Abstract

Background

Oral 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) preparations were intended to avoid the adverse effects of sulfasalazine (SASP) while maintaining its therapeutic benefits. Previously, it was found that 5‐ASA drugs in doses of at least 2 g/day, were more effective than placebo but no more effective than SASP for inducing remission in ulcerative colitis. This updated review includes more recent studies and evaluates the efficacy and safety of 5‐ASA preparations used for the treatment of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to assess the efficacy, dose‐responsiveness and safety of oral 5‐ASA compared to placebo, SASP, or 5‐ASA comparators for induction of remission in active ulcerative colitis. A secondary objective of this systematic review was to compare the efficacy and safety of once daily dosing of oral 5‐ASA with conventional (two or three times daily) dosing regimens.

Search methods

A computer‐assisted literature search for relevant studies (inception to July 9, 2015) was performed using MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library. Review articles and conference proceedings were also searched to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

Studies were accepted for analysis if they were randomized controlled clinical trials of parallel design, with a minimum treatment duration of four weeks. Studies of oral 5‐ASA therapy for treatment of patients with active ulcerative colitis compared with placebo, SASP or other formulations of 5‐ASA were considered for inclusion. Studies that compared once daily 5‐ASA treatment with conventional dosing of 5‐ASA (two or three times daily) and 5‐ASA dose ranging studies were also considered for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

The outcomes of interest were the failure to induce global/clinical remission, global/clinical improvement, endoscopic remission, endoscopic improvement, adherence, adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, and withdrawals or exclusions after entry. Trials were separated into five comparison groups: 5‐ASA versus placebo, 5‐ASA versus sulfasalazine, once daily dosing versus conventional dosing, 5‐ASA versus comparator 5‐ASA, and 5‐ASA dose‐ranging. Placebo‐controlled trials were subgrouped by dosage. SASP‐controlled trials were subgrouped by 5‐ASA/SASP mass ratios. Once daily versus conventional dosing studies were subgrouped by formulation. 5‐ASA‐controlled trials were subgrouped by common 5‐ASA comparators (e.g. Asacol, Claversal, Salofalk and Pentasa). Dose‐ranging studies were subgrouped by 5‐ASA formulation. We calculated the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for each outcome. Data were analyzed on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

Main results

Fifty‐three studies (8548 patients) were included. The majority of included studies were rated as low risk of bias. 5‐ASA was significantly superior to placebo with regard to all measured outcome variables. Seventy‐one per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to enter clinical remission compared to 83% of placebo patients (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.89). A dose‐response trend for 5‐ASA was also observed. No statistically significant differences in efficacy were found between 5‐ASA and SASP. Fifty‐four per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to enter remission compared to 58% of SASP patients (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.04). No statistically significant differences in efficacy or adherence were found between once daily and conventionally dosed 5‐ASA. Forty‐five per cent of once daily patients failed to enter clinical remission compared to 48% of conventionally dosed patients (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.07). Eight per cent of patients dosed once daily failed to adhere to their medication regimen compared to 6% of conventionally dosed patients (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.64 to 2.86). There does not appear to be any difference in efficacy among the various 5‐ASA formulations. Fifty per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group failed to enter remission compared to 52% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.02). A pooled analysis of 3 studies (n = 1459 patients) studies found no statistically significant difference in clinical improvement between Asacol 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day used for the treatment of moderately active ulcerative colitis. Thirty‐seven per cent of patients in the 4.8 g/day group failed to improve clinically compared to 41% of patients in the 2.4 g/day group (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.01). Subgroup analysis indicated that patients with moderate disease may benefit from the higher dose of 4.8 g/day. One study compared (n = 123 patients) Pentasa 4 g/day to 2.25 g/day in patients with moderate disease. Twenty‐five per cent of patients in the 4 g/day group failed to improve clinically compared to 57% of patients in the 2.25 g/day group (RR 0.44; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.71). A pooled analysis of two studies comparing MMX mesalamine 4.8 g/day to 2.4 g/day found no statistically significant difference in efficacy (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.29). There were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of adverse events between 5‐ASA and placebo, once daily and conventionally dosed 5‐ASA, 5‐ASA and comparator 5‐ASA formulation and 5‐ASA dose ranging (high dose versus low dose) studies. Common adverse events included flatulence, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, headache and worsening ulcerative colitis. SASP was not as well tolerated as 5‐ASA. Twenty‐nine percent of SASP patients experienced an adverse event compared to 15% of 5‐ASA patients (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.63).

Authors' conclusions

5‐ASA was superior to placebo and no more effective than SASP. Considering their relative costs, a clinical advantage to using oral 5‐ASA in place of SASP appears unlikely. 5‐ASA dosed once daily appears to be as efficacious and safe as conventionally dosed 5‐ASA. Adherence does not appear to be enhanced by once daily dosing in the clinical trial setting. It is unknown if once daily dosing of 5‐ASA improves adherence in a community‐based setting. There do not appear to be any differences in efficacy or safety among the various 5‐ASA formulations. A daily dosage of 2.4 g appears to be a safe and effective induction therapy for patients with mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Patients with moderate disease may benefit from an initial dose of 4.8 g/day.

Plain language summary

Oral 5‐aminosalicylic acid for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis

Sulfasalazine (SASP) has been used for treating ulcerative colitis for decades. SASP is made up of 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) linked to a sulfur molecule. Up to a third of patients treated with SASP have reported side effects, which are thought to be related to the sulfur part of the molecule. Common side effects associated with SASP include nausea, indigestion, headache, vomiting and abdominal pain. 5‐ASA drugs were developed to avoid the side effects associated with SASP. This review includes 53 randomized trials with a total of 8548 participants. Oral 5‐ASA was found to be more effective than placebo (fake drug). Although oral 5‐ASA drugs are effective for treating active ulcerative colitis, they are no more effective than SASP therapy. Patients taking 5‐ASA are less likely to experience side effects than patients taking SASP. Side effects associated with 5‐ASA are generally mild in nature, and common side effects include gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. flatulence, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea), headache and worsening ulcerative colitis. Male infertility is associated with SASP and not with 5‐ASA, so 5‐ASA may be preferred for patients concerned about fertility. 5‐ASA compounds are more expensive than SASP, so SASP may be the preferred option where cost is an important factor. 5‐ASA dosed once daily appears to be as effective and safe as conventionally dosed (two or three times daily) 5‐ASA. There do not appear to be any differences in effectiveness or safety among the various 5‐ASA formulations. A daily dosage of 2.4 g appears to be a safe and effective therapy for patients with mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Patients with moderate disease may benefit from an initial dose of 4.8 g/day.

Summary of findings

Background

The successful management of ulcerative colitis was greatly facilitated after the introduction of sulfasalazine (SASP) by Svartz (Svartz 1942). SASP is composed of 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) linked to sulfapyridine via a diazo bond. This bond is readily cleaved by bacterial azoreductases in the colon (Peppercorn 1972), to yield the two components. Of these, 5‐ASA has been found to be the therapeutically active component, while sulfapyridine, which is primarily absorbed into systemic circulation, is assumed to function solely as a carrier molecule (Azad Khan 1977; Klotz 1980; Van Hees 1980).

Administration of unbound or uncoated 5‐ASA revealed that it was readily absorbed in the upper jejunum and was unable to reach the colon in therapeutic concentrations (Schroeder 1972; Nielsen 1983; Myers 1987). Ingested SASP largely resists such premature absorption and thus is able to serve as a delivery system that transports the 5‐ASA to the affected regions of the lower intestinal tract (Schroeder 1972). While corticosteroid therapy is more effective for the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis (Truelove 1955; Truelove 1959) the use of SASP in maintaining remission has been well established (Misiewitz 1965; Sutherland 2006a).

Despite its benefits, up to 30% of patients receiving SASP have reported adverse events (Nielsen 1982). It was concluded that many were due to the sulfapyridine moiety, especially those effects found to be dose‐dependent (Das 1973; Myers 1987). This discovery spawned more than a decade of research aimed at finding alternative 5‐ASA delivery systems.

Asacol® (Proctor and Gamble) consists of a pellet of 5‐ASA destined for release in the terminal ileum or colon due to a coating known as Eudragit‐S, a resin that dissolves at a pH greater than 7 (Dew 1982). Claversal®/Mesasal® (Smith, Kline and French), Salofalk® (Axcan Pharma, Falk Foundation), and Rowasa® (Reid‐Rowell) are similar delayed‐release preparations of 5‐ASA pellets coated with Eudragit L, a resin that dissolves at a pH greater than 6 (the approximate pH of the ileum/colon) (Hardy 1987; Myers 1987). Pentasa® (Marion‐Merrell‐Dow) is a microsphere formulation that consists of 5‐ASA microgranules enclosed within a semi‐permeable membrane of ethylcellulose. It is designed for controlled release that begins in the duodenum and continues into the affected regions of the lower bowel (Rasmussen 1982). Olsalazine/Dipentum® (Pharmacia & Upjohn) consists of two 5‐ASA molecules linked by a diazo bond (Willoughby 1982; Staerk Laursen 1990). Other formulations, such as benzalazine, balsalazide/Colazide® (Astra Zeneca), and balsalazide disodium/Colazal® (Salix Pharmaceuticals) are composed of 5‐ASA molecules azo‐bonded to various benzoic acid derivatives (Chan 1983; Fleig 1988). Like SASP, these compounds are poorly absorbed in the upper digestive tract but are readily metabolized by the intestinal flora in the lower bowel. MMX mesalamine (Lialdaa® or Mezavant®) uses MMX Multi Matrix System (MMX) technology to delay and extend delivery of active drug throughout the colon (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007).

The newer 5‐ASA preparations were intended to avoid the adverse effects of SASP while maintaining its therapeutic benefits; however they are more costly and have also been shown to cause adverse effects in some patients (Rao 1987). The efficacy and safety of 5‐ASA preparations have been evaluated in numerous clinical trials that have often lacked sufficient statistical power to arrive at definitive conclusions. Previous systematic reviews (Sutherland 1993; Sutherland 1997; Sutherland 2006b; Feagan 2012), found that oral 5‐ASA, in doses of at least 2 g/day, was more effective than placebo yet no more effective than SASP for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. We proceeded with this updated review in order to include more recent studies as well as to evaluate the efficacy, dose‐responsiveness (including dose‐ranging studies of various 5‐ASA formulations), and safety of oral 5‐ASA preparations compared to placebo or SASP. We also aimed to investigate any differences in efficacy and safety between various formulations of oral 5‐ASA.

Many patients are non‐adherent with conventional multi‐dose (two or three times daily) treatment regimens which may result in reduced efficacy and can lead to an increased risk of relapse in patients with quiescent disease (Kane 2001; Kane 2003), a poorer long‐term prognosis (Kane 2008; Kruis 2009) and increased healthcare costs (Kane 2008; Beaulieu 2009). Poor adherence may be particularly problematic in quiescent disease (Kane 2001; Kane 2003), since patients lack continuing symptoms that incentivize them to take medication. Although multiple factors have been shown to influence medication adherence in patients with ulcerative colitis it is commonly believed that a high pill burden and multi‐dose regimens are major determinants (Ediger 2007; Kane 2008). Other factors affecting adherence in ulcerative colitis patients include disease extent and duration, medication costs, fear of side effects, individual psychosocial characteristics and the patient‐physician relationship (Kane 2008). Mesalamine formulations that involve once daily dosing may improve adherence and outcomes.

The efficacy and safety of once daily oral dosing of mesalamine compared to conventional dosing for the treatment of ulcerative colitis has been evaluated in numerous clinical trials. These trials have investigated the efficacy of once daily dosing of various formulations of mesalamine compared to conventional dosing schedules of the same drugs or different formulations. Many of these trials were small in size and lacked sufficient statistical power to arrive at definitive conclusions. A secondary objective of this systematic review was to investigate the efficacy and safety of once daily dosing of mesalamine compared to conventional dosing for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis.This systematic review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Feagan 2012).

Objectives

The primary objectives were to assess the efficacy, dose‐responsiveness, and safety of oral 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) compared to placebo, sulfasalazine (SASP), or 5‐ASA comparators (i.e. other formulations of 5‐ASA) for induction of remission in active ulcerative colitis. A secondary objective of this systematic review was to compare the efficacy and safety of once daily dosing of oral 5‐ASA with conventional dosing regimens.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Prospective, randomized controlled clinical trials of parallel design, with minimum treatment duration of four weeks were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Adult patients (> 18 years) with active mild‐to‐moderate ulcerative colitis as defined by Truelove and Witts were considered for inclusion (Truelove 1955).

Types of interventions

Studies of oral 5‐ASA therapy for treatment of patients with active ulcerative colitis compared with placebo, SASP or other formulations of 5‐ASA were considered for inclusion. Studies that compared once daily 5‐ASA treatment with conventional dosing of 5‐ASA (two or three times daily) and 5‐ASA dose ranging studies were also considered for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures included endoscopic, global or clinical measures of improvement or complete remission as defined by the authors of each study.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who failed to enter complete global or clinical remission as defined by the authors of each study and expressed as a percentage of total patients randomized (intention‐to‐treat analysis).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

the proportion of patients who failed to improve clinically;

the proportion of patients who failed to enter endoscopic remission;

the proportion of patients who failed to improve endoscopically;

the proportion of patients who failed to adhere with their medication regimen;

the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event;

the proportion of patients who withdrew due to adverse events; and

the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry.

Search methods for identification of studies

MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (Ovid SP), and the Cochrane Library were searched from inception to March 19, 2014. No language or document type restrictions were applied. The multipurpose search command for the Ovid SP interface (.mp.) was used to search both text and database subject heading fields. Review articles and conference proceedings were also searched to identify additional studies. The search strategies are listed in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Study Selection

Two authors (YW or JKM or CEP) independently selected relevant studies for analysis on the basis of the inclusion criteria described above. When necessary, the original investigators were contacted to clarify points regarding trial methodology. The reasons for exclusion were indicated for each study deemed ineligible.

Data Collection

Two authors (YW or JKM or CEP) independently extracted data using a standard data extraction form. We recorded results on an intention‐to‐treat basis, regardless of whether or not the original authors had done so. Any discrepancies between authors were settled by consensus.

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (YW or JKM or CEP) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). Factors assessed included:

sequence generation (i.e. was the allocation sequence adequately generated?);

allocation sequence concealment (i.e. was allocation adequately concealed?);

blinding (i.e. was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?);

incomplete outcome data (i.e. were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?);

selective outcome reporting (i.e. are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?); and

other potential sources of bias (i.e. was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?).

A judgement of 'Yes' indicates low risk of bias, 'No' indicates high risk of bias, and 'Unclear' indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Study authors were contacted when insufficient information was provided to determine risk of bias.

We used the GRADE approach for rating the overall quality of evidence for the primary outcomes and selected secondary outcomes of interest. Randomized trials start as high quality evidence, but may be downgraded due to: (1) limitations in design and implementation (risk of bias), (2) indirectness of evidence, (3) inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity), (4) imprecision (sparse data), and (5) reporting bias (publication bias). The overall quality of evidence for each outcome was determined after considering each of these elements, and categorized as high quality (i.e. further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect); moderate quality (i.e. further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate); low quality (i.e. further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate); and very low quality (i.e. we are very uncertain about the estimate) (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011).

Statistical Methods

Trials were separated into five comparison groups: 5‐ASA versus placebo, 5‐ASA versus sulfasalazine, once daily dosing versus conventional dosing, 5‐ASA versus comparator 5‐ASA, and 5‐ASA dose‐ranging. Within each group, raw data for every measured outcome were extracted and converted into individual 2x2 tables. The tables for placebo‐controlled trials were further subgrouped according to the dose of 5‐ASA. The tables for SASP‐controlled trials were subgrouped by 5‐ASA/SASP mass ratios. The tables for the once daily versus conventional dosing studies were subgrouped by formulation. The tables for 5‐ASA‐controlled trials were subgrouped by common 5‐ASA comparators (e.g. Asacol, Claversal, Salofalk and Pentasa). The tables for dose‐ranging studies were subgrouped by 5‐ASA formulation. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The results for each comparison group were pooled to determine the RR and 95% CI for each outcome resulting from 5‐ASA therapy relative to either placebo, SASP or 5‐ASA comparator and once daily 5‐ASA therapy relative to conventional dosing. A fixed‐effect model was used. Studies were pooled for analysis if patients, outcomes and interventions were similar (determined by consensus among authors). Studies comparing 5‐ASA formulations were pooled for analysis if they compared equimolar doses of oral 5‐ASA.

Dose‐responsiveness was analyzed using a Chi2 test for trend. Trials were also subgrouped according to the specific 5‐ASA preparation for those outcomes for which there were two or more studies that used a similar drug. Tests for homogeneity among trials within each comparison group were performed. The presence of heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Chi2 test (a P value of 0.10 was regarded as statistically significant) and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). If statistically significant heterogeneity was identified, the RR and 95% CI were calculated using a random‐effects model. Data were not pooled for meta‐analysis if a high degree of heterogeneity was identified (e.g. I2 > 75%). We conducted sensitivity analyses as appropriate to investigate heterogeneity. We also conducted sensitivity analyses excluding studies with a high risk of bias. All statistical analyses were performed using the Cochrane Collaboration RevMan 5 software package.

Results

Description of studies

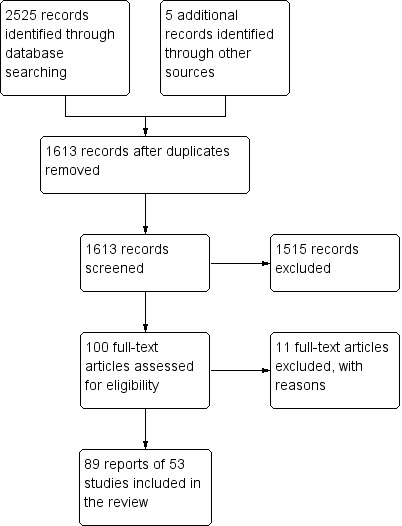

A literature search conducted on July 9, 2015 identified 2525 studies. Five additional studies were identified through searching of references. After duplicates were removed a total of 1613 reports remained for review of titles and abstracts. Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these studies and 100 reports of oral 5‐ASA for treatment of active ulcerative colitis were selected for full text review (See Figure 1). Eleven of these studies were excluded (See Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Eighty‐nine reports of fifty‐three studies involving a total of 8548 patients, were selected for inclusion (See Characteristics of included studies). Sixteen studies were placebo‐controlled (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Sutherland 1990; Zinberg 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Hanauer 1996; Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Sandborn 2012; Feagan 2013; Pontes 2014). Eighteen studies compared 5‐ASA to SASP (Maier 1985; Andreoli 1987; Ewe 1988; Fleig 1988; Mihas 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Bresci 1990; Rijk 1991; Good 1992; Munakata 1995; Cai 2001; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Jiang 2004; Qian 2004). Four studies compared once daily dosing of mesalamine with conventional dosing (Kamm 2007; Kruis 2009; Lichtenstein 2007; Flourie 2013). The Kamm 2007 study had four treatment arms including placebo, Asacol 2.4 g/day (dosed 3 times daily) and two different doses of once daily MMX mesalamine (2.4 g and 4.8 g per day). Kruis 2009 was a formal non‐inferiority study comparing mesalazine (Salofalk granules) 3.0 g dosed once daily with 1 g dosed three times daily. The Lichtenstein 2007 study had three treatment arms including placebo, MMX mesalamine 2.4 g dosed twice daily and MMX mesalamine 4.8 g dosed once daily. In Flourie 2013 patients received 4.0 g of mesalazine once daily or 2.0 g of meslazine twice daily for a total of 8 weeks. Ten trials were dose‐ranging studies of oral 5‐ASA (Schroeder 1987; Miglioli 1990; Sninsky 1991; Kruis 2003; Hanauer 2005; D'Haens 2006; Hanauer 2007; Kamm 2007; Sandborn 2009; Hiwatashi 2011). Twelve trials compared the efficacy and safety of various formulations of oral 5‐ASA to other formulations of oral 5‐ASA (Green 1998; Kruis 1998; Farup 2001; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Forbes 2005; Marakhouski 2005; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010).

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risk of bias assessment is provided in Figure 2. Most of the included studies were of high methodological quality. Five studies were rated at high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data (Green 1998; Kruis 2003) and lack of blinding (Farup 2001; Tursi 2004; Flourie 2013). Thirty‐two of 53 included studies did not describe the method used for randomization and were rated as unclear for this item. Twenty‐six studies did not describe methods used for allocation concealment and were rated as unclear for this item. The methods used for blinding were not described in five studies, and these studies were rated as unclear. Twenty studies were rated as unclear for incomplete outcome data because reasons for withdrawal were either not described or were not attributed to intervention groups. Six studies were rated as unclear for selective reporting.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral 5‐ASA versus placebo for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis.

| Oral 5‐ASA versus placebo for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis Settings: Outpatients Intervention: Oral 5‐ASA versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral 5‐ASA versus placebo | |||||

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

830 per 10001 | 714 per 1000 (681 to 739) | RR 0.86 (0.82 to 0.89) | 2,387 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

651 per 10001 | 443 per 1000 (397 to 488) | RR 0.68 (0.61 to 0.75) | 2,256 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Adverse events | 486 per 10001 | 462 per 1000 (413 to 520) | RR 0.95 (0.85 to 1.07) | 1,218 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 62 per 10001 | 55 per 1000 (38 to 77) | RR 0.88 (0.62 to 1.24) | 2,091 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimates come from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to heterogeneity I2 = 47%. 3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (122 events).

Summary of findings 2. Oral 5‐ASA versus SASP for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis.

| Oral 5‐ASA versus SASP for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis Settings: Outpatients Intervention: Oral 5‐ASA versus SASP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral 5‐ASA versus SASP | |||||

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

583 per 10001 | 525 per 1000 (449 to 606) | RR 0.90 (0.77 to 1.04) | 526 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

467 per 10001 | 411 per 1000 (355 to 472) | RR 0.88 (0.76 to 1.01) | 1,053 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| Adverse events | 287 per 10001 | 138 per 1000 (103 to 181) | RR 0.48 (0.36 to 0.63) | 909 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 129 per 10001 | 52 per 1000 (31 to 88) | RR 0.40 (0.24 to 0.68) | 640 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimates come from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (294 events). 3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (190 events). 4 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (54 events).

Summary of findings 3. Once daily dosing versus conventional dosing for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis.

| Once daily dosing versus conventional dosing for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis Settings: Outpatients Intervention: Once daily dosing versus conventional dosing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | OD versus conventional dosing | |||||

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

477 per 10001 | 448 per 1000 (396 to 510) | RR 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) | 944 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

458 per 10001 | 398 per 1000 (311 to 504) | RR 0.87 (0.68 to 1.10) | 358 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Failure to adhere to medication regimen | 139 per 10001 | 189 per 1000 (89 to 398) | RR 1.36 (0.64 to 2.86) | 358 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Adverse events | 374 per 10001 | 329 per 1000 (273 to 400) | RR 0.88 (0.73 to 1.07) | 769 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 24 per 10001 | 14 per 1000 (6 to 35) | RR 0.58 (0.23 to 1.44) | 940 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimates come from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (153 events). 3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (26 events). 4 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (271 events). 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (9 events).

Summary of findings 4. Oral 5‐ASA versus comparator 5‐ASA for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis.

| Oral 5‐ASA versus comparator 5‐ASA for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis Settings: Outpatients Intervention: Oral 5‐ASA versus 5‐ASA (different formulations) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral 5‐ASA versus comparator 5‐ASA | |||||

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

519 per 10001 | 488 per 1000 (446 to 529) | RR 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) | 1,968 (11 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | A sensitivity analysis excluding two high risk of bias studies produced similar results (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.87 to 1.04; P = 0.28) |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

346 per 10001 | 308 per 1000 (266 to 350) | RR 0.89 (0.77 to 1.01) | 1,647 (8 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | A sensitivity analysis excluding one high risk of bias study produced similar results (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.05; P = 0.20) |

| Adverse events | 457 per 10001 | 462 per 1000 (420 to 512) | RR 1.01 (0.92 to 1.12) | 1,576 (9 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 39 per 10001 | 37 per 1000 (20 to 60) | RR 0.94 (0.57 to 1.54) | 1,489 (9 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimates come from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias in two studies in the pooled analysis (both due to lack of blinding). 3 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias in one study in the pooled analysis (lack of blinding). 4 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias in one study in the pooled analysis (lack of blinding). 5 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (57 events).

Summary of findings 5. High dose oral 5‐ASA versus low dose 5‐ASA for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis.

| High dose oral 5‐ASA versus low dose 5‐ASA for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis Settings: Outpatients Intervention: High dose oral 5‐ASA versus low dose 5‐ASA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | High dose 5‐ASA versus low dose 5‐ASA | |||||

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

602 per 10001 | 620 per 1000 (494 to 777) | RR 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | 194 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | MMX mesalazine 4.8 g/day OD versus 2.4 g/day OD |

|

Failure to induce global or clinical remission |

495 per 10001 | 337 per 1000 (243 to 470) | RR 0.68 (0.49 to 0.95) | 210 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low3,4 | Salofalk 3 g/day versus 1.5 g/day |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

413 per 10001 | 368 per 1000 (322 to 417) | RR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | 1,459 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Asacol 4.8 g/day versus 2.4 g/day (Ascend I, II and III) in patients with moderate ulcerative colitis |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

727 per 10001 | 262 per 1000 (138 to 501) | RR 0.36 (0.19 to 0.69) | 49 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low5 | Asacol 4.8 g/day versus 1.6 g/day |

|

Failure to induce clinical improvement |

571 per 10001 | 251 per 1000 (154 to 405) | RR 0.44 (0.27 to 0.71) | 123 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | Pentasa 4 g/day versus 2.25 g/day |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk estimates come from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (118 events). 3 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias (incomplete outcome data). 4 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (87 events). 5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (18 events). 6 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (51 events).

EFFICACY

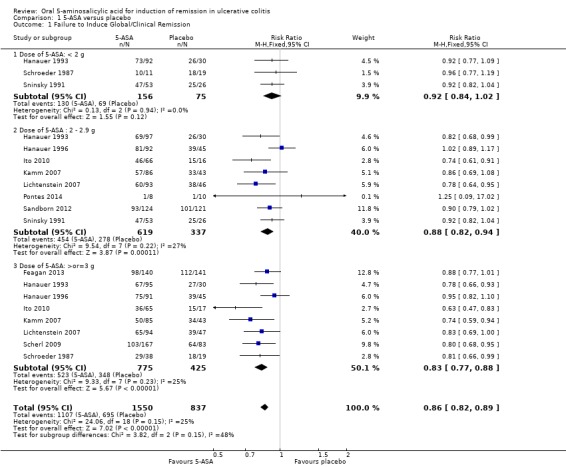

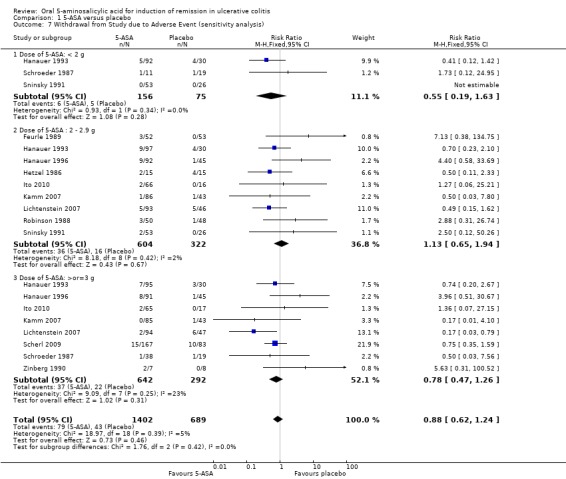

5‐ASA versus Placebo Eleven trials (n = 2387 patients) reported treatment outcomes in terms of the failure to induce complete global or clinical remission (Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Hanauer 1996; Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Sandborn 2012; Feagan 2013; Pontes 2014). Seventy‐one per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to enter remission compared to 83% of placebo patients. The pooled relative risk (RR) of failure to induce complete global or clinical remission for all trials was 0.86 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.89; I2 = 25%; P < 0.00001) using a fixed‐effect model. There was a trend towards greater efficacy with higher doses of 5‐ASA with a statistically significant benefit for the 2 to 2.9 g/day (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.82 to 0.94; I2 = 27%; P = 0.0001) and the > 3 g/day subgroups (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.88; I2 = 25%; P < 0.00001). The five trials that involved Asacol® (Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013), had a pooled RR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.90). Two trials using MMX mesalazine (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007), had a pooled RR of 0.81 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.90). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome for the placebo‐controlled studies (failure to induce complete global or clinical remission) was high (See Table 1).

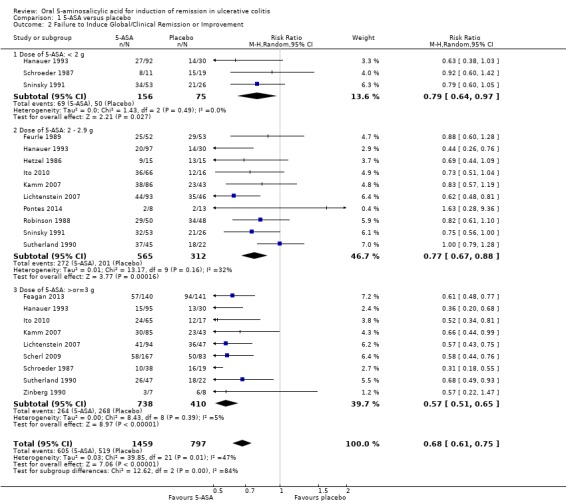

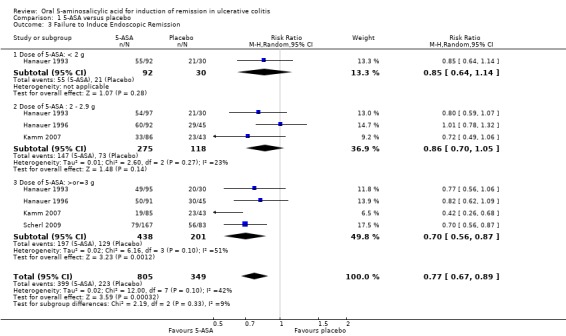

Fourteen trials (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Sutherland 1990; Zinberg 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013; Pontes 2014), comprised of 2169 patients, provided data regarding the failure to induce global or clinical improvement (including remission). Forty‐two per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to improve clinically compared to 65% of placebo patients. The pooled RR for all trials was 0.68 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.75; I2 = 47%; P < 0.00001) using a random‐effects model. There was a trend towards greater efficacy with higher doses of 5‐ASA (P = 0.003) with a statistically significant benefit for all dosage subgroups: < 2 g/day (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97; I2 = 0%; P = 0.49); 2 to 2.9 g/day (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.67 to 0.88; I2 = 32%; P = 0.0002); > 3 g/day (RR 0.57; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.65; I2 = 5%; P < 0.00001). Five trials involving Asacol® (Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013), had a pooled RR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.80). Four studies involved olsalazine (Hetzel 1986; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Zinberg 1990), and resulted in a pooled RR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.97). Two trials using MMX mesalazine (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007), had a pooled RR of 0.61 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.72). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the placebo‐controlled studies (failure to induce global or clinical improvement) was moderate due to heterogeneity I2 = 47% (See Table 1). Four studies (Hanauer 1993; Hanauer 1996; Kamm 2007; Scherl 2009), with a total of 1154 patients, reported on failure to induce complete endoscopic remission. Fifty per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to enter endoscopic remission compared to 66% of placebo patients. The superiority of 5‐ASA over placebo was demonstrated by a pooled RR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.89; I2 = 42%; P = 0.0003) using a random‐effects model. Within the dosage subgroups, the superiority of 5‐ASA only reached statistical significance for treatment arms involving doses equal to or greater than 3 g (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.87; I2 = 51%; P = 0.001).

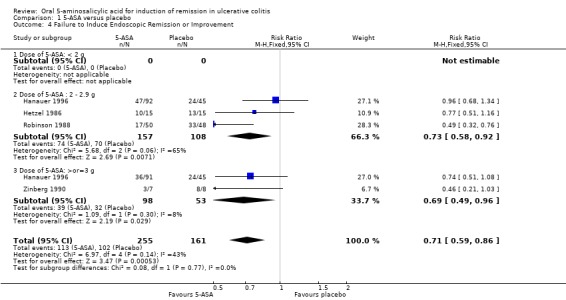

Four trials (Hanauer 1996; Hetzel 1986; Robinson 1988; Zinberg 1990), with a total of 416 patients, all involving olsalazine, reported the failure to induce endoscopic remission or improvement. Forty‐four per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to improve endoscopically compared to 63% of placebo patients. The pooled RR was 0.71 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.86; I2 = 43%; P = 0.0005) using a fixed‐effect model.

5‐ASA versus Sulfasalazine

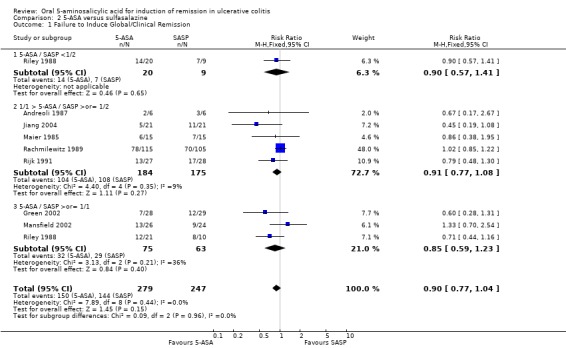

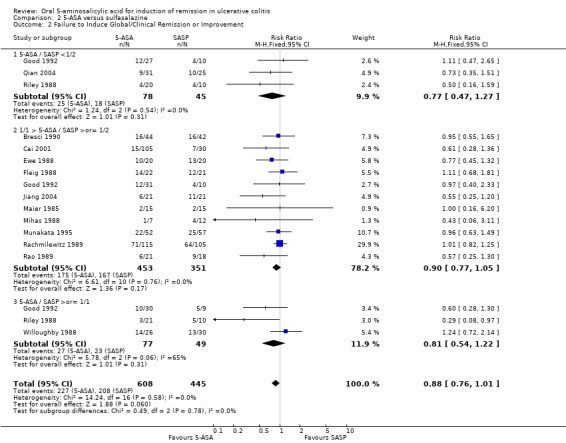

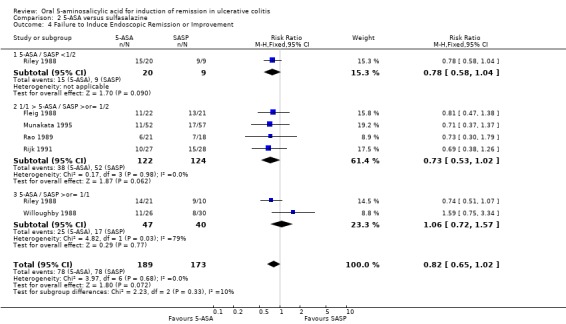

The failure to induce complete global or clinical remission was reported in eight studies with a total of 526 patients (Maier 1985; Andreoli 1987; Riley 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rijk 1991; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Jiang 2004). Fifty‐four per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to enter remission compared to 58% of SASP patients. A statistically significant difference between 5‐ASA and SASP was not observed, pooled RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.04; I2 = 0%; P = 0.15). Two studies involving Claversal® (Andreoli 1987; Rachmilewitz 1989), had a pooled RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.21). Two studies involving balsalazide (Green 2002; Mansfield 2002), had a pooled RR of 0.66 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.02). Two studies involving olsalazine (Jiang 2004), had a pooled RR of 0.93 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.51). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome for the SASP‐controlled studies (failure to induce complete global or clinical remission) was moderate due to imprecision (sparse data, 294 events; See Table 2).

Thirteen trials (Maier 1985; Ewe 1988; Fleig 1988; Mihas 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Bresci 1990; Good 1992; Munakata 1995; Jiang 2004; Qian 2004), with a total of 1053 patients reported the failure to induce global/clinical remission or improvement. Thirty‐seven per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to improve compared to 47% of SASP patients. A statistically significant difference between 5‐ASA and SASP was not observed, The pooled RR was 0.88 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.01; I2 = 0%; P = 0.06). Six olsalazine trials (Ewe 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rao 1989; Cai 2001; Jiang 2004; Qian 2004), had a pooled RR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.00). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the SASP‐controlled studies (failure to induce global or clinical improvement) was high (See Table 2).

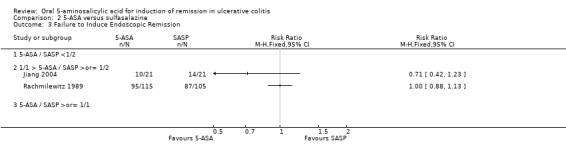

Since only two trials (Jiang 2004; Rachmilewitz 1989), reported the failure to induce complete endoscopic remission, this outcome was not considered in our analysis. A pooled RR for complete endoscopic remission was not calculated, as the two studies used different indices to measure endoscopic remission. Neither study showed statistically significant differences in complete endoscopic remission between 5‐ASA and SASP. However, six studies (Fleig 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rao 1989; Rijk 1991; Munakata 1995), with a total of 362 patients provided data regarding the failure to induce endoscopic improvement (including remission). Forty‐one per cent of 5‐ASA patients failed to improve endoscopically compared to 45% of SASP patients. The pooled RR of 0.82 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.02; I2 = 0%; P = 0.07) indicated a non‐significant trend towards the superiority of 5‐ASA over SASP. Three trials involving olsalazine (Rao 1989; Rijk 1991; Willoughby 1988), had a pooled RR of 0.88 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.71).

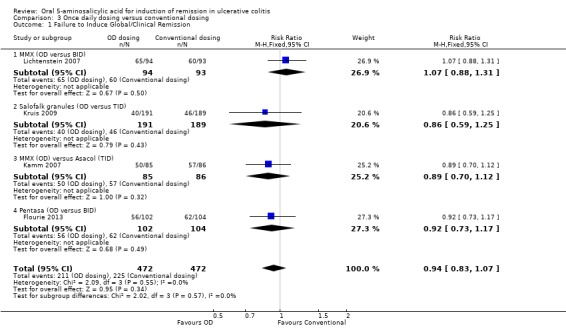

Once Daily Dosing versus Conventional Dosing

Four trials (n = 944 patients) reported treatment outcomes in terms of the failure to induce complete global or clinical remission (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009; Flourie 2013). Forty‐eight per cent of conventionally dosed 5‐ASA patients failed to enter remission compared to 45% of patients who were dosed once daily. The pooled RR was 0.94 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.07; I2 = 0%) showing no statistically significant difference between once daily dosing and conventional dosing for induction of remission (P = 0.34). None of the subgroup comparisons by formulation showed any differences in efficacy between once daily dosing and conventional dosing. However, only four formulations were evaluated in this pooled analysis. The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome (failure to induce complete global or clinical remission) was high (See Table 3).

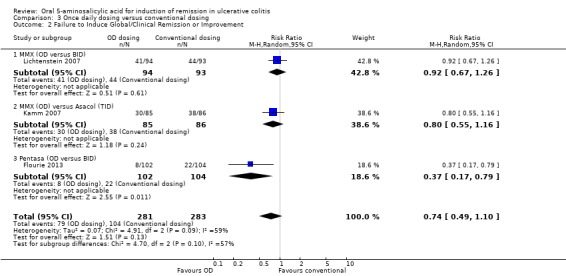

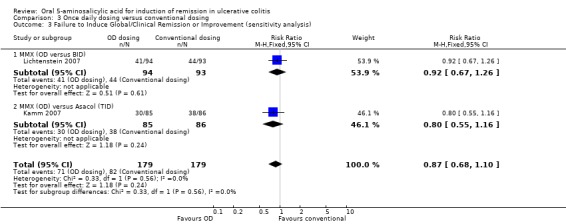

Three trials (n = 564 patients) reported treatment outcomes in terms of the failure to induce global or clinical improvement including remission (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Flourie 2013). Thirty‐seven per cent of conventionally dosed 5‐ASA patients failed to improve clinically compared to 28% of patients who were dosed once daily. The pooled RR was 0.74 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.10) showing no statistically significant difference between once daily dosing and conventional dosing for induction of remission or clinical improvement (P = 0.13). A fair amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 59%) was detected for this comparison. A visual inspection of the forest plot indicated that the Flourie 2013 study was the likely source of the heterogeneity. When we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding this high risk of bias study the I2 value dropped to 0%. Forty‐six per cent of conventionally dosed 5‐ASA patients failed to improve clinically compared to 40% of patients who were dosed once daily (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.10). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to improve clinically) was moderate due to sparse data (153 events; See Table 3).

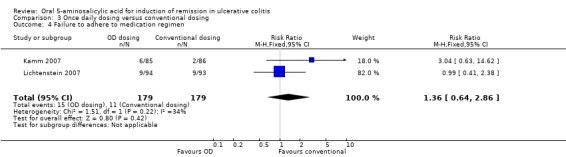

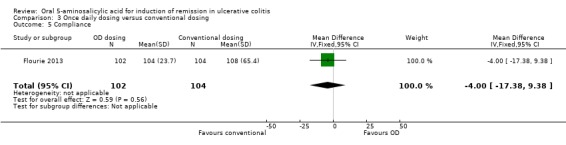

Two studies provided dichotomous data regarding the failure to adhere to medication regimen at study endpoint (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007). The pooled analysis of the ITT population for the two studies included 358 patients. The pooled RR was 1.36 (95% CI 0.64 to 2.86; I2 = 34%) showing no statistically significant difference in medication adherence between once daily dosing and conventional dosing at eight weeks (P = 0.42). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to improve clinically) was low due to very sparse data (26 events; See Table 3). Flourie 2013 reported on a continuous outcome for compliance with medication. There was no statistically significant difference in compliance with medication (MD ‐4.00, 95% CI ‐17.38 to 9.38).

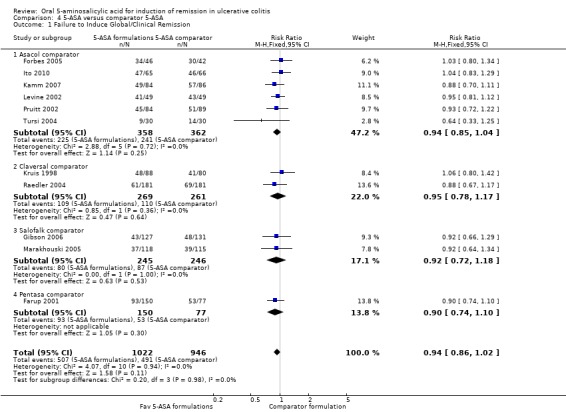

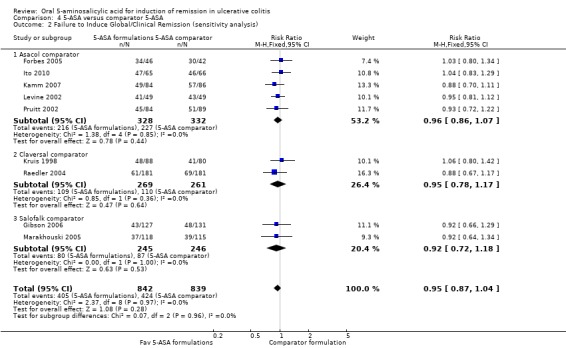

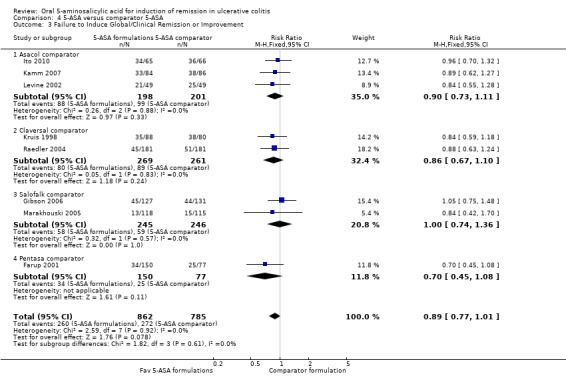

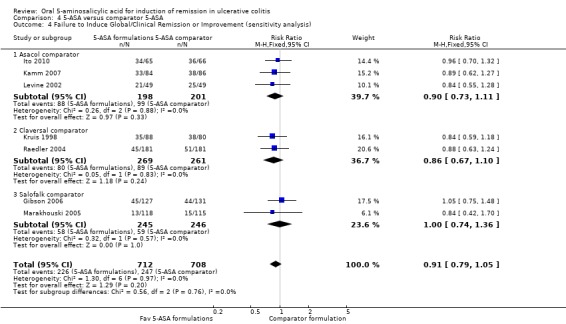

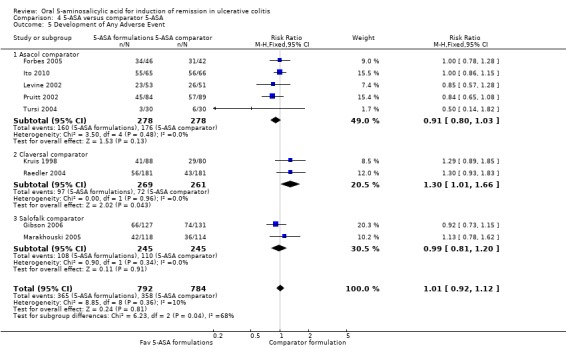

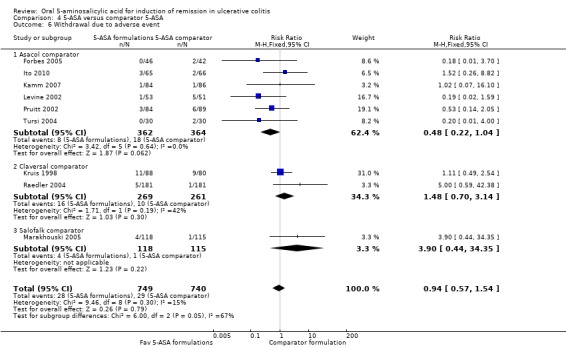

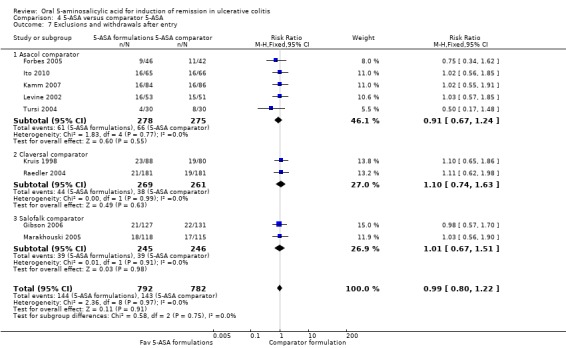

5‐ASA versus Comparator 5‐ASA

Eleven studies (n = 1968 patients) reported treatment outcomes in terms of the failure to induce complete global or clinical remission (Kruis 1998; Farup 2001; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Forbes 2005; Marakhouski 2005; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010). The Green 1998 study was not included in the pooled analysis because it enrolled patients with moderate to severe disease whereas the other studies in the pooled analysis enrolled patients with mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. The Green 1998 study also allowed the use of rectal steroid foam to relieve active symptoms which was not allowed in the other 5‐ASA controlled studies. The overall pooled risk ratio showed no statistically significant difference in failure to enter global or clinical remission between various formulations of 5‐ASA (including Balsalazide, Pentasa, Olsalazine, MMX mesalazine; Ipocol and 5‐ASA micropellets) and comparator formulations of 5‐ASA (including Asacol, Claversal and Salofalk). Fifty per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group failed to enter remission compared to 52% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group. The pooled RR of failure to induce complete global or clinical remission for all trials was 0.94 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.02; I2 = 0%; P = 0.11) using a fixed‐effect model. The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome (failure to induce complete global or clinical remission) was moderate due to a high risk of bias (lack of blinding) in two studies in the pooled analysis (See Table 4). However, a sensitivity analysis excluding the two high risk of bias studies (Farup 2001; Tursi 2004) produced similar results (9 studies; n = 1681). Forty‐eight per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group failed to enter remission compared to 50% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group. The pooled RR for failure to induce complete global or clinical remission was 0.95 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.04; I2 = 0%; P = 0.28) using a fixed‐effect model. The Green 1998 study compared Balsalazide 6.75 g/day (n = 50) to Asacol 2.4 g/day (n = 49). At eight weeks 22% of patients in the Balsalazide group failed to enter remission compared to 45% of patients in the Asacol group (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.90).

Eight studies (n = 1647 patients) reported treatment outcomes in terms of failure to induce global/clinical improvement including remission (Kruis 1998; Farup 2001; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Marakhouski 2005; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010). The overall pooled RR showed no statistically significant difference in failure to improve clinically between various formulations of 5‐ASA (including Balsalazide, Pentasa, Olsalazine, MMX mesalazine; and 5‐ASA micropellets) and comparator formulations of 5‐ASA (including Asacol, Claversal, Salofalk and Pentasa). Thirty per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group failed to improve clinically compared to 35% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group. The pooled RR for failure to improve clinically for all trials was 0.89 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.01; I2 = 0%; P = 0.08) using a fixed‐effect model. The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce clinical improvement) was moderate due to a high risk of bias (lack of blinding) in one study in the pooled analysis (See Table 4). However, a sensitivity analysis excluding the high risk of bias study (Farup 2001) produced similar results (7 studies; n = 1420). Thirty‐two per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group failed to improve clinically compared to 35% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group. The pooled RR for failure to improve clinically was 0.91 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.05; I2 = 0%; P = 0.20) using a fixed‐effect model.

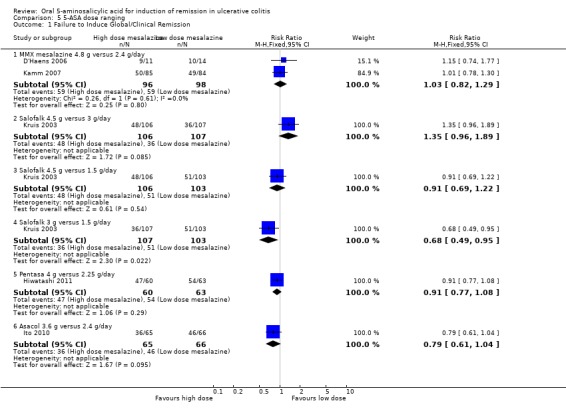

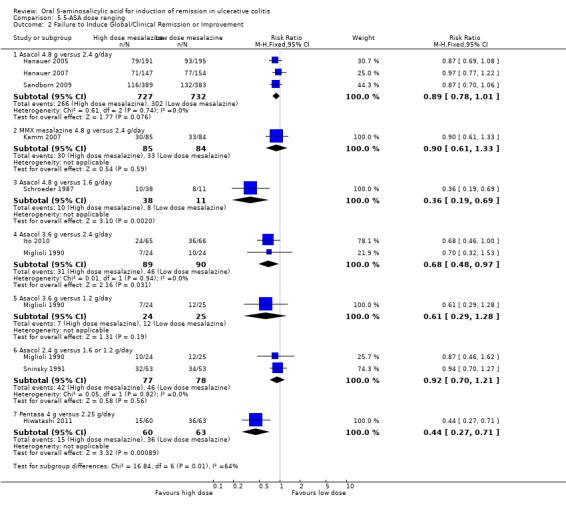

5‐ASA Dose Ranging

Several randomized trials have looked at dose‐ranging for various formulations of 5‐ASA (e.g. Asacol, Salofalk, Pentasa, MMX mesalamine). Two studies examined the efficacy of various doses of Salofalk or Pentasa for induction of global or clinical remission in patients with mild or moderately active ulcerative colitis (Kruis 2003; Hiwatashi 2011). Kruis 2003 found no statistically significant difference in efficacy between Salofalk 4.5 g/day compared to 3 g/day (213 patients; RR 1.35; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.89) or 1.5 g/day (212 patients; RR 0.91 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.22). Kruis 2003 found a statistically significant difference between Salofalk 3 g/day compared to 1.5 g/day. Thirty‐four per cent of patients in the 3 g/day group failed to enter remission compared to 50% of patients in the 1.5 g/day group. The pooled RR was 0.68 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.95; P = 0.02). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce global or clinical remission) was low due to a high risk of bias (incomplete outcome data) and sparse data (87 events: See Table 5). Hiwatashi 2011 examined the efficacy of Pentasa 4 g/day compared to 2.25 g/day in patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. No statistically significant difference in failure to induce remission was found between Pentasa 4 g/day and 2.25 g/day (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.08).

D'Haens 2006 and Kamm 2007 investigated the efficacy of MMX mesalamine 2.4 g/day dosed once daily versus 4.8 g/day dosed once daily for induction of remission in active ulcerative colitis. The pooled analysis of the ITT population included 194 patients. Sixty‐one per cent of patients in the 4.8 g/day group failed to enter remission compared to 60% of patients in the 2.4 g/day group. The pooled RR was 1.03 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.29; I2 = 0%; P = 0.80) showing no statistically significant difference between the 4.8 g and 2.4 g/day groups. The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce global or clinical remission) was moderate due to sparse data (118 events: See Table 5).

Six studies examined the efficacy of various doses of Asacol for global/clinical improvement including remission in patients with mild or moderately active ulcerative colitis (Schroeder 1987; Miglioli 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 2005; Hanauer 2007; Sandborn 2009). Schroeder 1987 found 4.8 g/day Asacol to be significantly more effective than 1.6 g/day for induction of clinical improvement (49 patients; RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.69). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce clinical improvement) was low due sparse data (18 events from one small study: See Table 5). Miglioli 1990 found no statistically significant difference in efficacy between Asacol 3.6 g/day compared to 2.4 g/day (48 patients; RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.53) or 1.2 g/day (49 patients; RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.29 to 1.28). A pooled analysis of two studies (Miglioli 1990; Sninsky 1991: n = 155 patients) found no statistically significant difference between Asacol 2.4 g/day and 1.6g or 1.2 g/day (RR0.92; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.21). A pooled analysis of the ASCEND (I, II and III, n = 1459 patients) studies found no statistically significant difference in clinical improvement between Asacol 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day. Thirty‐seven per cent of patients in the 4.8 g/day group failed to improve clinically compared to 41% of patients in the 2.4 g/day group (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.01; I2 = 0%; P = 0.08). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce clinical improvement) was high (See Table 5). Subgroup analyses indicated that patients with moderate disease may benefit from the higher dose of 4.8 g/day (Hanauer 2005; Hanauer 2007), particularly among patients previously treated with corticosteroids, oral 5‐ASA, rectal therapies or multiple ulcerative colitis medications (Hanauer 2005; Hanauer 2007; Sandborn 2009).

Kamm 2007 provided data regarding the failure to induce global/clinical remission or improvement. The ITT population included 169 patients. Thirty‐five per cent of patients in the 4.8 g/day group failed to improve clinically compared to 39% of patients in the 2.4 g/day group. The RR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.33; P = 0.59) showing no statistically significant difference between the 4.8 g and 2.4 g/day groups.

Hiwatashi 2011 examined the efficacy of Pentasa 4 g/day compared to 2.25 g/day in patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Twenty‐five per cent of patients in the 4 g/day group failed to improve clinically compared to 57% of patients in the 2.25 g/day group (RR 0.44; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.71; P < .001). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (failure to induce clinical improvement) was moderate due sparse data (51 events; See Table 5).

SAFETY

Three different outcome measures were used to evaluate safety: the proportion of patients with adverse events, the proportion of patients withdrawing due to adverse events, and the total number of patients excluded or withdrawn before completion of the study. Since many studies only reported the total number of adverse events rather than the number of patients who experienced an event, we were often unable to include such data in the analysis.

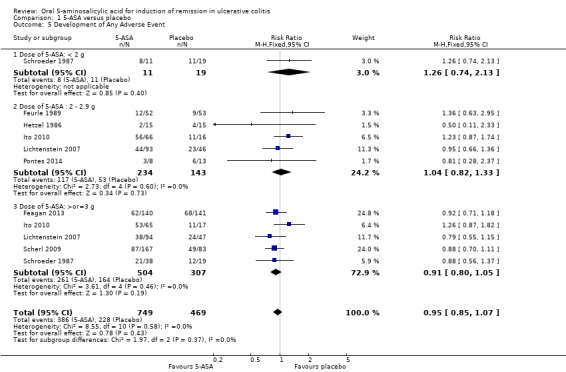

5‐ASA versus Placebo

Eight studies (n = 1218 patients) reported the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Feurle 1989; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013; Pontes 2014). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of adverse events between 5‐ASA and placebo patients. Fifty‐two per cent of 5‐ASA patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to 49% of placebo patients (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.07; I2 = 0%; P = 0.43). Three trials that involved Asacol® (Schroeder 1987: Ito 2010; Feagan 2013), had a pooled RR of 1.03 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.21). Two studies that involved Olsalazine (Hetzel 1986; Feurle 1989), had a pooled RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.15). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the placebo‐controlled studies (the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event) was high (See Table 1).

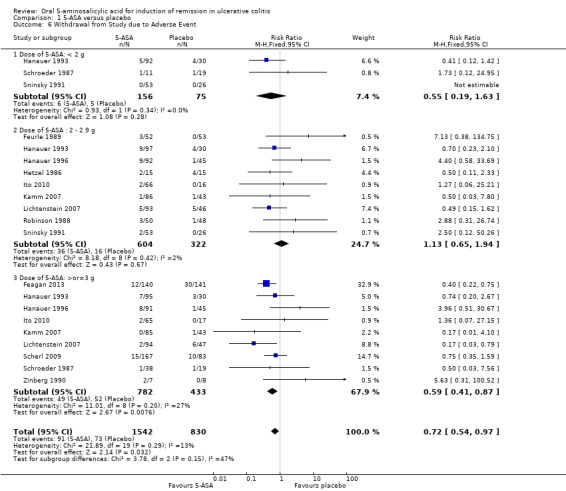

Thirteen studies (n = 2372 patients) reported the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Zinberg 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Hanauer 1996; Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013). There was a statistically significant difference in withdrawal due to adverse events favoring 5‐ASA over placebo patients. Withdrawals due to adverse events were reported for 6% of 5‐ASA patients compared to 9% of placebo patients (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.97; I2 = 13%; P = 0.03). The pooled analysis of five Asacol® trials (Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013) showed that a significantly higher proportion of placebo patients (9.7%) were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to Asacol® patients (3.5%) (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.84) . However, when five olsalazine studies (Hetzel 1986; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Zinberg 1990; Hanauer 1996) were pooled a significantly higher proportion of olsalazine patients (8.8%) were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to placebo (3.3%) (RR 2.58; 95% CI 1.16 to 5.70). When two MMX mesalamine studies were pooled (Lichtenstein 2007; Kamm 2007) a significantly higher proportion of placebo patients (8.8%) were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to MMX mesalamine (2.6%) (RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.72). An inspection of the forest plot showed that the statistically significant difference in withdrawals favoring 5‐ASA over placebo was driven by the large Feagan 2013 study, which reported that worsening of ulcerative colitis was the most common adverse event leading to withdrawal. Worsening of ulcerative colitis leading to withdrawal was reported for 10 of 12 withdrawals in the 5‐ASA group compared to 30 of 30 withdrawals in the placebo group (Feagan 2013). A sensitivity analysis excluding the Feagan 2013 study showed no statistically significant difference in withdrawals due to adverse events between 5‐ASA and placebo. Withdrawals due to adverse events occurred in 5.6% of 5‐ASA patients compared to 6% of placebo patients (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.62 to 1.24; I2 = 5%; P = 0.46). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the placebo‐controlled studies (the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events) was moderate due to sparse data (122 events; See Table 1).

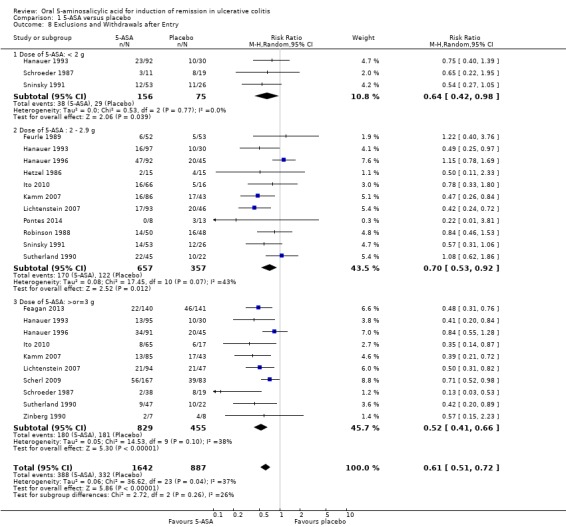

Fifteen studies (n = 2529 patients) reported the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Sutherland 1990; Zinberg 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Hanauer 1996; Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010; Feagan 2013; Pontes 2014). Significantly fewer 5‐ASA patients were withdrawn or excluded after entry than placebo patients. Twenty‐four per cent of 5‐ASA patients were withdrawn or excluded after entry compared to 37% of placebo patients (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.72; I2 = 37%; P < 0.00001; See Analysis 1.8). However, the studies were heterogeneous (P = 0.04; I2 = 37%) and this result should be interpreted with caution.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 5‐ASA versus placebo, Outcome 8 Exclusions and Withdrawals after Entry.

Commonly reported adverse events included: headache (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Sutherland 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993; Kamm 2007; Scherl 2009; Pontes 2014), nausea (Hetzel 1986; Schroeder 1987; Feurle 1989; Hanauer 1993; Kamm 2007; Scherl 2009), abdominal pain or cramps (Schroeder 1987; Feurle 1989; Sutherland 1990; Hanauer 1993; Kamm 2007; Pontes 2014), nasopharyngitis or symptoms of upper respiratory infection (Sutherland 1990; Kamm 2007; Scherl 2009; Ito 2010), rash (Hetzel 1986; Zinberg 1990; Sninsky 1991; Hanauer 1993), anorexia or loss of appetite (Hetzel 1986; Feurle 1989; Hanauer 1993), flatulence or gas ( Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Kamm 2007), dizziness (Schroeder 1987; Kamm 2007), gastrointestinal disorders (Feagan 2013) and fever (Schroeder 1987; Hanauer 1993). Diarrhea was reported in four studies involving Olsalazine (Robinson 1988; Feurle 1989; Zinberg 1990; Hanauer 1996) and one study of Pentasa (Hanauer 1993).

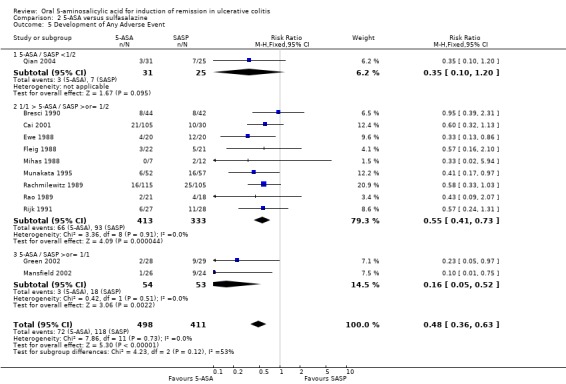

5‐ASA versus Sulfasalazine Twelve studies (n = 909 patients) reported the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event (Ewe 1988; Fleig 1988; Mihas 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Bresci 1990; Rijk 1991; Munakata 1995; Cai 2001; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Qian 2004). It should be noted that with two exceptions (Mihas 1988; Rao 1989), the inclusion criteria for entry included tolerance of SASP. Nevertheless, SASP patients were significantly more likely than 5‐ASA patients to experience an adverse event. Fifteen per cent of 5‐ASA patients experienced at least one adverse event compared to 29% of SASP patients (RR 0.48; 95% CI 0.36 to 0.63; I2 = 0%; P < 0.00001). Five olsalazine trials (Ewe 1988; Rao 1989; Rijk 1991; Cai 2001; Qian 2004) had a combined RR of 0.48 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.71) and two balsalazide trials (Green 2002; Mansfield 2002) had a combined RR of 0.16 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.52).The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the SASP‐controlled studies (the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event) was moderate due to sparse data (188 events; See Table 2).

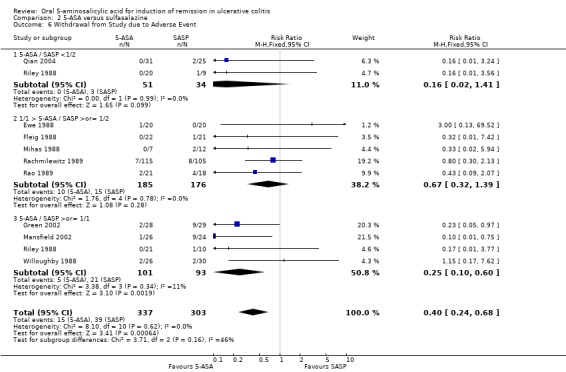

Ten studies (n = 640 patients) reported the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events (Ewe 1988; Fleig 1988; Mihas 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Qian 2004). SASP resulted in a significantly higher proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events. Thirteen per cent of SASP patients were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to 5% of 5‐ASA patients (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.68; I2 = 0%; P = 0.0006). When four olsalazine trials were combined (Ewe 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rao 1989; Qian 2004), the RR was 0.63 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.66). The pooling of two balsalazide trials (Green 2002; Mansfield 2002) had a combined RR of 0.16 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.52). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome for the SASP‐controlled studies (the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events) was moderate due to sparse data (52 events; See Table 2).

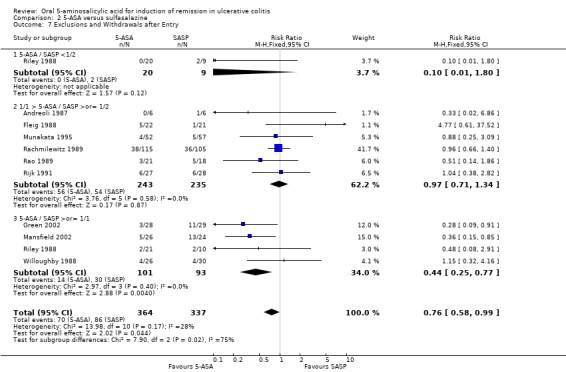

Ten studies (n = 701 patients) reported the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry (Andreoli 1987; Fleig 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Rijk 1991; Munakata 1995; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002). Twenty‐six per cent of SASP patients were withdrawn or excluded after entry compared to 19% of 5‐ASA patients (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.99; I2 = 28%; P = 0.04).

Commonly reported adverse events included: nausea (Ewe 1988; Fleig 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Rao 1989; Good 1992; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Jiang 2004), headache (Ewe 1988; Riley 1988; Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002), dyspepsia (Riley 1988; Rao 1989; Bresci 1990; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002; Jiang 2004), vomiting (Fleig 1988; Riley 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Mansfield 2002), abdominal pain (Rachmilewitz 1989; Green 2002; Mansfield 2002), and rash (Willoughby 1988; Rachmilewitz 1989; Mansfield 2002), Diarrhea was reported in three studies involving olsalazine (Ewe 1988; Willoughby 1988; Jiang 2004).

Once Daily Dosing versus Conventional Dosing

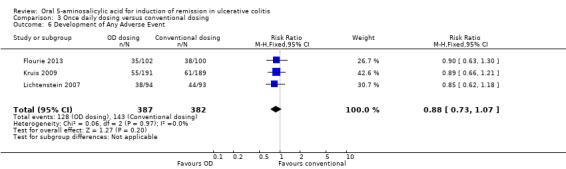

Three studies (n = 769 patients) reported the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event (Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009; Flourie 2013). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of adverse events between once daily and conventionally dosed patients. Thirty‐three per cent of patients who were dosed once daily experienced at least one adverse event compared to 37% of conventionally dosed patients (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.07; I2 = 0%; P = 0.20). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event) was moderate due to sparse data (271 events; See Table 3).

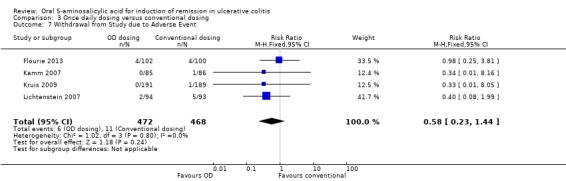

Four studies (n = 940 patients) reported the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events between once daily and conventionally dosed patients. Two per cent of conventionally dosed patients were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to 1% of patients dosed once daily (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.44; I2 = 0%; P = 0.24). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events) was low due to very sparse data (9 events; See Table 3).

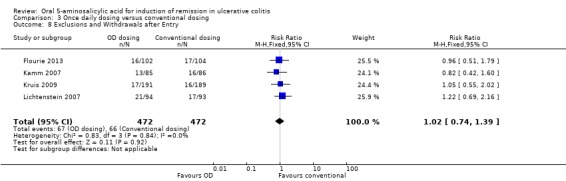

Four studies (n = 738 patients) reported on the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009; Flourie 2013). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry between once daily and conventionally dosed patients. Fourteen per cent of patients dosed once daily patients were excluded or withdrawn after entry compared to 14% of conventionally dosed patients (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.39; I2 = 0%; P = 0.92). Common adverse events included flatulence (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007), abdominal pain (Kamm 2007; Flourie 2013), nausea (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Flourie 2013), diarrhea (Lichtenstein 2007), nasopharyngitis (Kruis 2009), dyspepsia (Lichtenstein 2007), headache (Kamm 2007; Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009; Flourie 2013) and worsening ulcerative colitis (Lichtenstein 2007; Kruis 2009; Flourie 2013).

5‐ASA versus Comparator 5‐ASA

Nine studies (n = 1576 patients) reported the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event (Kruis 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Forbes 2005; Marakhouski 2005; Gibson 2006; Ito 2010). The overall pooled relative risk showed no difference in the incidence of adverse events between various formulations of 5‐ASA (including Balsalazide, Pentasa, Olsalazine, Ipocol and 5‐ASA micropellets) and comparator formulations of 5‐ASA (including Asacol, Claversal and Salolafk). Forty‐six per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group experienced at least one adverse event compared to 46% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.12; I2 = 10%; P = 0.81). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event) was moderate due to a high risk of bias (lack of blinding) in one study in the pooled analysis (See Table 4).

Nine studies (n = 1489 patients) reported the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse event (Kruis 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Forbes 2005; Marakhouski 2005; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010). The overall pooled relative risk showed no difference in withdrawal due to adverse events between various formulations of 5‐ASA (including Balsalazide, Pentasa, Olsalazine, MMX mesalazine; Ipocol and 5‐ASA micropellets) and comparator formulations of 5‐ASA (including Asacol, Claversal and Salolafk). Four per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group were withdrawn due to adverse events compared to 4% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group (RR 0.94: 95% CI 0.57 to 1.54; I2 = 15%; P = 0.79). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome (the proportion of patients withdrawn due to adverse events) was moderate due to sparse data (57 events; See Table 4).

Ten studies (n = 1574 patients) reported the proportion of patients excluded or withdrawn after entry (Kruis 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Forbes 2005; Marakhouski 2005; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007; Ito 2010). The overall pooled relative risk showed no difference in exclusions or withdrawals after entry between various formulations of 5‐ASA (including Balsalazide, Pentasa, Olsalazine, MMX mesalazine; Ipocol and 5‐ASA micropellets) and comparator formulations of 5‐ASA (including Asacol, Claversal and Salolafk). Eighteen per cent of patients in the 5‐ASA group were excluded or withdrawn after entry compared to 18% of patients in the 5‐ASA comparator group (RR 0.99: 95% CI 0.80 to 1.22; I2 = 0%; P = 0.91)

Common adverse events included headache (Green 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007), abdominal pain (Green 1998; Kruis 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Tursi 2004; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007), nausea (Green 1998; Kruis 1998; Levine 2002; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Gibson 2006; Kamm 2007), flatulence (Kruis 1998; Pruitt 2002; Raedler 2004; Kamm 2007) diarrhea (Kruis 1998), nasopharyngitis (Gibson 2006; Ito 2010), dyspepsia (Green 1998; Kruis 1998), vomiting (Green 1998; Kruis 1998; Pruitt 2002) and worsening ulcerative colitis (Levine 2002).

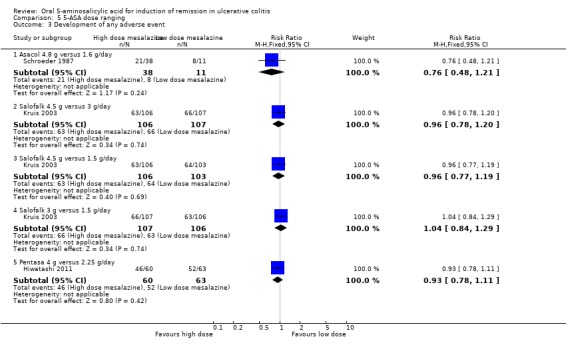

5‐ASA Dose Ranging

Three dose‐ranging studies reported the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event (Schroeder 1987; Kruis 2003; Hiwatashi 2011). Kruis 2003 found no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event between Salofalk 4.5 g/day compared to 3 g/day (213 patients; RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.20) 1.5 g/day (212 patients; RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.19) or between 3 g and 1.5 g/day (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.29). Hiwatashi 2011 found no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event between Pentasa 4 g/day and 2.25 g/day (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.11). Schroeder 1987 found no statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event between Asacol 4.8 g/day and 1.6 g/day (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.21).

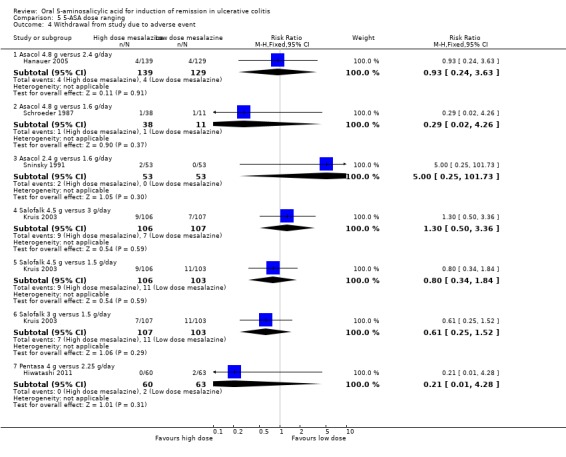

Five dose‐ranging studies reported the proportion of patients who were withdrawn due to adverse events (Schroeder 1987; Sninsky 1991; Kruis 2003; Hanauer 2005; Hiwatashi 2011). No statistically significant differences in withdrawal due to adverse events were found between Asacol 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.24 to 3.63); Asacol 4.8 g/day and 1.6 g/day (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.02 to 4.26); Asacol 2.4 g/day and 1.6 g/day (RR 5.00; 95% CI 0.25 to 101.73); Salofalk 4.5 g/day and 3 g/day (RR 1.30; 95% CI 0.50 to 3.36); Salofalk 4.5 g/day and 1.5 g/day (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.84); Salofalk 3 g/day and 1.5 g/day (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.25 to 1.52); and Pentasa 4 g/day and 2.25 g/day (RR 0.21; 95% CI 0.01 to 4.28).

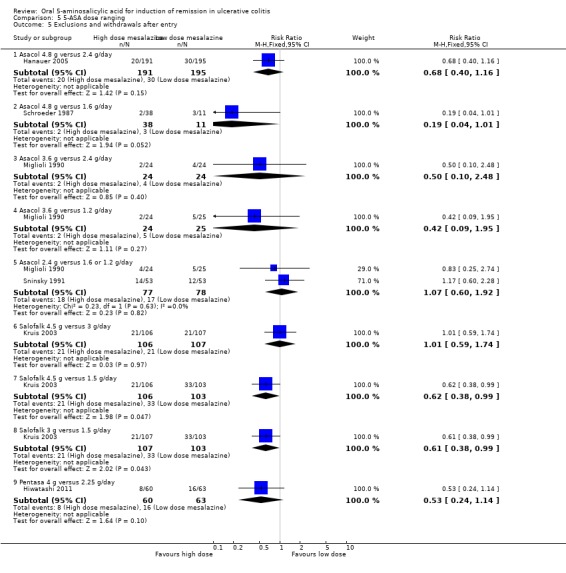

Six dose‐ranging studies reported the proportion of patients who were excluded or withdrawn after entry (Schroeder 1987; Miglioli 1990; Sninsky 1991; Kruis 2003; Hanauer 2005; Hiwatashi 2011). A statistically significant difference was found between Salofalk 3 g/day and 1.5 g/day (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.99). No other statistically significant differences were found in exclusions or withdrawals after entry between Asacol 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.40 to 1.16); Asacol 4.8 g/day and 1.6 g/day (RR 0.19; 95% CI 0.04 to 1.01); Asacol 3.6 g/day and 2.4 g/day (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.10 to 2.48); Asacol 3.6 g/day and 1.2 g/day (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.09 to 1.95) Asacol 2.4 g/day and 1.6 or 1.2 g/day (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.92); Salofalk 4.5 g/day and 3 g/day (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.74); Salofalk 4.5 g/day and 1.5 g/day (RR 0.62; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.99); and Pentasa 4 g/day and 2.25 g/day (RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.14).

The most common adverse event reported in the D'Haens 2006 study was headache. Other less frequent adverse events included diarrhea, nausea and abdominal pain. Adverse events for the Kamm 2007 study which included two different dose groups for once daily MMX mesalamine (2.4 g/day and 4.8 g/day), an Asacol reference arm and a placebo group are reported above.

Discussion

This systematic review largely confirms the results of previous meta‐analyses (Sutherland 1993; Sutherland 1997; Sutherland 2006b; Feagan 2012), but differs from the previous work in a variety of aspects. The 2006 version of this review included 21 studies and 2124 patients. The 2012 version of this review included 48 studies and 7776 patients. This updated review includes new data from five studies. Three of the new studies compared 5‐ASA to placebo, one study compared SASP to 5‐ASA and one study compared once daily 5‐ASA to a conventional dosing regimen. The updated review includes 53 studies and 8548 patients which greatly increases statistical power. Whenever possible the data concerning complete remission versus improvement/remission were separated. Different quality assessment criteria (i.e. the Cochrane risk of bias tool) were used in the current and 2012 version of the review. The current and the 2012 version of the review also utilized the GRADE criteria (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011) to assess the overall quality of the data obtained from the randomized studies included in the review.

Unfortunately, there are some limitations to making general conclusions. Almost every study utilized a unique clinical or endoscopic index. Unlike Crohn's disease, the lack of standard indices in ulcerative colitis prevented the collection of consistent treatment efficacy data and makes comparisons across clinical studies difficult. The use of endoscopic remission as an outcome would provide a more rigorous assessment of treatment efficacy in clinical trials. Clinicians should use a standardized approach to assess endoscopic appearance to allow for comparisons across trials. Most of the included studies were not of sufficient duration to permit documentation of endoscopic healing. As well, results were periodically obscured in several studies that failed to specify the treatment arm to which certain excluded patients were initially randomised. Despite these and other common factors that must be considered when interpreting meta‐analyses, the data provided strong evidence that pointed towards a number of conclusions.

The effectiveness of oral 5‐ASA preparations for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate active ulcerative colitis was confirmed. Oral 5‐ASA is superior to placebo for induction of remission and clinical improvement in patients with active mild to moderate ulcerative colitis.The number needed to treat in order for one patient to benefit from treatment is nine patients. The quality of the placebo‐controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and the possibility of bias was rated as low for these studies. The outcomes induction of remission and clinical improvement were rated as 'high' and 'moderate' respectively using the GRADE criteria indicating that further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the point estimates of effect. In support of our previous conclusions, we observed the dose‐responsiveness of 5‐ASA when compared to placebo. The efficacy of oral 5‐ASA increases with dose. The trend was significant in terms of global/clinical improvement (including remission), but only marginally significant when the rate of complete global/clinical remission was evaluated.

As was found in our previous meta‐analysis, there was a non‐significant trend in favour of a slight benefit for the newer 5‐ASA preparations over SASP for the induction of global/clinical and endoscopic improvement (including remission). There are several points to be considered. It is possible that larger sample populations would confirm the significance of this finding, but the clinical relevance of such a difference would be debatable. Another possible explanation for the difference may be related to our use of the intention‐to‐treat principle which should benefit medications with lower dropout rates, in this case, 5‐ASA. The quality of the SASP‐controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and the possibility of bias was rated as low for these studies. The outcomes induction of remission and clinical improvement were rated as 'moderate' (due to sparse data) and 'high' respectively using the GRADE criteria indicating that further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the point estimates of effect.