Abstract

CONTEXT:

Screening children for social determinants of health (SDOHs) has gained attention in recent years, but there is a deficit in understanding the present state of the science.

OBJECTIVE:

To systematically review SDOH screening tools used with children, examine their psychometric properties, and evaluate how they detect early indicators of risk and inform care.

DATA SOURCES:

Comprehensive electronic search of PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Web of Science Core Collection.

STUDY SELECTION:

Studies in which a tool that screened children for multiple SDOHs (defined according to Healthy People 2020) was developed, tested, and/or employed.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Extraction domains included study characteristics, screening tool characteristics, SDOHs screened, and follow-up procedures.

RESULTS:

The search returned 6274 studies. We retained 17 studies encompassing 11 screeners. Study samples were diverse with respect to biological sex and race and/or ethnicity. Screening was primarily conducted in clinical settings with a parent or caregiver being the primary informant for all screeners. Psychometric properties were assessed for only 3 screeners. The most common SDOH domains screened included the family context and economic stability. Authors of the majority of studies described referrals and/or interventions that followed screening to address identified SDOHs.

LIMITATIONS:

Following the Healthy People 2020 SDOH definition may have excluded articles that other definitions would have captured.

CONCLUSIONS:

The extent to which SDOH screening accurately assessed a child’s SDOHs was largely unevaluated. Authors of future research should also evaluate if referrals and interventions after the screening effectively address SDOHs and improve child well-being.

Social determinants of health (SDOHs), according to the World Health Organization, are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”1 Healthy People 2020 organizes SDOH into 5 key domains: economic stability (eg, poverty and food insufficiency), education (eg, high school graduate and early childhood education), social and community context (eg, concerns about immigration status and social support), health and health care (eg, health insurance status and access to a health care provider), and neighborhood and built environment (eg, neighborhood crime and quality of housing).2 Although SDOHs influence health and well-being among individuals of all ages, it is particularly important to consider SDOHs among children and youth given that the physical, social, and emotional capabilities that develop early in life provide the foundation for life course health and well-being.3 Thus, identifying and intervening on the basis of these factors early could serve as a primary prevention against future health conditions.

Much controversy surrounds screening children and youth for SDOHs, however. Some experts claim screening is unethical if done without ensuring that identified social needs are met, likewise generating unfulfilled expectations.4,5 Others argue that even in the absence of referrals, screening has benefits such as improving diagnostic algorithms, identifying children and youth who need more support, improving patient-provider relationships, and collecting data for an epidemiological purpose.6–8 Although many child service professionals feel ill-equipped to address patients’ social needs within the current systems,9,10 several care teams cite that they identify unmet social needs and offer linkages to social services.11,12 This screening debate is largely centered on a deficit in understanding the present state of the science: what screening tools exist? How accurate are they? How do screening results inform care? In the present systematic review, we aim to answer these questions. Although authors of previous reports have outlined different SDOH screening tools used among children in clinical settings,13,14 there has been no systematic review of SDOH screeners used among children in various settings. In this review, we aim to systematically catalog the different SDOH screening tools used to assess social conditions among children and youth, examine their psychometric properties, and evaluate how they are used to detect early indicators of risk and inform care.

METHODS

Search Strategy

Authors of studies in this review developed and/or used a tool to screen children and youth for SDOHs. We systematically reviewed the literature using a protocol informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to search research databases, screen published studies, apply inclusion and exclusion criteria, and select relevant literature for review.15 A trained clinical health sciences librarian (S.T.W.) performed our comprehensive electronic search of publications using the following databases: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCO, Embase via Elsevier, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Web of Science Core Collection. Our search was restricted to English-only articles. All database results were collected from the inception of the database through November 2018. Search terms were used to retrieve articles addressing the 3 main concepts of the search strategy: (1) SDOHs, (2) pediatric population, and (3) screening administered by a child service provider (eg, a clinician, social worker, or teacher) or in a service provider setting (eg, self-administered at a pediatrician’s office). The exact search strategy used in each of the electronic databases is reported in the Supplemental Information. Results were downloaded to EndNote, and duplicates were removed. All references were uploaded to Covidence systematic review software (https://www.covidence.org), a web-based tool designed to facilitate and track each step of the abstraction and review process.

Inclusion Criteria

We included studies in which a tool that screened children (or caregivers and/or informants on behalf of children) for multiple SDOHs was developed, described, tested, and/or employed, where SDOHs are defined according to Healthy People 2020.2 Given Healthy People 2020 guided our understanding of SDOHs (an American framework), to be included in this review, studies had to be conducted within the United States, be peer-reviewed, and be published in English. Following these inclusion criteria, we excluded studies of screeners that only screened for 1 SDOH; did not conduct screening among children (age 0–25 years) or their caregivers and/or informants; were not published in English; were conducted outside of the United States; or were book chapters, reviews, letters, abstracts, or dissertations.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

We used Covidence, an online platform, to manage screening and selection of studies. For the title and abstract screening, each title was independently and blindly screened by 2 authors, and a third author resolved discrepancies. The authorship team followed this same independent, blind review for the full-text review. At the end of the title and abstract screen and full-text review phase, the lead investigators reviewed the included studies to confirm that all studies met the inclusion criteria. For any articles in question, the lead investigators convened to determine the articles’ inclusion statuses. At the conclusion of the full-text review, study authors reviewed the reference lists of included studies to identify any additional studies for inclusion.

After reviewing the full texts of studies, the research team developed a data extraction tool in REDCap (a secure web platform for building and managing online databases and surveys) to extract the following information: study characteristics (ie, author and publication year, study type, study setting, age range of screened children, sample size of screened children, percent female sex of screened children, race and/or ethnicity of screened children, and study aims); screening tool characteristics (ie, average time to complete screener, screening setting, screening method, informant, training required for screening professionals, languages available, appropriate for low-literacy populations [ie, sixth grade reading level or lower], and validation); what SDOH domains the screener measured (per Healthy People 2020 guidelines; ie, economic stability, education, health and health care, neighborhood and build environment, and social and community context2); and screening follow-up procedures (ie, results were discussed with respondents, referrals were offered and/or scheduled, and/or intervention was delivered). Each primary reviewer extracted data from a set of studies that passed the research team’s full-text review, and secondary reviewers confirmed the primary reviewers’ extraction to ensure that the primary reviewer recorded accurate information. The team resolved any discrepancies through discussion and consensus.

RESULTS

Study Selection

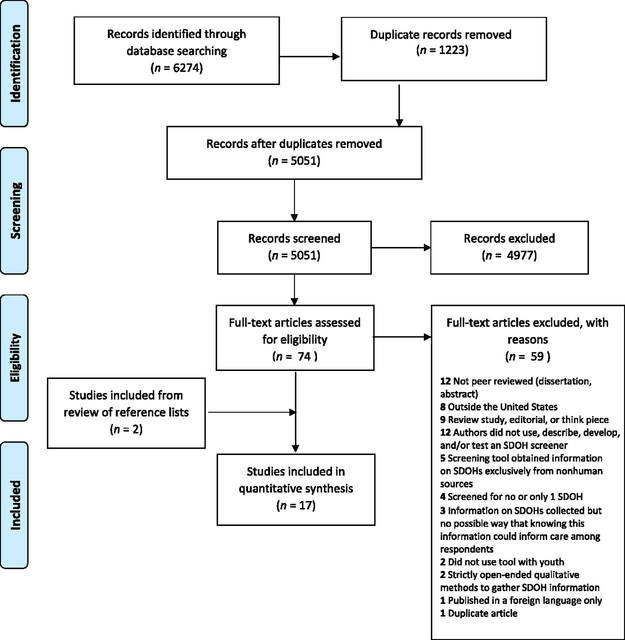

The electronic search of databases returned 6274 references (of which 1223 were duplicates), resulting in 5051 studies. In the initial title and abstract screen, the research team deemed 4977 studies irrelevant, leaving 74 full texts to review. A total of 15 studies passed the full screen review, and we identified 2 additional studies from the reference lists of included studies. We retained and abstracted 17 studies. Figure 1 reveals the PRISMA flow diagram.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 reveals various study characteristics from the 17 studies that span 11 unique screeners. With the exception of 1 study,16 all studies took place in a medical setting. Among the 14 studies in which the ages of screened individuals were reported, the majority (ie, 8 studies) included screening for SDOHs exclusively in young childhood (ages 0 to 5 years).11,16–22 Study samples were primarily evenly divided with respect to biological sex. Among the 13 studies in which the races and/or ethnicities of screened individuals were reported, 10 study samples contained a majority nonwhite sample.11,12,17,18,20–25

TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics

| Screening Tool | Author and Year | Study Type | Setting | Age Range, y | Sample Size | Female Sex, % | Race and Ethnicity (%) | Study Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Dubowitz et al18 2007 | OC | Pediatric clinic serving an urban, low-income population | 0–5 | 216 | 44 | African American (92); white (3); multiracial (5) | Estimate the prevalence of parental depressive symptoms among parents at a pediatric primary care clinic and evaluate a parental depression screen |

| Dubowitz et al17 2009 | RCT | Pediatric clinic serving an urban, low-income population in Baltimore, Maryland | 0–5 | 308 | 46 | African American (93) | Evaluate the efficacy of the SEEK model of pediatric primary care in reducing the occurrence of child maltreatment | |

| Dubowitz et al19 2012 | RCT | Pediatric practices serving suburban, middle-income populations | 0–5 | 595 | 50 | African American (4); white (86); Asian American (2); Hispanic (1); other (8) | Examine if the SEEK model is more effective in reducing maltreatment than standard pediatric practice when implemented in a middle-income suburban population | |

| Eismann et al26 2018 | Observational only | Pediatric practice, family medicine practice, and FQHC serving various populations | 0–18 | 1057 | NR | NR | Assess the generalizability of the SEEK model and identify barriers and facilitators to integrating the SEEK model into standard clinical practice | |

| iScreen | Gottlieb et al27 2014 | RCT | Pediatric emergency department serving a low-income urban population in California | 0–18 | 538 | NR | NR | Compare psychosocial and socioeconomic adversity disclosure rates by caregivers of children in face-to-face interviews versus electronic formats |

| Gottlieb et al12 2016 | RCT | Primary care or urgent care departments in safety-net hospitals serving low-income populations in California | 0–18 | 1809 | 51 | African American (26); white (4); Asian American (5); Hispanic (57) | Evaluate if addressing social issues during pediatric primary and urgent health care visits decreases families’ social needs and improves children’s health | |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Hensley et al28 2017 | Observational only | FQHC serving Southwestern Ohio and Northern Kentucky | NR | 114 | NR | NR | Explore the process of systematically screening pediatric patients and their families for SD0H risks |

| FMI | McKelvey et al16 2016 | Observational only | Home visiting programs serving at-risk families in the Southern United States | 0–5 | 1282 | 51 | African American (22); white (60); Hispanic (16); other (2) | Develop an assessment of children’s exposure to ACEs |

| ASK Tool | Selvaraj et al23 2018 | Observational only | Pediatric primary care clinic serving an urban, low-income population in Chicago, Illinois | 0–18 | 2569 | 48 | African American (55); white (7); Asian American (5); Hispanic (21); other (12) | Determine the prevalence of and demographic characteristics associated with toxic stress risk factors, the impact of screening on referral rates to community resources, and feasibility and acceptability in a medical home |

| IHELP | Colvin et al29 2016 | Observational only | Pediatric hospital in Kansas City, Missouri | NR | 347 | 46 | African American (22); white (55); Asian American (1); other (22) | Determine if a brief intervention using multiple behavioral strategies to increase intervention intensity could improve screening for social needs by pediatric residents |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Garg et al24 2007 | RCT | Hospital-based pediatric clinic serving a low-income, urban population | 0–10 | 100 | NR | African American (96); white (1); Hispanic (3) | Evaluate the feasibility and impact of an intervention on the management of family psychosocial topics at well-child care visits |

| Garg et al11 2015 | RCT | Community health centers serving an urban population in Boston, Massachusetts | 0–5 | 168 | NR | African American (44); white (24); Asian American (2); Hispanic (23); Pacific Islander and/or Native Hawaiian (1); Multiracial (4) | Evaluate the effect of a clinic-based screening and referral system on families’ receipt of community-based resources for unmet basic needs | |

| Zielinski et al30 2017 | Observational only | Primary care pediatric practice serving a low-income population in Rochester New York | NR | 602 | NR | NR | Evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of integrating the WE CARE screen into all well-child visits to increase the detection of family psychosocial needs and resultant social work referrals | |

| FAMNEEDS | Uwemedimo and May25 2018 | Observational only | Hospital-based pediatric ambulatory practice in New York City New York | 0–18 | 299 | NR | African American (30); white (8); Hispanic (34); other (26) | Determine if the integration of FAMNEEDS into routine pediatric care services at a hospital-based practice increases the referral to and receipt of social service resources among children in immigrant families |

| Child ACE Tool | Marie-Mitchell and O’Connor20 2013 | Observational only | FQHC serving an urban population | 0–5 | 102 | 0.51 | African American (57); Hispanic (43) | Pilot test a tool to screen for ACEs and explore the ability of this tool to distinguish early child outcomes between lower- and higher-risk children |

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record | Beck et al21 2012 | Observational only | Hospital-based pediatric clinic serving an urban population in Cincinnati, Ohio | 0–5 | 639 | 48 | African American (71); white (20); other (9) | Determine social risk documentation rates among newborns using a new electronic template |

| Health-Related Social Problems screener | Fleegler et al22 2007 | Observational only | Outpatient pediatric clinics serving an urban population in Boston, Massachusetts and Maryland | 0–6 | 205 | 52 | African American (28); Hispanic (57); other (15) | Characterize families’ cumulative burdens of health-related social problems regarding access to health care, housing, food security, income security, and intimate partner violence; assess families’ experiences regarding screening and referral for social problems; and evaluate parental acceptability of screening and referral |

Age range, sample size, percent female sex, and race and/or ethnicity information reflects that of screened individuals only. ASK, Addressing Social Key Questions for Health; FAMNEEDS, Family Needs Screening Program; FMI, Family Map Inventories; FQHC, federally qualified health center; NR, not reported; OC, observational with comparison group; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Screener Characteristics

Table 2 depicts SDOH screener characteristics from the 11 unique screeners included in this review. Screening was conducted in a doctor’s or pediatrician’s office for the majority of screeners (ie, 8 screeners), with a parent or caregiver being the primary informant for all screeners. Two screeners included additional information reported by a social worker16 or physician.20 Screeners were completed via a variety of methods, including paper and pencil,11,17–20,23–26,30 computer or tablet,17–19,22,26,27 face-to-face interview,12,16,21,27–29 and phone interview.12,27 All screeners were available in English, with 7 screeners also available in Spanish.11,12,17–20,22–27,30 Three screeners had validity and/or reliability assessed in ≥1 study.18,24,29

TABLE 2.

Screening Tool Characteristics

| Screening Tool | Screening Setting | Screening Method | Informant | Training for Screening Professionals | Average Time to Complete Screener, min | Available Languages | Appropriate for Low-Literacy Populations | Validity and/or Reliability Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ17–19,26 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil; computer or tablet | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 3–4 | English; Spanish | NR | Yes18 |

| iScreen12,27 | Hospital | Computer or tablet; face-to-face interview; or phone interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 10 | English; Spanish | Yes | No |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool28 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | 6 | English | NR | No |

| FMI16 | Home | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver; social worker | Yes | NR | English | NR | No |

| ASK Tool23 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English; Spanish | NR | No |

| IHELP29 | Hospital | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English | NR | Yes (validity only)29 |

| WE CARE survey instrument11,24,30 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | NR | 4–5 | English; Spanish | Yes | Yes24 |

| FAMNEEDS25 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver | Yes | NR | English; Spanish; Haitian Creole; Urdu; Punjabi; Hindi; Arabic | NR | No |

| Child ACE Tool20 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Paper and pencil | Parent or caregiver; physician | NR | 5 | English; Spanish | NR | No |

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record21 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Face-to-face interview | Parent or caregiver | NR | NR | English | NR | No |

| Health-Related Social Problems screener22 | Doctor’s or pediatrician’s office | Computer or tablet | Parent or caregiver | NR | 20 | English; Spanish | Yes | No |

ASK, Addressing Social Key Questions for Health; FAMNEEDS, Family Needs Screening Program; FMI, Family Map Inventories; NR, not reported.

With respect to the time frame that respondents were asked to reflect on when answering questions about SDOHs, the majority of screeners (ie, 6 screeners) did not have a clearly defined referent period (eg, past 30 days, past year, or lifetime); the referent periods for other screeners varied by question,18,22,28 and only 2 screeners had a single, clearly defined referent period for all included questions.16,24 Regarding how the SDOH screeners were developed, only 4 screeners reported being informed by practice18,21,24 and/or expert opinion.18,21,23,24 Remaining screeners were solely adaptations of previous tools or did not report how they were developed.

Table 3 reveals the specific SDOH domains assessed in each screener. Because many screeners were used to assess adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (events that typically occur within the family context), for the purposes of this review, we added an additional domain labeled family context to the Healthy People 2020 domains included in Table 3. The family context domain was assessed in all screeners, and the economic stability domain was assessed in all but 1 screener.20 Common areas examined under the family context domain included violence in the household,11,12,16–20,22,24–30 child abuse and neglect,16,20,23 and mental illness or substance abuse among parents or other household members.11,12,16–21,23–27,30 Although Healthy People 2020 identifies interpersonal violence as an SDOH within the neighborhood and built environment domain, we elected to include interpersonal violence in our newly created family context domain because this SDOH occurs within the family unit. Common areas examined under the economic stability domain included food insufficiency,11,12,16–19,21–30 housing instability11,12,16,22–25,27–30 and difficulty paying bills, making ends meet, or meeting basic needs.11,12,21–25,27,28,30 Seven screeners assessed the education domain, which included questions assessing parental education11,20,23–25,28,30 and access to child care.11,12,23–25,27,30 Six screeners assessed the health and health care domain, with parent and child health insurance status12,22,25,27,29 being the most common area examined. Seven screeners assessed the neighborhood and built environment,12,21–23,25,27–29 with concerns about the physical conditions of housing being the most common inquiry12,21,22,25,27–29 followed by violence and safety.12,21,23,27,28 Three screeners assessed social and community context,12,25,27,28 which included questions assessing concerns about immigration status,12,27,28 discrimination,25 religious or organizational affiliation,28 and social support.25,28 Of note, 4 screeners assessed protective factors under the social and community context and family context domains, including whether family members feel close,16 if the child has a relationship with a caring adult,23 religious or organizational affiliation,28 and if parents have social support.25,28

TABLE 3.

SDOH Domains

| Screening Tool | Economic Stability | Education | Health and Health Care | Neighborhood and Built Environment | Social and Community Context | Family Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ17–19,26 | Food insufficiency | — | Smoke alarm needed | — | — | Parental intimate partner violence |

| Contact information for Poison Control needed | Parental depression | |||||

| Parental stress | ||||||

| Parental drug or alcohol problems | ||||||

| Tobacco use in the home | ||||||

| Gun in the home | ||||||

| Help with the child is needed | ||||||

| iScreen12,27 | Food insufficiency | Concerns the child is not getting needed services | No or inadequate health insurance | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | Concerns about immigration status | Violence toward the child in the household |

| Housing instability | Lack of child care | Difficulty getting health care for the child | Transportation difficulties | Drug or alcohol problems in the household | ||

| Difficulty paying bills | Concerns about the child’s behavioral or mental health | Threats to the child’s safety at school or in the neighborhood | Incarceration of a household member | |||

| Trouble finding a job or other job-related problems | Concerns about their own mental health or mental health care | Difficulty getting benefits or services | Problems with child support or custody | |||

| Disability interfering with the ability to work | No regular health care provider | Concerns about finding activities for the child after school or in summer | ||||

| Difficulty getting assistance from income support programs | Concerns about child exposure to tobacco smoke | |||||

| Concerns about pregnancy-related work benefits | Concerns about the child’s physical activity | |||||

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool28 | Food insufficiency | Parental education | Parental physical activity | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | Concerns about immigration status | Parental intimate partner violence victimization |

| Housing instability | Concerns about the child’s learning or behavior in school | Parental fruit and vegetable consumption | Transportation difficulties | Religious or organizational affiliation | Parental stress | |

| Difficulty making ends meet or meeting basic needs | Concerns about neighborhood safety | Parental social support | Parental marital status | |||

| Parental employment | ||||||

| FMI16 | Food insufficiency | — | — | — | — | Child physical abuse |

| Housing instability | Child sexual abuse | |||||

| Child emotional abuse | ||||||

| Maternal intimate partner violence victimization | ||||||

| Mental illness in the household | ||||||

| Substance abuse in the household | ||||||

| Parental separation or divorce | ||||||

| Family members feel close | ||||||

| ASK Tool23 | Food insufficiency | Parental education | — | Child witnessed violence | — | Child physical abuse |

| Housing instability or difficulty paying bills | Lack of child care | Child experienced bullying | Child sexual abuse | |||

| Parental employment | Parental mental illness or substance abuse | |||||

| Need for legal aid | Child separation from caregiver | |||||

| Adult in child’s life who can comfort the child when sad | ||||||

| IHELP29 | Food insufficiency | Concerns about the child’s educational needs | Concerns about the child’s health insurance | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | — | Violence in household |

| Housing instability | ||||||

| WE CARE survey instrument11,24,30 | Food insufficiency | Parental education | — | — | — | Intimate partner violence in the household |

| Housing instability | Lack of child care | Parental depressive symptoms | ||||

| Difficulty paying bills | Alcohol abuse in the household | |||||

| Parental employment | Drug use in the household | |||||

| FAMNEEDS25 | Food insufficiency | Parental education | Help needed in getting health insurance | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | Parental experience of discrimination | Parental experience of violence |

| Housing instability | Help needed getting child care or care for elderly adult | Transportation problems that prevent health care visits | Parental social support | Parental depressive symptoms | ||

| Difficulty paying bills | Health literacy | Parental tobacco use | ||||

| Difficulty meeting basic needs | Parental alcohol use | |||||

| Help needed in getting public benefits | Parental drug use | |||||

| Help needed in finding a job | ||||||

| Unfairly fired from job Need for legal aid | ||||||

| Child ACE Tool20 | — | Parental education | — | — | — | Child maltreatment is suspected |

| Intimate partner violence in the household | ||||||

| Mental illness in the household | ||||||

| Substance abuse in the household | ||||||

| Household member is incarcerated | ||||||

| Parental marital status | ||||||

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record21 | Food insufficiency | — | — | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | — | Parental depressive symptoms |

| Difficulty making ends meet | Parent and child safety | |||||

| Difficulty getting assistance from income support programs | ||||||

| Health-Related Social Problems screener22 | Food insufficiency | — | Parent and child health insurance status | Concerns about physical conditions of housing | — | Parental intimate partner violence victimization |

| Housing instability | No regular health care provider | |||||

| Difficulty paying bills | Problems receiving health care | |||||

| Use of income support programs | ||||||

| Parental employment | ||||||

| Household income |

ASK, Addressing Social Key Questions for Health; FAMNEEDS, Family Needs Screening Program; FMI, Family Map Inventories; —, not assessed.

Follow-up Procedures

Table 4 depicts various follow-up procedures from the 17 studies in this review. Authors of only 4 studies reported no follow-up procedures after SDOH screening.18,20,21,27 Authors of 6 studies reported that screening results were discussed with caregivers, and referrals to community resources and outside agencies (eg, referrals to legal or transportation services) were offered and/or scheduled for caregivers but no intervention was delivered.11,17,19,23,24,28 Authors of 3 studies reported that referrals were offered and/or scheduled for caregivers without reporting that screening results were discussed with caregivers and without reporting that an intervention was delivered.22,29,30 Authors of only 3 studies reported that screening results were discussed with caregivers, referrals were offered and/or scheduled, and an intervention was delivered.12,25,26 Interventions came in the form of providers using motivational interviewing to engage caregivers26 and navigators being assigned to caregivers to help caregivers access and understand resources.12,25

TABLE 4.

Follow-up Procedures

| Screening Tool | Author and Year | Results Discussed | Referral Offered and/or Scheduled | Intervention Delivered | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEEK PSQ | Dubowitz et al18 2007 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Dubowitz et al17 2009 | X | X | — | Trained residents worked with parents to address identified problems, including providing parents with user-friendly handouts that detailed local resources, involving a SEEK social worker, and making referrals to community agencies. | |

| Dubowitz et al19 2012 | X | X | — | Health practitioners provided parents with handouts for identified problems (eg, substance abuse) customized with local agency listings. A licensed clinical social worker was available at each SEEK practice (either in person or by phone), and health practitioners and parents together decided whether to enlist the social worker’s help. The social worker provided support, crisis intervention, and facilitated referrals. | |

| Eismann et al26 2018 | X | X | X | Providers performed a brief intervention (~5–10 min) with caregivers who had a positive PSQ result using the reflect-empathize-assess-plan approach, which uses principles of motivational interviewing to help engage caregivers. Providers offered resources and referrals to caregivers on the basis of caregiver needs and desire for additional help. A social worker was available by phone to all practices for assistance with referrals. | |

| iScreen | Gottlieb et al27 2014 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Gottlieb et al12 2016 | X | X | X | After standardized screening, caregivers either received written information on relevant community services (active control) or received in-person help to access services with follow-up telephone calls for additional assistance if needed (navigation intervention). Navigators used algorithms to provide targeted information related to community, hospital, or government resources addressing needs caregivers had prioritized. Resources ranged from providing information about child-care providers, transportation services, utility bill assistance, or legal services to making shelter arrangements or medical or tax preparation appointments to helping caregivers complete benefits forms or other program applications. Follow-up meetings were offered every 2 wk for up to 3 mo until identified needs were met or when caregivers declined additional assistance. | |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Hensley et al28 2017 | X | X | — | After screening, at-risk results were cross-walked to a community resources guide built to identify local agencies and programs that addressed the social needs covered by the screening tool. Patients and families were offered assistance in making contact with the referred community resources as well as help in accessing other supportive services not listed in the community resources guide. |

| FMI | McKelvey et al16 2016 | — | — | X | All participants were screened at the time of implementation of home visiting programs (ie, 2-generation programs designed to serve at-risk families with children <5 years of age). Families included in the analysis voluntarily enrolled in 1 of 3 evidence-based home visiting models: Healthy Families America, Parents as Teachers, or Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters. |

| ASK Tool | Selvaraj et al23 2018 | X | X | — | After completing the ASK Tool, clinicians discussed the results with the caregiver. If ACEs and unmet social needs identified by the ASK Tool were substantiated and required intervention based on this discussion and clinician judgment, the physician referred caregivers to community resources using a developed resource lists. Consultation with the onsite social worker was available for families with multiple needs identified and/or significant social complexity |

| IHELP | Colvin et al29 2016 | — | X | — | After use of the IHELP tool, some interns provided referrals for a social work consultation. |

| WE CARE survey instrument | Garg et al24 2007 | X | X | — | Residents were instructed to review the WE CARE survey with the parent during the visit and make a referral if the parents indicated that they wanted assistance with any psychosocial problems. |

| Referrals came in the form of handing parents pages from the Family Resource Book with more information about 2–4 available community resources on 1 of 10 potential topics of concern identified in the screening. | |||||

| Garg et al11 2015 | X | X | — | Clinicians reviewed the WE CARE survey with mothers and offered them a 1-page information sheet with 2–4 free community resources for any needs for which the mother indicated she wanted assistance. The information sheets contained the program name, a brief description, contact information, program hours, and eligibility criteria. | |

| Zielinski et al30 2017 | — | X | — | Positive results on the screen triggered a social work referral at the time of the visit. | |

| FAMNEEDS | Uwemedimo and May25 2018 | X | X | X | When a need was identified on the screening tool, patient families who desired assistance were informed they would receive a follow-up phone call within 48 h from a resource navigator. Navigators provided families with contact information of social service providers and made e-referrals. Navigators continued to follow-up via phone with families who received referral information every 2 wk for 8 wk to assess progress on the referral or provide new information. A final follow-up call to assess the status of the referral was conducted at 3 mo after initial contact with the navigator. |

| Child ACE Tool | Marie-Mitchell and O’Connor20 2013 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported. |

| Social History Template of the Standard Well Child Care Form embedded in E-health Record | Beck et al21 2012 | — | — | — | No follow-up reported |

| Health-Related Social problems screener | Fleegler et al22 2007 | — | X | — | All participants received a referral sheet listing local agencies that could help with problems in each of the assessed social domains. |

ASK, Addressing Social key Questions for Health; FAMNEEDS, Family Needs Screening Program; FMI, Family Map Inventories; —, not assessed.

DISCUSSION

In the present review, we identified 11 unique SDOH screeners. Although we systematically searched databases from their inception dates, all articles that detailed screeners were published in the last 12 years. This growth of SDOH screening within the research literature in the last several years is paralleled by increasing attention to SDOHs within the medical community. Since the early 2000s, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other organizations have encouraged pediatric providers to develop standardized screening tools to assess social and behavioral risk factors that are relevant to their patient populations in an effort to identify and address risks.31–33 More recently, in 2018, North Carolina announced it will soon require Medicaid beneficiaries to undergo SDOH screening as part of overall care management, and more states may soon follow.34 Therefore, it is important to inventory the screening tools currently in use as well as assess their accuracy and impact on patient care. The majority of screeners identified in the present review were either validated, relevant to the priority population, or were accompanied by appropriate follow-up referrals or interventions, but a minority of screeners included all 3 qualities.

A central theme among screeners included in this review is the extent to which screening professionals (eg, primary care providers and social workers) can trust screening results. Only 3 out of the 11 screeners had been tested for reliability and/or validity; thus; we do not know the extent to which most tools accurately measured SDOHs.35 Several screening tool features may impact an informant’s ability to understand screening questions, thereby influencing the tools’ ability to correctly evaluate a child’s SDOHs. These features include the following questions: (1) Is the tool available in an informant’s language of fluency? (2) Is the tool at or below an informant’s reading level? and (3) Is the tool worded in such a way that the reference period for SDOHs is clear? The majority of reviewed screening tools were available in >1 language, and 3 of 7 tools that required informants to read were appropriate for low-literacy populations. However, a minority of screeners included a clear and single reference period for reporting SDOHs (ie, the reference period was not consistent across SDOHs assessed), and even fewer assessed SDOH chronicity or duration. Not only does information on the timing and duration of SDOH experiences guide interventions and referrals, but the reference period can influence the accuracy of informants’ reports; authors of previous research have found that reporting accuracy diminishes as the time between the experience of interest and the report increases.36–38 Additional research is required to identify which SDOH referent periods are the most appropriate for informing interventions and referrals while also simultaneously producing valid responses.

Informants’ ability to understand screening questions is necessary (but not sufficient) to obtain accurate screening results; informants must also answer truthfully. Parents and/or caregivers were the primary informants for all assessed tools; only 2 screeners triangulated information with a physician or social worker report. None included child self-report. Parents and caregivers often hold the most knowledge about their children’s experiences and social context; however, these informants may also be influenced by social desirability bias and fear of intervention with child protective services when answering questions about their children’s SDOHs.39,40 Furthermore, caregivers and children may simply disagree regarding the subjective assessment of the child’s health.41 Triangulating parent and/or caregiver reports with external data sources, however, requires additional resources that may be beyond the scope of many screening settings.

To overcome the barrier of caregiver and/or parent fear or social desirability, many screeners included in this review were developed in conjunction with information provided by community members, experts, and/or practice experience. For example, creators of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Parent Screening Questionnaire (PSQ) not only reviewed the research literature to prioritize amenable risk factors, but they also involved community pediatricians and parents in the development of the SEEK PSQ. On the basis of this method of development, the PSQ began with a statement that conveyed an empathetic tone toward caregivers, highlighted the practice’s concern about all children’s safety, and stated the practice’s willingness to help with any identified issues.18 Future research should conduct SDOH screening in tandem with a social desirability scale to empirically investigate if including empathetic language at the beginning of an SDOH screening tool allays concerns about social desirability bias.42

Because evidence is currently lacking on which specific SDOH factors have the largest impact on child health, the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children encourages pediatricians to tailor SDOH screening to their patients’ needs and available community resources.43 The majority of screeners included in this review followed this recommendation. For example, the Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE) screener only screened for SDOHs for which community resources were available.24 A criticism of screening children for ACEs is a lack of appropriate follow-up interventions when screening tools identify ACEs.5 We did not find evidence supporting this critique within studies in which SDOH screening was reported; the vast majority of studies followed screening with immediate referrals and/or interventions to address the identified SDOHs. What typically happens after ACE screening in practice is unknown. However, future research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these referrals and interventions in meeting family needs and improving child health and well-being. Moreover, few screeners assessed protective factors; thus, most follow-up interventions were deficit-based rather than strength-based. Given the evidence in support of strength-based interventions,44 future screening tools should incorporate the assessment of more protective factors.

Although we did not restrict our systematic search to clinical settings, all except 1 identified screener took place in either a pediatric clinic or hospital. Alternative settings, specifically educational settings, may be well-equipped to conduct universal SDOH screening. Trauma screening tools for use in educational settings exist and may be applied to select portions of student bodies.45 Universal SDOH screening, however, has not gained the same traction in educational settings that it has in medical settings, despite evidence that SDOHs can hinder optimal educational development and well-being.46,47

The present review contains limitations. First, SDOH definitions vary. We elected to follow the Healthy People 2020 definition, and doing so may have resulted in excluding articles that other SDOH definitions would have encompassed. Second, because we focused the review on SDOH measures, we did not collect information on outcomes; it is still unknown which SDOH domains impact child health and well-being the most. We believe these limitations, however, are offset by numerous strengths. First, our comprehensive search strategy allowed us to identify the SDOH screening tools that have been the subject of both research and practice. To our knowledge, we are also the first review of tools to assess both the psychometric properties of SDOH screening tools and the follow-up procedures that accompany the tools.

Many of the SDOH screening tools identified in this review included questions about SDOHs that were important to the given population and subsequently addressed identified SDOHs in an informed and appropriate manner. We did find, however, that the extent to which SDOH screening results accurately assess a child’s SDOHs as well as the extent to which the referrals and interventions offered after SDOH screening are effective are points for additional research. Although SDOH screening is increasing in popularity within medical settings, SDOH screening tool developers should consider creating tools for use in other childhood settings.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING:

This work was supported in part by an award to the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CE002479). Ms Doss was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32 HD52468). Ms Chandler was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32 HD007376).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACE

adverse childhood experience

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- PSQ

Parent Screening Questionnaire

- SDOH

social determinant of health

- SEEK

Safe Environment for Every Kid

- WE CARE

Well Child Care Evaluation Community Resources Advocacy Referral Education

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-2395.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. 2008. Available at: www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/. Accessed August 8, 2018

- 2.Services USDoHH. Social determinants of health. 2014. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed April 8, 2019

- 3.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):13–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA. 2016;316(8):813–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelhor D Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): cautions and suggestions. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;85:174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiscella K, Tancredi D, Franks P. Adding socioeconomic status to Framingham scoring to reduce disparities in coronary risk assessment. Am Heart J. 2009;157(6):988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb L, Fichtenberg C, Adler N. Screening for social determinants of health. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coker AL, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, et al. Effect of an in-clinic IPV advocate intervention to increase help seeking, reduce violence, and improve well-being. Violence Against Women. 2012; 18(1):118–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andermann A; CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17–18): E474–E483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schor EL. Maternal depression screening as an opening to address social determinants of children’s health. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8): 717–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/2/e296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(11):e162521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayan A, Raphael J, Rattler T, Bocchini C. Social Determinants of Health: Screening in the Clinical Setting. Houston, TX: The Center for Child Health Policy and Advocacy at Texas Children’s Hospital [Google Scholar]

- 14.Children’s Hospital Association. Screening for Social Determinants of Health: Children’s Hospitals Respond. Washington, DC: Children’s Hospital Association; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269, W64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKelvey LM, Whiteside-Mansell L, Conners-Burrow NA, Swindle T, Fitzgerald S. Assessing adverse experiences from infancy through early childhood in home visiting programs. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):858–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, et al. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):435–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK model of pediatric primary care: can child maltreatment be prevented in a low-risk population? Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marie-Mitchell A, O’Connor TG. Adverse childhood experiences: translating knowledge into identification of children at risk for poor outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(1):14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AF, Klein MD, Kahn RS. Identifying social risk via a clinical social history embedded in the electronic health record. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(10): 972–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/6/e1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvaraj K, Ruiz MJ, Aschkenasy J, et al. Screening for toxic stress risk factors at well-child visits: the addressing social key questions for health study. J Pediatr. 2019;205:244.e4–249.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, et al. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3): 547–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uwemedimo OT, May H. Disparities in utilization of social determinants of health referrals among children in immigrant families. Front Pediatr. 2018; 6:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eismann EA, Theuerling J, Maguire S, Hente EA, Shapiro RA. Integration of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model across primary care settings. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(2):166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/6/e1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hensley C, Joseph A, Shah S, O’Dea C, Carameli K. Addressing social determinants of health at a federally qualified health center. Int Public Health J. 2017;9(2):189 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colvin JD, Bettenhausen JL, Anderson-Carpenter KD, et al. Multiple behavior change intervention to improve detection of unmet social needs and resulting resource referrals. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(2):168–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zielinski S, Paradis HA, Herendeen P, Barbel P. The identification of psychosocial risk factors associated with child neglect using the WE-CARE screening tool in a high-risk population. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(4): 470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schor EL; American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on the Family. Family pediatrics: report of the task force on the family. Pediatrics. 2003; 111 (6 pt 2):1541–1571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Council on Children With Disabilities; Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics; Bright Futures Steering Committee; Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner AS, Shonkoff JP; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/1/e224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Services NCDoHaH. Using Standardized Social Determinants of Health Screening Questions to Identify and Assist Patients with Unmet Health-Related Resource Needs in North Carolina. 2018. Available at: https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/SDOH-Screening-Tool_Paper_FINAL_20180405.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2019

- 35.DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Stockwell T, Vallance K, Chow C. Recall bias across 7 days in self-reported alcohol consumption prior to injury among emergency department patients. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(3):382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ, Wallace JM. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2004;92(suppl 2):S213–S222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fendrich M, Johnson T, Wislar JS, Nageotte C. Accuracy of parent mental health service reporting: results from a reverse record-check study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999; 38(2):147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falletta L, Hamilton K, Fischbein R, et al. Perceptions of child protective services among pregnant or recently pregnant, opioid-using women in substance abuse treatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;79:125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feinberg E, Smith MV, Naik R. Ethnically diverse mothers’ views on the acceptability of screening for maternal depressive symptoms during pediatric well-child visits. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):780–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanier P, Guo S, Auslander W, et al. Parent–child agreement of child health-related quality-of-life in maltreated children. Child Indic Res. 2017;10(3): 781–795 [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Mortel TF. Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;25(4): 40–48 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez M Screening for Social Determinants of Health. Columbus, OH: The American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghielen STS, van Woerkom M, Meyers MC. Promoting positive outcomes through strengths interventions: a literature review. J Posit Psychol. 2018;13(6):573–585 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eklund K, Rossen E, Koriakin T, Chafouleas SM, Resnick C. A systematic review of trauma screening measures for children and adolescents. Sch Psychol Q. 2018;33(1):30–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maggi S, Irwin LJ, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. The social determinants of early child development: an overview. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(11):627–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012; 379(9826):1641–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.