Abstract

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are chronic diseases of unknown cause characterised by a progressive and unpredictable disease course. In the last decade, biological treatment has become a cornerstone in the treatment of IBD. However, one-in-three-to-four patients do not respond to first-line biological agents and another third of patients see their response diminish over time. This highlights an unmet need for optimising the use of biologicals and the prediction of treatment response. Considering the multifaceted nature of IBD, we hypothesise that multiomics profiling of sequential samples from single patients could facilitate the discovery of predictive biomarkers of response to biological therapy and disease course.

Methods

This is a multicentre prospective cohort study which will enrol 840 biological-naïve patients with IBD who initiate biological therapy in a 3-year period. Primary outcomes are the occurrence of primary non-response (evaluated at weeks 14–16) and loss of response (evaluated during entire follow-up in patients who obtain partial or full response after induction period). Each patient will be followed up for their clinical data for at least 1 year or till the end of study period (up to 4 years). Blood and stool samples will be collected sequentially during the first year of biological treatment. Intestinal tissue will be sampled after 1 year of treatment and whenever an endoscopy is performed. Samples will undergo transcriptomic, proteomic and microbial DNA analyses. Omics data will be integrated with clinical data to identify a panel of predictive biomarkers of response to biological therapy and disease behaviour in patients with IBD.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Danish Ethics Committee (H-18064178). Inclusion is ongoing at three study centres and will be initiated in two additional centres. Both positive and negative study results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines, as well as presented at international conferences.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, gastroenterology, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The longitudinal design of the study and collection of sequential samples from single patients allow us to capture biomarker changes associated with critical events during biological treatment.

Integration of clinical data with data obtained from multiple types of biological material enables multiomics analysis for addressing the multifaceted nature of inflammatory bowel diseases.

The long duration of follow-up also increases the likelihood that biomarker changes associated with degenerative changes in the intestines will be detected, which in turn could contribute to the discovery of novel molecular pathways and allow for therapeutic manipulation to halt disease progression.

Missing data are expected in some patients as all samples are collected in relation to routine visits and routine sampling, especially intestinal tissue samples at baseline, are expected to be missing in some patients.

Patient recruitment is limited by the actual rate of initiation of biological therapy in the clinical setting due to the observational design and the duration of follow-up will be limited (to 1 year only) in patients recruited during the last year of inclusion period.

Introduction

The number of people affected by inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) continues to increase globally, affecting up to 0.5% of the population worldwide.1 2 In Denmark alone, the prevalence of IBD in Denmark is estimated to be 52 730 and the incidence of IBD has approached 25.9 per 100 000 person years and is steadily increasing.3 IBD, comprising ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD) and inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU) are complex, immune-mediated diseases characterised by chronic recurring inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Patients are often affected in their early adolescence and present with diarrhoea, abdominal pain and cramps, perianal complications, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, joint pain and weight loss. The unpredictable and progressive disease course of IBD not only impairs the patients’ quality of life, but also constitutes a socioeconomic burden.4 The annual cost of treatment is estimated to be €5.6 billion in Europe alone, which does not account for indirect costs related to sick leave and work disability.5 6

During the last two decades, biological agents have become a cornerstone in the treatment of severe or refractory cases of IBD to induce and maintain remission. Biological agents are molecules targeting inflammatory mediators which have been shown to play a key role in the gut inflammation in IBD and include anti-tumour-necrosis-factor-alpha antibodies, anti-integrin-alpha4-beta7 antibodies, anti-alpha4-integrin antibodies, anti-interleukin 12/23 antibodies and Janus-kinase inhibitors.7 Treatment with biological agents has been shown to effectively decrease the risk of surgery and rate of hospitalisation in patients with IBD.8 In a nationwide cohort study in Denmark, the proportion of patients with CD and UC exposed to biological therapy was 28% and 9%, respectively, and the annual cost of biological therapy was estimated to constitute €1.9 million.9 However, 30%–40% patients do not respond to biologics and an additional 30% of patients experience a diminished response over time.10 11 These patients often undergo several shifts in treatment and are exposed to excessive risk of adverse effects. Since IBD progresses over time, insufficient disease control might lead to irreversible degenerative changes in the intestine and require salvage surgery.12 We are currently unable to identify patients who will experience poor treatment response, hence we are unable to tailor biological treatment to a given patient. Novel, but expensive, IBD treatment options are soon to be introduced and, as such, the need for measures to predict and optimise treatment outcome will only increase.13 14

Recent studies of some of the more than 200 genes associated with IBD have shown how these genes lead in different ways to disruption of intestinal homeostasis and immunological tolerance with subsequent inflammation that is characteristic of IBD.15 16 Previous studies have primarily focused on linking genetic polymorphisms associated with IBD to the response to biological treatment, however, associations are vague and suggest that other omics profiles are also implicated.17 18 Recent findings indicate that mucosal inflammatory patterns and serum cytokine profiles differ between responders and non-responders to biological treatment.19–22 Furthermore, interactions between host and gut microbiota play a pivotal role in IBD pathogenesis and should be taken into consideration when predicting treatment response.23 24 Considering the complex nature of IBD, prediction of treatment response is therefore likely to require the integration of multiple factors including genetic, environmental, microbial and immunological factors into a multiomics model, which on the other hand may explain the pathobiology behind severe IBD phenotypes and intestinal damage.

Here, we present the study protocol for a prospective multicentre cohort study in patients with IBD who are initiating biological treatment for the first time (biological-naïve patients). The Danish IBD Biobank Project aims to identify a panel of predictive biomarkers associated with treatment response and long-term outcomes to biological therapy in biological-naïve patients with IBD.

Aims of the study

Primary objectives of this study are to

Identify microbial, proteomic and transcriptomic predictors of treatment outcomes to biological therapy in biological-naïve patients with IBD.

Identify microbial, proteomic and transcriptomic biomarkers of disease progression and degenerative features of IBD.

Secondary objectives are to

Investigate treatment outcomes for biological treatment in biological-naïve patients with IBD in a real-life setting.

Evaluate adherence to national and international guidelines regarding initiation, follow-up and optimisation of biological therapy.

Methods

Study design

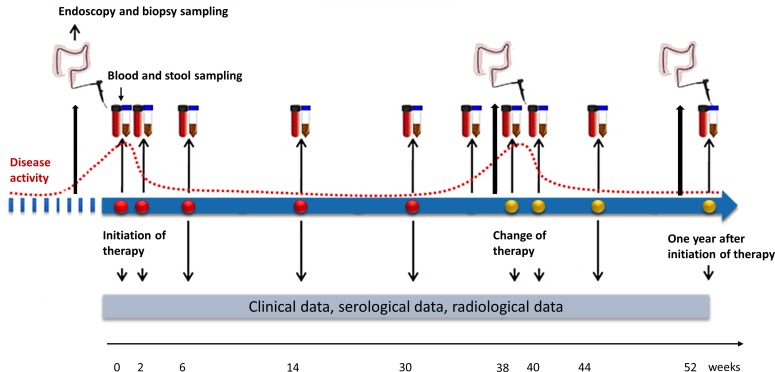

This study is a multicentre, prospective cohort study which will investigate microbial, proteomic and transcriptomic predictors of treatment outcomes to biological therapy in biological-naive patients with IBD. Patient enrolment was initiated in May 2019 and is currently ongoing at four study centres, two additional study centres will initiate enrolment in medio 2020. Enrolment will continue until May 2022. The duration of follow-up of each patient will be at least 1 year from initiation of biological therapy or until May 2023. Clinical data and biological samples will be collected at each study visit during the first year. Study visits are scheduled prior to initiation of biological therapy and subsequently at routine visits for the administration of biological therapy at the outpatient clinic after 0, 2 and 6 weeks of treatment, and subsequently every second or third month. After the first year, clinical data will be updated at least every 6 months until the end of follow-up (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design of the Danish IBD Biobank Project.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the process of refining the research question or the design of this study. In the future, the study aims at involving the Danish patient organisation for patients with IBD (Colitis and Crohn’s Association) in the design of future studies which may arise from the current study.

Setting

The Danish IBD Biobank Project is a collaboration between the departments of gastroenterology at six hospitals including five university hospitals located in four out of five geographic regions in Denmark. These include the departments of gastroenterology at Hvidovre University Hospital, Herlev University Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, Aalborg University Hospital, Odense University Hospital and the Hospital of Soenderjylland. Patients will be recruited from the outpatient clinic or when they are admitted to the hospital prior to the initiation of biological therapy.

Apart from the included departments, the study aims to expand the collaboration with other Danish hospitals in the future.

Study population

Patients are eligible for inclusion if they are (1) diagnosed with IBD (UC, CD and IBDU) according to the Copenhagen diagnostic criteria,25 (2) aged 18 or above and (3) starting treatment with biological therapy due to IBD and have never received treatment with biological agents previously.

Initiation of biological treatment is a clinical decision made by the patient’s physician. Patients will receive biological therapy according to the guidelines and recommendations from the Danish Medicines Council, which include dosing and treatment intervals according to the drug labels. All participating hospitals are advised to follow the National Treatment Guidelines for biological treatment of IBD patients issued by the Medicine Council,7 According to these guidelines, 80% of patients with CD initiating biological treatment due to luminal activity are expected to receive either (1) infliximab, (2) adalimumab or (3) vedolizumab as first-line or second-line treatment, all three drugs and ustekinumab may also be used as third-line or fourth-line treatment. These recommendations also apply to fistulising patients with CD except for the use of vedolizumab which is only approved as third-line or fourth-line treatment. In acutely severe UC, patients in need of ‘rescue’ treatment with biologicals will receive infliximab. In chronic active UC who will initiate biological therapy, 80% are expected to receive (1) infliximab, (2) vedolizumab or (3) golimumab as first-line or second-line treatment, furthermore, tofacitinib may be used as second-line treatment, all above-mentioned drugs and adalimumab may also be used as third-line treatment.7 Furthermore, the study will include patients who initiate treatment with biological agents which might be approved in the future. There are no exclusion criteria in this study.

Outcome measures

Clinical response and primary non-response (PNR) to biological therapy will be evaluated after the end of the induction period, at week 14 for infliximab and vedolizumab, and week 12 for adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab, ustekinumab and tofacitinib. Endoscopic remission will be evaluated 12 months after the start of treatment. In patients who continue biological treatment in a maintenance regime after initially achieving a partial or full response, the proportion of patients with loss of response (LOR) will be registered after 6 and 12 months of biological treatment.

Clinical activity will be assessed using the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI)26 for UC and IBDU patients and the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI)27 for patients with CD. Endoscopic activity will be assessed using the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS)28 in UC and the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD)29 in patients with CD. Radiological activity will be assessed in patients with CD who undergo imaging with MRI or abdominal CT using the Lemann Index, which indicates intestinal damage.30 The Lemann Index will be evaluated at the end of follow-up by a gastroenterologist, in collaboration with a radiologist, at each study centre.

Primary outcomes in this study are as follows:

PNR to treatment: defined as lack of clinical response with induction therapy defined as a decrease in SCCAI of ≥2 points from baseline in patients with UC31; or a decrease in HBI of >3 points from baseline in patients with CD,32 as well as patients who undergo intestinal resection or colectomy due to IBD, or as fistula revision in patients with perianal CD during the period of induction therapy.

LOR to treatment: defined as patients achieving clinical response (as measured by clinical activity indices) during the period of induction therapy, but who later suffer from clinical relapse during maintenance therapy, including the need for rescue therapy with corticosteroids or an alternative biological therapy, or surgery for IBD.

Secondary outcomes in this study are as follows:

Clinical remission to treatment: defined as an SCCAI of ≤2 in patients with UC31; or an HBI of ≤4 in patients with CD.32

Endoscopic remission: defined as a UCEIS of ≤1 in patients with UC28; or an SES-CD of <4 in patients with CD.

Surgery: defined as intestinal resection or colectomy due to disease activity of IBD not responding to medical therapy, or as fistula revision or drainage of abscesses after initiation of biological therapy in patients with perianal CD.

Clinical data

At the time of inclusion, data on patient demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, education, height and body weight), disease characteristics (disease duration, disease phenotype including disease subtype, disease location, disease behaviour and extra-intestinal disease manifestations), medical history, history of surgery, family history of IBD, past and current medications, smoking status (current/former/never user; duration; amount), as well as dietary preferences, will be gathered from the patient’s medical record and by the use of a food frequency questionnaire.

During follow-up, information on clinical disease activity, disease phenotype, current medication, surgery, hospital admission, and development of comorbidity will be updated at each study visit during the first year and every 6 months thereafter. Furthermore, results from endoscopic procedures, imaging procedures, as well as results of routine blood samples (C reactive protein, leucocyte count, albumin, haemoglobin and therapeutic drug monitoring measurements) and faecal-calprotectin will be registered to evaluate mucosal healing and inflammatory burden at each of the aforementioned time points.

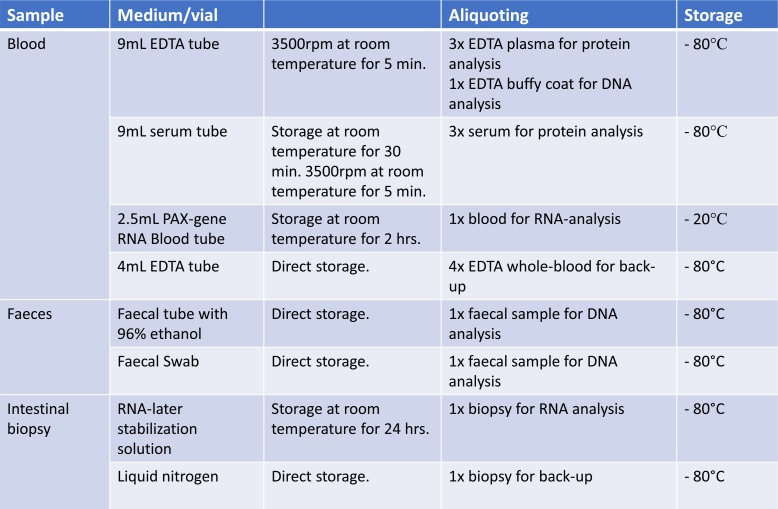

Biological samples

Biological samples of blood, stool and intestinal tissue will be collected prospectively during the first year of follow-up. Blood and stool samples will be collected immediately prior to the initiation of biological therapy and subsequently at each visit for drug administration of biological therapy. On each blood sampling, a 9 mL EDTA tube and a 9 mL serum tube will be collected to yield plasma and buffy coat and serum, respectively. Furthermore, a 2.5 mL PAX-gene Blood Tube will be collected for later transcriptomics analysis. Stool samples will be collected using a faecal sample collection kit preserved with 96% ethanol or using a rectal foam dry swab to be immediately stored at −80°C after sample collection.

Intestinal tissue samples will be collected at each endoscopic procedure that the patient undergoes (unrelated to study participation) during follow-up and at an extra endoscopy after 1 year of follow-up. According to national guidelines, we expect an endoscopy to be performed at baseline, immediately before initiation of biological therapy, on change of treatment, and at least once per year while the patient receives biological treatment. Intestinal tissue samples will be collected from predefined locations: in patients with CD, biopsies will be taken from terminal ileum, ascending and sigmoid colon; in patients with UC, biopsies will be taken from the ascending and sigmoid colon, as well as the rectum. Two samples will be collected from each location, one sample will be treated with RNA-later and handled according to instructions from the product company, while the other sample will be snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. In addition, two samples will be collected from any additional area of inflammation.

All biological samples will be stored at −80°C until they are analysed (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample collection and storage in the Danish IBD Biobank project.

Data management

Clinical data will be collected using an electronic case report form (eCRF) based on the electronic data capture system, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a tool designed to support data capture for research studies.33 REDCap provides validated data entry and audit trails as well as anonymised data import and export. Appointed staff members at each study centre have authorised access to study data, roles in the system are given according to functions and all access to the server and other server maintenances will be logged. Study set-up and hosting are performed by a PhD student at Hvidovre University Hospital. Authorised staff members (one PhD student, one student research assistant, two physicians) can add data to the electronic database and will keep the database current to reflect subject status during the study period. Once the eCRF for a subject is completed, the project personnel at each local centre will approve the data using an electronic signature and thereby confirm the accuracy of the data recorded. Biological samples will be stored at −80°C until analysis of the samples in batch runs. All data will be stored confidentially in locked freezers located in locked rooms which are only accessible to authorised staff.

On study termination, electronic data will be stored for an additional 10 years before deletion. Biological data will be transferred to a biobank for future research hosted at a centrally regulated biobank facility driven by the Capital Region of Denmark, this has been approved by the Data Regulatory Agency and consent from the participants will be sought on recruitment. In order to maintain responsible data sharing and to keep patient data confidentially, data collected in the study will not be shared as an open-access resource; however, researchers are welcome to apply for access to the biobank material for future projects by contacting the steering group of the project. In Denmark, collaboration with external research partners requires separate approval from the Data Regulation Agency and the establishment of a specific data processing agreement; therefore, data sharing with external partners will be decided on a case-by-case basis in the steering group.

Analysis plan

Sample size calculation

Each centre is expected to start biological therapy in 5–6 biological-naïve patients with IBD per month, resulting in a total of 840 patients across 3 years. At least 30% of these are expected to be either PNRs or LORs, corresponding to 252 patients. Biological samples from 200 patients with PNR and LOR and 70 responders will undergo primary analysis. The sample size has been calculated to be able to detect a 1.3-fold upregulation of relevant genes with a common standard deviation (sigma) of one and the desired power of 80% to determine a statistically significant difference (α=0.05, two-sided test). The estimated sample size is 197 subjects in the PNR/LOR group and 66 subjects in the responder group.

Analysis of biological samples

Blood and tissue samples will undergo a transcriptomic analysis. RNA quality will be determined by a Bioanalyzer and RNA integrity numbers will be calculated. RNA and miRNA expression profiles will be determined using microarray and high-throughput parallel sequencing (Illumina) to provide a global gene expression pattern using bioinformatics-based computational methods. Key pathways will be extracted by in silico annotation analysis of the transcriptome data. PCR analysis, Western blotting and immunohistochemistry will subsequently be used to confirm expression patterns of interest. Serum and plasma will undergo characterisation of preselected serum and plasma proteins using inflammation assays.

Stool samples will undergo analysis for microbiota and purification of microbiome DNA will be performed as described by Yan et al.34 Samples will undergo 16S and 18S PCR (examining bacteria, fungi and parasites) and Illumina sequencing and annotation of DNA sequences to species level. Data will thereafter be run in in-house R-scripts, which will identify both quantitative and qualitative differences in microbiota between cohorts.

Statistical analysis

Statistical programming will be carried out using the software R or SPSS Statistics Version 26. Details of the statistical analyses will be provided in the statistical analysis plan, which will be finished before data collection is completed. Comparison of demographics between patient groups will be performed using the χ² test for nominal variables and t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables, according to data distribution. Logistic and Cox regression models will be performed to find potential correlations between baseline characteristics and treatment outcome. Univariate and multivariate hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis will be applied to identify a panel of biomarkers which differentiate between patient groups according to their treatment response. Receiver operator characteristic analyses will be performed to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of single biomarkers and the composite biomarker panel. Biomarkers which are correlated to treatment response will later be assessed in a validation cohort using logistic regression and adjusted for covariates such as age, gender, disease phenotype and concomitant treatment. Statisticians and bio-informaticians will be consulted for their statistical expertise.

Current status

The project has been initiated in May 2019 and is currently ongoing at three study centres. A total of 160 patients have been recruited over a period of 7 months; the current recruitment rate is higher than estimated (105–126 patients). One study centre has initiated recruitment in January 2020 and two other study centres are expected to initiate recruitment in medio 2020.

Discussion and expected limitations

A major strength of this project is its longitudinal design. The building of a biobank with sequential samples from single patients at different time points during biological treatment allows us to observe biomarker changes associated with critical events, including LOR to specific biological agents and disease progression. The extensive collection of data, including clinical data, laboratory data, as well as multiple types of biological material, allows us to perform multiomics analyses that will take into account the complex interplay between host genome and host immune responses on the one hand, and gut microbes and environmental exposures on the other. In this way, we will seek to identify a panel of serological, faecal and mucosal biomarkers which might assist physicians in tailoring biological treatment to the individual patient with IBD. The long duration of follow-up also allows us to study biological patterns which are associated with disease progression in IBD and the development of degenerative changes in the intestines. We thereby hope to facilitate the discovery of molecular pathways which might allow for therapeutic manipulation to halt disease progression in patients with IBD.

The study does have some limitations to address. All tissue samples will be collected as part of routine endoscopies, apart from one supplementary endoscopy scheduled at 1 year after initiation of biological treatment. Despite national guidelines recommending that an endoscopy take place prior to initiation of biological treatment, tissue samples at baseline will inevitably be missing in some patients, since an endoscopy prior to treatment initiation will not be performed in all patients in clinical practice. Similarly, blood and stool samples are collected as part of routine sampling at regular visits, and this might challenge data comprehensiveness in some patients, for instance those lost during follow-up. All study centres also engage in randomised trials with experimental biological agents in patients with IBD, and so we expect some patients to be excluded due to participation in alternative trials; however, this number is expected to be small. At last, the enrolment rate will depend on the number of incident biological users initiating biological therapy in the clinical setting due to the observational study design. However, to date, the rate of enrolment has exceeded the anticipated rate and the enrolment target is evaluated as feasible.

Dissemination of results

Study results will be published according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. Both negative and positive results from the study will be published. Results will be submitted to publication in international peer-reviewed scientific journals and presented at scientific conferences. The national patient organisation for patients with IBDs (the Danish Colitis and Crohn’s Organization) will be involved to help develop the dissemination strategy and to share study results with patients. Patients who participate in the project will be informed by letter of the study results if they express interest in this on study entry. Furthermore, study results and publications will be made public on the project website (www.ibdbiobank.com).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in manuscript conception. MZ is responsible for drafting the manuscript. JB, FB, JBS, LL, AD, CH and AMP are responsible for critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: This study has received support from Takeda Pharma A/S through an unrestricted grant and public funds hosted by the Hvidovre University Hospital. The authors will use private and public funds to cover the cost of sample analyses and materials for sample collection and storage. The funders Takeda Pharma A/S and Hvidovre University Hospital were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: JB reports personal fees from AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, MSD, Pfizer and grants and personal fees from Takeda, all of which were unrelated to this study. FB reports personal fee and grants from Ferring A/S, all of which were unrelated to this study. AMP reports travel grants and fees from MSD and Pfizer, all of which were unrelated to this study. JBS reports research grant from Takeda unrelated to this study, as well as assigned unpaid national coordinator of clinical trials from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Roche and unpaid investigator at studies from Arena and Zealand Pharma. MZ reports travel fees from Takeda Pharma A/S.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The protocol has been approved by the Danish Ethics Committee (H-18064178) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (VD-2019-230). Patients will participate on a voluntary basis and can withdraw from the study at any time. The treatment of patients participating in the study does not differ from that of non-participating patients. All blood samples are to be collected in relation to routine sampling and tissue samples collected in relation to routine endoscopies, other than the single extra endoscopy performed after 1 year of biological treatment that is recommended by national guidelines. Thus, the current study design ensures that study participation is associated with minimal exposure to risk and discomfort and any remaining potential risks are outweighed by the benefits for future patients.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:313–21. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. e42 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lophaven SN, Lynge E, Burisch J. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1980-2013: a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:961–72. 10.1111/apt.13971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ananthakrishnan AN, Weber LR, Knox JF, et al. Permanent work disability in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:154–61. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2013;7:322–37. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Høivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, et al. Work disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients 10 years after disease onset: results from the IBSEN study. Gut 2013;62:368–75. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Board for the Use of Expensive Hospital Medication (Rådet for Dyr Sygehusmedicin) Treatment guidelines for treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases with expensive Hospital medicines. Available: https://rads.dk/media/4366/beh-gastro-31.pdf [Accessed 3 Oct 2019].

- 8. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Oussalah A, Williet N, et al. Impact of azathioprine and tumour necrosis factor antagonists on the need for surgery in newly diagnosed Crohn's disease. Gut 2011;60:930–6. 10.1136/gut.2010.227884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lo B, Vind I, Vester-Andersen MK, et al. Direct and indirect costs of inflammatory bowel disease: ten years of follow-up in a Danish population-based inception cohort. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:53–63. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loftus EV, Colombel J-F, Feagan BG, et al. Long-Term efficacy of Vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis. ECCOJC 2016;9:jjw177 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the accent I randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:1541–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2002;8:244–50. 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White JR, Phillips F, Monaghan T, et al. Review article: novel oral-targeted therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:1610–22. 10.1111/apt.14669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nielsen OH, Seidelin JB, Ainsworth M, et al. Will novel oral formulations change the management of inflammatory bowel disease? Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2016;25:709–18. 10.1517/13543784.2016.1165204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011;474:307–17. 10.1038/nature10209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao M, Burisch J. Impact of genes and the environment on the pathogenesis and disease course of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1759–69. 10.1007/s10620-019-05648-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bek S, Nielsen JV, Bojesen AB, et al. Systematic review: genetic biomarkers associated with anti-TNF treatment response in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:554–67. 10.1111/apt.13736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Souza HSP, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:13–27. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arijs I, Li K, Toedter G, et al. Mucosal gene signatures to predict response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2009;58:1612–9. 10.1136/gut.2009.178665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. West NR, Hegazy AN, Owens BMJ, et al. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Med 2017;23:579–89. 10.1038/nm.4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soendergaard C, Seidelin JB, Steenholdt C, et al. Putative biomarkers of vedolizumab resistance and underlying inflammatory pathways involved in IBD. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2018;5:e000208 10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Y, Soendergaard C, Bergenheim FH, et al. COX-2-PGE2 Signaling Impairs Intestinal Epithelial Regeneration and Associates with TNF Inhibitor Responsiveness in Ulcerative Colitis. EBioMedicine 2018;36:497–507. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ananthakrishnan AN, Luo C, Yajnik V, et al. Gut microbiome function predicts response to Anti-integrin biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe 2017;21:603–10. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McIlroy J, Ianiro G, Mukhopadhya I, et al. Review article: the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease-avenues for microbial management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:26–42. 10.1111/apt.14384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burisch J. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Occurrence, course and prognosis during the first year of disease in a European population-based inception cohort. Dan Med J 2014;61:B4778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43:29–32. 10.1136/gut.43.1.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet 1980;1:514 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Travis SPL, Schnell D, Krzeski P, et al. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology 2013;145:987–95. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daperno M, D'Haens G, Van Assche G, et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:505–12. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)01878-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pariente B, Mary J-Y, Danese S, et al. Development of the Lémann index to assess digestive tract damage in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:52–63. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins PDR, Schwartz M, Mapili J, et al. Patient defined dichotomous end points for remission and clinical improvement in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2005;54:782–8. 10.1136/gut.2004.056358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, et al. Correlation between the Crohn's disease activity and Harvey-Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn's disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:357–63. 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yan M, Pamp SJ, Fukuyama J, et al. Nasal microenvironments and interspecific interactions influence nasal microbiota complexity and S. aureus carriage. Cell Host Microbe 2013;14:631–40. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.