Abstract

Conserving genetic diversity in rare and narrowly distributed endemic species is essential to maintain their evolutionary potential and minimize extinction risk under future environmental change. In this study we assess neutral and adaptive genetic structure and genetic diversity in Brasilianthus carajensis (Melastomataceae), an endemic herb from Amazonian Savannas. Using RAD sequencing we identified a total of 9365 SNPs in 150 individuals collected across the species’ entire distribution range. Relying on assumption-free genetic clustering methods and environmental association tests we then compared neutral with adaptive genetic structure. We found three neutral and six adaptive genetic clusters, which could be considered management units (MU) and adaptive units (AU), respectively. Pairwise genetic differentiation (FST) ranged between 0.024 and 0.048, and even though effective population sizes were below 100, no significant inbreeding was found in any inferred cluster. Nearly 10 % of all analysed sequences contained loci associated with temperature and precipitation, from which only 25 sequences contained annotated proteins, with some of them being very relevant for physiological processes in plants. Our findings provide a detailed insight into genetic diversity, neutral and adaptive genetic structure in a rare endemic herb, which can help guide conservation and management actions to avoid the loss of unique genetic variation.

Keywords: Brasilianthus carajensis, conservation genomics, environmental association tests (EAT), evolutionary significant unit, genotype–environment association (GEA), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

Rare and narrowly distributed plants are particularly sensitive to the loss and fragmentation of their natural habitats, which ultimately result in reduced genetic diversity and a weakened ability to adapt to changing environments. In this study we evaluated the genetic health of a narrowly distributed herb from Amazonian Savannas. Relying on Next-Generation Sequencing technologies we were able to take a detailed glance at a representative portion of the plant’s whole genome, assessing genetic diversity, genetic composition and adaptations to local environmental conditions. Our results provide clear guidance on how to avoid the loss of unique genetic variation in this unique plant.

Introduction

The assessment of population genetic structure has frequently been employed to delineate conservation units (Moritz 1994; Frankham et al. 2017; Coates et al. 2018). Evolutionary significant units (ESU), broadly defined as independent demographic entities or groups exhibiting high genetic distinctiveness due to historical isolation, have traditionally been the most commonly discussed types of conservation units (Frankham et al. 2017; Coates et al. 2018). These are delimited based on neutral genetic variation (which is not subject to natural selection), and thus mainly reflect the interplay between gene flow and genetic drift (Holderegger et al. 2006; Funk et al. 2012). The advance of Next-Generation Sequencing technologies has made possible large-scale assessments of adaptive genetic variation, which can also inform management actions (Funk et al. 2012). For instance, genetic variation that is exposed to natural selection (and thus underlies fitness-related traits) can exhibit different spatial patterns than those shown by neutral genetic variation (Van Wyngaarden et al. 2017; Barbosa et al. 2018), and provides valuable insights on how likely individuals are to survive under certain environmental conditions and the strength of local adaptations across real landscapes (Moritz 1999; McKay et al. 2005; Edmands 2007; Frankham et al. 2017). However, while a few studies have assessed both neutral and adaptive genetic differentiation in economically important species (Moore et al. 2014; Candy et al. 2015; Batista et al. 2016; Van Wyngaarden et al. 2017; Gugger et al. 2018; Jaffé et al. 2019), less have done so in species of conservation concern (Rodríguez-Quilón et al. 2016; Barbosa et al. 2018; Martins et al. 2018; Borrell et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019).

Recent calls for a paradigm shift in the genetic management of fragmented populations highlight the importance of assessing both neutral and adaptive genetic variation to delineate management units (MU) and adaptive units (AU, see definitions in Funk et al. 2012 and Frankham et al. 2017), and examine the risks and benefits of separate or joint management alternatives (Frankham et al. 2017; Funk et al. 2018; Ralls et al. 2018). Following the recommendations made by Frankham et al. (2017, page 216), populations should be managed separately when they show adaptive differentiation, as the risk of outbreeding depression resulting from crossing individuals from different AU is usually high. In the absence of adaptive differentiation the risk of outbreeding depression is low, so there is no need for separate management. Genetic rescue, or the re-establishment of gene flow between populations aiming to reverse the loss of genetic diversity, is only recommended under neutral genetic differentiation without adaptive differentiation, in situations where MU are suffering from genetic erosion or inbreeding depression.

Narrowly distributed endemic species constitute prime targets for conservation genomic assessments, because they often have small population sizes and are thus more exposed to genetic drift, have lower genetic diversity, higher inbreeding and slower adaptive responses (Hamrick et al. 1991; Gitzendanner and Soltis 2000; Cole 2003; Leimu et al. 2006; Gibson et al. 2008; Allendorf et al. 2013). One example of a narrow endemism of conservation concern, Brasilianthus carajensis (Melastomataceae), stands out for being a monotypic plant genus from the Amazonian Savannas of the Carajás mineral province (Mota et al. 2015; Viana et al. 2016). This mountainous complex from the Eastern Amazon is composed of banded ironstone formations (known as Cangas), and displays a very distinct vegetation that resembles Montane Savannas (Mota et al. 2015; Silveira et al. 2016; de Carvalho and Mustin 2017). The acidic, shallow, nutrient-poor, metal-rich soils with high surface temperatures, characteristic of these environments (Skirycz et al. 2014), associated with severe drought periods (Mota et al. 2015), impose severe challenges for plant growth. These extreme conditions are believed to be an important force driving local endemism (Mota et al. 2015; Salas et al. 2015; Cavalcanti et al. 2016), which represents about 4 % of all Canga flora (Giulietti et al. 2019). The high concentration of iron ore has also attracted considerable attention from mining companies (Skirycz et al. 2014), and approximately 20 % of the areas occupied by Canga vegetation have already been lost due to conversion to mining areas or pasturelands (Souza-Filho et al. 2019). In addition, species from mountainous habitats are particularly threatened by climate change since future conditions are likely to reduce occurrence range and leave little or none suitable habitat (Dullinger et al. 2012).

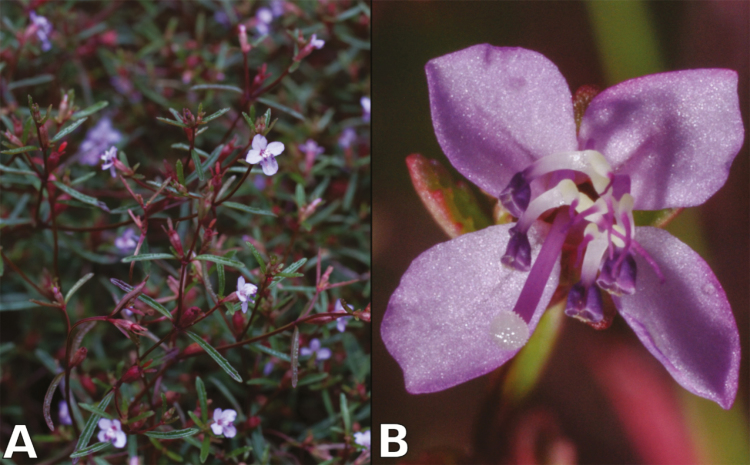

Brasilianthus carajensis was only recently described as a new species, and is a small annual herb with four-merous flowers, wide truncate apical pore in the anthers with staminal appendages, and capsular fruit (Almeda et al. 2016) (Fig. 1). Fruit morphology indicates that seed dispersal is mediated by the wind, like other Melastomataceae species with capsular fruit (Renner 1989), whereas flowers are apparently pollinated by insects (Rocha et al. 2017). A recent landscape genomic study revealed that gene flow in this species is mainly influenced by geographic distance, terrain roughness and climate, and suggested it is resilient to habitat loss driven by mining (Carvalho et al. 2019). However, adaptive genetic structure has not been examined yet, and proxies for genetic diversity like nucleotide diversity and effective population size are still lacking for this species. This information is nevertheless essential to delineate MU and AU, assess the risk of inbreeding and outbreeding depression and define management actions in this rapidly changing environment (Jamieson and Allendorf 2012; Frankham et al. 2017; Ralls et al. 2018).

Figure 1.

Brasilianthus carajensis bush (A) and flower front view (B).

In this study, we used the genomic resources generated for B. carajensis in a previous study (Carvalho et al. 2019) to assess genetic diversity, neutral and adaptive genetic structure across the species’ entire distribution range. Considering the narrow and naturally fragmented distribution of B. carajensis across Montane Savanna highlands and the scarce life history information available, we expected to find low genetic diversity and high neutral genetic structure, mostly associated with distinct Canga plateaus. Additionally, due to the heterogeneous (Mitre et al. 2018) and hostile environment where the species occurs, we expected to find loci associated to environmental conditions and differing neutral and adaptive genetic structure. We identify MU and AU and discuss possible management options to prevent the loss of unique genetic variation and increase the species resilience to future environmental change.

Materials and Methods

Genomic data

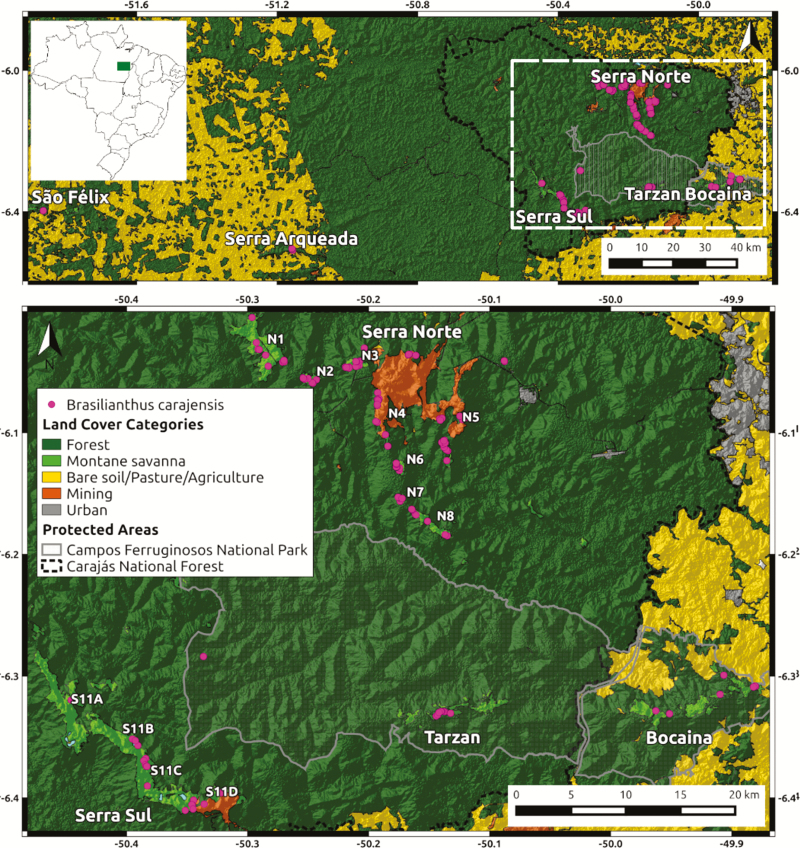

We used the genomic data generated by Carvalho et al. (2019) and publicly available in FigShare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8224175.v3. Briefly, 150 individuals of B. carajensis were collected from all the major Montane Savanna highlands of the Carajás mineral province (SISBIO collection permit N. 48272-4), encompassing the entire species’ distribution range (Rocha et al. 2017) (Fig. 2). We sampled individuals separated by at least 20 m from each other to avoid collecting siblings. Vegetative branches of young plants were silica-dried at room temperature. Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB 2 % method (Doyle 1987) without phenol and subsequently purified by precipitation of polysaccharides (Michaels et al. 1994). DNA integrity was assessed through 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis, DNA concentration was quantified using the Qubit High Sensitivity Assay kit (Invitrogen) and all samples were adjusted to a final concentration of 5 ng µL−1. DNA samples were shipped to SNPSaurus (http://snpsaurus.com/) for sequencing and bioinformatic processing. The nextRAD libraries were prepared (Russello et al. 2015) and sequenced on four lanes of a HiSeq 4000 generating single-end 150 bp reads (University of Oregon). Raw data processing used custom scripts (SNPsaurus, LLC). First, reads were trimmed using bbduk from BBMap tools (Bushnell 2019). Second, de novo reference contigs were created by collecting a total of 10 million reads, evenly distributed across samples, after excluding reads with depth lower than five or higher than 700. Third, the remaining reads were aligned to each other to identify alleles and collapse haplotypes to a single representative. Finally, all reads were mapped to the reference with an alignment identity threshold of 90 % using bbmap (BBMap tools). Genotype calling was done using Samtools and bcftools. Alleles with a population frequency of less than 3 % were removed, and loci that were heterozygous in all samples or had more than two alleles in a sample (suggesting collapsed paralogs) were discarded.

Figure 2.

Maps of the study area showing the location of the collected samples from Brasilianthus carajensis. A hillshade elevation map (from USGS Earth Explorer) is shown overlaid with a land cover colour map (from Souza-Filho et al. 2016). Coordinates are shown in decimal degrees. While the upper map shows the full extent of our study region (and its location within Brazil), the lower map expands the area within the white-dashed square to detail the main Montane Savanna highlands and mining areas.

Genetic diversity and neutral genetic structure

Genotype data were submitted to a final quality control using VCFtools (Danecek et al. 2011), executed through the r2vcftools R package (https://github.com/nspope/r2vcftools). Loci were filtered for quality (Phred score > 50), read depth (30 – 240), linkage disequilibrium (LD, R2 < 0.6) and deviations from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). For HWE filtering, the data were initially subdivided into large geographic groups (to better meet the assumptions of idealized populations), and loci showing strong deviations (P < 0.0001) in any of these groups were excluded. Additionally, we removed loci potentially under selection conducting a genomic scan analysis implemented in the R package LEA (Frichot and François 2015). This analysis compares single-locus estimates of population differentiation with the overall genome-wide background, while accounting for population structure. We controlled for false discovery rates by adjusting P-values with the genomic inflation factor (λ) and setting false discovery rates to q = 0.05, using the Benjamini–Hochberg algorithm (François et al. 2016).

The assumptions underlying commonly employed genetic clustering software like STRUCTURE (a Bayesian approach) or ADMIXTURE (based on maximum likelihood estimation) include absence of genetic drift, existence of HWE and lack of LD in ancestral populations (Frichot et al. 2014). These genetic clustering approaches are thus not suited to assess adaptive genetic structure, given that adaptive loci are often in LD (as they are linked to neighbouring genes under selection), and frequently depart from the HWE (Hartl and Clark 2006). We therefore employed two alternative assumption-free genetic clustering methods to assess and compare neutral and adaptive genetic structure: discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) (Jombart et al. 2010) and spatial principal component analysis (sPCA) (Jombart et al. 2008). Both assumption-free methods were performed using the R package adegenet (Jombart 2008). In DAPC, the user informs the number of clusters (in this case, ranging from 1 to 20) and genomic variation is maximized among groups, with the optimal number of clusters being inferred from the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Individuals were assigned to genetic clusters based on the ancestry coefficients retrieved from DAPC analyses. In sPCA, genetic structure is estimated from scores summarizing genetic variability which also account for the geographic location of samples, thus representing the spatial pattern of genetic variability. To decide if global and/or local structures should be interpreted and thus retained in sPCA analyses, we used the global and local tests implemented in adegenet as proposed by Jombart (2008). The first three retained axes where then interpolated on 10-m resolution grids covering our study area, and the resulting rasters used to create an RGB composite, using the Merge function in QGIS 3.4 (see example scripts here: https://github.com/rojaff/LanGen_pipeline). The resulting colour patterns represent the similarity in adaptive genetic composition. Finally, to visualize admixture in neutral genetic clusters, we calculated ancestry coefficients using the snmf function from the LEA package and plotted them for each individual, as in classical STRUCTURE-like figures (Frichot and François 2015).

Aiming to characterize genetic diversity within each demographic unit, the following metrics were calculated for each neutral genetic cluster: expected heterozygosity (HE), inbreeding coefficients (F), nucleotide diversity (π) and effective population size (Ne). While the former three were calculated using the ‘het’ option in VCFtools implemented in r2vcftools (Danecek et al. 2011), Ne was estimated employing the LD approach of NeEstimator 2.0.1, with the lowest allele frequency value set to 0.05 (Do et al. 2014). Pairwise genetic differentiation between genetic clusters (FST) was also estimated using r2vcftools. Additionally, we calculated Tajima’s D, representing the difference between the mean number of pairwise differences and the number of segregating sites. Negative values of Tajima’s D show that a cluster has an excess of rare alleles, indicating a recent selective sweep or a population expansion after a recent bottleneck. Positive values appear when rare alleles are lacking, therefore suggesting balancing selection or a sudden population contraction. In a population of constant size evolving under mutation-drift equilibrium Tajima’s D is expected to be zero (Tajima 1989). Genome-wide estimates of Tajima’s D were computed using r2vcftools package, which performs a simulation from the neutral model to correct for bias due to the minor-allele-frequency filter.

Identification of putative adaptive loci and adaptive genetic structure

Several environmental variables have been identified as drivers of local adaptation in plants, including climatic factors like temperature, precipitation and radiation (Eckert et al. 2010; Manel et al. 2012; De Kort et al. 2014), as well as soil characteristics (Supple et al. 2018). Lacking high-resolution soil layers for our study region, here we could only assess genotype associations with the commonly employed bioclimatic variables (http://www.worldclim.org/bioclim). We selected a set of orthogonal environmental variables, running a PCA on all 19 WorldClim bioclimatic variables plus elevation (Fick and Hijmans 2017). The variables showing the strongest correlation with the first three PCA axes (85 % of total variance explained) were selected (Minimum Temperature of the Coldest Month, Maximum Temperature of the Warmest Month and Precipitation of the Wettest Quarter) to perform environmental association tests. We then ran latent factor mixed models (LFMM), employing the original genomic data set filtered only by quality and depth, but not for LD (as LFMM remove the effect of relatedness and genetic linkage when inferring ecological associations; François et al. 2016) nor for HWE (as loci under selection are expected to depart from HWE). Latent factor mixed models have been used extensively and are currently one of the most commonly used Environmental Association Analysis approaches (Ahrens et al. 2018), since they provide a good compromise between detection power and error rates, and are robust to a variety of sampling designs and underlying demographic models (Rellstab et al. 2015). Latent factor mixed models were implemented using the lfmm function from the LEA package (Frichot and François 2015) with k = 3 latent factors, where k was the optimal number of ancestral populations detected (see results). We used 1000 iterations, a burn-in of 10 000 and 10 runs per environmental variable (Frichot and François 2015). The P-values were adjusted using the genomic inflation factor (λ) and false discovery rates were set using the Benjamini–Hochberg algorithm at a rate of q = 0.05 (François et al. 2016). We then ran the same methods described above to assess neutral genetic structure (DAPC and sPCA) but this time employed only putative adaptive SNPs identified with LFMM. In order to visualize genotype–environment associations, we performed a redundancy analysis (RDA) using only the candidate loci identified in LFMM and the same three climatic variables. To do so we first imputed missing genotypes (20 %) based on population assignments, using snmf and the impute function from the LEA package. Redundancy analysis was then performed using the rda function from the Vegan package (Oksanen et al. 2019), and the first two constrained axes were plotted using different colours to represent Canga plateaus.

We further investigated the functions of putative adaptive loci. Sequences (RAD contigs) containing putative adaptive SNPs were submitted to the EMBOSS Transeq (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/st/emboss_transeq/) to obtain the corresponding protein sequences coded by genes contained in the flanking regions of our candidate SNPs. We used all six frames with standard code (codon table), regions (start–end), trimming (yes) and reverse (no). We then ran a functional analysis using InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/; Mitchell et al. 2018), searching for GO terms and pathways along the respective annotation databases (Interpro, Pfam, Tigrfam, Prints, PrositePattern and Gene3d).

Results

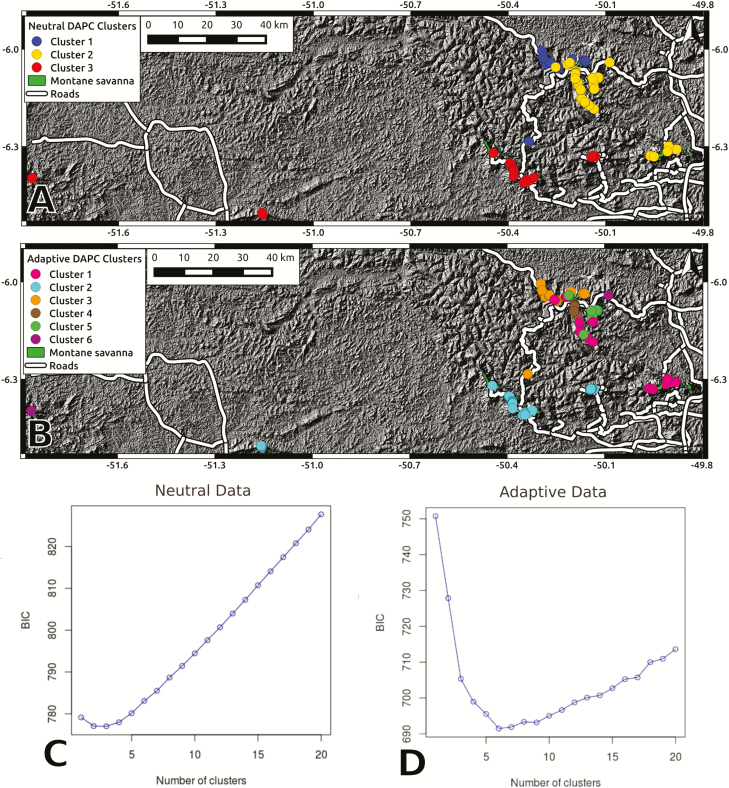

From a total of 9365 SNPs identified in the 150 sampled individuals, we kept 1911 neutral SNPs after filtering for quality, depth, LD, HWE and FST outlier loci. Neutral genetic structure assessed through DAPC revealed three genetic clusters (Fig. 3A), whereas a more pronounced spatial structure was observed when interpolating the first three spatial principal components (sPCA; Fig. 4A). While effective population sizes were below 100 in all genetic clusters (ranging from 49 to 77), none revealed significant inbreeding (Table 1). Cluster 2 showed negative Tajima’s D values, indicative of a population expansion following a recent bottleneck (Table 1). Pairwise genetic differentiation (FST) between neutral clusters ranged between 0.024 and 0.048 and substantial admixture was detected [seeSupporting Information—Fig. S1].

Figure 3.

Discriminant analysis of principal component genetic cluster assignments for neutral (A) and putative adaptive (B) markers against a hillshade elevation map (from USGS Earth Explorer) and roads (from IBGE and Vale SA). Bayesian Information Criterion plots show the optimal number of neutral (C) and adaptive (D) genetic clusters.

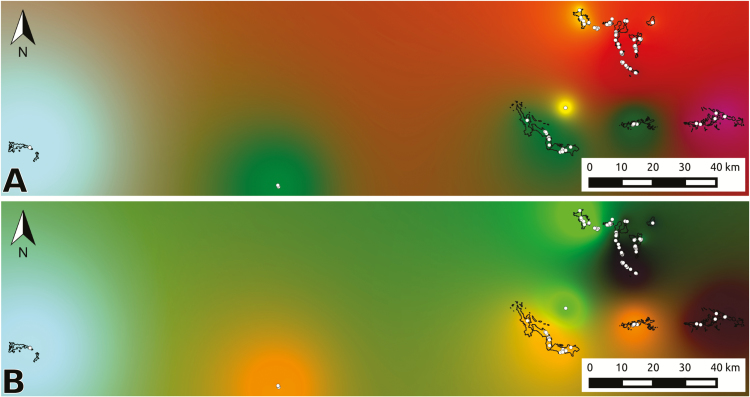

Figure 4.

Spatial patterns of neutral (A) and adaptive (B) genetic variation. Maps show the resulting RGB composites created from the interpolated spatial principal component analysis components, and samples are shown as white dots. Areas with similar colours represent similar neutral or adaptive genetic composition.

Table 1.

Genetic diversity measures for the identified neutral genetic clusters. The number of sampled individuals (N) is followed by mean expected heterozygosity (HE), mean inbreeding coefficient (F), mean per-site nucleotide diversity (π), effective population size (Ne) and Tajima’s D. All estimates are shown along 95 % confidence intervals (CI).

| Clusters | N | H E (CI) | F (CI) | π (CI) | N e (CI) | Tajima’s D (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster1 | 24 | 0.25 (0.25/0.25) | 0.00 (−0.08/0.08) | 0.16 (0.16/0.17) | 72.1 (67.8/76.9) | −0.03 (−0.19/0.14) |

| Cluster2 | 89 | 0.21 (0.21/0.22) | −0.02 (−0.07/0.01) | 0.20 (0.19/0.21) | 76.9 (75.8/78.0) | −0.34 (−0.52/−0.16) |

| Cluster3 | 37 | 0.24 (0.24/0.24) | 0.06 (−0.01/0.13) | 0.19 (0.19/0.20) | 48.7 (47.3/50.1) | 0.07 (−0.04/0.26) |

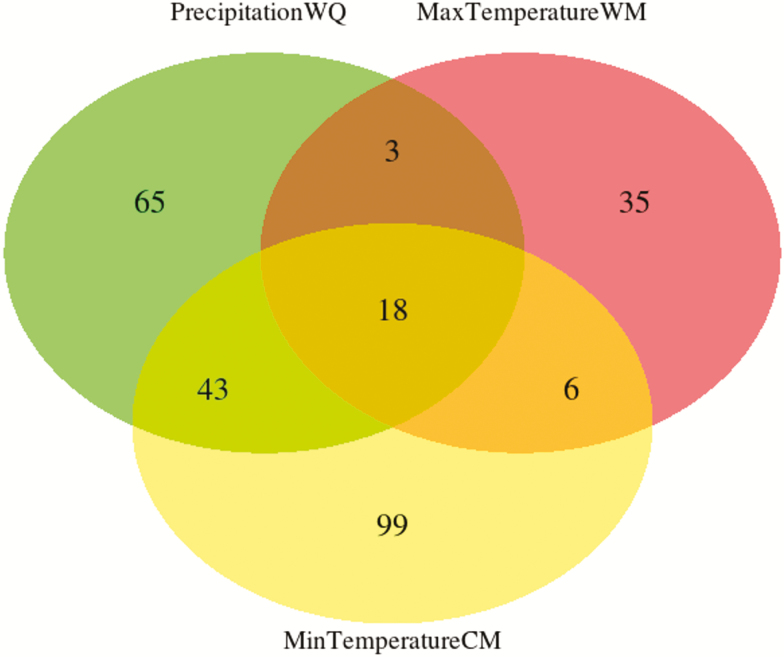

Nearly 10 % of all analysed sequences contained putative adaptive SNPs (Table 2), most of them associated with minimum temperature of the coldest month, while 18 sequences contained SNPs associated with all environmental variables (Fig. 5). Adjusted P-values for genotype–environment associations ranged between 0.05 and 1 × 10−8, and revealed stronger associations with precipitation of the wettest quarter and minimum temperature of the coldest month [seeSupporting Information—Fig. S2]. Only 25 sequences contained InterPro annotations and two annotated genes were shared between all environmental variables (Table 3). Adaptive genetic structure assessed through DAPC revealed six genetic clusters (Fig. 3B), and a less pronounced spatial structure was found when using the sPCA approach (Fig. 4B). Redundancy analysis revealed that 18.8 % of adaptive variation was associated with climatic variables (P = 0.001), with individuals from Serra Norte and Bocaina showing genotype associations with higher temperatures and higher precipitation levels [seeSupporting Information—Fig. S3].

Table 2.

Number of adaptive signals detected employing environmental association tests. The number of candidate SNPs and sequences (RAD contigs) containing candidate SNPs are shown for each environmental variable. Numbers in parentheses represent independent (non-overlapping) detections. aGenomic inflation factor (λ) = 1.45; bλ = 0.65; cλ = 1.5.

| Signal type | Total analysed | Total under selection | Environmental association tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation WQa | Max temperature WMb | Min temperature CMc | |||

| SNPs | 9253 | 768 | 385 (181) | 174 (82) | 501 (273) |

| RAD contigs | 2547 | 269 | 129 (65) | 62 (35) | 166 (99) |

Figure 5.

Venn diagram showing the number of sequences (RAD contigs) containing candidate SNPs associated with each environmental variable (Minimum Temperature of Coldest Month in yellow, Maximum Temperature of Warmest Month in red and Precipitation of Wettest Quarter in green) or with more than one variable (values in intersections).

Table 3.

Annotated putative adaptive proteins. *Proteins also identified as putative adaptive in other plant species from Carajás (Lanes et al. 2018).

| Climatic variable | Signature description |

|---|---|

| Precipitation of Wettest Quarter | Serine-threonine/tyrosine-protein kinase catalytic domain* |

| Papain family cysteine protease, peptidase C1A, papain C-terminal | |

| No apical meristem (NAM) protein, NAC domain | |

| Homeobox-associated leucine zipper | |

| NAD(P)-binding domain* | |

| Phosphoesterase | |

| Fatty acid desaturase domain | |

| Max Temperature of Warmest Month | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase-like domain* |

| Transferase | |

| FAD-linked oxidase, N-terminal, FAD-binding domain* | |

| CO dehydrogenase flavoprotein-like, FAD-binding, subdomain 2 | |

| Squalene epoxidase | |

| FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain* | |

| Homeobox-associated leucine zipper | |

| Serine-threonine/tyrosine-protein kinase catalytic domain* | |

| Min Temperature of Coldest Month | Homeobox-associated leucine zipper |

| Enolase C-terminal domain-like | |

| Alpha/beta hydrolase fold | |

| Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase-like domain* | |

| Transferase | |

| Photosystem II Psb28, class 1 | |

| Glutathione S-transferase, C-terminal-like | |

| Serine-threonine/tyrosine-protein kinase catalytic domain* | |

| No apical meristem (NAM) protein, NAC domain | |

| Sodium:solute symporter family |

Discussion

This study assessed genetic diversity, neutral and adaptive genetic structure in 150 individuals from B. carajensis collected across the species’ currently known distribution range. While neutral genetic structure indicated the presence of at least three discrete genetic clusters, six adaptive genetic clusters were found. Despite the small estimated effective population sizes, genetic diversity was similar to that found in other plant species occurring in the region, and none of the neutral clusters showed significant inbreeding. In addition, around 10 % of the analysed sequences contained putative adaptive SNPs associated with environmental variables, revealing different selective pressures in a narrowly distributed species. Below we discuss our findings, and show how combining information derived from neutral and adaptive genomic markers can help guide conservation efforts.

Levels of genetic diversity observed for B. carajensis were generally higher or similar to those observed for other patchily distributed herbs, shrubs and trees (Mosca et al. 2012; Jennings et al. 2016; Lanes et al. 2018; Carvalho et al. 2019; Resende-Moreira et al. 2019). Heterozygosity and nucleotide diversity were similar or higher than those found in two sympatric morning glories (Lanes et al. 2018), although effective population sizes were an order of magnitude lower in B. carajensis. Despite these small effective population sizes (all below 100), the lack of inbreeding, the low levels of genetic differentiation and the existence of admixture among the studied populations suggest there is no short-term risk of inbreeding depression (Kirk and Freeland 2011; Jamieson and Allendorf 2012).

Our study reveals at least three neutral genetic clusters, generally associated with multiple Montane Savanna plateaus (Figs 3A and 4A). In contrast, neutral genetic structure was strongly associated with Canga plateaus in a sympatric but broadly distributed morning glory (Lanes et al. 2018). Since Tajima’s D values did not depart from zero in clusters 1 and 3, suggesting constant population sizes evolving under mutation-drift equilibrium, we cannot attribute the spatial pattern of cluster 2 to an ancient population expansion (as suggested by the negative Tajima’s D values) (Sabeti et al. 2006). The fact that all neutral genetic clusters span multiple Canga plateaus, together with the high observed admixture among genetic clusters [seeSupporting Information—Fig. S1] and low pairwise FST values, suggest long-distance dispersal. Indeed, a recent landscape genomic study found that gene flow in B. carajensis is mainly influenced by geographic distance, implying that forested areas surrounding the plateaus do not represent important barriers to gene flow (Carvalho et al. 2019).

Wind dispersal is one of the most common long-distance dispersal mechanisms, often driven by extreme events such as rare weather conditions (Soons et al. 2004). Montane Savanna highlands from Carajás are characterized by strong winds, which could certainly facilitate the colonization of distant plateaus by B. carajensis as well as enhance genetic connectivity between them (Nathan 2006; Carvalho et al. 2019). For instance, a study investigating another bee-pollinated Melastome species found long-distance pollen dispersal, reaching up to 3 km (Castilla et al. 2017). In addition, anthropogenic interference could also contribute to long-distance dispersal events in our studied species. There are many examples of humans acting as both active and passive plant dispersal vectors, allowing different types of seeds to reach very long distances and resulting in introgression (Auffret et al. 2014; Bullock et al. 2018). The small and abundant seeds of the B. carajensis (Almeda et al. 2016) are resistant to desiccation (they survive throughout the dry season), and can germinate in different substrates, characteristics that increase the likelihood of human-mediated dispersal (Bullock et al. 2018; Carvalho et al. 2019). Moreover, Canga plateaus are connected by roads and there is a frequent transit of vehicles in the area (Fig. 3A), which could facilitate human-mediated gene flow through the transportation of seeds in shoes or car tires (Von Der Lippe and Kowarik 2007; Wichmann et al. 2009).

Nearly 10 % of our analysed sequences contained candidate loci showing environmental associations (Table 2), a similar proportion to that found in previous studies (Ahrens et al. 2018). Using these putative adaptive loci we found six genetic clusters (AU), revealing different selective pressures across the specie’s distribution range (Figs 3B and 4B; seeSupporting Information—Fig. S3). Such a stark adaptive genetic structure was unexpected given the narrow environmental gradients found within Canga ecosystems [seeSupporting Information—Fig. S4], the small effective population sizes and the high gene flow between populations (Funk et al. 2012). Our results thus show that the climatic variability captured by bioclimatic layers was enough to detect non-random genotype–environment associations, but suggest that many more associations are likely to be detected when high-resolution climatic and soil data are made available. The small effective population sizes, on the other hand, may reflect the specie’s life history characteristics, and thus be sufficient to assure enough genetic variation for local adaptation to occur. Finally, local adaptation under high gene flow has been shown in other organisms (Godbout et al. 2019; Krohn et al. 2019), and suggest strong selective pressures associated with local environments are constantly shaping standing genetic variation (Allendorf et al. 2013).

Our environmental association tests can be considered conservative, because they accounted for false discovery rates (François et al. 2016) as well as the underlying demographic structure (Frichot and François 2015). We nevertheless note that other genes occurring in the flanking regions of our candidate SNPs could be responsible for the detected adaptive signals, and that many sequences did not match translated proteins, or found matches with uncharacterized proteins. Despite these methodological limitations, we found candidate genes coding proteins that play a variety of important roles related to plant metabolism, growth, development, stress tolerance, cellular transport and regulation of physiological functions [seeSupporting Information—Table S1]. Two proteins seem to be of especial importance, given they were associated with all environmental variables (Table 3): the serine-threonine/tyrosine-protein kinase catalytic domain regulates cellular and metabolic events (Parthibane et al. 2012), while the homeobox-associated leucine zipper is an important DNA-binding transcription factor regulating development and morphology in different plant organs (Chan et al. 1998; Jain et al. 2008). These proteins act at early and late developmental stages and have been associated with responses to different types of stresses, including water deficit, pathogens, salt concentration and cold temperatures (Chan et al. 1998; Zhang and Klessig 2001; Jain et al. 2008), as well as with other climatic responses (Ahrens et al. 2019; Ferrero-Serrano and Assmann 2019). In addition, five proteins (Table 3) were also found as putative adaptive in two morning glories from Carajás (Lanes et al. 2018), some of which are also involved in stress responses. We nevertheless note that functional validation of these candidate proteins is still necessary to confirm their role in local adaptations.

Conservation implications

Our results reveal that B. carajensis is structured in at least three neutral genetic clusters and six adaptive genetic clusters, which could be considered MU and AU, respectively. Since the recently created Campos Ferruginosos National Park (Fig. 2) is already protecting a portion of each of our identified MU (Fig. 3A), there seems to be no imminent risk of losing any of these MU. Admixture between MU and the lack of inbreeding suggest there is no short-term risk of inbreeding depression, although possible gene flow reductions caused by further habitat loss and fragmentation would make these units susceptible to genetic drift, considering their small effective population sizes (Jamieson and Allendorf 2012). On the other hand, not all AU are currently protected, and some are located in the vicinity of mining operations. Management options to prevent losing the adaptive genetic variation found in these AU include in situ or ex situ actions. In the later case, a sample of individuals from an AU could be either re-located or preserved through seed banks. Following the recommendations made by Frankham et al. (2017, page 216), genetic clusters should be managed separately when they show both neutral and adaptive differentiation (in our case AU from different MU), as risks of outbreeding depression are usually high. Under adaptive differentiation with no neutral differentiation (in our case AU within each MU), genetic rescue is only recommended when the risk of outbreeding depression is low. We believe this is the case in our study system, given that environmental differences are small and gene flow is high between (Fig. 3) and within each MU (Carvalho et al. 2019). Our results thus suggest that neutral genetic clusters (MU) should be managed separately, and that possible genetic rescue or re-location efforts should only employ individuals sampled within each of our identified MU.

Our study exemplifies how assumption-free genetic clustering methods and environmental association tests applied to a large genomic data set can be employed to delineate MU and AU, and thereby inform management decisions to prevent the loss of unique genetic variation and maximize species resilience to future environmental change. This approach is particularly useful to inform management decisions of rare and endangered species for which it is difficult or impossible to assess local adaptations using traditional common garden or reciprocal transplant experiments.

Supporting Information

The following additional information is available in the online version of this article—

Table S1. Functions of candidate proteins encoded by genes contained in the flanking regions of candidate SNPs.

Figure S1. Plots displaying ancestry coefficients retrieved from sparse non-negative matrix factorization (snmf) using neutral markers.

Figure S2. Manhattan plots of log-transformed adjusted P-values of candidate SNPs for each environmental variable, generated by latent factor mixed models (LFMM).

Figure S3. Triplot showing axes 1 and 2 of redundancy analysis (RDA) using the putative adaptive SNPs identified with latent factor mixed models (LFMM).

Figure S4. Variation in the three climatic variables used in environmental association tests (latent factor mixed models, LFMM) across the studied region.

Data

Genotypes, sequences and geographic coordinates for all samples are publicly available in FigShare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8224175.v3

Acknowledgements

We thank Frederico Drummond, Cesar Neto, Waléria Monteiro, Géssica E. A. Fernandes and André O. Simões for assistance in the field. Santelmo Vasconcelos and Manoel Lopes for help in the laboratory. Xavier Picó and two anonymous reviewers improved earlier versions of this manuscript.

Sources of Funding

Funding was provided by Instituto Tecnológico Vale, Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) grants 300652/2019-4 (A.R.S.), 300714/2017-3 (E.C.M.L.), 316067/2018-0 (L.C.R.-M.) and 301616/2017-5 (R.J.), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) grants 88887.156652/2017-00 (C.S.C.) and 88882.347930/2019-01 (M.P.O.-V.).

Contributions by the Authors

R.J. conceived, designed and coordinated the project. R.J. and P.L.V. coordinated the field work and sampling. A.R.S. and E.C.M.L. performed laboratory work. A.R.S., L.C.R.-M., E.C.M.L., C.S.C. and M.P.O.-V. performed data analysis. The first draft of the paper was written by A.R.S. with input from L.C.R.-M. and R.J. All authors contributed to discussing the results and editing the paper.

Conflict of Interest

Instituto Tecnológico Vale is a non-profit and independent research institute, and the choice of questions, study organisms and methodological approaches were exclusively defined by the authors, who declare no conflicting interests.

Literature Cited

- Ahrens CW, Byrne M, Rymer PD. 2019. Standing genomic variation within coding and regulatory regions contributes to the adaptive capacity to climate in a foundation tree species. Molecular Ecology 28:2502–2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CW, Rymer PD, Stow A, Bragg J, Dillon S, Umbers KDL, Dudaniec RY. 2018. The search for loci under selection: trends, biases and progress. Molecular Ecology 27:1342–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf FW, Luikart G, Aitken SN. 2013. Conservation and the genetics of population, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Almeda F, Michelangeli FA, Viana PL. 2016. Brasilianthus (Melastomataceae), a new monotypic genus endemic to ironstone outcrops in the Brazilian Amazon. Phytotaxa 273:269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Auffret AG, Berg J, Cousins SAO. 2014. The geography of human-mediated dispersal. Diversity and Distributions 20:1450–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa S, Mestre F, White TA, Paupério J, Alves PC, Searle JB. 2018. Integrative approaches to guide conservation decisions: using genomics to define conservation units and functional corridors. Molecular Ecology 27:3452–3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista PD, Janes JK, Boone CK, Murray BW, Sperling FA. 2016. Adaptive and neutral markers both show continent-wide population structure of mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Ecology and Evolution 6:6292–6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell JS, Zohren J, Nichols RA, Buggs RJA. 2019. Genomic assessment of local adaptation in dwarf birch to inform assisted gene flow. Evolutionary Applications doi: 10.1111/eva.12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock JM, Bonte D, Pufal G, da Silva Carvalho C, Chapman DS, García C, García D, Matthysen E, Delgado MM. 2018. Human-mediated dispersal and the rewiring of spatial networks. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 33:958–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell B. 2019. BBMap: short read aligner, and other bioinformatic tools. https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/ [Google Scholar]

- Candy JR, Campbell NR, Grinnell MH, Beacham TD, Larson WA, Narum SR. 2015. Population differentiation determined from putative neutral and divergent adaptive genetic markers in Eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus, Osmeridae), an anadromous Pacific smelt. Molecular Ecology Resources 15:1421–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CS, Lanes ÉCM, Silva AR, Caldeira CF, Carvalho-Filho N, Gastauer M, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Nascimento Júnior W, Oliveira G, Siqueira JO, Viana PL, Jaffé R. 2019. Habitat loss does not always entail negative genetic consequences. Frontiers in Genetics 10:1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilla AR, Pope NS, O’Connell M, Rodriguez MF, Treviño L, Santos A, Jha S. 2017. Adding landscape genetics and individual traits to the ecosystem function paradigm reveals the importance of species functional breadth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114:12761–12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti TB, Facco MG, Brauner L de M. 2016. Flora das cangas da Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brasil: lythraceae. Rodriguesia 67:1411–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Chan RL, Gago GM, Palena CM, Gonzalez DH. 1998. Homeoboxes in plant development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1442:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates DJ, Byrne M, Moritz C. 2018. Genetic diversity and conservation units: dealing with the species-population continuum in the age of genomics. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 6:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cole CT. 2003. Genetic variation in rare and common plants. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 34:213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST, McVean G, Durbin R; 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27:2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho WD, Mustin K. 2017. The highly threatened and little known Amazonian savannahs. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1:100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kort H, Vandepitte K, Bruun HH, Closset-Kopp D, Honnay O, Mergeay J. 2014. Landscape genomics and a common garden trial reveal adaptive differentiation to temperature across Europe in the tree species Alnus glutinosa. Molecular Ecology 23:4709–4721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR. 2014. NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources 14:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19:11–15 [Google Scholar]

- Dullinger S, Gattringer A, Thuiller W, Moser D, Zimmermann NE, Guisan A, Willner W, Plutzar C, Leitner M, Mang T, Caccianiga M, Dirnböck T, Ertl S, Fischer A, Lenoir J, Svenning JC, Psomas A, Schmatz DR, Silc U, Vittoz P, Hülber K. 2012. Extinction debt of high-mountain plants under twenty-first-century climate change. Nature Climate Change 2:619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert AJ, Bower AD, González-Martínez SC, Wegrzyn JL, Coop G, Neale DB. 2010. Back to nature: ecological genomics of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda, Pinaceae). Molecular Ecology 19:3789–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmands S. 2007. Between a rock and a hard place: evaluating the relative risks of inbreeding and outbreeding for conservation and management. Molecular Ecology 16:463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Serrano Á, Assmann SM. 2019. Phenotypic and genome-wide association with the local environment of Arabidopsis. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3:274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick SE, Hijmans RJ. 2017. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 37:4302–4315. [Google Scholar]

- François O, Martins H, Caye K, Schoville SD. 2016. Controlling false discoveries in genome scans for selection. Molecular Ecology 25:454–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankham R, Ballou JD, Ralls K, Eldridge M, Dudash MR, Fenster CB, Lacy RC, Sunnucks P. 2017. Genetic management of fragmented animal and plant populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frichot E, François O. 2015. LEA: an R package for landscape and ecological association studies. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 6:925–929. [Google Scholar]

- Frichot E, Mathieu F, Trouillon T, Bouchard G, François O. 2014. Fast and efficient estimation of individual ancestry coefficients. Genetics 196:973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk WC, Forester BR, Converse SJ, Darst C, Morey S. 2018. Improving conservation policy with genomics: a guide to integrating adaptive potential into U.S. Endangered Species Act decisions for conservation practitioners and geneticists. Conservation Genetics 20:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Funk WC, McKay JK, Hohenlohe PA, Allendorf FW. 2012. Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27:489–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JP, Rice SA, Stucke CM. 2008. Comparison of population genetic diversity between a rare, narrowly distributed species and a common, widespread species of Alnus (Betulaceae). American Journal of Botany 95:588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitzendanner MA, Soltis PS. 2000. Patterns of genetic variation in rare and widespread plant congeners. American Journal of Botany 87:783–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti AM, Giannini TC, Mota NFO, Watanabe MTC, Viana PL, Pastore M, Silva UCS, Siqueira MF, Pirani JR, Lima HC, Pereira JBS, Brito RM, Harley RM, Siqueira JO, Zappi DC. 2019. Edaphic endemism in the Amazon: vascular plants of the canga of Carajás, Brazil. The Botanical Review 85:357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout J, Gros-Louis MC, Lamothe M, Isabel N. 2019. Going with the flow: intraspecific variation may act as a natural ally to counterbalance the impacts of global change for the riparian species Populus deltoides. Evolutionary Applications doi: 10.1111/eva.12854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugger PF, Liang CT, Sork VL, Hodgskiss P, Wright JW. 2018. Applying landscape genomic tools to forest management and restoration of Hawaiian koa (Acacia koa) in a changing environment. Evolutionary Applications 11:231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick JL, Godt MJW, Murawski DA, Loveless MD. 1991. Correlations between species traits and allozyme diversity: implications for conservation biology. In: Falk DA, Holsinger KE, eds. Genetics and conservation of rare plants. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hartl DL, Clark AG. 2006. Principles of population genetics, 4th edn. New York: Sinauer Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Holderegger R, Kamm U, Gugerli F. 2006. Adaptive vs. neutral genetic diversity: implications for landscape genetics. Landscape Ecology 21:797–807. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé R, Veiga JC, Pope NS, Lanes ÉCM, Carvalho CS, Alves R, Andrade SCS, Arias MC, Bonatti V, Carvalho AT, de Castro MS, Contrera FAL, Francoy TM, Freitas BM, Giannini TC, Hrncir M, Martins CF, Oliveira G, Saraiva AM, Souza BA, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL. 2019. Landscape genomics to the rescue of a tropical bee threatened by habitat loss and climate change. Evolutionary Applications 12:1164–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. 2008. Genome-wide identification, classification, evolutionary expansion and expression analyses of homeobox genes in rice. The FEBS Journal 275:2845–2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson IG, Allendorf FW. 2012. How does the 50/500 rule apply to MVPs? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27:578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings H, Wallin K, Brennan J, Valle A Del, Guzman A, Hein D, Hunter S, Lewandowski A, Olson S, Parsons H, Scheidt S, Wang Z, Werra A, Kartzinel RY, Givnish TJ. 2016. Inbreeding, low genetic diversity, and spatial genetic structure in the endemic Hawaiian lobeliads Clermontia fauriei and Cyanea pilosa ssp. longipedunculata. Conservation Genetics 17:497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T. 2008. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24:1403–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T, Devillard S, Balloux F. 2010. Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genetics 11:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T, Devillard S, Dufour AB, Pontier D. 2008. Revealing cryptic spatial patterns in genetic variability by a new multivariate method. Heredity 101:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk H, Freeland JR. 2011. Applications and implications of neutral versus non-neutral markers in molecular ecology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 12:3966–3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn AR, Diepeveen ET, Bi K, Rosenblum EB. 2019. Local adaptation does not lead to genome-wide differentiation in lava flow lizards. Ecology and Evolution 9:6810–6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanes ÉC, Pope NS, Alves R, Carvalho-Filho NM, Giannini TC, Giulietti AM, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Monteiro W, Oliveira G, Silva AR, Siqueira JO, Souza-Filho PW, Vasconcelos S, Jaffé R. 2018. Landscape genomic conservation assessment of a narrow-endemic and a widespread morning glory from Amazonian Savannas. Frontiers in Plant Science 9:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimu R, Mutikainen P, Koricheva J, Fischer M. 2006. How general are positive relationships between plant population size, fitness and genetic variation? Journal of Ecology 94:942–952. [Google Scholar]

- Li YL, Xue DX, Zhang BD, Liu JX. 2019. Population genomic signatures of genetic structure and environmental selection in the catadromous roughskin sculpin Trachidermus fasciatus. Genome Biology and Evolution 11:1751–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manel S, Gugerli F, Thuiller W, Alvarez N, Legendre P, Holderegger R, Gielly L, Taberlet P; IntraBioDiv Consortium 2012. Broad-scale adaptive genetic variation in alpine plants is driven by temperature and precipitation. Molecular Ecology 21:3729–3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins K, Gugger PF, Llanderal-Mendoza J, González-Rodríguez A, Fitz-Gibbon ST, Zhao JL, Rodríguez-Correa H, Oyama K, Sork VL. 2018. Landscape genomics provides evidence of climate-associated genetic variation in Mexican populations of Quercus rugosa. Evolutionary Applications 11:1842–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JK, Christian CE, Harrison S, Rice KJ. 2005. ‘How local is local?’ - A review of practical and conceptual issues in the genetics of restoration. Restoration Ecology 13:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, John MC, Amasino RM. 1994. Removal of polysaccharides from plant DNA by ethanol precipitation. Biotechniques 17:274, 276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Blum M, Bork P, Bridge A, Brown SD, Chang HY, El-Gebali S, Fraser MI, Gough J, Haft DR, Huang H, Letunic I, Lopez R, Luciani A, Madeira F, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuka G, Orengo C, Pandurangan AP, Paysan-Lafosse T, Pesseat S, Potter SC, Qureshi MA, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson LJ, Rivoire C, Salazar GA, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist CJA, Sillitoe I, Sutton GG, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SCE, Yong SY, Finn RD. 2018. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Research 47:D351–D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitre SK, Mardegan SF, Caldeira CF, Ramos SJ, Furtini Neto AE, Siqueira JO, Gastauer M. 2018. Nutrient and water dynamics of Amazonian canga vegetation differ among physiognomies and from those of other neotropical ecosystems. Plant Ecology 219:1341–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JS, Bourret V, Dionne M, Bradbury I, O’Reilly P, Kent M, Chaput G, Bernatchez L. 2014. Conservation genomics of anadromous Atlantic salmon across its North American range: outlier loci identify the same patterns of population structure as neutral loci. Molecular Ecology 23:5680–5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz C. 1994. Defining ‘ evolutionarily significant units’ for conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 9:373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz C. 1999. Conservation units and translocations: strategies for conserving evolutionary processes. Hereditas 130:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mosca E, Eckert AJ, Di Pierro EA, Rocchini D, La Porta N, Belletti P, Neale DB. 2012. The geographical and environmental determinants of genetic diversity for four alpine conifers of the European Alps. Molecular Ecology 21:5530–5545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota NF de O, Silva LVC, Martins FD, Viana PL. 2015. Vegetação sobre sistemas ferruginosos da Serra dos Carajás. In: Carmo FF, Kamino LHY, eds. Geossistemas Ferruginosos do Brasil: áreas prioritárias para conservação da diversidade geológica e biológica, patrimônio cultural e serviços ambientais. Belo Horizonte: 3i Editora, 289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan R. 2006. Long-distance dispersal of plants. Science 313:786–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H. 2019. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 1.17-4. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan. [Google Scholar]

- Parthibane V, Iyappan R, Vijayakumar A, Venkateshwari V, Rajasekharan R. 2012. Serine/threonine/tyrosine protein kinase phosphorylates oleosin, a regulator of lipid metabolic functions. Plant Physiology 159:95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralls K, Ballou JD, Dudash MR, Eldridge MDB, Fenster CB, Lacy RC, Sunnucks P, Frankham R. 2018. Call for a paradigm shift in the genetic management of fragmented populations. Conservation Letters 11:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rellstab C, Gugerli F, Eckert AJ, Hancock AM, Holderegger R. 2015. A practical guide to environmental association analysis in landscape genomics. Molecular Ecology 24:4348–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner SSA. 1989. A survey of reproductive biology in neotropical Melastomataceae and Memecylaceae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 76:496–518 [Google Scholar]

- Resende-Moreira LC, Knowles LL, Thomaz AT, Prado JR, Souto AP, Lemos-Filho JP, Lovato MB. 2019. Evolving in isolation: genetic tests reject recent connections of Amazonian savannas with the central Cerrado. The Journal of Biogeography 46:196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha KC de J, Goldenberg R, Meirelles J, Viana PL. 2017. Flora das cangas da Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brasil: Melastomataceae. Rodriguésia 68:997–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Quilón I, Santos-Del-Blanco L, Serra-Varela MJ, Koskela J, González-Martínez SC, Alía R. 2016. Capturing neutral and adaptive genetic diversity for conservation in a highly structured tree species. Ecological Applications 26:2254–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russello MA, Waterhouse MD, Etter PD, Johnson EA. 2015. From promise to practice: pairing non-invasive sampling with genomics in conservation. PeerJ 3:e1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Schaffner SF, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Varilly P, Shamovsky O, Palma A, Mikkelsen TS, Altshuler D, Lander ES. 2006. Positive natural selection in the human lineage. Science 312:1614–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas RM, Viana PL, Cabral EL, Dessein S, Janssens S. 2015. Carajasia (Rubiaceae), a new and endangered genus from Carajás mountain range, Pará, Brazil. Phytotaxa 206:14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira FAO, Negreiros D, Barbosa NPU, Buisson E, Carmo FF, Carstensen DW, Conceição AA, Cornelissen TG, Echternacht L, Fernandes GW, Garcia QS, Guerra TJ, Jacobi CM, Lemos-filho JP, Stradic S, Morellato LPC, Neves FS, Oliveira RS, Schaefer CE, Viana PL, Lambers H. 2016. Ecology and evolution of plant diversity in the endangered campo rupestre: a neglected conservation priority. Plant and Soil 403:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Skirycz A, Castilho A, Chaparro C, Carvalho N, Tzotzos G, Siqueira JO. 2014. Canga biodiversity, a matter of mining. Frontiers in Plant Science 5:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soons MB, Heil GW, Nathan R, Katul GG. 2004. Determinants of long-distance seed dispersal by wind in grasslands. Ecology 85:3056–3068. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Filho PWM, Giannini TC, Jaffé R, Giulietti AM, Santos DC, Nascimento WR Jr, Guimarães JTF, Costa MF, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Siqueira JO. 2019. Mapping and quantification of ferruginous outcrop savannas in the Brazilian Amazon: a challenge for biodiversity conservation. PLoS One 14:e0211095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supple MA, Bragg JG, Broadhurst LM, Nicotra AB, Byrne M, Andrew RL, Widdup A, Aitken NC, Borevitz JO. 2018. Landscape genomic prediction for restoration of a Eucalyptus foundation species under climate change. Elife 7: e31835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123:585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyngaarden M, Snelgrove PV, DiBacco C, Hamilton LC, Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Jeffery NW, Stanley RR, Bradbury IR. 2017. Identifying patterns of dispersal, connectivity and selection in the sea scallop, Placopecten magellanicus, using RADseq-derived SNPs. Evolutionary Applications 10:102–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana PL, Mota NF de O, Gil A dos SB, Salino A, Zappi DC, Harley RM, Ilkiu-Borges AL, Secco R de S, Almeida TE, Watanabe MTC, Santos JUM dos, Trovó M, Maurity C, Giulietti AM. 2016. Flora of the cangas of the Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brazil: history, study area and methodology. Rodriguésia 67:1107–1124. [Google Scholar]

- von der Lippe M, Kowarik I. 2007. Long-distance dispersal of plants by vehicles as a driver of plant invasions. Conservation Biology 21:986–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann MC, Alexander MJ, Soons MB, Galsworthy S, Dunne L, Gould R, Fairfax C, Niggemann M, Hails RS, Bullock JM. 2009. Human-mediated dispersal of seeds over long distances. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276:523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Klessig DF. 2001. MAPK cascades in plant defense signaling. Trends in Plant Science 6:520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.