Abstract

Melanonychia is a very worrisome entity for most patients. It is characterized by brownish black discoloration of nail plate and is a common cause of nail plate pigmentation. The aetiology of melanonychia ranges from more common benign causes to less common invasive and in situ melanomas. Melanonychia especially in a longitudinal band form can be due to both local and systemic causes. An understanding of the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical details is necessary for adequate patient care and counseling. It not only helps in the early recognition of melanoma but also prevents unnecessary invasive work up in cases with benign etiology. An early diagnosis of malignant lesion is the key to favourable outcome. Though there are no established guidelines or algorithms for evaluating melanonychia, a systematic stepwise approach has been suggested to arrive at a probable etiology. We, hereby, review the aetiology, clinical features, diagnostic modalities and management protocol for melanonychia.

Keywords: Dermoscopy, longitudinal melanonychia, melanonychia, nail, onychoscopy, pigmentation

Definition

Melanonychia refers to the Greek word “Melas” meaning black (or brown colour) and “Onyx” meaning nail. It is characterized by brown-black discoloration of the nail plate and the pigment referred to is conventionally melanin. It may involve single or multiple nails, both in finger and toenails.

Epidemiology

Melanonychia is a common cause of nail discoloration accounting for nearly half of the cases of chromonychia.[1] Longitudinal melanonychia is the commonest morphological pattern.[1] The data on prevalence of melanonychia comes from the studies on melanonychia striata and varies with the region and population of study. In a recent study from China, the prevalence was found to be 0.8%, equal among male and female.[2] While in Poland, melanonychia was observed in 19.46% with the mean age being 49 years,[3] Kawamura et al.[4] reported melanonychia in 11.4% with highest prevalence in people aged 21–26 years and Tasaki et al.[5] found the prevalence to be 20% in males and 23% in females. The number of nails involved and the width of the pigmented lesions differ according to causative factors. While drug exposure, dermatological diseases, and racial pigmentation typically involve multiple nails, lentigines and nail matrix nevus are monodactylic (involving single nail/digit).

Morphological Classification

A simple morphological classification of melanonychia is given in [Table 1 and Figures 1-3].

Table 1.

Morphological classification of melanonychia

| Pattern of nail pigmentation | Clinical feature | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal melanonychia or melanonychia striata [Figure 1] | Longitudinal brown-black/grey band extending proximally from nail matrix or cuticle to distal free edge of the nail plate | Lentigine, nevus, melanoma |

| Diffuse or Total melanonychia [Figure 2] | Involvement of the entire nail plate by melanin | Constitutional/racial, drugs, infections |

| Transverse melanonychia [Figure 3] | Transverse band running across the width of nail plate | Drugs |

Figure 1.

Longitudinal pigmented band in an adult involving solitary digit

Figure 3.

Transverse band of melanonychia in a young patient receiving chemotherapy

Figure 2.

Diffuse nail plate pigmentation in an HIV-positive male patient

Pathogenesis

Though melanocytes are present in both nail matrix and bed, majority of them lie quiescent or dormant.[6] Melanocyte activation following trauma, infection, or inflammation initiates melanin synthesis and then the melanin-rich melanosomes are transferred to the differentiating matrix cells through dendrites. These matrix cells migrate distally and eventually become nail plate onychocytes, resulting in visible pigmentation in the nail plate.[6,7] Alternatively, melanonychia may also result from nail matrix melanocyte proliferation with (nevus) or without nest formation (lentigine).

Etiology

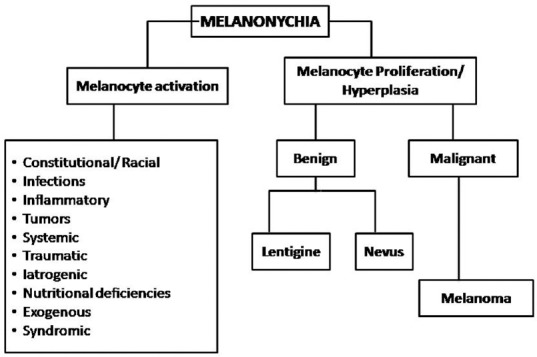

There are two main mechanisms of melanonychia [Figure 4]

Figure 4.

Etiology of melanonychia

1. Melanocytic activation—Refers to increased melanin production from normal number of activated melanocytes in the nail matrix.[8] It is also known as melanocyte stimulation and results from numerous causes listed in Figure 4

2. Melanocyte proliferation—Means increased melanin pigment secondary to increased number of melanocytes in the nail matrix.[8] The melanocytic hyperplasia or proliferation can be benign or malignant.

Nail matrix nevus and constitutional nail pigmentation are the most common causes.[1] The percentage distribution of the aforesaid causes varies in different population. The most common cause in a study evaluating melanonychia of all morphologies was found to be subungual hemorrhage (29.1%), followed by nail matrix nevus (21.8%), trauma (14.5%), lentigo (11.6%), and race (8.0%).[9] While in a study evaluating only longitudinal melanonychia, racial melanonychia was seen in 68.6%, trauma in 8.5%, fungal in 7.1%, and mixed etiology in 4.5% of cases.[10] Benign melanocytic hyperplasia and nail apparatus malignancy contributed to 5.7% cases each.

Clinical Features

Melanocytic activation

Constitutional

Racial melanonychia

It is commonly encountered in skin phototypes IV, V, and VI, that is, darkly pigmented races including Blacks, Asians, Middle-East, and Hispanics.[11] The incidence reportedly varies from 1% in whites, 10%–20% in Japanese and Asians, and 77–100% in African Americans.[7] Racial melanonychia is more common in fingers (thumb, index finger), generally involves multiple nails [Figure 5] and the band width increasing with age.

Figure 5.

Racial melanonychia in an adult male with type 5 skin type

Pregnancy

Skin hyperpigmentation is of common occurrence during pregnancy. Longitudinal melanonychia may also be associated with pregnancy and generally involves several finger and/or toe nails. It is thought to result from the activation of nail matrix melanocytes and may resolve or persist following delivery.[12,13]

Infections

Fungal melanonychia

Fungal melanonychia may be caused by both dematiaceous and nondematiaceous fungi; most common being Trichophyton rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum, followed by Alternaria and Exophiala.[14] It is commonly seen in males with frequent involvement of toenails. Fungi produce soluble, nongranular melanin which gets incorporated into the nail plate.[14] The involved nail typically has brown to black bands better seen with dermoscopy[15] and subungual hyperkeratosis with or without periungual inflammation. The pattern of nail involvement may indicate the causative agent. Longitudinal melanonychia is more common with dermatophytes like Trichophyton rubrum while diffuse pigmentation is seen with molds such as Scytalidium, Aspergillus niger [Figure 6], and Alternaria.[14]

Figure 6.

Fungal melanonychia caused by Aspergillus niger

Bacterial melanonychia

This is frequently caused by Gram negative pathogens; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella and Proteus.[16] The risk factors include wet work and an immunocompromised state. The pattern of nail involvement can be longitudinal streaks with wider proximal edge or diffuse which starts from the junction of proximal and lateral nail folds and spreads with irregular medial border.[16]

Viral

HIV patients may show diffuse melanonychia or multiple longitudinal or transverse bands in multiple fingers and toenails, often associated with hyperpigmentation of palms, soles and mucous membranes.[17] Longitudinal melanonychia can also be seen with ART drugs like zidovudine.[17]

Inflammatory disorders

Inflammatory skin conditions like psoriasis, lichen planus, amyloidosis, chronic radio dermatitis, and chronic paronychia in and around nail unit leads to melanocytic activation resulting in melanonychia.[7,18] Longitudinal melanonychia has also been seen in connective tissue diseases like systemic sclerosis and SLE.[19,20]

Tumors

Longitudinal melanonychia can also occur due to melanocytic activation by nonmelanocytic benign and malignant tumors such as onychomatricoma, Bowen's disease, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, subungual fibrous histiocytoma, verruca vulgaris and subungual keratosis.[11,21]

Systemic Diseases

Melanonychia in systemic diseases tends to involve multiple finger and toe nails, and generally presents as either diffuse melanonychia or multiple bands. It is uncommon and is seen in endocrine disorders (Addison's disease, Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism and acromegaly), alkaptonuria, hemosiderosis, hyperbilirubinemia, and porphyria. It can also be seen in Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD) and AIDS patients.[18,22]

Traumatic Melanonychia

Repeated trauma as seen in onychotillomania, onychophagia, or friction may lead to melanonychia.

Onychotillomania and onychophagia

Trauma to the nail matrix due to nail biting, picking, chewing or pulling leads to nail matrix melanocytes activation. This results in diffuse or regular longitudinal gray parallel bands of nail plate pigmentation, often accompanied by nail plate and periungual signs of trauma [Figure 7].[21]

Figure 7.

Longitudinal melanonychia in a male patient with onychophagia; note damaged cuticle and hang nails

Frictional

Chronic friction or pressure of ill fitted, tight, or pointed shoes leads to brown pigmentation of a part or whole of the great toe, fourth, and/or fifth toenails without any associated nail plate abnormalities.[21] This is also seen in athletes due to trauma to the proximal nail fold overlying the matrix.[21]

Iatrogenic Melanonychia

Melanonychia involving several finger and toe nails may be caused by phototherapy, electron beam therapy, X-ray exposure, radiodermatitis, and drugs. The pattern of nail involvement can be diffuse, transverse, or longitudinal.

Drug–induced melanonychia

Drug–induced melanonychia is often associated with other mucosal and cutaneous pigmentations. The type of melanonychia varies with the causative drug; nail bed pigmentation, transverse bands, and longitudinal melanonychia can be seen either alone or together.[7] Transverse melanonychia, although uncommon, is seen almost exclusively due to drugs.[11] The pigmentation involves several nails that fade either partially or completely following drug withdrawal[3] in 6–8 weeks but may take several months to years.[7] The list of common drugs causing melanonychia and their features are listed in Table 2.[7,11] Chemotherapeutic drugs are the most common agents.[7] Intermittent administration of chemotherapy can result in alternating bands of pigmentation.[23]

Table 2.

Drug-induced melanonychia

| Drugs | Features |

|---|---|

| Chemotherapeutic agents-Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, busulfan, taxanes, capecitabine, cisplatin, bleomycin, daunorubicin, dacarbazine, 5-FU, methotrexate | Seen 1-2 months after initiation |

| One or more transverse or longitudinal bands | |

| Cyclophosphamide-Diffuse black, longitudinal, or dark gray pigmentation of proximal nail plate[14] | |

| Doxorubicin: Alternating bands of dark brown and white lines, and transverse bands[14] Hydroxycarbamide: Distal or diffuse, dark brown[14] | |

| ART-Zidovudine, Lamivudine | Diffuse blue-brown, transverse or longitudinal bands |

| Fingernails > toenails. | |

| Appears after 3-8 weeks | |

| Reversible within 6-8 weeks, may persist for months | |

| Antimalarials-Amodiaquine, chloroquine, mepacrine, quinacrine | Melanonychia due to melanin and ferric dyschromia[3] |

| Others-Biologicals, clofazimine, infliximab, psoralens, phenytoin, fluconazole, cyclins, ketoconazole, phenothiazines, sulphonamides Metals-Arsenic, Thallium, Mercury |

Diffuse pigmentation, multiple nails |

Nutritional Deficiencies

Longitudinal melanonychia is seen in malnutrition especially protein energy malnutrition and vitamin D deficiency.[24] Vitamin B12 deficiency produces reversible nail pigmentation that can be longitudinal, diffuse bluish or reticulate probably due to reduced glutathione levels resulting in disinhibition of tyrosinase enzyme involved in melanogenesis.[25]

Exogenous Pigmentation

Brown to black pigmentation of nails can be seen due to exogenous agents like henna, dirt, tobacco, potassium permanganate, tar, and silver nitrate.[16] It presents as a horizontal band with the distal border parallel to the proximal nail fold and tends to move out with the nail plate [Figure 8].[16] Silver nitrate presents with a dark color band with irregular medial border and staining of adjacent skin of nail folds.[16]

Figure 8.

Exogenous melanonychia due to henna; note the advancing margin parallel to the PNF

Syndromes Associated with Melanonychia

Laugier–Hunziker syndrome, Peutz- Jegher and Touraine syndrome are characterized by LM along with pigmented macules in oral mucosa and lips.[7] LM involves several nails, generally finger nails with one or more bands. Laugier–Hunziker syndrome appears between 20 and 40 years of age and has no family history. On the contrary, Peutz–Jeghers and Touraine show autosomal dominant inheritance; the pigmented macules usually appear early during childhood and both are associated with intestinal polyposis and an increased risk for gastrointestinal and pancreatic malignancies.[7]

Sub-ungual Hematoma

Hematoma is the most common cause of nail brown-black pigmentation. It can be either acute (following single heavy trauma) or chronic (repeated, micro trauma). While acute subungual hematoma has a deep red/purple band and do not reach the free margin of the nail [Figure 9],[16] chronic subungual hematoma has a red brown, elliptical shape mimicking a longitudinal streak.[16] A true longitudinal band is seen very rarely. Small, round blood globules are seen at the periphery of hematoma on dermoscopy.

Figure 9.

Melanonychia due to subungual hematoma follwing acute blunt injury

Melanocytic Proliferation/hyperplasia

Benign Melanocytic Hyperplasia

It can be either due to nevus or lentigo. Lentigines are often seen more than nevi in adults while nevi are more common than lentigines in children.[11]

Nail matrix nevus

Nail matrix nevus may be congenital or acquired, majority being junctional. Nevus represents 12% of LM in adults and 48% of LM in children.[8,26] It generally presents as a light brown to black, 3–5 mm broad longitudinal band on fingernails especially thumb [Figure 10a].[21] The pigmentation is generally homogenous in intensity and color but dark bands may arise on light background, appreciated better on onychoscopy [Figure 10b]. Darker bands may be associated with periungual pigmentation (pseudo Hutchinson's sign) in one-third of the cases.[7,21] Histologically, nevus is characterized by the formation of nest of melanocytes.[7]

Figure 10.

Longitudinal melanonychia due to nail matrix nevus of the right thumb in 2.5 years-old boy. The band is 4 mm wide and brown in color (a). Dermoscopy shows regularly placed parallel lines of variable color. Note the pigment is visible on the PNF under the cuticle (b)

Lentigo

Lentigo is characterized by melanocytic hyperplasia with absence of melanocyte nests. Increased melanocytes (5–31 mm) are present within nail matrix epithelium. Lentigo in the nail matrix is more common in adults [Figure 11] and is observed in around 9% of all LM cases in adults.[8,26]

Figure 11.

Lentigo of nail matrix presenting as longitudinal melanonychia in a 55-years old man

Malignant Melanocytic Hyperplasia

Melanoma

Nail unit melanoma (NUM) is rare. It comprises about 0.7%–3.5% of all cases of cutaneous melanoma in the western world.[27] The incidence is variable in different races with a higher incidence (10%-25%) reported from Asian countries including Japan, China, and Korea.[27,28] The peak incidence is seen in 5th to 7th decades of life. Thumb, great toe, and middle finger are common sites.[7,28] LM is the first manifestation of NUM in 38%–76% of the cases.[27] Variegation in color, irregular/blurred borders of the band, crisscrossing, periungual pigmentation (Hutchinson sign), nail dystrophy, and ulceration or blood spots indicate malignant change [Figure 12] and a biopsy should be considered.[6,16] In rapidly growing melanomas, the proximal end of the band may be wider than the distal portion known as pyramidal sign [Figure 13]. NUM carries a poor prognosis as compared to cutaneous melanomas probably due to delay in diagnosis, the average delay being 2 years.[7,29] The five-year survival rate is 51%; 88% for a Breslow thickness of 2.5 mm or less and 44% for a thickness greater than 2.5 mm.[30]

Figure 12.

Subungual malignant melanoma with nail plate dystrophy, ulceration, and Hutchinson's sign

Figure 13.

Longitudinal pigmented band with broad proximal and narrow distal ends

Evaluation of Melanonychia

History

A detailed history including patient's age, history of trauma/any triggering factor, exogenous substance exposure, occupational history, hobbies, drug history, medical and family history is important. The onset (gradual/sudden), duration (short/long), rate of progression of melanonychia, and change in color or width of band must be enquired.

Clinical examination

Examination of all finger and toe nails and a complete muco-cutaneous examination is important for evaluation of melanonychia. One should note:

Number and location of involved nails—single/multiple

Morphology of LM—whether similar or different, if multiple nails involved

Site or location of melanonychia on the nail plate—above, within, or beneath. Examination of the distal free edge of the nail plate or hyponychium might indicate the origin of pigment. Ventral nail plate pigmentation originates from the distal matrix while the dorsal nail plate from proximal matrix.[21] The localization of pigment helps in selecting the anatomic site for exploration and biopsy, and can prevent a visible definitive nail dystrophy if the surgery is confined to the distal matrix[21]

-

Pattern of melanonychia—complete, longitudinal, or transverse.

Complete melanonychia—The extent and configuration (proximal and distal end including shape of proximal end of pigmentation with respect to proximal nail fold)

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM)—Color, homogeneity, regularity, width, whether wider proximally or distally, shape, margins and lateral borders of the band. Pyramid-shaped melanonychia with base toward proximal nail fold is suggestive of NUM

Other nail signs—Nail dystrophy, nail plate changes (abrasion, splitting or fissuring) and periungual pigmentation, bleeding are pointers to NUM. In addition, nail dystrophy and nail plate changes and pigmentation may be seen in fungal melanonychia

Other mucocutaneous sites for any inflammatory disorders, syndromic associations.

The ABCDEF rule helps to distinguish alarming LM from the nonalarming ones:[31] [Box 1]

Box 1.

The ABCDEF rule in LM

| The ABCDEF rule in LM |

|---|

| A (age, Afro-Americans, native Americans, and Asians): 5th and 7th decades |

| B (nail band): brown to black colour, ≥3 mm wide, irregular borders |

| C (change): rapid ↑ in size of band and/or change in morphology |

| D (digit involved): thumb > hallux > index finger, dominant hand, single digit |

| E (extension): Hutchinson’s sign |

| F (family): Personal or familial history of nevi dysplastic syndrome and melanoma. |

Laboratory evaluation

Nail plate sampling by nail clipping or punch biopsy can be done in doubtful cases about the nature of the pigment and in cases suspicious of fungal melanonychia.[18] The samples are sent for direct microscopy and culture (to exclude onychomycosis) and for histopathology (to confirm melanic pigmentation by Fontana stain).[18]

Dermoscopy of nail apparatus (Onychoscopy)

Onychoscopy has become an indispensable tool in the evaluation of pigmented nail lesions as it helps in validating the clinical findings. Onychoscopic examination of nail plate and distal edge is usually done with a magnification of 10 × with a handheld dermoscope or a digital videodermoscope.[32] Polarizing filters are less efficient in evaluation of nail plate due to their optical properties. Due to the convexity of nail plate, oil or gel immersion is required for visualization.[32] Distal edge onychoscopy generally requires more immersion gel or oil.[33] There are three basic steps:[34]

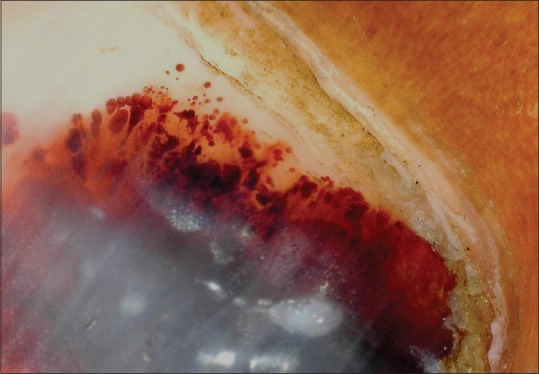

Differentiate the melanin and nonmelanin pigmentations.[35,36] [Table 3]. It is of utmost importance to identify subungual hematoma by the history of trauma and characteristic onychoscopic appearance. A subungual hematoma is identified by globules of various sizes and color—from bright red, brown to black depending upon the depth and duration of hemorrhage [Figure 14]. However, it should be remembered that subungual hemorrhage does not rule out melanoma

Determine the cause of pigmentation—melanocytic activation or proliferation.[24,25] [Table 4]

Distinguish benign and malignant proliferations.[35,36] [Table 4].

Table 3.

Onychoscopic features of pigmentation

| Type of pigmentation | Onychoscopic features |

|---|---|

| Melanin pigmentation | Brown-black, within nail plate, generally as a longitudinal band |

| Exogenous pigmentation (blood, henna, nail paint) | Substances adhering to or below nail plate, no longitudinal appearance, homogenous and located near nail folds with advancing margin running parallel to PNF |

Figure 14.

Onychoscopy of subungual hematoma; note globules of varying size and color at the margin (Dermlite, non-polarized, non-contact; x10x)

Table 4.

Onychoscopic features of cause of melanonychia

| Cause | Onychoscopic features |

|---|---|

| Melanocytic activation | Involvement of several nails, pale bands. Homogeneous grayish coloration of the background with regular gray lines is typical |

| Benign melanocytic proliferation | Brown back ground with brown-black parallel longitudinal lines of identical color, regular spacing and width |

| Malignant melanocytic proliferation | Variegate brown background with longitudinal brown to black lines that are irregular in width, spacing and demonstrate loss of parallelism. |

Limitations of Onychoscopy in melanonychia[21]

Overlap in various onychoscopic patterns exists. The brown background with lines irregular in color, width, and spacing are not indicative of melanoma in children. Benign lesions in adults can present with irregular lines and spacing

No established accurate onychoscopic patterns in the diagnosis of NUM

No criteria for frequency of onychoscopic follow-up in patients with LM

No precise onychoscopic criteria for deciding the precise time for biopsy.

Intraoperative onychoscopy (nail bed and matrix)— This is indicated in suspicious cases while performing nail matrix biopsy. It allows direct visualization of various dermoscopic patterns [Box 2] in nail bed and matrix.[37,38] It also helps in selecting the surgical margins for complete excision of the lesion.[37,38]

Box 2.

Features of intraoperative onychoscopy

| Pattern | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Regular gray | Melanocytic activation |

| Regular brown | Lentigo |

| Regular brown with globules (cell nests) or blotches (large pigment) | Melanocytic nevus |

| Irregular | Melanoma |

Biopsy

Whenever there is a doubt of NUM on clinical features and onychoscopy, histopathological diagnosis is the gold standard for confirmation of NUM. The preoperative diagnostic accuracy of melanoma ranges from 46% to 55%.[39]

There are no standard guidelines or algorithm for indications and time of biopsy in LM. It is suggested that any unexplained melanonychia of a single digit in white races should be biopsied to rule out NUM. On the contrary, LM of single digit in other races or LM in multiple nails may be followed up and biopsied whenever required.[6,39] In children, management is generally conservative as NUM is rare in this age group.

The type and site of biopsy depends upon the morphological characteristics of LM—its width and location of pigmentation in the matrix.[18] The sites and type of biopsies for melanonychia are listed in Table 5.[11,16,18,40] The biopsy sample should be of good quality, representative, adequate and from right location for proper diagnosis. An excisional biopsy whenever possible is recommended and matricial origin of pigmentation should be removed completely. Full-thickness matrix biopsy avoids any misdiagnosis and aids in prognosis by assessing Breslow depth. Nail matrix biopsy can cause nail scarring and deformity. To minimize these, distal nail matrix biopsy is preferred over proximal and the resultant defect of >3 mm should be sutured.[11]

Table 5.

Biopsy considerations in melanonychia

| Characteristics of LM | Type of biopsy | Site of biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| LM <2.5-3 mm, distal matrix origin | Punch biopsy | From the origin and deep until periosteum |

| LM <2 mm, proximal matrix origin | Punch biopsy/shave excision | At the origin, deep till periosteum |

| LM 3-6 mm wide, distal 2/3rd matrix origin | Transverse elliptical incision/shave excision | Proximal matrix remains intact, thin nail plate regenerates postoperatively |

| LM 3-6 mm, proximal 1/3rd matrix | Releasing flap method | Leaves post-surgical dystrophy (longitudinal nail splitting) |

| Bands >6 mm or | Tangential/shave excision | |

| Proximal matrix origin of any width or | ||

| Lesions less suspicious of melanoma | ||

| Pigmentation on lateral one-third of nail | Lateral longitudinal excision | Allows sampling of all components of the nail unit |

| High likelihood of invasive melanoma | Full thickness excision or biopsy | |

| Full thickness nail pigmentation | Excision biopsy or en bloc excision of nail apparatus |

The histopathological features in different causes of melanonychia are listed in Table 6.[41,42]

Table 6.

Histopathological features in melanonychia

| Cause of melanonychia | Histopathological features |

|---|---|

| Melanocytic activation | Epithelial hyperpigmentation, |

| Normal melanocytic number and structure (4-9 mm interval or 200 mm2), Dendritic melanocytes, | |

| Scattered melanophages, | |

| No mitosis | |

| Lentigo | Increased melanocytes (10-31 mm segment) with abnormal location, |

| Full-thickness pigmentation in matrix epithelium and nail plate, | |

| Dendritic melanocytes, | |

| Mild cytological atypia, | |

| Few melanophages, | |

| No cell nests and suprabasal melanocytes. | |

| No epithelial hyperplasia and pagetoid spread in matrix | |

| Melanocytic nevus | Junctional nevus with lentiginous pattern, |

| Melanocytic proliferation, | |

| Irregular or slightly confluent cell nests. | |

| Suprabasal pagetoid spread, | |

| Mild nuclear pleomorphism, | |

| Minimal cytological atypia, dermal inflammation, and nail plate involvement | |

| In-situ melanoma | Infiltrative edge, |

| Increased melanocyte proliferation and suprabasal melanocytes, | |

| Irregular distribution and asymmetry of melanocytes, | |

| Tendency of fusion in nests and epidermal consumption, | |

| Cytological atypia, | |

| Dermal lymphoid cell infiltration | |

| Invasive melanoma | Atypical melanocytic proliferation (39-136/mm), |

| Irregular distribution of melanocytes, | |

| Confluent and irregularly dispersed cell nests with suprabasal scatter, | |

| Cytological atypia, | |

| Increased mitosis, | |

| Lymphocytic infiltrate and anisodendrocytosis |

Imaging

Nail unit ultrasound and MRI can help in the diagnosis of melanonychia suspected due to nail tumors. They can also help in delineating the extent of lesion and involvement of adjacent structures.

Differential Diagnoses and Approach to Melanonychia

The following are the differential diagnoses of melanonychia according to the presentation-[34]

Nonmelanin pigmentation: The first and essential step is to establish the melanin or nonmelanin (e.g., exogenous, infections, hematoma) etiology

Multiple nail involvement—Racial, systemic causes, or frictional

Single nail explained by skin and nail diseases—Trauma, inflammatory disorders, or tumors

LM in children—Nail matrix nevus, Regular follow ups required

LM in adults—Histopathology may be needed if doubtful.

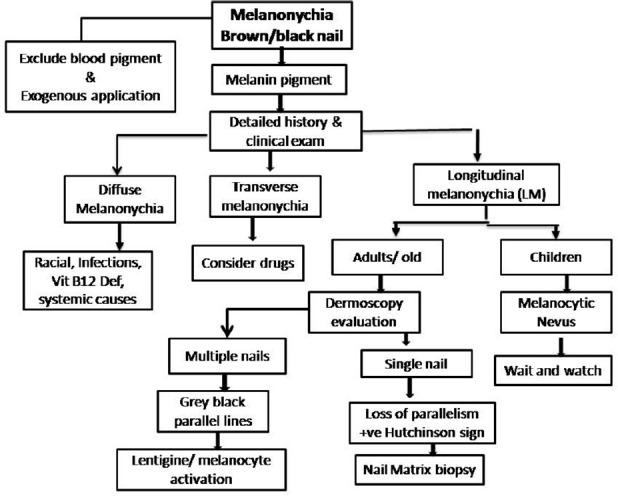

A comprehensive approach to melanonychia has been summarized in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

A comprehensive approach to evaluate melanonychia

Treatment

Treatment of melanonychia depends on the underlying cause. The treatment of associated systemic or locoregional disease, withdrawal of offending drug, avoidance of trauma, treatment of infections or correction of nutritional deficiencies may cause regression of pigmentation. Benign causes do not necessitate treatment and can be kept in follow up. Depending on thickness and histopathological characteristics, subungual melanoma may be managed by functional surgical treatment (wide local excision) or digit amputation with or without sentinel lymph node mapping/biopsy.[43]

Prognosis and Follow up

Prognosis of melanonychia depends on its etiology and its benign or malignant nature. Benign lesions can be followed up while NUM may carry a poor prognosis as discussed in the section. There is still no consensus for follow-up of melanonychia which requires periodic medical examinations and photographic and dermoscopic documentations. Onychoscopy can be used for follow ups but there are no precise criteria for its frequency in patients with LM. Good-quality clinical as well as onychoscopic photographs highlighting the involved nail and the pigment morphology, color, and extent is necessary for follow ups. Patients should be counselled for self-examination and to report whenever any morphological change in pigmentation is noticed.

Conclusions

Melanonychia is a challenging symptom for the clinician, irrespective of the patient's’ age. With careful history, clinical examination and investigations, it is possible to delineate an etiology; benign or malignant, in majority. Onychoscopy has become an indispensable tool in the evaluation of pigmentary nail disorders and should be performed in all cases. In suspected cases, one should have a low threshold for performing nail matrix biopsy as tissue diagnosis remains the gold standard.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bae SN, Young LM, Lee JB. Distinct patterns and aetiology of chromonychia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:108–13. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DLeung AK, Robson WL, Liu EK, Kao CP, Fong JH, Leong AG, et al. Melanonychia striata in Chinese children and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:920–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D Sobjanek M, Michajlowski I, Wlodarkiewicz A, Roszkiewicz J. Longitudinal melanonychia in a northern Polish population. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e41–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawamura T, Nishihara K, Kawasakiya S. Pigmentatiolongitudinalis striata unguium and the pigmentation of nail plate in Addison disease. Jpn J Dermatol. 1958;68:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasaki K. On band or linear pigmentation of the nail. Jpn J Dermatol. 1933;33:568. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrin C, Michiels JF, Pisani A, Ortonne JP. Anatomic distribution of melanocytes in normal nail unit: An immunohistochemical investigation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:462–7. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andre J, Lateur N. Pigmented nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:329–39. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tosti A, Baran R, Piraccini BM, Cameli N, Fanti PA. Nail matrix nevi: A clinical and histopathological study of twenty-two patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:765–71. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin H, Kim JM, Kim GW, Song M, Kim HS, Ko HC, et al. Diagnostic criteria for and clinical review of melanonychia in Korean patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez-Cherit J, Roldan-Marin R, Pichardo-Velazquez P, Valente C, Fonte-Avalos V, Vega-Memije ME, et al. Melanonychia, melanocytic hyperplasia, and nail melanoma in a Hispanic population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:785–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson J, Rich P. Melanonychia. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:952186. doi: 10.1155/2012/952186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monteagudo B, Suárez O, Rodriguez I, Ginarte M, Leon A, Pereiro M, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia in pregnancy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:550. doi: 10.1016/s0001-7310(05)73134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fryer JM, Werth VP. Pregnancy-associated hyperpigmentation: Longitudinal melanonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:493–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finch J, Arenas R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YJ, Sun PL. Fungal melanonychia caused by Trichophyton rubrum and the value of dermoscopy. Cutis. 2014;94:E5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haneke E, Baran R. Longitudinal melanonychia. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:580–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cribier B, Mena ML, Rey D, Partisani M, Fabien V, Lang JM, et al. Nail changes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1216–20. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.10.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lateur N, Andre J. Melanonychia: Diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2002;15:131–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skowron F, Combemale P, Faisant M, Baran R, Kanitakis J, Dupin M. Functional melanonychia due to involvement of the nail matrix in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(Suppl 2):187–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.108494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baran R. Longitudinal melanonychia in localized scleroderma: Report of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:e11–3. doi: 10.1016/S0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, de Farias DC. Dealing with melanonychia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baran R, Dawber RPR, Richert B. Physical signs. In: Baran R, Dawber RPR, deberker DAR, Haneke E, Tosti A, editors. Baran and Dawber's diseases of the nails and their management. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2001. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robert C, Sibaud V, Mateus C, Verschoore M, Charles C, Lanoy E, et al. Nail toxicities induced by systemic anticancer treatments. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e181–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seshadri D, De D. Nails in nutritional deficiencies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:237–41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.95437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niiyama S, Mukai H. Reversible cutaneous hyperpigmentation and nails with white hair due to vitamin B12 deficiency. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:551–2. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goettmann-Bonvallot S, Andre J, Belaich S. Longitudinal melanonychia in children: A clinical and histopathologic study of 40 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thai KE, Young R, Sinclair RD. Nail apparatusmelanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:71–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singal A, Pandhi D, Gogoi P, Grover C. Subungual melanoma is not so rare: Report of four cases from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:471–4. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_411_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klausner JM, Inbar M, Gutman M, Weiss G, Skornick Y, Chaichik S, et al. Nail-bed melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:803–10. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930340317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banfield CC, Redburn JC, Dawber RP. The incidence and prognosis of nailapparatus melanoma. A retrospective study of 105 patients in fourEnglish regions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:276–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levit EK, Kagen MH, Scher RK, Grossman M, Altman E. The ABC rule for clinical detection of subungual melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:269–74. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, Balme B, Viallard AM, Thomas L. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327–33. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun RP, Baran R, Saurat JH, Thomas L. Surgical pearl: Dermoscopy of the free edge of the nail to determine the level of nail plate pigmentation and the location of the probable origin in the proximal or distal nail matrix. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:512–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piraccini BM, Dika E, Fanti PA. Nail disorders: Practical tips for diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A, Starace M. Onychoscopy: Dermoscopy of the Nails. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lencastre A, Lamas A, Sa D, Tosti A. Onychoscopy. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:587–93. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirata SH, Yamada S, Almeida FA, Tomomori-Yamashita J, Enokihara MY, Paschoal FM, et al. Dermoscopy of the nail bed and matrix to assess melanonychia striata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:884–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirata SH, Yamada S, Almeida FA, Enokihara MY, Rosa IP, Enokihara MM, et al. Dermoscopic examination of the nail bed and matrix. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:28–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Chiacchio N, Hirata SH, Enokihara MY, Michalany NS, Fabbrocini G, Tosti A. Dermatologists’ accuracy in early diagnosis of melanoma of the nail matrix. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:382–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jellinek N. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia: Diagnostic algorithm including the matrix shave biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:803–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guneş P, Goktay F. Melanocytic Lesions of the Nail Unit. Dermatopathology. 2018;24:98–107. doi: 10.1159/000490557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruben BS. Pigmented lesions of the nail unit: Clinical and histopathologic features. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dika E, Patrizi A, Fanti PA, Chessa MA, Reggiani C, Barisani A, et al. The Prognosis of Nail Apparatus Melanoma: 20 Years of Experience from a Single Institute. Dermatology. 2016;232:177–84. doi: 10.1159/000441293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]