Abstract

Voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels play a fundamental role in neuronal and cardiac excitability and are potential therapeutic targets. They assemble as tetramers with a centrally located pore domain surrounded by a voltage-sensing domain (VSD), which is critical for sensing transmembrane potential and subsequent gating. Although the sensor is supposed to be in “Up” conformation in both n-octylglucoside (OG) micelles and phospholipid membranes in the absence of membrane potential, toxins that bind VSD and modulate the gating behavior of Kv channels exhibit dramatic affinity differences in these membrane-mimetic systems. In this study, we have monitored the structural dynamics of the S3b-S4 loop of the paddle motif in activated conformation of KvAP-VSD by site-directed fluorescence approaches, using the environment-sensitive fluorescent probe 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl-ethylenediamine (NBD). Emission maximum of NBD-labeled loop region of KvAP-VSD (residues 110–117) suggests a significant change in the polarity of local environment in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) membranes compared to OG micelles. This indicates that S3b-S4 loop residues might be partitioning to membrane interface, which is supported by an overall increased mean fluorescence lifetimes and significantly reduced water accessibility in membranes. Further, the magnitude of red edge excitation shift (REES) supports the presence of restricted/bound water molecules in the loop region of the VSD in micelles and membranes. Quantitative analysis of REES data using Gaussian probability distribution function clearly indicates that the sensor loop has fewer discrete equilibrium conformational states when reconstituted in membranes. Interestingly, this reduced molecular heterogeneity is consistent with the site-specific NBD polarization results, which suggest that the membrane environment offers a relaxed/dynamic organization for most of the S3b-S4 loop residues of the sensor. Overall, our results are relevant for understanding toxin-VSD interaction and gating mechanisms of Kv channels in membranes.

Significance

Voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels are crucial for electrical and cellular signaling and are important therapeutic targets. The voltage-sensing domain (VSD) responds to change in membrane potential and leads to pore opening for K+ ion conduction. Many animal toxins bind to VSD (S3b-S4 paddle motif) and modulate the gating behavior of Kv channels. Using the isolated KvAP-VSD, we show that the organization and structural dynamics of S3b-S4 loop of the paddle motif is significantly different in membrane-mimetic systems. The physiologically relevant membrane environment not only offers dynamic organization but also appears to reduce the number of conformational states of the sensor loop when compared to micelles, which might be relevant for understanding toxin-VSD interaction and voltage-gating mechanisms of Kv channels.

Introduction

Voltage-gated ion channels are transmembrane proteins that conduct ions rapidly down their concentration gradient in response to changes in the membrane potential. They play a critical role in regulating a wide variety of physiological processes such as electrical signaling in species from bacteria to human, hormone secretion, osmotic balance, and cellular signaling (1, 2). These pore-forming proteins are important drug targets (3) and assemble as functional tetramers with a centrally located pore domain (helices S5 and S6) surrounded by a voltage-sensing domain (VSD). The VSD is an antiparallel four-helix bundle (S1–S4), containing a cluster of highly conserved positive charges (arginine residues) in the S4 helix (1, 4, 5, 6). Depolarization of the membrane induces a reorientation of these S4 gating charges within the transmembrane electric field (7). This structural rearrangement has long been associated with the transition from resting (“down”) conformation to the activated (“up”) conformation of the VSD and leads to pore opening through its mechanical coupling with the S4-S5 linker between domains (4, 5, 8).

The basic molecular architecture of all VSDs is based on a common scaffold as demonstrated by the crystal structures of the voltage-gated ion channels (KvAP, Kv1.2 and its chimera, Eag1, NavAb, and NavRh) (4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12), a cyclic nucleotide gated (MlotiK1) channel (13), voltage-gated proton (Hv1) channels (14), and the isolated sensor of a voltage-dependent enzyme, Ci-VSP, from Ciona intestinalis (15). These proteins emphasized the fact that the isolated VSDs are not exclusively associated with ion channels and can behave as autonomous structural and functional units (12, 16).

KvAP is a voltage-dependent K+ channel from archaebacterium Aeropyrum pernix and has been widely studied to understand the voltage-dependent gating mechanisms of voltage-dependent potassium (Kv) channels (4, 17, 18, 19, 20). The crystal structures of the full-length and the isolated VSD of KvAP have been determined in n-decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM) and n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) micelles, respectively, using monoclonal Fab fragments, which bind at the loop/turn connecting S3b to S4 in both cases (4, 18). Because the crystal structure of KvAP-VSD has been obtained in the absence of membrane potential, the isolated VSD of KvAP in detergent micelles is supposed to represent the “Up” state. Interestingly, it has been shown that the phosphate headgroup of phospholipid membranes is an absolute requirement for the normal functioning of KvAP and stabilizes the “Up” conformation of the KvAP sensor (21, 22). The KvAP sensor therefore adopts “Up” conformation in both OG micelles and phospholipid membranes (4, 19).

Notably, the voltage sensor paddle motif (S3b-S4 helix-turn-helix) is a conserved structural unit in voltage-dependent proteins (4, 16), and the S3b-S4 paddle motif of KvAP can functionally be transplanted to gate eukaryotic Kv channels (16). Further, the voltage sensor toxin 1 from spider venom (VSTX1) partitions into lipid membrane and interacts with the residues of the paddle motif, particularly G114, L115, and F116 in S3b-S4 loop, and inhibits KvAP (16, 23, 24). Importantly, it has been shown that there exists a 104-fold discrepancy between the dissociation constant for VSTX1 binding to KvAP in micelles to the toxin concentration that inhibits KvAP in membranes (23). This discrepancy probably indicates that the organization of the paddle motif in general and the S3b-S4 loop in particular is different in these membrane-mimetic systems. Understanding the structural dynamics of this important loop of the paddle motif in micelles and membranes therefore assumes significance.

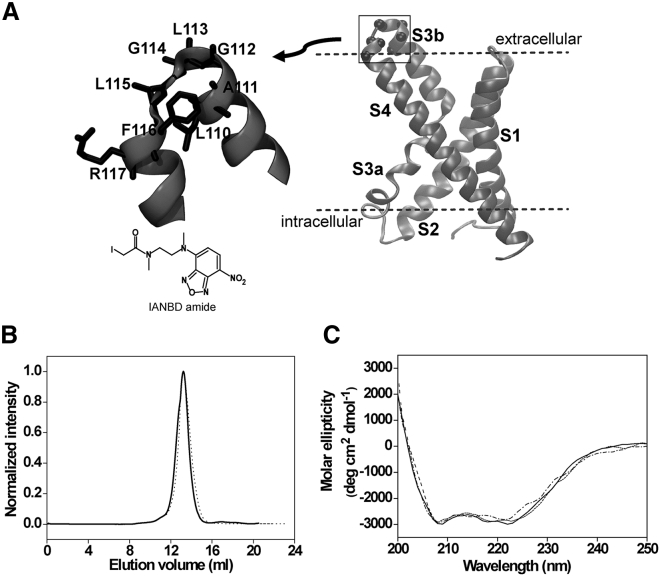

In this work, we have monitored the organization and dynamics of the S3b-S4 loop of the paddle motif of KvAP-VSD (Fig. 1 A) using site-specific labeling with an environment-sensitive fluorophore 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl (NBD) in OG micelles and PC/PG membranes. For this purpose, we have utilized various site-directed fluorescence approaches (25, 26) such as emission maximum, lifetime, polarization, red edge excitation shift (REES), and accessibility (quenching) studies in micelles and membranes. Our results show that the S3b-S4 loop residues partition at the membrane interface, and the structural dynamics of this physiologically important S3b-S4 loop is significantly altered in membrane environment. Overall, these results are relevant for understanding toxin-VSD interaction and gating mechanisms of Kv channels in membranes.

Figure 1.

The S3b-S4 loop of the isolated VSD of KvAP. (A) Shown is the cartoon representation of the isolated VSD of KvAP (PDB: 1ORS, chain C) with its four transmembrane segments (labeled S1–S4). Spheres represent the positions of single-cysteine mutants (residues 110–117) corresponding to the S3b-S4 loop, whose native amino acid residues are shown in stick representation in the enlarged view. The membrane boundaries are arbitrarily depicted as dashed lines. The chemical structure of the fluorophore IANBD amide, which has been used to label the protein, is also depicted. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) profiles of the unlabeled (solid line) and NBD-labeled (dotted line) L115C mutant of the sensor are shown. (C) Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the unlabeled wild-type KvAP-VSD (dotted line) and NBD-labeled 115 residue of KvAP-sensor in OG micelles (solid line) and when reconstituted in POPC/POPG (3:1 mol/mol) liposomes (dashed line) are shown. See Materials and Methods and text for other details.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Escherichia coli XL1-Blue strain was purchased from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA). DM and OG detergents were obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). Protease inhibitors were obtained from GoldBio (St. Louis, MO). 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (POPG) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). All other chemicals used were of the highest purity available from either Merck (Kenilworth, NJ) or Amresco (Radnor, PA).

Mutagenesis, channel expression, and purification

The DNA encoding the isolated VSD of KvAP was cloned into pQE70 expression vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Single-cysteine mutants were generated for residues 110–117, which corresponds to the S3b/S4 loop of the isolated sensor. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Wild-type and single-cysteine mutants of KvAP-VSD were expressed in XL1-Blue cells and purified as described earlier (4). The concentration of the protein was checked in a DS-11+ microvolume spectrophotometer (DeNovix, Wilmington, DE). To analyze whether the channel is folded properly, the purified protein (∼17 kDa) was applied onto a Superdex 75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) size-exclusion column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, 30 mM OG (pH 8.0) buffer.

Site-specific fluorescence labeling and membrane reconstitution

The purified single-cysteine mutants of KvAP-VSD were treated with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 h before labeling with IANBD amide (N,N′-dimethyl-N-(iodoacetyl)-N'-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)ethylenediamine), which is a thiol-reactive environment-sensitive fluorescent probe (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The excess DTT is removed by passing through a PD10 desalting column (GE Healthcare). After removing DTT, purified proteins in OG micelles were labeled with fluorophore at a 10:1 (fluorophore/sensor) molar ratio from a stock of 26 mM IANBD in dimethylsulfoxide and incubated overnight at 4°C. Excess NBD fluorophore was separated using a PD10 column. The labeling efficiency of the NBD-labeled single-cysteine mutants of KvAP-VSD were found to be more than 50% using the following equation:

| (1) |

where Ax is the absorbance of NBD at 478 nm and ε is the molar extinction coefficient of NBD at that wavelength (25,000 M−1 cm−1).

For reconstitution in liposomes, the wild-type and the labeled mutants of KvAP-VSD were reconstituted at a lipid/protein molar ratio of 100:1 in POPC/POPG (3:1) membranes. Briefly, 480 nmoles POPC and 160 nmoles of POPG (640 nmoles of total lipids) in chloroform were mixed well and dried under a stream of nitrogen while being warmed gently (∼35°C). After the lipids were dried further under a high vacuum for at least 3 h, they were hydrated (swelled) by adding 1 mL of 20 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl (pH 8.0) buffer and vortexed vigorously for 2 min to disperse the lipids and sonicated to clarity. Protein was then added to give a molar ratio of 100:1 lipid/VSD monomer. The sample was left at room temperature for 30 min on a rotator, then 200 mg of prewashed biobeads (SM-2; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were added, and the mixture was incubated on a rotator overnight at 4°C to remove the detergent. The biobeads were removed by filtering using a Bio-Rad 5 mL column filter before use (see Supporting Materials and Methods for details regarding reconstitution in nanodiscs).

CD measurements

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were carried out at room temperature in a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter (Easton, MD) purged with a nitrogen flow of 15 L/min. KvAP-VSD were measured at a concentration of 6.4 μM in 20 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, 30 mM OG (pH 8.0) buffer to obtain a good signal/noise ratio. The spectra were scanned with a quartz optical cuvette with a pathlength of 0.1 cm. All spectra were recorded with a bandwidth of 1 nm and integration time of 0.5 s with a scan rate of 50 nm/min. Each spectrum is the average of 10 scans. All spectra were appropriately blank subtracted and smoothed to ensure that the overall shape of the spectra remained unaltered. The ellipticity data obtained in millidegree were converted to molar ellipticity ([θ]) by using the following equation:

| (2) |

where θobs is the observed ellipticity in millidegrees, C is the concentration in moles per liter, and l is the pathlength in centimeters.

Steady-state fluorescence measurements

Steady-state fluorescence measurements were performed with a Hitachi F-7000 spectrofluorometer (Schaumburg, IL) using 1-cm pathlength quartz cuvettes. Excitation and emission slits with a nominal bandpass of 5 nm were used for all measurements. Background intensities were appropriately subtracted from each sample spectrum to cancel out any contribution due to the solvent Raman peak and other scattering artifacts. Fluorescence polarization measurements were performed at room temperature using Hitachi polarization accessory. Polarization values were calculated from the following equation (27):

| (3) |

where IVV and IVH are the measured fluorescence intensities (after appropriate background subtraction), with the excitation polarizer vertically oriented and emission polarizer vertically and horizontally oriented, respectively. G is the grating correction factor, is the ratio of the efficiencies of the detection system for vertically and horizontally polarized light, and is equal to IHV/IHH. The REES data were fitted by a Gaussian probability distribution in the form of the following equation (28):

| (4) |

where A is the area, w is the full width at half-maximum, m is the midpoint, R0 is the y-intercept, and m = , where is the excitation wavelength that gives the largest change in the emission peak wavelength.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence lifetimes were calculated from time-resolved fluorescence intensity decays using a picosecond pulsed LED-based time-correlated single-photon counting fluorescence spectrometer and microchannel plate photomutlipier tube as a detector. Lamp profiles were measured at the excitation wavelength using Ludox colloidal silica (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the scatterer. To optimize the signal/noise ratio, 10,000 photon counts were collected in the peak channel. All experiments were performed with a bandpass of 5–8 nm. Fluorescence intensity decay curves so obtained were deconvoluted with the instrument response function and analyzed as a sum of exponential terms in the following equation:

| (5) |

where F(t) is the fluorescence intensity at time t and αi is a preexponential factor representing the fractional contribution to the time-resolved decay of the component with a lifetime τi such that Σi αi = 1. Mean (average) lifetimes <τ> for triexponential decays of fluorescence were calculated from the decay times and preexponential factors using the following equation (27):

| (6) |

The mean fluorescence lifetime, τH, can be directly calculated using a model-independent approach from the histogram of photons obtained during fluorescence lifetime measurements using the following equation (29, 30):

| (7) |

where Ni and ti denote the number of detected photons in the ith channel and the corresponding value on the time axis, respectively, n is the total number of channels in the histogram, p is the channel with the highest number of detected photons (peak of the decay), and tp is the corresponding time.

Fluorescence quenching measurements

Collisional quenching experiments of NBD fluorescence in OG micelles and PC/PG membranes were carried out by measurement of fluorescence intensity of the KvAP-VSD loop residues after serial addition of small aliquots of a freshly prepared stock solution of 2.5 M potassium iodide (KI) with 1 mM Na2S2O3 in water to a stirred sample followed by incubation for 2 min in the sample compartment in the dark (shutters closed). The excitation wavelength used was 465 nm and emission was monitored at respective emission wavelengths. The fluorescence intensities were corrected for dilution. Corrections for inner filter effect were made using the following equation (27):

| (8) |

where F is the corrected fluorescence intensity and Fobs is the background-subtracted fluorescence intensity of the sample. Aex and Aem are the measured absorbance at the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. The absorbance of the samples was measured using a Jasco V-650 ultraviolet (UV)-visible absorption spectrophotometer. Quenching data were analyzed by fitting to the following Stern- Volmer equation (27):

| (9) |

where Fo and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of the quencher, respectively, KSV is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant, and [Q] is the molar quencher concentration. The Stern-Volmer quenching constant KSV is equal to kqτo, where kq is the bimolecular quenching constant and τo is the lifetime of the fluorophore in the absence of quencher.

Results

Structural integrity of KvAP-VSD is preserved upon NBD labeling

The S3b-S4 loop residues (110–117) of the paddle motif of the isolated VSD of KvAP are labeled with thiol-reactive NBD fluorophore (Fig. 1 A). NBD is chosen because it is uncharged and has relatively small size for a fluorophore, excitation at visible range, and its environment-sensitive fluorescence (31, 32, 33, 34). The imino group and the oxygen atoms may form hydrogen bonds with the lipid carbonyls, interfacial water molecules, and the lipid headgroup. The N and O atoms give sufficient polar character to NBD to be soluble in an aqueous environment. This is extremely important because it makes NBD a suitable stable reporter group in both aqueous and nonaqueous environments (26, 31, 35). To confirm that the NBD labeling of the S3-S4 loop does not affect the structural integrity of the sensor, we carried out size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) of all the labeled mutants. Both wild-type and the NBD-labeled analogs of VSD (L115-NBD is shown as representative) exhibit a similar SEC profile (Fig. 1 B), confirming the monomeric configuration of the sensor in OG detergent micelles (4, 19, 20). In addition, far-UV CD spectra (Fig. 1 C) reveal that the wild-type KvAP sensor is predominantly α-helical in OG detergent micelles as well as when reconstituted in POPC/POPG (3:1 mol/mol) liposomes as shown previously (36). This is consistent with the x-ray structure of the S1-S4 domain of KvAP (4, 18) and electron paramagnetic resonance studies (17, 20). Importantly, all the NBD-labeled mutants of KvAP-VSD (L115-NBD is shown as representative) have similar α-helical content compared to wild-type sensor (Fig. 1 C), suggesting that the α-helical bundle structure of VSD does not appear to be sensitive to NBD labeling. Taken together, these results suggest that NBD-labeled VSD analogs are structurally similar to wild-type KvAP-VSD and therefore could be used to monitor the structural dynamics of the S3b-S4 loop residues in membrane-mimetic systems.

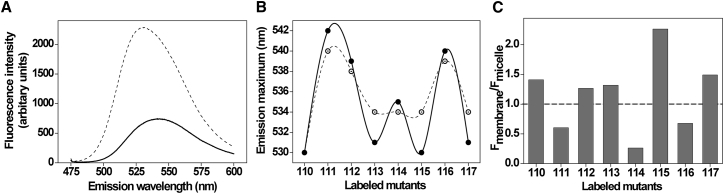

Probe environment of sensor loop residues in micelles and membranes

It is well established that NBD is weakly fluorescent in water, fluoresces brightly in the visible range upon transfer to a hydrophobic medium, and exhibits a high degree of environmental sensitivity (32, 33, 34), which has been widely used to monitor the dynamics of membranes (35, 37) and membrane proteins (see (25, 26) for reviews; (31, 38, 39, 40)). Further, it is known that depending on temperature, the fluorescence emission maximum of NBD is 517–522 and 530–535 nm when placed in the hydrophobic core (35) and in the interfacial region of the membrane (37), respectively. Fig. 2 A shows the representative emission scans of two S3b-S4 loop residues in PC/PG membranes to highlight the differences in probe environment. The fluorescence emission maximum of L110-NBD is 530 nm in both membrane-mimetic systems (see Fig. 2 B), which suggests that the microenvironment experienced by this residue is similar in micelles and membranes. In micelles, the emission maximum of the NBD-labeled sensor loop residues 111–117 is in the range of 534–540 nm. Interestingly, for the same residues of the sensor, the fluorescence emission maximum of NBD is in the range of 530–542 nm upon membrane incorporation, suggesting that the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor experiences heterogeneous environment in membranes. Significant blue shifts (3–4 nm) are observed for NBD-labeled residues 113, 115, and 117 in membranes, indicating that the sensor loop partitions into relatively nonpolar/hydrophobic environment in membranes when compared to its organization in micelles. This is supported by an increase in fluorescence intensity of NBD in membranes for most of the residues of the S3b-S4 loop of KvAP-VSD (Fig. 2 C). Taken together, our results clearly indicate that the environmental polarity around the loop residues of the sensor is significantly altered in micelles and membranes, which could be attributed to the partitioning of this region of the sensor at the membrane interface.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence emission maximum of the NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop residues in membrane-mimetic systems. (A) Representative fluorescence emission spectra of A111-NBD (solid line) and R117-NBD (dashed line) in POPC/POPG membranes are shown. (B) Shown are the fluorescence emission maximum of NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop residues in micelles (open circles) and POPC/POPG membranes at a protein/lipid molar ratio of 1:100 (solid circles). (C) Changes in emission intensity of NBD (Fmembrane/Fmicelle) for residues in the paddle motif loop observed at respective emission maximum are shown. The excitation wavelength used was 465 nm and the concentration of KvAP-VSD was 6.4 μM in all cases. The lines joining the data points are provided merely as viewing guides. See Materials and Methods for other details.

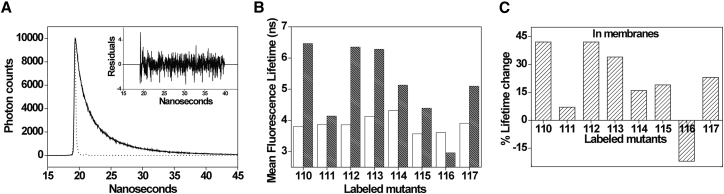

Changes in emission intensity may not always be a reliable parameter to monitor the location of probes because of its composite property that is dependent on several factors (27, 31, 41). Because fluorescence lifetime is an intrinsic property of the probe and serves as a faithful indicator of the local environment (42), we therefore measured fluorescence lifetimes of NBD-labeled sensor loop. Because the fluorescence lifetime of NBD group is sensitive to its local environment (32, 34), the magnitude of lifetime can directly reveal the environment of the probe and in particular its exposure to water (38). For instance, the fluorescence lifetimes of NBD in membranes are in the range of ∼5–10 ns (35, 37); however, it dramatically decreases to ∼1.5 ns upon complete exposure to aqueous medium (32, 38, 39). A typical decay profile of G112-NBD in PC/PG membranes with its triexponential fitting and the statistical parameters to check the goodness of fit is shown in Fig. 3 A. The intensity-weighted mean fluorescence lifetimes, <τ>, of NBD-labeled loop residues in micelles and membranes are shown in Fig. 3 B and Table 1. The fluorescence lifetime of NBD is ∼4 ns for all the residues in the sensor loop in OG micelles with only modest variation in lifetimes. In case of VSD in membranes, the lifetimes for the S3b-S4 loop are in the range of ∼3–7 ns, which suggests that the loop is localized in environments of heterogeneous polarity. Interestingly, most of the membrane-incorporated loop residues of the sensor show significant increase (>15%) in NBD lifetimes, and some of them (residues 110, 112, and 113) even show >30% increase in lifetimes (see Fig. 3 C). Considering the mean fluorescence lifetimes of residues 110, 112, and 113 are >6 ns, it is a clear indication that these residues partition in the nonpolar region of the membrane. It is interesting to note that F116-NBD is the only residue in the loop whose lifetime is significantly shorter in membranes when compared to its corresponding value in micelles. The decreased lifetime of F116-NBD in membranes could be attributed to either increased exposure of this residue to aqueous environment or due to the presence of a nearby charged residue (R117) that can act as a quencher of NBD fluorescence and facilitate the decay process. We believe the latter is applicable in this case because the water penetration around this residue is significantly decreased in membranes compared to micelles (see later).

Figure 3.

Fluorescence lifetimes of NBD-labeled loop residues in micelles and membranes. (A) Time-resolved fluorescence intensity decay of G112-NBD (solid line) in POPC/POPG membranes is shown. Excitation wavelength was 465 nm, and emission was monitored at 538 nm. The sharp peak on the left (dotted line) is the lamp profile, and the relatively broad peak on the right is the decay profile (solid line), fitted to a triexponential function. The plot in the inset shows the weighted residuals of the decay fit. (B) Mean fluorescence lifetimes for NBD-labeled mutants (residues 110–117) in micelles (white bars) and membranes (shaded bars) are shown. (C) The effect of membrane environment on the lifetimes of sensor loop residues depicted as percent of lifetime changes is shown. All other conditions are as in Fig. 2. See Materials and Methods and Table 1 for other details.

Table 1.

Fluorescence Lifetimes of NBD-Labeled S3b-S4 Loop Residues of KvAP-VSD

| α1 | τ1 (ns) | α2 | τ2 (ns) | α3 | τ3 (ns) | <τ> nsa | τH nsb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OG Micelles | ||||||||

| L110 | 0.51 | 1.87 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 5.25 | 3.81 | 2.84 |

| A111 | 0.45 | 1.75 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 5.26 | 3.87 | 2.53 |

| G112 | 0.51 | 1.72 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 5.17 | 3.86 | 2.66 |

| L113 | 0.51 | 1.72 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 5.44 | 4.13 | 2.85 |

| G114 | 0.44 | 2.04 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 5.42 | 4.32 | 3.21 |

| L115 | 0.57 | 1.43 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 4.87 | 3.57 | 2.48 |

| F116 | 0.50 | 1.36 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 4.74 | 3.61 | 2.32 |

| R117 | 0.51 | 1.78 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 5.07 | 3.91 | 2.91 |

| PC/PG Membranesc | ||||||||

| L110 | 0.44 | 3.69 | 0.48 | 7.92 | 0.09 | 1.26 | 6.55 | 5.77 |

| A111 | 0.48 | 1.72 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 5.48 | 4.14 | 2.68 |

| G112 | 0.41 | 2.49 | 0.49 | 7.85 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 6.64 | 5.40 |

| L113 | 0.35 | 2.28 | 0.57 | 7.11 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 6.28 | 5.05 |

| G114 | 0.38 | 2.37 | 0.49 | 6.10 | 0.13 | 0.65 | 5.13 | 4.05 |

| L115 | 0.40 | 2.04 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 5.13 | 4.39 | 3.70 |

| F116 | 0.52 | 1.35 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 4.06 | 2.96 | 2.13 |

| R117 | 0.40 | 2.35 | 0.10 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 6.07 | 5.10 | 4.08 |

The concentration of protein was 6.4 μM in all cases. The excitation wavelength was 465 nm, and the emission was monitored at respective emission maximum. See Materials and Methods for other details.

Mean fluorescence lifetime (<τ>) calculated using Eq. 6.

Calculated using Eq. 7.

The ratio of KvAP/total lipid is 1:100.

The overall trend of increased lifetime in membranes is in agreement with the blue-shifted emission maximum and intensity changes (see above) and, as expected, the fluorescence lifetime values show better sensitivity of the probe environment. This clearly shows that the loop residues of the sensor are relatively exposed to aqueous environment in micelles, whereas they possibly partition in an environment of intermediate polarity (i.e., the membrane interface) in membranes. The observed differences in environmental polarity around the S3b-S4 loop of KvAP-VSD in micelles and membranes strongly suggest the altered organization of the sensor loop in physiologically relevant membranes. Apart from conventional calculation of mean fluorescence lifetimes, we have also calculated the NBD fluorescence lifetimes (τH), obtained from the histogram of photons counted during the measurement using Eq. 7 (Table 1), using a recently developed model-independent approach (29, 30). Obviously, model-dependent and model-independent analyses of lifetimes yield different values of lifetimes. Irrespective of the method of analysis to obtain NBD lifetimes, the conclusions derived from time-resolved measurements remain the same.

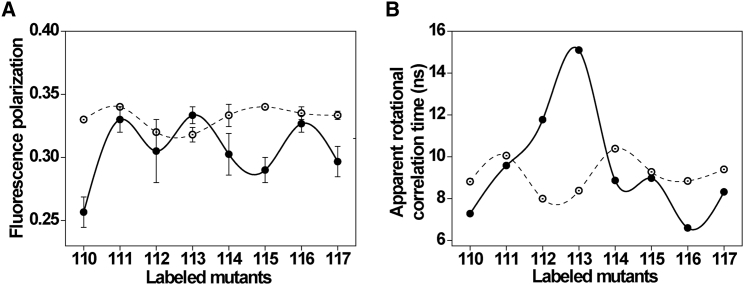

Rotational dynamics of the NBD-labeled loop residues of VSD

Fluorescence polarization is a powerful approach to obtain information about the molecular flexibility and rotational motion of a fluorophore and has been used to monitor the dynamic behavior of ion channels (40, 43). The steady-state fluorescence polarization values of NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop residues in OG micelles and PC/PG membranes in general indicate that the rotational mobility of NBD group of NBD-labeled sensor loop is considerably restricted and are representative of motionally restricted environments of NBD (Fig. 4 A). It should be noted that the hydrodynamic diameter of OG micelles is ∼6 nm (44), whereas the diameter of small unilamellar liposomes is ∼40 nm (45). Being smaller, micelles will have more curvature and might have interfacial packing defects that will lead to reduced order parameter when compared to liposomes (46). If this is the case, one would expect increased dynamics for the sensor loop residues incorporated in micelles that will result in low polarization values. However, micelle-embedded sensor displays higher polarization values than PC/PG liposomes and do not show appreciable changes for the loop residues, indicating a similar motional restriction throughout the loop region of the sensor. Interestingly, in the membrane environment, the sensor paddle loop not only displays low polarization values but exhibits significant dynamic variability (Fig. 4 A), which suggests that the sensor loop is highly dynamic in membranes. The periodic pattern of dynamic variability in membranes is consistent with the results obtained from the fluorescence emission maximum (Fig. 2, B and C) and lifetime measurements (Fig. 3 B). These results clearly suggest that the membrane environment offers a dynamic (relaxed) organization of the VSD sensor loop and rules out the effect of curvature on its conformational dynamics (see also Fig. S1).

Figure 4.

Rotational mobility of NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop residues in micelles and membranes. Steady-state fluorescence polarization of NBD fluorescence (A) and apparent rotational correlation times of the NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop residues (B) in OG micelles (open circles) and POPC/POPG membranes (solid circles) are shown. The error bars represent the means ± standard error of three independent measurements. The lines joining the data points are provided merely as viewing guides. All other conditions are as in Fig. 2. See Materials and Methods for other details.

As discussed above, the lifetime changes are more pronounced especially for the loop residues in membranes. To ensure that the polarization values measured for the NBD-labeled loop residues of KvAP-VSD are not influenced by lifetime-induced artifacts, the apparent (average) rotational correlation times were calculated using Perrin’s equation (27):

| (10) |

where ro is the limiting anisotropy of NBD, r is the steady-state anisotropy (derived from the polarization values using r = 2P/(3−P)), and <τ > is the mean fluorescence lifetime taken from Table 1. The apparent rotational correlation times, calculated this way, using an ro value of 0.354 (37) are shown in Fig. 4 B. As can be seen from the figure, the rotational correlation time, on average, for the loop residues of the sensor in micelles is ∼9 ns, whereas the corresponding values in membranes are 7–15 ns, highlighting that the S3b-S4 loop region of the sensor exhibits high dynamic variability in membranes, consistent with the electron paramagnetic resonance results (19). This shows that the observed changes in fluorescence polarization values are more or less free from lifetime-induced artifacts. The nature of changes in rotational dynamics further suggests that the structural organization of the S3b-S4 loop region of the sensor is significantly altered in membranes, which is in agreement with previous results obtained in BK channels (47).

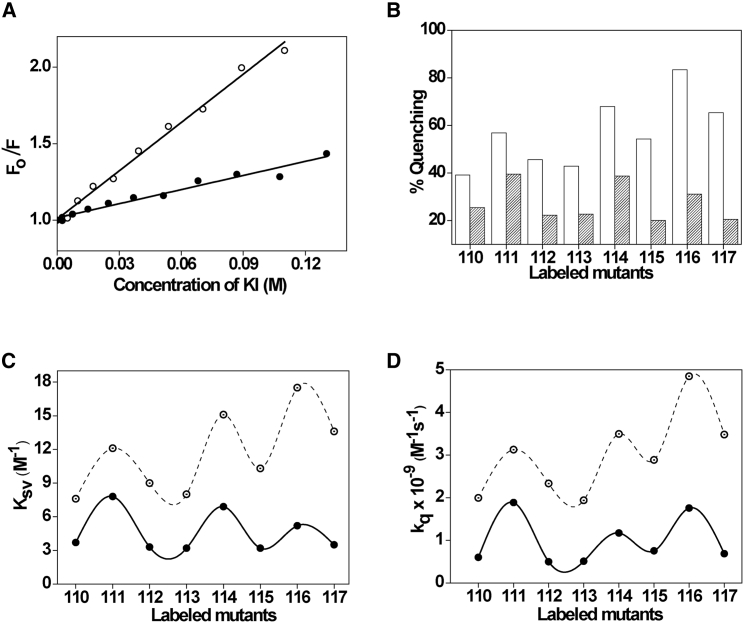

Collisional quenching of NBD fluorescence by iodide ions

The above results show that the S3b-S4 loop of VSD experiences relatively nonpolar environment in membranes compared to micelles because of its partitioning in the membrane interface. We performed fluorescence quenching measurements using the aqueous quencher KI to explore this issue further and to probe the water accessibility and relative location of the sensor loop in micelles and membranes. The water soluble iodide ion (I−) is an efficient quencher of NBD fluorescence and has been extensively used to monitor topology of membrane proteins (31, 48). Representative results for quenching of L115-NBD in OG micelles and PC/PG membranes by I− are shown in Fig. 5 A as Stern-Volmer plots. The slope of such a plot (KSV) is related to the degree of exposure (accessibility) of the NBD group to the aqueous phase. In general, the higher the slope, the greater the degree of exposure to water (in our case) assuming that the difference in fluorescence lifetime is not large. Our results show that I− ions quench NBD fluorescence more effectively when the sensor is present in micelles than in membranes. This is reflected by ∼40–80% quenching of NBD fluorescence of loop residues observed in OG micelles compared to significantly lower quenching efficiency (∼20–40%) when the sensor is in membrane environment at the quencher concentration of 0.1 M (Fig. 5 B). The KSV values indeed are considerably higher in micelles than in membranes (Fig. 5 C). However, the interpretation of KSV values is complicated because of its intrinsic dependence on fluorescence lifetime (see Eq. 9) and, in our case, do not accurately reflect the relative collisional rates because the NBD lifetimes, particularly in membranes, change considerably (see Fig. 3 C). The bimolecular quenching constant (kq) is a more accurate measure of the degree of exposure because it takes into account the differences in fluorescence lifetime. It is encouraging to note that the calculated kq values (Fig. 5 D) are significantly lower (i.e., low accessibility to water) in membranes (∼0.5–2 M−1ns−1) compared to micelles (∼2–5 M−1ns−1), which is in excellent agreement with KSV values. Considering the complete exposure of NBD to aqueous environment has a kq value of ∼8 M−1ns−1 (39), the loop region of the sensor is partially exposed to water in micelles. Taken together, our results clearly demonstrate the decreased water accessibility in the S3b-S4 loop region of the sensor in membranes and strongly supports the partitioning and interfacial localization of this important region of the sensor in membranes.

Figure 5.

Water accessibility probed by iodide quenching of NBD fluorescence. (A) Representative data for Stern-Volmer analysis of KI quenching in micelles (open circles) and membranes (solid circles) for L115-NBD of KvAP-VSD are shown. Fo is the fluorescence intensity in absence of quencher, and F is the corrected fluorescence intensity in the presence of quencher. The excitation wavelength was 465 nm and emission was monitored at 530 nm. (B) Quenching of NBD fluorescence of the labeled loop residues at 0.1 M KI in micelles (white bars) and membranes (shaded bars) is shown. Shown are (C) Stern-Volmer constants (KSV) and (D) bimolecular quenching constants (kq) for iodide quenching of NBD-labeled residues in micelles (open circles) and membranes at a protein/lipid molar ratio of 1:100 (solid circles). The lines joining the data points are provided merely as viewing guides. The excitation wavelength used was 465 nm and the emission was monitored at respective emission maximum. The concentration of KvAP-VSD was 1.6 μM in all cases. See Materials and Methods for other details.

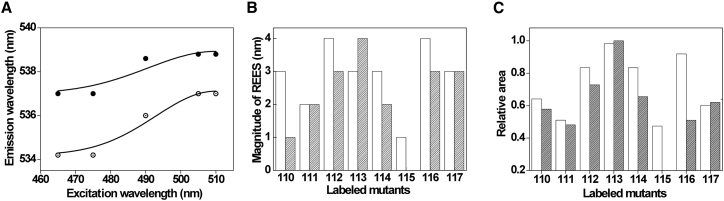

REES as a tool to monitor hydration dynamics and S3b-S4 loop heterogeneity

Hydration and dynamics play an important role in lipid-protein interactions (38) and ion channel selectivity (49) because protein fluctuations, slow solvation, and the dynamics of hydrating water are all intrinsically related (50). REES represents a unique and powerful approach that can be used to directly monitor the environment-induced restriction and dynamics around a fluorophore in a complex biological system (see (51, 52, 53, 54) for reviews). Because REES provides information on the relative rates of water relaxation dynamics, this approach is sensitive to changes in local hydration dynamics (34, 55). Recently, REES has been shown to provide unique information on protein conformational change and the equilibrium of conformational substates (28).

REES is operationally defined as the shift in the wavelength of maximum fluorescence emission toward higher wavelengths, caused by a shift in the excitation wavelength toward the red edge of the absorption band. The shifts in the maxima of fluorescence emission of G114-NBD of the sensor loop in micelles and membranes as a function of excitation wavelength are shown in Fig. 6 A. The magnitude of REES, that is, the total shift in fluorescence emission maximum upon changing the excitation wavelength from 465 to 510 nm, for all the NBD-labeled loop residues in micelles and membranes is shown in Fig. 6 B. In general, the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor exhibits significant REES (except L115 in membranes), an indication of a motionally restricted environment in both micelles and membranes and the presence of restricted/bound water molecules. Using the REES approach, it has been shown that restricted/bound water molecules play a significant role in C-type inactivation gating of KcsA potassium channel (40). Further, the magnitude of REES (0–4 nm) suggests that there is considerable difference in the relaxation of solvent molecules (dynamics of hydration) ranging from freely relaxing to fully restricted environments in different positions of the S3b-S4 loop. Most of the loop residues in membranes have lesser magnitude of REES magnitude compared to micelles, suggesting that the loop region of the sensor in the membrane experiences less motional restriction imposed by solvent molecules. It is interesting to note that the changes in hydration dynamics of the sensor loop in micelles and membranes are not solely due to changes in the polarity of the local microenvironment. For example, the fluorescence emission maximum is ∼530 nm for the loop residues 110, 113, 115, and 117 in membranes, but the magnitude of REES varies from 0 to 4 nm. Because the loop region experiences less environmental restriction, this result also suggests a relatively fast motion of the loop region of the sensor in membranes and is in agreement with the differential mobility of the S3b-S4 loop observed in micelles and membranes (see Fig. 4). As mentioned before, the observed differences between OG micelles and PC/PG liposomes could be related to changes in the intrinsic curvature (and hence interfacial packing defects) of these membrane-mimetic systems. However, we believe this is not the case because the fluorescence properties (emission maximum and REES) of NBD-labeled mutant at position 117 of KvAP-VSD remain unaffected upon incorporation in PC/PG nanodiscs (see Fig. S1), which are novel, to our knowledge, discoidal membrane-mimetic systems in which the lipids are arranged in a bilayer form with negligible curvature. This rules out the possibility of curvature-mediated effects in the observed changes in the structural dynamics of S3b-S4 loop of the sensor. Overall, our results clearly show that not only the S3b-S4 sensor loop is highly dynamic in membranes, but also the microenvironment associated with the sensor loop displays faster relaxation.

Figure 6.

Red edge excitation shift (REES) of NBD-labeled loop residues of KvAP-VSD. (A) The effect of changing excitation wavelength on the wavelength of maximum emission for G114-NBD in micelles (open circles) and POPC/POPG membranes (solid circles) is shown. The solid lines are the fit to Eq. 4. The magnitude of REES (B) and the relative area (C) calculated by fitting the REES data using Eq. 4 for all the labeled loop residues in micelles (white bars) and membranes (shaded bars) are shown. All other conditions are as in Fig. 2. See Materials and Methods for other details.

Although the magnitude of REES is a very good qualitative measure to monitor relative solvent relaxation dynamics, the area extracted from the distinct curvature of REES data using the Gaussian probability distribution can be used to reflect changes in the equilibrium of protein conformational states (28). We have fitted our REES data with Eq. 4 (see Fig. 6 A) to extract the relative area of the distribution for the NBD-labeled loop residues of VSD in both micelles and membranes and are shown in Fig. 6 C. The relative area is not plotted for labeled L115 residue of the sensor in membranes because it does not exhibit any REES. Our results show that the relative area, in general, for membranes is relatively low, and significant reduction in relative area is obtained particularly for NBD-labeled 114 and 116 residues. This indicates that the loop region of the sensor probably has fewer conformational states in a membrane setup. Taken together, our results are strongly in favor of significant differences in the structural organization and dynamics of the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor in these membrane-mimetic systems.

Discussion

Biological membranes, which are complex assemblies of lipids and proteins, constitute the site for many important cellular functions such as organizing functional membrane domains, ion transport, signal transduction, energy metabolism, and modulating various cellular signaling pathways (56). Membrane lipids play an important role in modulating the structure and function of various membrane proteins particularly because of their specific high-affinity binding (57, 58). The critical dependence of proteins on the chemical nature of the lipid bilayer suggests that the two might have coevolved (59). Moreover, local lipid composition has an influence on the topology and conformation of the voltage sensor in a voltage-independent manner (22). For instance, it has been shown that lipid phosphate headgroups are critical for the normal functioning of voltage-dependent potassium channels (21, 22, 60, 61). Indeed, nonphosphate-containing lipids have been shown to stabilize the resting/down conformation of the voltage sensor in KvAP voltage-dependent potassium channel (21, 22, 62). These studies clearly demonstrate the importance of lipid-protein interactions in membranes for the functioning of voltage-gated ion channels.

However, despite the importance of lipid-protein interactions for the proper functioning of membrane proteins, the high-resolution structure determination of membrane proteins is often carried out in detergent micelles, and in many cases, with the help of monoclonal antibodies (63). Although detergent micelles provide a mimic of the lipid environment, they have been shown to adversely affect the structure, stability, dynamic behavior, and shift the equilibrium of functional conformational states in several membrane proteins such as potassium channels KcsA (64) and KvAP (65), β2-adrenergic receptor (66), human voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (67), and Omp X (68).

Voltage-gated ion channels are crucial for maintaining the electrical excitability of cells and are also involved in chemical signaling. Even subtle mutations in voltage-gated ion channels lead to drastic changes in their functional behavior and underlie many genetically inherited pathological conditions (1). The first crystal structures of the voltage-gated ion channels have been determined for prokaryotic Kv channel KvAP (4, 18). The isolated VSD of KvAP has been studied as a model system to understand the voltage sensor movement and gating mechanism of Kv channels (20). This is because the VSD (S1–S4 helical bundle) is a portable domain and its basic architecture is common to various voltage-sensing proteins. Particularly, the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor constitutes an important region of the channel because it modulates the gating kinetics when mutated or deleted (69) and alters the equilibrium between resting and activated conformations (70). In addition, many animal toxins target the S3b-S4 paddle motif of the sensor and modulate the gating of Kv channels (71). As mentioned earlier, although the KvAP sensor is supposed to have same conformation in both micelles and phospholipid membranes, toxins that bind the paddle motif of KvAP-VSD and modulate the gating behavior exhibit dramatic affinity differences in these membrane-mimetic systems (23).

Our site-directed fluorescence approaches on NBD-labeled S3b-S4 loop region of the paddle motif of the sensor (residues 110–117) clearly demonstrate the altered organization of this crucial region of the sensor in membrane-mimetic systems. We observe significant dynamic variability of the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor in POPC/POPG membranes, which appears to be suppressed in OG micelles (see Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Because we used OG micelles, which is nonionic, and PC/PG liposomes that have negatively charged PG lipids, the altered organization of the loop region of the sensor in membranes might have been influenced by the possible interaction of anionic lipids with the positively charged R117 residue of the sensor. We have performed fluorescence measurements of a NBD-labeled loop mutant (at position 115) of KvAP-VSD reconstituted in zwitterionic POPC membranes and compared the results with anionic (PC/PG) membranes. The choice of monitoring NBD fluorescence at position 115 of the loop allows the influential interaction, if any, of R117 with anionic lipids. As can be seen from Table S1, all the measured fluorescence parameters, which include emission maximum, polarization, magnitude of REES, and quenching constants, are very similar in both zwitterionic and anionic membranes. This clearly indicates that the altered organization of the sensor loop in membranes is not predominantly governed by the specific interaction of anionic lipid with the sensor.

Overall, our results support the partitioning of S3b-S4 loop residues of the sensor at the membrane interface, which agrees well with the hydrophobic nature of this loop residues (except mainly R117). The interfacial region of the membrane is a chemically heterogeneous environment that is characterized by unique motional and dielectric characteristics distinct from the bulk aqueous phase and the hydrocarbon-like interior of the membrane (72). This is supported by a significant reduction in polarity of the immediate environment, increased NBD emission intensity and lifetimes, and reduction in water accessibility in most residues of the loop region in PC/PG membranes when compared to micelles. Considering the functional correlations of hydration and conformational dynamics in inactivating and conductive conformations of K+ channels (40, 73, 74), our results showing the presence of restricted/bound water molecules in the immediate vicinity of the loop region might also be relevant for the sensor function. Quantitative analysis of REES data using Gaussian probability distribution function indicates that the sensor loop possibly has fewer discrete equilibrium conformational states in membranes compared to its organization in micelles. This is consistent with our site-specific NBD mobility measurements, which suggest that the membrane environment offers a relaxed/dynamic organization for most of the S3b-S4 loop residues of the sensor. Our results of the dynamic nature of the sensor loop in membranes are in agreement with the recent studies on OmpX backbone dynamics in various membrane-mimetic systems (68) and human voltage-dependent anion channel (67).

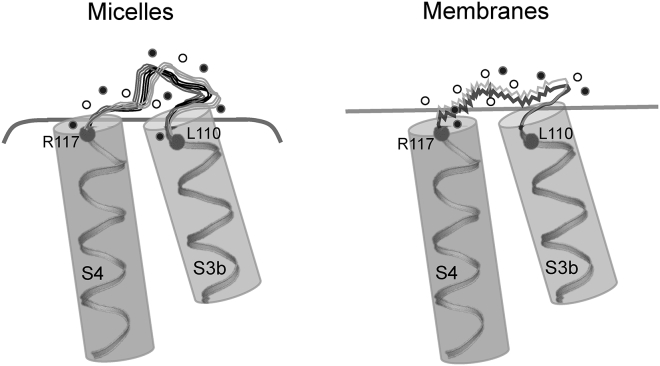

Based on our results, we propose a model (Fig. 7) that highlights the key differences in the organization and dynamics of the S3b-S4 sensor loop in micelles and membranes. The sensor loop residues partition into a considerable nonpolar environment, that is, at the interfacial region of the membranes. In addition, the sensor loop exhibits high dynamic variability in membranes compared to a relatively rigid organization of the sensor in micellar environment. This is accompanied by relatively fast solvent relaxation dynamics around the sensor and the presence of fewer possible conformational substates in membranes. These membrane-environment-induced changes in the organization of the sensor loop might be responsible for the dramatic differences observed in VSTX1 binding affinity to KvAP-VSD in micelles and membranes. Despite being a positively charged residue, the first gating charge of KvAP-VSD (R117) appears to be shielded from complete exposure to water in both micelles and membranes and, interestingly, the shielding is more pronounced in membranes in which R117 presumably interacts with membrane lipids as suggested earlier (19, 20). Overall, our results bring out the importance of the membrane environment in the organization and dynamics of S3b-S4 loop region of VSD, which might be relevant for the voltage-gating mechanisms and the effect of toxins on the modulation of sensor function.

Figure 7.

Membrane-induced conformational dynamic variability of the voltage sensor loop. A schematic representation of the key differences in the organization and dynamics of S3b-S4 loop residues of KvAP-VSD in OG micelles (left) and in PC/PG membranes (right) is shown. Only a part of the S3b and S4 helices are shown, and the positions of residues 110 and 117 are indicated by spheres (Cα atoms) in helices. Because of increased hydrophobicity of the loop region, most of the loop residues partition in relatively nonpolar environment in membranes compared to micelles. Further, the S3b-S4 loop region exhibits pronounced dynamic variability in membranes as depicted by the wiggly nature of the loop (right). In contrast, the micellar environment imposes motional restriction and induces an increased number of discrete conformational substates of the loop region as denoted by more copies of the loop region (left). Changes in hydration dynamics are depicted by the increased ratio of bulk/free (open circles) versus restricted/bound (solid circles) water molecules. The curved and straight lines denote the arbitrary micellar and membrane boundaries, respectively. See Discussion for more details.

Conclusion

As mentioned earlier, the basic molecular architecture of all VSDs is based on a common scaffold as demonstrated by the crystal structures of voltage-sensing proteins. In the absence of membrane potential, the purified KvAP-VSD is supposed to be in “Up” conformation in both micelles and when incorporated in membranes. However, we find significant differences in the conformational dynamics of the S3b-S4 loop of the sensor in micelles and membranes. Considering the fact that all VSDs have common scaffold, and gating-modifier toxins target S3b-S4 paddle motif of VSDs in Kv, Nav, and Cav channels, our results related to the pronounced variability in the structural dynamics of this critical loop region of the paddle motif in membranes will be relevant to understand the toxin-sensor interaction and voltage-dependent gating mechanisms.

Author Contributions

H.R. and A.D. designed research. A.D. and S.C. performed experiments. A.D., S.C., and H.R. analyzed data. A.D. and H.R. wrote the manuscript. H.R. supervised the work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the chemical sciences division for providing generous access to steady-state and time-resolved spectrofluorometers.

This work was supported by the Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India, and Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. H.R. thanks DST-Science and Engineering Research Board for the Early Career Research Award (ECR/2016/001056). A.D. and S.C. thank the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India, for the award of a Senior Research Fellowship, respectively.

Editor: Sudha Chakrapani.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.08.017.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Catterall W.A. Ion channel voltage sensors: structure, function, and pathophysiology. Neuron. 2010;67:915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser S.P., Ozerlat-Gunduz I., Djamgoz M.B. Regulation of voltage-gated sodium channel expression in cancer: hormones, growth factors and auto-regulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20130105. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wulff H., Castle N.A., Pardo L.A. Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:982–1001. doi: 10.1038/nrd2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y., Lee A., MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezanilla F. How membrane proteins sense voltage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:323–332. doi: 10.1038/nrm2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swartz K.J. Sensing voltage across lipid membranes. Nature. 2008;456:891–897. doi: 10.1038/nature07620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long S.B., Tao X., MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tombola F., Pathak M.M., Isacoff E.Y. How does voltage open an ion channel? Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;22:23–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020404.145837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whicher J.R., MacKinnon R. Structure of the voltage-gated K+ channel Eag1 reveals an alternative voltage sensing mechanism. Science. 2016;353:664–669. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A. The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2011;475:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Ren W., Yan N. Crystal structure of an orthologue of the NaChBac voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2012;486:130–134. doi: 10.1038/nature11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islas L.D. Functional diversity of potassium channel voltage-sensing domains. Channels (Austin) 2016;10:202–213. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2016.1141842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayton G.M., Altieri S., Morais-Cabral J.H. Structure of the transmembrane regions of a bacterial cyclic nucleotide-regulated channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1511–1515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711533105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeshita K., Sakata S., Nakagawa A. X-ray crystal structure of voltage-gated proton channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q., Wanderling S., Perozo E. Structural mechanism of voltage-dependent gating in an isolated voltage-sensing domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:244–252. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alabi A.A., Bahamonde M.I., Swartz K.J. Portability of paddle motif function and pharmacology in voltage sensors. Nature. 2007;450:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nature06266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuello L.G., Cortes D.M., Perozo E. Molecular architecture of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2004;306:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1101373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S.Y., Lee A., MacKinnon R. Structure of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel and its dependence on the lipid membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15441–15446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakrapani S., Cuello L.G., Perozo E. Structural dynamics of an isolated voltage-sensor domain in a lipid bilayer. Structure. 2008;16:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q., Wanderling S., Perozo E. Structural basis of lipid-driven conformational transitions in the KvAP voltage-sensing domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:160–166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt D., Jiang Q.X., MacKinnon R. Phospholipids and the origin of cationic gating charges in voltage sensors. Nature. 2006;444:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nature05416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H., Liu W., Jiang Q.X. Lipid-dependent gating of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:250. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S.Y., MacKinnon R. A membrane-access mechanism of ion channel inhibition by voltage sensor toxins from spider venom. Nature. 2004;430:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature02632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau C.H.Y., King G.F., Mobli M. Molecular basis of the interaction between gating modifier spider toxins and the voltage sensor of voltage-gated ion channels. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34333. doi: 10.1038/srep34333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghuraman H., Chatterjee S., Das A. Site-directed fluorescence approaches for dynamic structural biology of membrane peptides and proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson A.E. Fluorescence approaches for determining protein conformations, interactions and mechanisms at membranes. Traffic. 2005;6:1078–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakowicz J.R. Third Edition. Springer; New York: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catici D.A., Amos H.E., Pudney C.R. The red edge excitation shift phenomenon can be used to unmask protein structural ensembles: implications for NEMO-ubiquitin interactions. FEBS J. 2016;283:2272–2284. doi: 10.1111/febs.13724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiserova E., Kubala M. Mean fluorescence lifetime and its error. J. Lumin. 2012;132:2059–2064. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee S., Das A., Raghuraman H. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of a prokaryotic Mg2+ ion channel: implications for cost-effective purification of membrane proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 2019;161:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepard L.A., Heuck A.P., Tweten R.K. Identification of a membrane-spanning domain of the thiol-activated pore-forming toxin Clostridium perfringens perfringolysin O: an α-helical to β-sheet transition identified by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14563–14574. doi: 10.1021/bi981452f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S., Struve W.S. Time-resolved fluorescence of nitrobenzoxadiazole-aminohexanoic acid: effect of intermolecular hydrogen-bonding on non-radiative decay. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991;54:361–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fery-Forgues S., Fayet J.-P., Lopez A.J. Drastic changes in the fluorescence properties of NBD probes with the polarity of the medium: involvement of a TICT state? J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 1993;70:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chattopadhyay A., Mukherjee S., Raghuraman H. Reverse micellar organization and dynamics: a wavelength-selective fluorescence approach. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:13002–13009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghuraman H., Shrivastava S., Chattopadhyay A. Monitoring the looping up of acyl chain labeled NBD lipids in membranes as a function of membrane phase state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krepkiy D., Mihailescu M., Swartz K.J. Structure and hydration of membranes embedded with voltage-sensing domains. Nature. 2009;462:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature08542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukherjee S., Raghuraman H., Chattopadhyay A. Organization and dynamics of N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)-labeled lipids: a fluorescence approach. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2004;127:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raghuraman H., Chattopadhyay A. Orientation and dynamics of melittin in membranes of varying composition utilizing NBD fluorescence. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1271–1283. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crowley K.S., Reinhart G.D., Johnson A.E. The signal sequence moves through a ribosomal tunnel into a noncytoplasmic aqueous environment at the ER membrane early in translocation. Cell. 1993;73:1101–1115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90640-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghuraman H., Islam S.M., Perozo E. Dynamics transitions at the outer vestibule of the KcsA potassium channel during gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:1831–1836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314875111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turconi S., Bingham R.P., Pope A.J. Developments in fluorescence lifetime-based analysis for ultra-HTS. Drug Discov. Today. 2001;6:S27–S39. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berezin M.Y., Achilefu S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2641–2684. doi: 10.1021/cr900343z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho D., Lugo M.R., Merrill A.R. Harmonic analysis of the fluorescence response of bimane adducts of colicin E1 at helices 6, 7, and 10. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:5136–5148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipfert J., Columbus L., Doniach S. Size and shape of detergent micelles determined by small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:12427–12438. doi: 10.1021/jp073016l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klingler J., Vargas C., Keller S. Preparation of ready-to-use small unilamellar phospholipid vesicles by ultrasonication with a beaker resonator. Anal. Biochem. 2015;477:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin C.M., Li C.S., Tsao H.K. Size-dependent properties of small unilamellar vesicles formed by model lipids. Langmuir. 2012;28:689–700. doi: 10.1021/la203755v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Semenova N.P., Abarca-Heidemann K., Rothberg B.S. Bimane fluorescence scanning suggests secondary structure near the S3-S4 linker of BK channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10684–10693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kale J., Chi X., Andrews D. Examining the molecular mechanism of bcl-2 family proteins at membranes by fluorescence spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2014;544:1–23. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417158-9.00001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noskov S.Y., Roux B. Importance of hydration and dynamics on the selectivity of the KcsA and NaK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:135–143. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li T., Hassanali A.A., Singer S.J. Hydration dynamics and time scales of coupled water-protein fluctuations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3376–3382. doi: 10.1021/ja0685957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demchenko A.P. Site-selective red-edge effects. Methods Enzymol. 2008;450:59–78. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raghuraman H., Kelkar D.A., Chattopadhyay A. Novel insights into membrane protein structure and dynamics utilizing the wavelength-selective fluorescence approach. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. A. 2003;69:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raghuraman H., Kelkar D.A., Chattopadhyay A. Novel insights into protein structure and dynamics utilizing the red edge excitation shift approach. In: Geddes C.D., Lakowicz J.R., editors. Volume 2. Springer; 2005. pp. 199–214. (Reviews in Fluorescence). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chattopadhyay A., Haldar S. Dynamic insight into protein structure utilizing red edge excitation shift. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:12–19. doi: 10.1021/ar400006z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raghuraman H., Chattopadhyay A. Organization and dynamics of melittin in environments of graded hydration: a fluorescence approach. Langmuir. 2003;19:10332–10341. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rao M., Mayor S. Active organization of membrane constituents in living cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;29:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee A.G. Lipid-protein interactions in biological membranes: a structural perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1612:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hunte C. Specific protein-lipid interactions in membrane proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:938–942. doi: 10.1042/BST20050938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee A.G. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:62–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramu Y., Xu Y., Lu Z. Enzymatic activation of voltage-gated potassium channels. Nature. 2006;442:696–699. doi: 10.1038/nature04880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y., Ramu Y., Lu Z. Removal of phospho-head groups of membrane lipids immobilizes voltage sensors of K+ channels. Nature. 2008;451:826–829. doi: 10.1038/nature06618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang Q.X., Gonen T. The influence of lipids on voltage-gated ion channels. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012;22:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moraes I., Evans G., Stewart P.D. Membrane protein structure determination - the next generation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1838:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Encinar J.A., Molina M.L., González-Ros J.M. The influence of a membrane environment on the structure and stability of a prokaryotic potassium channel, KcsA. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5199–5204. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vamvouka M., Cieslak J., Gross A. The structure of the lipid-embedded potassium channel voltage sensor determined by double-electron-electron resonance spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2008;17:506–517. doi: 10.1110/ps.073310008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kofuku Y., Ueda T., Shimada I. Functional dynamics of deuterated β2 -adrenergic receptor in lipid bilayers revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:13376–13379. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge L., Villinger S., Zweckstetter M. Molecular plasticity of the human voltage-dependent anion channel embedded into a membrane. Structure. 2016;24:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frey L., Lakomek N.A., Bibow S. Micelles, bicelles, and nanodiscs: comparing the impact of membrane mimetics on membrane protein backbone dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:380–383. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gonzalez C., Rosenman E., Latorre R. Modulation of the Shaker K(+) channel gating kinetics by the S3-S4 linker. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000;115:193–208. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Priest M.F., Lacroix J.J., Bezanilla F. S3-S4 linker length modulates the relaxed state of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2312–2322. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swartz K.J. Tarantula toxins interacting with voltage sensors in potassium channels. Toxicon. 2007;49:213–230. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.White S.H., Wimley W.C. Peptides in lipid bilayers: structural and thermodynamic basis for partitioning and folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1994;4:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raghuraman H., Cordero-Morales J.F., Perozo E. Mechanism of Cd2+ coordination during slow inactivation in potassium channels. Structure. 2012;20:1332–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kratochvil H.T., Carr J.K., Zanni M.T. Instantaneous ion configurations in the K+ ion channel selectivity filter revealed by 2D IR spectroscopy. Science. 2016;353:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.