Abstract

Materials that exhibit responsiveness toward biological signals are currently subjected to intense research in the field of drug delivery. In our study, we tried to develop cancer-targeted and redox-responsive nanoparticles (NPs) from disulfide-linked oxidized cysteine-phenylalanine (CFO). The NPs were conjugated with folic acid (FA) to specifically target cancer cells, and the presence of disulfide bonds would enabled the disintegration of the particles in the presence of elevated levels of glutathione (GSH) in cancer cells. Anticancer drug doxorubicin (Dox) was successfully loaded inside the disulfide-linked nanoparticles (CFO-Dox-NPs), which further demonstrated stimuli-responsive drug release in the presence of GSH. We have also demonstrated enhanced uptake of FA-derivatized NPs (FA-CFO-NPs) in cancerous cells (C6 glioma and B16F10 melanoma cells) than in normal cells (HEK293T cells) due to the overexpression of FA receptors on the surface of cancer cells. Cytotoxicity studies in C6 cells and B16F10 cells further revealed enhanced efficacy of Dox loaded (FA-CFO-Dox-NPs) as compared to the native drug. The findings of this study clearly demonstrated that the disulfide-linked nanoparticle system may provide a promising selective drug delivery platform in cancer cells.

Introduction

According to the latest epidemiological data, the number of cancer cases and death rates are increasing day to day. In 2018, approximately 9.6 million cancer-related deaths were reported worldwide, that is, a death rate of ∼1 in 6.1 Cancer carries a high probability of being cured if diagnosed right at the inception and treated effectively.2 Despite tremendous research in the field of cancer therapy, that is, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, still there is a dearth of effective methods to cure cancer. Though research in the field of cancer chemotherapy has drawn continuous attention since the last few decades, it is still suffering from limitations such as fast elimination of the drug molecules, low solubility of most of the chemotherapeutics, and drug resistance.3 As an alternative strategy to conventional methods, nanotechnology has shown tremendous potential in the field of effective cancer therapy.4−6 Current trends in the development of cancer-targeted nanotherapeutics harbor a long list of nanoparticulate systems such as polymeric micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, etc.7 While the incorporation of NP-based therapy has offered interesting continuous progress in cancer therapy, there is skepticism concerning their harmful outcome at the molecular and cellular levels.8 Even polymeric NPs based on polymethyl methacrylate, polystyrene, polyacrylamide, etc. have been reported to educe undesirable toxicity owing to their poor biodegradability.9 Recent advancement shows significant progress in drug delivery applications of peptide-based nanoparticles. Many small and large peptides with designed structures are being used to synthesize different types of nanostructures.10−12 However, short di- or tripeptide-based self-assembled NPs seem to be more encouraging because of their simple structure, ease of synthesis, and excellent biocompatibility as compared to longer peptide-based NPs or polymeric NPs. Therefore, switching over to inherently more biocompatible, more biodegradable NPs comprising of peptides could be a smart choice owing to their superior biocompatibility and reduced toxicity.13,14 These peptide nanostructures can be specifically designed and synthesized with ease through the process of molecular self-assembly, easily functionalized/conjugated with various ligands to specifically target different cell surface receptors to heighten the therapeutic efficacy of entrapped bioactive molecules.15 Several peptide-based self-assembled nanostructures have been explored for their ability to deliver therapeutic molecules into different cancer cells and tissues.16

Though nanoparticulate-based drug delivery systems have importance in actively or passively taking therapeutic molecules to their sites of action by protecting them from systemic degradation along with minimizing nonspecific side effects, just reaching the site of action using a nanocarrier is not enough until the loaded cargo is properly released at the site of action in therapeutically relevant concentrations. Keeping this aspect in mind, continuous progress has been made in developing stimuli-responsive nanoparticles that can disintegrate in response to a particular stimuli17,18 such as pH,19 light,20−22 oxidative reactions,23 reductive reactions of disulfide-thiol chemistry,24,25 etc., conferring site-specific delivery of chemotherapeutic molecules for enhancing drug efficacy and mitigating nonspecific side effects. The difference in redox environments exists between intra- and extracellular milieu and can be elegantly harnessed for achieving site-specific cell-triggered drug delivery, and a lot of efforts are being made in this direction.26,27 Living cells harbor a number of redox processes such as the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+/NADPH) system, oxygen/superoxide (O2/O2·–) system, and the glutathione (GSH/GSSG) system. Since GSH exhibits significantly high intracellular concentrations (1–10 mM) compared to a concentration below 10 μM in extracellular environments, the GSH/GSSG system has gained much interest from researchers working in the area of stimuli-triggered drug delivery. GSH has the ability to trigger thiol–disulfide exchange in polymers containing disulfide bridges, and hence, NPs generated from polymers containing disulfide bridges can be disassembled intracellularly in response to GSH for achieving on-site cargo release.28−30 Several strategies have been reported on the synthesis of amphiphilic block copolymer-based thiol-responsive degradable nanoparticulate systems using the principle of molecular self-assembly. Basically, micelle-like structures were generated from polymers either having a disulfide bond in the middle of polymers31−33 or a disulfide linkage as a side chain. These disulfides were cleaved in the presence of GSH leading to the degradation of micelles and subsequent drug release.34 In the present study, we tried to develop GSH-responsive self-assembled NPs from the oxidized form of the dipeptide cysteine-phenylalanine (CF). Oxidation of the free −SH group leading to the formation of a disulfide linkage between two dipeptide molecules occurred during the dipeptide synthesis using the solution-phase peptide synthesis method. Oxidized cysteine-phenylalanine (CFO) NPs generated after CF–CF covalent linking had two merits: one is that they exhibited GSH-responsive behavior owing to the presence of disulfide linkages, and second, the presence of free amine and carboxylic groups made them amenable to be derivatized with a tumor-targeting ligand like FA. Thus, the NPs had dual advantages of targeted delivery along with site-specific GSH-triggered release of the loaded anticancer drug inside the cancer cells. There are earlier reports highlighting GSH-responsive drug delivery using NPs prepared from large molecules such as homodithiacalix[4]arene (HDT-C4A), those with disulfide bridges,35 [Pt(NH3)2Cl2(OOC(CH2)nCH3)2], or prodrug NPs.36 Cubic gel particles with GSH-triggered drug release prepared by cross-linking of cyclodextrin metal–organic frameworks have also been reported.37 Where all these structures involve complex synthesis procedures, here, in this study, we have synthesized NPs from a simple dipeptide, CF, and explored their property for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. The dipeptidic origin endows the particles with enhanced biocompatibility than that of NPs prepared from large and complex molecules. Moreover, these particles have dual advantages of targeted delivery along with site-specific GSH triggering the release of the loaded anticancer drug inside the cancer cells with a much improved safety profile. Thus, to summarize, we investigated the potential of CFO NPs toward cancer-targeting as well as GSH-triggered, redox-responsive drug release behavior in glioma (C6) and melanoma (B16F10) cells.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of the Dipeptide

CF was synthesized harnessing solution-phase peptide synthesis methods38 and purified using HPLC. The formation of disulfide bonds was confirmed using a mass spectrometer. ESI MS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H31N4O6S2+: 535.16; found: 535.07 (Figures S1 and S2). Further, the CFO peptide was characterized using 1H NMR in CH3OD. Signals of 1H NMR (400 MHz, CH3OD): δ 2.63–2.81 (m, 4H), 3.00–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.16–3.21 (m, 2H), 3.30 (br, 2H), 4.62–4.65 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.45 (m, 10H) were observed (Figure S3).

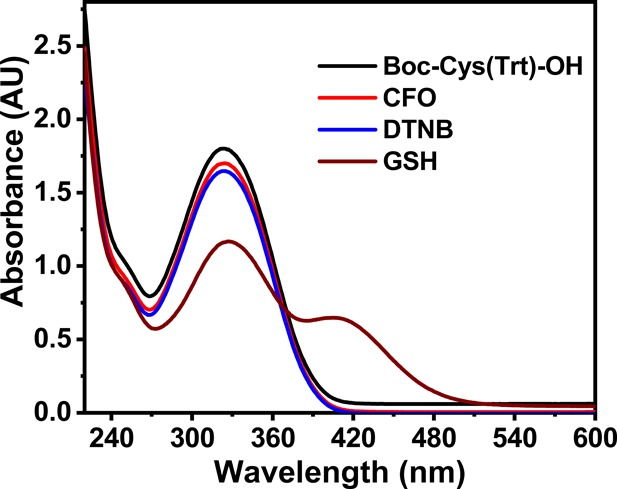

Determination of the Formation of the Disulfide Bond in CFO

One of the most important functions of thiols is the formation of disulfide bonds through an oxidation reaction. We assumed that the dipeptide has undergone oxidation during the process of synthesis. The formation and presence of disulfide bonds in the dipeptide were validated by carrying out Ellman’s test. Ellman’s reagent 5,5′-dithiobis[2-nitrobenzoic acid] (DTNB) is used to determine the presence of sulfhydryl groups in a molecule as it reacts with the sulfhydryl groups to produce a colored product that can be quantified by taking its absorbance at 412 nm.39,40 Ellman’s test was carried out on CFO, which was expected to have a S–S bond after oxidation.

The tripeptide GSH with a free −SH group and Boc-Cys(Trt)-OH with a −SH group attached to a trityl group were used as controls. As expected, tripeptide GSH with a free SH group showed a peak at 412 nm, which was absent in the case of CFO and Boc-Cys(trt)-OH indicating the absence of free SH– groups in the CFO peptide (Figure 1). The formation of the disulfide bond between the dipeptides was further confirmed using mass spectrometry where a corresponding dimer peak was observed (Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Graph showing the Ellman’s test UV–vis spectra of cysteine-containing compounds. A peak at 412 nm indicates the presence of a free −SH group.

The presence of a disulfide bond (S–S) in the CFO peptide was also investigated using Raman and FTIR spectroscopy. Raman spectra of CFO showed a characteristic peak belonging to the disulfide bond at 540 cm–1. As expected, this peak was absent in the GSH peptide, and a new peak at ∼2528 cm–1 was observed (Figure S4).41

Likewise, no absorption peak for free −SH at 2520 cm–1 in the FTIR spectrum was observed for CFO (Figure S5). The FTIR spectrum of the control tripeptide, that is, GSH showed a clear characteristic peak for −SH groups.42 These results clearly indicated the formation of a disulfide bond in the CFO peptide.

Formation of CFO NPs

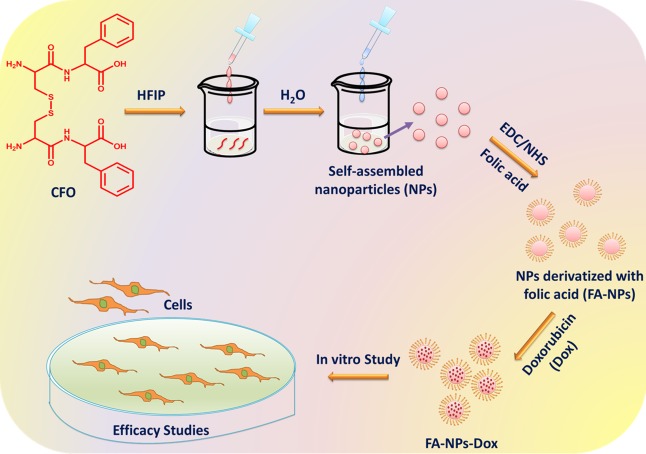

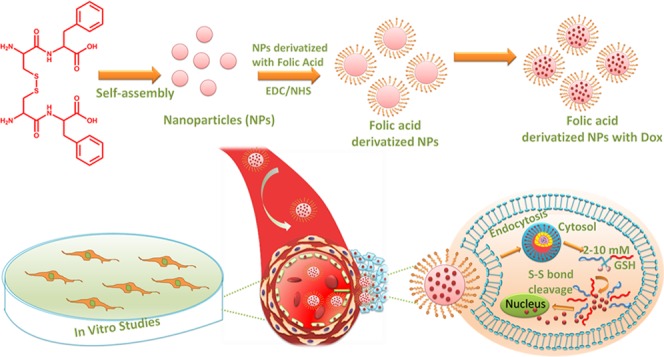

After confirmation of the formation of a disulfide linkage between the peptide, NP formation was achieved by self-assembly of the peptide (CFO) in HFIP and water (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scheme of formation of self-assembled NPs using oxidized Cys-Phe (CFO) and their application in drug delivery.

Characterization of CFO NPs Using Different Techniques

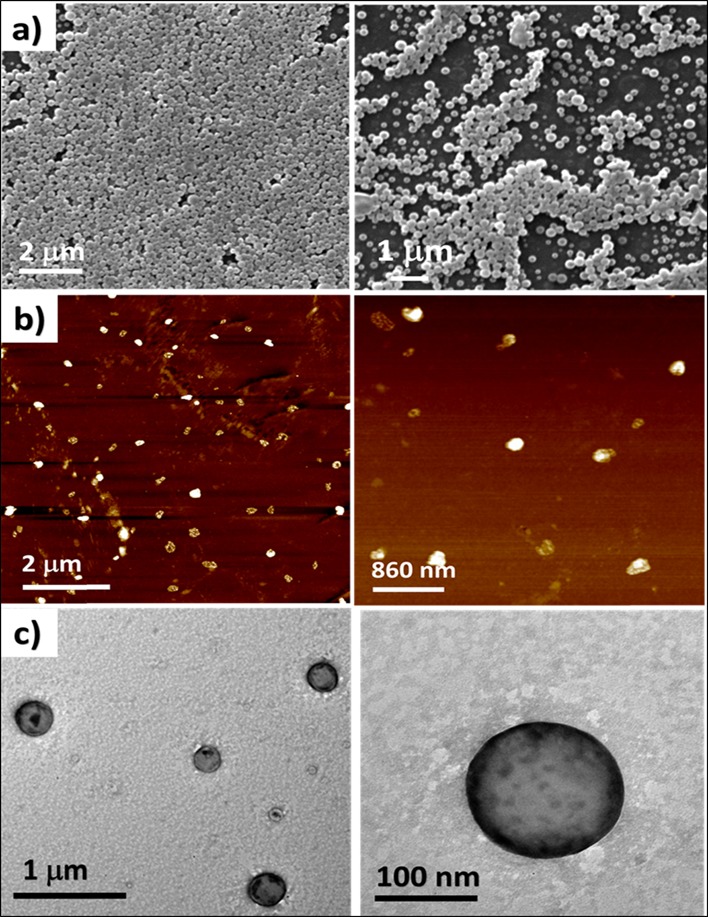

Initial characterization of CFO NPs was carried out using DLS to measure the mean particle size of the NPs and their PDI to check particle homogeneity. Light scattering studies demonstrated the formation of monodispersed particles with a stable size of approximately 220 ± 21 nm and a PDI of 0.1 ± 0.03 after 120 min of incubation at room temperature (Figure S6). SEM analysis was carried out to gain insight into the morphological details of the NPs. Results demonstrated that CFO self-assembled to form spherical NPs with a mean particle size of approximately 201 ± 19 nm (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Morphological analysis of CFO particles carried out using (a) SEM, (b) AFM, and (c) TEM.

Further, CFO NPs were characterized using AFM and TEM (Figure 3b,c), and the results of which supported SEM data by exhibiting the formation of spherical particles.

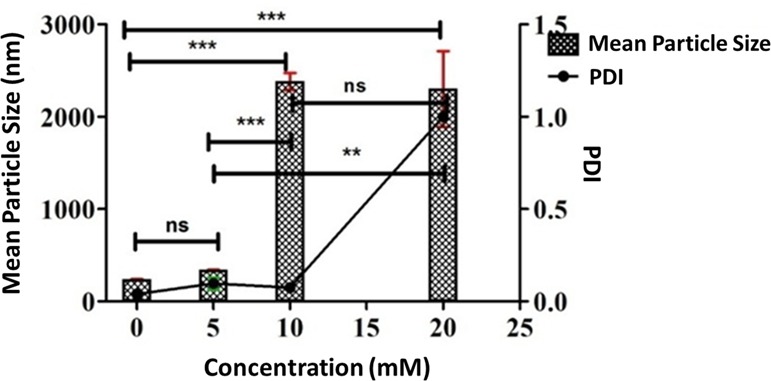

GSH Responsiveness of CFO NPs

DLS study was also carried out to investigate the effect of GSH on the preformed NPs of CFO. Results revealed that there was a significant difference in the mean particle diameter and PDI of the NPs at 0, 5, 10, and 20 mM of the GSH concentration (Figure 4). An increase in particle size and polydispersity was evident as the GSH concentration was increased from 0 to 20 mM, suggesting probable loosening of the tight and discrete particles formed in the absence of GSH.

Figure 4.

DLS data demonstrating the effect of varying concentrations of GSH on the mean particle size and PDI of CFO NPs. ***, **, and * represent levels of significance (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively), and ns represents the nonsignificant difference.

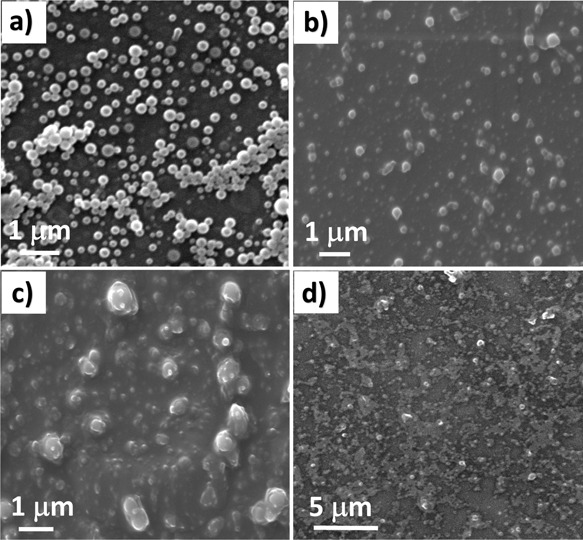

In order to investigate the effect of GSH on the particle surface morphology and polydispersity, SEM analysis was carried out for CFO particles incubated at different GSH concentrations (0, 5, 10, and 20 mM). As shown in Figure 5, CFO NPs were distorted as the concentration of GSH was increased from 0 to 20 mM.

Figure 5.

SEM images of CFO NPs taken at different GSH concentrations: (a) 0, (b) 5, (c) 10, and (d) 20 mM. A significant change in the spherical morphology of the CFO NPs was observed with particle distortion at increasing GSH concentrations after 24 h of incubation.

Drug Encapsulation Study

Spherically shaped NPs can act as excellent platforms for encapsulation of drug molecules. In this study, we had tried to explore the potency of CFO NPs as carriers for the anticancer drug Dox. DLS study demonstrated that the mean hydrodynamic diameter of CFO NPs increased from 220 ± 21 nm to 306 ± 23 nm after being loaded with Dox (Figures S6 and S7). Further, the percentage encapsulation of the drug was found to be almost 78.04% in the spherical particles, which is comparable to the percentage loading obtained for various therapeutic molecules in other dipeptide NPs like isoleucine-dehydrophenylalanine (IΔF) and leucine-dehydrophenylalanine (LΔF) containing the modified amino acid residue α,β,-dehydrophenylalanine. LΔF NPs showed an entrapment efficiency of ∼40% for curcumin, and NPs of IΔF demonstrated an encapsulation efficiency of ∼60% for curcumin.43

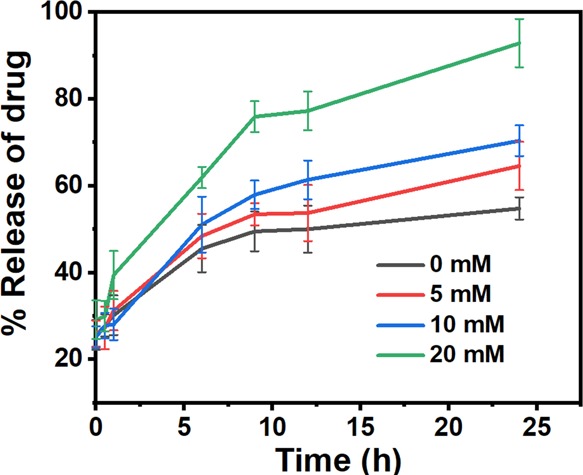

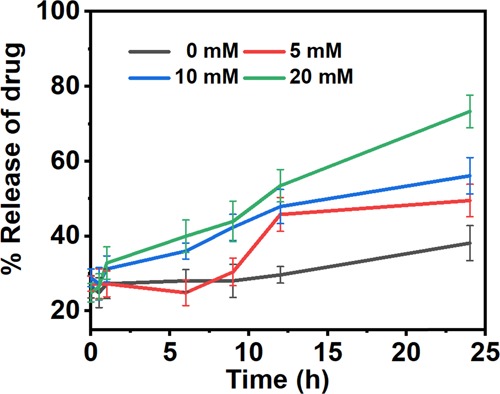

Drug Release at Different GSH Concentrations

The main purpose of the study was to develop redox-responsive CFO nanocarriers that are capable of differentially releasing the encapsulated drug payload in response to varying GSH concentrations. Such a property of any nanomaterial is highly desirable as these could have unprecedented applications in the field of site-specific delivery in cancer cells.44,45 To investigate the release profile of Dox from CFO-Dox-NPs, a drug release study for 24 h was carried out. It was observed that the increase in the GSH concentration led to an enhanced release profile of the anticancer drug from the cysteine-containing dipeptide NPs. The fastest release rate was observed at 20 mM GSH as compared to that at lower GSH concentrations (Figure 6). Similarly, GSH-triggered release of 6-mercaptopurine was also obtained from folic acid-derivatized and GSH-responsive nanoparticles generated from carboxymethyl chitosan.46

Figure 6.

Release profile of Dox from CFO NPs carried out at different GSH concentrations. Data represented as the mean of three (n = 3) independent experiments ± SD. The graph represents the increment in the release rate of Dox with an increase in the GSH concentration.

Derivatization of CFO NPs with FA for Targeted Delivery to Tumor Tissues

FA receptors are overexpressed in many cancer cells. FA is small and inexpensive and has high affinity toward its receptors and has been used as a cancer-targeting ligand in many earlier studies.47 FA was conjugated to CFO NPs using the EDC/NHS conjugation method. After conjugation, the underivatized FA molecules were separated from those conjugated to CFO NPs by centrifuging the sample at 14,000 rpm for 20 min.48 Conjugation efficiency was determined by comparing the amount of free FA present in the supernatant to the number of molecules present in the whole sample before centrifugation and was found to be 95%. Further, the characterization of FA-CFO-NPs was done using DLS, SEM, and AFM.

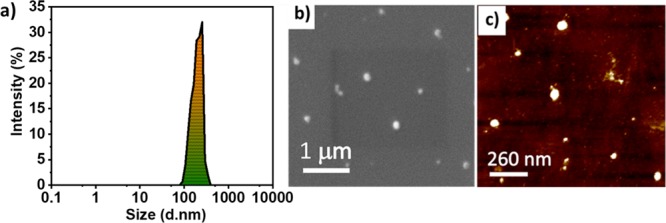

Characterization of FA-CFO-NPs and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs Using DLS, SEM, and AFM

Initial characterization of FA-CFO-NPs was carried out using DLS to measure their mean particle size and their PDI. Light scattering studies demonstrated a mean particle size of approximately 359 ± 18 nm for the FA-CFO-NPs and a PDI of 0.42 ± 0.02 (Figure 7a). A change in the mean particle size of FA-CFO-NPs to 359 ± 18 nm was observed from 220 ± 21 nm for the nonconjugated ones. The observed increase in the particle size of CFO NPs was in line with an earlier study by Wang et al. wherein they derivatized PEG-GEM-NPs with FA and observed an increment in particle size to approximately 184 ± 12 nm from 157 ± 7 nm.49

Figure 7.

Morphological analysis of FA-CFO-NPs carried out using (a) DLS, (b) SEM, and (c) AFM.

Further, the morphological study of FA-CFO-NPs was carried out using SEM (Figure 7b) and AFM (Figure 7c). SEM results demonstrated that FA-CFO-NPs formed spherical NPs with a mean particle size of approximately 261 ± 8 nm. AFM demonstrated the formation of spherical particles with a size of 103 ± 9 nm (Figure 7c). After the characterization of FA-conjugated CFO-NPs, Dox was encapsulated in the FA-CFO-NPs, and the percentage encapsulation of Dox was calculated to be almost 99.14% in the particles. Further, the Dox-loaded FA-CFO-NPs (FA-CFO-Dox-NPs) were then characterized using DLS and SEM (Figure S8). Light scattering studies demonstrated a mean particle size of approximately 365 ± 15 nm (Figure S8a) for the FA-CFO-Dox-NPs and a PDI of 0.22 ± 0.01. Morphological studies of FA-CFO-Dox-NPs were carried out using SEM (Figure S8b). SEM results demonstrated that FA-CFO-NPs formed spherical NPs with a mean particle size of approximately 361 ± 8 nm.

Drug Release of FA-Conjugated CFO-NPs at Different GSH Concentrations

In order to investigate the release profile of Dox from FA-CFO-Dox-NPs, the drug release study was carried out for a period of 24 h. As observed in the case of free CFO nanostructures, FA-CFO-Dox-NPs exhibited an upsurge in the release profile of the anticancer drug with an increase in the GSH concentration. The release rate was substantially higher at 20 mM GSH than that at lower GSH concentrations (Figure 8). Thus, folic acid conjugation did not lead to any variation in the GSH-responsive behavior of the CFO NPs. Such GSH-triggered release behavior of Dox from the NPs along with cancer cell-specific targeting mediated by folic acid would, therefore, ensure high and specific drug delivery only in cancer cells completely sparing healthy cells.50

Figure 8.

Release behavior of Dox from FA-CFO-Dox-NPs carried out at different GSH concentrations. Data represented as the mean of three (n = 3) independent experiments ± SD.

The graph represents an increment in the release rate of the entrapped drug molecule with an increase in the GSH concentration.

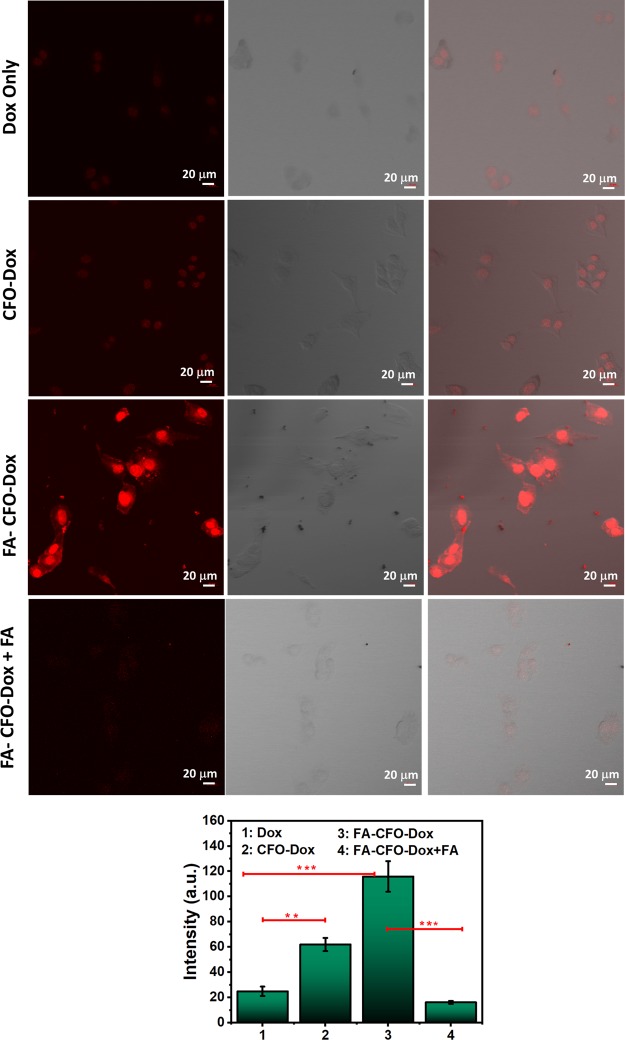

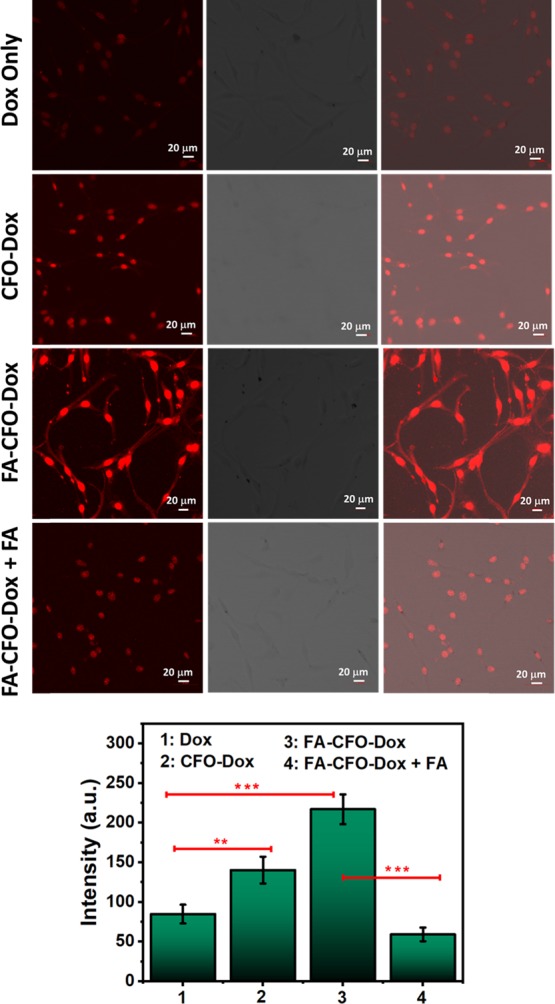

Cellular Uptake of CFO and FA-CFO NPs in C6 and B16F10 Cells

Derivatization of NPs with FA as a targeting ligand is expected to enhance their cellular uptake by facilitating the receptor-mediated endocytosis process.51,52 C6 and B16F10 cell lines were used to carry out the cellular uptake studies. These cells have been shown to express higher levels of FA receptors.53−55 Confocal fluorescence microscopic images demonstrated significantly higher fluorescent intensity in the case of cells treated with Dox-loaded FA-CFO-NPs as compared to CFO-Dox NPs and free Dox (Figure 9), suggesting enhanced particle uptake in C6 cells. Quantitative analysis performed using Image J software also depicted higher fluorescence intensity in the case of cells treated with Dox-loaded FA-CFO-NPs as compared to cells treated with Dox-loaded CFO-NPs. C6 cells treated with Dox-loaded FA-CFO-NPs demonstrated approximately 2.55-fold higher fluorescence intensity, and CFO-Dox exhibited 1.65-fold higher fluorescence intensity as compared to cells treated with free Dox. These results clearly indicated higher cellular uptake of FA-CFO NPs than that of CFO NPs. In order to validate the receptor-targeted uptake by the FA-derivatized nanosystems, cellular uptake efficiency of FA-CFO-Dox-NPs was carried out in a competitive uptake inhibition assay. To do this, C6 cells were incubated with both free FA and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs. Results demonstrated almost 3.55-fold reduction in fluorescence intensity in the case of cells treated with FA-CFO-Dox NPs in the presence of free FA as compared to those treated with FA-CFO-Dox-NPs alone. The observed decrease in cellular uptake in the presence of FA is due to the competitive binding of free FA with FA receptors.

Figure 9.

Cellular uptake of Dox-loaded, FA-conjugated CFO-NPs and nonconjugated CFO-Dox NPs inside C6 cells. Intensity graph results show higher uptake of Dox in the case of FA-conjugated CFO-NPs confirming targeted delivery. ***, **, and * represent levels of significance (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively).

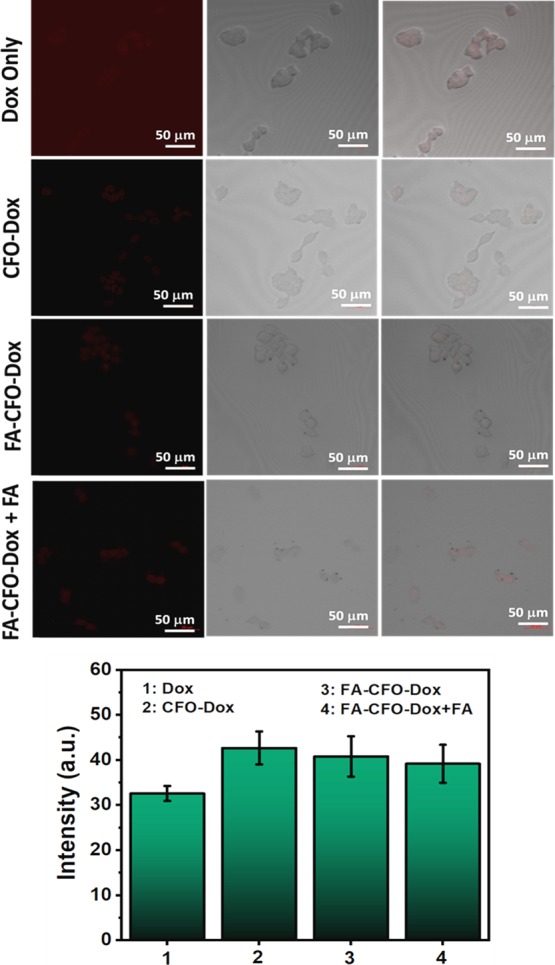

Similar results were obtained in B16F10 cells (Figure 10) where Dox-loaded FA-CFO-Dox-NPs demonstrated almost 1.91-fold higher fluorescence intensity as compared to CFO-Dox and approximately 4.65-fold higher intensity as compared to free Dox. However, when cells were incubated with FA-CFO-Dox NPs in the presence of free FA in a competitive inhibition assay, a 7.16-fold reduction in cellular uptake efficacy was obtained as compared to the cells treated with only FA-CFO-Dox NPs. From the above results, it is clear that the derivatization of CFO NPs with FA significantly enhances the cellular uptake of derivatized NPs suggesting their possible use in targeted delivery applications.38

Figure 10.

Cellular uptake of Dox-loaded, FA-conjugated CFO-NPs and nonconjugated CFO-Dox NPs inside B16F10 cells. Intensity graph results show higher uptake of Dox in the case of FA-conjugated CFO-NPs confirming targeted delivery. ***, **, and * represent levels of significance (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively).

To further confirm the targeting specificity of the FA-conjugated NPs in FA receptor-positive cancer cells, the uptake of FA-conjugated NPs was also determined in HEK293 cells (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Cellular uptake of Dox-loaded, FA-conjugated CFO-NPs and nonconjugated CFO-Dox NPs inside HEK 293 cells (nontumor cells).

Results demonstrated no significant difference in cellular uptake efficiency of FA-CFO-Dox-NPs versus CFO-Dox-NPs in HEK293 cells that are negative for FA (receptor-negative) (nontumor cells). Thus, overall it was observed that FA-CFO-Dox-NPs bound efficiently to FA receptors and delivered the drug more efficiently into FA receptor-positive cancer cells as compared to noncancerous HEK293 cells.

We also performed uptake studies using rhodamine-encapsulated CFO-NPs. Quantitative analysis performed using Image J software also depicted higher fluorescence intensity and hence higher cellular uptake in the case of cells treated with rhodamine loaded in FA-CFO-NPs as compared to those cells treated with rhodamine loaded in CFO-NPs. C6 cells treated with FA-CFO-NPs demonstrated approximately 1.2-fold higher fluorescence intensity as compared to cells treated with CFO-rhodamine and 2.15-fold higher fluorescence intensity in cells treated with free rhodamine (Figure S9). Similar results were obtained in B16F10 cells (Figure S10) where rhodamine-loaded FA-CFO-NPs demonstrated almost 1.82-fold higher cellular fluorescence intensity as compared to CFO-Rhodamine and approximately 2.65-fold higher intensity as compared to free Rhodamine.

In Vitro Efficacy Study Using C6 and B16F10 Cell Lines

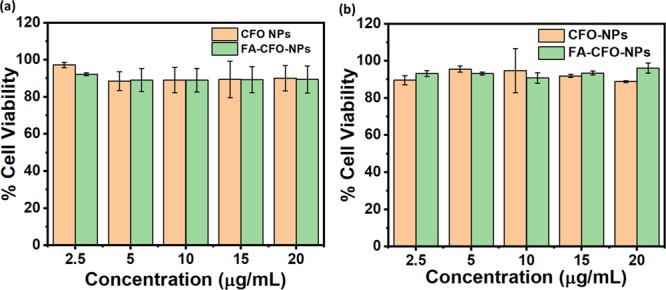

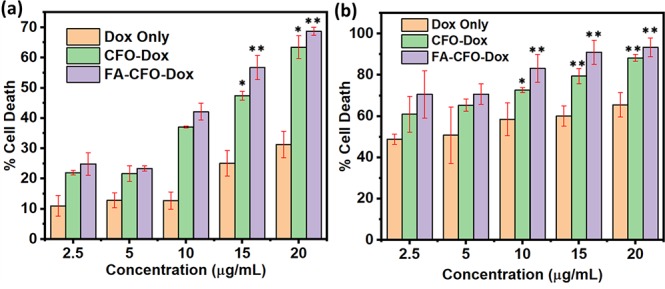

It is always necessary for any NP-based therapy that the cargo molecules entrapped in the NPs must retain their activity. In order to check this, the efficacy of Dox-loaded NPs was determined in cancer cell lines, that is, melanoma cell line (B16F10) and glioma cell line (C6). To begin this, we carried out cytotoxicity experiments using bare NPs in C6 and B16F10 cells, which demonstrated approximately 95–96% cell viability in both cell lines (Figure 12a,b) indicating the biocompatible nature of the particles. Further, cells were incubated with CFO-Dox-NPs, FA-CFO-Dox-NPs, and Dox suspensions (at concentrations of 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 μg/mL) for a period of 24 h, and then cell viability was determined using MTT assay. It was observed that the NPs exhibited an increase in cytotoxicity and the highest killing in the case of FA-CFO Dox-NPs as compared to other groups at all tested concentrations in C6 cells. A similar study was carried out using the B16F10 cell line (Figure 13a), which further supported the efficacy results of the C6 cell line (Figure 13b). Further, IC50 values were calculated to determine the cell-killing efficacy of the formulations.

Figure 12.

Cytotoxicity of bare CFO-NPs and FA-CFO-NPs in (a) C6 cells and (b) B16F10 cells.

Figure 13.

Cytotoxicity of FA-CFO-Dox-NPs, CFO-Dox-NPs, and Dox suspensions toward (a) C6 and (b) B16F10 cells. Data reported as the mean of three (n = 3) independent experiments ± SD. ***, **, and * represents levels of significance (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively).

In C6 cells, free Dox demonstrated an IC50 value of 63.68 μg/mL, CFO-Dox-NPs exhibited an IC50 of 14.74 μg/mL, and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs exhibited an IC50 of 11.57 μg/mL. Thus, FA-CFO-Dox-NPs exhibited significantly (P < 0.001) higher efficacy in the cancer cells in comparison to the native Dox suspension as well as Dox loaded in underivatized NPs. In B16F10 cells, free Dox demonstrated an IC50 value of 3.51 μg/mL, CFO-Dox-NPs exhibited an IC50 of 1.42 μg/mL, and Dox-loaded FA-CFO-NPs exhibited an IC50 of 0.94 μg/mL. The order of cytotoxicity against B16F10 cells in terms of IC50 values revealed that FA-CFO-Dox-NPs had significantly (P < 0.001) higher efficacy in comparison to CFO-Dox-NPs and native Dox suspensions.

Enhanced cytotoxicity of FA-CFO-Dox-NPs could be attributed to their higher cellular uptake owing to their targeted delivery inside cancer cells, which might have resulted in high drug payloads. Further, expected triggered release of the drug in the cytoplasm of these cancer cells (C6 and B16F10) due to the presence of higher GSH concentrations (approximately 2–10 mM) can be an additional factor leading to the observed enhanced efficacy. Similar work by Wei et al. reported enhanced inhibition of human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cells arbitrated by folate-targeted and 6-mercaptopurine-loaded, GSH-responsive carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles.46 On a similar note, Dong and co-workers56 showed GSH-responsive BSA and FA-coupled mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) for the targeted delivery of epirubicin (EPI). They demonstrated specific intracellular uptake of the system in FA receptor-positive HepG2 cells.56

Conclusions

In the present work, we have developed a novel disulfide bond-based NP system through molecular self-assembly of a synthetic CF dipeptide. The CFO NPs generating hereafter a covalently linked S–S bond in CFO possessed two merits: first, they exhibited glutathione-responsive behavior owing to the presence of disulfide linkages, and second, the presence of free −N and −C terminal amine and carboxylic groups endowed them the ability to be derivatized with the well-known tumor-targeting ligand folic acid. Thus, the NPs had dual advantages of being targeted to the cancer cells along with site-specific GSH-triggered release of the loaded anticancer drug Dox, particularly inside the cancer cells enriched with GSH. Evaluation of in vitro cytotoxicity of Dox-NPs showed remarkable cytotoxic effects on B16F10 cells and C6 cells in response to high intracellular reducing potential in these cancerous cells. Cellular uptake and intracellular release profiles of these NPs confirmed that the NPs were taken up effectively and they mainly released the encapsulated payload within cancer cells. Folic acid-derivatized NPs exhibited enhanced cellular uptake in C6 and B16F10 cells (cancer cells) as compared to HEK293 cells (normal and FA receptor-negative cells). Owing to their peptidic origin, the dipeptide NPs reported here offer an added advantage of high biocompatibility. Overall, the folic acid-derivatized and disulfide-based NPs may provide a promising alternative as an anticancer drug-releasing platform for facilitated targeting as well as on-demand drug release-pinpointing cancer chemotherapy with a much improved safety profile, and this study may also pave the path for designing other novel redox-sensitive nanoplatforms for site-directed drug delivery.

Experimental Section

Materials

Chemicals

Boc-Cys(Trt)-OH, l-phenylalanine, N-methyl morpholine, isobutyl chloroformate, sodium hydroxide, tetrahydrofuran, sodium chloride, sodium sulfate, acetic anhydride, sodium acetate, sodium bicarbonate, citric acid, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexa-fluoro-isopropanol (HFIP) were purchased from HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India, and TCI Chemicals. Folic acid, glutathione (GSH) (reduced form), Ellman’s reagent 5,5′-dithiobis[2-nitrobenzoic acid] (DTNB), doxorubicin (HCl), ethyl acetate, methanol, formic acid, trifluoroacetic acid, and dichloromethane were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Munich Germany.

Cell Line and Media

C6 (glioma cell line), B16F10 (murine melanoma cell line), and HEK 293 (human embryonic kidney) cells were procured from the National Centre for Cell Science Pune, India, and further maintained in DMEM medium (Sigma, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HIFBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% (v/v) CO2.

Methodology

Synthesis of the Dipeptide (CF)

The dipeptide was synthesized using solution-phase synthesis methods (Scheme S1).38 The disulfide linkage was automatically formed during the synthesis of the dipeptide, and further oxidation was done by purging O2 into the peptide for ensuring complete oxidation. Further the peptide was characterized out using 1H NMR. The 1H spectrum was recorded on a 400 MHz NMR spectrometers, and CH3OD was used as a solvent. The chemical shifts are reported in parts per million considering the solvent as an internal standard for 3H (δ 5.00 ppm). Signal patterns are indicated as s, singlet; d, doublet; dd, doublet of doublets; t, triplet; m, multiplet; bs, broad singlet; and bm, broad multiplet. Coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz).

Confirmation of the Formation of the Disulfide Bond in Oxidized Cys-Phe (CFO)

First, we carried out Ellman’s test to check the formation of the disulfide bond. Ellman’s reagent, 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), known as DTNB, is a water-soluble compound used for quantifying free sulfhydryl groups in a solution. DTNB reacts with free sulfhydryl groups to generate mixed disulfide and a yellow colored product 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoic acid (NTB), which can be quantified to determine the amount of free sulfhydryl groups. Thus, a sample with a free −SH moiety will exhibit a characteristic UV–vis spectrum with a peak at 412 nm. Therefore, the confirmation of the disulfide bond formation in CFO was determined using Ellman’s reaction. The tripeptide GSH with free −SH was taken as the positive control, and Boc-Cys(Trt)-OH with a −SH group bound to a trityl group was chosen as the negative control. First, DTNB stock (1 M) solution was prepared in 50 mM sodium acetate. The working solution (2 mM DTNB) was prepared using DTNB stock, Tris buffer (pH 8), and distilled water. Test samples were added to 60 μM the working solution. Solutions were mixed properly, and absorbance was taken at 412 nm.39,40

In addition, the formation of the disulfide bond was characterized by Raman spectroscopy and FTIR analysis. A confocal microRaman spectrometer, model HR800 (Horiba Jobin Yvon, Bensheim, Germany), was used to check the disulfide bond formation at room temperature. It uses a 532 nm laser line for the confocal Raman study. Further, FTIR was performed using a Cary Agilent 660 IR spectrophotometer in the range of wavenumber 400–4000 cm–1.

Formation of CFO NPs

The formation of self-assembled NPs was achieved using 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexa-fluoro-isopropanol (HFIP) and distilled water. The dipeptide (1 mg/mL) was first dissolved in HFIP (50 μL) and further diluted with distilled water (1 mL). The resultant particulate suspension was incubated at room temperature for at least 2 h to get a uniform assembly. The NPs were characterized using dynamic light scattering (DLS), atomic force microscopy (AFM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Characterization of the NPs was carried out at a peptide concentration of 1.86 mM (1 mg/mL).

Characterization of CFO-NPs Using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Particles were formed as mentioned above and their polydispersity index (PDI) and mean particle size was determined by using a DLS instrument (Zetasizer Nano ZSP; Model ZEN5600; Malvern Instrument Ltd., Worcestershire, U.K.). The responsiveness of the NPs toward different concentrations of GSH was also determined using DLS studies.

Characterization of CFO-NPs Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the amino acid-based nanostructures was determined by using SEM. Samples for SEM analysis were prepared by drop-casting them on silicon wafers followed by air-drying. The air-dried samples were gold-coated for 90 s in an auto fine coater (JEOL JEC-3000FC). SEM analysis was further carried out to determine the effect of different GSH concentrations on the NPs.

Characterization of CFO-NPs Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

AFM-based studies of the particles were carried out using tapping-mode atomic force microscopy using Bruker Nanoscope-V AFM having optimum scanning frequency of approximately 1 Hz and with several pixels of approximately 512. A cantilever with a length of 196 μm was used for the study; the spring constant was chosen to be 0.06 (N·m)−1 to determine the surface morphology and roughness of the self-assembled structures. Samples prepared through self-assembly were drop-cast on a silicon chip and air-dried before imaging.

Characterization of CFO-NPs Using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Further TEM-based studies were carried out with JEOL TEM 2100 with a tungsten filament at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. This study was carried out to determine the morphology of particles. Particles prepared through self-assembly were suitably diluted with Milli Q water and then drop cast on carbon-coated copper grids having a mesh size of 200 nm and subsequently stained with uranyl acetate (2% w/v) for imaging.

Drug Encapsulation Study

For drug encapsulation, the anticancer drug Dox was added to preformed NPs in an equal weight ratio and further incubated for 48 h at room temperature with constant shaking. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min to separate the unentrapped drug molecules. The concentration of the free drug in the supernatant was quantified using UV–visible spectroscopy at 480 nm. The drug encapsulation percentage was calculated by using the following formula:

Percentage encapsulation = (Initial absorbance of the drug solution – absorbance of the filtrate)/Initial absorbance of the drug solution) × 100

Effect of GSH on the Pattern of Dox Release from Dox-Loaded CFO NPs (CFO-Dox-NPs)

Drug release studies were performed using the dialysis bag method in dissolution solvent. Release behavior of Dox from the NPs was monitored at different GSH concentrations (0, 5, 10, and 20 mM) using a dialysis bag method (MWCO:12KDa). Samples were kept under gentle stirring in the dissolution media at 37 °C. At predetermined time intervals (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h), 1 mL of the released solutions was taken out for testing and replenished with the equivalent volume of the dissolution solvent. Drug release kinetics was determined by sampling out 1 mL of the dissolution medium at different time intervals (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h), and absorbance was measured at 480 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan).

Synthesis of NPs Derivatized with FA

NPs were prepared as per the required amount and then conjugated with FA using 1-ethyl-3-EDC:NHS. Using this method, the carboxylic group of FA (10 mM) was activated with EDC:NHS (10 mM) and then incubated with NPs (1 mg/mL) at room temperature for 18 h. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min, and then the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of distilled water. Conjugation efficiency of FA with CFO-NPs was analyzed by measuring the difference between the initial concentration of FA in the nanoformulation, and the amount of FA remained attached to the CFO-NPs after being centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min.

Characterization of FA-CFO-NPs and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs Using DLS, SEM, and AFM

The initial characterization study of FA-CFO-NPs and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs was done using DLS to measure their mean particle diameter and PDI. Further morphology of the NPs was determined by using JEOL SEM and Bruker Nanoscope-V AFM.

Cellular Uptake Study in C6, B16F10, and HEK 293 Cell Lines Using Confocal Microscopy

Cellular uptake studies of FA-conjugated (FA-CFO-Dox-NPs) and nonconjugated NPs (CFO-Dox) loaded with Dox were carried out in C6, B16F10, and HEK 293 cell lines. Inherent fluorescence of Dox was used to visualize the cells in confocal microscopy. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator up to 80% confluency. Cells were then treated with 50 μg/mL each formulation, that is, free Dox, CFO-Dox-NPs, FA-CFO-Dox-NPs, and FA-CFO-Dox-NPs in the presence of excess FA (FA-CFO-Dox-NPs + FA) (1 mM), for a period of 24 h in order to determine competitive inhibition by free FA. After the incubation period was over, confocal microscopic images were acquired in the red channel using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 880).

Further, cellular uptake studies of rhodamine-loaded FA-conjugated NPs (FA-CFO-rhodamine) and nonconjugated NPs (CFO-rhodamine) was also carried out in C6 and B16F10 cell lines as mentioned above.

Efficacy Studies of FA-Conjugated CFO-Dox-NPs in C6 and B16F10 Cell Lines

Cells were plated (2 × 104 cells/well) in triplicate in 96-well sterile microtiter plates and grown for 24 h allowing proper cell adhesion. Cells were then treated with free Dox molecules, Dox loaded in CFO-NPs (CFO-Dox-NPs), Dox loaded in FA-CFO NPs (FA-CFO-Dox-NPs), and void NPs and were incubated for a period of 24 h. Cells were also treated with phosphate-buffered saline as control. After an incubation period of 24 h, the media was removed and replaced with 180 μL of fresh growth medium. Then, subsequently, 20 μL of MTT(5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to every well. The plate was additionally incubated for a period of 4 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After completion of the incubation period, media was removed and 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals, and absorbance was taken at 572 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Mean ± standard deviation or mean ± standard error of the mean was calculated to express the data. A T-test was used for drawing the comparison between different groups. Differences between the mean values of five subgroups were compared by one-way analysis of variance. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. ***, **, and * represent levels of significance (P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively).

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the Bio-CARe Programme from Department of Biotechnology, India, and Inspire Faculty Fellowship program of Department of Science and Technology, India, for support. The help from Ms. Taru Dube in carrying out SEM-based analysis is also acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03547.

Purity of the synthesized peptide checked by HPLC and mass spectrometry and further characterization of the formation of disulfide bond using NMR, FTIR, and Raman spectroscopy (PDF)

This work was supported by the Government of India, Ministry of Science and Technology, Department of Biotechnology, India (no. BT/PR17945/BIC/101/563/2016).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bray F.; Ferlay J.; Soerjomataram I.; Siegel R. L.; Torre L. A.; Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loud J. T.; Murphy J. Cancer screening and early detection in the 21st century. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 33, 121–128. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H.; Khatami M. Analyses of repeated failures in cancer therapy for solid tumors: poor tumor-selective drug delivery, low therapeutic efficacy and unsustainable costs. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 11. 10.1186/s40169-018-0185-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. Y. S.; Rutka J. T.; Chan W. C. W. Nanomedicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2434–2443. 10.1056/NEJMra0912273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer D.; Karp J. M.; Hong S.; Farokhzad O. C.; Margalit R.; Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 751–760. 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Gu F. X.; Chan J. M.; Wang A. Z.; Langer R. S.; Farokhzad O. C. Nanoparticles in Medicine: Therapeutic Applications and Developments. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 83, 761–769. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna V.; Pala N.; Sechi M. Targeted therapy using nanotechnology: focus on cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 467–483. 10.2147/IJN.S36654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdary M.; Moosavi M.; Rahmati M.; Falahati M.; Mahboubi M.; Mandegary A.; Jangjoo S.; Mohammadinejad R.; Varma R. Health Concerns of Various Nanoparticles: A Review of Their in Vitro and in Vivo Toxicity. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 634. 10.3390/nano8090634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsabahy M.; Wooley K. L. Design of polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical delivery applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2545–2561. 10.1039/c2cs15327k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesan S.; Vargiu A.; Styan K. The Phe-Phe motif for peptide self-assembly in nanomedicine. Molecules 2015, 20, 19775–19788. 10.3390/molecules201119658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potekhin S. A.; Melnik T. N.; Popov V.; Lanina N. F.; Vazina A. A.; Rigler P.; Verdini A. S.; Corradin G.; Kajava A. V. De novo design of fibrils made of short α-helical coiled coil peptides. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 1025–1032. 10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon L.; Lepeltier E.; Passirani C. Self-assembly of peptide-based nanostructures: Synthesis and biological activity. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 2315–2335. 10.1007/s12274-017-1892-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra J.; Panda J. J. Short peptide-based smart targeted cancer nanotherapeutics: a glimmer of hope. Ther. Delivery 2019, 10, 135–138. 10.4155/tde-2019-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda J. J.; Chauhan V. S. Short peptide based self-assembled nanostructures: implications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Polym. Chem 2014, 5, 4418. 10.1039/C4PY00173G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tesauro D.; Accardo A.; Diaferia C.; Milano V.; Gullion J.; Ronga L.; Rossi F. Peptide-Based Drug-Delivery Systems in Biotechnological Applications: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Molecules 2019, 24, 351. 10.3390/molecules24020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T.; Yu X.; Shen B.; Sun L. Peptide Self-Assembled Nanostructures for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Nanomater. 2017, 4562474. 10.1155/2017/4562474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Xu H.; Zhang X. Tuning the Amphiphilicity of Building Blocks: Controlled Self-Assembly and Disassembly for Functional Supramolecular Materials. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2849–2864. 10.1002/adma.200803276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. W.; Fulton D. A. Making polymeric nanoparticles stimuli-responsive with dynamic covalent bonds. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 31. 10.1039/C2PY20727C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies E. R.; Fréchet J. M. J. A new approach towards acid sensitive copolymer micelles for drug Delivery. Chem. Commun. 2003, 1640–1641. 10.1039/B304251K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Dong R.; Zu X.; Yan D. Photo-responsive polymeric micelles. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 6121. 10.1039/C4SM00871E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Light-Responsive Block Copolymer Micelles. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 3647–3657. 10.1021/ma300094t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand O.; Gohy J. F. Photo-responsive polymers: synthesis and Applications. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 52. 10.1039/C6PY01082B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N.; Li Y.; Xu H.; Wang Z.; Zhang X. Dual Redox Responsive Assemblies Formed from Diselenide Block Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 442–443. 10.1021/ja908124g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Madsen J.; Armes S. P.; Lewis A. L. A New Class of Biochemically Degradable, Stimulus-Responsive Triblock Copolymer Gelators. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 118, 3590–3593. 10.1002/ange.200600324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsarevsky N. V.; Matyjaszewski K. Reversible Redox Cleavage/Coupling of Polystyrene with Disulfide or Thiol Groups Prepared by Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9009–9014. 10.1021/ma021061f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi-Barr S.; de Gracia Lux C.; Mahmoud E.; Almutairi A. Exploiting Oxidative Microenvironments in the Body as Triggers for Drug Delivery Systems. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2014, 21, 730. 10.1089/ars.2013.5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F.; Hennink W. E.; Zhong Z. Reduction-sensitive polymers and bioconjugates for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2180–2198. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J. F.; Whittaker M. R.; Davis T. P. Glutathione responsive polymers and their application in drug delivery systems. Polym. Chem 2017, 8, 97. 10.1039/C6PY01365A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russo A.; DeGraff W.; Friedman N.; Mitchell J. B. Selective Modulation of Glutathione Levels in Human Normal versus Tumor Cells and Subsequent Differential Response to Chemotherapy Drugs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 2845–2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito G.; Swanson J. A.; Lee K.-D. Drug delivery strategy utilizing conjugation via reversible disulfide linkages: role and site of cellular reducing activities. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2003, 55, 199–215. 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Liu W.; Dong C. M. Bioreducible micelles and hydrogels with tunable properties from multi-armed biodegradable copolymers. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11282–11284. 10.1039/c1cc14663g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham A.; Oh J. K. New Design of Thiol-Responsive Degradable Polylactide-Based Block Copolymer Micelles. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013, 34, 163–168. 10.1002/marc.201200532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J. H.; Roy R.; Ventura J.; Thayumanavan S. Redox-Sensitive Disassembly of Amphiphilic Copolymer Based Micelles. Langmuir 2010, 26, 7086–7092. 10.1021/la904437u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L.; Liu J.; Wen J.; Zhao H. Self-Assembly of a Diblock Copolymer with Pendant Disulfide Bonds and Chromophore Groups: A New Platform for Fast Release. Langmuir 2012, 28, 11232–11240. 10.1021/la3020817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q.; Yin H.; Sun C.; Yui L.; Ding Y.; Dehaen W.; Wang R. Glutathione-responsive homodithiacalix[4]arene-based nanoparticles for selective intracellular drug delivery. Chem. Commun. 2018, 8128–8131. 10.1039/C8CC05031G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X.; Tu J.; Wang J.; Shajii A.; Kong N.; Feng C.; Zhang Y.; Yu M.; Xie T.; Bharwani Z.; Aljaeid B. M.; Shi B.; Tao W.; Farokhzad O. C. Glutathione-Responsive Prodrug Nanoparticles for Effective Drug Delivery and Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 357–370. 10.1021/acsnano.8b06400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Q.; Ye C.; Zhang M.; Hu X.; Cai T. Glutathione responsive cubic gel particles cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks for intracellular drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 551, 39–46. 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda J. J.; Kaul A.; Kumar S.; Alam S.; Mishra A. K.; Kundu G. C.; Chauhan V. S. Modified dipeptide-based nanoparticles: vehicles for targeted tumor drug delivery. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1927–1942. 10.2217/nnm.12.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robyt J. F.; Ackerman R. J.; Chittenden C. G. Reaction of protein disulfide groups with Ellman’s reagent: A case study of the number of sulfhydryl and disulfide groups in Aspergillus oryzae α-amylase, papain, and lysozyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971, 147, 262–269. 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther J. R.; Thorpe C. Quantification of Thiols and Disulfides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 838–846. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H.; Wang Y.; Wang M.; Liu S.; Yu F.; Gao C.; Li G.; Wu Q. Construction of a Glutathione-Responsive and Silica-Based Nanocomposite for Controlled Release of Chelator Dimercaptosuccinic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3790. 10.3390/ijms19123790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko D.; Lee J. S.; Patel H. A.; Jakobsen M. H.; Hwang Y.; Yavuz C. T.; Hansen H. C. B.; Andersen H. R. Selective removal of heavy metal ions by disulfide linked polymer networks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 332, 140–148. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S.; Panda J. J.; Chauhan V. S. Novel dipeptide nanoparticles for effective curcumin delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 4207. 10.2147/IJN.S33015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.; Feng F.; Meng F.; Deng C.; Feijen J.; Zhong Z. Glutathione-responsive nano-vehicles as a promising platform for targeted intracellular drug and gene delivery. J. Controlled Release 2011, 152, 2–12. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Tang F.; Zhang J.; Lee S. M. Y.; Wang R. Glutathione-responsive nanoparticles based on a sodium alginate derivative for selective release of doxorubicin in tumor cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 2337. 10.1039/C6TB03032G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X.; Liao J.; Davoudi Z.; Zheng H.; Chen J.; Li D.; Xiong X.; Yin Y.; Yu X.; Xiong J.; Wang Q. Folate Receptor-Targeted and GSH-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles Containing Covalently Entrapped 6-Mercaptopurine for Enhanced Intracellular Drug Delivery in Leukemia. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 439. 10.3390/md16110439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Murthy N. Targeted delivery of catalase and superoxide dismutase to macrophages using folate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 360, 275–279. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonekar S.; Mishra M. K.; Patel A. K.; Nair S. K.; Singh C. S.; Singh A. K. Formulation and evaluation of folic acid conjugated gliadin nanoparticles of curcumin for targeting colon cancer cells. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 068–074. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Wang Y.; Ma Q.; Cao Y.; Yu B. Development and characterization of folic acidconjugated chitosan nanoparticles for targeted and controlled delivery of gemcitabinein lung cancer therapeutics. Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1530–1538. 10.1080/21691401.2016.1260578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lale S. V.; Kumar A.; Prasad S.; Bharti A. C.; Koul V. Folic Acid and Trastuzumab Functionalized Redox Responsive Polymersomes for Intracellular Doxorubicin Delivery in Breast Cancer. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1736–1752. 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gref R.; Couvreur P.; Barratt G.; Mysiakine E. Surface-engineered nanoparticles for multiple ligand coupling. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4529–4537. 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00348-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S. K.; Ma W.; Labhasetwar V. Efficacy of transferrin-conjugated paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles in a murine model of prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 112, 335–340. 10.1002/ijc.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N.; Shao C.; Qu Y.; Li S.; Gu W.; Zheng T.; Ye L.; Yu C. Folic Acid-Conjugated MnO Nanoparticles as a T1 Contrast Agent for Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Tiny Brain Gliomas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 19850–19857. 10.1021/am505223t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Meng Y.; Li C.; Qian M.; Huang R. Receptor-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems Targeting to Glioma. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 3. 10.3390/nano6010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Tezcan O.; Li D.; Beztsinna N.; Lou B.; Etrych T.; Ulbrich K.; Metselaar J. M.; Lammers T.; Hennink W. E. Overcoming multidrug resistance using folate receptor-targeted and pH-responsive polymeric nanogels containing covalently entrapped doxorubicin. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10404–10419. 10.1039/C7NR03592F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Xing Y.; Xian M.; Shuanga S.; Dong C. Folate-targeting and bovine serum albumin-gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a redox responsive carrier for epirubicin release. New J. Chem 2019, 43, 2694. 10.1039/C8NJ05476B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.