Abstract

In the present study, the effect of the static and alternating magnetic field applied individually and in combination with an algal extract on the germination of soybean seeds (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) and chlorophyll content was examined. The exposure time of seeds to the static magnetic field was 3, 6, and 12 min, whereas to the alternating magnetic field was 1, 2.5, and 5 min. The static magnetic field was obtained by means of a permanent magnets system while the alternating magnetic field by means of magnetic coils. Algal extract was produced from a freshwater macroalga—Cladophora glomerata using ultrasound homogenizer. In the germination tests, 10% extract was applied to the paper substrate before sowing. This is the first study that compares the germination of soybean seeds exposed to the static and alternating magnetic field. The best effect on the germination and chlorophyll content in seedlings had synergistic action of the static magnetic field on seeds for 3 min applied together with the extract and alternating magnetic field used for 2.5 min. It is not possible to clearly state which magnetic field better stimulated the germination of seeds, but the chlorophyll content in seedlings was much higher for alternating magnetic field.

Keywords: algal extract, germination, soybean seeds, static and alternating magnetic field

Abbreviations

- AMF

alternating magnetic field

- Chl a

chlorophyll a

- GMF

geomagnetic field

- MF

magnetic field

- SMF

static magnetic field

- SPAD

soil plant analyses development

1. INTRODUCTION

From Fabaceae group of plants, soybean (Glycine max) cultivation is gaining popularity, which results from the possibility of its versatile usage not only in food industry but also fodder 1, 2, 3, 4, chemical 5, 6, or pharmaceutical one 7. Soybean is one of the most economically and nutritionally valuable agricultural commodities worldwide. Soybean meal has been used primarily for animal feed, whereas the oil has been consumed as edible oil. More recently, soybean has become a major component of food for human consumption, partly because it contains several highly valued oil and meal constituents with specific health‐enhancing properties 8. This trend has led to a shift in the focus from commodity soybean with high protein and oil yields to speciality soybean with novel and wider chemical profiles aimed at meeting the demands of the niche markets.

The development of value‐added oil crops and products for current and emerging niche markets appears an attractive alternative for breeders and producers 9. Soybean seed composition is a key issue in the development of speciality soybean intended for human nutrition. Although protein and oil remain important, other components, such as unsaturated fatty acids, tocopherols, and isoflavones, become relevant in soy‐based food. Therefore, there is high need to increase soybean production in Europe remembering about faster germination ability of cultivated plants.

As seeds are one of the most important sources of production, and their quality has an impact on agrotechnics and determines to a large extent the profitability of each crop, hence additional treatments to improve quality of seeds are sought 10. One of the possibilities, which can increase the germination ability of soybean seeds, as well as the resistance to the biotic and abiotic stress is exposing them to the algal extracts or/and static/alternating magnetic field (SMF and AMF, respectively).

Algal extracts belong to one of the groups of biostimulants of plant growth, which according to the definition are “substances applied to plants with the aim to enhance nutrition efficiency, abiotic stress tolerance and/or crop quality traits, regardless of its nutrients content” 11. Bio‐farming using seaweeds has been practiced from ancient time 12, 13. Seaweeds are known to be a rich source of macronutrients and trace elements necessary for the growth and enhancement of the plants. Moreover, macroalgae possess the ability to enhance seed germination, they impart resistance to frost, fungal, and insect attack, increase the nutrient uptake from soil, and are also used as good soil conditioners 14, 15. Bioassays aimed to evaluate the plant growth promoting effect of seaweed extracts have shown that the beneficial effect of these extracts is due to synergetic activity of plant growth‐promoting substances or hormones present in seaweeds 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. Marine algae are rich in potassium (K) and contain many growth promoters such as auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins. Moreover, in the literature it was shown that extracts produced from green macroalgae increased the germination percentage of soybean seeds, growth and yield, nutrient uptake, biochemical parameters (carbohydrates, proteins, phenols), and pigment content (chlorophyll, carotenoids), for example, Cladophora glomerata 23, Ulva fenestrata, Codium fragile 24, 25, and Enteromorpha intestinalis 26. One of the weaknesses of seaweeds is their capacity to accumulate several toxic metals, such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), etc. 27, 28. Beside this, high salinity, especially of marine seaweeds can also limit plant growth and development 29. These aspects should be taken into account when algae are considered as a raw material for the production of bio‐products for agriculture.

The increase of the soybean yield can also be achieved by the use of seeds of a good quality and their proper preparation before sowing. In the literature, there are more and more reports on the stimulation of plants with physical factors 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. Their use creates new opportunities to stimulate plant material for growth. Presowing seed treatment methods stimulate physiological and biochemical changes in seeds 35. Such stimulation methods are considered safe for the environment (according to the literature 36, 37, 38, 39). Among these methods one should mention the stimulation of seeds by ionizing radiation; laser; infrared; UV, ultrasounds; microwaves; and electric, magnetic, and electromagnetic fields. However, these tests usually relate to the use of one factor with different exposure times or parameters. In this research, the impact of various physical factors on soybeans, as well as different exposure times and the size of a magnetic field (MF) were examined. The influence of the MF on seeds does not pose any threat to the environment and increases the efficiency of physiological processes. The effect of this action is greater vigor and a higher level of yield 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION

Soybean is known as an essential plant protein around the world, usable as a food for humans and also as a valuable animal feed. From the agronomic standpoint, soy as a leguminous plant is highly desirable in crop rotation because of the beneficial effects on the soil and sequential plants. Therefore, nowadays there is a rapidly growing demand for soybean which is not genetically modified. The faster germination ability of soybean seeds, as well as the increase of the yield is the key issue. One of the possibilities is the stimulation of soybean seeds before sowing. This can be achieved by the use of algal extracts. A second group of stimulation methods is a static and alternating magnetic field. The methods that are presented in this publication are safe for the environment and can eliminate chemical growth regulators in the future.

It can be concluded from the available literature that the effect of the MF on biological objects is manifold: (1) electrodynamic interaction with electric currents occurring in organisms (Lorentz force and Hall effect), (2) formation of magneto‐mechanical effects inside organisms based on the orientation of structures with magnetic anisotropy in homogeneous fields and on the shifting of ferromagnetic and paramagnetic substances in fields with non‐zero gradients, (3) some components of living organisms have magnetostrictive properties; there is therefore the possibility of affecting such components, (4) influence on the uncompensated magnetic spins of paramagnetic elements and free radicals, (5) Dorfman effect which consists in the reorientation of proteins in the magnetostatic field due to the anisotropy of these molecules, (6) AMF causes induction currents inside living organisms, (7) MF changes the energy of intra‐ and interatomic interactions in living organisms, (8) MF can influence the depolarization of cells; resonant phenomena due to MF penetration may occur not only in the extracellular space, but also in the cell membrane (also in the ion channels) and inside the cell, (9) the MF also affects water which under the influence of an external MF changes its properties: the rate of crystallization increases, concentration of dissolved gases increases, and the rate of coagulation and settling of slurries also increases; pH and wetting properties change 30, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56.

The aim of the present study was to check if the SMF or AMF applied individually to the seeds and then together with the algal extract can stimulate the soybean (Glycine max) germination ability, as a consequence faster emergence what will result in better and uniform plant yielding. Additionally, the effect of the type of MF, that is, SMF or AMF was compared.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Soybean seeds

Soybean seeds (Glycine max), cv. Merlin, (not genetically modified) of uniform size were used in the present study. The parameter of “1000 seeds weight” of the tested seeds was 150 g. The seeds came from harvest in 2018 and they were certified.

2.2. Freshwater macroalga

A freshwater macroalga—Cladophora glomerata was collected by hand from the surface of the pond in a village Tomaszówek (Łódź Province, Poland) in October 2016. The collected algae were identified based on morphological characteristics according to taxonomic literature for the area 29. Then, the biomass was air‐dried and finally milled using a grinding mill (Retsch GM300, Haan, Germany). For the production of algal extract, the biomass with the particle size lower than 400 µm (sieve analysis) was chosen 23.

2.3. Production of the algal extract

Algal extract (E) was produced according to the methodology described by Michalak et al. (2018). Briefly, dry algae (4 g) suspended in an aqueous solution (100 mL) were subjected to the ultrasound homogenizer working at parameters 50 W, ultrasonic frequency 30 kHz, amplitude 100% (UP 50H; Hielscher Ultrasonics, Teltow, Germany). After 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at a speed rate 4000 rpm for 10 min. The obtained supernatant was treated as 100% algal extract 23. As the algal extract contained organic matter, a fresh portion was produced before germination tests and stored in a refrigerator.

2.4. The application of SMF and AMF on soybean seeds

The aim of the conducted research was to determine the influence of the SMF and AMF on the growth process of soybean seeds. Stimulation with a MF was carried out using MF‐SMF with an induction of 400 mT and MF‐AMF with a frequency of 50 Hz and an induction of 30 mT. The MF was obtained by means of magnetic coils. During stimulation, for SMF, the exposure times of 3, 6, and 12 min were used, whereas for a variable MF the exposure times of 1, 2.5, and 5 min were used. Differences in the exposure times result from literature reports and are close to those in which the best positive effects were recorded 36, 39, 43, 57, 58, 59, 60.

2.5. Germination tests

For germination tests, seeds stimulated by SMF, AMF, and 10% algal extract (prepared by the dilution in distilled water of the initial 100% algal extract, according to our previous research) were used 23. The experimental groups tested in this study are presented below, where, C is the control group, SMF is the static magnetic field, 3, 6, 12 are the exposure time (min) to SMF, AMF is the alternating magnetic field, 1, 2.5, 5 are the exposure time (min) to AMF, and E is extract (10%).

|

|

The germination test of soybean seeds was based on the International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) regulations. A paper substrate was used to conduct the germination test which was carried out in four replications. One replication consisted of 100 soybean seeds. In the groups treated with the extract, a 10% algal solution (240 mL for each replication) was added directly to the paper substrate before soybean seeds were sown. After the treatment, the tested seeds were stored in a growth chamber at a constant temperature of 25°C.

The first counting (energy of seedlings) was done after 5 days and the second one (germination of seedlings) after 8 days. After germination test, the seedlings were assessed and divided into normal and abnormal groups. Next, all seedlings were stored in a freezer at −21°C temperature to estimate their chlorophyll content.

The seedling is normal, when the primary root is undamaged or has minor damage in the form of discoloration, spots, cracks, or splits. Besides, a seedling can be classified as normal when the primary root is damaged/missing, but normal secondary roots are sufficiently developed. Hypocotyl and epicotyl of seedlings are undamaged or small defects are allowed: discoloration or necrotic spots, surface cracks, and loose sprains. The cotyledons are undamaged or have small defects (according to the current 50% rule, no more than 50% of the total surface may be damaged), there may be three cotyledons or only one normal cotyledon, provided that it is not damaged. The first leaves are undamaged or have small defects (according to the current 50% rule, no more than 50% of the total surface may be damaged), there may be three leaves or only one normal leaf provided it is not damaged. The top bud must be undamaged. A seedling is defined as abnormal if it is deformed, broken, white or yellow, glassy, or rotten as a result of primary infection.

2.6. Chlorophyll measurements

For the measurement of the chlorophyll content in soybean seedlings (cotyledons), a handheld SPAD‐502 Chlorophyll Meter (Konica Minolta, Japan) (SPAD: soil‐plant analyses development) was used. It provides a relative index of chlorophyll content in seedlings. In each experimental group and in each repetition (N = 4), 10 measurements were made from randomly selected seedlings 61. The average value and SD were calculated.

2.7. Physiochemical analysis of algal extract

The colour of algal extract was evaluated visually. The pH of 100% algal extract and diluted (10%) was measured with pH meter Mettler‐Toledo (Seven Multi; Greifensee, Switzerland) equipped with an electrode InLab413 with compensation of temperature. The multielemental analysis of the raw algal biomass and extracts (diluted 10% and final 100%) was performed using ICP‐OES technique (inductively coupled plasma‐optical emission spectrometry). For this reason, Varian VISTA‐MPX ICP‐OES apparatus (Victoria, Australia) was used. Analyses were performed in the Chemical Laboratory of Multielemental Analysis at Wrocław University of Science and Technology, accredited by International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation Mutual Recognition Arrangement and Polish Centre for Accreditation (No AB 696). In the case of algal biomass, before analysis (0.5 g) it was digested with 5 mL of 69% HNO3 (Suprapur, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in a microwave oven StartD (Milestone MLS‐1200 MEGA, Bergamo, Italy), and then diluted to 50 g with distilled water. For extract, the ratio was as follows: 10 mL of extract and 5 mL of 69% HNO3. After mineralization, the solution was diluted with distilled water to 50 g.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The obtained results were elaborated statistically by Statistica ver. 12.0 (TIBCO Software Inc.,Tulsa, OK, USA). Descriptive statistics (average, standard deviations) for all experimental groups was performed. The normality of the distribution of experimental results was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test and the homogeneity of variances by the Brown and Forsythe test. The differences between groups were determined with the one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Tukey multiple comparison test (for normal distribution and the homogeneity of variances). If the conditions about normal distribution and the homogeneity of variances were not met, Kruskal‐Wallis test (nonparametric test) was used. The results were considered significantly different when p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Characteristics of algal extract

The obtained C. glomerata extract, used in our experiments, is a water‐soluble extract with greenish‐brown colour. The pH of the 100% extract was 7.5 (for 10% concentration it was 8), which was comparable to the pH of other extracts obtained from algae, for example, the pH of extract from brown Sargassum wightii was 6.26 and from green Caulerpa chemnitzia was 7.2 (both obtained by boiling seaweeds in distilled water for 1 h) 62. Hernandez‐Herrera et al. (2014) measured the pH of extracts obtained by stirring of seaweeds in distilled water for 15 min and then autoclaving at 121°C for 1 h. The pH of the extract from green Ulva lactuca ranged from 7 to 7.4 (for concentrations 0.2, 0.4, and 1%), from green Caulerpa sertularioides ranged from 6.7 to 7, from brown seaweeds (Padina gymnospora) ranged from 7.1 to 7.6, and from Sargassum liebmannii ranged from 6.2 to 6.4 63.

The value of macroalgae as fertilizers or biostimulants of plant growth results from the content of macroelements, trace elements, and other metabolites. These compounds are necessary for the plants growth and enhancement 26. Therefore, it can be assumed that produced from macroalgae extract will be a concentrated form of biologically active compounds. Table 1 presents the multielemental composition of the raw algal biomass, Cladophora glomerata, as well as the obtained algal extract.

Table 1.

The multielemental composition of the raw algal biomass (mg/kg dry mass) and the algal extract (mg/L) (N = 2)

| mean ± SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element/Wavelength | Biomass of C. glomerata | C. glomerata extract (100%) | C. glomerata extract (10%) | C. glomerata extract (100%a) |

| Al/308.215 | 234.8 ± 4.8 | 0.7320 ± 0.3352 | <LOD | n.a. |

| Ba/455.403 | 93.64 ± 1.04 | 0.1767 ± 0.0018 | 0.05168 ± 0.00191 | n.a. |

| Ca/315.887 | 159 915 ± 3259 | 185.6 ± 3.4 | 39.71 ± 0.80b | 31.6 ± 4.7 |

| Cr/267.716 | 0.5379 ± 0.2876 | 0.02340 ± 0.01483 | 0.01852 ± 0.01404 | n.a. |

| Cu/324.754 | 4.514 ± 0.306 | 0.1726 ± 0.0026 | 0.1808 ± 0.0349 | 0.0453 ± 0.0113 |

| Fe/259.940 | 582.1 ± 3.2 | 4.285 ± 0.097 | 0.9050 ± 0.1012 | 0.388 ± 0.058 |

| K/766.491 | 23 417 ± 105 | 829.7 ± 7.9 | 85.22 ± 1.16b | 240 ± 36 |

| Mg/285.213 | 1 910 ± 12 | 28.92 ± 0.87 | 5.927 ± 0.085b | 5.99 ± 0.90 |

| Mn/257.610 | 137.8 ± 0.2 | 1.314 ± 0.0074 | 0.1449 ± 0.0033 | 0.194 ± 0.029 |

| Na/588.995 | 632.5 ± 11.6 | 23.06 ± 1.23 | 5.439 ± 0.985b | 7.07 ± 1.06 |

| P/213.618 | 929.5 ± 2.3 | 19.87 ± 0.08 | 0.7698 ± 0.0860b | 6.51 ± 0.98 |

| S/181.972 | 13 902 ± 1 118 | 220.2 ± 0.8 | 22.61 ± 0.04b | 49.6 ± 7.4 |

| Zn/213.857 | 22.22 ± 1.85 | 0.2614 ± 0.0442 | 0.1392 ± 0.0294 | 0.876 ± 0.131 |

The nutrient analysis of freshwater macroalga showed the presence of macroelements, Ca, K, Mg and Na, as well as microelements such as Cu, Mn, Zn, etc. This content was much higher than for other green seaweed, for example, Ulva lactuca, collected from the coastal area of Jalisco, Mexico (Na 77.7 mg/kg, K 18.5 mg/kg, Ca 18.8 mg/kg, and P 1 mg/kg) 63 and for Ulva intestinalis from the coastal area of Llantwit Major beach, South Wales, where the content of Ca was 37 046 mg/kg and of K 16 466 mg/kg 64. The content of Mg and Na in Ulva intestinalis in the work of Ghaderiardakani et al. (2019) was much higher (Mg 14 291 mg/kg and Na 61 861 mg/kg; these two elements dominate in the composition of marine water) 64 than for the tested freshwater C. glomerata. Freshwater macroalga can be recommended as a raw material for the production of biostimulants of plant growth. The differences in the elemental composition of macroalgae can result from different locations of their harvesting, different climatic conditions, as well as different analytical techniques, for example, atomic absorption spectrophotometry 63 and inductively coupled plasma‐MS 64 used for determination of the composition.

The relation and the multielemental composition of the raw algal biomass and the produced extract are randomly studied in the literature. Sivasankari et al. (2006) presents the content of Mg, Na, K, P, Fe, S, Si, Zn, Cu in the extract, obtained by boiling of green Caulerpa chemnitzia in distilled water for an hour 62. The content of Ca was comparable for both extracts (from C. chemnitzia and C. glomerata), whereas the content of Cu, Mg, Na, and Zn was higher in C. chemnitzia and Fe, K, S higher in C. glomerata. Much higher concentrations of elements in the algal extracts than in our work were presented by Rathore et al. (2009) 65. Authors examined the extract obtained by homogenization of red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii by grinder and then filtration. The content of macroelements was as follows: P 34 mg/L, Ca 460 mg/L, Mg 581 mg/L, S 600 mg/L, Na 5 100 mg/L, and K 19 700 mg/L, whereas the content of microelements was equal to 0.3 mg/L for Cu, 0.6 mg/L for Zn, 2.5 mg/L for Mn, and 10.6 mg/L for Fe 65. Higher concentrations of elements in the extract can result not only from the algae species, but also applied extraction method. The choice of the algal biomass and production technique should therefore depend on the plant species for which biostimulants will be applied.

In Table 1 we also compared the multielemental composition of C. glomerata extract produced by two different methods, ultrasound homogenizer (present study) and shaking of C. glomerata in distilled water for 1 hour at 200 rpm 23. It can be seen that the first method is more efficient considering the extraction of micro‐ and macroelements. For example, the content of Ca was almost six times higher for homogenization than for shaking, Fe 11 times higher, Mn ∼7 times higher, Mg ∼5 times higher, S ∼4.5 times higher, Cu ∼4 times higher, K ∼3.5 times higher, Na and P ∼3 times higher.

3.2. Germination tests

For the germination tests, soybean (Glycine max) was used as a model plant because nowadays it is a famous crop, cultivated worldwide due to its high protein and fat content and also other nutritional compounds. What is more, the world population is increasing and a sufficient supply of food is a fundamental issue for both the world and each individual country.

In the present research, soybean seeds before sowing were subjected to physical (magnetic field) and biological–chemical (algal extract) factors. Germination tests of soybean seeds lasted for 8 days. After this period, the seedlings were assessed and divided into normal and abnormal. The example of the normal and abnormal soybean seedling is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Abnormal and (B) normal soybean seedling. Source: S. Lewandowska

3.2.1. Effect of SMF and algal extract on seed germination

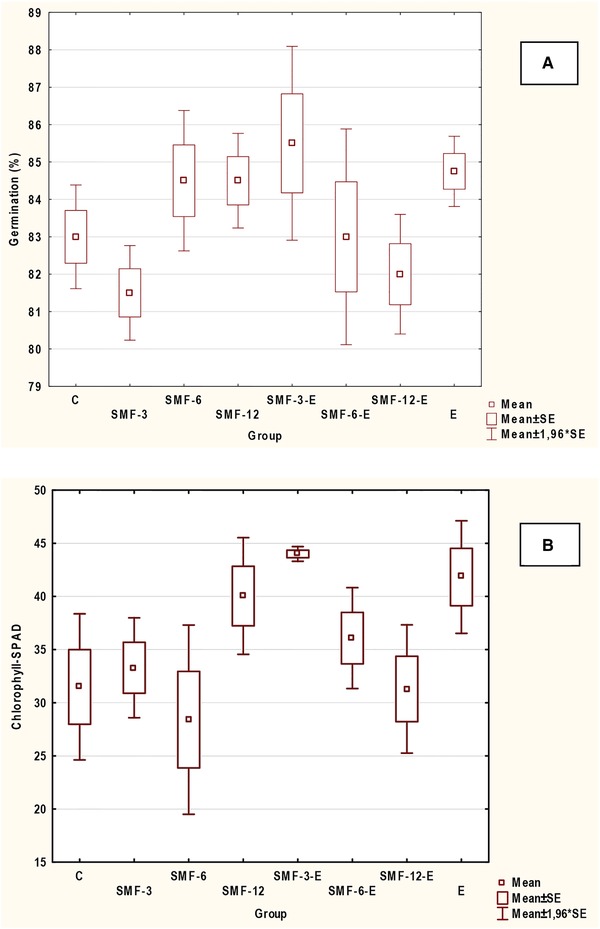

Table 2 presents the results from the germination tests, in which soybean seeds were treated with the SMF and algal extract. No statistically significant differences (for p < 0.05) were observed between tested groups and examined parameters—germination percentage, the number of abnormal seedlings, and chlorophyll content in cotyledons. The number of germinated seeds was comparable in all groups, but was the highest in a group SMF‐3‐E (the effect of the lowest exposure time together with extract) (Figure 2A).

Table 2.

The effect of the SMF and algal extract on the germination of soybean seeds and number of abnormal seedlings (N = 4)

| Germination | Abnormal seedlings | Chlorophyll | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (SPAD) | SD | |

| (1) | C | 83 | 1 | 17 | 2 | 31.5 | 7.0 |

| (2) | SMF‐3 | 82 | 1 | 19 | 1 | 33.3 | 4.8 |

| (3) | SMF‐6 | 85 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 28.4 | 9.1 |

| (4) | SMF‐12 | 85 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 40.0 | 5.6 |

| (5) | SMF‐3‐E | 86 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 44.0 | 0.7 |

| (6) | SMF‐6‐E | 83 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 36.1 | 4.8 |

| (7) | SMF‐12‐E | 82 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 31.3 | 6.2 |

| (8) | E | 85 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 41.8 | 5.4 |

Figure 2.

(A) The comparison of the percentage of germinated seeds and (B) chlorophyll content in soybean seedlings in tested groups (SMF)

Larger differences, for the soybean seeds treated with SMF and algal extract, were observed for the chlorophyll content (Figure 2B). Chlorophyll content measured by SPAD device was higher than in the control group for the following groups: SMF‐3, SMF‐12, SMF‐3‐E, SMF‐6‐E, and E. Chlorophyll content in seedlings from group SMF‐3 was by 6% higher than in the control group, in SMF‐6‐E by 15% higher, in SMF‐12 by 27% higher, in E by 33% higher, and in SMF‐3‐E by 40% higher, however according to the Kruskal‐Wallis test (lack of normal distribution), differences were not statistically significant (p < 0.05).

3.2.2. Effect of the AMF and algal extract on seed germination

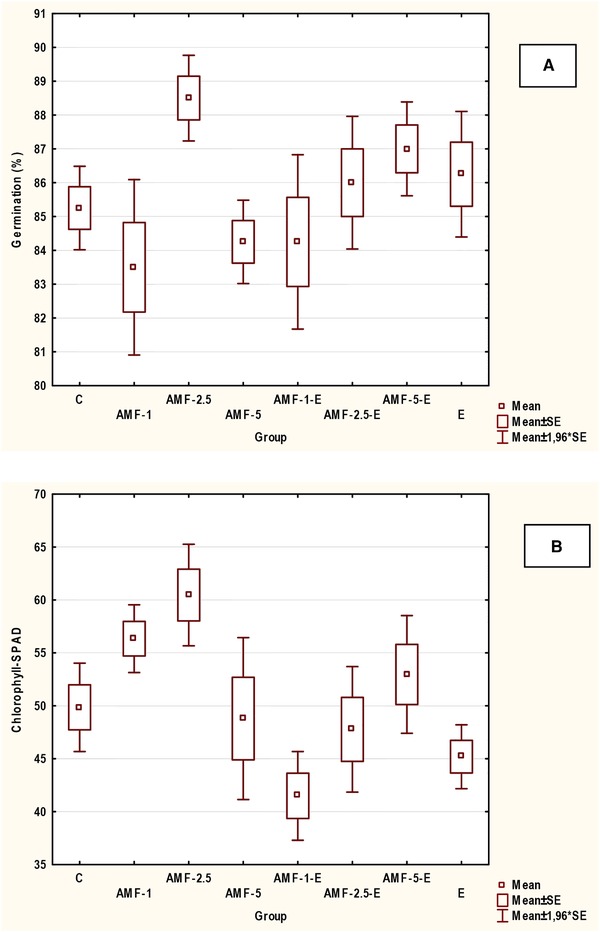

Table 3 presents the results from germination tests in which soybean seeds were treated with the AMF and algal extract. The distribution of experimental results was other than normal, therefore Kruskal‐Wallis test was used. No statistically significant differences (for p < 0.05) were observed between tested groups and germination percentage. The number of germinated seeds was comparable in all groups, but was the highest in group AMF‐2.5 (Figure 3A). In the case of the number of abnormal seedlings, the statistically significant difference was observed between AMF‐1 and AMF‐2.5 (p = 0.0194).

Table 3.

The effect of the AMF and algal extract on the germination of soybean seeds and number of abnormal seedlings (N = 4)

| Germination | Abnormal seedlings | Chlorophyll | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | SD | Mean (SPAD) | SD | |

| (1′) | C | 85 | 1 | 13 | 2 | 49.9 | 4.3 |

| (2′) | AMF‐1 | 84 | 3 | 16a | 2 | 56.3 | 3.3 |

| (3′) | AMF‐2.5 | 89 | 1 | 10a | 2 | 60.5a | 4.9 |

| (4′) | AMF‐5 | 84 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 48.8 | 7.8 |

| (5′) | AMF‐1‐E | 84 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 41.5a | 4.3 |

| (6′) | AMF‐2.5‐E | 86 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 47.8 | 6.0 |

| (7′) | AMF‐5‐E | 87 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 53.0 | 5.7 |

| (8′) | E | 86 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 45.2 | 3.1 |

Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05; Kruskal‐Wallis test).

Figure 3.

(A) The comparison of the percentage of germinated seeds and (B) chlorophyll content in soybean seedlings in tested groups (AMF)

Chlorophyll content measured in cotyledons by SPAD device was higher than in the control group only for AMF‐1, AMF‐2.5, and AMF‐5‐E (Figure 3B). The highest value was obtained for AMF‐2.5 (only exposure to the AMF) which was 21% higher than in the control group and for AMF‐1 by 13% higher. In the case of the study of the synergistic effect of the AMF and algal extract on the chlorophyll content, in the group AMF‐5‐E it was higher by 6% than in the control group. The application of algal extract did not increase the content of chlorophyll in soybean seedlings. Statistically significant difference (p = 0.00960) was between AMF‐2.5 (the highest value of chlorophyll) and AMF‐1‐E (the lowest value).

Comparing results presented in Tables 2 and 3, it can be seen that the germination of soybean seeds in groups treated with algal extract was comparable for both experiments‐germination percentage 85 ± 1 for (8) and 86 ± 2 for (8′), chlorophyll content 41.8 ± 5.4 for (8) and 45.2 ± 3.1 for (8′). In the case of the control group, germination was comparable, but the chlorophyll content was much higher in (1′) than in (1). It is not possible to state clearly which MF, SMF or AMF, better stimulated the germination of soybean seeds, but in the case of chlorophyll content in seedlings, higher values were determined for AMF.

3.2.3. Stimulation of seeds germination by the MF

The effect of the MF on plant seeds has been researched and has been presented in literature in a very broad range of values of magnetic induction. In general, the value of MF induction can be divided into low MF and high MF, where the dividing line is the value of the induction of the Earth's MF 66, 67, 68, 69. During evolution, all organisms have undergone the action of the Earth's MF (also known as the geomagnetic field, GMF), which is a natural part of the environment. The GMF works continuously on living systems and affects many biological processes.

A significant number of scientific publications describe the impact of MFs on plants at a higher level than GMF. Basically, intensities the MF relate to values higher than 100 µT. Values in scientific experiments can reach very high levels of MF in the range of 500 µT to 15 T 66, 67. In literature, the attention is focused most on the seed germination of important crops, such as wheat, rice, and legumes (including, in particular, soybean). Stimulation of plants (including their seeds) with high MF values is described in the literature and carries many other physiological effects (plant reactions in terms of growth, development, photosynthesis, and redox status) 22, 30, 54, 70, 71, 72. Plant seeds were exposed to SMFs, typically from about 5 mT to several hundred mT for different exposure times 45, 46, 48, 51, 59, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77. Different intensities of the alternating MF (from several µT to even several hundred mT) for germination of seeds and the growth of seedlings of bean or wheat seeds in various conditions were also examined 32, 33, 34, 37, 42, 48, 78, 79, 80, 81. Usually, a sinusoidal variable MF with a frequency of 50–60 Hz was used in the research (frequency current in the power grid) 32, 60, 78, 82, 83, 84, 85.

Stimulation with a MF depends on many parameters, such as the type and intensity of the field, exposure time, and the species of the plant subjected to stimulation 36, 42, 46, 47, 70, 76, 86, 87, 88, 89. It is assumed that MF stimulation causes changes in the course of certain biochemical and physiological processes inside the seeds and plants which have a positive effect on the development and productivity of plants 33, 37, 40, 43, 58, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94. Improved seed respiration, increased photosynthesis, and enzyme activity are the result of MF effects 48, 49, 53, 55, 67, 72, 86, 95, 96, 97.

Scientific researches on the biological effects of MF, which have been conducted for many years, have shown that MFs can generate or change many different phenomena. Explanation of the various described effects is a major problem 47, 55, 68, 86. Recently, the following types of physical processes or models that underlie hypothetically the basic mechanisms of MF responses interaction in biological systems have been proposed: (a) models of classical and quantum oscillators; (b) a cyclotron resonance model; (c) interference of quantum states of bound ions and electrons; (d) coherent quantum excitations; (e) biological effects of torsion fields accompanying MF; (f) biologically active metastable states of liquid water; (g) free radical reactions and other “spin” mechanisms; (h) a parametric resonance model; (i) stochastic resonance as a strengthening mechanism in magnetobiology and other random processes; (j) phase transitions in biophysical systems displaying the order of liquid crystals; (k) bifurcation behavior of solutions of nonlinear chemical kinetics equations; (l) radiotechnical models, in which biological structures and tissues are presented as equivalent electrical circuits; (m) charged macroscopic vortices in the cytoplasm 66, 90, 98. At the same time, it can be expected that these concepts and models can be combined 49, 70, 99.

The results presented in this research partially confirm the stimulating effect of MF (especially AMF) on the germination and chlorophyll content in seedlings. This is completely in agreement with previous findings regarding the seeds of many plants 33, 59, 86, 92, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104. However, this applies to selected values of MF induction, exposure time, and frequency (for alternating fields). It is assumed that MFs affect the structure of the cell membrane, and thus increase their permeability and ion transport in ion channels, which in turn affects the activity of the metabolic pathway 99. Changes in the intracellular Ca2+ level and ionic current density in the cell membrane result in a change in the osmotic pressure, and thereby change the capacity of a cell tissue to absorb water 32, 50, 58, 87, 105. Khizenkov et al. (2001) also noticed the influence of a low frequency MF on the ionic permeability of the cell membrane 31, 50, 53, 54, 106, 107, 108.

The effects of MF use in relation to chlorophyll content have been documented for many plant species 58, 103, 109. Pre‐sowing plant stimulation with a constant or AMF resulted in the increase of chlorophyll a (Chl a). Polyphasic Chl a fluorescence transients from the samples that were treated with MF caused a higher fluorescence yield 30, 57, 110, 111, 112, 113. It was observed that the total soluble proteins of leaves showed increased intensities of the bands that are related to a larger subunit (53 KDa) and smaller subunit (14 KDa) of RuBisCo in plants whose seeds have been magnetically stimulated with an induction of more than 150 mT. As a result, it was shown that pre‐sowing magnetic treatment improves the accumulation of biomass in soybeans. Jan et al. (2015) in the article examined influence of the MF on growth and Chl a fluorescence of Lemna minor plants under controlled conditions in extreme geomagnetic environments of 150 mT 113. According to the authors, strong MF affects the increase of initial Chl a fluorescence and energy dissipation in tested plants 30, 111.

In our research, we note that lower doses of MF exposure result in better germination of seeds (this applies to both SMF and AMF). This is consistent with literature. Higher MF intensities and longer exposure times were found to be detrimental to soybeans because the germination rate and percentage of germination were reduced. This conclusion, repeatedly formulated in the literature, indicates that the internal energy of seeds reacts positively when there is a properly selected combination of MF strength and exposure time 72. Many authors indicate that the increased accumulation of water in seeds after magnetic exposure can activate germinating enzymes that accelerate germination in treated seeds 31, 40, 59, 75, 88, 114, 115. However, if the absorption of water is too fast, it may cause physical disruption of the seed tissue 30, 86, 102, 105, 116, which may be responsible for the low viability of seeds treated with MFs with higher induction and/or longer exposure times. Stimulation of seeds by means of MFs had an influence on the growth of the initial plants. This improvement in plant growth indicates the addition of biomass due to the increased carbon bond. These studies were confirmed in other scientific papers 114, 117, 118.

3.2.4. Stimulation of seeds germination by the algal extract

In the case of algal extracts, generally they stimulate the seeds germination, but it depends on many factors such as algae species, extraction method, concentration and chemical composition of extract, method of application, plant species, etc. The range of concentrations of algal extracts used in germinations tests is very wide, from very low, for example, 0.2, 0.4, and 1% for tomato 63 and 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1% for mung bean 119, to much higher, for example, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, and 15% for soybean 65; 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 100% for cowpea 62; 20, 40, 60 and 100% for soybean 26. In the literature it was shown that seeds treated with lower concentrations of algal extracts exhibited higher germination rates and germination percentage, while the higher extracts concentrations inhibited the germination, for example, above 40% for cowpea 62, above 0.01% for tomato and lettuce 120. In ref. [64], it was shown that Ulva extract concentrations above 0.1% inhibited germination and root growth of the model land plant (Arabidopsis thaliana). Taking into account wide ranges of applied algal extracts, a special attention should be paid to plant species, for which these extracts are designed. In the case of soybean, there are several publications concerning the effect of the algal extract concentration on the seeds germination and plant growth parameters. For soybean, different ranges of concentrations were tested, for example, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, and 15%—and the highest grain yield was noted for 15% algal extract 65; 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, and 15%—and the highest plant height, dry matter accumulation, seed weight were obtained for 15% 121; 50 and 100%—soybean germination percentage was comparable, 44 and 48%, respectively 23. In our previous study 23, it was shown that a higher concentration of C. glomerata extract (50 and 100%) inhibited germination of soybean seeds (in control group it was 85%). Basing on the literature data and our previous experience, we have chosen a 10% concentration of algal extract to test in the present study. However, it will be crucial to test in the future also other concentrations of extracts from Cladophora glomerata to choose the optimal one.

Beside the concentration of the algal extract, its chemical composition plays an important role in seed germination. In the literature it was shown that extracts from green macroalgae can be valuable for plants biologically active compounds. In the work of Hassan et al. (2008), the effect of acetone extract from green macroalga Ulva lactuca on tomato and lettuce germination percentage was examined 120. In both cases, lower concentrations 10 and 30 mg/L increased the germination percentage when compared to the control (by 21.5 and 5.8%, respectively), whereas higher 100 and 300 mg/L reduced this parameter. It was concluded that high concentration of phenolic compounds such as vanillin and p‐coumaric acid can enhance the growth of plants through the stimulation of metabolic processes such as biosynthesis of nucleic acids, chlorophyll, and increase of the antioxidant activity 120. Hernandez‐Herrera et al. (2014) tested the effect of aqueous extracts from macroalgae—green Ulva lactuca and Caulerpa sertularioides, brown—Padina gymnospora and Sargassum liebmannii on the germination of tomato. Germination was enhanced in the case of the application of extracts, especially from U. lactuca and P. gymnospora applied to seeds at low concentrations (0.2%), among other tested concentrations (0.4 and 1%). It was assumed that it can be due to the presence of growth‐promoting substances such as phytohormones (indole acetic acid, indole‐3‐butyric acid, cytokinins, gibberellins), amino acids, vitamins, and micronutrients 63. Sivasankari et al. (2006) showed that low concentrations of algal extracts obtained from brown seaweed, Sargassum wightii, and green seaweed, Caulerpa chemnitzia, applied to the cowpea seeds, promoted their germination and seedlings growth. Seeds before sieving were soaked for 24 h in extract (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 100%) and water. The greatest seed germination was found for 20% concentration and no germination was observed for concentrations higher than 50%. Again, the positive effect can be due to the presence of some growth promoting substances such as gibberellins, indoleacetic acid and indole‐3‐butyric acid, cytokinins, vitamins, micronutrients (Co, Cu, Fe, Mo, Mn, Ni, Zn), and amino acids 62. The results obtained by Castellanos‐Barriga et al. (2017) suggested that the addition of acid extracts from Ulva lactuca at low concentrations (0.2%) significantly enhanced mung bean (Vigna radiata) seed germination. The percentage of seed germination decreased with increase of the algal extract concentration, from 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 to 1% 119.

In the present research, we showed that there is a wide range of physical, biological, chemical factors that affect seed germination and they require further detailed research. This research should focus on the selection of the best parameters (time, induction for SMF, frequency, and induction for AMF, etc.) for seeds exposure to the MF, as well as selection of the best concentration of algal extract and its chemical characteristics, taking into account organic compounds.

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The application of the MF to the seeds together with algal extract can be considered by the growers in order to attain better seed germination. In the case of SMF, the best results in terms of germination percentage were obtained for the seed exposure for 3 min and the action of the algal extract (86.0 ± 3.0). For AMF, exposure of seeds for 2.5 min resulted in the highest germination percentage (89.0 ± 1.0). For the same groups, in both series of experiments, the highest content of chlorophyll was measured (by SPAD) in soybean seedlings (44.0 ± 0.7 and 60.5 ± 4.9, respectively). Slightly better results were obtained for the AMF. However, the future research on the mechanism of the action of MF and algal extract applied separately and together on plant growth should be performed. Additionally, optimization of the experimental conditions (exposure time, induction, frequency, concentration of algal extract) should be carried out, as well as detailed characteristics of algal extracts.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research concerning algal extract was co‐financed by statutory activity subsidy in 2018/2019 from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education for the Faculty of Chemistry of Wrocław University of Science and Technology (Department of Advanced Material Technologies), No 0401/0157/18.

Michalak I, Lewandowska S, Niemczyk K, et al. Germination of soybean seeds exposed to the static/alternating magnetic field and algal extract. Eng Life Sci. 2019;19:986–999. 10.1002/elsc.201900039

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee, H. , Garlich, J. D. , Effect of overcooked soybean meal on chicken performance and amino acid availability. Poult. Sci. 1992, 71, 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Engram, D. , Parsons, S. , Parsons, C. M. , Methods for determining quality of soybean meal important. Feedstuffs 1999, 4, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu, S. , Liu, X. , Wei, J. , Ma, L. , et al., Effects of different fermented soybean meals on growth performance and intestinal morphology in piglets. Feed Ind. 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Willis, S. , The use of soybean meal and full fat soybean meal by the animal feed industry. 12th Australian Soybean Conference , 2003, 1–8.

- 5. Biermann, U. , Friedt, W. , Lang, S. , Lhs, W. , et al., New syntheses with oils and fats as renewable raw materials for the chemical industry In: Biorefineries‐Industrial Processes and Products. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH; 2008. p. 253–289. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrera, C. S. , Dardanelli, J. L. , Soldini, D. O. , Chemical compounds related to nutraceutical and industrial qualities of non‐transgenic soybean genotypes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1463–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karczmarczuk, R. , Soja–roślina ze wszech miar użyteczna (in Polish). Wiadomości Zielar 1999, 41, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seguin, P. , Turcotte, P. , Tremblay, G. , Pageau, D. , et al., Tocopherols concentration and stability in early maturing soybean genotypes. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 1153. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vollmann, J. , Rajcan, I. , Oil crop breeding and geneticsIn: Vollmann J., Rajcan I, editors, Oil Crops. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2009. p. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewandowska, S. , Kozak, M. , Current situation of seed production in the south western part of Poland, in: Agricultura‐Scientia‐Prosperitas. Seed and Seedlings. Proceedings Papers, 2017, pp. 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 11. du Jardin, P. , Plant biostimulants: definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nedumaran, T. , Arulbalachandran, D. , Seaweeds: a promising source for sustainable development In: Environmental Sustainability. New Delhi, India: Springer; 2015. p. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nabti, E. , Jha, B. , Hartmann, A. , Impact of seaweeds on agricultural crop production as biofertilizer. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Venkataraman, K. V. , Mohan, R. , Murugeswari, R. , Muthusamy, M. , Effect of crude and commercial seaweed extracts on seed germination and seedling growth in green gram and black gram. Seaweed Res. Util. 1993, 16, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohan, V. R. , Venkataraman, K. V. , Murugeswari, R. , Muthuswami, S. , Effect of crude and commercial seaweed extracts on seed germination and seedling growth in Cajanus cajan L. Phykos 1994, 33, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leader‐Williams, N. , Scott, T. A. , Pratt, R. M. , Forage selection by introduced reindeer on south Georgia, and its consequences for the flora. J. Appl. Ecol. 1981, 18, 83. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tay, S. A. B. , Macleod, J. K. , Palni, L. M. S. , Letham, D. S. , Detection of cytokinins in a seaweed extract. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 2611–2614. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mooney, P. A. , van Staden, J. , Algae and cytokinins. J. Plant Physiol. 1986, 123, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rayorath, P. , Khan, W. , Palanisamy, R. , MacKinnon, S. L. , et al., Extracts of the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum induce gibberellic acid (GA3)‐independent amylase activity in barley. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 27, 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khan, W. , Rayirath, U. P. , Subramanian, S. , Jithesh, M. N. , et al., Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 386–399. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wally, O. S. D. , Critchley, A. T. , Hiltz, D. , Craigie, J. S. , et al., Regulation of phytohormone biosynthesis and accumulation in Arabidopsis following treatment with commercial extract from the marine macroalga Ascophyllum nodosum . J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 324–339. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jannin, L. , Arkoun, M. , Etienne, P. , Laîné, P. , et al., Brassica napus growth is promoted by Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. seaweed extract: microarray analysis and physiological characterization of N, C, and S metabolisms. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michalak, I. , Lewandowska, S. , Detyna, J. , Olsztyńska‐Janus, S. , et al., The effect of macroalgal extracts and near infrared radiation on germination of soybean seedlings: preliminary research results. Open Chem. 2018, 16, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anisimov, M. M. , Chaikina, E. L. , Effect of seaweed extracts on the growth of seedling roots of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) seasonal changes in the activity. Int. J. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev. 2014, 2, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaikina, E. L. , Dega, L. A. , Pislyagin, E. A. , Anisimov, M. M. , Effects of water soluble extracts from marine algae on root growth in soybean seedlings. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2015, 41, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mathur, C. , Rai, S. , Sase, N. , Krish, S. , et al., Enteromorpha intestinalis derived seaweed liquid fertilizers as prospective biostimulant for Glycine max . Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol. 2015, 58, 813–820. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Circuncisão, A. , Catarino, M. , Cardoso, S. , Silva, A. , Minerals from macroalgae origin: health benefits and risks for consumers. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michalak, I. , Chojnacka, K. , Algal compost – toward sustainable fertilization. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 33, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Starmach, K. , Family: Cladophora Kutzing 1843. identification key. [Translation from: Flora Słodkowodna Polski 10, 227–263, 1972], Freshwater Biological Association, Windermere, UK 1975.

- 30. Adey, W. R. , Biological effects of electromagnetic fields. J. Cell. Biochem. 1993, 51, 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Macrì, M. A. , di Luzio, d. , Luzio, S. , Biological effects of electromagnetic fields. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2002, 15, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matwijczuk, A. , Kornarzyński, K. , Pietruszewski, S. , Effect of magnetic field on seed germination and seedling growth of sunflower. Int. Agrophysics 2012, 26, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Podleśny, J. , Pietruszewski, S. , The effect of magnetic stimulation of seeds on growth and cropping of seed pea grown at varying soil moisture content (in Polish). Agric. Eng. 2007, 11, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atak, Ç. , Emiroğlu, Ö. , Alikamenğlu, S. , Razkoulieva, A. , Stimulation of regeneration by magnetic field in soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) tissue cultures. J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 2, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cieśla, A. , Skowron, M. , The analysis of the static magnetic field in paramagnetic spheroids at the laminar structure on the example grain wheat, In: ISEF’2007 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Fields in Mechatronics, Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Prague: 2007, p. 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pietruszewski, S. , Effects of magnetic biostimulation of wheat seeds on germination, yield and proteins. Int. Agrophysics 1996, 10, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pietruszewski, S. , Kania, K. , Effect of magnetic field on germination and yield of wheat. Int. Agrophysics 2010, 24, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aladjadjiyan, A. , Physical factors for plant growth stimulation improve food quality In: Food Production ‐ Approaches, Challenges and Tasks, IntechOpen, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewandowska, S. , Michalak, I. , Niemczyk, K. , Detyna, J. , et al., Influence of the static magnetic field and algal extract on the germination of soybean seeds. Open Chem. 2019, 17, 10.1515/chem-2019-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Anand, A. , Nagarajan, S. , Verma, A. P. S. , Joshi, D. K. , Pre‐treatment of seeds with static magnetic field ameliorates soil water stress in seedlings of maize ( Zea mays L.). Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 49, 63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grabowska, K. , Mech, R. P. , Zięty, A. , Detyna, J. , Selected aspects of research on biomechanical properties of plants (in Polish) In: Współczesna Myśl Techniczna w Naukach Medycznych i Biologicznych: VI Sympozjum. Wrocław: Oddział Polskiej Akademii Nauk we Wrocławiu; 2015. p. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grabowska, K. , Detyna, J. , Bujak, H. , Influence of alternating magnetic field on selected plants properties, In: Szrek J. editor, Interdyscyplinarność Badań Naukowych 2014: Praca Zbiorowa. Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej; 2014. p. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kavi, P. S. , The effect of magnetic treatment of soybean seed on its moisture absorbing capacity. Sci. Cult. 1977, 43, 405–406. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Niemczyk, K. , Influence of some stimulatory factors on growth, development and biomechanical properties of selected plants (in Polish), Wrocław University of Science and Technology, 2017.

- 45. Vashisth, A. , Joshi, D. K. , Growth characteristics of maize seeds exposed to magnetic field. Bioelectromagnetics 2017, 38, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vashisth, A. , Nagarajan, S. , Exposure of seeds to static magnetic field enhances germination and early growth characteristics in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Bioelectromagnetics 2008, 29, 571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cieśla, A. , Kraszewski, W. , Skowron, M. , Syrek, P. , The effects of magnetic fields on seed germination. Prz. Elektrotechniczny 2015, 91, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhadin, M. N. , Review of Russian literature on biological action of DC and low‐frequency AC magnetic fields. Bioelectromagnetics 2001, 22, 27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ueno, S. , Biological effects of magnetic fields. IEEE Transl. J. Magn. Japan 1992, 7, 580–585. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Adair, R. K. , Comment: influence of stationary magnetic fields on water relations in lettuce seeds. Bioelectromagnetics 2002, 23, 550; discussion 551–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rosen, A. D. , Studies on the effect of static magnetic fields on biological systems. PIERS Online 2010, 6, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krawczyk, A. , Bioelektromagnetyzm (in Polish), Instytut Naukowo‐Badawczy ZTUREK, Warszawa, Poland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barnes, F. S. , Mechanisms for electric and magnetic fields effects on biological cells. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 4219–4224. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Blanchard, J. P. , Modeling biological effects from magnetic fields. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 1996, 11, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Binhi, V. N. , Theoretical concepts in magnetobiology. Electro‐ and Magnetobiology 2001, 20, 43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cieśla, A. , Kraszewski, W. , Skowron, M. , Syrek, P. , Determination of safety zones in the context of the magnetic field impact on the surrounding during magnetic therapy. Prz. Elektrotechniczny 2011, 87, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shine, M. B. , Guruprasad, K. N. , Anand, A. , Enhancement of germination, growth, and photosynthesis in soybean by pre‐treatment of seeds with magnetic field. Bioelectromagnetics 2011, 32, 474–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Radhakrishnan, R. , Kumari, B. D. R. , Influence of pulsed magnetic field on soybean ( Glycine max L.) seed germination, seedling growth and soil microbial population. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 50, 312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kataria, S. , Baghel, L. , Guruprasad, K. N. , Pre‐treatment of seeds with static magnetic field improves germination and early growth characteristics under salt stress in maize and soybean. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pietruszewski, S. , Szecówka, P. S. , Kania, K. , Effect of pre‐sowing magnetic stimulation on germination of kernels of various spring wheat varieties. Acta Agrophysica 2013, 20, 415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rodriguez, I. R. , Miller, G. L. , Using a chlorophyll meter to determine the chlorophyll concentration, nitrogen concentration, and visual quality of St. Augustinegrass. HortScience 2000, 35, 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sivasankari, S. , Venkatesalu, V. , Anantharaj, M. , Chandrasekaran, M. , Effect of seaweed extracts on the growth and biochemical constituents of Vigna sinensis . Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1745–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hernández‐Herrera, R. M. , Santacruz‐Ruvalcaba, F. , Ruiz‐López, M. A. , Norrie, J. , et al., Effect of liquid seaweed extracts on growth of tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L.). J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 619–628. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ghaderiardakani, F. , Collas, E. , Damiano, D. K. , Tagg, K. , et al., Effects of green seaweed extract on Arabidopsis early development suggest roles for hormone signalling in plant responses to algal fertilisers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rathore, S. S. , Chaudhary, D. R. , Boricha, G. N. , Ghosh, A. , et al., Effect of seaweed extract on the growth, yield and nutrient uptake of soybean (Glycine max) under rainfed conditions. South African J. Bot. 2009, 75, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maffei, M. E. , Plant responses to electromagnetic fields, In: Greenebaum B., Barnes F., editors, Biological and Medical Aspects of Electromagnetic Fields, Fourth. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2019. p. 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Maffei, M. E. , Magnetic field effects on plant growth, development, and evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Occhipinti, A. , De Santis, A. , Maffei, M. E. , Magnetoreception: an unavoidable step for plant evolution? Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bertea, C. M. , Narayana, R. , Agliassa, C. , Rodgers, C. T. , et al., Geomagnetic field (Gmf) and plant evolution: investigating the effects of Gmf reversal on Arabidopsis thaliana development and gene expression. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 105, 53286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. da Silva, J. A. T. , Dobranszki, J. , Magnetic fields: how is plant growth and development impacted? Protoplasma 2016, 253, 231–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Starck, Z. , Chołuj, D. , Niemyska, B. , Physiological plant reactions to adverse factors environment. (in Polish), SGGW Publisher, Warszawa, Poland: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bhatnagar, D. , Deb, A. R. , Some effect of pre‐germination exposure of wheat seeds to magnetic fields: effect on some physiological process. Seed Res. (New Delhi) 1977, 5, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aladjadjiyan, A. , Study of the influence of magnetic field on some biological characteristics of Zea mais . J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2002, 3, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mahajan, T. S. , Pandey, O. P. , Magnetic‐time model at off‐season germination. Int. Agrophysics 2014, 28, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Thomas, S. , Anand, A. , Chinnusamy, V. , Dahuja, A. , et al., Magnetopriming circumvents the effect of salinity stress on germination in chickpea seeds. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 3401–3411. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Pietruszewski, S. , Kornarzyński, K. , Łacek, R. , Germination of wheat seeds in static magnetic field (in Polish). Inżynieria Rol. 2001, 5, 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhang, X. , Yarema, K. , Xu, A. , Biological effects of static magnetic fields, Springer Singapore, Singapore: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sujak, A. , Dziwulska‐Hunek, A. , Kornarzyński, K. , Compositional and nutritional values of amaranth seeds after pre‐sowing He‐Ne laser light and alternating magnetic field treatment. Int. Agrophysics 2009, 23, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Podleśny, J. , Misiak, L. , Podleśna, A. , Pietruszewski, S. , Concentration of free radicals in pea seeds after pre‐sowing treatment with magnetic field. Int. Agrophysics 2005, 19, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bujak, K. , Frant, M. , Influence of pre‐sowing seed stimulation with magnetic field on spring wheat yielding. Int. Agrophysics 2009, 14, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Iqbal, M. , Haq, Z. , Jamil, Y. , Ahmad, M. , Effect of presowing magnetic treatment on properties of pea. Int. Agrophysics 2012, 26, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Marks, N. , Szecówka, P. S. , Impact of variable magnetic field stimulation on growth of aboveground parts of potato plants. Int. Agrophysics 2010, 24, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zepeda‐Bautista, R. , Hernandez‐Aguilar, C. , Suazo‐Lopez, F. , Dominguez‐Pachecco, A. F. , et al., Electromagnetic field in corn grain production and health. African J. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Isaac Alemán, E. , Oliveira Moreira, R. , Almeida Lima, A. , Chaves Silva, S. , et al., Effects of 60Hz sinusoidal magnetic field on in vitro establishment, multiplication, and acclimatization phases of Coffea arabica seedlings. Bioelectromagnetics 2014, 35, 414–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Muszyński, S. , Gagoś, M. , Pietruszewski, S. , Short‐term pre‐germination exposure to ELF magnetic field does not influence seedling growth in durum wheat (Triticum durum). Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2009, 18, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Polk, C. , Biological effects of low‐level low‐frequency electric and magnetic fields. IEEE Trans. Educ. 1991, 34, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Reina, F. G. , Pascual, L. A. , Fundora, I. A. , Influence of a stationary magnetic field on water relations in lettuce seeds. Part II: experimental results. Bioelectromagnetics 2001, 22, 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vashisth, A. , Nagarajan, S. , Effect on germination and early growth characteristics in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) seeds exposed to static magnetic field. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Martinez, E. , Carbonell, M. V. , Amaya, J. M. , A static magnetic field of 125 mT stimulates the initial growth stages of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Electro‐ and Magnetobiology 2000, 19, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pietruszewski, S. , Influence of magnetic and electric fields on seeds germination of selected cultivated plants (in Polish). Acta Sci. Pol. Tech. Agrar. 2002, 1, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Martinez, E. , Carbonell, M. V. , Flórez, M. , Amaya, J. M. , et al., Germination of tomato seeds (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) under magnetic field. Int. Agrophysics 2009, 23, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Asgharipour, M. R. , Omrani, M. R. , Effects of seed pretreatment by stationary magnetic fields on germination and early growth of lentil. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Boe, A. A. , Salunkhe, D. K. , Effects of magnetic fields on tomato ripening. Nature 1963, 199, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Carbonell, M. V. , Martinez, E. , Amaya, J. M. , Stimulation of germination in rice (Oryza Sativa L.) by a static magnetic field. Electro‐ and Magnetobiology 2000, 19, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Es'kov, E. K. , Darkov, A. V. , Consequences of high‐intensity magnetic effects on the early growth processes in plant seeds and the development of honeybees. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2003, 30, 512–516. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kavi, P. S. , The effect of non‐homogeneous, gradient magnetic field on the magnetic susceptibility values of insitragi (Eleusinecoracana Gaertn) seed material. Mysore J. Agric. Sci. 1983, 17, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Aceto, H. , Tobias, C. , Silver, I. , Some studies on the biological effects of magnetic fields. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1970, 6, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lednev, V. V. , Possible mechanism for the influence of weak magnetic fields on biological systems. Bioelectromagnetics 1991, 12, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Labes, M. M. , A possible explanation for the effect of magnetic fields on biological systems. Nature 1966, 211, 968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Martínez, E. , Flórez, M. , Maqueda, R. , Carbonell, M. V. , et al., Pea (Pisum sativum, L.) and lentil (Lens culinaris, Medik) growth stimulation due to exposure to 125 and 250 mT stationary fields. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2009, 16, 657–663. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Aladjadjiyan, A. , The use of physical methods for plant growing stimulation in Bulgaria. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2007, 8, 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Iimoto, M. , Watanabe, K. , Fujiwara, K. , Effects of magnetic flux density and direction of the magnetic field on growth and CO2 exchange rate of potato plantlets in vitro. Acta Hortic. 1996, 606–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Turker, M. , Temirci, C. , Battal, P. , Erez, M. E. , The effects of an artificial and static magnetic field on plant growth, chlorophyll and phytohormone levels in maize and sunflower plants. Phyt. ‐ Ann. Rei Bot. 2007, 46, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Dicarlo, A. L. , Hargis, M. T. , Penafiel, L. M. , Litovitz, T. A. , Short‐term magnetic field exposures (60Hz) induce protection against ultraviolet radiation damage. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1999, 75, 1541–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Reina, F. G. , Pascual, L. A. , Influence of a stationary magnetic field on water relations in lettuce seeds. Part I: theoretical considerations. Bioelectromagnetics 2001, 22, 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Khizenkov, P. K. , Dobritsa, N. V. , Netsvetov, M. V. , Driban, V. M. , Influence of low and super low frequency alternating magnetic fields on ionic permeability of cell membranes. Dopv Nats Akad Nauk Ukr 2001, 4, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Goodman, R. , Chizmadzhev, Y. , Shirley‐Henderson, A. , Electromagnetic fields and cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 1993, 51, 436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kun, M. , Chan, C. , Ramakrishna, S. , Kulkarni, A. , et al., 12 ‐ Textile‐based scaffolds for tissue engineering, In: Rajendran S. editor. Advanced Textiles for Wound Care (Second Edition). Second edition, Woodhead Publishing, 2019, pp. 329–362. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Rochalska, M. , Influence of frequent magnetic field on chlorophyll content in leaves of sugar beet plants. Nukleonika 2005, 50, S25–S28. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Strasserf, R. J. , Srivastava, A. , Polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence transient in plants and cyanobacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. 1995, 61, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Govindje, E. , Sixty‐three years since Kautsky: chlorophyll a fluorescence. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1995, 22, 131–160. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Albert, K. R. , Mikkelsen, T. N. , Ro‐Poulsen, H. , Effects of ambient versus reduced UV‐B radiation on high arctic Salix arctica assessed by measurements and calculations of chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters from fluorescence transients. Physiol. Plant. 2005, 124, 208–226. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Jan, L. , Fefer, D. , Košmelj, K. , Gaberščik, A. , et al., Geomagnetic and strong static magnetic field effects on growth and chlorophyll a fluorescence in Lemna minor . Bioelectromagnetics 2015, 36, 190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Liu, S. , Kandoth, P. K. , Warren, S. D. , Yeckel, G. , et al., A soybean cyst nematode resistance gene points to a new mechanism of plant resistance to pathogens. Nature 2012, 492, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Krishnan, H. B. , Engineering soybean for enhanced sulfur amino acid content. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 454–461. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Powell, A. A. , Matthews, S. , The damaging effect of water on dry pea embryos during imbibition. J. Exp. Bot. 1978, 29, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Setiyono, T. D. , Cassman, K. G. , Specht, J. E. , Dobermann, A. , et al., Simulation of soybean growth and yield in near‐optimal growth conditions. F. Crop. Res. 2010, 119, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sun, J. , Nishio, J. N. , Vogelmann, T. C. , Green light drives CO fixation deep within leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998, 39, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Castellanos‐Barriga, L. G. , Santacruz‐Ruvalcaba, F. , Hernández‐Carmona, G. , Ramírez‐Briones, E. , et al., Effect of seaweed liquid extracts from Ulva lactuca on seedling growth of mung bean (Vigna radiata). J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hassan, S. M. , Ghareib, H. R. , Bioactivity of Ulva lactuca L. acetone extract on germination and growth of lettuce and tomato plants. African J. Biotechnol. 2008, 8, 3832–3838. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Lodhi, K. K. , Choubey, N. K. , Dwivedi, S. K. , Pal, A. , et al., Impact of seaweed saps on growth, flowering behaviour and yield of soybean [ Glycine max (L.) Merrill.]. The Bioscan 2015, 10, 479–483. [Google Scholar]