Abstract

The CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), which anchors DNA loops that organize the genome into structural domains, has a central role in gene control by facilitating or constraining interactions between genes and their regulatory elements1,2. In cancer cells, the disruption of CTCF binding at specific loci by somatic mutation3,4 or DNA hypermethylation5 results in the loss of loop anchors and consequent activation of oncogenes. By contrast, the germ-cell-specific paralogue of CTCF, BORIS (brother of the regulator of imprinted sites, also known as CTCFL)6, is overexpressed in several cancers7–9, but its contributions to the malignant phenotype remain unclear. Here we show that aberrant upregulation of BORIS promotes chromatin interactions in ALK-mutated, MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma10 cells that develop resistance to ALK inhibition. These cells are reprogrammed to a distinct phenotypic state during the acquisition of resistance, a process defined by the initial loss of MYCN expression followed by subsequent overexpression of BORIS and a concomitant switch in cellular dependence from MYCN to BORIS. The resultant BORIS-regulated alterations in chromatin looping lead to the formation of super-enhancers that drive the ectopic expression of a subset of proneural transcription factors that ultimately define the resistance phenotype. These results identify a previously unrecognized role of BORIS—to promote regulatory chromatin interactions that support specific cancer phenotypes.

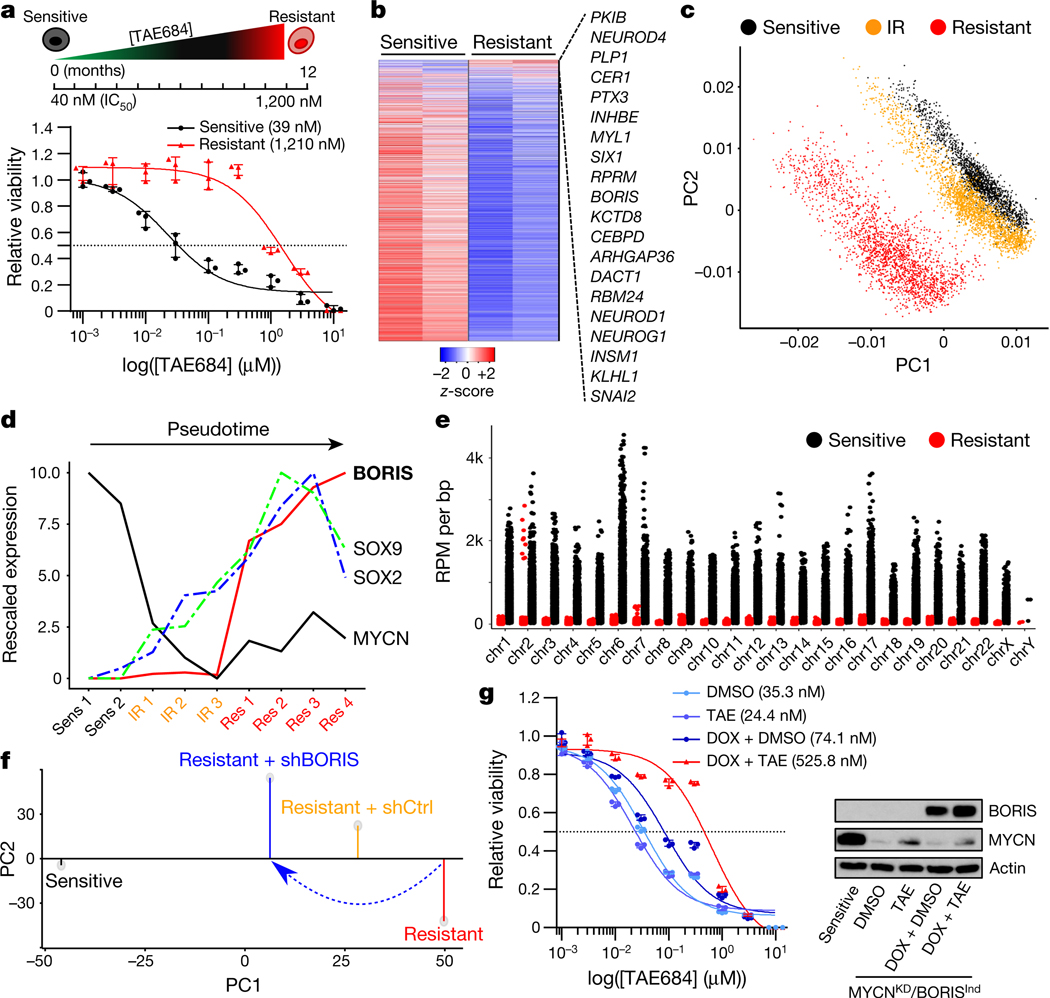

Unlike CTCF, which is uniformly expressed in healthy tissues and cancer cells, the expression of BORIS is typically restricted to the testis6 and embryonic stem cells11 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). However, when aberrantly expressed in cancer7–9, it is associated with high-risk features that include resistance to treatment (Extended Data Fig. 1b, c). We identified BORIS as one of the most differentially expressed genes in neuroblastoma cells driven by amplified MYCN12 and ALK(F1174L)13 and rendered resistant to ALK inhibition. Kelly human neuroblastoma cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of the ALK inhibitor TAE68414 until stable resistance was achieved (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). The acquisition of stable resistance coincided not only with the loss of ALK phosphorylation—which indicates that the cells no longer required activation of this receptor tyrosine kinase to maintain their oncogenic properties—but also with the absence of other common instigators of resistance (Extended Data Fig. 2a, e–h; Supplementary Note 1). However, comparison of the gene expression profiles of the TAE684-sensitive and resistant cells showed generalized downregulation of transcription in the resistant cells, but with marked upregulation of a subset of transcription factors not typically associated with neuroblastoma cells15,16 (Fig. 1b).

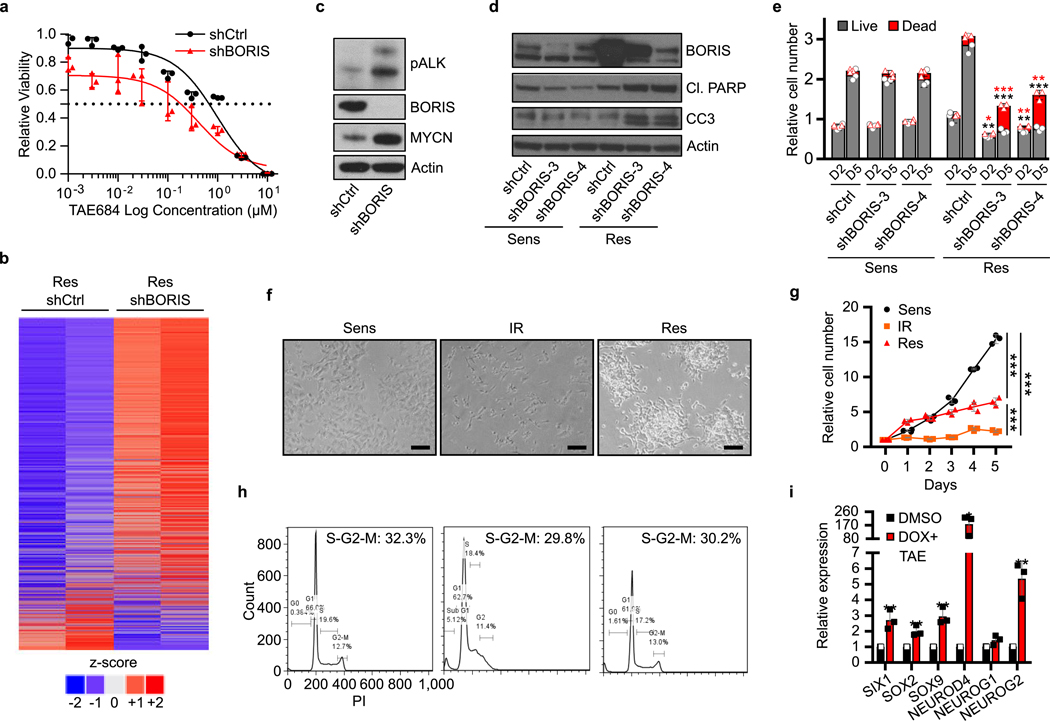

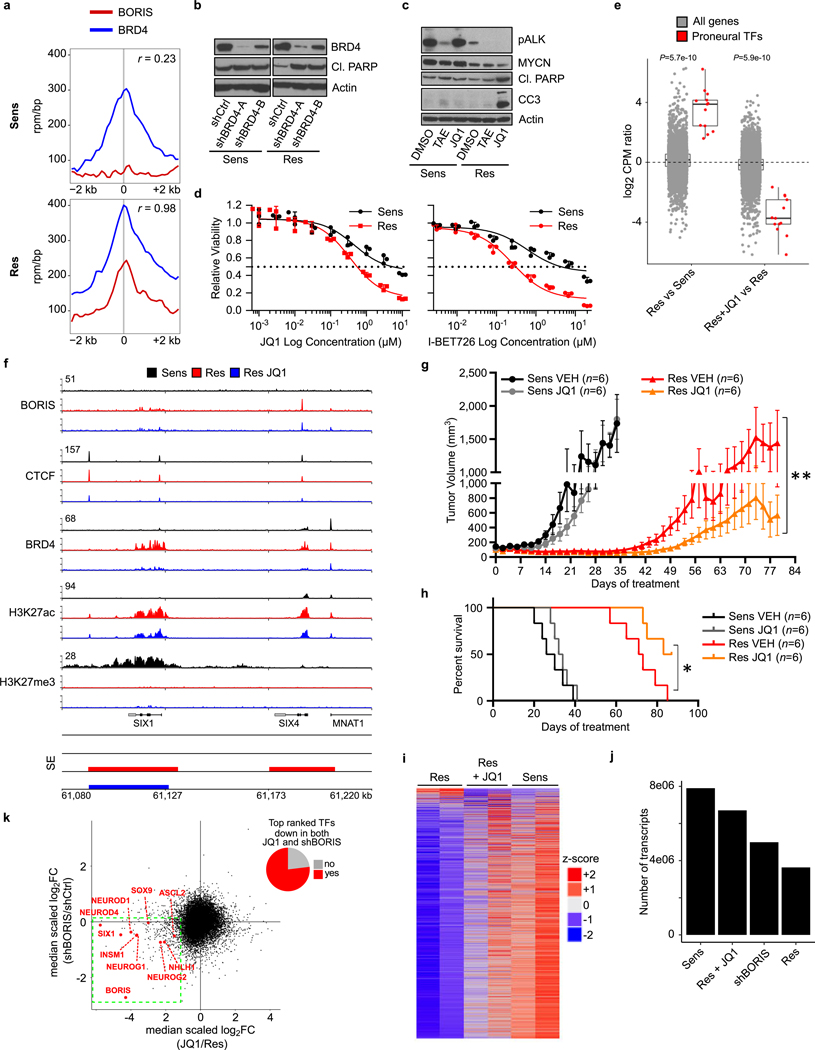

Fig. 1 |. Targeted therapy resistance in neuroblastoma is associated with transcriptional reprogramming and a switch in dependency from amplified MYCN to BORIS.

a, Top, schematic representation of the development of resistance. Bottom, dose–response curves of TAE684-sensitive and -resistant Kelly neuroblastoma cells incubated in increasing concentrations of TAE684 for 72 h. Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates. b, Heat map of gene expression values in sensitive versus resistant cells (n = 2 biological replicates). Rows are z-scores calculated for each gene in both cell types. c, PCA of scRNA-seq data of sensitive (n = 5,432), intermediate resistant (IR; n = 6,376) and resistant (n = 6,379) cells showing the first two principal components (PCs). d, Pseudotime analysis of transcription factor expression during the development of resistance. e, ChIP–seq signals of genome-wide MYCN binding in sensitive and resistant cells, reported as reads per million (RPM) per base pair (bp) for each chromosome (chr). f, PCA of gene expression profiles showing the first two principal components (n = 2 biological replicates). g, Dose–response curves for TAE684 (half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in parenthesis) and immunoblot analysis (representative of two independent experiments) of BORIS and MYCN expression in sensitive cells expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against MYCN (MYCNKD) and doxycycline-inducible BORIS (BORISInd), treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or 1 μM TAE684, with or without doxycycline (DOX). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates.

We therefore proposed that the resistant cells had probably undergone transcriptional reprogramming during the development of resistance. To determine the dynamics of resistance development, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis on sensitive, intermediate and fully resistant cell states (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Principal component analysis (PCA) indicated a stepwise transition as cells progressed from the sensitive to the fully resistant state (Fig. 1c). This transition was confirmed by distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE)17, which clustered the cells into three non-overlapping categories (Extended Data Fig. 3b, c). Pseudotime analysis based on the transcription factors that were differentially expressed throughout the development of resistance revealed that the initial major alteration was loss of MYCN expression, which persisted in stably resistant cells (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 3d, e). To understand this unexpected result, we analysed the status of MYCN in these cells, and found that although genomic amplification was retained, the MYCN locus was epigenetically repressed (Extended Data Fig. 3f, g). This state was accompanied by a genome-wide reduction of MYCN binding to DNA and a consequent revision of associated downstream transcription outcomes15,18,19 (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 3h). Coincident with this loss of transcriptional activity, the resistant cells were no longer dependent on MYCN for survival, unlike their sensitive controls, which underwent apoptosis after depletion of MYCN (Extended Data Fig. 3i). Subsequent resistance stages were defined by a gradual increase in the expression of the neural developmental markers SOX2 and SOX920, followed by upregulation of BORIS, ultimately leading to a fully resistant state in which BORIS expression was highest and detectable in essentially all cells (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 3j, k). Overexpression of BORIS, which coincided with promoter hypomethylation (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b), was also observed in additional neuroblastoma cell lines rendered resistant to TAE684 (SK-N-SH) or the CDK12 inhibitor E921 (SK-N-BE(2)) (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d), which suggests that our findings are not restricted to a single cell line or kinase inhibitor. Indeed, overexpression of BORIS in tumours was significantly associated with high-risk disease and a poor outcome in patients with neuroblastoma treated with a variety of regimens (Extended Data Fig. 4e–g).

To clarify the role of BORIS in the resistance phenotype, we depleted its expression in resistant cells, and observed a partial reversal to the sensitive-cell state with re-emergence of MYCN and ALK expression (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). However, this outcome was insufficient to maintain cell growth, as depletion of BORIS in resistant cells ultimately decreased cell viability (Extended Data Fig. 5d, e), which indicates a switch from MYCN to BORIS dependency with stable resistance. This transition was associated with changes in cellular growth kinetics—from a highly proliferative, MYCN-overexpressing sensitive state to an intermediate, slow-cycling phenotype that was partially reversed in fully resistant cells, coincident with overexpression of BORIS (Extended Data Fig. 5f–h). Given the many sequential steps involved in the evolution of resistance, overexpression of BORIS alone was not adequate to induce this phenotype (data not shown). Instead, concomitant downregulation of MYCN expression and BORIS overexpression in the presence of ALK inhibition were required to generate resistance in sensitive cells (Fig. 1g). This combination of factors also led to increased expression of the transcription factors that were upregulated in the original TAE684-resistant cells, including SOX2 and SOX9 (Extended Data Figs. 3d, 5i). Thus, resistance to inhibition of ALK in neuroblastoma cells evolves through a multistep process that promotes a dependency switch from a dominant oncogenic stimulus—amplified MYCN—to a phenotypically distinct state characterized by overexpression of BORIS. In this context, the resistant cells ultimately become dependent on BORIS for survival, which supports a key role for this protein in maintenance of the resistance state.

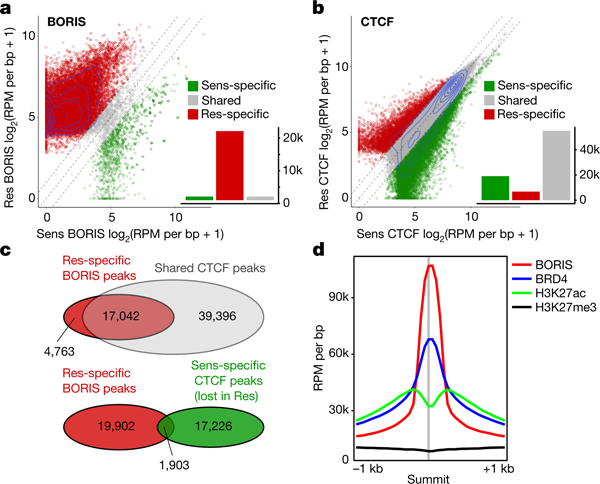

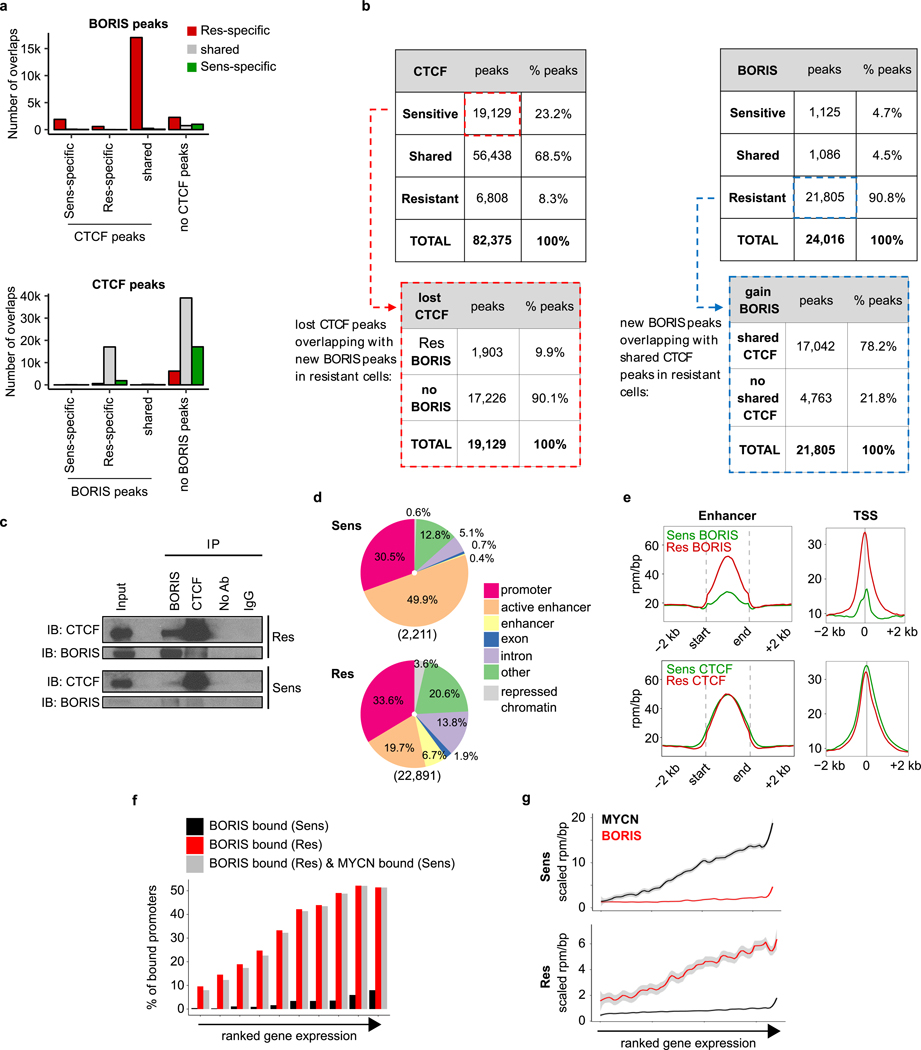

We next asked whether the aberrant expression of BORIS, a DNA-binding protein6, affected its genome-wide occupancy in resistant cells. We observed a large (tenfold) gain in BORIS-bound peaks after chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP–seq) analysis in resistant cells: 22,891 versus 2,211 in sensitive cells (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). By contrast, CTCF binding did not change substantially between sensitive and resistant cells (75,567 versus 63,246 peaks) (Fig. 2b). A considerable portion (n = 17,042; 78%) of the BORIS peaks unique to resistant cells overlapped with CTCF peaks shared by both cell types (Fig. 2c), consistent with their heterodimerization22 (Extended Data Fig. 6c). However, only a small proportion (n = 1,903; 8.7%) overlapped with CTCF peaks unique to sensitive cells, which suggests that BORIS does not replace CTCF in resistant cells. BORIS preferentially occupied gene regulatory regions—enhancers and promoters (60%)—in resistant cells (Extended Data Fig. 6d, e), which is consistent with its propensity to bind to open chromatin regions23 (Fig. 2d). Such differential chromatin binding at distinct highly expressed genes in resistant versus sensitive cells was commensurate with the MYCN-to-BORIS dependency switch (Extended Data Fig. 6f, g).

Fig. 2 |. BORIS overexpression is associated with its increased chromatin occupancy in resistant cells, whereas CTCF binding is unchanged.

a, Scatter plot of BORIS binding in sensitive (Sens) and resistant (Res) cells for all detected BORIS-binding sites. BORIS peaks unique to resistant cells (n = 21,805; 91%), sensitive cells (n = 1,125; 4.7%) and shared between the two cell types (n = 1,086; 4.5%) are shown. b, Scatter plot of CTCF binding in sensitive and resistant cells for all detected CTCF-binding sites. CTCF peaks unique to resistant cells (n = 6,808; 8.3%), sensitive cells (n = 19,129; 23.2%) and shared between the two cell types (n = 56,438; 68.5%) are shown. c, Overlap between BORIS peaks that are unique to resistant cells and CTCF peaks shared between resistant and sensitive cells (top), and between resistant cell-specific BORIS peaks and sensitive cell-specific CTCF peaks (bottom). d, Meta-analysis of average ChIP–seq signals at resistant cell-specific BORIS-binding sites. All panels, n = 2 biological replicates.

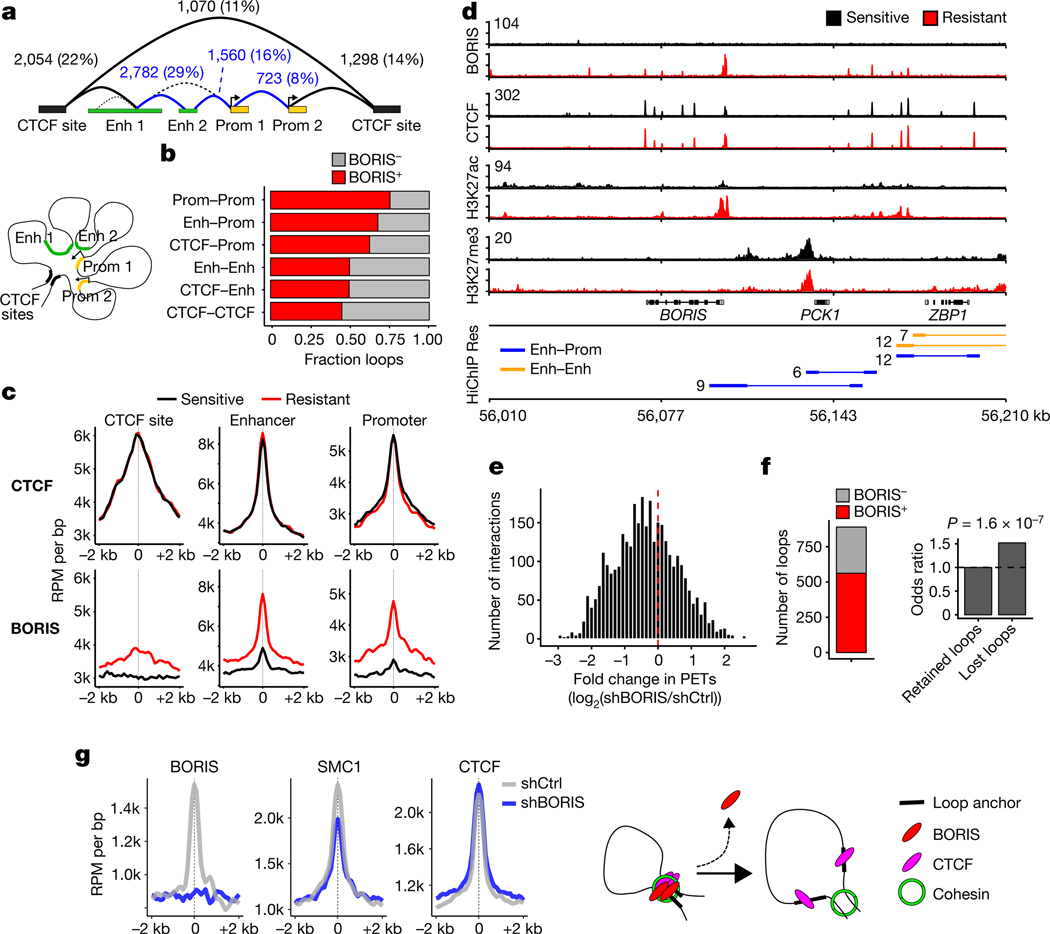

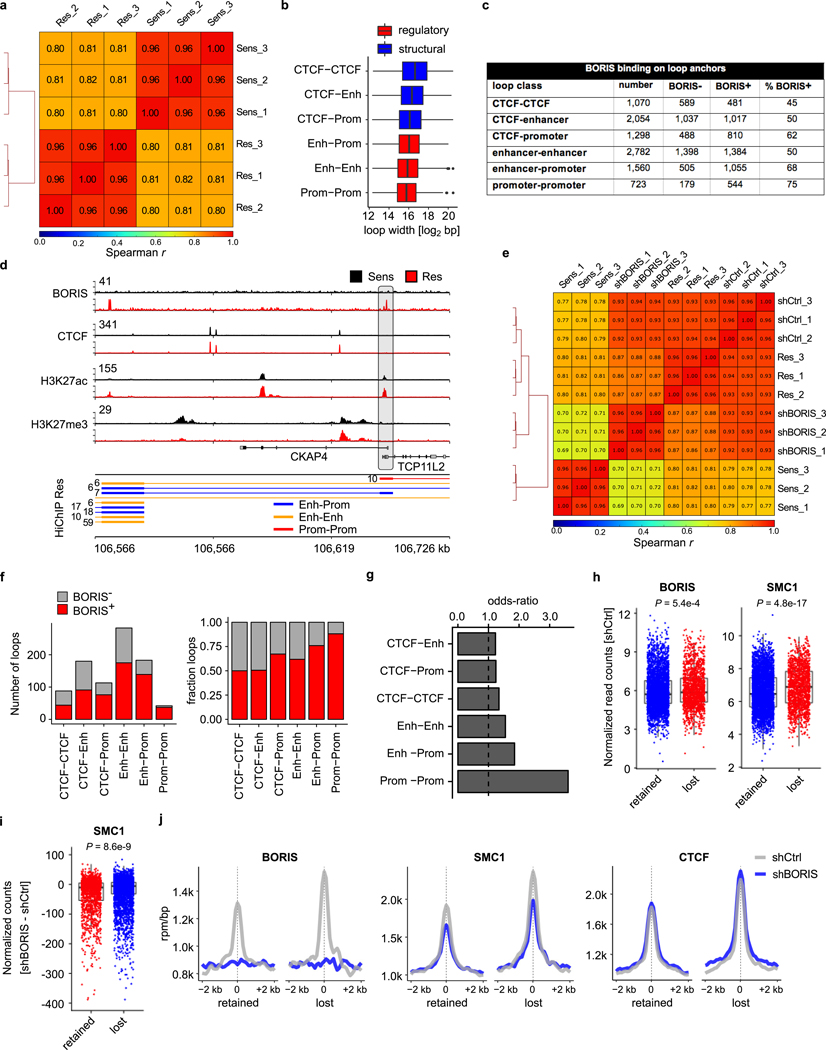

The proclivity of aberrantly expressed BORIS for genomic regions associated with active chromatin features in resistant cells suggested that it may, like CTCF and cohesin, regulate gene expression through chromatin looping. Thus, we examined the chromatin looping profiles of sensitive and resistant cells, using cohesin (SMC1A)-based high-throughput chromosome conformation capture followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (HiChIP)24 (Extended Data Fig. 7a). On the basis of the genomic locations of the associated loop anchors, six classes of interactions were identified25: three longer average interaction loops with a CTCF site on at least one anchor; and three smaller connecting regulatory regions (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 7b). The overlap of BORIS binding with loop anchors revealed that most (56%) of the 9,487 interactions gained in resistant cells were positive for BORIS (log2-transformed fold change > 1; false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01) (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 7c). Notably, BORIS was enriched at anchors that were associated with regulatory regions, whereas CTCF binding remained constant, as seen at the BORIS locus itself (Fig. 3c, d). In fact, BORIS binding alone at CTCF-negative loop anchors was sufficient to generate new interactions in resistant cells (Extended Data Fig. 7d).

Fig. 3 |. BORIS promotes new chromatin interactions in resistant cells.

a, DNA interactions gained in resistant cells based on SMC1A HiChIP analysis. Interaction classes were determined from the genomic locations of the associated anchors (overlapping promoter (Prom) regions (transcription start site (TSS) ± 2 kb), active enhancer (Enh) regions, or CTCF sites only, in that order). Absolute numbers and percentages for each loop type (structural (black), regulatory (blue)) are shown. Cartoon illustrates the spatial proximity induced by DNA looping between these regions. b, Fractions of loops bound by BORIS within each interaction class. c, Meta-analysis of average CTCF and BORIS ChIP–seq signals in sensitive and resistant cells at the three main anchor types normalized by the number of interactions (n = 2 biological replicates). Anchor sites were centred and extended in both directions (± 2 kb). d, ChIP–seq tracks of the indicated proteins in sensitive and resistant cells at the BORIS locus (representative of two independent experiments), with resistant cell-specific regulatory interactions shown below (HiChIP resistant: paired-end tag (PET) numbers, next to each interaction). Signal intensity is given in the top left corner for each track. e, PET interactions in BORIS-depleted (shBORIS) versus control (shCtrl) cells. f, Resistant cell-specific loops lost after depletion of BORIS based on loops negative or positive for BORIS binding in shCtrl cells (left), and the odds ratio of losing a loop previously bound by BORIS (right). P value determined by two-sided Fisher’s exact test. g, Meta-analysis of average BORIS, SMC1A and CTCF ChIP–seq signals at resistant cell-specific loop anchors that were lost after depletion of BORIS (n = 2 biological replicates). BORIS depletion at loop anchors inhibits retention of the cohesin complex, and thus prevents the formation of new loops (loop extrusion model). In a, b, e and f, n = 3 biological replicates.

To test whether the newly formed interactions in resistant cells were mediated by BORIS binding, we analysed the consequences of BORIS depletion on loop architecture (Extended Data Fig. 7e). Regulatory interactions specific to resistant cells displayed a global shift towards loss after knockdown of BORIS (Fig. 3e), with more than one-quarter of the total interactions lost, of which 63% were positive for BORIS at their anchors (Fig. 3f). Interactions in which anchors were bound by BORIS (especially enhancer–promoter and promoter–promoter interactions) were more likely to be lost after BORIS depletion than those that were not BORIS-bound (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 7f, g). These results agree with the loop extrusion model26, as BORIS loss resulted in decreased SMC1A binding, preferentially at lost interactions, whereas CTCF binding did not change significantly (Fig. 3g, Extended Data Fig. 7h–j). These data confirm that BORIS is a crucial factor in the looping landscape of resistant cells.

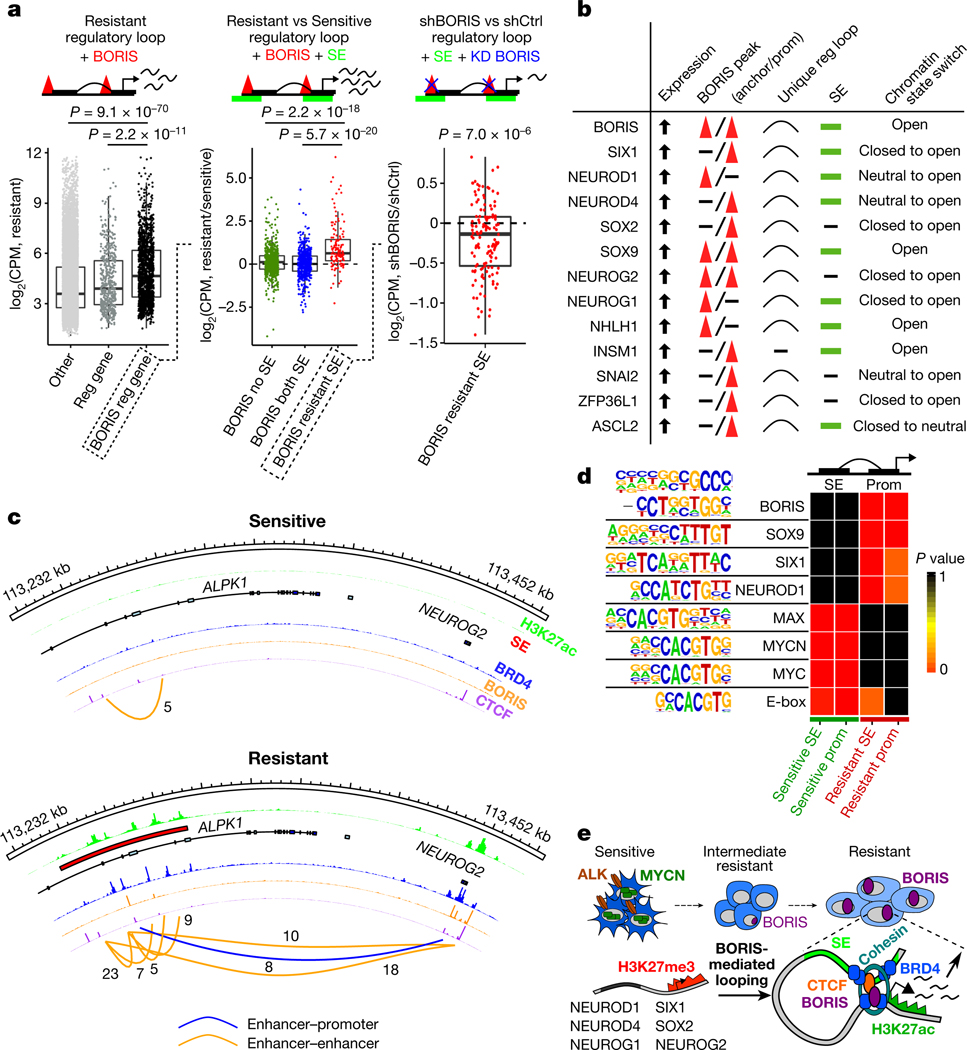

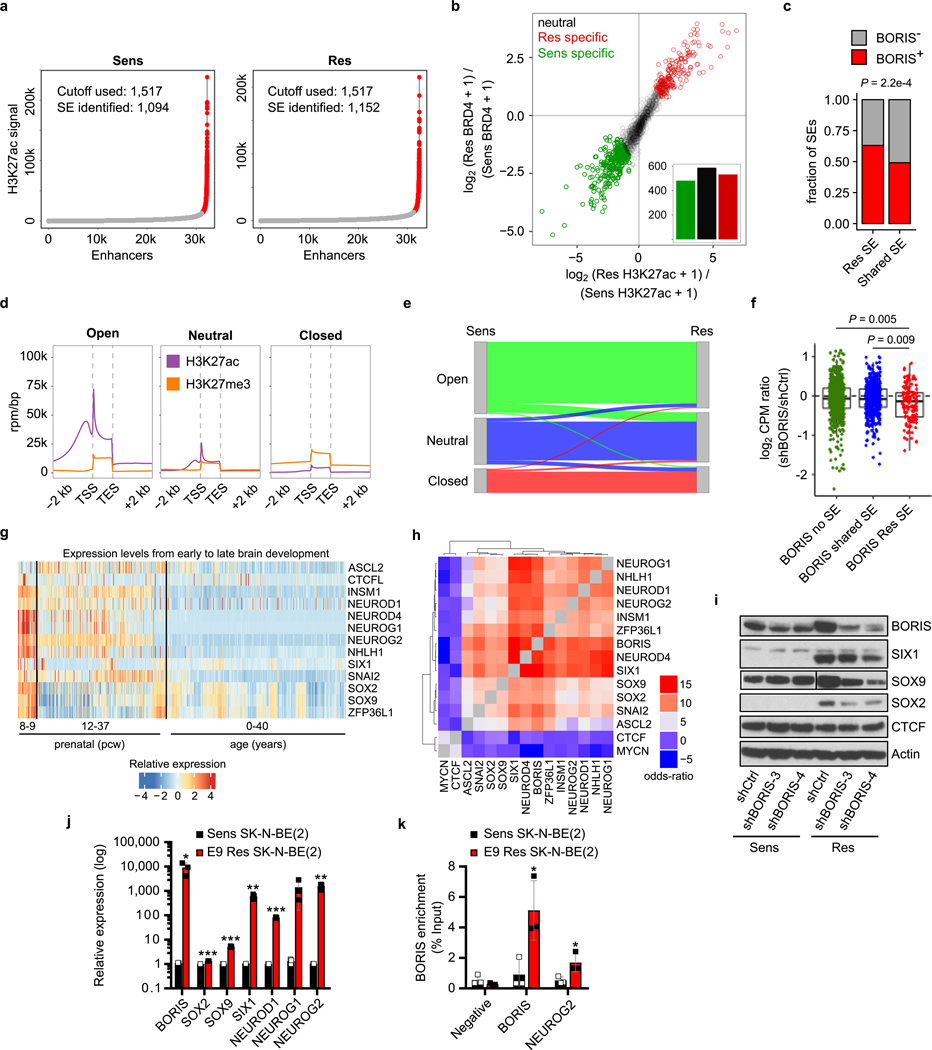

Genes associated with new BORIS-positive regulatory interactions were expressed at higher levels than those associated with BORIS-negative regulatory interactions or genes not associated with new regulatory interactions (Fig. 4a). Because genes that define cell identity are often regulated by super-enhancers in both healthy and cancer cells15,27,28, we characterized the super-enhancer landscape of our cells, observing that the super-enhancers unique to resistant cells were enriched at BORIS-positive regulatory loops (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). The presence of such super-enhancers correlated significantly with higher expression of their associated genes in resistant versus sensitive cells (Fig. 4a). These BORIS-positive super-enhancer-associated genes were also enriched for genes that underwent a chromatin state switch from a closed or neutral to an open configuration in resistant cells (Extended Data Fig. 8d, e). Depletion of BORIS resulted in the decreased expression of genes associated with BORIS-positive interactions, especially genes associated with resistant cell-specific super-enhancers (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 8f). These observations suggest that BORIS-mediated alterations in chromatin looping lead to interactions of newly formed super-enhancers with their target genes, which results in their increased expression.

Fig. 4 |. BORIS-regulated chromatin remodelling supports a phenotypic switch that maintains the resistant state.

a, Left, fold change in expression in counts per million (CPM) of genes involved in resistant cell-specific regulatory interactions that are positive for BORIS binding (n = 1,368) versus those involved in regulatory interactions that are negative for BORIS binding (n = 519) or not associated with a new regulatory interaction (other) (n = 16,151). Centre, fold change in expression of genes involved in resistant cell-specific regulatory interactions positive for BORIS binding and associated with super-enhancers (SEs) specific to resistant cells (n = 134) versus those with super-enhancers shared by both cell types (n = 514) or not associated with super-enhancers (n = 720). Right, fold change in expression of genes involved in resistant cell-specific regulatory interactions positive for BORIS binding and associated with resistant cell-specific super-enhancers before and after BORIS knockdown (KD) (n = 134) (P values determined by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). For all box plots, centre lines denote medians; box limits denote twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles; whiskers denote minima and maxima (1.5× the interquartile range). b, Highest-ranked transcription factors associated with the resistance phenotype selected based on the presence of at least four of the five indicated features. c, ChIP–seq tracks of the indicated proteins in sensitive and resistant cells at the NEUROG2 locus; regulatory interactions with PET numbers indicated below. d, Transcription factor recognition motifs at super-enhancers and promoters (± 2 kb) of the 1,000 highest-expressed genes in resistant and sensitive cells (n = 2 biological replicates) (P values determined by hypergeometric enrichment test). Panels a–c integrate data of biological replicates from expression microarrays (n = 2), ChIP–seq (n = 2) and HiChIP (n = 3). e, Proposed role of BORIS in resistant cells.

We next sought to identify BORIS-regulated genes that are functionally linked to the resistance phenotype by integrating gene expression, BORIS-mediated looping, super-enhancer landscape and chromatin state. This analysis revealed 89 genes (Supplementary Table), including 13 transcription factors, that are highly expressed during early neural development and are crucial to cell fate decisions20,29,30 (Fig. 4b, c, Extended Data Fig. 8g). The expression of these proneural transcription factors paralleled that of BORIS in resistant cells, and was dependent on BORIS-mediated looping, as BORIS depletion led to their downregulation (Extended Data Fig. 8h, i). Moreover, analysis of transcription factor binding sites revealed enrichment of BORIS and several of these proneural transcription factors at the regulatory regions of the highest-expressed genes in resistant cells, whereas sensitive cells were dominated by MYC, MYCN and MAX E-box and E-box-like motifs (Fig. 4d). Similar increased expression of proneural transcription factors with increased BORIS occupancy at their promoters was seen in BORIS-overexpressing E9-resistant SK-N-BE(2) neuroblastoma cells compared with their sensitive counterparts (Extended Data Fig. 8j, k). The high transcriptional activity of these BORIS-regulated genes was also associated with increased binding of the transcriptional activator BRD4, which rendered the resistant cells more sensitive to BET inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 9; Supplementary Note 2). Together, these results indicate the establishment of an alternative transcription factor regulatory network controlled by BORIS-induced chromatin remodelling to support the resistant cell state.

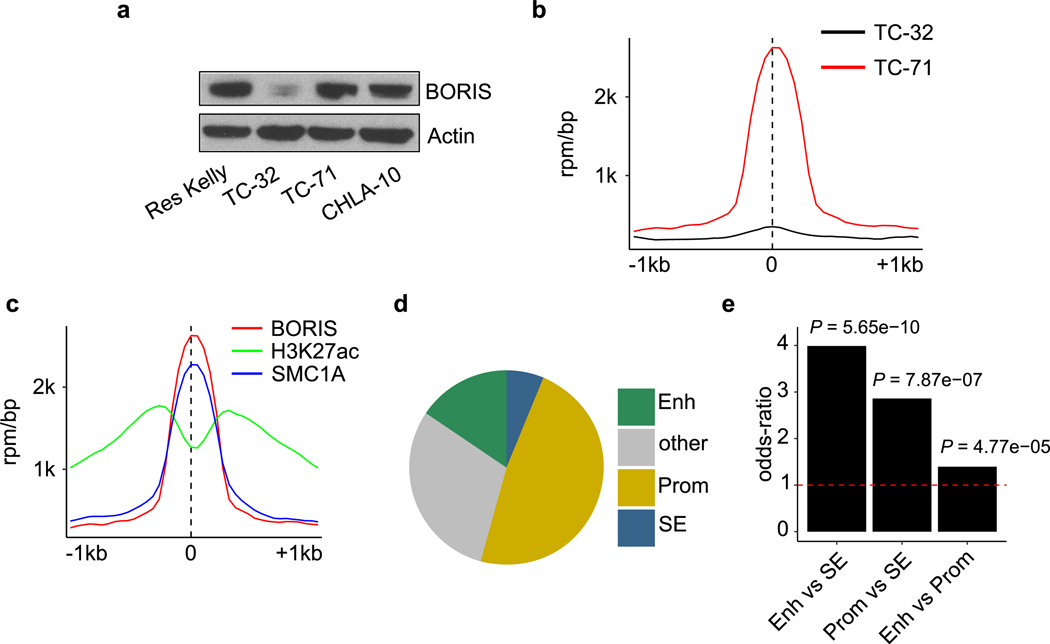

Thus, using a pair of isogenic ALK-inhibitor sensitive and resistant neuroblastoma cell lines, we show that the CTCF paralogue BORIS can promote regulatory DNA interactions that support a phenotypic switch in the context of treatment resistance (Fig. 4e). This mechanism appears relevant to different neuroblastoma cell lines and kinase inhibitors and may extend to other cancers. In Ewing sarcoma, in which overexpression of BORIS is associated with metastasis and relapse (Extended Data Fig. 1c), we observed increased BORIS occupancy at regulatory regions in chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 10; Supplementary Note 3). Further work will establish whether BORIS-mediated alteration of chromatin looping is a general mechanism by which tumour cells co-opt developmental networks to sustain alternative cell states in response to targeted or conventional therapies.

Methods

Cell lines.

Human neuroblastoma cell lines Kelly and SK-N-BE(2) and human Ewing sarcoma cell lines TC-32, TC-71 and CHLA-1031,32 were obtained from the Children’s Oncology Group cell line bank. Human neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-SH and human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cell line authenticity was confirmed by genotyping, and cells were tested negative for mycoplasma contamination every 3 months. All cells except HEK293T were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). Resistant cells were grown in the presence of either the ALK inhibitor, TAE68414 (Kelly and SK-N-SH) or the CDK12 inhibitor, E921 (SK-N-BE(2)).

Compounds.

TAE684 and E9 were synthesized in-house in the Gray laboratory and JQ133 was obtained from J.Qi’s laboratory at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). Ceritinib34, lorlatinib35 and I-BET72636 were purchased from Selleck Chemicals.

Synthetic RNA spike-in and microarray analysis.

Total RNA and sample preparation was performed as previously described37. In brief, cells were either incubated in medium containing DMSO, TAE684 (1 μM) or JQ1 (2.5 μM), or infected with shRNA (Ctrl or BORIS) for 24 h. Cell numbers were determined using a Countess II cell counter (Life Technologies) before lysis and RNA extraction. Biological duplicates (equivalent to 5 × 106 cells per replicate) were collected and homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol Reagent (Ambion), purified using the mirVANA miRNA isolation kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions and re-suspended in 50 μl nuclease-free water (Ambion). Total RNA was spiked-in with ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Ambion), treated with DNA-free DNase I (Ambion) and analysed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) for integrity. RNA with the RNA Integrity Number above 9.8 was hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression arrays (Affymetrix).

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were used: N-MYC (9405), N-MYC (51705), cleaved PARP (9541), cleaved caspase 3 (9661), ALK (3333), AKT (4691), pAKT-T308 (9275), pAKT-S473 (#9271), ERK (4695), pERK (4377), S6 (2217), pS6 (4857), STAT3 (4904), pSTAT3 (9131), ABCB1 (12683), SOX2 (3579), β-actin (4967), CTCF (3417), normal rabbit IgG (2729) and HRP anti-mouse IgG (7076) from Cell Signaling Technology; HRP anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2357) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; BRD4 (A301–985A100) and SMC1A (A300–055A) from Bethyl Laboratories; CTCF (07–729), SOX9 (AB5535) and H3K27me3 (07–449) from Millipore; pALK-Y1507 (ab73996), BORIS (ab187163) and H3K27ac (ab2729) from Abcam; BORIS (NBP2–52405) from NOVUS Biologicals; BORIS (39851) from Active Motif; SIX1 (HPA001893) from Sigma-Aldrich; and Vysis LSI N-MYC (2p24) SpectrumGreen/Vysis CEP 2 SpectrumOrange Probe (07J72–001) from Abbott.

Cell viability and growth curve assays.

Viability and growth experiments were performed using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described38. Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a seeding density of 4 × 103 cells per well. For growth assays, the cells were analysed each day until day 5. For viability, after 24 h, the cells were treated with various concentrations of the indicated drug (ranging from 1 nM to 10 μM except for I-BET726: 2 nM to 20 μM). DMSO without drug served as a negative control. After 72 h of incubation, cells were analysed for cell viability and IC50 values were determined using a nonlinear regression curve fit with GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Cell-cycle analysis.

Cell-cycle analysis was performed 24 h after cell plating using propidium iodide staining, as previously described15. Cells fixed with 80% ethanol overnight at 4 °C were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 mg ml−1 propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) and 0.2 mg ml−1 RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich). After 45 min at 37 °C in the dark, analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cell-cycle profiles were plotted as histograms generated using FlowJo software (FLOWJO).

Western blotting.

Cell or tumour tissue was lysed in NP-40 buffer (Invitrogen) containing a 1× complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche) per 10 ml buffer and a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentration was measured using the DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad); protein (50 μg) was denatured in LDS sample buffer with reducing agent (Invitrogen), separated on precast 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (5% dry milk in TBS with 0.2% Tween-20) for 1 h, and then incubated in the primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Chemiluminescent detection was performed with the appropriate secondary antibodies and developed using Genemate Blue ultra-autoradiography film (VWR). The actin loading controls for the protein samples shown in the immunoblots of the following panels (two independent mouse tumour samples, and cell lines representative of two independent experiments) are the same because the samples were run on a single gel but probed for pALK, ALK (Extended Data Fig. 2a), MYCN (Extended Data Fig. 3e) and BORIS (Extended Data Fig. 4a), respectively.

Co-immunoprecipitation.

Cells were collected in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-100, 1 mM PMSF), containing a 1× complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche) per 10 ml buffer and a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Homogenates were centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain supernatants. DNase I (approximately 1 U ml−1) was used to degrade DNA in supernatants by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenously expressed proteins was performed using protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, antibody-conjugated Dynabeads were incubated with purified cell lysates to immunoprecipitate the target antigen. Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were CTCF (3417, Cell Signaling Technology) and BORIS (NBP2–52405, NOVUS Biologicals). The elution step was conducted by heating the beads for 10 min at 95 °C in lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer with reducing agent (Invitrogen), after which western blotting was performed using the following antibodies: CTCF (3417, Cell Signaling Technology) and BORIS (9851, Active Motif).

Plasmids, shRNA knockdown and overexpression systems.

pLKO.1 shRNA constructs (control: SHC007; MYCN: 1-TRCN0000020694 and 2-TRCN0000363425; BORIS: 3-TRCN0000370229 and 4-TRCN0000365141; BRD4: A-TRCN0000318771 and B-TRCN0000196576) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and pLKO.1 GFP shRNA was a gift from D. Sabatini (Addgene plasmid 30323)39. Overexpression constructs were generated by cloning BORIS cDNA into the Tet-inducible pInducer20 vector, provided by S. Elledge (Addgene plasmid 44012)40. Production of lentiviral particles and subsequent infection were performed as previously described38. The lentivirus was packaged by co-transfection of either pLKO.1 or pInducer20 plasmid with the helper plasmids, pCMV-deltaR8.91 and pMD2.G-VSV-G into HEK293T cells using TransIT-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio LLC). Virus-containing supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection. Cells were infected with 8 μg ml−1 polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) and 24–48 h later selected with puromycin (pLKO.1) (Sigma-Aldrich) and then collected at appropriate time points. When using the Tet-inducible system for BORIS overexpression, induction of gene expression was achieved by treating cells every 2–3 days with doxycycline (0.2 μg ml−1) for a total duration of 37 days.

qRT–PCR.

RNA isolation and PCR amplification were performed as previously described38, except that the RT–PCR was performed using the SuperScript III First-Strand system (Life Technologies). Total RNA was isolated from cell lines with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). One microgram of purified RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III First-Strand (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green on a Viia7 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All experiments were performed in biological triplicates unless stated otherwise. Each individual biological sample was amplified by qPCR in technical replicates and normalized to actin as an internal control. Amplification was carried out with primers specific to the genes to be quantified (sequences available on request).

Sequence analysis.

The kinase domain of ALK was amplified from cDNA extracted from sensitive and resistant cells using the HotStar HiFidelity Polymerase Kit (Qiagen). The PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and confirmed by sequencing.

RTK array.

The Human Phospho-RTK Array Kit (R&D Systems) was used as previously described38. Cell lysate (500 μg) was incubated on a phospho-RTK membrane array (ARY001B) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Target proteins were captured with their respective antibodies. After washing, the proteins were incubated with a phosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase to allow the detection of captured phosphorylated RTKs.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses were performed using a Vysis LSI N-MYC (2p24) SpectrumGreen/Vysis CEP 2 SpectrumOrange Probe (Vysis), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry.

All human tumour specimens (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded slides) were obtained under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol of the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Staining was performed by Applied Pathology Systems using the ImmPRESS Excel Amplified HRP Polymer Staining Kit (MP-7601, Vector Laboratories) on a Dako Autostainer (Agilent Technologies). Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate-based buffer on a steamer for 25 min. Slides were blocked with BLOXALL blocking solution and 2.5% horse serum sequentially before a 1-h incubation with BORIS antibody at 1:50 dilution (ab187163, Abcam). Sections were then incubated with anti-rabbit amplifier antibody and ImmPRESS Excel Amplified HRP Polymer Reagent sequentially before incubation with ImmPACT DAB EqV Substrate. Finally, slides were counterstained with haematoxylin, followed by dehydration and the addition of coverslips.

Bisulfite sequencing.

Methylation analysis of BORIS (NCBI RefSeq NC_000020.11, spanning nucleotides chr20: 57,524,203–57,525,234 on GRCh38.p7 assembly) was performed using a bisulfite sequencing assay. Genomic DNA (500 ng) was treated with the EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research), followed by PCR using ZymoTaq Polymerase premix (Zymo Research) and specific primers designed using the Zymo bisulfite primer seeker (http://www.zymoresearch.com/tools/bisulfite-primer-seeker/; sequences available on request). PCR products were then sequenced for the assessment of CpG site-specific DNA methylation in the BORIS promoter region.

Growth assay.

After shRNA-mediated knockdown of BORIS, cells were reseeded at a density of 4 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. At 48 and 120 h of incubation, cells were stained with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) and counted on a Countess II cell counter (Life Technologies).

Mouse experiments.

All mouse experiments were performed with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the DFCI. Three mouse experiments were performed: (i) to assess the tumorigenic potential of resistant cells in vivo; (ii) to assess that resistance to TAE684 was maintained in vivo; and (iii) to assess the effect of JQ1 on resistant cells in vivo. All experiments were performed using subcutaneous cell xenograft models generated by injecting 2 × 106 sensitive or resistant Kelly neuroblastoma cells into the flanks of NU/NU (Crl:NU-Foxn1nu) (Charles River Laboratories) or NU/NU (CrTac:NCr-Foxn1nu) (Taconic) 7-week-old female mice. Mice were randomized into groups of equal average volumes, and investigators were not blinded to group allocation during data collection. (i) To assess the tumorigenic potential of resistant cells in absence of treatment, mice with established disease (mean tumour volume of 200 mm3) were monitored for up to 23 days (n = 4 per group). Tumours were obtained, dissociated and used to establish cell lines and for assessment of mRNA levels, protein expression and sensitivity to TAE684. (ii) To ensure that the in vitro resistance to TAE684 was maintained in vivo, mice with established disease were divided into two cohorts and were treated with either TAE684 (10 mg kg−1) or vehicle control by oral gavage once daily (n = 8 per group), and were monitored for up to 56 days from start of treatment. (iii) To assess the sensitivity of resistant cells to BRD4 inhibition, mice with established disease were divided into two cohorts and treated with either JQ1 (50 mg kg−1) or vehicle control intraperitoneally (i.p.) once daily (n = 6 per group), and were monitored for up to 87 days from start of treatment. For all experiments, disease burden was quantified using electronic caliper measurements (2–3 times a week) and mouse weights were monitored at least twice a week. Tumour volumes were calculated using the modified ellipsoid formula41: ½(length × width2). Animals were euthanized when tumour volumes reached 1,500–2,000 mm3 based on institutional IACUC criteria for maximum tumour volumes. In none of the experiments were the institutional limits for tumour volumes (<2,000 mm3 measurement preceding the day of euthanization) exceeded.

ChIP–seq.

ChIP was carried out as previously described15 with minor changes as described. Approximately 1 × 107 cells were crosslinked for 10 min at room temperature with 1% formaldehyde (Thermo Scientific) in PBS followed by quenching with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. The cells were then washed twice in ice-cold PBS, and the cell pellets flash frozen and stored at −80 °C. Fifty microlitres of protein G Dynabeads per sample (Invitrogen) were blocked with 0.02% Tween20 (w/v) in PBS. Magnetic beads were loaded with 10 μg each of antibody and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Crosslinked cells were lysed, placed in sonication buffer with 0.2% SDS, placed on ice and chromatin was sheared using a Misonix 3000 sonicator (Misonix) at the following settings: 10 cycles, each for 30 s on, followed by 1 min off, at a power of approximately 20 W. The lysates were then centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatants collected and diluted with an equal amount of sonication buffer to reach a final concentration of 0.1% SDS. The sonicated lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the antibody-bound magnetic beads, washed with low-salt buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 140 mM NaCl and 1× complete protease inhibitor), high-salt buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl and 1× complete protease inhibitor), LiCl buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM LiCl and 1× complete protease inhibitor) and Tris-EDTA buffer. DNA was then eluted in elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS), and high-speed centrifugation was performed to pellet the magnetic beads and collect the supernatants. The crosslinking was reversed overnight at 65 °C. RNA and protein were digested using RNase A and proteinase K, respectively, and DNA was purified with phenol chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Purified ChIP DNA was used to prepare Illumina multiplexed sequencing libraries using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep kit and the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries with distinct indexes were multiplexed and run together on the Illumina NextSeq 500 (SY-415–1001, Illumina) for 75 bases in single-read mode.

HiChIP.

HiChIP was performed as previously described24 with a few modifications. Approximately 1 × 107 cells were crosslinked for 10 min at room temperature with 1% formaldehyde in growth medium and quenched in 0.125 M glycine. After washing twice with ice-cold PBS, the supernatant was aspirated and the cell pellet flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crosslinked cell pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold Hi-C lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40 and 1× complete protease inhibitor) and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min with rotation. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 4 °C and washed once with 500 μl of ice-cold Hi-C lysis buffer. After removing the supernatant, nuclei were resuspended in 100 μl of 0.5% SDS and incubated at 62 °C for 10 min. SDS was quenched by adding 335 μl of 1.5% Triton X-100 and incubating for 15 min at 37 °C. After the addition of 50 μl of 10× NEB Buffer 2 (New England Biolabs, B7002) and 375 U of MboI restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, R0147), chromatin was digested at 37 °C for 2 h with rotation. After digestion, MboI enzyme was heat-inactivated by incubating the nuclei at 62 °C for 20 min. To fill in the restriction fragment overhangs and mark the DNA ends with biotin, 52 μl of fill-in master mix, containing 37.5 μl of 0.4 mM biotin-dATP (Invitrogen, 19524016), 1.5 μl of 10 mM dCTP (Invitrogen, 18253013), 1.5 μl of 10 mM dGTP (Invitrogen, 18254011), 1.5 μl of 10 mM dTTP (Invitrogen, 18255018), and 10 μl of 5 U μl−1 DNA Polymerase I, Large (Klenow) Fragment (New England Biolabs, M0210), were added and the tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with rotation. Proximity ligation was performed by the addition of 948 μl of ligation master mix, containing 150 μl of 10× NEB T4 DNA ligase buffer (New England Biolabs, B0202), 125 μl of 10% Triton X-100, 7.5 μl of 20 mg ml−1 BSA (New England Biolabs, B9000), 10 μl of 400 U μl−1 T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, M0202), and 655.5 μl of water, and incubation at room temperature for 4 h with rotation. After proximity ligation, nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min and resuspended in 1 ml of ChIP sonication buffer (50 mM HEPESKOH (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and 1× complete protease inhibitor). Nuclei were sonicated using a Misonix 3000 sonicator (Misonix) at the following settings: 12 cycles, each for 30 s on, followed by 1 min off, at a power of approximately 20 W. Sonicated chromatin was clarified by centrifugation for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was transferred to a tube. Sixty microlitres of protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were washed three times and resuspended in 50 μl sonication buffer. Washed beads were then added to the sonicated chromatin and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were then separated on a magnetic stand and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Seventy-five microlitres of protein G Dynabeads pre-incubated overnight at 4 °C with 10 μg of anti-SMC1A antibody (Bethyl A300–055A) or 10 μg of BORIS antibody (Abcam, ab187163) were added to the tube and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were then separated on a magnetic stand and washed twice with 1 ml of sonication buffer, followed by once with 1 ml high-salt sonication buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), once with 1 ml of LiCl wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) and once with 1 ml of TE buffer with salt (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl). Beads were then resuspended in 200 μl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% SDS) and incubated at 65 °C for 15 min. To purify the eluted DNA, RNA was degraded by the addition of 8.5 μl of 10 mg ml−1 RNase A and incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. Protein was degraded by the addition of 20 μl of 10 mg ml−1 proteinase K and incubation at 55 °C for 45 min. Samples were then incubated at 65 °C overnight to reverse crosslink protein–DNA complexes. DNA was then purified using Zymo ChIP DNA Clean and Concentrator columns (Zymo, D5205) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and eluted in 14 μl water. The amount of eluted DNA was quantified by Qubit dsDNA HS kit (Invitrogen, Q32854). Tagmentation of ChIP DNA was performed using the Illumina Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, FC-121–1030). First, 5 μl of MyOne Streptavidin C1 Dynabeads (Invitrogen, 65001) was washed with 1 ml of Tween wash buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) and resuspended in 10 μl of 2× biotin binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 2 M NaCl). Then, 25 ng of purified DNA was added in a total volume of 10 μl water to the beads and incubated at room temperature for 15 min with agitation every 5 min. After capture, beads were separated with a magnet and the supernatant was discarded. Beads were then washed twice with 500 μl of Tween wash buffer, incubating at 55 °C for 2 min with shaking for each wash. Beads were resuspended in 25 μl of Nextera Tagment DNA buffer. To tagment the captured DNA, 1 μl of Nextera Tagment DNA Enzyme 1 was added with 24 μl of Nextera Resuspension Buffer and samples were incubated at 55 °C for 10 min with shaking. Beads were separated on a magnet and supernatant was discarded. Beads were washed twice with 500 μl of 50 mM EDTA at 50 °C for 30 min, washed twice with 500 μl of Tween wash buffer at 55 °C for 2 min each, and finally washed once with 500 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 1 min at room temperature. Beads were separated on a magnet and supernatant was discarded. To generate the sequencing library, PCR amplification of the tagmented DNA was performed while the DNA was still bound to the beads. Beads were resuspended in 15 μl of Nextera PCR Master Mix, 5 μl of Nextera PCR Primer Cocktail, 5 μl of Nextera Index Primer 1, 5 μl of Nextera Index Primer 2 and 20 μl water. DNA was amplified with 9–10 cycles of PCR. After PCR, beads were separated on a magnet and the supernatant containing the PCR-amplified library was transferred to a new tube, purified using Zymo DNA Clean and Concentrator columns (Zymo, D5205) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and eluted in 14 μl water. Purified HiChIP libraries were size-selected to 300–700 bp using a Sage Science Pippin Prep instrument according to the manufacturer’s protocol and subjected to 2 × 100 paired-end sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system (SY–401–2501, Illumina).

scRNA-seq.

Kelly cells (sensitive, intermediate and resistant states) were grown to 70% confluence in T75 culture flasks. In brief, growth medium was aspirated and cells were treated with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA for 3 min at 37 °C, after which cells were washed twice with 1× PBS. Cells were then resuspended into single cells at a concentration of 1 × 106 per ml in 1× PBS with 0.4% BSA for 10x Genomics processing. The sorted cell suspensions were loaded onto a 10x Genomics Chromium instrument to generate single-cell gel beads in emulsion (GEMs). Approximately 5,000 cells were loaded per channel. scRNA-seq libraries were prepared using the following Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits: Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library & Gel Bead Kit v2 (PN-120237), Single Cell 3′ Chip Kit v2 (PN-120236) and i7 Multiplex Kit (PN-120262) (10x Genomics) as previously described42, and following the Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v2 User Guide (Manual Part CG00052 Rev A). Libraries were run on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 system (SY-401–4001, Illumina) as 2 × 150 pairedend reads, one full lane per sample, for approximately >90% sequencing saturation.

Genomics analysis: direct comparison of CTCF and BORIS expression in healthy and tumour samples.

To assess the expression levels and range of BORIS and CTCF in healthy and tumour cells all GTEx, TCGA and TARGET datasets were downloaded and converted to FPKM values and displayed as [log2(FPKM + 1)] (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b).

Association of BORIS with prognostic features.

For each dataset, processed values were extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and scaled values were created by normalizing the expression levels by the minimum mean value of the conditions that were compared, Esi,j = Ei,j/min(average(Ej)). The two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test on the original values was used to determine statistical differences between the compared conditions (Extended Data Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 4f).

Microarray data analysis.

Microarray data were analysed using a custom CDF file (GPL16043) that contained the mapping information of the ERCC probes used in the spike-in RNAs. The arrays were normalized as previously described37. In brief, all microarray chip data were imported in R (https://www.r-project.org/, v.3.1.3) using the affy package43 (v.1.44.0), converted into expression values using the expresso command, normalized to take into account the different numbers of cells and spike-ins used in the different experiments and renormalized using loess regression fitted to the spike-in probes. Sets of differentially expressed genes were obtained using the limma package44 (v.3.22.7) and a FDR value of 0.05. Spike-in normalized absolute expression values (counts) were normalized to CPM as a measurement of relative gene expression concentrations per condition. Total number of transcripts per sample was determined as the total number of counts after spike-in normalization and the BORIS shRNA sample was first normalized to the control shRNA sample to account for technical effects that originated from the transfection protocol.

ChIP–seq analysis.

For all ChIP–seq samples, high-quality data were confirmed using the Fastqc tool (v.0.11.5) and samples were aligned to the human genome (build hg19, GRCh37.75) with STAR (v.2.5.1b_modified) and the parameters ‘– alignIntronMax 1–alignEndsType EndToEnd–outFilterMultimapNmax 1–outFilterMismatchMax 5’. Next, non-duplicate reads that mapped to the reference chromosomes were retained using Samtools (v.1.3.1) and MarkDuplicates (v.2.1.1) from Picard tools. For each experimental replicate, antibody enrichment was assessed using the plotFingerprint command from deepTools (v.2.2.4). Peaks were identified with MACS2 (v.2.1.1) for narrow peaks (BORIS, CTCF, BRD4, Pol2, MYCN) with the parameters ‘–q 0.01–call-summits’ and for broad peaks (H3K27ac, H3K27me3) with the parameters ‘–broad-cutoff 0.01’. Peaks overlapping regions with known artefact regions (http://mitra.stanford.edu/kundaje/akundaje/release/blacklists/) were blacklisted out. Input normalized bedgraph tracks were created with the deepTools command bamCompare and the parameters ‘–scaleFactorsMethod=readCount–ratio=subtract–binSize=50–numberOfProcessors=4–extendReads=200’. Subsequently, negative values were set to zero and counts were scaled to RPM per bp to account for differences in library size. Bigwig files were created with bedGraphToBigWig (v.4). ChIP–seq replicates (n = 2) were merged at the BAM level after assessment of strong correlation with the deepTools command ‘multiBigwigSummary BED-file’ using all replicate bigwigs and identified peaks as input. Identification of peaks and generation of tracks were then repeated for these merged files and used for further analyses. Downstream analyses for ChIP–seq and other genomic interval data was performed in R (https://www.r-project.org/) (v.3.5.1) using the data.table (v.1.12.2) package.

Gencode annotation and isoform selection.

Gencode (http://www.gencodegenes.org/, release 19) annotation was used and for each gene the most likely isoform was selected based on data-driven criteria. In brief, only genes that were part of the Refseq transcriptome annotation and with a minimum length of 1 kb were considered. Next, isoforms were prioritized according to increased deposition of Pol2 and H3K27ac reads on the TSS, transcript length and alphabet rank, in that order, until only one transcript was selected for each gene.

Cell-type-specific binding patterns.

To determine the cell specificities of BORIS and CTCF peaks, we first combined all peaks identified by MACS2 and merged the peak regions that overlapped by at least 50%. A 50% threshold was empirically selected to avoid merging peaks that had clear and distinct summits. Next, normalized BORIS or CTCF read densities were calculated for each region and a ratio [log2(resistant/sensitive)] was calculated. Peak regions with a twofold density increase or decrease were classified as resistant or sensitive cell-specific peaks, respectively, whereas other regions were denoted as ‘shared’ to indicate that these peaks had similar BORIS or CTCF deposition in both cell types (Fig. 2a, b and Extended Data Fig. 6a). To explore the proximity of BORIS and CTCF peaks and how they were altered during the transition from sensitive to resistant cells, we overlapped all shared and cell-type-specific peaks from both cell types in the least stringent way (minimum 1-bp overlap) (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 6a).

Genomic enrichment of peak-binding sites.

To identify genomic locations with BORIS or CTCF binding we determined the number of peaks that overlapped with at least 25% of known functional regions in the following order: (i) broad promoter (±2 kb TSS); (ii) BRD4+ H3K27ac+ (active) enhancers; (iii) BRD4− H3K27ac+ enhancers; (iv) exons; (v) introns; (vi) repressed chromatin represented by H3K27me3 broad peaks; or (vii) other (if the peak was outside the aforementioned regions) (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Enrichment of ChIP–seq binding at resistant cell BORIS peaks was performed by extending BORIS summits by 1 kb in both directions and calculating the normalized read densities in 50-bp bins (Fig. 2d).

Genomic enrichment of regulatory regions.

To visualize the enrichment of CTCF and BORIS at regulatory regions (enhancers and promoters) and the differences between sensitive and resistant cells, a metagene analysis for CTCF and BORIS occupancies was performed for all H3K27ac enhancer regions and gene promoters. All TSSs were extended in both directions by 2 kb and binned in 50-bp bins, and each enhancer (start–end) was divided into 40 equally sized bins and extended with 2 kb in both directions and these extended regions were binned in 50-bp bins. Normalized bedgraph files were used to calculate read density (RPM per bp). An aggregated summary profile was created for each cell type. To account for different numbers of identified enhancers in both cells types we calculated a normalization factor (N resistant enhancers/N sensitive enhancers) to divide each aggregated read density (Extended Data Fig. 6e).

HiChIP processing and quality control.

For all SMC1A-based HiChIP datasets, raw reads were first trimmed to a uniform length of 50 bp using trimmomatic45(v.0.36) and were then processed using the HiC-Pro (v.2.10.0) pipeline46 with default settings for the human genome (build hg19, GRCh37.75) and corresponding MboI cut sites. To perform intra- and inter-correlation analysis for biological replicates, forward and reverse reads from the HiC-Pro output were merged together to generate one-dimensional SMC1A BAM profiles. Genome-wide Spearman correlation in 5-kb bins was computed for all merged genomic anchor regions on those merged BAMs for all replicates using the ‘multiBamSummary BED-file’ command from deepTools (Extended Data Fig. 7a, e).

HiChIP loop calling and differential looping analysis.

Loops were directly called from the HiC-Pro output using hichipper47 (v.0.7.3), with parameter ‘peaks = combined, all’, and subsequently diffloop47 (v.1.10.0) with default settings. Only loops that were detected in all three biological replicates of a sample (sensitive, resistant, shCtrl or shBORIS) with a minimum of five paired-end tags in total and an FDR ≤ 0.01 were retained for further analysis. To call differential loops between samples, the quickAssocVoom function was used and significantly different loops were either considered reinforced (mango.FDR < 0.01 and log2-transformed fold change > 1) or lost (mango.FDR < 0.01 and log2-transformed fold change < −1).

Classification of HiChIP interactions.

SMC1A-based HiChIP interactions (loops) were classified as previously described48 with minor adaptations. Associated anchors of loops were overlapped with our ChIP-seq peaks (CTCF, BORIS, H3K27ac, BRD4) and promoter regions (TSS ± 2 kb), requiring a minimum 1-bp overlap. Each anchor was then independently classified according to its overlap profile, following a hierarchical tree. If an anchor overlapped a promoter, an enhancer (BRD4 + H3K27ac), or a CTCF peak, it was classified as promoter-, enhancer- or CTCF-anchor, in that order. If there was no overlap, the anchor was considered ‘other’. By combining these four anchor classes we discriminated 10 different interaction classes. We excluded from further analyses any interaction that contained an anchor classified as other, which also represented on average much shorter interactions (data not shown), and which were hence more likely to have occurred due to linear proximity on the DNA. This resulted in the identification of 6 main interaction classes (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Association of BORIS with lost loops.

Only loops that were detected in both the original (sensitive versus resistant) and BORIS depletion (shBORIS versus shCtrl) samples were used for this analysis. First, loops were divided into lost and retained loops upon BORIS depletion, and an odds ratio (two-sided Fisher’s exact test) was calculated for the initial presence of BORIS binding on the anchors of these two groups (Fig. 3f). An analogous strategy was followed after first stratifying loops according to the different identified loop classes (Extended Data Fig. 7f, g).

Identification of super-enhancer regions.

Super-enhancers were identified using the ROSE algorithm (v.1) (https://bitbucket.org/young_computation/rose). In short, H3K27ac enriched regions were identified with MACS2 and termed typical enhancers. These regions were stitched together if they were within 12.5 kb of each other. Stitched regions were ranked by H3K27ac signal therein and the inclination point at which the two classes of enhancers separated was determined by ROSE. Stitched enhancers above this threshold were considered super-enhancers and the others, typical enhancers. To compare different samples, we used the same maximum threshold between the conditions considered (Extended Data Fig. 8a).

Identification of cell-type-specific super-enhancers.

Cell-type-specific and active super-enhancers were identified by merging both sensitive- and resistant-cell super-enhancers and determining cell-type specificity based on the differential normalized read density of both H3K27ac and BRD4. In brief, ratios [log2 (resistant/sensitive)] were calculated for H3K27ac and BRD4. A combined threshold of 2.5 was required to identify a cell-type-specific super-enhancer with at least a minimum 0.75 change for each individual mark. Super-enhancers that did not meet these criteria were classed as shared (neutral) between cell types (Extended Data Fig. 8b).

Correlation analysis of looping with gene expression and enhancer landscape.

Regulatory interactions were associated to target genes and super-enhancers based on proximity to the TSS and minimal overlap (1 bp) with its anchors, respectively (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8f).

Chromatin-based gene classification.

Genes were classified as having an ‘open’, ‘neutral’ or ‘closed’ chromatin state based on unsupervised clustering of a metagene representation of ChIP–seq occupancy of H3K27ac and H3K27me3. Each gene (from TSS to TES, and 2 kb up- and downstream of this region) was divided into 20 equally sized bins; the extended regions were binned in regions of 50 bp. Normalized bedgraph files were used to calculate read density (RPM per bp) and k-means clustering was applied to group each extended gene region in one of three clusters (Extended Data Fig. 8d, e). An aggregated summary profile was created for each group of genes. The open and closed clusters were classified based on predominantly H3K27ac and H3K27me3 accumulation, respectively, and the ‘neutral’ cluster displayed on average equal levels of both.

Integrated genomic data analysis.

An ensemble analysis was performed to identify the set of genes that showed characteristics of reactivation in resistant cells. For each gene, five features were examined: (i) creation of a unique regulatory interaction; (ii) deposition of BORIS on its promoter or looped enhancer; (iii) association with a resistant cell-specific super-enhancer through overlap with either its promoter or looped anchor; (iv) increased mRNA expression; and (v) transition from a closed or neutral state to an open chromatin state. A unique set of 89 genes (Supplementary Table) that exhibited four out of five features were identified as the top reactivated genes in resistant cells. Within these 89 genes, 13 were identified as transcription factors by the TcoF database (http://www.cbrc.kaust.edu.sa/tcof/) (Fig. 4b).

Allen Brain atlas gene signature.

Expression data and metadata for human brain development were downloaded from the Allen Brain atlas (http://www.brainspan.org). Row-normalized z-scores of [log2(RPKM + 1)] values were used to create a heat map. Values greater than 3.5 were set to 3.5 to reduce the effect of extreme outliers on the visualization. Samples were ordered according to developmental time points (Extended Data Fig. 8g).

BORIS and BRD4 correlation at promoter regions.

BORIS and BRD4 colocalization and correlation were assessed for the promoter regions of the 89 top-ranked genes. The TSS was extended in both directions by 2 kb and binned in 100-bp regions. Normalized read densities for BORIS and BRD4 were calculated and a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient calculated for sensitive and resistant cells. An aggregated density plot of all 89 genes was created to visualize the increased deposition and correlation of BRD4 and BORIS in resistant cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a).

Gene expression and DNA-binding analysis.

To examine the association between gene expression and overlapping targets of MYCN and BORIS in sensitive and resistant cells, respectively, the percentage of gene promoters (±2 kb TSS) that overlapped with ChIP–seq peaks in 10 equally sized bins based on the expression distribution was calculated (Extended Data Fig. 6f). To visualize and correlate gene expression with DNA binding of MYCN or BORIS, genes were ranked based on expression and plotted against the total rescaled (0–100) binding intensities calculated for each gene promoter (±2 kb TSS). For each ChIP–seq mark a loess regression curve was computed using a span of 0.1 (Extended Data Fig. 6g).

Transcription factor motif enrichment analysis.

Statistically overrepresented motifs were identified with HOMER49 (v.2) using the command findMotifs.pl providing both target and background fasta sequences for regions of interest. For promoter regions we selected the top 1,000 up- and downregulated genes in resistant cells and extended the TSS of each gene by 2 kb in both directions. The genomic coordinates were used to extract fasta sequences with the Biostrings package (v.2.50.1) in R and used as target or background to identify motifs associated with promoter regions of genes within each cell type. A similar strategy was followed to identify overrepresented motifs associated with cell-type-specific super-enhancers. Target and background fasta sequences were extracted from the summits of BRD4 peaks located on cell-type-specific super-enhancers and extended by 500 bp in both directions. For a selection of enriched sequences, the associated transcription factor motif and significance level (P) was visualized using a heat map (Fig. 4d).

scRNA-seq analysis.

The Cell Ranger Single Cell Software Suite, v.1.3 was used to perform sample de-multiplexing, barcode and unique molecular identifier (UMI) processing, and single-cell 3′ gene counting. A detailed description of the pipeline and specific instructions to run it can be found at: https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger. A high-quality gene expression matrix was created in sequential preprocessing steps. First UMI-based counts were converted to relative expression concentrations by rescaling each cell to a library size of 10,000. Genes were considered detected if rescaled count > log2(0.1 + 1) and retained for further analysis if present in at least 0.5% of the cells from the sample with the lowest cell count. Cells were removed if fewer than 1,000 genes were detected. To remove low-quality cells, we calculated five technical indicators (ratio of detected genes/UMI, percentage of mitochondrial genes, percentage of ribosomal genes, average GC content of library and library complexity measured by Shannon Entropy) and performed PCA on indicators with a coefficient of variation > 5%. Next, density-based clustering was performed on the first and second principal component using an epsilon determined by a k-nearest neighbour plot. All cells that were located outside the main cluster were considered low quality and removed from further analysis. Next, we used the R package ‘scater’ (v.1.10.0) to confirm that there were no technical or experimental confounding effects and the R package ‘Seurat’ (v.2.3.4) to analyse and visualize the data. In brief, UMI counts were log-normalized with a scale factor of 10,000 and subsequently centre-scaled. To visualize cells in a reduced dimensionality, PCA was performed on the most variable genes, which were identified as genes with higher-than-expected variability in consecutive ranked expression bins. Higher complexity clustering was performed with t-SNE using the first 10 principal components, which were deemed most informative based on heat map and elbow plot observation. To identify homogeneous subpopulations, we performed iterative clustering using the network-based clustering algorithm (shared nearest neighbour) with different resolutions as input until each sample was at least separated in two groups. A simple pseudotime analysis was performed by calculating an average expression profile for each identified subpopulation and ordering them according to the summarized expression of transcription factors that displayed variable expression between sensitive and intermediate or intermediate and resistant cells. Variable expression was defined as showing at least a 33% change in the rank of expression between two samples with a minimal normalized expression level > 0.2. For each sample comparison, at least the top 10 most variable transcription factors were included. In total this resulted in 32 transcription factors. Gene expression values were then linearly rescaled between 0 and 10 to jointly visualize relative expression changes during this pseudotime. To examine co-detection or mutual exclusivity between genes of interest, a two-sided Fisher’s exact test was performed for all cells in a given sample. A score combining both the odds ratio and the –log10(P value) was calculated to visualize both the strength and direction between genes in pairwise co-expression tests.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis for each plot is listed in the figure legend and/or in the corresponding Methods. In brief, all grouped data are presented as mean ± s.d. unless stated otherwise. All box and whisker plots of expression data are presented as: centre lines, medians; box limits, twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles; whiskers, minima and maxima (1.5× the interquartile range). Statistical significance for pairwise comparisons was determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test or two-sided unpaired t-test, unless stated otherwise. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between groups calculated by the two-sided log-rank test and the Bonferroni correction method. Tumour volume comparisons for the xenograft studies were analysed by Mann–Whitney U test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Statistical comparisons of distributions of fold changes for the expression microarrays were done using the Mann–Whitney U test. All quantitative analyses are expressed as the mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates, unless stated otherwise. Microarray and ChIP–seq data are based on at least two independent experiments. For all experiments, no statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Unless stated otherwise, experiments were not randomized and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Track visualizations.

Peaks, (super-) enhancers and HiChIP interactions were visualized with a custom build tool (github.com/RubD/GeTrackViz2) or with the circlize package (v.0.4.5) in R.

Retrospective analysis of gene expression in human samples.

Gene expression levels or correlations across primary tumours, healthy tissues or experimental data and patient survival were determined through analysis of the TCGA and TARGET (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/), GTEx (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/), R2 (https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi), Allen Brain atlas (http://www.brain-map.org/) and selected datasets representing distinct tumour types with poor prognosis feature annotations (GSE49710 (Neuroblastoma)50, GSE17679 (Mixed Ewing Sarcoma)51, GSE63074 (Non-small cell lung carcinoma)52, GSE15709 (ovarian cancer)53, GSE16179 (breast cancer)54 and GSE7181 (Glioblastoma)55).

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Extended Data

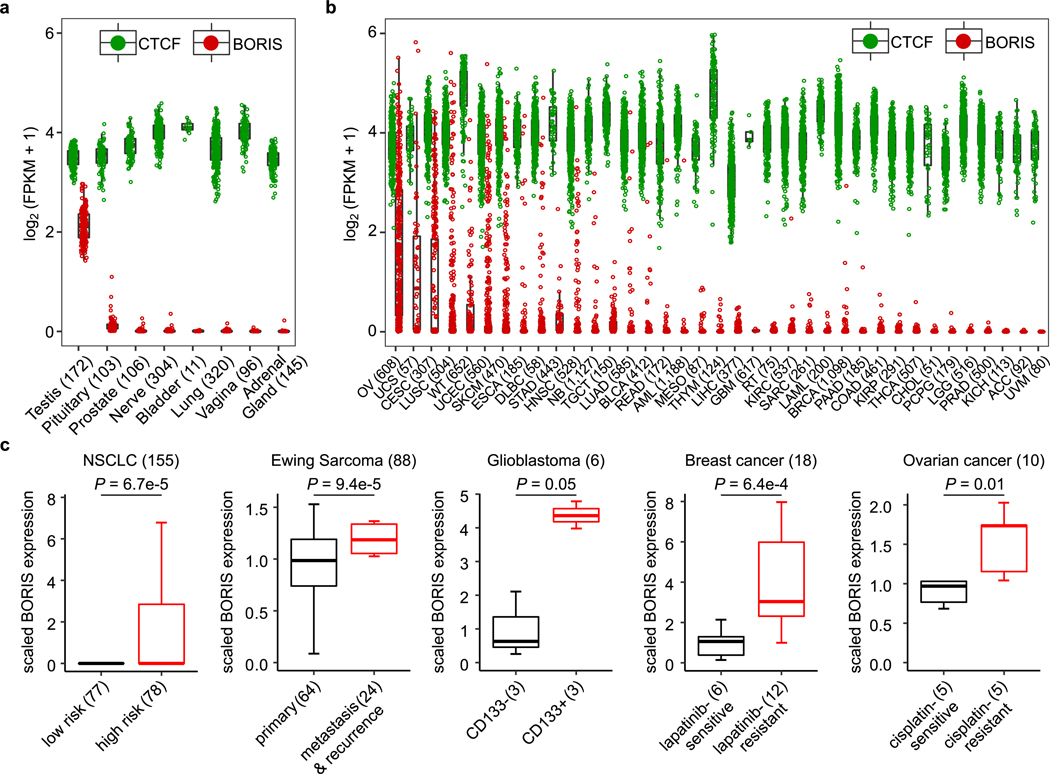

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. BORIS is expressed in several cancers and associated with high-risk features.

a, b, Relative mRNA expression [log2(FPKM + 1)] of CTCF and BORIS in normal tissues (a) and in various cancer types based on TCGA datasets (b). FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. Keys to cancer types: ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; DLBC, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ESCA, oesophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LGG, low-grade glioma; KICH, kidney chromophobe; KIRC, renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LAML, acute myeloid leukaemia; LIHC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MESO, mesothelioma; NB, neuroblastoma; OV, serous ovarian cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PCPG, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; RT, rhabdoid tumour; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumour; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; THYM, thymoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma; UVM, uveal melanoma; WT, Wilms tumour. c, Box plots showing the correlation of BORIS expression with risk status, tumour stage (primary versus metastasis/recurrence), presence of cancer stem cells (CD133 positivity) and response to targeted (lapatinib) or cytotoxic (cisplatin) therapy in the tumour types depicted. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer. Datasets (Mixed Ewing Sarcoma-Savola-117 and NSCLCPlamadeala-410) were extracted from the R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl). GSE7181 (glioblastoma); GSE16179 (breast cancer); GSE15372 (ovarian cancer). P values determined by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For all panels, sample sizes (n) are depicted in parenthesis and box plots are as defined in Fig. 4.

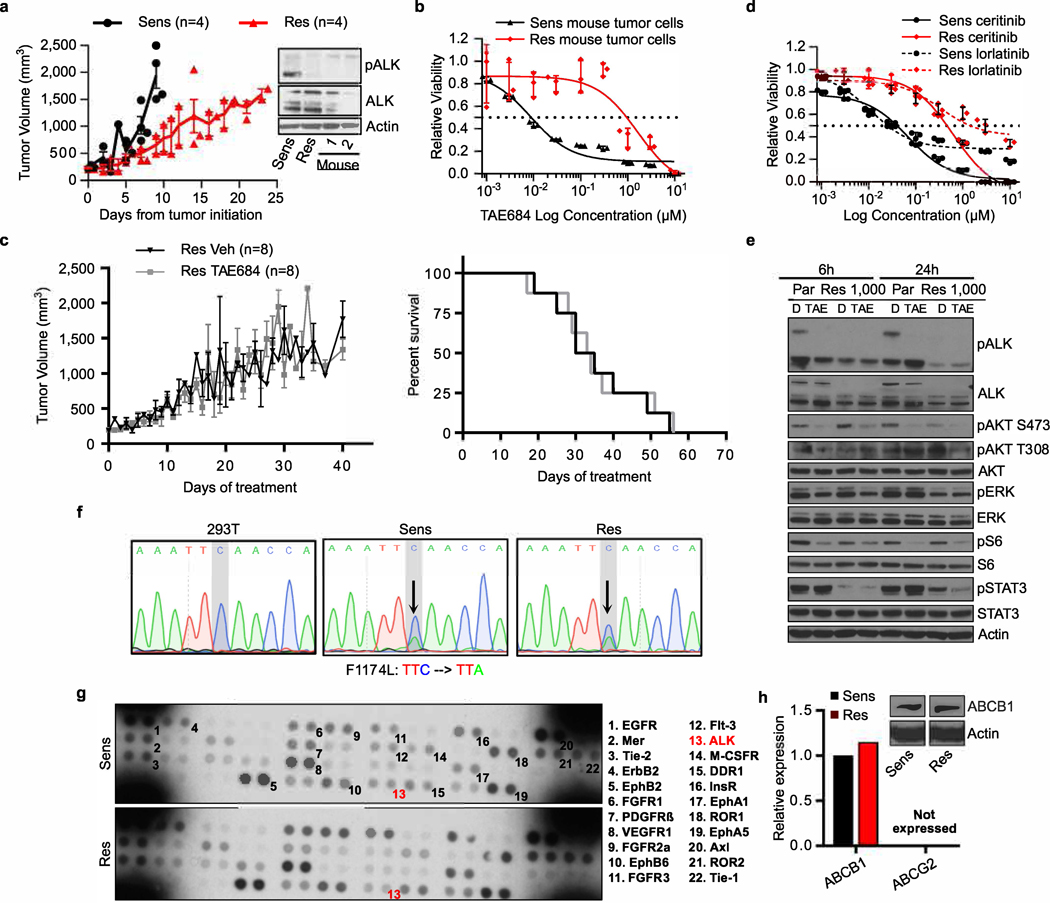

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. ALK inhibitor-resistant cells exhibit stable resistance in vivo and no longer rely on ALK signalling.

a, Left, tumour volumes of sensitive and resistant cell xenografts in untreated NU/NU (Crl:NU-Foxn1nu) mice established by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 cells into both flanks. Animals were euthanized when tumours reached 1,500–2,000 mm3. Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 per arm. Right, immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated ALK in TAE-resistant xenograft tumours (1 and 2) and sensitive and resistant cells in culture. b, Dose–response curves for TAE684 in sensitive and resistant cell lines established from the same tumour xenografts as in a (IC50 values: sensitive, 7.9 nM; resistant, 878.6 nM). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates. c, Tumour volumes (left) and Kaplan–Meier survival curves (right) of resistant cell xenografts in NU/NU (CrTac:NCr-Foxn1nu) mice treated with TAE684 (10 mg kg−1 by oral gavage once daily) or vehicle control for up to 56 days. Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 8 per arm. P values determined by Mann–Whitney U test for tumour volumes (P = 0.8404) and by log-rank test for Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (P = 0.8076), both two-sided. d, Dose–response curves for TAE684-sensitive and -resistant cells treated with ceritinib (IC50 values: sensitive, 33.8 nM; resistant, 446.5 nM) or lorlatinib (IC50 values: sensitive, 47.5 nM; resistant, 2,318 nM). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates. e, Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in sensitive and resistant cells treated with DMSO or 1 μM TAE684 for 6 or 24 h. f, Electropherograms of ALK kinase domain sequencing in sensitive and resistant cells. Arrows show the F1174L mutation characteristic of Kelly cells. HEK293T cells were used as a control for sequencing wild-type ALK. g, Phosphoproteomic analysis of a panel of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in sensitive and resistant cells. Each RTK is shown in duplicate and the pairs in the corners of each array are positive controls. Numbered RTKs with corresponding names listed on the right represent the highest-phosphorylated proteins. ALK is depicted in red. h, Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) and immunoblot analysis of ABCB1 and ABCG2 multidrug transporter expression in sensitive and resistant cells. The qRT–PCR data are means of n = 2 biological replicates. In a (immunoblot), d, f and g, data are representative of two independent experiments (see Supplementary Note 1 for details; for gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1).

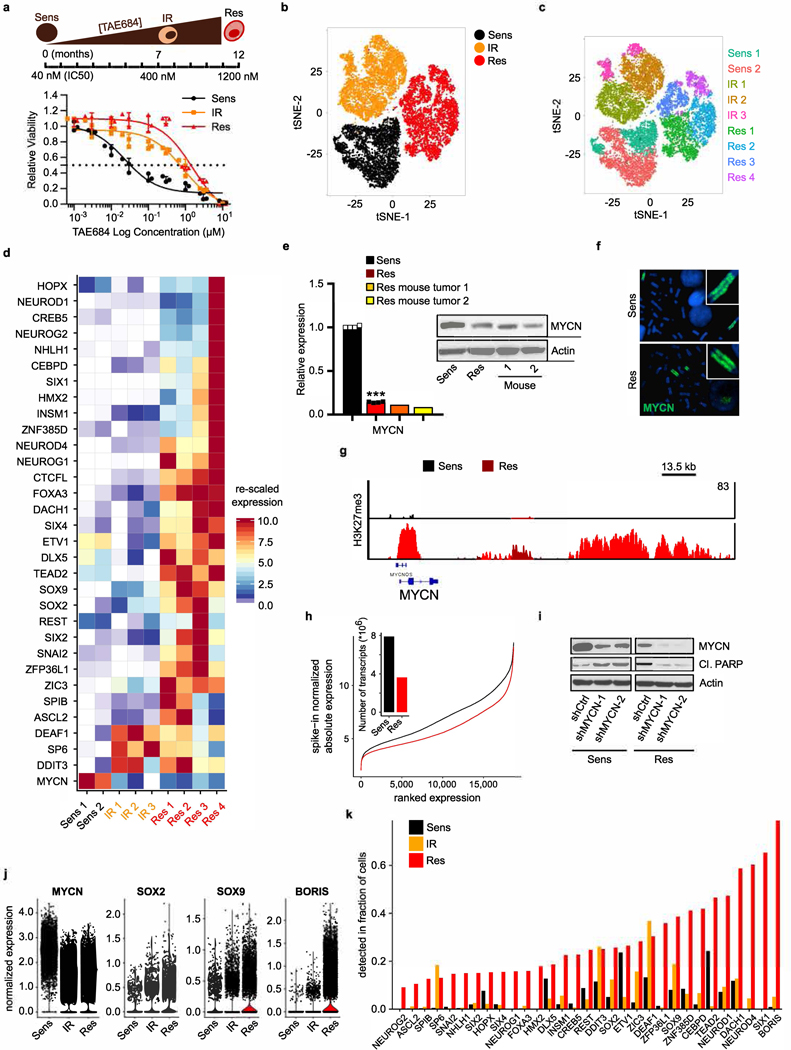

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Development of resistance is associated with loss of MYCN followed by gradual induction of proneural transcription factors.

a, TAE684 dose–response curves of Kelly neuroblastoma cells during resistance establishment (IC50 values: sensitive, 39.4 nM; intermediate, 618 nM; resistant, 1,739 nM). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates. Schematic representation of development of resistance is shown above. b, t-SNE plot of scRNA-seq data showing the segregation of sensitive (n = 5,432), intermediate (n = 6,376) and resistant (n = 6,379) cells. c, t-SNE plot depicting unsupervised clusters for the individual subpopulations that underlie the pseudotime analysis. d, Heat map of rescaled gene expression values of the most variable ranked transcription factors in the three cell states. e, qRT–PCR and immunoblot analysis of MYCN expression in TAE684-resistant xenograft tumours (1 and 2) and sensitive and resistant cells in culture. The qRT–PCR data are mean ± s.d., n = 4 biological replicates for sensitive and resistant cells (***P = 1.396 × 10−11; unpaired two-sided t-test) and n = 3 technical replicates for each tumour. f, Fluorescence in situ hybridization of MYCN in sensitive and resistant cells (representative of 20 nuclei per condition). g, ChIP–seq track of H3K27me3 binding at the MYCN locus in sensitive and resistant cells. Signal intensity is given in the top right corner. h, Line plot showing the association between genes ordered by expression (x axis) and changes in absolute gene expression levels (y axis) in sensitive versus resistant cells. Bar plot, total transcriptional yield in sensitive or resistant cells. i, Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in sensitive and resistant cells expressing control (shCtrl) or MYCN (shMYCN-1 and −2) shRNAs. j, Violin plots representing the expression distribution of selected genes in the same cells as in a (centre line, median). k, Bar plot showing the fractions of cells with detectable mRNA levels of the same genes as in d. In e (immunoblot) and f–i, data are representative of two independent experiments (for gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1).

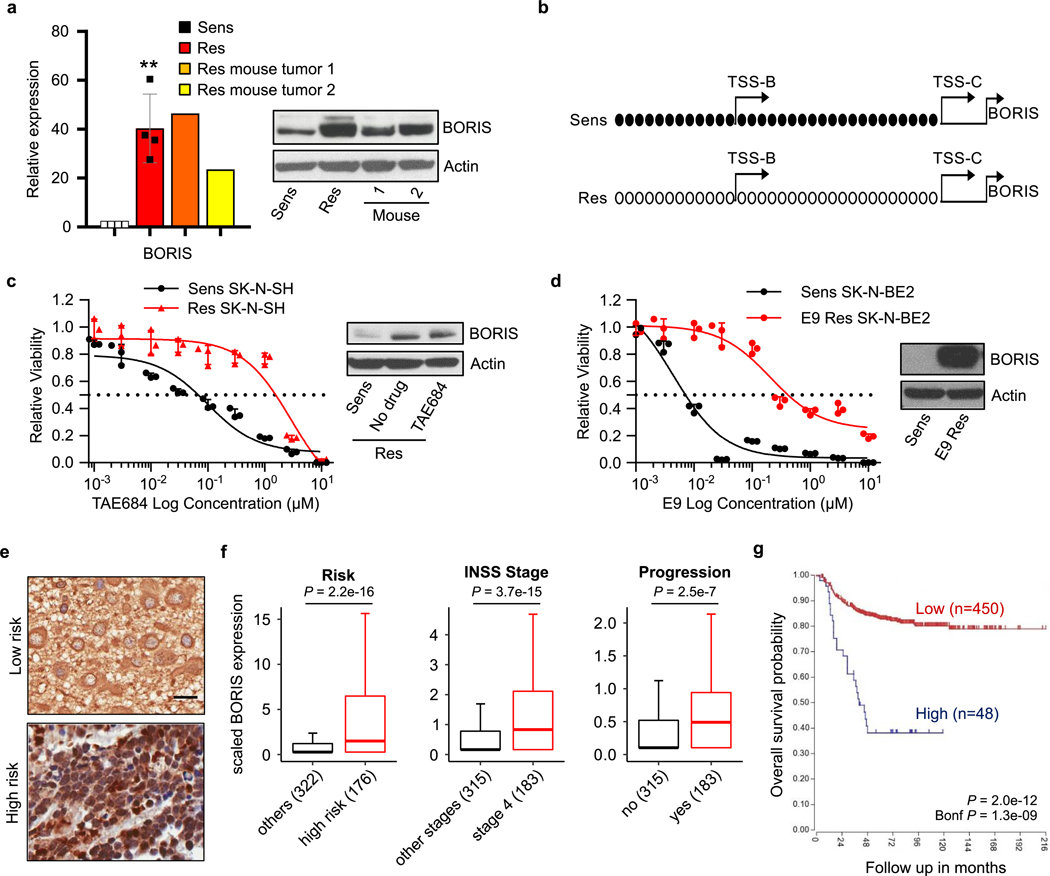

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Overexpression of BORIS is seen in resistance models of neuroblastoma and correlates with high-risk disease and a poor outcome.

a, qRT–PCR and immunoblot analysis of BORIS expression in TAE684-resistant Kelly cell xenograft tumours (1 and 2) and sensitive and resistant cells in culture. The qRT–PCR data are mean ± s.d., n = 4 biological replicates for sensitive and resistant cells (**P = 0.0014; unpaired two-sided t-test) and n = 3 technical replicates for each tumour. b, Bisulfite sequencing of the BORIS promoter in sensitive and resistant cells. Black circles represent methylated cytosine residues in a CpG dinucleotide, empty circles are unmethylated cytosines. The B and C TSSs are indicated by arrows. c, Dose–response curves to TAE684 (left) and immunoblot analysis of BORIS expression (right) in TAE684-sensitive and -resistant SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells (IC50 values: sensitive, 47.9 nM; resistant, 1,739 nM). d, Dose–response curves to the CDK12 inhibitor, E9 (left) and immunoblot analysis of BORIS expression (right) in sensitive and resistant SK-N-BE(2) neuroblastoma cells (IC50 values: sensitive, 9.5 nM; resistant, 638 nM). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates for c (left) and d (left). e, Immunohistochemical staining of BORIS expression in primary neuroblastoma tumour samples (representative of four independent experiments). Scale bar, 20 μM. f, Box plots showing correlation of BORIS expression with the indicated parameters in a human neuroblastoma dataset (n = 498; Tumour Neuroblastoma-SEQC-498; R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl)). Box plots are as defined in Fig. 4. P values were determined by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. g, Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival based on BORIS expression in the same dataset as in f (n = 498; two-sided log-rank test with Bonferroni correction). In a, c, d (immunoblots) and b, data are representative of two independent experiments. Sample sizes (n) are depicted in parenthesis for f and g (for gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Resistant cells are dependent on BORIS for survival.

a, Dose–response curves to TAE684 in resistant cells expressing control (shCtrl) or BORIS (shBORIS) shRNAs (IC50 values: shCtrl, 537.7 nM; shBORIS, 141.2 nM). Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates. b, Heat map of gene expression values in the same cells as in a (n = 2 biological replicates). Rows are z-scores calculated for each gene in both conditions. c, Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in the same cells as in a. d, e, Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins (Cl., cleaved; CC3, cleaved caspase 3) (d), and quantification of trypan blue staining (e) in sensitive and resistant cells expressing control (shCtrl) or BORIS (shBORIS-3 and −4) shRNAs. Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-sided t-tests). f–h, Phase-contrast microscopy images (scale bars, 150 μM) (f), growth curves (g) and flow cytometry analyses (h) of propidium iodide (PI) staining in sensitive, intermediate and resistant cells. Data are mean ± s.d., n = 3 biological replicates (***P < 0.0001 for all comparisons; two-way ANOVA). i, qRT–PCR analysis of the expression of the indicated proneural transcription factors in the same sensitive (DMSO) versus MYCNKD and BORISInd (DOX + TAE) cells as in Fig. 1g. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; unpaired two-sided t-tests). In c, d, f and h, data are representative of two independent experiments (for gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. BORIS colocalizes with CTCF and open chromatin.