Abstract

Older adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) receive care that is fragmented and burdensome, lacks evidence, and most importantly is not focused on what matters most to them. An implementation feasibility study of Patient Priorities Care (PPC), a new approach to care that is based on health outcome goals and healthcare preferences, was conducted. This study took place at 1 primary care and 1 cardiology practice in Connecticut and involved 9 primary care providers (PCPs), 5 cardiologists, and 119 older adults with MCCs. PPC was implemented using methods based on a practice change framework and continuous plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles. Core elements included leadership support, clinical champions, priorities facilitators, training, electronic health record (EHR) support, workflow development and continuous modification, and collaborative learning. PPC processes for clinic workflow and decision-making were developed, and clinicians were trained. After 10 months, 119 older adults enrolled and had priorities identified; 92 (77%) returned to their PCP after priorities identification. In 56 (46%) of these visits, clinicians documented patient priorities discussions. Workflow challenges identified and solved included patient enrollment lags, EHR documentation of priorities discussions, and interprofessional communication. Time for clinicians to provide PPC remains a challenge, as does decision-making, including clinicians’ perceptions that they are already doing so; clinicians’ concerns about guidelines, metrics, and unrealistic priorities; and differences between PCPs and patients and between PCPs and cardiologists about treatment decisions. PDSA cycles and continuing collaborative learning with national experts and peers are taking place to address workflow and clinical decision-making challenges. Translating disease-based to priorities-aligned decision-making appears challenging but feasible to implement in a clinical setting.

Keywords: patient priorities, practice change, older adults, multimorbidity

More than 40% of Medicare beneficiaries have multiple chronic conditions (MCCs).1 Providing health care for persons with MCCs involves multiple clinicians, medications, and self-care tasks2 and can be fragmented, siloed, and burdensome. There is little evidence to guide disease-specific care for people with MCCs, who are generally excluded from randomized controlled trials, leading to uncertainty in decision-making for clinicians.3,4 Most importantly, this care may not be focused on what matters most to persons with MCC.5

A national group of primary care and specialty clinicians (physicians and nurses), patients and caregivers, researchers, healthcare system representatives, health information technology (HIT) experts, healthcare redesign engineers, and payers designed a healthcare prototype to address these problems.6,7 This prototype, Patient Priorities Care (PPC), calls upon patients and caregivers to articulate their health priorities with the guidance of a trained member of the healthcare team, which are then communicated to all team members; patients, caregivers, and clinicians together choose the health care best aligned with these health priorities.6 Health priorities are defined as the patient’s health outcome goals—what they want from their healthcare—and their healthcare preferences—the healthcare activities they are able and willing to perform.

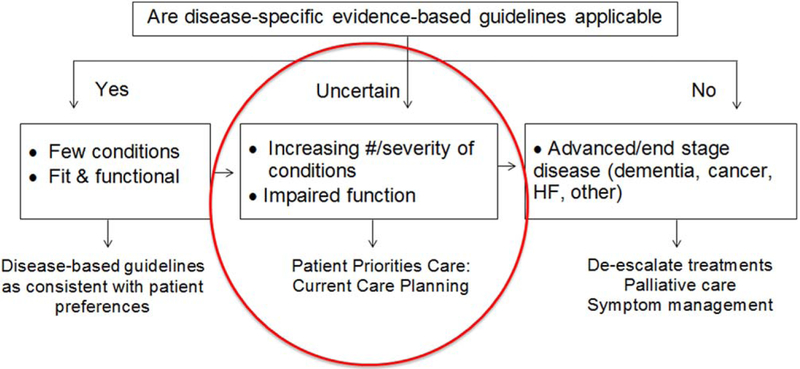

Patient priorities aligned care is perhaps most appropriate for individuals with MCCs for whom current evidence-based guidelines do not fit; Figure 1 illustrates a conceptual model. For individuals with few chronic diseases and good function, who resemble those in clinical trials, evidence-based disease guideline–driven decision-making is appropriate. Conversely, individuals with advanced disease or near the end of life should receive care based on evidence if evidence exists and palliative care as long as care is consistent with their goals and preferences.8–11 However, there is minimal evidence to guide care for the many older adults in a middle group with MCCs and functional limitations. For these individuals, informed priorities can guide clinical decision-making and current care planning.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model to guide patient priorities based clinical decision-making for older adults. The number of people in each of these 3 groups may vary depending on the population and the specific comorbidities or advanced disease. The model is intended to demonstrate that there is a substantial group of older adults (uncertain) for whom guideline-driven care or advanced disease care is of uncertain benefit or not appropriate.

The rationale and guiding principles for PPC and a general framework for implementing this care were reported previously.6,7 A companion article in this journal describes the development and testing of a values-based approach to helping older adults identify their health priorities.12 In this article, we describe the clinical implementation processes and implementation feasibility in a PPC pilot study. This pilot study is ongoing; participants are being recruited and followed, and data for the evaluation is being collected. Supplementary Appendix S1 has a logic model that gives an overview of PPC implementation and evaluation.

METHODS

Setting

In July 2015, PPC developers partnered with a multisite primary care group practice in Connecticut to design, implement, and evaluate a PPC prototype.6 We approached this practice because of its supportive leadership, involvement with primary care improvement initiatives, electronic health record (EHR), administrative data systems, and research division that could assist with evaluation. Its 81 practice sites are National Committee for Quality Assurance–qualified person-centered medical homes, participate with Managed Medicare Plans, and coordinate care with area hospitals and specialty practices through secure electronic messaging. This infrastructure and managed care experience was needed to implement PPC.

This large practice, providing care to nearly 15% of Connecticut residents,13 represents the growing number of practices owned by provider groups or hospitals. According to the American Medical Association, 67% of providers are in multi-or single-specialty group practices; 14% of providers are in practices with more than 50 providers.14 It shares challenges that most primary care practices face.15,16 Its EHR is not compatible with those of local hospitals or specialty practices, it struggles with primary care reimbursement and patient volume requirements, and it functions within a competitive healthcare marketplace. We implemented the PPC pilot in one of the practice’s multiple sites that includes a sufficient number of primary care practitioners (PCPs; 3 advanced practice nurses (APNs), 1 physician assistant, 5 physicians) and serves a large Medicare population—more than 2,000 Medicare beneficiaries, 18% of the practice’s patients. Its medical director (JR), a member of the practice’s leadership, agreed to function as the “clinical champion.”17

Because a core principle of PPC is alignment between primary and specialty care, the 5-member cardiology practice that provides cardiac care to the largest number of patients of the primary care practice was selected as the specialty practice. A clinical champion was identified from that practice.

Implementation team

The implementation team included the PPC developers6 and personnel from the practice. Practice team personnel included the Vice President for Research and Medical Education, the clinical champion, a research assistant, and 2 members of the implementation site’s healthcare team who serve as the health priorities facilitators (1 APN, 1 experienced case manager). The facilitators elicit health priorities from patients and caregivers and communicate this information to PCPs and cardiologists. A companion article in this journal explains the qualifications, training, roles, and activities of the facilitators.12 The implementation team also enlisted national experts in eliciting patient values, patient engagement, clinician–patient communication, clinician training, clinical practice change, and quality measurement and improvement.

Implementation strategy

We planned PPC implementation to follow a Practice Change Framework.18,19 This framework features leadership support, clinical champions, team care, training, workflow support, HIT enhancements, collaborative learning for clinical decision-making,20 and Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology for continual improvements in training and workflow (Table 1).21

Table 1.

Practice Change Components Implemented to Support Patient Priorities Care (PPC)

| Component | How Implemented |

|---|---|

| Leadership support and clinical champions |

|

| Patient priorities care teams assembled |

|

| Training for priority facilitators and clinicians with ongoing collaborative learning (feedback and decisional guidance) |

|

| HIT supports PPC |

|

| Clinic workflow in place to deliver PPC |

|

| Plan-Do-Study-Act process in place to improve workflow |

|

PCP = primary care provider; HIT = health information technology; EHR = electronic health record.

Development phase

The 11-month development phase involved developing the training processes and materials to prepare patients and caregivers, facilitators, and clinicians to implement PPC; beginning to build the clinic workflow; and exploring the practice’s HIT and data capabilities.

Develop training processes and materials

Development and testing of patient and facilitator training were the major activities during development.12,22,23 Briefly, patients need guidance to identify and articulate their health priorities, and facilitators need training to help patients through this process. With national experts and participation of the implementation team, especially the facilitators, an iterative process was developed to train facilitators to guide patients in identifying their priorities. The group developed facilitator and patient training methods, including manuals.

Primary and specialty clinicians also need preparation for PPC, including “buy-in” and training. We planned this preparation during the development phase, enlisting national experts in clinician training and clinician–patient communication to guide planning and provider preparation. We focused on developing communication strategies to address clinical uncertainty, tradeoffs, and health trajectories. To increase provider buy-in, our national experts in cardiovascular and primary care guidelines and performance measures planned how to engage providers during implementation to review deficiencies in how current evidence relates to patients with MCC.24

Clinical workflow development

Two months before implementation, the team began twice-weekly telephone discussions with the PCP office to plan workflow development and clinic staff training. The resulting draft workflow was then completed during the initial months of implementation.

Exploring HIT and data capabilities

During development, we worked with the primary care and cardiology practice HIT personnel to learn about their systems and develop relationships. The primary care practice uses the Allscripts Practice Management System and EHR. Capabilities to support PPC include multiple note types, communication about logistics (tasking), and secure faxing for referrals. The practice management system includes demographic characteristics of the practice’s patients, appointments, diagnoses, medications, and billing and financial information. The EHR can be configured to allow free-text phrases and drop-down menus for critical information. The cardiology group uses a different EHR with similar capabilities.

PPC Implementation

Implementation was phased in beginning with the primary care clinical champion and expanding to all the providers in the primary care and cardiology practices over a 3-month period. Implementation processes were modified using PDSA to allow the implementation team, providers, and clinic staff to identify and solve challenges.

Implementation included provider preparation for PPC, development and implementation of the clinical workflow, exploration of HIT capabilities, establishment of PDSA methods to address workflow tasks and challenges, and establishment of provider collaborative learning to address challenges in patient priorities aligned clinical decision-making.

Provider Preparation

We held two 2-hour training sessions before including all providers in PPC implementation. The first session included PCPs; the second included PCPs and cardiologists. We limited background material to the AGS Guiding Principles for Care of Patients with MCC24 and a 20-minute webinar overview of PPC. National experts on practice change, patient–physician and PCP–specialist communication, and guidelines and quality measurement who helped design these sessions also attended the sessions. We based trainings on patient scenarios and gave clinicians sample scripts illustrating how to discuss patient priorities. Our experts introduced discussion methods for challenging topics such as trade-offs, uncertainty, and health trajectories to be further considered in future collaborative learning sessions. We used role-playing with patient actors for clinicians to practice these conversations and to think about operationalizing patient priorities based decision-making. Clinicians were reimbursed for attending these trainings.

Clinical workflow development

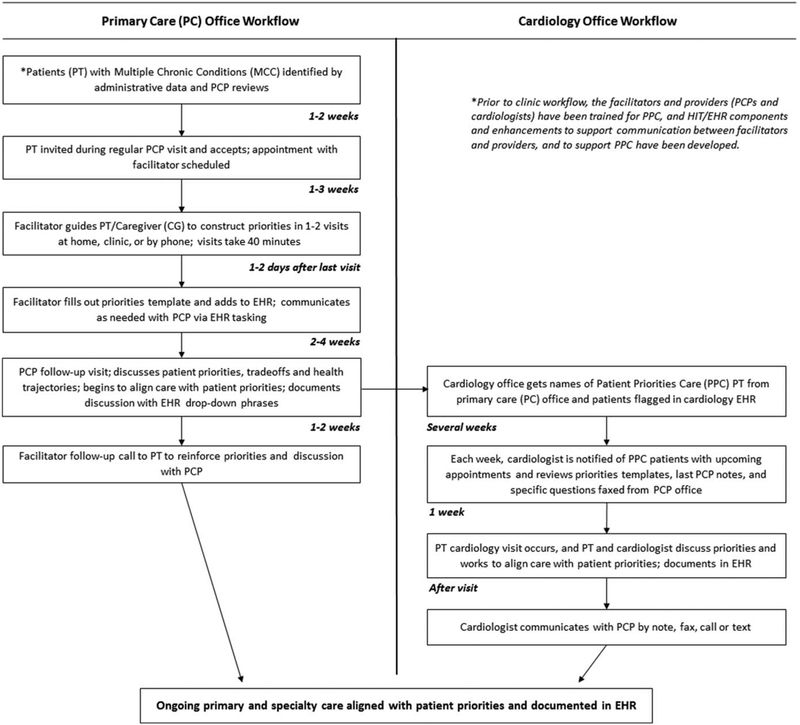

The implementation team and, when needed, the primary care office staff (LPN, medical assistants) participated in workflow development and refinement in weekly calls and monthly in-person meetings (ongoing). Activities to coordinate workflow with the cardiology office were less intensive (in-person meetings every 2 months, calls every 2 weeks) because cardiologists focus on priorities related to cardiac conditions in already-identified patients. Table 1 has details, and Figure 2 illustrates the clinical workflow.

Figure 2.

In the primary care provider (PCP) office, eligible patients are identified, the PCP invites them, and they are given a facilitator appointment. Facilitators guide patients in developing priorities and filling out a priorities template for the electronic health record (EHR). The patient returns to the PCP at a regular or special visit and discusses priorities. PCP and patient work to align care with priorities. Facilitator then follows up with patient to reinforce priorities. The primary care and cardiology offices communicate regarding PPC patients to ensure patients are flagged in cardiology EHR and that the cardiologist has referral, priorities template, and PCP note. Cardiologist discusses priorities and works to align care with patient priorities. Cardiologist and PCP communicate.

Identify appropriate patients for PPC.

Potentially eligible patients with more than 3 chronic conditions, with 10 or more medications, or seeing more than 2 specialists in the past year were identified using administrative data (EHR). Exclusion criteria included hospice eligibility, advanced dementia, nursing home residence, or dialysis (excluded because resources did not allow nephrologist preparation for this pilot). Providers reviewed administrative lists of possible patients the week before the patient’s PCP visit; the final decision about inviting patients was left to clinician discretion.

PPC clinical workflow.

The PCP invites the patient to participate in PPC during a routine visit. If the patient accepts, the medical assistant immediately provides the patient with written information about PPC and notifies the facilitator, who schedules a visit at home or in the clinic for health priorities identification. One session (rarely 2) lasting approximately 40 minutes results in priorities identification. After this, another PCP visit occurs, preferably within 4 to 6 weeks, to discuss preliminary health outcomes goals, and care preferences, informed by the patient’s health trajectory and care trade-offs. Generally, providers incorporate this discussion into a regular visit, but some schedule a visit devoted to PPC. Subsequently, usually over the telephone, the facilitator helps the patient refine his or her priorities and encourages patient activation regarding his or her priorities. This concentrated initiation process initiates PPC for patients and clinicians, increasing the likelihood that PPC becomes part of ongoing care.

Facilitator–clinician communication.

The facilitators communicate with PCPs in short notes called “tasks.” Tasking is an intra-office, EHR-based communication about patient issues and status. After the initial facilitation visit(s), facilitators complete a patient priorities template12 that is entered into the EHR.

Communication between the primary care and cardiology practices.

Because they have different EHRs, direct primary care office to cardiology office communication by telephone and secure fax was needed. The PCP office identified all shared PPC patients to the cardiology office, where patients were “flagged” in the EHR. In turn, the cardiology office notified the PCP office the week before PPC patients had a cardiology appointment. Then the PCP filled out a referral with questions relevant to patient priorities and faxed it to the cardiologist, along with the priorities template and recent PCP note. During initial training, PCPs and cardiologists exchanged cellular telephone numbers and agreed to secure text messaging.

Health Information Technology

In the primary care office, existing Allscripts tasking and note types were appropriate for PPC. HIT enhancements for PPC included accessing administrative data to identify eligible patients, creating the note template to communicate patient priorities12, and imbedding basic EHR phrases for PCPs to use in progress notes to reflect patients’ priorities aligned decision-making. These phrases are variations on “Clinical decisions were based on discussions with patients of their health outcomes goals, preferences, and likely health trajectory” (Supplementary Appendix S2). Cardiology practice HIT personnel developed a “flag” for PPC patients and identical EHR note phases.

Plan-Do-Study-Act

Previously described telephone and in-person meetings of the implementation team and PCPs and cardiologists are used for the PDSA process and are ongoing. National experts join the meetings when relevant.

Collaborative learning

Collaborative learning helps providers improve their skills in aligning clinical decision-making with patient priorities; ongoing sessions will continue until the pilot ends. Sessions occur every other week at noon and during monthly meetings as 15-minute “huddles” for PCPs and once a month before office hours and every 2 months during in-person meetings for cardiologists. Providers review selected patient priorities, health concerns, and current care and discuss strategies for aligning care with patient priorities. Initially, members of the development team and national experts participated in these sessions by telephone. Clinicians now conduct sessions on their own.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the practice change processes described in Methods; all were successfully implemented. Ten months into implementation, all clinicians who participated in the training continue to participate, and 119 patients have identified their priorities.12 Ninety-two patients (77%) have returned to their PCP to begin PPC. Of these, 57 (62%) had a return PCP visit within 6 weeks of priorities identification, 56 had a discussion about priorities documented in the provider note using key phrases, and 55 have seen or are scheduled to see a cardiologist.

Incorporating PPC into clinical workflow

Clinical workflow changes supporting PPC were modest for medical assistants, other office staff, and clinicians. Providers and clinical staff identified workflow challenges through the PDSA process. Table 2 describes these challenges (e.g., patient identification, lags in recruitment, incomplete documentation, concerns about provider time and patient copayments) and the strategies that addressed them, leading to improvement in workflow.

Table 2.

Challenges to Implementing Patient Priorities Care (PPC)

| Workflow Challenges | Strategies to Address Challenges and Improve Workflow |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Decision-making challenges | Strategies to Address Challenges and Support PPC Decision-making |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PCP = primary care practitioner; EHR = electronic health record; MCCs = multiple chronic conditions.

Moving to patient priorities aligned decision-making

Aligning decision-making with patient priorities proved more complicated than workflow development. Collaborative learning sessions with providers identified multiple challenges, including buy-in to PPC, perceptions that clinicians were “already doing it”, concerns about unrealistic or changing patient priorities, patient focus on treatment burden versus clinician concerns about risk of future morbidity and mortality, and differences between PCPs and specialists about aligning care based on patient priorities. Potential solutions are presented in Table 2; challenges are being addressed in ongoing collaborative learning sessions.

DISCUSSION

This study operationalized the training methods, clinical workflows, and clinical decision-making that can align care with patient priorities, demonstrating the feasibility of PPC. PDSA cycles and collaborative learning methods helped us identify and address challenges.

Clinical workflow redesign, including HIT support, was relatively modest. Some complex workflow challenges, such as limited time, poor communication with specialists, and reimbursement challenges, are similar to those that other practice change innovations face.25 Workflows that take advantage of new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services codes designed to increase reimbursement for care coordination and advance care planning may mitigate some financial concerns (Chronic Care Management Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 99490, 99487, 99489; Advance Care Planning CPT codes 99497, 99498). Clinicians identified the mismatch between current disease-specific guidelines and quality measures and PPC for people with MCCs as a challenge. Appropriate quality metrics for such patients is an important national policy challenge that many groups are working to address.

Workflow redesign, although necessary, was not sufficient to ensure delivery of PPC. Clinical decision-making that translates disease-specific care into care based on patient priorities is a fundamental change in clinical approach that requires appreciation of the need to shift one’s practice (buy-in); training and collaborative learning; and then a gradual culture change for patients, clinicians, and health systems.

Our study has several strengths. It is the first to operationalize a paradigm of current care planning and care delivery based on patient priorities that is designed for the growing population of older adults with MCCs. We monitored challenges to workflow and clinical decision-making in real time in a clinical practice setting. Potential solutions were proposed and tested with input from multiple perspectives, including patients, clinicians, and national experts. PDSA cycles and collaborative learning proved to be complementary, viable methods of improving processes and developing priorities aligned clinical decision-making.

The study also has limitations. Its duration was short, and it involved a single site with a small group of clinicians and patients. Practice changes, particularly those that require such a marked change in culture and decisional focus, will take time and effort of many groups. This study is meant as a first step. Clinicians and clinics received a small stipend for participation, which can be considered a limitation, but because PPC is a new and different approach to care, the PCPs, cardiologists, and their clinic staffs participated in learning to operationalize PPC. Many of these efforts will not need to be replicated in future PPC implementation. Similarly, the study compensated for the facilitator role, but the facilitators were instrumental in developing training processes. Existing care coordinators found in many health systems and group practices may be able to assume the priorities facilitator role.

We are using mixed methods analyses to evaluate outcomes over the duration of this continuing pilot,26–28 including formal qualitative evaluations of patient and clinician experiences with PPC. Our quasi-experimental design will compare patient-reported and usage outcomes of patients receiving PPC and comparable patients receiving usual care in another primary care practice within the health system.

If shown to improve outcomes in the current patient sample and subsequent populations, PPC offers the opportunity to deliver person-centered care by current care planning based on patient priorities. This approach features standardized, replicable methods to discuss and select from among care options based on each person’s priorities. This pilot is an initial but important step, suggesting that patient priorities–aligned decision-making and care are challenging but feasible.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1: Patient Priorities Care Logic Model

Appendix S2: Electronic Health Record (EHR) Clinician Documentation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Eliza Kiwak, Pierrot Rutagarama and Lori Iwanicki.

Financial Disclosure: The current study was supported by grants from the John A. Hartford Foundation, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Investigators received additional support and resources from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 NIH/NIA); the Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care at the New York University School of Medicine; and the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN 13-413) at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC.

This work was made possible through the effort and dedication of Jeffrey Goldberg, MD; Andrew Selinger, MD; Vijai Muthukrishan, MD; Lea Bailey, MD; Kelli Reola, APRN; Meg Rush, MD; and Lauren Vo, APRN from the ProHealth Bristol Family Medical Group: and cardiologists Liran Blum, MD; Fawad Kazi, MD; Joseph Marakovits, MD; and Michael Whaley, MD from the Bristol Hospital Multi-Specialty Group.

Sponsor’s Role: The grant sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carlos O, Weiss CO, Boyd CM et al. Patterns of prevalent major chronic disease among older adults in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:1160–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd CM, Wolff J, Giovannetti E et al. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med Care 2014;52:S118–S125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannetti ER, Dy S, Leff B et al. Performance measurement for people with multiple chronic conditions: Conceptual model. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e359–e366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP et al. Patient-provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried TR MS Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple conditions on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1839–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinetti ME, Esterson J, Ferris R et al. Patient priority-directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med 2016;32:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferris R, Blaum C, Kiwak E et al. Perspectives of patients, clinicians, and health system leaders on changes needed to improve the health care and outcomes of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Aging Health 2018;30:778–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaffer JA, Maurer MS. Multiple chronic conditions and heart failure: Overlooking the obvious? JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison RS, Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2582–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolle SW, Black AL, Meier DE. End-of-life advanced directive. New Engl J Med 2015;372:667–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naik AD, Dindo L, Van Liew et al. Development of a clinically feasible process for identifying patient health priorities. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; doi: 10.1111/jgs.15437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casalino LP, Chen MA, Staub CT et al. Large independent primary care medical groups. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane CK. Policy Research Perspectives Updated Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: Physician Ownership Drops Below 50 Percent. American Medical Association Economic and Health Policy Research, May 2017. (online). Available at https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/health-policy/PRP-2016-physician-benchmark-survey.pdf. Accessed February, 2018.

- 15.Goldberg DG, Mick SS, Kuzel AJ, Feng LB, Love LE. Why do some primary care practices engage in practice improvement efforts whereas others do not? Health Serv Res 2013;48(2 Pt 1):398–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, McDaniel RR. Small primary care practices face four hurdles—including a physician-centric mind-set—in becoming medical homes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2417–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw EK, Howard J, West DR et al. The role of the champion in primary care change efforts: from the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices and Partners (SNOCAP). J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:676–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN et al. Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci 2016;11:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: A conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noël PH, Lanham HJ, Palmer RF et al. The importance of relational coordination and reciprocal learning for chronic illness care within primary care teams. Health Care Manage Rev 2013;38:20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batalden PB, Stoltz PK. A framework for the continual improvement of health care: Building and applying professional and improvement knowledge to test changes in daily work. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1993;19:424–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye JA, Karel MJ. Health values and treatment goals of older, multimorbid adults facing life-threatening illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naik AD, Palmer N, Petersen NJ et al. Comparative effectiveness of goal setting in diabetes mellitus group clinics: Randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: Insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care 2011;49 Suppl:S28–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Med Care 2012;50:217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fetters MD, Curry LA Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48(6 Pt 2): 2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications; 2011. Thousand Oaks, California. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Patient Priorities Care Logic Model

Appendix S2: Electronic Health Record (EHR) Clinician Documentation