Abstract

Objectives:

Paternal involvement is associated with improved infant and maternal outcomes. We compared maternal behaviors associated with infant morbidity and mortality among married women, unmarried women with an acknowledgment of paternity (AOP; a proxy for paternal involvement) signed in the hospital, and unmarried women without an AOP in a representative sample of mothers in the United States from 32 sites.

Methods:

We analyzed 2012-2015 data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, which collects site-specific, population-based data on preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors, and experiences from women with a recent live birth. We calculated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to examine associations between level of paternal involvement and maternal perinatal behaviors.

Results:

Of 113 020 respondents (weighted N = 6 159 027), 61.5% were married, 27.4% were unmarried with an AOP, and 11.1% were unmarried without an AOP. Compared with married women and unmarried women with an AOP, unmarried women without an AOP were less likely to initiate prenatal care during the first trimester (married, aPR [95% CI], 0.94 [0.92-0.95]; unmarried with AOP, 0.97 [0.95-0.98]), ever breastfeed (married, 0.89 [0.87-0.90]; unmarried with AOP, 0.95 [0.94-0.97]), and breastfeed at least 8 weeks (married, 0.76 [0.74-0.79]; unmarried with AOP, 0.93 [0.90-0.96]) and were more likely to use alcohol during pregnancy (married, 1.20 [1.05-1.37]; unmarried with AOP, 1.21 [1.06-1.39]) and smoke during pregnancy (married, 3.18 [2.90-3.49]; unmarried with AOP, 1.23 [1.15-1.32]) and after pregnancy (married, 2.93 [2.72-3.15]; unmarried with AOP, 1.17 [1.10-1.23]).

Conclusions:

Use of information on the AOP in addition to marital status provides a better understanding of factors that affect maternal behaviors.

Keywords: paternal involvement, maternal perinatal behaviors

Maternal behaviors and experiences during the perinatal period can have long-lasting effects on a child’s health.1 Fathers play a critical role in the health and development of their children.2,3 Parental relationship status can be an important social determinant of child well-being; its importance is often demonstrated by disparities in health outcomes between children of married and unmarried mothers.4,5 In the absence of direct data on paternal involvement, being married generally suggests the presence of a partner and paternal involvement; in contrast, when a mother is unmarried, the presence of partner and paternal involvement is unclear.6 Partner support and paternal involvement are linked to improved maternal prenatal and postpartum behaviors, including early initiation of prenatal care,7 smoking cessation,7 and breastfeeding initiation and duration.8-10 In addition, paternal involvement is associated with improved birth and developmental, psychological, cognitive, and academic outcomes.2

Despite the demonstrated benefits of paternal involvement, fathers are underrepresented in research on maternal perinatal behaviors, child development, and health outcomes.11-15 As family dynamics have transitioned—the percentage of births to unmarried mothers in the United States has more than doubled since the 1980s (from 18% in 1980 to 40% in 2016)16,17 and cohabitating unions have increased18—marital status alone may not accurately represent the extent of paternal involvement.6,19 Although the number of births to unmarried mothers has increased,16,17 most (75%) fathers in the United States report living with all of their biological children, and 81.5% live with at least 1 of their biological children.20

Unmarried fathers in the United States may establish informal relationships with their children, but they have no rights as the biological father until paternity is legally established.21 Paternity can be established voluntarily for children of unmarried parents when both the mother and father sign an acknowledgment of paternity (AOP),21 a supplementary form to the birth certificate.22 Although paternity may be established via the courts, most paternities (81%) are established by using an AOP in the hospital.23 Paternity establishment through use of the AOP, compared with a lack of paternity establishment, is linked to fathers being more likely to provide child support and spend time with their infants,23 to infants being less likely to live in poverty, and to lower rates of infant mortality.24 The AOP may serve as a novel proxy for paternal involvement when other measures of paternal involvement are unavailable or limited.

Little is known about the relationship between having an AOP and maternal protective and health-risk behaviors during the perinatal period. The objective of this study was to investigate selected maternal protective behaviors (ie, initiation of prenatal care during the first trimester, breastfeeding initiation and duration, and infant sleep position) and health-risk behaviors (ie, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy and smoking after pregnancy) associated with infant morbidity and mortality among married women, unmarried women with an AOP signed in the hospital, and unmarried women without an AOP in a representative sample of births from 31 states and New York City.

Methods

Data Source

The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a site-specific, population-based surveillance system, assesses maternal self-reported preconception, prenatal, and postpartum attitudes, behaviors, and experiences among women with a recent live birth before, during, and shortly after pregnancy. PRAMS participants are randomly sampled from state birth certificate files to be representative of the state’s birth population. PRAMS methodology is detailed elsewhere.25 Data collected from PRAMS are linked to birth certificate files, which include data on whether an AOP was completed in the hospital. We analyzed PRAMS data from 2012-2015 from 32 sites with information on whether an AOP was signed in the hospital and met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) response rate threshold for PRAMS data release for at least 1 year during the study period (ie, ≥60% from 2012-2014 and ≥55% in 2015).25 The weighted overall mean response rate across sites meeting the threshold for the study period was 64%.

Study Respondents

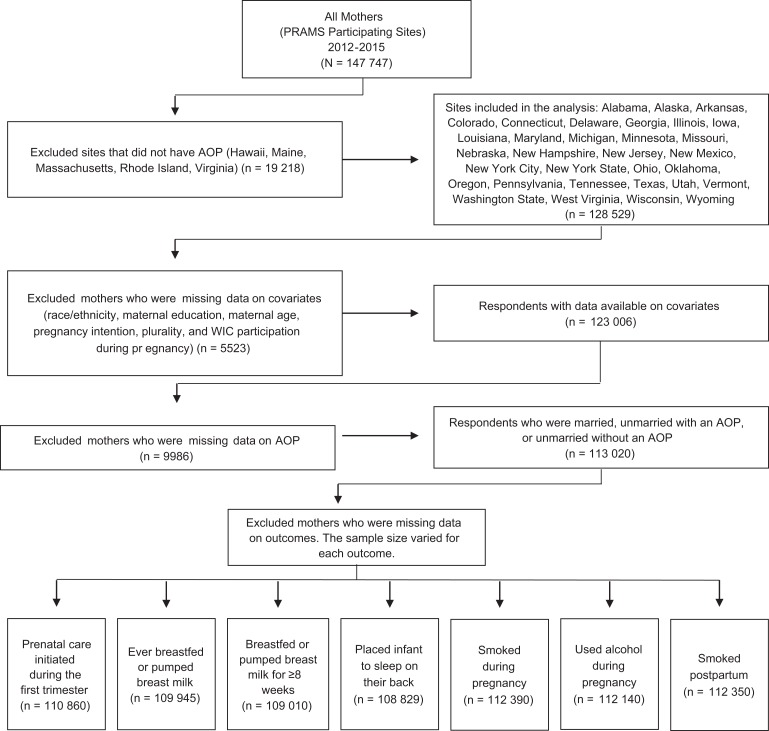

We categorized respondents as married, unmarried with an AOP, or unmarried without an AOP. We excluded respondents who were missing data on marital status or the AOP, covariates, and outcomes from the PRAMS survey. Analytic sample sizes for each outcome varied because of missing responses and differences in survey skip patterns (Figure). Women who were not living with their infants or whose infants were deceased were instructed to skip questions on breastfeeding initiation and duration and infant sleep position.

Figure.

Flow chart of the selection and exclusion of respondents for analyses of data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) to compare maternal behaviors associated with infant morbidity and mortality among married women, unmarried women with an acknowledgment of paternity (AOP; a proxy for paternal involvement) signed in the hospital, and unmarried women without an AOP in a representative sample of mothers in the United States from 32 sites. Data were weighted for survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse. Data source: Shulman et al.25 Abbreviation: WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Outcome Measures

We assessed trimester of prenatal care initiation, breastfeeding initiation and duration, infant sleep position, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, and smoking at the times the PRAMS survey was completed (ie, postpartum smoking). We categorized prenatal care initiation into 2 groups: (1) starting care during the first trimester or (2) starting care during the second or third trimester or never receiving care. We categorized breastfeeding initiation as (1) ever breastfed or pumped breast milk or (2) never breastfed or pumped breast milk. We categorized breastfeeding duration as those who (1) breastfed or pumped breast milk for 8 weeks or longer in any amount or (2) never breastfed or stopped breastfeeding or pumping breast milk before the infant was 8 weeks of age. We categorized infant sleep position as placing their infant to sleep most of the time (1) on their back (the safe position) or (2) on their stomach or side. We categorized smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy as (1) any cigarette smoking or alcohol use during the last 3 months of pregnancy or (2) no cigarette smoking or alcohol use during the last 3 months of pregnancy. We categorized postpartum smoking as (1) any cigarette smoking at the time the PRAMS survey was completed (typically 3-5 months postpartum and no earlier than 2 months postpartum) or (2) no postpartum smoking.

Covariates

We obtained data on maternal characteristics from both the birth certificate (maternal race/ethnicity, age, education, and plurality) and from PRAMS survey responses (participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC] during pregnancy and pregnancy intention).

Statistical Analyses

PRAMS data are weighted by CDC to account for survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse. We analyzed PRAMS data by using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.026 to account for the complex sampling design. We used descriptive statistics to describe demographic characteristics of respondents in the sample, and we used the Wald χ2 test (with P < .05 considered significant) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to assess differences in the level of paternal involvement by maternal characteristics. Using the average marginal predictions approach to logistic regression,27 we generated adjusted prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) with 95% CIs to examine associations between level of paternal involvement (married women vs unmarried women with and without an AOP and unmarried women with an AOP vs unmarried women without an AOP) with protective and health-risk behaviors. We constructed separate multivariable logistic models for each outcome and adjusted them for the aforementioned covariates as potential confounders. CDC and each site’s institutional review board approved the PRAMS protocol.

Results

A total of 113 020 respondents represented a weighted population of 6 159 027 women. Among the study population, 61.5% were married, 27.4% were unmarried with an AOP, and 11.1% were unmarried without an AOP. Most women were non-Hispanic white (61.2%), completed >12 years of education (62.2%), were aged 25-34 (57.1%), reported intending pregnancy (56.0%), did not participate in WIC (56.3%), and had a singleton birth (98.2%). The distribution of maternal characteristics differed among women who were married, unmarried with an AOP, and unmarried without an AOP. Among married women, most were non-Hispanic white, had completed >12 years of education, were aged 25-34, reported intended pregnancy, and did not participate in WIC. Compared with married women, a lower proportion of unmarried women, with and without an AOP, were non-Hispanic white (71.4% vs 47.7% and 38.0%, respectively), had completed >12 years of education (76.0% vs 42.0% and 35.6%, respectively), were aged 25-34 (67.0% vs 42.9% and 37.3%, respectively), reported intended pregnancy (70.2% vs 36.7% and 25.0%, respectively), and did not participate in WIC (74.5% vs 28.7% and 23.5%, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of women who were married, unmarried with an acknowledgment of paternity (AOP), or unmarried without an AOP, 32 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) sites,a,b 2012-2015

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 113 020) | Married (n = 67 965) | Unmarried With an AOP (n = 29 649) | Unmarried Without an AOP (n = 15 406) | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | — | 61.5 (61.0-61.9) | 27.4 (27.0-27.9) | 11.1 (10.8-11.4) | — |

| Maternal race/ethnicityd | <.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 61.2 (60.8-61.6) | 71.4 (70.9-71.8) | 47.7 (46.8-48.6) | 38.0 (36.7-39.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.4 (13.1-13.6) | 5.9 (5.6-6.1) | 20.1 (19.4-20.8) | 38.2 (36.9-39.5) | |

| Hispanic | 16.9 (16.7-17.2) | 12.9 (12.6-13.3) | 25.9 (25.0-26.7) | 17.0 (15.8-18.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic othere | 8.5 (8.3-8.7) | 9.8 (9.5-10.1) | 6.3 (5.9-6.7) | 6.8 (6.2-7.4) | |

| Education, y | <.001 | ||||

| <12 | 13.8 (13.5-14.1) | 7.8 (7.4-8.1) | 21.7 (20.9-22.5) | 27.7 (26.4-29.0) | |

| 12 | 24.0 (23.6-24.4) | 16.2 (15.8-16.7) | 36.3 (35.4-37.2) | 36.7 (35.4-38.1) | |

| >12 | 62.2 (61.7-62.6) | 76.0 (76.6-76.5) | 42.0 (41.1-43.0) | 35.6 (34.3-36.9) | |

| Age, y | <.001 | ||||

| ≤19 | 6.2 (6.0-6.4) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 13.2 (12.5-13.9) | 17.2 (16.2-18.2) | |

| 20-24 | 21.1 (20.8-21.5) | 12.2 (11.8-12.6) | 35.0 (34.1-36.0) | 36.4 (35.1-37.8) | |

| 25-34 | 57.1 (56.7-57.6) | 67.0 (66.5-67.6) | 42.9 (41.9-43.8) | 37.3 (36.0-38.7) | |

| ≥35 | 15.6 (15.2-15.9) | 19.7 (19.3-20.2) | 8.9 (8.3-9.4) | 9.1 (8.3-9.9) | |

| Pregnancy intentionf | <.001 | ||||

| Intended | 56.0 (55.5-56.4) | 70.2 (69.6-70.7) | 36.7 (35.8-37.6) | 25.0 (23.8-26.2) | |

| Unintended | 29.5 (29.1-29.9) | 19.7 (19.2-20.2) | 42.8 (41.9-43.8) | 50.7 (49.3-52.1) | |

| Unsure | 14.5 (14.2-14.9) | 10.1 (9.8-10.5) | 20.5 (19.7-21.2) | 24.3 (23.1-25.5) | |

| WIC participation during pregnancy | <.001 | ||||

| No | 56.3 (55.8-56.7) | 74.5 (74.0-75.0) | 28.7 (27.8-29.5) | 23.5 (22.3-24.7) | |

| Yes | 43.7 (43.3-44.2) | 25.5 (25.0-26.0) | 71.3 (70.5-72.2) | 76.5 (75.3-77.7) | |

| Pluralityg | <.001 | ||||

| Singleton | 98.2 (98.1-98.3) | 98.0 (97.9-98.1) | 98.7 (98.5-98.8) | 98.2 (97.9-98.5) | |

| Twin or other multiples | 1.8 (1.7-1.9) | 2.0 (1.9-2.1) | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | |

Abbreviation: WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

a Data source: Shulman et al.25 PRAMS sites data availability by year: 2012: Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York City, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2013: Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2014: Alabama, Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2015: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

b Data were weighted for survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse. All values are weighted percentage (95% confidence interval).

c The Wald χ2 test and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess differences; P < .05 was considered significant.

d Vermont does not specify race/ethnicity for respondents who do not identify as non-Hispanic white. Respondents in Vermont are coded as non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic other.

e Includes women who identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, Alaska Native or Native American, and non-Hispanic on the birth certificate.

f Respondents were asked, “Thinking back to just before you got pregnant with your new baby, how did you feel about becoming pregnant?” Respondents who selected “I wanted to be pregnant sooner” or “I wanted to be pregnant then” were categorized as “intended.” Respondents who selected “I wanted to be pregnant later” or “I didn’t want to be pregnant then or at any time in the future” were categorized as “unintended.” Respondents who selected “I wasn’t sure what I wanted” were categorized as “unsure.”

g Plurality in Vermont was not reported to PRAMS; as such, all births in Vermont were considered “singletons.”

Multivariable Models for Maternal Protective and Health-Risk Behaviors

Compared with married women (Table 2), unmarried women both with and without an AOP had a lower prevalence of prenatal care initiation during the first trimester (married vs unmarried with AOP, aPR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-0.98; married vs unmarried without AOP, aPR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.95), ever breastfed or pumped breast milk (married vs unmarried with AOP, aPR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.93-0.95; married vs unmarried without AOP, aPR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.87-0.90), and any breastfeeding when the infant was 8 weeks of age (married vs unmarried with AOP, aPR = 0.82; 95% CI, 0.80-0.84; married vs unmarried without AOP, aPR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.74-0.79). Compared with unmarried women with an AOP, unmarried women without an AOP had a lower prevalence of prenatal care initiation during the first trimester (aPR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-0.98), ever breastfeeding or pumping breast milk (aPR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.94-0.97), and any breastfeeding when the infant was 8 weeks of age (aPR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96). The prevalence of placing infants to sleep on their back did not differ between women who were married and women who were unmarried with an AOP or without an AOP.

Table 2.

Adjusted prevalence and prevalence ratios for maternal protective and health-risk behaviors during the perinatal period, by paternal involvement as measured on the birth certificate, 32 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) sites,a,b 2012-2015

| Maternal Protective and Health-Risk Behaviors | Total, No. | Married, %b |

Unmarried

With an AOP, %b |

Unmarried

Without an AOP, %b |

Unmarried With an AOP vs Married, aPR (95% CI)b,c | Unmarried Without an AOP vs Married, aPR (95% CI)b,c | Unmarried Without an AOP vs Unmarried With an AOP, aPR (95% CI)b,d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal care initiated during the first trimester | 110 860 | 86.3 | 83.8 | 80.9 | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | 0.94 (0.92-0.95) | 0.97 (0.95-0.98) |

| Ever breastfed or pumped breast milk | 109 945 | 88.7 | 83.0 | 78.8 | 0.94 (0.93-0.95) | 0.89 (0.87-0.90) | 0.95 (0.94-0.97) |

| Breastfed or pumped breast milk for 8 weeks or longer | 109 010 | 69.3 | 56.8 | 53.0 | 0.82 (0.80-0.84) | 0.76 (0.74-0.79) | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) |

| Placed infant to sleep on their back | 108 829 | 77.4 | 75.9 | 76.9 | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 112 390 | 5.6 | 14.5 | 17.8 | 2.59 (2.39-2.81) | 3.18 (2.90-3.49) | 1.23 (1.15-1.32) |

| Used alcohol during pregnancy | 112 140 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 0.99 (0.90-1.08) | 1.20 (1.05-1.37) | 1.21 (1.06-1.39) |

| Smoked postpartum | 112 350 | 8.2 | 20.7 | 24.1 | 2.51 (2.35-2.68) | 2.93 (2.72-3.15) | 1.17 (1.10-1.23) |

Abbreviations: AOP, acknowledgment of paternity; aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio.

a Data source: Shulman et al.25 PRAMS sites data availability by year: 2012: Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York City, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2013. Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2014: Alabama, Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. 2015: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington State, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

b Data were weighted for survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse. All models were adjusted for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, pregnancy intention, plurality, and participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children during pregnancy.

c Reference group: married.

d Reference group: unmarried with an AOP.

Compared with married women, unmarried women both with and without an AOP had a higher prevalence of smoking during pregnancy (married vs unmarried with AOP, aPR = 2.59; 95% CI, 2.39-2.81; married vs unmarried without AOP, aPR = 3.18; 95% CI, 2.90-3.49) and after pregnancy (married vs unmarried with AOP, aPR = 2.51; 95% CI, 2.35-2.68; married vs unmarried without AOP, aPR = 2.93; 95% CI, 2.72-3.15). Unmarried women without an AOP compared with unmarried women with an AOP had a higher prevalence of smoking during pregnancy (aPR = 1.23; 95% CI, 1.15-1.32) and after pregnancy (aPR = 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.23). Compared with married women, unmarried women without an AOP had a significantly higher prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy (aPR = 1.20; 95% CI, 1.05-1.37), although we found no difference between married women and unmarried women with an AOP. However, unmarried women without an AOP had a higher prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy than unmarried women with an AOP (aPR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.06-1.39) (Table 2).

Discussion

Using a large population-based sample of women with a recent live birth, we found several maternal prenatal and postpartum behaviors that varied among women who were married, unmarried with an AOP, and unmarried without an AOP. Although we found that the prevalence of prenatal care initiation in the first trimester was higher among women who were married than among unmarried women with an AOP or without an AOP, the difference was small and may be explained by covariates that were not available in the PRAMS data set, such as paternal characteristics. However, of note, previous research has also found an association between paternal involvement during pregnancy and initiation of prenatal care during the first trimester.7 Prenatal care visits are opportunities not only to promote the importance of maternal health behaviors during pregnancy, but also to facilitate the transition to parenthood for mothers and fathers. Prenatal care visits may also serve as opportunities for health care providers to educate mothers and fathers on establishing paternity in the hospital and identify mothers who may be at risk for low levels of paternal support.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months postpartum and continued breastfeeding until at least 1 year postpartum or beyond, as long as is mutually desired by mother and infant.28 Research shows a gap in breastfeeding rates between married and unmarried women.29,30 We found that unmarried women with or without an AOP were less likely than married women to initiate and continue breastfeeding until the infant was at least 8 weeks of age. However, unmarried women without an AOP were less likely than unmarried women with an AOP to initiate and continue breastfeeding. Our findings suggest that disparities in breastfeeding outcomes by marital status may be narrower than previously found when accounting for paternity establishment. However, we were unable to assess whether this association remains after 8 weeks postpartum. One possible explanation for these findings is that compared with unmarried mothers without an AOP, married mothers and unmarried mothers with an AOP may have higher levels of emotional, physical (eg, shared household responsibilities), and financial support from fathers, which may facilitate breastfeeding.31 Research has demonstrated that paternal engagement in breastfeeding interventions have helped improve rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration.8-10 Actively engaging fathers who are present during prenatal and postpartum maternal and infant health care visits in breastfeeding discussions and how they can best support their partners may be one strategy that health care providers can use to improve breastfeeding outcomes.2,31

Unmarried women are more likely than married women to smoke32 or use alcohol during pregnancy.33,34 We found that unmarried women with or without an AOP were approximately 2-3 times more likely than married women to smoke during and after pregnancy. Unmarried women without an AOP were more likely than unmarried women with an AOP to smoke during and after pregnancy. Unmarried women without an AOP were also more likely than both married women and unmarried women with an AOP to consume alcohol during pregnancy. Our findings suggest that among unmarried mothers, engagement in health-risk behaviors (ie, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy and smoking after pregnancy) differed by paternity establishment. This difference in engagement in health-risk behaviors identifies a potentially higher-risk subgroup of adverse health outcomes.

This study adds to the growing literature7,14,35 on the association between paternal involvement and maternal perinatal behaviors. Variations in maternal perinatal behaviors by marital status and completion of an AOP in the hospital highlight opportunities to develop and tailor appropriate interventions and practices based on parental relationship dynamics to improve infant health outcomes. Use of the AOP in addition to information on marital status provides information to better understand factors that affect maternal behaviors.

Given the high and increasing prevalence of births to unmarried women in the United States4 and disparities in health behaviors found in our analysis between married and unmarried mothers by AOP status, our findings have implications for clinicians. As outlined in the 2016 American Academy of Pediatrics Report on Fathers,2 clinicians who care for children and families may explore the status and quality of the parents’ relationship. If the mother attends health care visits alone, simply asking about the home situation and level of paternal involvement may provide insight into the need for assistance or support.2 In contrast, if both parents attend the visit together, this visit may serve as an opportunity to engage fathers on the importance of their role in their child’s well-being.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, although the presence of an AOP provides additional insight into family dynamics because both the infant’s mother and father must voluntarily establish it, we lacked information on the context of the parental relationship, extent of paternal involvement, and whether the AOP had been signed after hospital discharge or paternity had been established via the courts. We were also unable to assess whether women were in a relationship with someone other than their infant’s father (eg, same-sex partnerships) but who may influence maternal behaviors. In addition, some parents may choose not to establish formal paternity arrangements (eg, to maintain eligibility for social services) while still having informal arrangements in place. Second, the association between the AOP and fathers who lived with their children was not known, and data on paternal residency were not available. Research has shown that, in general, fathers who live with their children are more actively involved in caregiving than fathers who live apart from their children.6 Third, outcomes from PRAMS were based on self-report and may be subject to social desirability and recall bias. For example, mothers may be less likely to report behaviors that are viewed negatively (eg, substance use during pregnancy) and more likely to report behaviors that are viewed positively (eg, attending prenatal care visits, breastfeeding). In addition, because of question wording, we were not able to capture data on all women who smoked or drank alcohol during pregnancy if they discontinued use before the third trimester.

Fourth, we were unable to assess paternal characteristics (eg, paternal race/ethnicity, education, age) because these data are reported on the birth certificate only if the fathers are married or an AOP is completed. Some evidence indicates that AOPs are more common for infants of non-Hispanic white mothers and fathers who are aged ≥20 and have at least a high school education than for infants of younger, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic mothers and fathers with less education.23 Although we adjusted for confounders in our analyses, residual confounding from paternal characteristics and other unmeasured confounders could have biased our estimates; as such, results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the AOP may serve as a proxy, but it is not a direct indicator of the extent of paternal involvement during pregnancy or postpartum interactions with the mother or infant. Although we found associations between marital status and the presence or absence of an AOP with maternal perinatal behaviors, these findings are correlational and not causal. Little is known about what type or amount of paternal involvement positively or negatively affects maternal behaviors or infant outcomes. The relationship of paternal involvement and outcomes is likely to be related to broader issues of social support that we were unable to measure in this analysis. Further research is needed to better understand the scope of paternal involvement and how to further promote the involvement of fathers during the perinatal period and throughout the child’s life span.

Conclusions

In this site- and population-based analysis of mothers with a recent live birth, we found that mothers who were unmarried with or without an AOP were generally more likely than mothers who were married to report health-risk behaviors and less likely to report protective health behaviors. However, when an AOP was completed in the hospital, unmarried mothers with an AOP were more likely to report protective behaviors and less likely to report health-risk behaviors than mothers without an AOP. The use of the AOP, in combination with information on marital status, may serve as a novel proxy for paternal involvement when other measures are unavailable or limited. Given the increased risk of infant morbidity and mortality associated with health-risk maternal behaviors during the perinatal period, engaging fathers may help improve maternal and infant outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Working Group representatives: Alabama: Tammie Yelldell, MPH; Alaska: Kathy Perham-Hester, MS, MPH; Arkansas: Letitia de Graft-Johnson, DrPH, MHSA; Colorado: Ashley Juhl, MSPH; Connecticut: Jennifer Morin, MPH; Delaware: George Yocher, MS; Florida: Tara Hylton, MPH; Georgia: Florence A. Kanu, PhD, MPH; Hawaii: Matt Shim, PhD, MPH; Illinois: Julie Doetsch, MA; Iowa: Jennifer Pham; Kentucky: Tracey D. Jewell, MPH; Louisiana: Rosaria Trichilo, MPH; Maine: Tom Patenaude, MPH; Maryland: Laurie Kettinger, MS; Massachusetts: Hafsatou Diop, MD, MPH; Michigan: Peterson Haak; Mississippi: Brenda Hughes, MPPA; Missouri: Venkata Garikapaty, PhD; Montana: Emily Healy, MS; Nebraska: Jessica Seberger; New Hampshire: David J. Laflamme, PhD, MPH; New Jersey: Sharon Smith Cooley, MPH; New Mexico: Sarah Schrock, MPH; New York City: Pricila Mullachery, MPH; New York State: Anne Radigan; North Carolina: Kathleen Jones-Vessey, MS; North Dakota: Grace Njaou, MPH; Oklahoma: Ayesha Lampkins, MPH; Oregon: Cate Wilcox, MPH; Pennsylvania: Sara Thuma, MPH; Rhode Island: Karine Tolentino Monteiro, MPH; South Carolina: Kristin Simpson, MSW, MPA; Tennessee: Ransom Wyse, MPH; Texas: Tanya Guthrie, PhD; Utah: Nicole Stone, MPH; Vermont: Peggy Brozicevic; Virginia: Kenesha Smith, MSPH; Washington: Linda Lohdefinck; West Virginia: Melissa Baker, MA; Wisconsin: Fiona Weeks, MSPH; Wyoming: Lorie Wayne Chesnut; PRAMS Team, Women’s Health and Fertility Branch, Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Katherine Kortsmit was supported by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ORCID iD: Katherine Kortsmit, PhD, MPH, RD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7972-9117

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7972-9117

References

- 1. Mikkonen HM, Salonen MK, Häkkinen A, et al. The lifelong socioeconomic disadvantage of single-mother background—the Helsinki Birth Cohort study 1934-1944. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):817 doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3485-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yogman M, Garfield CF, Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: the role of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161128 doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman WL, Garfield C, Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. Fathers and pediatricians: enhancing men’s roles in the care and development of their children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1406–1411. doi:10.1542/peds.113.5.1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(1):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones J, Mosher WD. Fathers’ involvement with their children: United States, 2006-2010. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2013;(71):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin LT, McNamara MJ, Milot AS, Halle T, Hair EC. The effects of father involvement during pregnancy on receipt of prenatal care and maternal smoking. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:595–602. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0209-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Susin LR, Giugliani ER. Inclusion of fathers in an intervention to promote breastfeeding: impact on breastfeeding rates. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(4):386–392. doi:10.1177/0890334408323545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pisacane A, Continisio GI, Aldinucci M, D’Amora S, Continisio P. A controlled trial of the father’s role in breastfeeding promotion. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):e494–498. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abbass-Dick, Stern SB, Nelson LE, Watson W, Dennis CL. Coparenting breastfeeding support and exclusive breastfeeding: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):102–110. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morgan PJ, Young MD, Lloyd AB, et al. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):pii:e20162635 doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davison KK, Gicevic S, Aftosmes-Tobio A, et al. Fathers’ representation in observational studies on parenting and childhood obesity: a systematic review and content analysis. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):e14–e21. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Panter-Brick C, Burgess A, Eggerman M, McAllister F, Pruett K, Leckman JF. Practitioner review: engaging fathers—recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(11):1187–1212. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen K, Capponi S, Nyamukapa M, Baxter J, Crawford A, Worly B. Partner involvement during pregnancy and maternal health behaviors. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(11):2291–2298. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;69(6):604–612. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ventura SJ. Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;(18):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(287):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuo JC, Raley RK. Diverging patterns of union transition among cohabitors by race/ethnicity and education: trends and marital intentions in the United States. Demography. 2016;53(4):921–935. doi:10.1007/s13524-016-0483-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ventura SJ, Bachrach CA. Nonmarital childbearing in the United States, 1940-1999. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2000;48(16):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Monte LM. Fertility Research Brief. P70BR-147. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. NPRM: Paternity establishment provisions of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, OCSE-AT-93-14 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Division of Vital Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics. Report of the panel to evaluate the U.S. standard certificates 2000. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/panelreport_acc.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- 23. Mincy R, Garfinkel I, Nepomnyaschy L. In-hospital paternity establishment and father involvement in fragile families. J Marriage Family. 2005;67(3):611–626. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00157.x [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alio AP, Salihu HM, Kornosky JL, Richman AM, Marty PJ. Feto-infant health and survival: does paternal involvement matter? Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):931–937. doi:10.1007/s10995-009-0531-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): overview of design and methodology. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1305–1313. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. SAS-Callable SUDAAN [computer program]. Version 11.0 Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogran DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):618–623. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Callen J, Pinelli J. Incidence and duration of breastfeeding for term infants in Canada, United States, Europe, and Australia: a literature review. Birth. 2004;31(4):285–292. doi:10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scanlon KS, Grummer-Strawn L, Shealy KR, et al. Breastfeeding trends and updated national health objectives for exclusive breastfeeding—United States, birth years 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(30):760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin LT, McNamara M, Milot A, Bloch M, Hair EC, Halle T. Correlates of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(3):272–282. doi:10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bogart LM, Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Klein DJ. Effects of early and later marriage on women’s alcohol use in young adulthood: a prospective analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(6):729–737. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oesterle S, Hawkins JD, Hill KG. Men’s and women’s pathways to adulthood and associated substance misuse. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(5):763–773. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tokhi M, Comrie-Thomson L, Davis J, Portela A, Chersich M, Luchters S. Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191620 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]