neuronal synapses—similar to prions—allowing misfolded protein pathology to spread throughout the brain in a connectome-dependent fashion that matches disease progression (Clavaguera et al. 2009; Desplats et al. 2009; Luk et al. 2012; Iba et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2016).

Figure 3.

Impaired protein homeostasis is an initiator of neuronal cell death. (A) Aggregation of misfolded proteins, including β-amyloid, is a common pathological trait of chronic neurodegeneration disease. Monomeric proteins misfold and aggregate into toxic oligomers that recruit normal proteins into growing protofibrils, eventually forming mature plaques. Recent evidence suggests that oligomers are particularly toxic in disease, a topic of ongoing debate (Verma et al. 2015). (B, left) Protein aggregates cause endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and activate the UPR, inducing PERK, ATF6, and IRE1α signaling cascades. PERK activation leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α and subsequent reduction of protein synthesis and expression of the transcription factor ATF4. ATF6 and IRE1α signaling lead to the expression of the transcription factors ATF6f and XBP1s, respectively. These transcription factors induce cellular homeostasis gene expression, but can also drive expression of proapoptotic genes under prolonged ER stress. JNK signaling is also activated downstream from IRE1α, promoting apoptosis. (B, right) In PD, α-syn fibrils active NOS, leading to PARP-1 activation and death of dopaminergic neurons via parthanatos. PAR produced by PARP-1 activation binds α-syn, increasing its aggregation, cell-to-cell spreading, and subsequent neurotoxicity. UPR, Unfolded protein response; PERK, PKR-like ER kinase; ATF4/6, activating transcription factor 4/6; IRE1α, inositol-requiring protein 1α; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1; JNK, c-Jun amino-terminal kinase; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; PARP-1, poly(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase-1.

The presence of pathology characterized by protein aggregates has led to the widely held hypothesis that protein misfolding plays a role in neurodegenerative cell death. But how do misfolded proteins kill neurons? It is possible that the formation of aggregates sequesters proteins from their endogenous localization and precludes them from performing their physiological functions required for neuronal survival. In the case of α-syn, which is normally found at the presynapse and promotes SNARE-complex assembly, evidence exists that this function may be disrupted in disease (Burre et al. 2010; Lashuel et al. 2013). Formation of α-syn aggregates in cultured neurons leads to decreased expression of other SNARE proteins, impairments in synaptic connectivity and transmission, and eventually neuronal death, arguing that the endogenous localization and function of α-syn is critical for synaptic signaling and neuronal survival (Volpicelli-Daley et al. 2011). However, no similar data supporting a sequestration hypothesis exists for tau. Indeed, reduction of endogenous tau levels in a human β-amyloid precursor protein AD mouse model both protects against excitotoxicity and abrogates behavioral deficits in these mice (Roberson et al. 2007), arguing that absence of normal tau function is not likely to underlie the neuronal dysfunction and ultimately cell death observed in AD.

A large body of evidence suggests that toxic gain-of-function, rather than loss of endogenous function, is the primary driver of neuronal cell death following aggregation of most disease-associated proteins. Under physiological conditions, proteins are folded into their native form in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with the help of cytosolic and resident ER chaperones, whereas misfolded proteins are targeted and trafficked to the autophagosome, proteasome, and lysosome for degradation (Hetz and Saxena 2017). This process of protein homeostasis, or “proteostasis,” governs protein production and is critical for overall neuronal health. The presence of misfolded proteins results in the activation of multiple stress response pathways including the UPR, which attempts to restore proteostasis through the up-regulation of ER chaperones, reduction of protein synthesis, and regulation of protein secretion and degradation. The UPR is mediated by three distinct branches that initiate unique signaling cascades upon ER stress: PERK, activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring protein 1α (IRE1α) (Fig. 3B; Walter and Ron 2011; Pavitt and Ron 2012). The PERK pathway leads to activation of eIF2α, resulting in the global shutdown of translation and expression of the transcription factor ATF4, which up-regulates genes that allow cells to respond to insult. However, during severe or sustained ER stress that is thought to occur in chronic neurodegenerative disease, the UPR pathways can shift toward proapoptotic signaling (Smith and Mallucci 2016; Hetz and Saxena 2017). For example, ATF4 induces expression of proapoptotic genes under severe stress conditions, including the Bcl-2 family members Puma and Bim (Galehdar et al. 2010; Li et al. 2014). Additionally, other arms of the UPR can also initiate proapoptotic signaling, such as the activation of JNK signaling triggered by IRE1α (Urano et al. 2000).

Several lines of evidence suggest that misfolded proteins promote the induction of ER stress and the UPR in chronic neurodegenerative disease. For example, in PD, misfolded α-syn accumulates in the ER lumen, where it interacts with and decreases the function of ER chaperones (Bellucci et al. 2011). In addition, α-syn causes ER stress by inhibiting the normal trafficking of proteins from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, causing molecular traffic jams that inhibit protein maturation (Credle et al. 2015). In AD, both Aβ and tau aggregates lead to ER stress through distinct mechanisms. Aβ oligomers that are internalized by neurons accumulate in the ER lumen and aberrantly open calcium channels, resulting in toxic increases in intracellular calcium levels (Demuro et al. 2010; Shtifman et al. 2010). Tau aggregates inhibit the ability of neurons to eliminate misfolded proteins by associating with and inhibiting molecular components of ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (Abisambra et al. 2013; Meier et al. 2015). Taken together, it is reasonable to conclude that protein misfolding in neurons results in prolonged ER stress through multiple mechanisms and may ultimately contribute to the induction of apoptotic cell death.

ER stress and the UPR are important mediators of neurotoxicity downstream from protein misfolding, yet the specific mechanisms leading to cell death downstream from protein aggregation are still poorly defined. A recent study shed light on this question by showing that α-syn aggregates activate the poly(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1)-dependent cell death pathway known as parthanatos in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3B) (Kam et al. 2018). Mechanistically, pathologic α-syn activates nitric oxide synthase, resulting in the activation of the PARP-1 enzyme by nitric oxide. PARP-1 activation subsequently leads to large-scale DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and ultimately cell death (Fatokun et al. 2014). Furthermore, PAR produced through PARP-1 activation binds to α-syn and promotes its aggregation, causing a positive feedback loop that exacerbates neuronal parthanatos. Although genetic and pharmacological inhibition of PARP-1 prevented neuronal cell death in vivo, blockers of necroptosis and autophagy had little effect, suggesting that parthanatos is a major driver of α-syn toxicity in the disease models used. Interestingly, caspase inhibitors had a partial protective effect on cell death in the same study, indicating that apoptosis also plays a role in neuronal death in PD.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Another initiator thought to contribute to cytotoxicity in disease is impaired mitochondrial function. Increasing evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction is a cause of neurodegeneration, rather than a consequence, and may contribute to disease pathology and neuronal loss in both AD and PD (Devi et al. 2008; Chinta et al. 2010; Swerdlow et al. 2010; Dawson and Dawson 2017). Early studies showing that apoptosis is induced in neurons following treatment with the mitochondrial toxins 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tertahydropyridine (MPTP) and rotenone provided the first evidence that mitochondrial damage may be a particularly relevant stressor in this cell type (Vila and Przedborski 2003). These discoveries were complemented by human genetic data showing that loss-of-function mutations in PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and Parkin, two proteins required for mitochondrial quality control, are associated with increased PD risk (Pickrell and Youle 2015). Studies using cultured neurons from PINK1 and Parkin knockout mice suggested that these proteins normally mediate the removal of damaged mitochondria from neuronal axons via mitophagy, a specialized form of autophagy (Ashrafi et al. 2014). PINK1 and Parkin also attenuate apoptosis under stress conditions by limiting Bax recruitment to the mitochondrial membrane (Johnson et al. 2012). Interestingly, PINK1 and Parkin knockout mouse models do not display obvious loss of dopaminergic neurons in vivo (Kitada et al. 2009), indicating that rodents may compensate for their loss through yet-unknown mechanisms. However, a recent study showed that these knockout mice display an activation of the innate immune system on mitochondrial stress (Sliter et al. 2018), suggesting that mitophagy regulated by PINK1 and Parkin may function to suppress neuroinflammation, another initiator of neuronal death discussed below.

There is a body of data linking mitochondrial damage to neuronal apoptosis, although a recent study showed that mitochondrial dysfunction can also result in necroptosis in dopaminergic neurons (Iannielli et al. 2018). Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons from PD patients with mutations in optic atrophy type 1 (OPA1), a resident mitochondria gene involved in mitochondrial fusion and respiratory efficiency (Patten et al. 2014), showed severe energetic deficits, mitochondrial fragmentation, and oxidative stress. Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of necroptosis via necrostatin-1 both improved the health of these iPSC-neurons and significantly protected against dopaminergic neuron death by MPTP in vivo, suggesting that necroptosis may play a role in neuronal cell death caused by mitochondrial damage. However, as necrostatin-1 also blocks RIPK1-dependent apoptosis in certain contexts (Vandenabeele et al. 2013), a role for apoptosis in the paradigms tested cannot be completely excluded.

Neuroinflammation

It has become increasingly clear that disease-related neurodegeneration is a multifaceted process involving multiple cell types in the brain. Emerging evidence implicates microglia, the resident innate immune cells of the brain, as major players promoting pathology in neurodegenerative disease, particularly in AD (Heneka et al. 2015; Hansen et al. 2018). Indeed, a large percentage of AD risk genes are highly (and in many cases specifically) expressed in microglia (Srinivasan et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016). Based on current understanding, microglia contribute to neuronal cell death through multiple mechanisms, including release of cytotoxic inflammatory cytokines and direct phagocytosis of damaged synapses and neurons.

Increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by microglia have been reported in disease models and brains of patients with AD and PD, suggesting that these factors may contribute to neuronal cell death (Griffin et al. 1989; Mogi et al. 1994; Zhou et al. 2016). In line with these observations, Aβ and α-syn aggregates have been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, a danger sensor of the innate immune system that drives production of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 (Codolo et al. 2013; Heneka et al. 2013; Voet et al. 2019). These cytokines in turn bind to their cognate receptors on neurons, initiating cytotoxic events such as aberrant calcium influx and activation of the JNK signaling pathway (Curran et al. 2003; Viviani et al. 2003; Allan et al. 2005). Similar to what was observed with α-syn mediated activation of parthanatos in neurons (Kam et al. 2018), NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia has been shown to propagate Aβ aggregation and spreading, creating a positive feedback loop that may exacerbate neuronal cell death (Venegas et al. 2017). Activated microglia can also produce additional cytotoxic species, including TNF-α, which has been shown to promote neuronal cell death through the potentiation of neural excitotoxicity, and the induction of neuronal apoptosis via signaling through neuronally expressed death receptors (Guadagno et al. 2013; Neniskyte et al. 2014; Olmos and Lladó 2014).

Another potential mechanism by which microglia contribute to neuronal cell death is the aberrant co-option of microglial phagocytic capacity. During normal development, microglia contribute to neural circuit refinement through the pruning of synapses (Schafer et al. 2012). This synaptic pruning by microglia relies on the classical complement pathway, a component of the innate immune system normally used to clear pathogens. Histological evidence shows that the complement pathway becomes reactivated in AD microglia, which may render them once again capable of engulfing synapses (Zanjani et al. 2005). Consistent with this idea, genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of molecular components of complement protects against neuron loss in several mouse models, arguing that microglia contribute to neuronal cell death via synapse phagocytosis (Fonseca et al. 2004; Hong et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2017; Dejanovic et al. 2018). Additional work showed that microglia are capable of directly phagocytosing neurons after Aβ stimulation, a process termed phagoptosis (Neniskyte et al. 2011). Phagoptosis occurs without the activation of apoptosis or necroptosis in the neurons being engulfed, suggesting that it is a primary executioner of cell death and not secondary to the activation of other death pathways.

Selective Vulnerability

During neurodegenerative disease progression, specific brain regions and neuronal subsets within those regions are more likely to experience cytotoxic events, a phenomenon termed “selective vulnerability” (Fu et al. 2018). In AD, the first neurons lost in disease include pyramidal neurons in the entorhinal cortex, followed by neuronal populations in the hippocampus, and eventually the neocortex. In PD, clinical motor phenotypes are primarily caused by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) region of the striatum, with neuronal loss in other regions such as the pedunculopontine nucleus and locus coeruleus also being reported. Why one set of neurons succumbs to disease pathology while neighboring cells remain healthy remains a perplexing question in the field, particularly in light of the fact that the proteins susceptible to aggregation, and other factors leading to neurodegeneration, are present throughout the brain.

Studies comparing vulnerable and spared neurons in disease have shed light onto intrinsic physiological differences between these populations that may underlie selective vulnerability (Greene et al. 2005; Liang et al. 2008; Freer et al. 2016). Expression profiling in mouse and human has shown that vulnerable neuronal populations in AD and PD express reduced levels of genes involved in both protein homeostasis and calcium buffering compared with spared populations, likely predisposing them to higher levels of protein misfolding and ER stress (Hof et al. 1993; Chung et al. 2005; Wang and Mattson 2014; Freer et al. 2016). The SNpc dopaminergic neurons impacted in PD also have abundant deletions in mitochondrial DNA compared with other dopaminergic neuron populations, which may lead to increased mitochondrial dysfunction (Bender et al. 2006).

In AD, excitatory neurons appear more vulnerable to cell death than inhibitory neurons, with cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain being particularly susceptible (Davies and Maloney 1976). Although early studies uncovered an association between deficits in excitatory neurotransmission and AD progression (Francis et al. 1999), a mechanistic understanding of how cell death pathways are more readily activated in excitatory neurons remains elusive. A recent study analyzing human single-cell RNA sequencing databases uncovered a tau protein homeostasis signature present in inhibitory but not excitatory neurons, and identified inhibitory neuron-enriched Bcl-2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) as a master regulator of tau accumulation (Fu et al. 2019). The diminished expression of BAG3 in excitatory neurons provides one of the first molecular links between selective vulnerability and toxic tau aggregation, an initiator of cell death. The identification of additional links will be facilitated by the expanding repertoire of single-cell sequencing techniques, as well as the advent of technologies that enable the differentiation of human iPSCs into various neuronal populations. Indeed, iPSCs from AD patients that have been differentiated into excitatory and inhibitory neuronal populations show differential susceptibility to tau and Aβ pathology (Muratore et al. 2017). Future studies have the opportunity to determine how distinct neuronal populations differentially respond to protein misfolding, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammatory insults, and investigate how these responses lead to activation of distinct cell death pathways.

LINKING THE INITIATORS AND EXECUTIONERS OF NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASE

Although several examples have been discussed in this review, there is relatively little data linking the initiator pathologies that have been observed in neurodegenerative disease to the executioner pathways known to mediate neuronal cell death. This stems in part from the fact that it is difficult to capture all aspects of a chronic neurodegenerative disease, such as AD or PD, in a single model. For instance, a number of the more prominent animal models for these disorders present with protein aggregate pathology (i.e., Aβ plaques or α-syn aggregates), but do not show appreciable cell death (Wirths and Bayer 2010).

To determine the relevance of executioner pathways in chronic neurodegenerative disease, researchers have looked for evidence of their activity in brains of human AD and PD patients. In the case of necroptosis, recent studies have found evidence of pathway activity in AD and other neurodegenerative indications (Ofengeim et al. 2015; Caccamo et al. 2017), although direct evidence of necrotic cell death has been more difficult to visualize. Similar studies have been conducted to identify apoptotic neurons with mixed results (Shimohama 2000; Venderova and Park 2012). Neurons undergoing apoptosis in the brains of AD and PD patients are relatively rare, although it is unclear whether this indicates that apoptosis is not a major driver of cell death or if this transient event is simply difficult to visualize in postmortem samples. In contrast, the activation of upstream stress response pathways is more readily visible in the brains of patients with chronic neurodegenerative disease. For instance, the presence UPR activation markers, particularly phosphorylated PERK and eIF2α, has been reported in the brains of AD, PD, and ALS patients (Chang et al. 2002; Hoozemans et al. 2007, 2009; Atkin et al. 2008; Cornejo and Hetz 2013; Mercado et al. 2016). It is also well established that phosphorylated JNK levels are elevated in disease-affected regions of postmortem AD brains (Shoji et al. 2000; Zhu et al. 2001; Le Pichon et al. 2017). Given the functional relationship between these pathways and cell death observed in preclinical models, it is logical to conclude that similar mechanisms may underlie neuronal loss in disease. Further unraveling the interplay between the initiators and executioners of neuronal cell death will be an important step toward understanding neurodegenerative disease genesis and progression (Fig. 4). Additional studies and new models designed to specifically investigate the interactions between these pathways should be a key future direction of the field.

Figure 4.

A model linking the initiators and executioners of neurodegenerative disease. A combination of aging, genetics, and environment contribute to the development of chronic neurodegenerative disease. These factors eventually lead to impaired neuronal homeostasis in response to neuron intrinsic and extrinsic disease initiators, including impaired protein homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, among others. Over time, this altered homeostasis can manifest as pathologies commonly observed in disease, such as β-amyloid plaques and tau tangles in Alzheimer's disease (AD) or Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease (PD). Neurons respond to these assaults by activating context-dependent, prodegenerative executioner pathways, precipitating impaired function and ultimately cell death. Disease-specific, stereotyped patterns of degeneration correlate with the clinical severity of neurodegenerative disease.

POTENTIAL FOR THERAPEUTICS TARGETING NEURONAL CELL DEATH

Neurodegenerative disease is one of the largest unmet medical needs of our time, with few to no disease-modifying treatments available to patients. The majority of therapeutic strategies that have been explored thus far have focused on disrupting disease-associated pathologies, or initiators of neuronal cell death, based on the framework defined in this review. Although many of these strategies are still under development, results from those that target Aβ plaques suggest that disrupting this pathology is not sufficient to slow the course of degeneration, at least when dosed in patients with preexisting pathology (Lane et al. 2012; Castellani et al. 2019). Alternative strategies targeting tau or α-syn may have greater potential to impact disease, as these pathologies tend to be more correlated with functional decline (Arriagada et al. 1992; Brier et al. 2016; Bejanin et al. 2017; Marks et al. 2017; Kametani and Hasegawa 2018). Ongoing studies will shed light on their therapeutic potential.

As mechanistic insight into the role of executioners in chronic neurodegenerative disease continues to emerge, opportunities to develop therapeutics that engage disease-relevant pathways may also arise. Two examples of this approach are molecules targeting DLK and RIPK1 that have recently advanced into clinical studies. Small molecule inhibitors for DLK have been developed that are capable of attenuating JNK signaling and downstream neuronal degeneration in several preclinical models including axonal injury, MPTP, and genetic models of chronic neurodegenerative disease (Patel et al. 2015; Larhammar et al. 2017; Le Pichon et al. 2017). Genentech/Roche has advanced the first DLK inhibitor into clinical trials for ALS (NCT02655614), although results have not yet been reported. In the case of RIPK1, preclinical data from genetic models and mice treated with RIPK1 inhibitors, including necrostatin-1, suggest a potential role for RIPK1 signaling in a number of disease contexts, including AD, ALS, and multiple sclerosis (Re et al. 2014; Ofengeim et al. 2015, 2017; Yang et al. 2017; Arrazola et al. 2019). Denali Therapeutics has recently advanced a CNS penetrant RIPK1 inhibitor into clinical trials, which is being tested in patients with AD and ALS (NCT03757325, NCT03757351). Although both of these programs are in the early stages of clinical study, results from these programs may provide insight into the potential of targeting these pathways for disease treatment.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Despite having been studied for more than a century (Beard 1896), there remain significant gaps in our understanding of neuronal cell death, particularly as it pertains to chronic neurodegenerative disease. The advent of new technologies, such as iPSC-derived cells from disease patients, as well as an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which vulnerable neuronal populations degenerate in disease will enable a deeper insight into the functional interplay between the initiators and executioners of neuronal cell death described here. Ultimately, these advances may translate into disease-modifying therapies that target context-specific cell death pathways, leading to an improvement in global health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to our colleagues whose research we could not cite or discuss owing to space limitations.

Footnotes

Editors: Kim Newton, James M. Murphy, and Edward A. Miao

Additional Perspectives on Cell Survival and Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Abisambra JF, Jinwal UK, Blair LJ, O'Leary JC III, Li Q, Brady S, Wang L, Guidi CE, Zhang B, Nordhues BA, et al. 2013. Tau accumulation activates the unfolded protein response by impairing endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Neurosci 33: 9498–9507. 10.1523/jneurosci.5397-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SM, Tyrrell PJ, Rothwell NJ. 2005. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 629–640. 10.1038/nri1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola MS, Saquel C, Catalan RJ, Barrientos SA, Hernandez DE, Catenaccio A, Court FA. 2019. Axonal degeneration is mediated by necroptosis activation. J Neurosci 39: 3832–3844. 10.1523/jneurosci.0881-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. 1992. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 42: 631–639. 10.1212/WNL.42.3.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi G, Schlehe JS, LaVoie MJ, Schwarz TL. 2014. Mitophagy of damaged mitochondria occurs locally in distal neuronal axons and requires PINK1 and Parkin. J Cell Biol 206: 655–670. 10.1083/jcb.201401070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin JD, Farg MA, Walker AK, McLean C, Tomas D, Horne MK. 2008. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of the unfolded protein response in human sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis 30: 400–407. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard J. 1896. The history of a transient nervous apparatus in certain Ichthyopsida. An account of the development and degeneration of ganglion cells and nerve fibers. Zool Jahrb 9: 319–426. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A, Sibilia M, Wagner EF. 1999. Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat Genet 21: 326–329. 10.1038/6854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejanin A, Schonhaut DR, La Joie R, Kramer JH, Baker SL, Sosa N, Ayakta N, Cantwell A, Janabi M, Lauriola M, et al. 2017. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 140: 3286–3300. 10.1093/brain/awx243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Navarria L, Zaltieri M, Falarti E, Bodei S, Sigala S, Battistin L, Spillantini M, Missale C, Spano P. 2011. Induction of the unfolded protein response by α-synuclein in experimental models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 116: 588–605. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE. 2015. Acquired axonal degeneration and regeneration: Recent insights and clinical correlations. Neurology 84: 2076–2085. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, Jaros E, Hersheson JS, Betts J, Klopstock T, et al. 2006. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet 38: 515–517. 10.1038/ng1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsello T, Forloni G. 2007. JNK signalling: A possible target to prevent neurodegeneration. Curr Pharm Des 13: 1875–1886. 10.2174/138161207780858384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82: 239–259. 10.1007/BF00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. 2003. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 24: 197–211. 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. 2015. Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on human studies. Nat Rev Neurosci 16: 109–120. 10.1038/nrn3887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, McCarthy J, Stern A, Christensen J, Owen C, Aldea P, Su Y, Hassenstab J, et al. 2016. Tau and Aβ imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med 8: 338ra66 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, O'Malley K. 2013. Axon degeneration in Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol 246: 72–83. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Sudhof TC. 2010. α-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329: 1663–1667. 10.1126/science.1195227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Branca C, Piras IS, Ferreira E, Huentelman MJ, Liang WS, Readhead B, Dudley JT, Spangenberg EE, Green KN, et al. 2017. Necroptosis activation in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci 20: 1236–1246. 10.1038/nn.4608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman CR, Höke A. 2015. Mechanisms of distal axonal degeneration in peripheral neuropathies. Neurosci Lett 596: 33–50. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Plascencia-Villa G, Perry G. 2019. The amyloid cascade and Alzheimer's disease therapeutics: Theory versus observation. Lab Invest 99: 958–970. 10.1038/s41374-019-0231-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RC, Suen KC, Ma CH, Elyaman W, Ng HK, Hugon J. 2002. Involvement of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α in neuronal degeneration. J Neurochem 83: 1215–1225. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinta SJ, Mallajosyula JK, Rane A, Andersen JK. 2010. Mitochondrial α-synuclein accumulation impairs complex I function in dopaminergic neurons and results in increased mitophagy in vivo. Neurosci Lett 486: 235–239. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Joo KM, Nam RH, Cho MH, Kim DJ, Lee WB, Cha CI. 2005. Decreased expression of calretinin in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of SOD1G93A transgenic mice. Brain Res 1035: 105–109. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciryam P, Tartaglia GG, Morimoto RI, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. 2013. Widespread aggregation and neurodegenerative diseases are associated with supersaturated proteins. Cell Rep 5: 781–790. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciryam P, Kundra R, Freer R, Morimoto RI, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. 2016. A transcriptional signature of Alzheimer's disease is associated with a metastable subproteome at risk for aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: 4753–4758. 10.1073/pnas.1516604113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Beibel M, Staufenbiel M, et al. 2009. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol 11: 909–913. 10.1038/ncb1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codolo G, Plotegher N, Pozzobon T, Brucale M, Tessari I, Bubacco L, de Bernard M. 2013. Triggering of inflammasome by aggregated α–synuclein, an inflammatory response in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE 8: e55375 10.1371/journal.pone.0055375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo VH, Hetz C. 2013. The unfolded protein response in Alzheimer's disease. Semin Immunopathol 35: 277–292. 10.1007/s00281-013-0373-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Credle JJ, Forcelli PA, Delannoy M, Oaks AW, Permaul E, Berry DL, Duka V, Wills J, Sidhu A. 2015. α-Synuclein-mediated inhibition of ATF6 processing into COPII vesicles disrupts UPR signaling in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 76: 112–125. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran BP, Murray HJ, O'Connor JJ. 2003. A role for c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the inhibition of long-term potentiation by interleukin-1β and long-term depression in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuroscience 118: 347–357. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00941-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P, Maloney AJ. 1976. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 308: 1403 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)91936-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Dawson VL. 2017. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neuronal cell death: Potential therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 57: 437–454. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckwerth TL, Elliott JL, Knudson CM, Johnson EM Jr, Snider WD, Korsmeyer SJ. 1996. BAX is required for neuronal death after trophic factor deprivation and during development. Neuron 17: 401–411. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80173-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejanovic B, Huntley MA, De Mazière A, Meilandt WJ, Wu T, Srinivasan K, Jiang Z, Gandham V, Friedman BA, Ngu H, et al. 2018. Changes in the synaptic proteome in tauopathy and rescue of tau-induced synapse loss by C1q antibodies. Neuron 100: 1322–1336.e7. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuro A, Parker I, Stutzmann GE. 2010. Calcium signaling and amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 285: 12463–12468. 10.1074/jbc.R109.080895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ. 2009. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 13010–13015. 10.1073/pnas.0903691106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. 2008. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J Biol Chem 283: 9089–9100. 10.1074/jbc.M710012200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. 2007. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 35: 495–516. 10.1080/01926230701320337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Melachroinou K, Roumeliotis T, Garbis SD, Ntzouni M, Margaritis LH, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K. 2010. Cell-produced α-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. J Neurosci 30: 6838–6851. 10.1523/jneurosci.5699-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatokun AA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. 2014. Parthanatos: Mitochondrial-linked mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Br J Pharmacol 171: 2000–2016. 10.1111/bph.12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KA, Harder JM, Fornarola LB, Freeman RS, Clark AF, Pang IH, John SW, Libby RT. 2012. JNK2 and JNK3 are major regulators of axonal injury-induced retinal ganglion cell death. Neurobiol Dis 46: 393–401. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MI, Zhou J, Botto M, Tenner AJ. 2004. Absence of C1q leads to less neuropathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 24: 6457–6465. 10.1523/jneurosci.0901-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK. 1999. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: A review of progress. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66: 137–147. 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freer R, Sormanni P, Vecchi G, Ciryam P, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. 2016. A protein homeostasis signature in healthy brains recapitulates tissue vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease. Sci Adv 2: e1600947 10.1126/sciadv.1600947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M, Tolkovsky AM, Borutaite V, Coleman M, Brown GC. 2018. Neuronal cell death. Physiol Rev 98: 813–880. 10.1152/physrev.00011.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Hardy J, Duff KE. 2018. Selective vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 21: 1350–1358. 10.1038/s41593-018-0221-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Possenti A, Freer R, Nakano Y, Hernandez Villegas NC, Tang M, Cauhy PVM, Lassus BA, Chen S, Fowler SL, et al. 2019. A tau homeostasis signature is linked with the cellular and regional vulnerability of excitatory neurons to tau pathology. Nat Neurosci 22: 47–56. 10.1038/s41593-018-0298-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdar Z, Swan P, Fuerth B, Callaghan SM, Park DS, Cregan SP. 2010. Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J Neurosci 30: 16938–16948. 10.1523/jneurosci.1598-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Summers DW, Sasaki Y, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. 2013. Sarm1-mediated axon degeneration requires both SAM and TIR interactions. J Neurosci 33: 13569–13580. 10.1523/jneurosci.1197-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts J, Summers DW, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. 2016. Axon self-destruction: New links among SARM1, MAPKs, and NAD+ metabolism. Neuron 89: 449–460. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AS, Wang B, Pozniak CD, Chen M, Watts RJ, Lewcock JW. 2011. DLK induces developmental neuronal degeneration via selective regulation of proapoptotic JNK activity. J Cell Biol 194: 751–764. 10.1083/jcb.201103153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Orsomando G, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Coleman MP. 2015. Absence of SARM1 rescues development and survival of NMNAT2-deficient axons. Cell Rep 10: 1974–1981. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JG, Dingledine R, Greenamyre JT. 2005. Gene expression profiling of rat midbrain dopamine neurons: Implications for selective vulnerability in parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis 18: 19–31. 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, White CL III, Araoz C. 1989. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 7611–7615. 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagno J, Xu X, Karajgikar M, Brown A, Cregan SP. 2013. Microglia-derived TNFα induces apoptosis in neural precursor cells via transcriptional activation of the Bcl-2 family member Puma. Cell Death Dis 4: e538 10.1038/cddis.2013.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JL, Narasimhan S, Changolkar L, He Z, Stieber A, Zhang B, Gathagan RJ, Iba M, McBride JD, Trojanowski JQ, et al. 2016. Unique pathological tau conformers from Alzheimer's brains transmit tau pathology in nontransgenic mice. J Exp Med 213: 2635–2654. 10.1084/jem.20160833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M. 2018. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol 217: 459–472. 10.1083/jcb.201709069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC, et al. 2013. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer's disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493: 674–678. 10.1038/nature11729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. 2015. Innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Immunol 16: 229–236. 10.1038/ni.3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger N, Bouley J, Sikoglu EM, An J, Moore CM, King JA, Bowser R, Freeman MR, Brown RH Jr. 2016. Attenuated traumatic axonal injury and improved functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in mice lacking Sarm1. Brain 139: 1094–1105. 10.1093/brain/aww001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Saxena S. 2017. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurol 13: 477–491. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Nimchinsky EA, Celio MR, Bouras C, Morrison JH. 1993. Calretinin-immunoreactive neocortical interneurons are unaffected in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 152: 145–149. 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90504-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman LB, Merritt SE, Fan G. 1994. Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of dual leucine zipper bearing kinase. A novel serine/threonine protein kinase that defines a second subfamily of mixed lineage kinases. J Biol Chem 269: 30808–30817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, Merry KM, Shi Q, Rosenthal A, Barres BA, et al. 2016. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352: 712–716. 10.1126/science.aad8373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, van Haastert ES, Eikelenboom P, de Vos RA, Rozemuller JM, Scheper W. 2007. Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354: 707–711. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, van Haastert ES, Nijholt DA, Rozemuller AJ, Eikelenboom P, Scheper W. 2009. The unfolded protein response is activated in pretangle neurons in Alzheimer's disease hippocampus. Am J Pathol 174: 1241–1251. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannielli A, Bido S, Folladori L, Segnali A, Cancellieri C, Maresca A, Massimino L, Rubio A, Morabito G, Caporali L, et al. 2018. Pharmacological inhibition of necroptosis protects from dopaminergic neuronal cell death in Parkinson's disease models. Cell Rep 22: 2066–2079. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba M, Guo JL, McBride JD, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2013. Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's-like tauopathy. J Neurosci 33: 1024–1037. 10.1523/jneurosci.2642-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Ofengeim D, Najafov A, Das S, Saberi S, Li Y, Hitomi J, Zhu H, Chen H, Mayo L, et al. 2016. RIPK1 mediates axonal degeneration by promoting inflammation and necroptosis in ALS. Science 353: 603–608. 10.1126/science.aaf6803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT Jr. 1993. Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: A pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell 73: 1055–1058. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BN, Berger AK, Cortese GP, Lavoie MJ. 2012. The ubiquitin E3 ligase parkin regulates the proapoptotic function of Bax. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 6283–6288. 10.1073/pnas.1113248109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. 2013. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 246: 35–43. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam TI, Mao X, Park H, Chou SC, Karuppagounder SS, Umanah GE, Yun SP, Brahmachari S, Panicker N, Chen R, et al. 2018. Poly(ADP-ribose) drives pathologic α-synuclein neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Science 362: eaat8407 10.1126/science.aat8407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametani F, Hasegawa M. 2018. Reconsideration of amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease. Front Neurosci 12: 25 10.3389/fnins.2018.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kfoury N, Holmes BB, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI. 2012. Trans-cellular propagation of Tau aggregation by fibrillar species. J Biol Chem 287: 19440–19451. 10.1074/jbc.M112.346072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Ahn JS, Park W, Hong SK, Jeon SR, Roh SW, Lee S. 2018. Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) in moderate to severe head injured patients: Pure DAI vs. non-pure DAI. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 171: 116–123. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Tong Y, Gautier CA, Shen J. 2009. Absence of nigral degeneration in aged parkin/DJ-1/PINK1 triple knockout mice. J Neurochem 111: 696–702. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06350.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen M, Ham J. 2014. Programmed cell death during neuronal development: The sympathetic neuron model. Cell Death Differ 21: 1025–1035. 10.1038/cdd.2014.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. 2007. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev 87: 99–163. 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, Kuan C, Yang D, Karasuyama H, Rakic P, Flavell RA. 1996. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature 384: 368–372. 10.1038/384368a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundra R, Ciryam P, Morimoto RI, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. 2017. Protein homeostasis of a metastable subproteome associated with Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114: E5703–E5711. 10.1073/pnas.1618417114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RF, Shineman DW, Steele JW, Lee LB, Fillit HM. 2012. Beyond amyloid: The future of therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease. Adv Pharmacol 64: 213–271. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394816-8.00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larhammar M, Huntwork-Rodriguez S, Jiang Z, Solanoy H, Sengupta Ghosh A, Wang B, Kaminker JS, Huang K, Eastham-Anderson J, Siu M, et al. 2017. Dual leucine zipper kinase-dependent PERK activation contributes to neuronal degeneration following insult. eLife 6: e20725 10.7554/eLife.20725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. 2013. The many faces of α-synuclein: From structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci 14: 38–48. 10.1038/nrn3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JR, Klocke BJ, D'Sa C, Flavell RA, Roth KA. 2002. Strain-dependent neurodevelopmental abnormalities in caspase-3-deficient mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61: 673–677. 10.1093/jnen/61.8.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pichon CE, Meilandt WJ, Dominguez S, Solanoy H, Lin H, Ngu H, Gogineni A, Sengupta Ghosh A, Jiang Z, Lee SH, et al. 2017. Loss of dual leucine zipper kinase signaling is protective in animal models of neurodegenerative disease. Sci Transl Med 9: eaag0394 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Guo Y, Tang J, Jiang J, Chen Z. 2014. New insights into the roles of CHOP-induced apoptosis in ER stress. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 46: 629–640. 10.1093/abbs/gmu048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang WS, Dunckley T, Beach TG, Grover A, Mastroeni D, Ramsey K, Caselli RJ, Kukull WA, McKeel D, Morris JC, et al. 2008. Altered neuronal gene expression in brain regions differentially affected by Alzheimer's disease: A reference data set. Physiol Genomics 33: 240–256. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00242.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby RT, Li Y, Savinova OV, Barter J, Smith RS, Nickells RW, John SW. 2005. Susceptibility to neurodegeneration in a glaucoma is modified by Bax gene dosage. PLoS Genet 1: 17–26. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Kehm V, Carroll J, Zhang B, O'Brien P, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2012. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338: 949–953. 10.1126/science.1227157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks SM, Lockhart SN, Baker SL, Jagust WJ. 2017. Tau and β-amyloid are associated with medial temporal lobe structure, function, and memory encoding in normal aging. J Neurosci 37: 3192–3201. 10.1523/jneurosci.3769-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier S, Bell M, Lyons DN, Ingram A, Chen J, Gensel JC, Zhu H, Nelson PT, Abisambra JF. 2015. Identification of novel tau interactions with endoplasmic reticulum proteins in Alzheimer's disease brain. J Alzheimers Dis 48: 687–702. 10.3233/JAD-150298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisl G, Rajah L, Cohen SAI, Pfammatter M, Šarić A, Hellstrand E, Buell AK, Aguzzi A, Linse S, Vendruscolo M, et al. 2017. Scaling behaviour and rate-determining steps in filamentous self-assembly. Chem Sci 8: 7087–7097. 10.1039/C7SC01965C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado G, Castillo V, Soto P, Sidhu A. 2016. ER stress and Parkinson's disease: Pathological inputs that converge into the secretory pathway. Brain Res 1648: 626–632. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BR, Press C, Daniels RW, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. 2009. A dual leucine kinase-dependent axon self-destruction program promotes Wallerian degeneration. Nat Neurosci 12: 387–389. 10.1038/nn.2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi M, Harada M, Kondo T, Riederer P, Inagaki H, Minami M, Nagatsu T. 1994. Interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-α are elevated in the brain from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci Lett 180: 147–150. 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratore CR, Zhou C, Liao M, Fernandez MA, Taylor WM, Lagomarsino VN, Pearse RV II, Rice HC, Negri JM, He A, et al. 2017. Cell-type dependent Alzheimer's disease phenotypes: Probing the biology of selective neuronal vulnerability. Stem Cell Rep 9: 1868–1884. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjar M, Saleh D, Zelic M, Nogusa S, Shah S, Tai A, Finger JN, Polykratis A, Gough PJ, Bertin J, et al. 2016. RIPK1 and RIPK3 kinases promote cell-death-independent inflammation by Toll-like receptor 4. Immunity 45: 46–59. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neniskyte U, Neher JJ, Brown GC. 2011. Neuronal death induced by nanomolar amyloid β is mediated by primary phagocytosis of neurons by microglia. J Biol Chem 286: 39904–39913. 10.1074/jbc.M111.267583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neniskyte U, Vilalta A, Brown GC. 2014. Tumour necrosis factor α-induced neuronal loss is mediated by microglial phagocytosis. FEBS Lett 588: 2952–2956. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofengeim D, Ito Y, Najafov A, Zhang Y, Shan B, DeWitt JP, Ye J, Zhang X, Chang A, Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, et al. 2015. Activation of necroptosis in multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep 10: 1836–1849. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofengeim D, Mazzitelli S, Ito Y, DeWitt JP, Mifflin L, Zou C, Das S, Adiconis X, Chen H, Zhu H, et al. 2017. RIPK1 mediates a disease-associated microglial response in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114: E8788–E8797. 10.1073/pnas.1714175114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos G, Lladó J. 2014. Tumor necrosis factor α: A link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Mediators Inflamm 2014: 861231 10.1155/2014/861231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, Sheehan AE, Avery MA, Hackett R, Logan MA, et al. 2012. dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science 337: 481–484. 10.1126/science.1223899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Cohen F, Dean BJ, De La Torre K, Deshmukh G, Estrada AA, Ghosh AS, Gibbons P, Gustafson A, Huestis MP, et al. 2015. Discovery of dual leucine zipper kinase (DLK, MAP3K12) inhibitors with activity in neurodegeneration models. J Med Chem 58: 401–418. 10.1021/jm5013984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten DA, Wong J, Khacho M, Soubannier V, Mailloux RJ, Pilon-Larose K, MacLaurin JG, Park DS, McBride HM, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, et al. 2014. OPA1-dependent cristae modulation is essential for cellular adaptation to metabolic demand. EMBO J 33: 2676–2691. 10.15252/embj.201488349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavitt GD, Ron D. 2012. New insights into translational regulation in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a012278 10.1101/cshperspect.a012278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. 2015. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron 85: 257–273. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozniak CD, Sengupta Ghosh A, Gogineni A, Hanson JE, Lee SH, Larson JL, Solanoy H, Bustos D, Li H, Ngu H, et al. 2013. Dual leucine zipper kinase is required for excitotoxicity-induced neuronal degeneration. J Exp Med 210: 2553–2567. 10.1084/jem.20122832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re DB, Le Verche V, Yu C, Amoroso MW, Politi KA, Phani S, Ikiz B, Hoffmann L, Koolen M, Nagata T, et al. 2014. Necroptosis drives motor neuron death in models of both sporadic and familial ALS. Neuron 81: 1001–1008. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishal I, Fainzilber M. 2014. Axon–soma communication in neuronal injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 15: 32–42. 10.1038/nrn3609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. 2007. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science 316: 750–754. 10.1126/science.1141736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Poirier MA. 2004. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med 10(Suppl): S10–S17. 10.1038/nm1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, Ransohoff RM, Greenberg ME, Barres BA, Stevens B. 2012. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 74: 691–705. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Chowdhury S, Ma R, Le KX, Hong S, Caldarone BJ, Stevens B, Lemere CA. 2017. Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci Transl Med 9: eaaf6295 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohama S. 2000. Apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease—An update. Apoptosis 5: 9–16. 10.1023/A:1009625323388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Iwakami N, Takeuchi S, Waragai M, Suzuki M, Kanazawa I, Lippa CF, Ono S, Okazawa H. 2000. JNK activation is associated with intracellular β-amyloid accumulation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 85: 221–233. 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00245-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtifman A, Ward CW, Laver DR, Bannister ML, Lopez JR, Kitazawa M, LaFerla FM, Ikemoto N, Querfurth HW. 2010. Amyloid-β protein impairs Ca2+ release and contractility in skeletal muscle. Neurobiol Aging 31: 2080–2090. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silke J, Rickard JA, Gerlic M. 2015. The diverse role of RIP kinases in necroptosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol 16: 689–697. 10.1038/ni.3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Watkins TA. 2018. Therapeutic opportunities and pitfalls in the treatment of axon degeneration. Curr Opin Neurol 31: 693–701. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Pitts J, Hertz NT, Yang J, Yamagishi Y, Olsen O, Tešić Mark M, Molina H, Tessier-Lavigne M. 2016. Axon degeneration gated by retrograde activation of somatic pro-apoptotic signaling. Cell 164: 1031–1045. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu M, Sengupta Ghosh A, Lewcock JW. 2018. Dual leucine zipper kinase inhibitors for the treatment of neurodegeneration. J Med Chem 61: 8078–8087. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slee EA, Adrain C, Martin SJ. 2001. Executioner caspase-3, -6, and -7 perform distinct, non-redundant roles during the demolition phase of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 276: 7320–7326. 10.1074/jbc.M008363200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliter DA, Martinez J, Hao L, Chen X, Sun N, Fischer TD, Burman JL, Li Y, Zhang Z, Narendra DP, et al. 2018. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature 561: 258–262. 10.1038/s41586-018-0448-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL, Mallucci GR. 2016. The unfolded protein response: Mechanisms and therapy of neurodegeneration. Brain 139: 2113–2121. 10.1093/brain/aww101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Pritzkow S. 2018. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 21: 1332–1340. 10.1038/s41593-018-0235-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K, Friedman BA, Larson JL, Lauffer BE, Goldstein LD, Appling LL, Borneo J, Poon C, Ho T, Cai F, et al. 2016. Untangling the brain's neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative transcriptional responses. Nat Commun 7: 11295 10.1038/ncomms11295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers DW, Gibson DA, DiAntonio A, Milbrandt J. 2016. SARM1-specific motifs in the TIR domain enable NAD+ loss and regulate injury-induced SARM1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: E6271–E6280. 10.1073/pnas.1601506113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. 2010. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. J Alzheimers Dis 20: S265–S279. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferro P, Burke RE. 2016. Retrograde axonal degeneration in Parkinson disease. J Parkinsons Dis 6: 1–15. 10.3233/JPD-150769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi A, Bradke F. 2013. The DLK signalling pathway—A double-edged sword in neural development and regeneration. EMBO Rep 14: 605–614. 10.1038/embor.2013.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiew E, Falconer D, Reed N, Höke A. 2017. Deletion of Sarm1 gene is neuroprotective in two models of peripheral neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 22: 162–171. 10.1111/jns.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. 2000. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 287: 664–666. 10.1126/science.287.5453.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Grootjans S, Callewaert N, Takahashi N. 2013. Necrostatin-1 blocks both RIPK1 and IDO: Consequences for the study of cell death in experimental disease models. Cell Death Differ 20: 185–187. 10.1038/cdd.2012.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. 2014. Regulated necrosis: The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 135–147. 10.1038/nrm3737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venderova K, Park DS. 2012. Programmed cell death in Parkinson's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a009365 10.1101/cshperspect.a009365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venegas C, Kumar S, Franklin BS, Dierkes T, Brinkschulte R, Tejera D, Vieira-Saecker A, Schwartz S, Santarelli F, Kummer MP, et al. 2017. Microglia-derived ASC specks cross-seed amyloid-β in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 552: 355–361. 10.1038/nature25158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M, Vats A, Taneja V. 2015. Toxic species in amyloid disorders: Oligomers or mature fibrils. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 18: 138–145. 10.4103/0972-2327.150606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]