Abstract

The healing of broken chromosomes by de novo telomere addition, while a normal developmental process in some organisms, has the potential to cause extensive loss of heterozygosity, genetic disease, or cell death. However, it is unclear how de novo telomere addition (dnTA) is regulated at DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Here, using a non-essential minichromosome in fission yeast, we identify roles for the HR factors Rqh1 helicase, in concert with Rad55, in suppressing dnTA at or near a DSB. We find the frequency of dnTA in rqh1Δ rad55Δ cells is reduced following loss of Exo1, Swi5 or Rad51. Strikingly, in the absence of the distal homologous chromosome arm dnTA is further increased, with nearly half of the breaks being healed in rqh1Δ rad55Δ or rqh1Δ exo1Δ cells. These findings provide new insights into the genetic context of highly efficient dnTA within HR intermediates, and how such events are normally suppressed to maintain genome stability.

INTRODUCTION

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are potentially lethal lesions if unrepaired, and their misrepair can give rise to chromosomal rearrangements, a hallmark of cancer cells (1,2). To maintain both viability and genome stability in response to such lesions cells have evolved two types of DSB repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). During classic non-homologous end joining (C-NHEJ), the broken ends are bound by the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, and following the removal of damaged bases, are ligated together through the activity of Ligase 4 (Lig4) (reviewed in (3)). During HR repair, homologous sequences within a chromatid or chromosome are used as a template for accurate repair. HR repair is initiated by nucleolytic resection of the 5′ end to generate a 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhang. Resection is a two-step process, which is initiated by the MRN complex (comprised of Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Sp) and in Homo sapiens (Hs)), and CtIP resulting in partly resected intermediates. During the second step, Exo1 together with Rqh1Sp (BLMHs) facilitates extensive resection (4–6) (reviewed in (7)). The 3′ ssDNA overhang is bound by Replication Protein A (RPA), which facilitates binding of the mediator Rad52,Sp and removal of secondary structures (8,9). Rad52Sp, together with the auxiliary heterodimers Rad55Sp–Rad57Sp or Swi5Sp–Sfr1Sp mediate the loading of the RecA homologue, Rad51Sp onto the ssDNA overhang to create a Rad51 nucleoprotein filament. This structure facilitates a homology search and strand exchange between the broken end and the homologous sequence to form a displacement-loop (D-loop) structure (10–13). Following DNA synthesis the invading strand can be expelled by BLM and RecQL5 in mammalian cells, thus facilitating synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA). Alternatively, second-end capture and ligation can result in a double-Holliday junction structure, which can be resolved with or without crossovers, a process involving Yen1, Mus81Sp–Eme1Sp, or dissolved through the activities of BLM-Top3 (reviewed in (14)).

Consistent with multiple roles in HR-dependent DSB repair, the RecQ family of DNA helicases plays a key role in maintaining genome stability in all organisms (15). A hallmark of BLM mutations in human cells is increased levels of sister chromatid and inter-homolog exchanges (16). In fission yeast, loss of the BLM orthologue, Rqh1, results in increased genome instability and sensitivity to DNA damaging agents (17,18). Rqh1 is an ATP-dependent 3′ to 5′ helicase, in which the N-terminus interacts with Top3 (19,20). Rqh1 has been implicated in a variety of processes including HR, both before and after Rad51 filament formation (19,21,22); suppressing mitotic crossovers and promoting meiotic crossovers (23–25); suppressing inappropriate recombination following S phase arrest (17,18); facilitating the repair of collapsed replication forks (26–28); intra-S checkpoint function (29); efficient chromosome segregation (30) and telomere maintenance (31,32). A role for Rqh1 has also been identified in regulating HR-dependent Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) pathway in the absence of Taz1 in fission yeast (33).

While normally repaired by the NHEJ or HR pathways, broken chromosome ends can sometimes be ‘healed’ as a result of telomeric capture or de novo telomere addition (dnTA). While dnTA is part of the normal developmental process in unicellular ciliates, chromosome healing in mammalian cells is associated with terminal deletions and genetic disease (34,35). Indeed, chromosome healing of a break within the body of a chromosome would be expected to result in extensive loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or potentially cell death through loss of genetic material centromere-distal to the break site. Accordingly, dnTA is not normally observed in response to ionizing radiation (IR) or enzyme-induced DSBs in yeasts or mammals (36–38), and may reflect the absence of telomeric seed sequences close to the break site, low levels or inhibition of telomerase, or competition with DSB repair pathways (39–41).

Here, we have investigated the relationship between DSB repair and loss of heterozygosity arising through dnTA. By introducing a site-specific DSB into a non-essential minichromosome, Ch16, we have uncovered a critical role for Rqh1 helicase, together with Rad55 in suppressing chromosome healing through dnTA at break sites. Further analysis suggests that stabilized HR intermediates are efficient substrates for dnTA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media and genetic methods

All S. pombe strains were cultured, manipulated, and stored as previously described (42). A list of strain genotypes can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

DSB assay

The DSB assay using Ch16–MGH was performed as previously described (41,43). The minichromosome (Ch16) is a mitotically and meiotically stable 530 kb chromosomal element derived from ChIII (44). The DSB assay was performed at 25°C for strains containing the cold-sensitive mutant pfh1-R20cs (45) and appropriate comparison strains as indicated in the tables. The colony percentage undergoing NHEJ/SCR (ade+ G418R his+), GC (ade+ G418S his+), Ch16-MGH loss (ade− G418S his−), or LOH (ade+ G418S his−) were calculated. LOH in this context refers to events which retain the ade+ marker but have lost the G418S marker. It is not possible to distinguish genetically between minichromosome loss and other rearrangements resulting in ade− G418S his− colonies, such as isochromomosome formation, using Ch16-MGH so this population is collectively termed here ‘Ch16 loss’. Each experiment was performed three times using independently derived strains for all mutants tested. More than 1000 colonies were scored for each time point. Mean ± SEM values were obtained from triplicate strains. Differences were deemed significant if P-values obtained using Student's t test were ≤0.05.

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

The PFGE protocols used in this study have been previously described (42). For higher resolution separation of Ch16-MGH, a 1.2% chromosomal grade agarose gel was used under the following conditions: 4 V/cm 112° angle with a switch time of 1 min. Samples were separated for 48 h in 1× Tris–acetate–EDTA at 14°C.

PCR assay for de novo telomere addition

Up to 20 randomly chosen ade+ G418s his− (LOH) colonies from each genetic background indicated were screened for telomeric sequence distal to the MATa break site as described. PCR amplification with primers targeted to the rad21 gene (5′-GATTTAAACCTGGATTTGGGC-3′) and telomeric repeats (5′-CTGTAACCGTGTAACCGTAAC-3′) was performed, followed by digestion with MfeI, yielding a distinct 300 bp band in telomere-positive strains.

Rapid DSB-induction

Strains encoding urg1::hph were generated and urg1::HO containing strains subsequently generated by cassette exchange as previously described (46). Strains were grown at 32°C in 500 ml of pombe minimal glutamate media (PMG) containing G418 (200 μg/ml), leucine and arginine (100 μg/ml) but lacking adenine, uracil and histidine (47). To induce urg1::HO expression, cultures were grown to an OD595 nm of 0.3–0.5. Cells were harvested, washed with water and suspended in PMG containing leucine, adenine, histidine, arginine (100 μg/ml) and uracil (250 μg/ml). 50 ml samples were harvested, washed in water with 0.5% sodium azide then stored at −80°C.

Gene targeting

Plasmid pJK148 (48) was linearized with NdeI restriction, and transformed into the strains indicated the using Lithium Acetate protocol (47), and the number of Leu+ transformants determined for each strain. The gene targeting efficiency was adjusted according to the relative transformation efficiencies of each strain, as determined using a circular pREP81X (49) as a control.

RESULTS

Rqh1 suppresses loss of heterozygosity in rad55Δ

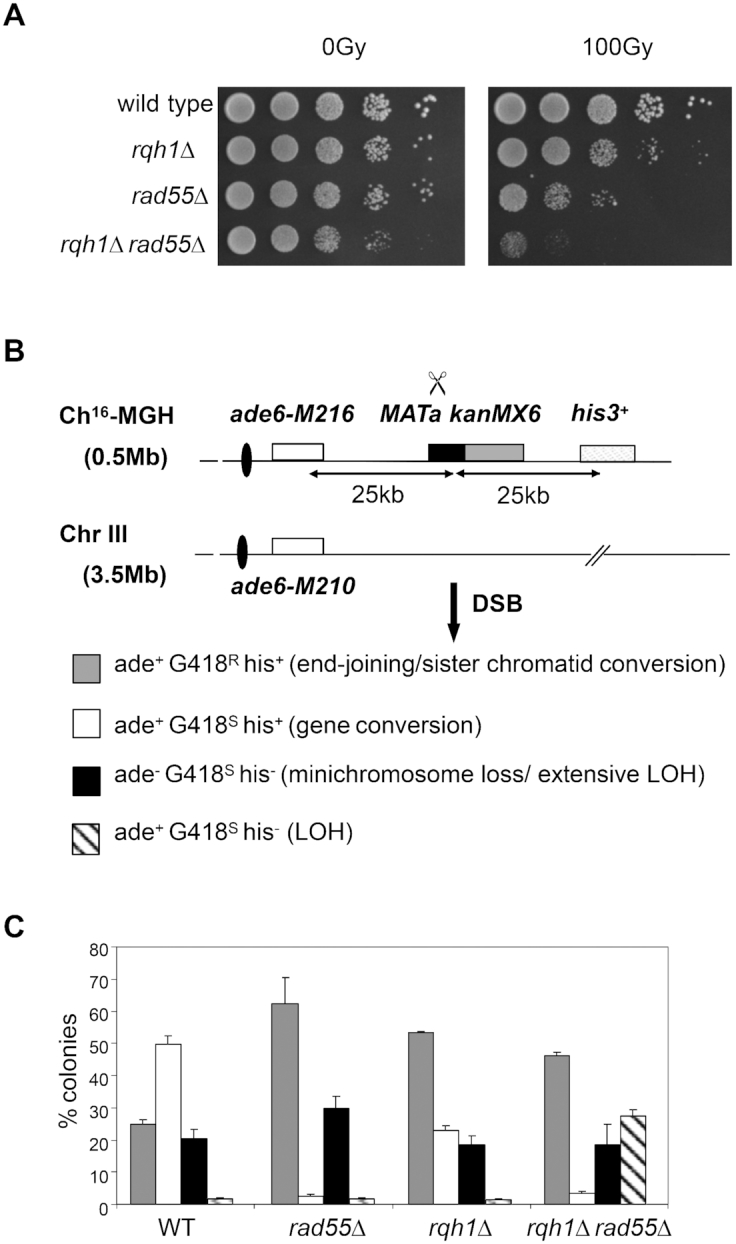

To investigate the role of Rqh1 in genome stability, we examined the relationship between Rqh1 and other DNA recombination genes in the cellular response to DSBs. We found that deletion of rqh1+ in a rad55Δ background resulted in a significant increase in the IR-sensitivity of rad55Δ (Figure 1A). To investigate this further, we examined the relationship between rad55Δ and rqh1Δ deletion mutants using a site-specific DSB assay. Using this assay, different repair and misrepair events can be quantitated by determining genetic marker loss following HO endonuclease induction of a site-specific DSB at the MATa site inserted within a non-essential minichromosome, Ch16-MGH, derived from chromosome III (Figure 1B). Ch16-MGH carries an ade6-M216 heteroallele which complements the ade6-M210 heteroallele on ChIII to confer an ade+ phenotype through intragenic complementation (50). Following HO endonuclease expression from a thiamine-repressible nmt promoter (rep81X-HO) DSB induction can result in a variety of outcomes: DSB repair through NHEJ or sister chromatid recombination (SCR) in which a broken chromatid uses its unbroken sister chromatid as a repair template; failed DSB repair with loss of the minichromosome; gene conversion using the homology of chromosome III; extensive loss of heterozygosity, resulting through break-induced non-reciprocal translocations or partial loss of heterozygosity (Figure 1B) (41).

Figure 1.

Rqh1 suppresses break-induced LOH in a rad55Δ background. (A) Spot dilutions of wild-type (TH1900) rad55Δ (TH1760) rqh1Δ (TH1807) and rqh1Δ rad55Δstrains (TH2136) strains grown on YES plates following exposure to 0 Gy, or 100 Gy IR, as indicated. (B) Schematic of the Ch16-MGH strain and ChIII as previously described. The loci of the centromeres (black oval), ade6-M216 and ade6-M210 alleles (white boxes), MATa target site (black box), kanMX6 gene (gray) and his3+ gene (striped) are as indicated. pREP81X-HO generates a DSB at the MATa target site (scissors). The expected marker loss profiles associated with different repair outcomes are indicated. (C) Site-specific DSB repair profile of wild-type (TH1900), rqh1Δ, rad55Δ and rad55Δrqh1Δ strains following HO-endonuclease induction for 48 h. Data are derived from Table 1.

Surprisingly, HO endonuclease-induced cleavage at the MATa site in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ double mutant resulted in a striking increase in LOH (27.3%, P < 0.001) compared to wild type (1.7%). This increase in LOH was associated with significantly increased NHEJ/SCR (46.1%, P < 0.001) and significantly reduced GC (3.3%, P < 0.001) compared to wild type, while Ch16 loss (18.6%) was similar to both single mutant and wild-type backgrounds (Figure 1C: Table 1). These findings indicate that Rqh1 suppresses LOH in a rad55Δ background. No loss of viability was observed in these strains following DSB induction (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1.

Suppression of LOH by chromosome healing in HR mutant backgrounds

| Ch16-MGH in genetic background (strain No.) | % ade+ G418S/ HygS his+ (GC) | % ade+G418R/ HygR his+ (NHEJ/SCR) | % ade− G418S/HygS his− (Ch16 loss) | % ade+ G418S/ HygS his− (LOH) | % ade+ G418S/ HygS his− (dnTA) | P-value (LOH relative to wild type) | P-value (LOH relative to rad55Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type* | 49.7 ± 2.6 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 2.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.0% (0/22) | 1.000 | |

| rad55Δ* | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 62.8 ± 9.8 | 30.5 ± 10.9 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.4%(16/20) | 0.936 | |

| rqh1Δ | 22.8 ± 1.4 | 53.3 ± 0.4 | 18.6 ± 2.7 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.3% (4/20) | 0.615 | |

| rad55Δ rqh1Δ | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 46.1 ± 1.3 | 18.6 ± 1.6 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 24.7% (19/21) | 3.3 E–06 | 4.8 E–05 |

| rad57Δ | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 73.1 ± 6.0 | 21.4 ± 5.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.9% (10/20) | 0.955 | |

| rad57Δ rqh1Δ | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 76.8 ± 2.1 | 13.5 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 0.17 | 3.9% (10/20) | 9.75E–06 | |

| rad55Δ rqh1-K547A | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 46.7 ± 7.0 | 22.9 ± 7.6 | 22.5 ± 5.0 | 20.3% (18/20) | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| rad55Δ rqh1(ΔN1–322) | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 68.6 ± 3.3 | 17.4 ± 1.8 | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 6.0% (10/20) | 0.008 | 3.6 E–04 |

| Wild type (25°C) | 28.5 ± 1.3 | 50.9 ± 1.6 | 10.2 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.0% (0/6) | 0.567 | |

| rad55Δ (25°C) | 6.6 ± 3.7 | 47.4 ± 11.2 | 43.9 ± 11.3 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.5% (15/20) | 0.867 (WT@25°C) | |

| pfh1cs(25°C) | 16.5 ± 1.7 | 63 ± 10.5 | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.1% (1/9) | 0.609 (WT@25°C) | |

| rad55Δ pfh1cs(25°C) | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 72.7 ± 4.2 | 20.0 ± 2.6 | 6.4 ± 1.3 | 4.2% (13/20) | 0.013 (WT@25°C) | 0.027 (@25°C) |

| srs2Δ | 26.1 ± 2.7 | 49.9 ± 3.6 | 12.2 ± 2.5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.0% (0/18) | 0.006 | |

| rad55Δ srs2Δ | 7.2 ± 1.3 | 43.0 ± 9.8 | 36.4 ± 12.1 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.7% (16/20) | 0.402 | 0.654 |

| exo1Δ* | 52.7 ± 1.0 | 33.1 ± 0.7 | 13.0 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.5% (10/22) | 0.233 | |

| rqh1Δ exo1Δ | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 54.3 ± 5.8 | 14.4 ± 6.6 | 20.7 ± 5.1 | 12.4% (12/20) | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| rqh1Δ rad55Δ exo1Δ | 7.5 ± 5.5 | 58.7 ± 13.5 | 28.1 ± 18.3 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.0% (0/20) | 0.209 | 0.317 |

| rad51Δ* | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 35.9 ± 2.9 | 57.0 ± 2.9 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.6% (20/25) | 0.058 | |

| rqh1Δ rad51Δ | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 76.8 ± 3.4 | 19.5 ± 3.3 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.3% (15/20) | 0.007 | 0.09 |

The mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments with three individual strains are shown. % dnTA was calculated by multiplying the fraction of dnTA positive colonies identified from the 20 ade+ G418S/HygS colonies examined (indicated in brackets) by the % LOH. * denotes values as previously described (Cullen et al., 2007), shown here for comparison.

Rqh1 suppresses de novo telomere addition in a rad55Δ background

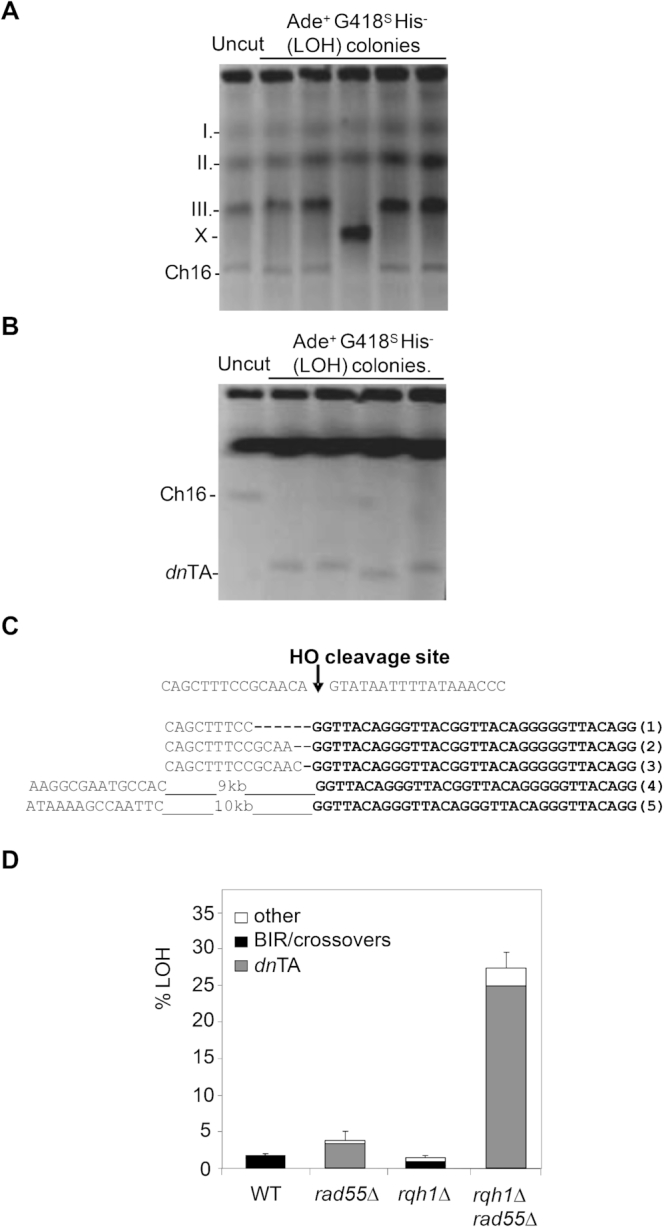

To identify the mechanism of break-induced LOH, the chromosomes of 21 LOH colonies from an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background were examined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). While endogenous chromosomes I and II derived from these LOH colonies remained unchanged, crossovers were sometimes observed (9.5% of LOH colonies) between ChIII and the homologous minichromosome, Ch16 (Figure 2A, lane 4). Importantly, minichromosomes from the remaining 90.5% of the LOH colonies appeared truncated, as determined by high-resolution separation of chromosomal DNA by PFGE (Figure 2B). As break-induced LOH retained the ade6 marker ∼25kb centromere proximal to the break site (Figure 1A), this raised the possibility that Ch16 truncations resulted from dnTA, as was previously observed in a rad55Δ background (41). This possibility was examined by colony PCR amplification using primers annealing to rad21+ (centromere proximal to the MATa break site) and a telomere specific primer. A PCR product of 300 bp following digestion with MfeI (a restriction site just upstream of the MATa site) was scored positive for dnTA. Sequence analysis of the PCR products indicated the presence of ∼300 bp of G2–5TTACA0–1 repeats, consistent with dnTA at, or very close to, the break site in 13 of the LOH colonies tested (Figure 2C). In 6 of the remaining colonies, telomeres were added ∼9–19 kb centromere proximal to the break site. In full, 24.7% of colonies underwent dnTA in rqh1Δ rad55Δ strains, which equated to a 1450-fold increase in dnTA compared to wild type (0.017%) (Figure 2D, Table 1).

Figure 2.

De novo telomere addition causes LOH in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. (A) Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) of LOH colonies obtained after HO induction in the rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. (B) High resolution PFGE of LOH colonies. (C) The sequence of the HO endonuclease cleavage site within MATa is shown, together with representative genomic DNA sequence data of the region surrounding the MATa site from five individually isolated ade+ G418S LOH colonies with truncated minichromosomes, indicating the presence of de novo telomeres. (D) Graph depicting mechanisms of LOH in wild type (WT, TH1900), rqh1Δ, rad55Δ and rqh1Δ rad55Δ backgrounds following DSB induction in Ch16-MGH. Data are derived from Table 1.

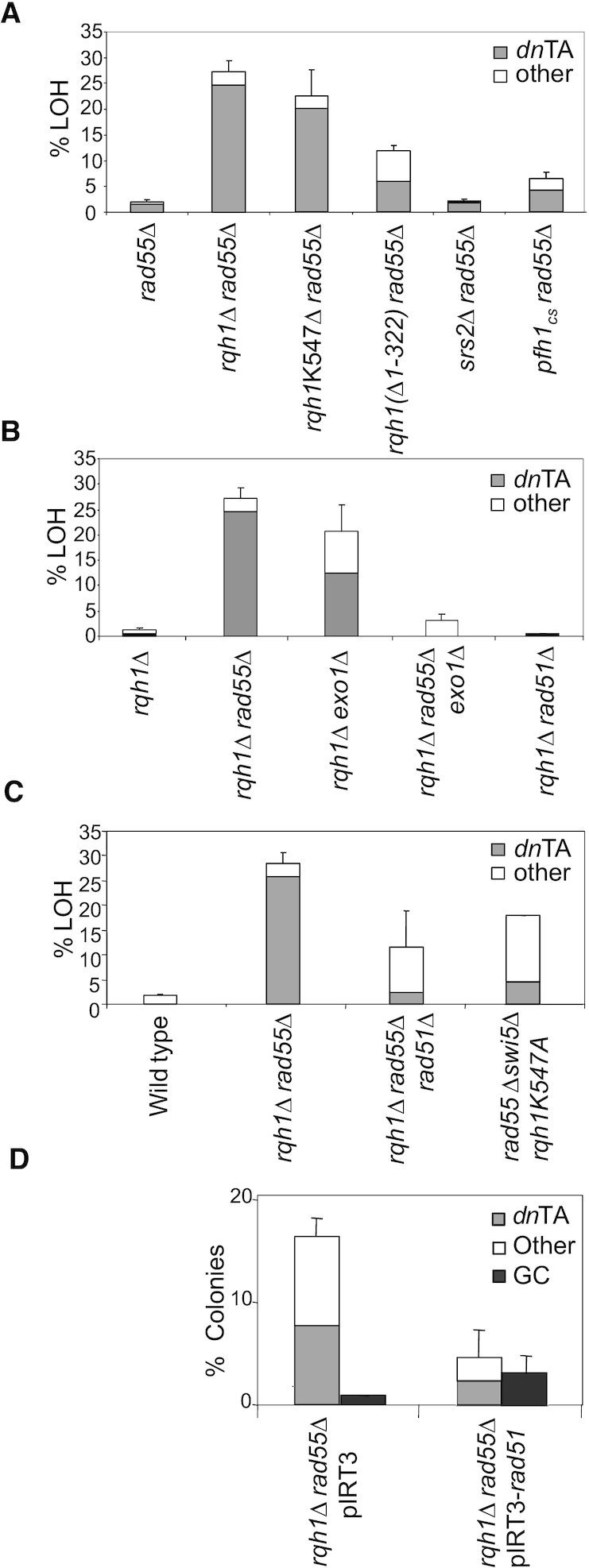

Suppression of de novo telomere addition requires Rqh1 helicase activity

To determine whether Rqh1 required its helicase activity to suppress dnTA, we introduced a helicase-dead mutation rqh1-K547A (19,51) into a rad55Δ background. In this strain, levels of break-induced LOH and dnTA resembled those observed in the rqh1Δ rad55Δ strain (Figure 3A, Table 1) suggesting Rqh1 helicase activity is required to suppress dnTA in a rad55Δ background.

Figure 3.

Suppression of LOH by de novo telomere addition in rad55Δ and rqh1Δ mutant backgrounds. (A) Mechanisms of LOH observed when rad55+ is deleted in various DNA helicase mutant backgrounds (Table 1). (B) Mechanisms of LOH observed when rqh1+ is deleted in various HR mutant backgrounds (Table 1, Supplementary Table SI). (C) Effect of abrogation of Rad51 loading on dnTA and LOH in an rqh1Δ background. (D) Graph depicting analysis of dnTA and GC levels following over-expression of either an empty vector (pIRT3) or Rad51 (pIRT3-rad51) in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background (Table 2).

Rqh1 has been shown to function in a complex with Top3 (19,20,52). As the top3Δ strain is non-viable (19,52), we tested the requirement of the Top3 interaction in suppressing dnTA using an rqh1ΔN1–322 mutant which has lost the Top3 binding domain (20) and is expressed at similar levels to the wild-type Rqh1 (20). DSB-induced LOH in the rad55Δrqh1ΔN1–322 mutant was significantly higher (11.9%, P<0.001) than that observed in rad55Δ (1.8%), but less than the rqh1Δ rad55Δ strain (27.3%; Figure 3A; Table 1). This effect could be attributed to a requirement for Rqh1-Top3 interaction in suppressing break-induced LOH in a rad55Δ background or to partial loss of Rqh1 helicase activity in the rqh1ΔN1–322 mutant.

To determine whether other helicases could function similarly to Rqh1, we introduced a deletion of srs2+ or a cold-sensitive allele of pfh1+, pfh1-R20 (pfh1cs) (45) into a rad55Δ background and examined levels of dnTA. Srs2 is implicated in regulation of HR where it antagonizes the activity of the Rad55–Rad57 heterodimer (53–55). In contrast to the rqh1Δ mutant, the srs2Δ mutant failed to significantly increase levels of break-induced LOH in a rad55Δ background (Figure 3A; Table 1). The S. cerevisiae Pfh1 homologue, Pif1 has been identified as a suppressor of dnTA and gross chromosomal rearrangements (56,57). The rad55Δ pfh1cs strain showed a modest yet significant increase in LOH (6.4%) compared to wild-type background at semi-permissive temperature (0.8%, P = 0.013), and a significant increase in comparison to rad55Δ LOH levels (P = 0.027), at semi-permissive temperature (Figure 3A; Table 1). Therefore, Pfh1 can suppress LOH arising predominantly from dnTA, in accordance with the described role in S. cerevisiae. However, in our assay, Rqh1 helicase clearly plays a more prominent role in suppressing dnTA than Srs2 or Pfh1.

Rqh1 functions with early acting HR proteins to suppress dnTA

Next we wished to examine the potential role of other HR factors in suppressing dnTA in an rqh1Δ background. As Exo1 functions early in HR during DSB resection, we examined the relationship between Rqh1 and Exo1 (5,6,58). Deletion of exo1+ did not significantly alter levels of break-induced LOH compared to wild type (41). However, a striking increase in levels of break-induced LOH (20.7%) was observed in an rqh1Δ exo1Δ double mutant, 60% (12 of 20 examined colonies) of which was due to dnTA (Figure 3B, Table 1). Break-induced marker loss after deletion of exo1+ in an rqh1Δ or rqh1Δrad55Δ background was also determined (Table 1). Break-induced LOH was significantly reduced in the rqh1Δ rad55Δ exo1Δ mutant compared to the rqh1Δ rad55Δ mutant (P<0.001) and no dnTA products were obtained upon further analysis (Table 1). This requirement for exo1+ in facilitating dnTA in the rqh1Δ rad55Δ background is in accordance with Exo1-dependent end-resection facilitating dnTA, as previously proposed (41). We were unable to test the role of Rad52 in suppressing dnTA as the rqh1Δrad52Δ strain was extremely sick, consistent with previously reported findings (19).

As Rad57 forms a heterodimer with Rad55 (59), we examined gene marker loss in a rad57Δ background. The resultant marker loss profile was similar to that of rad55Δ strains (Table 1). Following DSB induction in an rqh1Δ rad57Δ background, 7.7% of colonies exhibited extensive LOH (P = 0.011 compared to a rad57Δ single mutant), out of which 50% of the double mutant had undergone dnTA (Table 1). Thus, Rqh1 can suppress LOH in a rad57Δ background, albeit not to the same extent as in a rad55Δ background.

DSB induction within Ch16 in a rad51Δ background has previously been shown to result in a higher proportion of minichromosome loss, demonstrating a failure to repair the DSB (41,42). DSB induction in a rqh1Δ rad51Δ background resulted in reduced levels (0.39%) of LOH colonies compared to wild type (1.7%; P = 0.007) and rqh1Δ (1.5%; P = 0.051), indicating that, in contrast to a rad55Δ background, Rqh1 does not suppress break-induced LOH significantly in a rad51Δ background (Figure 3B; Table 1). Instead, a significant increase in NHEJ/SCR (76.8%) was observed in an rqh1Δ rad51Δ background compared to that of rad51Δ (35.9%, (41)), indicating that DSBs in an rqh1Δ rad51Δ double mutant are still competent for HR-independent repair, even though HR is severely impaired. These observations are consistent with an early role for Rqh1 in HR, as described for Sgs1 and BLM in budding yeast and human cells, respectively (4–6,58).

We have previously shown that LOH is significantly reduced in mus81Δ (0.2%) compared to rad55Δ strain (1.8%, P = 0.014) (41). In a mus81Δ rad55Δ strain, Ch16 loss dramatically increased (60.5%) compared the mus81Δ (38.1%) or rad55Δ (30.5%) single mutants (41). As expected, GC is dramatically reduced in mus81Δ rad55Δ (5.1%) compared to mus81Δ (29.0%) as Rad55 acts upstream of Mus81 in HR. Consistent with the late role of Mus81 in HR, SCR in mus81Δ rad55Δ (23.4%) is similar to mus81Δ (28.1%) in comparison to rad55Δ (62.8%) (41). Although LOH was not measured in mus81Δ rad55Δ, the high levels of Ch16 loss in mus81Δ rad55Δ and the low levels of LOH in mus81Δ suggest that Mus81 does not suppress dnTA in an rhp55Δ background.

A critical role for Rad51 loading in facilitating efficient dnTA

Following DSB induction, dnTA may occur before or after Rad51-dependent strand invasion. If dnTA resulted immediately following resection, then this event should be Rad51-independent. In an rqh1Δ rad55Δ rad51Δ triple mutant, increased levels of LOH (11.7%) were observed, although only 21.1% of these resulted from dnTA (Figure 3C; Table 2). Thus, dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ rad51Δ background was reduced almost ten-fold from 24.7% to 2.5% compared to the rqh1Δ rad55Δ background (Tables 1 and 2). Thus Rad51 contributes to dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background.

Table 2.

Rad51 loading promotes de novo telomere addition in rqh1D rad55D

| Ch16-MGH in genetic background | % ade+ G418S/HygS his+ (GC) | % ade+ G418R/Hyg R his+ (NHEJ/SCR) | % ade− G418S/HygS his− (Ch16 loss) | % ade+ G418S/HygS his− (LOH) | % ade+ G418S/HygS his− (dnTA) | P value (LOH relative to wildtype) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 49.7 ± 2.6 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 2.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.0% (0/20) | 1.000 |

| rqh1Δ rad55Δ rad51Δ | 0.1 ± 0.06 | 67.0 ± 12.7 | 21.0 ± 6.3 | 11.7 ± 7.2 | 2.5% (4/20) | 0.161 |

| swi5Δ | 21.9 ± 2.6 | 57.2 ± 3.2 | 20.5 ± 2.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.3% (7/20) | 0.023 |

| rad55Δ swi5Δ | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 30.2 ± 0.5 | 65.9 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 1.9% (10/20) | 0.435 |

| rqh1K547A swi5Δ | 15.4 ± 3.3 | 60.5 ± 2.4 | 13.2 ± 4.8 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 2.3% (8/20) | 0.028 |

| rqh1K547A rad55Δ swi5Δ | 0.15 ± 0.15 | 36.9 ± 1.5 | 44.9 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.01 | 4.5% (5/20) | 3.28E–07 |

| rad55Δ rqh1Δ+ pIRT3 | 0.7 ± 0.07 | 68.4 ± 3.1 | 14.4 ± 2.6 | 16.4 ± 1.5 | 9.8% (12/20) | 1.27E–05 |

| rad55Δ rqh1Δ+ pIRT3-rad51 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 88.3 ± 5.9 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 2.3% (10/20) | 0.005 |

The mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments with three individual strains are shown. % dnTA was calculated by multiplying the fraction of dnTA positive colonies identified from the 20 ade+ G418S/HygS colonies examined (indicated in brackets) by the % LOH. The P-value for rad55∆ rqh1∆+ pIRT3-rad51 is 0.042 relative to rad55∆ rqh1∆+ pIRT3. Wt values presented as previously described (Cullen et al., 2007)

The Swi5/Sfr1 heterodimer functions in parallel to the Rad55/Rad57 heterodimer to load Rad51. DSB induction in a swi5Δ background resulted in significantly increased levels of NHEJ/SCR colonies (57%, P < 0.001) compared to wild type (25%), resembling levels observed in a rad55Δ background (63%). GC (22% P < 0.001) was significantly reduced in a swi5Δ background compared to wild type (50%), but levels of Ch16 loss (20.5%) and LOH (0.8%) were similar to wild type (Table 2).

We also tested the rad55Δ swi5Δ double mutant. Marker loss in a rad55Δ swi5Δ strain was very similar to that in a rad51Δ strain, resulting in high levels of Ch16 loss (66%), consistent with failed Rad51 loading. Levels of NHEJ/SCR colonies were also reduced in the rad55Δ swi5Δ background (30%) compared to rad55Δ (62%) or swi5Δ (57%) single mutants, consistent with this population arising through HR-dependent SCR. Further, levels of LOH through dnTA (1.9%) in rad55Δ swi5Δ strain were equivalent to that of rad55Δ strain alone (1.4%: P = 0.743: Table 2).

Introducing a helicase-dead rqh1 mutant into a rad55Δ swi5Δ background (rad55Δ swi5Δ rqh1-K547A) resulted in a striking increase in break-induced LOH (17.9%, P<0.001) compared to wild type. However, further analysis indicated that only 25% of these were a result of dnTA (4.5%; Figure 3C; Table 2). Interestingly, dnTA levels were reduced 4.5-fold in rqh1-K547A rad55Δ swi5Δ background compared to an rqh1-K547A rad55Δ background (20.5%; Table 1). Therefore efficient dnTA in rad55Δ strains in the absence of Rqh1 helicase activity requires Swi5 or Rad51, thus further indicating a role for Rad51-loading being required for efficient dnTA.

We have previously demonstrated that Rad51 overexpression (OPrad51) reduced levels of dnTA in a rad55Δ background (41), consistent with competition between the Rad51 recombinase and telomerase for resected ends. We therefore tested whether Rad51 overexpression could similarly reduce levels of dnTA observed in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background by introducing pIRT3-rad51 (60). OPrad51 resulted in significantly increased levels of GC (3.3%, P = 0.05), and SCR (88.3%, P = 0.03), and significantly reduced levels of Ch16 loss (3.9%, P = 0.04) and LOH (4.45%, P = 0.04), and therefore reduced levels of dnTA, in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background compared to vector alone (Figure 3D; Table 2). However, whilst rad55Δ, rqh1Δ and rad55Δ rqh1Δ are exquisitely sensitive to radiation in a rad51Δ background (Supplementary Figure S2), overexpression of Rad51 does not significantly rescue radiation sensitivity in these mutants (Supplementary Figure S3). Together, these data identify a critical role for Rad51 recombinase levels in facilitating dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background.

The MRN complex promotes SCR and partially suppresses dnTA in a rad55Δ background

We wished to examine whether deletion of other early acting HR genes could suppress dnTA in a rad55Δ background. We previously reported that deleting exo1+ in a rad55Δ background resulted in reduced levels of dnTA compared to rad55Δ strains (41). Here we further tested the effect of deleting the MRN complex in a rad55Δ background. Deletion of mre11+, rad50+ or nbs1+ in a rad55Δ background resulted in a striking reduction in levels of NHEJ/SCR colonies and increased levels of Ch16 loss compared to rad55Δ (Table 3). These results resemble those of another HR mutant, rad55Δ rad51Δ (42), and are consistent with the break-induced ade+ G418R his+ population in a rad55Δ background resulting from HR-dependent SCR following break-induction. Levels of LOH colonies arising through dnTA were modestly increased in rad55Δ mre11Δ (4.8%), rad55Δ rad50Δ (4.5%), and rad55Δ nbs1Δ (2.4%) compared to rad55Δ (1.4%) or the respective individual MRN deletion mutants (Table 3). Thus, while the MRN complex is important for SCR, it performs only a minor role in suppressing dnTA in a rad55Δ background compared to Rqh1. Thus, Rqh1 plays a functionally distinct role from Exo1 and the MRN complex in suppressing dnTA in rad55Δ strains.

Table 3.

DSB-induced marker loss and dnTA in rad55Δ and MRN deletion mutants

| Ch16-MGH in genetic background | % ade+ G418S/HygS his+ (GC) | % ade+ G418R/Hyg R his+ (NHEJ/SCR) | % ade− G418S/HygS his− (Ch16 loss) | % ade+ G418S/HygS his− (LOH) | % ade+ G418S/HygS his− (dnTA) | P value (LOH relative to wildtype) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 49.7 ± 2.6 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 2.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.0% (0/20) | 1.000 |

| rad55Δ* | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 62.8 ± 9.8 | 30.5 ± 10.9 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.4% (16/20) | 0.936 |

| mre11Δ* | 30.7 ± 2.0 | 25.6 ± 5.1 | 35.7 ± 5.8 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.3% (11/21) | 0.013 |

| mre11Δ rad55Δ | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 20.1 ± 0.2 | 61.7 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 4.8% (16/22) | <0.05 |

| rad50Δ* | 18.3 ± 1.8 | 23.9 ± 0.6 | 49.7 ± 1.9 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2% (6/20) | 0.011 |

| rad50Δ rad55Δ | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 29.2 ± 6.3 | 53.9 ± 5.4 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 4.5% (21/23) | 0.088 |

| nbs1Δ * | 15.6 ± 0.7 | 30.9 ± 2.6 | 43.6 ± 3.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7% (17/21) | 0.441 |

| nbs1Δ rad55Δ | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 23.4 ± 1.9 | 61.9 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.4% (20/22) | 0.163 |

The mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments with three individual strains are shown. % dnTA was calculated by multiplying the fraction of dnTA positive colonies identified from the 20 ade+ G418S/HygS colonies examined (indicated in brackets) by the % LOH. * denotes values as previously described, shown here for comparison (Cullen et al., 2007)

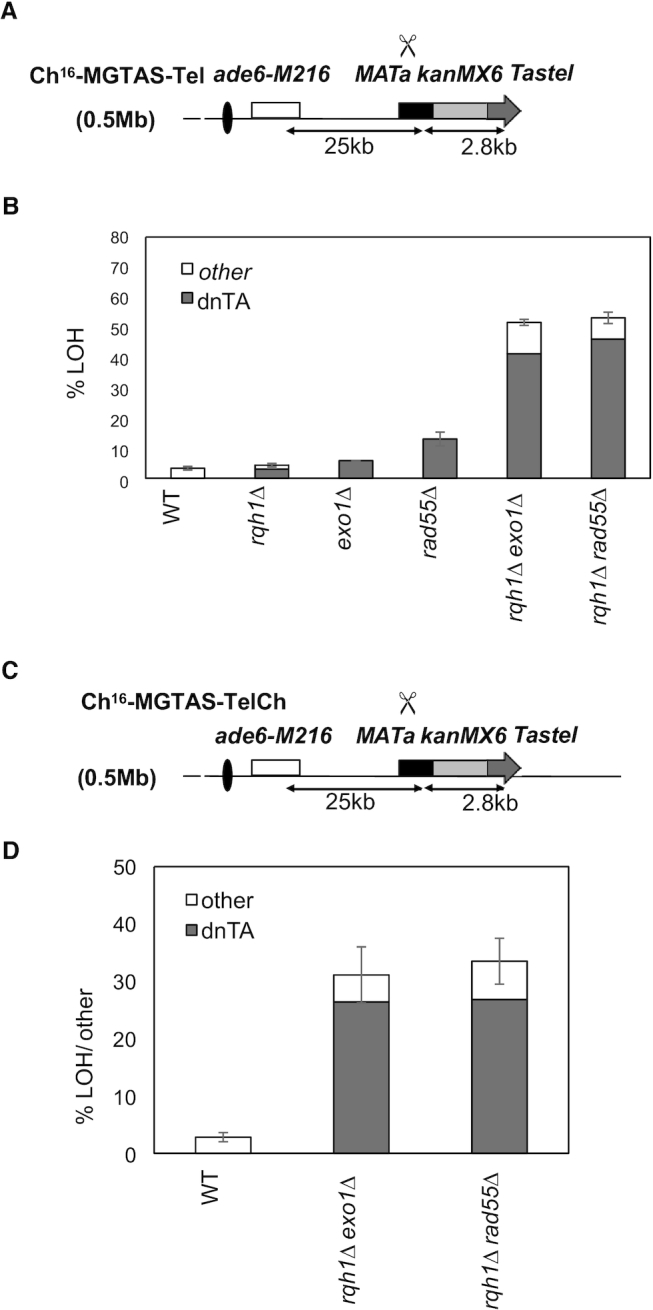

Striking levels of dnTA at a DSB lacking a homologous distal chromosome arm

The above findings indicate that efficient dnTA is associated with HR intermediates. To test this further, we asked whether dnTA would be further increased under circumstances in which post-synaptic second-end capture was abrogated. To address this, the (130 kb) homologous arm centromere-distal to the break site was replaced by a construct containing the 1.8 kb MATa target sequence/G418-resistant marker and a 1 kb synthetic telomere, TASTel fragment containing 700 bp of subtelomeric DNA (TAS) and 300 bp of telomeric DNA (Tel) (Figure 4A) (61), in which there is no distal homologous chromosome arm (Ch16-MGTASTel). Following break-induction, DSB repair by NHEJ/SSC in Ch16-MGTASTel results in cells that retain the ade+ G418R phenotype. Cells that fail to repair the DSB lose the minichromosome and become ade− G418S, while those which undergo LOH become ade+ G418S. Following DSB induction in Ch16-MGTASTel cells, homology search, strand invasion and DNA synthesis steps should still be possible for the broken centromere-proximal arm, while the later HR stages of second-end capture or strand annealing are obviated. In contrast to DSB induction in the Ch16-MGH strain, it is not possible for Ch16-MGTASTel cells to undergo GC and become ade+ G418S since GC requires the participation of two homologous DSB arms (62).

Figure 4.

Efficient dnTA occurs at a DSB lacking a homologous distal chromosome arm. (A) Schematic of the Ch16-MGTASTel minichromosome. ChIII as described in Figure 1B. The loci of the centromeres (black oval), ade6-M216 and ade6-M210 alleles (white boxes), MATa target site (black box), KanMX6 gene (gray), and TASTel sequence (grey arrow) as indicated. pREP81X-HO generates a DSB at the MATa target site (scissors). (B) Histogram of percentage break-induced LOH arising through dnTA (grey) or other (white) in wild type (WT, TH2039), rqh1Δ (TH2254), exo1Δ (TH2420), rad55Δ (TH2253), rqh1Δ exo1Δ (TH8226) and rqh1Δ rad55Δ (TH2266) strains following HO-endonuclease induction for 48h (Table 1). (C) Schematic of the Ch16-MGTASTelCh minichromosome. Minichromosome whose features are described in (A); ChIII as described in Figure 1B. (D) Histogram of percentage break-induced LOH arising through dnTA (gray) or other (white) in wild-type (TH8597), rqh1Δ exo1Δ double mutant (TH8598) and rqh1Δ rad55Δ double mutant (TH8708) strains following HO-endonuclease induction for 48 h (Table 5).

We found DSB induction in Ch16-MGTASTel in a wild-type background resulted in 79.3% of the colonies becoming ade− G418S, consistent with very high levels of unrepaired breaks leading to chromosome loss or other undetectable rearrangements; 17.4% remained ade+ G418R, consistent with NHEJ or SCR; and 3.3% became ade+ G418S, having undergone LOH (Table 4). Further PCR analysis of 20 individually isolated ade+ G418S colonies failed to detect dnTA (Figure 4B; Table 4). Deletion of rqh1+, exo1+ or rad55+ each resulted in increased levels of NHEJ/SCR and reduced Ch16 loss, as was observed in Ch16-MGH. This was associated with modest increases in LOH and dnTA with 13% dnTA noted in a rad55Δ background (Figure 4B; Table 4). Remarkably, DSB induction in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background resulted in 53% of the colonies becoming ade+ G418S, corresponding to 45.2% dnTA (Figure 4B; Table 4). Similarly, following DSB induction in an rqh1Δ exo1Δ background, 51% of the colonies became ade+ G418S which corresponded to 41.4% dnTA.

Table 4.

DSB-induced marker loss and dnTA in minichromosome

| Ch16-MGTASTel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch16-MGTASTel genetic background (strain number) | % ade+ G418R (NHEJ/ SCR/ uncut) | % ade− G418S (Ch16/loss/ other) | % ade+ G418S (LOH) | % ade+ G418S (dnTA) | P-value (LOH relative to wild type) |

| Wild type | 17.4 ± 4.0 | 79.3 ± 4.17 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 0.0% (0/20) | 1.000 |

| rqh1Δ | 50.8 ± 0.4 | 44.8 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 3.0% (14/20) | <0.005 |

| exo1Δ | 51.0 ± 0.8 | 43.2 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 5.8% (20/20) | <0.005 |

| rad55Δ | 47.2 ± 3.9 | 39.7 ± 1.8 | 13.0 ± 2.3 | 13% (20/20) | <0.005 |

| rqh1Δ exo1Δ | 23.3 ± 2.9 | 25.0 ± 4.5 | 51.7 ± 1 | 41.4% (16/20) | <0.005 |

| rqh1Δ rad55Δ | 31.3 ± 0.8 | 15.5 ± 1.1 | 53.2 ± 1.9 | 45.2% (17/20) | <0.005 |

The mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments with three individual strains are shown. % dnTA was calculated by multiplying the fraction of dnTA positive colonies identified from the 20 ade+ G418S colonies examined (indicated in brackets) by the % LOH.

To test whether the increased levels of dnTA resulted from loss of the second homologous chromosome arm, or from proximity to the TASTel synthetic telomere sequence, an additional minichromosome was constructed in which the TASTel sequence was integrated distal to the MATa site of Ch16-MG, (in the same locus as Ch16-MGH), but retaining the distal arm of the minichromosome, to form Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, DSB induction in a wild-type strain containing Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch resulted in 76% Ch16 loss or extensive LOH; while 2% of the colonies underwent LOH or GC, and dnTA was not detected (Table 5). Although we cannot distinguish LOH or GC colonies, the levels of ade+ G418S colonies (combining LOH and GC) in Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch were much less than ade+ G418S his− (GC) in Ch16-MGH cells. The reduced GC observed in Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch strain presumably reflects the reduced homology with ChIII due to the addition of the non-homologous TASTel cassette. Following DSB induction in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background, 33% of colonies were ade+ G418S, corresponding to 27% dnTA (Figure 4D; Table 5). This was again significantly reduced compared to 45.2% dnTA (P = 0.0142) observed using Ch16-MGTASTel, but was very similar to levels observed using Ch16-MGH (25%). Following DSB induction within an rqh1Δ exo1Δ background, in which GC was abrogated, 31% of the colonies were ade+ G418S, corresponding to 26% dnTA (Figure 4D; Table 5). This was significantly reduced compared to that observed using Ch16-MGTASTel (41.4% P = 0.04), but was greater than levels observed using Ch16-MGH (12% P>0.05). Thus, dnTA was significantly further increased in the context of a ‘one-armed’ break in either rqh1Δ rad55Δ or rqh1Δ exo1Δ backgrounds. While in the rqh1Δ exo1Δ background, proximity of the DSB site to telomeric sequence could contribute to high dnTA levels, the striking dnTA levels observed in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background are consistent with disrupting post-synaptic HR events.

Table 5.

Marker loss and dnTA in minichromosome Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch

| Ch16-MG(TASTel)Ch genetic background (strain number) | % ade+ G418R (NHEJ/ SCR/ uncut) | % ade− G418S (LOH/ Ch16 loss) | % ade+ G418S (LOH/GC) | % ade+ G418S (dnTA) | P-value (LOH relative to wild type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 21.2 ± 5.6 | 76± 6.0 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 0.0% (0/20) | 1.000 |

| rqh1Δ exoΔ | 28.3 ± 5.6 | 40.6 ± 3.6 | 31.1 ± 4.9 | 26.4% (17/20) | 0.0072 |

| rqh1Δ rad55Δ | 25.5 ± 1.0 | 41.0 ± 2.5 | 33.5± 4.0 | 26.8% (16/20) | 0.0058 |

The mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments with three individual strains are shown. % dnTA was calculated by multiplying the fraction of dnTA positive colonies identified from the 20 ade+ G418S colonies examined (indicated in brackets) by the % LOH.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe roles for the BLM homologue, Rqh1 helicase and the Rad51 paralog, Rad55, in both facilitating homologous recombination and in suppressing chromosome healing at a break site in fission yeast. We find Rqh1 helicase, together with either Rad55 or Exo1 suppresses dnTA. Further, we find that a DSB lacking a homologous distal chromosome arm undergoes highly efficient dnTA in these genetic backgrounds. Together these findings indicate that chromosome healing can occur highly efficiently within HR intermediates. Here we consider the mechanisms by which these events occur in the absence of these genes and the implications for genome stability.

Suppressing chromosome healing

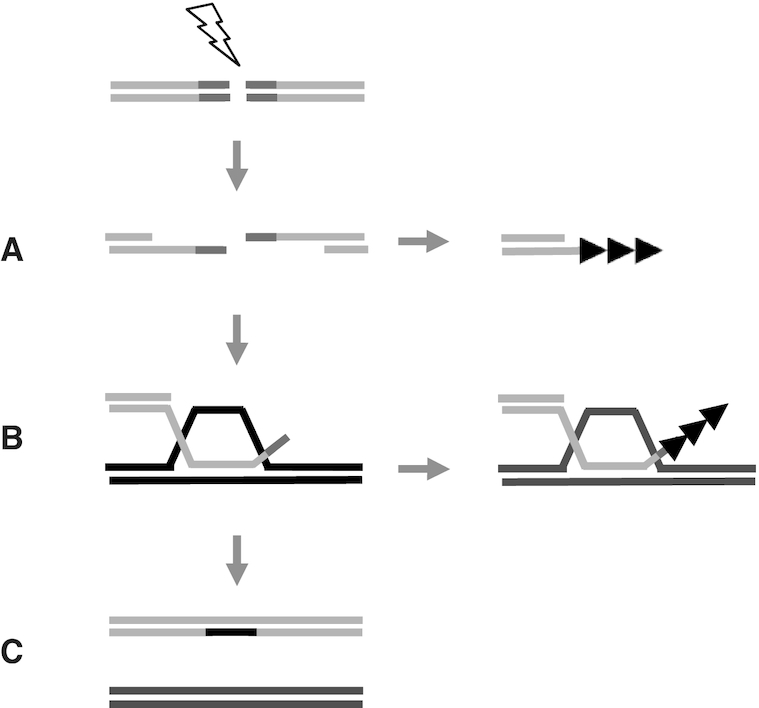

Our study identifies an independent role for the HR proteins Rqh1, together with Rad55 or Exo1 in suppressing dnTA, with a striking increase in dnTA being observed in rqh1Δ rad55Δ and to a lesser extent rqh1Δ exo1Δ backgrounds, compared to wild type. As extensive resection requires both Rqh1 and Exo1 (4–6), these findings are consistent with partially resected ends acting as efficient substrates for dnTA (37,38). Loss of both Rad55 and Rqh1 may also facilitate presynaptic dnTA either through reduced resection or through altering the structure of the Rad51 nucleofilament so that it is more conducive to dnTA (Figure 5) (63–65). That overexpression of Rad51 in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background led to significantly reduced levels of dnTA and significantly elevated levels of both GC and SCR suggests that Rad55 suppresses dnTA through facilitating efficient Rad51 assembly. These findings are broadly consistent with a role for HR in preventing dnTA through competition for resected ends (41).

Figure 5.

Model for efficient dnTA within HR intermediates. (A) Presynaptic break-induced dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. Following DSB induction at the MATa site (dark grey) within the minichromosome (light grey) reduced resection, shortened and or an altered Rad51 nucleofilament structure facilitates presynaptic dnTA (black arrows). (B) Postsynaptic break-induced dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. Following DSB induction Rad51-dependent strand invasion of ChIII (black) leads to D-loop formation, which is stabilized in the absence of both Rqh1, and Rad55. Non-homologous MATa 3′ ends remain unprocessed and are extruded from the D-loop, facilitating dnTA. Removal of the second homologous arm significantly further increases dnTA in this context suggesting that second end capture or strand annealing efficiently suppresses dnTA. (C) Over-expression of Rad51 in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background increases gene conversion. Thus Rad51 loading and subsequent nucleofilament structure plays a critical role in defining the fate of broken chromosome ends. Pathways A and B may be non-exclusive. See text for details.

However, RecQ helicase activity is also required for branch migration, to displace non-allelic recombination, and to prevent the formation of double-Holliday junctions (15), and loss of these post-synaptic functions may also facilitate dnTA. Here, loss of Rqh1 helicase activity may lead to stabilization of the invading strand in a D-loop, which may facilitate dnTA (Figure 5). Consistent with this, dnTA was occasionally associated with crossover events between Ch16 and ChIII in rqh1Δ rad55Δ (Figure 3A). Loss of Rad55 may also contribute to post-synaptic dnTA by promoting Srs2-dependent exclusion of the non-homologous MATa site from the D-loop, which may now act as a landing pad for telomerase. Accordingly, postsynaptic roles have also been assigned to the Rad51 paralogues, which are the human counterparts to Rad55 and Rad57 (66,67). In this respect, the Rad51L3–XRCC2 complex physically interacts with and stimulates BLM to disrupt Holliday junctions in vitro (67). The observation that a DSB lacking a homologous distal chromosome arm significantly further increased dnTA levels in rqh1Δ rad55Δ or rqh1Δ exo1Δ backgrounds is consistent with a model in which the post-synaptic HR events of second end capture or strand annealing compete with dnTA (Figure 5).

Determinants of chromosome healing

We found Rad51 to be required for efficient dnTA. This was unexpected as efficient Rad51 loading suppresses dnTA. Accordingly, dnTA levels were significantly reduced in a rad51Δ rqh1Δ rad55Δ strain compared to an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. Similarly, preventing Rad51 loading by simultaneously disrupting both Rad55–Rad57 and Swi5–Sfr1 heterodimers significantly reduced dnTA in swi5Δ rad55Δ rqh1-K547A compared to a rad55Δ rqh1-K547A background. Taken together, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that Rad55–Rad57 and Swi5–Sfr1 have distinct roles in Rad51 assembly (68). It has been shown that Rad51-foci form less efficiently in Swi5–Sfr1 compared to a Rad55–Rad57 mutant (11) whereas Rad55–Rad57 subtly organizes the Rad51-nucleofilament structure (55). Therefore, Swi5–Srf1 is required to stabilize Rad51, thus promoting dnTA, whereas Rad55–Rad57 is required to modulate Rad51 structure, which promotes GC and suppresses dnTA.

As Rad51 over expression suppressed dnTA and promoted GC in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background, this suggests the Rad51 nucleofilament structure is likely to play a critical role in defining the fate of broken chromosome ends. Rad51 may potentially promote dnTA presynaptically in this respect, through assembling a nucleofilament structure to which telomerase may preferentially bind in the absence of Rad55 and Rqh1. Rad51 may also promote dnTA post-synaptically, through facilitating D-loop formation, which in the absence of Rqh1 or Rad55 facilitates dnTA at non-homologous ends extruded from the D-loop (Figure 5). As D-loops are structurally analogous to T-loops (69), our findings suggest a structural context through which T-loops may promote telomerase activity.

We found Exo1 to be required for dnTA in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. As efficient dnTA was observed in an rqh1Δ exo1Δ background this indicates that Exo1 is not required for telomere addition. However, in S. cerevisiae Sae2/MRX and Sgs1 activities are required to allow Exo1 access, which contributes to telomere end processing and elongation (70). We speculate that further loss of Exo1-dependent resection in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background fails to generate sufficient ssDNA necessary to facilitate dnTA. Such resection may facilitate Rad51 binding as indicated above. Reduced dnTA is associated with increased NHEJ/SCR following Exo1 deletion in an rqh1Δ rad55Δ background. However, further studies will be required to elucidate the precise role of Exo1 in this context.

Mechanisms of telomere addition

The finding that efficient dnTA was observed at or near the MATa site was unexpected, as this region lacks the canonical GGTTACA S. pombe telomeric repeat sequence (61). Studies in S. cerevisiae have shown dnTA was restricted to very short regions of homology to the telomerase guide RNA that were likely to facilitate annealing of such RNA (71,72). Thus, efficient dnTA observed in our study may result from recognition of degenerate telomeric sequences by guide RNA or other telomere recruitment factors. Alternatively, telomere recruitment may be achieved in a sequence-independent manner through interaction between ssDNA binding factors and telomerase (73).

Chromosome healing and genome instability

Our findings indicate that dnTA has the capacity to stabilize broken chromosomes. However, such a role comes at the price of potentially extensive loss of genetic material centromere-distal to the break site. While dnTA is predicted to result in loss of viability in a haploid setting, such extensive LOH in a diploid or polyploidy cells may be tolerated. Thus, dnTA may provide an important back-up mechanism to rescue broken chromosomes, thus facilitating cell survival.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to especially thank Elspeth Stewart and Stuart MacNeill for strains and reagents, Matthew Whitby for useful discussions and Alessandro Bianchi for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author contributions: Experiments in Figure 1 were performed by A.W. and A.D.; in Figure 2 by A.D., H.T.P. and C.W.; in Figure 3 by A.D.; in Figure 4 B.W. and C.C.P., with initial strain engineering from J.P.; with experiments presented in Table 1 by A.D. and S.D., Table 2 by A.D.; Table 3 by J.K.C.; Tables 4 and 5 by C.C.P.; Supporting Table 1 by S.D.; Supplementary Figure S1 by A.W.; Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 by S.D. and C.W. Supporting work was performed by L.H. and S.S. T.C.H., A.M.C. and J.M.M. supervised the work and T.C.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

MRC (UK) [MC_PC_12003]; EURISC-RAD project [FI6R-CT-2003-508842 to J.P., J.C., A.D., L.H., C.P., S.S., C.W., S.D., H.T.P., T.C.H.]; BBSRC [BB/C510291/1]; CRUK [C9601/A9484]; BBSRC [BB/K019805/1] to J.M.M.; ERC [268788-SMI-DDR to A.W., A.M.C.]; B.W. was funded by A*STAR, Singapore. Funding for open access charge: MRC Grant [H3R00391/H311].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Resnick M.A., Martin P.. The repair of double-strand breaks in the nuclear DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its genetic control. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1976; 143:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A.. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011; 144:646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lieber M.R. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010; 79:181–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gravel S., Chapman J.R., Magill C., Jackson S.P.. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:2767–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S.. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008; 455:770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu Z., Chung W.H., Shim E.Y., Lee S.E., Ira G.. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008; 134:981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S.. DNA end resection–unraveling the tail. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2011; 10:344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sugiyama T., New J.H., Kowalczykowski S.C.. DNA annealing by RAD52 protein is stimulated by specific interaction with the complex of replication protein A and single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998; 95:6049–6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang X., Haber J.E.. Role of Saccharomyces single-stranded DNA-binding protein RPA in the strand invasion step of double-strand break repair. PLoS Biol. 2004; 2:E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sung P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997; 272:28194–28197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akamatsu Y., Tsutsui Y., Morishita T., Siddique M.S., Kurokawa Y., Ikeguchi M., Yamao F., Arcangioli B., Iwasaki H.. Fission yeast Swi5/Sfr1 and Rhp55/Rhp57 differentially regulate Rhp51-dependent recombination outcomes. EMBO J. 2007; 26:1352–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haruta N., Kurokawa Y., Murayama Y., Akamatsu Y., Unzai S., Tsutsui Y., Iwasaki H.. The Swi5-Sfr1 complex stimulates Rhp51/Rad51- and Dmc1-mediated DNA strand exchange in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006; 13:823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sung P. Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 1997; 11:1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heyer W.D., Ehmsen K.T., Liu J.. Regulation of homologous recombination in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010; 44:113–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu L., Hickson I.D.. DNA helicases required for homologous recombination and repair of damaged replication forks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006; 40:279–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hickson I.D. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003; 3:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murray J.M., Lindsay H.D., Munday C.A., Carr A.M.. Role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ homolog, recombination, and checkpoint genes in UV damage tolerance. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997; 17:6868–6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stewart E., Chapman C.R., Al-Khodairy F., Carr A.M., Enoch T.. rqh1+, a fission yeast gene related to the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for reversible S phase arrest. EMBO J. 1997; 16:2682–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laursen L. V, Ampatzidou E., Andersen A.H., Murray J.M.. Role for the fission yeast RecQ helicase in DNA repair in G2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003; 23:3692–3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmad F., Stewart E.. The N-terminal region of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ helicase, Rqh1p, physically interacts with Topoisomerase III and is required for Rqh1p function. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2005; 273:102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caspari T., Murray J.M., Carr A.M.. Cdc2-cyclin B kinase activity links Crb2 and Rqh1-topoisomerase III. Genes Dev. 2002; 16:1195–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hope J.C., Maftahi M., Freyer G.A.. A postsynaptic role for Rhp55/57 that is responsible for cell death in Deltarqh1 mutants following replication arrest in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2005; 170:519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hope J.C., Cruzata L.D., Duvshani A., Mitsumoto J., Maftahi M., Freyer G.A.. Mus81-Eme1-dependent and -independent crossovers form in mitotic cells during double-strand break repair in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007; 27:3828–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cromie G.A., Hyppa R.W., Smith G.R.. The fission yeast BLM homolog Rqh1 promotes meiotic recombination. Genetics. 2008; 179:1157–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nanbu T., Takahashi K., Murray J.M., Hirata N., Ukimori S., Kanke M., Masukata H., Yukawa M., Tsuchiya E., Ueno M.. Fission yeast RecQ helicase Rqh1 is required for the maintenance of circular chromosomes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013; 33:1175–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doe C.L., Ahn J.S., Dixon J., Whitby M.C.. Mus81-Eme1 and Rqh1 involvement in processing stalled and collapsed replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277:32753–32759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coulon S., Gaillard P.H., Chahwan C., McDonald W.H., Yates J.R. 3rd, Russell P.. Slx1-Slx4 are subunits of a structure-specific endonuclease that maintains ribosomal DNA in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004; 15:71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Win T.Z., Mankouri H.W., Hickson I.D., Wang S.W.. A role for the fission yeast Rqh1 helicase in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Sci. 2005; 118:5777–5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marchetti M.A., Kumar S., Hartsuiker E., Maftahi M., Carr A.M., Freyer G.A., Burhans W.C., Huberman J.A.. A single unbranched S-phase DNA damage and replication fork blockage checkpoint pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002; 99:7472–7477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takahashi K., Imano R., Kibe T., Seimiya H., Muramatsu Y., Kawabata N., Tanaka G., Matsumoto Y., Hiromoto T., Koizumi Y. et al.. Fission yeast Pot1 and RecQ helicase are required for efficient chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011; 31:495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilson S., Warr N., Taylor D.L., Watts F.Z.. The role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rad32, the Mre11 homologue, and other DNA damage response proteins in non-homologous end joining and telomere length maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999; 27:2655–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kibe T., Ono Y., Sato K., Ueno M.. Fission yeast Taz1 and RPA are synergistically required to prevent rapid telomere loss. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007; 18:2378–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rog O., Miller K.M., Ferreira M.G., Cooper J.P.. Sumoylation of RecQ helicase controls the fate of dysfunctional telomeres. Mol. Cell. 2009; 33:559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jahn C.L., Klobutcher L.A.. Genome remodeling in ciliated protozoa. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002; 56:489–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilkie A.O., Lamb J., Harris P.C., Finney R.D., Higgs D.R.. A truncated human chromosome 16 associated with alpha thalassaemia is stabilized by addition of telomeric repeat (TTAGGG)n. Nature. 1990; 346:868–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gao Q., Reynolds G.E., Wilcox A., Miller D., Cheung P., Artandi S.E., Murnane J.P.. Telomerase-dependent and -independent chromosome healing in mouse embryonic stem cells. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2008; 7:1233–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lydeard J.R., Lipkin-Moore Z., Jain S., Eapen V.V., Haber J.E.. Sgs1 and exo1 redundantly inhibit break-induced replication and de novo telomere addition at broken chromosome ends. PLoS Genet. 2010; 6:e1000973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chung W.H., Zhu Z., Papusha A., Malkova A., Ira G.. Defective resection at DNA double-strand breaks leads to de novo telomere formation and enhances gene targeting. PLoS Genet. 2010; 6:e1000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou J., Monson E.K., Teng S.C., Schulz V.P., Zakian V.A.. Pif1p helicase, a catalytic inhibitor of telomerase in yeast. Science. 2000; 289:771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Myung K., Datta A., Chen C., Kolodner R.D.. SGS1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of BLM and WRN, suppresses genome instability and homeologous recombination. Nat. Genet. 2001; 27:113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cullen J.K., Hussey S.P., Walker C., Prudden J., Wee B.Y., Dave A., Findlay J.S., Savory A.P., Humphrey T.C.. Break-induced loss of heterozygosity in fission yeast: dual roles for homologous recombination in promoting translocations and preventing de novo telomere addition. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007; 27:7745–7757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prudden J., Evans J.S., Hussey S.P., Deans B., O’Neill P., Thacker J., Humphrey T.. Pathway utilization in response to a site-specific DNA double-strand break in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2003; 22:1419–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pai C.C., Blaikley E., Humphrey T.C.. DNA double-strand break repair assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018; 2018:289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Niwa O., Matsumoto T., Yanagida M.. Construction of a minichromosome by deletion and its mitotic and meiotic behaviour in fission yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1986; 203:397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanaka H., Ryu G.H., Seo Y.S., Tanaka K., Okayama H., MacNeill S.A., Yuasa Y.. The fission yeast pfh1(+) gene encodes an essential 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase required for the completion of S-phase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:4728–4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Watson A.T., Werler P., Carr A.M.. Regulation of gene expression at the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe urg1 locus. Gene. 2011; 484:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moreno S., Klar A., Nurse P.. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991; 194:795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Keeney J.B., Boeke J.D.. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994; 136:849–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maundrell K. Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene. 1993; 123:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leupold U., Gutz H.. Genetic fine structure in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc.XI Int. Congr. Genet. 1964; 2:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ahmad F., Kaplan C.D., Stewart E.. Helicase activity is only partially required for Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rqh1p function. Yeast. 2002; 19:1381–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Goodwin A., Wang S.W., Toda T., Norbury C., Hickson I.D.. Topoisomerase III is essential for accurate nuclear division in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999; 27:4050–4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vaze M.B., Pellicioli A., Lee S.E., Ira G., Liberi G., Arbel-Eden A., Foiani M., Haber J.E.. Recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest after repair of a double-strand break requires Srs2 helicase. Mol. Cell. 2002; 10:373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang S.W., Goodwin A., Hickson I.D., Norbury C.J.. Involvement of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Srs2 in cellular responses to DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:2963–2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu J., Renault L., Veaute X., Fabre F., Stahlberg H., Heyer W.D.. Rad51 paralogues Rad55-Rad57 balance the antirecombinase Srs2 in Rad51 filament formation. Nature. 2011; 479:245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mangahas J.L., Alexander M.K., Sandell L.L., Zakian V.A.. Repair of chromosome ends after telomere loss in Saccharomyces. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001; 12:4078–4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Myung K., Chen C., Kolodner R.D.. Multiple pathways cooperate in the suppression of genome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2001; 411:1073–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nimonkar A. V, Ozsoy A.Z., Genschel J., Modrich P., Kowalczykowski S.C.. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:16906–16911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tsutsui Y., Khasanov F.K., Shinagawa H., Iwasaki H., Bashkirov V.I.. Multiple interactions among the components of the recombinational DNA repair system in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2001; 159:91–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Smeets M.F., Francesconi S., Baldacci G.. High dosage Rhp51 suppression of the MMS sensitivity of DNA structure checkpoint mutants reveals a relationship between Crb2 and Rhp51. Genes Cells. 2003; 8:573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sugawara N. DNA Sequences at the Telomeres of the Fission Yeast S. pombe. 1988; Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Malkova A., Naylor M.L., Yamaguchi M., Ira G., Haber J.E.. RAD51-dependent break-induced replication differs in kinetics and checkpoint responses from RAD51-mediated gene conversion. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005; 25:933–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Haruta N., Akamatsu Y., Tsutsui Y., Kurokawa Y., Murayama Y., Arcangioli B., Iwasaki H.. Fission yeast Swi5 protein, a novel DNA recombination mediator. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2008; 7:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sugawara N., Wang X., Haber J.E.. In vivo roles of Rad52, Rad54, and Rad55 proteins in Rad51-mediated recombination. Mol. Cell. 2003; 12:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Taylor M.R., Spirek M., Chaurasiya K.R., Ward J.D., Carzaniga R., Yu X., Egelman E.H., Collinson L.M., Rueda D., Krejci L. et al.. Rad51 paralogs remodel pre-synaptic Rad51 filaments to stimulate homologous recombination. Cell. 2015; 162:271–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brenneman M.A., Wagener B.M., Miller C.A., Allen C., Nickoloff J.A.. XRCC3 controls the fidelity of homologous recombination: roles for XRCC3 in late stages of recombination. Mol. Cell. 2002; 10:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Braybrooke J.P., Li J.L., Wu L., Caple F., Benson F.E., Hickson I.D.. Functional interaction between the Bloom's syndrome helicase and the RAD51 paralog, RAD51L3 (RAD51D). J. Biol. Chem. 2003; 278:48357–48366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Argunhan B., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H.. The differentiated and conserved roles of Swi5-Sfr1 in homologous recombination. FEBS Lett. 2017; 591:2035–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Greider C.W. Telomeres do D-loop-T-loop. Cell. 1999; 97:419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bonetti D., Martina M., Clerici M., Lucchini G., Longhese M.P.. Multiple pathways regulate 3′ overhang generation at S. cerevisiae telomeres. Mol. Cell. 2009; 35:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kramer K.M., Haber J.E.. New telomeres in yeast are initiated with a highly selected subset of TG1-3 repeats. Genes Dev. 1993; 7:2345–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Putnam C.D., Pennaneach V., Kolodner R.D.. Chromosome healing through terminal deletions generated by de novo telomere additions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:13262–13267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pennaneach V., Putnam C.D., Kolodner R.D.. Chromosome healing by de novo telomere addition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2006; 59:1357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.