Abstract

Tinnitus remains a scientific and clinical problem whereby, in spite of increasing knowledge on effective treatment and management for tinnitus, very little impact on clinical practice has been observed. There is evidence that prolonged, obscure and indirect referral trajectories persist in usual tinnitus care.

Objective

It is widely acknowledged that efforts to change professional practice are more successful if barriers are identified and implementation activities are systematically tailored to the specific determinants of practice. The aim of this study was to administer a health service evaluation survey to scope current practice and knowledge of standards in tinnitus care across Europe. The purpose of this survey was to specifically inform the development process of a European clinical guideline that would be implementable in all European countries.

Design

A health service evaluation survey was carried out.

Setting

The survey was carried out online across Europe.

Participants

Clinical experts, researchers and policy-makers involved in national tinnitus healthcare and decision-making.

Outcome measures

A survey was developed by the study steering group, piloted on clinicians from the TINNET network and underwent two iterations before being finalised. The survey was then administered to clinicians and policy-makers from 24 European countries.

Results

Data collected from 625 respondents revealed significant differences in national healthcare structures, use of tinnitus definitions, opinions on characteristics of patients with tinnitus, assessment procedures and particularly in available treatment options. Differences between northern and eastern European countries were most notable.

Conclusions

Most European countries do not have national clinical guidelines for the management of tinnitus. Reflective of this, clinical practices in tinnitus healthcare vary dramatically across countries. This equates to inequities of care for people with tinnitus across Europe and an opportunity to introduce standards in the form of a European clinical guideline. This survey has highlighted important barriers and facilitators to the implementation of such a guideline.

Keywords: tinnitus, health-service evaluation, standard of care, pan-European, guidelines, barriers, facilitators

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first and only pan-European health service evaluation to scope current practice and clinical standards in tinnitus healthcare.

Results provide health service information and expert opinions on national healthcare structures, reflecting a truly pan-European point of view.

Results define important barriers and facilitators to propel development and implementation of meaningful and actionable guidelines.

Two of the 24 countries who participated had many more respondents than others, possibly influencing data excessively.

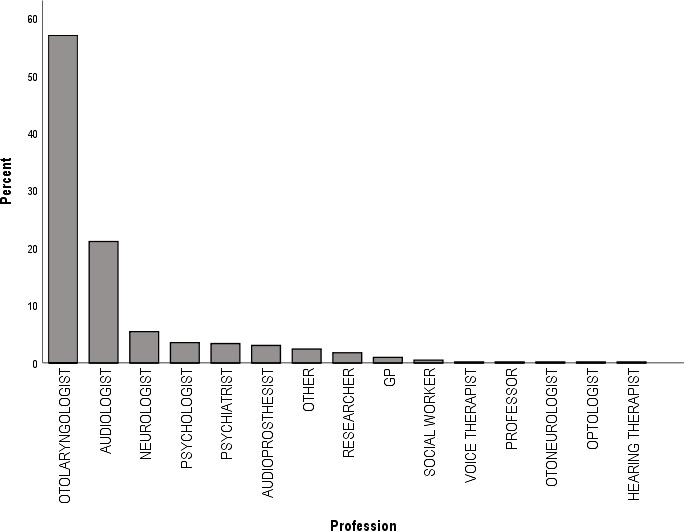

Most respondents were otologists, which might indicate lesser involvement of other disciplines in tinnitus healthcare at present and under-representation of viewpoints in results.

Introduction

Tinnitus, the perception of a phantom sound, is a widespread auditory symptom.1 It can occur with several audiological and/or otological disorders, such as sensorineural hearing loss. In rare cases, tinnitus can be traced to an underlying pathology, though uniform aetiology remains undetermined.2 Epidemiological findings are difficult to pool across studies due to differences in methodologies.3 Nonetheless, assuming a conservative tinnitus prevalence of 10% (severe tinnitus of 1%), tinnitus affects more than 42 million European Union (EU) adults and is a severe problem for more than four million adults. According to data from two large cohorts from Wisconsin (USA), tinnitus prevalence is increasing over time (on average by 1.4% each 5-year birth cohort).4 Assuming this increase is linear and of similar magnitude, prevalence estimates will double by 2050.

Tinnitus is residing within and confined to the individual’s subjective perceptual experience, not measurable or quantifiable by objective physical recordings, and furthermore very rarely traceable to disease, injury or pathology in the brain or elsewhere. Even though knowledge on the pathophysiology of tinnitus has made some progress,5 6 there is still little evidence for effective curative tinnitus treatments or licensed pharmacological therapy.7 The Cochrane Library currently includes nine systematic reviews on different tinnitus treatments,8 all of which are reported to have little, if any, quality evidence.9 Patients report difficulties in concentration, being anxious and distressed, difficulty sleeping, being interrupted in their daily tasks, and feeling helpless and despondent most of the time. A wide range of evidence corroborates the theory that cognitive misinterpretations, negative emotional reactivity and dysfunctional attentional processes are of main importance to the severe tinnitus condition.10–20

From a scientific and clinical perspective, the increased knowledge on treatment and management for tinnitus has had minimal impact on clinical practice.2 There is evidence that prolonged, obscure and indirect referral trajectories persist in usual tinnitus care.21 Tinnitus is indeed a highly complex condition with a multifactorial origin. Heterogeneous patient profiles lead to a lack of consensus on standard assessment and treatment approaches, which in turn again lead to increasing complaints, prolonged suffering and endless referral trajectories, resulting in enormous psychological, societal and economic burden.22

In 2014, the EU approved funding for a 4-year COST Action (TINNET) to create a pan-European tinnitus research network. TINNET’s working group 1 (WG1) consists of clinical and academic experts in tinnitus from across Europe whose joint objective is to develop meaningful and actionable clinical guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with tinnitus, and to provide a consensus-based clinical definition and characterisation of tinnitus (http://tinnet.tinnitusresearch.net/index.php/2015-10-29-10-22-16/wg-1-clinical). Ultimately, a European multidisciplinary clinical guideline would be a first step toward a common minimum standard of care for patients with tinnitus across Europe.23 To ensure from a development perspective that a European guideline would become implementable, it became essential to scope current existence and knowledge of standards in tinnitus care across the continent. Without knowledge on the current ‘state of the art’ and standards in tinnitus healthcare, a consensus-based, meaningful and actionable guideline could not be ensured. It is widely acknowledged that efforts to change professional practice are more successful if barriers are identified and guidelines for implementation activities are systematically tailored to the specific determinants of practice.24 As such, a pan-European survey of clinicians and policy-makers was carried out to gain service information and expert opinions on national healthcare structures, tinnitus definition, general characteristics of patients with tinnitus, and assessment and treatment options.

Methods

The method for scoping current knowledge, opinion and practices in tinnitus care across Europe, a web-based survey was developed by consensus of members within TINNET WG1. Participation was on a voluntary basis and all data were submitted anonymously.

Survey development

The survey was developed during three consecutive WG1 meetings. It was agreed that the survey would be developed in the English language, since it was expected that most responders would be able to understand English, irrespective of the country of origin. The development involved two phases. First, based on their shared knowledge of tinnitus, nine members of the WG1 steering group generated a list of domains of interest, formulated a set of questions for each domain and generated a set of response options for each question. This list of questions was subsequently piloted in a larger group of WG1 members (n=81) via email, and during a WG1 management meeting. Consensus rounds were used to either include or exclude items. The remaining survey items were then re-disseminated to all WG1 members who had been involved in the development and piloting stages with a request to provide comments on any necessary alterations, changes to wording or response options and for any general remarks. A final survey was agreed on and produced for online dissemination using Google forms. The final survey contained items grouped as (1) demographics, (2) national healthcare structure, (3) tinnitus definitions and characteristics of the patient with tinnitus and (4) management, treatment and diagnostics.

Participants

The recruitment targeted clinical experts, researchers and policy-makers involved in national tinnitus healthcare and decision-making. A total of 625 participants were recruited using the COST-TINNET network. First, members of the management committee of TINNET were contacted via email with a link to the survey (online supplementary information 1 provides the questions used in the survey) and were requested to forward the invitation to clinical experts, researchers and tinnitus- organisations in their respective countries (n=24; table 1). Second, another round of targeted dissemination was performed in July 2015, as at that time it was noted that there was a lower response rate from some countries. The low response rate from Italy and Spain was identified as being a language barrier and therefore the survey was translated by native-speaking TINNET members and redistributed in their national language. The reason for low responses from other countries was not identified. The survey was open from January to October 2015.

Table 1.

Classification and percentage of respondents according to region; 1=North, 2=South, 3=East

| Country | Region | n per country | n per region | Total % |

| Region 1 | 216 | 34.6 | ||

| Austria | 1 | 1 | ||

| Belgium | 1 | 54 | ||

| Denmark | 1 | 14 | ||

| Finland | 1 | 1 | ||

| France | 1 | 39 | ||

| Germany | 1 | 28 | ||

| The Netherlands | 1 | 41 | ||

| Sweden | 1 | 23 | ||

| Switzerland | 1 | 3 | ||

| UK | 1 | 12 | ||

| Region 2 | 225 | 36.0 | ||

| Cyprus | 2 | 2 | ||

| Greece | 2 | 29 | ||

| Italy | 2 | 50 | ||

| Israel | 2 | 12 | ||

| Malta | 2 | 9 | ||

| Portugal | 2 | 64 | ||

| Spain | 2 | 59 | ||

| Region 3 | 184 | 29.4 | ||

| Albania | 3 | 2 | ||

| Croatia | 3 | 2 | ||

| Czech Republic | 3 | 68 | ||

| Lithuania | 3 | 82 | ||

| Poland | 3 | 19 | ||

| Serbia | 3 | 8 | ||

| Slovenia | 3 | 3 | ||

| Total | 625 | 625 | 100 |

bmjopen-2019-029346supp001.pdf (23.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The aim of the current study falls within the framework and main aims of the COST TINNET project. The project, and in particular working package 1, focused on the objective ‘Clinical and audiological assessment of patients with tinnitus according to common standards’. The current study was an essential step in the roadmap toward the aim of the project.25 In the development and execution of the TINNET project, patient organisations throughout Europe were consulted and were actively involved in several stages. In the current survey, no individual patients were recruited, nor were they involved, since this study involved the evaluation of health services by clinicians, policy-makers and individual professional expert opinions on national healthcare structures. Results of the current study were disseminated to all existing European patient organisations using a Delphi consensus methodology in the development of harmonised and adaptive clinical European guidelines for tinnitus entitled ‘Multidisciplinary European Guideline for Tinnitus: Diagnostics, Assessment and Treatment’.23 These have been presented to the scientific community as well as national patient organisation symposia.

Analyses

Results were first described and depicted descriptively. Because the number of responses from each country differed, data were stratified according to whether the country was in northern (higher income), southern (moderate income) or eastern (lower income) Europe (table 1) (online supplementary information 2 gives the average monthly net income per country and per region). The rationale for this classification was that economic prosperity might lead to differences in healthcare for patients with tinnitus, since lesser resources indicate lower availability of specialised healthcare. One-way analysis of variance and regression analyses were performed to assess differences and associations between variables in northern, southern and eastern countries. All analyses were performed in IBM-SPSS V.23.

bmjopen-2019-029346supp002.pdf (14.3KB, pdf)

Results

Demographics

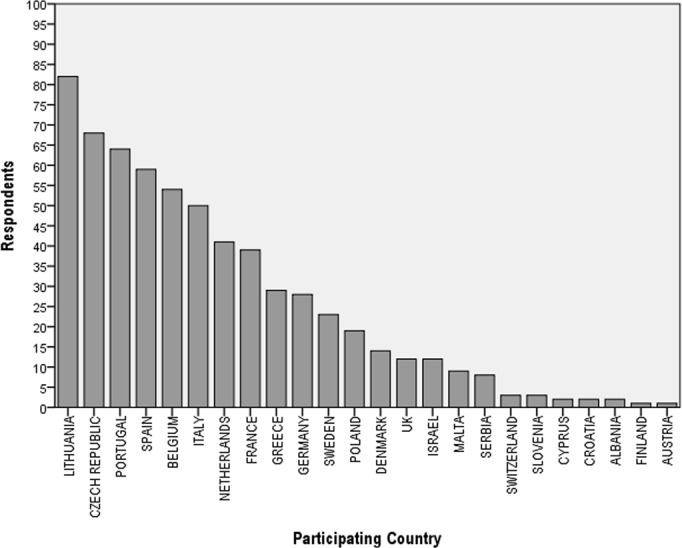

Survey responses (n=625) were received from participants across 24 countries (figure 1) with a large number of participants from Lithuania, Czech Republic, Portugal and Spain. The mean age of respondents was 43.9 years (SD=12.4), 49.7% were male and 50.3% were female. Respondents were from many disciplines (figure 2) and worked in public healthcare (n=291), private healthcare (n=199), university (n=89) or other setting (n=48). Some respondents reported more than one workplace (n=213).

Figure 1.

Responses from each participating country.

Figure 2.

Discipline of respondents. GP, general practitioner.

National healthcare structure

Across all three regions of Europe, tinnitus healthcare was in most cases financed by national health insurances. This was particularly evident for eastern countries, where 90.8% of respondents reported that their service is publicly funded. Privately funded treatment was most common in southern Europe (48%) (online supplementary information 3).

bmjopen-2019-029346supp003.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

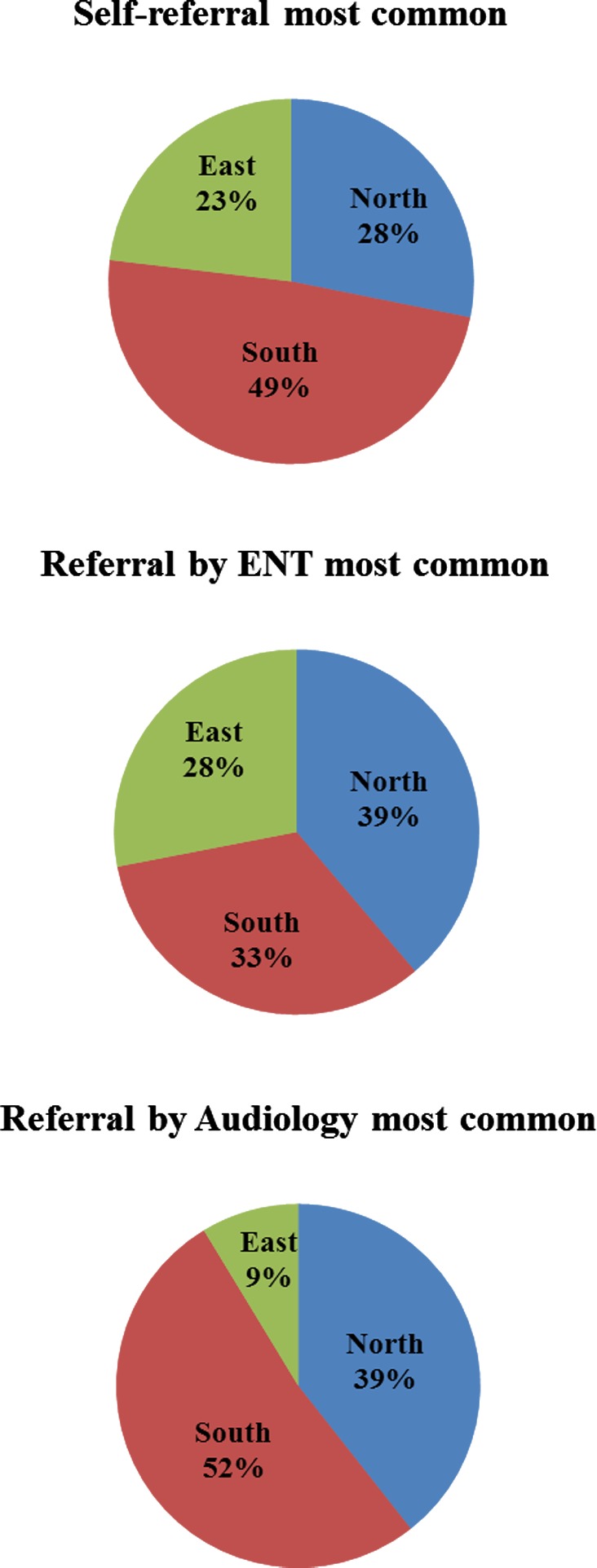

The most common referral pathways and the description of services and patient’s status are given in figure 3 and table 2, respectively. In taking a regional perspective, difference across Europe became clear. Specialised tinnitus clinics (or teams) were perceived to be most present in the northern regions (more than 50% of respondents confirmed), where referral by ENT and/or audiology seems common. Whereas in southern Europe, many people appeared to self-refer to specialists, in eastern Europe referral opinions varied or were less understood by respondents. More northern European respondents reported having and using clinical guidelines (online supplementary information 4) than respondents from southern or eastern Europe.

Figure 3.

Most common referrals according to region. ENT, ear, nose and throat.

Table 2.

View of ‘tinnitus’ and emotional status of patients, classified according to region

| North | South | East | Sign. | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| What is tinnitus? | |||||||

| A central auditory disease | 8 | 3.7 | 9 | 4.0 | 17 | 9.2 | |

| A central auditory symptom | 88 | 40.7 | 64 | 28.4 | 37 | 20.1 | |

| A peripheral auditory disease | 11 | 5.1 | 17 | 7.6 | 12 | 6.5 | |

| A peripheral auditory symptom | 100 | 46.3 | 126 | 56.0 | 110 | 59.8 | |

| A psychological disease | 4 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Combination/multiple causes/other | 5 | 2.3 | 6 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Cannot answer/does not know | 2 | 0.9 | |||||

| Chronic or acute? | n.s. | ||||||

| Chronic (>3 months) | 123 | 56.9 | 144 | 64.6 | 104 | 56.5 | |

| Acute (<3 months) | 19 | 8.8 | 18 | 8.1 | 27 | 14.7 | |

| Both | 74 | 34.3 | 61 | 27.4 | 53 | 28.8 | |

| Emotional status of most patients | † | ||||||

| Very positive | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Somewhat positive | 22 | 10.2 | 22 | 9.9 | 25 | 13.6 | |

| Neutral | 56 | 25.9 | 102 | 45.7 | 96 | 52.2 | |

| Somewhat distressed | 113 | 52.3 | 87 | 39.0 | 43 | 23.4 | |

| Very distressed | 24 | 11.1 | 12 | 5.4 | 15 | 8.2 | |

*Difference between north compared with south and east (α<0.05).

†Different between all groups (α<0.05).

n.s., not significant; Sign., significant difference.

bmjopen-2019-029346supp004.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Tinnitus, definitions and characteristics of the patient with tinnitus

In all regions, more experts reported that, in their opinion, tinnitus is either a central auditory symptom (table 2). Still, more than 10% from all regions considered tinnitus a disease, whether auditory or psychological. Differences were found between higher and lower income regions with respect to the perceived emotional status of their ‘typical’ patients (table 2) and the time spent with individual patients during the first consultation (table 3). The majority of respondents from northern Europe (41.7%) reported spending between 30 and 60 min with patients with tinnitus on the first appointment, in contrast to 43.9% in the south and 56% in the east spending between 15 and 30 min. Patients in northern Europe were evaluated as being more often ‘somewhat distressed’ in comparison to a more ‘neutral’ status in the south and east (see also online supplementary information 5).

Table 3.

Appointment duration and number of patients per month, classified according to region

| North | South | East | Sign. † | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | * | |

| Duration of the first consultation | |||||||

| Less than 15 min | 23 | 10.6 | 37 | 16.6 | 55 | 29.9 | |

| 15 to 30 min | 51 | 23.6 | 98 | 43.9 | 103 | 56.0 | |

| 30 to 60 min | 90 | 41.7 | 58 | 26.0 | 21 | 11.4 | |

| 60 to 120 min | 44 | 20.4 | 25 | 11.2 | 5 | 2.7 | |

| More than 120 min | 8 | 3.7 | 5 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| No of patients per month | * | ||||||

| ≤10 | 73 | 33.8 | 117 | 52.2 | 101 | 54.9 | |

| 11–30 | 96 | 44.4 | 87 | 38.8 | 61 | 33.2 | |

| 31–50 | 33 | 15.3 | 12 | 5.4 | 9 | 4.9 | |

| >50 | 14 | 6.5 | 8 | 3.6 | 13 | 7.1 | |

*Different between all groups (α<0.05).

†Difference between north compared with south and east (α<0.05).

Sign, significant difference.

bmjopen-2019-029346supp005.pdf (340.6KB, pdf)

Management, treatment and diagnostics

All treatments available within their respective departments were reported (table 4). Where medication was selected as an available option, the respondent were asked to indicate the specific drug in the ‘other’ free-text space. Here, sound therapy is taken to include the use of hearing aids, and Tinnitus Retraining Therapy includes any reportedly modified version of the treatment.

Table 4.

Treatments reported as available within respondents’ departments, reported by region

| North (n) | % | South (n) | % | East (n) | % | |

| Advice | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alternative therapies | 16 | 7.5 | 33 | 14.7 | 19 | 10.3 |

| CBT | 74 | 34.3 | 35 | 15.6 | 9 | 4.9 |

| Counselling | 108 | 50 | 115 | 51.1 | 41 | 22.3 |

| Coping training | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dental procedure | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medication | 59 | 27.3 | 111 | 49.3 | 147 | 79.9 |

| Mindfulness | 5 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurofeedback | 16 | 7.4 | 13 | 5.8 | 9 | 4.9 |

| Physiotherapy | 52 | 24.1 | 27 | 12 | 59 | 32.1 |

| Relaxation | 108 | 50 | 71 | 31.6 | 34 | 18.5 |

| rTMS | 14 | 6.5 | 3 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.6 |

| Sound therapy | 151 | 69.9 | 154 | 68.4 | 49 | 26.6 |

| TRT | 1 | 0.5 | 69 | 30.7 | 29 | 15.8 |

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; rTMS, repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; TRT, Tinnitus Retraining Therapy.

Medications used in tinnitus treatment included betahistine, steroids, vasodilators, antidepressants and anxiolytics. ‘Other’ treatment options reported as available were hyperbaric chamber therapy, laser therapy, transcranial direct current stimulation, Gingko biloba, vitamin B12, hypnosis, sleep hygiene, osteopathy, cochlear implantation and music therapy. Differences in treatment availability across regions were striking, particularly between the north and east. Indicative of the general trends, cognitive–behavioural therapy was available from 34.3% of departments in northern Europe, compared with just 4.9% in the east. In contrast, medication was an option in 79.9% of the departments in the east, whereas only 27.3% used medications in the north. While medication was the most commonly available treatment option in the east, in both the north and south it was sound-based therapy (in 69.9% and 68.4% of departments, respectively).

Clinicians involved in tinnitus care ranged from just one discipline to a broad multidisciplinary team (table 5). Multidisciplinary treatments (MDTs) and having a psychologist in the team was more common in northern countries than in the east and south. In the east, most care appears to be delivered by medical professionals (otolaryngologists or neurologists). Other disciplines involved in tinnitus care, reported by 1%–2% of respondents, included prosthetists, social workers, movement therapists, osteopaths, sophrologists, psychosomatic medicine specialists, acupuncturists, hearing therapists, ophthalmologist, dance movement therapists, general practitioners (GPs), cardiologists, maxillofacial surgeons and radiologists. There were single reports of an arts therapist, counsellor, speech therapist, mindfulness instructor and hypnotherapist being involved in care.

Table 5.

Disciplines involved in tinnitus care

| North | % | South | % | East | % | |

| ENT | 118 | 54.6 | 43 | 19.1 | 87 | 47.3 |

| Audiologist | 132 | 61.1 | 39 | 17.3 | 57 | 31 |

| Psychologist | 136 | 63 | 32 | 14.2 | 24 | 13 |

| Psychiatrist | 33 | 15.3 | 39 | 17.3 | 39 | 21.2 |

| Physiotherapist | 19 | 8.8 | 3 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.6 |

| Neurologist | 20 | 9.3 | 19 | 8.4 | 81 | 44 |

| Dentist | 3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

ENT, ear, nose and throat.

Conditions and or symptoms perceived as being of relevance when assessing and/or treating tinnitus are given in table 6. Most respondents reported hearing loss and dizziness complaints as relevant, irrespective of the region.

Table 6.

Opinions on which conditions are taken into consideration in tinnitus diagnostics

| North | % | South | % | East | % | |

| Hypertension | 98 | 45.4 | 118 | 52.4 | 79 | 42.9 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 20.8 | 108 | 48 | 55 | 29.9 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| TMJ disorders | 92 | 42.6 | 125 | 55.6 | 28 | 15.2 |

| Psychological/psychiatric disorders | 155 | 71.8 | 163 | 72.4 | 73 | 39.7 |

| Hearing loss | 212 | 98.1 | 221 | 98.2 | 159 | 86.4 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 16 | 7.4 | 61 | 27.1 | 31 | 16.8 |

| Dizziness | 191 | 88.4 | 200 | 88.9 | 161 | 87.5 |

| Cervical disorders | 100 | 46.3 | 98 | 43.6 | 94 | 51.1 |

| Migraine | 72 | 33.3 | 83 | 36.9 | 41 | 22.3 |

| Allergy | 21 | 9.7 | 35 | 15.6 | 11 | 6 |

TMJ, Temporomandibular Joint.

Other conditions frequently reported by respondents as of relevance to tinnitus were suicidal tendency, otitis, eustachian tube dysfunction, acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis and coagulation disorder. A minority (≤1%) additionally reported hyperacusis, autoimmune disease, neurovascular conflict, Pendred syndrome, stress, psychosis, nasal septal deformation, vascular disease, facial pain, sensory hypersensitivity, cardiac arrhythmia, arterial stenosis, sleep disorders, hypercholesterolaemia, fibromyalgia, apnoea and rhinosinusitis.

There was a general consensus on the diagnostic tools to be used to assess patients with tinnitus in clinical practice (table 7). Most respondents reported that otoscopy and pure tone audiometry were used. There was some variability in the reported use of other diagnostic tools; for example, percentage use of audiological assessments such as tympanometry or speech audiometry in the north was twice than that in the east. ‘Other’ responses included clinical interview, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, vestibular-evoked myogenic potential, brainstem-evoked response audiometry, tone decay, neck vessel ultrasonography, orthopantomography, blood analysis, vestibular testing (calorimetry), blood pressure and auditory brainstem response, all of which were reported by ≤3% of respondents.

Table 7.

Diagnostic tools used for patients with tinnitus

| North | % | South | % | East | % | |

| Otoscopy | 169 | 78.2 | 211 | 93.8 | 135 | 73.4 |

| Tympanometry | 142 | 65.7 | 172 | 76.4 | 56 | 30.4 |

| Nasal endoscopy | 37 | 17.1 | 87 | 38.7 | 147 | 79.9 |

| Pure tone audiometry | 162 | 75 | 186 | 82.7 | 151 | 82.1 |

| High-frequency audiometry | 64 | 29.6 | 48 | 21.3 | 27 | 14.7 |

| Speech audiometry | 119 | 55.1 | 93 | 41.3 | 44 | 23.9 |

| Tinnitus pitch and loudness | 95 | 44 | 86 | 38.2 | 46 | 25 |

| LDL | 2 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| MML | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RI | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Broadband noise EP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pure tone EP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (DP)OAE | 68 | 31.5 | 54 | 24 | 35 | 19 |

| AC-ASSR | 9 | 4.2 | 18 | 8 | 4 | 2.2 |

| Electroencephalogram | 14 | 6.5 | 3 | 1.3 | 16 | 8.7 |

| CT | 17 | 7.9 | 34 | 15.1 | 44 | 23.9 |

| MRI | 76 | 35.2 | 119 | 52.9 | 100 | 54.3 |

| Angio-MRI | 28 | 13 | 37 | 16.4 | 19 | 10.3 |

AC_ASSR, Air Conduction - Auditory Steady State Response; DP(OAE), Distortion Product (Oto-Acoustic Emissions); EP, Evoked Potential; LDL, Loudness Discomfort Level; MML, Minimum Masking Level; RI, Residual Inhibition.

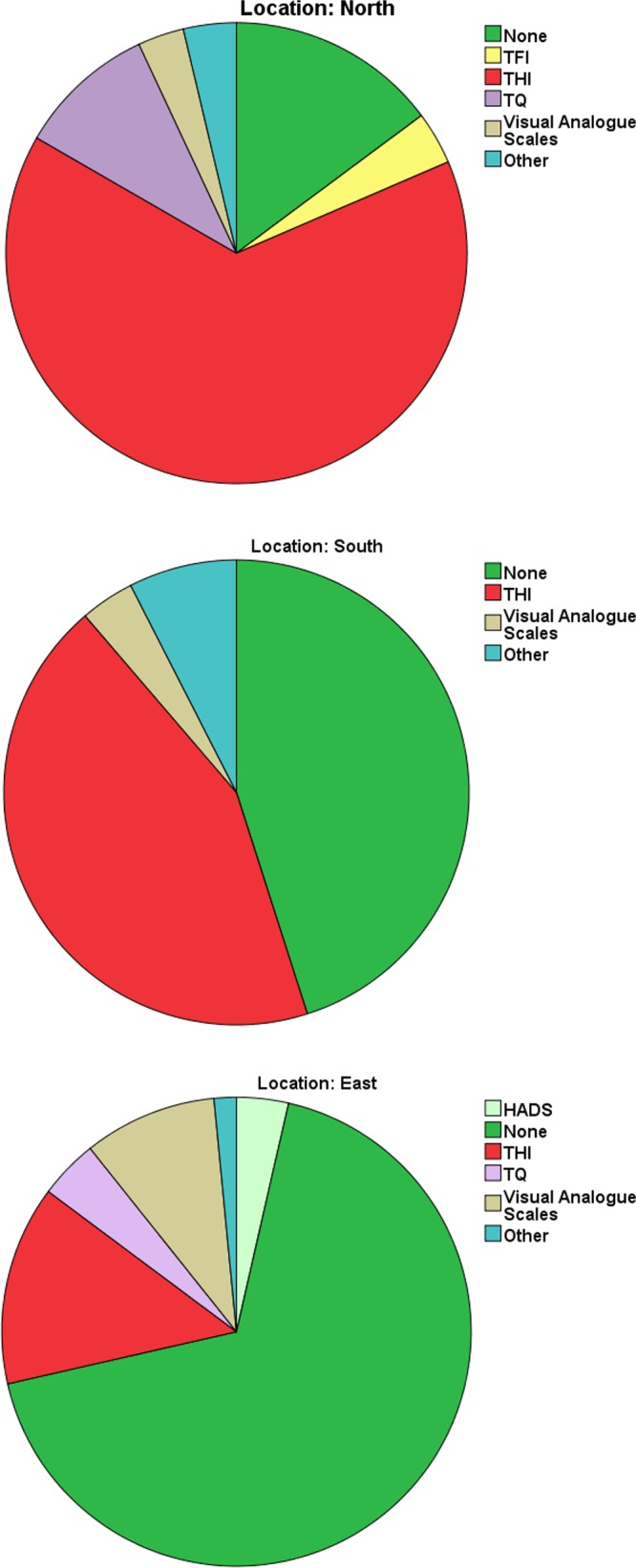

Most respondents from northern and southern countries reported using some form of multi-item questionnaire, in comparison with only about one in five respondents from eastern European countries (figure 4). The most frequently used questionnaire, irrespective of region was the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI).26 Interestingly, the only anxiety/depression questionnaire used was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale27 and only in eastern countries. The Tinnitus Questionnaire28 was mentioned frequently in northern and southern regions. The more recently developed Tinnitus Functional Index29 was only mentioned in the north. Additionally, respondents from all regions specified to use Visual Analogue Scales (though unspecified which) as well. Questionnaires reported as ‘other’ were unspecified.

Figure 4.

Main questionnaire used per region. HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; TFI, Tinnitus Functional Index; THI, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; TQ, Tinnitus Questionnaire.

Finally, regarding the satisfaction rate on the service provided by their healthcare unit, 81.7% respondents from the north, 38.5% from the south and 35.0% from the east reported they were satisfied. In northern Europe, professionals were largely satisfied, whereas in southern and eastern Europe, opinions were more divided, and less than half of respondents claimed to be satisfied.

Regression analyses

Regression analyses were conducted to establish whether there were statistically significant associations between average net income of the country of origin of respondents and the presence of specialised tinnitus clinics, time for patients with tinnitus per consult, satisfaction of the respondent with their service, number of patients seen per month, the requirement of a referral by GP in their country and whether or not clinical guidelines exist. Significant associations were found between net income per month and all variables in the model (table 8). In summary, higher income was associated with more specialised clinics, longer appointment times, greater satisfaction with healthcare options, fewer patients per month, more referral necessity by GP, and more knowledge and use of clinical guidelines.

Table 8.

Associations between income and tinnitus care

| Model | Change statistics | Beta | Significant F change | |||

| R2 change | F change | df1 | df2 | |||

| Age/gender | 0.007 | 1.989 | 2 | 605 | −0.033 | 0.138 |

| Specialised clinic | 0.266 | 220.407 | 1 | 604 | −0.516 | 0.000 |

| Time per consult | 0.106 | 102.780 | 1 | 603 | 0.334 | 0.000 |

| Satisfaction healthcare | 0.048 | 50.505 | 1 | 602 | −0.235 | 0.000 |

| Patients per month | 0.015 | 15.728 | 1 | 601 | 0.124 | 0.000 |

| GP necessary | 0.010 | 10.507 | 1 | 600 | −0.106 | 0.001 |

| Clinical guidelines | 0.008 | 9.272 | 1 | 599 | 0.094 | 0.002 |

Regressions summary: Dependent=income, Independents=Specialised clinics present, time per consult, Satisfaction of respondent with healthcare, Patients seen per month, necessity of referral by GP, existence of clinical guidelines, controlled for age and gender.

Coding: Specialised clinic: Yes=0, No=1; Time per consult: 1=<15 min, 2=15–30 min, 3=30–60 min, 4=60–12 min, 5=>120 min; Satisfaction healthcare: Yes=0, No=1; GP necesary: Yes=0, No=1; Clinical guidelines: Yes=0, No=1. Dependent: income.

GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

This survey sought to collate details and opinions on healthcare structure and clinical practices for tinnitus across Europe. The first interesting result from the survey was the difference between regions of Europe in terms of whether specialist tinnitus clinics were present. In the northern countries of Europe, most respondents confirmed the presence of specialised tinnitus clinics, in the South about half confirmed having specialist centres and in the East most respondents reported not having specialised clinics. That there seems to be discord in knowledge or opinions in the rest of Europe is interesting. Where there are indeed specialised clinics, which professionals are aware of, they might more easily refer patients to these clinics without the need for a GP. On the other hand, when fewer clinics are present or known, tinnitus care more often falls to the GP, who might refer to a specialist, but not necessarily to a specialised centre. Opinions differed on whether a referral from a GP is necessary; the majority of respondents from eastern Europe reported that it is indeed the case, whereas in northern and southern Europe less than half of respondents thought so. These findings indicate the importance of knowing the referral path. Addressing the lack of clinician’s knowledge is key in the development of meaningful and actionable European guidelines. The lack of knowledge of existing specialised clinics also points to difficulties patients are likely to encounter in identifying the most appropriate healthcare. An uncertain healthcare journey and the lack of clear referral pathways is likely to exacerbate ongoing tinnitus distress, severity and chronicity.

In terms of national healthcare structure, the typical pathways differed by region. In the north, they most commonly include specialised audiologists and otolaryngologists, who can presumably refer onto specialist centres where available. In southern Europe, it was more common that people self-refer for tinnitus care. In eastern Europe, referral pathways were either less understood or less well-defined.

When asked which disciplines usually ‘handle’ patients with tinnitus, the mix of disciplines reported was more evenly distributed across the counselling and medical professions in northern countries than other regions, that is, tinnitus care was not more associated with one type of healthcare professional than another. In contrast, in southern and eastern countries it was reported that medical and technical professionals were most commonly involved. Interestingly this indicates a tendency toward a ‘psychological’ approach in the north compared with a more curative approach in tinnitus treatment in the other regions. Since there is ample evidence that psychological therapy is beneficial in any tinnitus treatment approach, and that there are regions in Europe where this is not provided, these findings highlight a second barrier to the adoption and implementation of a Europe wide practice guideline.

In all regions, most experts reported that in their opinion tinnitus is a central auditory symptom, which might indicate agreement between the regions, and offers a first facilitator. This data will be useful in achieving a consensus definition of tinnitus within a European guideline. Interestingly, respondents from northern countries more often reported their average patients to be distressed, whereas most respondents from the south and east judged their patients to be neither distressed nor ‘positive’, but to be of a ‘neutral’ emotional status. This could indicate that in the north, the range of patients that are seen by experts is broader, that is, patients with milder as well as more severe tinnitus are assessed by specialists. It is also possible that since northern countries dedicate more time per patient, physicians are more able to assess levels of distress. It might also reflect a greater awareness of the emotional distress of patients since in the north, a psychological assessment including clinical questionnaires is more often conducted. This is of interest because the level of distress of patients with tinnitus is an important indicator of the need for onward referral for subsequent treatment options. A third barrier to the implementation of a European guideline may therefore be that in most regions of Europe, professionals responsible for patients with tinnitus do not have a sufficient amount of time to adequately assess the level of distress of their patients.

The presence of an MDT teams for tinnitus in northern regions was reported in most cases, including a psychologist working in most teams. By region however, it is noted that in the south many respondents report that there are no MDT teams, and in the east there was almost no psychologists involved in treatment. These findings represent a major fourth barrier in developing the development of meaningful and actionable European guidelines, if the guideline is to include evidence-based healthcare.

There is consensus across the regions on which conditions are important in tinnitus. Most respondents, irrespective of region, reported hearing loss, acoustic trauma and vertigo as the most relevant conditions to consider in the assessment of tinnitus. This consensus represents a second facilitator in discussions on and implementation of European guidelines.

The treatment options reported by respondents also showed clear trends according to region. This finding can be classified as a fifth barrier, in that it might be difficult to get consensus on what works for whom when many treatment avenues are preferentially made available. When developing a guideline, it is of importance to provide clear indications on which treatments are recommended, which are not recommended and which have insufficient evidence to make a recommendation in either direction.30

There was consensus on the diagnostic tools to be used to assess patients with tinnitus in clinical practice. Although some small differences in procedures were reported, most experts use otoscopy and pure tone audiometry. There is some variability in the use of other diagnostic tools suggesting a potential third facilitator to discussions, on the inclusion of standardised diagnostic procedure in the guidelines.

A sixth barrier to standardised practice emerging from our data may be the limited use of clinical questionnaires in eastern and southern countries. Yet consensus exists that in research as well as the clinic questionnaires are key in assessment, both for screening and monitoring treatment progress.2 31 The most commonly used questionnaire however, irrespective of region, was the THI. This finding is consistent with a previous study.32 This might offer a fourth facilitator to discussions, on primary outcome measures to recommend within a guideline.

When asked how patients pay for treatment, respondents from southern and eastern Europe reported fewer patients pay privately for their tinnitus healthcare. Nonetheless, in all regions, tinnitus treatments were financed by national health insurance schemes. This may become restrictive if health insurance companies have a strong influence on what tinnitus treatment options are made available within a country. When patients pay for treatment privately, more treatment options might be on offer, even without adequate evidence of effectiveness. That there are differences in how patients pay for treatment is a seventh barrier to standard care across Europe, and a difficult one. In cases where the regulatory bodies in healthcare in a country are unwilling or unable to hold to the restrictions or recommendations stated in a guideline, the chances of implementation of this guideline drastically decrease.

Less than half of respondents from the south and east of Europe reported they were satisfied with current tinnitus healthcare in their country. This dissatisfaction may represent a fifth facilitator in that professionals are likely to be positive about progressive guidelines and toward changes in healthcare for tinnitus.

Finally, economic prosperity in a country often defines healthcare organisation and healthcare satisfaction.33 In the current study, it was hypothesised that the economic resources available to individuals in a country might dictate the view of professionals on levels of advancement in healthcare for tinnitus. This was indeed the case. Lower average net income in the country of origin of respondents was associated with reports of less specialised tinnitus healthcare, fewer specialised tinnitus clinics, less time for patients with tinnitus per consult and more often a lack (or use) of guidelines. Lower average income was also associated with lower satisfaction of the respondent with healthcare, and more necessity of referral by a GP. Interestingly, higher average net income in a country was associated with seeing more patients per month.

Some additional points are worthy of discussion. First, from the 24 countries who participated in the survey, some had many more respondents than others. This issue was presently solved by stratifying the countries according to region of Europe to yield similar respondent numbers per region. Nevertheless, responses from Lithuania and the Czech Republic might have a strong influence on the eastern region data, because of the large number of respondents from these countries. Second, most respondents were otologists. The large (over)representation of this discipline might indicate that other disciplines are less involved in tinnitus healthcare, and that current reports rely heavily on the clinical views and experiences of otologists and might not reflect views or opinions of professionals of other disciplines. Third, it is important to note that the current findings do not necessarily indicate or reflect a right or wrong in the organisation of tinnitus healthcare, the available assessment and treatment options for tinnitus in a country or the advancement of specialised healthcare in a country. It is important that the current results are seen in the light of establishing potential facilitators and barriers (see box 1 below for summary) to the development and implementation of a guideline that can serve the whole of Europe, by being meaningful and actionable, and offer advice and options for professionals in the field, and the patients they care for.

Box 1. Summary of barriers and facilitators.

Barriers

Lack of knowledge about or non-existence of specialised tinnitus clinics or teams makes it difficult for patients with tinnitus to find their way to the most appropriate professionals in a country.

Lack of time or other resources for adequate counselling.

Lack of time or other resources for professionals responsible for patients with tinnitus to be able to adequately assess the distress level of patients with tinnitus.

Lack of multidisciplinary teams and/or availability of psychologists in southern and eastern European countries.

High variation in available treatment options; more medical-pharmacological treatment in southern and eastern countries. Psychological-rehabilitative approaches more available in northern countries. When many treatment avenues are considered viable, it may be difficult to reach consensus on what works for whom.

The use of self-report instruments is much less common in southern and eastern countries.

There are differences in how patients pay for treatment. If regulatory bodies in healthcare in a country are unwilling or unable to hold to the restrictions or recommendations stated in a guideline, the likelihood of implementation of this guideline is lower.

Facilitators

Common ground in expert opinion that tinnitus is a central auditory symptom. This offers options for discussions on the definition of tinnitus in a European guideline.

Consensus across regions on what conditions are relevant or associated with tinnitus. Harmonies such as these are to be highlighted where possible to facilitate implementation of a standard guideline.

Though some small differences in procedures were reported, most experts use otoscopy and pure tone audiometry. Findings will facilitate discussions on diagnostics to include in the guidelines.

The most commonly used questionnaire irrespective of region is the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. This may facilitate discussions on assessment methods to recommend within a guideline.

The percentage of respondents satisfied with current tinnitus healthcare in their country in southern and eastern Europe was low; less than half of respondents reported they were satisfied. Healthcare professionals are likely to be positive toward progressive guidelines and toward changes in healthcare for tinnitus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all participating professionals, who have dedicated their limited time to address our queries. We are also grateful to all project members, work package leaders and management of TINNET (COST Action, number BM1306, a European tinnitus research network funded from 11 April 2014 to 10 April 2018), who disseminated our requests for participation in their respective countries and networks. Special thanks are due to Thomas Fuller who attended some of the discussions in the final stages and offered valuable insight and assistance during consensus voting.

Footnotes

Twitter: @RilanaCima, @CederrothCR, @Derek_J_Hoare

Contributors: RFFC wrote the first draft of the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses. DK and TB developed and designed the online questionnaire and performed preliminary analyses. DJH provided extensive feedback on the initial draft and cowrote further versions of the manuscript. All remaining authors (BM, HH, CRC, AN, AL, TB) provided feedback and offered critical analyses of the main text and results on all drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: The current investigation was funded by the European Commission by under the COST program; Project TINNET with Action number BM1306, a European tinnitus research network funded from 11 April 2014 to 10 April 2018. RFFC is funded through The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research; Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni. DJH is funded through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre programme.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the National Health Service or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Martinez C, Wallenhorst C, McFerran D, et al. Incidence rates of clinically significant tinnitus: 10-year trend from a cohort study in England. Ear Hear 2015;36:e69–75. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baguley D, McFerran D, Hall D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013;382:1600–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60142-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, et al. A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear Res 2016;337:70–9. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang G-H, et al. Generational differences in the reporting of tinnitus. Ear Hear 2012;33:640–4. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31825069e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elgoyhen AB, Langguth B, De Ridder D, et al. Tinnitus: perspectives from human neuroimaging. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015;16:632–42. 10.1038/nrn4003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shore SE, Roberts LE, Langguth B. Maladaptive plasticity in tinnitus — triggers, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2016;12:150–60. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Langguth B, Elgoyhen AB. Current pharmacological treatments for tinnitus. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:2495–509. 10.1517/14656566.2012.739608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Website Available: www.cochranelibrary.com

- 9. Cima RFF, Maes IH, Joore MA, et al. Specialised treatment based on cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for tinnitus: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1951–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60469-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andersson G, McKenna L. The role of cognition in tinnitus. Acta Otolaryngol 2006;126:39–43. 10.1080/03655230600895226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kröner-Herwig B, Frenzel A, Fritsche G, et al. The management of chronic tinnitus: comparison of an outpatient cognitive-behavioral group training to minimal-contact interventions. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:381–9. 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00400-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zachriat C, Kröner-Herwig B. Treating chronic tinnitus: comparison of cognitive-behavioural and habituation-based treatments. Cogn Behav Ther 2004;33:187–98. 10.1080/16506070410029568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erlandsson SI, Hallberg LR-M. Prediction of quality of life in patients with tinnitus. Br J Audiol 2000;34:11–19. 10.3109/03005364000000114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andersson G, Jüris L, Classon E, et al. Consequences of suppressing thoughts about tinnitus and the effects of cognitive distraction on brain activity in tinnitus patients. Audiol Neurootol 2006;11:301–9. 10.1159/000094460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westin V, Östergren R, Andersson G. The effects of acceptance versus thought suppression for dealing with the intrusiveness of tinnitus. Int J Audiol 2008;47:S112–8. 10.1080/14992020802301688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cima RFF, Crombez G, Vlaeyen JWS. Catastrophizing and fear of tinnitus predict quality of life in patients with chronic tinnitus. Ear Hear 2011;32:634–41. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31821106dd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andersson G, Vretblad P. Anxiety sensitivity in patients with chronic tinnitus. Scand J Occup Ther 2000;29:57–64. 10.1080/028457100750066405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKenna L, Handscomb L, Hoare DJ, et al. A scientific cognitive-behavioral model of tinnitus: novel conceptualizations of tinnitus distress. Front Neurol 2014;5:196 10.3389/fneur.2014.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kleinstäuber M, Jasper K, Schweda I, et al. The role of fear-avoidance cognitions and behaviors in patients with chronic tinnitus. Cogn Behav Ther 2013;42:84–99. 10.1080/16506073.2012.717301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Handscomb LE, Hall DA, Shorter GW, et al. Positive and negative thinking in tinnitus: factor structure of the tinnitus Cognitions questionnaire. Ear Hear 2016;38:126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cima RFF, Dimitri K, Birgit M, et al. Doctors disagree, patients suffer: the case of heterogeneous tinnitus management across Europe, 2016. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maes IHL, Cima RFF, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Tinnitus: a cost study. Ear Hear 2013;34:508–14. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31827d113a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cima RFF, Mazurek B, Haider H, et al. A multidisciplinary European guideline for tinnitus: diagnostics, assessment, and treatment. HNO 2019;10 10.1007/s00106-019-0633-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bosch MC. Organizational determinants of improving health care delivery [Sl: sn] 2009.

- 25. Cima RFF, Haider H. Establishing a standard for tinnitus: patient assessment and characterisation. ENT & Audiology News 2016:71–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Jacobson GP. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol 1998;9:153-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spinhoven PH, Ormel J, Sloekers PPA, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 1997;27:363–70. 10.1017/S0033291796004382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hallam RS. Correlates of sleep disturbance in chronic distressing tinnitus. Scand Audiol 1996;25:263–6. 10.3109/01050399609074965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, et al. The Tinnitus Functional Index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear 2012;33:153–76. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fuller TE, Haider HF, Kikidis D, et al. Different teams, same conclusions? A systematic review of existing clinical guidelines for the assessment and treatment of tinnitus in adults. Front Psychol 2017;8 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Landgrebe M, Azevedo A, Baguley D, et al. Methodological aspects of clinical trials in tinnitus: a proposal for an international standard. J Psychosom Res 2012;73:112–21. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall DA, Haider H, Szczepek AJ, et al. Systematic review of outcome domains and instruments used in clinical trials of tinnitus treatments in adults. Trials 2016;17:270 10.1186/s13063-016-1399-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson BS, Tucci DL, Merson MH, et al. Global hearing health care: new findings and perspectives. Lancet 2017;390:2503–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31073-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029346supp001.pdf (23.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029346supp002.pdf (14.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029346supp003.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029346supp004.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029346supp005.pdf (340.6KB, pdf)