Abstract

There is a paucity of information on the intermediate behavioral pathways linking exposure to racial discrimination with negative health outcomes among racial and ethnic minority populations in low income settings. This study examined the association between experiences of discrimination and the number of unhealthy days due to physical or mental illness and whether alcohol use influenced the association. A community needs assessment was conducted from 2013-2014 within a low-income community in Florida. Structural equation modeling was performed using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. In a total of 201 observations, path analyses uncovered significant positive indirect associations (p<0.05) between perceived discrimination and unhealthy days through perceived stress, sleep disturbances, and chronic illness. Although a maladaptive mechanism, alcohol use was a strong buffer on the effects of racism on stress.

Keywords: Racism, Psychosocial stress, Quality of life, Mental illness

1. Background

Little is known about the intermediate behavioral pathways linking exposure to racism with negative health outcomes among racial and ethnic minorities in low income settings. However, it is clear that the discrimination targeting Americans of color continues to be a systemic problem that prevails through racist stereotypes, ideologies, and narratives.1 Moreover, a culture of white racial framing of “health disparities” in medicine has developed from these ideologies and practices, which hinder the identification of explanatory pathways of maladaptive behaviors and adverse health outcomes for Americans of color.2

The defining feature of racism is the subjugation of a racial group such that individuals within that group feel inferior and are humiliated.1 This subjugation has been both widespread through systemic avenues and perpetuated on a personal level against Black Americans within the United States (U.S.) for centuries. In his Theory of Oppression, JR Feagin describes a number of socio-economic domains that exist and maintain this paradigm including but not limited to: (1) a predominating racial hierarchy in which whites are superior; (2) comprehensive white racial framing in the form of beliefs and behaviors against Blacks based on preconceived notions and stereotypes; and (3) consistent inequities in the allotment and distribution of materials driven by racial differences in favor of white Americans.2

Given this premise, Black Americans are faced with lifelong chronic stress and allostatic load.3 Consequently, the cumulative burden of the adverse physical, social and mental effects of racism could result in impaired quality of life, chronic illness, and increased mortality.1 Little is known about negative lifestyles among racial minorities that are adopted as ways to cope with perceived discrimination. In this paper, we sought to examine the association of experiences of discrimination (EOD) and the number of unhealthy days due to physical or mental illness per month. In addition, we examined the role of other negative lifestyles, particularly, alcohol intake in the mediation analysis. Alcohol intake is of global importance due to the persistent rise in alcohol consumption worldwide.4

2. Methods

We conducted a community needs assessment survey from November 2013 through March 2014 in a defined urban sample of ethnic minority residents of Tampa, Florida. A total of 201 adults participated in the self-administered computer-based survey using Android tablets.5 Survey content was guided by the Life Course Health Development Perspective3 and relied on input from the Community Advisory Board from the larger community-based participatory research project.6

The main outcome variable was the number of unhealthy days due to physical or mental illness during the last month. We included the following covariates: frequency of experiences of discrimination (EOD) in daily situations, perceived stress score (PSS), smoking, alcohol use, physical activity frequency, dietary intake, insufficient sleep, the number of self-reported medical conditions, and demographics (sex, age, education, and black race).

We created a composite variable using the sum of experiences of discrimination in different daily situations (9=items). Our unhealthy days variable was derived from the reported number of unhealthy days per month due to mental or physical illness, a measure of health-related quality of life, which was assessed from the Healthy Days core questions (CDC HRQOL– 4) from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.7

The perceived stress index (PSS) included 4-items that measured stress. We created a sleeplessness variable derived from the number of reported sleepless nights in the last 30 days, a medical conditions variable from a composite of reported medical conditions in the survey. We conducted a path analysis using structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimation and robust standard errors in the MPLUS software, version 7.11.8

3. Results

In a total of 201 observations, 65.7% of the participants were females, a third were unmarried, and around 80% had completed at least high school education. Two-thirds of the participants were Non-Hispanic Blacks while about a quarter were Hispanics. Approximately 56% of the participants had a household income of less than $20,000 whereas almost 60% were employed. Bivariate analyses showed that women, unmarried, and unemployed residents reported a greater number of unhealthy days during the previous month. In the total effects model (initial multiple linear regression model), experience of discrimination was significantly associated with unhealthy days due to physical or mental illnesses, even after controlling for confounders.

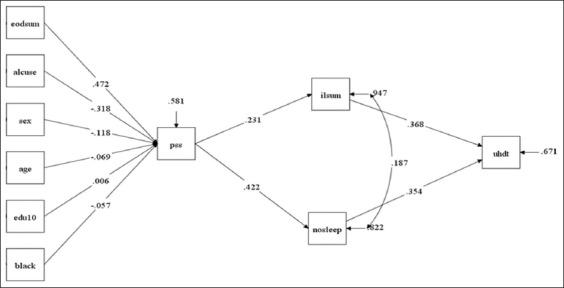

Path analyses examining indirect and direct effects determined mediation pathways with significant positive indirect effects (p<.05) of perceived discrimination on unhealthy days through perceived stress, sleep disturbances, and self-reported medical conditions (model fit: RMSEA 0.048; CFI.99; TLI;.96; Chi-square/DF = 104.4/10). We observed that a unit increase in the level of perceived stress score increased poor sleep by 0.422 standard units. Concurrent medical conditions were slightly correlated with sleep problems. However, medical conditions were jointly influenced by stress (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Standardized coefficients for the relationship between experiences of discrimination (eodsum) and unhealthy days (uhdt) through the mediation of stress (pss) and sleep (nosleep). Alcuse = alcohol use; edu10 = education; ilsum = chronic illness

We also found that among various factors that were adjusted for in the model, only experiences of discrimination and alcohol ingestion were significantly associated with perceived stress (p<.05). By controlling for alcohol use, the relationship between perceived discrimination and perceived stress decreased in magnitude. A total 67.1% of the variance of the “unhealthy days” variable remained unexplained in our full model, meaning that there were other factors that were not accounted for in the study that impacted the health-related quality of life in this community.

4. Discussion and Global Health Implications

We found evidence of an indirect negative effect of perceived discrimination on health-related quality of life mediated through perceived stress, poor sleep and self-reported illnesses. The delineation of this pathway supports the heightened stress response hypothesis and the theory of allostasis.9 The allostatic theory postulates a linkage between psychoneurohormonal responses to stress with physical and psychological manifestations of health and illness.9

We also observed that while experiences of racism increased the perceived stress score, alcohol consumption reduced the score, implying that individuals who were exposed to discrimination were more likely to lower the resulting perceived stress to dampen the effects of the racism exposure by resorting to more alcohol intake. This finding may represent an expression of maladaptive coping mechanism (coping-motivated drinking) that relieves racism-induced stress.10 With significant increases in global alcohol consumption,4 these findings bear important public health implications to address racism-induced stress and structural discrimination.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by grant number 1 D34HP31024-01-00 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for the project titled Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Center of Excellence in Health Equity, Training & Research and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (5R24MD8056-02), National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of BCM, HRSA, or the NIH.

Ethical Approval: Study used publicly available data and was not subject to IRB approval.

References

- 1.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health:Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feagin J, Bennefiled Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. Doi:10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the Black-White gap in birth outcomes:a life-course approach. Ethnicity and Disease. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):S2–62. 76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manthey J, Shield KD, Rylett M, Hasan OSM, Probst C, Rehm J. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030:a modeling study. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2493–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32744-2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salihu HM, Salinas-Miranda A, Turner D, King L, Paothong A, Austin D, Berry EL. Usability of a low-cost Android data collection system for community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships:Research, Education, and Action. 2016;10(2):265–273. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0026. doi:10.1353/cpr.2016.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salinas-Miranda AA, Salemi JL, King LM, Baldwin JA, Berry EL, Austine DA, Scarborough K, Spooner KK, Zoorob RJ, Salihu HM. Adverse childhood experiences and health-related quality of life in adulthood:revelations from a community needs assessment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;11(13):123. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0323-4. DOI 10.1186/s12955-015-0323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [2013]; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. (1998-2011)Mplus User's Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén &Muthén; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganzel BL, Morris PA, Wethington E. Allostasis and the human brain:integrating models of stress from the social and life sciences. Psychol Rev. 117(1):134–174. doi: 10.1037/a0017773. doi:10.1037/a0017773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert PA, Zemore SE. Discrimination and drinking:a systematic review of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:178–194. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.009. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]