Summary

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has revolutionised biomedical research. The ease of design has allowed many groups to apply this technology for disease modelling in animals. While the mouse remains the most commonly used organism for embryonic editing, CRISPR is now increasingly performed with high efficiency in other species. The liver is also amenable to somatic genome editing, and some delivery methods already allow for efficient editing in the whole liver. In this review, we describe CRISPR-edited animals developed for modelling a broad range of human liver disorders, such as acquired and inherited hepatic metabolic diseases and liver cancers. CRISPR has greatly expanded the repertoire of animal models available for the study of human liver disease, advancing our understanding of their pathophysiology and providing new opportunities to develop novel therapeutic approaches.

Key Points

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing can be used to modify embryonic or somatic cells to create relevant disease models.

Somatic genome editing is a valuable tool in liver research, allowing for efficient and practical knockout of genes of interest in the entire liver.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been used to investigate a number of liver disorders including NAFLD, wherein a number of genes have been identified that increase an individual’s susceptibility to the condition

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing has been a valuable tool for the study of a number of inherited liver disorders.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been very useful in improving our understanding of the complex mutational profiles of liver cancers, with new models likely to lead to further advances.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

Introduction

Genetically engineered animals are powerful tools for the study of hepatic diseases. Previous approaches for creating disease models, such as recombinase-based genome engineering, were time-consuming and costly. CRISPR/Cas9, short for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9, has become a powerful tool for modeling liver diseases. CRISPR/Cas9 systems are bacterial defence mechanisms to combat bacteriophage infection; mediated by a host RNA sequence complementary to the viral DNA, the bacterial Cas9 introduces a double-strand break into the invading genome. These “molecular scissors” have been intensively studied[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6] and repurposed for applications in mammalian cells.[7], [8], [9], [10] Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 systems can introduce a double-strand break into virtually any DNA sequence. These double-strand breaks are most often repaired by the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which will introduce frameshift mutations or deletions that inactivate genes. Hence CRISPR is very efficient for destroying or inactivating genes (introducing mutations), with current efforts focused on increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair (template-mediated repair), which would allow for the precise insertion of new sequences and could be used to correct genes.11

These recent advances enable the rapid generation of embryonic and somatic modifications in animal models. Excellent reviews cover the development and application of CRISPR/Cas9,[11], [12], [13], [14], [15] therefore, we will focus specifically on disease modelling for the liver. We will first elaborate on some of the approaches used to generate CRISPR/Cas9-modified animals, before discussing recently published examples of human liver disease models.

CRISPR strategies to model liver disease

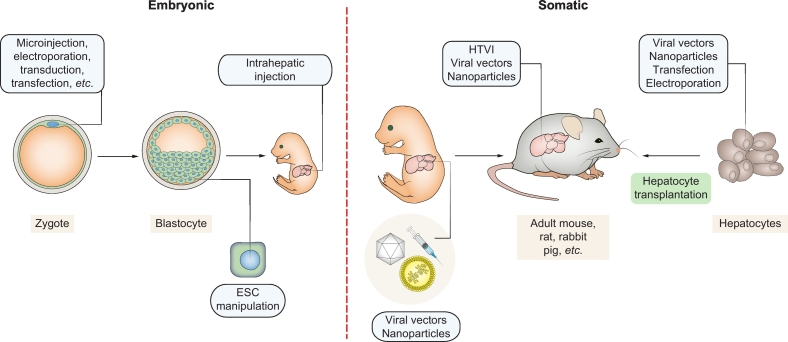

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has enabled the efficient modification of embryonic and somatic cells (Fig. 1). Liver disease models can be generated by manipulating either cell type, each having distinct advantages and drawbacks. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing can be used to modify embryonic or somatic cells to create relevant disease models.

Fig. 1.

Embryonic and somatic manipulations for generation of CRISPR disease models.

Microinjection of CRISPR/Cas9 is the state-of the art for zygote manipulations, but other deliver methods such as electroporation have been described.106,107 CRISPR can also be used for traditional embryonic stem cell targeting or direct embryonic editing by injection of the vitelline vein during pregnancy (E16).108 Nanoparticles, viral vectors and HTVI can be used for somatic gene editing. Hepatocytes can also be edited using the methods depicted, establishing new disease models upon transplantation and repopulation of the liver. ESC, embryonic stem cell; HTVI, hydrodynamic tail vein injection.

Embryonic genome engineering

Traditional strategies to genetically modify animals relied on the replacement or deletion of alleles via homologous recombination using embryonic stem cells (ESCs). The modified ESCs were injected into blastocytes to generate a chimera derived from modified and endogenous ESCs. In a subsequent step, the chimeric mice were bred, and if germline transmission was achieved, a genetically modified animal model was created. Due to its complexity and inefficiency, this process was arduous and expensive.16,17 Because the first ESCs were isolated from mouse blastocysts and mouse ESCs were readily available, this work was primarily confined to mice.

CRISPR provides a technically less challenging way to genetically modify animals. Microinjection of sgRNA (single guide RNA: the bioengineered targeting RNA) and Cas9 into zygotes leads to efficient gene editing in murine embryos,18,19 in many cases circumventing the need for prior ESC methods. Moreover, multiple alleles can be successfully targeted at the same time,18,20 significantly reducing time-consuming breeding procedures. Another advantage of CRISPR editing in zygotes is that there is usually no remaining transgene, especially if Cas9 is delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex. Traditional ESC targeting requires a selection step, commonly performed with a neomycin resistance cassette, which should be removed so that it does not interfere with hepatic gene expression21 and trigger silencing.22 CRISPR/Cas9 injection is now the preferred strategy for generating simple knockouts, introducing point mutations, and in some cases loxP sites for conditional models. It should be noted that insertion of larger sequences still requires targeting and selection in ESCs. Nonetheless, CRISPR has markedly accelerated the development of transgenic animal models and broadened the spectrum of species that can be targeted.23

These advances have greatly improved the modelling of human liver disorders and inborn errors of metabolism. Many different strains of mice, rats, rabbits and zebrafish have been generated using CRISPR technology. Moreover, additional animal models have been generated as research tools for hepatology, such as (drug) metabolism models20,[24], [25], [26] or potential transgenic sources of human albumin.27

Somatic genome engineering

The liver is unique compared to other organs in that it can be transfected in vivo via hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVI).28,29 Plasmids expressing Cas9 and sgRNA can be efficiently delivered to hepatocytes with a single injection using HTVI. The only drawback is that a maximum of 30% of the liver (centrilobular) can be transfected with this method. Hence, HTVI alone is insufficient to delete a gene of interest in the whole organ in order to create a liver-specific knockout model. Pankowicz et al. recently addressed this limitation by combining HTVI with a growth advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 edited hepatocytes,30 thus allowing edited hepatocytes to expand and repopulate the whole liver. This technique, called somatic liver knockout (SLiK), was used to create liver-specific knockout models of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis-2 (PFIC2) and argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) deficiency30(see below). A limitation of the SLiK technique is that it is performed in fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH)-deficient mice,20,30,31 which require special care due to the hepatotoxicity caused by FAH deficiency. Fah-/- mice are administered the small-molecule drug nitisinone,32 which inhibits the protein hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPD) to rescue the wild-type phenotype. The rational of SLiK-mediated gene editing is that the simultaneous targeting of Hpd and a separate gene of interest will confer a selection advantage to Hpd-deficient hepatocytes upon withdrawal of nitisinone. A major advantage of this approach is that hepatocytes will clonally expand, propagating cells with the same genetic modifications.

CRISPR can also be combined with other delivery systems (viral or non-viral)33 to generate organ-specific knockout models. For instance, an adenovirus vector was the first viral vector used for somatic genome editing in the liver, and succeeded in very efficient elimination of Pcsk934 and Pten.35 The development of smaller orthologues of Cas9,36,37 has made it possible to perform efficient liver-directed genome editing with adeno-associated viruses (AAV), which are currently the leading vector for liver gene therapy in humans. AAV vectors based on serotype 8 have now been used by many groups for somatic genome editing in mice.[37], [38], [39], [40], [41] Furthermore, lipid nanoparticles can be efficiently taken up by hepatocytes, because of their ability to interact with serum proteins,42 and have been successfully used in combination with CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing.43,44 A disadvantage of viral and nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 is the mosaicism of genetic modifications within the liver. The major advantage is the high efficiency, which allows for removal of a protein of interest across the entire liver within a week or two. Somatic genome editing is a valuable tool in liver research, allowing for efficient and practical knockout of genes of interest in the entire liver.

In summary, somatic genome editing in the liver is a valuable alternative to embryonic manipulations. Knocking out genes of interest in the liver is both efficient and practical. However, inserting precisely altering or correcting genes is very challenging, since homology-directed repair occurs only in dividing cells. Methods that promote homology-directed repair or selective expansion of gene-edited hepatocytes are in development, but much work remains. Given the multiple options for delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 to the liver, it is worth considering somatic genome editing as a faster and higher throughput alternative to embryonic manipulation.

CRISPR models of human liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been used to investigate disorders of liver metabolism, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is considered the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and represents the most common chronic liver disease.45 Currently, there are no effective therapies for NAFLD apart from lifestyle changes aimed at improving fitness and promoting weight loss.46 The first CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mouse model of NAFLD was generated by deleting the phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) gene, a negative regulator of PI3K/AKT activity.47 Xue et al. used HTVI to deliver CRISPR/Cas9-machinery (Cas9 and sgRNA targeting Pten) to mice. In a subsequent study by the same group, more efficient liver targeting was achieved using adenoviral vectors.48 Both delivery methods rapidly decreased PTEN expression in the liver in vivo: 4% and 29% of hepatocytes were Pten-negative following HTVI and adenoviral-mediated delivery, respectively. Whereas massive hepatic steatosis — a hallmark feature of NAFLD — was observed in both studies, steatohepatitis was only observed after adenoviral vector-delivery in a 4-month study timeframe.47,48 Importantly, adenoviral vector-delivery led to immune responses towards the viral DNA and the SpCas9 transgene.48

Another group delivered CRISPR/Cas9 via HTVI to knockdown Pten in the livers of adult rats.49 In this study, the authors reported that a high dosage of DNA coding for the CRISPR/Cas9 machinery was required for effective gene editing. Nonetheless, successful transfection led to a similar degree of weight gain and hepatic steatosis as observed in wild-type rats fed a high-fat diet.49

The transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2) variant Glu167Lys is associated with an increased incidence of NAFLD.50 Fan et al. used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to generate Tm6sf2 knockout mice in order to unravel the functional implications of this protein.51 While plasma total cholesterol levels were reduced and hepatic expression of lipid-related genes was altered in Tm6sf2 knockout mice, no significant changes were found in liver triglyceride accumulation either upon normal chow or high-fat diet feeding. The NAFLD phenotype of these mice turned out to be complex and more studies are needed to clarify the role of TM6SF2. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been used to investigate a number of liver disorders including NAFLD, wherein a number of genes have been identified that increase an individual’s susceptibility to the condition.

Hereditary tyrosinemia type I

Several groups have used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing to study inborn errors of hepatic metabolism (Table 1), which encompass heterogeneous and rare disorders that affect the activity of single or multiple hepatic metabolic pathways52 and constitute a significant cause of liver transplantation in paediatric patients.53 One example of such an inborn error is the hereditary tyrosinemia type I (HT-1). HT-1 is caused by a deficiency of FAH, the last enzyme in the catabolic pathway of tyrosine.[54], [55], [56] FAH deficiency results in the accumulation of hepatotoxic catabolites leading to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or metabolic decompensation in early childhood. The first Fah-deficient animal model, the albino lethal c14CoS mouse, was generated 40 years ago.31 Nevertheless, there is wide interest in generating new variants of this popular disease model. CRISPR/Cas9 and microinjection technology have been used to develop Fah-/- mice20,57 and rats.58 Rats have become an increasingly popular animal for CRISPR disease models. For one, zygote injection is very efficient in rats. Additionally, rats have some distinct biological advantages over mice; for example, the ease with which liver fibrosis forms in the Fah-/- animals.58 In contrast to Fah-deficient mouse models, Fah-/- rats and pigs develop hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis, more accurately mimicking the human pathophysiology.58,59

Table 1.

CRISPR-based animal models of liver disorders.

| Disease | Model | Target | Tissue-specificity | Approach | Phenotype | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency | Mouse | Asl, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | SLiK | Hyperammonemia and somnolence | Pankowicz et al. 201830 | |

| Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia | Rat | Apoe, loss-of-function | None | Zygote injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | High level of circulating LDL-cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, hepatosteatosis, atherosclerosis | Zhao et al., 201873 | |

| Familial hypercholesterolemia | Mouse, adult | Ldlr, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | Intraperitoneal injection; AAV-CRISPR | High level of circulating LDL, hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis |

AAV vector integration at CRISPR/Cas9 cut sites | Jarrett et al., 201740 and Jarrett et al. 201871 |

| Rat | Ldlr, loss-of-function | None | Zygote injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | High level of circulating LDL-cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, hepatosteatosis, atherosclerosis | Zhao et al., 201873 | ||

| Hereditary tyrosinemia type I | Rat | Fah, loss-of-function | None | Embryo injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Hypertyrosinemia, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis | Zhang et al., 201658 | |

| Hypermanganesemia with dystonia, polycythemia, and cirrhosis | Zebrafish | slc30a10, loss-of-function | None | Embryo injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | High level of circulating and hepatic Mn, hepatosteatosis, liver fibrosis | Xia et al., 201764 | |

| Niemann-Pick disease type C1 | Zebrafish | npc-1, loss-of-function | None | Embryo injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Hepatic accumulation of unesterified cholesterol | Tseng et al., 201865 Lin et al., 201866 |

|

| Wilson’s Disease | Rabbit | Atp7b, knock-in | None | Zygote injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Accumulation of copper in liver and kidney |

High frequency of off-target editing was reported | Jiang et al., 201860 |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Mouse, adult | Pten, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | Hydrodynamic injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis | Xue et al., 201447 | |

| Mouse, adult | Pten, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | Tail vein injection; Ad-CRISPR/Cas9 | Hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis, steatohepatitis (NASH-like) | Ad vector-associated immunotoxicity was observed in the liver | Wang et al., 201548 | |

| Rat, adult | Pten, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | Hydrodynamic injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Hepatosteatosis | High dosage of plasmid was required to induce NAFLD | Yu et al., 201749 | |

| Mouse | TM6SF2, loss-of function | None | Embryo injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Decreased plasma total cholesterol and LDL |

No NAFLD phenotype | Fan et al. 201651 | |

| Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 | Zebrafish | abcb11b, loss-of-function | None | Embryo injection; CRISPR/Cas9 | Impaired bile excretion, hepatocellular injury, induction of autophagy in hepatocytes | Ellis et al., 201876 | |

| Mouse | Abcb11, loss-of-function | Liver-targeted | SLiK | Impaired bile excretion with increase of bile acid in serum | Pankowicz et al. 201830 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

Mouse, adult | Ten tumour suppressors, loss-of-function | Liver | HTVI, CRISPR-Cas9 vector flanked by SB repeats | Tumour growth | No off-target effects found by amplicon-based NGS | Weber et al., 201584 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, adult | Nf1, Plxnb1, Flrt2, B9d1, loss-of-function | None | Subcutaneous transplantation of CRISPR/Cas9 edited p53-/-; Myc hepatoblasts (lentivirus) | Tumour growth | Song et al., 201787 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, adult | 56 known or putative tumour suppressors, loss-of-function | None | CRISPR AAV | Tumour growth | Wang et al., 201888 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, age uknown | Nras ,gain-of-function and Pten, loss-of-function | Liver | SB, CRISPR-Cas9, HTVI | Tumour growth, excessive lipid deposition in hepatocytes | Gao et al., 2017109 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, adult HBV transgenic mice | p53 and Pten, loss-of-function | Liver | CRISPR-Cas9, HTVI | Macroscopic tumour growth | Liu et al., 201793 | |

| Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, adult | Dnajb1-Prkaca gene fusion | Liver | CRISPR-Cas9, HTVI | Tumour growth | Engelholm et al., 201797 | |

| Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma | Mouse, adult | Dnajb1-Prkaca gene fusion | Liver | CRISPR-Cas9, HTVI | Tumour growth | Kastenhuber et al., 201796 | |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Mouse, adult | p53 and Pten, loss-of-function | Liver | CRISPR-Cas9, HTVI, carbon tetrachloride | Tumour growth | Xue et al., 201447 | |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Mouse, age unknown | HRASG12V gain-of-function, p53 loss-of-fucntion | Liver | HTVI; CRISPR homology-independent target integration | Tumour growth | Mou et al., 201991 |

AAV, adeno-associated viruses; HTVI, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NGS, next-generation sequencing; SLiK, somatic liver knockout.

Wilson disease

Jiang et al. created precision point mutations, using CRISPR technology in rabbits, to develop a model of Wilson disease (WD).60 WD is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by mutations in the membrane copper transporter gene, ATP7B.61,62 The authors targeted the Atp7b gene with sgRNAs and provided a single-stranded donor oligonucleotide template for homology-directed repair, to obtain the missense mutation Arg778Leu, a common disease mutation in Asian populations.60 When comparing zygotes obtained from donor rabbits 14 h or 19 h after human chorionic gonadotropin treatment, the authors found that injections performed in pronuclear embryos at earlier stages resulted in higher rates of point mutation (over 50%) and reduced gene knockout. Atp7b mutant rabbits exhibited copper accumulation in the liver and kidney, as observed in human WD, and died at an early age of 3 months. This study reported that off-target mutations were transmitted to offspring, emphasising the necessity of backcrossing mutant lines generated by zygote injection.

Hypermanganesemia with dystonia, polycythaemia, and cirrhosis

Due to their high degree of homology with humans and utility in high-throughput phenotypic screenings, zebrafish are a useful vertebrate model for human metabolic liver disorders. Autosomal recessive mutations in the human SLC30A10 gene, which encodes a manganese transporter, are associated with hypermanganesemia with dystonia, polycythaemia, and cirrhosis (or HMDPC). This disease is characterised by increased systemic levels of manganese, which accumulates in the liver and basal ganglia, causing a wide range of hepatic dysfunctions (e.g., steatosis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis) and parkinsonian-like syndrome.63 Zebrafish slc30A10 mutants were generated through the injection of a sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA into single-cell embryos, leading to the knockdown of this manganese transporter.64 Mutant animals exhibited increased systemic levels of manganese along with liver steatosis, fibrosis, and neurological defects. Like humans, slc30A10-mutant zebrafish were responsive to disodium calcium EDTA and ferrous fumarate therapies, which partially rescued the wild-type phenotypes.

Niemann-Pick disease type C1

Two groups independently reported zebrafish models for Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (NPC1).65,66 NPC is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by the accumulation of cholesterol in late endosomes/lysosomes.67 Currently, there are no effective therapies for NPC. Mutations in either NPC1 or NPC2 genes cause NPC, and both genes encode lysosomal proteins involved in the transport of cholesterol from the endolysosomal lumen to other intracellular organelles. Common manifestations of NPC1 include hepatomegaly and severe cirrhosis, along with progressive neurodegeneration.68 Tseng et al.65and Lin et al.66 utilised embryo injection with sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA to generate npc1 knockout zebrafish. Deficiency of npc1 recapitulated both the early-onset hepatic disease and the later neurological disease observed in patients with NPC1, namely, cholesterol accumulation in the liver and symptoms of ataxia. Of note, npc1 mutant larvae displayed a dark liver phenotype that facilitated the genotypic screening of live animals. In addition, a robust increase in in vivo LysoTracker Red staining was observed in npc1 mutants as early as 3 days post fertilisation.65 The ability to rapidly access pathophysiological readouts highlights the advantage of using CRISPR/Cas9-edited animals to accelerate large-scale phenotypic screening, which could be used to evaluate candidate drugs and compounds for new therapies.

Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency

Animal models of the urea cycle disorder ASL deficiency have also been generated using CRISPR/Cas9. The knockout mouse (Asl-/-) is neonatally lethal and is therefore of limited use.69 Using CRISPR and applying SLiK,30 edited Asl-/- hepatocytes gradually replace the murine liver, allowing animals to be used for metabolic studies. Once Asl-/- hepatocytes fully replace the murine liver, animals undergo metabolic crisis and have to be euthanised. The degree of replacement can be regulated and halted at any degree (30–100%) of chimerism of Asl-/- and Asl+/+ hepatocytes. Thus, SLiK allows for the study of milder phenotypes of ASL deficiency commonly observed in humans.

Familial hypercholesterolemia

Another metabolic disorder where CRISPR disease modelling has been applied is familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), an autosomal co-dominant disorder predominantly caused by mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene. Mutations in LDLR lead to impaired LDL uptake, hypercholesterolemia and, ultimately, severe atherosclerotic vascular disease.70 Jarrett et al. generated the first inducible model of FH using AAV-mediated delivery of sgRNA targeting Ldlr in adult Cas9 transgenic mice.40 Ldlr-edited mice exhibited increased plasma levels of LDL-cholesterol and developed atherosclerosis, thus recapitulating the human FH pathology. Follow-up work by the same group showed that delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 could be achieved with a single AAV vector,71 and that this approach is a viable alternative to the traditional germline model used to study atherosclerosis.72 These studies also identified integration of AAV vector sequences into CRISPR target sites, an important concern for therapeutic applications.

Fatty liver phenotypes similar to those observed in Ldlr-edited mice were also found in rats upon CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of apolipoprotein E (Apoe).73 ApoE is a component of lipoprotein remnants; its deficiency in humans leads to decreased clearance of remnants and an increased risk of atherosclerosis, a condition known as familial dysbetalipoproteinemia.74 CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of Ldlr and Apoe (either individually or in combination) was achieved by zygote microinjection of sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA, generating adult rats that exhibit hypercholesterolemia, hepatic steatosis, and atherosclerosis.73

Primary hyperoxaluria type I disease

Recently, Zheng et al. generated a rat model of primary hyperoxaluria type I disease.75 The authors deleted alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase in rat zygotes, resulting in severe nephrocalcinosis due to the formation of oxalate crystals, as seen in humans. Nevertheless, ethylene glycol in the drinking water was required to induce nephrocalcinosis in both rats and mice, which illustrates that animals often differ from humans when it comes to metabolism. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing has been a valuable tool for the study of a number of inherited liver disorders.

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing has also been used to investigate PFIC2,76 a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by defects in bile secretion.77 PFIC2 is caused by mutations in the ATP binding cassette family B, member 11 (ABCB11) gene, which encodes a bile salt export pump expressed in the apical membrane of hepatocytes involved in the transport of monovalent bile salts across the canalicular membrane.78 Patients with PFIC2 present with early-onset fibrosis and rapidly progress to end-stage liver disease during childhood, for which liver transplantation remains the only effective treatment.77

Traditional ESC targeting has been used to generate Abcb11 deficient mice (Abcb11-/-), however, offspring often die due to maternal cholestasis.79 Producing sufficient numbers of mice to study PFIC2 is therefore challenging. SLiK is a useful alternative method to generate liver-specific Abcb11 deletion.30 The Abcb11slik mice had bile acid levels comparable to the conventional Abcb11-/- mice and should be a useful new mouse model. Ellis et al. recently deleted abcb11b (the orthologue of Abcb11) in zebrafish using CRISPR.76 In this work, abcb11b was disrupted by embryo microinjection of sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA, leading to the near absence of Abcb11b protein in the liver.

Impaired bile salt excretion and increased hepatocyte autophagy occurred early in abcb11b mutants and rapidly progressed to hepatocellular injury, as in patients with PFIC2. Thus, these newly generated CRISPR/Cas9-edited zebrafish provide a useful in vivo tool to investigate the hepatocellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of PFIC2.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Liver cancer is the second most lethal cancer worldwide.80 The increasing mortality of both HCC81 and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)82 reflect the lack of therapeutic alternatives, as well as our inability to model liver cancer and thus understand its molecular basis. Manipulating mouse genetics through CRISPR is now widely adopted in cancer biology83 and has revolutionised the previously laborious undertaking of in vivo cancer modelling.

Using a sleeping beauty transposase vector system, another group generated a multiplex CRISPR knockout approach targeting 10 different tumour suppressor genes.84 Again, the CRISPR/Cas9 was introduced using HTVI, however the CRISPR/Cas9 machinery was randomly integrated into the host genome. Hence, it is unclear how often the CRISPR-deleted genes(s) or the integrating transposon vector account for tumorigenesis. Insertional mutagenesis is a major limitation of forward genetic CRISPR screenings when using transposons or lentiviral vectors.85,86 The latter was used recently in a CRISPR knockout screen targeting 20,611 genes in p53-/-, Myc overexpressing hepatoblasts.87 In this study, cells were transduced ex vivo with a lentiviral sgRNA library and then transplanted subcutaneously. After mice developed HCC, the authors sequenced tumours for sgRNA enrichment to identify cancer driver mutations and used HTVI to confirm identified genes and exclude integrational mutagenesis. Using a slightly different approach to identify cancer-driving mutations, another group designed an sgRNA library targeting 56 recurrently mutated genes but excluding known oncogenes.88 In contrast to previous work, the library used a non-integrating, episomal AAV vector. Tumours were analysed by a targeted capture sequencing approach of sgRNA target sites. Although more elegant, this targeted approach is somewhat limited by the number of genes analysed. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has been very useful in improving our understanding of the complex mutational profiles of liver cancers, with new models likely to lead to further advances.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

The first model of liver cancer that used CRISPR involved the deletion of the tumour suppressor genes p53 and Pten, in combination with exposure to the carcinogen carbon tetrachloride.47 Both tumour suppressors are frequently mutated in human ICC.89 Xue et al. targeted p53 and Pten, individually and in combination, by utilising HTVI of plasmids expressing Cas9 and sgRNAs. Consistent with previous studies, mice treated with either a p53 or Pten sgRNA did not exhibit liver tumours 3 months post-injection, whereas all mice that received a combination plasmid developed tumours with bile duct differentiation characteristics. The resulting murine tumours also had the histological appearance of ICC and stained for the cholangiocyte marker cytokeratin 19.

In contrast to loss-of-function, generating gain-of-function alleles by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing is more challenging, as it requires precise editing or genomic insertion of mutated oncogene cassettes. Generally, such accurate genomic alterations require homology-directed repair, which is inefficient and typically takes place during the G2/S phase of the cell cycle. Homology-independent target integration was recently developed to enable CRISPR-based targeting90 of quiescent organs such as the liver. A similar technique was used to generate a model of ICC through integration of the oncogene HRASG12V in combination with deletion of p53.91

The genetic alterations driving tumorigenesis are preceded by underlying environmental or inherited factors that damage the liver. For instance, HBV infection is endemic in some areas of the world, and since there remains no curative therapy for this major pathogen, HBV accounts for 33% of worldwide liver cancer.92 To better address its underlying aetiology, Liu et al. used HBV transgenic mice in combination with CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of p53 and Pten.93 Although the authors deleted the same 2 tumour suppressor genes as in a previous study,47 their tumours presented as HCC not ICC and were cytokeratin 19-negative. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear despite the distinct settings, namely carbon tetrachloride or transgenic HBV. Nevertheless, the results established in the HBV transgenic mice imply p53 and Pten deletion might act as oncogenic drivers in HBV-induced HCC, in agreement with clinical datasets.94

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

Finally, CRISPR-Cas gene editing has given rise to another model of liver cancer, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC). FL-HCC is a rare form of cancer that usually occurs in young adults and is caused by a 400 kb deletion on chromosome 19, leading to a fusion protein DNAJB1-PRKACA.95 Two groups used CRISPR to generate the Dnajb1–Prkaca fusion in mice.96,97 Both groups targeted Cas9 to the first introns of Dnajb1 and Prkaca to introduce double-stranded cuts in these regions, mimicking the chromosomal breaks occurring in human FL-HCC. When the genomic DNA fragment was excised in mice, the cell repair machinery utilised NHEJ to repair the DNA cuts, thereby creating the disease-associated Dnajb1-Prkaca gene fusion. The resulting tumours were consistent with the cytological and histological features (accumulation of mitochondria, prominent nucleoli, etc.) of FL-HCC.

CRISPR has facilitated the strenuous efforts of cancer gene discovery and the generation of knockout/knock-in models. For the first time, somatic gene editing in living animals is not only achievable but it is also efficient. The rapid development of liver cancer mouse models has created a new avenue to discern the mutational landscape of one of the world’s deadliest cancers. CRISPR has already contributed to the discovery of a vast number of hepatic tumour suppressors and oncogenes, and it will continue to redefine our understanding of the various alterations occurring in liver tumours.

Conclusions and outlook

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing is being rapidly integrated into biomedical research to generate new disease models for the liver. Although the mouse remains the most popular model organism, CRISPR/Cas9 editing is increasingly performed in other species such as rats, pigs and rabbits. Some experimental animals have metabolic features that closely resemble human metabolism. Hence it is worth considering studies in other species depending on the specific research question; for example, the CRISPR rat model for liver fibrosis or the rabbit model for lipoprotein metabolism. Human liver chimeric mice98,99 could be a good alternative for modelling many metabolic liver disorders, particularly if used for validation of macromolecular therapies. The therapeutic effect of macromolecular drugs varies significantly across species, in contrast to small molecules. We have recently described the first xenograft model for metabolic liver disease and used it to validate gene therapy for FH.100 Such xenograft models could also be generated using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and would have the advantage of being relevant in the human context.

The generation of CRISPR knockout animals by zygote injections is much less demanding than traditional techniques. However, it requires careful genotyping because the targeted alleles will harbour different mutations, significant deletions, and off-target editing. Backcrossing is required to eliminate mosaicism, to clearly identify the genetic alteration at the intended site, and to remove possible off-target edits elsewhere in the genome. Somatic genome editing is a very efficient approach for generating liver-specific knockouts with CRISPR/Cas9. Several gene therapy vectors efficiently transduce the liver and have been successfully used with CRISPR to edit liver genes. An alternative, particularly for multiplexing CRISPR or to investigate very severe disease phenotypes, is SliK.30 In only a few weeks, liver-specific knockout mice can be generated without the need to produce gene therapy vectors. However, somatic gene editing will introduce many different deletions, in contrast to embryonic editing, which results in a single well-defined deletion. In addition, the introduction of patient-specific mutations into murine disease genes is inefficient, as the most widely used CRISPR/Cas9 strategies require a homology-based repair mechanism which is limited by the quiescent nature of the liver. Engineered CRISPR/Cas-associated base editors have recently emerged as an alternative to improve precision genome editing independently of homology-directed repair and double-strand DNA break formation.[101], [102], [103] For example, it has been used for somatic gene editing in the liver of adult mice to drive Ctnnb1S45F mutations in a model of HCC104 and to correct phenylketonuria.105

In summary, many useful liver disease models have been and will be generated using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. The ease, accessibility, and efficiency of CRISPR have had a profound impact on animal modelling not only for the liver. In light of all the enthusiasm around CRISPR, the remaining challenges such as off-target editing are often neglected. It is conceivable that more accurate CRISPR/Cas systems will be found in bacteria or archaea, further facilitating the generation of disease models. In all, we must take advantage of this latest advance in genome engineering and build a bigger and better collection of models. This will help us to better understand liver disease and eventually develop effective therapies.

Abbreviations

AAV, adeno-associated viruses; ASL, argininosuccinate lyase; Cas9, CRISPR-associated protein 9; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; FL-HCC, fibrolamellar HCC; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HTVI, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NHEJ, non-homologous end joining; SLiK, somatic liver knockout; WD, Wilson disease

Financial support

K.D.B. is supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant HL134510 and HL132840 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) grant DK115461. K.D.B. is supported by the Texas Hepatocellular Carcinoma Consortium (THCCC) (CPRIT #RP150587) and Duke Cancer Institute (P30 CA014236). M.A-B. is supported by the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 18POST33990445.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgment

We thank William R. Lagor and Catherine Gillespie for critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.09.002.

Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology. 2005;151:653–663. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5429–5433. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jinek M, East A, Cheng A, Lin S, Ma E, Doudna J. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. Elife. 2013;2 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pankowicz FP, Jarrett KE, Lagor WR, Bissig KD. CRISPR/Cas9: at the cutting edge of hepatology. Gut. 2017;66:1329–1340. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lander ES. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 2016;164:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346 doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AV, Nunez JK, Doudna JA. Biology and Applications of CRISPR Systems: Harnessing Nature's Toolbox for Genome Engineering. Cell. 2016;164:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser S, Anastassiadis K, Stewart AF. Current issues in mouse genome engineering. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1187–1193. doi: 10.1038/ng1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson CM, Largaespada DA. Insertional mutagenesis in mice: new perspectives and tools. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:568–580. doi: 10.1038/nrg1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen B, Zhang J, Wu H, Wang J, Ma K, Li Z. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting. Cell Res. 2013;23:720–723. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barzi M, Pankowicz FP, Zorman B, Liu X, Legras X, Yang D. A novel humanized mouse lacking murine P450 oxidoreductase for studying human drug metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:39. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valera A, Perales JC, Hatzoglou M, Bosch F. Expression of the neomycin-resistance (neo) gene induces alterations in gene expression and metabolism. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:449–456. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.4-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham CT, MacIvor DM, Hug BA, Heusel JW, Ley TJ. Long-range disruption of gene expression by a selectable marker cassette. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13090–13095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X, Wong AS, Tam HY, Tsui SY, Chung DL, Feng B. In vivo genome editing thrives with diversified CRISPR technologies. Zool Res. 2018;39:58–71. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2017.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Tang Y, Lu J, Shao Y, Qin X, Li Y. Characterization of novel cytochrome P450 2E1 knockout rat model generated by CRISPR/Cas9. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;105:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu J, Shao Y, Qin X, Liu D, Chen A, Li D. CRISPR knockout rat cytochrome P450 3A1/2 model for advancing drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics research. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep42922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang F, Shi X, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Liang G. Growth hormone acts on liver to stimulate autophagy, support glucose production, and preserve blood glucose in chronically starved mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:7449–7454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901867116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng J, Wang Y, Jiang J, Zhou X, Song L, Wang L. Production of Human Albumin in Pigs Through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knockin of Human cDNA into Swine Albumin Locus in the Zygotes. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep16705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu F, Song Y, Liu D. Hydrodynamics-based transfection in animals by systemic administration of plasmid DNA. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang G, Budker V, Wolff JA. High levels of foreign gene expression in hepatocytes after tail vein injections of naked plasmid DNA. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1735–1737. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pankowicz FP, Barzi M, Kim KH, Legras X, Martins CS, Wooton-Kee CR. Rapid Disruption of Genes Specifically in Livers of Mice Using Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 Editing. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1967–1970.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gluecksohn-Waelsch S. Genetic control of morphogenetic and biochemical differentiation: lethal albino deletions in the mouse. Cell. 1979;16:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindstedt S, Holme E, Lock EA, Hjalmarson O, Strandvik B. Treatment of hereditary tyrosinaemia type I by inhibition of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Lancet. 1992;340:813–817. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92685-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin H, Kauffman KJ, Anderson DG. Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:387–399. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding Q, Strong A, Patel KM, Ng SL, Gosis BS, Regan SN. Permanent alteration of PCSK9 with in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Circ Res. 2014;115:488–492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng R, Peng J, Yan Y, Cao P, Wang J, Qiu C. Efficient gene editing in adult mouse livers via adenoviral delivery of CRISPR/Cas9. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3954–3958. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edraki A, Mir A, Ibraheim R, Gainetdinov I, Yoon Y, Song CQ. A Compact, High-Accuracy Cas9 with a Dinucleotide PAM for In Vivo Genome Editing. Mol Cell. 2019;73:714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.12.003. e714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Wang L, Bell P, McMenamin D, He Z, White J. A dual AAV system enables the Cas9-mediated correction of a metabolic liver disease in newborn mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin H, Song CQ, Dorkin JR, Zhu LJ, Li Y, Wu Q. Therapeutic genome editing by combined viral and non-viral delivery of CRISPR system components in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:328–333. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarrett KE, Lee CM, Yeh YH, Hsu RH, Gupta R, Zhang M. Somatic genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 generates and corrects a metabolic disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep44624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohmori T, Nagao Y, Mizukami H, Sakata A, Muramatsu SI, Ozawa K. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing via postnatal administration of AAV vector cures haemophilia B mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4159. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akinc A, Querbes W, De S, Qin J, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Jayaprakash KN. Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1357–1364. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang C, Mei M, Li B, Zhu X, Zu W, Tian Y. A non-viral CRISPR/Cas9 delivery system for therapeutically targeting HBV DNA and pcsk9 in vivo. Cell Res. 2017;27:440–443. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finn JD, Smith AR, Patel MC, Shaw L, Youniss MR, van Heteren J. A Single Administration of CRISPR/Cas9 Lipid Nanoparticles Achieves Robust and Persistent In Vivo Genome Editing. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2227–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xue W, Chen S, Yin H, Tammela T, Papagiannakopoulos T, Joshi NS. CRISPR-mediated direct mutation of cancer genes in the mouse liver. Nature. 2014;514:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang D, Mou H, Li S, Li Y, Hough S, Tran K. Adenovirus-Mediated Somatic Genome Editing of Pten by CRISPR/Cas9 in Mouse Liver in Spite of Cas9-Specific Immune Responses. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26:432–442. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Q, Tan RZ, Gan Q, Zhong X, Wang YQ, Zhou J. A Novel Rat Model of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Constructed Through CRISPR/Cas-Based Hydrodynamic Injection. Mol Biotechnol. 2017;59:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s12033-017-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozlitina J, Smagris E, Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Zhou HH, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:352–356. doi: 10.1038/ng.2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan Y, Lu H, Guo Y, Zhu T, Garcia-Barrio MT, Jiang Z. Hepatic Transmembrane 6 Superfamily Member 2 Regulates Cholesterol Metabolism in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1208–1218. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hansen K, Horslen S. Metabolic liver disease in children. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:391–411. doi: 10.1002/lt.21470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schilsky ML. Transplantation for inherited metabolic disorders of the liver. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanguay RM, Valet JP, Lescault A, Duband JL, Laberge C, Lettre F. Different molecular basis for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase deficiency in the two clinical forms of hereditary tyrosinemia (type I) Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47:308–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruppert S, Kelsey G, Schedl A, Schmid E, Thies E, Schutz G. Deficiency of an enzyme of tyrosine metabolism underlies altered gene expression in newborn liver of lethal albino mice. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1430–1443. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klebig ML, Russell LB, Rinchik EM. Murine fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah) gene is disrupted by a neonatally lethal albino deletion that defines the hepatocyte-specific developmental regulation 1 (hsdr-1) locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1363–1367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li F, Cowley DO, Banner D, Holle E, Zhang L, Su L. Efficient genetic manipulation of the NOD-Rag1-/-IL2RgammaC-null mouse by combining in vitro fertilization and CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5290. doi: 10.1038/srep05290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Shao Y, Li L, Tian F, Cen J, Chen X. Efficient liver repopulation of transplanted hepatocyte prevents cirrhosis in a rat model of hereditary tyrosinemia type I. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep31460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elgilani F, Mao SA, Glorioso JM, Yin M, Iankov ID, Singh A. Chronic Phenotype Characterization of a Large-Animal Model of Hereditary Tyrosinemia Type 1. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang W, Liu L, Chang Q, Xing F, Ma Z, Fang Z. Production of Wilson Disease Model Rabbits with Homology-Directed Precision Point Mutations in the ATP7B Gene Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1332. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19774-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanzi RE, Petrukhin K, Chernov I, Pellequer JL, Wasco W, Ross B. The Wilson disease gene is a copper transporting ATPase with homology to the Menkes disease gene. Nat Genet. 1993;5:344–350. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bull PC, Thomas GR, Rommens JM, Forbes JR, Cox DW. The Wilson disease gene is a putative copper transporting P-type ATPase similar to the Menkes gene. Nat Genet. 1993;5:327–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1293-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wahlberg K, Kippler M, Alhamdow A, Rahman SM, Smith DR, Vahter M. Common Polymorphisms in the Solute Carrier SLC30A10 are Associated With Blood Manganese and Neurological Function. Toxicol Sci. 2016;149:473–483. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xia Z, Wei J, Li Y, Wang J, Li W, Wang K. Zebrafish slc30a10 deficiency revealed a novel compensatory mechanism of Atp2c1 in maintaining manganese homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tseng WC, Loeb HE, Pei W, Tsai-Morris CH, Xu L, Cluzeau CV. Modeling Niemann-Pick disease type C1 in zebrafish: a robust platform for in vivo screening of candidate therapeutic compounds. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11 doi: 10.1242/dmm.034165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Y, Cai X, Wang G, Ouyang G, Cao H. Model construction of Niemann-Pick type C disease in zebrafish. Biol Chem. 2018;399:903–910. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vance JE, Karten B. Niemann-Pick C disease and mobilization of lysosomal cholesterol by cyclodextrin. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1609–1621. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R047837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vanier MT. Niemann-Pick disease type C. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reid Sutton V, Pan Y, Davis EC, Craigen WJ. A mouse model of argininosuccinic aciduria: biochemical characterization. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;78:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh S, Bittner V. Familial hypercholesterolemia--epidemiology, diagnosis, and screening. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2015;17:482. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jarrett KE, Lee C, De Giorgi M, Hurley A, Gillard BK, Doerfler AM. Somatic Editing of Ldlr With Adeno-Associated Viral-CRISPR Is an Efficient Tool for Atherosclerosis Research. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1997–2006. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI116663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao Y, Yang Y, Xing R, Cui X, Xiao Y, Xie L. Hyperlipidemia induces typical atherosclerosis development in Ldlr and Apoe deficient rats. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marais D. Dysbetalipoproteinemia: an extreme disorder of remnant metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015;26:292–297. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng R, Fang X, He L, Shao Y, Guo N, Wang L. Generation of a Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 Disease Model Via CRISPR/Cas9 System in Rats. Curr Mol Med. 2018;18:436–447. doi: 10.2174/1566524019666181212092440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellis JL, Bove KE, Schuetz EG, Leino D, Valencia CA, Schuetz JD. Zebrafish abcb11b mutant reveals strategies to restore bile excretion impaired by bile salt export pump deficiency. Hepatology. 2018;67:1531–1545. doi: 10.1002/hep.29632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jacquemin E. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:S26–S35. doi: 10.1016/S2210-7401(12)70018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gerloff T, Stieger B, Hagenbuch B, Madon J, Landmann L, Roth J. The sister of P-glycoprotein represents the canalicular bile salt export pump of mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10046–10050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Li F, Wang Y, Pitre A, Fang ZZ, Frank MW. Maternal bile acid transporter deficiency promotes neonatal demise. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8186. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol. 2004;40:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kieckhaefer JE, Maina F, Wells RG, Wangensteen KJ. Liver Cancer Gene Discovery Using Gene Targeting, Sleeping Beauty, and CRISPR/Cas9. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:261–274. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1678725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weber J, Ollinger R, Friedrich M, Ehmer U, Barenboim M, Steiger K. CRISPR/Cas9 somatic multiplex-mutagenesis for high-throughput functional cancer genomics in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:13982–13987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512392112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu M, Lu T, Jia Y, Luo X, Gopal P, Li L. Somatic Mutations Increase Hepatic Clonal Fitness and Regeneration in Chronic Liver Disease. Cell. 2019;177:608–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.026. e612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wangensteen KJ, Wang YJ, Dou Z, Wang AW, Mosleh-Shirazi E, Horlbeck MA. Combinatorial genetics in liver repopulation and carcinogenesis with a in vivo CRISPR activation platform. Hepatology. 2018;68:663–676. doi: 10.1002/hep.29626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Song CQ, Li Y, Mou H, Moore J, Park A, Pomyen Y. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Identifies Regulators of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase as Suppressors of Liver Tumors in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1161–1173. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.002. e1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang G, Chow RD, Ye L, Guzman CD, Dai X, Dong MB. Mapping a functional cancer genome atlas of tumor suppressors in mouse liver using AAV-CRISPR-mediated direct in vivo screening. Sci Adv. 2018;4 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ong CK, Subimerb C, Pairojkul C, Wongkham S, Cutcutache I, Yu W. Exome sequencing of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:690–693. doi: 10.1038/ng.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suzuki K, Tsunekawa Y, Hernandez-Benitez R, Wu J, Zhu J, Kim EJ. In vivo genome editing via CRISPR/Cas9 mediated homology-independent targeted integration. Nature. 2016;540:144–149. doi: 10.1038/nature20565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mou H, Ozata DM, Smith JL, Sheel A, Kwan SY, Hough S. CRISPR-SONIC: targeted somatic oncogene knock-in enables rapid in vivo cancer modeling. Genome Med. 2019;11:21. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer C, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683–1691. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu Y, Qi X, Zeng Z, Wang L, Wang J, Zhang T. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated p53 and Pten dual mutation accelerates hepatocarcinogenesis in adult hepatitis B virus transgenic mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2796. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03070-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, Sengupta S, Bertrand D, Weerasinghe A. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell. 2018;174:1034–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Honeyman JN, Simon EP, Robine N, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Darcy DG, Lim II. Detection of a recurrent DNAJB1-PRKACA chimeric transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2014;343:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1249484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kastenhuber ER, Lalazar G, Houlihan SL, Tschaharganeh DF, Baslan T, Chen CC. DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion kinase interacts with beta-catenin and the liver regenerative response to drive fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:13076–13084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716483114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Engelholm LH, Riaz A, Serra D, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Johansen JV, Santoni-Rugiu E. CRISPR/Cas9 Engineering of Adult Mouse Liver Demonstrates That the Dnajb1-Prkaca Gene Fusion Is Sufficient to Induce Tumors Resembling Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1662–1673. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.008. e1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bissig KD, Han W, Barzi M, Kovalchuk N, Ding L, Fan X. P450-Humanized and Human Liver Chimeric Mouse Models for Studying Xenobiotic Metabolism and Toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46:1734–1744. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.083303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bissig KD, Le TT, Woods NB, Verma IM. Repopulation of adult and neonatal mice with human hepatocytes: a chimeric animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20507–20511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710528105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bissig-Choisat B, Wang L, Legras X, Saha PK, Chen L, Bell P. Development and rescue of human familial hypercholesterolaemia in a xenograft mouse model. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7339. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551:464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim YB, Komor AC, Levy JM, Packer MS, Zhao KT, Liu DR. Increasing the genome-targeting scope and precision of base editing with engineered Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusions. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zafra MP, Schatoff EM, Katti A, Foronda M, Breinig M, Schweitzer AY. Optimized base editors enable efficient editing in cells, organoids and mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:888–893. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Villiger L, Grisch-Chan HM, Lindsay H, Ringnalda F, Pogliano CB, Allegri G. Treatment of a metabolic liver disease by in vivo genome base editing in adult mice. Nat Med. 2018;24:1519–1525. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen S, Lee B, Lee AY, Modzelewski AJ, He L. Highly Efficient Mouse Genome Editing by CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein Electroporation of Zygotes. J Biol Chem. 2016;29128:14457–14467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.733154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Modzelewski AJ, Chen S, Willis BJ, Lloyd KCK, Wood JA, He L. Efficient mouse genome engineering by CRISPR-EZ technology. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:1253–1274. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2018.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rossidis AC, Stratigis JD, Chadwick AC, Hartman HA, Ahn NJ, Li H. In utero CRISPR-mediated therapeutic editing of metabolic genes. Nat Med. 2018;24:1513–1518. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0184-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao M, Liu D. CRISPR/Cas9-based Pten knock-out and Sleeping Beauty Transposon-mediated Nras knock-in induces hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic lipid accumulation in mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2017;18:505–512. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1323597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material