Abstract

Proposals to update the harmonised monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) from a public health perspective in Salmonella, Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from food‐producing animals and derived meat in the EU are presented in this report, accounting for recent trends in AMR, data collection needs and new scientific developments. Phenotypic monitoring of AMR in bacterial isolates, using microdilution methods for testing susceptibility and interpreting resistance using epidemiological cut‐off values is reinforced, including further characterisation of those isolates of E. coli and Salmonella showing resistance to extended‐spectrum cephalosporins and carbapenems, as well as the specific monitoring of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli. Combinations of bacterial species, food‐producing animals and meat, as well as antimicrobial panels have been reviewed and adapted, where deemed necessary. Considering differing sample sizes, numerical simulations have been performed to evaluate the related statistical power available for assessing occurrence and temporal trends in resistance, with a predetermined accuracy, to support the choice of harmonised sample size. Randomised sampling procedures, based on a generic proportionate stratified sampling process, have been reviewed and reinforced. Proposals to improve the harmonisation of monitoring of prevalence, genetic diversity and AMR in MRSA are presented. It is suggested to complement routine monitoring with specific cross‐sectional surveys on MRSA in pigs and on AMR in bacteria from seafood and the environment. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of isolates obtained from the specific monitoring of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli is strongly advocated to be implemented, on a voluntary basis, over the validity period of the next legislation, with possible mandatory implementation by the end of the period; the gene sequences encoding for ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemases being reported to EFSA. Harmonised protocols for WGS analysis/interpretation and external quality assurance programmes are planned to be provided by the EU‐Reference Laboratory on AMR.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance monitoring, Salmonella, Campylobacter, E. coli, MRSA, food‐producing animals, food

Summary

Provisions for the monitoring of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in zoonotic and indicator bacteria in food‐producing animals and derived meat are laid down in Directive 2003/99/EC. Also foreseen is the possibility of broadening the scope of the AMR monitoring to other zoonotic agents in so far as they may present a threat to public health. Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EC, implementing Directive 2003/99/EC, lays down detailed and harmonised rules for the monitoring and reporting of AMR, which are applicable from 2014 until the end of 2020. This legislative framework has been partially derived from technical specification documents issued by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2012, providing guidance on the harmonised monitoring of AMR in Salmonella, Campylobacter, indicator Escherichia coli and enterococci, as well as on the monitoring of prevalence, genetic diversity and AMR of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in several food‐producing animal categories and derived meat. In 2014, the EFSA also issued detailed functional specifications on randomised sampling for harmonised monitoring of AMR. The implementation of the legislation/these specifications by the European Union (EU) Member States (MSs) has led to greater harmonisation and better comparability of data on AMR; however, it seems inevitable that further enhancements and specific adaptations will be required on an ongoing basis to respond effectively to the constantly evolving threat of AMR.

The EFSA received a mandate from the European Commission to review and update the technical specifications issued in 2012 and 2014 and notably, specifically address in these updates the possible use of molecular typing methods, in the light of the latest scientific opinions on AMR, technological developments, recent trends in AMR and relevance for public health, as well as the audits assessing the implementation of the Decision performed by the European Commission in a number of MSs. This report includes proposals for implementing updated guidelines for further harmonised monitoring of AMR in food‐producing animals and food and for ensuring continuity in following up further trends in AMR (a factor which underpins the revision of existing guidelines).

The evidence from the European Union Summary Reports on AMR and the audit reports has shown that legislation has mostly been implemented by the MSs and has increasingly resulted in the production of comparable and reliable phenotypic AMR data over time. This is particularly true for the monitoring of trends and occurrence of resistance in indicator E. coli, which has become of particular relevance, as Salmonella prevalence has become increasingly low, thanks to the success of the control measures in place in the EU MSs.

In reviewing combinations of bacteria/animal/food as candidates for mandatory monitoring, it is proposed to reinforce the approach of prioritising potential consumers’ exposure by targeting zoonotic Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli, as well as indicator commensal E. coli from the major domestically produced animal populations. These populations include laying hens, broilers, turkeys, fattening pigs and bovine animals under 1 year of age, as well as meat derived from these sources. One of the major aims is the collection of AMR data that can be investigated in combination with data on exposure to antimicrobials, such as data on domestic consumption of antimicrobials in food‐producing animal populations. Although monitoring performed on a yearly basis would allow earlier detection of trends in AMR, in any direction, than monitoring at greater intervals, it is proposed to retain and reinforce the current monitoring performed on a rotating basis, targeting fattening pigs and bovine animals of less than one year, and poultry, separately, every second year. Thus, the potential benefits of an increased frequency of monitoring were reviewed considering competing priorities, as well as the need to get a balanced output from each of the most important sectors.

In addition to the routine monitoring performed on a biennial basis, the undertaking of complementary baseline cross‐sectional surveys in order to assess specifically the situation on certain AMR issues, such as MRSA, AMR in bacteria from sea food and AMR in bacteria from the environment, over the period of validity of the upcoming Commission Implementing Decision in 2021 onwards is suggested. It is envisaged that the detailed harmonised protocols of those specific baseline surveys would be designed at a later stage, considering the most recent data, once a clear agreement to carry out such studies had been reached.

Within the context of the implementation of the EU and MSs’ action plans against the threat of AMR, a further decrease in use of antimicrobials in food‐producing animals is expected to occur in conjunction with implementing complementary mitigation measures in the coming years, resulting in a decrease in the selective pressure on the emergence and/or occurrence of AMR. The approach and the results of the sample size analyses and calculation in the previous EFSA technical specifications were reviewed. The minimum target number of organisms of each bacterial species which should be examined is currently 170 from each type of domestic animal production type. The sample size should be adapted in the case of low Salmonella prevalence and very small production sectors. In order to ensure sufficient statistical power so that even slight decreases in AMR can be detected, it is also recommended that sample size is reviewed by each MS taking into account their own situation and objectives of reduction of AMR in the light of the simulations presented in this report, which also account for the assessment of the occurrence of resistance with sufficient accuracy. It is acknowledged that this approach may lead to an increase in the number of samples to be collected, and that this may require additional resource from the MSs. In designing a sampling scheme, therefore, special efforts have been made to, where possible, exploit samples already collected under existing AMR monitoring programmes, such as caecal samples gathered at the slaughterhouse.

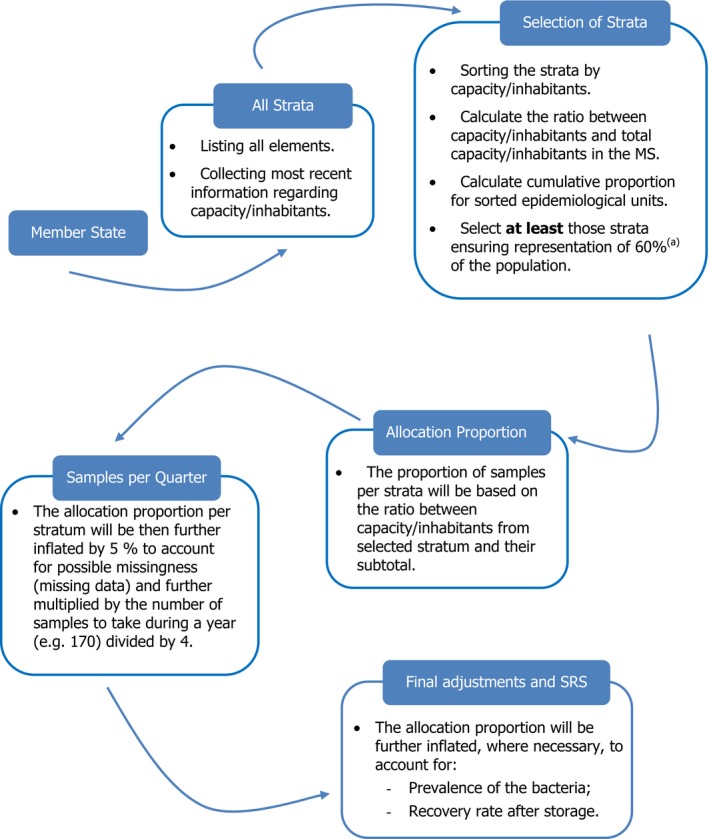

A key principle considered in relation to sampling design is to reinforce harmonised functional procedures for randomised sampling of animal and meat samples at different stages of the food chain, yielding representative and comparable data. Both collection strategies, a prospective and a retrospective sampling plan, of samples and isolates, respectively, are retained. The former involves collecting sufficient numbers of representative animal and chilled meat samples from which recovered isolates are tested for susceptibility; the latter involves selecting randomly Salmonella isolates from collections constituted within the framework of the national control programmes of Salmonella in poultry flocks. A generic proportionate stratified sampling process is proposed for the different sampling plans and numerical illustrations of proportional allocation are also recalled.

Stratified sampling of Salmonella isolates recovered from broiler, laying hen and fattening turkey primary production, and available in the collection of the laboratories involved in the Salmonella national control programmes, with proportional allocation to the size of the collection of isolates recovered from the production, is proposed. An alternative approach is to perform a simple random sampling within the sampling frame of flocks positive for Salmonella in those MS where a database records flocks tested positive for Salmonella. One Salmonella isolate per serovar and epidemiological unit should be retained for susceptibility testing. If more than 170 Salmonella isolates fitting the epidemiological criteria are available, 170 Salmonella isolates selected at random should be tested for antimicrobial susceptibility; if less than 170 Salmonella isolates are available, all available isolates should be tested for antimicrobial susceptibility (without any proportional allocation).

Stratified sampling of caecal content samples (single or pooled) in the slaughterhouses, accounting for at least 60% of the domestic production of the food‐producing animal populations monitored, with proportionate allocation to the slaughterhouse production, allows for the collection of representative isolates of Salmonella, Campylobacter, indicator E. coli and the assessment of the prevalence of ESBL‐/AmpC‐/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli from the populations of broilers, fattening turkeys, fattening pigs and bovine animals of less than 1 year of age, domestically produced. Definitions of ‘domestically produced’ animals are proposed for the sake of harmonisation.

Sampling of different chilled fresh meat categories is targeted at retail outlets serving the final consumer, with proportional allocation of the number of samples to the population of the geographical region (NUTS‐3 area) accounting for at least 80% of the national population, to test for the presence of ESBL‐/AmpC‐/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli.

The epidemiological units are flocks of poultry, slaughter batches of fattening pigs and bovine animals under 1 year, and lot of meat.

As regards the laboratory methodologies, it is confirmed that broth microdilution is the preferred method and that European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, http://www.eucast.org/) epidemiological cut‐off values should be used as interpretative criteria to define microbiological resistance. The concentration ranges to be used should ensure that both the epidemiological cut‐off value and the clinical breakpoint are included so that comparability of results with human data is made possible. As regards the harmonised set of antimicrobial substances to be used for phenotypic susceptibility testing, it is noted that the panels currently included in the legislation have been used across the MSs. The limited revisions and/or additions that have been proposed should enable to both account for recent trends in AMR and continue following up further temporal trends for the sake of continuity. Also, although in principle, the optimal concentration range should be tested for each substance, for some substances this has been reduced to a minimum range so that wells can be freed on the harmonised plate to allow for inclusion of novel substances.

In particular, it is proposed to complement the current (first) harmonised panel of antimicrobials for Salmonella and E. coli with amikacin to improve the detection of 16S rRNA methyltransferase enzymes that confer resistance to all aminoglycosides except streptomycin. These methyltransferases have been increasingly found in association with carbapenemases, AmpC or ESBL enzymes and fluoroquinolone resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, especially outside Europe. In order to accommodate the additional substance, it is suggested to slightly modify the harmonised panel by reducing some of the dilution ranges, in particular those for ampicillin, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, gentamicin, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole and chloramphenicol in the upper end of the scales, as the susceptible end is considered more important to define.

No changes were deemed necessary to the recommended antimicrobial panel currently used to test further those Salmonella and E. coli isolates that exhibit resistance to a third‐generation cephalosporins and/or carbapenems so as to perform the monitoring of extended‐spectrum β‐lactamase‐/AmpC β‐lactamase‐/carbapenemase‐producing bacteria, whether deriving from either the routine monitoring of AMR in Salmonella and indicator E. coli or the specific monitoring of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase producers.

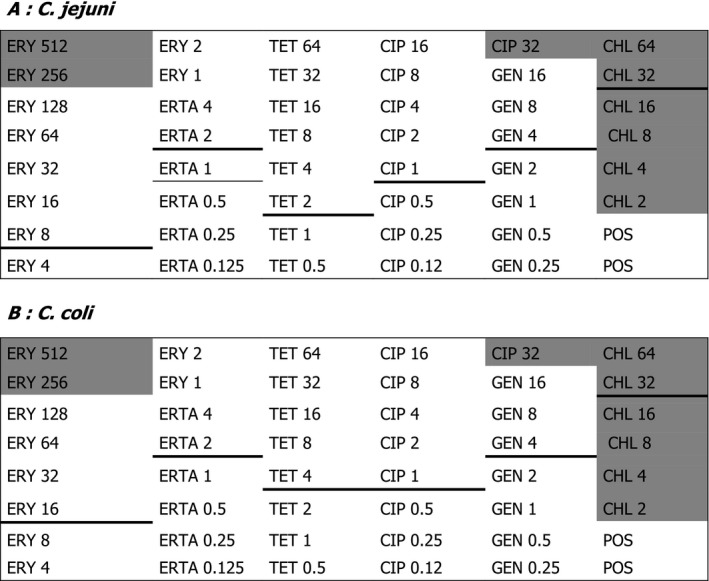

As regards Campylobacter, it is proposed to slightly alter the harmonised panel with the removal of nalidixic acid, streptomycin and the lowest concentration of gentamicin so as to allow for the inclusion of additional higher concentrations of erythromycin (for better detection of isolates with high‐level erythromycin resistance which may be presumptively considered to harbour the erm(B) gene) as well as higher concentrations of ciprofloxacin and a phenicol molecule, thereby allowing for the presumptive deduction of genotypes with altered sequence of the CmeABC efflux pump and its regulating region. It is also proposed to include a carbapenem antimicrobial. In addition, in order to improve the comparability of Campylobacter prevalence and AMR data between MSs, it is highly desirable that the EU monitoring be based on harmonised methods for both isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. A harmonised protocol based on the European standard EN ISO 10272‐1, detection procedure C, should be provided for the purpose. It is proposed that the EURL‐Campylobacter perform in 2019–2020 the requested pilots to finalise the setting up of the harmonised protocol. A better knowledge of the prevalence of Campylobacter spp., C. jejuni and C. coli in animal production and food of animal origin in the different MSs and of the prevalence of resistance in these two species will help understanding the epidemiology and especially the potential sources of human C. jejuni and C. coli infections, and the differences in proportions of C. jejuni and C. coli in human cases between European countries. It is also proposed, based on recent source attribution studies, to target cattle in the Campylobacter AMR monitoring. This is also likely to aid development of improved measures for control of this zoonotic agent.

Considering the advantages inherent in the whole genome sequencing (WGS) technology but also its current limitations, as well as the expected evolution of the present situation, it is proposed to follow a gradual, phased approach to integration of WGS within the harmonised AMR monitoring. The integration process could be initiated by complementing the harmonised phenotypic monitoring with WGS on a voluntary basis in the early phase of the period 2021–2026 and at the end of the period envisage the replacement of the standard routine phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing with the systematic use of WGS. The period 2021–2026 should therefore be seen as a transitory period for the implementation of WGS, expected to be a reasonable transition period for the MSs to gain experience and acquire WGS technology.

The proposed flexible approach corresponds to allowing MSs/National Reference Laboratories (NRLs) to use WGS on a voluntary basis for detection of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli replacing panels 1 and 2 of the phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing method in the monitoring for these organisms. The voluntary replacement of the phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing method for detection of ESBL‐/AmpC/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli is proposed to begin in 2021.

The switch to WGS for commensal E. coli, Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp. and enterococci should optimally take place in a co‐ordinated way for all MSs at one predetermined point in time and when the necessary developments are in place to allow comparison of the historical (phenotypic) and genotypic results. The phased introduction of WGS for the specific monitoring of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase‐producing E. coli would mean that in the course of the upcoming Commission Implementing Decision's validity period, for example by 2025, all MSs should have WGS in place. A road map should be set up to establish methods for comparison of outputs, whether simple (e.g. occurrence of resistance) or complex (e.g. complete susceptibility), from phenotypic data (including historical data) and WGS data that will need to have been developed and implemented at the point of the switch from phenotypic to genotypic monitoring, as well as harmonised procedures for handling and reporting WGS data.

To achieve the goal of implementing WGS across the food and veterinary sectors of the NRLs during the upcoming Commission Implementing Decision's validity period, as well as the generalised use of WGS in the specific monitoring by the end of the period. The performance by the MSs of the WGS part of the ‘Confirmatory Testing’ should become mandatory by the end of the period. Again WGS can be used on a voluntary basis at the start of the period, with the support of the EURL AR.

To implement the use of WGS, it is pivotal for reasons of comparability that all data are processed using the same/harmonised approach. It is proposed that the EURL‐AR continue the effort to provide and organise training in DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing. Moreover, the EURL‐AR should recommend harmonised standard operating procedure/protocols/guidelines including quality criteria and external quality assessment procedures, overseen by the EURL‐AR, should be developed in 2019–2020. The aim should be to use the same version and curated reference database based on benchmarking efforts, and similar parameters/tools for all the steps of the analysis (trimming, quality, assembly, AMR characterisation). It is also proposed that, by the implementation of WGS, the EURL‐AR develops and establishes a genomic‐based proficiency test to assess the quality of the genomes produced by the NRLs and the reliability of the detection of AMR determinants/genes. MSs will be encouraged to submit voluntarily their sequences, if not already publicly available, to the planned Joint ECDC‐EFSA database for WGS data in order to perform joint analysis across sectors (human, animal and food).

It is proposed to reinforce the monitoring of MRSA in food‐producing animals and food. In particular, the concept of a baseline survey on MRSA in pigs to be performed either on the farm or at the slaughterhouse over the period of validity of the next Decision is put forward. The harmonised panel for testing the antimicrobial susceptibility of MRSA has been reviewed. Some of the antimicrobials included in the panel are critically important in human medicine for the treatment of MRSA and other Gram‐positive bacterial infections in humans, including vancomycin and linezolid. Resistance to vancomycin or linezolid should lead to investigation of the mechanism of resistance, including WGS, to determine whether any of those genes known to confer resistance are present. A number of alterations to the concentration ranges are proposed for gentamicin, trimethoprim, kanamycin, fusidic acid, penicillin, vancomycin and rifampicin; the antimicrobials included in the panel remain unchanged. Characterisation of MRSA isolates is also recommended by genotypic analysis (WGS) to determine strains and lineages as well as to investigate the presence of important virulence and host‐adaptation factors and those specific genetic markers (e.g. phages) associated with certain animal hosts.

It is also suggested that routine monitoring is complemented with specific baseline (cross‐sectional) studies (in addition to that on MRSA in pigs) on AMR in bacteria from seafood and the environment, to be carried out over the validity period of the next legislation. The intention is to propose detailed protocols for those baseline studies later on, once a clear agreement on the conduct of those baseline studies has been reached.

As regards the best format for the reporting of the data, the recommendations are the same as those from the technical specifications relating to the collection and reporting of data at isolate‐based level which have been previously published.

The genes encoding ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemases detected by WGS should be reported to EFSA. Protocols and interpretation of WGS analysis need to be harmonised and supported by external quality assurance programmes.

In addition, it is emphasised that if complementary AMR monitoring in additional animal populations and food categories is carried out, specific representative sampling plans should be devised and results should be reported separately.

Finally, it is proposed that the technical specifications be re‐assessed and updated regularly in the light of the results of the first monitoring campaigns, the most recent literature and the constantly evolving situation.

1. Introduction

The Commission adopted in June 2017 a new European One Health action plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)1 which provides a framework for continued, more extensive action to reduce the emergence and spread of AMR and to increase the development and availability of new effective antimicrobials inside and outside the EU. Under this new One Health action plan, in order to strengthen One Health surveillance and reporting of AMR and antimicrobial use, the Commission is committed to review EU implementing legislation on monitoring AMR in zoonotic and commensal bacteria in farm animals and food, to take into account new scientific developments and data collection needs.

In accordance with Article 31 of regulation (EC) No 178/2002, the Commission has requested scientific and technical assistance to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in view of reviewing Decision 2013/652/EU. The European Union reference laboratory for antimicrobial resistance (EURL‐AR) in Copenhagen and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have been consulted on this matter as appropriate.

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the EC

1.1.1. Background

Combating AMR is a priority for the European Commission (EC). Surveillance of AMR and antimicrobial consumption is essential to have comprehensive and reliable information on the development and spread of drug‐resistant bacteria, to measure the impact of measures taken to reduce AMR and to monitor progress. Such data provide insights to inform decision‐making and facilitate the development of appropriate strategies and actions to manage AMR at European, national and regional levels.

As part of the new European One Health action plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)2 adopted in June 2017, the Commission is committed to review EU implementing legislation on the harmonised monitoring of AMR in zoonotic and commensal bacteria in food‐producing animals and food, to take into account new scientific developments, including the recent evolutions of epidemiological situations in the Member States, and data collection needs.

Under Directive 2003/99/EC3 on the monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents, Member States must provide comparable monitoring data on the occurrence of AMR in zoonotic agents and, in so far as they present a threat to public health, other agents.

Between 2008 and 2011 EFSA adopted several scientific opinions4, a joint scientific opinion together with the ECDC, the EMA and the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR)5 and a technical report6 which concluded that in view of the increasing public health concern regarding AMR, the use of harmonised methods and epidemiological cut‐off values is necessary to ensure the comparability of data over time at Member State level, and also to facilitate the comparison of the occurrence of AMR between Member States.

In 2012 the EFSA published two additional scientific reports on the technical specifications on the harmonised monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella, Campylobacter and indicator commensal Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. bacteria transmitted through food7 and the technical specifications on the harmonised monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food‐producing animals and food.8

Having regard to the findings of these scientific reports, the European Commission adopted in 2013 Decision 2013/652/EU9 on the monitoring and reporting on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and commensal bacteria as part of the 2011–2016 EC action plan against the rising threats from AMR.10 This Decision, which applies from 2014 to 2020, lays down detailed rules for the harmonised monitoring and reporting of AMR to be carried out by Member States in accordance with Article 7(3) and 9(1) of Directive 2003/99/EC and Annex II (B) and Annex IV thereto.

Since its publication, the EFSA issued a scientific report on detailed functional specifications on randomised sampling for harmonised monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and commensal bacteria.11 The European Commission has also conducted a series of audits on the implementation of Decision 2013/652/EU. An interim overview report on these series was published in July 2017.12 It highlights the main key implementation barriers faced by Member States, in particular achieving the minimum required number of samples/isolates:

In the case of Salmonella, isolates are obtained either from the Salmonella National Control Programs (SNCPs) or from the application of Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. In case of low prevalence all Salmonella isolates available shall be tested. This includes those isolates obtained by food business operators (FBOs) but competent authorities rarely manage to avail these isolates.

In the case of Campylobacter jejuni, in some Member States two phenomena have been observed since Decision 2013/652/EU entered into force, namely, the low prevalence of C. jejuni and the higher prevalence of Campylobacter coli in certain poultry sectors.

In certain circumstances, and due to the structural particularities of some production sectors, the definition of the epidemiological unit, in particular for fattening pigs and bovines under 1 year of age, has also been a limiting factor to collect isolates in certain Member States.

Due to a combination of these factors Member States with a low production, in particular small Member States, have communicated problems to achieve the minimum number of isolates.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference as provided by the EC

In accordance with Article 31 of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, the Commission therefore requests scientific and technical assistance from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in view of updating:

the 2012 EFSA technical specifications on the harmonised monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella, Campylobacter and indicator commensal Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. bacteria transmitted through food. In doing so, the EFSA should also provide advice on how to scientifically address the problems identified during the audits in Member States as specified in the background.

the 2012 EFSA technical specifications on the harmonised monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food‐producing animals and food.

the 2014 EFSA technical specifications on randomised sampling for harmonised monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and commensal bacteria.

The EFSA should address in these updates the possible use of molecular typing methods (e.g. Whole Genome Sequencing) to complement and/or replace the phenotypic methods currently used to assess antimicrobial resistance, described in Decision 2013/652/EU, taking into account the necessity to ensure the comparability of the results with the non‐molecular techniques and the possibility to integrate the molecular data with past and future phenotypical data. If molecular techniques are proposed as alternative techniques to the phenotypic methods, EFSA should provide technical specifications on how to ensure comparability of techniques.

The scientific and technical assistance should take into account recent scientific opinions on AMR, technological developments, recent trends in AMR and relevance for public health. It should consider the comparable AMR monitoring data reported by the Member States to EFSA in the period following adoption of Decision 2013/652/EU, as well as the outcomes of audits assessing implementation of the Decision which provide an overview of the main key implementation barriers faced by Member States. It should also take into account the Joint scientific opinion on a list of outcome indicators as regards surveillance of antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption in humans and food‐producing animals,13 as it establishes a set of indicators for Member States to assess their progress in reducing the consumption of antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance in both humans and food‐producing animals. Finally, it should also ensure that proposed developments, where possible, enhance the Joint Interagency Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance Analysis (JIACRA) performed by EFSA, EMA and ECDC.

2. Brief outline of the current harmonised monitoring system of AMR

Directive 2003/99/EC14 on the monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents set out generic requirements for the monitoring and reporting of AMR in isolates of zoonotic Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp., as well as in selected other bacteria – in so far as they present a threat to public health – from food‐producing animals and food in the EU Member States (MSs). Within the framework of AMR monitoring in food‐producing animals and food, the occurrence of AMR is typically defined as the proportion of bacterial isolates tested for a given antimicrobial and found to present any degree of acquired reduced phenotypic susceptibility when compared to the fully susceptible wild‐type population, i.e. to display ‘microbiological resistance’. Epidemiological cut‐off values (ECOFFs)15 are used as interpretative criteria of microbiological resistance.16

2.1. Description of the data collected by the system

The AMR monitoring in food‐producing animals and food was revised by Commission Decision 2013/652/EU implementing Directive 2003/99/EC, which set out monitoring priorities from a public health perspective and described those combinations of bacterial species, antimicrobial substances, food‐producing animal populations and food products which should be monitored from 2014 onwards, including the frequency with which monitoring should be performed.

2.1.1. Bacterial species, food‐producing animals and food products

Since the implementation of the Commission Decision, the monitoring of AMR in zoonotic Salmonella spp. and C. jejuni, as well as in indicator E. coli from the major food‐producing animal populations domestically produced has become mandatory. Indicator E. coli and Campylobacter spp. isolates derive from active monitoring programmes, based on representative random sampling of carcasses of healthy animals sampled at the slaughterhouse to collect caecal samples. For Salmonella spp. from broilers, laying hens and fattening turkeys, isolates are included which originate from Salmonella national control plans, as well as isolates from carcases of broilers and fattening turkeys, sampled as part of process hygiene criteria. For Salmonella spp. from fattening pigs and bovine animals under 1 year of age, isolates are included originating from carcases of these animals, sampled as part of process hygiene criteria. The target number of organisms of each bacterial species which should be examined is 170 from each type of domestic animal production type (this is reduced to 85 organisms from poultry and pigs, if production is less than 100,000 tonnes per annum). From 2014 onwards, poultry/poultry meat will be monitored in 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2020, and pigs and bovines under 1 year, pork and beef in 2015, 2017 and 2019. Within each MS, the various types of livestock and meat from those livestock should be monitored when production exceeds 10,000 tonnes slaughtered per year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Organisms included in AMR monitoring in 2014 and subsequent years, as set out in Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU

| Animal populations/ Meat | Salmonella spp. | C. jejuni | C. coli | Indicator/ ESBL‐producing E. coli | CP‐producing E. coli | E. faecalis/ E. faecium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broilers | M: NCP, PHC | M: CSS | V | M: CSS | V | V |

| Laying hens | M: NCP | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fattening turkeys | M: NCP, PHC | M: CSS | V | M: CSS | V | V |

| Bovines, < 1 year old | M: PHC | – | – | M: CSS | V | V |

| Fattening pigs | M: PHC | – | – | M: CSS | V | V |

| Broiler meat | – | – | – | M: R | V | – |

| Pig meat | – | – | – | M: R | V | – |

| Bovine meat | – | – | – | M: R | V | – |

CP: carbapenemase; CSS: caecal samples from healthy animals at slaughter; M: mandatory monitoring; NCP: Salmonella national control plans; PHC: surveillance of process hygiene criteria; R: at retail; V: voluntary monitoring.

2.1.2. Panels of antimicrobial substances

The antimicrobial substances included in the monitoring from 2014 onwards are shown in Table 2. The panel of antimicrobials tested includes those of particular public health relevance as well as those of epidemiological relevance; ECOFFs were used as the interpretative criteria of resistance (Kahlmeter et al., 2003). The harmonised panel of antimicrobials used, particularly for Salmonella spp. and E. coli, was broadened with the inclusion of substances, such as colistin and ceftazidime, that are either important for human health or provide clearer insight into the probable mechanisms of resistance to extended‐spectrum cephalosporins.

Table 2.

Harmonised set of antimicrobial substances used for the monitoring of resistance in zoonotic Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp., and indicator Escherichia coli and enterococci isolates from food‐producing animals and food over the period 2014–2020a

| Substances | Salmonella | C. coli/C. jejuni | Indicator E. coli | Enterococci |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | ● | ● | ● | |

| Azithromycin | ● | ● | ||

| Cefepime | x | x | ||

| Cefotaxime | ● | ● | ||

| Cefotaxime + clavulanic acid | x | x | ||

| Ceftazidime | ● | ● | ||

| Ceftazidime + clavulanic acid | x | x | ||

| Chloramphenicol | ● | ● | ● | |

| Ciprofloxacin | ● | ● | ● | |

| Colistin | ● | ● | ||

| Daptomycin | ● | |||

| Ertapenem | x | x | ||

| Erythromycin | ● | ● | ||

| Gentamicin | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Imipenem | x | x | ||

| Linezolid | ● | |||

| Meropenem | ● | ● | ||

| Nalidixic acid | ● | ● | ● | |

| Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | ● | |||

| Streptomycin | ● | ● | ||

| Sulfonamides | ● | ● | ||

| Teicoplanin | ● | |||

| Temocillin | x | x | ||

| Tetracycline | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Tigecycline | ● | ● | ● | |

| Trimethoprim | ● | ● | ||

| Vancomycin | ● |

●: all isolates; x: only for isolates resistant to cefotaxime, ceftazidime and/or meropenem.

Commission Decision 2013/652/EU17.

2.1.3. Specific monitoring of ESBL‐/AmpC‐ and/or carbapenemase‐producing E. coli

Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU stipulates caecal samples from broilers, fattening turkeys, fattening pigs and bovines under 1 year of age, as well as from broiler meat, pork and beef collected at retail should be examined for E. coli using selective media incorporating the third‐generation cephalosporin cefotaxime. This medium is selective for E. coli resistant to third‐generation cephalosporins and is expected to allow the growth of extended‐spectrum β‐lactamases (ESBL), AmpC β‐lactamases (AmpC) or carbapenemase enzyme producers, which are resistant to cefotaxime at the microbiological cut‐off. Three hundred caecal samples should be examined from each type of livestock and meat.

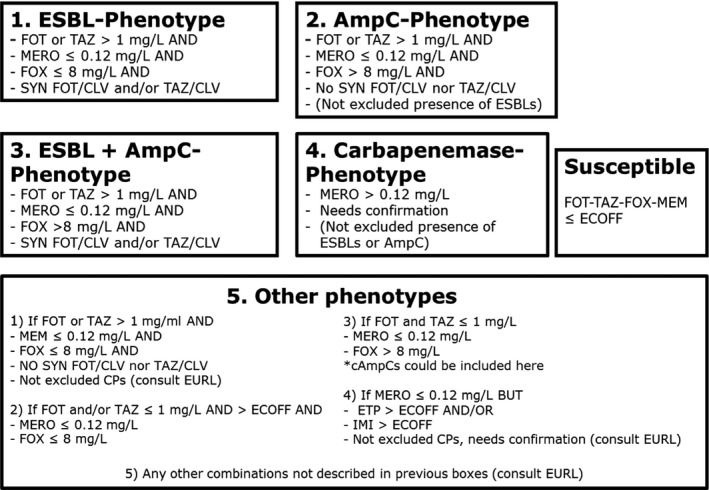

In practice, all presumptive ESBL‐ or AmpC‐ or carbapenemase‐producing E. coli isolates identified through the selective plating, as well as all those randomly selected isolates of Salmonella spp. and E. coli, recovered from non‐selective media, that are resistant to cefotaxime or ceftazidime or meropenem, are further tested with a second panel of antimicrobial substances (Table 2). This second panel of antimicrobials includes cefotaxime and ceftazidime with and without clavulanic acid (to investigate whether synergy is observed with clavulanate), as well as the antimicrobials cefoxitin, cefepime, temocillin, ertapenem, imipenem and meropenem. The second panel of antimicrobials is designed to enable phenotypic characterisation of ESBL‐, AmpC‐ and carbapenemase producers.

Moreover, Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU also foresees the monitoring of carbapenemase‐producing microorganisms using selective medium with a carbapenem, on a voluntary basis. A number of the MSs has performed this specific monitoring focusing on the detection of carbapenemase‐producing E. coli.

2.2. Strength of the system

The monitoring of AMR in food‐producing animals under Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU covers the main food‐producing animal species and where appropriate, includes different production sectors (for example, broilers and laying hens). Randomised, representative sampling is no longer stratified at the level of the different animal species (e.g. Gallus gallus, cattle, pigs) but rather is performed at the level of the major food‐producing animal production categories, such as broilers, laying hens, fattening pigs, fattening turkeys and bovines under 1 year of age.

The effects of consumption of antimicrobials in a given country and animal species, on the occurrence of resistance, can be studied more easily in indicator organisms than in food‐borne pathogens, such as Salmonella spp., because all food‐producing animals generally carry these indicator bacteria. Monitoring resistance in indicator commensal E. coli has become mandatory. Sampling for the collection of indicator bacteria should be representative of the domestically produced population studied, in accordance with the provisions of the Decision and the corresponding detailed technical specifications issued by EFSA (2012b, 2014). The isolates subjected to susceptibility testing have typically been derived from active monitoring programmes in healthy animals, ensuring representativeness of resistance data, especially in the case of indicator bacteria and Campylobacter spp. AMR data from susceptibility testing of Salmonella spp. have remained more dependent on the prevalence and the serovar distribution of the bacteria in the different animal populations.

Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU also ensures that all reporting countries submit data for a common core set of antimicrobials and bacteria set out in Table 2; data for these combinations should therefore be comprehensive. The collection and reporting of data are now performed at the isolate level, which enables in‐depth analyses to be conducted, in particular on the occurrence of multidrug resistance. The analysis of the results at individual isolate level also allows investigation of possible associations between the occurrence of isolates which are fully susceptible to the panel of antimicrobials tested and the consumption of antimicrobials.

An external quality assurance system, based on regular training and yearly proficiency tests, is included in the AMR monitoring programmes. This will detect potential differences between the laboratories performing susceptibility tests relating to methods or interpretative criteria and is coordinated by the National Reference Laboratories on AMR (NRL‐AR) within each reporting country and the EU Reference Laboratory on Antimicrobial Resistance (EURL‐AR).

2.3. Impediments of the system

The European Commission has carried out audits in, up to now, 14 MSs to check the actual implementation of the AMR monitoring programmes laid down by the current EU legislation. The system ensures that there is harmonisation of resistance monitoring in food‐producing animals and comparability of the AMR data recorded in the respective EU MSs.

MSs came across some challenges when implementing Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU in some aspects of the monitoring including planning and sampling, sample processing, laboratory testing and reporting to EFSA. It is worth recalling that those issues have been improved since the audits were conducted. Those challenges were taken into account when drafting the current technical report.

3. Recent developments and the evolution of the AMR situation

The introduction of Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU planning the implementation of revised panels of antimicrobials to be tested and specific monitoring has enabled to enlarge the scope of the AMR monitoring, and to enhance the reliability of the results. Nevertheless, the continually evolving threat from emerging resistance underlines the need to review the data collected, interpret the findings and assess trends in a constant manner, taking also into account recent developments in the methodology. A number of AMR issues have notably emerged since 2013, as summarised below and detailed further in Appendix A. Similarly, the epidemiological situation regarding Salmonella and Campylobacter has evolved over the last years and the revision of the harmonised monitoring of AMR should also account for such evolution. Alert points (e.g. emerging resistances, mechanisms, clones, etc.) might be defined triggering further investigation of individual isolates by molecular methods.

3.1. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica

Over the last decade, prevalence in targeted serovars of Salmonella in poultry has substantially decreased in most of the MSs. In certain MSs, the decrease may have exacerbated further the lack of a sufficient number of Salmonella isolates from poultry (i.e. broilers, laying hens, fattening turkeys) to be tested for AMR. As AMR in Salmonella continues to develop and new resistance issues have emerged in the population, continuous monitoring of AMR in Salmonella is advisable, although the limited number of isolates does not allow a full statistical trend analysis of the level of resistance. In contrast, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) in Salmonella should predominantly seek to detect and follow new emerging issues including sporadic occurrence of clones, such as multi‐drug resistant (MDR) S. Kentucky with a high resistance to fluoroquinolones and S. Infantis isolates exhibiting combined resistance to highest priority critically important antimicrobials (HPCIAs), such as extended‐spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and colistin (Appendix A). To this end, Salmonella obtained from slaughter animals have proved to be of major importance for the assessment of strains entering the food chain.

3.2. Campylobacter spp.

The high level of harmonisation of the method used for susceptibility testing, whether considering the sets of antimicrobials and dilution ranges to be tested, as well as the interpretative criteria of resistance (EUCAST ECOFFs) and the representative sampling design, enables comparison between levels of resistance and resistance profiles observed in bacteria among the MSs. External quality assurance for susceptibility testing is also provided to the NRLs by the EURL‐AR. Still, in the context of the rather recent introduction of the European standard EN ISO 10272‐1, slight differences between the Campylobacter isolation methods used in the MSs may occur and affect the recovery of Campylobacter spp. from samples, the proportions of C. jejuni or C. coli obtained and even the diversity of the isolates recovered, including the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles.

3.3. Indicator commensal E. coli

Under the current version of the implementing legislation, monitoring of AMR in indicator commensal E. coli is the data backbone of the EU‐wide monitoring. This is well justified as commensal E. coli have been shown to mirror exposure of population to antimicrobial selection pressure. Its prevalence in the intestines of production animals is usually > 90%, and target numbers of 170 (or 85) isolates were easily achieved. Therefore, this bacterial population can provide continuous evidence on trends, including possible reduction of AMR when antimicrobial consumption (AMC) has decreased over the last years, as observed in certain MSs.

3.4. Enterococci

In the Commission Implementing Decision of 12 November 2013 (2013/652/EU) on the monitoring and reporting of AMR in zoonotic and commensal bacteria, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis have been included since 2014 in the panel of bacterial species under survey on a voluntary basis. Annually, only a limited number of MSs submit AMR data to EFSA relating to E. faecium and E. faecalis. Furthermore, the AMR data submitted are sparse, sporadic and not well geographically represented, thus, the data is difficult to act and conclude upon. The current data available show, however, also that the AMR trend curve seems quite consistent with minor changes over years (DANMAP 2017). In addition, the level of AMR in enterococci is less predictive of the level of AMR in other Gram‐positive bacteria relevant for public health like staphylococci, where clonal spread of particular strains can be significant. For antimicrobials, whose spectrum of activity mainly includes Gram‐positive organisms (e.g. the macrolides), then mandatory monitoring of the susceptibility of E. faecalis and E. faecium at 4 year rotational basis, will allow investigation of associations between AMC and AMR to be undertaken. The enterococci fulfil a useful and unique function among the organisms which are monitored by representing a common or frequent Gram‐positive indicator organism which is not subject to the pressures from targeted control measures in the way that Campylobacter might be (a Gram‐negative zoonotic organism, though susceptible to macrolides). Monitoring AMR in enterococci as indicator bacteria representing Gram‐positive organisms will complement the data from E. coli is for Gram‐negative bacteria (Enterobacteriaceae) though data might be collected on a less frequent basis, reflecting the lower priority.

3.5. Specific monitorings of ESBL‐/AmpC‐ and/or carbapenemase‐ producing E. coli

Selective isolation of ESBL/AmpC and/or carbapenemase‐producing E. coli has demonstrated that it provides interesting complementary information to the monitoring of indicator commensal E. coli. The prevalence of ESBL/AmpC‐producing E. coli would be largely underestimated if monitored only by the testing of random isolates of indicator E. coli alone. Harmonised methods for the detection of these bacteria have proven to be robust and regular PT trials performed by the EURL‐AR have shown that the NRL‐ARs are capable of detecting this kind of bacteria with sufficient accuracy. The wealth of identified strains of ESBL/AmpC‐producing E. coli have supported further analyses in research projects that helped understand potential spill over from animal populations and food to humans, especially to exposed people working in animal husbandry (Dorado‐Garcıa et al., 2018). Moreover, within this monitoring, a few strains of E. coli co‐producing carbapenemases have been also identified (EFSA and ECDC, 2017a, 2018a, 2019). The voluntary detection of carbapenemase‐producing microorganism from food‐producing animals and/or foods using specific selection with carbapenems, has also allowed the detection of a few isolates belonging to different Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli and Enterobacter spp.). The upcoming results of the ongoing IMPART research project‐topic 218 relating to selective isolation and detection of carbapenemase‐producing Enterobacteriaceae will be taken into account by the EURL‐AR while reviewing the current harmonised method recommended.

3.6. MRSA

Monitoring of MRSA prevalence in animals and food is currently performed on a voluntary basis by a number of MSs, many of whom report results to EFSA for inclusion in the yearly EU Summary Report on AMR. Some MSs also perform molecular typing and susceptibility testing of MRSA isolates, again on a voluntary basis (EFSA, 2012b). The EURL‐AR has published an updated protocol for the isolation of MRSA from food‐producing animals and the farm environment (http://www.eurl.eu).

A range of types of MRSA have been detected in animals (including the farm environment) and food, including healthcare‐associated MRSA, community‐associated MRSA, livestock‐associated MRSA and mecC MRSA, providing a strong rationale for further characterisation and typing of MRSA isolates from animal sources. Most isolates from food‐producing animals are livestock‐associated MRSA.

Those MSs performing AST and providing the results to EFSA have generally used a broth microdilution susceptibility testing method and have also tested very similar or identical panels of antimicrobials, as proposed by EFSA in 2012 (EFSA, 2012b).

The EURL‐AR organises external quality assurance assays for susceptibility testing of MRSA. Since monitoring of MRSA is carried out on a voluntary basis, there has been some minor variation in some of the procedures adopted by the MSs; sampling programmes in particular are subject to national variation in accordance with national priorities.

3.7. Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae is often multidrug resistant and appears to develop resistance easily (Wyres and Holt, 2018). It occurs in the environment, for example in surface waters, and on the mucous membranes and in the intestinal contents of humans and animals (Podschun and Ullman, 1998). It is therefore of potential interest as an AMR indicator and has high Public Health relevance since MDR clones may cause clinical infections and nosocomial outbreaks. Nevertheless, K. pneumoniae prevalence in samples is variable, and very high number of samples might need to be collected to obtain enough isolates. In the best case, K. pneumoniae could add as extra species for AMR monitoring of a (potential) pathogenic bacteria with an unknown zoonotic potential (if any). It is believed that, ideally, the prevalence/variability of prevalence of K. pneumoniae in food‐producing animals could be monitored. Despite this, as this bacterial species might not offer more as bacterial indicator of AMR than indicator E. coli does already, adding K. pneumoniae will not really improve the harmonised monitoring system of healthy animals at slaughter and may only provide fragmented information which may prove to be hard to interpret. Instead, at this stage, the monitoring of K. pneumoniae should be preferentially considered as part of a targeted monitoring of AMR in bacterial animal pathogens.

3.8. Epidemiological context

Within the context of the implementation of the EU and MSs’ action plans against the threat of AMR, a further decrease in use of antimicrobials in food‐producing animals is expected to occur in conjunction with implementing complementary mitigation measures in the coming years, resulting in a decrease in the selective pressure on the emergence and/or occurrence of AMR. Sampling design, and in particular sample size, should be therefore reviewed accounting for this expected epidemiological context in order to ensure that sufficient statistical power is available so that even slight decreases in AMR can be detected.

4. Views and feedback from NRL‐AR and EFSA Networks

To address further certain specific aspects of the AMR monitoring in the EU MSs/reporting countries, a digital Specific Questionnaire on Harmonised AMR Monitoring in 2017 and/or 2018 was drafted by the EFSA WG and the EURL‐AR using the tool ‘EU‐survey’ (Appendix B). In particular, the questionnaire was designed to better assess the vision of the MSs and to gauge the potential for further harmonisation of procedures and the degree of support from MSs for further monitoring. The online survey was performed in June 2018 and targeted the network of the NRL‐ARs and the EFSA Network on zoonoses/AMR monitoring. The questionnaire covered five aspects, specifically:

I: Methodologies applied to isolate Campylobacter spp. for antimicrobial susceptibility testing,

II: Monitoring of colistin resistance using selective media,

III: Characterisation of the ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase producers and related gene identification,

IV: Monitoring of MRSA in animals and food, and

V: First and second antimicrobial panels for susceptibility testing of Salmonella and E. coli.

In total, 27 MSs and 4 non‐MSs answered the questionnaire. The main findings of the Campylobacter survey (I) and the MRSA survey (IV) are summarised below, whereas the outcomes of the survey regarding the other aspects are presented in Appendices Appendix E – Outcome of the Specific Questionnaire Survey, EU MSs, June 2018: Monitoring of specific colistin resistance, Appendix F – Outcome of the Specific Questionnaire Survey, EU MSs, June 2018: Further characterisation of ESBL/AmpC/carbapenemase producers and corresponding genes identification, Appendix G – Outcome of the Specific Questionnaire Survey, EU MSs, June 2018: First and second panels for susceptibility testing of Salmonella and E. coli.

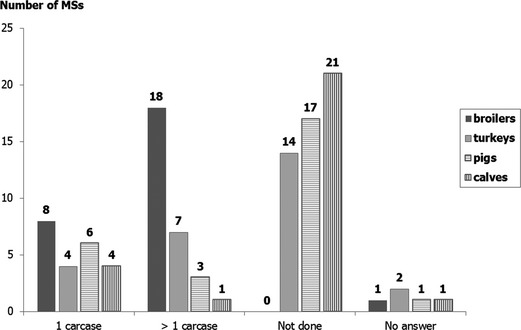

4.1. Campylobacter survey

To explore the potential for further harmonisation of procedures relating to the isolation process of Campylobacter isolates used for susceptibility testing among the MSs, a specific questionnaire survey addressed, among others, aspects related to the isolation methods used in laboratories providing Campylobacter isolates to the NRL‐ARs. The procedural aspects revealed by the survey as desirable candidates for potential further harmonisation are shortly presented in Table 3. More detailed information is also provided in Appendix C.

Table 3.

Main findings of the specific questionnaire survey relating to AMR monitoring in Campylobacter spp., EU MSs, June 2018

| Specific Topics | Collected Information |

|---|---|

|

Sampling procedure |

Variability in the number of samples collected and pooled (from 1 to 10) per slaughter batch was reported. For instance, a caecal sample from only one broiler was sampled in 8 MSs, whereas, in 15 MSs, a pool of caeca from ten broilers was collected. |

| Isolation method of Campylobacter |

Although from 1 up to 25 different laboratories were involved in the isolation of Campylobacter spp. for AMR monitoring in the reporting MSs, a single method was reported to be used for isolating Campylobacter strains for AMR monitoring in 23 MSs. Direct plating, without enrichment, of caecal contents, as described in the detection procedure C of the standard EN ISO 10272‐1 for samples containing high numbers of Campylobacter spp. was carried out in 23 MSs. Inoculation of two different agar media was reported in 16 MSs, from which 15 MSs used mCCDA. Either Karmali (this was considered not optimal, as both media contain the same inhibitor (cefoperazone)), Preston, blood agar, CFA, CASA or Skirrow media were used as second plate. |

| Over‐week‐end culturing | There were also differences between laboratories in the procedures used for cultures over week‐end periods, resulting for certain laboratories in cultures set up only on certain week days, in order to avoid any week‐end working. |

| Species identification |

Most countries reported using MALDI‐TOF mass spectrometry or PCR in accordance with the method of Denis et al. (1999). Microscopical examination, and/or oxidase, catalase, hippurate and indoxyl acetate tests were also performed by several countries. Regarding the number of colonies selected for identification, variability between countries occurred, with one to five colonies identified per sample. This may impact the assessment of the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. and the proportion of C. jejuni/C. coli in a sample. |

| Use of ISO Standarda | 21 MSs reported its use in various contexts, and 19 MSs being accredited for this method. |

AMR: antimicrobial resistance; MS: Member State; mCCDA: modified charcoal‐cefoperazone‐deoxycholate agar; CFA: campyfood agar plate; CASA: Campylobacter selective chromogenic medium; MALDI‐TOF: Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization – Time of Flight; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

European standard EN ISO 10272‐1.

The specific questionnaire survey therefore revealed as desirable and reasonable to propose and implement a harmonised protocol based on the European standard EN ISO 10272‐1, detection procedure C, including precise recommendations (e.g. number of carcases sampled, maximum elapsed time before analysis, number and nature of selective media, scheme and number of colonies to be checked for species identification) to the MSs, in order to enhance further the harmonisation of AMR monitoring in Campylobacter.

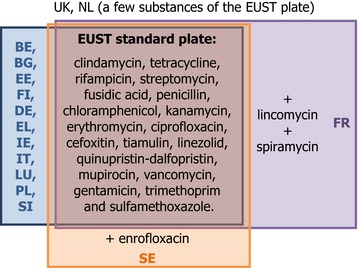

4.2. MRSA survey

To assess the potential for harmonisation of procedures relating to MRSA and to gauge the degree of support from MSs for further monitoring, the specific questionnaire survey also addressed questions relating to MRSA. The main findings are summarised in Tables 4 and 5, with more detailed information provided in Appendix D.

Table 4.

Main findings of the specific questionnaire survey relating to MRSA monitoring, EU MSs, June 2018

| Specific Topics | Collected Information |

|---|---|

| Sample types | Considering the matrix from which MRSA isolation was attempted, 7/27 MSs tested meat, 10/27 MSs tested nasal and/or skin swabs, 9/27 tested environmental samples (dust or boot swabs) and 5/27 tested other samples such as milk. |

| Animal populations |

Considering poultry, 3 MSs monitored healthy broilers on farms for MRSA; 1 MS also monitored healthy turkeys on farms. The frequency of testing was 3 years (2 MS) or 3–5 years (1 MS). Three MSs monitored healthy cattle on farms (2 MSs) or both at farm and abattoir level (1 MS) at intervals of 3 years (1 MS) or 3–5 years (1 MS) with monitoring set to begin in the Netherlands. Germany also monitored veal calves and milk/bulk milk from dairy cows. Five MSs monitored healthy pigs for MRSA either at abattoirs (2 MSs) or on farms (3 MSs) at a frequency of 2 years (1 MS), 3 years (1 MS), 3–5 years (1 MS) or irregularly (1 MS). |

| MRSA isolation method | 9/27 MSs reported using a two‐step (2S) method for MRSA isolation, while 5/27 used a one‐step (1S) method.a One MS employed a slight variation of the 2S method. The 1S and 2S methods are discussed further elsewhere in this report. |

| Susceptibility testing | The majority of responding MSs determined the susceptibility of MRSA isolates by broth microdilution.b All MSs performing broth microdilution used EUCAST thresholds to interpret resistance results; of the four MSs performing disc diffusion, three used CLSI breakpoints, while one used EUCAST disc diffusion breakpoints. Considering those MSs performing broth microdilution susceptibility testing, all MSs tested a common core panelc (EFSA, 2012b). |

| Samples collected | The preferred sampling site in live pigs or pigs after slaughter was nasal or skin swabs, while in poultry (broilers and turkeys), cloacal, oral and skin (including underwing) swabs were favoured. Nasal swabs were the only reported option for sampling veal calves, while milk or bulk milk was collected from lactating bovine animals. 12/27 MSs reported collecting and testing samples from the farm environment, with 11/27 testing dust and four of these also testing boot swabs. One MS tested only boot swabs. |

| MRSA characterisation | 13/27 MSs reported the use of spa‐typing to characterise MRSA isolates. Four MSs used WGS, SCCmec and multilocus sequence typing to characterise isolates. |

MRSA: methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MS: Member State; EUCAST: European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; CLSI: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

An abbreviated protocol described in Larsen et al. (2017).

Susceptibility testing of MRSA isolates was performed by 13/27 MSs using broth microdilution and 4/27 using disc diffusion; 11/27 MSs either did not test or did not respond to this question.

Of the following antimicrobials: clindamycin, tetracycline, rifampicin, streptomycin, fusidic acid, penicillin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, cefoxitin, tiamulin, linezolid, quinupristin‐dalfopristin, mupirocin, vancomycin, gentamicin, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. One MS tested additionally enrofloxacin, while France tested lincomycin and spiramycin.

Table 5.

National monitoring programmes in place for meat and milk in the MSs, as reported in the specific questionnaire survey, EU MSs, June 2018

| Meat or meat products | MSs | At abattoirs/At retail | Frequency of monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| From Broilers |

AT, DE |

At retail (AT), Both (DE) |

Every 2nd year (AT), Every 3–5 years (DE) |

| From Turkeys | DE | Both (DE) | Every 3–5 years (DE) |

| Beef | DE | Both (DE) | Every 3–5 years (DE) |

| Pork |

AT, FI, DE |

At retail (AT, FI), Both (DE) |

Every 2nd year (AT), Every 3–5 years (DE), Not regularly (FI) |

| From Veal Calves, Milk | DE | – | – |

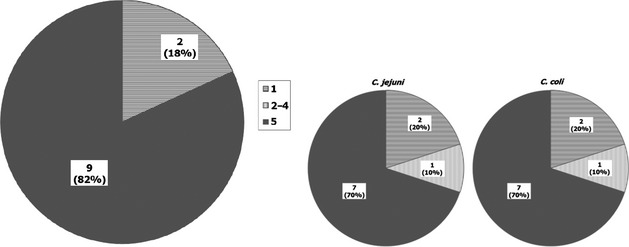

Regarding the possible further EU‐wide surveillance of MRSA, 19/27 MSs (70%) considered that would be useful in food‐producing animals, a view also expressed by two responding non‐MSs. Only one MS disagreed and 7/27 did not respond to this question. The main animal species considered the highest priority for further EU‐wide monitoring were pigs (18/27 MSs), broilers (15/27 MSs), veal calves (10/27 MSs) and turkeys (7/27 MSs). Those species mentioned by MSs infrequently in the responses received included beef and dairy cattle and companion animals. Of the 27 MSs, 7 favoured farm‐based surveys of pig and/or poultry farms to assess herd or flock level prevalence and diversity, while 9/27 MSs favoured abattoir‐based surveillance to assess the diversity of MRSA in pigs and/or poultry, recognising that cross‐contamination between animals may occur at slaughter. Fewer MSs (11/27, 40%) favoured further EU‐wide monitoring of meat, with 30% expressing the contrary view and 30% not expressing a view. The types of meat considered of highest priority were the same as those reported for food‐producing animals (pork and chicken then with less support, meat from turkeys and veal calves).

5. Objectives of monitoring AMR from a public health perspective

The monitoring of AMR in food‐producing animals and food is essential to provide comprehensive, comparable and reliable information on the development and spread of drug‐resistant bacteria, to measure the impact of measures taken to reduce AMR and to monitor progress. The continually evolving threat from emerging resistance has underlined the need to strengthen further AMR monitoring and to constantly review the data collected, interpret the findings and assess trends to inform, update and consolidate national action plans against AMR based on a ‘One Health’ approach.

The monitoring of AMR in food‐producing animals and food is intended to be performed in close relationship with the surveillance of AMC in food‐producing animals, as well as with the AMR and AMC monitoring programmes in humans. Such AMR and AMC data provide valuable insights to inform decision‐making and facilitate the development of appropriate strategies and actions to manage AMR at European, national and regional levels. The first EU‐wide integrated analyses of data on the consumption of antimicrobial agents and the occurrence of AMR in bacteria from humans, food‐producing animals and food, were jointly performed by ECDC, EFSA and EMA (JIACRA I and JIACRA II), and showed positive correlation between AMC and AMR. Such analyses are intended to be carried out on a regular basis.

The present technical specifications aim at improving the comparability and the reliability of the AMR data collected by the MSs and enlarging the scope of the monitoring. Recent developments, including the increasing use of molecular monitoring through whole genome sequencing, are acknowledged and have been incorporated into the monitoring programme. The detailed characterisation of isolates at the molecular level facilitates comparison of AMR in humans and animals at several levels, including the occurrence and types of resistance genes, resistance plasmids and the host bacterial organism. The technical specifications set out proposals whereby molecular monitoring in selected bacteria can be progressively implemented across all MSs, while retaining comparability with the phenotypic monitoring which is currently in place.

Comparability with the monitoring performed in previous years is an important over‐arching consideration, which has been taken into account at all levels when revising the technical specifications. The data collected in previous years provide an important resource against which future trends can be evaluated. AMR in certain bacterial organisms occurring in food or food‐producing animals has been monitored under Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU for several years; the revised technical specifications propose the expansion of the monitoring to include other selected bacterial species and sample types in mandatory monitoring or ‘baseline’ surveys, provide a rationale for their inclusion, and propose recommendations on the frequency of monitoring.

The requirement to provide information on the current AMR situation in food‐producing animals and food, has been considered against the background of EU and national initiatives focussing on AMR and AMC and the reductions in AMC which have been achieved in a number of MSs. The different sizes of the various livestock sectors in the different MSs have been considered and proposals developed to ensure comparability of monitoring while at the same time ensuring their cost‐effectiveness.

6. Rationale for revising the current AMR monitoring system

6.1. To adapt the monitoring to emerging AMR and current priorities

6.1.1. Inclusion of AMR monitoring in C. coli

6.1.1.1.

Campylobacter coli is a human pathogen

The ECDC/EFSA EU Summary Report on zoonoses reported 246,158 confirmed cases of human campylobacteriosis in the EU in 2017. C. jejuni and C. coli were associated with, respectively, 84.4% and 9.2% of those confirmed cases for which Campylobacter species information was reported (EFSA and ECDC, 2018b), representing more than 20,000 human cases of C. coli infections. Certain countries recorded even higher proportions of confirmed C. coli infections, such as France, where 15% of human cases were linked to C. coli (CNR‐Campylobacter, online), whereas lower proportions of confirmed clinical C. coli infections were also registered in certain EU MSs, for example, at 5–6% in Poland (Sadkowska‐Todys and Kucharczyk, 2016). In the USA, approximately 10% of human cases were associated with C. coli (Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017). It is unknown whether those disparities reflect either true differences in epidemiological conditions (varying sources of infection) or discrepancies in surveillance and reporting systems between countries (mandatory/voluntary notification of cases, surveillance coverage, analytical methods).

C. coli is more often resistant than C. jejuni to several antimicrobials, and particularly to erythromycin, a resistance that is usually rare in C. jejuni

Considering Campylobacter isolates from human cases in Europe in 2016, the levels of resistance to erythromycin and gentamicin in C. coli (at 11.0% and 1.7%, respectively) were markedly higher than those observed in C. jejuni (at 2.1% and 0.4%, respectively) (EFSA and ECDC, 2018a). The combined resistance to ciprofloxacin and erythromycin was low in C. jejuni (0.6%) but moderate in C. coli (8.0%). A higher level of resistance in C. coli compared with C. jejuni was also reported at the country level. In France, C. coli was more often resistant to macrolides, fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines (CNR‐Campylobacter, online), whereas, in the USA and Spain, resistance to macrolides was more frequently reported in C. coli than in C. jejuni (Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017).

Considering animal sources, C. coli was found more often resistant to ciprofloxacin than C. jejuni in poultry in the USA, even after the ban of enrofloxacin (Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017). In Europe, in 2016, C. coli in poultry were significantly more often resistant to ciprofloxacin than C. jejuni. The comparison is however limited to a few countries testing susceptibility in both species, as C. coli was not tested in many countries (EFSA and ECDC, 2018a). In the USA, in retail meat (mainly poultry), higher rates of AMR (except for tetracycline) were described in C. coli than in C. jejuni (Zhao et al., 2010). Similar observations were also made in other animal productions. In France, C. coli from calves was more frequently resistant to tetracyclines, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin (Chatre et al., 2010), whereas, in Poland, C. coli from pig and cattle carcasses were significantly more often resistant to streptomycin and tetracycline than C. jejuni (Wieczorek and Osek, 2013). In the USA, high levels of erythromycin resistance were also reported in C. coli from chickens, turkeys, cattle and market swine in comparison with C. jejuni (Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017).

C. coli may contain and transfer important and emerging antimicrobial resistance genes to C. jejuni

The erm(B) gene encodes an rRNA methylase responsible of resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B antibiotics and is frequently encountered in various Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria19 in animals (Roberts, 2008). It was recently described in Campylobacter in China, where it was more frequently observed in C. coli than in C. jejuni, and was shown to confer high‐level resistance to macrolides (Liu et al., 2017). In Europe, up to now, erm(B) has been detected only in a few C. coli isolates from broilers and turkeys in Spain (Florez‐Cuadrado et al., 2017) and from a broiler isolate in Belgium (Elhadidy et al., 2019). In Campylobacter, this gene is present either on plasmids or, more frequently, on multidrug resistance islands (MDRI), also containing other resistance genes, such as tet(O) coding for tetracycline resistance and aminoglycosides resistance genes, such as aad9, aadE, aph(2”)‐IIIa and aacA‐aphD (Florez‐Cuadrado et al., 2017). The MDRI can be transferred to a macrolide susceptible C. jejuni by natural transformation (Wang et al., 2014).

C. coli may contain the cfr(C) gene conferring resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, pleuromutilins and oxazolidinones. It was first detected in C. coli isolates of cattle origin in various states of the USA. The gene is located on a conjugative plasmid and can transfer various traits of resistance to a C. jejuni recipient strain (Tang et al., 2017). The cat gene conferring resistance to phenicols (Li et al., 2017) was found to be more frequent in C. coli than in C. jejuni from broilers in live bird markets in China (Li et al., 2017).

The presence in Campylobacter of these resistance genes, plasmids and MDRI is worrisome, as they not only enable their bacterial host to resist to one or several important therapeutic options, but also because they can lead to co‐selection of multidrug‐resistant Campylobacter isolates, by use of other antimicrobials. As these resistances seem more frequent in C. coli but can be transferred to C. jejuni, it is important to detect their presence in the C. coli population at an early stage.

C. coli is more prevalent than C. jejuni in poultry in several countries

Although C. jejuni has for long been considered as the prominent Campylobacter species in poultry, it has been recently reported that C. coli may be more often detected, for example in France, Hungary and Spain (EFSA and ECDC, 2014).20 The actual prevalence of C. coli and C. jejuni in poultry production likely depends on various factors, including the production type, AMC (Avrain et al., 2003) and the age of the birds sampled (El‐Shibiny et al., 2005). Those factors may vary between countries and likely yield differences. The observed proportions of Campylobacter species among isolates however also depend on the isolation methods, as certain media may favour one Campylobacter species over another (Reperant et al., 2016). The identification of a low number of colonies at the species level in a sample will, in most cases, result in the detection of the dominant species. The detection of the different species present in a sample, particularly when the numbers of cells of each species differ substantially, may necessitate the analysis of many colonies or the use of different species‐selective or species‐favouring media/protocols. It is therefore desirable to ensure a greater degree of harmonisation of the isolation protocols to ensure a relevant comparison between countries in terms of prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli.

6.1.1.1.1.

Proposal: To include C. coli from poultry, fattening pigs and bovines of less than 1 year of age in the harmonised monitoring of AMR, because of its importance as a food‐borne zoonotic pathogen and a potential reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes (e.g. transferable macrolide resistance genes). Where samples are already collected and tested for Campylobacter spp., susceptibility testing on isolates of both C. jejuni and C. coli, where relevant, will only induce a limited additional cost compared with susceptibility testing on isolates of C. jejuni only.

6.1.2. Inclusion of monitoring of MRSA

The EFSA scientific report on technical specifications on the harmonised monitoring and reporting of AMR in methicillin‐resistant S. aureus in food‐producing animals and food (EFSA, 2012b) provided the rationale for monitoring of MRSA. An EU‐wide baseline survey was performed in 2008 to obtain comparable preliminary data on the occurrence and diversity of MRSA in primary pig production in all MSs through a harmonised sampling scheme (EFSA, 2009). Pooled dust samples collected from pig holdings were tested for MRSA and all isolates were subjected to spa‐typing and determination of their MRSA status. The survey results indicated that MRSA was common in breeding pig holdings in some MSs, while, in other MSs, the prevalence was low (EFSA, 2010). MRSA ST398 was by far the most predominant MRSA lineage identified. Further investigation of the diversity of MRSA spa‐types also showed that the distribution of spa‐types differed significantly between countries. These revised technical specifications (as in the current report) take account of recent developments and propose a harmonised methodology to be used in the monitoring of MRSA in the most relevant production animals and foodstuffs throughout the EU, updating the previous EFSA technical specifications (EFSA, 2012b) where appropriate.

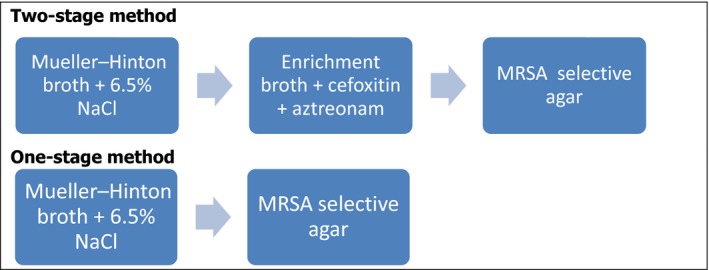

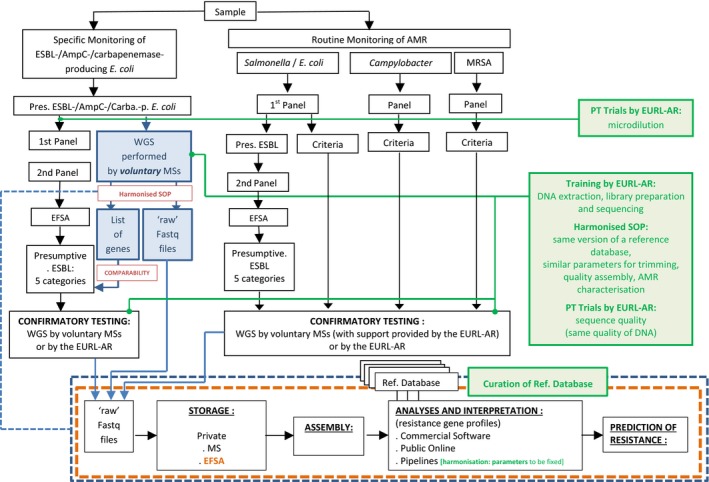

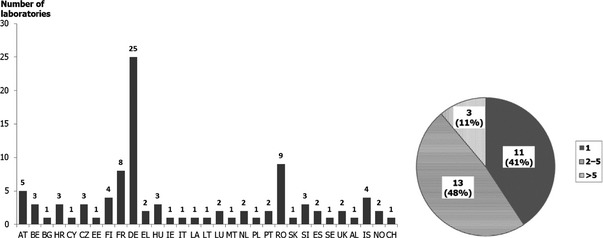

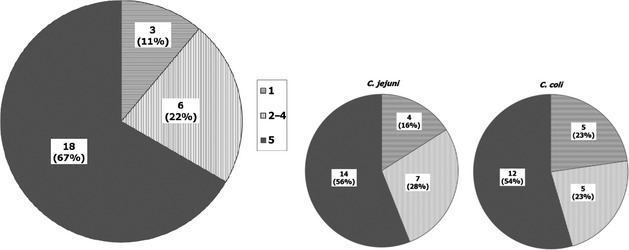

Relatively few MSs have reported regular monitoring for MRSA in food‐producing or other animals or meat derived from those animals to EFSA (EFSA and ECDC, 2019). Monitoring in recent years has, although performed on a voluntary basis, provided significant results, including data regarding the occurrence of different strains or lineages of MRSA in animals, the occurrence of virulence or host adaptation factors in MRSA detected in animals and the occurrence of resistance to antimicrobials other than methicillin in those MRSA. The features detected in the monitoring performed in recent years by the MSs provide strong evidence of the relevance and value of ongoing monitoring. Considering those MSs reporting the results of monitoring programmes for MRSA in animals or food to EFSA, some have reported data only on the occurrence of MRSA, while others have reported additional molecular typing and antimicrobial susceptibility data. The low numbers of MSs voluntarily reporting MRSA data as well as the lack of complete harmonisation of monitoring programmes, provide only a limited assessment of the occurrence and characteristics of MRSA currently occurring in animals at the EU level. These issues were also discussed in the previous recommendations (EFSA, 2012b) and are summarised below.