Melioidosis is an infectious disease with a high mortality rate responsible for community-acquired sepsis in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. The causative agent of this disease is Burkholderia pseudomallei, a Gram-negative bacterium that resides in soil and contaminated natural water. After entering into host cells, the bacteria escape into the cytoplasm, which has numerous cytosolic sensors, including the noncanonical inflammatory caspases.

KEYWORDS: Burkholderia pseudomallei, caspase-4, human lung epithelial cell (A549), melioidosis, noncanonical inflammasome

ABSTRACT

Melioidosis is an infectious disease with a high mortality rate responsible for community-acquired sepsis in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. The causative agent of this disease is Burkholderia pseudomallei, a Gram-negative bacterium that resides in soil and contaminated natural water. After entering into host cells, the bacteria escape into the cytoplasm, which has numerous cytosolic sensors, including the noncanonical inflammatory caspases. Although the noncanonical inflammasome (caspase-11) has been investigated in a murine model of B. pseudomallei infection, its role in humans, particularly in lung epithelial cells, remains unknown. We, therefore, investigated the function of caspase-4 (ortholog of murine caspase-11) in intracellular killing of B. pseudomallei. The results showed that B. pseudomallei induced caspase-4 activation at 12 h postinfection in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. The number of intracellular B. pseudomallei bacteria was increased in the absence of caspase-4, suggesting its function in intracellular bacterial restriction. In contrast, a high level of caspase-4 processing was observed when cells were infected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) mutant B. pseudomallei. The enhanced bacterial clearance in LPS-mutant-infected cells is also correlated with a higher degree of caspase-4 activation. These results highlight the susceptibility of the LPS mutant to caspase-4-mediated intracellular bacterial killing.

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative intracellular bacterium causing melioidosis, a life-threatening disease with indistinguishable symptoms from other bacterial infections (1). According to the WHO report in 2014, melioidosis is one of the major neglected bacterial infections accounting for sepsis and bacteremic pneumonia in the Southeast Asia region, particularly in Northeast Thailand (2, 3). In the predicted model of global melioidosis burden in 2018, there are approximately 165,000 melioidosis cases and 89,000 deaths per year (4). Although skin inoculation and contaminated water ingestion are the main routes of infection, numerous studies suggested inhalation as the primary mode of infection during the extreme weather period (5, 6). Melioidosis has a wide range and nonspecific clinical manifestations, which can delay the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. The lung is the commonly affected organ since half of melioidosis patients suffer from respiratory infection symptoms, including pneumonia, pulmonary abscess, and pleuritis (1). Because of the multidrug resistance feature of the bacterium and the lack of vaccine for melioidosis, understanding the host-microbe interactions at the cellular level is critical for the treatment of B. pseudomallei (7).

Innate immunity involves the first-line host defense that plays a crucial role during the early phase of microbial infection. The innate immune cells possess pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which can detect conserved microbial molecules, including bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagellin, and peptidoglycan. PRRs are expressed in phagocytic innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as in nonphagocytic cells, such as epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts (8). Inflammatory caspases (human caspase-1, -4, -5, and murine caspase-1, -11, -12) are a subgroup of the well-known apoptosis-inducing cysteine protease families. Unlike other caspases, inflammatory caspases are accountable for regulating inflammatory responses to restrict pathogen infection (9). Among the inflammatory caspases, caspase-1 activation pathway is extensively characterized and described as the result of “canonical inflammasome” assembly. The canonical inflammasomes, which are composed of the cytosolic Nod-like receptors (NLRs), adaptor proteins, and caspase-1, are responsible for mature proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 release and a distinct type of inflammatory cell death called pyroptosis (10, 11). However, a recent study has suggested a role of the alternative inflammatory caspases (mouse caspase-11 and human caspase-4/-5), the “noncanonical inflammasome,” as innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS (12). Upon direct binding to the cytosolic LPS, the noncanonical inflammasome undergoes autoproteolysis maturation and triggers pyroptosis to eliminate the intracellular replication niches of the pathogens. Besides the pyroptotic cell death, a new study has suggested an alternative bacterial restriction mechanism resulting from the cross talk between the noncanonical inflammasome activation and cellular trafficking during Gram-negative bacterial infections (13). The noncanonical inflammasome has shown a protective role to many Gram-negative bacterial infections, including those of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Legionella pneumophila, and Burkholderia spp. (14–17).

B. pseudomallei invades and survives intracellularly in both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells (18–20). After escape from the endocytic vacuole, B. pseudomallei remains in the cytosol and replicates there. casp11−/− mice were highly susceptible to Burkholderia thailandensis and B. pseudomallei infections and showed a low survival rate, indicating the critical role of the noncanonical inflammasome in host protection (16, 17). The study of B. thailandensis-infected nonhematopoietic cells also demonstrated that pyroptosis in mouse lung epithelial cells was solely dependent on caspase-11 activity (16). Although human caspase-4 is generally considered the structural as well as functional homologue of murine caspase-11, differences in their expression pattern and function toward a particular infection have been demonstrated in the past (9, 21). Unlike caspase-11, which requires gamma interferon (IFN-γ) to prime its expression, caspase-4 is constitutively and abundantly expressed in both myeloid and nonmyeloid cell lineages, including that of epithelial cells (14, 22). Caspase-4 is described as an essential player in mucosal immunity against many enteric bacterial pathogens by initiating epithelial cell shedding and pyroptosis during Shigella flexneri, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and S. Typhimurium infections (14, 23). The role of inflammasome pathways in B. pseudomallei infection has been investigated only in mouse macrophages. Although lung epithelial cells are the primary responder of inhalational B. pseudomallei infection, the role of caspase-4 is still unknown. A549 cells are a well-known model for human type II alveolar epithelial cells (ACEII), which is widely used across different fields of research, including drug delivery and infectious diseases. In the present study, we examined the role of caspase-4 in B. pseudomallei-infected A549 cells. These results show the critical role of caspase-4 in restricting intracellular B. pseudomallei.

RESULTS

B. pseudomallei activates caspase-4 in infected human alveolar epithelial A549 cells.

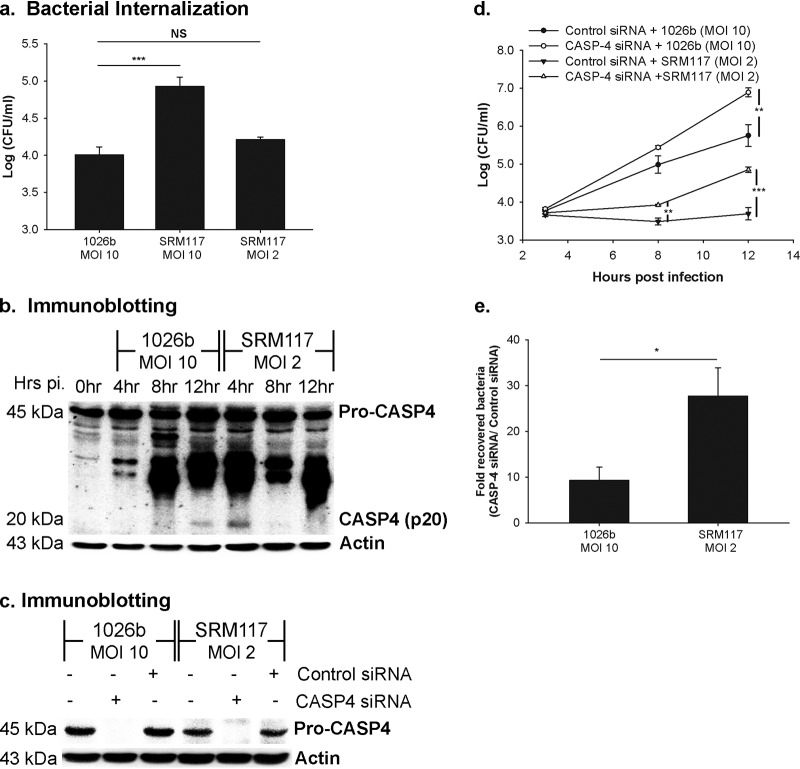

Human lung alveolar A549 cells were also reported to provide the replication niche for B. pseudomallei before triggering cell death at 12 h postinfection (24). To investigate the function of caspase-4 activation to intracellular B. pseudomallei, we infected A549 cells with B. pseudomallei and analyzed its role up to 12 h postinfection. As shown in Fig. 1a, caspase-4 mRNA was constitutively expressed and slightly upregulated in response to B. pseudomallei infection. Caspase-4 is produced as an inactive form (procaspase-4; 45 kDa) and requires autoproteolytic processing to become the p20 active form. We further investigated the caspase-4 activation pattern and determined the level of the p20 caspase-4 active form by immunoblotting. The p20 caspase-4 was observed at 12 h postinfection (Fig. 1b). To demonstrate caspase-4 activation in A549 cells, intracellular E. coli LPS, which has been known to activate caspase-4, was used as a positive control (Fig. 1b). Altogether, our data suggest that the caspase-4 activation was spontaneously initiated in B. pseudomallei-infected A549 cells.

FIG 1.

B. pseudomallei induces caspase-4 activation in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. A549 cells were infected with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 10. One microgram of E. coli LPS was electroporated into A549 cells as a positive control. The electroporated samples were collected after 16 h of electroporation. The mRNA expression kinetics and caspase-4 activation were determined using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (a) and immunoblotting (b), respectively. The data represented are the means and standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. The individual experiments were carried out in technical duplicate.

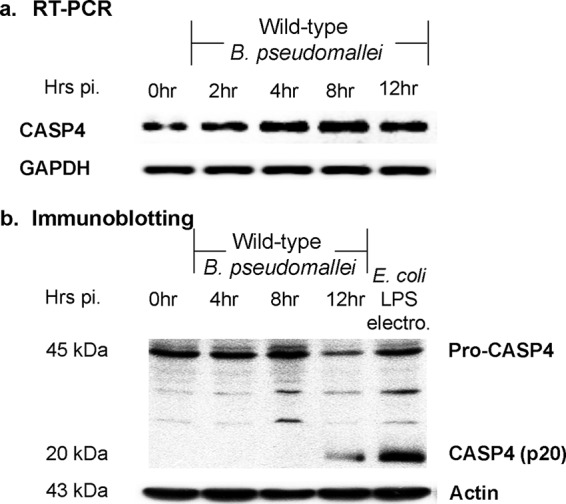

Caspase-4 mediates restriction of intracellular B. pseudomallei.

To determine the role of activated caspase-4 during B. pseudomallei infection, we further examined its role in intracellular bacterial elimination. The alveolar epithelial A549 cells were transfected with specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against caspase-4 at 48 h before B. pseudomallei infection to deplete caspase-4 expression. The depletion efficiency was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2a). The infected caspase-4-depleted cells exhibited a significant increase in intracellular bacterial number when compared to the control siRNA-treated cells after 12 h of infection (Fig. 2b). Our results indicated that caspase-4 activation mediated the bacterial growth inhibition.

FIG 2.

The caspase-4 inflammasome pathway triggers the intracellular killing of B. pseudomallei. A549 cells were transfected with specific siRNAs against caspase-4 before infection with B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 10. (a) The depletion efficiency was confirmed at 12 h postinfection by immunoblotting. (b) The number of intracellular bacteria was determined by antibiotic protection assay. The data represented are the means and standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. The individual experiments were carried out in technical duplicate. ***, P < 0.001.

B. pseudomallei LPS mutant activates caspase-4 earlier than wild-type B. pseudomallei in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells.

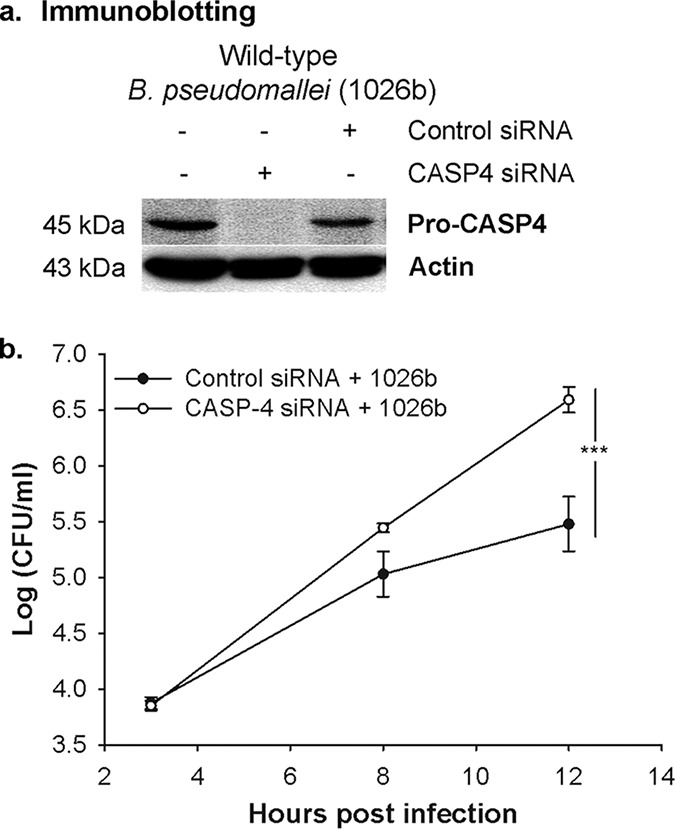

A recent report showed that intracellular LPS plays an essential role in caspase-4 activation (12). Since the previous study demonstrated that the LPS mutant B. pseudomallei (SRM117) is unable to survive and multiply inside mouse macrophages compared to parental strain 1026b (25, 26), we further investigated whether the caspase-4 activation is involved in reduced survival pattern of the LPS mutant. Consistent with the LPS-mutant-infected mouse macrophages, we found that this bacterial strain has a higher bacterial internalization than the wild-type 1026b strain but is incapable of surviving in infected A549 cells (Fig. 3a). The intracellular survival kinetics of the LPS mutant sharply declined at 4 h of infection and remained lower than that of the wild-type bacteria throughout the time course. These data suggested that the human alveolar epithelial cells can suppress the intracellular survival of the LPS mutant. In addition, the caspase-4 processing pattern demonstrated that caspase-4 activation is highly induced at the early time point, as observed at 4 h after infection. The activation level is also consistent with the kinetics of intracellular bacterial survival, as shown by the low number of intracellular bacteria at the same time point. The p20 active form of caspase-4 is markedly decreased at 8 and 12 h postinfection, along with an increase in intracellular bacteria (Fig. 3b). These results suggest a direct correlation between caspase-4 activation and intracellular survival of the bacteria.

FIG 3.

LPS-mutated B. pseudomallei induces a different caspase-4 activation pattern. A549 cells were infected with either wild-type (1026b) or LPS-mutated (SRM117) B. pseudomallei at an MOI of 10. (a) At the indicated time points, the numbers of intracellular bacteria were determined. (b) The activation of caspase-4 in LPS-mutant-infected cells was analyzed by immunoblotting. The data represented are the means and standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. The individual experiments were carried out in technical duplicate.

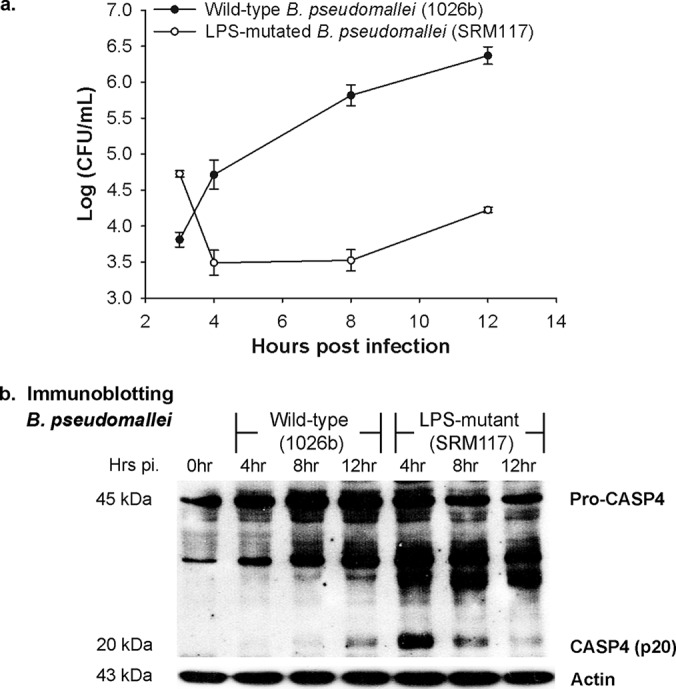

LPS mutant B. pseudomallei is susceptible to caspase-4-mediated intracellular bacterial elimination.

As the LPS-mutant-infected cells showed the higher level of caspase-4 activation during early time points, we further investigated whether the activation pattern is due to an increase in the internalization of LPS mutant bacteria. We therefore normalized the dose of infection of these two strains, as shown in Fig. 4a. The data demonstrated that the internalization of the LPS mutant at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 is comparable to that at an MOI of 10 in the parental B. pseudomallei strain. Both an MOI of 10:1 and an MOI of 2:1 of the LPS mutant infection share similar caspase-4 activation patterns in infected A549 cells. As shown in Fig. 4b, caspase-4 processing is detected at 4 h postinfection and is found to be slowly declined in the later time course in the normalized dose of the LPS mutant (MOI 2:1). We also investigated caspase-4-mediated LPS mutant restriction in infected A549 cells. The results showed that the intracellular growth of the LPS mutant B. pseudomallei is significantly increased in the absence of the noncanonical caspase-4 activation (Fig. 4c and d). To further demonstrate the involvement of LPS mutant in caspase-4-mediated bacterial restriction, viable intracellular bacterial recovery was determined at 12 h postinfection. Fold recovered bacteria were calculated by the CFU ratio between caspase-4-depleted cells and the control siRNA-treated cells. Consistent with caspase-4 activation level, LPS mutant in caspase-4-depleted cells showed significantly higher recovering bacterial efficiency (∼30-fold) than wild-type infected cells (∼10-fold) (Fig. 4e). Altogether, our results suggest that the robust caspase-4 activation in LPS mutant B. pseudomallei tempers intracellular bacterial growth.

FIG 4.

LPS mutant B. pseudomallei is susceptible to the caspase-4-mediated bacterial restriction in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. A549 cells were infected with either the wild type (1026b) at an MOI of 10 or LPS-mutated B. pseudomallei (SRM117) at an MOI of 2 and 10. (a) At 3 h postinfection, the numbers of intracellular bacteria were determined to indicate the bacterial internalization. (b) The activation of caspase-4 in infected cells was analyzed by immunoblotting. A549 cells were transfected with siRNAs against caspase-4 before the infection. (c) Depletion of caspase-4 in LPS-mutant-infected cells was confirmed by immunoblotting at 12 h postinfection. (d) At the same time point, the number of intracellular bacteria was determined by antibiotic protection assay. (e) The recovering efficiency was determined at 12 h postinfection. Fold recovered bacteria were calculated by CFU ratio between caspase-4-depleted cells and the control siRNA-treated cells. The data represented are the means and standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. The individual experiments were carried out in technical duplicate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

A significant number of studies about antibacterial innate immune responses are mainly focused on the myeloid lineage, such as the monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. To counteract the cytosolic invasion of bacteria, the inflammatory caspases (canonical inflammasome caspase-1 and noncanonical inflammasome murine caspase-11/human caspase-4/-5) activate inflammatory responses and cell death (10). B. pseudomallei can adhere, invade, and replicate within the human alveolar epithelial A549 cells before inducing cell death after 12 h postinfection (20, 24, 27–29); therefore, we examined the caspase-4-mediated function during B. pseudomallei infection in A549 cells as a model system equivalent to that of human alveolar epithelial cells.

Murine caspase-11 and human caspase-4 are known as orthologous genes; however, whether their antibacterial functions are similar is still unclear. Our results demonstrated that A549 cells constitutively express caspase-4 during their resting state. Upon encountering B. pseudomallei, caspase-4 expression is modestly upregulated (Fig. 1a). These results are also consistent with previous reports in various cell types, including those of the epithelial lineage (12, 14, 30, 31). In contrast to the mouse lung epithelial cell line (TC-1), which requires tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)/IFN-γ to prime to counteract with Burkholderia spp., infected A549 cells were able to directly upregulate caspase-4 expression without other factors (16, 17, 32). Our data suggest that these noncanonical inflammatory caspase orthologs might regulate differently depending on species.

We further investigated the role of activated caspase-4 in bacterial restriction during B. pseudomallei infection. In caspase-4-depleted A549 cells, the number of intracellular B. pseudomallei bacteria was significantly increased, suggesting that a caspase-4-mediated bacterial restriction mechanism is triggered during B. pseudomallei infection (Fig. 2). This phenomenon is also observed in other Gram-negative bacterial infections. For example, cytosolic S. Typhimurium growth is inhibited in both myeloid and nonmyeloid lineages before the onset of cell death (33).

Although the mechanisms of caspase-4 to restrict intracellular bacteria are still unclear, several studies have highlighted the connection of the noncanonical inflammasome to the modulation of cellular trafficking during infection of intravacuolar bacteria. Murine caspase-11 mediates L. pneumophila restriction by regulating actin polymerization, resulting in the fusion of phagosomes containing bacteria with lysosomes in infected macrophages (13, 34). The noninflammatory bacterial restriction role of caspase-4 is also observed in other Burkholderia spp., such as Burkholderia cenocepacia (32). Whether or not the caspase-4 noncanonical inflammasome associates with the cellular trafficking and phagolysosome fusion in human lung epithelial cells during B. pseudomallei infection needs to be further investigated.

In the present study, we demonstrate that, unlike wild-type B. pseudomallei, the LPS mutant (SRM117) was unable to survive and multiply in the human alveolar epithelial cell line (A549). Furthermore, a correlation between the higher degrees of caspase-4 activation and intracellular killing was also observed in LPS-mutant-infected cells (Fig. 3 and 4). These results may be due to the lack of O antigenic polysaccharide in the LPS mutant, resulting in a shorter LPS structure with exposed core oligosaccharide and lipid A moiety. The length of O polysaccharide antigen (O antigen) on LPS also affects the binding affinity of noncanonical inflammatory caspases. The shorter length of the O antigen on the LPS results in a higher binding affinity, leading to higher oligomerization and activation (12). Moreover, the length of the O antigen also plays a significant role in bacterial infection. For example, a study of Salmonella enterica isolates that lack or have shortened O antigen showed increased translocation of effector protein in the type III secretion system (T3SS). These mutant strains have also exhibited higher bacterial adhesion and invasion (35). The reported results are also consistent with the higher internalization of LPS mutant bacteria than of wild-type B. pseudomallei in infected A549 cells (Fig. 3b). Since B. pseudomallei also possesses the T3SS, whether or not the direct effect of the O-antigen-altering T3SS functions in the noncanonical inflammasome pathway in B. pseudomallei-infected cells is underinvestigated.

Interestingly, the number of intracellular bacteria of the LPS mutant in caspase-4-depleted cells was significantly lower than that of wild-type-infected cells. These results suggest that B. pseudomallei might also interfere with other caspase-4-independent killing mechanisms in infected A549 cells. There are several antimicrobial mechanisms preceding cell death in epithelial cells, including secretion of antimicrobial peptides. For example, human β-defensins are antimicrobial peptides that are induced in A549 cells during respiratory infection with Gram-negative bacteria, such as Brucella abortus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (36, 37). The study of Burkholderia spp. also shows that it can highly resist one member of the β-defensin family (38).

B. pseudomallei can evade the host innate immune system through various mechanisms. Our group has previously reported the ability of B. pseudomallei in interfering with the membrane-bound receptor-mediated killing mechanism in mouse macrophages (26, 39, 40). In this study, we extended our work on the cytosolic sensor, the noncanonical inflammatory caspase-4, and demonstrated its contribution to B. pseudomallei growth restriction. We also reported the susceptible phenotype of LPS mutant B. pseudomallei to survive in an infected human alveolar epithelial cell line (A549). By counteracting caspase-4 activation, B. pseudomallei could avoid the caspase-4-mediated killing mechanism for its intracellular growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and culture condition.

The human type II alveolar epithelial cell line A549 (ATCC CCL-185) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in Ham’s F12 (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% l-glutamine (Gibco) at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator.

Bacterial strains.

The wild-type B. pseudomallei (1026b strain) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) mutant (SRM117 strain) were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with agitation at 150 rpm (25). The log-phase bacterial cultures were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and adjusted to the desired concentration by measuring the optical density at 650 nm. CFU were calculated from the precalibrated standard curve.

Infection of human alveolar epithelial A549 cells.

An overnight culture of the human alveolar epithelial A549 cells (4 × 105 cells) in a 6-well plate was cocultured with the bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 2 h. The infected cells were subjected to the antibiotic protection assay to remove extracellular bacteria. The infected cells were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS and treated with complete Ham’s F12 containing 250 μg/ml kanamycin for 2 h to eliminate the remaining extracellular bacteria. The infection was allowed to continue in the complete culture medium containing 20 μg/ml of kanamycin until the end of the experiment.

Depletion of caspase-4 in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells.

The negative control siRNAs and caspase-4 siRNAs were transfected into A549 cells (1.5 × 105 cells) at 48 h before B. pseudomallei infection according to the manufacturer’s protocol for Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The expression of the target protein was determined by immunoblotting. Caspase-4 siRNAs (siRNA ID HSS141457) were purchased from Invitrogen. AllStar negative control siRNAs (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used.

Quantification of intracellular bacteria.

A standard antibiotic protection assay was performed to determine the number of viable intracellular bacteria. At the indicated time points, the infected A549 cells were washed with PBS. The intracellular bacteria were obtained by lysing the infected A549 cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 and cultured in tryptic soy agar. The number of intracellular bacteria is expressed as CFU/ml.

Reverse transcription-PCR.

RNA was isolated from the infected cells according to manufacturer’s instruction (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany). The cDNAs were further converted using the avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcription enzyme (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. The amplified products were then electrophoresed using 1.5% agarose gel. The agarose gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under a UV lamp.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of the specific primers for PCR amplification

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CASP4 | Forward | ACA-AAG-TTC-GGG-TCA-TGG-CA |

| Reverse | GCT-GAC-TCC-ATA-TCC-CTG-GC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | ATG-GGG-AAG-GTG-AAG-GTC-G |

| Reverse | GGG-GTC-ATT-GAT-GGC-AAC-A |

Immunoblotting.

The cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40. The lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). The nonspecific binding sites on the membrane were blocked with 5% blocking solution (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland) for 1 h before proteins were allowed to react with specific primary antibodies including caspase-4 (Cell Signaling Technology) and β-actin (Merck Millipore) at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed three times with 0.1% phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (R&D Systems) for 1 h at room temperature. The chemiluminescence substrate (Roche Diagnostics) was added, and proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and then exposed to high-performance chemiluminescence film (Amersham Biosciences).

LPS electroporation.

The E. coli LPS (O111:B4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The human alveolar epithelial A549 cells were transfected with 1 μg of E. coli LPS (O111:B4). The overnight culture was trypsinized and resuspended in 100 μl of Nucleofector solution kit V (Amaxa, London, UK). The LPS was then added to the cell suspension, and cells were nucleoporated using the Amaxa Nucleofector apparatus (program G-016) (41, 42). The electroporated cells were transferred to a new 6-well plate containing 1 ml complete medium.

Statistical analysis.

If not specified otherwise, all experiments were conducted at least three times. Experimental values are expressed as means ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance of this mean is assessed by using Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The P values of <0.05, <0.01, and <0.001 are indicated as *, **, and ***, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a research grant from the Thailand Research Fund (grant number BRG5980004) and Mahidol University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Virk HS, Torres AG, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ, Dance DAB, Limmathurotsakul D. 2018. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:17107. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limmathurotsakul D, Wongratanacheewin S, Teerawattanasook N, Wongsuvan G, Chaisuksant S, Chetchotisakd P, Chaowagul W, Day NP, Peacock SJ. 2010. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82:1113–1117. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Strych U, Chang L-Y, Lim YAL, Goodenow MM, AbuBakar S. 2015. Neglected tropical diseases among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): overview and update. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limmathurotsakul D, Golding N, Dance DA, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Moyes CL, Rolim DB, Bertherat E, Day NP, Peacock SJ, Hay SI. 2016. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol 1:15008. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie BJ, Jacups SP. 2003. Intensity of rainfall and severity of melioidosis, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 9:1538–1542. doi: 10.3201/eid0912.020750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Pang L, Sim SH, Goh KT, Ravikumar S, Win MS, Tan G, Cook AR, Fisher D, Chai LY. 2015. Association of melioidosis incidence with rainfall and humidity, Singapore, 2003–2012. Emerg Infect Dis 21:159–162. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AC, Currie BJ. 2005. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:383–416. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.383-416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2010. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yazdi AS, Guarda G, D'Ombrain MC, Drexler SK. 2010. Inflammatory caspases in innate immunity and inflammation. J Innate Immun 2:228–237. doi: 10.1159/000283688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. 2002. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. 2014. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell 157:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li P, Hu L, Shao F. 2014. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 514:187–192. doi: 10.1038/nature13683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhter A, Caution K, Abu Khweek A, Tazi M, Abdulrahman BA, Abdelaziz DH, Voss OH, Doseff AI, Hassan H, Azad AK, Schlesinger LS, Wewers MD, Gavrilin MA, Amer AO. 2012. Caspase-11 promotes the fusion of phagosomes harboring pathogenic bacteria with lysosomes by modulating actin polymerization. Immunity 37:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knodler LA, Crowley SM, Sham HP, Yang H, Wrande M, Ma C, Ernst RK, Steele-Mortimer O, Celli J, Vallance BA. 2014. Noncanonical inflammasome activation of caspase-4/caspase-11 mediates epithelial defenses against enteric bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 16:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casson CN, Yu J, Reyes VM, Taschuk FO, Yadav A, Copenhaver AM, Nguyen HT, Collman RG, Shin S. 2015. Human caspase-4 mediates noncanonical inflammasome activation against Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:6688–6693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421699112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Sahoo M, Lantier L, Warawa J, Cordero H, Deobald K, Re F. 2018. Caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis of lung epithelial cells protects from melioidosis while caspase-1 mediates macrophage pyroptosis and production of IL-18. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007105. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aachoui Y, Leaf IA, Hagar JA, Fontana MF, Campos CG, Zak DE, Tan MH, Cotter PA, Vance RE, Aderem A, Miao EA. 2013. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science 339:975–978. doi: 10.1126/science.1230751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones AL, Beveridge TJ, Woods DE. 1996. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun 64:782–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kespichayawattana W, Rattanachetkul S, Wanun T, Utaisincharoen P, Sirisinha S. 2000. Burkholderia pseudomallei induces cell fusion and actin-associated membrane protrusion: a possible mechanism for cell-to-cell spreading. Infect Immun 68:5377–5384. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5377-5384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phewkliang A, Wongratanacheewin S, Chareonsudjai S. 2010. Role of Burkholderia pseudomallei in the invasion, replication and induction of apoptosis in human epithelial cell lines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 41:1164–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagrange B, Benaoudia S, Wallet P, Magnotti F, Provost A, Michal F, Martin A, Di Lorenzo F, Py BF, Molinaro A, Henry T. 2018. Human caspase-4 detects tetra-acylated LPS and cytosolic Francisella and functions differently from murine caspase-11. Nat Commun 9:242. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02682-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aachoui Y, Kajiwara Y, Leaf IA, Mao D, Ting JP, Coers J, Aderem A, Buxbaum JD, Miao EA. 2015. Canonical inflammasomes drive IFN-gamma to prime caspase-11 in defense against a cytosol-invasive bacterium. Cell Host Microbe 18:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi T, Ogawa M, Sanada T, Mimuro H, Kim M, Ashida H, Akakura R, Yoshida M, Kawalec M, Reichhart JM, Mizushima T, Sasakawa C. 2013. The Shigella OspC3 effector inhibits caspase-4, antagonizes inflammatory cell death, and promotes epithelial infection. Cell Host Microbe 13:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vellasamy KM, Mariappan V, Shankar EM, Vadivelu J. 2016. Burkholderia pseudomallei differentially regulates host innate immune response genes for intracellular survival in lung epithelial cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeShazer D, Brett PJ, Woods DE. 1998. The type II O-antigenic polysaccharide moiety of Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharide is required for serum resistance and virulence. Mol Microbiol 30:1081–1100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arjcharoen S, Wikraiphat C, Pudla M, Limposuwan K, Woods DE, Sirisinha S, Utaisincharoen P. 2007. Fate of a Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharide mutant in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7: possible role for the O-antigenic polysaccharide moiety of lipopolysaccharide in internalization and intracellular survival. Infect Immun 75:4298–4304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00285-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kespichayawattana W, Intachote P, Utaisincharoen P, Sirisinha S. 2004. Virulent Burkholderia pseudomallei is more efficient than avirulent Burkholderia thailandensis in invasion of and adherence to cultured human epithelial cells. Microb Pathog 36:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Essex-Lopresti AE, Boddey JA, Thomas R, Smith MP, Hartley MG, Atkins T, Brown NF, Tsang CH, Peak IR, Hill J, Beacham IR, Titball RW. 2005. A type IV pilin, PilA, contributes to adherence of Burkholderia pseudomallei and virulence in vivo. Infect Immun 73:1260–1264. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1260-1264.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuaygud T, Tungpradabkul S, Sirisinha S, Chua KL, Utaisincharoen P. 2008. A role of Burkholderia pseudomallei flagella as a virulent factor. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102(Suppl):S140–S144. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sollberger G, Strittmatter GE, Kistowska M, French LE, Beer HD. 2012. Caspase-4 is required for activation of inflammasomes. J Immunol 188:1992–2000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kajiwara Y, Schiff T, Voloudakis G, Gama Sosa MA, Elder G, Bozdagi O, Buxbaum JD. 2014. A critical role for human caspase-4 in endotoxin sensitivity. J Immunol 193:335–343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause K, Caution K, Badr A, Hamilton K, Saleh A, Patel K, Seveau S, Hall-Stoodley L, Hegazi R, Zhang X, Gavrilin MA, Amer AO. 2018. CASP4/caspase-11 promotes autophagosome formation in response to bacterial infection. Autophagy 14:1928–1942. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1491494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurston TL, Matthews SA, Jennings E, Alix E, Shao F, Shenoy AR, Birrell MA, Holden DW. 2016. Growth inhibition of cytosolic Salmonella by caspase-1 and caspase-11 precedes host cell death. Nat Commun 7:13292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caution K, Gavrilin MA, Tazi M, Kanneganti A, Layman D, Hoque S, Krause K, Amer AO. 2015. Caspase-11 and caspase-1 differentially modulate actin polymerization via RhoA and slingshot proteins to promote bacterial clearance. Sci Rep 5:18479. doi: 10.1038/srep18479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holzer SU, Schlumberger MC, Jackel D, Hensel M. 2009. Effect of the O-antigen length of lipopolysaccharide on the functions of type III secretion systems in Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun 77:5458–5470. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00871-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hielpos MS, Ferrero MC, Fernandez AG, Bonetto J, Giambartolomei GH, Fossati CA, Baldi PC. 2015. CCL20 and beta-defensin 2 production by human lung epithelial cells and macrophages in response to Brucella abortus infection. PLoS One 10:e0140408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivas-Santiago B, Schwander SK, Sarabia C, Diamond G, Klein-Patel ME, Hernandez-Pando R, Ellner JJ, Sada E. 2005. Human {beta}-defensin 2 is expressed and associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis during infection of human alveolar epithelial cells. Infect Immun 73:4505–4511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4505-4511.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahly H, Schubert S, Harder J, Rautenberg P, Ullmann U, Schroder J, Podschun R. 2003. Burkholderia is highly resistant to human beta-defensin 3. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1739–1741. doi: 10.1128/aac.47.5.1739-1741.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tangsudjai S, Pudla M, Limposuwan K, Woods DE, Sirisinha S, Utaisincharoen P. 2010. Involvement of the MyD88-independent pathway in controlling the intracellular fate of Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. Microbiol Immunol 54:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pudla M, Limposuwan K, Utaisincharoen P. 2011. Burkholderia pseudomallei-induced expression of a negative regulator, sterile-alpha and armadillo motif-containing protein, in mouse macrophages: a possible mechanism for suppression of the MyD88-independent pathway. Infect Immun 79:2921–2927. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01254-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Opitz B, Vinzing M, van Laak V, Schmeck B, Heine G, Günther S, Preissner R, Slevogt H, N'Guessan PD, Eitel J, Goldmann T, Flieger A, Suttorp N, Hippenstiel S. 2006. Legionella pneumophila induces IFNbeta in lung epithelial cells via IPS-1 and IRF3, which also control bacterial replication. J Biol Chem 281:36173–36179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinzing M, Eitel J, Lippmann J, Hocke AC, Zahlten J, Slevogt H, N'guessan PD, Günther S, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, Flieger A, Suttorp N, Opitz B. 2008. NAIP and Ipaf control Legionella pneumophila replication in human cells. J Immunol 180:6808–6815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]