Abstract

Recently, the metabolites separated from endophytes have attracted significant attention, as many of them have a unique structure and appealing pharmacological and biological potentials. Isocoumarins represent one of the most interesting classes of metabolites, which are coumarins isomers with a reversed lactone moiety. They are produced by plants, microbes, marine organisms, bacteria, insects, liverworts, and fungi and possessed a wide array of bioactivities. This review gives an overview of isocoumarins derivatives from endophytic fungi and their source, isolation, structural characterization, biosynthesis, and bioactivities, concentrating on the period from 2000 to 2019. Overall, 307 metabolites and more than 120 references are conferred. This is the first review on these multi-facetted metabolites from endophytic fungi.

Keywords: endophytes, isocoumarins, dihydroisocoumarins, biosynthesis, biological activities

1. Introduction

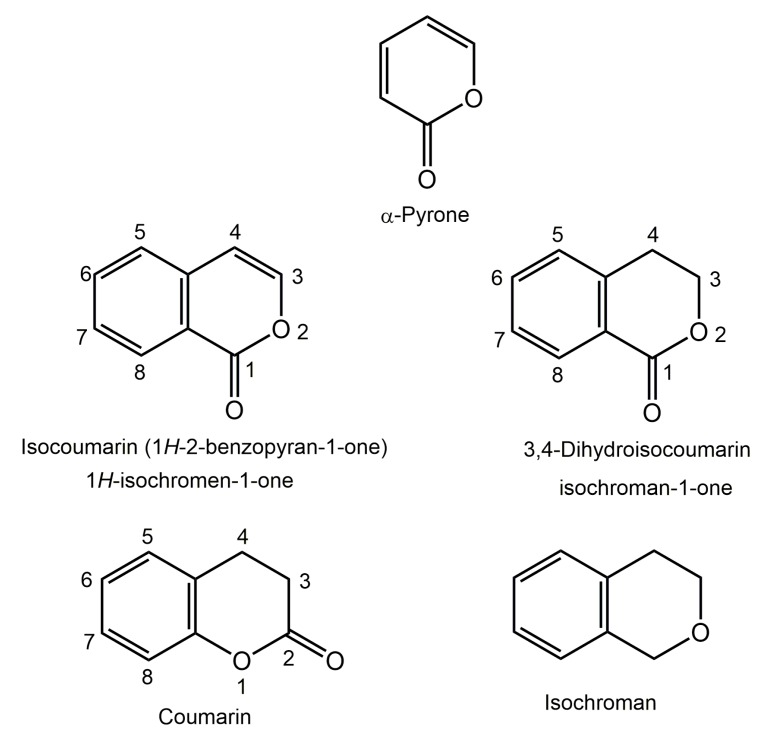

The search for new metabolites for the agrochemical and pharmaceutical industries is an on-going work that needs continual optimization. Fungi are eukaryotic microorganisms that reside in almost all environmental types in nature where they have key roles in preserving the ecological balance [1,2]. Endophytes primarily inhabit their hosts without causing any harm to the hosts [3,4,5,6]. These endophytic fungi have played pivotal roles in their host’s survival through supplying nutrients and producing plenty of bioactive metabolites to prevent the danger of phytopathogenic bacteria on the host [7,8]. Endophytic fungi have gained loads of attention in natural products chemistry field due to their sustainability to biosynthesize structurally diverse and bioactive molecules, some of which are important agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals [9,10]. Isocoumarins (1H-2-benzopyran-1-ones or isochromene derivatives) are a class of biosynthetically, structurally, and pharmacologically intriguing natural products, which are coumarins isomers with a reversed lactone moiety that could possess 6,8-dioxygenated pattern, 3-(un)substituted phenyl ring or 3-alkyl chain (C1-C17) [11,12]. The oxygenation could exist at one or more of the six free positions of the isocoumarin skeleton. The oxygen atoms may be in the form of ethereal, phenolic, or glycosidic functionalities. Additionally, C-3 substituents are found more commonly on both natural and synthetic isocoumarins derivatives. Substituents that exist on the isocoumarin ring may involve alkyl, halogen, heterocyclic, aryl, or other groups [13]. Furthermore, the saturation of C-3/C-4 in isocoumarins will give 3,4-dihydroisocoumarins (DHICs) analogs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Isocoumarin, 3,4-dihydroisocoumarin, coumarin, and isochroman skeletons.

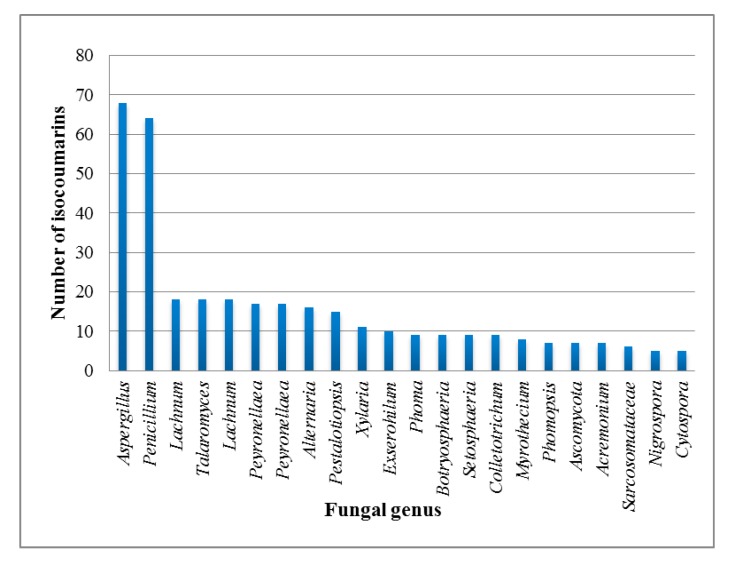

Moreover, isocoumarins and DHICs possess a close relation with isochromans, they are known as isochromen-1-one and isochroman-1-ones, respectively, since the C-1 active methylene in isochromans can be easily oxidized to the related isocoumarins derivatives. Most of the natural isocoumarins and DHICs are given trivial names, which are derived mainly from the name of the species or genus of the host organisms. They have been reported from a broad scope of natural sources, including plants, microbes, marine organisms, bacteria, insects, liverworts, and fungi (e.g., soil, endophytic, and marine fungi) [14,15]. Isocoumarins are considered as important intermediates in the synthesis of a wide range of carbo- and heterocyclic compounds such as isoquinolines, isochromenes, and different aromatic compounds [16]. Thus, isocoumarin framework has been explored in various areas, including drug discovery, pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry, and organic synthesis [13]. It has been reported that these metabolites possess various bioactivities: antimicrobial, cytotoxic, algicidal, antiallergic, immunomodulatory, antimalarial, plant growth regulatory, and acetylcholinesterase and protease inhibitors [11,17,18,19,20]. This review aims to give a highlight on the naturally occurring isocoumarins derivatives reported from endophytic fungi, focusing on the period from 2000 to July 2019. Herein, 307 naturally occurring isocoumarins derivatives have been listed most of them are reported from Aspergillus and Penicillium genera (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of isocoumarin derivatives in different fungal genus.

The reported fungal isocoumarin derivatives are drawn according to their similarity in the isocoumarin skeleton, as well as nomenclature (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29 and Figure 30).

Figure 3.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 1–16.

Figure 4.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 17–33.

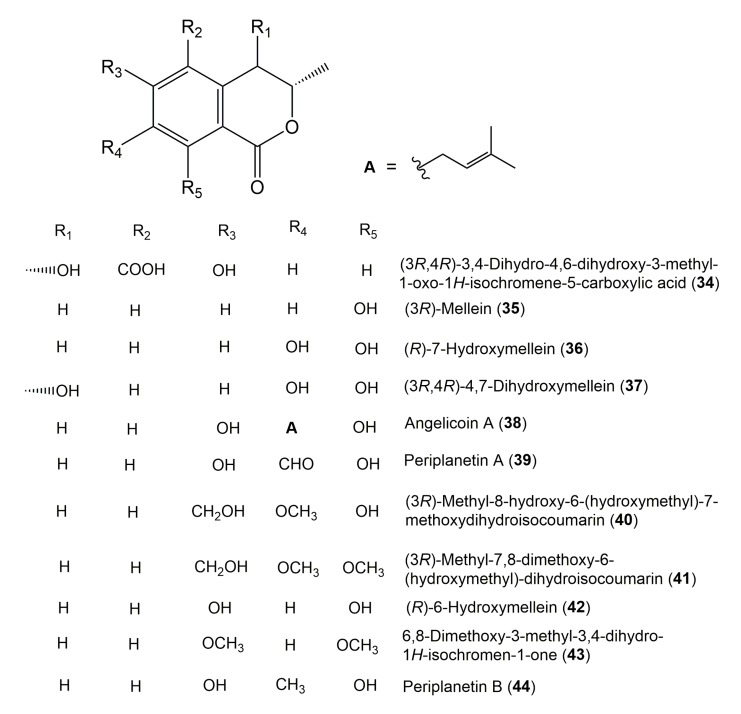

Figure 5.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 34–44.

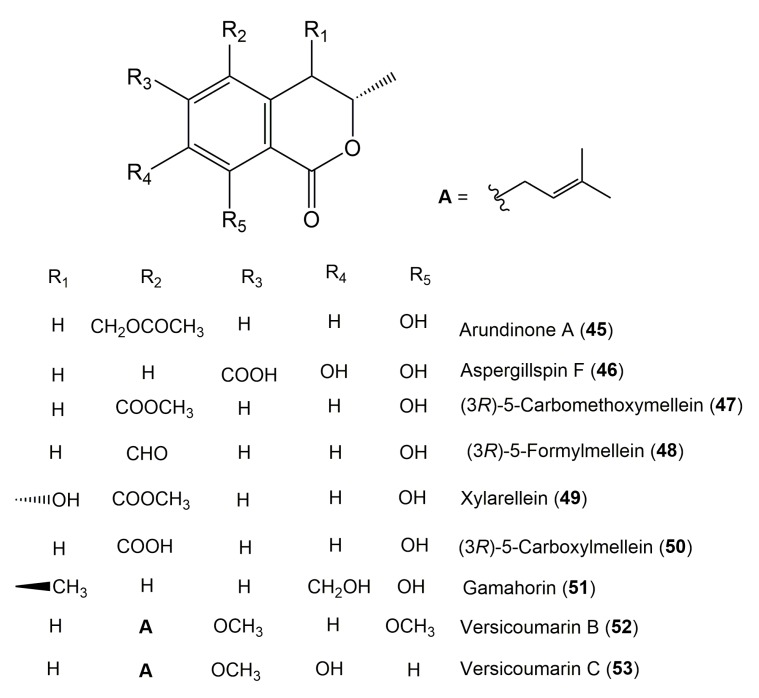

Figure 6.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 45–53.

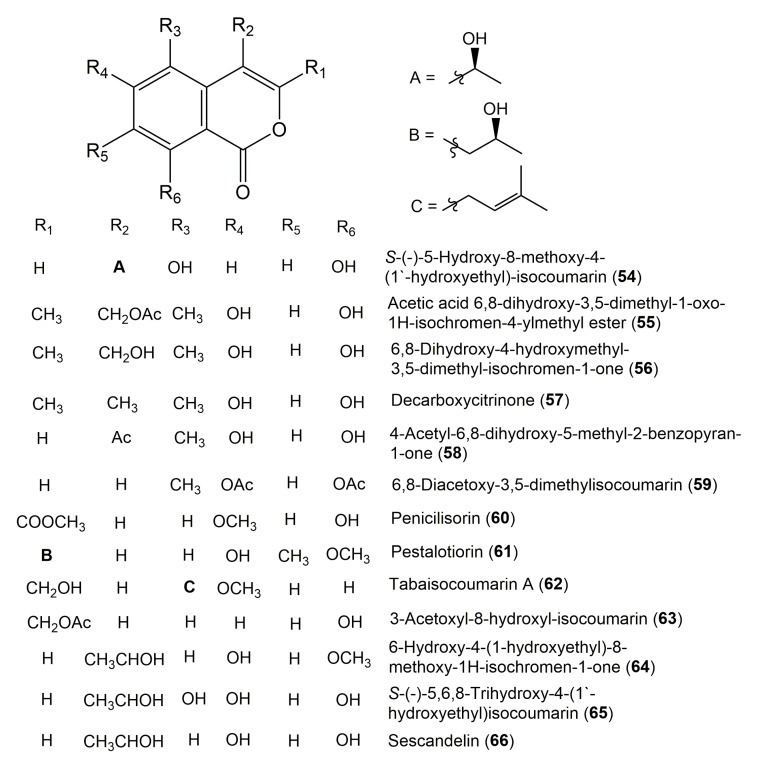

Figure 7.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 54–66.

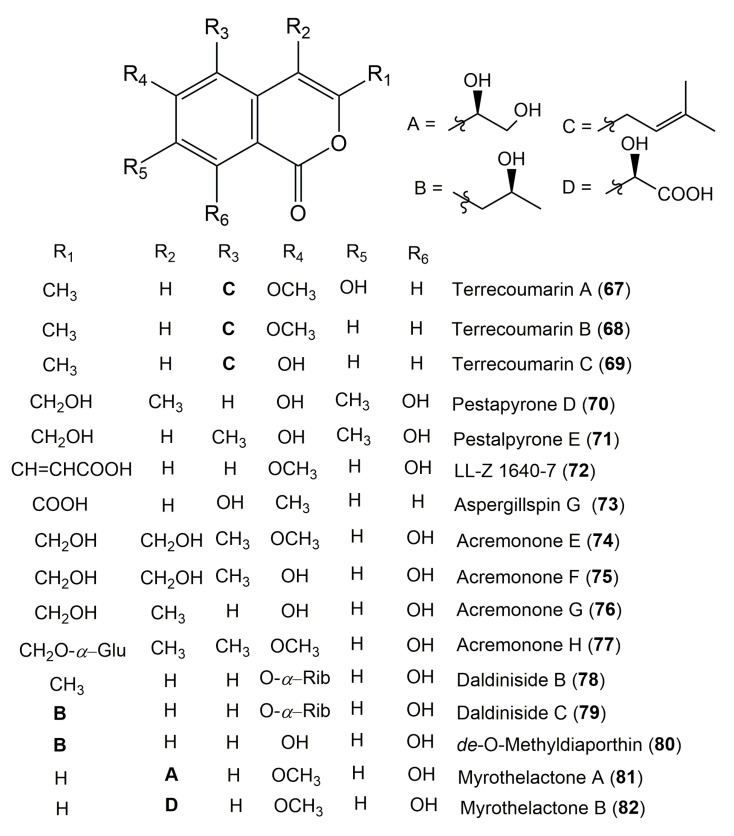

Figure 8.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 67–82.

Figure 9.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 83–96.

Figure 10.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 97–105.

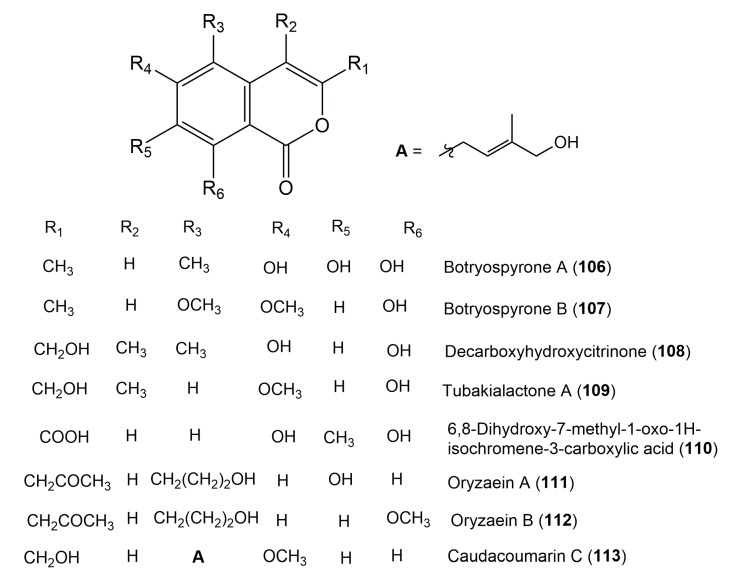

Figure 11.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 106–113.

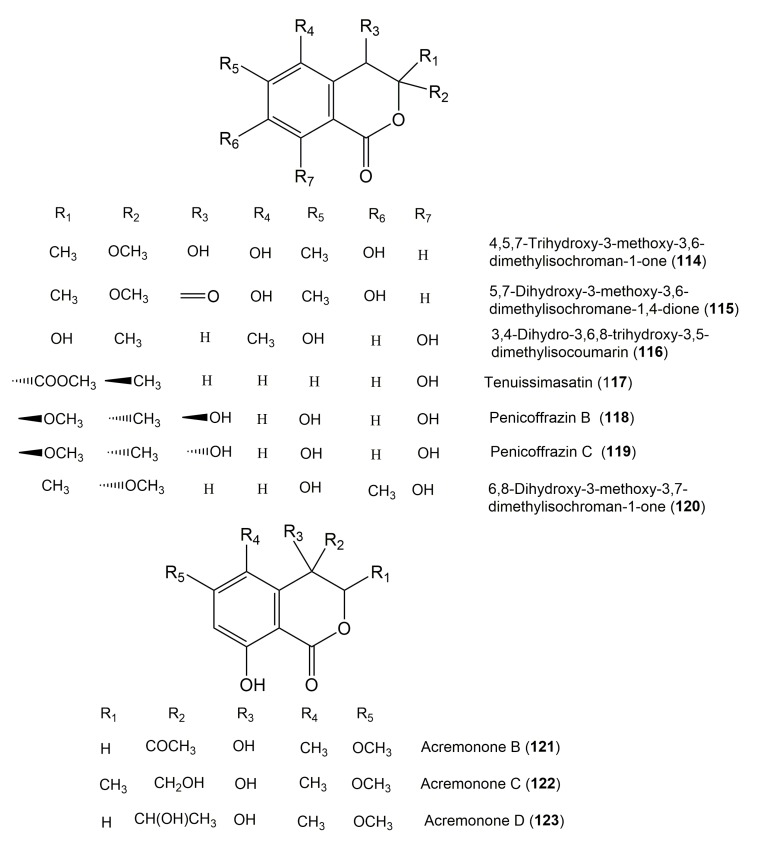

Figure 12.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 114–123.

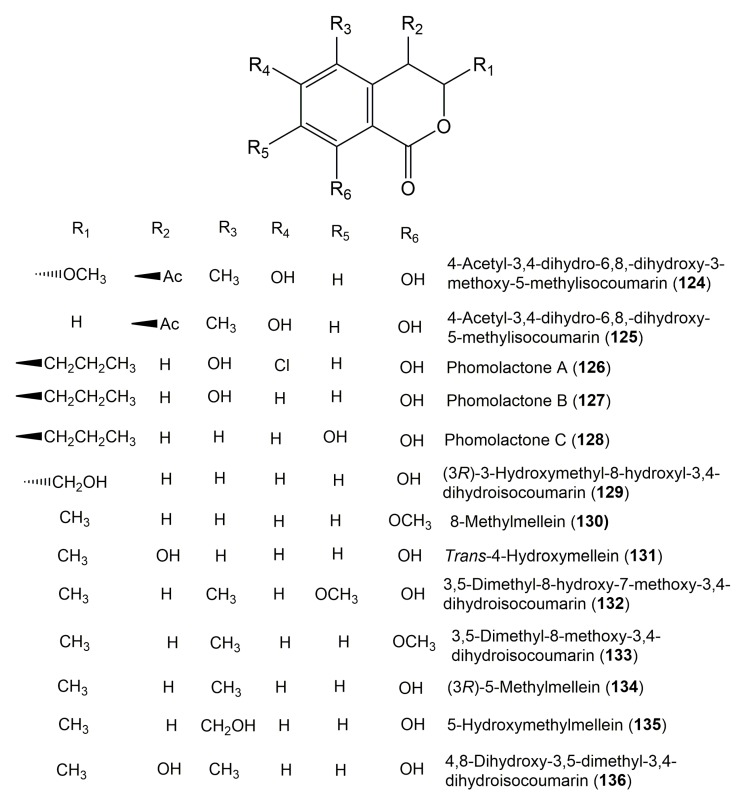

Figure 13.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 124–136.

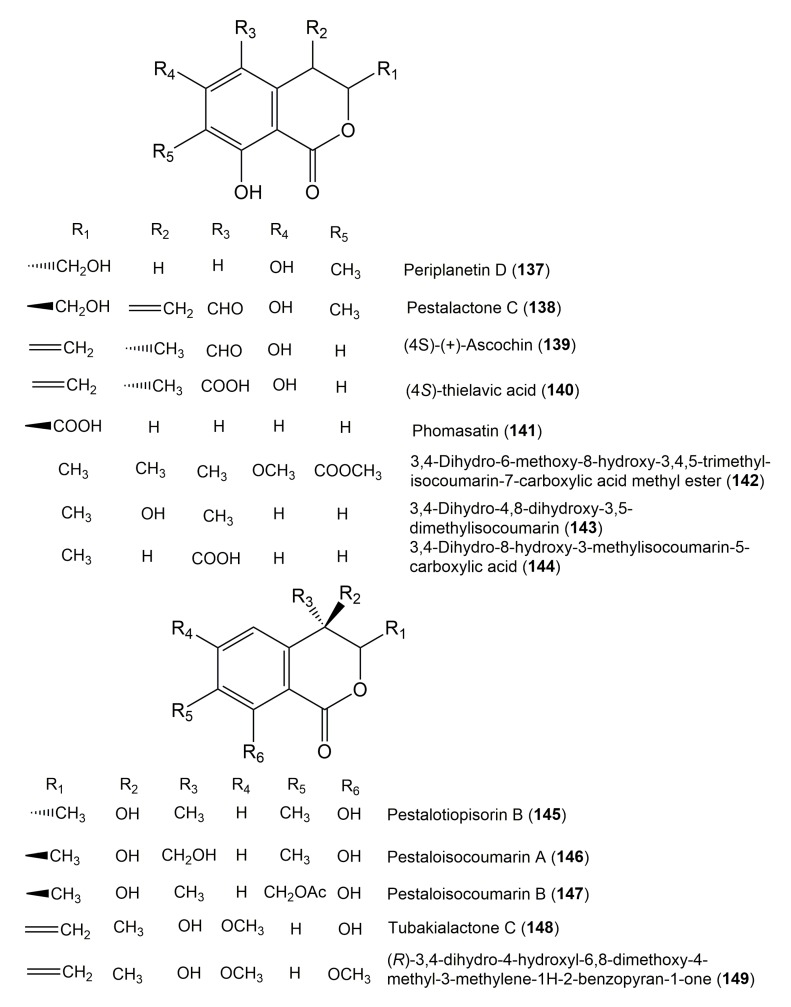

Figure 14.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 137–149.

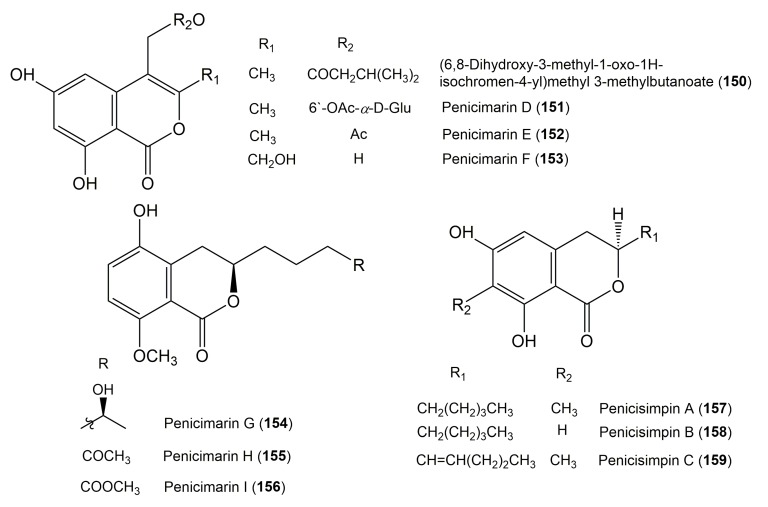

Figure 15.

Structure of isocoumarin derivatives 150–159.

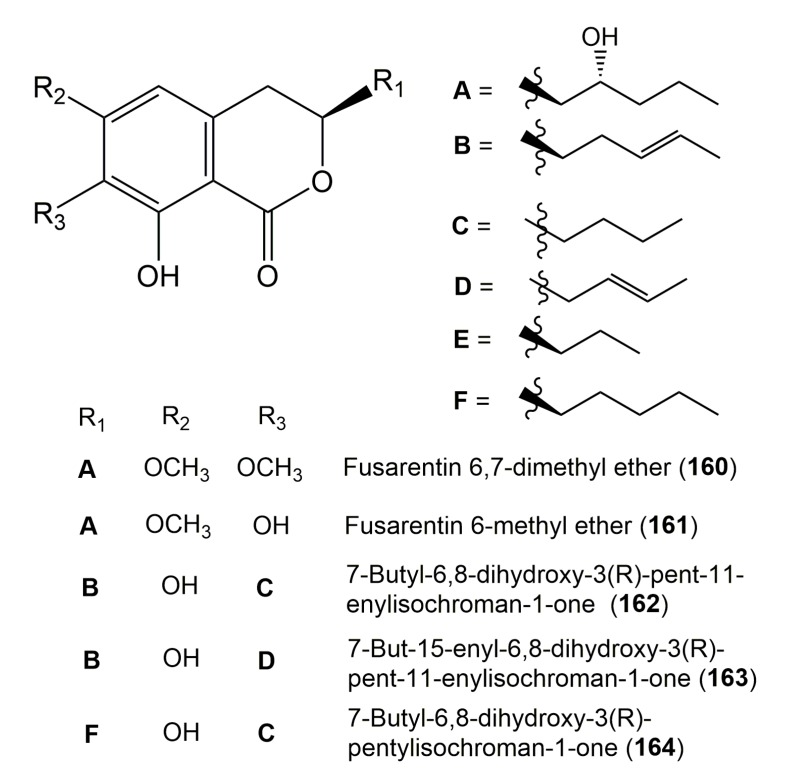

Figure 16.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 160–164.

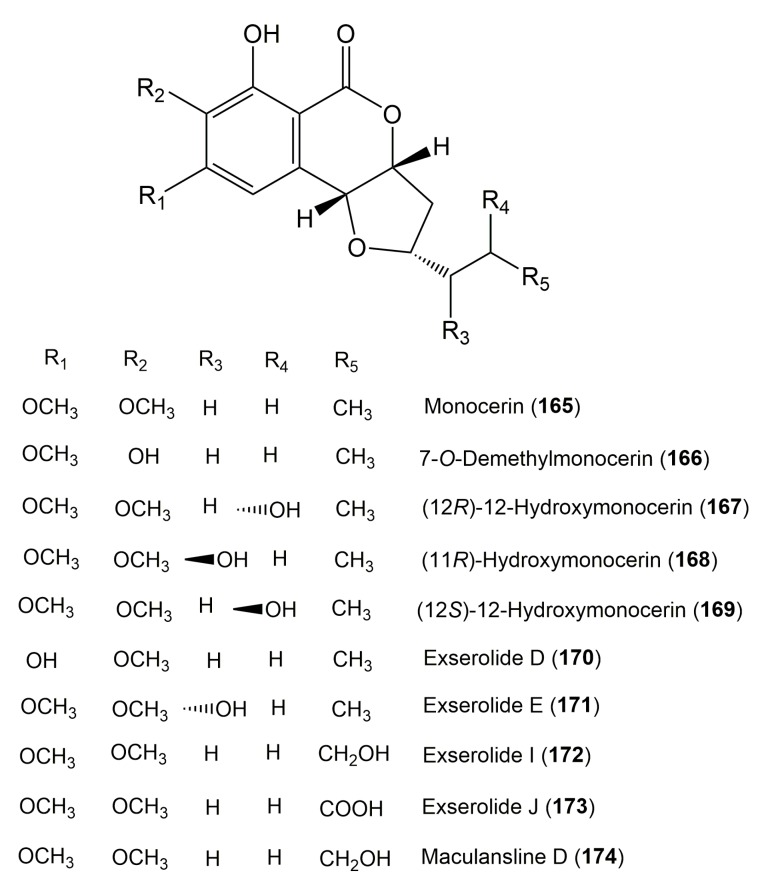

Figure 17.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 165–174.

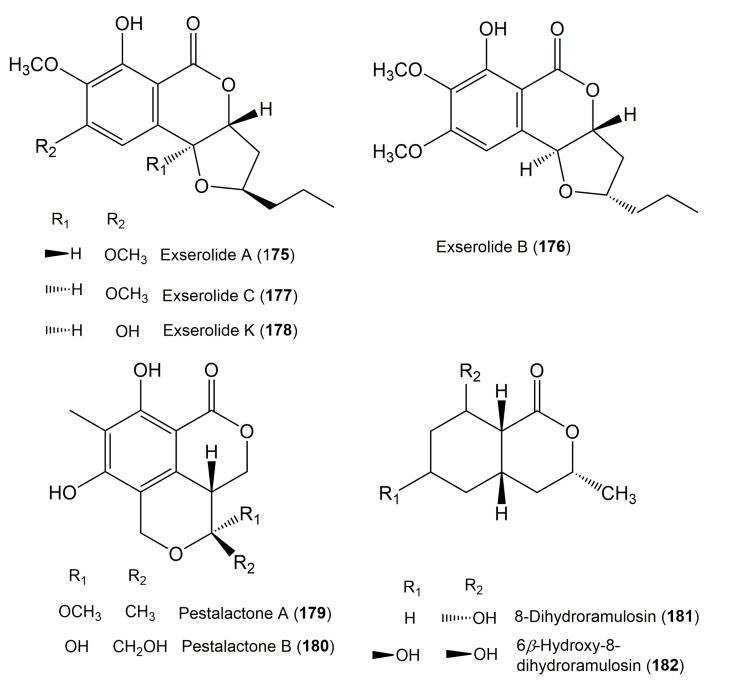

Figure 18.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 175–182.

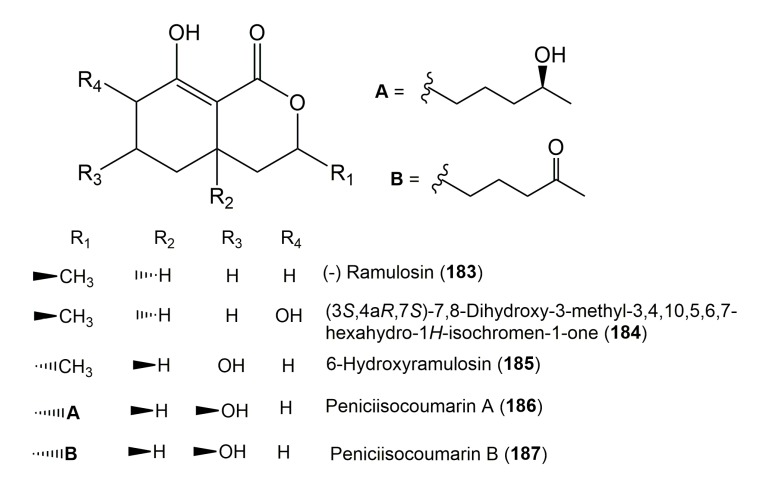

Figure 19.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 183–187.

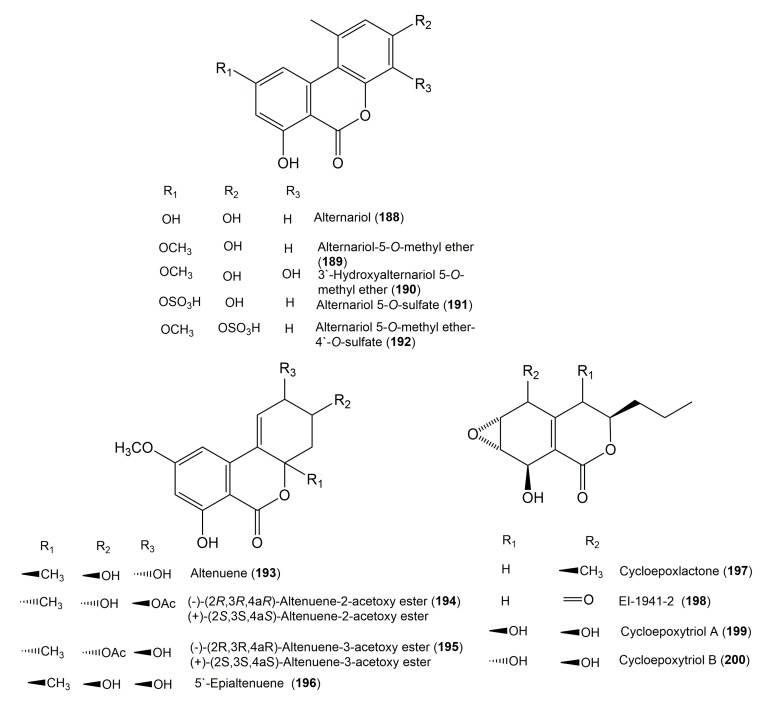

Figure 20.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 188–200.

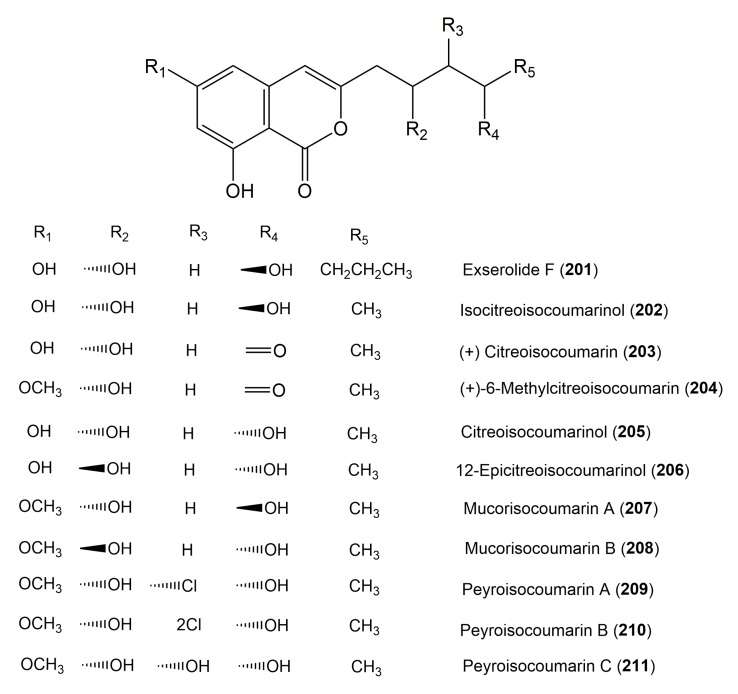

Figure 21.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 201–211.

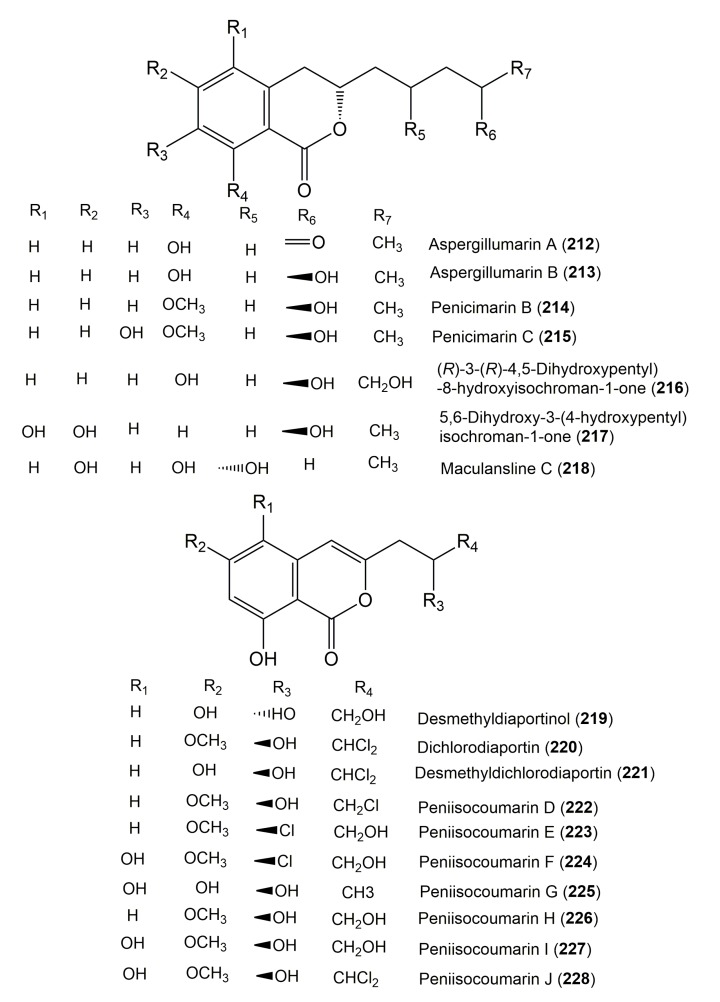

Figure 22.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 212–228.

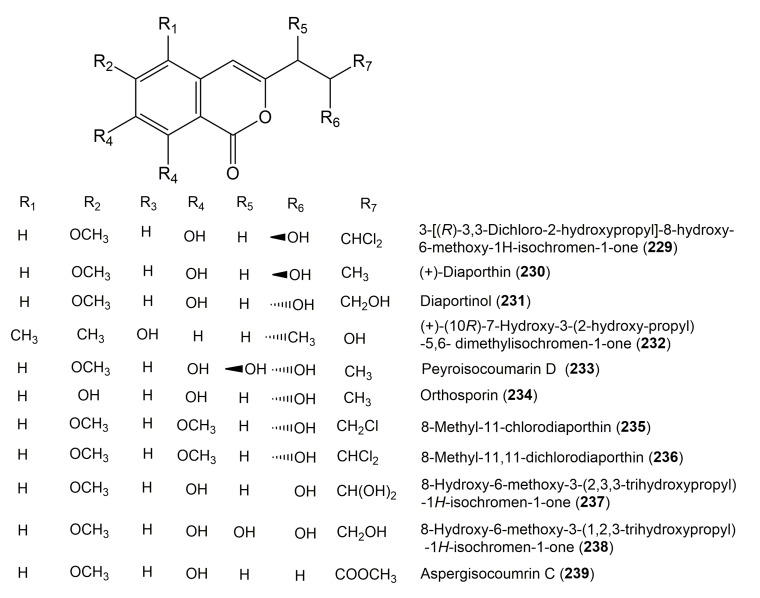

Figure 23.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 229–239.

Figure 24.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 240–250.

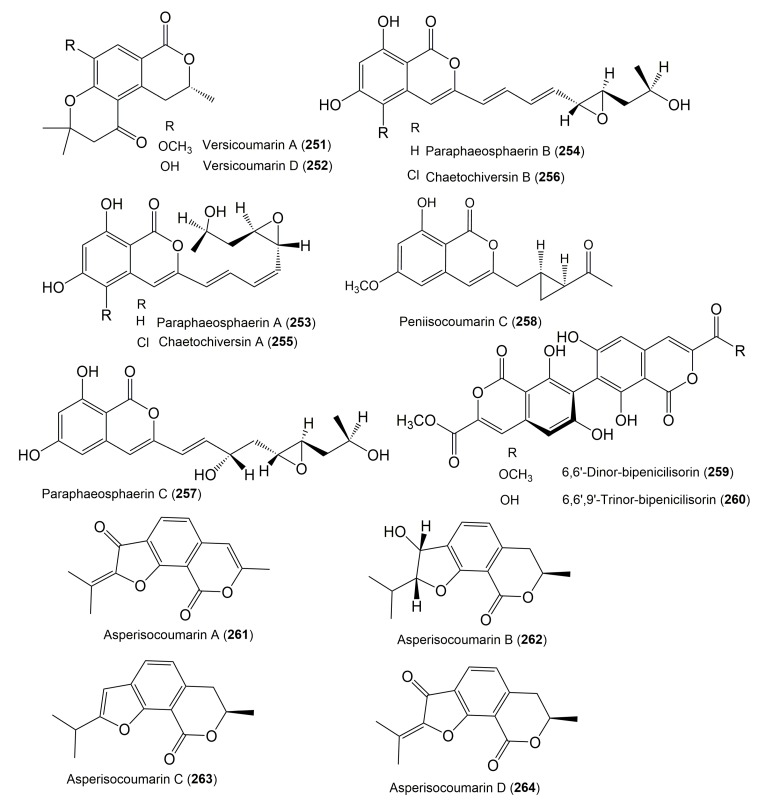

Figure 25.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 251–264.

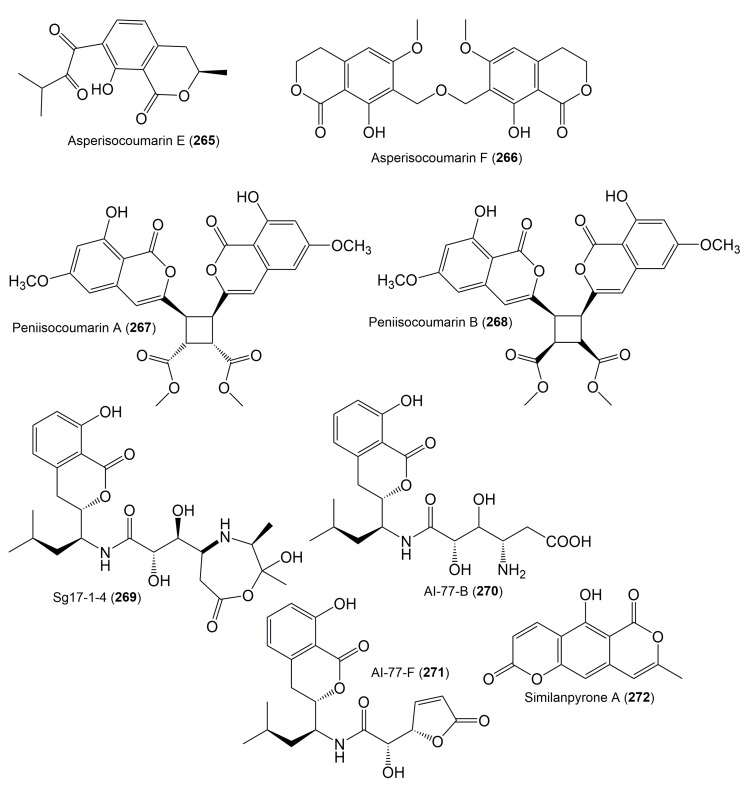

Figure 26.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 265–272.

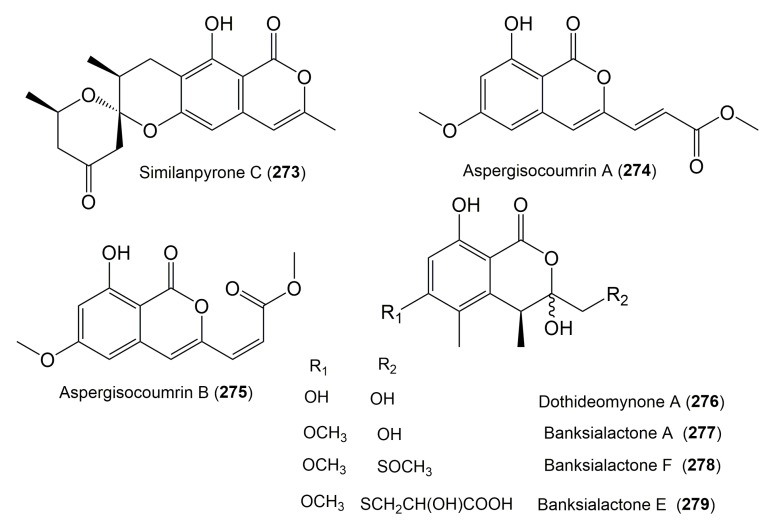

Figure 27.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 273–279.

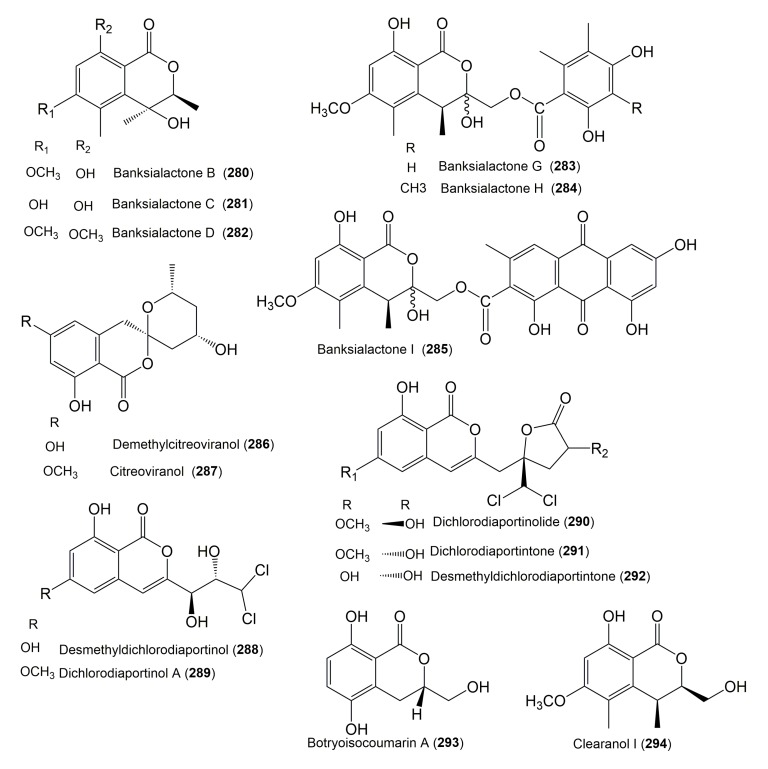

Figure 28.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 280–294.

Figure 29.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 295–300.

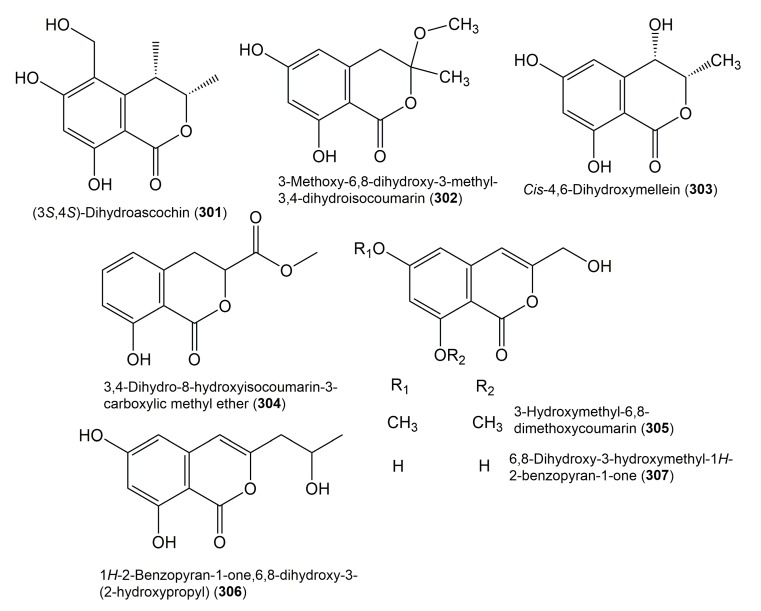

Figure 30.

Structures of isocoumarin derivatives 301–307.

It is hoped that by using these figures in conjunction with the trivial name, fungal source, host, and place (Table 1) the readers will be able to locate key references in the literature and gain much understanding of the fascinating chemistry of these metabolites. Many of these derivatives have substituents at C-3, which could be one carbon or more. The majority of them have an oxygen atom at C-8 and some have the C-6 oxygen. Further alkylation or oxygenation may occur at the remaining positions of the isocoumarin skeleton. Isocoumarins with 3,4-, 4,5-, 5,6-, 6,7-, and 7,8-fused carbocyclic rings are reported. Some of the reported derivatives have chlorine (e.g., 9, 12, 22, and 28–31) or bromine (e.g., 23, 27, 32, and 33) atom at C-5 and/or C-7. Some show sugar moieties such as glucose (e.g., 15, 77–79, and 151) and ribose moiety (e.g., 78 and 79). In addition, some isocoumarins dimers are reported (e.g., 259, 260, and 266–268). Moreover, some linked to other moieties such as anthraquinone and indole diketopiperazine (e.g., 285 and 296) or contain sulphur (e.g., 278 and 279) or nitrogen (e.g., 269–271) substituents. This review also mentions briefly their isolation, structural characterization, biosynthesis, and bioactivities (Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35, Table 2 and Table 3). Strengthening of their bioactivities may draw the attention of medicinal and synthetic chemists for designing new agents using the known isocoumarins derivatives as raw materials and the discovery of new therapeutic properties not yet attributed to known compounds. The published literature search was conducted over various databases: Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, SpringerLink, ACS Publications, Wiley, Taylor and Francis, and Sci-Finder using the keywords (isocoumarin, endophytes, and biological activities).

Table 1.

List of fungal isocoumarins (Fungal source, host, and place).

| Compound Name | Fungus | Host (Part, Family) | Source, Place | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kigelin (1) (−)-(3R)-6,7-Dimethoxymellein |

Aspergillus terrus BDKU 1164 | Marine alga | Mubarak village beach, Karachi, Pakistan | [68] |

| (3R,4R)-6,7-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxymellein (2) | Aspergillus terrus BDKU 1164 | Marine alga | Mubarak village beach, Karachi, Pakistan | [68] |

| 8-Methoxymellein (3) | Penicillium sp.1 and sp.2 | Alibertia macrophylla (Leaves, Rubiaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, São Paulo, Brazil | [18] |

| Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Daya Bay, Shenzhen, China | [36] | |

| Xylaria cubensis BCRC 09F 0035 | Litsea akoensis Hayata (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | [109] | |

| Cis-4-Acetoxyoxymellein (4) | Ascomycete 6650 | Meliotus dentatus (Leaves, Fabaceae) | Baltic Sea, Ahrenshoop, Germany | [50] |

| 8-Deoxy-6-hydroxy-cis-4-acetoxyoxymellein (5) | Ascomycete 6650 | Meliotus dentatus (Leaves, Fabaceae) | Baltic Sea, Ahrenshoop, Germany | [50] |

| (3R,4R)-(−)-4-Hydroxymellein (3R,4R)-Cis-4-Hydroxymellein (6) |

Aspergillus terrus (BDKU 1164) | Marine alga | Mubarak village beach, Karachi, Pakistan | [68] |

| Xylaria sp. PBR-30 | Sandoricum koetjape (Leaves, Meliaceae) | Prachinburi Province, Thailand | [111] | |

| Ascochyta sp. | Meliotus dentatus (Whole plant, Fabaceae) | Shores of the Baltic Sea, near Ahrenshoop, Germany | [117] | |

| Nigrospora sp. PSU-N24 | Garcinia nigrolineata (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Ton Nga Chang wildlife sanctuary, Songkhla province, Southern Thailand | [110] | |

| Neofusicoccum parvum | Vitis vinifera L. (Cankered branchs, Vitaceae) | Catalonia, NE Spain | [114] | |

| Emericellopsis minima | Hyrtios erecta (Marine sponge) | Similan islands, Phag Nga Province, Thailand | [92] | |

| Apiospora montagnei Sacc. | Smallanthus sonchifolius (Roots, Asteraceae) | Ribeirão Preto city, S. P. State, Brazil | [113] | |

| Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] | |

| Annulohypoxylomarin (7) | Annulohypoxylon truncatum | Zizania caduciflora (Leaves, Poaceae) | Suncheon, South Korea | [45] |

| 5-Hydroxymellein (8) | Penicillium sp.1 and sp.2 | Alibertia macrophylla (Leaves, Rubiaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, São Paulo, Brazil | [18] |

| Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] | |

| (3R)-6-Methoxy-7-chloromellein (9) | Phoma sp. 135 | Ectyplasia perox | Lauro Club Reef, Dominica | [32] |

| (3R,4R)-Cis-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (10) | Unidentified Ascomycete 6650 | Meliotus dentatus (Leaves, Fabaceae) | Baltic Sea, Ahrenshoop, Germany | [43] |

| (−)-6-Methoxymellein (11) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Phoma sp. YE3135 | Aconitum vilmorinianum (Roots, Ranunculaceae) | Yunnan University, China | [26] | |

| (3R,4S)-4-Hydroxy-6-methoxy-7-chloromellein (12) | Phoma sp. 135 | Ectyplasia perox | Lauro Club Reef, Dominica | [32] |

| Botryospyrone C (13) | Botryosphaeria ramosa L29 | Myoporum bontioides (Leaves, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, China | [71] |

| Botryospyrone D (14) | Botryosphaeria ramosa L29 | Myoporum bontioides (Leaves, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, China | [71] |

| 3R-(+)-5-O-[6′-O-Acetyl]-α-D-glucopyranosyl-5-hydroxymellein (15) | Xylaria sp. cfcc 87468 | Pinus tabuliformis (Leaves, Pinaceae) | China Forestry Culture Collection Center, Beijing, China | [118] |

| 6-(4′-Hydroxy-2′-methyl phenoxy)-(−)-(3R)-mellein (16) | Aspergillus terrus BDKU 1164 | Marine alga | Mubarak village beach, Karachi, Pakistan | [68] |

| (3R)-7-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (17) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Biscogniauxia capnodes | Averrhoa carambola L. (Fruits, Oxalidaceae) | Home garden in Kandy, Central Province, Sri Lanka | [96] | |

| Akolitserin (18) (+)-(3R,4S)-5-Carbomethoxy-3-hydroxymellein Methyl (3R,4S)-3,4-Dihydro-4,8-dihydroxy-3-methyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-5-carboxylate |

Xylaria cubensis BCRC 09F 0035 | Litsea akoensis Hayata (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | [109] |

| (−)-(R)-5-(Methoxycarbonyl)mellein (19) | Xylaria cubensis BCRC 09F 0035 | Litsea akoensis Hayata (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | [109] |

| (3R*,4S*)-6,8-Dihydroxy-3,4,7-trimethylisocoumarin (20) | Penicillium sp. 091402 | Bruguiera sexangula (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Qinglan Port, Hainan, China | [87] |

| (3R,4S)-6,8-Dihydroxy-3,4,5,7-tetramethylisochroman (21) | Penicillium sp. 091402 | Bruguiera sexangula (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Qinglan Port, Hainan, China | [87] |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] | |

| (3R,4R)-5-Cholro-4,6-dihydroxymellein (22) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone A (23) (R)-5-Bromo-6-hydroxy-8-methoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone B (24) (R)-7-Bromo-6-hydroxy-8-methoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone C (25) (R)-7-Bromo-6,8-dimethoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone D (26) (R)-7-Bromo-6-hydroxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone E (27) (R)-5-Bromo-6,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone F (28) (R)-5-Cholro-6-hydroxy-8-methoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerone G (29) (R)-7-Cholro-6-hydroxy-8-methoxy-mellein |

Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| (R)-5-Cholro-6-hydroxymellein (30) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerin A (31) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerin B (32) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| Palmaerin D (33) | Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] |

| (3R,4R)-3,4-Dihydro-4,6-dihydroxy-3-methyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-5-carboxylic acid (34) | Xylaria sp. PA-01 | Piper aduncum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, Săo Paulo, Brazil | [17] |

| (3R)-Mellein (35) 3,4-Dihydro-(3R)-methyl-8-hydroxyisocoumarin |

Centraalbureau voor Schimmel 120379 | Picea glauca (Leaves, Pinaceae) | Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada | [119] |

| Nigrospora sp. PSU-N24 | Garcinia nigrolineata (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Ton Nga Chang wildlife sanctuary, Songkhla province, Southern Thailand | [119] | |

| Nigrospora sp. LLGLM003 | Moringa oleifera (Roots, Moringaceae) | Xiamen municipality, Fujian Province, China | [53] | |

| Apiospora montagnei Sacc. | Smallanthus sonchifolius (Roots, Asteraceae) | Ribeirão Preto city, S. P. State, Brazil | [113] | |

| Lasiodiplodia sp. ME4-2 | Viscum coloratum (Flowers, Santalaceae) | Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China | [120] | |

| Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] | |

| Penicillium janczewskii | Prumnopitys andina (Phloem, Podocarpaceae) | Western Andean slopes near Las Trancas, Chillan | [91] | |

| Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] | |

| (R)-7-Hydroxymellein (36) | Penicillium sp. 05070032-C | Alibertia macrophylla (Leaves, Rubiaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, Săo Paulo, Brazil | [17] |

| Xylaria cubensis BCRC 09F 0035 | Litsea akoensis Hayata (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | [109] | |

| (3R,4R)-4,7-Dihydroxymellein (37) | Penicillium sp. 05070032-C | Alibertia macrophylla (Leaves, Rubiaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, Săo Paulo, Brazil | [17] |

| Angelicoin A (38) | Aspergillus versicolor 0456 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [122] |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] | |

| Periplanetin A (39) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| (3R)-Methyl-8-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-7-methoxydihydroisocoumarin (40) | Aspergillus versicolor | Nicotiana tabacum (Rhizomes, Solanaceae) | Chuxiong, Yunnan, China | [112] |

| (3R)-Methyl-7,8-dimethoxy-6-(hydroxymethyl) dihydro-isocoumarin (41) |

Aspergillus versicolor | Nicotiana tabacum (Rhizomes, Solanaceae) | Chuxiong, Yunnan, China | [112] |

| (R)-6-Hydroxymellein (42) | Aspergillus versicolor | Nicotiana tabacum (Rhizomes, Solanaceae) | Chuxiong, Yunnan, China | [112] |

| Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, | [51] | |

| Seltsamia galinsogisoli sp. nov. SYPF 7336 | Galinsoga parviflora (Whole plant, Asteraceae) | Huludao, China | [78] | |

| 6,8-Dimethoxy-3-methyl-3,4-dihydro-1H-isochromen-1-one (43) | Aspergillus versicolor | Nicotiana tabacum (Rhizomes, Solanaceae) | Chuxiong, Yunnan, China | [112] |

| Periplanetin B (44) | Aspergillus versicolor | Nicotiana tabacum (Rhizomes, Solanaceae) | Chuxiong, Yunnan, China | [112] |

| Arundinone A (45) | Microsphaeropsis arundinis | Ulmus macrocarpa (Stems, Ulmaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China | [123] |

| Aspergillspin F (46) | Aspergillus sp. SCSIO 41501 | Melitodes squamata (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | South China Sea, Sanya Hainan Province, China | [70] |

| (3R)-5-Carbomethoxymellein (47) 5-Carbomethyoxy-3,4-dihydro-8-hydroxy-(3R)-methylisocoumarin |

Centra albureau voor Schimmel cultures 120379 | Picea glauca (Leaves, Pinaceae) | Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada | [119] |

| Xylaria sp. PSU-G12 | Garcinia hombroniana (Branch, Clusiaceae) | Songkhla province, Thailand | [95] | |

| (3R)-5-Formylmellein (48) 3,4-Dihydro-5-formyl-8-hydroxy-(3R)-methylisocoumarin |

Centraalbureau voor Schimmel 120379 | Picea glauca (Leaves, Pinaceae) | Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada | [119] |

| Xylarellein (49) | Xylaria sp. PSU-G12 | Garcinia hombroniana (Branch, Clusiaceae) | Songkhla province, Thailand | [95] |

| (3R)-5-Carboxylmellein (50) | Xylaria sp. PSU-G12 | Garcinia hombroniana (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Songkhla province, Thailand | [95] |

| Gamahorin (51) | Pestalotiopsis heterocornis | Phakellia fusca (Sponge, Axinellidae | Xisha Islands, China | [75] |

| Versicoumarin B (52) | Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] |

| Versicoumarin C (53) | Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] |

| S-(−)-6-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-4-(1′-hydroxyethyl)-isocoumarin (54) | Talaromyces Amestolkiae YX1 | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Acetic acid 6,8-dihydroxy-3,5-dimethyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromen-4-ylmethyl ester (55) | Scytalidium sp. 5681 | Salix sp. (Leaves, Salicaceae) | Harz Mountains, Lower Saxony, Germany | [27] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-4-hydroxymethyl-3,5-dimethyl-isochromen-1-one (56) | Scytalidium sp. 5681 | Salix sp. (Leaves, Salicaceae) | Harz Mountains, Lower Saxony, Germany | [27] |

| Decarboxycitrinone (57) | Scytalidium sp. 5681 | Salix sp. (Leaves, Salicaceae) | Harz Mountains, Lower Saxony, Germany | [27] |

| 4-Acetyl-6,8-dihydroxy-5-methyl-2- benzopyran-1-one (58) | Scytalidium sp. 5681 | Salix sp. (Leaves, Salicaceae) | Harz Mountains, Lower Saxony, Germany | [27] |

| 6,8-Diacetoxy-3,5-dimethylisocoumarin (59) | Mycelia sterile 4567 | Canadian thistle Cirsium arvense (Asteraceae) | Lower Saxony, Germany | [20] |

| Penicilisorin (60) | Penicillium sclerotiorum PSUA13 | Garcinia atroviridis (Leaves, Clusiaceae) | Yala Province, Thailand | [124] |

| Pestalotiorin (61) | Pestalotiopsis sp. PSU-ES194 | Enhalus acoroides (Leaves, Hydrocharitaceae) | Songkla Province, Thailand | [41] |

| Tabaisocoumarin A (62) | Aspergillus versicolor 0456 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [122] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] | |

| 3-Acetoxyl-8-hydroxyl-isocoumarin (63) | Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] |

| 6-Hydroxy-4-(1-hydroxyethyl)-8-methoxy-1H-isochromen-1-one (64) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| S-(−)-5,6,8-Trihydroxy-4-(1′-hydroxyethyl)isocoumarin (65) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leave, Rhizophoraceae | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Sescandelin (66) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissue) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Terrecoumarin A (67) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| Terrecoumarin B (68) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| Terrecoumarin C (69) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| Pestapyrone D (70) | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Photinia frasery (Leaves, Amygdaloideae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | [22] |

| Pestapyrone E (71) | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Photinia frasery (Leaves, Amygdaloideae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | [22] |

| LL-Z 1640-7 (72) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Aspergillspin G (73) | Aspergillus sp. SCSIO 41501 | Melitodes squamata (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | South China Sea, Sanya Hainan Province, China | [70] |

| Acremonone E (74) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Acremonone F (75) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Acremonone G (76) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] | |

| Acremonone H (77) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Daldiniside B (78) | Daldinia eschscholzii | Scaevola sericea Vahl (Branches, Goodeniaceae) | Hainan province, China | [54] |

| Daldiniside C (79) | Daldinia eschscholzii | Scaevola sericea Vahl (Branches, Goodeniaceae) | Hainan province, China | [54] |

| de-O-Methyldiaporthin (80) | Daldinia eschscholzii | Scaevola sericea Vahl (Branches, Goodeniaceae) | Hainan province, China | [54] |

| Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] | |

| Myrothelactone A (81) | Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] |

| Myrothelactone B (82) | Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] |

| 3-Methyl-8-hydroxyisocoumarin (83) | Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-5-methoxy-3-methyl-1H-isochromen-1-one (84) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leave, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Myrothelactone C (85) | Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] |

| Myrothelactone D (86) | Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] |

| Tubakialactone B (87) 8-Hydroxyl-3,4-bis(hydroxymethyl)-6-methoxy-4-methyl-1H-2-benzopyran-1-one |

Tubakia sp. ECN-111 | Houttuynia cordata Thunb (Leaves, Saururaceae) | Chikusa-ku Nagoya city, Japan | [115] |

| Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] | |

| Saccharonol A (88) 6,8-Dihydroxy-3-methylisocoumarin |

Aspergillus similanensis sp. nov. KUFA 0013 | Rhabdermia sp. (Sponge, Rhabderemiidae) | Phang Nga Province, Thailand | [48] |

| Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Daya Bay, Shenzhen, China | [36] | |

| Aspergillus versicolor KJ801852 | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [126] | |

| Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] | |

| Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] | |

| Similanpyrone B (89) 6,8-Dihydroxy-3,7-dimethylisocoumarin |

Aspergillus similanensis sp. nov. KUFA 0013 | Rhabdermia sp. (Sponge, Rhabderemiidae) | Phang Nga Province, Thailand | [48] |

| Pestalotiopsis sp. HQD-6 | Rhizophora mucronata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [126] | |

| Reticulol (90) | Aspergillus similanensis sp. nov. KUFA 0013 | Rhabdermia sp. (Sponge, Rhabderemiidae) | Phang Nga Province, Thailand | [48] |

| Biscogniauxia capnodes | Averrhoa carambola L. (Fruits, Oxalidaceae) | Kandy, Central Province, Sri Lanka | [96] | |

| 6-Hydroxy-4-hydroxymethyl-8-methoxy-3-methylisocoumarin (91) | Endophytic fungus (No. GX4-1B) | Bruguiera gymnoihiza (L.) Savigny (Branch, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea in Guangxi province, China | [127] |

| 6-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-3,4-dimethylisocoumarin (92) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leave, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| 3,4-Dimethyl-6,8-dihydroxyisocoumarin (93) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Nectria pseudotrichia 120-1NP | Gliricidia sepium (Stems, Fabaceae) | Wanagama forest of Universitas, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | [128] | |

| 6-Hydroxy-4-hydroxymethyl-8-methoxy-3-methyl-isocoumarin (94) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Sescandelin B (95) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Myrothecium sp. OUCMDZ-2784 | Apocynum venetum (Leaves, Apocynaceae) | Dongying, China | [103] | |

| 6-Hydroxy-3-hydroxymethyl-8-methoxyisocoumarin (96) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| 4,6-Dihydroxy-3,9-dehydromellein (97) | Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] |

| Aspergillus versicolor KJ801852 | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [126] | |

| Banksiamarin A (98) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksiamarin B (99) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxyisocoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (100) | Bionectria sp. | Raphia taedigera (Seeds, Arecaceae) | Haut Plateaux region, Cameroon | [82] |

| Nectria pseudotrichia 120-1NP | Gliricidia sepium (Stem, Fabaceae) | Wanagama forest of Universitas, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | [128] | |

| Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius (Leaves, Acanthaceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China. | [73] | |

| Nectriapyrone A (101) | Nectria pseudotrichia 120-1NP | Gliricidia sepium (Stems, Fabaceae) | Wanagama forest of Universitas, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | [128] |

| Nectriapyrone B (102) | Nectria pseudotrichia 120-1NP | Gliricidia sepium (Stems, Fabaceae) | Wanagama forest of Universitas, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | [128] |

| 6-O-Methylreticulol (103) 8-Hydroxy-6,7-dimethoxy-3-methylisocoumarin |

Xylariaceae sp. QGS 01 | Quercus gilva Blume (Stems, Fagaceae) | EhimeUniversity Garden, Ehime Prefecture, Japan | [102] |

| Biscogniauxia capnodes | Averrhoa carambola L. (Fruits, Oxalidaceae) | Home garden in Kandy, Central Province, Sri Lanka | [96] | |

| 7-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethylisochromen-1-one (104) | Phoma sp. YE3135 | Aconitum vilmorinianum (Roots, Ranunculaceae) | Yunnan University, China | [26] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-3-hydroxymethylisocoumarin (105) | Aspergillus versicolor KJ801852 | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [126] |

| Botryospyrone A (106) | Botryosphaeria ramosa L29 | Myoporum bontioides (Leaves, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, China | [71] |

| Botryospyrone B (107) | Botryosphaeria ramosa L29 | Myoporum bontioides (Leaves, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, China | [71] |

| Decarboxyhydroxycitrinone (108) | Arthrinium sacchari | Unidentified sponge | The coast of Atami-shi, ShizuokaPrefecture, Japan | [90] |

| Tubakialactone A (109) 8-Hydroxyl-3- hydroxymethyl-6-methoxy-4-methyl-1H-2-benzopyran-1-one |

Tubakia sp. ECN-111 (Melanconidaceae) | Houttuynia cordata Thunb (Leaves, Saururaceae) | Chikusa-ku Nagoya city, Japan | [115] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-7-methyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-3-carboxylic acid (110) | Pestalotiopsis coffeae | Caryota mitis (Palm, Arecaceae) | Hainan Province, China | [129] |

| Oryzaein A (111) | Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] |

| Oryzaein B (112) | Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] |

| Caudacoumarin C (113) | Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] |

| 4,5,7-Trihydroxy-3-methoxy-3,6-dimethylisochroman-1-one (114) | Aspergillus sp. 16-5B | Sonneratia apetala (Leaves, Lythraceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve in Hainan Island, China | [38] |

| 5,7-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-3,6-dimethylisochromane-1,4-dione (115) | Aspergillus sp. 16-5B | Sonneratia apetala (Leaves, Lythraceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve in Hainan Island, China | [38] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-3,6,8-trihydroxy-3,5-dimethylisocoumarin (116) | Mycelia sterile 4567 | Canadian thistle Cirsium arvense (Asteraceae) | Lower Saxony, Germany | [20] |

| Tenuissimasatin (117) | Alternaria tenuissima | Erythrophleum fordii (Barks, Fabaceae) | Nanning, Guangxi Province, China | [130] |

| Penicoffrazin B (118) | Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] |

| Penicoffrazin C (119) | Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy-3,7-dimethylisochroman-1-one (120) | Pestalotiopsis coffeae | Caryota mitis (Palm, Arecaceae) | Hainan Province, China | [129] |

| Acremonone B (121) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Acremonone C (122) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| Acremonone D (123) | Acremonium sp. PSU-MA70 | Rhizophora apiculata (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Satun Province, Thailand | [125] |

| 4-Acetyl-3,4-dihydro-6,8,-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-5-methylisocoumarin (124) | Mycelia sterile 4567 | Canadian thistle Cirsium arvense (Asteraceae) | Lower Saxony, Germany | [20] |

| 4-Acetyl-3,4-dihydro-6,8-dihydroxy-5-methylisocoumarin (125) | Mycelia sterile 4567 | Canadian thistle Cirsium arvense (Asteraceae) | Lower Saxony, Germany | [20] |

| Phomolactone A (126) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] | |

| Phomolactone B (127) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] | |

| Phomolactone C (128) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| (3R)-3-hydroxymethyl-8-hydroxyl-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (129) | Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] |

| 8-Methylmellein (130) | Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] |

| Pestalotiopsis sp. HHL101 | Rhizophora stylosa (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Dong Zhai Gang-Mangrove Garden, Hainan Island, China | [72] | |

| Trans-4-hydroxymellein (131) | Penicillium sp.1 and sp.2 | Alibertia macrophylla (Leaves, Rubiaceae) | Mogi-Guaçu, São Paulo, Brazil | [18] |

| Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae), | Daya Bay, Shenzhen, China | [36] | |

| Sarcosomataceae sp. NO.49-14-2-1 | Everniastrum nepalense (Taylor) Hale ex Sipman (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Panzhihua, Sichuan province, China | [121] | |

| Lachnum palmae | Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Linzhou Country of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China | [51] | |

| 3,5-Dimethyl-8-hydroxy-7-methoxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (132) | Cytospora eucalypticola SS8 | Eucalyptus perriniana (Bark, Myrtaceae) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom | [55] |

| 3,5-dimethyl-8-methoxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (133) | Cytospora eucalypticola SS8 | Eucalyptus perriniana (Barks, Myrtaceae) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom | [55] |

| (3R)-5-Methylmellein (134) 3,4-Dihydro-(3R),5-dimethyl-8-hydroxyisocoumarin |

Cytospora eucalypticola SS8 | Eucalyptus perriniana (Barks, Myrtaceae) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom | [55] |

| Centraalbureau voor Schimmel cultures (120379) | Picea glauca (Leaves, Pinaceae) | Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada | [119] | |

| Xylaria sp. PSU-G12 | Garcinia hombroniana (Branchs, Clusiaceae) | Songkhla province, Thailand | [95] | |

| Xylaria cubensis (Xylariaceae) BCRC 09F 0035 | Litsea akoensis Hayata (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | [109] | |

| Biscogniauxia capnodes | Averrhoa carambola L. (Fruits, Oxalidaceae) | Home garden in Kandy, Central Province, Sri Lanka | [96] | |

| 5-Hydroxymethylmellein (135) 8-Hydroxy-5-hydroxymethyl-3-methyl-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin |

Cytospora eucalypticola SS8 | Eucalyptus perriniana (Barks, Myrtaceae) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom | [55] |

| 4,8-Dihydroxy-3,5-dimethyl-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (136) | Cytospora eucalypticola SS8 | Eucalyptus perriniana (Barks, Myrtaceae) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom | [55] |

| Periplanetin D (137) | Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, People’sRepublic of China, | [93] |

| Penicillium oxalicum 0403 | Nicotiana sanderae (Leaves, Solanaceae) | Shilin, Yunnan Province, China | [44] | |

| Pestalotiopsis coffeae | Caryota mitis (Palm, Arecaceae) | Hainan Province, China | [129] | |

| Pestalactone C (138) | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Photinia frasery (Leaves, Amygdaloideae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | [22] |

| (4S) (+)-Ascochin (139) | Ascochyta sp. | Meliotus dentatus (Whole plant, Fabaceae) | Shores of the Baltic Sea, near Ahrenshoop, Germany | [117] |

| (4S)-Thielavic acid (140) | Thielavia sp. ECN-115 | Crassula ovata (Stems, Crassulaceae) | Chikusa-ku Nagoya city, Japan | [115] |

| Phomasatin (141) | Phoma sp. YN02-P-3 | Sumbaviopsis albicans J. J. Smith (Leaves, Euphorbiaceae) | Yunnan, China | [84] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-6-methoxy-8-hydroxy-3,4,5-trimethyl-isocoumarin-7-carboxylic acid methyl ester (142) | Fungus dz17 | Mangrove plant | South China Sea coast, China | [88] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-4,8-dihydroxy-3,5-dimethylisocoumarin (143) | Fungus dz17 | Mangrove plant | South China Sea coast, China | [88] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-8-hydroxy-3-methylisocoumarin-5-carboxylic acid (144) | Fungus dz17 | Mangrove plant | South China Sea coast, China | [88] |

| Pestalotiopisorin B (145) | Pestalotiopsis sp. HHL101 | Rhizophora stylosa (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | Dong Zhai Gang-Mangrove Garden, Hainan Island, China | [72] |

| Pestaloisocoumarin A (146) | Pestalotiopsis heterocornis | Phakellia fusca (Sponge, Axinellidae | Xisha Islands, China | [75] |

| Pestaloisocoumarin B (147) | Pestalotiopsis heterocornis | Phakellia fusca (Sponge, Axinellidae | Xisha Islands, China | [75] |

| Tubakialactone C (148) (R)-3,4-Dihydro-4,8-dihydroxy-6-methoxy-4-methyl-3-methylene-1H-2-benzopyran-1-one |

Tubakia sp. ECN-111 (Melanconidaceae) | Houttuynia cordata Thunb (Leaves, Saururaceae) | Chikusa-ku Nagoya city, Japan | [115] |

| (R)-3,4-dihydro-4-hydroxyl-6,8-dimethoxy-4-methyl-3-methylene-1H-2-benzopyran-1-one (149) | Tubakia sp. ECN-111 | Houttuynia cordata Thunb (Leaves, Saururaceae) | Chikusa-ku Nagoya city, Japan | [115] |

| (6,8-dihydroxy-3-methyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromen-4-yl)methyl-3-methylbutanoate (150) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Penicimarin D (151) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Penicimarin E (152) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Penicimarin F (153) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Aspergillus versicolor KJ801852 | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [126] | |

| Penicimarin G (154) | Penicillium citrinum HL-5126 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, P.R. China | [56] |

| Penicimarin H (155) | Penicillium citrinum HL-5126 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [56] |

| Penicimarin I (156) | Penicillium citrinum HL-5126 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [56] |

| Penicisimpin A (157) 3-(R)-6,8-Dihydroxy-7-methyl-3-pentylisochroman-1-one |

Penicillium simplicissimum MA-332 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [58] |

| Penicisimpin B (158) 3-(R)-6,8-Dihydroxy-3-pentylisochroman-1-one |

Penicillium simplicissimum MA-332 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [58] |

| Penicisimpin C (159) 3-(S)-6,8-Dihydroxy-7-methyl-3-(pent-1-enyl)isochroman-1-one |

Penicillium simplicissimum MA-332 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [58] |

| Fusarentin 6-methyl ether (160) | Colletotrichum sp. CRI535-02 | Piper ornatum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Tai Rom Yen National Park, Surat Thani Province, Thailand | [80] |

| Fusarentin 6,7-dimethyl ether (161) | Colletotrichum sp. CRI535-02 | Piper ornatum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Tai Rom Yen National Park, Surat Thani Province, Thailand | [80] |

| 7-Butyl-6,8-dihydroxy-3(R)-pent-11-enylisochroman-1-one (162) | Geotrichum sp. | Crassocephalum crepidioides S. Moore (Stems, Asteraceae) | Songkhla Province, Southern Thailand | [74] |

| 7-But-15-enyl-6,8-dihydroxy-3(R)-pent-11-enylisochroman-1-one (163) | Geotrichum sp. | Crassocephalum crepidioides S. Moore (Stems, Asteraceae) | Songkhla Province, Southern Thailand | [74] |

| 7-Butyl-6,8-dihydroxy-3(R)-pentylisochroman-1-one (164) | Geotrichum sp. | Crassocephalum crepidioides S. Moore (Stems, Asteraceae) | Songkhla Province, Southern Thailand | [74] |

| Monocerin (165) | Microdochium bolleyi 8880 | Fagonia cretica (Leaves, Zygophyllaceae) | Gomera, Spain. | [49] |

| Exserohilum rostratum EU571210 | Stemona sp. (Leaves and roots, Stemonaceae) | Amphur Bangban, Ayutthaya Province, Thailand | [46] | |

| Colletotrichum sp. CRI535-02 | Piper ornatum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Tai Rom Yen National Park, Surat Thani Province, Thailand | [80] | |

| Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Daya Bay, Shenzhen, China | [36] | |

| Exserohilum rostratum ER1.1 | Bauhinia guianensis (Fabaceae) | Embrapa Amazônia Oriental Belém, Brazil | [59] | |

| Leptosphaena maculans | Osmanthus fragrans (Leaves, Oleaceae) | China | [104] | |

| 7-O-Demethylmonocerin (166) | Colletotrichum sp. CRI535-02 | Piper ornatum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Tai Rom Yen National Park, Surat Thani Province, Thailand | [80] |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Xuwen, Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| (12R)-Hydroxymonocerin (167) | Microdochium bolleyi 8880 | Fagonia cretica (Leaves, Zygophyllaceae) | Gomera, Spain | [49] |

| Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China. | [60] | |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| Leptosphaena maculans | Osmanthus fragrans (Leaves, Oleaceae) | China | [104] | |

| (11R)-Hydroxymonocerin (168) | Exserohilum rostratum EU571210 | Stemona sp. (Leaves and roots, Stemonaceae) | Amphur Bangban, Ayutthaya Province, Thailand | [46] |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| (12S)-Hydroxymonocerin (169) | Microdochium bolleyi 8880 |

Fagonia cretica (Leaves, Zygophyllaceae) | Gomera, Spain. | [49] |

| Exserolide D (170) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China. | [60] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] | |

| Exserolide E (171) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China. | [60] |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| Exserolide I (172) | Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] |

| Exserolide J (173) | Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] |

| Maculansline D (174) Isomer of (12R)-12-hydroxymonocerin |

Leptosphaena maculans | Osmanthus fragrans (Leaves, Oleaceae) | China | [104] |

| Exserolide A (175) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China. | [60] |

| Exserolide B (176) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China. | [60] |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| Exserolide C (177) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China | [60] |

| Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] | |

| Exserolide K (178) | Setosphaeria sp. SCSIO41009 | Callyspongia sp. (Sponge, Callyspongiidae) | Guangdong Province, China | [64] |

| Pestalactone A (179) | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Photinia frasery (Leaves, Amygdaloideae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | [22] |

| Pestalactone B (180) | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Photinia frasery (Leaves, Amygdaloideae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | [22] |

| 8-Dihydroramulosin (181) | Nigrospora sp. PSU-N24 | Garcinia nigrolineata (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Ton Nga Chang wildlife sanctuary, Songkhla province, Southern Thailand | [110] |

| Nigrospora sp. LLGLM003 | Moringa oleifera (Roots, Moringaceae) | Xiamen municipality, Fujian Province, China | [53] | |

| 6β-Hydroxy-8-dihydroramulosin (182) | Nigrospora sp. PSU-N24 | Garcinia nigrolineata (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Ton Nga Chang wildlife sanctuary, Songkhla province, Southern Thailand | [110] |

| (−) Ramulosin (183) | Talaromyces sp. JQ769262 | Cedrus deodara (Twigs, Pinaceae) | Lolab Valley in the Western Himalayas, Kashmir, India | [83] |

| (3S,4aR,7S)-7,8-Dihydroxy-3-methyl-3,4,10,5,6,7-hexahydro-1H-isochromen-1-one (184) | Talaromyces sp. JQ769262 | Cedrus deodara (Twigs, Pinaceae) | Lolab Valley in the Western Himalayas, Kashmir, India | [83] |

| 6-Hydroxyramulosin (185) | Nigrospora sp. PSU-N24 | Garcinia nigrolineata (Branches, Clusiaceae) | Ton Nga Chang wildlife sanctuary, Songkhla province, Southern Thailand | [110] |

| Peniciisocoumarin A (186) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Peniciisocoumarin B (187) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Alternariol (188) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Alternaria tenuissima SP-07 | Salvia przewalskii (Roots, Lamiaceae) | Longxi County, Gansu Province, China | [57] | |

| Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] | |

| Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] | |

| Alternariol-5-O-methyl ether (189) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Alternaria tenuissima SP-07 | Salvia przewalskii (Roots, Lamiaceae) | Longxi County, Gansu Province, China | [57] | |

| Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] | |

| Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] | |

| 3′-Hydroxyalternariol 5-O-methyl ether (190) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Alternariol 5-O-sulfate (191) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Alternariol 5-O-methyl ether-4′-O-sulfate (192) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Altenuene (193) | Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] |

| Alternaria tenuissima SP-07 | Salvia przewalskii (Roots, Lamiaceae) | Longxi County, Gansu Province, China | [57] | |

| Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] | |

| (−)-(2R,3R,4aR)-Altenuene-2-acetoxy ester (+)-(2S,3S,4aS)-Altenuene-2-acetoxy ester (194) | Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] |

| (−)-(2R,3R,4aR)-Altenuene-3-acetoxy ester (+)-(2S,3S,4aS)-Altenuene-3-acetoxy ester (195) | Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] |

| 5′-Epialtenuene (196) | Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] |

| Alternaria sp. II2L4 | Polygonum senegalense Meisn. (Leaves, Polygonaceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [40] | |

| Cycloepoxylactone (197) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| EI-1941-2 (198) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Cycloepoxytriol A (199) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Cycloepoxytriol B (200) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| Exserolide F (201) | Exserohilum sp. KJ156361 | Acer truncatum (Leaves, Sapindaceae) | Dongling Mountain, Beijing, China | [60] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz. (Rhizomes, Liliaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [94] | |

| Isocitreoisocoumarinol (202) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| (+)-Citreoisocoumarin (203) | Ampelomyces sp. EU143251. | Urospermum picroides (Flowers, Asteraceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [39] |

| Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] | |

| Nectria sp. HN001 | Sonneratia ovata (Branches, Lythraceae) | South China Sea in Hainan province, China | [33] | |

| Phoma sp. TA07-1 | Dichotella gemmacea GX-WZ-2008003-4 (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | Weizhou coral reef, South China Sea, China | [131] | |

| Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] | |

| (+)-6-Methylcitreoisocoumarin (204) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. sponge (Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] | |

| Citreoisocoumarinol (205) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Nectria sp. HN001 | Sonneratia ovata (Branches, Lythraceae) | South China Sea, Hainan province, China | [33] | |

| Phoma sp. (TA07-1) | Dichotella gemmacea GX-WZ-2008003-4 (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | Weizhou coral reef, South China Sea, China | [131] | |

| 12-epicitreoisocoumarinol (206) | Nectria sp. HN001 | Sonneratia ovata (Branches, Lythraceae) | South China Sea, Hainan province, China | [33] |

| Mucorisocoumarin A (207) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Mucorisocoumarin B (208) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] | |

| Peyroisocoumarin A (209) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Peyroisocoumarin B (210) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Peyroisocoumarin C (211) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Aspergillumarin A (212) | Aspergillus sp. | Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea coast, China | [61] |

| Penicillium sp. (MWZ14-4) | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] | |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Penicillium citrinum HL-5126 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Roots, Rhizophoraceae) | Hainan Island, China | [56] | |

| Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] | |

| Aspergillumarin B (213) | Aspergillus sp. | Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea coast, China | [61] |

| Penicillium sp. (MWZ14-4) | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] | |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Penicimarin B (214) | Penicillium sp. (MWZ14-4) | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Penicimarin C (215) | Penicillium sp. (MWZ14-4) | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] | |

| Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] | |

| (R)-3-((R)-4,5-Dihydroxypentyl)-8-hydroxyisochroman-1-one (216) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| 5,6-Dihydroxy-3-(4-hydroxypentyl)isochroman-1-one (217) | Talaromyces amestolkiae | Kandelia obovata (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China | [62] |

| Maculansline C (218) 3S, 10S-Dihydroisocoumarin, (Epimer) |

Leptosphaena maculans | Osmanthus fragrans (Leaves, Oleaceae) | China | [104] |

| Desmethyldiaportinol (219) | Ampelomyces sp. EU143251. | Urospermum picroides (Flowers, Asteraceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [39] |

| Phoma sp. (TA07-1) | Dichotella gemmacea GX-WZ-2008003-4 (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | Weizhou coral reef, South China Sea, China | [131] | |

| Dichlorodiaportin (220) | Trichoderma sp. 09 | Myoporum bontioides (Roots, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China | [66] |

| Trichoderma sp. 09 | Myoporum bontioides (Roots, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China | [66] | |

| Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] | |

| Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius (Leaves, Acanthaceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China | [73] | |

| Desmethyldichlorodiaportin (221) | Ampelomyces sp. EU143251. | Urospermum picroides (Flowers, Asteraceae) | Alexandria, Egypt | [39] |

| Peniisocoumarin D (222) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruit, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin E (223) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin F (224) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin G (225) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] | |

| Peniisocoumarin H (226) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin I (227) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin J (228) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| 3-[(R)-3,3-Dichloro-2-hydroxypropyl]-8-hydroxy-6-methoxy-1H-isochromen-1-one (229) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| (+)-Diaporthin (230) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Diaportinol (231) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Trichoderma sp. 09 | Myoporum bontioides (Roots, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China | [66] | |

| Phoma sp. (TA07-1) | Dichotella gemmacea GX-WZ-2008003-4 (Gorgonian, Plexauridae) | Weizhou coral reef, South China Sea, China | [131] | |

| Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] | |

| (+)-(10R)-7-Hydroxy-3-(2-hydroxy-propyl)-5,6-dimethylisochromen-1-one (232) | Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] |

| Peyroisocoumarin D (233) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Orthosporin (234) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| 8-Methyl-11-chlorodiaporthin (235) | Aspergillus sp. CPCC 400810 | Cetrelia sp. (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Laojun Mount in Yunnan Province, China | [29] |

| 8-Methyl-11,11-dichlorodiaporthin (236) | Aspergillus sp. CPCC 400810 | Cetrelia sp. (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Laojun Mount in Yunnan Province, China | [29] |

| 8-Hydroxy-6-methoxy-3-(2,3,3-trihydroxypropyl)-1H-isochromen-1-one (237) | Penicillium funiculosum Fes1711 | Ficus elastica (Leaves, Moraceae) | Liaocheng University Arboretum, Liaocheng, Shandong, China | [69] |

| 8-Hydroxy-6-methoxy-3-(1,2,3-trihydroxypropyl)-1H-isochromen-1-one (238) | Penicillium funiculosum Fes1711 | Ficus elastica (Leaves, Moraceae) | Liaocheng University Arboretum, Liaocheng, Shandong, China | [69] |

| Aspergisocoumrin C (239) | Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius (Leaves, Acanthaceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China | [73] |

| (3R,4R,10R)-Fusarentin 4-hydroxy-6,7-dimethyl ether (240) | Microdochium bolleyi 8880 | Fagonia cretica (Leaves, Zygophyllaceae) | Gomera, Spain | [49] |

| Colletotrichum sp. CRI535-02 | Piper ornatum (Leaves, Piperaceae) | Tai Rom Yen National Park, Surat Thani Province, Thailand | [80] | |

| Colletomellein A (241) | Colletotrichum aotearoa BCRC 09F0161 | Bredia oldhamii Hook. f. (Leaves, Melastomataceae) | Mutan, Pingtung County, Taiwan | [132] |

| Colletomellein B (242) | Colletotrichum aotearoa BCRC 09F0161 | Bredia oldhamii Hook. f. (Leaves, Melastomataceae) | Mutan, Pingtung County, Taiwan | [132] |

| Peniciisocoumarin D (243) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Peniciisocoumarin F (244) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Peniciisocoumarin H (245) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-8-hydroxy-6-methoxy-(3R)-propylisocoumarin (246) | Centraalbureau voor Schimmel cultures (120379) | Picea glauca (Leaves, Pinaceae) | Sussex, New Brunswick, Canada | [119] |

| Peniciisocoumarin C (247) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Peniciisocoumarin E (248) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Peniciisocoumarin G (249) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| (R)-3-(3-Hydroxypropyl)-8-hydroxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (250) | Penicillium sp. TGM112 | Bruguiera sexangula var. rhynchopetala (Leaves, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, China | [67] |

| Versicoumarin A (251) | Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Stearn (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [93] |

| Versicoumarin D (252) | Aspergillus versicolor | Paris marmorata Steam (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [89] |

| Paraphaeosphaerin A (253) | Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata | Opuntia leptocaulis (Rhizosphere, Cactaceae) | Tucson, Arizon | [133] |

| Paraphaeosphaerin B (254) | Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata | Opuntia leptocaulis (Rhizosphere, Cactaceae) | Tucson, Arizon, America | [133] |

| Chaetochiversin A (255) | Chaetomium chiversii | Ephedra fasciculata (Stems, Ephedraceae) | South mountain park, Phoenix, Arizona, America | [133] |

| Chaetochiversin B (256) | Chaetomium chiversii | Ephedra fasciculata (Stems, Ephedraceae) | South mountain park, Phoenix, Arizona, America | [133] |

| Paraphaeosphaerin C (257) | Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata | Opuntia leptocaulis (Rhizosphere, Cactaceae) | Tucson, Arizon, America | [133] |

| Peniisocoumarin C (258) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China. | [31] |

| 6,6′-Dinor-bipenicilisorin (259) | Aspergillus versicolor KU258497 | Eichhornia crassipes (Leaves, Pontederiaceae) | Mansoura, Egypt | [81] |

| 6,6′,9′-Trinor-bipenicilisorin (260) | Aspergillus versicolor KU258497 | Eichhornia crassipes (Leaves, Pontederiaceae) | Mansoura, Egypt | [81] |

| Asperisocoumarin A (261) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Asperisocoumarin B (262) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Asperisocoumarin C (263) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Asperisocoumarin D (264) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Asperisocoumarin E (265) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Asperisocoumarin F (266) | Aspergillus sp. 085242 | Acanthus ilicifolius (Roots, Acanthaceae) | Shankou Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [76] |

| Peniisocoumarin A (267) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruit, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Peniisocoumarin B (268) | Penicillium commune QQF-3 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Guangdong Province, China | [31] |

| Sg17-1-4 (269) | Alternaria tenuis Sg17-1 | Marine alga | Zhoushan Island, Zhejiang Province, China | [85] |

| AI-77-B (270) | Alternaria tenuis Sg17-1 | Marine alga | Zhoushan Island, Zhejiang Province, China | [85] |

| AI-77-F (271) | Alternaria tenuis Sg17-1 | Marine alga | Zhoushan Island, Zhejiang Province, China | [85] |

| Similanpyrone A (272) 5-Hydroxy-8-methyl-2H,6H-pyrano [3,4-g]chromen-2,6-dione |

Aspergillus similanensis sp. nov. KUFA 0013 | Rhabdermia sp. (Sponge, Rhabderemiidae) | Phang Nga Province, Thailand | [48] |

| Similanpyrone C (273) | Aspergillus similanensis KUFA 0013 | Rhabdermia sp. (Sponge, Rhabderemiidae) | Phang Nga Province, Thailand | [28] |

| Aspergisocoumrin A (274) | Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius (Leaves, Acanthaceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China | [73] |

| Aspergisocoumrin B (275) | Aspergillus sp. HN15-5D | Acanthus ilicifolius (Leaves, Acanthaceae) | Dongzhaigang Mangrove National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China. | [73] |

| Dothideomynone A (276) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone A (277) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone F (278) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone E (279) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone B (280) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone C (281) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone D (282) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone G (283) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone H (284) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Banksialactone I (285) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Demethylcitreoviranol (286) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Citreoviranol (287) | Peyronellaea glomerata XSB-01-15 | Amphimedon sp. (Sponge, Niphatidae) | Yongxin Island, Hainan Province, China | [65] |

| Desmethyldichlorodiaportinol (288) | Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] |

| Dichlorodiaportinol A (289) | Trichoderma sp., 09 | Myoporum bontioides (Roots, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China | [79] |

| Dichlorodiaportinolide (290) | Trichoderma sp. 09 | Myoporum bontioides (Roots, Scrophulariaceae) | Leizhou Peninsula, Guangdong Province, China | [66] |

| Dichlorodiaportintone (291) | Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] |

| Desmethyldichlorodiaportintone (292) | Ascomycota sp. CYSK-4 | Pluchea indica (Branches, Asteraceae) | Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve, Guangxi Province, China | [37] |

| Botryoisocoumarin A (293) 3S-5,8-dihydroxy-3-hydroxymethyldihydroisocoumarin |

Botryosphaeria sp. KcF6 | Kandelia candel (Fruits, Rhizophoraceae) | Daya Bay, Shenzhen, China | [36] |

| Clearanol I (294) | Aspergillus banksianus sp. nov | Banksia integrifolia (Leaves, Proteaceae) | Collaroy, New South Wales, Australia | [30] |

| Penicimarin A (295) | Penicillium sp. MWZ14-4 | Unidentified sponge GX-WZ-2008001 (Inner fresh tissues) | Weizhou, South China Sea, China | [52] |

| Isocoumarindole A (296) | Aspergillus sp. CPCC400810 | Cetrelia sp. (Lichen, Parmeliaceae) | Laojun Mount in Yunnan Province, China | [29] |

| Prochaetoviridin A (297) | Chaetomium globosum CDW7 (Chaetomiaceae) | Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgoaceae) | Jiangsu province, China | [77] |

| Fusariumin (298) | Fusarium sp. LN-10 | Melia azedarach (Leaves, Meliaceae) | Campus of Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi province, China, | [86] |

| Aspergillus versicolor KJ801852 | Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Rhizomes, Melanthiaceae) | Dali, Yunnan, China | [126] | |

| Phialophoriol (299) | Alternaria alternata | Camellia sinensis (Branches, Theaceae) | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China | [63] |

| (3aR,9bR)-6,9b-Dihydroxy-8-methoxy-1-methylcyclopentene[c]isochromen-3,5-dione (300) | Penicillium sp. | Riccardia multifida (L.) S. Gray (Liverwort, Aneuraceae) | Maoer Mountain, Guangxi Province, China | [116] |

| (3S,4S)-Dihydroascochin (301) | Phomopsis sp. 7233 | Laurus azorica (Leaves, Lauraceae) | Gomera, Spain | [42] |

| 3-Methoxy-6,8-dihydroxy-3-methyl-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (302) | Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] |

| Cis-4,6-Dihydroxymellein (303) | Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] |

| 3,4-Dihydro-8-hydroxyisocoumarin-3-carboxylic methyl ether (304) | Seltsamia galinsogisoli sp. nov. SYPF 7336 | Galinsoga parviflora (Whole plant, Asteraceae) | Huludao, China | [78] |

| 3-Hydroxymethyl-6,8-dimethoxycoumarin (305) | Endophytic fungus No. GX4-1B | Bruguiera gymnoihiza (L.) Savigny (Branches, Rhizophoraceae) | South China Sea, Guangxi province, China | [127] |

| 1H-2-Benzopyran-1-one,6,8-dihydroxy-3-(2-hydroxypropyl) (306) | Seltsamia galinsogisoli sp. nov. SYPF 7336 | Galinsoga parviflora (Whole plant, Asteraceae) | Huludao, China | [78] |

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-3-hydroxymethyl-1H-2-benzopyran-1-one (307) | Penicillium coffeae MA-314 | Laguncularia racemose (Leaves, Combretaceae) | Hainan island, China | [47] |

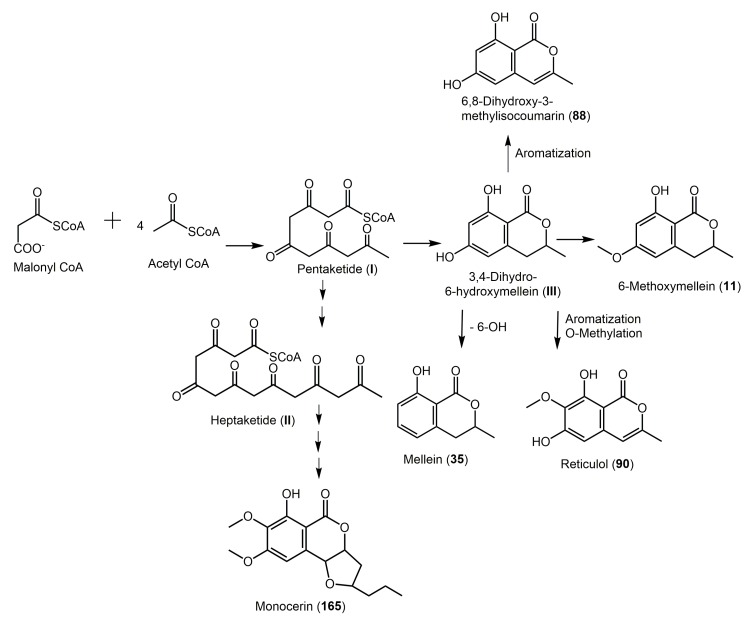

Figure 31.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 11, 35, 88, 90, and 165 [21,23,24,25,26].

Figure 32.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 56 and 125 [27].

Figure 33.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 273 [28].

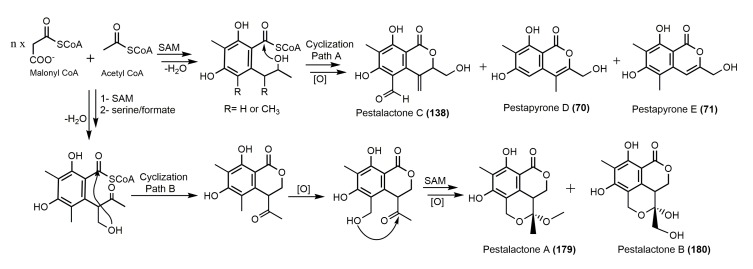

Figure 34.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 70, 71, 138, 179, and 180 [22].

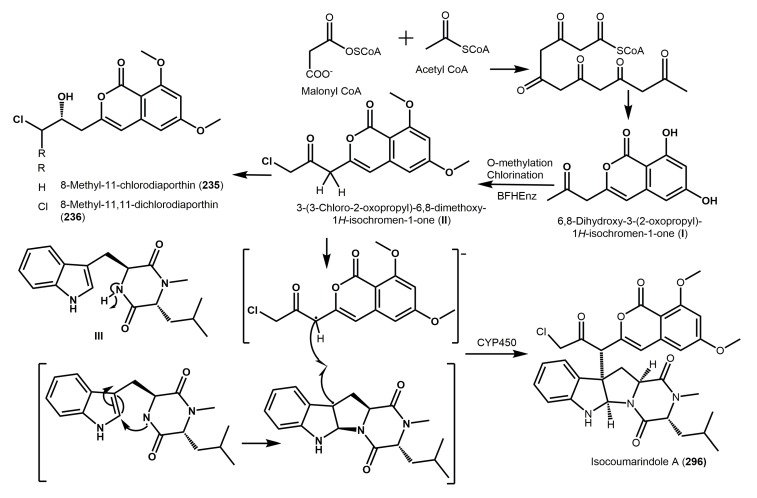

Figure 35.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 235, 236, and 296 [29].

Table 2.

Biological activities of the most active fungal isocoumarins.

| Compound Name | Biological Activity | Assay, Organism, or Cell Line | Biological Results | Positive Control | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kigelin (1) (−)-(3R)-6,7-Dimethoxymellein |

Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Trichophyton longifusus | 45 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 70 (% Inhibition) | [68] | |

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/A. flavus | 20 (% Inhibition) | Ampicillin 20 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Microsporum canis | 50 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 98.4 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| (3R,4R)-6,7-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxymellein (2) | Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Trichophyton longifusus | 70 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 70 (% Inhibition) | [68] | |

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Microsporum canis | 50 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 98.4 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Fusarium solani | 20 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 73.2 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| Antioxidant | XO Inhibition | 707 μM (IC50) | PG 628 μM (IC50) BHA 591 μM (IC50) |

[68] | ||

| Cis-4-Acetoxyoxymellein (4) | Antibacterial | Agar diffusion/E. coli | 10 mm (GI) | Penicillin 14 mm (GI) Tetracycline 18 mm (GI) |

[50] | |

| Antibacterial | Agar diffusion/Bacillus megaterium | 10 mm (GI) | Penicillin 18 mm (GI) Tetracycline 18 mm (GI) |

[50] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Microbotryum violaceum | 8 mm (GI) | Nystatin 20 mm (IZD) Actidione 50 mm (IZD) |

[50] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Septoria tritici | 8 mm (IZD) | [50] | |||

| Algicidal | Agar diffusion/Chlorella fusca | 7 mm (IZD) | Actidione 35 mm (IZD) | [50] | ||

| 8-Deoxy-6-hydroxy-cis-4-acetoxyoxymellein (5) | Antibacterial | Agar diffusion/E. coli | 9 mm (GI) | Penicillin 14 mm (GI) Tetracycline 18 mm (GI) |

[50] | |

| Antibacterial | Agar diffusion/Bacillus megaterium | 9 mm (GI) | Penicillin 18 mm (GI) Tetracycline 18 mm (GI) |

[50] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Microbotryum violaceum | 8 mm (GI) | Nystatin 20 mm (IZD) Actidione 50 mm (IZD) |

[50] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Botrytis cinerea | 10 mm (IZD) | Nystatin 0 mm (IZD) Actidione 0 mm (IZD) |

[50] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Septoria tritici | 9 mm (IZD) | [50] | |||

| Algicidal | Agar diffusion/Chlorella fusca | 8 mm (IZD) | Actidione 35 mm (IZD) | [50] | ||

| (3R,4R)-(−)-4-Hydroxymellein (3R,4R)-Cis-4-Hydroxymellein (6) |

Antibacterial | Agar diffusion/Bacillus megaterium | 6 mm (GI) | Penicillin 14 mm (GI) Tetracycline 18 mm (GI) |

[43] | |

| Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Microbotryum violaceum | 8 mm (IZD) | Nystatin 20 mm (IZD) Actidione 50 mm (IZD) |

[43] | ||

| Algicidal | Agar diffusion/Chlorella fusca | 9 mm (IZD) | Actidione 35 mm (IZD) | [43] | ||

| (−)-6-Methoxymellein (11) | Antiviral | CPE inhibition/H1N1 virus | 20.98 µg/mL (IC50) | Arbidol 0.15 µg/mL (IC50) | [26] | |

| Botryospyrone C (13) | Antifungal | 2-Fold broth dilution method/F. oxysporum | 223 μM (MIC) | Triadimefon 340 μM (MIC) | [71] | |

| Antifungal | 2-Fold broth dilution method/F. graminearum | 223 μM (MIC) | Triadimefon 510.7 μM (MIC) | [71] | ||

| 6-(4′-Hydroxy-2′-methyl phenoxy)-(−)-(3R)-mellein (16) | Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Trichophyton longifusus | 55 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 70 (% Inhibition) | [68] | |

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Microsporum canis | 70 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 98.4 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| Antifungal | Agar tube dilution/Fusarium solani | 30 (% Inhibition) | Miconazole 73.2 (% Inhibition) | [68] | ||

| Antioxidant | DPPH | 159 μM (IC50) | PG 30 159 μM (IC50) BHA 44 μM (IC50) |

[68] | ||

| Antioxidant | XO Inhibition | 243 μM (IC50) | PG 628 μM (IC50) BHA 591 μM (IC50) |

[68] | ||

| (3R,4R)-3,4-Dihydro-4,6-dihydroxy-3-methyl-1-oxo-1H-isochromene-5-carboxylic acid (34) | Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overaly/Cladosporium cladosporioides | 10 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | |

| Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overlay/Cladosporium sphaerospermum | 25 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory | TLC-based AChE inhibition | 3 µg (IC) | Galantamine 1µg (IC) | [17] | ||

| (3R)-Mellein (35) 3,4-Dihydro-(3R)-methyl-8-hydroxyisocoumarin |

Antifungal | Agar diffusion/Botrytis cinerea | 49.2 µg/mL (EC50) | - | [53] | |

| (R)-7-Hydroxymellein (36) | Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overlay/Cladosporium cladosporioides | 5 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | |

| Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overlay/Cladosporium sphaerospermum | 10 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory | TLC-based AChE inhibition | 10 µg (IC) | Galantamine 1µg (IC) | [17] | ||

| (3R,4R)-4,7-Dihydroxymellein (37) | Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overlay/Cladosporium cladosporioides | 5 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | |

| Antifungal | Direct Bioautography Overlay/Cladosporium sphaerospermum | 10 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | Nystatin 1 µg (Minimum amount required for inhibition of fungi growth on TLC plates) | [17] | ||

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory | TLC-based AChE inhibition | 10 µg (IC) | Galantamine 1µg (IC) | [17] | ||

| Periplanetin A (39) | Antivirus | Spectrophotometer/Anti-TMV | 14.6% GI (20 μM) | Ningnanmycin 28.6% GI (20 μM) | [44] | |

| (3R)-Methyl-8-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-7-methoxydihydroisocoumarin (40) | Antiviral | Spectrophotometer/Anti-TMV | 21.8% GI (20 μM) | Ningnanmycin 32.8% GI (20 μM) | [112] | |

| (3R)-Methyl-7,8-dimethoxy-6-(hydroxymethyl) dihydroisocoumarin (41) |

Antiviral | Spectrophotometer/Anti-TMV | 18.6% GI (20 μM) | Ningnanmycin 32.8% GI (20 μM) | [112] | |

| S-(-)-5-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-4-(1′-hydroxyethyl)-isocoumarin (54) | α-Glucosidase inhibitory | Chromogenic | 537.3 μM (IC50) | Acarbose 958.3 μM (IC50) | [62] | |

| S-(-)-5,6,8-Trihydroxy-4-(1′-hydroxyethyl)isocoumarin (65) | α-Glucosidase inhibitory | Chromogenic | 315.3 μM (IC50) | Acarbose 958.3 μM (IC50) | [62] | |

| Antibacterial | Colorimetric broth microdilution/S. aureus (ATCC 27154) | 12.5 μM (MIC50) | Ciprofloxacin 0.160 μM (MIC50) | [52] | ||