This randomized trial studied the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for the treatment of subclinical anxiety and/or depression on disease course in young IBD patients. CBT did not influence time to relapse, clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein or calprotectin levels.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, IBD, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, disease course, children

Abstract

Background

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are prevalent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and may negatively influence disease course. Disease activity could be affected positively by treatment of psychological symptoms. We investigated the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) on clinical disease course in 10–25-year-old IBD patients experiencing subclinical anxiety and/or depression.

Methods

In this multicenter parallel group randomized controlled trial, IBD patients were randomized to disease-specific CBT in addition to standard medical care (CBT + care us usual [CAU]) or CAU only. The primary outcome was time to first relapse in the first 12 months. Secondary outcomes were clinical disease activity, fecal calprotectin, and C-reactive protein (CRP). Survival analyses and linear mixed models were performed to compare groups.

Results

Seventy patients were randomized (CBT+CAU = 37, CAU = 33), with a mean age of 18.3 years (±50% < 18 y, 31.4% male, 51.4% Crohn’s disease, 93% in remission). Time to first relapse did not differ between patients in the CBT+CAU group vs the CAU group (n = 65, P = 0.915). Furthermore, clinical disease activity, fecal calprotectin, and CRP did not significantly change over time between/within both groups. Exploratory analyses in 10–18-year-old patients showed a 9% increase per month of fecal calprotectin and a 7% increase per month of serum CRP in the CAU group, which was not seen in the CAU+CBT group.

Conclusions

CBT did not influence time to relapse in young IBD patients with subclinical anxiety and/or depression. However, exploratory analyses may suggest a beneficial effect of CBT on inflammatory markers in children.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC]) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the intestine and is often accompanied by embarrassing, invalidating, and unpredictable intestinal and systemic symptoms.1

Having IBD in adolescence impacts the lives of young IBD patients and is a threat to healthy psychosocial development. Patients may suffer from an altered self-image,2 the unpredictability of the disease, social isolation,3 family and school dysfunction, and school problems.4, 5 Consequently, having IBD challenges a smooth transition into adulthood.6 Studies show that adolescent and adult IBD patients are at risk for anxiety and depression7, 8 Recent meta-analyses in children and adults have shown pooled prevalence rates ranging from 16.4% to 35.1% for anxiety symptoms, and 15.0% to 21.6% for depressive symptoms.9, 10

The bidirectional relationship between IBD and psychological problems can be explained in terms of the “brain–gut” axis,11 meaning that the presence of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms or disorders can increase intestinal inflammation and may contribute to disease relapse, and, conversely, intestinal inflammation can negatively influence mood.11, 12 Several cross-sectional studies support this hypothesis by showing an association between clinical disease activity and symptoms of anxiety9, 12–14 or depression.9, 12, 13 In addition, this association has also been studied longitudinally. In a recent systematic review, 5 out of 11 studies reported an association between depressive symptoms and worsening of disease course.15 Similarly, for anxiety symptoms, some studies did report this association,12, 16 whereas others did not.17, 18 Besides the influence of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms on disease activity and disease course, IBD patients with psychological symptoms are at risk for school or work absenteeism,19, 20 lower therapy adherence,8 and higher health care utilization,8, 14 all leading to high societal costs.21 Therefore, studies on the effect of psychological treatment on disease course and these other aspects are warranted.

At present, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most effective evidence-based psychological treatment for anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders in patients of all ages22, 23 and has been found to be effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in both pediatric24, 25 and adult26 IBD patients.

Studies investigating the effect of CBT on disease activity or disease course in patients with anxiety and/or depressive symptoms or disorders are scarce. A randomized trial by Szigethy et al. studied 2 psychotherapies (CBT and supportive nondirective therapy) in adolescents with IBD with both minor and major depression. The authors report an improvement in clinical disease activity scores (raw increase of ±10 points on both the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index [PUCAI] and the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [PCDAI]) in the first 3 months in both groups, favoring CBT.25 In addition, a pilot study including 9 patients investigated the effect of CBT on clinical disease activity (PCDAI, PUCAI) in adolescent IBD patients suffering from an anxiety disorder, showing that clinical disease activity improved from mild to inactive in half of the patients after 3 months.24

Therefore, we performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in IBD patients aged between 10 and 25 years with subclinical anxiety and/or depression and evaluated the effect of CBT on the course of anxiety, depression, disease course, and inflammatory markers. The current study focused on the effect of 3 months of CBT on disease course in the following year. The primary outcome was time to first relapse; secondary outcome measures were clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein (CRP), and fecal calprotectin. We hypothesized that CBT would promote sustained remission, prolong the time until first relapse, and reduce clinical disease activity and inflammatory markers.

METHODS

Design

This multicenter parallel group RCT was designed according to the CONSORT guidelines for trials of nonpharmacologic treatments27 and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with study number NCT02265588. Participants were recruited from 2 university and 4 community hospitals in the Southwest of the Netherlands from September 2014 until October 2016. Initially, only adolescents aged 10–20 years were included in the study; a few months after start of recruitment, patients aged 21–25 years were also recruited. We chose to include adolescent and young adult patients because the impacts and challenges of a chronic disease in this unique life phase are different compared with what pediatric or adult patients are facing.

Eligible patients were screened for anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. Patients with symptoms of anxiety or depression or both were included, because anxiety and depressive symptoms often occur together and can both impact disease activity in IBD.16, 28 Patients with subclinical/elevated symptoms who did not meet the criteria of a psychiatric disorder were randomized to either a 3-month course of disease-specific CBT (CBT+CAU) in addition to care as usual or to the control condition, care as usual (CAU). After randomization, medical and psychological data were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months. Nine-month medical data were only collected if in routine medical care patients had scheduled appointments every 3 months. For more information regarding the study design, see van den Brink et al.29

Measurements

Demographic characteristics

Age and gender were collected at baseline. Socioeconomic status was classified using the occupational level of the parents or, if patients lived on their own, the occupational level of the patients.30 Ethnicity was derived from the Rotterdam Quality of Life Interview.31

Clinical characteristics

At baseline, disease type, age at diagnosis, disease duration, disease phenotype at diagnosis (Paris or Montreal classification),32 previous and current therapy, previous bowel surgery, and previous relapses were collected.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms

For anxiety, the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders33 (SCARED; 10–20 years; cutoff ≥26 for boys and ≥30 for girls) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety Scale34 (HADS-A; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥8) were used. For depression, the Child Depression Inventory35 (CDI; 10–17 years; cutoff ≥13) and the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition36 (BDI-II; 18–25 years; cutoff ≥14), were used.

Clinical disease activity

Clinical disease activity was assessed by 4 validated, physician-reported, age-appropriate instruments, with higher scores indicating more active disease.

In UC patients, the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index37 (10–20 years; score 0–85) and the partial Mayo38 (pMayo; 21–25 years; score 0–9) were used. In CD patients, the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index39 (10–20 years; total score 0–100) and the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index40 (CDAI; 21–25 years; score 0–600) were used.

Relapse

The presence of a relapse at any time point during follow-up was determined by the treating physician. For UC, relapse was defined as follows: (a) clinical disease activity score above cutoff (PUCAI >34 or an increase of ≥20 points or pMayo ≥341, 42) or (b) fecal calprotectin above 250 µg/g43or (c) inflammation at endoscopy and (d) intensification of treatment. For CD, relapse was defined as (a) clinical disease activity score above cutoff (PCDAI >30 or an increase of ≥15 points or CDAI score >15040, 44) or (b) fecal calprotectin above 250 µg/g43or (c) inflammation at endoscopy and (d) intensification of treatment. In addition, perianal disease requiring intervention in CD patients was also considered a relapse. If patients experienced a relapse at baseline, this relapse was not taken into account, and monitoring for relapse started after remission was achieved.

Inflammatory markers

C-reactive protein and fecal calprotectin were obtained during visits to the outpatient clinic as part of routine clinical care.

Recruitment and Procedure

Step 1: Screening

Eligible patients (and parents, for patients aged 10–20 years) were informed about the study by their treating (pediatric) gastroenterologist. Preferably, patients were recruited when they were in clinical remission, considering the impact of the intervention. The following in- and exclusion criteria were used: (1) a diagnosis of IBD conforming with current diagnostic criteria,45–47 (2) age 10–25 years, and (3) informed consent provided by patients and (if necessary) parents. Exclusion criteria were (1) parental report of intellectual disability, (2) current treatment for mental health problems (pharmacological and/or psychological), (3) insufficient mastery of the Dutch language, (4) CBT in the past year (for at least 8 sessions), (5) a diagnosis of selective mutism, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or post-traumatic or acute stress disorder, (6) participation in another interventional study, and (7) anxiety/depressive disorder. After written informed consent, an email with a link to the online questionnaires was sent to the patients (and parents). Anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed using age-appropriate self-report instruments (see “Measurements”). For more information regarding step 1, see van den Brink et al.13

Step 2: Inclusion RCT

If patients scored above the cutoff of the anxiety and/or depression questionnaire, a trained psychologist performed a diagnostic psychiatric interview (Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Child and Parent Versions [ADIS-C/P]48) by telephone to determine the severity of the symptoms using age-appropriate severity rating scales. The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale49 (PARS; 10–20 years; cutoff ≥18) and the Hamilton Anxiety rating scale50, 51 (HAM-A; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥15) were used for anxiety symptoms. Depression was rated using the Child Depression Rating Scale Revised52 (CDRS-R; 10–12 years; cutoff ≥40), the Adolescent Depression Rating Scale Revised53 (ADRS-R; 13–20 years; cutoff ≥20), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale54, 55 (HAM-D; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥17). A psychiatric disorder was defined as meeting criteria for an anxiety or depressive disorder on the ADIS-C/P and a score equal to or above the clinical cutoff on the rating scale. Patients with subclinical anxiety/depression (elevated symptoms of anxiety and/or depression not meeting the criteria for a psychiatric disorder) were eligible for randomization. Patients with an anxiety/depressive disorder were directly referred for psychological treatment and were excluded from the RCT as it would have been unethical to randomize patients to the CAU condition.

Randomization

Patients with subclinical anxiety and/or depression were randomized to CBT+CAU or CAU with a 1:1 ratio. An independent biostatistician provided a computer-generated blocked randomization list with randomly chosen block sizes (with a maximum of 6) and stratification by center using the blockrand package in the R software package, thereby providing numbered envelopes per center. After randomization, treatment in the CBT+CAU group started within a maximum of 4 weeks. The physicians assessing disease activity and the psychologist conducting the diagnostic interviews were blinded to the outcome of randomization. As patients could not be blinded, they were explicitly asked not to discuss the outcome of randomization with their treating physician.

Intervention

The Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Therapy (PASCET) is a manual-based CBT protocol, originally designed to treat depression.56 In this study, the PASCET–Physical Illness (PASCET-PI) was used, an IBD-specific modification that encompasses the illness narrative (ie, perceptions and experiences of having IBD), disease-specific psychoeducation, techniques for coping with pain, social skills training, and emphasis on IBD-related cognitions and behaviors.57 The protocol was modified to treat anxiety as well, and adjustments were made to make it age appropriate for patients aged 21–25 years. Participants received 10 weekly sessions over a timespan of 12 weeks (6 face-to-face, 4 by telephone), 3 additional family sessions (for patients aged <18 years; voluntary for patients aged >18 years who were living with their parents), and, after the first 12 weeks, 3-monthly booster sessions. Patients were considered treatment completers if they attended at least 8 sessions. The therapy was provided by all licensed (health care/CBT) psychologists, who received onsite training from the developer (E.M. Szigethy) of the PASCET-PI and executed the therapy in their own hospital or center.

CAU consisted of regular medical appointments with the (pediatric) gastroenterologist every 3 months, involving a 15–30-minute consultation discussing overall well-being, disease activity, results of diagnostics tests, medication use, and future diagnostic/treatment plans, but no psychological intervention.

Sample Size and Power

In our previously published study protocol, the primary outcome was defined as the relapse rate per group in the first year after randomization.29 As the study continued and inclusion appeared challenging, we decided to also include 21–25-year-old patients and re-estimate the sample size.58 Adapting the primary outcome to time to first relapse reduced the required sample size. The literature shows that, in general, approximately 40% of IBD patients have at least 1 relapse per year.59, 60 Based on expert opinion and previous studies,61, 62 a 30% difference was expected between the 2 groups (CBT survival rate, 0.6; CAU survival rate, 0.9). To detect a difference of 0.3 in survival rate after 52 weeks of follow-up, with a 2-sided significance level of 5% and 80% power, 37 patients were needed in each group. With 65 patients in remission at baseline, the study had a power of 77%.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic and clinical characteristics for the entire cohort and for each treatment group. T, chi2/Fisher exact, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used, where appropriate, to assess baseline differences between treatment groups.

For the primary outcome, time to first relapse, survival analyses were performed. Kaplan-Meier curves were tested with a 2-sided log-rank test. For this analysis, patients with a relapse at baseline were excluded. For the longitudinally measured secondary outcomes, clinical disease activity, CRP, and calprotectin, differences between the groups were assessed using linear mixed effects models to account for the correlations in the repeated measurements. All 4 clinical disease activity scores were converted to a 0–1 score (Supplementary Table 1, Step 1). This pooled disease activity score enabled us to include all patients in 1 analysis. As all 3 secondary outcomes had a non-normal distribution, transformations were done to assure normality. CRP and calprotectin were transformed using the natural logarithm. For pooled clinical disease activity, a 2-step logistic transformation was performed (Supplementary Table 1, Step 2 and 3). In all 3 linear mixed models, the treatment condition (result of randomization), time in months, and the interaction between time and treatment were added in the specification of the fixed effects. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to specify the random effects. With the LRT, the model with a random intercept only (covariance structure: identity) was compared with the model with both a random intercept and a random slope (covariance structure: unstructured). Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) was applied as the estimation method. Assumptions of the models were checked using residual plots. Considering the previous findings in pediatric patients,25 exploratory analyses were performed in patients 10–18 years of age.

All analyses were performed based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. For patients with missing and/or incomplete assessments, only available data were used. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using SPSS, version 24.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Erasmus Medical Center and of each participating center.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

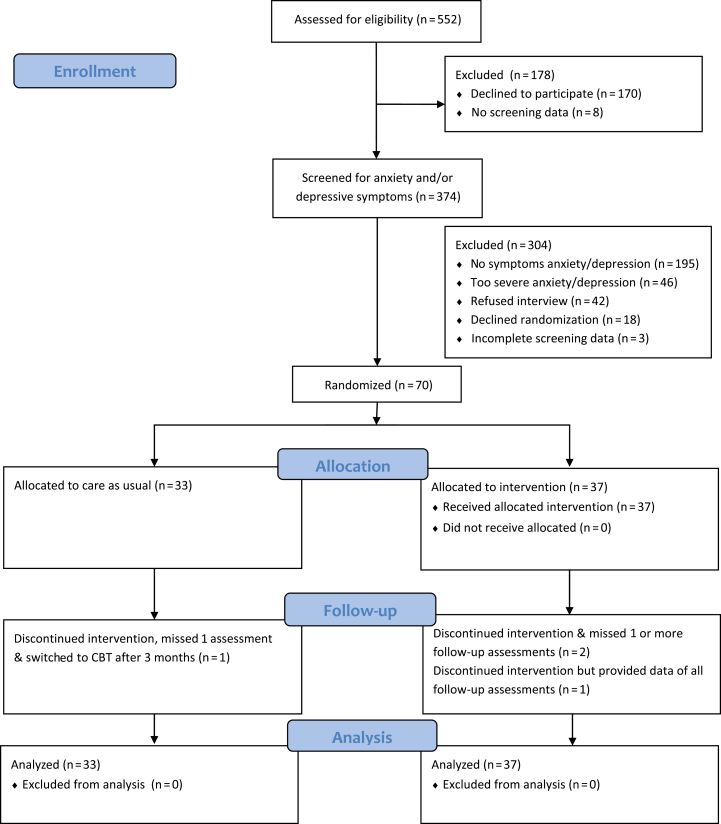

A total of 552 patients were eligible to participate, of whom 374 patients completed the anxiety and depression questionnaires at baseline. Of the 371 patients who completed both questionnaires, 47.4% experienced elevated symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Of the 134 patients who participated in the diagnostic psychiatric interview, 46 patients (34%) met the criteria for a psychiatric disorder, and 88 patients (66%) experienced subclinical symptoms of anxiety and/or depression.13 Of these 88, 70 patients (80%) gave consent for randomization (CBT+CAU: n = 37; CAU: n = 33) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Consort study flowchart.

Of all randomized patients, 68.6% were female, ±50% were <18 years of age (median age [interquartile range], 18.27 [14.5–22.37] years), 51.4% had a diagnosis of CD, 80.9% had a Western ethnicity, and socioeconomic status was, respectively, low, middle, and high in 17.1%, 36.8%, and 45.6% (data not shown). Patients were included based on anxiety symptoms (71.4%), depressive symptoms (4.3%), or both (24.3%). Five patients experienced a relapse of IBD at baseline.

There were no baseline differences between the CBT+CAU group and the CAU group for demographic and disease characteristics, except for disease duration (P = 0.03) and corticosteroid dependency in the past 3 months (P = 0.03) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| CBT (n = 37), Median (IQR) or No. (%) | CAU (n = 33), Median (IQR) or No. (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male | 10 (27) | 12 (36.4) | 0.40 | |

| Age, y (% <18 y) | 18.5 (16.1–23.0) (48) | 18.0 (13.7–21.8) (51) | 0.37 | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 15.7 (12.8–17.8) | 14.9 (11.2–19.6) | 0.90 | |

| Duration of disease, y | 2.6 (1.8–5.3) | 1.3 (0.7–3.3) | 0.03 | |

| Disease type | CD | 18 (48.6) | 18 (54.5) | 0.84 |

| UC | 14 (37.8) | 12 (36.4) | ||

| IBD-U | 5 (13.5) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Paris classification at diagnosisa | CD locationb (n = 36) | 0.83 | ||

| L1 | 4 (22.2) | 5 (27.8) | ||

| L2 | 6 (33.3) | 4 (22.2) | ||

| L3 | 8 (44.4) | 9 (50.0) | ||

| + L4a/L4b | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | 1.00 | |

| CD: behavior | 1.00 | |||

| Nonstricturing, nonpenetrating | 18 (100) | 18 (100) | ||

| Stricturing, penetrating, or both | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Perianal disease | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | 1.00 | |

| UC: extent (n = 34)c | 0.07 | |||

| Limited: (E1+E2) | 11 (57.9) | 4 (26.7) | ||

| Extensive: E3+E4 | 8 (42.1) | 11 (73.3) | ||

| UC: severity, ever severe | 1 (5.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.15 | |

| Clinical disease activityd | Remission | 29 (78.4) | 26 (78.8) | 0.55 |

| Mild | 6 (16.2) | 7 (21.2) | ||

| Moderate | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| CRP, mg/L | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 1 (0.3–4.4) | 0.19 | |

| Fecal calprotectin, µg/g | 67.5 (24.8–318.5) | 169 (19.5–563.0) | 0.73 | |

| Current medication use | Aminosalicylates | 18 (48.6) | 12 (36.4) | 0.30 |

| Immunomodulators | 17 (45.9) | 16 (48.5) | 0.17 | |

| Biologicals | 8 (21.6) | 12 (36.4) | 0.66 | |

| Corticosteroidse | 2 (5.4) | 3 (9.1) | 0.83 | |

| Enemasf | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | 0.12 | |

| No medication | 2 (5.4) | 1 (3) | 1.00 | |

| Steroid dependence past 3 mo | 3 (8.1) | 9 (27.3) | 0.03 | |

| Baseline relapse | 4 (10.0) | 1 (3.0) | 0.36 | |

| Relapse preceding year | 15 (40.5) | 10 (30.3) | 0.39 | |

| Bowel resection in history | 3 (8.1) | 2 (6.1) | 1.00 | |

| EIMg | 7 (18.9) | 4 (12.1) | 0.44 | |

| Hospital type | University hospital | 16 (43.2) | 15 (45.5) | 0.85 |

| Anxiety and/or depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | 30 (81.1) | 20 (60.6) | 0.08 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Both | 7 (18.9) | 10 (30.3) |

aUC includes IBD-U patients.

bL1: ileocecal; L2: colonic; L3: ileocolonic; L4a: upper gastrointestinal tract proximal; and L4b: distal from the Treitz ligament.

cE1: proctitis; E2: left-sided colitis distal to the splenic flexure; E3: extensive colitis distal to the hepatic flexure; E4: pancolitis.

dBased on clinical disease activity scores (pMayo, PCDAI, PUCAI, CDAI).

ePrednisone (oral and intravenous) and budesonide (oral).

fAminosalicylate or corticosteroid enemas.

gEIM: involving skin (31.5%), eyes (1.75%), liver and biliary tracts (10.5%), joints (33.3%), and bones (28.1%).

Protocol Adherence

Thirty-four out of 37 (92%) patients allocated to CBT+CAU completed ≥8 CBT sessions (treatment completers). The other 3 patients attended 5, 3, and 1 sessions. The mean number of treatment sessions attended was 9.38.

During follow-up, 2 patients in the CAU group (at 6 and 9 months) and 1 patient in the CBT+CAU group (at 3 months) developed severe symptoms that met the criteria for a psychiatric disorder (2 patients with anxiety disorders and 1 with anxiety and depressive disorder) and were directly referred for psychiatric/psychological help, whereas follow-up data were collected for the ITT analysis. Of these patients, all follow-up assessments were completed. Furthermore, on persistent parental request, 1 patient was switched from the CAU to the CBT+CAU group after 3 months; follow-up data were collected, and analyses were performed according to the ITT principle (CAU group). Three patients missed 1 or more follow-up assessments (1 CAU group, 2 CBT+CAU group): 2 patients missed the 6-month visit, and 1 patient missed all visits after baseline. Nine-month medical data were collected for 26 patients.

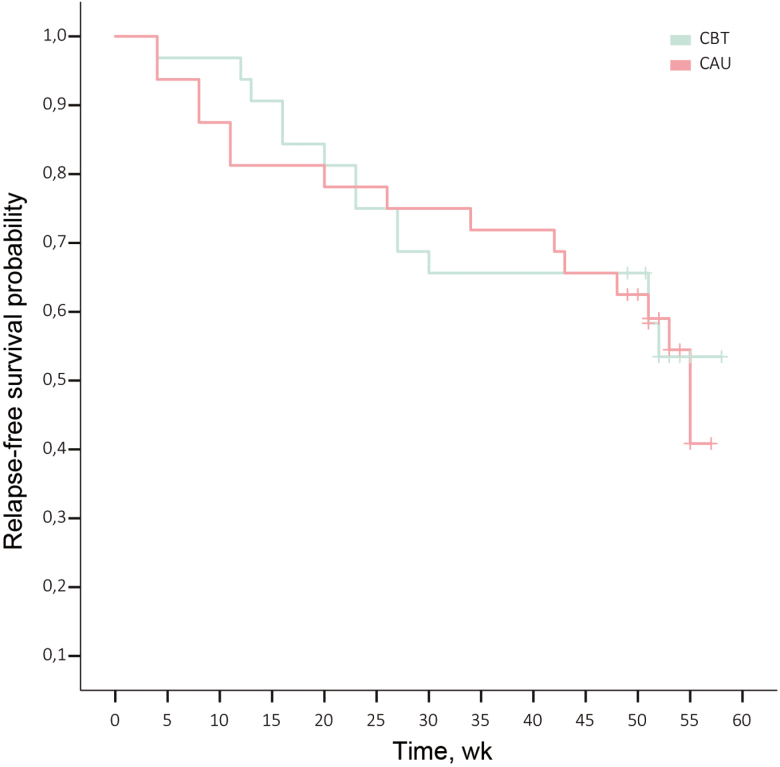

Primary Outcome: Time to First Relapse

During 52 weeks of follow-up, 16 patients (43.2%) in the CBT+CAU group and 16 patients (48.5%) in the CAU group experienced 1 or more relapse. For the 65 patients in remission at baseline, no difference in time to relapse between groups was found (P 0.915) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Survival curve time to first flare.

Secondary Outcomes

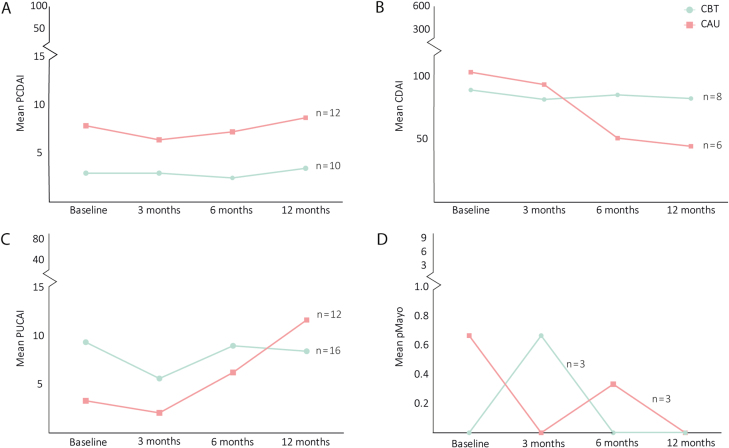

Clinical disease activity

Linear mixed model analysis showed no difference in the course of (pooled) clinical disease activity over time between both groups (interaction time*treatment not significant) (Table 2). In addition, no significant changes were found within either the CBT+CAU group or the CAU group (Table 2). Raw means of the 4 clinical disease activity scores over time are displayed in Figure 3.

TABLE 2.

Results of Linear Mixed Models (n = 70)

| Time | Interaction Time*Treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P | ||

| Clinical disease activity | |||||||

| Within group | CBT | –0.006 | –0.052 to 0.040 | 0.80 | |||

| CAU | 0.012 | –0.036 to 0.061 | 0.61 | ||||

| Between groups | –0.019 | –0.085 to 0.048 | 0.59 | ||||

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | |||||||

| Within group | CBT | –0.015 | –0.050 to 0.020 | 0.41 | |||

| CAU | 0.021 | –0.015 to 0.057 | 0.24 | ||||

| Between groups | –0.036 | –0.086 to 0.014 | 0.158 | ||||

| Fecal calprotectin, µg/g | |||||||

| Within group | CBT | –0.019 | –0.075 to 0.037 | 0.50 | |||

| CAU | 0.005 | –0.052 to 0.063 | 0.851 | ||||

| Between groups | –0.025 | –0.11 to 0.056 | 0.543 |

“Within group” displays whether there was a significant (P < 0.05) change over time within either the CBT or the CAU group. “Between group” reflects whether the course over time was significantly different between the CAU and CBT group (P interaction time*treatment < 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Raw means of clinical disease activity scores over time.

Similarly, exploratory analysis in patients aged <18 years (n = 35) showed no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.20) or within the CBT+CAU group (P = 0.92) or the CAU group (P = 0.085) (data not shown). In addition, there was no difference in CD vs UC patients (data not shown).

Inflammatory markers: fecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein

For CRP and fecal calprotectin, no significant differences were found between the CAU group and the CBT+CAU group (interaction term not significant). In addition, no significant change was found over time within each group (Table 2; raw means are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1).

Exploratory analysis in 10–18-year-old patients (n = 35) showed that for calprotectin, the interaction between time and treatment was significant (Beta coefficient [β], –0.11, 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.195 to –0.031; P = 0.008). A statistically significant increase was seen in the CAU group over time (β, 0.085; 95% CI, 0.028 to 0.143; P = 0.004), whereas no change was found in the CBT+CAU group (β, –0.028; 95% CI, –0.087 to 0.031; P = 0.35). Reverse transformation to the original scale revealed a 9% increase per month in the CAU group (data not shown). For CRP, no change was observed within the CBT+CAU group over time (β, –0.012; 95% CI, –0.070 to 0.046; P = 0.68), whereas a significant increase in the CAU group was observed (β, 0.069; 95% CI, 0.011–0.13; P = 0.022). Reverse transformation to the original scale revealed a 7% increase per month in the CAU group. The interaction between time and treatment approached significance (β, –0.081; 95% CI, –0.164 to 0.001; P = 0.054) (data not shown). For both CRP and calprotectin, there was no difference between CD and UC patients (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study was the first to investigate the effect of CBT vs CAU only on subsequent disease course in young IBD patients with subclinical anxiety and/or depression. We showed that time to first relapse in the first year after randomization did not significantly differ between patients in the CBT+CAU vs the CAU group. Furthermore, (pooled) clinical disease activity, CRP, and fecal calprotectin also did not significantly change over time between the CBT+CAU group and the CAU group or within each group. Exploratory analyses in 10–18-year-old patients suggested a significantly different course of fecal calprotectin between groups, with an increase in the CAU group. In addition, the difference in the course of CRP between the CAU group and the CBT+CAU group approached significance, with an increase in the CAU group. These results could suggest a possible positive effect of CBT on fecal calprotectin and CRP levels in 10–18-year-old patients, with perhaps a positive influence on intestinal inflammation in the longer term. However, this should be replicated in larger patient cohorts.

Within the “brain–gut axis,” it is hypothesized that a decrease in anxiety/depressive symptoms is accompanied by a decrease in (intestinal) inflammation, and vice versa, and that it may promote sustained remission. In the current trial, both groups equally improved in anxiety/depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) after 363 and 6–12 months (Stapersma et al., submitted). Therefore, it is not surprising that we did not find a difference in clinical outcomes. As an improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms within the CBT+CAU and CAU groups over time was observed,63 improvement in clinical outcomes within both groups could have been expected. Low baseline clinical disease activity and low baseline inflammatory activity could also explain why we did not find an improvement in clinical disease activity scores, CRP, or calprotectin in the whole sample.

Several studies have reported on the effect of CBT on clinical disease course, specifically relapse rate, clinical disease activity, and CRP. Time to relapse has not been studied before. Three studies included adolescent IBD patients,24, 25, 64 and 3 included adult65–68 IBD patients. Only 2 pediatric studies selected patients based on anxiety24 or depression.25 In all these studies, mostly patients in clinical remission or with mildly active disease were included. At first, Levy et al. tested the effectiveness of a brief (3 session) CBT (vs education support condition) in 185 adolescent IBD patients unselected for anxiety and depression and mainly in disease remission (63%). In line with our results, they reported no difference in relapse rate between the 2 conditions. An exploratory analysis in patients who experienced ≥2 flares in the year before the study showed a decrease in relapse rate following CBT (CBT, 16.7%; CAU, 52.9%; P = 0.04).64 However, this subanalysis was limited by the liberal definition of relapse, without considering objective items such as treatment intensification. Second, Szigethy et al. studied the effect of 2 psychotherapies (CBT vs supportive nondirective therapy) in 217 adolescents with IBD and minor/major depression. Although it is not reported in the article, looking at the mean PCDAI and PUCAI scores, it can be assumed that most patients were in remission or had mildly active disease. An improvement in depressive symptoms, HRQOL, and pooled clinical disease activity after 3 months was found in both groups. However, it should be noted that this improvement corresponded with a rather small, not clinically relevant decrease in raw disease activity scores of ±10 points on the PCDAI/PUCAI that was reported to be larger in the CBT group.25 A third study of interest was performed by Mickocka-Walus et al.; it investigated whether adding 10 sessions (face-to-face or online) of CBT to standard medical care influenced clinical disease activity in 176 unselected adult IBD patients. Approximately 75% of patients had quiescent disease at baseline. No differences in remission rates after 12 months (73.2% CBT vs 71.7% CAU) or in clinical disease activity scores or CRP levels after 12 and 24 months were reported.66, 67

In conclusion, studies reporting on the effect of CBT or other psychotherapies on disease course in IBD patients with (sub)clinical anxiety and/or depression are scarce.69 Only 1 trial in pediatric IBD patients in remission or with mildly active disease reported a small improvement in clinical disease activity after CBT (and supportive nondirective therapy).25 As far as we know, no studies are available investigating the effect of psychotherapy on disease course in IBD patients with at least moderately active disease and suffering from (sub)clinical anxiety/depression.

Our finding that CBT did not influence time to relapse, relapse rates, or clinical disease activity is in accordance with the 2 previous studies in patients unselected for anxiety/depression.64, 66 In contrast, Szigethy et al. did find a small improvement in disease activity over time in both psychotherapy groups, favoring CBT.25 In addition, due to the short follow-up, it is unclear how this improvement would evolve in the longer term. It should be noted that Szigethy et al.’s study is the only RCT to date performed in patients selected for emotional symptoms (minor/major depression).

It is possible that CBT is more effective in improving disease course (reducing inflammation) in patients with more severe anxiety/depression, as more improvement in psychological symptoms can be gained. This could be supported by Szigethy et al., who also included patients with major depression (±60%). In studies that did not select patients based on anxiety/depression,64, 66, 67 no improvement in clinical disease activity was found, and only 1 study68 found a decrease in anxiety/depressive symptoms.

Considering that we did not find an effect of CBT on clinical disease course, it is possible that CBT has an effect on other measures of disease course, such as disability, health care use (eg, visits to the emergency room), and school absenteeism. This is supported by a study by Keerthy et al., reporting a significant reduction in IBD-related health care use following CBT.70 We attempted to analyze school absenteeism in our sample but could only collect data from patients aged 10–18 years because in the Netherlands only elementary and high schools register (reasons for) absenteeism. For 18 out of 35 children, data were available (CBT: n = 6; CAU: n = 12), unfortunately, due to high heterogeneity of the registration methods used and missing data, analysis was not possible.

It is not likely that baseline differences influenced our results. First, the longer disease duration in the CBT+CAU group could be accompanied by better coping strategies, providing an advantage in learning certain CBT-specific skills. As the improvement of psychological symptoms was similar in both groups63 (Stapersma et al. 2018, submitted) and disease course did not change over time, any influence of disease duration is unlikely. Second, baseline corticosteroid dependency in the past 3 months was higher in the CAU group than in the CBT+CAU group (27.3% vs 8.1%). This could indicate higher disease activity in the CAU group. However, considering that there were no differences in other markers of disease activity (baseline clinical disease activity scores, relapse rates, CRP, fecal calprotectin, and current steroid use) between both groups (Table 1), it is plausible that this baseline difference was attributable to a type I error.

Strengths and Limitations

Major strengths of this study are its multicenter RCT design and the unique study population—pediatric and young adult IBD patients from regional and tertiary medical centers—which increase generalizability. In addition, and contrary to other studies,24, 25 we included patients based on subclinical anxiety and/or depression, as these symptoms often occur together. Moreover, because CBT has previously been found to have a significant effect over and above placebo in previous studies,71 CAU was chosen as a control condition because it resembles current clinical care best. These 2 aspects combined provided us with the opportunity to determine whether CBT prevents the development of subclinical disorders into clinical disorders. Additionally, we included all IBD types, and pooling of clinical disease activity scores enabled us to study disease activity for all patients simultaneously. To investigate the course of disease, we followed patients for 1 year after randomization, which is longer than in previous studies.25, 65, 68 Furthermore, the use of an IBD-specific CBT protocol and the low attrition, especially when compared with other studies,25, 64, 66, 67 strengthen our study. Lastly, we were the first to incorporate fecal calprotectin levels and to assess the effect of CBT on CRP levels in children.

Inevitably, our trial has some limitations. First of all, the study was relatively underpowered, as not all eligible patients were willing to participate in our trial with a time-consuming psychological intervention. This is a well-known problem in RCTs with a psychological intervention.25, 66 Another limitation is the relatively unequal result of randomization (37 vs 33), most likely due to randomization with random block sizes. Furthermore, the large number of patients with a Western ethnicity (80.9%) reduces the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, considering that the majority of included patients were in clinical remission at baseline, we could not investigate whether the effect of CBT on disease activity would be greater in a population with active disease. Moreover, it would have been interesting to have included factors such as treatment adherence or IBS symptoms because they can impact disease outcomes but are also affected by psychological symptoms. As previously mentioned, the effectiveness of CBT on psychological outcomes is detailed in separate publications (Stapersma et al. 2018, submitted).63 It is known that parental behavior and psychopathology are important determinants for children’s behavior. Therefore, a questionnaire measuring parental anxiety and depression was incorporated in the study design, which will be part of future analyses. Lastly, impact of disease was evaluated using disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires, questionnaires that partly assess impact of disease. Unfortunately, validated patient-reported outcomes of, for example, disease burden (symptom burden or disability) are not available for pediatric IBD. If available, they would have provided additional insight regarding experienced disease burden. Similarly, we did not include a validated measure of fatigue in our design, although this is a common invalidating complaint in IBD patients, who are possibly responsive to psychological interventions.

Directions for Future Research

The variation in study design and mixed results from the available studies investigating the effect of CBT on disease course force us to be careful in drawing conclusions. Large, sufficiently powered studies that factor in high attrition rates in sample size calculation are necessary. In addition, several subgroups of patients (eg, severe anxiety/depression, patients with at least moderately active IBD) need to be studied to determine whether there are certain patient groups in which CBT does influence disease course. Furthermore, other formats of psychotherapeutic interventions and other treatment modalities (eg, group or e-therapy) with varying intensity should also be investigated in patients with (sub)clinical anxiety/depression, as most studies have been performed in patients unselected for psychological problems.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, CBT added to CAU does not influence subsequent clinical disease course in young IBD patients with subclinical anxiety and/or depression. However, the findings suggest that CBT may have a positive effect on inflammatory markers in pediatric patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to the patients and parents who participated in this study and to the clinicians at participating hospitals: Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam (coordinating center; L. de Ridder, J.C. Escher, M.A.C. van Gaalen, C.J. van der Woude), Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht (T.A. Korpershoek, R. Beukers, S.D.M. Theuns-Valks), Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam (M. Groeneweg, F. de Bruijne), Haga Hospital and Juliana Children’s Hospital, The Hague (D.M. Hendriks, R.J.L. Stuyt, M. Oosterveer, S. Brouwers, J.A.T. van den Burg), Amphia Hospital, Breda (H.M. van Wering, A.G. Bodelier, P.C.W.M. Hurkmans), Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden (M.L. Mearin, A.E. van der Meulen). In addition, we thank de developer of the PASCET-PI, Prof. E.M. Szigethy, for her onsite training of the therapists. We thank Adine Klijn, Lotte Vlug, and Lavinia Sajtos for helping us with data preparation for analysis.

Supported by: This work was supported by Stichting Crohn en Colitis Ulcerosa Fonds Nederland/Maag Lever Darm Stichting (grant 14.307.04), Fonds NutsOhra (grant 1303-012), Stichting Theia (grant 2013201), and Stichting Vrienden van het Sophia (SSWO; grant 985).

Conflicts of interest: J.C.E. has received financial support from MSD (research support), Janssen (advisory board), and AbbVie (advisory board), but the support was unrelated to the current study. For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daniel JM. Young adults’ perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kemp K, Griffiths J, Lovell K. Understanding the health and social care needs of people living with IBD: a meta-synthesis of the evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6240–6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greenley RN, Hommel KA, Nebel J, et al. A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:857–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mackner LM, Greenley RN, Szigethy E, et al. Psychosocial issues in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:449–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hummel TZ, Tak E, Maurice-Stam H, et al. Psychosocial developmental trajectory of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Regueiro M, Greer JB, Szigethy E. Etiology and treatment of pain and psychosocial issues in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):430–439.e434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brooks AJ, Rowse G, Ryder A, et al. Systematic review: psychological morbidity in young people with inflammatory bowel disease - risk factors and impacts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016;87:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stapersma L, van den Brink G, Szigethy EM, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:496-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel JB, et al. Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:829–835.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van den Brink G, Stapersma L, Vlug LE, et al. Clinical disease activity is associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:358–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reigada LC, Satpute A, Hoogendoorn CJ, et al. Patient-reported anxiety: a possible predictor of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease health care use. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2127–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alexakis C, Kumar S, Saxena S, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the impact of a depressive state on disease course in adult inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gracie DJ, Guthrie EA, Hamlin PJ, et al. Bi-directionality of brain-gut interactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1635–1646.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, et al. Does psychological status influence clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic gastroenterological diseases: an observational cohort prospective study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bitton A, Dobkin PL, Edwardes MD, et al. Predicting relapse in Crohn’s disease: a biopsychosocial model. Gut. 2008;57:1386–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh H, Nugent Z, Brownell M, et al. Academic performance among children with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1128–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Boer AG, Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Stokkers PC, et al. Employment status, difficulties at work and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1130–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. ECCO -EpiCom The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:322–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:930–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reigada LC, Benkov KJ, Bruzzese JM, et al. Integrating illness concerns into cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and co-occurring anxiety. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2013;18:133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Szigethy E, Bujoreanu SI, Youk AO, et al. Randomized efficacy trial of two psychotherapies for depression in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2704–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT NPT Group CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garber J, Weersing VR. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: implications for treatment and prevention. Clin Psychol (New York). 2010;17:293–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van den Brink G, Stapersma L, El Marroun H, et al. Effectiveness of disease-specific cognitive-behavioural therapy on depression, anxiety, quality of life and the clinical course of disease in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial (HAPPY-IBD). BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Statistics Netherlands. Standaard Beroepen Classificatie 2010. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Utens EMWJ, van Rijen EH, Erdman RAM, et al. Rotterdam’s Kwaliteit van Leven Interview. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Erasmus MC, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muris P, Bodden D, Hale W, et al. SCARED-NL. Vragenlijst Over Angst en Bang-Zijn bij Kinderen En Adolescenten. Handleiding bij de Gereviseerde Nederlandse Versie van de Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. Amsterdam: Boom Test Uitgevers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Croon EM, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Hugenholtz NIR, et al. Drie vragenlijsten voor diagnostiek van depressie en angststoornissen. TBV – Tijdschrift voor Bedrijfs- en Verzekeringsgeneeskunde. 2005;13(4):114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Timbremont B, Braet C, Roelofs J.. Children’s Depression Inventory. Handleiding (Herziene Uitgave). Amsterdam: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van der Does AJW. BDI-II-NL Handleiding. De Nederlandse Versie van de Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. Lisse: Harcourt Test Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Turner D, Griffiths AM, Walters TD, et al. Mathematical weighting of the pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) and comparison with its other short versions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:512–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bessissow T, Lemmens B, Ferrante M, et al. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1684–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Minami N, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Tacrolimus or infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis: short-term and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2:e000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heida A, Park KT, van Rheenen PF. Clinical utility of fecal calprotectin monitoring in asymptomatic patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and practical guide. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. REACH Study Group Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:863–73; quiz 1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. ECCO 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition ESPGHAN revised Porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Siebelink BM, Treffers PDA.. Nederlandse Bewerking van het Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV Child Version van Silverman & Albana. Lisse/Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ginsburg GS, Keeton CP, Drazdowski TK, et al. The utility of clinicians ratings of anxiety using the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS). Child Youth Care Forum. 2011;40(2):93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matza LS, Morlock R, Sexton C, et al. Identifying HAM-A cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19:223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Poznanski EO, Mokros H.. Children’s Depression Rating Scale Revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Revah-Levy A, Birmaher B, Gasquet I, et al. The Adolescent Depression Rating Scale (ADRS): a validation study. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, et al. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weisz JR, Thurber CA, Sweeney L, et al. Brief treatment of mild-to-moderate child depression using primary and secondary control enhancement training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Szigethy E, Whitton SW, Levy-Warren A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Heida A, Dijkstra A, Groen H, et al. Comparing the efficacy of a web-assisted calprotectin-based treatment algorithm (IBD-live) with usual practices in teenagers with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martinelli M, Giugliano FP, Russo M, et al. The changing face of pediatric ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, Prosberg MV, et al. Hospitalisation, surgical and medical recurrence rates in inflammatory bowel disease 2003-2011—a Danish population-based cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8: 1675–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boye B, Lundin KE, Jantschek G, et al. INSPIRE study: does stress management improve the course of inflammatory bowel disease and disease-specific quality of life in distressed patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease? A randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1863–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Keefer L, Taft TH, Kiebles JL, et al. Gut-directed hypnotherapy significantly augments clinical remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stapersma L, van den Brink G, van der Ende J, et al. Effectiveness of disease-specific cognitive behavioral therapy on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in youth with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43:967–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Levy RL, van Tilburg MA, Langer SL, et al. Effects of a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention trial to improve disease outcomes in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2134–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCombie A, Gearry R, Andrews J, et al. Does computerized cognitive behavioral therapy help people with inflammatory bowel disease? A randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy has no effect on disease activity but improves quality of life in subgroups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: 24-month data from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24:127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schoultz M, Atherton I, Watson A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease patients: findings from an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, et al. Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Keerthy D, Youk A, Srinath AI, et al. Effect of psychotherapy on health care utilization in children with inflammatory bowel disease and depression. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:658–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.