Abstract

Objective

Patient-centredness (PC) has particularly grown in relevance in health services research as well as in politics and there has been much research on its conceptualisation. However, conceptual work neglected the patients’ perspective. Thus, it remains unclear which dimensions of PC matter most to patients. This study aims to assess relevance and current degree of implementation of PC from the perspective of chronically ill patients in Germany.

Methods

We conducted a Delphi study. Patients were recruited throughout Germany using community-based strategies (eg, newspapers and support groups). In round 1, patients rated relevance and implementation of 15 dimensions of PC anonymously. In round 2, patients received results of round 1 and were asked to re-rate their own results. Participants had to have at least one of the following chronic diseases: cancer, cardiovascular disease, mental disorder or musculoskeletal disorder. Furthermore, patients had to be at least 18 years old and had to give informed consent prior to participation.

Results

226 patients participated in round 1, and 214 patients in round 2. In both rounds, all 15 dimensions were rated highly relevant, but currently insufficiently implemented. Most relevant dimensions included ‘patient safety’, ‘access to care’ and ‘patient information’. Due to small sizes of subsamples between chronic disease groups, differences could not be computed. For the other subgroups (eg, single disease vs multi-morbidity), there were no major differences.

Conclusion

This is one of the first studies assessing PC from patients’ perspective in Germany. We showed that patients consider every dimension of PC relevant, but currently not well implemented. Our results can be used to foster PC healthcare delivery and to develop patient-reported experience measures to assess PC of healthcare in Germany.

Keywords: patient-centredness, chronic diseases, healthcare delivery, Delphi study, patients’ perspective

Strengths and limitations of this study.

No rating of dimensions of patient-centredness from the patients’ perspective available yet.

Extensive inclusion of patients’ perspectives within the Delphi study.

No restriction to a specific regional area through nation-wide community-based strategies.

Possibility for participants to give written feedback in order to enhance quality of given answers.

Limitation to only four chronic disease groups.

Introduction

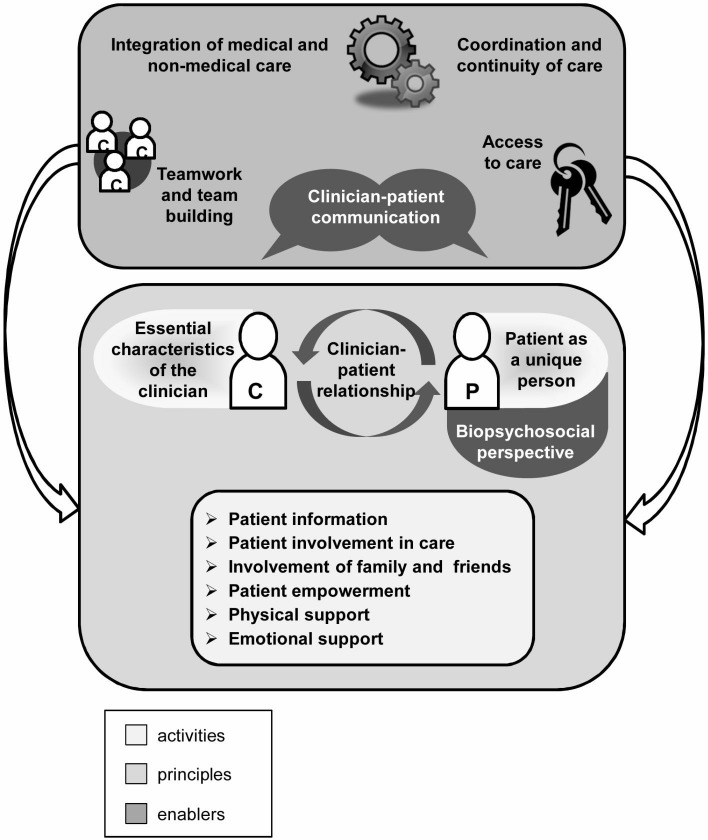

Over the last years, the concept of patient-centredness (PC) has been widely discussed. More and more, the terms person-centredness1 2 and people-centredness3 also appear in the literature, either being used synonymously to PC or converging around central ideas. Its relevance in politics, research and healthcare practice has been growing constantly.4–6 In Germany, the Law on Patients’ Rights5 mandates certain aspects of PC care such as the right for comprehensible and comprehensive patient information. However, there is no national recommendation for the implementation of PC care in Germany yet. Many studies showed a positive association of PC with relevant outcomes such as patient satisfaction, well-being and adherence,7 which are especially relevant in chronic disease management. Nevertheless, there has been a lack of conceptual clarity regarding the use of the term of PC.8–13 Scholl and colleagues12 closed this gap by developing an integrative generic model derived from literature extracting 15 dimensions of PC (see figure 1). This model was validated by assessing the views of different healthcare stakeholders on its relevance and clarity.14 Although some representatives of patient organisations participated in this assessment, the perspective of the recipients of PC care, the patients themselves, was under-represented. In summary, without the patients’ perspective, the conceptualisation of PC is still missing its most crucial aspect: the assessment and evaluation of PC in healthcare from the view of patients.15–17

Figure 1.

Integrative model of patient-centredness.

There are only few international studies investigating the patients’ assessment of PC,18 19 without any published studies from Germany. Thus, we do not know what patients consider relevant about PC, nor how patients view the current degree of implementation of PC in the German healthcare system. It is a system in which healthcare coverage is universal, mandatory and offers extensive services. Government delegates decision-making powers to self-regulated organisations of payers and providers. While outpatient care is mainly delivered in one-physician or two-physician practices on a fee-for-service payment model, hospitals mainly deliver inpatient care on case-based payment model.20 21 Yet, in order to foster PC in Germany, it is crucial to know what aspects of PC are relevant to patients and how well these aspects are already implemented, as it allows prioritising aspects especially relevant or not yet implemented.

Therefore, this study aims to close this gap by assessing relevance and current degree of implementation of different dimensions of PC from the patients’ perspective in Germany. Assessing relevance and current degree of implementation of different aspects of PC can therefore be seen as the first steps in achieving a more PC healthcare.

This Delphi study was conducted as part of the study ‘Assessment of patient-centeredness through patient-reported experience measures (ASPIRED).22 Within the study ASPIRED, a patient-reported experience measure will be developed to foster PC care.

Methods

Study design

We used a Delphi study, comparable with the expert validation study mentioned earlier.14 A Delphi study consists of several rounds. In each round after the first, participants get their own ratings as well as the median ratings of all participants in the previous round. This procedure generates the possibility for participants to share their opinion from different regional locations without the threat of some participants dominating the discussion.23 It aims to reach high group consensus through a structured and anonymous group discussion.24 Like Zill and colleagues14 or van Rijssen and colleagues,25 we planned to perform two rounds prior to conducting the first round. However, if we had seen major discrepancies after two rounds, we would have performed another round, if necessary.

Preparation of the Delphi study: adaptation of the model of PC using cognitive interviews

We based our Delphi study on the integrative model of PC.12 14 In the first step, the scientific model was adapted into a version comprehensible to patients (first version). Adaptation was done by group discussions in our research team (SZ, EC, PH, IS) in nine rounds. To make sentences easy to understand, we used dictionaries and recommendations on adaptation of wording and grammar.26 We then tested comprehensibility of the new version through cognitive interviews with patients. We recruited 10 patients through several community-based strategies (see section Delphi study) in order to get a heterogeneous sample regarding demographic variables (eg, age, first language, educational level). Participants had to have at least one of the following chronic diseases: cancer, cardiovascular disease, mental disorder or musculoskeletal disorder. In cognitive interviews, we handed out the first adapted version described earlier. Participants were asked to read each dimension step by step and explain in their own words how they understood the description. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed independently by two researchers (SZ, EC). According to the results, the model was revised (second version) in subsequent group discussions (SZ, EC, IS, PH).

Delphi study

Participants received the adapted integrative model of PC (second version) and were asked to rate relevance and current implementation from their perspective. For both aspects, a nine-point Likert scale (1=not relevant/not well implemented; 9=very relevant/well implemented) was given. In addition, we asked an open-ended question about whether any relevant aspects were missing in the model and whether they had any further comments (eg, regarding comprehensibility of descriptions). Based on answers to those open-ended questions, we adapted the model again (third version). In the second round of the Delphi study, patients received their own ratings from the first round again. Furthermore, we gave them the median rating of other participants in comparison. Following, we then asked participants to repeat their rating. For all dimensions with adapted descriptions, participants were also asked to rate whether the description worsened or improved with the adaptation (from 1=much worse to 9=much better).

For both rounds, participants could choose whether they wanted to participate online or via mail. Both versions were identical in terms of response format (see online supplementary appendix A1 for the mail-based version with adaptations (highlighted) made after round 1). For the online version, we used LimeSurvey.27 The study was conducted from June 2018 to August 2018. For each round, participants had 3 weeks to reply and there were 4 weeks between the two rounds. After completion of both rounds, participants received a compensation of 25€. Conducting the Delphi study as well as reporting of methods and results were based on the recommendations of Hasson and colleagues24 as well as of Jünger and colleagues.28

bmjopen-2019-031741supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)

Study population and recruitment

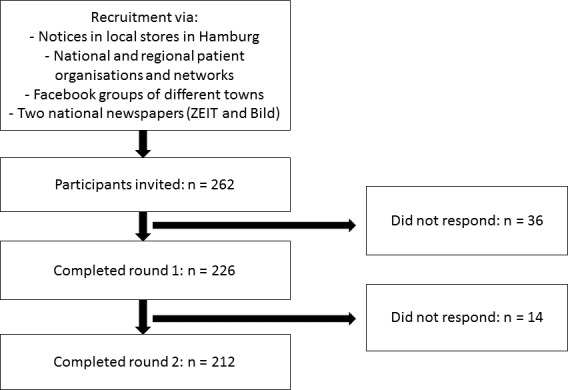

We aimed to include 200 patients in the study. We expected a drop-out rate of 15% between rounds 1 and 2. Thus, we aimed to include 240 in the first round. We recruited patients through different community-based strategies: (1) notices in local stores in Hamburg, (2) dissemination through national and regional patient organisations and networks, (3) Facebook groups of different towns and (4) two national newspapers (ZEIT and Bild). Participants could reach out to SZ and EC with the contact information provided on the notices and in emails. Since no member of the research team had direct contact with participants, the possibility of having influenced the participants’ judgements was reduced. Participants were included if they gave their informed consent by signing the informed consent letter (mail version) or by choosing ‘yes’ in a drop-down menu after a question whether they consent (online version), were 18 years or older and if they reported at least one disease from one of the aforementioned chronic disease groups. In figure 2, an overview illustrates the procedure.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for the Delphi study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research questions. However, during the development of the research proposal and prior to submission to the funding agency, we obtained collaboration agreements with several federal and regional patient organisations in order to secure field access and feasibility. Patient organisations were approached for that purpose. All gave us positive feedback on the study aims, acknowledging that more research is needed on patients’ experiences related to PC care. Thus, patient organisations supported recruitment of study participants by disseminating advertisement for study participation. No individual patient was involved in recruitment and conduct of the study. All study participants and every interested person in the public have the possibility to read and download regular project updates and study results on the project website (http://www.ham-net.de/de/projekte/projekt-aspired.html).

Data analyses

For the ratings, median, mean and SD were calculated for all participants using SPSS V.21.29 Demographic data were analysed accordingly, except for nominal items where we calculated frequencies. Consensus was examined by calculating distributions of answers per tertile (1–3; 4–6; 7–9) in comparison with Zill et al.14 We compared different subgroups due to potential differences in using the healthcare system including age groups (18–30 (young); 31–65 (middle aged); over 65 (older)), way of participation (mail vs online) and morbidity (single disease vs multi-morbidity). Open answers were analysed, summarised by two researchers and the student assistant (SZ, EC, Tanja Kloster) and reviewed in a group discussion (SZ, EC, IS).

Results

Adaptation of the integrative model into a comprehensible version

Within cognitive interviews, each participant understood generally well the patient version of PC (first version). Some participants wanted easier terms (eg, treatment (‘Behandlung’) instead of healthcare (‘Gesundheitsversorgung’)). We tested two versions: version A was not directed towards patients (‘Patients can contact their healthcare provider easily’), and version B was directed towards patients (‘You can contact your healthcare provider easily’). Nine out of 10 participants preferred personal pronouns (version B); thus, we adapted accordingly.

Delphi study

Characteristics of patients from the Delphi study

Two hundred and sixty-two patients, who reacted to the community-based recruitment strategies, fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate via letter or online in the first round of the Delphi study after having expressed interest in study participation. In the first round 226 patients participated (response rate=86.26%), and in the second round 214 patients participated (final response rate=81.7%). Thus, the final sample consisted of 214 patients (drop-out rates: from invitation to first round: n=36 (13.7%); from invitation to second round: n=48 (18.3%); from first to second round: n=12 (5.3%)). Mean age was 52 years (normally distributed), and two-thirds were women. Further information on participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics is displayed in table 1 and in online supplementary table S1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants of the first round (n=226)

| Characteristic | Frequency |

| Age (in years) | M=51.79 (SD=16.46) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 149 (65.9%) |

| Male | 76 (33.6%) |

| First language | |

| German | 219 (96.9%) |

| Other | 5 (2.2%) |

| Chronic disease group (multiple answers possible) | |

| Cancer | 36 (15.3%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 90 (39.8%) |

| Mental disorder | 117 (51.8%) |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 114 (50.4%) |

| Others* | 149 (67.4%) |

| Residence | |

| Hamburg | 59 (26.1%) |

| Baden-Wuerttemberg | 13 (5.8%) |

| North-Rhine Westphalia | 23 (10.2%) |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 3 (1.3%) |

| Saarland | 3 (1.3%) |

| Saxony | 13 (5.8%) |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 4 (1.8%) |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 10 (4.4%) |

| Thuringia | 1 (0.4%) |

| Bavaria | 22 (9.7%) |

| Berlin | 14 (6.2%) |

| Brandenburg | 11 (4.9%) |

| Bremen | 4 (1.8%) |

| Hesse | 14 (6.2%) |

| Mecklenburg-Western | 19 (8.4%) |

| Pomerania | 13 (5.8%) |

| Lower Saxony | |

| Health status† | M=2.49 (SD=0.77) |

*Additional to one of the four groups mentioned earlier. Other chronic diseases included, for example, diabetes (n=12), sleep apnea (n=5) and hypothyroidism (n=4). Please see online supplementary S1 for a comprehensive overview of other diseases.

†Health status was assessed with the item ‘How would you assess your health status in general?’ ranging from 1=excellent to 5=bad.

M, mean.

bmjopen-2019-031741supp002.pdf (79KB, pdf)

Results of round 1

In table 2, results from the first round of the ratings of relevance and degree of current implementation are shown. Regarding ratings of relevance, 13 out of 15 dimensions showed the maximum median of 9. The dimensions ‘patient as a unique person’, ‘clinician–patient relationship’, ‘clinician–patient communication’, ‘access to care’ and ‘physical support’ showed highest means (range from 8.46 to 8.31). Consensus was defined as the degree to which patients rated dimensions in agreement and was predefined as reached if it was higher than 50%. It means that consensus was reached when at least 50% of the patients rated dimensions to be very or not very relevant (tertile from 7 to 9 or 1 to 3, respectively). Every dimension showed consensus of >50% for tertile 7–9 (ie, majority of patients rated within the highest tertile). Regarding the current degree of implementation, 3 out of 15 dimensions showed a median of 6 (‘clinician–patient relationship’, ‘clinician–patient communication’ and ‘physical support’). All other dimensions showed a median of 5. The dimensions with the highest means were the same as those with the highest medians. Regarding consensus, every dimension had a rating of >50% for the tertile from 4 to 6. In general, every dimension of round 1 was rated as very relevant and as insufficiently implemented. Furthermore, patients were united in their rating because of the high consensus.

Table 2.

Results for the assessment of relevance and implementation from the first round

| Relevance | Implementation | |||

| Median | M (SD) | Median | M (SD) | |

| 1. PC characteristics of healthcare providers | 9 | 8.46 (0.90) | 5 | 5.30 (1.44) |

| 2. Trustful relationship | 9 | 8.41 (0.94) | 6 | 5.61 (1.72) |

| 3. Uniqueness of each patient | 9 | 8.31 (1.11) | 5 | 5.21 (1.74) |

| 4. Consideration of personal circumstances | 9 | 8.15 (1.23) | 5 | 4.77 (1.86) |

| 5. Appropriate communication | 9 | 8.31 (0.97) | 6 | 5.56 (1.74) |

| 6. Integration of additional healthcare elements | 8 | 7.34 (1.81) | 5 | 4.56 (1.99) |

| 7. Teamwork of healthcare providers | 9 | 8.29 (1.18) | 5 | 5.08 (1.90) |

| 8. Access to care | 9 | 8.31 (0.99) | 5 | 4.88 (2.08) |

| 9. Good planning of care | 9 | 8.30 (1.04) | 5 | 5.25 (1.92) |

| 10. Personally tailored information | 9 | 8.27 (1.12) | 5 | 5.10 (1.87) |

| 11. Collaboration as equal partners and involvement in decision-making | 9 | 8.25 (1.11) | 5 | 5.15 (2.04) |

| 12. Involvement of family and friends | 7 | 6.92 (2.16) | 5 | 4.91 (2.21) |

| 13. Empowerment of patients | 9 | 8.20 (1.13) | 5 | 5.23 (1.97) |

| 14. Support of physical well-being | 9 | 8.31 (0.98) | 6 | 5.58 (1.95) |

| 15. Support of mental well-being | 9 | 8.12 (1.35) | 5 | 4.83 (1.98) |

M, mean; PC, patient-centredness.

Sixty participants responded to the open-ended questions. Comments referred to additional aspects, including time issues within healthcare (eg, ‘Neither nurses, nor doctors have enough time for the patients’), financial aspects (‘without additional costs for people living in poverty’) and medication plans (‘discussing medication plans is too fast’ or ‘more information about side effects’). We revised descriptions after the first round according to the most frequent comments (third version). German descriptions of dimensions used in round 2, in which changes from the second to third version are highlighted, are listed in online supplementary appendix A1.

A few patients stated that patient safety could be improved by better coordination of medication plans. Furthermore, patient safety was already depicted as part of the dimension ‘physical support’ in the model.14 Due to comments, we revised the model to add ‘patient safety’ as a separate 16th dimension.

Results of round 2

In round 2, most ratings were very similar to the first round and medians did not change (see table 3). The added dimension of patient safety was also considered relevant but currently insufficiently implemented. The adaptations we made based on the feedback were rated as ‘better than before’ (all means over 7). This time, most relevant dimensions were ‘patient safety’, ‘teamwork and team building’, ‘access to care’, ‘patient information’ and ‘essential characteristics of clinicians’. ‘Clinician–patient communication’, ‘clinician–patient relationship’ and ‘physical support’ again reached the best ratings regarding implementation. Additionally, the newly added dimension ‘patient safety’ also reached equally high ratings.

Table 3.

Results for the assessment of adaptation, relevance and implementation of the second round

| Adaptation (round 1 to round 2) | Relevance | Implementation | |||||||

| Median | M | SD | Median | M | SD | Median | M | SD | |

| 1. PC characteristics of healthcare providers | – | – | – | 9 | 8.36 | 1.30 | 5 | 5.27 | 1.38 |

| 2. Trustful relationship | 8 | 7.64 | 1.59 | 9 | 8.18 | 1.34 | 6 | 5.47 | 1.44 |

| 3. Uniqueness of each patient | – | – | – | 9 | 8.30 | 1.24 | 5 | 5.17 | 1.50 |

| 4. Consideration of personal circumstances | 8 | 7.14 | 1.80 | 9 | 8.07 | 1.36 | 5 | 4.83 | 1.61 |

| 5. Appropriate communication | – | – | – | 9 | 8.33 | 1.12 | 6 | 5.62 | 1.54 |

| 6. Integration of additional healthcare elements | – | – | – | 8 | 7.46 | 1.67 | 5 | 4.61 | 1.81 |

| 7. Teamwork of healthcare providers | – | – | – | 9 | 8.45 | 1.04 | 5 | 5.08 | 1.75 |

| 8. Access to care | 8 | 7.79 | 1.59 | 9 | 8.38 | 1.09 | 5 | 4.81 | 1.83 |

| 9. Good planning of care | 8 | 7.28 | 1.82 | 9 | 8.18 | 1.28 | 5 | 5.07 | 1.73 |

| 10. Patient safety | – | – | – | 9 | 8.56 | 0.94 | 6 | 5.61 | 1.64 |

| 11. Personally tailored information | 8 | 7.86 | 1.43 | 9 | 8.37 | 1.02 | 5 | 5.03 | 1.82 |

| 12. Collaboration as equal partners and involvement in decision-making | – | – | – | 9 | 8.32 | 1.12 | 5 | 5.25 | 1.74 |

| 13. Involvement of family and friends | – | – | – | 7 | 6.85 | 2.01 | 5 | 4.92 | 1.91 |

| 14. Empowerment of patients | 8 | 7.59 | 1.41 | 9 | 8.15 | 1.23 | 5 | 5.21 | 1.77 |

| 15. Support of physical well-being | 8 | 7.40 | 1.74 | 9 | 8.18 | 1.26 | 6 | 5.55 | 1.71 |

| 16. Support of mental well-being | – | – | – | 9 | 8.25 | 1.33 | 5 | 4.87 | 1.85 |

M, mean; PC, patient-centredness.

Subgroup analyses

In every chronic disease group, distribution of patients participating via mail or online was similar (approximately 45:55 ratio, respectively). There was no major age difference between mail-based and online-based participation (mean age (mail): 54.83 years (SD=17.85); mean age (online): 49.35 years (SD=14.88)). Due to small sizes of subsamples (eg, only six patients indicated to have cancer), differences in ratings depending on chronic disease groups could not be analysed (ie, via analysis of variance). Neither multi-morbidity (at least two chronic disease groups indicated compared with only one), nor type of participation (mail vs online) did affect assessment of relevance and implementation by patients. That is, there were no differences between means bigger than 1. The differences of means above 1 were found within different age groups. The implementation of ‘access to care’ was rated lower by young patients in comparison with older patients (mean=4.37 for young vs mean=5.38 for older patients). Implementation of ‘patient information’ was also rated lower by young patients (mean=4.70 for young vs mean=5.71 for older patients).

Discussion

In our study, we have assessed relevance and current degree of implementation of different dimensions of PC in the German healthcare system from the patients’ perspective. The findings show that patients consider every dimension of PC very relevant but currently only mediocrely implemented. Furthermore, there were no evident factors influencing these results (eg, way of participation or multi-morbidity).

These results point out the relevance to ask patients when investigating PC. Comparing this assessment with the experts’ ratings of the same dimensions from the same model,14 differences between expert and patient ratings become evident. For example, experts did not rate each dimension as very relevant but patients did (eg, involvement of family and friends which was less relevant to experts but patients considered it relevant). This discrepancy is relevant for development of strategies to foster implementation of PC in Germany. If only the experts’ perspective is known, implementation efforts might not match patients’ needs. Consequently, a more PC care can only be achieved by taking into account patients’ perspectives.

Furthermore, the study reveals that while patients in Germany find PC extremely relevant, they do not find it well implemented in the German healthcare system. Thus, interventions to foster dimensions of PC on the micro level of care (eg, tools for clinicians and patients) could be developed and evaluated in future research. Furthermore, the results can guide the development of patient-reported experience measures. On the federal level, the results indicate that the German healthcare system could benefit from stronger health policy directives in regard to the delivery of PC care.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths of this study are the diverse sample from all over Germany and the possibility to anonymously generate a group consensus by performing a Delphi study. By doing so, ratings of each individual were not affected by dominant people in group discussions, and therefore are more likely to be unbiased. Furthermore, another strength of this study are the response rates indicating little drop out from round 1 to round 2. This could be ascribed to the internal motivation of participating patients willing to ameliorate healthcare services in Germany. Another explanation could be the financial compensation which they received only after having completed both rounds. However, although the notices were spread out widely, a participation bias (ie, only people with a higher interest in the topic would contact us) could have occurred by this method of recruitment. Furthermore, there was little variation within ratings of relevance of the dimensions of PC. This could indicate a lack of specification in the descriptions. Patients might have been unable to differentiate between subaspects of a single description. Thus, they might have rated the whole dimension as relevant even if they considered only some parts relevant enough to give a high score. Therefore, additional qualitative approaches (eg, by conducting semi-structured interviews) could help to enrich findings and further explain results by specifying relevant aspects instead of broad dimensions. Additionally, as our study focused on adding the patients’ perspective to the concept of PC care, we based our study on the integrative model of PC, which integrates over 400 definitions and models published between 1969 and 2012.12 We did not take into account further conceptual work published since (eg, the framework developed by Santana and colleagues30) which can be considered a limitation of this study. Furthermore, it is unclear if the results are generalisable to other countries. Since healthcare systems differ substantially between countries (eg, role of government, coverage, organisation of the delivery system, lengths of stay),20 31 patients’ perspective on PCC might also differ. Further research is needed to evaluate the patients’ perspective in other countries. Finally, another limitation of our study was the relatively low level of co-production with patients. As patients are recipients of PCC, this study could have benefitted from a higher level of patients’ participation.32

Future studies

Regarding future studies or specific recommendations, policy makers or other stakeholders, interested in fostering PC healthcare, should therefore not only focus on the ratings of relevance of experts but also consider the patients’ rating. In their opinion, every dimension of PC is relevant. These results should not be neglected. When implementing PC care, a wholesome perspective is therefore needed.

Conclusions

In summary, our study provides the patients’ perspective on PC by assessing relevance and current degree of implementation and therefore enriches current conceptualisations of PC. We showed that patients consider every dimension of PC relevant, but currently not well implemented. Furthermore, these results can be used for developing comprehensive questionnaires such as patient-reported experience measures regarding PC care. Regarding the status quo, especially in Germany, we therefore still need to make efforts since patients do not receive the PC healthcare they consider so relevant. Thus, these data can be used to deduce healthcare policies which tackle the insufficient implementation of PC from the patients’ perspective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our student assistant Tanja Kloster and our research intern Lara Dreyer for supporting us preparing the manuscript and transcribing the interviews.

Footnotes

Contributors: IS is the responsible principle investigator of the study. IS, PH and MH were involved in planning and preparation of the study. SZ and EC recruited participants and collected data. SZ analysed the data. SZ, IS, EC and PH interpreted the results. SZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IS, EC, PH and MH critically revised the manuscript for relevant intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for the work.

Funding: This study is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung) with the grant number 01GY1614.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: PH gave one scientific presentation on shared decision-making during a lunch symposium, for which she received compensation and travel compensation from GlaxoSmithKline GmbH (pharmaceutical company) in 2018.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was carried out according to the latest version of the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. Principles of good scientific practice were respected. The study had been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association Hamburg (study ID: PV5724) prior to the start of data collection. Study participation was voluntary and no foreseeable risks for participants resulted from the participation in this study. Participants were fully informed about the aims of the study, data collection and the use of collected data. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. Preserving principles of data sensitivity, data protection and confidentiality requirements were met.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Louw JM, Marcus TS, Hugo JFM. Patient- or person-centred practice in medicine? - A review of concepts. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2017;9:e1–7. 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. ‘Same same or different?’ A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:3–11. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO) WHO framework on integrated people-centred health services. Available: https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en/

- 4. Härter M, Dirmaier J, Scholl I, et al. The long way of implementing patient-centered care and shared decision making in Germany. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2017;123-124:46–51. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bundesrat Gesetzesbeschluss des deutschen Bundestages. Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Rechte von Patientinnen und Patienten (Patientenrechtegesetz), 2013. Available: http://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/pdfs/Gesetze/Gesetz_zur_Verbesserung_der_Rechte_von_Patientinnen_und_Patienten.pdf;jsessionid=1185B669A9CD4A090FDE13ABA75890D2.1_cid297?__blob=publicationFile [Accessed 04 Dec 2014].

- 6. Baumgart J. Ambivalentes Verhältnis. Dtsch Arztebl 2010;107:2554–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:351–79. 10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient–physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1516–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1087–110. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ouwens M, Hermens R, Hulscher M, et al. Development of indicators for patient-centred cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:121–30. 10.1007/s00520-009-0638-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart MA, Brown JB, Weston W, et al. Patient-centered medicine—transforming the clinical method. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness—a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Dulmen S. Patient-centredness. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51:195–6. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00039-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zill JM, Scholl I, Härter M, et al. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? - Results of a web-based expert Delphi survey. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141978 10.1371/journal.pone.0141978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bensing J, Rimondini M, Visser A. What patients want. Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:287–90. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty J, et al. Patient-centered care in chronic disease management: a thematic analysis of the literature in family medicine. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:170–6. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luxford K. What does the patient know about quality? Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:439–40. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maassen EF, Schrevel SJC, Dedding CWM, et al. Comparing patients’ perspectives of ‘good care’ in Dutch outpatient psychiatric services with academic perspectives of patient-centred care. J Ment Health 2017;26:84–94. 10.3109/09638237.2016.1167848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yasein NA, Shakhatreh FM, Shroukh WA, et al. A Comparison between patients’ and residents’ perceptions of patient centeredness and communication skills among physicians working at Jordan University Hospital. Open J Nurs 2017;07:698–706. 10.4236/ojn.2017.76052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Busse R, Riesberg A, World Health Organization . Health care systems in transition: Germany. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Osborn R. International profiles of health care systems, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Christalle E, Zeh S, Hahlweg P, et al. Assessment of patient centredness through patient-reported experience measures (ASPIRED): protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e025896–13. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e20476 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Rijssen LB, Gerritsen A, Henselmans I, et al. Core set of patient-reported outcomes in pancreatic cancer (COPRAC): an international Delphi study among patients and health care providers. Ann Surg 2019;270:158–64. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales Leichte Sprache - Ein Ratgeber, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Limesurvey GmbH An open source survey tool /LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany.

- 28. Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. IBM SPSS statistics for windows; 2015.

- 30. Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, et al. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect 2018;21:429–40. 10.1111/hex.12640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eurostat Hospital discharges and length of stay for inpatient and curative care, 2018: 1–16. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sacristán JA, Aguarón A, Avendaño-Solá C, et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:631–40. 10.2147/PPA.S104259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031741supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-031741supp002.pdf (79KB, pdf)