Abstract

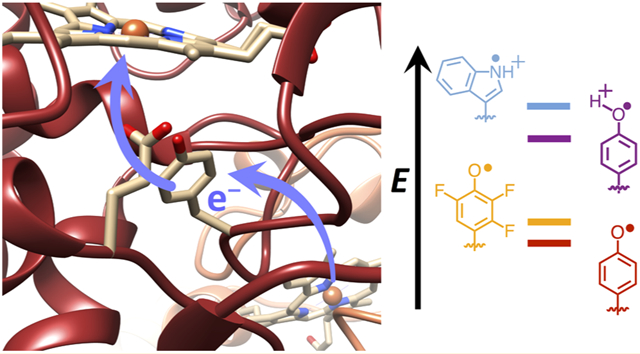

Transient tyrosine and tryptophan radicals play key roles in the electron transfer (ET) reactions of photosystem (PS) II, ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), photolyase, and many other proteins. However, Tyr and Trp are not functionally interchangeable, and the factors controlling their reactivity are often unclear. Cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) employs a Trp191•+ radical to oxidize reduced cytochrome c (Cc). Although a Tyr191 replacement also forms a stable radical, it does not support rapid ET from Cc. Here we probe the redox properties of CcP Y191 by non-natural amino acid substitution, altering the ET driving force and manipulating the protic environment of Y191. Higher potential fluorotyrosine residues increase ET rates marginally, but only addition of a hydrogen bond donor to Tyr191• (via Leu232His or Glu) substantially alters activity by increasing the ET rate by nearly 30-fold. ESR and ESEEM spectroscopies, crystallography, and pH-dependent ET kinetics provide strong evidence for hydrogen bond formation to Y191• by His232/Glu232. Rate measurements and rapid freeze quench ESR spectroscopy further reveal differences in radical propagation and Cc oxidation that support an increased Y191• formal potential of ~200 mV in the presence of E232. Hence, Y191 inactivity results from a potential drop owing to Y191•+ deprotonation. Incorporation of a well-positioned base to accept and donate back a hydrogen bond upshifts the Tyr• potential into a range where it can effectively oxidize Cc. These findings have implications for the YZ/YD radicals of PS II, hole-hopping in RNR and cryptochrome, and engineering proteins for long-range ET reactions.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tryptophan (Trp) and tyrosine (Tyr) radicals are increasingly recognized as essential features of enzymatic catalysis and protein function.1-7 Enzymes and light sensors such as photosystem II (PS II), ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), prostaglandin synthase, photolyases/cryptochromes, and BLUF proteins all involve Trp and Tyr radicals in long-range electron transfer (ET).8-14 Trp and Tyr residues have similar formal oxidation potentials (~−0.9 to −1.1 V at physiological pH15) that are in range of the reactive sites generated at oxometallocenters or photoexcited pigments in proteins. However, Trp and Tyr are not functionally interchangeable3,16,17 owing to the very different pKa values of their respective radicals. Hence, the protic environment has a large effect on their reactivity, and proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in its various forms3,7,18-21 can influence these reactions. Small-molecule experiments have demonstrated the impact of surrounding acids and bases on the PCET reactions of indole and phenol moieties.22-35 These studies, inspired by efforts to mimic the redox-active tyrosine residue (YZ) of PS II, highlight a range of mechanisms that are distinguished by single versus multisite PCET, electron-transfer driving force, solvent environment, the presence of hydrogen bond relays, and proximity of the proton donor and acceptor (reviewed by Pannwitz and Wenger36). Yet, a protein matrix provides a heterogeneous environment for Trp and Tyr redox chemistry, and it is unclear whether lessons learned from model studies, which are often carried out in nonaqueous solvents (with exception35), are fully applicable to these more complex systems. Moreover, most model systems are oxidative in nature and driven photochemically, whereas protein PCET can be both reductive and oxidative and initiated by a broad class of reactive ground- and excited-state species. To this end, engineered protein maquettes and peptide models have been employed to provide a more controlled protein environment for probing local effects on Trp and Tyr reactivity.37-41 In addition, studies of enzymes such as PS II, wherein the YZ radical couples photoexcitation to water splitting,42,43 and RNR, where incorporation of non-natural Tyr analogues have allowed for characterization of trapped radicals,44,45 underscore the capacity of local residues that provide hydrogen bonds or influence solvation to alter the reactivity of Trp and Tyr residues. In such protein systems, major questions center on understanding the specificity of which Tyr/Trp residues participate in ET reactions, how the protein matrix controls PCET by altering local formal potentials and pKa values, and, importantly, the role of conformational change and dynamics in modulating reactivity.3,46-48 All of these factors can combine to engender multistep or hole-hopping ET reactions capable of directing charge propagation over long distances and preventing nonproductive recombination.14

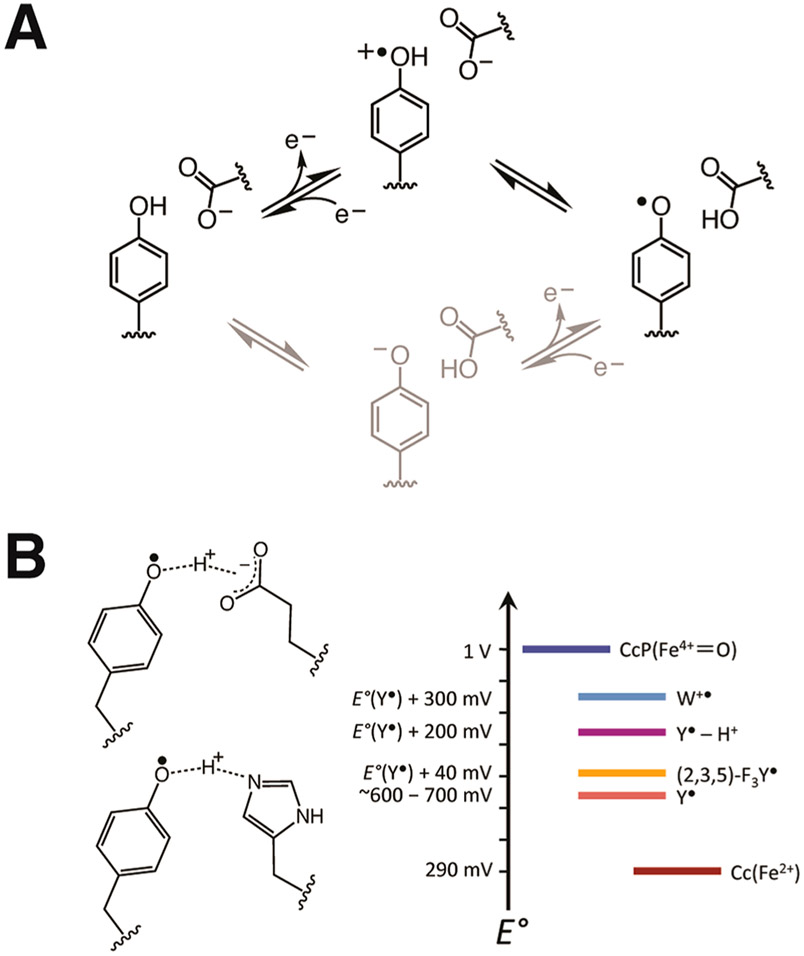

We have sought a tractable, yet relatively complex protein system to serve as a model for understanding multistep ET reactions that rely on Trp and Tyr. Cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) and cytochrome c (Cc) from yeast are a long-studied pair of redox partners that function to reduce peroxide to water through involvement of a Trp radical49-51 (Scheme 1). Peroxide reacts with the CcP heme to form a compound I (Cpd I) species that is then reduced sequentially by two molecules of Cc(Fe2+). Cpd I contains a Trp191 radical, which oxidizes the ferrous Cc heme (Cc(Fe2+)) some 20 Å away. Thus, to fully reduce peroxide, each Cpd I must react with two Cc molecules. The first reduction of Cpd I occurs with a second-order rate constant of 2 × 102 to 3 × 103 μM−1 s−1 depending on conditions, whereas the second reduction of Cpd II has a rate constant of 10 to 102 μM−1 s−1 from the same site.52,53 The second reduction is slower than the first owing to the equilibrium of step III in Scheme 1, which lies to the left.

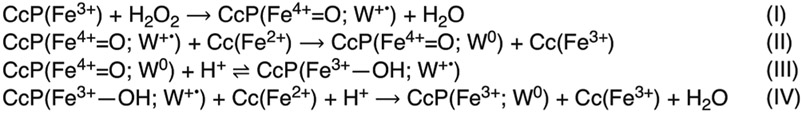

Scheme 1.

Reactions of WT CcP:Cca

aProtonation of the ferric hydroxide in step III may lag or precede reduction of W191•+ in step IV depending on conditions.

Extensive studies have revealed a complex dependence of the reaction on solution conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength, and temperature). Initial encounters of Cc with CcP are largely governed by electrostatics, and as a result, the reaction mechanism changes considerably as a function of ionic strength. Alternative docking configurations become operative at low ionic strengths (<100 mM), and Cc off-rates decrease substantially. Conformational gating coupled to dynamic docking of the CcP:Cc complex also modulates reactivity in a manner highly dependent on conditions.53-64

Importantly, substitution of Trp191 with Phe drops ET rates from Cc to CcP by many orders of magnitude.65-67 Surprisingly, when W191 is substituted by Tyr, a stable Cpd I species forms with a radical localized on Tyr191, but ET is slow and the system does not function.17 To investigate why Tyr191 would be inactive despite forming a stable radical, we have manipulated the redox and proton affinity of the Tyr site by introducing fluorotyrosine derivatives (FTyr) and hydrogen-bonding partners for the phenolic hydroxyl moiety. These experiments are carried out under conditions wherein protein exchange and reaction with peroxide are relatively rapid compared to ET from Cc to the CcP W191 variants. The FTyrs increase ET rates, but not as effectively as addition of a conjugate base that hydrogen bonds to Tyr. Through a series of spectroscopic, structural, and kinetic studies, we surmise that the neutral Tyr radical is too low in potential to rapidly oxidize Cc, but addition of a strong hydrogen bond to the Tyr radical upshifts its potential ~200 mV, which is sufficient to accelerate long-range ET from Cc(Fe2+). Although the active Tyr radical is not converted to a cation, which has only been observed for Tyr on very fast time scales in biological systems,68 the effect of a suitably positioned conjugate base on reactivity is quite dramatic. The CcP:Cc Tyr radical is analogous to the YZ radical of PS II, which requires interaction with a conserved His residue to transit electrons between the P680 special chlorophyll dimers and the Mn cluster of the oxygen-evolving complex.69-71 Unlike PS II, the CcP:Cc system is readily studied by crystallography and amenable to incorporation of non-natural residues, and unlike RNR, in CcP:Cc, the intermediate Tyr radical is stable and does not require modification to be studied. Thus, CcP:Cc provides an excellent model for understanding how energy-transducing proteins control long-range ET reactions through redox-active residues.

RESULTS

Electron Transfer Rates of Y191 Variants.

Given that the structure CcP W191Y is nearly identical to the wild-type, WT,17 the inactivity of Cpd I most likely derives from changes in the formal potential and/or proton affinity of the radical. To alter these properties of Y191, we incorporated non-natural fluorotyrosine residues in place of Y191, modified its protic environment by engineering basic, hydrogen-bonding residues proximal to the phenoxyl moiety, and shifted the formal potential of the Cc(Fe2+) donor through residue substitutions of known effect.72 The 2,3,5-trifluorotyrosine and 3,5-difluorotyrosine amino acids were synthesized by tyrosine phenol lyase, purified, and incorporated into CcP using an E3 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA amber suppression system.73,74 The use of fluorotyrosine residues to manipulate E∘′ and pKa has been well established by previous studies of PCET mechanisms and pathways in PS II, RNR, and BLUF domains.44,75-78 The particular analogues that were selected provide relatively small formal potential and pKa perturbations at the 191 site (approximately ±50 mV and −~3.5 pKa units).75 Also, under the pH 6 conditions of the experiments, these residues (pKa = 6.4 for 2,3,5-F3Y and 7.2 for 3,5-F2Y) remain primarily protonated prior to peroxide reaction. Yet, tyrosyl radicals greatly favor the neutral deprotonated form owing to a low intrinsic pKa of −2,15,39 although a protein matrix can alter this value.79,80 Notably, the WT W191•+ radical maintains a cationic state in Cpd I, owing in part to interaction with Asp235.81-83 Hence, coordination of tyrosyl radicals to a nearby proton acceptor, such as His, Asp, or Glu, could potentially stabilize the cationic form or facilitate proton transfer events coupled to ET.39,84 To manipulate the protic environment of Y191, neighboring Leu232 was replaced with either His or Glu (W191Y:L232H and W191Y:L232E, respectively). Correspondingly, we also altered the formal potential of the Cc(Fe2+) donor by replacing Tyr48 with Lys to upshift the potential 120 mV.72

Cc(Fe2+) Oxidation Rates in Single and Multiple Turnover Conditions Depend on Driving Force and a Conjugate Base.

ET rates from Cc(Fe2+) to the Cpd I-like species of the CcP variants were measured in single turnover (1 μM CcP, 2 μM H2O2, 2 μM Cc(Fe2+)) and multiple turnover formats (1 μM CcP, 10 μM H2O2, 30 μM Cc(Fe2+)) (Figure 1). Ionic strength conditions and pH were chosen to minimize any second-site binding of Cc to CcP. Protein concentrations were as high as practical to provide good spectral properties. Under the 100 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer conditions (ionic strength ~110 mM at pH 6), Cc off-rates are >2000 s−152,53 and peroxide reacts with CcP to produce Cpd I with a second-order rate constant of ~4 × 107 M−1 s−1 (or a pseudo-first-order rate constant of 400 s−1 at 10 μM H2O285). The dissociation constant (KD) of Cc for CcP under these conditions is ~8 μM,86 which implies that >80% of CcP:Cc complex is associated in the multiple turnover case, but little complex is associated in the single turnover case. A second-order rate constant derived from steady-state analysis (kcat/KM ≈ 200 μM−1 s−186) matches well with the second-order rate constant for the slower second reduction of Cpd II by Cc52 (step IV in Scheme 1), which places an upper bound below which ET to the modified 191 site will be rate-limiting.

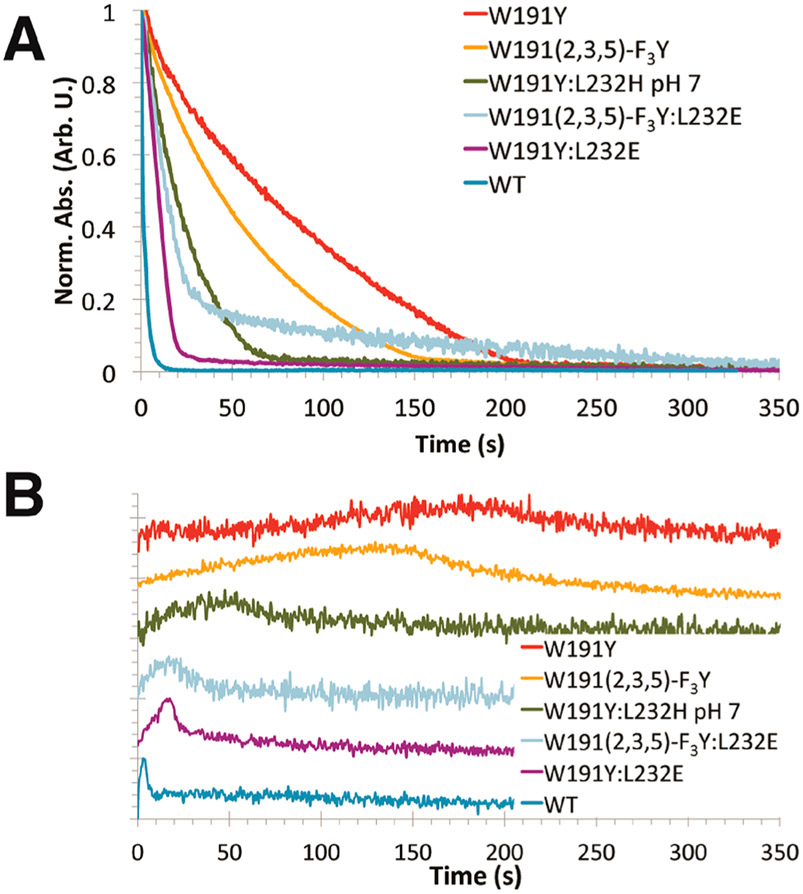

Figure 1.

Cc oxidation reactions under multiple turnover conditions. (A) Oxidation of Cc(Fe2+) by CcP variants was measured at Abs550 nm–Abs540 nm, with values normalized from 0 to 1 (100 mM potassium phosphate (KPi), pH 6 for all variants except for W191Y:L232H, which was at pH 7). (B) Progress curves at Abs434 nm reflect formation and decay of the ferryl (Fe4+═O) species. (Curves were normalized and shifted vertically.)

Our rate measurements rely on monitoring the loss of Cc(Fe2+) and formation/decay of the ferryl (Fe4+═O) CcP upon peroxide addition. Notably, ET between Cc(Fe2+) and the 191 radical (Scheme 1) is expected to be slow compared to oxidation of the 191 residue by Fe4+═O CcP.17 In the multiple turnover scenario, ET from Cc(Fe2+) and regeneration of Cpd I with peroxide produces a low level of the ferryl species that increases as the concentration of Cc(Fe2+) drops, only to then subside when peroxide is expended (Figure 1B). Correlation of the rate constants from the single turnover and multiple turnover regimes indicates that under these conditions protein exchange kinetics do not dominate the rates of Cc oxidation (Figure 2). Nonetheless, for variants of low reactivity, the multiple turnover rates lag compared to those of the single turnover rates, thereby indicating that at slow rates of ET protein exchange does compete to some extent, probably owing to the increasing concentration of interfering Cc(Fe3+) as peroxide reduction proceeds. Given the kinetic parameters described above, this phenomenon combined with mixing limitations likely reduces the observed WT rate constant in this format.

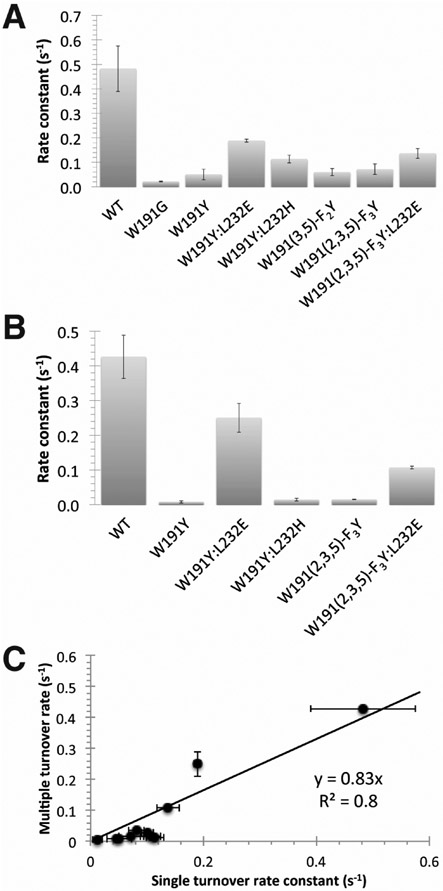

Figure 2.

Correlation between single and multiple turnover rate constants for Cc oxidation. (A) Single turnover rate constants obtained in 100 mM KPi buffer, pH 6 (Supplemental Table 1). (B) Multiple turnover rate constants in 100 mM KPi buffer, pH 6 (Supplemental Table 1). (C) Correlation between single and multiple turnover rate constants indicates that Cc oxidation is not dominated by protein exchange kinetics in the multiple turnover format.

WT CcP rapidly oxidizes Cc(Fe2+), and a transient ferryl signal (Abs434 nm) develops that then dissipates over the course of the pseudo-first-order decay as the pool of Cc(Fe2+) depletes (Figure 1B). In contrast, W191Y CcP reacts slowly with Cc(Fe2+) and has similar inactivity to W191G (Figure 2), in which a solvent-filled cavity replaces the radical site.17 As a result, the CcP ferryl persists for minutes (Figure 1B) and only completely reduces to the ferric state during the slow phase of recovery.65 Replacement of Tyr191 with a stronger oxidant (2,3,5-trifluorotyrosine) marginally increases the ET rate by half relative to W191Y, consistent with the predicted formal potential increase of the FTyr• (E′∘ ≅ +40 mV relative to Tyr•).44,75 Comparably, replacement of residue 191 with a lower formal potential 3,5-difluorotyrosine moiety (E′∘ ≅ −25 to −50 mV relative to Tyr•)44,75 results in a similar Cc oxidation rate to that of Tyr191 (Figure 2A). These results indicate that the CcP:Cc ET rates are sensitive to the Tyr191 potential, but a modest upshift in potential of the Y191 site does not rescue activity to an appreciable extent.

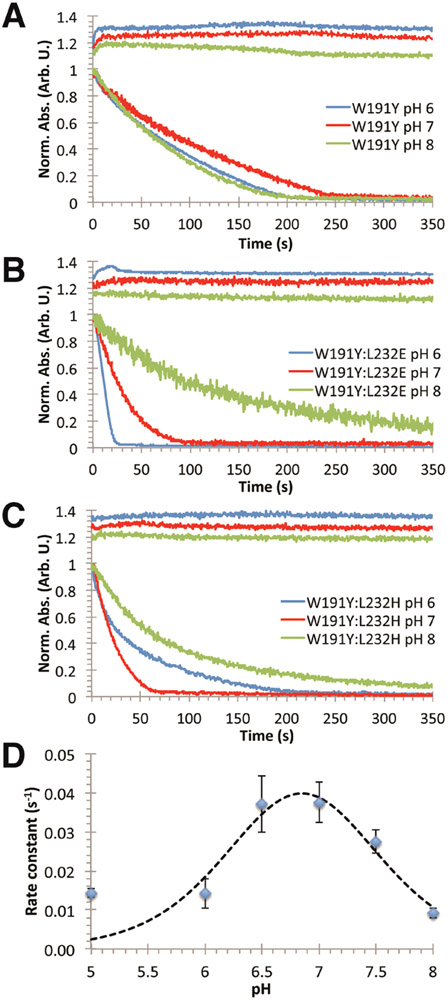

Examination of the CcP W191Y crystal structure suggested that substitutions of Leu232 by His and Glu would affect the protic environment near the Y191 hydroxyl group. Incorporation of L232H into the W191Y variant causes little change to ET rate constants at pH 6, but produces a nearly 3-fold increase in activity at pH 7 under multiple turnover conditions (Figure 3; Supplemental Table 1). This rate increase then diminishes at higher pH. At optimum pH, the Cc oxidation curve changes from biexponential to a WT-like, monoexponential decay, indicating that the biexponential characteristics are likely due to a mixed population of slowly exchanging conformational or protonation states (Figure 3C). Curve fitting of the data to a two-proton ionization model (eq 1) indicates two pKa values (6.46 and 7.24): one for His232 deprotonation and another we presume to be the hydrogen-bonded proton to Y191• (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Conjugate base next to Tyr191 in CcP alters the pH dependence of Cc oxidation. Kinetic traces of Cc oxidation (lower curves) and CcP ferryl formation/decay (upper curves) were obtained with either (A) W191Y CcP, (B) W191Y:L232E CcP, or (C) W191Y:L232H CcP. W191Y shows little variation with pH, whereas oxidation rates with either the Glu232 or His232 variant gives strong pH dependencies indicative of a hydrogen bond to Tyr191. (D) Dependence of Cc(Fe2+) oxidation rates on pH for CcP W191Y:L232H in 100 mM KPi buffers. Fit to a two-proton ionization model (eq 1) gives two pKa values of 6.46 and 7.24, which likely coincide with the pKa of His and the hydrogen-bonded complex, respectively.

| (1) |

Additional evidence for rate acceleration from the introduction of a hydrogen-bonded proton to Y191• was attained by lowering the pKa of the coordinating base by substitution of residue 232 with Glu. Remarkably, W191Y:L232E yields similar apparent Cc oxidation behavior as WT CcP with an ~30 × acceleration in Cc(Fe2+) oxidation rate compared to the W191Y parent (Figures 1,2; Supplemental Table 1). In W191Y:L232E, ferryl buildup and decay kinetics approach those observed for WT CcP (Figure 1B). The residue 232 substitutions do not impact Cpd I formation, as assessed by reacting CcP alone with peroxide (Supplemental Figure 1). The Glu variant also exhibits a pH dependency unseen in W191Y (Figure 3A,B). At higher pHs, the Cc oxidation rate slows to that of W191Y, again suggesting that deprotonation of a hydrogen-bonded complex composed of Y191 and the conjugate base reduces reduction rates (Supplemental Table 1). The fact that Glu232 has a larger affect on rate than His, despite having the lower pKa, suggests that the conjugate base does not function to increase the rate of proton transfer from Y191.

Somewhat surprisingly, the effects of FTyr substitution and conjugate base addition were not synergistic. The L232E substitution in concert with the FTyr variant W191-F3Y produces a fast phase of Cc(Fe2+) oxidation that is intermediate in rate to W191Y:L232E and W191-F3Y, but also exhibits a much slower secondary phase. Although the origin of the slow phase is unclear, it may owe to oxidative modification of the variant protein. Regarding the fast phase, the lower pKa of the FTyr73 in conjunction with its elevated formal potential may contribute to a radical less readily reduced than in W191Y:L232E, but more so than in W191-F3Y alone (Scheme 1).

Proton-coupled ET reactions often produce substantial deuterium kinetic isotope effects if the proton and electron transfers are synchronous. Overnight incubation of W191Y CcP:Cc in a D2O-based phosphate buffer causes only minor changes to the Cc(Fe2+) oxidation rate (kH/kD ≅1.2–1.4), but differences are not statistically significant (p = 0.80, N = 4). In contrast, W191Y:L232E CcP:Cc shows a slightly larger solvent isotope effect that is statistically significant under single turnover conditions (kH/kD ≅ 1.7; kobs, D2O = 0.09 ± 0.04 s−1 versus kobs, H2O = 0.166 ± 0.007 s−1; p = 4.6 × 10−7, N = 12).

To explore the effects of altering the potential of the donor, we produced a Cc Y48K variant, which is known to upshift the Cc(Fe2+) potential from 290 mV to 407 mV.72 As expected, ET rates to W191Y:L232E are decreased with Cc Y48IK (from kobs = 0.189 ± 0.006 to 0.156 ± 0.005 s−1 p = 4.44 × 10−5; N = 4 and 5, respectively; Supplemental Table 1), again showing that the ET rate between Y191• and Cc(Fe2+) is sensitive to driving force. A crystal structure of the CcP(W191Y):Cc(Y48IK) complex (PDB 6P43) confirms that the substitutions cause no significant structural changes to either protein or to their association mode (Supplemental Figure 2).

Crystal Structures of W191Y Variants Reveal Hydrogen Bonds to Y191.

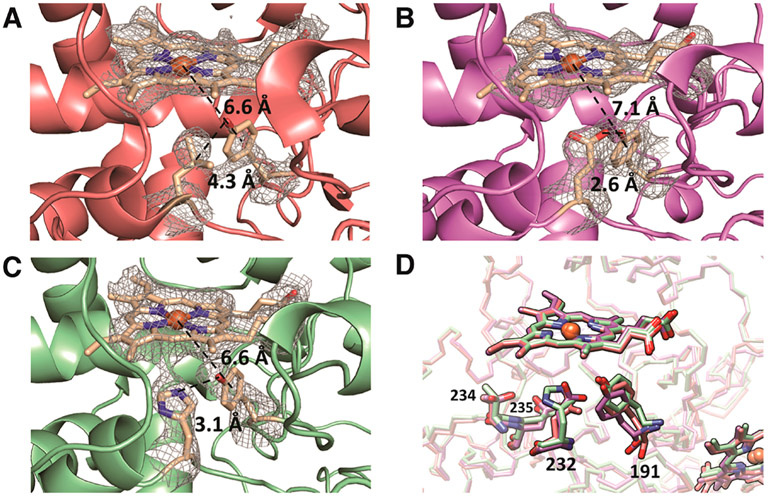

Crystal structures of W191Y (PDB 5CIH; Figure 4A), W191Y:L232E (PDB 6P41; Figure 4B), and W191Y:L232H (PDB 6P42; Figure 4C) all in complex with Cc (Supplemental Table 2) reveal an identical interface between CcP and Cc, along with positions of the 232 side chains that indicate hydrogen bonds to Y191 (Figure 4D). The active sites of the heme centers, including catalytically essential residues Arg48, Trp51, and His52, are not affected by the substitutions.81,87-90

Figure 4.

Hydrogen bond environments surrounding residue 191 in crystal structures of CcP:Cc complexes. Fo – Fc difference maps of (A) W191Y CcP, (B) W191Y:L232E CcP, and (C) W191Y:L232H with the heme and residues 191 and 232 omitted from the phase calculations. Maps are displayed at a contour level of 2 σ. Distances are measured from the heme iron to the center of the phenol ring and between the Tyr191 hydroxyl and the residue 232 side chain atom of closest approach. Distances are average measurements from the two complexes contained in the ASU. (D) Superposition of CcP Y191 variants: W191Y (red), W191Y:L232E (purple), W191Y:L232H (green), all in complex with Cc. Substitution of Leu232 with Glu results in a 1.04 Å displacement of Tyr191. Replacement with His232 does not significantly shift the position of Tyr191; however, under these crystallization conditions, His232 is angled away from Tyr191, which is likely a result of hydrogen bonding to Thr234 or an electrostatic interaction with Asp235.

In W191Y:L232E, the phenol ring of Tyr191 shifts closer to the 232 residue by an RMSD of 0.7 Å compared to W191Y. The carboxyl moiety of Glu232 and the phenol of Tyr191 are well-defined at the 1 σ level in the 2.9 Å resolution 2Fo–Fc electron density map. A short 2.6 Å distance of separation between the Tyr191 hydroxyl group and Glu232 carboxyl oxygen implies a strong hydrogen bond between the side chains. Difference electron density bridges the two side chains in both of the CcP:Cc complexes in the asymmetric unit (Figure 4B). In W191Y:L232E, compared to W191Y, the CcP heme to Tyr191 phenyl ring distance increases by 0.5 Å (~7.1 Å in W191Y:L232E versus ~6.6 Å in W191Y), and the distance between the Cc heme iron atom in Cc and Tyr191 also slightly increases by 0.5 Å (~21.6 Å in W191Y:L232E versus ~21.0 Å in W191Y). Thus, the Y191 and E232 substitutions do not substantially alter the protein complex, but the structures do support a hydrogen bond between these two residues prior to reaction.

Replacement of Leu232 with His also results in a structure very similar to that of the W191Y parent. However, in this structure (crystallized at pH 6 where ET rates do not increase with the His232 addition) His232 angles away from Y191 and shares no bridging electron density with the phenolic oxygen. Instead, difference density between Tyr191 and His175 suggests a competition between His175 and His232 for the phenolic oxygen of Tyr191; both nitrogen atoms are within hydrogen-bonding distance of the Tyr191-OH (His175 N-δ ≈ 3.9 Å and His232 N-ε ≈ 3.1 Å). Furthermore, the His232-protonated Nδ nitrogen is in range to interact with Thr234 or Asp235 (Figure 4D). Thus, in the imidazolium form, His232 cannot accept a proton from Y191 and may not be suitably positioned to hydrogen bond back to the Tyr radical, consistent with an ET rate similar to that of the parent at low pH. However, His232 is positioned appropriately for the neutral imidazole moiety to interact productively with Tyr191 at higher pH and thereby enhance reactivity.

The resolution of the structures is not sufficient to define any clearly ordered water molecules in the proximal heme pocket. However, water molecules are well resolved in structures of the WT CcP:Cc complex (1U74) and W191F CcP:Cc (5CIF), a structural analogue to W191Y CcP:Cc. Superpositions of these structures predict no ordered water molecules near the ionizable moieties of the 191 and 232 residues, although the introduction of polar groups at these positions could alter solvation.

Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy of Tyr191 Radicals Indicates Changes in Hydrogen Bond Environment.

cw-ESR: X-band continuous wave electron spin resonance (cw-ESR) was used to further probe the electronic and protonation properties of the W191Y• variants. As previously reported,17 the cw-ESR spectrum of W191Y Cpd I indicates formation of Tyr• at site 191; W191G produces a negligible signal at g = 2.0. Incorporation of 2,3,5-FTyr exhibits a signal reminiscent of the parent (orange, Figure 5A). This is in contrast to the line broadening observed for the photogenerated 2,3,5-FTyr radical in aqueous solution,73,91 which likely derives from an increase in anisotropy and hyperfine interactions from the fluorine moieties in a fully solvated aqueous environment. The fluoro groups are known to moderately reduce spin population at the oxygen but overall do not cause major redistribution of the spin density, which remains symmetric about the C2 rotational axis.45 Substantial hole migration from FTyr191 to an adjacent tyrosine in CcP is unlikely, as radical migration away from the 191 site would reduce, not increase, the Cc oxidation rates.

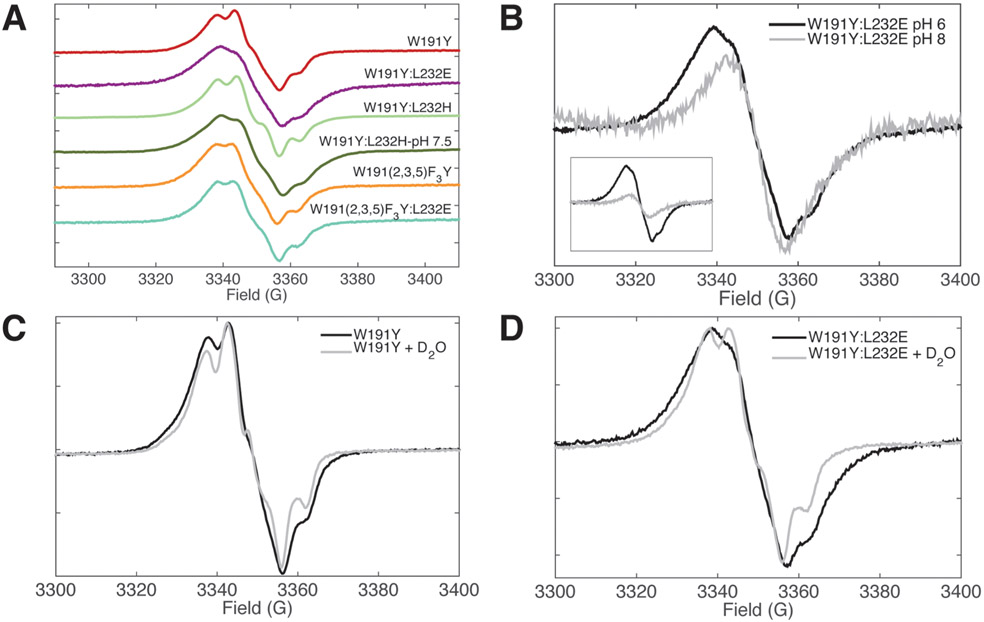

Figure 5.

cw-ESR of Cpd I provides evidence for hydrogen bond formation in L232E,H CcP. (A) X-band cw-ESR spectra of Cpd I acquired at 12 K for CcP variants. Samples contained 100 mM KPi, pH 6 buffer, except for where indicated. W191Y:L232H at pH 7.5 was acquired with 4 G modulation, and all others were collected with 1.5–2 G modulation. Spectra were base-lined, normalized, and shifted vertically. (B) In the X-band cw-ESR spectra of W191Y:L232E, high pH buffer results in a narrowing and decrease of signal intensity (inset), indicating loss of the phenolic oxygen hydrogen bond. (C, D) X-band cw-ESR of H2O- and D2O-exchanged Cpd I. W191Y Cpd I shows only modest changes after buffer exchange, whereas W191Y:L232E Cpd I exhibits a narrowed line shape in D2O that resembles that of W191Y Cpd I.

Cpd I of W191Y:L232H at pH 6 shows only minor differences in hyperfine coupling compared to the parent W191Y; however, raising the pH to 7.5 results in dramatic line broadening of the singlet feature relative to W191Y (dark green, Figure 5A). W191Y:L232E at pH 6 shows even more pronounced line broadening than L232H at pH 7.5. When the pH is raised to 8, spectra for W191Y:L232E narrow to a width similar to that of W191Y, although signal intensity also lessens (Figure 5B). The change in ESR line shape in pH conditions that also enhance ET rates signifies an altered microenvironment of the Tyr• in the presence of these coordinating bases.

For His232, line broadening requires deprotonation of the imidazolium above pH 6.0, consistent with the low pH crystal structure. A similar broadening of the Y191:E232 spectra at pH below 8 likely derives from the hydrogen bond between E232 and Y191 inferred from the crystal structure. In addition to hyperfine interactions from hydrogen-bonded protons, the rotational angle of the phenol ring can influence Tyr• line shapes. The degree of hyperconjugation of a Cβ–H σ bond into the phenol π system alters relative contributions of a narrow singlet and a wide triplet signal.92,93 However, the crystal structures of W191Y and W191Y:L232E do not differ in the Tyr191 rotamer state, and thus, changes in hyperfine coupling likely result from hydrogen bond formation with the conjugate base. Indeed, electronic structure calculations suggest that the spin distribution of tyrosyl radicals, as reflected in the g values and line shapes of ESR spectra, are highly sensitive to protonation and hydrogen bonding.94-98

Somewhat surprisingly, but consistent with the reactivity data, addition of a coordinating side chain to the 2,3,5-FTyr variant W191F3Y:L232E does not broaden the radical spectrum (Figure 5A). Owing to the higher acidity of FTyr compared to Tyr,73 either a proton is lost from the system (which is less probable in a pH 6 buffer; pKa(FTyr) = 6.473) or the hydrogen bond shared with Glu232 is weaker than in W191Y:L232E. In the latter case, a longer FTyr•…H distance may reduce the influence on the coupling parameters of the radical3 the rate of ET.

X-band cw-ESR measurements of D2O-treated Y191• show sharpened hyperfine features and narrowing of line shapes as expected (Figure 5C,D). However, D2O substitution for W191Y:L232E gives much more prominent effects than W191Y alone, clearly demonstrating the dependency of line broadening on hyperfine coupling from exchangeable protons in the presence of E232.

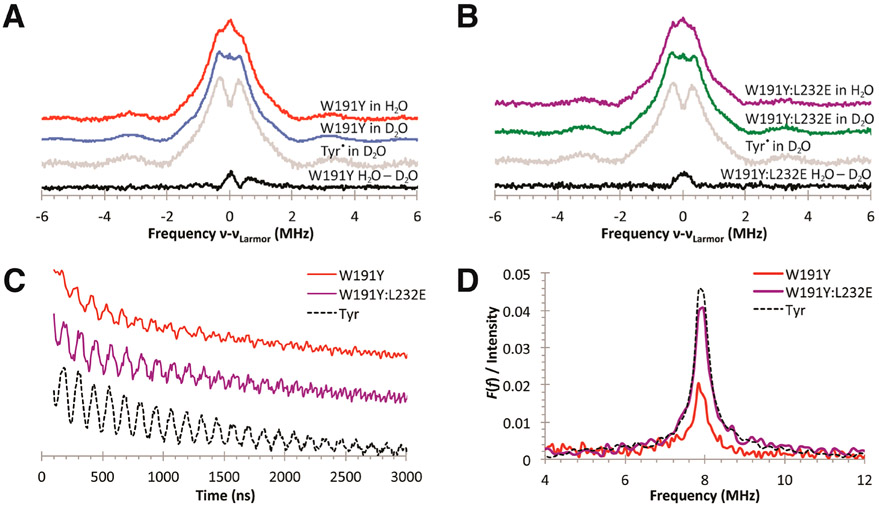

Electron Spin Echo–Electron Nuclear Double Resonance (ESE-ENDOR) Spectroscopy.

Q-Band ESE-ENDOR data on protonated and deuterated W191Y (Figure 6A) and W191Y:L232E (Figure 6B) Cpd I samples support interactions between the Tyr• radical and exchangeable protons. The species in 1H buffer have similar proton ESE-ENDOR spectra and weak hyperfine coupling features centered at the Larmor frequency (~51 MHz) that likely originate from exchangeable protons (red and purple spectra; Figure 6A,B). After incubation in deuterated buffer, both species (blue and green spectra; Figure 6A,B) exhibit similar 1H-hyperfine coupling constants to those of photogenerated tyrosyl standards in deuterated solution (gray spectrum; Figure 6A,B). These nonexchangeable features likely result from a combination of hyperfine coupling interactions between the unpaired radical and β-methylene or ring protons and have been assigned using ESE-ENDOR and 2H-labeling in other Tyr• systems, such as YD and YZ in PS II and Tyr single crystals.99-103 Subtraction of the 1H ESE-ENDOR of the protonated and corresponding deuterium-exchanged samples (black spectra; Figure 6A,B), scaled by the unchanging shoulder features at ν = ±0.3 MHz, reveals contributions from exchangeable protons coupled to Tyr191•. The difference spectra indicate that both the Y191• and Y191•:E232 radicals have some degree of H-bonding, yet owing to the spectral noise in the spectra, broadening effects are not well determined. Typically, broadened 1H2O–2H2O signals have been attributed to H-bonding, as observed between PS II YZ and YD (both H-bonded) and E. coli RNR Y122 (not H-bonded) tyrosyl signals.104 The Y191:E232 difference spectrum does appear broader than Y191 alone, but such signals are difficult to resolve and would likely benefit from higher-field spectroscopy. To improve upon interpretations from nonideal 1H ENDOR spectral subtractions, we also attempted to obtain deuterium ESE-ENDOR spectra. High-resolution 2H-ESE-ENDOR spectra of H-bonded Tyr• radicals often produce sharp peaks or “wings” less than 0.6 MHz from νLarmor.104-108 Both Y191 and Y191:E232 CcP Cpd I reveal the presence of exchangeable 2H, but unfortunately, poor S/N ratios prevent quantification and limit analysis.

Figure 6.

ENDOR and three-pulse ESEEM spectra collected at 33.8 GHz on samples of W191Y Cpd I, W191Y:L232E Cpd I, and photogenerated tyrosyl solution. (A, B) Normalized 1H-ESE-ENDOR spectra of W191Y and W191Y:L232E Cpd I species and photogenerated tyrosyl in H2O and D2O 100 mM KPi buffer, pH 6; νLarmor ≈ 51 mHz. Subtracted spectra of Cpd I species (in dark and light gray) in protonated and deuterated environments reveal H-bonding interactions. Spectral interference with other weakly bound protons, however, makes quantification difficult. The asymmetric shoulder feature in the W191Y Cpd I difference spectrum is likely not significant. (C) Time domain spectra (vertically stacked and amplitudes normalized from 0 to 1 between 0 and 3000 ns) exhibit weaker stimulated-echo amplitude for W191Y Cpd I compared to similarly prepared samples of W191Y:L232E Cpd I and photogenerated Tyr. (D) Fourier-transformed signals show hyperfine couplings near that of the 2H Zeeman frequency. Signals normalized to the echo amplitudes at 0 ns demonstrate the lower levels of hydrogen bonding in W191Y Cpd I compared to W191Y:L232E.

Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) Spectroscopy.

2H-ESEEM spectroscopy allows for the quantification of dipolar contributions between 2H and Tyr• using hyperfine interactions from the observation of the stimulated echo and provides an important complement to the ESE-ENDOR results. Furthermore, 2H-ESEEM has high sensitivity toward weak, anisotropic couplings, and the echo intensities are influenced by the distance between electron and 2H spins, providing the added advantage of spatial selectivity for coupled nuclei within 1 nm of the radical.109-114 Notable differences are found in the 2H-ESEEM spectra between the W191Y:L232E variant and the W191Y parent after exchange into D2O (Figure 6C,D). Indeed, both Y191 and Y191:E232 give modulation frequencies of ~7.8 MHz at a microwave frequency of 33.8 GHz. Such modulations are typical for hyperfine interactions resulting from hydrogen bonding between the YO• radical and an exchangeable proton/deuteron, as observed for a photogenerated YO• radical in D2O solution (Figure 6C) and for the hydrogen-bonded YZ• and YD• radicals of PS II.104,115-118 However, a substantially reduced modulation depth in the Y191 parent indicates significantly less hydrogen bonding to the phenoxyl moiety than in either Y191:E232 or the photogenerated Tyr standard (Figure 6C,D) because the amplitude depends on the interaction strength and number of coupled deuterons. Moreover, the very similar modulation depths of Y191•:E232 and the solvated Tyr• standard suggest that most of the Tyr191 radicals in Y191:E232 are hydrogen-bonded.

Hydrogen bonds to the phenoxyl oxygen are expected to produce modulations near that of the 2H Zeeman frequency, regardless of the donor source. In regards to the solvated Tyr• standard, D2O molecules must be the H-bond donor; for the parent W191Y, crystallographic data suggest that the site is weakly accessible to water, and no side chains or conserved water molecules are involved in H-bonding; in the case of W191Y:L232E, the crystal structure indicates that the donor is E232. Hence, ESEEM spectroscopy provides additional evidence for the presence of an ordered hydrogen bond in W191Y:L232E, and with all else being similar between the two CcP variants, the added hydrogen bond to the Tyr191• radical in W191Y:L232E very likely correlates to the observed reactivity differences in the turnover assays.

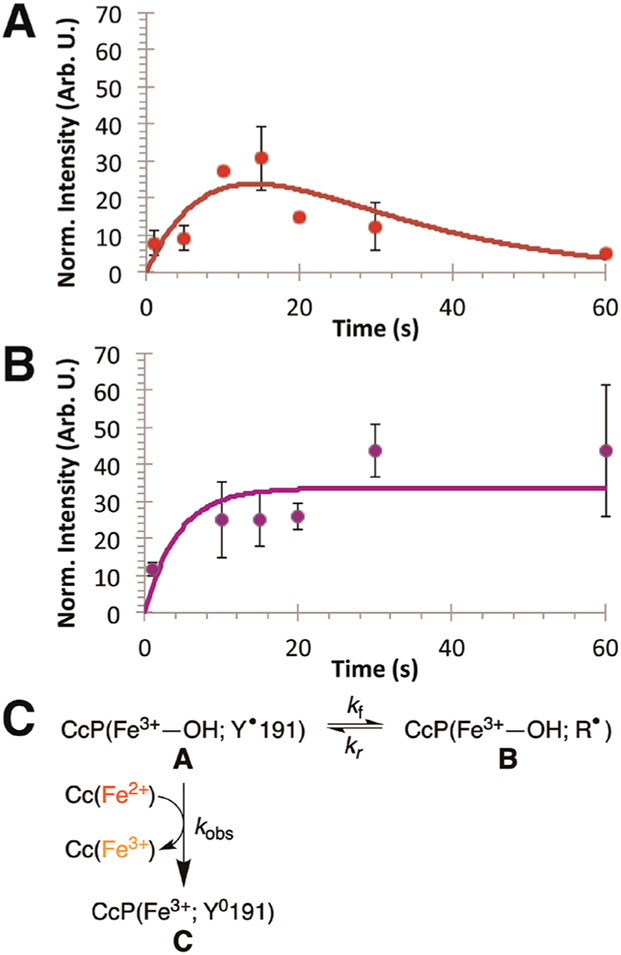

Rapid Freeze Quench cw-ESR Kinetics Support ET Rate Enhancement by E232.

The dynamics of the Tyr• radical within W191Y and W191Y:L232E CcP in complex with Cc provide another means to evaluate how the conjugate base affects Tyr• reactivity. Under single turnover conditions with stoichiometric Cc, Tyr• formation and decay in CcP:Cc (W191Y and W191Y:L232E) were monitored by rapid freeze quench (RFQ) ESR spectroscopy experiments. Samples were flash-frozen at successive time points during a single turnover reaction. All X-band cw-ESR absorption signals were numerically integrated and normalized to those of an internal standard—Er3+ chelated by diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)—to compensate for variations in sample preparation and packing within ESR tubes. This unreactive lanthanide species has a well-resolved, sharp ESR signal at g = 11.8 and few features elsewhere. Radical signals were quantified and progression curves fitted by kinetic modeling of competitive reactions (eq 6; Table 1).119,120 In the absence of Cc, W191Y CcP Cpd I formation is complete by the initial time point and invariant over the first 30 s, with an average integrated absorption signal of 240 ± 110. Loss of radical signal when Cc is present corresponds to reduction by Cc(Fe2+). The radical kinetics observed by RFQ are much slower than the initial reduction of CcP by Cc(Fe2+), and importantly the amplitude of the radical signal that develops and decays is <10% of that of the Cpd I in the absence of Cc (Figure 7). Thus, Tyr191• of Cpd I is initially reduced by prebound Cc(Fe2+) at rates too fast to be well resolved. The radical signal over the first five seconds is likely the tail end of this initial Tyr• reduction, which appears concomitantly with the early phase of Cc oxidation. However, after initial reduction of the radical in the prebound complex, Tyr191• will re-form due to oxidation by the ferryl species of Cpd II (Scheme 1). A second equivalent of Cc(Fe2+) is required to exchange with the spent Cc(Fe3+) to reduce the Tyr191• radical. However, if exchange is slow, a consequence of having a minority concentration of Cc(Fe2+) remaining in the sample, the radical may migrate within CcP before reduction by rebound Cc(Fe2+); that is, Tyr191• will be reduced by another nearby redox-active residue within the protein (Figure 7C). Return of the radical to the 191 site eventually leads to reduction by exchanged Cc(Fe2+). As the potential of the Y191• radical increases, the likelihood that the radical will migrate within CcP before Cc(Fe2+) exchange may also increase.

Table 1.

Parameters for Fits to Progress Curves of Tyr• As Measured by Rapid Freeze Quench cw-ESR Spectroscopy a

| variant | A0 | kf [s−1] | kr [s−1] | kobs [s−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W191Y | 240 ± 110 | 0.019 | 0.061 | 0.061 |

| W191Y:L232E | 240 ± 110 | 0.025 | 0 | 0.15 |

R2 ≅ 0.4–0.5.

Figure 7.

RFQ X-band ESR spectroscopy of Tyr• radicals in CcP. X-band ESR tyrosyl radical signals were integrated and normalized to an Er3+ internal standard signal. Y191• was generated under single turnover conditions by reacting 0.15 mM CcP with 0.3 mM H2O2 and quenched by 0.3 mM Cc(Fe2+). Integrated, averaged, and normalized signals were fit by biexponential curves following a “competitive reaction” model (red and purple lines; eq 6). Comparison between (A) W191Y and (B) W191Y:L232E demonstrates differences in radical progression, which are reflected in the development of the ferryl species by UV–vis kinetics. (C) Scheme for radical migration. The first equivalent of bound Cc(Fe2+) quickly oxidizes and quenches Tyr191•, generating the ferryl species (CcP(Fe4+)) that is in equilibrium with state A, CcP(Fe3+–OH; Y•). Exchange with the remaining equivalent of Cc(Fe2+) will compete with Tyr191• oxidation of adjacent redox-active side chains, causing a migration of the electron hole from position 191 to a remote (R) site (state B.) In W191Y CcP, ΔGex′ ≅ 0 and the radical reversibly returns to the 191 site, where it eventually quenches upon reaction with Cc(Fe2+) (state C). However, in the case of W191Y:L232E, the migrated radical does not return to 191 to be quenched by Cc(Fe2+), and instead the radical signal plateaus at long times.

For W191Y, after the first equivalent of Cc(Fe2+) is oxidized, a residual Tyr• signal rises gradually to a maximum value after approximately 15 s, followed by a slow decay over the period of ~45 s. In contrast, the W191Y:L232E residual radical signal rises within the first 10 s and remains relatively stable for the duration of the observation time. These Tyr• signals fit well to biexponential equations describing competitive reactions whereby Tyr191• is reduced either by Cc(Fe2+) (kobs) or by an adjacent side chain (kf) that may in turn reoxidize Tyr191 back to a radical (kr; Table 1). The resultant kobs values agree with those for the single turnover reactions. Fitted kf values are quite similar for W191Y and W191Y:L232E CcP owing to the sparseness of early time points in the Y191:E232 data set. For W191Y CcP, kf ≅ kr, which indicates that the formal potentials of Tyr191• and the remote site radicals are similar (i.e., ΔGex′ ≅ 0), and so, Y191• exchanges with the remote site until it is quenched by exchanged Cc(Fe2+). However, reoxidation of Tyr191 by the remote radical does not occur in Y191:E232 (kr = 0); the signal does not decrease over the time course (Figure 7B). The rate constant for Cc(Fe2+) oxidation with Y191:E232 is similar to that found in the single turnover experiments monitored by optical spectroscopy. Thus, addition of E232 perturbs the radical kinetics of CcP by increasing the rate of Y191• reduction and reducing the rate of Y191 oxidation. Attempts to probe the origin of the remote site by replacing other tyrosine residues in CcP were unfortunately problematic because they resulted in destabilized protein.

DISCUSSION

The Cpd I state of W191Y CcP is unable to support rapid ET from bound Cc(Fe2+),17 despite the replacement of Trp191 with Tyr causing little structural perturbation (PDB 5CIH). In fact, W191Y curtails Cc(Fe2+) oxidation to a degree similar to that of the redox-inactive W191F.65 The inactivity of CcP W191Y suggests that either the potential of Tyr• is too low to oxidize Cc(Fe2+) at appreciable rates (step II of Scheme 1) or Tyr reoxidation by the ferryl species of Cpd II is hindered (step III of Scheme 1).17 The data presented here demonstrate that the reduced reactivity of CcP W191Y is primarily due to the drop in potential of Tyr• caused by its deprotonation. Furthermore, W191Y CcP activity can be increased by incorporating a higher potential fluorotyrosine residue or by positioning an adjacent basic site to accept a proton from Y191 and hydrogen bond to the tyrosyl phenolic radical. Crystal structures, ENDOR, and ESEEM data all support the presence of a hydrogen-bonded Tyr• radical in Y191:E232 CcP. Substantial 2H-ESEEM signals at the Larmor frequency (approximately 2.3–2.6 MHz) indicate 2H-bonds to Y191•, similar to those reported for PS II YZ• and YD• samples.104,115,116 ESE-ENDOR 1H2O–2H2O difference spectra also reveal that exchangeable protons couple to the radical.

A hydrogen bond between Y191• and E232 suggests that rate enhancement by the conjugate base involves PCET. PCET reactions can proceed by stepwise electron-transfer, proton-transfer (ETPT), by proton-transfer, electron-transfer (PTET), or by concerted electron–proton transfer (CEPT) mechanisms.3,7 In the first case, ET is rate-limiting and rapid PT follows; in the second case PT is rate-limiting followed by ET; and in the last case, a transition state involving a combined proton and electron coordinate is involved. In small-molecule systems, CEPT behavior is often indicated by (i) large deuterium isotope effects (kH/kD > 2.0), (ii) a dependence of the rate on the donor–acceptor hydrogen bond difference, and (iii) a rate dependence on both ΔpKa and ΔE∘′.29-32,121 However, the model system reactions usually take place in nonaqueous solvents of relatively low dielectric and proton mobility, conditions that differ substantially from a protein in water.

Examining the rate dependence on the relative electron and proton affinities of the respective donors and acceptors can provide insight into the mechanism of a PCET reaction. For multisite PCET, the driving force can be considered as the difference between two X–H bond dissociation free energies: that for Y191-OH and the other for the combined oxidation of the one-electron donor and the proton transfer from the base (BH).31,122

| (2) |

| (3) |

where CG is a constant that reflects solvation effects for transferring H• as two components.39

For differences in driving force relative to a standard reaction (e.g., the Y191 parent):

| (4) |

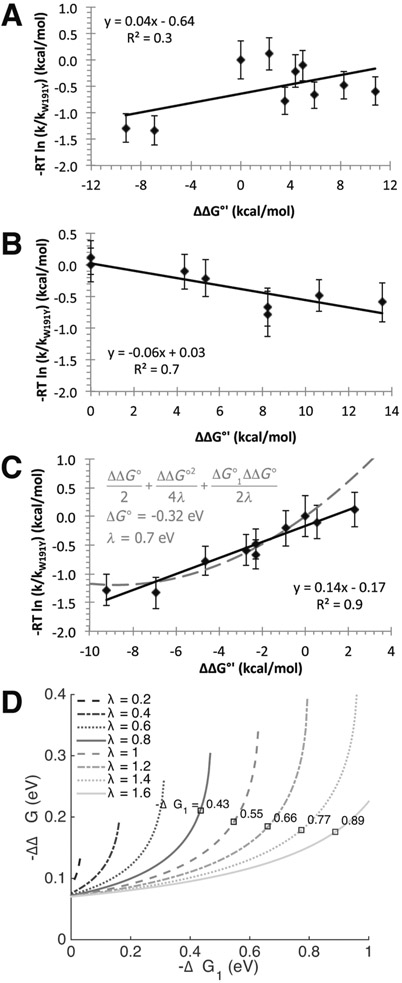

In a CEPT reaction, where both an electron and a proton transfer in the transition state, the rate constant often depends on both the pKa term and the formal potential term. This dual dependence is not observed for the oxidation of Cc(Fe2+) by Y191•; the rate constant only depends on the formal potential term (Figure 8; see Supplemental Table 3 for details and assumptions). Thus, the rate-limiting step in this reaction can be thought of as a purely ET process that then gates a subsequent proton transfer from solvent or a neighboring basic side chain. Under a Marcus ET analysis, the Brønsted α value relating changes in rate constant to changes in driving force is given by 31

| (5) |

where ΔG∘′1 represents the free energy for the oxidation of Cc(Fe2+) by Y191•, λ represents the reorganization energy, and ΔΔG∘′ represents perturbations to the driving force caused by alterations to Y191, its protic environment, or the Cc electron donor. For WT (W191) CcP, λ ≅ 0.7 V and − ΔG∘′1 ≅ 1.0 V.123,124 For CcP W191Y, if we assume −ΔG1∘′ ≅ 0.4 λ to 0.8 λ and ΔΔG∘′ is small, α ≅ 0.3 to 0.1. In keeping with a primarily ET mechanism, the slope α obtained by least-squares fitting a straight line is 0.14, with some apparent curvature at the largest values of ∣ΔG∘′∣ (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Brønsted linear free energy plots to evaluate possible contributions of PCET, PTET, and ETPT to Tyr191• reactivity; parameters are taken from Supplemental Table 3. Graph (A) shows poor correlation between ΔΔG* derived from the rate constants and the ΔΔG∘′ values calculated from eq 3. In plot (B), setting ΔE∘′ = 0 produces a modest negative correlation. However, if ΔΔpKa = 0, there is good agreement between the calculated changes, activation energy, and driving force (plot C), which indicates that the system is primarily affected by changes in ΔE∘′; proton affinity has little influence on the reactivity differences of different species. The gray dashed curve illustrates a reasonable fit to the Marcus relationship expressed by eq 5 with λ ≣ 0.7 eV, E∘′ (W191Y CcP) ≅ 0.61 eV, and R2 = 0.7. (D) Plot of reorganization energy isopleths (gray lines) as a function of driving force (between Cc(Fe2+) and Y191) and driving force perturbation from the addition of E232 to Y191 CcP, as calculated from interprotein ET rates. By Marcus theory, , where the single turnover reaction rate constants used are k1,obs = 0.05 s−1 and k2,obs = 0.19 s−1 for W191Y and W191Y:L232E CcP, respectively; ΔG∘′1 = E∘′(Cc) – E∘′ (W191Y CcP); and −ΔΔG∘′ is the change in formal potential of Y191• CcP with E232. Reorganization energy λ is assumed to be similar between variants. The sign of the root was chosen such that −ΔΔG∘′1 increases as −ΔG∘′1 increases; that is, the reaction is not in the Marcus inverted region. The square points denote values of ΔΔG∘′ for W191Y:L232E consistent with ΔG∘1 calculated from comparing single turnover rates between Y191 and CcP systems where −ΔΔG∘ is known. Using the Marcus relation above, ΔG∘′1 was calculated at different λ values and only plotted if there was consensus with the calculated isopleths. Values are shown for rate data of F3Y191 CcP (kobs = 0.07 s−1). This analysis provides a range of possible −ΔG∘′1 and corresponding λ values for the Y191 CcP:Cc system, giving an approximate −ΔΔG∘′ between 0.18 and 0.21 eV.

Thus, PT involving Y191 is not likely kinetically coupled to the rate-limiting, long-range ET reaction with Cc(Fe2+). Although the modest solvent isotope effect for Y191:E232 compared to the Y191 parent could indicate some degree of proton transfer in the transition state, D2O is known to order and stabilize the CcP:Cc complex.125 Thus, the hydrogen bond between Y191:E232 may be tighter in D2O and increase the perturbation to the Y191• formal potential experienced in the variant, thereby resulting in the observed isotope effect. Overall, we conclude that the modulation of ET rates seen with the various modifications made to the CcP:Cc complex largely owe to changes in the Y191• formal potential.

How much does the H-bond partner shift the Y191• potential? Considering the change in Cc oxidation rates with addition of E232 places constraints on the ET parameters of Y191• (Figure 7; Table 1). The change in Y191 formal potential can be derived from semiclassical theory provided that the reorganization energy lies within the limits of previously reported estimates.126-128 The reorganization energy for ET between CcP W191•+ and Cc(Fe2+) was calculated to be λ = 0.7 eV,127,129,130 though higher approximations of upward of 1.5 to 2 eV have been postulated.131-133 Taking the rate constants of single turnover reactions, the dependencies between −ΔG1∘′(Cc – Y191 CcP), −ΔΔG∘′(Y191•:E232 – Y191•), and λ can be attained by a Marcus relation. In conjunction with the F3Y191 CcP:Cc data, the solutions yield −ΔG1∘′/F ≅ 0.4 to 0.6 V for λ ≅ 0.8 to 1.2 V in the CcP:Cc system, along with the corresponding upshift in potential of − ΔΔG∘′(Y191•:E232 – Y191•)/nF ≅ 0.2 V (Figure 8D). Importantly, the model indicates that Cpd I of W191Y has a lower formal potential than that of WT. The individual Cpd I/Cpd II and Cpd II/Fe3+ potentials cannot be separated electrochemically, but the potential of the two-electron WT Cpd I/Fe3+ couple is ~0.75 V.123,124,134 The Cpd II (Fe4+═O)/Fe3+ potential from several other peroxidases ranges from 0.7 to 1.0 V.123,124,134 Rate data and Marcus considerations have been used to estimate the WT CcP Cpd I/Cpd II potential at ~1.0 V.135 Our data suggest that the Y191•:E232 formal potential is ~0.2 V higher than the potential of Y191• alone, but not as high as the WT W191•+ potential (Figure 9). Moreover, calculated hole migration maps by Gray and Winkler approximate the formal potentials of active proton-coupled Tyr radicals to be 1.0 V5. It follows that the W191•+ potential is closer to 1.0 V than 0.7 V, and ET reactions of Y191 and Y191:E232 reside in the normal Marcus regime (∣ΔG∘′1∣ < λ), unlike in the WT CcP:Cc system, which is predicted to be slightly inverted.127 Indeed, the ET rate constants for W191Y correlate well with increases in driving force and show no indication of inverted behavior (Figure 8).

Figure 9.

(A) Schematic of stepwise ETPT (black) and PTET (gray) mechanisms for Tyr oxidation. Data presented in Figure 8 support an ETPT pathway for Tyr• reduction by Cc(Fe2+) (gray; right to left). (B) Changes in Tyr191• formal potential owing to substitution by non-natural FTyr or addition of a hydrogen bond donor to the phenolic oxygen shown relative to the potentials of Cc(Fe2+)72 and CcP(Fe4+).123,124,136

The RFQ data also support a change in Y191 reactivity with the conjugate base that may reflect an upshifted formal potential for Y191:E232 compared to Y191 alone. These data illustrate a competition between Y191• oxidation of a remote site (radical migration) and oxidation of Cc(Fe2+) when Cc is limiting. kobs values from fitting of the RFQ data match those observed under single turnover conditions where Cc oxidation is monitored directly (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, kf values are likely larger for Y191:E232 compared to Y191 alone (although the initial fast phases of the curves are not well defined). Most notably, the rate constants for Tyr191 reoxidation (kr) differ substantially in the presence of E232. Thus, in Y191:E232, the radical does not return as readily to the 191 site for reduction by Cc as it does in Y191. In most scenarios, one would expect the conjugate base to either facilitate reoxidation of Y191 by the remote site or have little impact. However, the higher formal potential of YO•…HO-E232 compared to YO• may encourage oxidation of a different remote site, one that owing to the location or proximity of other reactive residues would more effectively propagate the radical away from Y191.

Change in the protonation state of the Y191• radical is important for its reactivity, even if the proton and electron transfers are not synchronous. Using a thermodynamic analysis, Mayer and co-workers estimated an increase of 0.2 to 0.3 V in the YZ•/YZ solution couple upon Tyr• protonation, which is similar to the range of values determined here for the effect of the E232 hydrogen bond on Y191• (Figures 8D and 9).137 However, Y191• is unlikely to be cationic in the E232 variant. A drop in pKa value from 10 to −2138 highly favors deprotonation of a Tyr radical cation, and where measured, deprotonation is indeed rapid.68 Furthermore, we would expect a greater perturbation on the ENDOR spectra of Y191• in the presence of E232 if the radical remained a cation. Additionally, the ESEEM spectra of Y191•:E232 closely match that of the photogenerated free Tyr• radical in solution, supporting the presence of an ordered hydrogen bond in this variant. A coordinating basic side chain would be expected to lower the pKa of neutral tyrosine and facilitate fast proton transfer upon oxidation.139 This effect can shift the position of an ET equilibrium when the driving force is close to zero, making a primarily ETPT mechanism still sensitive to the pKa of the coordinating base.25 In the PTET regime, the proton may equilibrate between Tyr• or the acceptor, with the protonated YOH•+ being the most competent for rapid ET. For PS II YZ, it has been proposed that a proton “rocks” between the tyrosyl radical and the coordinating side chain in a potential well to effectively upshift the YZ• potential.137,140,141 In the case of Cc oxidation by CcP Y191•, uncorrelated changes in rates and pKa values of the Tyr, or the coordinating base, suggest that neither perturbation of an ET equilibrium nor a PT pre-equilibrium is important; rather hydrogen bond donation from the acceptor after the proton transfer helps maintain a high enough potential for Y191• to rapidly oxidize Cc (Figure 9). Nonetheless, the reaction does show a pronounced pH dependence that likely reflects maintenance of this key hydrogen bond. Indeed, rate acceleration is lost at pHs above which the Y191•…H+-Glu/His deprotonates. For H232, ET rates return to values similar to those of the Y191 parent at pHs > 8.0; for E232, the threshold is lower (pH ≈ 7.0), in keeping with the relative pKas of these residues. The pH effects on the ESR line shapes, which we interpret to be indicative of hydrogen bond formation, follow this same trend (Figure 5A). These pH dependencies also rule against a mechanism where E232 rate enhancement derives from an acceleration or change in the equilibrium position of step III in Scheme 1, i.e., the oxidation of Y191 by the ferryl of Cpd II. In this case, the stronger base, His232, would be expected to increase rates of proton transfer to form Y191• and the rate enhancement should not diminish with increasing pH for either H232 or E232.

We have largely interpreted differences in ET for the W191Y system in terms of 191 site reactivity; however, implications of conformational gating also deserve comment. Although crystal structures of the native CcP:Cc complex reveal a well-defined association mode between the two proteins,59 considerable evidence indicates that a conformational ensemble of interacting states superimposes on the electrostatically driven 1:1 complex.54,142,143 Nonetheless, rapid ET to W191•+ in the WT system shows little indication of conformational gating when the proteins are associated.62 However, the lower ET rates of the 191 variants allow for Cc exchange and interfacial conformational fluctuations to potentially influence the observed ET rates.144 At lower ionic strength, second site binding and ternary complex formation further complicate Cc exchange.144 All of these factors can make the system quite sensitive to residue substitutions and changes in structure. Under the high ionic strength conditions studied here, variations to the 191 site, which is far removed from the interface, affect the ET rates without altering the configuration observed in the crystal structures. If interfacial conformational fluctuations are relatively fast, those that are ET inactive will weight the true ET rate constant by an equilibrium factor that should remain relatively constant among the variants.67 As the ET rates increase, such as in W191:E232, Cc off-rates may indeed begin to rate-limit Y191• reduction.

Catalytic tyrosine residues frequently interact with a neighboring proton acceptor (particularly Glu, Asp, His, or water), upon which radical formation and enzyme function depend.84,99,145-148 For example, loss of an adjacent histidine residue that hydrogen bonds to YZ• of PS II substantially reduces activity, yet the effect is rescued by the addition of imidazole and other small organic bases to solvent.101,146,149-151 A similar rate enhancement in the manganese-depleted apo-WT PS II suggests that additional hydrogen bonds from the solvent enhance YZ reactivity.150,152,153 Studies of RNR incorporated with amino-Tyr derivatives that trap radical states154 reveal that hydrogen bonds to Y have a marked effect on long-distance mutistep ET and conformational gating across the interface of the α/β subunits; furthermore, hydrogen bonds also control reactivity of the metal-center proximal Tyr122 residue.3,95,105,155 In prostaglandin H synthase and galactose oxidase, hydrogen bonds to tyrosyl radicals are critical for catalysis,156-158 as they are in flavin-containing BLUF photosensors.13,159,160 Efficient ET is also often desired in designed proteins,33,128,161-167 and although non-native Tyr or Trp residues have been introduced to improve functionality, the results have been mixed.168-170 In some cases, tuning the formal potential and pKa of Tyr radicals by adopting non-natural amino acids/prosthetic groups has aided reactivity,171-173 but such engineering often requires complex expression schemes. Solvent accessibility of the radical sites has proven to be an important parameter in the reactivity of Y• because PT to surrounding water molecules can compete with PT to neighboring side chains and disperse the proton source.174 If the proton is lost to bulk solvent, water molecules are usually unable to support rapid PT back to Tyr• owing to the unfavorable pKa difference and the high dependence of hydrogen bond strength on donor–acceptor distance, which is difficult to control in the absence of a stabilizing scaffold.29,138 As is shown here, a key parameter for effective ET in both natural and designed systems is maintaining a high-potential Tyr• radical, a condition that can be met by a well-positioned basic side chain within a solvent-protected environment.

CONCLUSION

A base that is positioned to accept a proton from YOH•+ and then donate this proton back in the form of a well-ordered hydrogen bond can substantially impact the ability of Tyr to act as a hole-hopping site. Although concerted PET may certainly be important in some enzymatic systems, modulation of the Tyr• formal potential by managing the immediate protic environment can alone exert substantial control over multisite PCET in proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by NSF grant MCB1715233 (to B.R.C.). We thank the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) and NE-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source for access to data collection facilities. CHESS is supported by NSF award DMR-1332208 and NIH/NIGMS award GM-103485. NE-CAT is supported by NIH/NIGMS awards P30 GM124165 and S10 RR029205. ACERT is supported by NIH/NIGMS awards P41 GM103521 and 1S1 0OD021543. Thanks to Harry Gray (Caltech) for insightful discussion; to Jon Caranto, Avery Vilbert, and Meghan Smith (Lancaster group; Cornell University) for assistance with rapid freeze quench; to Agnieszka Gil (Tonge lab; Stony Brook University) for guidance in fluorotyrosine preparation; and to Theo Esantsi (Cornell University) for help with protein preparation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b05715.

Materials and methods; Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 depicting kinetic traces of Cpd I formation and a structural superposition of WT CcP:Y48K Cc with WT CcP:WT Cc; and Supplementary Tables 1-3 containing turnover rate constants, X-ray collection and refinement statistics, and estimated PCET thermodynamic parameters

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Stubbe J; van der Donk WA Protein Radicals in Enzyme Catalysis. Chem. Rev 1998, 98 (2), 705–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hammarström L; Styring S Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer of Tyrosines in Photosystem II and Model Systems for Artificial Photosynthesis: The Role of a Redox-Active Link between Catalyst and Photosensitizer. Energy Environ. Sci 2011, 4 (7), 2379. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Migliore A; Polizzi NF; Therien MJ; Beratan DN Biochemistry and Theory of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev 2014, 114 (7), 3381–3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Barry BA Reaction Dynamics and Proton Coupled Electron Transfer: Studies of Tyrosine-Based Charge Transfer in Natural and Biomimetic Systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2015, 1847 (1), 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gray HB; Winkler JR Living with Oxygen. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51 (8), 1850–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Winkler JR; Gray HB Could Tyrosine and Tryptophan Serve Multiple Roles in Biological Redox Processes? Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A 2015, 373 (2037), 20140178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Reece SY; Nocera DG Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Biology: Results from Synergistic Studies in Natural and Model Systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2009, 78, 673–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Karthein R; Dietz R; Nastainczyk W; Ruf HH Higher Oxidation States of Prostaglandin H Synthase. EPR Study of a Transient Tyrosyl Radical in the Enzyme during the Peroxidase Reaction. Eur. J. Biochem 1988, 171 (1–2), 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Stubbe J Protein Radical Involvement In Biological Catalysis? Annu. Rev. Biochem 1989, 58 (1), 257–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sancar A Structure and Function of DNA Photolyase. Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2203–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Barry BA Proton Coupled Electron Transfer and Redox Active Tyrosines in Photosystem II. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2011, 104, 60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Müller P; Yamamoto J; Martin R; Iwai S; Brettel K Discovery and Functional Analysis of a 4th Electron-Transferring Tryptophan Conserved Exclusively in Animal Cryptochromes and (6–4) Photolyases. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (85), 15502–15505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kennis JTM; Mathes T Molecular Eyes: Proteins That Transform Light into Biological Information. Interface Focus 2013, 3 (5), 20130005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Winkler JR; Gray HB Electron Flow through Metalloproteins. Chem. Rev 2014, 114 (7), 3369–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Harriman A Further Comments on the Redox Potentials of Tryptophan and Tyrosine. J. Phys. Chem 1987, 91 (24), 6102–6104. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kless H; Vermaas W Combinatorial Mutagenesis and Structural Simulations in the Environment of the Redox-Active Tyrosine YZ of Photosystem II. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (51), 16458–16464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Payne TM; Yee EF; Dzikovski B; Crane BR Constraints on the Radical Cation Center of Cytochrome c Peroxidase for Electron Transfer from Cytochrome C. Biochemistry 2016, 55 (34), 4807–4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Warren JJ; Tronic TA; Mayer JM Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and Its Implications. Chem. Rev 2010, H0 (12), 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cukier R; Nocera DG Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 1998, 49, 337–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hammes-Schiffer S; Soudackov AV Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Solution, Proteins, and Electrochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112 (45), 14108–14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Saveant JM Concerted Proton-Electron Transfers: Fundamentals and Recent Developments. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 2014, 7, 537–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sjödin M; Styring S; Wolpher H; Xu Y; Sun L; Hammarström L Switching the Redox Mechanism: Models for Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer from Tyrosine and Tryptophan. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (11), 3855–3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Pizano AA; Yang JL; Nocera DG Photochemical Tyrosine Oxidation with a Hydrogen-Bonded Proton Acceptor by Bidirectional Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Chem. Sci 2012, 3 (8), 2457–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Costentin C; Robert M; Saveant JM; Tard C Inserting a Hydrogen-Bond Relay between Proton Exchanging Sites in Proton-Coupled Electron Transfers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49 (22), 3803–3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lennox JC; Dempsey JL Influence of Proton Acceptors on the Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reaction Kinetics of a Ruthenium-Tyrosine Complex. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121 (46), 10530–10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Natali M; Amati A; Demitri N; Iengo E Formation of a Long-Lived Radical Pair in a Sn(Iv) Porphyrin-Di(l-Tyrosinato) Conjugate Driven by Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer. Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (48), 6148–6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pannwitz A; Wenger OS Photoinduced Electron Transfer Coupled to Donor Deprotonation and Acceptor Protonation in a Molecular Triad Mimicking Photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (38), 13308–13311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Costentin C; Robert M; Savéant J-M Concerted Proton-Electron Transfers in the Oxidation of Phenols. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2010, 12 (37), 11179–11190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhang M-T; Irebo T; Johansson O; Hammarström L Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer from Tyrosine: A Strong Rate Dependence on Intramolecular Proton Transfer Distance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (34), 13224–13227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Glover SD; Parada GA; Markle TF; Ott S; Hammarström L Isolating the Effects of the Proton Tunneling Distance on Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in a Series of Homologous Tyrosine-Base Model Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (5), 2090–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Morris WD; Mayer JM Separating Proton and Electron Transfer Effects in Three-Component Concerted Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (30), 10312–10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Markle TF; Rhile IJ; Mayer JM Kinetic Effects of Increased Proton Transfer Distance on Proton-Coupled Oxidations of Phenol-Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (43), 17341–17352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Mayer JM; Rhile IJ; Larsen FB; Mader EA; Markle TF; DiPasquale AG Models for Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Photosystem II. Photosynth. Res 2006, 87 (1), 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bonin J; Robert M Photoinduced Proton-Coupled Electron Transfers in Biorelevant Phenolic Systems. Photochem. Photobiol 2011, 87 (6), 1190–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chararalambidis G; Das S; Trapali A; Quaranta A; Orio M; Halime Z; Fertey P; Guillot R; Coutsolelos A; Leibl W; Aukauloo A; Sircoglou M Water Molecules Gating a Photoinduced One-Electron Two-Protons Transfer in a Tyrosine/Histidine (Tyr/His) Model of Photosystem II. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57 (29), 9013–9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pannwitz A; Wenger OS Recent Advances in Bioinspired Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Dalt. Trans 2019, 48 (18), 5861–5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tommos C; Skalicky JJ; Pilloud DL; Wand AJ; Dutton PL De Novo Proteins as Models of Radical Enzymes. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (29), 9495–9507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wang M; Gao J; Müller P; Giese B Electron Transfer in Peptides with Cysteine and Methionine as Relay Amino Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48 (23), 4232–4234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Warren JJ; Winkler JR; Gray HB Redox Properties of Tyrosine and Related Molecules. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586 (5), 596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Pagba CV; McCaslin TG; Chi S-H; Perry JW; Barry BA Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer and a Tyrosine-Histidine Pair in a Photosystem II-Inspired β-Hairpin Maquette: Kinetics on the Picosecond Time Scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120 (7), 1259–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).McCaslin TG; Pagba CV; Hwang H; Gumbart JC; Chi SH; Perry JW; Barry BA Tyrosine, Cysteine, and Proton Coupled Electron Transfer in a Ribonucleotide Reductase-Inspired Beta Hairpin Maquette. Chem. Commun 2019, 55 (63), 9399–9402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).McEvoy JP; Brudvig GW Water-Splitting Chemistry of Photosystem II. Chem. Rev 2006, 106 (11), 4455–4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Nugent JHA; Ball RJ; Evans MCW Photosynthetic Water Oxidation: The Role of Tyrosine Radicals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2004, 1655 (1–3), 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Minnihan EC; Nocera DG; Stubbe J Reversible, Long-Range Radical Transfer in E. Coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase. Acc. Chem. Res 2013, 46 (11), 2524–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Oyala PH; Ravichandran KR; Funk MA; Stucky PA; Stich TA; Drennan CL; Britt RD; Stubbe J Biophysical Characterization of Fluorotyrosine Probes Site-Specifically Incorporated into Enzymes: E. Coli Ribonucleotide Reductase As an Example. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138 (25), 7951–7964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Greene BL; Taguchi AT; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Conformationally Dynamic Radical Transfer within Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (46), 16657–16665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Keinan S; Nocek JM; Hoffman BM; Beratan DN Interfacial Hydration, Dynamics and Electron Transfer: Multi-Scale ET Modeling of the Transient Myoglobin, Cytochrome b(5) Complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2012, 14 (40), 13881–13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Patel AD; Nocek JM; Hoffman BM Kinetic-Dynamic Model for Conformational Control of an Electron Transfer Photocycle: Mixed-Metal Hemoglobin Hybrids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112 (37), 11827–11837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Erman JE; Vitello LB; Mauro JM; Kraut J Detection of an Oxyferryl Porphyrin π-Cation-Radical Intermediate in the Reaction between Hydrogen Peroxide and a Mutant Yeast Cytochrome c Peroxidase. Evidence for Tryptophan-191 Involvement in the Radical Site of Compound I. Biochemistry 1989, 28 (20), 7992–7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Huyett JE; Doan PE; Gurbiel R; Houseman ALP; Sivaraja M; Goodin DB; Hoffman BM Compound ES of Cytochrome c Peroxidase Contains a Trp π-Cation Radical: Characterization by Continuous Wave and Pulsed Q-Band External Nuclear Double Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117 (35), 9033–9041. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Sivaraja M; Goodin D; Smith M; Hoffman B Identification by ENDOR of Trp191 as the Free-Radical Site in Cytochrome c Peroxidase Compound ES. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1989, 245 (4919), 738–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Wang KF; Mei HK; Geren L; Miller MA; Saunders A; Wang XM; Waldner JL; Pielak GJ; Durham B; Millett F Design of a Ruthenium-Cytochrome c Derivative to Measure Electron Transfer to the Radical Cation and Oxyferryl Heme in Cytochrome c Peroxidase. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (47), 15107–15119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mei HK; Wang KF; McKee S; Wang XM; Waldner JL; Pielak GJ; Durham B; Millett F Control of Formation and Dissociation of the High-Affinity Complex between Cytochrome c and Cytochrome c Peroxidase by Ionic Strength and the Low-Affinity Binding Site. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (49), 15800–15806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Bashir Q; Volkov AN; Ullmann GM; Ubbink M Visualization of the Encounter Ensemble of the Transient Electron Transfer Complex of Cytochrome c and Cytochrome c Peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (1), 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Nocek JM; Liang N; Wallin SA; Mauk AG; Hoffman BM Low-Temperature Conformational Transition within the Zn- Cytochrome-C Peroxidase, Cytochrome-C Electron-Transfer Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112 (4), 1623–1625. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Van de Water K; Sterckx YGJ; Volkov AN The Low-Affinity Complex of Cytochrome c and Its Peroxidase. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Volkov AN; van Nuland NAJ Solution NMR Study of the Yeast Cytochrome c Peroxidase: Cytochrome c Interaction. J. Biomol. NMR 2013, 56 (3), 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Volkov AN; Worrall JAR; Holtzmann E; Ubbink M Solution Structure and Dynamics of the Complex between Cytochrome c and Cytochrome c Peroxidase Determined by Paramagnetic NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (50), 18945–18950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Pelletier H; Kraut J Crystal-Structure of a Complex between Electron-Transfer Partners, Cytochrome-C Peroxidase and Cyto-chrome-C. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1992, 258 (5089), 1748–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Guo M; Bhaskar B; Li H; Barrows TP; Poulos TL Crystal Structure and Characterization of a Cytochrome c Peroxidase-Cytochrome c Site-Specific Cross-Link. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101 (16), 5940–5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Liang N; Mauk AG; Pielak GJ; Johnson JA; Smith M; Hoffman BM Regulation of Interprotein Electron-Transfer by Residue-82 of Yeast Cytochrome-C. Science (Washington DC, U. S.) 1988, 240 (4850), 311–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Mei HK; Wang KF; Peffer N; Weatherly G; Cohen DS; Miller M; Pielak G; Durham B; Millett F Role of Configurational Gating in Intracomplex Electron Transfer from Cytochrome c to the Radical Cation in Cytochrome c Peroxidase. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (21), 6846–6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Nocek JM; Hatch SL; Seifert JL; Hunter GW; Thomas DD; Hoffman BM Interprotein Electron Transfer in a Confined Space: Uncoupling Protein Dynamics from Electron Transfer by Sol-Gel Encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124 (32), 9404–9411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Nocek JM; Leesch VW; Zhou J; Jiang M; Hoffman BM Multi-Domain Binding of Cytochrome c Peroxidase by Cytochrome c: Thermodynamic vs. Microscopic Binding Constants. Isr. J. Chem 2000, 40 (1), 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Miller MA; Vitello L; Erman JE Regulation of Interprotein Electron Transfer by Trp 191 of Cytochrome c Peroxidase. Biochemistry 1995, 34 (37), 12048–12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Seifert JL; Pfister TD; Nocek JM; Lu Y; Hoffman BM Hopping in the Electron-Transfer Photocycle of the 1:1 Complex of Zn-Cytochrome c Peroxidase with Cytochrome C. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (16), 5750–5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Kang SA; Crane BR Effects of Interface Mutations on Association Modes and Electron-Transfer Rates between Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102 (43), 15465–15470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Nag L; Sournia P; Myllykallio H; Liebl U; Vos MH Identification of the TyrOH•+ Radical Cation in the Flavoenzyme TrmFO. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (33), 11500–11505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Diner BA Amino Acid Residues Involved in the Coordination and Assembly of the Manganese Cluster of Photosystem II. Proton-Coupled Electron Transport of the Redox-Active Tyrosines and Its Relationship to Water Oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2001, 1503 (1–2), 147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Mamedov F; Sayre RT; Styring S Involvement of Histidine 190 on the D1 Protein in Electron/Proton Transfer Reactions on the Donor Side of Photosystem II. Biochemistry 1998, 37 (40), 14245–14256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Tommos C; Hoganson CW; Di Valentin M; Lydakis-Simantiris N; Dorlet P; Westphal K; Chu H-A; McCracken J; Babcock GT Manganese and Tyrosyl Radical Function in Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 1998, 2 (2), 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Lett CM; Guillemette JG Increasing the Redox Potential of Isoform 1 of Yeast Cytochrome c through the Modification of Select Haem Interactions. Biochem. J 2002, 362 (2), 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Seyedsayamdost MR; Reece SY; Nocera DG; Stubbe J Mono-, Di-, Tri-, and Tetra-Substituted Fluorotyrosines: New Probes for Enzymes That Use Tyrosyl Radicals in Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (5), 1569–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Minnihan EC; Young DD; Schultz PG; Stubbe J Incorporation of Fluorotyrosines into Ribonucleotide Reductase Using an Evolved, Polyspecific Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthetase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (40), 15942–15945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Ravichandran KR; Zong AB; Taguchi AT; Nocera DG; Stubbe JA; Tommos C Formal Reduction Potentials of Difluorotyrosine and Trifluorotyrosine Protein Residues: Defining the Thermodynamics of Multistep Radical Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (8), 2994–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Gil AA; Laptenok SP; Iuliano JN; Lukacs A; Verma A; Hall CR; Yoon GE; Brust R; Greetham GM; Towrie M; French JB; Meech SR; Tonge PJ Photoactivation of the BLUF Protein PixD Probed by the Site-Specific Incorporation of Fluorotyrosine Residues. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (41), 14638–14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Rappaport F; Boussac A; Force DA; Peloquin J; Brynda M; Sugiura M; Un S; Britt RD; Diner BA Probing the Coupling between Proton and Electron Transfer in Photosystem II Core Complexes Containing a 3-Fluorotyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131 (12), 4425–4433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Mathes T; Van Stokkum IHM; Stierl M; Kennis JTM Redox Modulation of Flavin and Tyrosine Determines Photoinduced Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer and Photoactivation of BLUF Photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287 (38), 31725–31738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Ishikita H Tyrosine Deprotonation and Associated Hydrogen Bond Rearrangements in a Photosynthetic Reaction Center. PLoS One 2011, 6 (10), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Li H; Robertson AD; Jensen JH Very Fast Empirical Prediction and Rationalization of Protein PKa Values. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 2005, 61 (4), 704–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Wang JM; Mauro M; Edwards SL; Oatley SJ; Fishel LA; Ashford VA; Xuong N; Kraut J X-Ray Structures of Recombinant Yeast Cytochrome c Peroxidase and Three Heme-Cleft Mutants Prepared by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 7160–7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Goodin DB; McRee DE The Asp-His-Fe Triad of Cytochrome c Peroxidase Controls the Reduction Potential, Electronic-Structure, and Coupling of the Tryptophan Free-Radical to the Heme. Biochemistry 1993, 32 (13), 3313–3324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Choudhury K; Sundaramoorthy M; Hickman A; Yonetani T; Woehl E; Dunn MF; Poulos TL Role of the Proximal Ligand in Peroxidase Catalysis. Crystallographic, Kinetic, and Spectral Studies of Cytochrome c Peroxidase Proximal Ligand Mutants. J. Biol. Chem 1994, 269 (32), 20239–20249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]