Abstract

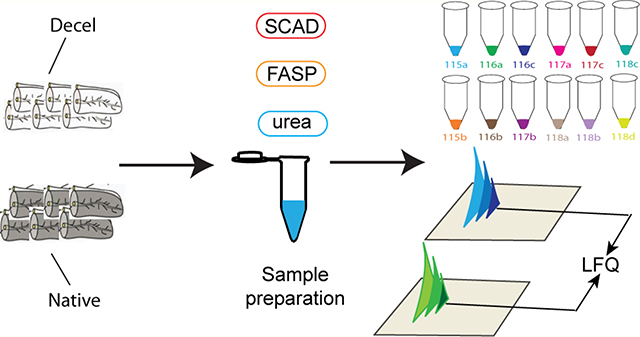

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is an important component of the pancreatic microenvironment which regulates β cell proliferation, differentiation, and insulin secretion. Protocols have recently been developed for the decellularization of the human pancreas to generate functional scaffolds and hydrogels. In this work, we characterized human pancreatic ECM composition before and after decellularization using isobaric dimethylated leucine (DiLeu) labeling for relative quantification of ECM proteins. A novel correction factor was employed in the study to eliminate the bias introduced during sample preparation. In comparison to the commonly employed sample preparation methods (urea and FASP) for proteomic analysis, a recently developed surfactant and chaotropic agent assisted sequential extraction/on pellet digestion (SCAD) protocol has provided an improved strategy for ECM protein extraction of human pancreatic ECM matrix. The quantitative proteomic results revealed the preservation of matrisome proteins while most of the cellular proteins were removed. This method was compared with a well-established label-free quantification (LFQ) approach which rendered similar expressions of different categories of proteins (collagens, ECM glycoproteins, proteoglycans, etc.). The distinct expression of ECM proteins was quantified comparing adult and fetal pancreas ECM, shedding light on the correlation between matrix composition and postnatal β cell maturation. Despite the distinct profiles of different subcategories in the native pancreas, the distribution of matrisome proteins exhibited similar trends after the decellularization process. Our method generated a large data set of matrisome proteins from a single tissue type. These results provide valuable insight into the possibilities of constructing a bioengineered pancreas. It may also facilitate better understanding of the potential roles that matrisome proteins play in postnatal β cell maturation.

Keywords: extracellular matrix (ECM), matrisome, SCAD, FASP, urea, label-free quantitation (LFQ), dimethylated leucine (DiLeu), isobaric quantitation, decellularized pancreas

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The pancreatic ECM is composed of a plurality of three-dimensional, structural proteins in a state of “dynamic reciprocity” with the cells of the endocrine pancreas,1 responsible for transmitting a wealth of chemical and mechanical cues that influence and regulate islet proliferation,2 differentiation,3 adhesion,4 migration,5 insulin secretion,6 and survival.7 The decellularized human pancreas, therefore, represents a natural scaffold that may be capable of recapitulating the in vivo environment of islets to enhance survival and function of the cells throughout the isolation, culture, and transplantation process. A full characterization of the human pancreatic matrisome would provide important insights into pancreatic ECM composition and potentially lead to improvements in the engraftment and survival of β cell replacement therapies from isolated islets or stem cell β cells. A key challenge in implementing a decellularized scaffold-based tissue engineering platform lies in understanding the process of removing cellular remnants and immunogenic material from donor tissue while maintaining the biochemical and biomechanical properties of the scaffold structure.8

Mass spectrometry (MS) is a powerful tool to study the protein composition of a complex biological system. It can determine the relative abundances of biomolecules between different experimental conditions, characterize various post-translational modifications, and map spatial distributions of analytes within a tissue. The biochemical and biophysical properties of ECM make it challenging for MS-based analyses. In-depth analysis of ECM is limited due to the complexity of ECM composition within tissues and the dynamic range of analytes. ECM interacts with other molecules and undergoes heavy cross-linking, which also creates difficulties in the solubilization process for subsequent MS analysis.

The biological complexity can be overcome by the incorporation of various isolation, enrichment or separation methodologies prior to MS analysis. 2D gel separation is a commonly used method which separates the proteins by differences in their isoelectric point and/or protein mass.9 However, the application of this technique is limited by its low resolution, reproducibility, narrow dynamic range and bias against membrane proteins and low abundance proteins.10 With high orthogonality to reversed phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography is one of the most widely adopted methods for off-line fractionation. In acidic solution, most tryptic peptides are characterized by a net charge of 2+ or above, which separates them from the peptides with a net charge of 1+, as well as the peptides which possess higher net charges.11 This is especially useful for the isobaric labeled samples to reduce coisolation of analytes and improve the accuracy of the quantification.

Characterizing ECM composition is another challenging task. Only solubilized proteins can be analyzed by bottom-up proteomic approaches. To obtain deep coverage of ECM proteins, a number of protein extraction methods have been developed. Researchers have utilized chaotropic agents to extract ECM proteins from cartilaginous tissues and rat mammary glands.12,13 Detergent-based methods are another popular strategy for ECM characterization.8,14,15 Although numerous ECM proteins across various tissue types can be identified using these protocols, an insoluble protein pellet was commonly observed when different tissue samples were analyzed.16 These pellets were mainly composed of fibrillar proteins, leading to the nonidentification of fibrillar collagen (e.g., collagen 1a1).14,17 To improve the recovery of ECM proteins from the insolubilized pellet, Hill et. al employed sequential extractions which combined chemical digestion with enzymatic digestion.16 Complete tissue extraction was thus accomplished, and the absolute abundance of ECM proteins was quantified which demonstrated that collagen 1a1 was fully retained after decellularization and digestion. A quantitative detergent solubility profiling (QDSP) method was developed by Mann and co-workers which gradually increased the stringency of the detergents and obtained four distinct fractions from lung homogenates.18,19 Efforts have also been made by Naba et al. to utilize multistep enrichment and offline fractionation to enhance the identification of ECM composition of breast cancer tissues.20 Despite the success to overcome the solubility issue of ECM molecules, these newly developed approaches require extensive fractionation/extraction which is labor intensive. A recent study by Krasny et al. also revealed that extraction method can affect the identification of matrisome composition.21

The matrix composition varies among different tissue types and developmental ages.8 Such tissue-specific matrices may be preferred for certain cell types and applications. Several recent studies have characterized the ECM composition of murine and porcine pancreas, as well as murine pancreatic islets.22–25 Due to the distinct composition of human pancreas compared to animal tissue, a comprehensive characterization of human pancreas matrisome is still in need. Studies have shown that the culture of human islets with purified ECM proteins can have beneficial or detrimental effects on β cell function. For example, Goh et al. found that when the mouse MIN-6 insulinoma cell line was cultured on various ECM platforms, there were significantly variable levels of insulin I (Ins1) gene expression, however a beneficial effect on β cell function was not shown/observed.24 In order to optimize the effect ECM coculture may have on improving β cell function, a more complete understanding of the ECM composition is required. To perform qualitative and quantitative characterization of the tissue-specific matrisome composition with higher throughput, it is beneficial to establish a multiplexed labeling technique to measure the relative abundance of proteins among different tissue types.26

Here we demonstrate that 12-plex dimethylated leucine (DiLeu) isobaric tags can be utilized to perform in-depth relative quantification of proteins from native and decellularized ECM scaffolds from both adult and fetal pancreas.27,28 This method was compared to a well-established label-free quantification approach. Similar expressions of different categories of proteins were observed, indicating the robustness of both quantification strategies. For these approaches a complete protein extraction was accomplished with the recently developed novel sample preparation protocol known as the surfactant and chaotropic agent assisted sequential extraction/on pellet digestion (SCAD) method.29 The implementation of SCX reduced the complexity of the analytes and increased accuracy of the quantification.30 We quantified the relative protein abundance of native and decellularized human pancreas from differently aged fetal and adult samples. Native and decellularized pancreas matrix protein abundance results clustered into groups in an age-dependent manner. The results provide valuable insight into human pancreas ECM composition, which will ultimately facilitate the study of the role that ECM plays in β cell maturation, survival, and function.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Pancreatic Tissue Decellularization

Adult human pancreata (age 27–64 years) were obtained from the University of Wisconsin Organ and Tissue Donation Services Organization within 24 h of donation, with donor next-of-kin consent for research. The parenchyma was separated from extrapancreatic vascular and adipose tissue and then cut into 1 cm3 pieces and frozen at −80 °C for storage prior to decellularization. Thawed pancreas pieces were homogenized and treated with 2.5 mM deoxycholate and lipase over an 18-h period to decellularize the tissue and the resulting pancreatic ECM was washed, lyophilized and stored at −80 °C until analysis. A detailed description of the decellularization process can be found in the literature.31–33

Fetal pancreata were obtained under approved Material Transfer Agreements and with Institutional Review Board approval from secondary sources. The organs were processed within 24 h of recovery, cleaned of extrapancreatic tissue and frozen in CryoStor 10 (Stem Cell Technologies) freezing medium for future use. Pancreata were thawed, washed, manually cut into smaller pieces, and treated with 2.5 mM deoxycholate for 3 h to decellularize. Following decellularization, the ECM was thoroughly washed with PBS for 48 h, followed by water for 48 h, with changes to fresh solution every 24 h. The ECM was lyophilized and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Protein Extraction and Digestion

For SCAD, lyophilized, decellularized tissues were dissolved in buffer solution (4% SDS, 50 mM Tris buffer) and incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. The experiments were conducted following the protocol described previously.29 In brief, samples were reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide. SDS was removed by two rounds of precipitation. The sample was centrifuged and the pellet was air-dried at room temperature. 8 M urea was added and on-pellet digestion was performed with Lys-C/trypsin. 50 mM Tris buffer was added to the urea solution along with trypsin (1:100) for overnight digestion. The reaction was quenched with 1% TFA and desalted with Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters). Concentrations of peptide mixture were measured by peptide assay (Thermo). Samples were lyophilized and stored in −80 °C until use.

For filter-aided sample preparation (FASP), decellularized pancreata were dissolved in SDT buffer (4% SDS, 50 mM Tris buffer of 0.1 M DTT) and incubated at 95 °C for 5 min. The experiments were conducted following the previous published procedure.34 In brief, protein lysates were loaded onto 30k centrifugal filter units and underwent ultrafiltration at 14 000g. Urea was used to remove the SDS and the sample was alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide. Proteins were subjected to on membrane trypsin digestion at 37 °C overnight (1:50), quenched with 1% TFA, and desalted with Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters).

For in-solution digestion with urea, decellularized pancreata were lysed in lysis buffer containing 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 30 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor tablet (cOmplete, EDTA-free). Digestion followed a previously described protocol.33 In brief, protein extracts were reduced with DTT, alkylated with iodoacetic acid (IAA), and subjected to digestion with trypsin at 37 °C overnight (1:50). The samples were quenched with 1% TFA and desalted with Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters).

DiLeu Labeling

A total of 1 mg of each DiLeu label was dissolved in 25 μL of anhydrous DMF and combined with DMTMM and NMM at 0.7X molar ratio to DiLeu labels. The activation occurred by vortexing the mixture for 1 h at room temperature. The supernatant was used immediately to label the peptides.

5X w/w activated DiLeu reagents were used to label the protein extract. Additional anhydrous DMF was added to ensure organic composition reaches 70% (v/v). The labeling reaction was performed at room temperature by vortexing for 2 h and quenched by addition of hydroxylamine to a concentration of 0.25%. The labeled samples were pooled at a 1:1 ratio across all samples and dried in vacuo.

Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) Fractionation

SCX was performed on a Waters Alliance e2695 HPLC (Milford, MA) with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Tryptic peptides were dissolved in 10 mM NH4HCO2, 25% ACN (v/v), pH 3, and loaded onto a 200 mm × 2.1 mm polySULFOETHYL A (PolyLC, Columbia, MD) column with 5 μm packing materials. Buffer A was composed of 10 mM NH4HCO2, 25% ACN (v/v), pH 3, and buffer B was composed of 500 mM NH4HCO2, 25% ACN (v/v), pH 6.8. Gradient elution program started with 100% A for 20 min, followed by a gradient of 0−50% B for 70 min. B increased from 50 to 100% over 10 min and stayed at 100% B for 10 min. The fractions were collected every 1.5 min and concatenated into 10 fractions determined by UV−vis at 215 nm.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Experiments were performed on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) coupled to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 UPLC system. The digested peptide mixtures were separated by 75 μm × 15 cm fabricated column which was filled with 1.7 μm Ethylene Bridged Hybrid packing materials (130 Å, Waters). A 90 min gradient was utilized at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The instrumental acquisition parameters were employed as described previously.29,33

Data Analysis

For DiLeu labeled samples, the Coon OMSSA proteomic Analysis Software Suite (COMPASS) was used for peptide identification. Raw files were converted to text files and searched against the Homo sapiens Uniprot database (Dec 2015). Trypsin was selected as the enzyme and maximum of two missed cleavages were allowed. Precursor ion tolerance was set to 25 ppm and fragment ion tolerance was 0.02 Da. DiLeu labeling on peptide N-termini and lysine residue (+145.1267748), and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.02146 Da) were chosen as static modifications. Methionine oxidation (+15.99492 Da), hydroxylation (+15.99492 Da) on proline and DiLeu labeling on tyrosine residues (+145.1267748) were selected as variable modifications. Search results were filtered to 1% false discovery rate (FDR) at both peptide and protein levels. Quantification was performed using an in-house software called DiLeu tool. In brief, reporter ion intensities from DiLeu-labeled peptides were collected from raw files at a reporter ion integration tolerance of 20 ppm for the most confident centroid with DiLeu tool. Only the PSMs that contained all 12 reporter ions were considered for quantification. Quantitative value for each protein was determined by the reporter ion intensities of the corresponding unique peptides. Reporter ion abundances are corrected for isotope impurities with python script.

For unlabeled samples, data were analyzed with MaxQuant (1.6.0.1). Spectra were searched against the Homo sapiens UniProt database (December 2015). For MS1 scans, a precursor ion mass tolerance of 10 ppm was used and two missed cleavages were allowed. Fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.5 Da. The variable modifications included methionine oxidation, proline hydroxylation and N-terminal protein acetylation whereas carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as fixed modification. The FDR was set at 0.01 for both peptide and protein identification using the target-decoy strategy.35 The minimal number of unique peptide(s) per protein was 1. Quantification was performed using MaxQuant (1.6.0.1) with MaxLFQ algorithm.36 The “match between run” option was enabled to maximize the number of quantification events across samples.

RESULTS

Enhancing ECM Extraction with SCAD

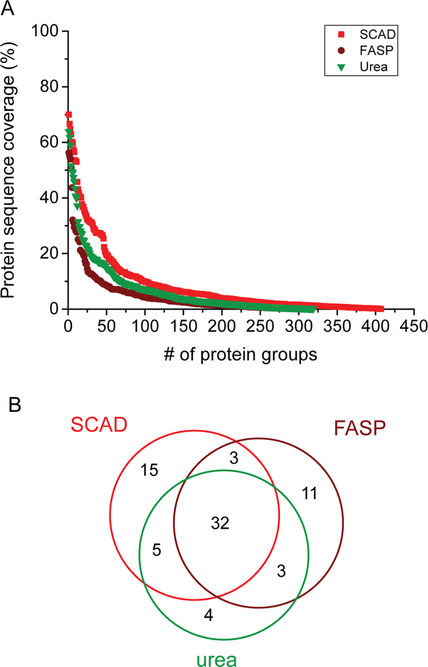

ECM proteins are heavily cross-linked, which make them difficult to solubilize. To enable comprehensive characterization of the ECM from native and decellularized pancreatic tissue, a sample preparation strategy that provides complete protein extraction is of great importance. We recently developed SCAD,29 a novel sample preparation protocol. This method takes advantage of the extraordinary solubilizing power of both surfactant (SDS) and chaotropic (urea) agents to achieve more comprehensive protein extractions. The utilization of Lys C not only improves the digestion efficiency, but more importantly, because Lys C has better tolerance against higher urea concentration, it was used for on-pellet digestion. On-pellet digestion enabled improved recovery and solubilization of insoluble pellets which was otherwise discarded in the bottom up proteomic approaches. After sequential enzymatic digestion, the digested peptides exhibited better solubility which were completely dissolved in the urea buffer. By conducting serial extractions, the SCAD method combines the advantages of SDS and urea without analyzing the sample twice, which is more straightforward and more easily accomplished with higher efficiency. Due to the superior performance of this strategy, we explored the utility of the SCAD method for ECM extraction. The efficiency of the approach was compared with two widely used ECM extraction protocols, FASP8,37 and urea.12,38,39 Decellularized human pancreata were utilized in the study for the comparison and three technical replicates were performed for each approach. SDS served as denaturant and as an efficient inactivator for endogenous proteases at 95 °C; therefore, protease inhibitor was only added to the in-solution digestion sample to prevent protein degradation. A full list of the identified ECM proteins by each method and the reproducibility between replicates can be found in Table S1 and Figure S1. As shown in Figure 1, the SCAD method rendered higher sequence coverage in comparison to FASP and urea. In addition, more proteins were detected using the SCAD method, with 15 matrisome-related proteins exclusively identified by this technique, indicating that the SCAD method is superior for proteomic analysis of pancreatic ECM.

Figure 1.

Comparison of sequence coverage achieved (A) and Venn diagram showing overlap of matrisome proteins identified among different sample preparation strategies (B).

Establishment of Quantification Approach with 12-plex DiLeu

We next applied the SCAD method to analyze the ECM composition of native and decellularized adult pancreas. 12-plex DiLeu tags were utilized in the study to achieve multiplexing and simultaneous quantification of different samples. In order to introduce the identical mass shift at the MS1 level, different isotopes (e.g., deuterium) were incorporated into the reporter and balance groups of the isobaric tagging structures.27 Retention time shift between hydrogen and deuterium labeled peptides is often observed in the labeling-based experiments.40 To minimize the effect of deuterium shift, deuterium-containing DiLeu tags were used to label the same pair of the samples that contained both native tissues as well as ECM scaffolds (Table S2).

After decellularization, most of the proteins were removed while some of the ECM proteins were retained (Figures S2 and S3). Therefore, the decellularized sample has fewer categories of the proteins in comparison to the native tissue. When the same amount of protein was taken out from both decellularized and native tissues for the MS analysis, the abundances of individual proteins retained following decellularization were proportionally higher in the decellularized sample than in the native sample as shown in Figures S2 and S3. This is an artifact introduced during the sample preparation. To counteract the bias, herein, we employed a novel correction factor method for the quantitative proteomic comparison of native and decellularized pancreata. All the proteins were normalized by donor specific collagen protein COL1A1 ratio (decellularized/native) as shown in the equation: This correction factor was determined after filtering a list of proteins which may get fully retained after the decellularization process, and then a selection was made for the protein that has both the highest abundance in the sample and the highest ratio (decellularized/native) as the one that maintains 100% “retention” efficiency through the decellularization process. In line with our data, Hill et al. also reported the complete retention of COL1A1 (100% retention) from decellularized rat lung using absolute quantification.16

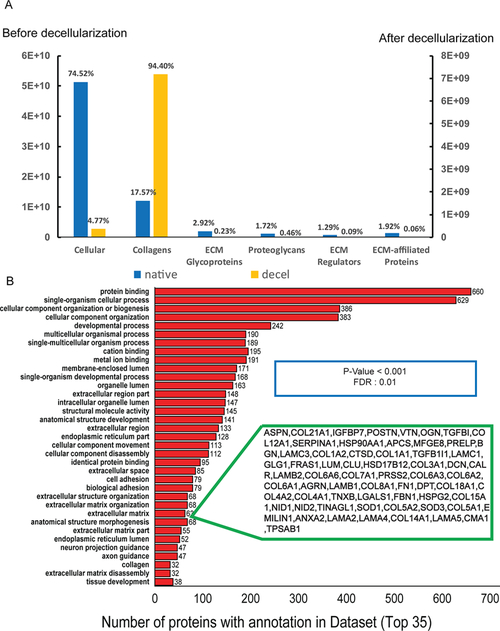

SCX offline fractionation was employed to reduce the complexity of the analytes, to improve the detection of low-abundance proteins and to circumvent the ratio compression issue.41,42 In total, we identified and quantified 1928 proteins across all samples. The identified proteins were categorized into nonmatrisome and various categories of matrisome proteins based on the information from MatrisomeDB which consists of in silico and in vivo data on the matrisome.38,43 Among the 1928 proteins identified in native and decellularized pancreas, 120 were assigned to the matrisome category. The quantitative information on protein abundance in each of the subcategories is listed in Table 1 and Table S3. As depicted in Figure 2, nonmatrisome proteins accounted for 74.5% of the proteins identified in the native samples and 4.7% of proteins in decellularized samples. On the other hand, collagens represented only 17.6% of the total proteins identified in the native samples, whereas this percentage increased to 94.4% in the decelled samples. In this study, most of the nonmatrisome proteins (99.1%) were removed following decellularization, while many of the collagens were retained, demonstrating the effectiveness of the decellularization process. 33 isoforms of 19 types of collagen were identified, including fibrillar collagen I, II, III, V, XI, network-forming collagen IV, and collagen VI that form beaded filaments. Their roles in regulating survival, proliferation, differentiation of β cells and insulin secretion have been implicated in previous studies, making them important components of scaffolds in transplantation and tissue engineering.44 Many other ECM proteins and proteoglycans were also detected, including laminin isoforms and fibronectin which localize to the basement membrane. Furthermore, we identified a myriad of ECM regulators, ECM-affiliated proteins, as well as secreted factors. Clustering of these proteins based on cellular compartment and function indicated that proteins related to protein binding, extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, developmental stage, and collagen were highly enriched (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that our strategy is effective for the extraction and identification of matrisome proteins.

Table 1.

Numbers of Quantifiable Proteins across All Samples in Each Subcategory by DiLeu Labeling with SCAD Extraction Method

| type | number | |

|---|---|---|

| core matrisome | collagens | 33 |

| ECM glycoproteins | 31 | |

| proteoglycans | 8 | |

| matrisome associated | ECM regulators | 22 |

| ECM-affiliated proteins | 20 | |

| secreted factors | 6 | |

| matrisome total | 120 |

Figure 2.

Percentage of relative intensity quantified by DiLeu labeling for nonmatrisome proteins and each matrisome subcategory from adult pancreas before and after decellularization process (A) and gene ontology enrichment analysis of quantified proteins, top 35 annotations were listed (B).

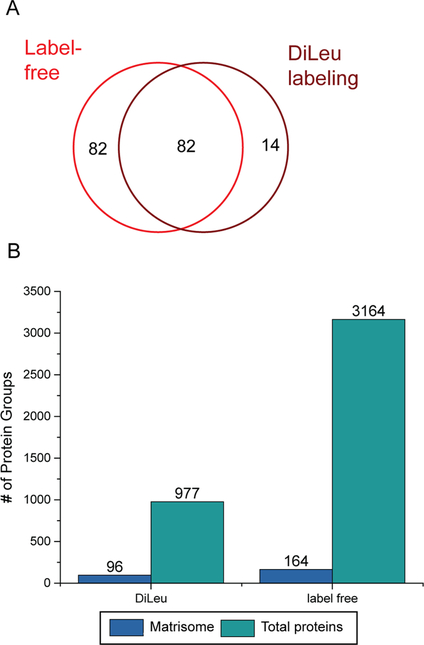

Characterization of Human Pancreas Matrisome at Different Developmental Stages

Although comprehensive comparison between the adult and fetal pancreas ECM has not been made, it is well established that changes in gene and protein expression accompany functional changes as β cells mature.45–48 Given the dynamic changes in the ECM that occur during development, we chose to expand our techniques and explore the utilization of label-free approach to identify differences in the ECM between the fetal pancreas and adult pancreas. A recently optimized data-dependent acquisition (DDA) method was employed to enable in-depth analysis of the pancreatic proteome without offline fractionation or extending the gradient time.29 This strategy was compared to the DiLeu labeling technique and the results are shown in Figure 3. The label-free approach led to a greater than 3-fold increase in total proteins and 2-fold increase in matrisome proteins. More than 90% of the matrisome proteins identified in the DiLeu labeling method were also identified in the label-free approach, with 82 additional matrisome proteins exclusively observed in the label-free approach. Compared to the labeling based method, label-free approach does not require additional labeling and sample cleanup steps, the database search algorithm is also less complex. Therefore, an increased peptide/protein identification rate has been reported.42,49,50 This in-depth analysis provides enhanced identification of low abundance proteins which may be important components of a biological scaffold. It is noted that a similar percentage of matrisome subcategory proteins were observed using either the DiLeu or label-free approach, which indicated that both methods provided accurate estimation of protein abundance inside the pancreas (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing overlap of matrisome proteins identified in fetal pancreas between label-free method and DiLeu labeling (A) and number of total proteins and matrisome-related proteins identified in fetal pancreas (B).

Table 2.

Percentage of Matrisome Subcategory Proteins from Fetal and Adult Pancreas after Decellularization Quantified by DiLeu or Label-Free Methods

| DiLeu_Fetal | LFQ_Fetal | DiLeu_Adult | LFQ_Adult | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| collagens | 94.54% | 99.83% | 99.12% | 99.76% |

| ECM glycoproteins | 2.27% | 0.08% | 0.24% | 0.10% |

| proteoglycans | 2.58% | 0.05% | 0.48% | 0.06% |

| ECM-affiliated Proteins | 0.20% | 0.00% | 0.10% | 0.01% |

| ECM regulators | 0.40% | 0.03% | 0.07% | 0.07% |

| secreted factors | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

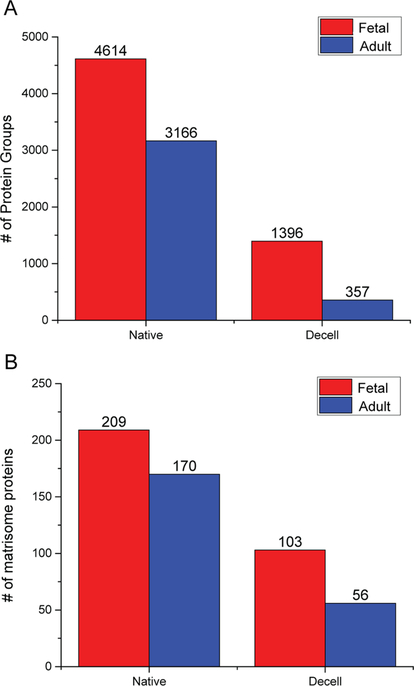

With the encouraging proteomics results from label-free approach, we sought to investigate the quantitative distribution of matrisome proteins at different developmental stages and how they were affected by the decellularization process. Here we focused on the identity and quantity of proteins that were retained after the decellularization procedure, and of equal importance, the proteins which were removed during the process. We analyzed the tissue from two developmental stages (fetal and adult) under native and decellularized conditions, with three biological replicates for each condition. In total, we identified 5922 proteins, 271 of which were assigned to the matrisome categories, generating a large data set of matrisome proteins from a single tissue type (Table S4 and Figure S4). Of the 35 pancreas enriched protein-coding genes listed in the Human Protein Atlas, 32 of them were detected in our study.51,52 Proteomic results for each condition are shown in Figure 4A. As illustrated in the figure, more proteins were detected in the native fetal pancreas than the native pancreas from adult group. As expected, the decellularization process removed many proteins; protein identifications dropped to 1396 and 357 for fetal and adult tissues, respectively. To gain a better understanding of the ECM composition, we also investigated matrisome proteins present among the donors within the different age groups (Figure 4B). In line with the results shown above, a higher number of matrisome proteins were identified in native fetal pancreas while 170 matrisome proteins were detected in the native pancreas from adult group. A significant decrease of matrisome proteins was also observed following the decellularization process, which led to the detection of 103 and 56 matrisome proteins in decelled fetal and adult groups, respectively.

Figure 4.

Number of total proteins (A) and matrisome-related proteins (B) identified in fetal and adult pancreas before and after decellularization process using LFQ method.

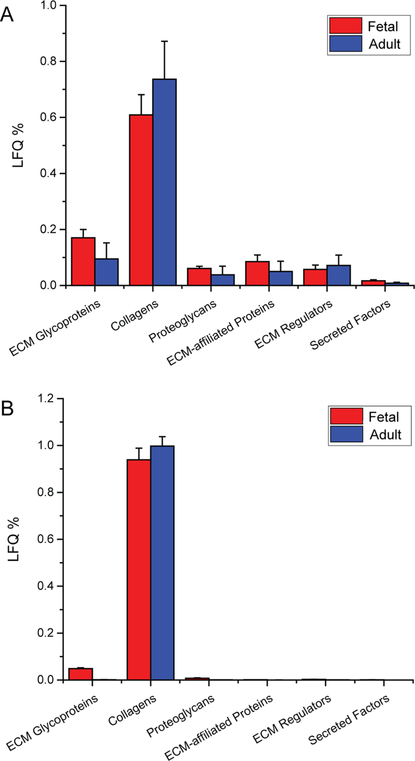

By applying the LFQ technique, the distributions of matrisome proteins among various subcategories were revealed, as shown in Figure 5. Collagens were the major contributors to the composition of the native pancreas matrisome, which accounted for 65% to 86% of LFQ intensity. As an important component of the cell-matrix interaction, the glycoprotein abundance also ranged from 6% to 15% across the different developmental stages. Despite the distinct profiles of defined subcategories in the native pancreas, the distribution of matrisome proteins exhibited similar trends following decellularization.

Figure 5.

Percentage of LFQ intensity for each matrisome subcategory in native pancreas (A) and decellularized pancreas (B).

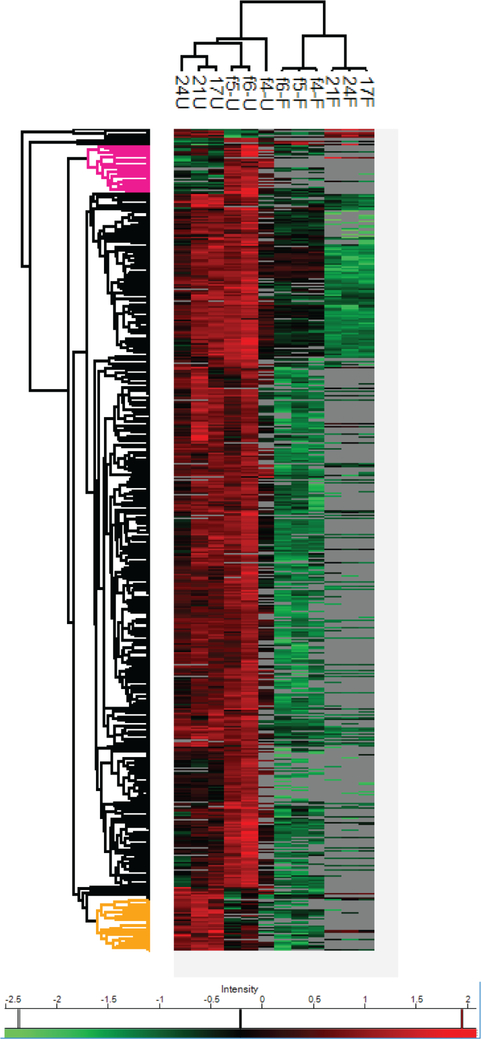

To quantitatively characterize the protein changes during the decellularization, we used hierarchical clustering to categorize the proteins into different groups based on their expression profiles. As illustrated in Figure 6, the samples were classified into two overarching groups which separated the native samples from the decelled samples. Each group was clearly clustered into two subgroups based on the developmental stage, indicating that each stage has a unique proteome/matrisome profile. Interestingly, the cluster of proteins with higher expression in native adult pancreas as compared to fetal tissues (highlighted in yellow) is enriched in collagen and extracellular proteins (P value: 2.88 × 10−13 and 1.31 × 10−12, respectively), including some matrisome proteins such as collagen I, III, V, VI, VII, XVI, XXVIII, and SERPINA3. The function of collagen I has been implicated in promoting precursor cells into glucose-responsive β cells.53 Collagen VI was demonstrated to support the in vitro viability and survival of human pancreatic islets.54 On the contrary, some matrisome proteins have higher expression levels in the fetal pancreas in comparison to the adult group (highlighted in pink). The distinct difference of protein expression can be used to distinguish adult from fetal pancreas, which will provide a foundation for correlating matrix composition and postnatal β cell maturation. As expected, the majority of proteins decreased following decellularization. In comparison to the adult group, some fetal pancreas ECM proteins were retained better after decellularization, including dermatopontin, a glycoprotein which promotes fibronectin fibril formation and enhances cell adhesion;55 fibrillin-2, a microfibrillar component which is required during developmental stages56 and collagen II.

Figure 6.

Heatmap visualization of protein expression profiles of human pancreas from various ages before and after decellularization process. A dendrogram of two pancreas ages (fetal and adult) with two experimental conditions (native (U) and decellularized (F) pancreas) (17U, 21U, and 24U for adult native; 4f-U, f5-U, and f6-U for fetal native; 17F, 21F, and 24F for adult decell; f4, f5, and f6 for fetal decell) was shown at the top. Protein expression values were Z-score normalized prior to clustering. Hierarchical clustering of protein expression profiles identified four groups. The cluster of proteins with higher abundance in fetal pancreas was highlighted in pink. The cluster of proteins with higher abundance in adult tissues was highlighted in yellow.

DISCUSSION

ECM-islet interactions are known to regulate various aspects of islet physiology, including proliferation, differentiation, survival, and insulin secretion.44,57–60 ECM proteins are heavily cross-linked, making them hard to solubilize and analyze by MS. In this work, we demonstrated that a recently developed SCAD method enables comprehensive characterization of ECM from decellularized and native pancreas. Unlike previous studies which performed tissue extraction with surfactant and chaotropic agents separately, we conducted sequential extraction with SDS and urea in a single experiment. The protein extraction was further enhanced by on-pellet digestion which allowed for more complete protein extraction from the tissue. Given the simplicity and low protein loss of the method, a minimal sample amount (<1 mg of tissue) was required for the analysis, which facilitated a molecular readout of the scaffold with limited sample material.

Isobaric labeling is a powerful technique that enables assessment of the relative abundances of proteins among biological samples.26 In isobaric labeling-based quantification, each sample is labeled with a different isobaric tag from a set, and the samples are pooled and analyzed together. This feature reduces the overall analytical time (2400 min for DiLeu labeling compared to 3600 min for label-free for 12 samples with 2 technical replicates) and run to run variation. Identical peptides from different samples have the same mass shift at the MS1 level, so the mixture of multiple samples improves the signal-to-noise ratio and the sensitivity of detection, thereby allowing higher quality MS2 spectra to be acquired for low copy number proteins. 12-plex DiLeu isobaric tags were employed in the study to understand the composition of the ECM proteins before and after decellularization. Proteomic results revealed that cellular compartment proteins were mostly removed after decellularization while retaining core matrisome proteins. Retained cellular proteins can elicit immunogenic responses and may lead to rejection of a graft following transplantation if not matched to the recipient’s immune system.8,61,62 Therefore, extracted ECM proteins with minimal residual cellular components are desirable following decellularization. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of our decellularization process and the ability to successfully solubilize the ECM for proteomic analysis. Our study also represents the first application of using an isobaric labeling technique to monitor the retention of ECM proteins during the decellularization process.

To better understand the changes in matrix composition that correlate with postnatal β cell maturation, we used an optimized label-free quantification strategy to quantify the relative abundance of pancreatic proteome of various developmental stages (fetal and adult). By comparing the label-free MS results with the data obtained from DiLeu labeling, a similar percentage of proteins from matrisome subcategories were observed, demonstrating the effectiveness and accuracy of both methods for the ECM protein quantification (Table 2). Importantly, distinct ECM protein expression profiles were observed in fetal vs adult pancreata. In line with previous studies, the label-free method generated a deeper proteome coverage in comparison to DiLeu labeling, while DiLeu labeling reduced the instrument time needed and eliminated stochastic precursor ion selection.50 Differential expression of ECM proteins was observed in the adult pancreas as compared to fetal tissue, which implicates prominent roles of ECM proteins in the postnatal β cell maturation. Recent publications have shown that expression of integrin β3 is downregulated in the adult islet cells compared to the fetal islet cells.63 It plays an important role in mediating adhesion and migration of undifferentiated pancreatic epithelial cells. In our study, Integrin β3 was only identified in the fetal tissue which corroborates with previous findings and further provides valuable insights into the unique functions of ECM proteins in β cell maturation.

As illustrated in Figures 5b and 6, similar protein profiles were observed in decellularized pancreatic ECM between the fetal and adult pancreas, indicating that the decellularization process revealed a similar ECM microenvironment between age groups. Despite the similarities between fetal and adult pancreatic ECM, some differences were in fact observed. For example, laminins were better retained in the fetal pancreas following decellularization than in the adult. The differences in protein composition of ECM scaffolds from different developmental ages may assist in understanding the positive or detrimental effects that ECM has on β cell proliferation and function.

In summary, ECM is a critical component of the tissue microenvironment, which may have useful applications in cell culture, regenerative medicine and transplantation. Our study compares three sample preparation techniques and employs two quantification methodologies for characterizing the composition of the human pancreatic matrisome. We found that SCAD is a suitable method for ECM protein extraction of human pancreatic ECM matrix and that labeling methods for quantification have important advantages and also notable disadvantages. Moreover, our quantitative MS methods allowed comparison of the matrisome of two distinct developmental time points. In the future, the elucidation of the pancreatic matrisome may inform the construction of a better cellular niche for insulin-producing β cells.

Data Deposition

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD012460.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Venn diagram represents the overlap between ECM and ECM- associated proteins detected in technical replicates by SCAD (A), FASP (B), urea (C); Figure S2: Scheme of different categories of proteins extracted from decellularized pancreas; Figure S3: Scheme of different categories of proteins extracted from native pancreas and the rationale of applying novel correction factor; Figure S4: Venn diagram represents the overlap between ECM and ECM- associated proteins detected in biological replicates in decellularized adult (A), native adult (B), decellularized fetal (C), and native fetal (D); the proteins were colored based on their subcategories: collagens (blue), ECM glycoproteins (purple), proteoglycans (teal), ECM-affiliated proteins (orange), ECM regulators (light orange), secreted factors (pink) (PDF)

Table S1: List of identified ECM proteins by each sample preparation method (XLSX)

Table S2: Illustration of labeling strategy with 10-plex DiLeu; deuterated tags are marked in yellow (XLSX)

Table S3: Quantitative information on matrisome protein abundance in each of the subcategories (XLSX)

Table S4: List of identified ECM proteins by two developmental stages (adult, fetal) under native and decellularized conditions (XLSX)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grant funding from the NIH (R21AI126419, R01DK071801, RF1AG052324, and P41GM108538) and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (1-PNF-2016-250-S-B and SRA-2016-168-S-B). The Orbitrap instruments were purchased through the support of an NIH shared instrument grant (NIH-NCRR S10RR029531) and Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We would also like to acknowledge the generous support of the University of Wisconsin Organ and Tissue Donation Organization who provided human pancreata for research. Our research team would like to give special thanks to the families who donated tissues for this study. L.L. acknowledges a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professorship and the Charles Melbourne Johnson Distinguished Chair Professorship with funding provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00241.

Notes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): JSO is scientific co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, of Regenerative Medical Solutions, Inc. and has stock equity.

REFERENCES

- (1).Salvatori M; Katari R; Patel T; Peloso A; Mugweru J; Owusu K; Orlando G Extracellular Matrix Scaffold Technology for Bioartificial Pancreas Engineering: State of the Art and Future Challenges. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol 2014, 8 (1), 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Beattie GM; Rubin JS; Mally MI; Otonkoski T; Hayek A Regulation of Proliferation and Differentiation of Human Fetal Pancreatic Islet Cells by Extracellular Matrix, Hepatocyte Growth Factorand Cell-Cell Contact. Diabetes 1996, 45, 1223–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jiang FX; Cram DS; DeAizpurua HJ; Harrison LC Laminin-1 Promotes Differentiation of Fetal Mouse Pancreatic Beta-Cells. Diabetes 1999, 48 (4), 722–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Edamura K; Nasu K; Iwami Y; Ogawa H; Sasaki N; Ohgawara H Effect of Adhesion or Collagen Molecules on Cell Attachment, Insulin Secretion, and Glucose Responsiveness in the Cultured Adult Porcine Endocrine Pancreas: A Preliminary Study. Cell Transplant 2003, 12 (4), 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ryschich E; Khamidjanov A; Kerkadze V; Büchler MW; Zöller M; Schmidt J Promotion of Tumor Cell Migration by Extracellular Matrix Proteins in Human Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2009, 38 (7), 804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Weber LM; Hayda KN; Anseth KS Cell-Matrix Interactions Improve Beta-Cell Survival and Insulin Secretion in Three-Dimensional Culture. Tissue Eng., Part A 2008, 14 (12), 1959–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hammar E; Bosco D; Perriraz N; Maedler K; Donath M; Rouiller DG; Halban PA Extracellular Matrix Protects Pancreatic β-Cells Against Apoptosis. Diabetes 2004, 53, 2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li Q; Uygun BE; Geerts S; Ozer S; Scalf M; Gilpin SE; Ott HC; Yarmush ML; Smith LM; Welham NV; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Naturally-Sourced Biological Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rabilloud T; Lelong C Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis in Proteomics: A Tutorial. J. Proteomics 2011, 74, 1829–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chandramouli K; Qian P-Y Proteomics: Challenges, Techniques and Possibilities to Overcome Biological Sample Complexity. Hum. Genomics Proteomics 2009, 2009, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Edelmann MJ Strong Cation Exchange Chromatography in Analysis of Posttranslational Modifications: Innovations and Perspectives. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hansen KC; Kiemele L; Maller O; O’Brien J; Shankar A; Fornetti J; Schedin P An In-Solution Ultrasonication-Assisted Digestion Method for Improved Extracellular Matrix Proteome Coverage. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2009, 8 (7), 1648–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Önnerfjord P; Khabut A; Reinholt FP; Svensson O; HeinegÅrd D Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Eight Cartilaginous Tissues Reveals Characteristic Differences as Well as Similarities between Subgroups. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287 (23), 18913–18924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bonvillain RW; Danchuk S; Sullivan DE; Betancourt AM; Semon JA; Eagle ME; Mayeux JP; Gregory AN; Wang G; Townley IK; et al. A Nonhuman Primate Model of Lung Regeneration: Detergent-Mediated Decellularization and Initial in Vitro Recellularization with Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Tissue Eng., Part A 2012, 18 (23−24), 2437–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Song MN; Moon PG; Lee JE; Na M; Kang W; Chae YS; Park JY; Park H; Baek MC Proteomic Analysis of Breast Cancer Tissues to Identify Biomarker Candidates by Gel-Assisted Digestion and Label-Free Quantification Methods Using LC-MS/MS. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2012, 35 (10), 1839–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hill RC; Calle E. a.; Dzieciatkowska M; Niklason LE; Hansen KC Quantification of Extracellular Matrix Proteins from a Rat Lung Scaffold to Provide a Molecular Readout for Tissue Engineering. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14 (7), 961–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Welham NV; Chang Z; Smith LM; Frey BL Proteomic Analysis of a Decellularized Human Vocal Fold Mucosa Scaffold Using 2D Electrophoresis and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (3), 669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Schiller HB; Fernandez IE; Burgstaller G; Schaab C; Scheltema RA; Schwarzmayr T; Strom TM; Eickelberg O; Mann M Time- and Compartment-Resolved Proteome Profiling of the Extracellular Niche in Lung Injury and Repair. Mol. Syst. Biol 2015, 11 (7), 819–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Schiller HB; Mayr CH; Leuschner G; Strunz M; Staab-Weijnitz C; Preisendörfer S; Eckes B; Moinzadeh P; Krieg T; Schwartz DA; et al. Deep Proteome Profiling Reveals Common Prevalence of MZB1-Positive Plasma B Cells in Human Lung and Skin Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 2017, 196 (10), 1298–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Naba A; Pearce OMT; Del Rosario A; Ma D; Ding H; Rajeeve V; Cutillas PR; Balkwill FR; Hynes RO Characterization of the Extracellular Matrix of Normal and Diseased Tissues Using Proteomics. J. Proteome Res 2017, 16 (8), 3083–3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Krasny L; Paul A; Wai P; Howard BA; Natrajan RC; Huang PH Comparative Proteomic Assessment of Matrisome Enrichment Methodologies. Biochem. J 2016, 473 (21), 3979–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Naba A; Clauser KR; Mani DR; Carr SA; Hynes RO Quantitative Proteomic Profiling of the Extracellular Matrix of Pancreatic Islets during the Angiogenic Switch and Insulinoma Progression. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gaetani R; Aude S; DeMaddalena LL; Strassle H; Dzieciatkowska M; Wortham M; Bender RHF; Nguyen-Ngoc K-V; Schmid-Schöenbein GW; George SC; et al. Evaluation of Different Decellularization Protocols on the Generation of Pancreas-Derived Hydrogels. Tissue Eng., Part C 2018, 24 (12), 697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Goh SK; Bertera S; Olsen P; Candiello JE; Halfter W; Uechi G; Balasubramani M; Johnson SA; Sicari BM; Kollar E; et al. Perfusion-Decellularized Pancreas as a Natural 3D Scaffold for Pancreatic Tissue and Whole Organ Engineering. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (28), 6760–6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Vigier S; Gagnon H; Bourgade K; Klarskov K; Fülöp T; Vermette P Composition and Organization of the Pancreatic Extracellular Matrix by Combined Methods of Immunohistochemistry, Proteomics and Scanning Electron Microscopy. Curr. Res. Transl. Med 2017, 65 (1), 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rauniyar N; Yates JR Isobaric Labeling-Based Relative Quantification in Shotgun Proteomics. J. Proteome Res 2014, 13, 5293–5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Frost DC; Greer T; Li L High-Resolution Enabled 12-Plex DiLeu Isobaric Tags for Quantitative Proteomics. Anal. Chem 2015, 87 (3), 1646–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhong X; Yu Q; Ma F; Frost DC; Lu L; Chen Z; Zetterberg H; Carlsson CM; Okonkwo O; Li L HOTMAQ: A Multiplexed Absolute Quantification Method for Targeted Proteomics. Anal. Chem 2019, 91 (3), 2112–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ma F; Liu F; Xu W; Li L Surfactant and Chaotropic Agent Assisted Sequential Extraction/on Pellet Digestion (SCAD) for Enhanced Proteomics. J. Proteome Res 2018, 17 (8), 2744–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shen Y; Jacobs JM; Camp DG; Fang R; Moore RJ; Smith RD; Xiao W; Davis RW; Tompkins RG Ultra-High-Efficiency Strong Cation Exchange LC/RPLC/MS/MS for High Dynamic Range Characterization of the Human Plasma Proteome. Anal. Chem 2004, 76 (4), 1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Sackett SD; Tremmel DM; Ma F; Feeney AK; Maguire RM; Brown ME; Zhou Y; Li X; O’Brien C; Li L; et al. Extracellular Matrix Scaffold and Hydrogel Derived from Decellularized and Delipidized Human Pancreas. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ma F; Sun R-X; Tremmel D; Sackett S; Odorico J; Li L Large- Scale Differentiation and Site-Specific Discrimination of Hydroxyproline Isomers by Electron Transfer/Higher-Energy Collision Dissociation (EThcD) Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2018, 90 (9), 5857–5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Liu F; Ma F; Wang Y; Hao L; Zeng H; Jia C; Wang Y; Liu P; Ong IM; Li B; et al. PKM2Methylation by CARM1 Activates Aerobic Glycolysis to Promote Tumorigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol 2017, 19 (11), 1358–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wiśniewski JR; Zougman A; Nagaraj N; Mann M Universal Sample Preparation Method for Proteome Analysis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6 (5), 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Elias JE; Haas W; Faherty BK; Gygi SP Comparative Evaluation of Mass Spectrometry Platforms Used in Large-Scale Proteomics Investigations. Nat. Methods 2005, 2 (9), 667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Cox J; Hein MY; Luber CA; Paron I; Nagaraj N; Mann M Accurate Proteome-Wide Label-Free Quantification by Delayed Normalization and Maximal Peptide Ratio Extraction, Termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13 (9), 2513–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Harvey A; Yen T-Y; Aizman I; Tate C; Case C Proteomic Analysis of the Extracellular Matrix Produced by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Implications for Cell Therapy Mechanism. PLoS One 2013, 8 (11), No. e79283.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Naba A; Clauser KR; Hoersch S; Liu H; Carr SA; Hynes RO The Matrisome: In Silico Definition and In Vivo Characterization by Proteomics of Normal and Tumor Extracellular Matrices. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11 (4), M111–014647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Geiger T; Velic A; Macek B; Lundberg E; Kampf C; Nagaraj N; Uhlen M; Cox J; Mann M Initial Quantitative Proteomic Map of 28 Mouse Tissues Using the SILAC Mouse. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2013, 12 (6), 1709–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zhang X; Hines W; Adamec J; Asara JM; Naylor S; Regnier FE An Automated Method for the Analysis of Stable Isotope Labeling Data in Proteomics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2005, 16 (7), 1181–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Karp NA; Huber W; Sadowski PG; Charles PD; Hester SV; Lilley KS Addressing Accuracy and Precision Issues in ITRAQ Quantitation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9 (9), 1885–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hogrebe A; Von Stechow L; Bekker-Jensen DB; Weinert BT; Kelstrup CD; Olsen JV Benchmarking Common Quantification Strategies for Large-Scale Phosphoproteomics. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 03309–6 DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Naba A; Clauser KR; Ding H; Whittaker CA; Carr SA; Hynes RO The Extracellular Matrix: Tools and Insights for the ″Omics″ Era. Matrix Biol. 2016, 49, 10–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Stendahl JC; Kaufman DB; Stupp SI Extracellular Matrix in Pancreatic Islets: Relevance to Scaffold Design and Transplantation. Cell Transplant 2009, 18 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Prasadan K; Shiota C; Xiangwei X; Ricks D; Fusco J; Gittes G A Synopsis of Factors Regulating Beta Cell Development and Beta Cell Mass. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2016, 73, 3623–3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).van der Meulen T; Huising MO Maturation of Stem Cell-Derived Beta-Cells Guided by the Expression of Urocortin 3. Review of Diabetic Studies 2014, 11, 115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).van der Meulen T; Xie R; Kelly OG; Vale WW; Sander M; Huising MO Urocortin 3 Marks Mature Human Primary and Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Pancreatic Alpha and Beta Cells. PLoS One 2012, 7 (12), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Blum B; Hrvatin S; Schuetz C; Bonal C; Rezania A; Melton DA Functional Beta-Cell Maturation Is Marked by an Increased Glucose Threshold and by Expression of Urocortin 3. Nat. Biotechnol 2012, 30, 261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Megger DA; Pott LL; Ahrens M; Padden J; Bracht T; Kuhlmann K; Eisenacher M; Meyer HE; Sitek B Comparison of Label-Free and Label-Based Strategies for Proteome Analysis of Hepatoma Cell Lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2014, 1844 (5), 967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Li Z; Adams RM; Chourey K; Hurst GB; Hettich RL; Pan C Systematic Comparison of Label-Free, Metabolic Labeling, and Isobaric Chemical Labeling for Quantitative Proteomics on LTQ Orbitrap Velos. J. Proteome Res 2012, 11, 1582–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Uhlen M; Oksvold P; Fagerberg L; Lundberg E; Jonasson K; Forsberg M; Zwahlen M; Kampf C; Wester K; Hober S; et al. Towards a Knowledge-Based Human Protein Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol 2010, 28, 1248–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Bergman J; Botling J; Fagerberg L; Hallstrom BM; Djureinovic D; Uhlen M; Ponten F The Human Pancreas Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling. Endocrinology 2016, 158 (2), 239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mason MN; Arnold C a.; Mahoney, M. J. Entrapped Collagen Type 1 Promotes Differentiation of Embryonic Pancreatic Precursor Cells into Glucose-Responsive Beta-Cells When Cultured in Three-Dimensional PEG Hydrogels. Tissue Eng., Part A 2009, 15 (12), 3799–3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Llacua LA; Hoek A; de Haan BJ; de Vos P Collagen Type VI Interaction Improves Human Islet Survival in Immunoisolating Microcapsules for Treatment of Diabetes. Islets 2018, 10 (2), 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kato A; Okamoto O; Ishikawa K; Sumiyoshi H; Matsuo N; Yoshioka H; Nomizu M; Shimada T; Fujiwara S Dermatopontin Interacts with Fibronectin, Promotes Fibronectin Fibril Formation, and Enhances Cell Adhesion. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286 (17), 14861–14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Zhang H; Apfelroth SD; Hu W; Davis EC; Sanguineti C; Bonadio J; Mecham RP; Ramirez F Structure and Expression of Fibrillin-2, a Novel Microfibrillar Component Preferentially Located in Elastic Matrices. J. Cell Biol 1994, 124 (5), 855–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Beattie GM; Montgomery AMP; Lopez AD; Hao E; Perez B; Just ML; Lakey JRT; Hart ME; Hayek A A Novel Approach to Increase Human Islet Cell Mass While Preserving Beta-Cell Function. Diabetes 2002, 51 (12), 3435–3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hayek a.; Beattie GM; Cirulli V; Lopez a D.; Ricordi C; Rubin JS Growth Factor/Matrix-Induced Proliferation of Human Adult Beta-Cells. Diabetes 1995, 44 (12), 1458–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Nagata N; Gu Y; Hori H; Balamurugan a N.; Touma M; Kawakami Y; Wang W; Baba TT; Satake A; Nozawa M; et al. Evaluation of Insulin Secretion of Isolated Rat Islets Cultured in Extracellular Matrix. Cell Transpl 2001, 10 (4−5), 447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lucas-Clerc C; Massart C; Campion JP; Launois B; Nicol M Long-Term Culture of Human Pancreatic Islets in an Extracellular Matrix: Morphological and Metabolic Effects. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 1993, 94 (1), 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Griffiths LG; Choe LH; Reardon KF; Dow SW; Christopher Orton E Immunoproteomic Identification of Bovine Pericardium Xenoantigens. Biomaterials 2008, 29 (26), 3514–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Beretta B; Conti A; Fiocchi A; Gaiaschi A; Galli CL; Giuffrida MG; Ballabio C; Restani P Antigenic Determinants of Bovine Serum Albumin. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol 2001, 126 (3), 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Cirulli V; Beattie GM; Klier G; Ellisman M; Ricordi C; Quaranta V; Frasier F; Ishii JK; Hayek A; Salomon DR Expression and Function of Alpha(v)Beta(3) and Alpha(v)Beta(5) Integrins in the Developing Pancreas: Roles in the Adhesion and Migration of Putative Endocrine Progenitor Cells. J. Cell Biol 2000, 150 (6), 1445–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Venn diagram represents the overlap between ECM and ECM- associated proteins detected in technical replicates by SCAD (A), FASP (B), urea (C); Figure S2: Scheme of different categories of proteins extracted from decellularized pancreas; Figure S3: Scheme of different categories of proteins extracted from native pancreas and the rationale of applying novel correction factor; Figure S4: Venn diagram represents the overlap between ECM and ECM- associated proteins detected in biological replicates in decellularized adult (A), native adult (B), decellularized fetal (C), and native fetal (D); the proteins were colored based on their subcategories: collagens (blue), ECM glycoproteins (purple), proteoglycans (teal), ECM-affiliated proteins (orange), ECM regulators (light orange), secreted factors (pink) (PDF)

Table S1: List of identified ECM proteins by each sample preparation method (XLSX)

Table S2: Illustration of labeling strategy with 10-plex DiLeu; deuterated tags are marked in yellow (XLSX)

Table S3: Quantitative information on matrisome protein abundance in each of the subcategories (XLSX)

Table S4: List of identified ECM proteins by two developmental stages (adult, fetal) under native and decellularized conditions (XLSX)