Abstract

Objectives and design

Guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) with renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers has improved survival in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). As clinical trials usually do not include very old patients, it is unknown whether the results from clinical trials are applicable to elderly patients with HF. This study was performed to investigate the clinical characteristics and treatment strategies for elderly patients with HFrEF in a large prospective cohort.

Setting

The Korean Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) registry consecutively enrolled 5625 patients hospitalised for acute HF from 10 tertiary university hospitals in Korea.

Participants

In this study, 2045 patients with HFrEF who were aged 65 years or older were included from the KorAHF registry.

Primary outcome measurement

All-cause mortality data were obtained from medical records, national insurance data or national death records.

Results

Both beta-blockers and RAS inhibitors were used in 892 (43.8%) patients (GDMT group), beta-blockers only in 228 (11.1%) patients, RAS inhibitors only in 642 (31.5%) patients and neither beta-blockers nor RAS inhibitors in 283 (13.6%) patients (no GDMT group). With increasing age, the GDMT rate decreased, which was mainly attributed to the decreased prescription of beta-blockers. In multivariate analysis, GDMT was associated with a 53% reduced risk of all-cause mortality (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.57) compared with no GDMT. Use of beta-blockers only (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.73) and RAS inhibitors only (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.71) was also associated with reduced risk. In a subgroup of very elderly patients (aged ≥80 years), the GDMT group had the lowest mortality.

Conclusions

GDMT was associated with reduced 3-year all-cause mortality in elderly and very elderly HFrEF patients.

Trial registration number

Keywords: heart failure, adult cardiology, cardiac epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a large prospective cohort study that included patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who were aged 65 years or older.

We obtained all participants’ mortality data from medical or national death records.

The registry could not capture all comorbidities including functional or cognitive impairments, which is an important prognostic factor for elderly patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is associated with significant morbidity, mortality and healthcare burdens.1 Since the prevalence of HF increases with age, the incidence of elderly patients with HF has been continuously increasing as the ageing population increases.2–4 Elderly patients with HF have worsened outcomes: they have more comorbidities, functional and cognitive impairments and polypharmacy.5–7 In addition, they are at high risk of rehospitalisation for HF after hospital discharge.8

Large clinical trials have shown that guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) with renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers improved survival in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).9–11 However, many elderly patients with HF have been excluded from randomised clinical studies due to age, comorbidities or functional or cognitive impairments, among others.12 Accordingly, it is unknown whether the results from clinical trials can be directly applied to elderly patients with HF.

Korea is one of the most rapidly ageing societies. In 2018, it has become an ‘aged society’ and will be a ‘super-aged society’ by 2026.13 In 2017, Korea’s proportion of individuals aged ≥65 years was 13.8%. Considering that 70% of hospitalisations for HF occurred in patients aged ≥65 years, a better understating of these high-risk patients is critical for proper management.14 In this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics and treatment strategies for elderly patients with HFrEF in a large prospective cohort.

Methods

Participants and cohort recruitment

The Korean Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) registry is a prospective multicentre registry designed to reflect the real-world clinical data of Korean patients admitted for acute HF. The study design and primary results of the registry have been published elsewhere.15 16 Patients hospitalised for acute HF from 10 tertiary university hospitals in Korea were consecutively enrolled from March 2011 to February 2014. Briefly, patients with signs or symptoms of HF and either lung congestion or objective findings of left ventricle systolic dysfunction or structural heart disease were eligible for enrolment in this registry. To minimise selection bias, we tried to enrol all hospitalised patients with acute HF at each hospital. Patients’ baseline characteristics, clinical presentation, underlying diseases, vital signs, laboratory tests, treatments and outcomes were recorded at admission, and discharge, and during follow-up (30 days, 90 days, 180 days and 1–3 years annually). The mortality data for patients who were lost to follow-up were obtained from the national insurance data or national death records.

In this study, we included patients with HFrEF who were aged 65 years or older. For patient selection, we serially excluded patients if any of the exclusion criteria was met. Written informed consent was waived by the institutional review board. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the conception, design or interpretation of this study. The results of this study will be disseminated to patients and healthcare providers through oral presentations and social media.

Study variables and definition

HFrEF was defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≤40%. The patients were classified into groups according to the medication prescribed at discharge: the GDMT group (patients who received both beta-blockers and RAS inhibitors), beta-blockers only group, RAS inhibitors only group and no GDMT group (no beta-blockers or RAS inhibitors). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as a glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was defined as a self-reported or physician-confirmed diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, emphysema or both. The primary outcome was 3-year postdischarge all-cause mortality from index admission.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as a mean±SD, whereas categorical variables were presented as counts and their percentages. Differences among continuous variables were analysed using a one-way analysis of variance and those among categorical variables using the χ2 test. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of GDMT prescription. We converted the ORs from logistic regression analysis into risk ratios because of the high prevalence of GDMT.17 The cumulative event rate was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank analysis. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was used to evaluate the adjusted relative risk of the variables. Multivariable models including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, previous HF history, atrial fibrillation, CKD, cause of HF, COPD, treatment strategy (no GDMT, beta-blockers only, RAS inhibitors only and GDMT) and prescription of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), digitalis and diuretics were chosen according to their clinical relevance and based on the results of previous trials.3 11 Furthermore, we performed a prespecified subgroup analysis including age, CKD, COPD, HF aetiology and HF onset and produced forest plots of the HR of medical therapy (ie, GDMT, beta-blockers only and RAS inhibitors only) compared with no GDMT. We evaluated whether there was an interaction between treatment strategy and the subgroups on all-cause mortality. For the calculation of P for interaction, Cox regression models were used that included the indicator variables for treatment strategy, subgrouping variables and interaction term of the treatment strategy-by-subgrouping variable of interest (age, CKD, COPD, HF aetiology or HF onset), as independent variables. The following covariates were also included in the interaction models: sex, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation and prescription of MRA, digitalis and diuretics. To mitigate the impact of potential confounding factors in the registry data, we additionally performed the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). The inferences regarding the rate of all-cause death were conducted with robust SEs after examining covariate balances among treatment groups. We used the ‘Twang’ package for R programming for IPTW analysis. Success of IPTW analyses was assessed by calculating the standardised differences in baseline characteristics. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.24.0 for Windows and R V.3.1.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

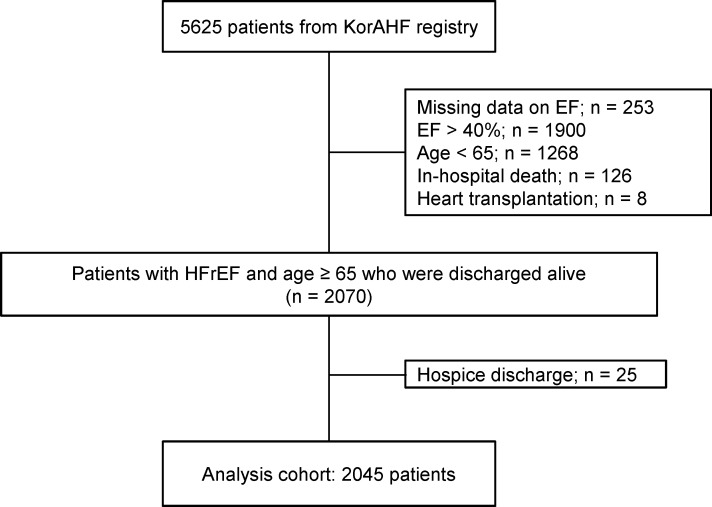

The KorAHF registry includes 5625 patients with acute HF. Of these, we excluded patients with missing LVEF (n=253), those with LVEF >40% (n=1900),<65 years in age (n=1268), in-hospital death (n=126), heart transplantation (n=8) and those who were hopelessly discharged (n=25), leaving a total of 2045 patients available for the final analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow. EF, ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; KorAHF, Korean Acute Heart Failure.

Overall, the mean age was 75.9 years, 54.2% were men, 66.7% had hypertension and 42.0% had diabetes mellitus. In addition, the mean LVEF was 28.7%±7.4%, and the most common cause of HFrEF was ischaemic cardiomyopathy (50.5%).

Medication prescription pattern according to patients’ characteristics

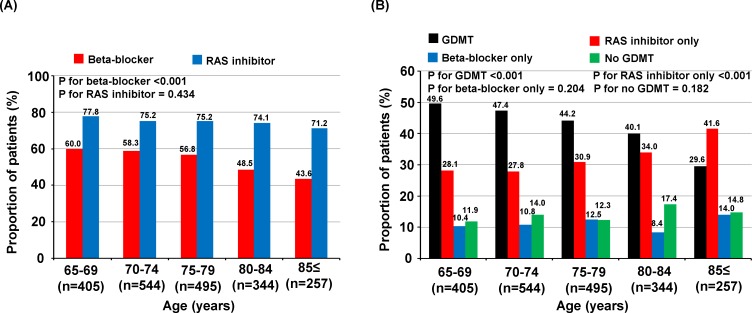

The beta-blocker prescription rate at discharge was 54.8% in all patients and that of RAS inhibitors was 75.0%. With increasing age, the beta-blocker prescription rate decreased (p for trend <0.001), while that of RAS inhibitors remained unchanged (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Discharge medication profiles. Prescription of beta-blockers, RAS inhibitors (A) and GDMT (B) in elderly patients with HFrEF according to age group. GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; RAS, renin-angiotensin system.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarised in table 1. Overall, both beta-blockers and RAS inhibitors were used in 892 (43.8%) patients (GDMT group), beta-blockers only in 228 (11.1%) patients, RAS inhibitors only in 642 (31.5%) patients and neither beta-blockers nor RAS inhibitors in 283 (13.6%) patients (no GDMT group). The beta-blocker prescription rate was lower in patients with COPD (COPD: 45.5% vs no COPD: 56.2%, p=0.01), whereas the prescription of RAS inhibitors was lower in patients with CKD (CKD: 68.7% vs no CKD: 82.2%, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to treatment strategy

| GDMT (n=892) |

Beta-blocker only (n=228) |

RAS inhibitor only (n=642) |

No GDMT (n=283) |

P value | |

| Age, years | 75.0±6.5 | 76.2±7.2 | 76.7±7.1 | 76.7±6.7 | <0.001 |

| Men, n (%) | 472 (52.9) | 115 (50.7) | 369 (57.5) | 149 (54.0) | 0.211 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.0±3.5 | 22.6±3.5 | 22.4±3.4 | 21.9±3.0 | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Previous heart failure, n (%) | 414 (46.4) | 136 (59.6) | 361 (56.2) | 167 (59.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 609 (68.3) | 162 (71.4) | 417 (65.0) | 174 (63.0) | 0.124 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 399 (44.7) | 97 (42.7) | 242 (37.7) | 119 (43.1) | 0.050 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 430 (48.2) | 150 (66.1) | 320 (49.8) | 186 (67.4) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 281 (31.5) | 89 (39.2) | 193 (30.1) | 81 (29.3) | 0.059 |

| COPD, n (%) | 92 (10.3) | 30 (13.2) | 110 (17.1) | 36 (13.0) | 0.002 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 194 (21.8) | 61 (26.9) | 146 (22.7) | 65 (23.6) | 0.433 |

| Cause of heart failure | |||||

| Ischaemic, n (%) | 443 (49.7) | 129 (56.8) | 311 (48.4) | 146 (52.9) | 0.132 |

| Dilated, n (%) | 222 (24.9) | 36 (15.9) | 147 (22.9) | 50 (18.1) | 0.008 |

| Medication on admission | |||||

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 316 (35.4) | 117 (51.5) | 107 (16.7) | 53 (19.2) | <0.001 |

| RAS inhibitor, n (%) | 380 (42.6) | 58 (25.6) | 335 (52.2) | 72 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| MRA, n (%) | 143 (16.0) | 47 (20.7) | 122 (19.0) | 60 (21.7) | 0.096 |

| Medication on discharge | |||||

| MRA, n (%) | 487 (54.6) | 95 (41.9) | 316 (49.2) | 120 (43.5) | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 714 (80.0) | 174 (76.7) | 493 (76.8) | 189 (68.5) | 0.001 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 269 (30.2) | 63 (27.8) | 193 (30.1) | 86 (31.2) | 0.865 |

| Systolic BP on discharge, mm Hg | 115.0±17.0 | 115.7±16.4 | 114.2±16.5 | 113.0±16.6 | 0.067 |

| Diastolic BP on discharge, mm Hg | 66.1±10.7 | 67.5±10.7 | 65.6±11.2 | 65.2±10.0 | 0.026 |

| Heart rate on discharge, beats/min | 74.6±12.9 | 78.1±14.4 | 77.8±14.3 | 80.6±13.7 | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class on discharge | 0.154 | ||||

| I or II, n (%) | 792 (88.8) | 205 (90.3) | 566 (88.2) | 250 (90.6) | |

| III or IV, n (%) | 100 (11.2) | 22 (9.7) | 76 (11.8) | 45 (9.4) | |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||||

| LVEDD, mm | 60.3±8.7 | 57.6±9.6 | 61.2±8.9 | 58.8±9.0 | <0.001 |

| LVESD, mm | 50.3±9.3 | 47.6±10.0 | 51.1±9.6 | 49.1±9.8 | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 28.8±7.3 | 28.8±7.5 | 28.5±7.4 | 28.6±7.7 | 0.864 |

| Laboratory data on admission | |||||

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 12.4±2.0 | 11.9±2.2 | 12.2±2.1 | 11.7±2.2 | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 63.8±33.8 | 52.6±32.3 | 63.2±30.4 | 53.2±30.1 | <0.001 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 138.0±4.4 | 137.6±4.4 | 137.3±5.1 | 137.0±4.6 | 0.006 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.3±0.7 | 4.4±0.7 | 4.4±0.7 | 4.5±0.8 | 0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 1592.9±1489.8 | 1849.7±1492.0 | 1724.8±1381.7 | 1937.1±1920.8 | 0.223 |

| NT-pro-BNP, pg/mL | 10941.1±11 006.9 | 11535.8±10 587.7 | 9978.0±9484.0 | 14728.7±12 514.7 | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end systolic diameter; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RAS, renin–angiotensin system.

Five hundred and ninety-four patients (29.0%) were already taking beta-blockers before index admission; among them, 27.1% discontinued beta-blockers during index admission and had lower diastolic blood pressure and higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and NT-pro-BNP levels on admission compared with those who continued beta-blockers (online supplementary table 1). When classifying patients according to beta-blocker use (continuation (beta-blocker use before and after admission), new initiation (new beta-blocker prescription during index admission), discontinuation (beta-blocker use before, but discontinuation during index admission) and never use groups (no beta blocker before and after index admission)), there was no difference in survival between patient discontinuation and the never use groups, as well as between those in continuation and new initiation groups (online supplementary figure 1). Regarding RAS inhibitors, 846 patients (41.4%) were already taking RAS inhibitors before index admission. Among them, 15.5% discontinued RAS inhibitors during index admission and had lower eGFR levels and systolic and diastolic blood pressure and higher NYHA functional class, potassium and NT-pro-BNP levels on admission compared with those who continued RAS inhibitors (online supplementary table 2). When classifying the patients according to RAS inhibitor usage patterns, patients who received RAS inhibitors at discharge had better outcomes regardless of previous use than those who did not receive RAS inhibitors (online supplementary figure 1). With increasing age, the proportion of GDMT prescriptions decreased, while that of RAS inhibitors only increased (figure 2B). The predictors of GDMT prescription compared with any of the other three treatment groups included age 65–79 years, hypertension, diabetes, de novo onset of HF and concomitant MRA prescription (table 2). Underlying COPD, CKD and concomitant use of loop diuretics were inversely associated with the prescription of GDMT.

Table 2.

Predictors of prescription of guideline-directed medical therapy compared with any of the other three treatment groups

| Variable | Risk ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Age 65–79 (vs age ≥80) years | 1.28 | 1.14 to 1.43 | <0.001 |

| Male | 0.94 | 0.85 to 1.04 | 0.240 |

| Hypertension | 1.13 | 1.01 to 1.25 | 0.036 |

| Diabetes | 1.14 | 1.03 to 1.26 | 0.014 |

| De novo heart failure (vs previous heart failure) | 1.28 | 1.16 to 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.01 | 0.89 to 1.13 | 0.911 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.86 | 0.77 to 0.96 | 0.004 |

| Ischaemic CMP (vs non-ischaemic) | 0.97 | 0.86 to 1.07 | 0.546 |

| COPD | 0.79 | 0.65 to 0.93 | 0.004 |

| Discharge MRA | 1.16 | 1.05 to 1.28 | 0.007 |

| Discharge digoxin | 0.97 | 0.86 to 1.09 | 0.634 |

| Discharge loop diuretics | 0.84 | 0.72 to 0.98 | 0.018 |

CMP, cardiomyopathy; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

bmjopen-2019-030514supp001.pdf (17.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp002.pdf (450.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp003.pdf (22.9KB, pdf)

Clinical outcomes

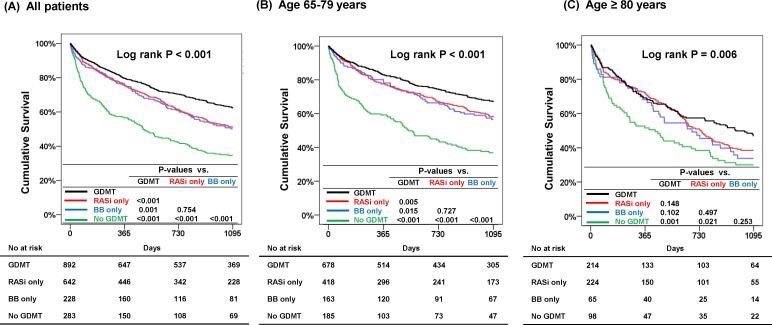

The median follow-up duration was 833 days (IQR: 240.5–1095 days), and 866 (42.3%) patients had died at 3 years. In the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, patients in the GDMT group had the lowest mortality, whereas those in the no GDMT group had the worst outcomes. Interestingly, there seemed to be no difference in mortality between the beta-blockers only and RAS inhibitors only groups (figure 3). On further stratification of the patients according to age above or below 80 years, the GDMT group had the lowest mortality in patients aged above and below 80 years, consistently. In IPTW adjusted population patients in the GDMT group had lower mortality than those in the no GDMT group among the overall patients, patients aged between 65 years and 69 years, and patients aged 80 years or older (online supplementary table 3, online supplementary figure 2). In the Cox model after adjustment for significant covariates, GDMT was associated with a 53% reduced risk of all-cause mortality (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.57, p<0.001) compared with no GDMT. The beta-blockers (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.73, p<0.001) or RAS inhibitors (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.71, p<0.001) only groups were also associated with reduced risk (table 3).

Figure 3.

Three-year cumulative survival according to the treatment groups. Patients receiving GDMT had lower mortality among all patients (A), patients aged between 65 years and 79 years (B) and patients aged 80 years or older (C). BB, beta-blocker; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; RASi, renin–angiotensin system inhibitor.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis for all-cause mortality

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Age ≥80 (vs age 65–79) years | 1.60 | 1.39 to 1.84 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.16 | 1.01 to 1.33 | 0.039 |

| Hypertension | 1.07 | 0.92 to 1.24 | 0.392 |

| Diabetes | 1.13 | 0.99 to 1.31 | 0.080 |

| Previous heart failure (vs de novo heart failure) | 1.39 | 1.20 to 1.60 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.90 | 0.77 to 1.07 | 0.226 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.50 | 1.30 to 1.74 | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic CMP (vs non-ischaemic) | 1.29 | 1.11 to 1.49 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1.27 | 1.04 to 1.53 | 0.016 |

| Discharge MRA | 1.05 | 0.91 to 1.21 | 0.499 |

| Discharge digoxin | 0.99 | 0.84 to 1.16 | 0.885 |

| Discharge loop diuretics | 0.90 | 0.76 to 1.06 | 0.219 |

| Treatment strategy (vs no GDMT) | |||

| Beta-blocker only | 0.57 | 0.45 to 0.73 | <0.001 |

| RAS inhibitor only | 0.58 | 0.48 to 0.71 | <0.001 |

| GDMT | 0.47 | 0.39 to 0.57 | <0.001 |

CMP, cardiomyopathy; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; RAS, renin–angiotensin system.

bmjopen-2019-030514supp004.pdf (27.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp005.pdf (400.8KB, pdf)

Subgroup analysis

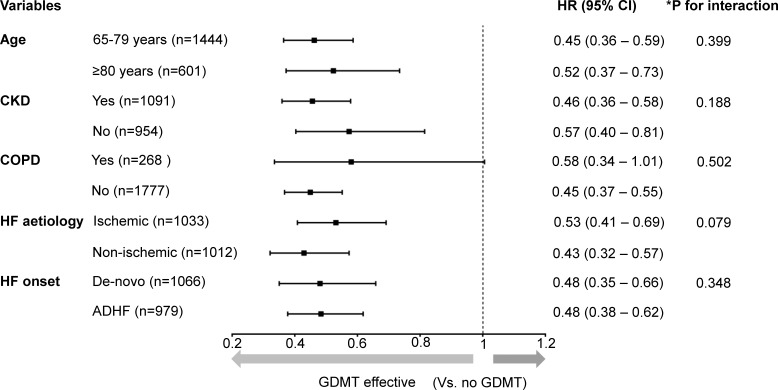

We performed a prespecified subgroup analysis according to age (65–79 years vs ≥80 years), CKD, COPD, aetiology (ischaemic vs non-ischaemic) and HF onset (de novo HF vs acute decompensation of chronic HF). There was no significant interaction between medical therapy and any subgroup (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis. The HRs of medical therapy (ie, GDMT, beta-blockers only and RAS inhibitors only) compared with no GDMT for all-cause mortality in subgroups were calculated using multivariate Cox regression analysis. The forest plots demonstrate the HRs of GDMT versus no GDMT from the results. There was no significant interaction between the treatment strategy (no GDMT, beta-blockers only, RAS inhibitors only and GDMT) and diverse subgroups, and GDMT was associated with lower morality across subgroups. *The p for interaction indicates whether treatment strategy interacts with the subgrouping variable. It was calculated from multivariable Cox regression analysis that included the variables for treatment strategy, subgrouping variables, interaction term of the treatment strategy-by-subgrouping variable, sex, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation and prescription of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, digitalis and diuretics. CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; RAS, renin–angiotensin system.

Discussion

The present nationwide multicentre prospective cohort study showed: (1) GDMT was associated with reduced all-cause mortality in elderly patients with HFrEF; (2) prescription of beta-blockers or RAS inhibitors only was also associated with reduced all-cause mortality compared with no GDMT; and (3) the effect of GDMT also appeared to be effective for reducing all-cause mortality in very elderly patients (age ≥80 years).

GDMT and outcomes in elderly patients with HF

Large clinical trials have shown the efficacy of GDMT in patients with HFrEF.11 However, the patients enrolled in such clinical trials were younger and had fewer comorbidities than real-world elderly patients.18 Moreover, data from clinical trials supporting the use of GDMT in elderly patients are scarce. The Study of the Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalisation in Seniors with Heart Failure (SENIORS) study, which included 2128 patients aged ≥70 years with a history of HF, is considered the representative study conducted in elderly patients with HF. It showed that nebivolol reduced the composite of all-cause mortality and rehospitalisation for HF but did not reduce all-cause mortality.19

Although observational studies do not provide as high a level of evidence as randomised clinical trials, they may yield real-world evidence.20 21 In previous observational studies, the efficacy of beta-blockers in elderly patients has been controversial. In the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry, a beta-blocker was not associated with improved survival in patients aged ≥75 years.20 Dobre et al 22 reported that the effect of beta-blockers decreased with increasing age and was not associated with a reduced risk of cardiac death and readmission HF in patients aged ≥80 years.22 Recently, in a subgroup of 237 elderly patients aged ≥80 years in the West Tokyo Heart Failure (WET-HF) registry, GDMT with beta-blockers and RAS inhibitors did not reduce the rates of cardiac death or HF readmission.23 By contrast, the present study showed that GDMT was associated with all-cause mortality in elderly (≥65 years) patients with HFrEF. In addition, GDMT was effective in very elderly patients (≥80 years). Although the KorAHF and WET-HF studies have included East Asian patients with HF, there are several differences between the studies: KorAHF was larger, especially in terms of the number of patients aged ≥80 years (601 patients in KorAHF vs 237 patients in WET-HF). As a result, our study was less prone to type II errors, such as false negative findings. While WET-HF defined HFrEF as LVEF <45%, the present study enrolled only patients with LVEF ≤40%, which corresponds to the contemporary definition of HFrEF.11 To our knowledge, this is the first report to show the efficacy of GDMT in very elderly patients with HFrEF.

Prescription of GDMT in elderly patients

The prescription rate of GDMT was 50% in patients aged 65–69 years and 30% in those aged ≥85 years. The decline can be mainly attributed to a decreasing beta-blocker prescription rate. Hamaguchi et al 24 reported that the prescription rate of beta-blockers was 48% in HFrEF patients aged ≥80 years and that GDMT was applied only in 38% of these patients.24 In this study, the beta-blocker prescription rate was 55% in all patients and 46% in patients aged ≥80 years. Beta-blockers in very elderly patients may be withheld due to the potential side effects and uncertainty with regard to the benefits for this high-risk group. In addition, 13% of patients had COPD, which was associated with a 30% reduced prescription rate of beta-blockers (beta-blockers in COPD 46% vs no COPD 56%, p<0.001) but not of RAS inhibitors. Accordingly, COPD was associated with a 33% reduced prescription rate of GDMT. This finding reflects the possible side effect of beta-blockers, as non-selective beta-blockers may cause bronchoconstriction in patients with COPD. However, given that multiple studies have shown that beta-1 selective beta-blockers can be used safely in patients with asthma and COPD, beta-1 selective drugs should be considered for patients with COPD.25 26

CKD is very common in patients with HF and is a well-known risk factor in patients with HF.24 27 In this study, 53% of patients had CKD, and its prevalence increased with age. Since RAS inhibitors can initially aggravate renal function, many physicians withhold RAS inhibitors in patients with CKD. Accordingly, CKD was associated with a 54% reduced prescription rate of RAS inhibitors (RAS inhibitors in CKD: 68% vs no CKD: 83%, p<0.001), resulting in a 24% reduced prescription rate of GDMT. By contrast, beta-blocker usage was not influenced by the presence of CKD. Current guidelines recommend the cautious use of RAS inhibitors in patients with HF and advanced CKD.11 Our study supports this recommendation, since RAS inhibitor use was associated with a 34% reduced risk of all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, owing to the observational nature of the study design, confounding factors may have influenced the study results, despite adjustment for significant covariates. Furthermore, there exists a possibility that unmeasured variables may have influenced the results. Second, the registry could not capture all comorbidities including functional or cognitive impairments, which are an important prognostic factor for elderly patients.28 Third, we performed the IPTW analysis to mitigate the impact of compounding factors, but there exists the possibility that variables included in the IPTW analysis had not been sufficiently categorised for producing balanced groups. Fourth, although the KorAHF registry was designed to enrol all hospitalised patients with HF, there exists the possibility that some of the patients may not have been enrolled. Fourth, we did not consider the dosage when defining GDMT. Although there exists controversy on the relationship between drug dosage and outcomes, it should also be investigated in elderly patients.29 Finally, we do not know whether the patients actually took the prescribed drugs, as many patients had multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy is known to be associated with poor drug compliance.

Conclusions

HF is common among the elderly, but elderly patients with HF receive less GDMT. The present study suggests that GDMT may be effective in elderly and very elderly patients with HFrEF, and physicians should make an effort to prescribe GDMT to these high-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

W-WS and JJP contributed equally.

Contributors: W-WS, JJP and D-JC: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. HAP, H-JC, H-YL, KKH, B-SY, S-MK, SHB, E-SJ, J-JK, M-CC, SCC and B-HO: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and acquisition of data.

Funding: This work was supported by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010-E63003-00, 2011-E63002-00, 2012-E63005-00, 2013-E63003-00, 2013-E63003-01, 2013-E63003-02 and 2016-ER6303-00) and by the SNUBH Research Fund (Grant no 14-2015-029 and 16-2017-003).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at each participating tertiary university hospital in Korea (Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, IRB number B1104 125 014; IRB of Seoul National University Hospital, IRB number 1102-072-352; IRB of Yonsei University Severance Hospital, IRB number 4-2011-0075; IRB of Kyungpook National University Hospital, IRB number 2011-04-016; IRB of Asan Medical Center, IRB number 2011-0204; IRB of Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, IRB number KC110IMI0172; IRB of Chonnam National University Hospital, IRB number CHUN-2011-061; IRB of Chungbuk National University Hospital, IRB number 2011-03-008; IRB of Samsung Medical Center, IRB number 2013-040017; IRB of Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, IRB number CR311003).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are housed at the Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American heart association. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:606–19. 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, et al. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J 1999;20:421–8. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, et al. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham heart study subjects. Circulation 1993;88:107–15. 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Youn J-C, Han S, Ryu K-H. Temporal trends of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Korea. Korean Circ J 2017;47:16–24. 10.4070/kcj.2016.0429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murad K, Goff DC, Morgan TM, et al. Burden of comorbidities and functional and cognitive impairments in elderly patients at the initial diagnosis of heart failure and their impact on total mortality: the cardiovascular health study. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:542–50. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah RU, Tsai V, Klein L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of very elderly patients after first hospitalization for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2011;4:301–7. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vidán MT, Blaya-Novakova V, Sánchez E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of frailty and its components in non-dependent elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:869–75. 10.1002/ejhf.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krumholz HM, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:99–104. 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440220103013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med 1992;327:685–91. 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Packer M, Coats AJS, Fowler MB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1651–8. 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, et al. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:550–6. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Statistics Korea , 2017. Available: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/1/index.board?bmode=download&bSeq=&aSeq=363974&ord=1

- 14. Hall MJ, Levant S, DeFrances CJ. Hospitalization for congestive heart failure: United States, 2000–2010. NCHS data brief. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db108.pdf [PubMed]

- 15. Lee SE, Cho H-J, Lee H-Y, et al. A multicentre cohort study of acute heart failure syndromes in Korea: rationale, design, and interim observations of the Korean acute heart failure (KorAHF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:700–8. 10.1002/ejhf.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SE, Lee H-Y, Cho H-J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of acute heart failure in Korea: results from the Korean acute heart failure registry (KorAHF). Korean Circ J 2017;47:341–53. 10.4070/kcj.2016.0419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690–1. 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1682–8. 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJS, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (seniors). Eur Heart J 2005;26:215–25. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O'Connor CM, et al. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, et al. Improving evidence-based care for heart failure in outpatient cardiology practices: primary results of the registry to improve the use of evidence-based heart failure therapies in the outpatient setting (improve HF). Circulation 2010;122:585–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dobre D, DeJongste MJL, Lucas C, et al. Effectiveness of ?-blocker therapy in daily practice patients with advanced chronic heart failure; is there an effect-modification by age? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:356–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02769.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Akita K, Kohno T, Kohsaka S, et al. Current use of guideline-based medical therapy in elderly patients admitted with acute heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and its impact on event-free survival. Int J Cardiol 2017;235:162–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamaguchi S, Kinugawa S, Goto D, et al. Predictors of long-term adverse outcomes in elderly patients over 80 years hospitalized with heart failure. Circ J 2011;75:2403–10. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salpeter S, Ormiston T, Salpeter E. Cardioselective beta-blocker use in patients with reversible airway disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002:CD002992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardioselective β-blockers in patients with reactive airway disease. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:715–25. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Komajda M, Hanon O, Hochadel M, et al. Contemporary management of octogenarians hospitalized for heart failure in Europe: Euro heart failure survey II. Eur Heart J 2008;30:478–86. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murad K, Goff DC, Morgan TM, et al. Burden of Comorbidities and Functional and Cognitive Impairments in Elderly Patients at the Initial Diagnosis of Heart Failure and Their Impact on Total Mortality. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:542–50. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turgeon RD, Kolber MR, Loewen P, et al. Higher versus lower doses of ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-2 receptor blockers and beta-blockers in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212907 10.1371/journal.pone.0212907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030514supp001.pdf (17.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp002.pdf (450.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp003.pdf (22.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp004.pdf (27.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030514supp005.pdf (400.8KB, pdf)