Abstract

The increase in global warming has favored growth of a range of opportunistic environmental bacteria and allowed some of these to become more pathogenic to humans. Aeromonas hydrophila is one such organism. Surviving in moist conditions in temperate climates, these bacteria have been associated with a range of diseases in humans, and in systemic infections can cause mortality in up to 46% of cases. Their capacity to form biofilms, carry antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and survive disinfection, has meant that they are not easily treated with traditional methods. Bacteriophage offer a possible alternative approach for controlling their growth. This study is the first to report the isolation and characterization of bacteriophages lytic against clinical strains of A. hydrophila which carry intrinsic antibiotic resistance genes. Functionally, these novel bacteriophages were shown to be capable of disrupting biofilms caused by clinical isolates of A. hydrophila. The potential exists for these to be tested in clinical and environmental settings.

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, bacteriophage, genomics, biofilm, antimicrobial resistance

Introduction

Aeromonas hydrophila is a Gram-negative rod found in fresh water, brackish water, and mud in temperate climates (Batra et al., 2016). They are an established fish pathogen causing septicemia and ulcerative diseases (Chowdhury et al., 1990). Aeromonas spp. were first reported as infective agents in humans in 1951, and from that time have been seen as important human pathogens (Janda and Abbott, 2010). A. hydrophila implicated in human infections is usually mesophilic and grows optimally between 35 and 37°C (Janda and Abbott, 2010). Clinical infections may be a result of direct skin invasion from muddy water (Vally et al., 2004) or drinking contaminated water leading to local (gastritis, skin necrotizing infection) or systemic (peritonitis, sepsis, meningitis, respiratory, and hepatic) infections (Janda and Abbott, 2010; Igbinosa et al., 2012). Mortality in systemic infections may be as high as 46% (Dryden and Munro, 1989).

The incidence of A. hydrophila has been correlated to warmer summer periods when the prevalence of this bacterium is increased in harvested rain water (Picard and Goullet, 1987) and in chlorinated or unchlorinated metropolitan water supplies (Burke et al., 1984a, b).

Global climate change and population increases are expected to put greater pressures on water resources (DeNicola et al., 2015) and lead to increased investment in alternative sources such as rain harvesting (Ahmed et al., 2008). This is certainly the case in countries such as Australia, that is experiencing harsher summers and where use of recycled water for human consumption is not in vogue. A. hydrophila is estimated to be present in up to 33% of rain harvested water in Australia’s major cities (Chubaka et al., 2018) and they are known to survive in chlorinated water by forming biofilms (Igbinosa et al., 2012). Biofilms provide bacterial cell-to-cell contact allowing for the transfer of genetic material that enhances the niche and increases resistance to stress and antibiotics (Talagrand-Reboul et al., 2017). Therefore, water originating from rain harvested tanks, municipal supplies, recreational settings such as swimming pools, and in the natural environment may serve as potential sources of infection.

Aeromonas spp. play a major role in the transfer of antibiotic resistance, making these organisms particularly problematic. They have been implicated as mediators of the transfer of antibiotic resistance markers between hospital and environmental strains (Varela et al., 2016), and are associated with innate multi-antibiotic resistance due to efflux pumps, inducible cephalosporinases, and inducible metallo beta lactamases (Azzopardi et al., 2011; Sinclair et al., 2016). Controlling A. hydrophila infection is therefore paramount as this organism threatens food security (by causing fish diseases and increasing their mortality) (Talagrand-Reboul et al., 2017) and human health (Neyts et al., 2000). Since the World Health Organization declaration that antibiotic resistance was a global emergency (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2014), alternatives for antibiotics have been actively researched (Czaplewski et al., 2016).

Bacteriophages, although discovered before antibiotics, have recently emerged as adjuncts and alternatives to antibiotics (Golkar et al., 2014). While temperate (Beilstein and Dreiseikelmann, 2008; Dziewit and Radlinska, 2016) and lytic (Chow and Rouf, 1983; Merino et al., 1990a, b; Shen et al., 2012; Jun et al., 2013; Anand et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Le et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018) bacteriophages against A. hydrophila have been previously reported, these were isolated using environmental and fish pathogenic isolates of A. hydrophila. In the instances where host range was tested, their activity did not extend to clinical strains of A. hydrophila (Wang et al., 2016), that is, strains which were isolated from hospital patients suffering from A. hydrophila infections. Clinical strains of A. hydrophila have been shown to differ from environmental strains including those pathogenic in fish, in their production of virulence factors (Janda and Abbott, 2010), as well as other features. For instance, clinical strains are reported to restrict production of protease activity in favor of cytotoxicity and hemolysin production when temperatures increase from 30 to 37°C (Yu et al., 2007; Rasmussen-Ivey et al., 2016). Further, environmental strains can survive at temperatures as low as 4°C where clinical strain growth is inhibited (Mateos et al., 1993; Rasmussen-Ivey et al., 2016). To date there have been no lytic bacteriophages isolated that have demonstrated killing of clinical strains of A. hydrophila. This study screened for lytic bacteriophages against clinical strains of A. hydrophila associated with various human diseases. The isolated bacteriophages were characterized phenotypically and genomically, and functionally assessed for their capacity to degrade A. hydrophila biofilms.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All methods were performed in accordance with the La Trobe University Ethics, Biosafety, and Integrity guidelines and regulations. Clinical isolates of A. hydrophila were obtained from specimen cultures as part of routine care. Informed consent was obtained from participants for their involvement and use of samples in this study. The study protocols were approved by the La Trobe University Ethics Committee, reference number: S17–111.

Bacterial Growth and Strain Identification

Aeromonas hydrophila bacteria was isolated from a deep wound infection (Strain AHB0117), a polymicrobial liver abscess on a background of cholangiocarcinoma (Strain AHB0148), a polymicrobial surgical site of infection (Strain AHB0116), diarrhea fecal samples (Strain AHB0139), and a scalp abscess due to trauma (Strain AHB0147), all de-identified. All strains were cultured in nutrient broth or agar (Oxoid, Australia) at 37°C aerobically. The bacterial strains were initially identified by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization – Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF; Bruker Daltonik, Germany). Conclusive identification was achieved by sequencing of the 16S rRNA region (see Table 1 for PCR conditions), as well as screening for intrinsic antibiotic resistance markers endogenous to A. hydrophila (see below). The 16s rRNA amplicons were purified using QIAquick® PCR purification kits (Qiagen, Australia) and Sanger sequenced by the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) in Queensland, Australia. The strains that were identified as A. hydrophila were used for subsequent bacteriophage screening.

TABLE 1.

Primers and PCR reaction conditions for bacteria and antibiotic resistance characterization.

| Oligo name | Sequence (5′ – 3′) | Cycling conditions |

| 16S rRNA | U27F: AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG | Hold: 95°C, 3 min 32 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 90 s |

| U492R: AAGGAGGTGWTCCARCC | ||

| CphA beta-lactamase class B | FP: ACTCCATGGTCTATTTCGGG | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 54°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: GTCTTGATCGGCAGCTTCAT | ||

| FOX/MOX beta lactamase class C | FP: TACTATCGCCAGTGGACGCC | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 54°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: TCCGCCGAGCTGGTCTTGAT | ||

| OXA-12 beta lactamase class D | FP: TTTCTCTATGCCGACGGCAA | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 54°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: GTTGCCGTAGTCAAAACGGT | ||

| Chloramphenicol resistance | FP: ATCACCTGGTTCCTGTTCAG | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 54°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: TACCGACGATGACCGCATAA | ||

| MFS transporter | FP: TTCTTCGTGGTGATGCCCAT | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: GAAGATCAGCATCACCTGGA | ||

| Type I-E CRISPR-associate protein Cas5/casD | FP: AACCCTACCTGCTACTATGG | Hold: 95°C, 10 min 35 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 51°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s; 72°C, 10 min |

| RP: ATTCTGGTGACAACGGGCAA |

Antibiotic Sensitivity, Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance, and CRISPR Characterization

Antibiotic sensitivity of the A. hydrophila clinical strains used in this study was assessed using the VITEK® 2 analyzer (bioMérieux, Australia), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole genome sequences of A. hydrophila strains published in the GenBank NCBI database were imported into CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) (Jia et al., 2017) and analyzed for genes coding antibiotic resistance. These genomes were also screened for CRISPR coded sequences using CRISPRFinder (Grissa et al., 2007). Identified sequences from (version 9.5.4) multiple strains were aligned in CLC genomic workbench and PCR primers designed from their conserved regions. The primer sequences and their PCR conditions are listed in Table 1 and amplicons were confirmed by sequencing (AGRF, Australia). Bacteriophage whole genome sequences were also screened for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and CRISPR as above.

Bacteriophage Isolation and Host Range

Wastewater and fishpond samples from Victoria, Australia, were screened for bacteriophages by enriching the samples with A. hydrophila. In brief, 100 μL of log phase A. hydrophila was added to 10 mL of broth with 1 mL of filtered sample (0.2 μm cellulose acetate; Advantec, Australia). This enrichment was incubated for 4 days before filtration, and 10 μL of this filtrate was then spotted onto a bacterial lawn of A. hydrophila on agar to screen for the presence of plaques. Host range testing was performed on five clinical strains of A. hydrophila.

One-Step Growth Analysis

Aeromonas hydrophila strains in exponential growth phase, collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in fresh nutrient broth at a concentration of 0.6U (OD600), were used for the one step growth experiments (Wang et al., 2016). The strain AHB0147 was used for one-step growth experiments involving LAh1–LAh5 bacteriophages while LAh6–LAh10 bacteriophage one-step growth experiments were performed using the strain AHB0116. One hundred microliters of bacteriophage were added to 900 μL of each A. hydrophila strain at a MOI of 0.01 and incubated at 4°C for 30 min to allow for adsorption. Adsorbed bacteriophage were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min and pellet resuspended in 50 mL of fresh nutrient broth. The mixture was incubated aerobically at 37°C and bacteriophages assayed using aliquots collected every 5 min by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Bacteriophage particles were visualized by Transmission Electron Microscopy using a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope (TEM) at 200 kV. Bacteriophage lysate was adsorbed onto 400-mesh formvar and carbon coated copper grids (ProSciTech, Australia) for 1 min. Grids were rinsed with milli-Q water and adsorbed phage particles were negatively stained twice using 2% (W/V) uranyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich®, Australia) for 20 s. Excess stain was removed using filter paper and grids air dried for 30 min. Images were captured on a Gatan Orius SC200D 1 wide-angle camera using the Gatan Microscopy Suite and Digital Micrograph Imaging software (version 2.3.2.888.0). The images obtained were further analyzed using ImageJ (version 1.8.0_112).

Bacteriophage DNA Extraction

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® (Australia), unless stated otherwise. Concentrated bacteriophage stock (approximately 1011 PFU mL–1) was treated with 5 mmol L–1 of MgCl2 as well as RNase A and DNase I (Promega, Australia) to a final concentration of 10 μg mL–1. The digest was incubated at room temperature for 30 min before polyethylene glycol precipitation at 4°C using PEG-8000 at 10% (w/v) and sodium chloride (1 gL–1). Precipitated virions were recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min to obtain a pellet which was then resuspended in 50 μL nuclease free water (Promega, Australia). Viral proteins were digested with 50 μg mL–1 of proteinase K, 20 mmol L–1 EDTA and 0.5% (v/v) of sodium dodecyl sulfate for 1 h at 55°C to release phage DNA. Bacteriophage DNA was separated from proteins by addition of an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (29:28:1) and carefully collecting the aqueous phase after centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. An equal volume of isopropanol and overnight incubation at −20°C was used to precipitate bacteriophage DNA. Bacteriophage DNA was then collected by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 5 min) before washing in 70% ethanol, air-drying, and re-suspending in 30 μL of nuclease free water (Promega, Australia).

Bacteriophage Whole Genome Sequencing and in silico Analysis

Nextera® XT DNA sample preparations kits were used to prepare phage DNA for sequencing according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole genome sequencing of the prepared libraries was performed on an Illumina MiSeq® using a MiSeq® V2 300 cycle reagent kit. Sequence reads were imported into CLC genomics workbench (version 9.5.4) and assembled de novo. Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted and translated using CLC genomics workbench (version 9.5.4). Translated ORFs were analyzed using BLASTP (Mount, 2007) and tRNAs and tmRNAs predicted using ARAGORN (Laslett and Canback, 2004) and tRNAscan-SE 2.0 (Lowe and Chan, 2016). Bacteriophage genomes were also analyzed for CRISPR sequences using the CRISPR database (Grissa et al., 2007). Whole genome alignments of isolated bacteriophages and those against other Aeromonas spp. (sourced from GenBank) were conducted and a phylogenetic tree constructed by neighbor joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in CLC genomics workbench (version 9.5.4). The bacteriophage genomes were also assessed by MAUVE plugin (Darling et al., 2004) in Geneious (version 11.0.5)1.

Biofilm Degradation Assays

The capacity to disrupt A. hydrophila biofilms was determined by growing A. hydrophila mono-biofilms in a 96 well polystyrene plate (Greiner bio-one, Australia). The 96 well plates were inoculated with 100 μL of 108 CFU mL–1 log phase A. hydrophila in broth culture and a further 100 μL of sterile broth added. The cultures were then incubated aerobically at 37°C, shaking, for 4 days. Ten microliters of bacteriophage at a concentration of 108 PFU mL–1 was added to the established biofilms and for each experiment, heat inactivated (autoclaved) bacteriophage was used as a control to confirm that the effects on biofilm were the result of bacteriophage particles, rather than chemical residues or other matter in the preparation. Bacterial attachment was assayed according to Merritt et al. (2005). Briefly, plates were submerged in water to wash cells for 5 min before staining with 200 μL of 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min. The excess crystal violet was removed by submerging the plates in water for 5 min. The stained adherent cells were then solubilized in 70% ethanol and the absorbance in each well determined (at a wavelength of 550 nm) using a FlexStation 3 plate reader (Molecular devices, United States). Bacteriophages LAh7, LAh9, and LAh10 were tested on A. hydrophila strain AHB0116 biofilm whilst LAh1 was tested on biofilm formed by AHB0147.

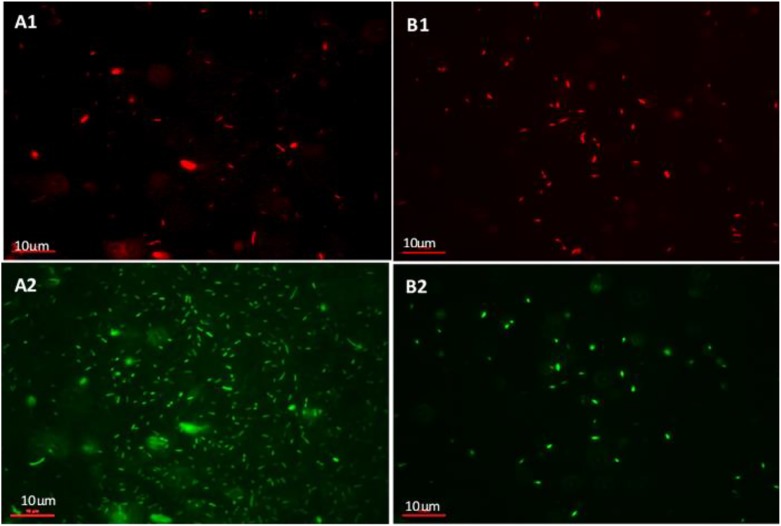

Viability of Biofilm

Aeromonas hydrophila biofilms grown on glass slides were stained with 100 μL of SYBR® gold (Eugene, OR, United States; 1 mg mL–1) diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich®, Australia) and 3 μL of 1 mg mL–1 propidium iodide (PI) in nuclease free water (Promega, Australia) for 30 min in the dark. The live/dead stained cells were mounted with 10 μL Vectorshield® (Burlingame, CA, United States) on coverslips. The stained slides were visualized with an Olympus Fluoview Fv10i-confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Life Science, Australia). PI stained DNA of membrane-compromised cells red while SYBR Gold® stained DNA from both intact and membrane-compromised cells green.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical tests were used to assess the capacity of bacteriophages to break down biofilms from clinical strains of A. hydrophila. Firstly, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess whether, for each individual bacteriophage, biofilm absorbance at OD550nm was normally distributed. As these data were found to be non-normally distributed, biofilm absorbance at OD550nm for each phage was summarized in terms of the median rather than the mean, with the full five-number summaries presented in side-by-side boxplots. The interquartile range (IQR) was also calculated. Due to the non-normality of the data, the biofilm absorbance at OD550nm for each bacteriophage was compared with that for every other phage using a non-parametric test – the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed in SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc., United States).

Results

Antibiotic Resistance in Aeromonas hydrophila

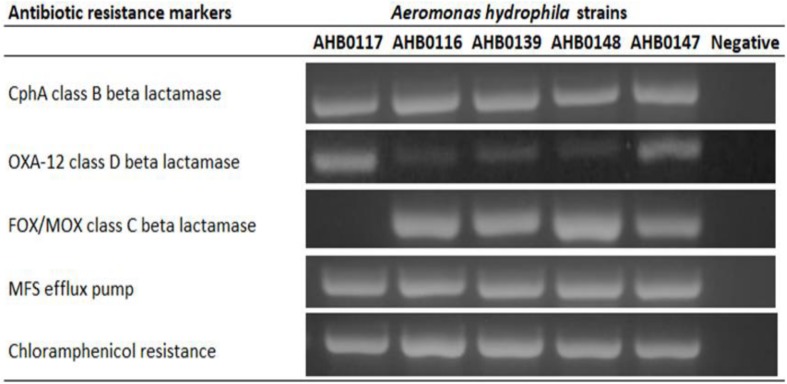

Five clinical isolates identified as A. hydrophila were screened for ARGs by PCR amplification, revealing intrinsic multi-antibiotic resistance. These included genes coding for chloramphenicol resistance (5/5), major facilitator superfamily efflux transporter (5/5), CphA class B beta lactamase (5/5), FOX/MOX class C beta lactamase (4/5), and OXA-12 class D beta lactamases (5/5) (Figure 1). All strains used in this study were susceptible to ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and gentamicin.

FIGURE 1.

PCR detection of antibiotic resistance markers in clinical strains of A. hydrophila used in this study. All resistance genes were present in all clinical strains except class C beta lactamase in AHB0117. The images presented here are taken from two separate gels, which are displayed in Supplementary Figures S1,S2. The white space between these images delineates sections that were cropped from different regions of the gels in Supplementary Figures S1,S2.

Isolation of Novel Bacteriophages Against Clinical Strains of Aeromonas hydrophila

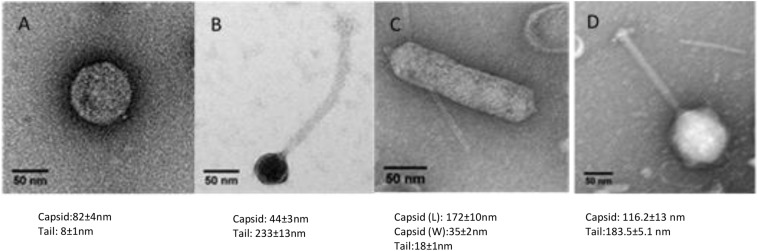

Wastewater and pond samples collected from the cities of Bendigo and Melbourne, Victoria, Australia were screened for bacteriophages. Ten bacteriophages against five clinical strains of A. hydrophila were isolated. Of these, eight were Podoviridae (comprising five icosahedral and three elongated Podoviridae), one was a Siphoviridae and one was a Myoviridae virus. The novel bacteriophages were labeled LAh1–LAh10, with LAh1–LAh5 representing the icosahedral Podoviridae, LAh6, LAh8, and LAh9 representing the elongated version of the Podoviridae, while LAh7 and LAh10 were Siphoviridae and Myoviridae bacteriophages respectively (Figure 2). The elongated Podoviridae bacteriophages had capsid length ≈ 172 ± 10 nm, width ≈ 35 ± 2 nm and tail length ≈ 18 ± 1 nm while the icosahedral Podoviridae had capsid diameter ≈ 82 ± 4 nm and tail ≈ 8 ± 1 nm. The Siphoviridae bacteriophages had capsid length and tail length of ≈ 44 ± 3 nm and ≈232 ± 13 nm, respectively. Myoviridae bacteriophages had capsid diameter of ≈ 116 ± 13 nm and tail length ≈ 183 ± 5 nm (Figure 2). Specific features of the bacteriophages and their characteristics are summarized in Table 2 while their respective one-step growth curves are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Transmission electron microscopy of representative bacteriophages from LAh1–LAh10. (A) Typical morphology of LAh1–LAh5 (icosahedral Podoviridae); (B) LAh7 (Siphoviridae); (C) typical morphology of LAh6, LAh8, and LAh9 (elongated Podoviridae); and (D) LAh10 (Myoviridae). All scale bar at 50 nm.

TABLE 2.

LAh1–LAh10 genotypic and phenotypic characteristics.

| Phage name | Source | EM morphology | Genome size (bp) | ORFs | GC% | Host range (bacterial strain) |

Number of tRNAs | GenBank accession | ||||

| AHB0148 | AHB0147 | AHB0139 | AHB0117 | AHB0116 | ||||||||

| LAh1 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 42002 | 45 | 59.30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 0 | MK838107 |

| LAh2 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 42008 | 45 | 59.30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 0 | MK838108 |

| LAh3 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 42002 | 50 | 59.30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 0 | MK838109 |

| LAh4 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 42002 | 52 | 59.30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 0 | MK838110 |

| LAh5 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 41985 | 53 | 59.30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 0 | MK838111 |

| LAh6 | Fish pond | Podoviridae | 101437 | 165 | 42.30 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 21 | MK838112 |

| LAh7 | Wastewater | Siphoviridae | 61426 | 75 | 61.90 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | MK838113 |

| LAh8 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 97408 | 143 | 42.20 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 21 | MK838114 |

| LAh9 | Wastewater | Podoviridae | 97988 | 147 | 42.40 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 18 | MK838115 |

| LAh10 | Wastewater | Myoviridae | 260310 | 227 | 47.50 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 | MK838116 |

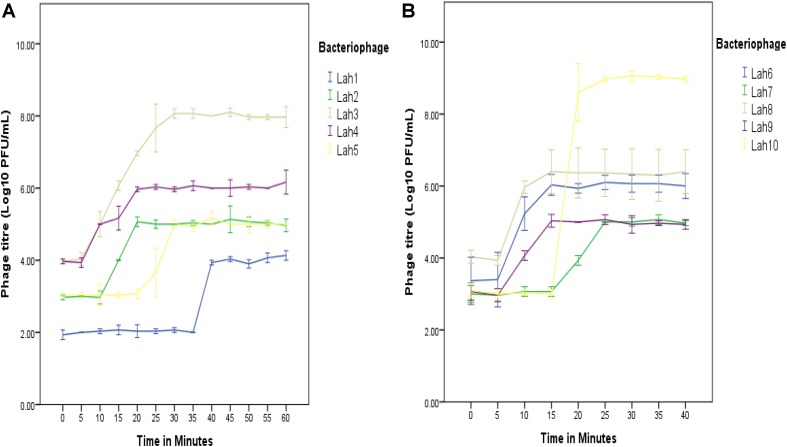

FIGURE 3.

One-step growth curves for A. hydrophila bacteriophages LAh1–LAh10 on two separate bacterial strains (depending on host range specificity). On the same host (A. hydrophila AHB0147), replication kinetics were different for LAh1–LAh5 (A). LAh6–LAh10 differed in their growth kinetics when grown on A. hydrophila strain AHB0116 (B). The standard errors of the mean are calculated from three independent experiments.

Whole Genome Sequencing of Bacteriophages LAh1–LAh10

Illumina sequencing revealed novel and diverse genomes with several displaying a similar size of approximately 42,000 bp (LAh1–LAh5). While the genomes of LAh1–LAh5 were the most similar to each other, specific differences were seen, and these resulted in non-synonymous amino acid changes (differences in their genomes and amino acid sequences are highlighted in Table 3). Larger genomes were found in LAh7 (61,426 bp), LAh8 (97,408 bp), LAh9 (97,988 bp), and LAh6 (101,437 bp). LAh10 had the largest genome (260,310 bp) which is the also the largest reported to date against A. hydrophila. The genomes for LAh1–LAh10 were annotated and submitted to GenBank with accession numbers shown in Table 2. All bacteriophages had their genomes in a linear topology except LAh6 which had a circularly permuted genome. The number of ORFs varied with the genome size and ranged from 45 to 227 (Table 2). The GC% content ranged from 42.2% in LAh8 to 61.9% in LAh7. While no bacteriophage showed presence of tmRNA in their genomes, tRNAs were present in 4/10 of the bacteriophages (Table 2). The number or type of tRNAs were not associated with genome size. LAh6 and LAh8 had the highest number of tRNAs at 21 each, followed by LAh9 with 18 tRNAs and LAh10 with 4 tRNAs. Therefore, the bacteriophages with a lower GC% content had a higher number of tRNAs (Table 2). Bacteriophages LAh1–LAh5, and LAh7 did not have any tRNAs in their genomes. None of the bacteriophages isolated in this study had genes coding for putative CRISPR sequences, ARGs, toxins or chromosome integration genes in their genomes.

TABLE 3.

Differences in the genomes of bacteriophages LAh2–LAh5 compared to LAh1.

| Bacteriophage | Nucleotide change | Position | Non-synonymous amino acid change | Putative protein |

| LAh2; LAh4 | C > A | 1939 | Z > K | Scaffolding protein |

| LAh5 | A > G | 8203 | R > G | Hypothetical |

| LAh5 | G > C | 8205 | R > G | Hypothetical |

| LAh5 | Deletion (18 bp) | 8207..8224 | R; P; S; R; TGA (STOP); S | Hypothetical |

| LAh4 | G > A | 14009 | A > T | Tail fiber |

| LAh2; LAh4 | A > G | 15068 | N > D | Tail fiber |

| LAh3; LAh5 | A > G | 15075 | C > Y | Tail fiber |

| LAh2 | Insertion 4 bp | 33001..33006 | I and M (START) | DNA polymerase |

Bacteriophage Phylogeny and Host Specificity

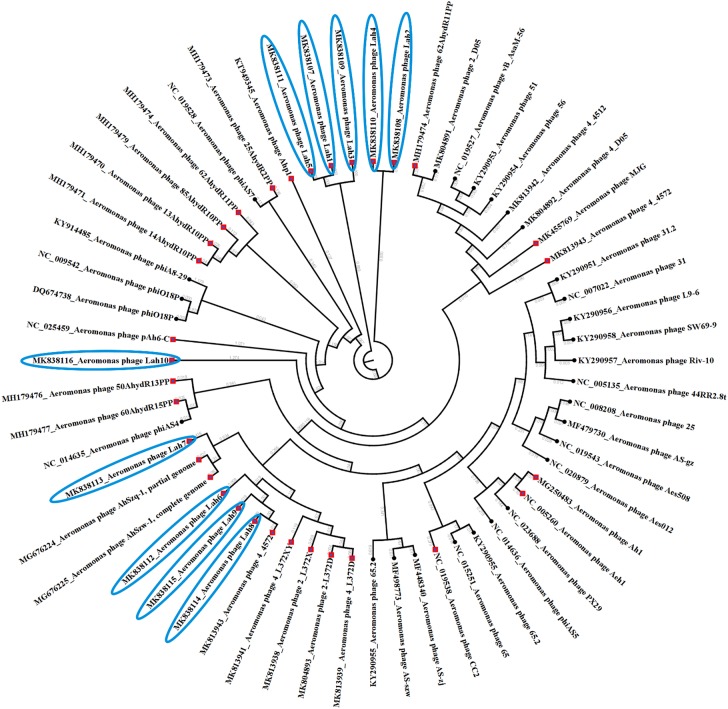

Prior to this study there were 30 reported bacteriophages against Aeromonas spp. including eight against A. hydrophila which have had their genome completely sequenced. The 10 bacteriophages reported here are the first lytic bacteriophages to be isolated against clinical strains of A. hydrophila. The complete genome sequences of the previously isolated bacteriophages against Aeromonas spp. sourced from GenBank and those from this study were compared. Figure 4 reveals the clustering of bacteriophages against clinical strains of A. hydrophila forming two clusters among other bacteriophages isolated using A. hydrophila strains from the environment but further away from those against other Aeromonas species.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing genetic relatedness of bacteriophages against Aeromonas species. All bacteriophages against A. hydrophila are indicated by red diamond nodes including those isolated in this study using clinical strains of A. hydrophila which have been highlighted in blue.

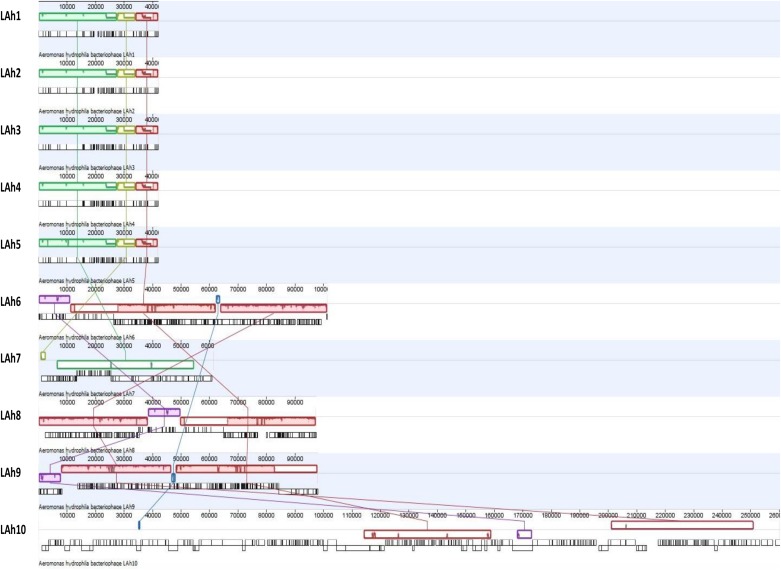

These differences among the isolated bacteriophage genomes were further analyzed by Mauve whole genome alignment of LAh1–LAh10 (Figure 5). The differences in the bacteriophage cluster of LAh1–LAh5 is detailed in Table 3 to highlight functional differences between these bacteriophages. For the cluster of bacteriophages LAh6, LAh8, and LAh9, the Mauve alignment showed the presence of a genetic segment (Blue colored colinear block in Figure 5) in the region of the putative tail fiber genes of bacteriophages that possibly contributed to their differences in host range. While similar in their genomes, LAh6 and LAh8 are able to lyse A. hydrophila strain AHB0139 that LAh9 is not (Table 2). The genome alignments show close homology between LAh1 and LAh5, and a diversity of nucleotide sequence between genomes of LAh7 and LAh10.

FIGURE 5.

Whole genome alignment of LAh1–LAh10 from top to bottom showing similarities and differences between genomes. Each colored colinear block represents a conserved region across the genomes, and these are connected by colored matching lines to trace homology between genomes. Colinear blocks that are offset represent regions that are expressed in the opposite orientation. The uncolored gaps between and within the colinear blocks represent differences between genomes or differences within conserved regions across genomes. The origin of individual ORFs is represented by vertical black lines below the colinear blocks (detailed annotation and putative functionality of each ORF can be accessed through GenBank with accession numbers provided in Table 2). LAh1–LAh5 share all their conserved regions (represented by green, yellow, and red blocks) with differences indicated by nicks and gaps within those blocks. Two of the three colinear blocks from LAh1–LAh5 are shared with LAh7 (green and yellow) and one (red) with all the other bacteriophage genomes (LAh6, LAh8, LAh9, and LAh10). LAh6, LAh8, and LAh9 share homology in three blocks (red, pink, and purple), while LAh6 and LAh9 share a fourth region (blue) which is also found in LAh10 but not LAh8. The purple block is conserved between LAh6, LAh8, LAh9, and LAh10.

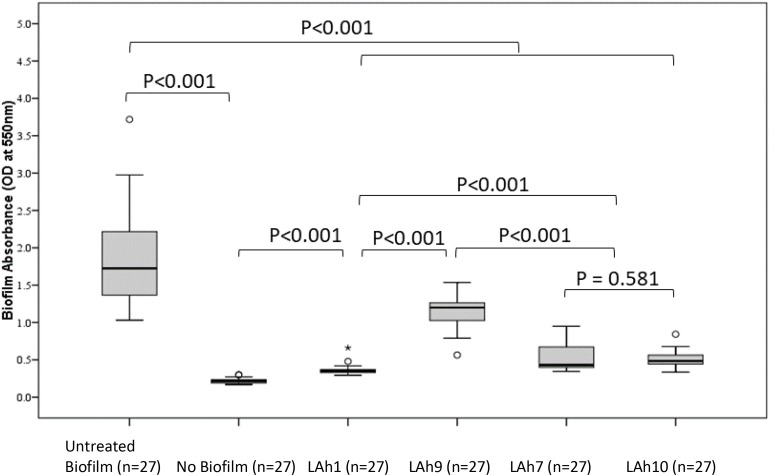

Capacity of LAh1–LAh10 to Disrupt Aeromonas hydrophila Biofilms in vitro

The capacity to disrupt A. hydrophila biofilms was analyzed quantitatively by evaluating the biofilm mass remaining after bacteriophage treatment and estimating the viability of the remnant biofilm. A representative bacteriophage from each morphological group was analyzed for capacity to disrupt biofilm. LAh1 was used as an example of icosahedral Podoviridae, LAh9 for the elongated Podoviridae, LAh7, a Siphoviridae, and LAh10 a Myoviridae. All biofilm experiments were performed using A. hydrophila bacterial strain AHB0116 that was lysed by all bacteriophages isolated here except for LAh1, in which case the host AHB0147 was used. In all cases, the biofilm mass was significantly reduced in bacteriophage treated compared to non-treated groups (p < 0.001). The untreated biofilm had a median (IQR) absorbance at OD550nm of 1.73 (0.86) whilst the largest value for the remnant biofilm after bacteriophage treatment was 1.20 (0.27), p < 0.001 (following treatment with LAh9). Treatment with LAh1 resulted in the lowest absorbance for the remnant biofilm [median (IQR) at OD550nm of 0.35 (0.04)], significantly lower (p < 0.001) than those treated with all the other bacteriophages. LAh7 and LAh10 had statistically similar (p = 0.58) remaining biofilm with absorbance of median (IQR) at OD550nm of 0.43 (0.29) and 0.48 (0.13), respectively (Figure 6). Of the bacteriophages tested on the A. hydrophila biofilms, those with higher GC% content and lower numbers of tRNAs [LAh1 (59.30%; 0), LAh7 (61.90%; 0), and LAh10 (47.50%; 4)] showed significantly greater capacity to degrade biofilms (p < 0.001) than that with lower GC% content and higher numbers of tRNAs [LAh9 (42.40%; 18)] (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Aeromonas hydrophila biofilm absorbance measurements after treatment with bacteriophages LAh1, LAh7, LAh9, and LAh10. Bacteriophages LAh7, LAh9, and LAh10 were tested on A. hydrophila strain AHB0116 biofilm whilst LAh1 was tested on biofilm formed by AHB0147. Bacteriophages with higher GC% content and lower numbers of tRNAs [LAh1 (59.30%; 0), LAh7 (61.90%; 0), and LAh10 (47.50%; 4)] showed significantly greater capacity to degrade biofilms (p < 0.001) than that with lower GC% content and higher numbers of tRNAs [LAh9 (42.40%; 18)]. * Is an extreme outlier.

Viability of Biofilm Treated With Bacteriophages

The viability of the biofilm mass was investigated using SYBR Gold® and PI live/dead staining. Figure 7 shows cells fluorescing green (whole population of cells making up the biofilm) and red (dead, membrane-compromised cells). The icosahedral Podoviridae Bacteriophage LAh1 on host strain AHB0147 was used in the biofilm viability experiments. Figure 7 shows untreated biofilm with a sparse population of membrane-compromised cells (Figure 7B1) compared to a dense total population (Figure 7B2). This indicated that cell population in the untreated biofilm was comprised of mostly membrane-intact cells. This was in contrast to the biofilms treated with bacteriophage (Figures 7A1,A2) in which the density was comparable between total population and membrane-compromised cells implying the cell population was mostly dead. In the bacteriophage treated biofilm, the total population and dead cells were both sparse. Treatment with heat inactivated (autoclaved) bacteriophage did not affect biofilm growth, indicating that Aeromonas biofilm disruption was the result of bacteriophage particles, and not other material in the preparation.

FIGURE 7.

Live/dead staining of A. hydrophila biofilm using propidium Iodide (PI) and SYBR gold®. (A1,A2) show untreated A. hydrophila biofilm on a glass slide. (A1) PI stained (dead) cells and (A2) cells stained with SYBR gold® (total population of cells). (B1,B2) A. hydrophila biofilm on a glass slide treated with bacteriophage LAh1 for 60 min. (B1) PI stained (dead) cells and (B2) cells stained with SYBR gold® (total population of cells).

Discussion

Increasing global temperatures have allowed a number of micro-organisms to emerge as potential causes of disease (Aguirre and Tabor, 2008). A. hydrophila is one bacterial species benefiting from global warming with more clinical strains emerging (Azzopardi et al., 2011). These bacteria are usually resistant to first and second line antibiotic therapy involving beta-lactam drugs and third generation cephalosporins via mechanisms such as resistance genes and biofilm formation (Janda and Abbott, 2010). Bacteriophages, which have been suggested as an alternative to antibiotics, have been isolated against environmental and fish pathogen strains of A. hydrophila (Chow and Rouf, 1983; Merino et al., 1990a, b; Gibb and Edgell, 2007; Shen et al., 2012; Jun et al., 2013; Anand et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Le et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2019; Kazimierczak et al., 2019). The host range of these bacteriophages, however, was not reported to extend to clinical strains. The current study is the first to report the isolation and characterization of bacteriophages lytic against clinical strains of A. hydrophila, all of which carry intrinsic antibiotic resistance markers. These bacteriophages (LAh1–LAh10) displayed diversity in their morphology and genomic composition. The genomes of LAh1–LAh5 were the most similar to each other, yet specific differences were seen, and these resulted in non-synonymous amino acid changes. These changes may have contributed to the differences in growth kinetics observed between LAh1 and LAh5. Phylogenetic comparison between LAh1 and LAh10 and other Aeromonas bacteriophages revealed that LAh1–LAh10 clustered separately to those lytic for environmental strains of A. hydrophila and to bacteriophages against other species of Aeromonas.

Aeromonas hydrophila has been shown to thrive in water storage tanks and swimming pools as biofilms (Julia Manresa et al., 2009; Chubaka et al., 2018). The persistence of A. hydrophila in such environments has been implicated in several diseases such as diarrhea, sepsis and necrotizing fasciitis (Janda and Abbott, 2010). Bacteria growing in biofilm communities are more difficult to control than planktonic ones and A. hydrophila in particular is resistant to treatment with antibiotics and disinfectants such as chlorine (Donlan and Costerton, 2002; Janda and Abbott, 2010). Bacteriophages, which have been shown to be safe in clinical applications (Malik et al., 2017; Dedrick et al., 2019; Nir-Paz et al., 2019; Schmidt, 2019) may provide a useful solution to controlling this bacterium in a changing climate. The bacteriophages isolated and tested in this study were able to significantly reduce the A. hydrophila biofilm mass after 24 h of treatment. While these bacteriophages as well as others are active against biofilms (Hansen et al., 2019; Saha and Mukherjee, 2019), the factors associated with their efficacy have not been fully elucidated. The bacteriophages isolated in this study were diverse in morphology, genome content and organization. Their Podoviridae, Siphoviridae, or Myoviridae morphology was not associated with their capacity to disrupt a biofilm. The size of the genome and physical size of the bacteriophages was also not associated with their biofilm disruptive capabilities. However, bacteriophages in this study with a low GC% content and with a higher number of tRNAs had a lower biofilm disruptive efficacy. While we did not assess the GC% content of the A. hydrophila strains used for the biofilm assays here, the GC% of A. hydrophila published genomes ranged from 60.2 to 61.3% (Chan et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2015a, b; Forn-Cuni et al., 2016a, b; Moura et al., 2017). Assuming our bacterial strains had similar content, then it would appear that bacteriophages in our study which matched more closely the GC% of the bacteria were significantly more successful in degrading biofilms. Bacteria growing in biofilms will slow down their metabolism (Donlan and Costerton, 2002), and this factor may have a greater impact on those bacteriophages that carry their own tRNAs. It is important, however, to highlight that the sample of bacteriophages we assayed in our study was small, and the number of those with and without tRNAs was even smaller. Therefore, more concrete experimental data and extensive sampling is required before definitive conclusions can be drawn from such observations.

While others report that bacteriophage GC% content was related to GC% content of host bacteria (Xia and Yuen, 2005) and that presence of tRNAs was characteristic of more virulent bacteriophages (Bailly-Bechet et al., 2007), in our study there was no apparent relationship between host range and GC% content or number of tRNAs present in bacteriophage genomes. In the bacteriophages isolated here, those with lower GC% content had higher numbers of tRNAs, similar to findings in a study of bacteriophages against Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. Salmonicida (Vincent et al., 2017). This may not be surprising if we assume that the genomes of A. hydrophila used here have a similar GC% content to those previously published [60.2–61.3% (Chan et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2015a, b; Forn-Cuni et al., 2016a, b; Moura et al., 2017)] and that while bacteriophage genomes evolve to match the GC% of their hosts (Xia and Yuen, 2005), those whose GC content is lower may require tRNAs to complement their biochemical requirements. Finally, certain bacteriophages may code for and transfer ARGs in bacteria through transduction (Gunathilaka et al., 2017; Brown-Jaque et al., 2018; Larranaga et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). None of the bacteriophages isolated here were found to code for these, which may be a favorable feature if they were to be used in environmental or clinical settings.

Conclusion

We report here a diverse range of novel bacteriophages, LAh1–LAh10, which are the first shown to be active against clinical strains of A. hydrophila. While these bacteria may survive decontaminating efforts in water by quorum sensing and forming biofilms, bacteriophages offer the potential of an alternative to control their growth in the environment, as well as following human infection. Functionally, the bacteriophages tested here were capable of A. hydrophila biofilm disruption.

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequences have been submitted to NCBI GenBank with accession numbers: MK838107, MK838108, MK838109, MK838110, MK838111, MK838112, MK838113, MK838114, MK838115, and MK838116.

Author Contributions

JT, HC, and MK: conceptualization. MK, HK, and HC: data collection. MK and TB: genomics. MK, LS, and PL: electron microscope imaging and biofilm. MK, ML, and JT: data analysis. JT, HC, and SP: supervision. MK and JT: writing – original draft. MK, TB, HC, and JT: writing – review and editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the La Trobe University Bio-imaging Facility (La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science) for the TEM images.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00194/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aguirre A. A., Tabor G. M. (2008). Global factors driving emerging infectious diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1149 1–3. 10.1196/annals.1428.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Huygens F., Goonetilleke A., Gardner T. (2008). Real-time Pcr detection of pathogenic microorganisms in roof-harvested rainwater in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 5490–5496. 10.1128/AEM.00331-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand T., Vaid R. K., Bera B., Singh J., Barua S., Virmani N., et al. (2016). Isolation of a lytic bacteriophage against virulent Aeromonas hydrophila from an organized equine farm. J. Basic Microbiol. 56 432–437. 10.1002/jobm.201500318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi E. A., Azzopardi S. M., Boyce D. E., Dickson W. A. (2011). Emerging gram-negative infections in burn wounds. J. Burn. Care Res. 32 570–576. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31822ac7e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M., Cheng Y. H., Sun X. Q., Wang Z. Y., Wang Y. X., Cui X. L., et al. (2019). Nine novel phages from a plateau lake in southwest china: insights into aeromonas phage diversity. Viruses 11:E615. 10.3390/v11070615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly-Bechet M., Vergassola M., Rocha E. (2007). Causes for the intriguing presence of trnas in phages. Genome Res. 17 1486–1495. 10.1101/gr.6649807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra P., Mathur P., Misra M. C. (2016). Aeromonas spp.: an emerging nosocomial pathogen. J. Lab. Physicians 8 1–4. 10.4103/0974-2727.176234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilstein F., Dreiseikelmann B. (2008). Temperate bacteriophage PhiO18P from an Aeromonas media isolate: characterization and complete genome sequence. Virology 373 25–29. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Jaque M., Calero-Caceres W., Espinal P., Rodriguez-Navarro J., Miro E., Gonzalez-Lopez J. J., et al. (2018). Antibiotic resistance genes in phage particles isolated from human faeces and induced from clinical bacterial isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51 434–442. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke V., Robinson J., Gracey M., Peterson D., Meyer N., Haley V. (1984a). Isolation of Aeromonas spp. from an unchlorinated domestic water supply. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48 367–370. 10.1128/aem.48.2.367-370.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke V., Robinson J., Gracey M., Peterson D., Partridge K. (1984b). Isolation of Aeromonas hydrophila from a metropolitan water supply: seasonal correlation with clinical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48 361–366. 10.1128/aem.48.2.361-366.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Li S., Wang D., Zhao J., Xu L., Liu H., et al. (2019). Genomic characterization of a novel virulent phage infecting the Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Virus Res. 273:197764. 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.197764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. G., Tan W. S., Chang C. Y., Yin W. F., Mumahad Yunos N. Y. (2015). Genome sequence analysis reveals evidence of quorum-sensing genes present in aeromonas hydrophila strain M062, Isolated from Freshwater. Genome Announc. 3:e00100-15. 10.1128/genomeA.00100-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow M. S., Rouf M. A. (1983). Isolation and partial characterization of two Aeromonas hydrophila bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45 1670–1676. 10.1128/aem.45.5.1670-1676.1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury M. A., Yamanaka H., Miyoshi S., Shinoda S. (1990). Ecology of mesophilic Aeromonas spp. in aquatic environments of a temperate region and relationship with some biotic and abiotic environmental parameters. Zentralbl Hyg Umweltmed 190 344–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubaka C. E., Whiley H., Edwards J. W., Ross K. E. (2018). A review of roof harvested rainwater in Australia. J. Environ. Public Health 2018 6471324. 10.1155/2018/6471324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaplewski L., Bax R., Clokie M., Dawson M., Fairhead H., Fischetti V. A., et al. (2016). Alternatives to antibiotics-a pipeline portfolio review. Lancet Infect Dis. 16 239–251. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00466-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling A. C., Mau B., Blattner F. R., Perna N. T. (2004). Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14 1394–1403. 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrick R. M., Guerrero-Bustamante C. A., Garlena R. A., Russell D. A., Ford K., Harris K., et al. (2019). Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 25 730–733. 10.1038/s41591-019-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNicola E., Aburizaiza O. S., Siddique A., Khwaja H., Carpenter D. O. (2015). Climate change and water scarcity: the case of saudi Arabia. Ann. Glob. Health 81 342–353. 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan R. M., Costerton J. W. (2002). Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15 167–193. 10.1128/cmr.15.2.167-193.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden M., Munro R. (1989). Aeromonas septicemia: relationship of species and clinical features. Pathology 21 111–114. 10.3109/00313028909059546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziewit L., Radlinska M. (2016). Two novel temperate bacteriophages co-existing in Aeromonas sp. Arm81 - characterization of their genomes, proteomes and Dna methyltransferases. J. Gen. Virol. 97 2008–2022. 10.1099/jgv.0.000504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forn-Cuni G., Tomas J. M., Merino S. (2016a). Genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila strain Ah-3 (Serotype O34). Genome Announc. 4:e00919-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forn-Cuni G., Tomas J. M., Merino S. (2016b). Whole-genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila strain Ah-1 (Serotype O11). Genome Announc. 4:e00920-16. 10.1128/genomeA.00920-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb E. A., Edgell D. R. (2007). Multiple controls regulate the expression of mobE, an Hnh homing endonuclease gene embedded within a ribonucleotide reductase gene of phage Aeh1. J. Bacteriol. 189 4648–4661. 10.1128/jb.00321-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golkar Z., Bagasra O., Pace D. G. (2014). Bacteriophage therapy: a potential solution for the antibiotic resistance crisis. J. Infect Dev. Ctries 8 129–136. 10.3855/jidc.3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. (2007). Crisprfinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 W52–W57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunathilaka G. U., Tahlan V., Mafiz A., Polur M., Zhang Y. (2017). Phages in urban wastewater have the potential to disseminate antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 50 678–683. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M. F., Svenningsen S. L., Røder H. L., Middelboe M., Burmølle M. (2019). Big Impact of the Tiny: bacteriophage–bacteria Interactions in Biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 27 739–752. 10.1016/j.tim.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igbinosa I. H., Igumbor E. U., Aghdasi F., Tom M., Okoh A. I. (2012). Emerging Aeromonas species infections and their significance in public health. Sci. World J. 2012:625023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda J. M., Abbott S. L. (2010). The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 35–73. 10.1128/CMR.00039-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia B., Raphenya A. R., Alcock B., Waglechner N., Guo P., Tsang K. K., et al. (2017). Card 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D566–D573. 10.1093/nar/gkw1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julia Manresa M., Vicente Villa A., Gene Giralt A., Gonzalez-Ensenat M. A. (2009). Aeromonas hydrophila folliculitis associated with an inflatable swimming pool: mimicking Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Pediatr. Dermatol. 26 601–603. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J. W., Kim J. H., Shin S. P., Han J. E., Chai J. Y., Park S. C. (2013). Protective effects of the Aeromonas phages pAh1-C and pAh6-C against mass mortality of the cyprinid loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) caused by Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquaculture 416 289–295. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.09.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazimierczak J., Wojcik E. A., Witaszewska J., Guzinski A., Gorecka E., Stanczyk M., et al. (2019). Complete genome sequences of Aeromonas and Pseudomonas phages as a supportive tool for development of antibacterial treatment in aquaculture. Virol. J. 16:4. 10.1186/s12985-018-1113-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larranaga O., Brown-Jaque M., Quiros P., Gomez-Gomez C., Blanch A. R., Rodriguez-Rubio L., et al. (2018). Phage particles harboring antibiotic resistance genes in fresh-cut vegetables and agricultural soil. Environ. Int. 115 133–141. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett D., Canback B. (2004). Aragorn, a program to detect trna genes and tmrna genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 11–16. 10.1093/nar/gkh152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T. S., Nguyen T. H., Vo H. P., Doan V. C., Nguyen H. L., Tran M. T., et al. (2018). Protective effects of Bacteriophages against Aeromonas hydrophila species causing motile Aeromonas septicemia (Mas) in striped catfish. Antibiotics 7 E16. 10.3390/antibiotics7010016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M., Chan P. P. (2016). trnascan-Se On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer Rna genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W54–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkw413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik D. J., Sokolov I. J., Vinner G. K., Mancuso F., Cinquerrui S., Vladisavljevic G. T., et al. (2017). Formulation, stabilisation and encapsulation of bacteriophage for phage therapy. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 249 100–133. 10.1016/j.cis.2017.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos D., Anguita J., Naharro G., Paniagua C. (1993). Influence of growth temperature on the production of extracellular virulence factors and pathogenicity of environmental and human strains of Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 74 111–118. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino S., Camprubi S., Tomas J. M. (1990a). Isolation and characterization of bacteriophage Pm2 from Aeromonas hydrophila. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 56 239–244. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino S., Camprubi S., Tomas J. M. (1990b). Isolation and characterization of bacteriophage Pm3 from Aeromonas hydrophila the bacterial receptor for which is the monopolar flagellum. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 57 277–282. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt J. H., Kadouri D. E., O’toole G. A. (2005). Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 1:Unit 1B.1. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount D. W. (2007). Using the basic local alignment search tool (Blast). Csh. Protoc. 2007:dbto17. 10.1101/pdb.top17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura Q., Fernandes M. R., Cerdeira L., Santos A. C. M., De Souza T. A., Ienne S., et al. (2017). Draft genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila St508 strain carrying rmtD and blactx-M-131 isolated from a bloodstream infection. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 10 289–290. 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyts K., Huys G., Uyttendaele M., Swings J., Debevere J. (2000). Incidence and identification of mesophilic Aeromonas spp. from retail foods. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31 359–363. 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir-Paz R., Gelman D., Khouri A., Sisson B. M., Fackler J., Alkalay-Oren S., et al. (2019). Successful treatment of antibiotic resistant poly-microbial bone infection with bacteriophages and antibiotics combination. Clin. Infect Dis. 69 2015–2018. 10.1093/cid/ciz222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard B., Goullet P. (1987). Seasonal prevalence of nosocomial Aeromonas hydrophila infection related to aeromonas in hospital water. J. Hosp. Infect. 10 152–155. 10.1016/0195-6701(87)90141-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen-Ivey C. R., Figueras M. J., Mcgarey D., Liles M. R. (2016). Virulence Factors of Aeromonas hydrophila: in the wake of reclassification. Front. Microbiol. 7:1337. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha D., Mukherjee R. (2019). Ameliorating the antimicrobial resistance crisis: phage therapy. Iubmb. Life 71 781–790. 10.1002/iub.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C. (2019). Phage therapy’s latest makeover. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 581–586. 10.1038/s41587-019-0133-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C. J., Liu Y. J., Lu C. P. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila Phage Cc2. J. Virol. 86:10900. 10.1128/JVI.01882-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair H. A., Heney C., Sidjabat H. E., George N. M., Bergh H., Anuj S. N., et al. (2016). Genotypic and phenotypic identification of Aeromonas species and CphA-mediated carbapenem resistance in Queensland, Australia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect Dis. 85 98–101. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talagrand-Reboul E., Jumas-Bilak E., Lamy B. (2017). The social life of aeromonas through biofilm and quorum sensing systems. Front. Microbiol. 8:37. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. S., Yin W. F., Chan K. G. (2015a). Insights into the quorum-sensing activity in Aeromonas hydrophila strain M013 as revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Genome Announc. 3:e01372-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01372-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. S., Yin W. F., Chang C. Y., Chan K. G. (2015b). Whole-genome sequencing analysis of quorum-sensing Aeromonas hydrophila Strain M023 from freshwater. Genome Announc. 3:e01548-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01548-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vally H., Whittle A., Cameron S., Dowse G. K., Watson T. (2004). Outbreak of Aeromonas hydrophila wound infections associated with mud football. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38 1084–1089. 10.1086/382876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela A. R., Nunes O. C., Manaia C. M. (2016). Quinolone resistant Aeromonas spp. as carriers and potential tracers of acquired antibiotic resistance in hospital and municipal wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 542 665–671. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A. T., Paquet V. E., Bernatchez A., Tremblay D. M., Moineau S., Charette S. J. (2017). Characterization and diversity of phages infecting Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Sci. Rep. 7:7054. 10.1038/s41598-017-07401-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. B., Lin N. T., Tseng Y. H., Weng S. F. (2016). Genomic characterization of the novel Aeromonas hydrophila phage ahp1 suggests the derivation of a new subgroup from phikmv-like family. PloS One 11:e0162060. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Zeng X., Yang Q., Yang C. (2018). Identification of a bacteriophage from an environmental multidrug-resistant E. coli isolate and its function in horizontal transfer of Args. Sci. Total Environ. 639 617–623. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation [WHO] (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance 2014. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., Yuen K. Y. (2005). Differential selection and mutation between dsdna and ssdna phages shape the evolution of their genomic At percentage. Bmc Genet. 6:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. B., Kaur R., Lim S., Wang X. H., Leung K. Y. (2007). Characterization of extracellular proteins produced by Aeromonas hydrophila Ah-1. Proteomics 7 436–449. 10.1002/pmic.200600396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chen L., Liu Q., Zhou Y., Yang J., Deng D., et al. (2018). Characterization and genomic analyses of Aeromonas hydrophila phages AhSzq-1 and AhSzw-1, isolates representing new species within the T5virus genus. Arch. Virol. 163 1985–1988. 10.1007/s00705-018-3805-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequences have been submitted to NCBI GenBank with accession numbers: MK838107, MK838108, MK838109, MK838110, MK838111, MK838112, MK838113, MK838114, MK838115, and MK838116.