Abstract

Background

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a potentially blinding, secondary glaucoma. It is caused by the formation of abnormal new blood vessels, which prevent normal drainage of aqueous from the anterior segment of the eye. Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) medications are specific inhibitors of the primary mediators of neovascularization. Studies have reported the effectiveness of anti‐VEGF medications for the control of intraocular pressure (IOP) in NVG.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of intraocular anti‐VEGF medications, alone or with one or more type of conventional therapy, compared with no anti‐VEGF medications for the treatment of NVG.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register); MEDLINE; Embase; PubMed; and LILACS to 22 March 2019; metaRegister of Controlled Trials to 13 August 2013; and two additional trial registers to 22 March 2019. We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic search for trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of people treated with anti‐VEGF medications for NVG.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the search results for trials, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias, and the certainty of the evidence. We resolved discrepancies through discussion.

Main results

We included four RCTs (263 participants) and identified one ongoing RCT. Each trial was conducted in a different country: China, Brazil, Egypt, and Japan. We assessed the trials to have an unclear risk of bias for most domains due to insufficient information. Two trials compared intravitreal bevacizumab combined with Ahmed valve implantation and panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) with Ahmed valve implantation and PRP. We did not combine these two trials due to substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity. One trial randomised participants to receive an injection of either an intravitreal anti‐VEGF medication or placebo at the first visit, followed by non‐randomised treatment according to clinical findings after one week. The last trial randomised participants to PRP with and without ranibizumab, but details of the study were unavailable for further analysis.

Two trials that examined IOP showed inconsistent results. One found inconclusive results for mean IOP between participants who received anti‐VEGF medications and those who did not, at one month (mean difference [MD] ‐1.60 mmHg, 95% confidence interval [CI] ‐4.98 to 1.78; 40 participants), and at one year (MD 1.40 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.04 to 6.84; 30 participants). Sixty‐five percent of the participants with anti‐VEGF medications achieved IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, versus 60% without anti‐VEGF medications. In another trial, those who received anti‐VEGF medications were more likely to reduce their IOP than those who did not receive them, at one month (MD ‐6.50 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.93 to ‐5.07; 40 participants), and at one year (MD ‐12.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐16.79 to ‐7.21; 40 participants). Ninety‐five percent of the participants with anti‐VEGF medications achieved IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, versus 50% without anti‐VEGF medications. The certainty of a body of evidence was low for this outcome due to limitations in the design and inconsistency of results between studies.

Post‐operative complications included anterior chamber bleeding (3 eyes) and conjunctival hemorrhage (2 participants) in the anti‐VEGF medications group, and retinal detachment and phthisis bulbi (1 participant each) in the control group. The certainty of evidence is low due to imprecision of results and indirectness of evidence.

No trial reported the proportion of participants with improvement in visual acuity, proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels, or the proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness at four‐ to six‐week, or one‐year follow‐up.

Authors' conclusions

Currently available evidence is uncertain regarding the long‐term effectiveness of anti‐VEGF medications, such as intravitreal ranibizumab or bevacizumab or aflibercept, as an adjunct to conventional treatment in lowering IOP in NVG. More research is needed to investigate the long‐term effect of these medications compared with, or in addition to, conventional surgical or medical treatment in lowering IOP in NVG.

Plain language summary

Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular glaucoma

What was the aim of this review? To compare treatment with and without anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) medications for people with neovascular glaucoma (NVG).

Key message It is uncertain whether treatment with anti‐VEGF medications is more beneficial than treatment without anti‐VEGF medications for people with NVG. More research is needed to investigate the long‐term effect of anti‐VEGF medications compared with, or in addition to, conventional treatment.

What did we study in this review? VEGF is a protein produced by cells in your body, and produces new blood vessels when needed. When cells produce too much VEGF, abnormal blood vessels can grow in the eye. NVG is a type of glaucoma where the angle between the iris (coloured part of the eye) and the cornea (transparent front part of the eye) is closed by new blood vessels growing in the eye, hence, the name 'neovascular'. New blood vessels can cause scarring and narrowing, which can eventually lead to complete closure of the angle. This results in increased eye pressure since the fluid in the eye cannot drain properly. In NVG, the eye is often red and painful, and the vision is abnormal. High pressure in the eye can lead to blindness.

Anti‐VEGF medication is a type of medicine that blocks VEGF, therefore, slowing the growth of blood vessels. It is administered by injection into the eye. It can be used early stage, when conventional treatment may not be possible. Most studies report short‐term (generally four to six weeks) benefits of anti‐VEGF medication, but long‐term benefits are not clear.

What were the main results of this review? We included four studies enrolling a total of 263 participants with NVG. In one study, results beyond the treatment period of 1 week could not be evaluated. In another study, results were uncertain due to the limitation of study design.

The last two studies reported different results for lowering eye pressure; one study showed inconclusive results, and the other study showed that anti‐VEGF medications were more effective. The certainty of the evidence in these studies was low, due to limitations in the study designs and inconsistency of results. Therefore, available evidence is insufficient to recommend the routine use of anti‐VEGF medication in individuals with NVG.

How up to date is the review? We searched for studies that were published up to 22 March 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anti‐VEGF medications compared with no anti‐VEGF medications for neovascular glaucoma.

| Anti‐VEGF medication compared with no anti‐VEGF medication for neovascular glaucoma | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with neovascular glaucoma Setting: ophthalmology hospital or clinic Intervention: intravitreal anti‐VEGF medication injection Comparison: no anti‐VEGF medication | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no anti‐VEGF | Risk with anti‐VEGF | |||||

| Mean IOP 1 year follow‐up |

Arcieri 2015: MD 1.40 mmHg, 95% confidence interval ‐4.04 to 6.84 Mahdy 2013: IOP was lower in participants who received treatment with anti‐VEGF medications (MD ‐12.00 mmHg, 95% confidence interval ‐16.79 to ‐7.21) |

70 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Data were not pooled due to substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity (I² > 85%). | ||

| Proportion of participants with IOP≤ 21 mmHg, with or without ocular hypotensive medications 1 year follow‐up |

Arcieri 2015: 65% in the anti‐VEGF medication group and 60% in the no anti‐VEGF medications group achieved IOP ≤ 21 mmHg at the end of follow‐up (ranged from 1.5 to 3 years) Mahdy 2013: 95% in the anti‐VEGF medication group and 50% in the control group achieved IOP≤21 mmHg at 1 year |

80 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Data were not pooled due to substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity (I² > 85%). | ||

| Proportion of participants with improvement in visual acuity of 2 ETDRS lines or 0.2 logMAR units 1 year follow‐up |

Included studies did not report data for this outcome | |||||

| Proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels various follow‐up |

80% of participants in the anti‐VEGF medications arm and 25% of participants in the control arm had complete regression of iris new vessels at the end of follow‐up (ranged from 1.5 to 3 years)(P = 0.0015) | 40 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | |||

| Proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness 1 year follow‐up |

Included studies did not report data for this outcome | |||||

| Proportion of participants with adverse events various follow‐up |

|

263 (4) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | included studies did not report adverse events at 4 to 6 weeks or at 1 year | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Anti‐VEGF: anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor;IOP: intraocular pressure; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded (‐1) due to limitations in the design bDowngraded (‐1) due to inconsistency in treatment effects between studies cDowngraded (‐1) due to imprecision of results dDowngraded (‐1) due to indirectness of evidence

Background

Description of the condition

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a secondary glaucoma in which new vessels, and subsequently fibrous tissue, form in the anterior chamber angle of the eye. This leads to blockage of the angle, which inhibits aqueous drainage, causing elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). This condition was described as early as 1871 (Pagenstecher 1871; Tsai 2008). Historically, it has also been referred to as rubeotic glaucoma, hemorrhagic glaucoma, thrombotic glaucoma, congestive glaucoma, and diabetic hemorrhagic glaucoma.

Clinical conditions causing retinal ischemia, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), and ocular ischemic syndrome, are associated with NVG. The condition can be unilateral or bilateral, depending on the underlying cause for the NVG. Diabetic retinopathy is usually bilateral; CRVO is usually unilateral. Retinal ischemia results in the release of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The angiogenic factors diffuse into the aqueous and anterior segment, and trigger neovascularization of the iris and anterior chamber angle. This process leads to fibrous tissue proliferation, and subsequent synechial angle closure (closure of the angle because the iris is adhering to the cornea). Increased levels of VEGF have been measured in the aqueous of people with NVG (Aiello 1994; Sone 1996; Tripathi 1998). Elevated IOP is a direct result of secondary angle closure glaucoma.

NVG is a potentially devastating glaucoma. Delayed diagnosis or poor management can result in complete loss of vision, with intractable pain. It is imperative to diagnose it early, and treat it immediately and aggressively. In managing NVG, it is essential to treat both the elevated IOP and the underlying cause of the disease.

General principles for treating people with NVG include identifying the underlying etiology, reducing the symptoms, and controlling or eliminating retinal ischemia. Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) ablates the ischemic retina by shrinking and eliminating the abnormal blood vessels; however, when most of the angle is closed due to synechiae, consequent to the angle neovascularization, surgical treatment is necessary to control IOP. Surgical procedures for treating NVG are: trabeculectomy, implantation of aqueous drainage devices (Minckler 2006; Yalvac 2007), Nd‐Yag cyclophotocoagulation (Delgado 2003), vitrectomy with PRP and trabeculectomy (Kiuchi 2006), and cyclocryotherapy (Kovacic 2004). They may be done in conjunction with anti‐metabolites, such as 5‐Fluorouracil or mitomycin C, which modify wound healing and reduce scarring (Wilkins 2005; Wormald 2001).

Description of the intervention

Currently, anti‐VEGF medications are used for various conditions in which hypoxia‐induced VEGF release and subsequent neovascularization lead to ocular damage. Initially used in ophthalmology for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization in age‐related macular degeneration (Solomon 2019), the application of anti‐VEGF medications has expanded rapidly to include treatment for other conditions, such as NVG, diabetic macular edema, and retinopathy of prematurity (Andreoli 2007). Some of the anti‐VEGF medications most frequently used in the eye are bevacizumab, ranibizumab, pegaptanib sodium, and aflibercept (VEGF Trap‐eye).

How the intervention might work

In treating NVG, it is critical to address the underlying pathology – angiogenic factors released by the ischemic retina. The issue of retinal ischemia can be addressed by PRP, which ablates the ischemic retina and reduces further production of angiogenic medications. However, in many people, the view of the fundus is poor, due to corneal edema or vitreous hemorrhage, and therefore, precludes PRP. Hence, interventions aimed at directly blocking angiogenic factors could help reduce the formation of new vessels, and possibly reverse the neovascularization (Andreoli 2007; Arcieri 2015; Tripathi 1998). Intraocular injection of bevacizumab has been shown to reduce the levels of VEGF in the aqueous (Grover 2009).

In eyes in which PRP can be done, variable times for regression of new vessels have been reported, and the newly formed vessels may not regress until four to six weeks after treatment. In one study, Doft and Blankenship reported regression of new vessels in 20% of participants at three days, 50% at two weeks, 72% at three weeks, and 62% at six months (Doft 1984). In another study, Blankenship reported regression in 97% of participants at one month (Blankenship 1988). Comparision of studies is difficult, due to variation in the laser treatments, variation in the response to laser between type 1 and 2 diabetics, and the variation in the definition of substantial regression in different studies.

On the other hand, anti‐VEGF medications have been shown to cause regression of new vessels in the anterior chamber angle and a drop in IOP within a few days (Avery 2006; Iliev 2006). Intravitreal (Iliev 2006; Yazdani 2007), and less commonly, intracameral (Grover 2009) anti‐VEGF medications have been used in the management of NVG to control angiogenesis in the angle and iris. However, the effects of anti‐VEGF medications for treating NVG are temporary, generally lasting four to six weeks (Wakabayashi 2008). Thus, many studies have combined the use of anti‐VEGF medications with traditional treatments, such as PRP (Ehlers 2008; Ha 2017), with or without other surgery (Arcieri 2015; Gupta 2009; Kang 2014; Mahdy 2013; Noor 2017; Olmos 2016; Wakabayashi 2008; Wittstrom 2012; Yazdani 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

Various case reports, prospective and retrospective case series, and a few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown good short‐term benefit of anti‐VEGF use in NVG, when combined with conventional treatment that included PRP and IOP‐lowering procedures, such as trabeculectomy, insertion of aqueous drainage devices, cyclocryotherapy and Nd Yag cyclophotocoagulation. These studies reported better regression of iris new vessels and reduced postoperative incidence of hyphema. However, the sustained long‐term benefit of better IOP control and improved visual outcomes is not clear; while a few studies showed better outcomes, most studies showed no difference with the use of anti‐VEGF medications. Variation in participant allocation, number and doses of anti‐VEGF injections, and conventional treatment used in the studies makes comparison difficult.

On the basis of studies that showed that ischemic CRVO tends to eventually subside to a state of quiescence (Hayreh 2003), Gandhi 2008 suggested that anti‐VEGF medications alone can treat NVG secondary to CRVO effectively. In two participants with CRVO who had persisting neovascularization and high IOP in spite of PRP, Yazdani 2007 reported regression of new vessels and control of IOP following intravitreal bevacizumab. Maintenance of IOP control was reported for as long as six months following a second dose of intravitreal bevacizumab in both of these participants, one at eight weeks, and the other at six weeks. So the question arises: are intravitreal anti‐VEGF medications alone sufficient for the management of NVG due to CRVO?

The first published version of this review did not include any eligible trials (Simha 2013). An updated systematic review of the available literature is necessary to evaluate the effects of anti‐VEGF to inform evidence‐based practice.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of intraocular anti‐VEGF medications, alone or with one or more type of conventional therapy, compared with no anti‐VEGF medications for the treatment of NVG.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs only.

Types of participants

We included studies of people with NVG. We included all age groups and ocular comorbidities.

Types of interventions

Intervention group

People with NVG who received intraocular anti‐VEGF medications alone, or with one or more type of conventional therapy, which included laser PRP, trabeculectomy, insertion of aqueous drainage devices, cyclophotocoagulation, and cryotherapy.

In the subgroup of people with NVG due to CRVO, the intervention group could receive intraocular anti‐VEGF injection alone, without additional conventional therapy.

Control group

People who underwent the same conventional therapy as the intervention group, but without intraocular anti‐VEGF medications.

In the subgroup of people with NVG due to CRVO, the control group could receive placebo injections, or no treatment, including no conventional therapy.

We did not include dosing studies, in which one dose of anti‐VEGF medication was compared to another dose, unless the study also had a control arm.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome of this review was the proportion of participants who achieved control of IOP, measured at four to six weeks after treatment. Control of IOP was defined as IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, with or without ocular hypotensive medications.

Secondary outcomes

IOP

Proportion of participants with IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, with or without ocular hypotensive medications or other treatment, at one year

Mean IOP, with or without ocular hypotensive medications, at four to six weeks, and one year

Visual acuity

Proportion of participants with improvement in visual acuity of 2 ETDRS lines or 0.2 logMAR units at four to six weeks, and one year

Regression of new vessels

Proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels at four to six weeks, and one year

Relief of symptoms

Proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness at four to six weeks, and one year

Adverse events

Infection: proportion of participants with intraocular infection or inflammation (endophthalmitis) within six weeks of the intervention

Low IOP (hypotony): proportion of participants with IOP ≤ 6 mmHg at four to six weeks, and one year

Vitreous hemorrhage: proportion of participants with development of vitreous hemorrhage at four to six weeks, and one year

Tractional retinal detachment: proportion of participants who experienced tractional retinal detachment at four to six weeks, and one year

No light perception: proportion of participants with no light perception at four to six weeks, and one year

Other serious adverse events, including systemic thrombosis, stroke and coronary thrombosis, up to one‐year follow‐up

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the following electronic databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no restrictions on language or year of publication. The electronic databases were last searched on 22 March 2019. The last search of metaRegister of Controlled Trials was on 13 August 2013.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 3), which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register, in the Cochrane Library (searched 22 March 2019; Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 22 March 2019; Appendix 2);

Embase.com (1947 to 22 March 2019; Appendix 3);

PubMed (1948 to 22 March 2019; Appendix 4);

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS; 1982 to 22 March 2019; Appendix 5);

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT; www.controlled‐trials.com; searched 13 August 2013; Appendix 6).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 22 March 2019; Appendix 7);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp; searched 22 March 2019; Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of eligible studies to identify other potentially relevant trials. We did not contact investigators of ongoing studies for information about ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of all the reports of studies identified by the electronic searches, and handsearching, using Covidence (Covidence). Each review author classified the studies as: (1) definitely include (Yes), (2) possibly include (Maybe), and (3) definitely exclude (No). Each review author obtained and independently assessed the full text report(s) of each study classified by either review author as (1) or (2), and reclassified them as: (a) include, (b) awaiting classification, or (c) exclude. For reports from studies classified as (b), we attempted to contact study investigators for clarification. The two review authors compared their individual classifications and discussed discrepancies. When they could not reach consensus after discussion, a third review author reclassified the studies. We documented all studies classified as (c) exclude, and took note of any studies that are currently ongoing. We retrieved and reviewed all pertinent references from each potentially relevant study, in order to provide the most complete published information about study design, methods, and findings.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from included studies, using Covidence (Covidence). We resolved all discrepancies through discussion. One review author entered data into Review Manager 5, and a second review author verified the data entries (Review Manager 2014).

Categories of information extracted for each study included: methods (study design, number of participants, and setting), intervention details, outcomes (definitions and time points), and results for each outcome (sample size, missing data, summary data for each intervention).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias as recommended in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias. We provided judgement for each domain as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias, which indicated either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias. Specific criteria for assessing risk of bias focused on adequate sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking (blinding) of study participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; adequate handling of incomplete outcome data; absence of selective outcome reporting; and absence of other potential sources of bias. We attempted to contact the principal investigators if information was insufficient to judge risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Data analysis followed guidelines set forth in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

We had planned to present dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the following outcomes:

The proportion of participants with control of IOP (defined as IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, with or without ocular hypotensive medications);

The proportion of participants with improvement in visual acuity of 2 ETDRS lines or 0.2 logMAR units;

The proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels;

The proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness;

The proportion of participants with an adverse event.

In the absence of dichotomous data, we reported continuous IOP values as means with standard deviations, when data were available.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the affected eye of an individual participant. We documented studies that included participants with bilateral NVG, and used data based on the individual when possible (e.g. average of both eyes or one eye selected per participant). When data were not available based on the individual, or appropriate methods were not used to account for paired data due to the correlation between eyes, we extracted the data as reported, and performed a sensitivity analysis if we planned to include the data in a meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We consulted the guidelines in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to inform the analysis of studies with missing data (Higgins 2011b). Where data were missing due to loss of follow‐up, or there was a mismatch between reported time endpoints and our endpoints of interest, we conducted a primary analysis based on the data as reported. Where essential data needed for statistical analysis were incomplete or missing, we attempted to contact the principal investigators for details. Whenever possible, outcome data were derived from the study reports, and we described any assumptions made when extracting data. We did not impute data for the purposes of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by examining study characteristics, and forest plots of the results. We used the I² value to assess the impact of statistical heterogeneity, interpreting an I² value of 50% or more as substantial.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not examine small study effects using funnel plots, as we did not perform a meta‐analysis. We assessed incomplete outcome reporting at the trial level as part of the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

Data synthesis

Due to substantial heterogeneity among trials, we did not conduct a meta‐analysis, but reported results qualitatively and in tabular form only. For the future update, we will use a random‐effect model for meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As sufficient data were not available, we did not undertake subgroup analyses based on the etiology of NVG, including retinal vein occlusions, PDR, ocular ischemic syndrome, or other causes.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of studies with quasi‐random allocation methods, or those without masking of participants, providers, or outcome assessors, on the overall estimates of effect.

Summary of findings

We prepared a "Summary of findings" table with the following outcomes of interest at one‐year follow‐up: (1) the proportion of participants who achieved control of IOP defined as IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, with or without ocular hypotensive medications, (2) the proportion of participants with improvement in visual acuity of 2 ETDRS lines or 0.2 logMAR units, (3) the proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels, (4) the proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness, and (5) the proportion of participants with adverse events. As a post‐hoc decision, we also included mean IOP at one year (see Differences between protocol and review). We assessed the certainty of evidence for each quantitative outcome by using the GRADE classification system (GRADEpro GDT). We graded the certainty of evidence as very low, low, moderate, or high, based on these five criteria: risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

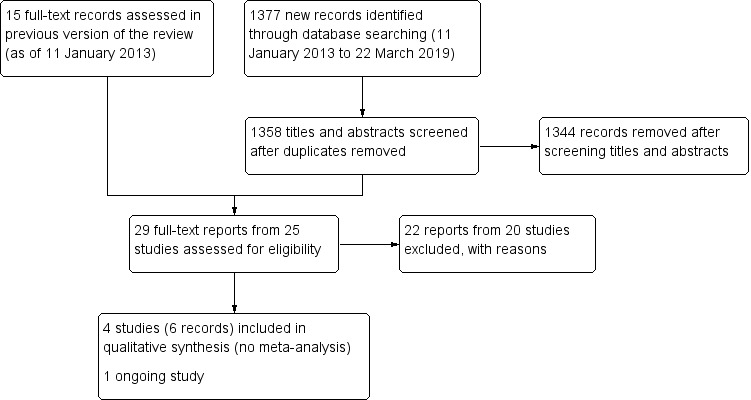

For this version of the review, we updated the electronic searches on 22 March 2019, and identified 1358 unique records (Figure 1). Of these, we excluded 1344 records after screening the titles and abstracts, and assessed 14 full‐text reports for eligibility, in addition to 15 records identified in the previous version of this review. Of 29 total records (25 unique studies), we excluded 22 records (20 studies); included six records for four unique RCTs (Arcieri 2015; Jiang 2015; Mahdy 2013; NCT02396316); and identified one ongoing RCT (NCT02914626).

1.

Flowchart showing results from literature search

Included studies

We included four RCTs that met the inclusion criteria, and summarized the details for each in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table (Arcieri 2015; Jiang 2015; Mahdy 2013; NCT02396316). The maximum planned or stated length of follow‐up varied from less than nine weeks (NCT02396316), to 18 months (Arcieri 2015), and 24 months (Mahdy 2013). Two RCTs, both multicentered studies, were registered in a clinical trials registry (Arcieri 2015; NCT02396316). Results for Arcieri 2015, Jiang 2015, and Mahdy 2013 come from journal publications; results for NCT02396316 come from a clinical trial registry. Mahdy 2013 declared no conflict of interest, and did not report information about a funding source; Jiang 2015 did not report the source of funding or conflict of interest; Arcieri 2015 was an unfunded study; and NCT02396316 was sponsored by Bayer and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Types of participants

All together, the four RCTs enrolled 263 adult participants with uncontrolled NVG from China (Jiang 2015), Brazil (Arcieri 2015), Egypt (Mahdy 2013), and Japan (NCT02396316). All four RCTs included both men and women; the mean age of participants was 55 years or older. In Mahdy 2013 and Arcieri 2015, numbers of participants who had CRVO or PDR as the underlying cause for NVG at baseline were comparable between the intervention and control groups. Data on the underlying cause for NVG were unavailable in the remaining two studies.

Arcieri 2015 required that all participants undergo PRP at least two weeks before enrollment; Mahdy 2013 also recruited participants undergoing PRP, but did not specify the exact timing. In Arcieri 2015, mean preoperative IOP was 40.10 mmHg (standard deviation [SD] 13.33) in the anti‐VEGF group, and 38.35 mmHg (SD 10.34) in the control group; in Mahdy 2013, it was 38.4 mmHg (SD 4.7) in the anti‐VEGF group, and 38.5 mmHg (SD 7.5) in the control group. Data on mean baseline IOP were unavailable in the remaining two studies.

Types of interventions

The anti‐VEGF medications the RCTs examined included intravitreal ranibizumab (Jiang 2015), bevacizumab (Arcieri 2015; Mahdy 2013), and aflibercept (NCT02396316). The adjunct treatments were PRP (Jiang 2015; NCT02396316); and PRP combined with an Ahmed glaucoma valve implant (Arcieri 2015; Mahdy 2013); NCT02396316 used sham injections in the control group. In all studies, participants were treated with anti‐glaucoma medications, as required, to improve control of their IOP.

Types of outcomes

Arcieri 2015 defined success as (1) achieving a postoperative IOP between 6 mmHg and 21 mmHg, with or without anti‐glaucoma medications, and (2) IOP reduction of at least 30% from baseline, at 1 day, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. This study also measured the presence of rubeosis iridis; neovascularization or the presence of goniosynechiae at the anterior chamber angle; gonioscopic and biomicroscopic findings; the number of anti‐glaucoma medications; and the presence of any postoperative complications.

Mahdy 2013 defined success as achieving an unmedicated IOP ≤ 21 mmHg, but ≥ 10 mmHg, without the need for additional glaucoma surgery or visually devastating complications at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 days, and at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months. This study also reported the best corrected visual acuity, iris neovascularization, anterior chamber depth, corneal and bleb appearance, and fundus examination.

Jiang 2015 evaluated mean IOP immediately following PRP. It is unclear whether investigators properly accounted for possible correlation, given the unit of analysis (eyes).

NCT02396316 examined the change in IOP from baseline to 1 week as the primary outcome, and the proportion of participants who had improved neovascularization of the iris grade from baseline to 1 week as the secondary outcome. This study also assessed safety by monitoring adverse events, vital signs, and clinical safety laboratory tests.

Excluded studies

We excluded 20 studies after full‐text review (see reasons in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table). We excluded eight studies from the updated searches (Bodla 2017; ChiCTR‐IPR‐15006695; EUCTR2007‐000585‐21‐IE; ; Kong 2017; Lin 2018; NCT03154892; Silva 2006; Wang 2016); 10 studies in the last version of this review (Caujolle 2012; Costagliola 2008; Eid 2009; Gupta 2009; Jonas 2010; Miki 2011; NCT01711879; Sedghipour 2011; Wittstrom 2012; Yazdani 2009); and two studies that were awaiting assessment in the previous version of this review (Chakrabarti 2008; NCT01128699).

In summary, we excluded 10 studies that were not RCTs, six studies that did not evaluate interventions eligible for this review, two studies that did not include participants with NVG, and two studies that were registered in a clinical trial register and listed as 'unknown/incomplete' for more than eight years. If these two incomplete studies are completed, or their status is updated, we will reassess them for eligibility in future versions of this review (EUCTR2007‐000585‐21‐IE; NCT01128699).

Risk of bias in included studies

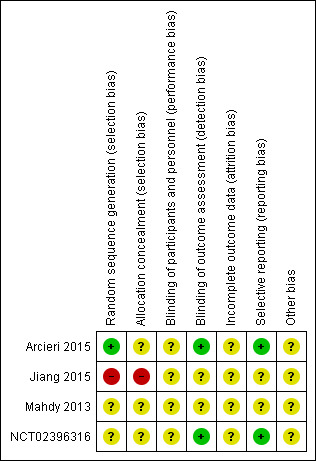

Figure 2 presents our assessment of the risk of bias in the included RCTs.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Arcieri 2015 described using a computer‐generated randomisation table to generate the randomization sequence but did not describe how this sequence was concealed. Mahdy 2013 and NCT02396316 provided no information about generating the random sequence or concealment of allocation. Jiang 2015 assigned participants to interventions based on a medical record number. Accordingly, we assessed Arcieri 2015 as low risk of bias for sequence generation and unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment; we assessed Mahdy 2013 and NCT02396316 as unclear risk of bias for both sequence generation and allocation concealment; we assessed Jiang 2015 as high risk of bias for both sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Blinding

We assessed all four studies as unclear risk of bias for masking of participants and personnel because they did not provide sufficient information; Arcieri 2015 and NCT02396316 did describe that the IOP assessor did not know which group participants were assigned to; thus, we assessed these two studies as low risk of bias for masking of outcome assessors for the primary outcome.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed all studies as unclear risk of bias for incomplete outcome data because we did not have sufficient information to permit judgement. In Arcieri 2015, the data for 5 participants (25%) in each arm were not included at the 1 year follow up, but the reasons for exclusion were not reported.

Selective reporting

We assessed Arcieri 2015 and NCT02396316 as low risk of bias for selective reporting of outcomebecause the full‐text reports included all outcomes specified on clinical trial registries . We judged as unclear risk of bias for this domain for the remaining two studies because the protocols or trial registrations were not available.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed all four studies as unclear risk of bias for other potential sources of bias: Arcieri 2015 did not report conflict of interest; sources of funding were unclear in Jiang 2015 and Mahdy 2013; NCT02396316 did not report role of the sponsors. Further for NCT02396316, participants who were randomised to sham injection could receive aflibercept injections after 1 week.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

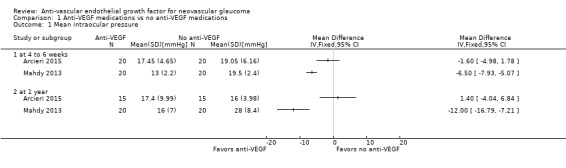

Intraocular pressure

Two RCTs reported mean IOP at one month or beyond (Arcieri 2015; Mahdy 2013) (Table 2; Table 3). We did not conduct a meta‐analysis, because of substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity (I² > 85%).

1. Arcieri 2015 – IOP at baseline and follow‐up.

| time point | IVB + PRP + AGV IOP (mean ± SD) | PRP + AGV (control) IOP (mean ± SD) | P value |

| Baseline | 40.10 ± 13.33 (N = 20) | 38.35 ± 10.34 (N = 20) | 0.6454 |

| 1 day | 10.68 ± 5.74 (N = 20) | 10.85 ± 6.74 (N = 20) | 0.9348 |

| 7 days | 10.35 ± 4.76 (N = 20) | 11.45 ± 5.77 (N = 20) | 0.5148 |

| 15 days | 14.00 ± 6.13 (N = 20) | 16.50 ± 7.34 (N = 20) | 0.2498 |

| 1 month | 17.45 ± 4.65 (N = 20 ) | 19.05 ± 6.16 (N = 20) | 0.3597 |

| 3 months | 18.30 ± 6.55 (N = 18 ) | 18.33 ± 5.44 (N = 17) | 0.9866 |

| 6 months | 16.78 ± 7.47 (N = 16) | 16.33 ± 4.35 (N = 17) | 0.3827 |

| 9 months | 18.31 ± 8.93 (N = 16) | 16.17 ± 4.60 (N = 16) | 0.8898 |

| 12 months | 17.40 ± 9.99 (N = 15) | 16.00 ± 3.98 (N = 15) | 0.4598 |

| 18 months | 14.57 ± 1.72 (N = 15) | 18.37 ± 1.06 (N = 14) | 0.0002 |

| 24 months | 14.43 ± 0.53 (N = 14) | 16.67 ± 4.40 (N = 12) | 0.0526 |

IOP: intraocular pressure (mmHg) SD: standard deviation IVB: intravitreal bevacizumab PRP: pan retinal photocoagulation AGV: Ahmed glaucoma valve N: number of eyes

2. Mahdy 2012 – IOP at baseline and follow‐up.

| time point | Avastin + PRP + AGV (N = 20 eyes) IOP (mean ± SD) | PRP + AGV (control) (N = 20 eyes) IOP (mean ± SD) |

| Preoperative | 38.4 ± 4.7 | 38.5 ± 7.5 |

| 1 week postoperative | 10.0 ± 3.1 | 13.5 ± 4.1 |

| 1 month postoperative | 13 ± 2.2 | 19.5 ± 2.4 |

| 3 months postoperative | 14 ± 1.9 | 22 ± 1.6 |

| 6 months postoperative | 16 ± 2.0 | 28 ± 3.1 |

| 12 months postoperative | 16 ± 7.0 | 28 ± 8.4 |

| 18 months postoperative | 16 ± 4.2 | 28 ± 6.5 |

SD: standard deviation IOP: intraocular pressure (mmHg) PRP: pan retinal photocoagulation AGV: Ahmed glaucoma valve

Arcieri 2015 found inconclusive results for a mean IOP difference between participants randomised to treatment with and without anti‐VEGF medications at one month (mean difference [MD] ‐1.60 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.98 to 1.78; 1 study, 40 participants), and at one year (MD 1.40 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.04 to 6.84; 1 study, 30 participants). Mahdy 2013 found that anti‐VEGF medications reduced IOP at both one month (MD ‐6.50 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.93 to ‐5.07; 1 study, 40 participants) and one year (MD ‐12.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐16.79 to ‐7.21; 1 study; 40 participants; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anti‐VEGF medications vs no anti‐VEGF medications, Outcome 1 Mean intraocular pressure.

The same two RCTs also reported the proportion of participants achieving IOP ≤ 21 mmHg with or without anti‐glaucoma medications (i.e. success): Arcieri 2015 observed 65% success in the anti‐VEGF medications arm, and 60% in the no anti‐VEGF medications arm at the end of follow‐up (mean ± SD: 2.25± 0.67 years, range 1.5 years to 3 years); Mahdy 2013 reported 95% success in the anti‐VEGF medications arm, and 50% in the no anti‐VEGF medications arm at one year.

Jiang 2015 reported that mean IOP immediately following treatment was lower for those who received anti‐VEGF medications; however, the interpretation of the results is uncertain, because it is unclear whether this analysis accounted for the potential unit of analysis issues in this study.

We graded certainty of the evidence as low due to limitations in the study design and inconsistency in treatment effects between studies.

Visual acuity

No trials reported on the proportion of participants who achieved an improvement in visual acuity of 2 ETDRS lines or 0.2 logMAR units at four to six weeks, or at one year.

Mahdy 2013 reported that 12 (60%) participants showed improvement in the best corrected visual acuity in the anti‐VEGF medications arm compared with 3 (15%) participants in the control arm, at 18 months. Improvement in visual acuity was attributed to clearing of the ocular media. Visual acuity worsened in 1 participant (5%) in the anti‐VEGF medications arm, and in 10 participants (50%) in the control arm. The report offered no reasons for the worsening of visual acuity. Arcieri 2015 reported no statistically significant difference in postoperative visual acuity (P > 0.1270), but did not specify the measurement time point. Jiang 2015 reported that visual acuity was higher in the experimental group compared to the control group, but the results were uncertain, due to the limitations of study design.

Regression of new vessels

Though all four RCTs noted that a larger proportion of participants had more regression of iris new vessels at various time points, only Arcieri 2015 and Mahdy 2013 reported on the proportion of participants with complete regression of new iris vessels, but the results were not reported at four to six weeks, or at one year. Mahdy 2013 (40 participants) reported complete regression of new vessels in 70% of the participants in the anti‐VEGF medications arm at one week, but did not provide results for the control group. Arcieri 2015 (40 participants) found that a 80% of the anti‐VEGF medications arm had complete regression of iris new vessels compared to 25% in the control group (P = 0.0015) at the end of follow‐up, which ranged 1.5 to three years.

We graded the certainty of the evidence as low due to imprecision of results and limitations in the design.

Relief of symptoms

No RCTs reported on the proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness at four to six weeks, or at one year.

Adverse events

All four studies (263 participants) reported adverse events. Arcieri 2015 reported that one participant (5%) in the control group experienced retinal detachment. In Mahdy 2013, phthisis bulbi occurred in one participant (5%) in the control group during the late postoperative period (> 3 months). Jiang 2015 noted that no participants experienced serious adverse events; however, anterior chamber bleeding was reported in three eyes (4.8%) in the intervention group and two eyes (3.0%) in the comparator group. NCT02396316 reported that two participants (7.4%) in the anti‐VEGF medications arm experienced conjunctival hemorrhage during the randomisation phase (first week). No serious adverse events were observed during this period. This study applied a non‐randomized design after the first week, in which participants could receive both sham injection and aflibercept injection if the re‐treatment criteria were met. Myocardial ischaemia, retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, and diabetic retinopathy were reported in one participant each during the non‐randomised period.

We graded the certainty evidence as low due to indirectiness and imprecision of results.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included four eligible RCTs (Arcieri 2015; Jiang 2015; Mahdy 2013; NCT02396316), and one ongoing study (NCT02914626) in this updated review. The four trials, taken together, randomised 263 adult participants to treatment with either anti‐VEGF medications or to treatment without anti‐VEGF medications. We were unable to synthesize the data quantitatively due to substantial clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity.

The studies arrived at different findings: Jiang 2015 and NCT02396316 did not report result for mean IOP for any time point we specified; Arcieri 2015 reported no difference in mean IOP at 1 month and at 1 year; Mahdy 2013 reported results favoring treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab at both time points. Improvement in visual acuity in greater proportion of participants in the anti‐VEGF arm were noted at 18 months by Mahdy 2013 whereas Arcieri 2015 reported no difference in visual acuity between the anti‐VEGF arm and control arm at the end of 24 months. Though all the four RCTs reported better regression of iris new vessels in the anti‐VEGFarm at various time points, mostly immediately after the anti‐VEGF injections, only Arcieri 2015 noted complete regression of new vessels in a greater proportion of participants in the ant‐VEGF arm as compared to the control arm over a longer follow up period of 2 years.

No RCTs reported the proportion of participants with relief of pain and resolution of redness. Two RCTs (Arcieri 2015; Mahdy 2013) reported the occurrence of one adverse event in one participant each in the control group. NCT02396316 though reported the occurrence of myocardial infarction in one participant, the event occurred during non‐randomisation phase. No serious adverse events were noted by Jiang 2015.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Of the four RCTs included, three were available through journal publications and one through trial registry. We assessed many of the risk of bias domains as unclear due to insufficient information to permit judgement. No relevant data were available for analysis for all but one outcome (IOP control) which we specified for this review. Four included RCTs were conducted in different geographic locations. The applicability to other populations including Caucasian is uncertain. Any conclusions must be read with caution due to the lack of completed data and the small numbers involved.

Quality of the evidence

We graded the certainty of the evidence as low for all outcomes reported by the included studies.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed standard Cochrane methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to minimize potential for introducing bias in the review process (Higgins 2011a). We worked with an information specialist to design a comprehensive search strategy and we searched multiple electronic databases, including clinical trial registries. We did not limit our search by date or by language. The review team was comprised of content experts and methodologists; two review authors completed tasks, such as screening references for inclusion and assessing studies, in duplicate, in order to minimize errors and bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review showed better regression of iris neovascularization in the short‐term with the use of anti‐VEGF medications in NVG, which was consistent with other non‐randomised studies (Grover 2009; Gupta 2009). Trials included in this review reported varying results in controlling IOP with the use of anti‐VEGF medications in the long‐term. Published meta‐analyses showed inconsistent findings, possibly due to methodological limitations of these reviews (Dong 2018; Hwang 2015; Zhou 2016).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We did not find any evidence from which to draw reliable conclusions regarding the long‐term benefits of the use of intraocular anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) medications alone, or as an adjunct to existing modalities for the treatment of neovascular glaucoma (NVG). Evidence is inadequate to assess the differences in adverse events with or without the use of anti‐VEGF medications.

The information available from two of the four included studies showed varying outcomes regarding the long‐term effectiveness of anti‐VEGF medications as adjuvants in the treatment of NVG; one reported better outcomes with the use of anti‐VEGF medications and the other found inconclusive results. Clinical practice decisions will need to based on the ophthalmologist's experience and judgment and the individual's preferences.

Implications for research.

Future trials could target a larger sample size and adopt a core outcome set, so that the data could be combined in a meta‐analysis. Randomization in future trials should be stratified by underlying aetiology for NVG or proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and the extent of peripheral anterior synechiae or angle closure, because both factors may modify the effectiveness of treatment, and imbalance in either could confound the results. We recognize that it will be difficult to recruit a sufficient number of participants to permit stratified randomisation and analysis of these factors, as NVG is not a common condition. In addition, angle assessment routinely done by gonioscopy is subjective, and its accuracy is affected by corneal edema, a condition present in many people with NVG. Nevertheless, it is important to provide more comprehensive evidence.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 January 2020 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Issue 2, 2020: 4 new studies added: Arcieri 2015; Jiang 2015; Mahdy 2013; NCT02396316 |

| 29 January 2020 | New search has been performed | Issue 2, 2020: Searches updated 22 March 2019 |

Acknowledgements

This review was produced with the assistance of protocol development and review completion workshops conducted by the South Asian Cochrane Network, based at the Professor B.V. Moses and ICMR Advanced Center for Research Training in Evidence Informed Healthcare, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Prathap Tharyan, the director of the Center for his never ending encouragement and help. The South Asian Cochrane Network is funded by the ICMR.

We thank Dr. Soumik Kalita for guidance through the process of training and working with Cochrane software. We thank Iris Gordon, Information Specialist for Cochrane Eyes and Vision (CEV), for designing and undertaking the electronic search strategies. We thank Dr. Barbara Hawkins and CEV methodologists for comments on the protocol and full review.

The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Amanda Bicket (Johns Hopkins Medicine), Bill Vaughan (National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare), and one peer reviewer who wished to remain anonymous.

The 2020 review update was managed by CEV@US and was signed off for publication by Tianjing Li and Richard Wormald.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Glaucoma, Neovascular] explode all trees #2 (glaucoma* or angle* or iris or anterior) near/4 (neovascular*) #3 (haemorrhagic or hemorrhagic or thrombotic or congestive or rubeotic or secondary) near/4 (glaucoma*) #4 NVG or NVI #5 {or #1‐#4} #6 MeSH descriptor: [Angiogenesis Inhibitors] explode all trees #7 (Angiogenesis or Neovascularization or Angiogenic or Angiogenetic) near/2 (Inhibitor* or Antagonist*) #8 (Angiostatic or "Anti Angiogenetic" or "Anti Angiogenic" or Antiangiogenic or "Anti Angiogenesis" or Antiangiogenesis) near/1 (Agent* or drug* or effect*) #9 MeSH descriptor: [Angiogenesis Inducing Agents] explode all trees #10 (Angiogenesis or Neovascularization or Angiogenic or Angiogenetic) near/2 (agent* or Stimulator* or Inducer* or factor* or effect*) #11 MeSH descriptor: [Endothelial Growth Factors] explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor: [Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors] explode all trees #13 VEGF or Vasculotropin or Vascular Permeability Factor* #14 macugen* or pegaptanib* or "eye 001" or eye001 or "NX 1838" or nx1838 or "222716‐86‐1" #15 MeSH descriptor: [Ranibizumab] explode all trees #16 lucentis* or lucentris or rhufab* or ranibizumab* or "347396‐82‐1" #17 MeSH descriptor: [Bevacizumab] explode all trees #18 bevacizumab* or avastin* or altuzan or "nsc 704865" or nsc704865 or "216974‐75‐3" #19 aflibercept* or Eylea or Zaltrap or "AVE 0005" or "AVE 005" or "845771‐78‐0" or "862111‐32‐8" #20 antiVEGF #21 (endothelial near/2 growth near/2 factor*) #22 {or #6‐#21} #23 #5 and #22

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. Glaucoma, Neovascular/ 2. ((glaucoma* or angle* or iris or anterior) adj4 neovascular*).tw. 3. ((haemorrhagic or hemorrhagic or thrombotic or congestive or rubeotic or secondary) adj4 glaucoma*).tw. 4. (NVG or NVI).tw. 5. or/1‐4 6. exp angiogenesis inhibitors/ 7. ((Angiogenesis or Neovascularization or Angiogenic or Angiogenetic) adj2 (Inhibitor* or Antagonist*)).tw. 8. ((Angiostatic or "Anti Angiogenetic" or "Anti Angiogenic" or Antiangiogenic or "Anti Angiogenesis" or Antiangiogenesis) adj1 (Agent* or drug* or effect*)).tw. 9. exp angiogenesis inducing agents/ 10. ((Angiogenesis or Neovascularization or Angiogenic or Angiogenetic) adj2 (agent* or Stimulator* or Inducer* or factor* or effect*)).tw. 11. exp endothelial growth factors/ 12. exp vascular endothelial growth factors/ 13. (VEGF or Vasculotropin or Vascular Permeability Factor*).tw. 14. (macugen* or pegaptanib* or "eye 001" or eye001 or "NX 1838" or nx1838 or "222716‐86‐1").tw. 15. exp Ranibizumab/ 16. (lucentis* or lucentris or rhufab* or ranibizumab* or "347396‐82‐1").tw. 17. exp Bevacizumab/ 18. (bevacizumab* or avastin* or altuzan or "nsc 704865" or nsc704865 or "216974‐75‐3").tw. 19. (aflibercept* or Eylea or Zaltrap or "AVE 0005" or "AVE 005" or "845771‐78‐0" or "862111‐32‐8").tw. 20. antiVEGF.tw. 21. (endothelial adj2 growth adj2 factor*).tw. 22. or/6‐21 23. 5 and 22

Appendix 3. Embase.com search strategy

1. 'neovascular glaucoma'/exp 2. ((glaucoma* OR angle* OR iris OR anterior) NEAR/4 neovascular*):ab,ti 3. ((haemorrhagic OR hemorrhagic OR thrombotic OR congestive OR rubeotic OR secondary) NEAR/4 glaucoma*):ab,ti 4. (NVG OR NVI):ab,ti 5. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 6. 'angiogenesis inhibitor'/exp 7. ((Angiogenesis OR Neovascularization OR Angiogenic OR Angiogenetic) near/2 (Inhibitor* OR Antagonist*)):ab,ti 8. ((Angiostatic OR "Anti Angiogenetic" OR "Anti Angiogenic" OR Antiangiogenic OR "Anti Angiogenesis" OR Antiangiogenesis) near/1 (Agent* OR drug* OR effect*)):ab,ti 9. 'angiogenesis'/exp 10. 'angiogenic factor'/exp 11. ((Angiogenesis OR Neovascularization OR Angiogenic OR Angiogenetic) near/2 (agent* OR Stimulator* OR Inducer* OR factor* OR effect*)):ab,ti 12. 'endothelial cell growth factor'/exp 13. 'vasculotropin'/exp 14. (VEGF OR Vasculotropin OR "Vascular Permeability Factor*"):ab,ti 15. (macugen* OR pegaptanib* OR "eye 001" OR eye001 OR "NX 1838" OR nx1838 OR "222716‐86‐1"):ab,ti,tn 16. (lucentis* OR lucentris OR rhufab* OR ranibizumab* OR "347396‐82‐1"):ab,ti,tn 17. (bevacizumab* OR avastin* OR altuzan OR "nsc 704865" OR nsc704865 OR "216974‐75‐3"):ab,ti,tn 18. (aflibercept* OR Eylea OR Zaltrap OR "AVE 0005" OR "AVE 005" OR "845771‐78‐0" OR "862111‐32‐8"):ab,ti,tn 19. antiVEGF:ab,ti 20. (endothelial near/2 growth near/2 factor*):ab,ti,tn 21. #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 22. #5 AND #21

Appendix 4. PubMed search strategy

1. ((glaucoma* [tw] OR angle* [tw] OR iris [tw] OR anterior [tw]) AND neovascular* [tw]) 2. ((haemorrhagic [tw] OR hemorrhagic [tw] OR thrombotic [tw] OR congestive [tw] OR rubeotic [tw] OR secondary [tw]) AND glaucoma* [tw]) 3. NVG [tw] OR NVI [tw] 4. #1 OR #2 OR #3 5. ((Angiostatic[tw] OR "Anti Angiogenetic"[tw] OR "Anti Angiogenic"[tw] OR Antiangiogenic[tw] OR "Anti Angiogenesis"[tw] OR Antiangiogenesis[tw]) AND (Agent*[tw] OR drug*[tw] OR effect*[tw])) 6. ((Angiogenesis[tw] OR Neovascularization[tw] OR Angiogenic[tw] OR Angiogenetic[tw]) AND (agent*[tw] OR Stimulator*[tw] OR Inducer*[tw] OR factor*[tw] OR effect*[tw])) 7. (VEGF[tw] OR Vasculotropin[tw] OR Vascular Permeability Factor*[tw]) 8. macugen*[tw] OR pegaptanib*[tw] OR "eye 001"[tw] OR eye001[tw] OR "NX 1838"[tw] OR nx1838[tw] OR "222716‐86‐1"[tw] 9. lucentis*[tw] OR lucentris[tw] OR rhufab*[tw] OR ranibizumab*[tw] OR "347396‐82‐1"[tw] 10. bevacizumab*[tw] OR avastin*[tw] OR altuzan[tw] OR "nsc 704865"[tw] OR nsc704865[tw] OR "216974‐75‐3"[tw] 11. aflibercept*[tw] OR Eylea[tw] OR Zaltrap[tw] OR "AVE 0005"[tw] OR "AVE 005"[tw] OR "845771‐78‐0"[tw] OR "862111‐32‐8"[tw] 12. antiVEGF[tw] 13. (endothelial[tw] AND growth[tw] AND factor*[tw]) 14. #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 15. #4 AND #14 16. Medline[sb] 17. #15 NOT #16

Appendix 5. LILACS search strategy

(MH:C11.525.381.348$ OR ((glaucoma* OR angle* OR iris OR anterior) AND neovascular*) OR ((haemorrhagic OR hemorrhagic OR thrombotic OR congestive OR rubeotic OR secondary) AND glaucoma*) OR NVG OR NVI) AND (MH:D27.505.696.377.077.099$ OR MH:D27.505.696.377.450.100$ OR MH:D27.505.954.248.025$ OR ((Angiogenesis OR Neovascularization OR Angiogenic OR Angiogenetic) AND (Inhibitor$ OR Antagonist$)) OR ((Angiostatic OR "Anti Angiogenetic" OR "Anti Angiogenic" OR Antiangiogenic OR "Anti Angiogenesis" OR Antiangiogenesis) AND (Agent$ OR drug$ OR effect$)) OR MH:D27.505.696.377.077.077$ OR ((Angiogenesis OR Neovascularization OR Angiogenic OR Angiogenetic) AND (agent$ OR Stimulator$ OR Inducer$ OR factor$ OR effect$)) OR MH:D12.644.276.390$ OR MH:D12.776.467.390$ OR MH:D23.529.390$ OR MH:D12.644.276.100.800$ OR MH:D12.776.467.100.800$ OR MH:D23.529.100.800$ OR VEGF OR Vasculotropin OR (Vascular Permeability Factor$) OR Macugen$ OR pegaptanib$ OR "eye 001" OR eye001 OR "NX 1838" OR nx1838 OR "222716‐86‐1" OR MH:D12.776.124.486.485.114.224.060.868$ OR MH:D12.776.124.790.651.114.224.060.868$ OR MH:D12.776.377.715.548.114.224.200.868$ OR lucentis$ OR lucentris OR rhufab$ OR ranibizumab$ OR "347396‐82‐1" OR MH:D12.776.124.486.485.114.224.060.375$ OR Bevacizumab$ OR avastin$ OR altuzan OR "nsc 704865" OR nsc704865 OR "216974‐75‐3" OR aflibercept$ OR Eylea OR Zaltrap OR "AVE 0005" OR "AVE 005" OR "845771‐78‐0" OR "862111‐32‐8" OR antiVEGF OR (endothelial AND growth AND factor$))

Appendix 6. metaRegister of Controlled Trials search strategy

neovascular glaucoma

Appendix 7. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

"secondary glaucoma" OR (neovascular AND (glaucoma OR angle OR iris OR anterior))

Appendix 8. ICTRP search strategy

glaucoma AND VEGF OR glaucoma AND Vasculotropin OR glaucoma AND Vascular Permeability Factor OR glaucoma AND macugen OR glaucoma AND pegaptanib OR glaucoma AND eye 001 OR glaucoma AND eye001 OR glaucoma AND NX 1838 OR glaucoma AND nx1838 OR glaucoma AND lucentis OR glaucoma AND lucentris OR glaucoma AND rhufab OR glaucoma AND ranibizumab OR glaucoma AND bevacizumab OR glaucoma AND avastin OR glaucoma AND altuzan OR glaucoma AND nsc704865 OR glaucoma AND aflibercept OR glaucoma AND Eylea OR glaucoma AND Zaltrap OR glaucoma AND antiVEGF OR glaucoma AND endothelial growth factor

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anti‐VEGF medications vs no anti‐VEGF medications.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean intraocular pressure | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 at 4 to 6 weeks | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 at 1 year | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arcieri 2015.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel‐group RCT Setting: multicenter trial in Brazil Number randomised: 40 participants Unit of analysis: participant (one study eye per individual) Maximum planned (or stated) length of follow‐up: 24 months Number not included in final analysis: 14 participants |

|

| Participants |

Number of men: 13 in the intervention group and 11 in the comparator group Number of women: 7 in the intervention group and 9 in the comparator group Mean age: 59 years in the intervention group and 62 years in the comparator group Mean IOP at baseline: 40 mmHg in the intervention group and 38 mmHg in the comparator group Inclusion criteria: older than 18 years with uncontrolled NVG, defined as an eye with IOP above 22 mm Hg using maximum tolerated glaucoma medication; PRP at least 2 weeks before enrollment Exclusion criteria: no light perception; NVG secondary to intraocular tumors or uveitis; unwilling or unable to return for follow‐up; pregnancy; learning difficulties, mental illness or dementia; previous cyclodestructive procedure, scleral buckle procedure, or silicone oil surgery |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention (N = 20): 0.05 mL intravitreal bevacizumab (concentration of 25 mg/mL) with Ahmed glaucoma valve implant Comparator (N = 20): 0.05 mL of sterile saline salt solution (placebo) with Ahmed glaucoma valve implant All participants underwent PRP at least 2 weeks prior to enrollment |

|

| Outcomes |

From prospective clinical trial registration Primary: IOP control, measured six months after randomization with Goldman applanation tonometer Secondary: safety of intravitreal bevacizumab up to six months after randomization |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: ACTRN12607000577415 Study dates: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Eligible patients with NVG were randomised to the following groups using a computer‐generated randomization table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information – method of sequence allocation not clearly mentioned to permit judgement of low risk or high risk |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias, insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Low risk of bias as outcome assessor did not know the group to which the participant was assigned: "Ophthalmologists responsible for the patients’ follow‐up were masked to the use of IVB" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias as data from 10 participants, 5 (25%) from each arm were unavailable at the 1 year follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No selective reporting identified; outcomes described in trial registration record were reported in full‐text publication. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias; this was an unfunded study |

Jiang 2015.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel‐group RCT Setting: single center trial in China Number randomised: 129 participants Unit of analysis: eyes (both eyes analyzed separately) Maximum planned (or stated) length of follow‐up: unclear Number not included in final analysis: unclear |

|

| Participants |

Number of men: 33 in the intervention group and 35 in the comparator group Number of women: 29 in the intervention group and 32 in the comparator group Mean age: 60.3 years in the intervention group and 60.24 years in the comparator group Mean IOP at baseline: not reported Inclusion criteria: not reported Exclusion criteria: not reported |

|

| Interventions | Intervention (N = 62): “retinal laser photocoagulation combined with ranibizumab treatment” Comparator (N = 67): “retinal laser photocoagulation” |

|

| Outcomes | From the abstract “After the treatment, the degeneration of iris neovascularization, visual acuity, intraocular pressure, ocular fundus, and the adverse reactions were evaluated.” | |

| Notes |

Trial registration: not reported Study dates: 2012 to 2014 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | The sequence generation was not truly random (investigators assigned participants to treatment based on medical record number or a similar identifier) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments, introducing bias |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias; study was not registered in a clinical trials registry and funding sources were not clearly reported |

Mahdy 2013.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel‐group RCT Setting: single center trial in Egypt Number randomised: 40 participants Unit of analysis: participant (one study eye per individual) Maximum planned (or stated) length of follow‐up: 18 months Number not included in final analysis: all participants included at 18 months |

|

| Participants |

Number of men: 12 in the intervention group and 11 in the comparator group Number of women: 8 in the intervention group and 9 in the comparator group Mean age: 55 years in the intervention group and 56 years in the comparator group Mean IOP at baseline: 38 mmHg in the intervention group and 39 mmHg in the comparator group Inclusion criteria: uncontrolled NVG using maximum tolerated glaucoma medication, with evident iris neovascularization and active retinal pathology; no previous PRP Exclusion criteria: no light perception; unwilling or unable to provide written informed consent; uncontrolled hypertension, renal disease, or a history of thromboembolic events, including myocardial infarction, cerebral insult |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention (N = 20): 0.05 mL intravitreal bevacizumab (1.25 mg) and PRP; Ahmed glaucoma valve implant two weeks after injection Comparator (N = 20): PRP with Ahmed glaucoma valve implant |

|

| Outcomes |

From study methods "At each visit, complete ophthalmic evaluation included best corrected visual acuity, corneal appearance, iris neovascularization, anterior chamber depth, IOP measurements, bleb appearance, and fundus examination" |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: not reported Study dates: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias ‐ insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias; study was not registered in a clinical trials registry; it declared "no conflict of interest"; there was no information about source of funding |

NCT02396316.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel‐group RCT Setting: multicenter trial in Japan Number randomised: 54 participants Unit of analysis: participant (one study eye per individual) Maximum planned (or stated) length of follow‐up: 1 week for randomised assessments; 9 weeks total Number not included in final analysis: all participants included at 1 week; 12 participants excluded at 9 weeks |

|

| Participants |

Number of men: 22 in the intervention group and 23 in the comparator group Number of women: 5 in the intervention group and 4 in the comparator group Mean age: 68 years in the intervention group and 66 years in the comparator group Mean IOP at baseline: not reported Inclusion criteria: 20 years or older with NVG with neovascularization in the anterior segment (both iris and anterior chamber angle) and IOP above 25 mmHg using maximum tolerated glaucoma medication Exclusion criteria: angle‐closure due to conditions other than NVG; known or suspected ocular or periocular infection; pregnancy or lactating; known allergy to aflibercept |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention (N = 27): intravitreal 2 mg aflibercept (Eylea, BAY 86‐5321) Comparator (N = 27): sham Injection |

|

| Outcomes |

From prospective clinical trial registration Primary: change in IOP from baseline to week 1 Secondary: percentage with improvement of neovascularization of the iris (NVI) grade from baseline to week 1, assessed using the NVI grading system (grade 0 to grade 4), where at least one grade reduction is considered to be improvement |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: NCT02396316 Study dates: April 2015 to September 2016 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The study design mentions triple blinding – of participant, investigator, and outcome assessor; however, it is not clear if the provider is also the investigator – it does not mention if the provider is blinded. Hence unclear risk of bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Low risk of bias as the outcome assessor did not know the group to which a participant was assigned |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias; all participants completed the 1 week follow‐up; however, after the 1st week, the conduct of the study was not a RCT |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Low risk of bias as the study reported all the outcomes specified at 1 week; outcomes specified on ClinicalTrials.gov were reported in the full‐text report |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear risk of bias – insufficient information to permit judgement of low risk or high risk of bias; after 1 week, participants may receive anti‐VEGF treatment; full‐text publication not yet available; this study was sponsored by Bayer and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals |

IOP: intraocular pressure mmHg: millimeters of mercury NVG: neovascular glaucoma PRP: panretinal photocoagulation RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bodla 2017 | Not RCT: comparative, interventional study comparing the short‐term efficacy of intracameral versus intravitreal bevacizumab 2.5 mg in 0.1 mL for the treatment of neovascular glaucoma in terms of iris neovessel regression and control of intraocular pressure |

| Caujolle 2012 | Not RCT: retrospective study of ranibizumab injections with or without cryotherapy; 14 participants (14 eyes) previously treated with proton therapy for uveal melanomas with minimum of 4 months follow‐up; no control group |

| Chakrabarti 2008 | Not RCT: allocation of participants to one of three treatment arms (PRP, IVB alone, IVB + PRP) was pragmatic, based on the clinical findings and severity of disease |

| ChiCTR‐IPR‐15006695 | Not comparison of interest: compared two different anti‐VEGF medications (bevacizumab and ranibizumab) with each other; no eligible control group |

| Costagliola 2008 | Not RCT: prospective pilot study of bevacizumab injections; 23 participants (26 eyes) received injections and were followed for 12 months; no control group |

| Eid 2009 | Not RCT: historical cohort study of bevacizumab injections and aqueous shunting surgery; 20 participants with NVG received injections, followed by surgery, and were compared to a historical group of 10 participants treated with PRP and surgery without bevacizumab |

| EUCTR2007‐000585‐21‐IE | Study not completed or confirmed: trial registered in 2007 with limited information and no contact information available; currently listed as ongoing, with no planned date of completion |

| Gupta 2009 | Not comparison of interest: RCT of intracameral bevacizumab prior to undergoing MMC trabeculectomy; participants received either 1.25 mg injections (N = 9) or 2.5 mg injections (N = 10), and were followed for six months; there was no control group in which no intracameral bevacizumab was given; participants may have been treated previously with some form of conventional treatment (PRP, anterior retinal cryopexy) or no conventional treatment Not RCT: historical cohort of non‐randomized participants who did not receive intracameral bevacizumab injections; outcomes from 16 participants (16 eyes) who had MMC trabeculectomy in years prior to the trial were compared with the outcomes from the trial participants |

| Jonas 2010 | Not RCT: retrospective chart review of IVB; 14 participants with iris neovascularization and secondary angle‐closure glaucoma treated with one to three intravitreal injections of bevacizumab and followed for at least 4 months; no control group |

| Kong 2017 | Not RCT: non‐randomized comparison of participants treated with 1) lucentis, 2) conbercept, 3) or no intravitreal injection, before AGV implantation |

| Lin 2018 | Not RCT: non‐randomized comparison of participants treated with ranibizumab combined with pars plana vitrectomy |

| Miki 2011 | Not RCT: prospective pilot study of bevacizumab injections as an adjunct to trabeculectomy; 15 participants (15 eyes) with previous vitrectomy were treated with trabeculectomy with MMC plus IVB, and were followed for 12 months; no control group |

| NCT01128699 | Study not completed or confirmed: trial registered in 2010 with limited information and invalid contact information; currently listed as recruiting, with unknown study status |

| NCT01711879 | Not comparison of interest: RCT of aflibercept in participants with NVG; both treatment groups received aflibercept, either one intravitreal injection of 2 mg (0.05 milliliter) aflibercept at baseline, followed by laser treatment with observation, or intravitreal injections of 2 mg (0.05 milliliter) aflibercept at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks, then every 8 weeks (all study participants received treatment with anti‐VEGF therapy). |

| NCT03154892 | Not comparison of interest: RCT compared intracameral versus intravitreal injection of conbercept for the treatment of NVG |

| Sedghipour 2011 | Ineligible population: RCT of IVB augmentation after trabeculectomy versus control group receiving a placebo injection after trabeculectomy; 37 participants with primary or secondary open angle glaucoma (excluded participants with neovascular glaucoma) |

| Silva 2006 | Not RCT: letter to the editor describing a case report |

| Wang 2016 | Not comparison of interest: one group was randomised to trabeculectomy and intravitreal bevacizumab and the other to cyclocryotherapy alone, making the two groups incomparable for the purposes of this review. Cyclocryotherapy usually is reserved only for people with very poor prognosis for vision. |