Abstract

The U.S. opioid epidemic is a critical public health problem. As substance use and misuse typically begin in adolescence and emerging adulthood, there is a critical need for prevention efforts for this key developmental period to disrupt opioid misuse trajectories, reducing morbidity and mortality [e.g., overdose, development of opioid use disorders (OUD)]. This article describes the current state of research focusing on prescription opioid misuse (POM) among adolescents and emerging adults (A/EAs) in the U.S. Given the rapidly changing nature of the opioid epidemic, we applied PRISMA Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines to identify empirical articles published in the past 5 years (January 2013 - September 2018) from nine databases examining POM among A/EAs (ages 10-25) in the U.S. Seventy-six articles met our inclusion criteria focusing on POM in the following areas: cross-sectional surveys (n=60), longitudinal cohort studies (n=5), objective, non-self-reported data sources (n=9), and interventions (n=2). Final charted data elements were organized by methodology and sample, with results tables describing design, sample, interventions (where applicable), outcomes, and limitations. Most studies focused on the epidemiology of POM and risk/protective factors, including demographics (e.g., sex, race), individual (e.g., substance use, mental health), and social (e.g., peer substance use). Despite annual national surveys conducted, longitudinal studies examining markers of initiation and escalation of prescription opioid misuse (e.g., repeated overdoses, time to misuse) are lacking. Importantly, few evidence-based prevention or early intervention programs were identified. Future research should examine longitudinal trajectories of POM, as well as adaptation and implementation of promising prevention approaches.

Keywords: prescription opioids, opioid misuse, opioid abuse, adolescents, emerging adults, scoping review

Introduction

The United States’ (U.S.) opioid epidemic is a serious public health problem [1] given opioid-related overdose deaths [1–5], underscoring the need for programs to prevent the initiation and escalation among adolescents and emerging adults (A/EAs). Prescription opioid misuse (POM, in this review: medical misuse of prescription opioids [POs] for reasons other than prescribed [i.e., to get high], or not taken as prescribed [e.g., higher doses, crushing and snorting, injecting], and/or use without a prescription) has spurred the current epidemic [3], with significant morbidity and mortality. POM is implicated in 46 deaths per day in the U.S.; accounting for more than one-third of opioid-related overdose deaths [1]. PO consumption via non-injection routes is often a precursor to using more potent, high-risk street opioids (i.e., heroin, fentanyl analogs; [6, 7]) with more hazardous routes of administration (e.g., injection). Current epidemiological figures support a developmental pattern to POM, like other misused substances (e.g., alcohol, cannabis), with initiation typically in adolescence, and prevalence peaking during emerging adulthood (and declining thereafter).

It is critical to synthesize recent knowledge to inform priorities for prevention research, particularly for adolescents and emerging adults (A/EAs), to prevent initiation of POM and escalation to consequences such as impaired functioning and/or OUD given earlier initiation of POM (in particular non-medical use) is associated with increased odds of later OUD [8]. Recent POM literature reviews among A/EAs are generally lacking; prior reviews focused on non-medical prescription drug use, not POs specifically [9, 10]. In one exception, a systematic review and meta-analysis of articles from 1990 to 2014 reported POM prevalence, finding past-year prevalence in 11-30-year-olds ranged from <1% to 16.3%, increasing approximately 0.40% per year across 1993 to 2010 [11]. A prior descriptive review summarized POM risk factors relevant for pediatric oncology treatment (before 2015), which included: female sex, older age, academic problems, childhood sexual trauma, prior opioid prescriptions, other substance use, psychiatric concerns, and peer influences [12].

Extending prior work, we conducted a scoping review of recent U.S. literature (that included data from 2010 or later), characterizing the current state of knowledge of POM among A/EAs in order to inform research and interventions focusing on prevention of POM initiation and escalation. A scoping review was chosen because, consistent with prior definitions [13], we sought to provide an overview of current research in a relatively broad field with a variety of study designs. We address research questions pertaining to POM prevalence, risk and protective factors, trajectories of use and misuse, and interventions among A/EAs in the U.S. We focus on POs, as opposed to heroin or fentanyl as POM typically occurs before heroin/fentanyl initiation [6, 7] and because rates of heroin/fentanyl use among A/EAs are quite low [14]. Further, the purpose of this review is to inform POM prevention efforts among A/EAs in the context of the current U.S. opioid epidemic. We examine POM broadly, given varied definitions of medical and non-medical misuse [11]. We describe results for adolescent-only, EA-only, and combined A/EA samples separately, given developmental changes and the potential need to tailor interventions and research studies for different ages. Note that topics including interventions delivered in specialty treatment for OUD (e.g., medication assisted treatment) and examining the impact of legal (e.g., prescription drug monitoring programs [PDMPs]) or institutional policies (e.g., implementation of prescribing guidelines, physician education) were outside the scope of this review which sought to illuminate gaps and directions for future prevention research and programming delivered to A/EAs directly.

Methods

Informed by Arksey and O’Malley’s [13] framework for scoping reviews and the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines [15], we: 1) identified research questions, 2) searched for relevant studies, 3) selected studies meeting inclusion criteria, 4) abstracted data from selected studies, and 5) organized and report results. Per PRISMA-ScR guidelines, we describe the protocol for this review below. Note that scoping reviews do not provide a quality assessment or critical appraisal nor is pooling of data conducted [13, 15]. This research was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Literature Search.

We systematically searched nine databases from two providers, EBSCO and Embase, with the most recent search executed on September 12, 2018. Search strategies were limited to English language articles published between January 2013 and September 2018 (see Appendix for search strategy details) in order to capture articles more likely to reflect the current U.S. opioid epidemic.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria.

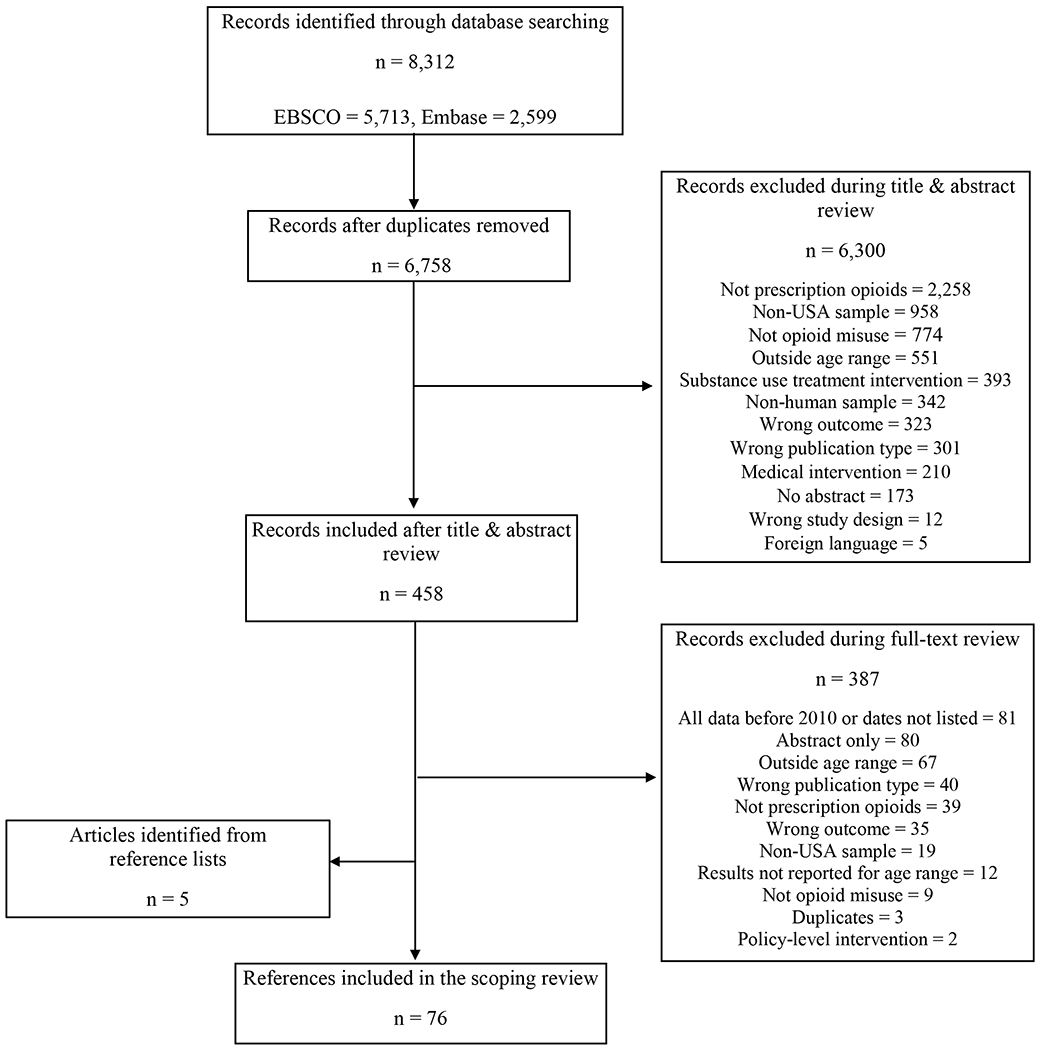

To identify articles pertaining to A/EAs’ POM, our review inclusion criteria were: 1) described human consumption of POs; 2) addressed POM initiation, risk/protective factors, access, outcomes, or intervention approaches; 3) reported results for participants ages 10-25; 4) data collected in the U.S.; 5) included data collected in 2010 or later; 6) written in English language; 7) full-length paper (i.e., not a published abstract); and 8) published in a peer-reviewed journal. Figure 1 details exclusion reasons.

Figure 1:

Adolescent and Emerging Adult Prescription Opioid Misuse Article Identification

Data Abstraction.

We exported citations from initial database searches into Mendeley Desktop (Elsevier Inc.) software, removed duplicates, and then exported unique citations into the systematic review software, Rayyan version 1.19.1, for title and abstract review [16]. Two reviewers assessed each abstract; a third reviewer resolved disagreements. Two reviewers conducted full-text reviews, further assessing inclusion/exclusion criteria, to identify included articles. We reviewed reference lists in five review articles identified in the search [9–12, 17] for additional articles to include. We developed an electronic codebook for extracting and organizing data items from each article into initial tables with fields to capture study purpose, design, data collection methods, intervention description, setting and sample characteristics, results, limitations, and conclusions.

Synthesis of Results.

We refined extracted data (Tables 1–4). To inform prevention efforts, we organized articles by sample age group (adolescents only [ages 10-17]. EAs only [ages 18-25], or both A/EAs), data source, including annual nationally representative surveys (e.g., Monitoring the Future [MTF]. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [NSDUH]) or other sources, and methodology (i.e., cross-sectional, longitudinal cohort, intervention, non-self-reported objective data such as medical chart review or insurance claims data), summarizing key findings below. Many articles addressed multiple research questions (e.g., prevalence and risk factors) and are discussed throughout the results.

Table 1.

Included Articles featuring Cross-sectional Survey Study Designs

| # | 1st author, year | Design | Sample | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Epidemiological Samples | |||||

| Adolescents Only | |||||

| 19 | Veliz et al., 2013 | Survey (annual, MTF, 2010-2011) | Weighted N=13,636 8th & 10th graders |

• General participation in sports not associated with NMUPO. •Risk factors: Female sex, 10th vs. 8th grade, White race, lower grades, suspension, & participation in 2011 vs. 2010. •Football & wrestling associated with NMUPO (vs. no sports). |

• Does not include medical misuse. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. |

| 18 | Veliz et al., 2016 | Survey (annual, MTF, 1997-2014) | N=191,660 8th & 10th graders |

• Lifetime prevalence: 7.6% NMUPO; 1.1% started in 4th-7th grade, 3.2% in 8th-10th grade. • Lifetime NMUPO ↓ from 1997-99 through 2012-14; regardless of sports/exercise. • Past-year sports/exercise protective for NMUPO. |

• Variations in question wording & examples for NMUPO. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. |

| 72 | Ali et al., 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2008-2012) | N = 84,800 Ages 12-17 with NMUPO initiation prior to depression onset |

• NMUPO initiation 2 years before current age for all youth. • Risk factors: Higher SES, substance use, & mental health treatment receipt. • Teens with NMUPO 33%-35% more likely to experience a major depressive episode. |

• Propensity score matching cannot address all heterogeneity. • Methods to reduce reverse causality bias may have attenuated main effects. • High-risk youth (e.g., jail & treatment) not included. |

| 69 | Donaldson et al., 2015 | Survey (one-time, NSDUH, 2012) | N = 17,399 Ages 12-17 |

• Lifetime NMUPO: 4.4% (ages 12-14) & 11.7% (ages 15-17). • Risk factors: pro-substance social ties & attitudes & among ages 12-14, high parental monitoring with low warmth or low parental monitoring with high warmth. |

• NMUPO motivations & NMUPO attitudes/norms not asked. • High-risk youth not included. |

| 20 | Edlund et al., 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2008 – 2012) | N=112,600 Ages 12-17 |

• 6.1% past-year NMUPO, 0.9% past-year OUD. • Past-year major depressive episode associated with NMUPO and OUD, moderated by moderate/high level of family supervision and age (strongest for 14-15-year-olds). • NMUPO risk factors: older, white, female, other substance use diagnosis, lower socioeconomic status, delinquency. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Cannot differentiate if depressive episode caused by depression or bipolar. • High-risk youth not included. |

| 22 | Ford & Rigg, 2015 | Survey (one-time, NSDUH, 2012) | N=15,648 Ages 12-17 |

• POM prevalence did not differ by race. Risk factors (varied by race): delinquency, depression, peer use, tobacco use, binge drinking, other prescription misuse & illicit drug use. • Protective factors: parent bond & negative use attitudes (self, peer, parent). |

• High-risk youth not included. |

| 24 | Monnat & Rigg, 2016 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2011-2012) | N=32,036 Ages 12-17 |

• POM: 6.8% rural, 6.0% small urban, & 5.3% large urban. • Risk factors: rural & small urban, female, Black, prior crime, substance use, depression, ED visits, peer substance use, mental health hospitalizations, & ease of obtaining drugs. • Sources: rural (vs. urban) more likely source from a physician or dealer & less likely from family/friends. |

• High-risk youth not included. |

| 25 | Nicholson et al., 2016 | Survey (one-time, NSDUH, 2013) | N=15,124 Ages 12-17 African-Americans |

• 5% past year NMUPO. • Risk factors: substance using peers, poor school, & parental bonds. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Perceived peer substance use measure may not capture actual use. |

| 73 | Stabler et al., 2015 | Survey (one-time, NSDUH, 2010) | N=15,745 Ages 12-17 |

• Youth who moved 1-2 times in 5 years (vs. 0 moves) more likely to report NMUPO. 3+ moves (vs. 0) not related to NMUPO. | • High-risk youth not included. |

| 68 | Vaughn et al., 2016 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2004-2013) | N=164,028 Ages 12-17 |

• Past-year NMUPO: 5.5-6.9%. • Risk factors: Female, older age, White non-Hispanic (↓use until no race differences in 2013), other drug use, & fighting; also: lower income, poor grades, & binge drinking in some race/ethnic groups. • Protective factors: parental involvement & religiosity. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Unable to examine additional racial/ethnic subgroups. |

| Both Adolescents & Emerging Adults | |||||

| 41 | Housman et al., 2017 | Survey (one-time, MTF, 2015) | N not reported 12th graders | ~6% past-year non-medical opioid use. • Energy drinks & energy shots predicted non-medical Vicodin use; only energy shots predicted non-medical OxyContin use. |

• Findings only report non-medical use of Vicodin & OxyContin. |

| 42 | Housman et al., 2018 | Survey (one-time, MTF, 2015) | N=4,561 12th graders |

• 3.8% past-year non-medical OxyContin use & 4.6% past-year non-medical Vicodin use. • Greater frequency of non-medical OxyContin & Vicodin use associated with greater energy drink & alcohol use. |

• Findings only report non-medical use of Vicodin & OxyContin. |

| 29 | McCabe et al., 2013a | Survey (annual, MTF, 2007-2010) | N=8,888 12th graders |

• In 2010, past-year NMUPO 8.7%. • Sources: 55% friend/relative for free, 38% bought from friend/relative; 37% leftover, & 19% bought from dealer. • Leftover prescriptions (ED most common source) more likely used for pain; other sources more likely used to get high. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. |

| 30 | McCabe et al., 2014 | Survey (annual, MTF, 2002-2011) | N=24,809 12th graders |

• Past-year NMUPO: 8.1%. • NMUPO less likely at party & more likely at home; common use alone & with others. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. |

| 31 | McCabe et al., 2017a | Survey (annual, MTF, 2005-2015) | N=26,502 12th graders |

• Risk factors: lives in Midwest or West, recent skipped class, first time drunk or marijuana use before 9th grade. • Hispanic, Black, & ‘Other’ races had greater odds of past-month NMUPO. • High-intensity drinking ↑ risk for NMUPO & co-ingestion. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Findings may be biased since data collection occurred in schools. |

| 32 | McCabe et al., 2017b | Survey (annual, MTF, 1976-2015) | 40 cohorts (2,181 – 3,791 students each) 12th graders |

• ↓ lifetime prevalence from 2013-15 (~7-8%). • Lifetime NMUPO correlated with medical PO use; effect stronger for males, & African-American & White youth. • NMUPO more common among White teens. • Most initiated medical use before NMUPO. |

• Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Missed students (e.g., absence) were more likely to report substance use. |

| 33 | Palamar et al., 2015a | Survey (annual, MTF, 2011-2013) | Weighted N = 7,373 12th graders |

• 15.7% of rave attendees vs. 6.6% of non-rave attendees had past-year NMUPO, 7.1% vs. 2.0%, respective, had past-year NMUPO 6+ times. • NMUPO higher among frequent rave attendees. |

• Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Doesn’t include medical misuse. • Unclear rave attendance definition & if drug use took place in raves. |

| 35 | Palamar et al., 2015b | Survey (annual, MTF, 2000-2011) | N = 6,562 12th graders Used marijuana in the last year |

• Most common drug was NMUPO: 17.9%. • Risk factors: lower experimental motives for marijuana use, higher drug effect motives, greater past 12-month alcohol use, smoking cigarettes, & more frequent marijuana use. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Doesn’t include medical misuse. |

| 36 | Palamar et al., 2016a | Survey (annual, MTF, 2009-2013) | N=31,149 12th graders |

• 8.3% NMUPO in past year. • 37.1% of those using non-medical Vicodin & 28.2% of those reporting non-medical OxyContin use did not report NMUPO, prevalence of opioid misuse may be underreported. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Differential missing data by items |

| 37 | Palamar et al., 2016b | Survey (annual, MTF, 2009-2013) | N=67,896 12th graders Complete data for nonmedical opioid & heroin use |

• Lifetime NMUPO 12%; dose-response relationship between NMUPO & lifetime heroin use. • NMUPO risk factor: higher weekly student income. • NMUPO protective factors: female, non-White, large MSA residence, religiosity, lives with 2 parents. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Systematic missingness in key variables may bias results. |

| 34 | Palamar et al., 2018 | Survey (annual, MTF, 2010-2016) | N=92,242 12th graders |

• Lifetime NMUPO: 10.8%; Past-month heroin use: 0.4% • In 327 past-month heroin users, lifetime NMUPO was 76.7%. • More frequent NMUPO related to more frequent heroin use. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Medical misuse not included. |

| 38 | Schaefer & Petkovsek, 2017 | Survey (one-time, MTF, 2012) | N=2,390 12th graders |

• Past 12-month NMUPO: 9%. • Risk factors: drug-using peers, low self-control, perceived opportunity to obtain POs, sports involvement (females only). |

• Sport type, parent influence, and NMUPO motives (recreational or enhancement) not asked. |

| 78 | Terry-McElrath et al., 2016 | Survey (annual, MTF, 1991-2014) | N=379,887 8th, 10th & 12th graders |

• Past-year frequency of narcotics other than heroin ↑ by grade and negatively associated with frequency of sleeping 7+ hours; this effect significantly ↓ as grade level ↑. | • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Sleep item may not detect individual differences. |

| 39 | Veliz et al., 2017 | Survey (annual, MTF, 2006-2014) | N = 21,577 12th graders |

• Past-year prevalence: 8.3% narcotics w/o a doctor’s prescription; 0.9% heroin, 0.6% both. • Risk factors narcotic use: weightlifting, wrestling, & ice hockey; risk factor heroin: weightlifting & ice hockey. • General, sports participation & number of sports not associated with narcotic/heroin outcomes; soccer protective. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Medical misuse not assessed. |

| 40 | Biondo & Chilcoat, 2014 | Survey (annual, NSDUH & MTF, 2005-2010) | N=15,127 from MTF & N=3,020 from NSDUH 12th graders |

• Past-year nonmedical OxyContin prevalence higher in MTF (5.1%) vs. NSDUH (1.9%) in 2010. • NMUPO prevalence ~15% lower in MTF vs. NSDUH (8.7% vs. 9.8% in 2010). |

• High-risk youth not included. |

| 43 | Cerdá et al., 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2004-2011) | N=223,534 Ages 12-17 |

• NMUPO: 14.2%; initiation most common at 16-18 (45%) or 13-15 (33%) yrs. • Youth initiating NMUPO at age 10-12 or 13-15 more likely to initiate heroin use (vs. ages 19-21); those with NMUPO ~13 times more likely to initiate heroin. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • High-risk youth not included. |

| 21 | Fink et al., 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2011-2012) | N=36,663 Ages 12-17 & 18+ |

• 5.8% of adolescents had past-year NMUPO, of those 19.9% met depression criteria. • Females more likely to report NMUPO & depression • Past-year drug & alcohol use disorder, & lower SES status associated with NMUPO alone, and NMUPO & depression. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Did not explore subgroup differences. |

| 23 | Hu et al., 2017 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2002-2014) | N = 542,556 Ages 12-34 |

• Past-year NMUPO 4.8% (ages 12-17) & 7.6% (ages 18-25); ↑ for ages 14-17, peaked at ages 18-21, & ↓, ages 22+. • More recent cohorts had lowest rates of NMUPO, NMUPO rates ↓ for ages 14-25 from 2010+ (vs. earlier). • OUD rates low & decrease until age 21; also, ↓ for ages 12-17 but ↑ for ages 22-25 between 2002 – 2005 & 2014. |

• Variable operationalization could have negatively impacted precision of results. • High-risk youth not included. |

| 7 | Jones, 2013 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2002-04 & 2008-10) | N=334,295 Ages 12+ |

• ↑ heroin use 2002-10 in 18-25 year-olds with any NMUPO. • No changes in heroin use in 18-25 without NMUPO. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Temporal order of NMUPO and heroin initation unknown if at same age. |

| 45 | Jones, 2017 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2003-2014) | N not reported Ages 12+ | • In 2012-2014, past-year NMUPO: 48.9/1000 (ages 12-17), 88.8/1000 (ages 18-25); past-year OUD 6.0/1000 (ages 12-17), 15.1/1000 (ages 18-25). • Past-year NMUPO ↓ from 2003-2014 (ages 12-17 & 18-25). • Past-year OUD ↓ for ages 12-17 (2003-14), stable for ages 18-25 who (vs. ages 35+) were higher risk for OUD. |

• High-risk youth not included. |

| 46 | Jones, 2018 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2003-2014) | N not reported Ages 12+ |

• Among ages 18-25 with lifetime NMUPO, PO injection rates increased 140% from 2003-2014. • Among those with NMUPO, < age 25 (vs. 26+) less likely to inject; youth misusing PO < age 18 more likely to inject. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Injection assessed most recent use instead of typical behaviors. |

| 80 | Kozhimannil et al., 2017a | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2005-2014) | N=8,721 Ages 12-44 |

• Pregnant women ages 12-25: 63.3% past-year NMUPO & 67.8% past-month NMUPO. • Pregnant women ages 12-25 more likely to report past-year & past-month NMUPO (vs. pregnant women ages 26+). |

• High-risk youth not included. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| 28 | Martins et al., 2017 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2002-2014) | N=41,059 Ages 12-34 Youth nonmedical PO users |

• Ages 12-17, past-year NMUPO ↓ 2002-14 (7.5% to 4.8%). • Ages 18-25, past-year NMUPO use ↓ (11.4% to 7.6%), prescription OUD ↑ (12.0 to 15.1%) & past-year heroin use among NMUPO ↑ four-fold (2.1% to 7.4%). • Age of first NMUPO typically < age of first heroin use. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Data are not available regarding motives for opioid use initiation. |

| 44 | Parker & Anthony, 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2002-2013) | N= 330,983 Ages 12-21 |

• ~1% of ages 12-13 initiate extra-medical PO use; peak at 16-17 & 18-19 years, declining at 20-21. • For every 11-16 new extra-medical users, 1 develops OUD within a year (~120 new youth/day); highest risk ages 14-15. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Rates may be underestimated because not all are assessed 1 year after initiating use. |

| 47 | Saloner et al., 2016 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2006-2013) | N=34,690 Ages 12+ |

39.7% with past-year NMUPO were ages 12-25. • Although friends/family most common sources of POs, ages 12-25 (vs. ages 26-49) more likely to report physician as source of misused POs. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| 27 | Stanley et al., 2014 | Survey (annual, ADAS, 2009-2012). | N=1,399 8th, 10th & 12th graders American Indians (AI) on or near reservations |

• Lifetime narcotics other than heroin & OxyContin: 10.4% & 6.3% (8th); 16.4% & 10.3% (10th), 12.0% & 12.9% (12th) • Past-year narcotics other than heroin & OxyContin: 2.0% & 5.0% (8th): 2.9% & 6.4% (10th), 2.5% & 9.1% (12th). • Past-year OxyContin prevalence higher in Al students vs. MTF national rates for all 3 age groups. |

• Excludes dropouts/truant youth. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Sample isn’t random & doesn’t reflect the Alaska Native population. |

| 52 | Osborne et al., 2017 | Survey (four waves, N-MAPSS, 2008-2011) | N=10,965 Ages 10-18 |

• 3.2% past 30-day NMUPO. • Risk factors: male sex; among females, alcohol use (most robust) & marijuana use; among males, marijuana use. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| Emerging Adults Only | |||||

| 66 | Kozhimannil et al., 2017b | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2005-2014) | N=154,179 Ages 18-44 |

• In both pregnant & non-pregnant women, NMUPO more likely in 18-25-year-olds (vs. older) •Ages 18-25 more likely to get POs friend/relative or dealer. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • High-risk youth (e.g., jail & treatment) not included. |

| 59 | Martins et al., 2015 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2008-2010) | N=36,781 Ages 18-22 |

• Past-year NMUPO: 11.3% college students, 13.1% with high school diploma/GED, 13.2% with < high school diploma. • Risk factors for NMUPO and OUD: male, non-Hispanic white, psychological distress, less education. Non-Hispanic black race was protective. |

• High-risk youth not included. • Initiation methods (illegally or prescribed) not asked. |

| 85 | McCabe et al., 2018 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2009-2014) | N=106,845 Ages 18-25 |

• Past year POM: 11.9% non-college, 8.6% college, 7.1% college graduate & 9.0% high school. • Among non-college, POs more likely purchased than given for free by family/friends. • Those with multiple sources most likely to binge drink, use marijuana or have a substance use disorder. |

• Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. • Misuse included non-medical & medical misuse. |

| 60 | Rigg & Monnat, 2015a | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2010-2013) | N = 10,201 Ages 18+ |

• Ages 18-25 comprised 27% of heroin only users, 33% of PO only users, & 42% of those who used both. •More 18-25-year-olds used heroin & POs vs. heroin only (vs. older ages). |

• High-risk youth not included. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| 61 | Rigg & Monnat, 2015b | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2011-2012) | N=47,440 Ages 18+ |

• Of past-year non-medical PO users, 34% were ages 18-25 (vs. 14% of non-users, & 15% in the combined sample). | • High-risk youth not included. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| 62 | Salas et al., 2016 | Survey (annual, NSDUH, 2012-2013) | N=55,030 Ages 18+ |

• 18-25-year-olds comprised 12.4% of non-users, 30.4% of non-medical PO users, & 31.3% of those with abuse/dependence. | • High-risk youth not included. • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| 84 | Ford et al., 2018 | Survey (bi-annual; 2008-2011 NCHA) | N=344,533 Ages: 18-30 |

• Ages 24-26 (vs. ages 18-20) associated with greater past-year NMUPO, but being ages 21-23 was not significant. | • Data pooled over time & time trends not examined. |

| Other Self-Reported Data Sources | |||||

| Adolescents Only | |||||

| 26 | Forster et al., 2017 | Survey (one-time, Minnesota, 2013) | N=104,332 8th, 9th, & 11th graders. |

• 1.67% reported past-year NMUPO. • 47% increase in the likelihood of past year NMIPO for every additional adverse childhood event. |

• Generalizability limited outside of participating schools. |

| 54 | Al-Tayyib et al., 2018 | CIDI-SAM assessment (one-time, 2009-2013) | N=378 Ages 13-18 Patients from substance use treatment in Denver |

• Lifetime NMUPO 16.4%; 15.6% opioid/heroin abuse or dependence; average age of first NMUPO 14.3 years. • White, non-Hispanics more likely NMUPO & opioid/heroin abuse/dependence. • Risk factors for NMUPO & opioid/heroin abuse/dependence: substance use diagnosis. |

• Generalizability limited to convenience treatment sample. • Due to low heroin prevalence, opioid & heroin abuse/dependence collapsed. |

| Both Adolescents & Emerging Adults | |||||

| 48 | Boyd et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, SSFS, 2009-2010) | N=2,627 Middle & high school students Michigan |

• 5.1% reported lifetime NMUPO for pain r sensation seeking. • Sensation seeking motives related to more psychological symptoms & substance-related problems (vs. non- or medical users). |

• Generalizability limited, since sample is school-based & from a small geographic area. |

| 74 | McCabe et al., 2013b | Survey (one-time, 2011-2012) | N=2,964 7-12th graders 2 Detroit public schools |

• 17.9% medical misuse among those prescribed opioids. • Medical or non-medical misuse motives: pain & get high. • Those with pain motives 15 times more likely to report past-year substance abuse. • Females more likely to misuse than males. |

• Did not assess opioid dosage or pain diagnoses. • Generalizability limited, school-based sample from a small region. |

| 81 | Biggar et al., 2017 | Survey (one-time, CCYS FA, 2014) | N > 83,000 6th-, 8th-, 10th-, & 12th graders |

• Nonmedical use of POs was significantly correlated with use of marijuana, FSD, stimulants & sedatives. | • Generalizability limited, since sample is school-based & from one state. |

| 82 | Vosburg et al., 2016 | Survey (one-time, 2010) | N=31 Age not reported PO misusers in MA recovery high schools |

• Mean age of POM initiation =15 yrs, typically preceded by alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana. • Most POM initiated with Oxycodone that was obtained (for free or bought) from friends/family. |

• Generalizability limited by small, convenience sample. Use of in-house questionnaire as opposed to valid |

| 50 | Bonar et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, 2010-2012) | N=2,127 Ages 14-20 Sexually active ED patients |

• Past 12-month NMUPO: 10.9%. • NMUPO associated with sexual risk behaviors. |

• Generalizability limited since data were collected from one ED. • Sexual risk behavior measure did not account for monogamous partnerships and/or use of other contraception. |

| 51 | Whiteside et al., 2013 | Survey & chart review (one-time, 2010-2011) | N=2,135 Ages 14-20 ED patients |

• Past-year NMUPO: 8.7% (14.6% from current prescription). • Risk factors: other substance use, intravenous PO in the ED, drinking and driving/riding with a drinking driver. |

• Generalizability limited since data were collected from one ED. |

| 53 | Rhoades et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, 2012-2013) | N=451 Ages 13-? Homeless CA youth |

• Among 21.6% reporting past 30-day POM: 24.5% opioids only, 15% multiple types (of those 15%, 71% used sedatives & opioids, 7% used sedatives, stimulants & opioids). | • Generalizability limited due to convenience sample of homeless youth. |

| 79 | Saroyan et al., 2016 | Interview & UDS (one-time, 2008-2011) | N= 50 Ages 10-20 Pediatric pain patients |

• 22% were non-adherent (all had chronic non-cancer pain), & 7 had opioid prescriptions (6/7 non-adherent to regimen) • Non-adherence highest among 18-20-year-olds. • Some discordant urine drug tests. |

• Limited sample size. • Non-adherence included appropriately stopping medications (e.g., side effects). |

| 83 | Wong et al., 2013 | Survey (one-time, 2009 – 2011) | N=560 Ages 16-25 Prescription drug misuse 3+ times in past 90 days |

• Compared to “active copers,’ youth classified as “suppressors,’ “others-reliant” (emotional or instrumental support-seeking), or “self-reliant copers” more likely to have initiated POM at an earlier age. | • Findings may not generalize to youth who aren’t high-risk or youth in non-metropolitan areas. |

| 49 | Zullig et al., 2015 | Survey (one-time, 2010-11) | N=4,148 9th-12th graders in 5 schools |

• Lifetime NMUPO: 18.8%. • Risk factors: suicide risk among both men & women. |

• Different timeframes assessed for NMUPO and suicide risk. |

| Emerging Adults Only | |||||

| 64 | Peralta et al., 2016 | Survey (one-time, 2013-2014) | N = 796 Ages 18-25 Midwestern university students |

•Lifetime NMUPO 15%: Vicodin (12.1% total, 14.3% men, 1.1% women) more common than Tramadol & OxyContin. • Risk factor: depression. • Protective factors: femininity (vs. masculinity). |

• Only some opioids included. • Generalizability may be limited due to convenience sample. |

| 88 | Carlson et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, 2009-2010) | N=390 Ages 18-25 Respondent-driven, 5+ NMUPO days, Ohio. |

• Using latent class analysis, the class with the highest proportion of youth only using to self-medicate had the least number of negative characteristics. | • Generalizability limited due to convenience sample. |

| 67 | Daniulaiyte et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, 2009-2010) | N=383 Ages 18-23 Respondent-driven, 5+ NMUPO days, Ohio. |

• 87.7% got POs from friends for free, 80.2% bought POs, 46.7% had a prescription, and 44.1% obtained from family. | • Generalizability limited due to convenience sample. |

| 63 | Sanders et al., 2014 | Survey (one-time, 2011-2012) | N= 2,349 Ages not reported. Southern undergraduates. |

• 4.9% past-month recreational prescription pain medication use. • 75.8% believed typical student engages in POM (past-month). • Females more likelv to overestimate peer use than males. |

• Generalizability limited due to convenience sample. |

Note: ADAS: American Drug & Alcohol survey; CA: California; CCYS: Communities that Care Youth Survey; CIDI-SAM: Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Substance Abuse Module; ED: Emergency Department; GED: General Education Diploma; LA: Louisiana; MA: Massachusetts; MSA: Metropolitan Statistical Area; MTF: Monitoring the Future; NCHA: National College Health Assessment; N-MAPSS: National Monitoring of Adolescent Prescription Stimulants Study; NMUPO: Non-Medical Use of Prescription Opioids; NSDUH: National Survey on Drug use and Health; OUD: Opioid use disorder or abuse/dependence diagnosis; PO: Prescription Opioids; POM: Prescription Opioid Misuse; SES: socioeconomic status; SSLS: Secondary Student Life Survey; UDS: Urine drug test

Table 4.

Included Articles featuring Interventions

| # | 1st author, year | Design | Sample | Intervention | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents Only | ||||||

| 94 | Spoth et al., 2013 | Cluster RCT of schools in 3 studies initiated in 1993, 1998, and 2002 Outcomes assessed during 12th grade or young adulthood |

N varied 6th & 7th graders in schools in IA & PA |

• Study 1: Strengthening Families Program (SFP; n=446) •Study 2: SFP + Life Skills Training Program (LST) in 7th or 11th grade (n=226) • Study 3: SFP + 1 of 3 programs in 7th grade (n=1,062): All Stars, LST, or Project Alert. |

• Study 1: SFP alone showed 65% relative ↓ in rates of POM across risk level groups at age 25. • Study 2: SFP + LST showed 32-60% ↓ in POM at age 21, 22, and 25, with higher risk participants (baseline use of 2+: alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana) showing greater relative ↓ in rates of POM (43-79%). • Study 3: SFP + one of 3 interventions showed 21% relative ↓ in rates of POM across risk levels in 12th grade. |

• Sample sizes for analyses unclear. • Intervention dose received was unclear. |

| 95 | Crowley et al., 2014 | PROSPER cluster RCT (2002-2010) Outcomes assessed during 12th grade or young adulthood |

N varied 6th & 7th graders in schools in IA & PA |

• Strengthening Families program in 6th grade (n=827) • Plus, 1 of 3 programs in the 7th grade (n=526): All Stars, LST, or Project Alert. |

• LST + SFP most effective in reducing NMUPO, followed by All Stars + SFP, relative to control. • LST alone reduced NMPOU relative to control; All Stars and Project Alert alone did not. • Although LST had the lowest cost, effects ↑ when combined with SFP, although at greater cost. |

• Implementation requires capacity building to prevent diminished impact. • Cost estimates likely undervalue total societal costs of NMPOU. |

Note: IA: Iowa; NMUPO: Non-Medical Use of Prescription Opioids; PA: Pennsylvania; POM: Prescription Opioid Misuse; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial.

Results

Article Identification and Selection.

The EBSCO search resulted in 5,713 citations and the EMBASE search in 2,599, totaling 8,312. After removing duplicates, we reviewed titles and abstracts of 6,758 articles resulting in 458 remaining articles for full-text review, leading to 71 articles meeting inclusion criteria. When reviewing references in the identified review articles, we added five papers meeting inclusion criteria, resulting in 76 included articles (Figure 1).

Recent Epidemiology of POM.

Tables 1–3 include studies reporting A/EAs’ POM prevalence and epidemiology.

Table 3.

Included Articles Featuring Longitudinal Study Designs

| # | 1st author, year | Design | Sample | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both Adolescents & Emerging Adults | |||||

| 77 | Miech et al., 2015 | Survey (4 time points, MTF, baseline dates of 1990-2012) | N=6,220 12th graders who completed baseline in 1990-2012 and answered PO misuse items in ≥1 follow-up survey at ages 19-23 |

• Baseline risk factors for NMUPO: opioid prescription, lifetime marijuana use on 6+ occasions, any cigarette smoking, lifetime prescription drug misuse, recent binge drinking, parent with college degree. • Baseline protective factors for NMUPO: regular marijuana use disapproval, average grades, racial/ethnic minority. • Baseline legitimate opioid use → 33% likely to misuse later. |

• Data are self-reported. • Truant or drop-out youth not included. |

| 75 | McCabe et al., 2013c | Survey (2 time points, SSLS, 2009-2010 & 2010-2011) | N=2,050 Middle & high school students in southeastern MI |

• 25% of those reporting NMUPO in Year 1 used in Year 2. • In year 1: past-year NMUPO for pain relief was more prevalent among females (vs. males). |

• Generalizability limited to sample from 5 schools in one state; truant or drop-out youth not included. |

| 76 | Veliz et al., 2014 | Survey (3 time points, SSLS, 2009-2012) | N=1,494 Middle & high school students in southeastern MI who completed 3 waves of data collection |

• Females higher rates than males of medical misuse (use too much) and NMUPO, pooling data from 3 yrs. • Risk factors: athletic involvement over time for men, but not women. |

• Generalizability: sample from 5 schools in one state; truant or drop-out youth not included. |

| 89 | Austic et al., 2015 | Survey (4 time points, SSLS, 2009-2013) | N=5,185 middle and high school students (ages 12-18) in southeastern MI | • Time until first NMUPO less for more recent birth cohorts (1996-2000) than older birth cohorts (1991-95). • Those receiving their first prescription before age 12 initiated NMUPO earlier. |

• Generalizability: sample from 5 schools in one state; truant or drop-out youth not included. |

| Emerging Adults Only | |||||

| 91 | Carlson et al., 2016 | Survey (6 time points, 2009-2013) | N=362 Ages 18-23 Respondent-driven, 5+ NMUPO days, Ohio. |

• Over 36 months, 7.5% initiated heroin use, rate of 2.8% per year; mean heroin initiation at 6.2 years of NMUPO. • Risk factors for transition to heroin: white race, developing PO dependence, beginning PO use < age 15, never reporting NMUPO for self-medicating health condition, lifetime NMUPO by sniffing/snorting, more frequent NMUPO, & more dependence symptoms. |

• Generalizability: geographically constrained (conducted in an opioid epidemic “hot spot”). |

Note: MI: Michigan; MTF: Monitoring the Future; NMUPO: Non-Medical Use of Prescription Opioids; PO: Prescription Opioid; SSLS: Secondary Student Life Survey

Adolescents.

Two MTF studies reported adolescent POM prevalence, with pooled data (1997-2014) indicating lifetime prevalence at 7.6% [18]. In 2010-2011, past-year prevalence was 5.5% for Vicodin/OxyContin misuse [19]. NSDUH studies reported past-year POM prevalence at 5-6% (ages 12-17; approximately 2008-2013) [20–25], whereas a Minnesota high school survey reported 1.67% past-year prevalence [26]. Notably, prevalence data show OxyContin misuse was more common among American Indians than overall narcotic use and more common in this group than in the general adolescent population [27]. NSDUH data suggest that adolescents’ past-year POM prevalence is decreasing, from 7.51% (2002) to 4.82% (2014) [28]. See Table 1.

Both Adolescents and Emerging Adults.

As shown in Table 1, among MTF 12th graders (A/EAs, given inclusion of age 18), lifetime and past-year POM prevalence were 10-12% and 8-9%, respectively [29–40]. MTF data from 2015 found lower annual POM rates of 3.8-6.0% [41, 42], with decreasing lifetime POM from 12% to 7-8% over 2013-2015 [32]. NSDUH data show lifetime and past-year rates at 14% [43] and 9.8% [40], respectively. Pooling NSDUH data (2002-2013), approximately 1% of 12-13-year-olds initiated POM, which increased for ages 16-17, remained stable for ages 18-19, and declined at ages 20-21 [44]. NSDUH data also suggest reductions in past-year POM (most recent data for 2014) for A/EAs, with higher rates among EAs [28, 45]; OUD rates have reduced among adolescents, but are stable (and higher) or increasing in EAs [28, 45]. PO injection is more common for EAs than adolescents [46]. In terms of sources, NSDUH and MTF data show that more than half of A/EAs obtain POs from family/friends [29, 47], the most common source. When considering people reporting physicians as their PO source in NSDUH data, 12-25-year-olds were more likely than adults ages 26-49 to report physicians as a source of POs used non-medically [47].

In other cross-sectional data, lifetime prevalence was 5.1% in Michigan middle and high school students [48], and 18.8% among high school students from West Virginia, Illinois, California, New Jersey, and Florida [49]. Among a general sample of Emergency Department (ED) patients, past-year POM prevalence was 8.7-10.9% [50, 51]. Regarding past 30-day POM, a national survey found 3.2% prevalence among 10-18-year-olds [52] and among homeless youth, about 5% reported POM alone plus approximately 2.5% reporting POM with concurrent misuse of sedatives or stimulants [53]. Among youth in substance use treatment, 16.4% surveyed had lifetime POM [54]. PO poisoning hospitalizations related to suicide or self-injury increased between 1997 and 2012 (ages 15-19), as did hospitalizations for PO poisonings [55] and Ohio opioid misuse treatment admissions from 2008-2011 [56]. Likewise, data show annual increases in A/EA opioid poisoning calls from 2005-2010 [57], and 71.5% of PO exposures involve intentional behaviors, with opioid misuse attributable to suspected suicide increasing 52.7% (2000-2015) [58]. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Included Articles using objective Data Sources

| # | 1st author, year | Design | Sample | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents Only | |||||

| 70 | Tadros et al., 2016 | Claims data (annual, Nationwide ED Sample, 2006-2012) | N=21,928 Ages 0-17 ED visits for PO poisoning |

• Majority of ED visits for intentional PO overdoses were among ages 15-17. | • Retrospective data collected for other purposes. • Can’t discern circumstances of poisoning (e.g., recreational vs. self-harm). |

| 71 | Chung et al., 2018 | Medicaid claims data (Tennessee, 1999-2014) | ~401,972/year Ages 2-17 1+ past year claim |

• For ages 12-17 (vs. younger), a greater proportion of PO-related adverse events due to abuse/withdrawal or self-harm. | • Generalizability limited to recent healthcare users from one state in a region with elevated opioid use. |

| Both Adolescents & Emerging Adults | |||||

| 58 | Allen et al., 2017 | Records (annually, National Poison Data System, 2000-2015) | N=188,468 Age <20 Single-substance opioid exposures |

• For ages 13-19, most PO were exposures intentional (34.2% suicide, 20.8% PO abuse, 11.2% PO misuse). •POM attributable to suicide ↑ by 52.7% from 2000–2015 in teens. |

• Generalizability limited to self-reported exposures. • Data are de-identified; therefore, repeat exposures cannot be identified. |

| 55 | Gaither et al., 2016 | Discharge records (every 3 years, Kids’ Inpatient Database, 1997-2012) | N=13,502 hospitalizations for opioid poisonings for youth under age<19 | • Hospitalizations among ages 15-19 ↑ 176% across years (with ↓ from 2009-2012). • Hospitalizations for suicide/self-injury & unintentional injury ↑ overtime for ages 10-14 & 15-19. • Suicide/self-injury more common than unintentional injury. |

• Cross-sectional, precludes causality. • Unclear if opioids were prescribed. • Limitations in medical coding, patients may be represented more than once in the data if hospitalized more than one time in a year. |

| 57 | Sheridan et al., 2016 | Records (National Poison Data System, 2004-2013; NAMCS & NHAMCS, 2005-2010; & SEER, 2005-2010) | N=4,186 calls Ages 13-19 |

• Annual increase in opioid abuse calls & total # of opioid prescriptions (2005-2010). • Midwest highest yearly opioid abuse calls. • For each opioid prescription ↑ per 100 people/year, annual opioid abuse call rate ↑. |

• Ingestion exposure data are self-reported and may be coded differently across call centers. |

| 90 | Brat et al., 2018 | Medical & pharmacy claims data (Aetna database, 2008-2016) | N=1,015,116 Ages <15 to >65 Surgical claims from opioid-naive patients |

• Among ages 15-24, POM rate of 420.6 per 100,000, median time to POM 1.47 years. • Highest POM rates in males ages 15-24. |

• Data may not capture all prescriptions. • Findings may be influenced by over-coding. |

| 56 | McKnight et al., 2017 | Treatment admission and pharmacy fills (annually, Ohio, 2008 – 2012) | N not reported Ages 12-20 and adults >20 |

• Fewer prescriptions & lower doses prescribed to ages 12-20 than >20. • Treatment rate for ages 12-20 ↑ 20% from 2008-11, but ↓ 25% in 2012 to 2009 levels. |

• Generalizability limited to claims from one state. • Treatment admissions likely underestimate POM. |

| Emerging Adults Only | |||||

| 87 | Garg et al., 2017 | Medicaid claims data (Washington state, April 2006-December 2010) | N=328,445 Ages 18–64 ≥1 opioid prescription |

• Ages 18-24 less likely to die of opioid related deaths than other ages. | • Generalizability limited to Medicaid fee-for-service patients from a single state. • Data pooled over time, time trends not examined. • Data may not capture all prescriptions. |

| 65 | Mack et al., 2013 | Surveillance data (NVSS, cause of death fdes 1999-2010; DAWN, ED visits, 2004-2010) | N=15,323 Women ages 18-65+ |

• Among ages 18-24, PO overdose death rates 2.6/100k women in 2010. • Among ages 18-24, ED visit rate for opioid misuse or abuse was 204.6 per 100k women. |

• Cross-sectional data. • True overdose rates underestimated due to death certificate inaccuracies (i.e., missing drug type, misclassified race/ethnicity). |

Note: DAWN: Drug Abuse Warning Network; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – IV; ED: Emergency Department; NAMCS: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; NHAMCS: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; NVSS: National Vital Statistics System; OUD: Opioid Use Disorder; PO: Prescription Opioid; POM: Prescription Opioid Misuse; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Emerging Adults.

From 2008-2010, past-year POM prevalence was 11.3-13.2%, depending on educational status [59], although using pooled data (2002-14) another study reported 7.6% past-year prevalence [23], consistent with the 2014 rate [28]. EAs comprised 30-35% of all individuals reporting past-year POM [60–62]. Among EAs with lifetime POM, PO injection increased 140% from 2003-2014 [46]. Among college students, past-year POM was 4.9% [63]; lifetime prevalence was 3.4-12.1%, depending on PO type [64]. The rate of women’s ED visits for opioid misuse/abuse was highest among EAs [65]. EAs with recent POM were more likely to report a dealer, friend, or relative (and not physicians) as their source for POs [66, 67]. See Table 1.

Demographic, Individual, and Social Risk and Protective Factors.

Adolescents.

In Table 1, Female sex was consistently a demographic risk factor for POM [20, 21, 24, 68], as was older age and/or higher grade level [19, 20, 27, 68, 69]. Four studies identified White race [19, 20, 54, 68] and one identified Black race [24] as associated with higher POM risk while another study found no race differences in POM [22]. Adolescents comprised the majority of pediatric ED visits for intentional PO overdoses (ages 15-17) [70] and opioid-related adverse events (including self-harm) [71]. Three studies reported lower SES [20, 21, 68], whereas, one study found higher SES [72] was a POM risk factor. Rural residence and residential instability (1-2 moves in the past 5 years) increased POM risk [24, 73]. Religiosity (e.g., importance, attendance at services) was protective against POM [68].

Individual Factors.

Other substance use, including binge drinking [22, 68], was a consistent POM risk factor [20, 22, 24, 54, 68, 72], as was perceived ease of obtaining illicit drugs [24]. Mental health problems [48], depression [20, 22, 24] or related hospitalization [24, 72] were risk factors, as was ED utilization [40]. Adverse childhood events [26] and behavioral problems (e.g., suspension, fighting, and delinquency) were also POM risk factors [7, 19, 20, 22, 68].

Social Factors.

Negative personal, peer, and parental attitudes toward use were protective against POM [22]; positive personal and peer substance use attitudes increased risk [69], as did peer substance use [22, 24, 25]. Parenting factors (e.g., high bond, involvement, monitoring/warmth) were protective [22, 68, 69]. Youth with lower grades had greater POM risk [19, 68]. In MTF data, the association between sports involvement and POM was mixed (either no association or protective); however, youth playing football or wrestling were at higher risk [18, 19, 39].

Both Adolescents and Emerging Adults.

Different studies identified female [74–76] and male sex as risk factors [37, 52]. Two MTF reports found minority identities [77], and Hispanic/Black identities [37], were protective against POM (vs. White). Among high intensity alcohol drinkers, Hispanic, Black, and Other races were associated with increased risk of past-month POM (vs. White) [31]. In contrast, American Indians living on/near reservations had higher rates of OxyContin use than national samples [27]. Two studies found EAs had higher risk than those ages 35+ [45] and 12-17 [46] for POM and PO injection. Similarly, two studies found that past-year frequency of narcotic use other than heroin [78] and aberrant behaviors (i.e., POM, [79]) were heightened among older A/EAs versus younger adolescents. Pregnant A/EAs were more likely to report POM than older pregnant women [80]. Religiosity was protective for POM [37]. Socioeconomic risk factors included higher weekly student income [37] and having a parent with a college degree [77]. Living in a higher density location was protective [37]; residence in the Midwest and West increased POM risk [31].

Individual Factors.

Other substance use was a common POM risk factor, including: cigarette smoking [35, 77], alcohol/high intensity drinking [31], use of marijuana [31, 35, 52, 77, 81, 82]. LSD, sedative, barbiturates, and/or stimulants [77, 81], energy drinks [41], more frequent heroin use [34], and initiating alcohol or marijuana use before 9th grade [31]. Perceived ease of obtaining opioids [38], having an opioid prescription [77] and medical opioid use [32], including intravenous opioids received during ED care [51], were also POM risk factors. One study found a combined indicator of drinking and driving or riding with a drunk driver [51] was a POM risk factor.

Mental health POM risk factors included suicide risk behaviors [49]. Sexual risk behaviors were associated with increased POM risk [50]. Although one study found weight lifting and wrestling were POM risk factors, and playing soccer was protective [39], another found a general increased risk for POM in sports-involved females, but not males [38]. Skipping class [31], lower self-control [38], not using adaptive coping strategies [83] and reporting medical misuse motives to reduce pain and to get high [74] were also risk factors.

Social Factors.

One study found a higher frequency of attending raves was a POM risk factor [33]. Living with two parents was protective [37].

Emerging Adults.

Demographic POM risk factors included male sex [59], non-Hispanic White identity [59], older age (24-26 vs. 18-20, [84]), and lower education/non-college involvement [59, 85]. Lower education [59, 86] was a risk factor for OUD; protective factors for OUD included Non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity [59] and college involvement [85]. In Medicaid claims (Table 2), EAs were less likely to die of an opioid-related death than older ages [87].

Individual Factors.

POM risk factors included psychiatric distress and depression [59, 64]. Feminine gender orientation (measured distinctly from biological sex) was protective in one study [64]. Past-year psychiatric distress was an OUD risk factor [59], whereas using POs only to self-medicate was protective [88].

Longitudinal Trajectories of Prescription Opioid Misuse.

Both Adolescents and Emerging Adults.

In Table 3, A/EAs who received a medical prescription before age 12 initiated POM earlier than those who did not [89], and 25% of students with POM persisted a year later [75]. Continuous sports involvement was a risk factor for POM over time for men, but not women [76]. Using surgical claims data (Table 2), opioid naive A/EAs had a rate of misuse at 420.6 per 100,000 person years, with time to misuse occurring a median of 1.5 years after surgery [90].

Emerging Adults.

One 3-year study followed EAs with POM in Ohio to examine the course of POM, finding that 2.8% transitioned to heroin per year ([91], Table 3). Risk factors for transition included: White race, PO dependence symptoms, PO initiation at young ages, absence of health-related self-medication motives, sniffing/snorting, and more frequent POM [91].

Interventions.

Adolescents.

Two articles (Table 4) reported secondary effects on POM of evidence-based prevention programs for other substance use among 6th and 7th graders in three cluster-randomized trials: the Strengthening Families Program (SFP) and the Life Skills Training Program (LST). SFP involves six 2-hour sessions for youth and parents, plus one family session, focused on parenting skills and family relationships, delivered in the school’s community. SFP reduces alcohol and other drug use, and other problem behaviors and improves school performance [92]. LST consists of 15 teacher-delivered classes in one year, with additional booster lessons in years 2 and 3, focused on personal management, social skills, and substance use resistance skills [93]. Although not designed specifically for POM, secondary analyses show that SFP and LST resulted in POM reductions at ages 21-25 [94]. LST, combined with SFP, was the most effective for POM; however, LST alone had the lowest cost [95]. The combination of SFP and LST was most effective in high-risk youth (e.g., 2+ substances) [94].

Discussion

This scoping review discovered that most recent studies of A/EAs’ POM focus on epidemiology using annual national surveys (e.g., 42 using NSDUH or MTF, 22 with study-specific methods, 9 with objective sources). Annual national prevalence estimates range from 4.8-7.5% among adolescents [28] and 7.6-13.2% among EAs [23, 59]. Variations likely reflect data collection year and differing types and definitions of POM. For example, past-year prevalence estimates of 12th graders’ nonmedical OxyContin use were about 2.5 times higher in MTF than NSDUH; NSDUH’s inclusion of a pictorial pill card could yield more precise estimates [40]. Prevalence appears higher in sub-samples (e.g., American Indians, pregnant women) and older versus younger A/EAs, supporting the need for increased primary prevention programming (for all youth in a setting regardless of risk) earlier in adolescence, with more intensive, selective or secondary prevention interventions (given to those at-risk) among older adolescents and emerging adults.

Recent data on risk and protective factors could inform personalized interventions and determination of sub-groups requiring more intensive interventions. Demographic risk factors include sex, with adolescent females having higher POM rates than males. In A/EAs, findings for sex were mixed, potentially reflecting motives, with females more commonly reporting medical misuse [32] and pain and relaxation motives [96], whereas males and females show similar rates of non-medical misuse [32]. Among A/EAs, White race was associated with increased POM risk; however, within subpopulations (e.g., high intensity drinkers), other races had higher risk. Findings regarding socioeconomic status and POM were mixed for A/EAs [20, 21, 37, 72, 77, 80], but lower educational attainment suggests increased POM and OUD risk among EAs [59, 85].

Most studies examined individual, and to a lesser extent social, POM risk factors; protective factors were under-studied. Among A/EAs, other substance use was a consistent risk factor [20, 22, 31, 35, 41, 42, 52, 54, 68, 72, 77, 81, 82]. Upstream approaches to prevent substance use initiation among universal samples could prevent POM. Consistent with research showing A/EAs often acquire POs from peers [22, 24, 25, 66, 67], peer substance use was a social risk factor. As some youth obtained POs from physicians, prescribers are also essential in limiting opportunities for use and diversion through adopting prescribing guidelines to limit the PO supply. Note, however, prescribing guidelines can have unintended effects in that reducing the PO supply from healthcare providers can potentially influence individuals to seek out street opioids, which may have greater potency and a higher risk profile. Next, other individual POM risk factors across A/EAs included: mental health (i.e., depression), behavioral problems (e.g., delinquency, lower academic performance), and sexual risk behaviors [19, 20, 22, 24, 31, 49, 50, 68]. Key protective factors included religiosity [37, 68], negative POM attitudes, perceived attitudes by social influences [22], and family factors (i.e., living with two parents, parental bond; [22, 37, 68]). Interventions addressing family and peer influences to prevent diversion or PO access, that also promote prosocial activities (e.g., religious service attendance or analogous secular activities) may bolster protective influences for at-risk A/EAs.

Current data pertaining to A/EAs’ longitudinal trajectories of PO use, including risk and protective factors for initiation, and escalation from use to misuse and OUD development are lacking. The field’s reliance on annual surveys of new cohorts precludes identifying which youth need selective prevention efforts to alter risk trajectories in the current opioid epidemic. Regarding the trajectory of PO use to misuse, longitudinal data indicate that receiving a prescription before age 12 increases risk for initiating misuse [89]. One-third of PO users later misuse [77], yet one study found that only 25% of adolescents continued POM one year later [75]. Such discrepancies highlight the need for research to identify markers of risk for future continued or escalated use. For example, risk factors for future POM included substance use whereas disapproval of regular marijuana use and better grades were protective [77]. Continuity of athletic involvement increased males’ POM risk, presumably due to exposure via sports injuries and/or peer diversion, although cross-sectional findings for athletic involvement are mixed. Finally, based on objective claims data, time from PO pharmacy fill to POM was about 18 months [90], whereas transition from POM to heroin misuse varied, occurring for some within a year, but most occurring over several years, with younger age of initiation and more frequent POM predicting transition [91]. These data, along with those showing PO fills after wisdom teeth extraction was more likely among older youth (vs. ages 13-15), and those with known risk factors for misuse (i.e., chronic pain, mental health issues, and/or prior prescription drug misuse [e.g., sedatives]), underscore the need for careful consideration of prescribing to youth and limiting doses [97]. Further, youth with known risk factors may benefit from monitoring and selective prevention programs to prevent escalation.

Recommendations for prevention

Implementation of evidence-based prevention interventions across settings for A/EAs at-risk for or with POM is urgently needed [98]. The Strengthening Families Program (SFP, [92]) and the Life Skills Training Program (LST, [93]; both described at blueprintsprograms.org), are promising, multi-session, universal prevention programs for adolescents, with effects lasting into emerging adulthood. Notably, selective prevention for at-risk or currently misusing A/EAs were lacking. In health care settings, screening to identify substance users, followed by brief interventions (Bis) for alcohol (UConnect, [99]) or marijuana (Chill, [100]) reduced prescription drug misuse (primarily opioids) among A/EAs. Similarly, Bis reduced POM in adults [101, 102]; however, modest BI effect sizes require enhancing. Because POM is multi-faceted, prevention interventions for A/EAs must be tailorable to individual use patterns, contexts, and severity, addressing motives for medical and non-medical use [29], other substance use to prevent overdose, and mental health given the role of opioids in suicide [103]. Consistent with the promising Bis above, interventions should be informed by behavior change theories (i.e., motivational interviewing [104], cognitive behavioral therapy [105]).

Limitations

Limitations include that studies published outside of January 2013-September 2018 were excluded; however, examining recent trends is justified given the recency of the current opioid crisis and publication lag meaning that articles published previously are less likely to contain data reflecting the current crisis. We did not include non-English and non-U.S. articles as our purpose was to inform U.S. prevention approaches; although work from other countries could be informative, prevention efforts should be culturally-tailored, therefore, U.S. data was most relevant for our purposes. Consistent with about half of published scoping reviews [106], we did not include grey literature. We focused on peer-reviewed research publications to identify evidence-based interventions and to provide an overview of current research. Excluding grey literature means that we may have missed some promising programs or unique information not represented in the peer-reviewed literature. Although it was beyond the scope of this prevention-focused review to examine legislation or public policy efforts, future reviews are warranted as such approaches can have intended and unintended consequences. For example, a recent study demonstrated that implementing comprehensive legislation mandates (i.e., Kentucky prescriber education, PDMP registration and usage) had the greatest impact on POM and heroin use among ED patients ages 18-24. While POM reduced by 73%, heroin use increased by 362% [107]. Finally, we did not examine substance use treatment interventions and youth with OUDs receiving treatment services (e.g., medication assisted treatment), given our prevention focus, which is a separate literature requiring future examination.

Directions for future research

Prevention research for A/EAs is needed in several key areas. First, although cross-sectional studies suggest many risk and protective factors, longitudinal examination of initiation and escalation of POM to identify how these factors influence trajectories of PO use to POM and related outcomes is needed. Research on risk and protective factors also lacks a unifying theoretical framework to guide construct inclusion. Second, research is needed to develop, test, and implement evidence-based, universal and selective interventions for the current, heterogeneous context of POM, which to date consist of secondary data analyses of opioid-related outcomes from programs targeting other substance use. The most efficient route to creating efficacious, scalable interventions could include adapting promising programs, such as community- and school-based universal prevention programs (e.g., Strengthening Families Program [92]. Life Skills Training Program [93]) and health care-based universal and selective prevention programs (UConnect [99]. Chill [100]) for the current POM context and generation of A/EAs. Similarly, recent evidence-based selective interventions for at-risk adults [101, 102]) could be revised for developmental relevance to A/EAs. Use of optimization frameworks (e.g., Multiphase Optimization Strategy [108]) and hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs [109], paired with cost-effectiveness measures to inform sustainability [95], could facilitate rapid impact of such interventions on preventing POM among A/EAs. Third, we again recognize the need for research on the impact of policies/legislation to reduce supply and diversion, given the vast majority of A/EAs obtain POs from family or friends [28, 45, 64, 65], which is particularly urgent given demonstrated unintended consequences of reducing the PO supply on heroin use [107]. Note that until efficacious prevention programs are in place, POM will continue, with some A/EAs escalating to OUD, thus the efficacy of addiction treatments for A/EA OUD should be examined.

Conclusion

Although prevalence varies, about one in twenty adolescents and one in ten EAs currently report POM, heightening risk for morbidity and mortality, as reflected in recent alarming rises in opioid poisoning deaths among A/EAs [1, 110]. Given this developmental peak in POM, early prevention is urgently needed to deter serious consequences (e.g., intentional and unintentional opioid overdose, other injury), especially for those with additional risks for adverse outcomes (e.g., substance use, mental health), and to prevent OUD. Partnering with community stakeholders (e.g., Families Against Narcotics) and using a participatory action approach [111] could help adapt promising programs [100–102, 112], to facilitate sustainable prevention approaches in communities. Specifically, engaging community stakeholders, and youth in particular, via participatory action-based partnerships (e.g., focus groups, co-design, planned implementation) can have the advantages of improving cultural relevance, promoting uptake of interventions and sustainability, and ensuring that interventions reflect current trends and terminology. Although longitudinal data is clearly needed to understand transitions from PO initiation, escalation to POM, and development of OUDs, in the meantime, hybrid effective implementation designs [109] could be used to accelerate translation of evidenced-based programs, including universal prevention programs (e.g., Strengthening Families Program) in schools and communities, and screening for POM and related risk factors in health care settings, followed by delivery of selective prevention interventions [99–102].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Most identified studies examined epidemiology of youth prescription opioid misuse.

Few studies explore opioid misuse trajectories or prevention program efficacy.

Future youth prevention research in these two areas is urgently needed.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to acknowledge Becky Turpin, Rachael Cooper, Claire Stroer, Brittnie Cannon, and Rachel Bresnahan for their assistance in data and manuscript preparation.

Funding: Research reported herein was supported by a grant to the University of Michigan Injury Prevention Center by the National Safety Council. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Safety Council or organizations from whom the National Safety Council has received contributions. Dr. Coughlin was supported by a NIAAA T32 (Grant number 007477) training grant during her work on this project. The UM Injury Prevention Center (Grant number CE002099) provided additional center funding to support the review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;67(5152):1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: 2017. [cited 2019 May 2], Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolodny A, Courtwright DR, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36(559-74). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths – United States, 2000-2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;64(50):1378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United StatesThe Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States, 2001-2016The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States, 2001-2016. JAMA Network Open. 2018; 1 (2):e180217–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States [Internet]. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2013. [cited 2019 April 9]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers – United States, 2002-2004 and 2008-2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1-2):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schepis TS, Hakes JK. Age of initiation, psychopathology, and other substance use are associated with time to use disorder diagnosis in persons using opioids nonmedically. J Substance abuse. 2017;38(4):407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapscott BE, Schepis TS. Nonmedical use of prescription medications in young adults. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2013;24(3):597–610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shehnaz SI, Agarwal AK, Khan N. A systematic review of self-medication practices among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(4):467–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan AE, Blackburn NA, Des Jarlais DC, Hagan H. Past-year prevalence of prescription opioid misuse among those 11 to 30 years of age in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peck KR, Ehrentraut JH, Anghelescu DL. Risk factors for opioid misuse in adolescents and young adults with focus on oncology setting. Journal of Opioid Management. 2016;12(3):205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology. 2005;8(1): 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Contract No.: HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adewumi AD, Hollingworth SA, Maravilla JC, Connor JP, Alati R. Prescribed Dose of Opioids and Overdose: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Unintentional Prescription Opioid Overdose. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2): 101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veliz P, Boyd CJ, McCabe SE. Nonmedical prescription opioid and heroin use among adolescents who engage in sports and exercise. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20160677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veliz PT, Boyd C, McCabe SE. Playing through pain: sports participation and nonmedical use of opioid medications among adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):e28–e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edlund MJ, Forman-Hoffman VL, Winder CR, Heller DC, Kroutil LA, Lipari RN, et al. Opioid abuse and depression in adolescents: Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fink DS, Hu R, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Marshall BDL, Galea S, et al. Patterns of major depression and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:258–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford JA, Rigg KK. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Factors That Place Adolescents at Risk for Prescription Opioid Misuse. Prevention Science. 2015;16(5):633–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu M- C, Griesler P, Wall M, Kandel DB. Age-related patterns in nonmedical prescription opioid use and disorder in the US population at ages 12-34 from 2002 to 2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monnat SM, Rigg KK. Examining Rural/Urban Differences in Prescription Opioid Misuse Among US Adolescents. The Journal of Rural Health. 2016;32(2):204–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicholson J, Dawson-Edwards C, Higgins GE, Walton IN. The nonmedical use of pain relievers among African-Americans: a test of primary socialization theory Journal of substance use. 2016;21(6):636–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster M, Gower AL, Borowsky IW, McMorris BJ. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, student-teacher relationships, and non-medical use of prescription medications among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2017;68:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanley LR, Harness SD, Swaim RC, Beauvais F. Rates of substance use of American Indian students in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades living on or near reservations: Update, 2009–2012. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(2):156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martins SS, Segura LE, Santaella-Tenorio J, Perlmutter A, Fenton MC, Cerdá M, et al. Prescription opioid use disorder and heroin use among 12–34 year-olds in the United States from 2002 to 2014. Addict Behav. 2017;65:236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover Prescription Opioids and Nonmedical Use Among High School Seniors: A Multi-Cohort National Study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):480–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, Frank KA, Boyd CJ. Social Contexts of Substance Use Among U.S. High School Seniors: A Multicohort National Study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):842–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe SE, Veliz P, Patrick ME. High-intensity drinking and nonmedical use of prescription drugs: Results from a national survey of 12th grade students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, McCabe VV, Stoddard SA, Boyd CJ. Trends in Medical and Nonmedical Use of Prescription Opioids Among US Adolescents: 1976–2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palamar JJ, Griffin-Tomas M, Ompad DC. Illicit drug use among rave attendees in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palamar JJ, Le A, Mateu-Gelabert P. Not just heroin: extensive polysubstance use among US high school seniors who currently use heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palamar JJ, Griffin-Tomas M, Kamboukos D. Reasons for recent marijuana use in relation to use of other illicit drugs among high school seniors in the United States. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2015;41(4):323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palamar JJ, Shearston JA, Cleland CM. Discordant reporting of nonmedical opioid use in a nationally representative sample of US high school seniors The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(5):530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]