Abstract

Objective

The aim was to investigate the association between clinically significant uterine fibroids and preterm birth, caesarean section (CS), postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and uterine rupture.

Methods, participants and setting

A historical cohort study based on data from the Danish National Birth Cohort, the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Birth Registry (DNBR). The final study population consisted of 92 696 pregnancies and was divided into four groups for comparison. Group 1: pregnancies of women without a fibroid diagnosis code or fibroid operation code; group 2: pregnancies of women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy, during pregnancy or up to 1 year after delivery, and no fibroid operation code before pregnancy; group 3: pregnancies of women with a fibroid diagnosis code given more than 1 year after delivery; and group 4: pregnancies of women with a fibroid operation code given before pregnancy.

Results

A diagnosis of fibroids before pregnancy yielded an increased risk of preterm birth (gestational age (GA) ≤37 weeks) (OR 2.27 (1.30─3.96)) and extreme preterm birth (GA 22+0─27+6 weeks, OR 20.09 (8.04─50.22)). The risk of CS was increased (OR 1.83 (1.23─2.72)) for women with a fibroid diagnosis code given before pregnancy; significantly increased risk of elective CS (OR 1.92 (1.11─3.32)), but not acute CS (OR 1.54 (0.94─2.52)). The risks of PPH, placental abruption or IUGR were not increased in any of the groups.

Conclusion

We found a strong association between clinically significant uterine fibroids and preterm birth, and an association between clinically significant uterine fibroids and CS. In contrast, no association between clinically significant uterine fibroids and PPH, placental abruption or IUGR was seen.

Keywords: uterine fibroids, preterm birth, obstetrical complications

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores an area with inconsistent evidence.

This study is a large cohort study with data from 92 696 pregnancies.

Limitations include a low prevalence of uterine fibroids and a small number of events.

Introduction

As many as 10% of pregnant women may have uterine fibroids,1 and the incidence is likely to be even higher in populations with high maternal age and obesity.2 3 Fibroids may affect the uterine cavity, the placenta and the fetus directly, but may also cause the myometrium to be more inflexible and less responsive to oxytocin.4 5 Overall, fibroids are associated with obstetrical complication rates of 10%─40%,6 7 many of which have severe consequences. Due to the clinical impact on the mother and child, outcomes such as preterm birth, caesarean section (CS), postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and uterine rupture have been evaluated in relation to uterine fibroids.6–11 Some studies showed an association between fibroids and preterm birth, CS, PPH and placental abruption,8 9 12–14 whereas other studies showed no association with preterm birth, CS, PPH and IUGR.7 13 15

To address these discrepancies, we conducted a large historical cohort study of unselected pregnant women. We focused on women with clinically significant fibroids and compared women with a uterine fibroid diagnosis code to a reference group of women without a uterine fibroid diagnosis code. The aim was to investigate the association between clinically significant uterine fibroids and obstetrical outcomes with a specific focus on preterm birth, CS, PPH, placental abruption, IUGR and uterine rupture. Moreover, we analysed the association between myomectomy and the risk of uterine rupture.

Materials and methods

This historical cohort study is based on data from the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC), the Danish National Birth Registry (DNBR) and the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR).

Study population

The DNBC is a pregnancy cohort consisting of data from 92 840 women and 101 042 pregnancies. All registered pregnancies were included. Enrolment was performed in early pregnancy during the period between 1996 and 2002. Inclusion criteria were the intention to carry a pregnancy to term, residency in Denmark, and sufficient Danish proficiency to participate in telephone interviews. Data were collected by computer-assisted telephone interviews twice during pregnancy, and subsequently when the children were 6 and 18 months old. The DNBC data collection was approved by the Danish National Ethics Board. More details about this cohort have previously been described in detail.16

The DNPR holds diagnosis and operation codes from all inpatients since 1977 and outpatients since 1995. The codes are classified according to the International Classification of Diseases ICD10 since 1994. Diagnosis and operation codes regarding fibroids were collected for this study.

The DNBR contains information about live births and complications of all registered births in Denmark since 1973.

Selected relevant data from the DNPR and the DNBR were linked to data from the DNBC, using the unique personal identification number given to all residents in Denmark.

Data

We collected data on maternal age, height, weight, smoking habits, expected date of birth and fertility treatment (regardless of mode of assisted reproductive technique) from the DNBC. Maternal body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was calculated based on self-reported prepregnancy weight and height.

Fibroid diagnosis codes (DD25─DD259) and fibroid operation codes were collected from the DNPR. Operation codes were: myomectomy (KLCB10), laparoscopic myomectomy (KLCB11), hysteroscopic myomectomy (KLCB20), hysteroscopic resection of pathological tissue (KLCB22), hysteroscopic excision of pathological tissue (KLCB25) and hysteroscopic excision of other pathological tissue (KLCB98). We categorised operation codes into laparoscopic or open myomectomy (KLCB10, KLCB11) and hysteroscopic myomectomy (KLCB20, KLCB22, KLCB25 and KLCB98). Operation codes of the resection and excision of pathological tissue were pooled into one group of myomectomy since we assumed that many use these codes for hysteroscopic myomectomy.

GA, birth weight of the child and data on obstetrical outcomes (CS (KMCA10A, KMCA10D, KMCA10E and KMCA10B), placental abruption (DO450, DO451, DO452, DO453, DO458 and DO459)) and PPH (DO720, DO721, DO721A and DO721B) were collected from the DNBR.

Exposure definition

The study population was divided into four groups for comparison. Group 1: pregnancies of women without a fibroid diagnosis code or operation code; group 2: pregnancies of women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy, during pregnancy or up to 1 year after delivery, and no operation code before pregnancy; group 3: pregnancies of women with a fibroid diagnosis code given more than 1 year after delivery; and group 4: pregnancies of women with an operation code given before pregnancy.

Outcome definition

The outcomes were preterm birth, CS, placental abruption, PPH, IUGR and uterine rupture.

Preterm birth was defined as delivery at GA 22+0─36+6 weeks. We divided preterm birth into three categories according to the international classifications: moderate preterm: GA 34+0─36+6 weeks; very preterm: GA 28+0─33+6 weeks; and extreme preterm: GA 22+0─27+6 weeks. Due to the small number of events, we merged the groups into clinically relevant binary outcomes: moderate preterm: GA 34+0─36+6 weeks and very and extreme preterm GA 22+0─33+6 weeks.

CS was categorised as acute (KMCA10A, KMCA10D and KMCA10E) or elective (KMCA10B).

Placental abruption was reported under several diagnosis codes (DO450, DO451, DO452, DO453, DO458 and DO458) and pooled into one group.

PPH was defined as bleeding during delivery and up to 24 hours postpartum (DO720, DO721, DO721A and DO721B).

We followed the international classification of small of GA/IUGR as a birth weight below −22% of the expected weight at a given GA. This classification was originally developed by the 1995 WHO expert committee.17 We used a lower limit of −60% based on clinical reasoning; all births with an expected birth weight below −60% were excluded due to potential misclassification.

Data from the group of women who had a myomectomy before pregnancy was used to analyse the association between myomectomy and the risk of uterine rupture (DO710 and DO711).

Data purification

During the data purification, we made some assumptions. If a uterine fibroid diagnosis code was given once, the woman was categorised as having at least one uterine fibroid during the study period, unless she had a fibroid operation code. A fibroid diagnosis code given more than 90 days after a fibroid operation code was interpreted as a new uterine fibroid. We assumed the fibroid to be present also before pregnancy, if a fibroid diagnosis code was given during pregnancy or up to 1-year postpartum, and data were included in the fibroid group.

Missing values were identified and analysed. We had an 87% complete dataset. Missing values were imputed by multiple imputations of multiple variables assuming that values were missing at random. Analyses were made before and after imputation.

We identified the potential confounders for each outcome based on the directed acyclic graph (DAG).18 For preterm birth, CS and PPH, we identified maternal age and BMI to be possible confounders. For placental abruption, we identified maternal age to be a possible confounder. For IUGR and uterine rupture, we did not identify any possible confounders.

We found that 317 women had a myomectomy before pregnancy (205 by hysteroscopy and 112 by laparoscopy).

Statistical analyses

A one-way ANOVA was used for comparison of normally distributed data such as age. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed data such as BMI and parity. Smoking habits and fertility treatment were compared using the χ2 test.

We used logistic regression analysis to compare the binary outcomes; preterm birth, CS, PPH, placental abruption, IUGR and uterine rupture. We adjusted for potential confounders identified by DAGs in all analyses (maternal age and BMI). By using robust standard errors, we accounted for some women being included with more than one pregnancy in the analyses.

We found the tests acceptable based on the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Subgroup analyses of women with a fibroid operation code before pregnancy were performed.

We performed stratified analyses for preterm birth regarding fertility treatment and multiple pregnancies.

All analyses were performed in STATA V.15.

Patient and public involvement statement

Participants in the DNBC are involved in all research based on data from the DNBC. A member of the DNBC ambassadors, which is a group of selected participants representing all participants, is represented in the DNBC reference group. There was no other patient or public involvement in this study.

Results

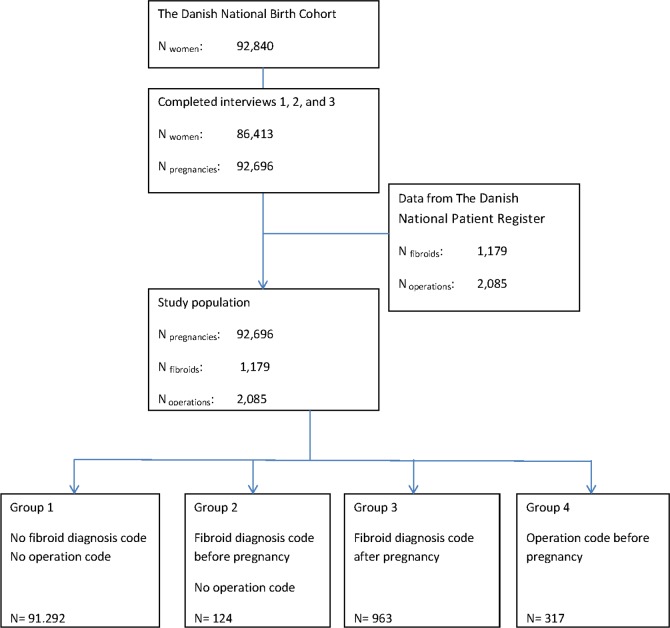

Our final study population consisted of 86 323 women and 92 696 pregnancies, divided into the four exposure groups (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population.

Population characteristics for the four exposure groups are shown in table 1. The groups did not differ regarding BMI, but they differed regarding age, smoking habits, parity, multiple pregnancies and proportion of fertility treatment.

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| No fibroids group 1 (reference group) |

Fibroids before pregnancy no operation group 2 |

Fibroids after pregnancy group 3 |

Fibroid operation before pregnancy group 4 |

|

| Population, N | 91 292 | 124 | 963 | 317 |

| Age, years Mean (SD) |

30 (4.29) | 34 (4.15) | 32 (3.96) | 34 (4.16) |

| BMI, kg/m2

median (range) |

23 (10–64) | 23 (16–40) | 23 (16–49) | 22 (18–35) |

| Parity median (range) | 1 (0–14) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–3) |

| Smoking, % | 16.43 | 11.82 | 16.04 | 13.15 |

| Fertility treatment, % | 6.32 | 18.48 | 9.76 | 39.39 |

| Multiple pregnancy, % | 2.14 | 4.03 | 3.95 | 7.89 |

Preterm birth

The risk of overall preterm birth was increased among the group of women who had a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy (group 2) compared with women without a fibroid diagnosis code (group 1), OR 2.3 (1.30─3.96). The risk of moderately preterm birth was not increased, OR 0.6 (0.20─1.96), whereas the risk of very preterm, extreme preterm and the pooled group of very and extreme preterm birth, was significantly increased, OR 4.00 (1.75─9.13), OR 20.1 (8.04─50.22) and OR 6.5 (3.51─12.19), respectively. For the group of women with a fibroid diagnosis code after pregnancy (group 3), the risk of preterm birth was not increased. The group of women who had an operation before pregnancy (group 4) had an increased risk of overall preterm birth of OR 1.8 (1.24─2.65) and very preterm birth OR 2.8 (1.55─5.22). None delivered extremely preterm (table 2).

Table 2.

Results

| No fibroids group 1 (reference group) |

Fibroids before pregnancy no operation group 2 |

Fibroids after pregnancy group 3 |

Fibroid operation before pregnancy group 4 |

||||

| (n=91 292) | (n=124) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | (n=963) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | (n=317) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Preterm birth* (week) | |||||||

| ≤37 | 4939 (5.4%) | 14 (11.3%) | 2.27 (1.30─3.96) | 55 (5.7%) | 1.08 (0.82─1.42) | 29 (9.1%) | 1.81 (1.24─2.65) |

| ≥34 < 37 | 3506 (3.9%) | 3 (2.4%) | 0.62 (0.20─1.96) | 41 (4.3%) | 1.11 (0.81─1.53) | 18 (5.7%) | 1.52 (0.94─2.43) |

| ≥28 < 34 | 1159 (1.2%) | 6 (4.8%) | 3.99 (1.75─9.13) | 11 (1.4%) | 0.90 (0.50─1.64) | 11 (5.5%) | 2.84 (1.55─5.22) |

| ≥22 < 28 | 176 (0.2%) | 5 (4.0%) | 20.09 (8.04─50.22) | 3 (0.3%) | 1.56 (0.50 ─ 4.89) | 0 (0%) | Empty |

| ≥22 < 34 | 1335 (1.5%) | 11 (8.9%) | 6.54 (3.51─12.19) | 14 (1.5%) | 0.99 (0.58─1.69) | 11 (3.5%) | 2.44 (1.33─4.48) |

| Caesarean section* | |||||||

| Overall | 14 542 (16%) | 36 (29%) | 1.83 (1.23─2.72) | 164 (17%) | 0.99 (0.84─1.19) | 110 (35%) | 2.48 (1.94─3.16) |

| Acute | 9901 (11%) | 21 (17%) | 1.54 (0.94─2.52) | 116 (12%) | 1.08 (0.88─1.32) | 62 (20%) | 1.91 (1.44─2.52) |

| Planned | 4641 (5%) | 15 (12%) | 1.92 (1.11─3.32) | 48 (5%) | 0.85 (0.64─1.14) | 48 (15%) | 2.58 (1.85─3.60) |

| IUGR* | 3731 (4.1%) | 6 (4.8%) | 1.27 (0.57─2.85) | 35 (3.6%) | 0.91 (0.65─1.28) | 13 (4.1%) | 1.05 (0.60─1.83) |

| PPH* | 3364 (3.7%) | 7 (5.7%) | 1.70 (0.70─3.65) | 36 (3.7%) | 1.06 (0.76─1.47) | 15 (4.7%) | 1.40 (0.84─2.35) |

| Abruption placentae† | 490 (0.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1.41 (0.20─10.15) | 6 (0.6%) | 1.13 (0.50─2.53) | 3 (0.9%) | 1.66 (0.53─5.21) |

| Uterus rupture | 7 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | Empty | 2 (0.2%) | 2.84 (0.39─20.56) | 0 (0%) | Empty |

*Adjusted for age and body mass index.

†Adjusted for age.

We stratified accordingly to fertility treatment and found an increased risk of extremely preterm birth (OR 25.6 (7.95─82.43)) among women treated for infertility and among spontaneously pregnant women (OR 8.4 (1.08─15.76)). The same was applicable for the pooled group of very and extreme preterm birth where increased risk was found for women with fertility treatment OR 5.6 (2.24─13.85) and spontaneous pregnancy OR 4.5 (1.28─15.76). In women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy, the risk of preterm birth was not increased in any other groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Results, stratified analyses and adjusted OR

| Fibroids before pregnancy no operation group 2 odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | Fibroids after pregnancy group 3 odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | Operation before pregnancy group 4 odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| No fertility treatment n=75/81 836 |

Fertility treatment n=17/5522 |

No fertility treatment n=869/81 836 |

Fertility treatment n=94/5522 |

No fertility treatment n=140/81 836 |

Fertility treatment n=91/5522 |

|

| Preterm birth (week) | ||||||

| ≤37 | 1.74 (0.75─4.02) | 1.37 (0.39─4.76) | 1.04 (0.77─1.41) | 0.93 (0.51─1.72) | 1.05 (0.49─2.25) | 1.06 (0.59─1.92) |

| ≥34 to <37 | 0.37 (0.05─2.69) | Empty | 1.02 (0.71─1.47) | 1.20 (0.62─2.33) | 1.24 (0.55─2.80) | 0.97 (0.47─2.02) |

| ≥28 to <34 | 2.45 (0.60─10.02) | 3.37 (0.77─14.85) | 0.94 (0.48─1.81) | 0.55 (0.13─2.25) | 0.64 (0.09─4.61) | 1.47 (0.59─3.60) |

| ≥22 to <28 | 25.60 (7.95─82.43) | 8.36 (1.08─64.50) | 2.13 (0.68─6.69) | Empty | Empty | Empty |

| ≥22 to <34 | 5.57 (2.24─13.85) | 4.5 (1.28─15.76) | 1.09 (0.62─1.93) | 0.46 (0.17─1.87) | 1.09 (0.6─1.93) | 1.22 (0.49─3.04) |

| Singleton pregnancy n=119/89 338 |

Multiple pregnancies n=5/1964 |

Singleton pregnancy n=925/89 338 |

Multiple pregnancies n=38/1964 |

Singleton pregnancy n=292/89 338 |

Multiple pregnancies n=25/1964 |

|

| Preterm birth (week) | ||||||

| ≤37 | 1.90 (0.32─11.45) | 2.18 (1.17─4.05) | 0.66 (0.34─1.30) | 1.02 (0.75─1.39) | 1.17 (0.53─2.59) | 1.33 (0.81─2.16) |

| ≥34 to <37 | 0.76 (0.24─2.40) | Empty | 0.99 (0.68─1.42) | 0.99 (0.49─2.03) | 1.26 (0.68─1.42) | 0.77 (0.31─1.95) |

| ≥28 to <34 | 3.41 (1.25─9.28) | 4.40 (0.73─26.48) | 0.96 (0.50─1.86) | 0.37 (0.09─1.53) | 1.71 (0.70─4.15) | 2.09 (0.82─5.27) |

| ≥22 to <28 | 22.32 (8.18─60.92) | 12.95 (1.41─118.77) | 2.08 (0.66─6.56) | Empty | Empty | Empty |

| ≥22 to <34 | 6.11 (2.99─12.51) | 8.4 (1.41─50.93) | 1.11 (0.63─1.98) | 0.31 (0.75─1.31) | 1.48 (0.61─3.59) | 1.78 (0.71─4.50) |

We also stratified according to singleton pregnancies. Among singleton pregnant women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy, we found an increased risk of very preterm of OR 3.4 (1.25─9.28); extreme preterm of OR 22.3 (8.18─60.92); and the pooled group of very and extreme preterm birth of OR 6.1 (2.99─12.51). Apart from that, the risk of preterm birth was not increased in any other groups (table 3). For multiple pregnancy women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy, we found an increased risk of overall preterm of OR 2.2 (1.17─4.05), very preterm of OR 4.4 (0.73─26.48), extreme preterm of OR 13.0 (1.41─118.77) and pooled very and extreme preterm birth of OR 8.5 (1.41─50.93). Apart from that, the risk of preterm birth was not increased in any other groups (table 3). The risk of preterm birth was increased regardless of stratification according to fertility treatment (with and without) and type of pregnancy (singleton or multiple) (data not shown).

Caesarean section

The overall risk of CS was increased in women with a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy (group 2), OR 2.2 (1.50─3.21). The same applied after adjusting for age and BMI of OR 1.8 (1.23─2.72). The risk of acute CS was not increased in the adjusted analyses, OR 1.5 (0.94─2.52). The risk of elective CS was increased, OR 2.6 (1.50─4.41), and the same applied after adjusting for age and BMI, OR 1.9 (1.11─3.32). For the group of women with an operation code before pregnancy (group 4), the risk of CS was also increased; OR 2.6 (1.85─3.60) for elective CS and OR 1.9 (1.44─2.52) for acute CS. The risk of CS was not increased in women with a fibroid diagnosis code after pregnancy (group 3) (table 2).

PPH, placental abruption and IUGR

The risk of PPH, placental abruption and IUGR was not increased in women with a fibroid diagnosis code; PPH OR 1.7 (0.70─3.65); placental abruption OR 1.4 (0.20─10.15); and IUGR OR 1.3 (0.57─2.85) (table 2).

Uterine rupture

We found no uterine ruptures in the group with an operation code before pregnancy (n=317, 112 laparoscopic myomectomies and 205 hysteroscopic myomectomies). Uterine rupture was diagnosed in 67 of the 91 292 (0.1%) women without a fibroid diagnosis code. Two women out of the 963 with a fibroid diagnosis code after pregnancy (0.21%) were diagnosed with uterine rupture, and no women out of 124 (0%) had uterine rupture and a fibroid diagnosis code before pregnancy.

Discussion

Women with a uterine fibroid diagnosis code had a significantly higher risk of preterm birth in general, extreme preterm birth in particular. The fact that the association persisted through all the analyses, irrespective of the mode of conception, number of fetuses, age and BMI enhances the robustness and significance of our results.

Previous studies that differed in design in terms of exposure and outcome found weaker associations. A previous systematic review from 2008 reported a cumulative preterm birth rate (before GA 37 weeks) of 16% among women with fibroids corresponding to an OR of 1.5 (1.3─1.7). None of the included studies, however, adjusted for potential confounders such as age and BMI.8 A recent case series from 2018 reported a preterm birth rate of 28% in women with uterine fibroids. This study did not include a reference group without fibroids, and a calculation of the estimated risk was not possible.19 All previous studies used different classifications of preterm birth, which further complicates comparison. Three historical cohort studies all showed an increased risk of preterm birth (GA <37 weeks), but they used different categorisation regarding GA. Arisoy et al reported an OR 4.7 (1.9─11.6) for preterm birth <37, OR 4.3 (2.0─13.9) for preterm birth <34 weeks, decreasing to OR 3.3 (0.8─13.4) for preterm birth <32 weeks.20 Blitz et al also categorised preterm birth into groups depending on GA and found OR 1.61 (1.16─2.23) for preterm birth 34─36 weeks, OR 2.99 (1.65─5.40) for preterm birth 32─33 weeks, OR 1.47 (0.59─3.67) for 28─31 weeks and OR 1.81 (1.49─2.19) for 20─27 weeks.21 In contrast, Lai et al found an increased risk of preterm birth with decreasing GA; OR 1.70 (1.12─2.58) for 24─34 weeks, OR 1.99 (1.05─3.75) for 24─28 weeks and OR 2.48 (1.38─4.44) for 20─27 weeks.22 All three cohort studies included women who had undergone routine second-trimester obstetrical ultrasound, which was the basis for inclusion into the exposure or control group. Women in our cohort study were included based on a fibroid diagnosis code and we assume that many clinical insignificant fibroids with no symptoms were never diagnosed. Therefore, women in our cohort are likely to be different from women with fibroids diagnosed by routine ultrasound in pregnancy.

In line with previous studies, women with a fibroid diagnosis code had an increased risk of elective CS. A review from 2016 based on 13 studies reported a cumulative CS frequency of 49% corresponding to an unadjusted OR of 3.7 (3.5─3.9).23 These findings are in line with the clinical guidelines of elective CS if the uterine fibroids are evaluated to infer a risk of mechanical obstruction or malpresentation. Further, we found that women with a fibroid diagnosis code intended for vaginal delivery had the same risk of acute CS as women without a fibroid diagnosis code.

With regard to the risk of PPH, placental abruption or IUGR, we found no differences between groups. In contrast, a review from 2016, based on historical cohort studies, and a systematic review from 2008, suggested an increased risk of all three outcomes.23 However, other studies, which for different reasons were not included in the systematic review, are consistent with our findings.9 13 20 22 24

We found no uterine ruptures following laparoscopic myomectomy (n=112). The risk of uterine rupture following laparoscopic myomectomy has been compared with the risk following uterine surgery such as CS,23 25 26 and some authors have reported an increased risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy.27 Based on clinical reasoning it is believed that surgical skills and techniques such as the use of bipolar diathermy, and timespan from operation to pregnancy are essential factors for the risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy. Our study did not allow the analysis for these factors. In Denmark, complex laparoscopic myomectomy is preferentially performed by experienced surgeons and 6 months from operation to pregnancy is recommended. Both factors are likely to have contributed to the low rate of uterine rupture found in our study.

In a review from 2016, it was suggested that fibroid treatment minimises the risk of adverse negative obstetrical outcomes. However, they also concluded that more clinical studies are needed to draw firm conclusions as findings are still inconsistent.28 In the present study, the risk of preterm birth decreased whereas the risk of CS increased after myomectomy compared with the risks among women with untreated uterine fibroids. Our results contribute to the overall discussion about treatment prior to pregnancy, however, more studies are required. A randomised controlled trial, which would be optimal for firm conclusions, is not possible due to ethical considerations. At best, a large cohort study with detailed exposure and outcome information can give further information.

Limitations

Our results are based on retrospective data, and the number of events was small despite the large size of the cohort. We found a low prevalence of uterine fibroid diagnosis codes in our study population compared with previous reports.29 It might indicate that women participating in DNBC consisted of a selected group of women.30 Our results cannot be used as an indicator of prevalence or incidence in the general population, but it is important to notice, that data are fully valid for analyses of associations.31

Our exposure registration was based on clinical diagnosis coding, which may be incorrect or lacking due to various work-related distractions and a variable individual interpretation of clinical cases, leading to exposure misclassification. The low prevalence of uterine fibroids in our study population is likely to be a result of underreporting. A potential bias will lead towards exposed women being categorised as unexposed, and hence attenuation of the association between exposure (uterine fibroids) and outcomes.32 Since the potential underreporting is independent of the outcome due to the prospective nature of data collection in a cohort study, a potential misclassification could lead to non-differential information bias.

Further, we found that some women had an operation code, but no diagnosis code, substantiating the hypothesis of risk of exposure misclassification. In Denmark, operation codes are more closely connected to hospital budgets than clinical diagnosis codes. A detailed validation of data would most likely have solved discrepancies, but we did not have the possibility to validate the data from the DNPR, and we relied on previous studies, showing that reproductive gynaecological coding in the DNPR is generally valid and suitable for clinical quality control.33

Risk of misclassification related to the operation codes could have been cleared by postoperative histological diagnoses. As these data were not available, we minimised the risk by ensuring that none of the women in our exposure group had a diagnoses code for other uterine pathologies such as adenomyosis or polyps.

The DNBC mainly consists of white women with middle or high social status30 and since uterine fibroids have different pathophysiology for example Afro-American and Caucasian woman,34 our results can only reasonably be applied to the Scandinavian population.

A short cervix in early pregnancy has been associated with uterine fibroids and may represent part of the mechanism behind the risk of preterm birth among women with uterine fibroids.7 21 Unfortunately, we did not have the opportunity to investigate the contribution of cervical length on preterm birth due to the lack of a specific diagnosis code.

Conclusions

The present study, including 92 696 pregnancies, found a strong association between a uterine fibroid diagnosis and the risk of preterm birth in general and extreme preterm birth in particular. We suggest that future clinical studies focus on the relationship between obstetrical outcomes and fibroids in terms of anatomical location, growth throughout pregnancy and cervical length.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KK contributed to project development, data management, data analysis and manuscript writing/editing. USK performed project development, data analysis and manuscript writing. OM performed project development, data analysis and manuscript writing. PH did project development, data analysis and manuscript writing. PR contributed to project development, data analysis and manuscript writing.

Funding: The corresponding author has been financially supported by the University of Southern Denmark, the Region of Southern Denmark, and the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Odense University Hospital, Denmark.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Danish Data Protecting Agency (registration number; 2012-58-0018). According to Danish law, ethical approval is not required for registry-based studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Laughlin SK, Baird DD, Savitz DA, et al. Prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in the first trimester of pregnancy: an ultrasound-screening study. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:630–5. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318197bbaf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denmarks Statistics , 2018. Available: https://www.dst.dk

- 3. Matthiessen J, Stockmarr A. Flere overvægtige danske kvinder NR. 2. E-artikel fra DTU Fødevareinstituttet, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blum M. Comparative study of serum cap activity during pregnancy in malformed and normal uterus. J Perinat Med 1978;6:165–8. 10.1515/jpme.1978.6.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rice JP, Kay HH, Mahony BS. The clinical significance of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:1212–6. 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90194-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coronado GD, Marshall LM, Schwartz SM. Complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery with uterine leiomyomas: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:764–9. 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00605-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shavell VI, Thakur M, Sawant A, et al. Adverse obstetric outcomes associated with sonographically identified large uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 2012;97:107–10. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klatsky PC, Tran ND, Caughey AB, et al. Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:357–66. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nyfløt LT, Sandven I, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:17 10.1186/s12884-016-1217-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ouyang DW, Economy KE, Norwitz ER. Obstetric complications of fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2006;33:153–69. 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olive DL, Pritts EA. Fibroids and reproduction. Semin Reprod Med 2010;28:218–27. 10.1055/s-0030-1251478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cook H, Ezzati M, Segars JH, et al. The impact of uterine leiomyomas on reproductive outcomes. Minerva Ginecol 2010;62:225–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin J, Ulrich ND, Duplantis S, et al. Obstetrical outcomes of ultrasound identified uterine fibroids in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2016;33:1218–22. 10.1055/s-0036-1593389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lam S-J, Best S, Kumar S. The impact of fibroid characteristics on pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:395.e1–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril 2009;91:1215–23. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, et al. The Danish National Birth Cohort--its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health 2001;29:300–7. 10.1177/14034948010290040201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Onis M, Habicht JP. Anthropometric reference data for international use: recommendations from a world Health organization expert Committee. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;64:650–8. 10.1093/ajcn/64.4.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011;22:745 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225c2be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saleh HS, Mowafy HE, Hameid AAAE, et al. Does uterine fibroid adversely affect obstetric outcome of pregnancy? Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:1–5. 10.1155/2018/8367068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arisoy R, Erdogdu E, Bostancι E, et al. Obstetric outcomes of intramural leiomyomas in pregnancy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2016;43:844–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blitz MJ, Rochelson B, Augustine S, et al. Uterine fibroids at routine second-trimester ultrasound survey and risk of sonographic short cervix. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:1–7. 10.3109/14767058.2015.1131261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lai J, Caughey AB, Qidwai GI, et al. Neonatal outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:710–3. 10.3109/14767058.2011.572205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ezzedine D, Norwitz ER. Are women with uterine fibroids at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcome? Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016;59:119–27. 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ciavattini A, Clemente N, Delli Carpini G, et al. Number and size of uterine fibroids and obstetric outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015;28:484–8. 10.3109/14767058.2014.921675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pistofidis G, Makrakis E, Balinakos P, et al. Report of 7 uterine rupture cases after laparoscopic myomectomy: update of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2012;19:762–7. 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, et al. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2017;43:1789–804. 10.1111/jog.13437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim MS, Uhm YK, Kim JY, et al. Obstetric outcomes after uterine myomectomy: laparoscopic versus laparotomic approach. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2013;56:375–81. 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.6.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parazzini F, Tozzi L, Bianchi S. Pregnancy outcome and uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;34:74–84. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:100–7. 10.1067/mob.2003.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacobsen TN, Nohr EA, Frydenberg M. Selection by socioeconomic factors into the Danish national birth cohort. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:349–55. 10.1007/s10654-010-9448-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, et al. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology 2006;17:413–8. 10.1097/01.ede.0000220549.14177.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kesmodel US. Information bias in epidemiological studies with a special focus on obstetrics and gynecology. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:417–23. 10.1111/aogs.13330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lidegaard O, Vestergaard CH, Hammerum MS. [Quality monitoring based on data from the Danish National Patient Registry]. Ugeskr Laeger 2009;171:412–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Negri E, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of women with uterine fibroids: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol 1988;72:853–7. 10.1097/00006250-198812000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.