Abstract

PURPOSE

Based on the recognition that food insecurity (FI) is associated with poor health across the life course, many US health systems are actively exploring ways to help patients access food resources. This review synthesizes findings from studies examining the effects of health care–based interventions designed to reduce FI.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature published from January 2000 through September 2018 that described health care– based FI interventions. Standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated and pooled when appropriate. Study quality was rated using Grading Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation criteria.

RESULTS

Twenty-three studies met the inclusion criteria and examined a range of FI interventions and outcomes. Based on study design and sample size, 74% were rated low or very low quality. Studies of referral-based interventions reported moderate increases in patient food program referrals (SMD = 0.67, 95% CI, 0.36-0.98; SMD = 1.42, 95% CI, 0.76-2.08) and resource use (pooled SMD = 0.54, 95% CI, 0.31-0.78). Studies describing interventions providing food or vouchers reported mixed results for the actual change in fruit/vegetable intake, averaging to no impact when pooled (–0.03, 95% CI, –0.66 to 0.61). Few studies evaluated health or utilization outcomes; these generally reported small but positive effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a growing base of literature explores health care–based FI interventions, the low number and low quality of studies limit inferences about their effectiveness. More rigorous evaluation of FI interventions that includes health and utilization outcomes is needed to better understand roles for the health care sector in addressing FI.

Key words: food insecurity, public health, social determinants of health, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Clear and convincing evidence demonstrates food insecurity (FI)— restricted access to adequate food due to a lack of money or other resources1—adversely impacts health and well-being across the life course.2–5 As of 2017, 11.8% of US households reported being food insecure at some point during the year, though rates varied by household demographics.6 For example, over 22% of households headed by non-His-panic Black individuals, 18% of households headed by Hispanic individuals, and 16% of households with children were food insecure.6

Reflecting the health care system’s growing interest in addressing patients’ social risk factors,7,8 several professional medical societies now recommend that health care systems integrate FI screening and referrals to food resources into care.9–11 For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians recently announced the EveryONE Project, which recommends family physicians’ use a social risk assessment tool that includes FI measures; they also provide an online resource platform that can be used to help patients find relevant services.12,13 Large, integrated health systems are similarly experimenting with interventions to address FI as a strategy to improve health.14

Despite this growing enthusiasm, there is little clarity about the impacts of FI interventions initiated in health care delivery settings. This systematic review evaluates the evidence on these programs with the aim of better understanding whether and how these health care–sponsored activities impact food security, patient health and health behaviors, and health care utilization and cost.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search Terms

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and clinicaltrials.gov, for studies describing health care–based interventions published from January 2000 through September 2018. The search strategy was developed and refined by 2 study team members (E.H.D., J.M.T.), in consultation with an experienced medical research librarian (E.M.W.). The resulting 2-concept search strategy was adapted to work in each database searched. (Supplemental Appendix, available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/436/suppl/DC1/.)

Food insecurity was defined as limited access to sufficient food due to lack of financial or other resources. We added search terms related to hunger, food-related stress, and social determinants of health to be comprehensive. Intervention terms were used to focus on interventions and exclude articles that only focused on social risk screening. We consulted experts in the field of health care FI research for additional article suggestions. Grey literature available within Web of Science and Embase was reviewed for inclusion. All search terms and other search details are available in Supplemental Table 1, available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/436/suppl/DC1/.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, articles had to describe interventions addressing FI in health care settings. Interventions could address a wider range of adverse social determinants of health (eg, housing or financial insecurity), but were required to specifically describe food security or food access concerns and a description of food security-related outcomes, like food resource use or food security status. Due to the unique national context of health care financing systems, we restricted the review to studies conducted in the United States. Articles had to be published in an English-language, peer-reviewed journal from January 1, 2000 through September 1, 2018. Articles were excluded if they described activities related to FI screening without an associated intervention or did not include data on intervention outcomes.

Data Screening

Search results were stored and organized and duplicates removed in a reference manager. Title, abstract, and full-text screening were completed sequentially using Excel by 2 independent reviewers (E.H.D., J.M.T). After full-text screening, any study recommended by either reviewer was reviewed by an additional author (T.B.). Differences of opinion (n = 4) between reviewers were resolved by discussion at both screening levels. Cited reference searches of the final set of articles were performed in Web of Science.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Extraction tables were constructed to catalog a consistent set of data from each retained article. These data included study design, setting, type of intervention (eg, category of resources/assistance provided), and outcomes evaluated (eg, process measures; social, health, or behavioral outcomes). To compare results from experimental intervention studies, standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated using 2-by-2 frequency tables of outcome frequencies, mean or mean gain scores, and t-test or P values of χ2 tests from 2-by-2 tables (depending on available data). The SMD was calculated either pre- or post-intervention (for single-group studies) or between intervention and control group at follow-up (for comparative trials).15 In cases where data were not included in the original manuscript (n = 3), we contacted study authors to request information for SMD calculations.16–18 Only 1 study team was able to provide additional information.18 Where SMDs were not calculated and for studies reporting descriptive outcomes, results are presented as described in the original publication. Given the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes across the reviewed studies, SMDs were pooled using random effects models only when outcomes of at least 3 studies overlapped. All data pooling was conducted using Stata SE version 15.0 (StataCorp, LLC).

Included studies were assigned quality ratings based on the Grading Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation approach, which considers study design, bias, precision, and consistency of results.19,20 Disagreements between the 3 reviewers regarding quality (n = 6) were discussed until consensus was reached. The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (#CRD42018082622).

RESULTS

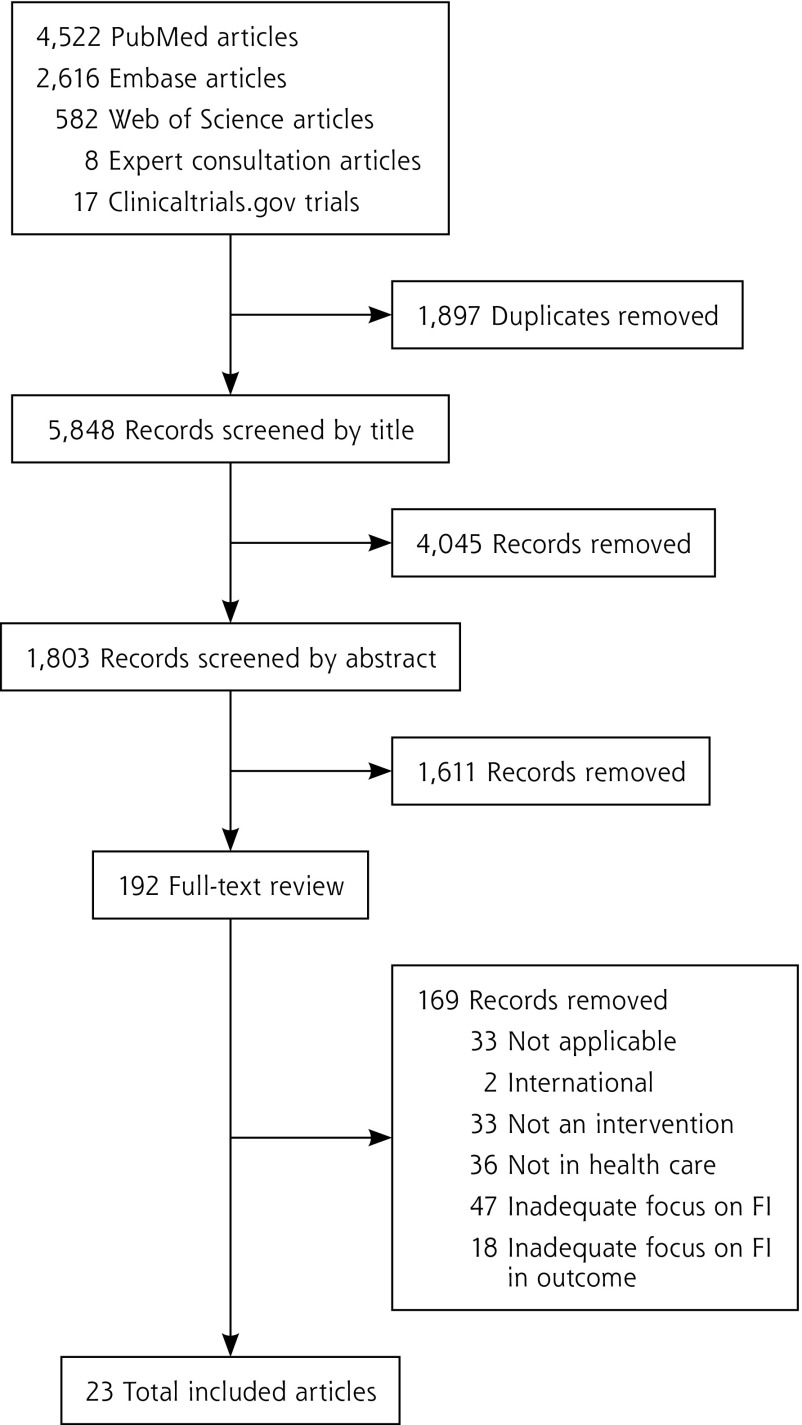

The initial database extraction yielded 5,848 unique articles; 192 underwent full-text review. Twenty-three unique articles met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). There were 2 randomized control trials (RCT) (9%),16,21 1 cluster RCT (4%),22 2 quasi-experimental studies (9%),17,18 3 matched cohort studies (13%),23–25 and 8 single group, pre-/post- studies (35%).26–33 The remainder of the studies had descriptive, mixed methods, or qualitative designs (n = 7, 30%). Some articles focused on specific patient populations: 9 studies evaluated interventions targeting adult caregivers of pediatric patients (39%),16,21,22,28,29,31,34–36 1 targeted adolescents (4%),37 2 focused on pregnant women (9%),18,24 5 focused on patients with diabetes27,30,32,33,39 or another chronic condition25 (22%), and 1 focused on patients with cancer (4%).38 Seventeen studies (74%) were considered low17,26,28,30,31,32,37 or very low quality18,27,29,33–36,38–40 and 6 (26%) studies were rated moderate quality.16,21–25

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

FI = food insecurity.

Interventions fell into 2 categories based on the food-related resources or assistance provided. One group included 12 studies (52%) that described education and/or referral interventions. These provided information for patients about food resources16,22,27,30,35,40 or more actively connected them to referral services through a navigator or other lay staff person.21,24,28,29,34,37 We combined passive (resource information provided) and active (assistance contacting resource) referral interventions into 1 category as results were too heterogenous to make meaningful comparisons between the 2 referral types. A second group included 10 studies (43%) examining interventions that provided food or food vouchers in addition to resource referrals17,18,25,26,31–33,36,38,39 and 1 study that provided food without referrals to community food resources.23

Included studies examined outcomes ranging from: (1) process outcomes (eg, number of patients referred), (2) food security status, (3) health, (4) health behaviors and self-efficacy, (5) health care utilization and/or cost, and (6) patient/caregiver perception of intervention acceptability. No studies reported provider outcomes (eg, provider attitudes or behavior change) related to interventions. Results are summarized below. Tables 1–3 include additional details.

Table 1.

Types of Food Insecurity Interventions and Quality Scores for Included Studies (N = 23)

| Study | Screened for FI? Y/N (Screening Tool)a | Type of Intervention

|

Quality (GRADE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral

|

Food

|

|||||

| Education & Passive | Navigation & Active | Food Vouchers | Food | |||

| Beck,31 2014 | Y (2-item Hunger VS) | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

| Berkowitz,23 2018 | N | ✔ | Moderate | |||

| Bryce,32 2017 | N | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

| Cavanagh,25 2017 | N | ✔ | ✔ | Moderate | ||

| Cohen,17 2017 | Y (1-item screener) | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

| Fleegler,35 2007 | Y (TOA: 6-item USDA FSS) | ✔ | Very low | |||

| Fox,29 2016 | Y (2-item Hunger VS) | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | ||

| Freedman,33 2013 | Y | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | ||

| Freedman,26 2014 | Y (1-item screener) | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

| Gany,38 2015 | Y (18-item USDA FSS) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | |

| Garg,16 2007 | Y (WE CARE: 1-item screener) | ✔ | Moderate | |||

| Garg,22 2015 | Y (WE CARE: Baseline 18-item USDA FSS; F/U 1-item screener) | ✔ | Moderate | |||

| Hassan,37 2015 | Y (TOA: age specific USDA FSS) | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

| Knowles,34 2018 | Y (2-item Hunger VS) | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | ||

| Martel,40 2018 | Y (2-item Hunger VS) | ✔ | Very low | |||

| Morales,24 2016 | Y | ✔ | ✔ | Moderate | ||

| Nguyen,27 2016 | N | ✔ | Very low | |||

| Patel,30 2018 | N | ✔ | Low | |||

| Saxe-Custack,36 2018 | N | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | |

| Sege,21 2015 | Y (SEEK: 2-item screener) | ✔ | ✔ | Moderate | ||

| Smith,39 2017 | Y (6-item USDA FSS) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ b | Very low | |

| Watt,18 2015 | N | ✔ | ✔ | Very low | ||

| Weintraub,28 2010 | N | ✔ | ✔ | Low | ||

FI = food insecurity; F/U = follow up; GRADE = Grading Recommedations Assessment Development and Evaluation; N = no; SEEK = Safe Environment for Every Kid49; TOA = The Online Advocate (now known as HelpSteps)48; 2-item Hunger VS = 2-item Hunger Vital Sign; USDA FSS = United States Department of Agriculture-Food Security Survey; WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education16; Y = yes.

Type of food insecurity screening tool used, if noted in manuscript.

Only a subset of participants, those with diabetes mellitus, were eligible for food.

Table 3.

Non-Process Outcomes of Interventions to Address Food Insecurity in Health Care Settings (n = 11)

| Study | Design | Population | Sample | Intervention or Experimental Condition | Outcomes | Effect Size: SMD, (95% CI), variancea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention type: referrals | ||||||

| Hassan,37 2015 | Prospective observational | Patients aged 15-25 years at an urban adolescent/young adult clinic | 401 youth | Web-based screening and referral tool | Food security: Complete resolution of food as priority problem | 58% (7/13) |

|

| ||||||

| Nguyen,27 2016 | Retrospective observational, pre-/post-intervention, pilot | Self-identified Hispanic patients aged ≥60 years with DM at FQHC | 18/28 participants followed up at 3 months | Referrals from clinic integrated Health Connector Program | Self-efficacy: Change in mean scores on the Stanford Diabetes Self-efficacy Scale Diabetes self-efficacy |

Diet/healthy eating plan: –0.14, (–0.79 to 0.51), 0.11 Physical activity: –0.07, (–0.73 to 0.58), 0.11 Diabetes self-efficacy: 0.30, (–0.35 to 0.96), 0.11 General self-efficacy: 0.13, (–0.52 to 0.79), 0.11 |

|

| ||||||

| Morales,24 2016 | Retrospective observational cohort with propensity score matching | Pregnant patients with FI at obstetrical clinic | 145 adult female patients enrolled; 145 matched not referred | Integrated screening and referral to Food for Families; program for referral to food resources | Health: Blood glucose Health: SBP Health: DBP | 0.10, (–0.13, to 0.33), 0.01 0.33, (0.09-0.56), 0.01 0.27 (0.04-0.51), 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention type: referrals & food/food vouchers | ||||||

| Beck,31 2014 | Observational | Families with infants aged <1 year with FI that stretched formula or infants with failure-to-thrive at large, urban, academic primary care clinic | 1,042 families with infants | Supplemental formula and educational materials for as-needed referrals were provided directly (eg, to social workers, MLP, or food pantries) | Utilization: Completed preventative care Utilization: ED visits |

Completed lead test and ASQ: 0.09, (0.04-0.15), <0.01 Received full set of well-infant visits by 14 months: 0.11, (0.05-0.16), <0.01 0.11, (0.05-0.16), <0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Bryce,32 2017 | Pre-/post-intervention | Adult, non-pregnant patients with type 2 DM and HbA1c >6.5 in last 3 months referred by medical provider | 65 patients | Voucher for fruits and vegetables, and health education/coaching at health center-based farmers market | Health: Weight change Health: SBP change Health: DBP change Health: Drop in HbA1c | –0.08, (–0.30 to 0.13), 0.01 –0.04, (–0.26 to 0.17), 0.01 0.15, (–0.06 to 0.37), 0.01 0.39, (0.17-0.60), 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Cavanagh,25 2017 | Retrospective matched cohort; pre-/post-intervention | Adult low-income patients with obesity, hypertension, and/or type 2 DM | 54 intervention, 54 matched controls | Voucher (prescription coupon) for weekly mobile produce market | Health: BMI change | –0.11, (–0.18 to –0.05), <0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Cohen,17 2017 | Quasi-experimental, pre-/post-intervention | SNAP-enrolled adult primary care patients | 177 patients | Brief clinic-based intervention associated with increase in use of SNAP incentive program | Health behavior: Increased fruits/vegetable consumptionb | 0.49, (0.25-0.73), 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Freedman,33 2013 | Pre-/post-intervention, pilot | Adult patients of FQHCs with farmers markets with DM | 41 patients | Community-based participatory research approach for onsite farmers market; financial incentive program to purchase food at market | Health behavior: Increased fruits/vegetable consumptionc | 0.41, (–0.02 to 0.85), 0.05 at 2-3 months 0.15, (–0.28 to 0.58), 0.05 at 5 months |

|

| ||||||

| Saxe-Custak,36 2018 | Qualitative | Adult caregivers of pediatric patients at an urban pediatric clinic | 32 caregivers | Provided vouchers for farmers market or bag of food when market closed; cooking/nutrition classes | Acceptability Health behavior: Increased fruits/vegetable consumption Food security |

Appreciated convenience of clinic within farmers market building Preferred prescription vouchers over food bags Reported increased Improved food security and access to healthy foods |

|

| ||||||

| Watt,18 2015 | Quasi-experimental prospective | Adult Hispanic pregnant women at low-income Texas primary care clinic | 32 intervention, 29 control | Prenatal care-based nutrition education, food resources education, and farmers market vouchers | Health behavior: Increased fruits/vegetable consumptiond Health: Depression (mean gain PHQ2 score) Health: Excess maternal weight gain Health: Breastfeeding at age 6 months Health: Pass ASQ screening |

Fruits: d = 0.47e,f Vegetables: –0.71, (-1.19 to -0.22), 0.06 d-0.34,(–0.91 to 0.22), 0.08f –0.19, (–0.80 to 0.41), 0.09 0.64, (–0.06 to 1.34), 0.13 0.71, (–0.05 to 1.48), 0.15 |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention type: food only | ||||||

| Berkowitz,23 2018 | Matched cohort | Adult patients with dual Medicaid/Medicare eligibility; members of Common-wealth Care Alliance | Medically tailored meals program: 133 intervention, 1,002 matched controls. Nontailored food program: 624 intervention, 1,318 matched controls | Provided food: impact of medically tailored meal delivery and Meals on Wheels | Utilization: ED visits, inpatient admissions, use of ET Cost: Medical spending |

Medically tailored: ED visits: –0.26, (–0.4 to –0.10), 0.01; Inpatient admissions: –0.09, (–0.27 to 0.09), 0.01; Use of ET: –0.15, (–0.34 to 0.03), 0.01 Non-medically tailored: ED visits: –0.15, (–0.25 to –0.06), <0.01; Inpatient admissions: –0.03, (–0.13 to 0.06), <0.01; Use of ET: –0.07, (–0.17 to 0.02), <0.02 Medically tailored: lower medical spending; net savings $220 per participant Nontailored: lower medical spending: Net savings $10 per participant |

ASQ = Ages and Stages Questionnaire; BMI = body mass index; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; DM = diabetes mellitus; ED = emergency department; ET = emergency transportation; FI = food insecurity; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin; MLP = medical-legal partnership; PHQ2 = Patient Health Questionnaire-2; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SMD = standard mean differences; SNAP = supplemental nutrituion assistance program.

Effect sizes are presented as standardized mean differences (d) unless sufficient alternatives were provided in the reviewed manuscripts (eg, Odds Ratios [ORs]). Effect sizes were not calculated when a plausible control/comparison group was not available to compare with the intervention group and/or if insufficient details were provided in the manuscript and we did not receive responses to requests for further information from study authors.

Increase in fruit/vegetable consumption (servings/day) at 5-month follow-up (n = 138).

Servings/day.

Reported as change from less than 3 servings to 3 or more servings per day; raw data unavailable to adjust results to report as servings per day, as would need to adjust standard deviation.

95% CI and varience not calculable as mean gain for control group = 0.

Author provided additional data points to enable effect size calculation.

Process Outcomes

All of the referral-based studies included process outcomes (n = 12, 52%). Some described rates of food resource referrals; others described either program enrollment or use of resources. Rates of patients receiving referrals as a result of the intervention ranged from 30% to 75% (Table 2).16,22,27,29,35,40 In 2 RCTs, medical providers were more likely to provide food referrals to families who were asked about social needs (by a research assistant16 or self-completed form22), compared with families who were not (SMD = 1.42, 95% CI, 0.76-2.0816 and SMD = 0.67, 95% CI, 0.36-0.9822). A separate RCT showed no difference in food resource interest or use between control group participants (patients who received as needed social work referrals) compared with intervention group participants (patients who received additional navigation support with referrals, including to food resources) (SMD = 0.18, 95% CI, –0.08 to 0.43).21

Table 2.

Process Outcomes of Interventions to Address Food Insecurity in Health Care Settings (N = 17)

| Study | Design | Population | Sample | Intervention | Process Outcomes | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention type: referrals | ||||||

| Garg,16 2007 | RCT | Caregivers of pediatric patients aged 2 months to 10 years at well-child visits | 98 intervention, 95 control | Intervention caregivers screened with 10-item questionnaire for social needs in waiting room before well-child visits | Referral to food resource (pantry, foods stamps, WIC) | 1.42 (0.28-2.56), 0.34a |

|

| ||||||

| Garg,22 2015 | Cluster RCT | Adult caregivers of pediatric patients aged ≤6 months at well-child visits in 8 urban community health centers | 336 mothers (168 per study arm) | Intervention familes screened with WE CARE tool for referral to social resources | Enrollment in community resources Referral to food resources |

Food assistance program: 0.14 (–0.30 to 0.58), 0.05a

Food pantry: 0.40 (–0.38 to 1.17), 0.16a 0.67 (0.25-1.09), 0.05a |

|

| ||||||

| Fleegler,35 2007 | Cross-sectional | Families of children aged 0-6 years who attended well-child visits at 2 urban pediatric clinics | 205 parents (68 with FI) | Families screened with computer-based questionnaire for referrals to resources | Referral to food resources Frequency of contacting referral agency | 35% (24/68) of FI patients referred 67% (16/24) contacted food resource; 94% (15/16) deemed referral helpful |

|

| ||||||

| Fox,29 2016 | Pre-/post-intervention, pilot | New patients at a pediatric weight management clinic | 116 patients | Intervention to partner clinic with Second Harvest Heartland food bank with SNAP enrollment outreach | Enrollment in SNAP | 34% (40/116) eligible for referral; 75% (30/40) accepted; 20% (3/15) completed enrollmentb |

|

| ||||||

| Hassan,37 2015 | Prospective observational | Patients aged 15-25 years at an urban adolescent/young adult clinic | 401 youth | Web-based screening and referral tool | Frequency of contacting any referral agency (not food specific) | 40% (104/259) |

|

| ||||||

| Knowles,34 2018 | Mixed methods | Caregivers of pediatric patients aged <5 years eligible for benefits | 103 families | Integrated clinic-based referral intervention | Enrollment in SNAP | 42% (43/103) eligible completed 85 applications; 32% (27/85) approved; 8% (7/85) denied; 60% (51/85) unknown 63% (12/19) enrolled |

|

| ||||||

| Martel,40 2018 | Retrospective observational | Patients of urban county hospital/emergency department | 1,519 patients | Clinic parntership with Second Harvest Heartland food bank | Frequency of contacting referral agency Enrollment in SNAP | 74% (1,129/1,519) successfully contacted; 63% (954/1519) accepted; 92% (878/954) connected with >1 food resource 76% (338/446) of SNAP eligible completed applications |

|

| ||||||

| Morales,24 2016 | Retrospective observational cohort with propensity score matching | Pregnant patients with food insecurity at obstetrical clinic | 145 adult female patients | Integrated screening and referral to Food for Families; program for referral to food resources | Enrollment in benefits | 67% (97/145) enrolled |

|

| ||||||

| Nguyen,27 2016 | Retrospective observational, pre-/post-intervention, pilot | Self-identified Hispanic patients aged ≥60 years with DM, at FQHC | 18/28 participants followed up at 3 months | Referrals from clinic integrated Health Connector Program | Frequency of contacting referral agency | 33% (6/18) requested food referral; 22% (4/18) contacted food resources |

|

| ||||||

| Patel,30 2018 | Pre-/post-intervention, pilot | Adult patients with DM at endocrinology clinic with access to telephone and documented financial difficulties | 104 patients | Financial burden resource tool | Increase in use of farmers markets, groceries that accept food assistance | 0.12 (–0.16 to 0.40), 0.02a |

|

| ||||||

| Sege,21 2015 | RCT | Families with newborns aged <10 weeks at pediatric primary care clinic | 167 intervention, 163 control | Intervention group was paired with a trained family specialist who provided support (including home visits) and direct assistance accessing resources | Food resource use | 0.18 (–0.08 to 0.43), 0.02a |

|

| ||||||

| Weintraub,28 2010 | Prospective cohort | Pediatric patients at Peninsula family advocacy program | 109 participants of family advocacy program, 102 enrolled, 54 completed follow-up | Integrated clinic- and hospital-based legal services | Increase in use of food support | WIC: 0.73 (0.18-1.28), 0.08a; CalWORKS: 0.65 (0.11-1.20), 0.08)a; Food stamps: 0.73 (0.18-0.28), 0.08a |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention type: referrals & food | ||||||

| Beck,31 2014 | Observational | Families with infants aged <1 year with FI that stretched formula or infants with failure-to-thrive at large, urban, academic pediatric primary care clinic | 1,042 families | Supplemental formula and educational materials for as-needed referrals were provided directly (eg, to social workers, MLP, or food pantries) | Use of social resources (social work and MLP) | 0.11 (0.05-0.16), <0.01a |

|

| ||||||

| Cohen,17 2017 | Quasi-experimental; pre-/post-intervention | SNAP-enrolled adult primary care patients | 177 patients | Brief clinic-based intervention associated with increase in uptake of SNAP incentive program | Double-up food bucks use | Unadjusted OR 9.2 (95% CI, 6.1-13.8); Adjusted OR 19.2 (95% CI, 0.3-35.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Freedman,26 2014 | Pre-/post-intervention | Adult patients of FQHCs with farmers markets | 336 patients enrolled in Shop N Save (financial incentive for farmers market) | Intervention to increase use of clinic-based farmers market and government food resources | Farmers market revenue Use of government food assistance | Increased from $14,285.60 to $15,719.73 (P <.001) Use of all forms food assistance: 0.51 (0.44-0.59), <0.01a; Senior farmers market nutrition program: 0.76 (0.65-0.86), <0.01a; SNAP: 0.64 (0.48-0.81), 0.01a |

|

| ||||||

| Gany,38 2015 | Nested cohort, observational | Hospital-based food pantries at 5 cancer clinics | 351 adult patients | Use of hospital-based food pantry after enrollment in program | Repeat use of food pantry | Median return visits = 2; mean = 3.25 (SD = 3.07) |

|

| ||||||

| Smith,39 2017 | Cross-sectional | Student-run free clinic | 463 adult patients | Integrated FI screening and intervention at free clinic | Use of onsite food boxes, off-site food pantry, and SNAP enrollment | 43% (201/463) receiving monthly boxes of food; 14% (66/463) using off-site food pantry; 14% (64/463) enrolled in SNAP |

CalWORKS = Calif. work opportunities and responsibilities to kids program; DM = diabetes mellitus; FI = food insecurity; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; MLP = medical-legal partnership; OR = odds ratio; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation; SMD = standardized mean difference; SNAP = supplemental nutrition assistance program; WE CARE = Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education; WIC = women, infants, and children supplemental nutrition assistance program.

Statistical results for standard mean differences are shown in format with SMD, (95% CI), varience.

Follow-up available for only 15 participants.

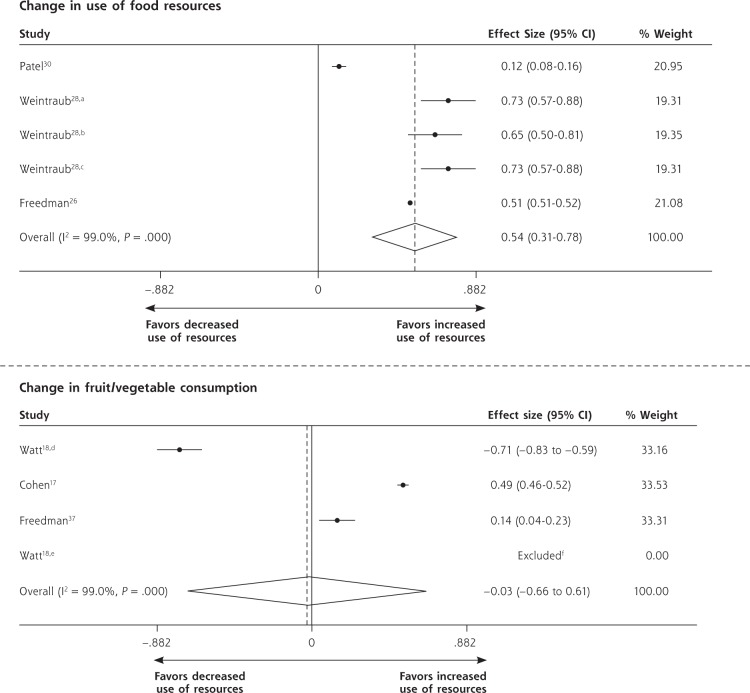

Other studies reported on rates of food program enrollment or utilization.* One study found only modest effects of a waiting room–based intervention on patient enrollment in food-related resources (Table 2).22 Three other studies (13%) reported on change in patients’ use of food resources and described moderate increases in food resource use (pooled SMD = 0.54, 95% CI, 0.31-0.78; Table 2 & Figure 2).26,28,30 These studies were particularly vulnerable to selection bias, given study design.

Figure 2.

Forest plots for individual and pooled SMDs by study outcomes using random effects models.

CalWORKS = Californial work opportunities and responsibilities to kids program; SMD = standard mean difference; WIC = women, infants, and children supplemental nutrition assistance program.

aChange in receipt of WIC.

bChange in receipt of CalWORKS.

cChange in receipt of food stamps.

dChange in vegetable consumption.

eChange in fruit consumption.

f95% CI and variance not calculable as mean gain for control group was zero. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

Food Security Status Outcome

Two studies (9%) indirectly reported post-intervention patient food security status; neither used a validated screening tool to assess FI. One referral-based study found that post-intervention, 58% of patients (n = 7) reported their food-related concerns had resolved.37 In a qualitative study, caregivers of pediatric patients (n = 32) reported improved access to fresh fruits/vegetables after the clinic introduced an on-site farmers market and began distributing food/vouchers.36

Health Behavior and Self-Efficacy Outcomes

Four studies (17%) examined changes in fruit/vegetable intake.17,18,33,36 Pooling effect sizes for the 3 quantitative studies showed no intervention effect (pooled SMD = –0.03, 95% CI, –0.66 to 0.61; Figure 2),17,18,33 though in qualitative interviews, caregivers of pediatric patients reported increased consumption of fresh fruits/vegetables after participating in a food/voucher program.36

One referral-based study examined intervention impacts on diabetes self-efficacy scores in diabetic patients aged 60 years or older.27 There were no significant effects of the intervention on self-efficacy scores at 3-month follow-up (Table 3).

Health Outcomes

Five studies (22%) reported on patient health outcomes. Each study examined different metrics. One referral program in pregnant women attending an obstetrics clinic found a small improvement in blood pressure control during pregnancy.24 A separate prenatal nutrition intervention included general nutritional information, cooking classes, and distribution of vouchers for fruits/vegetables at a local farmers market.18 The evaluation showed no significant effect on infant or maternal outcomes18 (Table 3).

In another study, families with infants aged 12 months or younger that screened positive for FI (or met other eligibility criteria such as clinician concern for FI risk or failure-to-thrive) were provided supplemental formula, educational materials, and as-needed referrals to social work, medical-legal partnerships, or food pantries.31 Infant recipients of these resources were compared with non-recipients whom the authors did not identify as being eligible for the program and who were statistically significantly less likely to be publicly ensured, African American, or male. The intervention showed small but significant effects on health indicators including weight-for-length percentile, blood lead level, and developmental screening scores on the Ages & Stages Questionnaire.31

Two studies evaluated an intervention that provided vouchers for an onsite farmers market.25,32 In 1, adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes were offered health education and nutrition counseling.32 The authors found no effect on weight or blood pressure, but a small effect on lowering hemoglobin A1c. The second study in this group provided vouchers through a nutritionist to patients with obesity, hypertension, and/or type 2 diabetes and found a small but significant effect of the intervention on lowering body mass index compared with matched controls25 (Table 3). None of the studies that described health effects also examined FI outcomes, so we could not assess whether changes in food security mediated changes in health outcomes.

Health Care Utilization and Cost Outcomes

Two studies (9%) reported on health care utilization, 1 of which also examined cost. In 1 of these studies, infants enrolled in a nutrition support program showed small but statistically significant changes in emergency department use and receipt of preventive care services/visits compared with infants not in the program (that also had fewer social risk factors at baseline).31 A study of direct food provision was the only included study to examine health care costs.23 In that intervention, Medicaid/Medicare dual eligible patients were provided either medically tailored or nontailored meal deliveries. Health care utilization outcomes in each intervention group were compared with matched controls. Patients who received medically tailored or nontailored meals had fewer ED visits and less use of emergency transportation, while only those receiving medically tailored meals had fewer inpatient admissions. Both meal program groups had lower medical spending than the control group, with highest savings in the medically tailored meal group (Table 3).

Caregiver Acceptability

One study reported on acceptability of a food/voucher intervention to adult caregivers of pediatric patients.36 This qualitative work explored families’ experiences after a clinic relocated to the same building as an urban farmers market. The authors reported that caregivers appreciated the food/voucher program and preferred vouchers over preprepared bags of food.

DISCUSSION

Despite the rapid increase in health care–based FI interventions,11,41,42 this is the first systematic evidence review of health care delivery–based FI interventions. Of the 23 studies that met inclusion criteria, the majority exclusively described process metrics. These studies reported a wide range in food program referral and enrollment rates. When studies reported the effects of FI interventions on actual use of resources (not just enrollment), pooled analyses revealed moderate size positive effects. These studies rarely explored reasons that referrals did not consistently result in program use.

In pooled results from studies that provided food or food vouchers, we found no effects on fruit and vegetable consumption. It is possible that dose or duration of intervention was insufficient to impact consumption or that follow-up periods were either too short or long to observe changes. Challenges in using dietary recall to capture fruit/vegetable intake also may have biased to the null.43 Few studies evaluated health impacts of FI-related interventions. The studies examining either health or utilization outcomes had small effect sizes. Variability in health or utilization measures across studies prevented pooling.

The majority of studies in the review (17/23) were of low or very low quality. Lower quality studies either had no comparison group or compared outcomes to a group significantly different from the intervention group. Many studies had low enrollment and follow-up, limiting statistical power and generalizability. In general, moderate quality studies reported less positive outcomes than lower quality studies. Higher quality studies examining health and utilization/cost outcomes are needed to inform future FI investments.

Findings from this review of health care–based FI interventions should be interpreted with caution. First, both the overall low quality of studies in this review and wide range of populations and settings make it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions. Second, heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes hindered comparisons across studies. Pooling was done when appropriate. Different metrics were used across studies, even when similar outcome categories were included (eg, process, health, or cost outcomes), making it impossible to compare overall impacts of these programs.

Third, we restricted our review to peer-reviewed publications and US health care–based studies; we may have excluded gray literature or international findings that could have important implications for this rapidly growing area of research. Health systems like ProMed-ica44 and Geisinger45 both have robust programs to screen for FI and provide healthy food to patients, but have not published peer-reviewed studies on program impacts. Restricting our review to health care–based studies also excluded potentially informative FI interventions that examine health outcomes but take place in non–health care settings.46,47

Finally, we included studies of interventions that in some cases targeted food in addition to other social determinants of health, making it difficult to directly link multi-faceted interventions with food outcomes. Food insecurity often exists alongside other material deficits related to poverty; it may be artificial to isolate the effects of addressing FI from the effects of addressing other social factors (eg, housing instability).

Despite these limitations, this review offers a timely and relevant summary of evidence in this field across diverse patient populations, health care settings, and types of interventions. It also highlights critical evidence gaps that should guide future research. Though many health care settings are actively exploring ways to reduce patient FI to improve patient health and well-being, there is currently little rigorously conducted research in this area. Early evidence suggests that these programs may help patients better connect with food resources, but more research is needed to better explore impacts on health, health care utilization, and cost.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Seth Berkowitz, MD, Alicia Cohen, MD, MSc, Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, MPH, Megan Sandel, MD, MPH, Rich Sheward, MPP, and John Steiner, MD, MPH, for reading earlier drafts of this manuscript and Holly Wing, MA, for assistance developing the search protocol.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

References 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 34, 37-40.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/436.

Funding support: J.M.T., C.F., and L.M.G. were supported by the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. E.H.D. was supported by a fellowship training grant, National Research Service Award (NRSA) T32HP19025. The manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc, or the NRSA.

Supplemental materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/436/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84972. Published Sep 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryu JH, Bartfeld JS. Household food insecurity during childhood and subsequent health status: the early childhood longitudinal study— kindergarten cohort. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102(11): e50-e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008; 121(1): 65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seligman HK, Bolger AF, Guzman D, López A, Bibbins-Domingo K. Exhaustion of food budgets at month’s end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014; 33(1): 116-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alley DE, Soldo BJ, Pagán JA, et al. Material resources and population health: disadvantages in health care, housing, and food among adults over 50 years of age. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99(Suppl 3): S693-S701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2017. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022. Published Sep 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azar AM., II The root of the problem: America’s social determinants of health. US Department of Health & Human Services; https://www.hhs.gov/about/leadership/secretary/speeches/2018-speeches/the-root-of-the-problem-americas-social-determinants-of-health.html. Published Nov 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, Karva F, Lewin-Zwerdling A. Implementing food security screening and referral for older patients in primary care: a resource guide and toolkit. HCBS Clearinghouse http://www.nasuad.org/node/68906. Published Nov 30, 2016.

- 10.Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Nutrition. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(5): e1431-e1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EveryONE project unveils social determinants of health tools. American Academy of Family Physicians; https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180109sdohtools.html.) Published Jan 9, 2018 Accessed Mar 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The EveryONE Project: Screening Tools and Resources to Advance Health Equity. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project/tools.html#patients Accessed Aug 6, 2018.

- 13.Neighborhood Navigator. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project/neighborhood-navigator.html. Published 2018.

- 14.Hussein T, Collins M. The community cure for health care. Stanford Social Innovation Review 2016; 14(3). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator. https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/this-is-a-web-based-effect-size-calculator/explore/this-is-a-web-based-effect-size-calculator. Published 2017 Accessed Feb 19, 2019.

- 16.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007; 120(3): 547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen AJ, Richardson CR, Heisler M, et al. Increasing use of a healthy food incentive: a waiting room intervention among low-income patients. Am J Prev Med. 2017; 52(2): 154-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt TT, Appel L, Lopez V, Flores B, Lawhon B. A primary care-based early childhood nutrition intervention: evaluation of a pilot program serving low-income Hispanic women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015; 2(4): 537-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008; 336(7650): 924-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008; 336(7651): 995-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sege R, Preer G, Morton SJ, et al. Medical-legal strategies to improve infant health care: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(1): 97-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015; 135(2): e296-e304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkowitz SA, Terranova J, Hill C, et al. Meal delivery programs reduce the use of costly health care in dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018; 37(4): 535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales ME, Epstein MH, Marable DE, Oo SA, Berkowitz SA. Food insecurity and cardiovascular health in pregnant women: results from the Food for Families Program, Chelsea, Massachusetts, 2013-2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016; 13: E152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavanagh M, Jurkowski J, Bozlak C, Hastings J, Klein A. Veggie Rx: an outcome evaluation of a healthy food incentive programme. Public Health Nutr. 2017; 20(14): 2636-2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman DA, Mattison-Faye A, Alia K, Guest MA, Hébert JR. Comparing farmers’ market revenue trends before and after the implementation of a monetary incentive for recipients of food assistance. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014; 11: E87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen AL, Angulo M, Haghi LL, et al. A clinic-based pilot intervention to enhance diabetes management for elderly Hispanic patients. J Health Environ Educ. 2016; 8: 1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weintraub D, Rodgers MA, Botcheva L, et al. Pilot study of medical-legal partnership to address social and legal needs of patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010; 21(2)(Suppl): 157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox CK, Cairns N, Sunni M, Turnberg GL, Gross AC. Addressing food insecurity in a pediatric weight management clinic: a pilot intervention. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016; 30(5): e11-e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel MR, Resnicow K, Lang I, Kraus K, Heisler M. Solutions to address diabetes-related financial burden and cost-related nonadherence: results from a pilot study. Health Educ Behav. 2018; 45: 101-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AF, Henize AW, Kahn RS, Reiber KL, Young JJ, Klein MD. Forging a pediatric primary care-community partnership to support food-insecure families. Pediatrics. 2014; 134(2): e564-e571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryce R, Guajardo C, Ilarraza D, et al. Participation in a farmers’ market fruit and vegetable prescription program at a federally qualified health center improves hemoglobin A1C in low income uncontrolled diabetics. Prev Med Rep. 2017; 7: 176-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman DA, Choi SK, Hurley T, Anadu E, Hébert JRA. A farmers’ market at a federally qualified health center improves fruit and vegetable intake among low-income diabetics. Prev Med. 2013; 56(5): 288-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowles M, Khan S, Palakshappa D, et al. Successes, challenges, and considerations for integrating referral into food insecurity screening in pediatric settings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018; 29(1): 181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007; 119(6): e1332-e1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxe-Custack A, Lofton HC, Hanna-Attisha M, et al. Caregiver perceptions of a fruit and vegetable prescription programme for low-income paediatric patients. Public Health Nutr. 2018; 21(13): 2497-2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan A, Scherer EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. Improving social determinants of health: effectiveness of a web-based intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49(6): 822-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gany F, Lee T, Loeb R, et al. Use of hospital-based food pantries among low-income urban cancer patients. J Community Health. 2015; 40(6): 1193-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith S, Malinak D, Chang J, et al. Implementation of a food insecurity screening and referral program in student-run free clinics in San Diego, California. Prev Med Rep. 2017; 5: 134-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martel ML, Klein LR, Hager KA, Cutts DB. Emergency department experience with novel electronic medical record order for referral to food resources. West J Emerg Med. 2018; 19(2): 232-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Food Research and Action Center. Addressing food insecurity: a toolkit for pediatricians. http://www.frac.org/aaptoolkit. Published 2018 Accessed Aug 15, 2018.

- 42.Loopstra R. Interventions to address household food insecurity in high-income countries. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018; 77(3): 270-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bash H. Food as medicine: food prescriptions coming to Cleve-land community. News5Cleveland. https://www.news5cleveland.com/news/local-news/cleveland-metro/food-as-medicine-prescriptions-for-food-hope-to-fuel-cleveland-community. Published Apr 24, 2018.

- 45.Tirrell M, Gralnick J. Diabetes defeated by diet: how new fresh-food prescriptions are beating pricey drugs. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/20/diabetes-defeated-by-diet-new-fresh-food-prescriptions-beat-drugs.html. Published Jun 21, 2018.

- 46.Seligman HK, Lyles C, Marshall MB, et al. A pilot food bank intervention featuring diabetes-appropriate food improved glycemic control among clients in three states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015; 34(11): 1956-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seligman HK, Smith M, Rosenmoss S, Marshall MB, Waxman E. Comprehensive diabetes self-management support from food banks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2018; 108(9): 1227-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.HelpSteps. Boston Childrens Hospital; https://www.helpsteps.com/home/#/home. Published 2018 Accessed Jul 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.SEEK Parent Questionnaire - R (PQ-R) formerly the PQ or PSQ. Seek. https://www.seekwellbeing.org/the-seek-parent-questionnaire-. Published 2018 Accessed Feb 19, 2019.