Abstract

Background

People with heart failure report various symptoms and show a trajectory of periodic exacerbations and recoveries, where each exacerbation event may lead to death. Current clinical practice guidelines indicate the importance of discussing future care strategies with people with heart failure. Advance care planning (ACP) is the process of discussing an individual's future care plan according to their values and preferences, and involves the person with heart failure, their family members or surrogate decision‐makers, and healthcare providers. Although it is shown that ACP may improve discussion about end‐of‐life care and documentation of an individual's preferences, the effects of ACP for people with heart failure are uncertain.

Objectives

To assess the effects of advance care planning (ACP) in people with heart failure compared to usual care strategies that do not have any components promoting ACP.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Social Work Abstracts, and two clinical trials registers in October 2019. We checked the reference lists of included studies. There were no restrictions on language or publication status.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ACP with usual care in people with heart failure. Trials could have parallel group, cluster‐randomised, or cross‐over designs. We included interventions that implemented ACP, such as discussing and considering values, wishes, life goals, and preferences for future medical care. The study participants comprised adults (18 years of age or older) with heart failure.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted outcome data from the included studies, and assessed their risk of bias. We contacted trial authors when we needed to obtain missing information.

Main results

We included nine RCTs (1242 participants and 426 surrogate decision‐makers) in this review. The meta‐analysis included seven studies (876 participants). Participants' mean ages ranged from 62 to 82 years, and 53% to 100% of the studies' participants were men. All included studies took place in the US or the UK.

Only one study reported concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care, and it enrolled people with heart failure or renal disease. Owing to one study with small sample size, the effects of ACP on concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care were uncertain (risk ratio (RR) 1.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91 to 1.55; participants = 110; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence). It corresponded to an assumed risk of 625 per 1000 participants receiving usual care and a corresponding risk of 744 per 1000 (95% CI 569 to 969) for ACP. There was no evidence of a difference in quality of life between groups (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.06, 95% CI –0.26 to 0.38; participants = 156; studies = 3; low‐quality evidence). However, one study, which was not included in the meta‐analysis, showed that the quality of life score improved by 14.86 points in the ACP group compared with 11.80 points in the usual care group.

Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes may have increased (RR 1.68. 95% CI 1.23 to 2.29; participants = 92; studies = 2; low‐quality evidence). This corresponded to an assumed risk of 489 per 1000 participants with usual care and a corresponding risk of 822 per 1000 (95% CI 602 to 1000) for ACP. One study, which was not included in the meta‐analysis, also showed that ACP helped to improve documentation of the ACP process (hazard ratio (HR) 2.87, 95% CI 1.09 to 7.59; participants = 232).

Three studies reported that implementation of ACP led to an improvement of participants' depression (SMD –0.58, 95% CI –0.82 to –0.34; participants = 278; studies = 3; low‐quality evidence). We were uncertain about the effects of ACP on the quality of communication when compared to the usual care group (MD –0.40, 95% CI –1.61 to 0.81; participants = 9; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence). We also noted an increase in all‐cause mortality in the ACP group (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.67; participants = 795; studies = 5).

The studies did not report participants' satisfaction with care/treatment and caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Authors' conclusions

ACP may help to increase documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes, and may improve an individual's depression. However, the quality of the evidence about these outcomes was low. The quality of the evidence for each outcome was low to very low due to the small number of studies and participants included in this review. Additionally, the follow‐up periods and types of ACP intervention were varied. Therefore, further studies are needed to explore the effects of ACP that consider these differences carefully.

Plain language summary

Advance care planning for adults with heart failure

Review question

To investigate how strategies of advance care planning (ACP) affect people with heart failure.

Background

People with heart failure present with various symptoms, such as breathlessness and fatigue, and symptoms are often complicated with periodic exacerbations and recoveries. Current clinical guidelines emphasise the importance of discussing future care with people with heart failure as well as their families. Advance care planning (ACP) is the process of discussing an individual's future care plan (e.g. the type of care/treatment that the individual prefers to receive, the environment or setting where the care/treatment takes place) according to their values and preferences. This interaction involves the individual, the responsible healthcare providers, family members, and other immediate carers/supporters. ACP may improve discussion about a patient's future care and documentation of an individual's preferences regarding care. However, it is unclear whether ACP is beneficial in improving quality of life, depression, and overall satisfaction with care among people with heart failure.

Study characteristics

In October 2019, we searched for studies assessing the effects of ACP in people with heart failure. We included studies that delivered ACP, which included different methods such as discussion and consideration of individuals' values and preferences on future care and medical treatment compared to usual care strategies.

Key results

This review included nine studies involving 1242 participants and 426 families/carers. Data from seven studies (876 participants) showed that ACP may increase completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes and may improve depression of participants. All‐cause mortality might be increased in participants receiving ACP. The effects of ACP on quality of life remained uncertain due to the inclusion of small studies in our meta‐analysis. This is further illustrated by the fact that only one study reported whether the received end‐of‐life care met participants' preferences. Similarly, only one study reported the quality of communication during ACP between participants and healthcare providers. Therefore, the effects of ACP on whether end‐of‐life care met participants' preferences and on quality of communication were uncertain. None of the studies evaluated satisfaction with care.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence was low/very low. Since the number of studies and patients in this review was small, the effects of ACP were limited. There is clearly a need for high‐quality evidence from large studies to fully explore the effects of ACP for people with heart failure, in particular their quality of life and whether end‐of‐life care received after ACP actually meet their preferences.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Advance care planning compared with usual care for patients with heart failure.

| Advance care planning compared with usual care for patients with heart failure | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with heart failure with or without their surrogate decision‐makers/carers Settings: inpatient and outpatient hospitals and clinics Intervention: ACP Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | ACP | |||||

|

Concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care (yes/no) Post‐death data: mean days to death, ACP group (388.8 ± 255.7); usual care group (362.2 ± 288.4) |

625 per 1000 | 744 per 1000 (569 to 969) | RR 1.19 (0.91 to 1.55) | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — |

|

Participants' quality of life Measured by EQ‐5D and KCCQ. Higher scores indicate high‐quality of life. Follow‐up: 2 weeks to 6 months |

The quality of life score in the ACP groups was on average 0.06 SDs higher (0.26 lower to 0.38 higher) than in the usual care groups. | — | 156 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | 1 additional study reported quality of life using the MLHF Questionnaire. The study showed that the quality of life score was improved by 14.86 points in the intervention group compared with 11.80 points in the usual care group at 3 months. Generally, 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large. |

|

| Patients' satisfaction with care/treatment (yes/no) | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported. |

|

Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes (yes/no) Follow‐up: 3–6 months |

489 per 1000 | 822 per 1000 (602 to 1000) | RR 1.68 (1.23 to 2.29) | 92 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,e | 1 additional study reported completion of documentation with HR (HR 2.87, 95% CI 1.09 to 7.59; P = 0.033). |

|

Participants' depression Measured on PHQ‐8, PHQ‐9, and HADS. Higher scores indicate high depression Follow‐up: 2 weeks to 6 months |

The depression score in the ACP groups was on average 0.58 SDs (0.82 to 0.34) lower than in the usual care groups. | — | 278 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,e |

Generally, 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large. | |

| Caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment (yes/no) | — | — | — | — | — | Outcome not reported. |

|

Quality of communication Measured on Quality of Patient‐Clinician Communication About End‐of‐Life Care. Higher score indicates high satisfaction with the quality of communication Assessed after intervention |

11.2 ± 0.8 (mean ± SD) | MD 0.4 lower (1.61 lower to 0.81 higher) |

— | 9 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,f | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACP: advanced care planning; CI: confidence interval; EQ‐5D: EuroQol‐5D; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Survey; HR: hazard ratio; KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MD: mean difference; MLHF: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate‐quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low‐quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low‐quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for indirectness because the study included participants other than people with heart failure.

bSince the outcome included only one study, the sample size was too small, and had wide confidence intervals. Therefore, we downgraded two levels for imprecision.

cDowngraded one level for risk of bias because most included studies showed unclear selection bias and high attrition bias.

dDowngraded one level for imprecision due to small sample size and wide confidence intervals.

eDowngraded one level for imprecision due to small sample size.

fDowngraded one level for risk of bias due to high risk of selection bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome that is associated with various symptoms including dyspnoea, fatigue, peripheral oedema, and depression (Falk 2013; Ponikowski 2016). The condition is caused by any structural cardiac disorder, functional cardiac disorder, or both, affecting the ability of the ventricles to pump blood (Yancy 2013). Coronary heart disease, heart valve disease, arrhythmias, familial cardiomyopathy, toxin‐induced cardiomyopathy, and hypertension are all linked to heart failure (Ponikowski 2016; Yancy 2013). Heart failure is classified using the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) stages or the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification system (Ponikowski 2016; Yancy 2013). The ACCF/AHA stages are based on structural heart changes, and focus on the development and progression of disease (Ponikowski 2016; Yancy 2013). In contrast, the NYHA functional classification describes the severity of symptoms and exercise capacity (Ponikowski 2016; Yancy 2013).

Incidence of heart failure is more common with increasing age (Redfield 2003; Yancy 2013), and is a worldwide public health problem. In 2015, the worldwide prevalence of heart failure was estimated to be approximately 40 million people (GBD 2016). In 2013, approximately 17.3 million people died from cardiovascular disease globally (Benjamin 2017). People with heart failure are often linked to a trajectory of periodic exacerbations and recoveries, where each exacerbation event may lead to death (Lynn 2001). The mortality rate is high for such people, however, and estimating a prognosis is challenging. When a person's medical condition worsens, in many cases, they require urgent and intensive management (Allen 2012). In this situation, people with heart failure and their families might not be able to contemplate treatment and care options that take into account the person's values and care preferences. Therefore, the AHA has emphasised the importance of discussing with patients via advance care planning (ACP) to better co‐ordinate future healthcare management based on the patient's values and preferences, as well as their current clinical status such as symptom burden and quality of life, potential treatment options, and prognosis, as part of an annual heart failure review (Allen 2012). Currently, the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure recommends palliative and supportive care for people with advanced heart failure to improve quality of life (class I recommendation; level of evidence B) (Yancy 2013). Some systematic reviews have collectively shown that ACP may lead to improvement of communication between patients and healthcare providers, satisfaction with care, and concordance between a patient's preferences of care and received care (Houben 2014; Martin 2016; Weathers 2016).

Description of the intervention

ACP is the process of discussing an individual's future care plan between the person, their family members, surrogate decision‐makers, and healthcare providers while considering the person's values, concerns, wishes, life goals, and preferences for future medical care (NCPC 2007; Rietjens 2017; Sudore 2017). This generally occurs while the person is still able to communicate their wishes independently and is in a stable symptoms and clinical condition of heart failure (Stevenson 2015). In hospital, ACP may start when individuals are diagnosed with heart failure or make an outpatient visit (Mullick 2013; Stevenson 2015). Additionally, the topic of ACP can be broached when patients undergo repeat hospitalisations for exacerbated comorbidities and move into extended care facilities (Stevenson 2015). The discussion component of ACP may include an individual's family members, surrogate decision‐makers (such as friends and neighbours), and key people who are involved in their care (NCPC 2007; Sudore 2017), since they best understand the person's values, goals, and care preferences (Sudore 2017). In the event that the person loses their capacity to make informed decisions, it becomes the responsibility of the surrogate decision‐makers to direct medical care in keeping with the person's wishes, and with an understanding of their illness and prognosis (NCPC 2007; Sudore 2010; Sudore 2017). The aim of ACP, therefore, is to ensure that the care a person receives is consistent with their goals, values, and preferences (Sudore 2017).

In 1990, the Patient Self‐Determination Act was enacted in the USA, and highlighted the rights of patients in the shared decision‐making of their own medical treatment (Allen 2012; Prendergast 2001; Stevenson 2015). In 2005, the Mental Capacity Act was enacted in the UK, and it also emphasised the importance of patients' rights in decision‐making (Hayhoe 2011; NCPC 2007). Discussion about ACP has since been facilitated worldwide. Initially, ACP focused on specific treatment decisions (Prendergast 2001), as well as formal documents. For example, advance directives, shared decision‐making, living wills, power of attorney, physician orders for life‐sustaining treatment, and do‐not‐resuscitate orders are commonly used to legally appoint a spokesperson for the patient and record their wishes about future medical treatment. Although these documents continue to be a part of ACP, the process has evolved to emphasise the importance of communication and understanding between the patient, their family members, and healthcare providers regarding the individual's values, wishes, and preferences for future care (Prendergast 2001; Rietjens 2017; Sudore 2017).

Although heart failure is sometimes stable for a long time, it may change suddenly (Mullick 2013). It is, therefore, important to discuss ACP not only when heart failure is exacerbated, but early in the disease process (Mullick 2013). In addition, because a person's values and preferences can change over time, it is also important to regularly review advance care plans (Sudore 2010).

How the intervention might work

People with heart failure report various symptoms, however, they often have a poor understanding of their disease, and they rarely realise the terminal nature of their condition (Browne 2014). An ACP approach that involves communicating and understanding an individual's values, life goals, and wishes can lead to agreement between patients and their surrogate decision‐makers concerning future care preferences (Lorenz 2008). In addition, supportive physician behaviours and shared decision‐making are associated with patient and family satisfaction with care (Fine 2010). ACP can also help to resolve differences of opinion among family members (Rhee 2013), assist families to face end‐of‐life scenarios, and reduce their psychological and physical distress (Rhee 2013). In people with cancer and their families, ACP is associated with fewer patients receiving aggressive medical interventions as end‐of‐life treatment (Wright 2008). Such aggressive medical interventions can result in lower quality of life for patients in end‐of‐life care and can intensify depressive disorders among distressed family members (Wright 2008). Therefore, implementation of ACP and effective communication among patients, family members, and healthcare providers might lead to or contribute to positive outcomes.

Why it is important to do this review

Healthcare providers can play a vital role in the care of patients with advanced heart failure by discussing a patient's values, preferences, and planning for future care (Allen 2012). The current guideline from the ACCF/AHA recommends the implementation of palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure (class I recommendation; level of evidence B) (Yancy 2013). The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline recommends that, as a key component of palliative and end‐of‐life care, healthcare providers should focus on improving or maintaining quality of life of patients and their carers until death (Ponikowski 2016). Despite both the USA and European guidelines' recommendations of ACP, many people with heart failure do not have documented ACP (Butler 2015).

Barriers to ACP for healthcare providers include the unpredictable trajectory of heart failure, the difficulty in determining when to initiate ACP, and patients' poor understanding of their disease (Browne 2014; De Vleminck 2014; Hjelmfors 2014). However, despite the unpredictable prognosis of disease, healthcare providers need to understand and discuss with patients the patients' own values and preferences for future care, while revising their expectations of the disease course (Allen 2012). Moreover, patients and their families emphasise that effective communication, in particular focusing on the patient's treatments and future care options, are important elements (Virdun 2015).

An existing Cochrane Review explores the effects of ACP for participants receiving haemodialysis (Lim 2016). This review suggested that indepth discussion regarding end‐of‐life care did not lead to unnecessary discomfort or anxiety (Lim 2016). The review's included studies also reported that the surrogate decision‐makers' understanding of the patient's goals and preferences for future medical treatment increased after the implementation of ACP. Additionally, ACP intervention improves the proportion of patients completing advance care directives (Lim 2016). Two other reviews, one of people aged 65 years of age and older (Weathers 2016), and another of adults with various diseases such as cancer, cardiac diseases, and chronic renal failure (Houben 2014), suggested that ACP interventions might improve documentation of end‐of‐life care preferences and increased discussion about end‐of‐life care between patients and healthcare providers.

Although the aforementioned systematic reviews investigated the effects of ACP, none studied the effects of ACP in people with heart failure. Little is known about the impact of ACP on the physical and psychological conditions, quality of life, and care satisfaction of people with heart failure, their families, and carers. Therefore, a review aiming to reveal the effects of ACP for people with heart failure is warranted.

Objectives

To assess the effects of advance care planning (ACP) in people with heart failure compared to usual care strategies that do not have any components promoting ACP.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including randomised parallel‐group trials, cross‐over trials, and cluster‐randomised trials. For cross‐over studies, we included only the first‐phase treatment. We imposed no restrictions on publication status or language.

Types of participants

We included adults (18 years of age or older) with a clinical diagnosis of heart failure. We included participants with all types of heart failure (e.g. preserved ejection fraction (diastolic heart failure) or reduced ejection fraction (systolic heart failure)), who were recruited to the trials without a carer, as well as participants who were enrolled with their surrogate decision‐makers/carers by study investigators. If participants of various diagnoses (i.e. besides heart failure) were included, we contacted authors and extracted the data of only participants with heart failure. If we were unable to obtain the data of only participants with heart failure, we included studies if the majority (when the number of participants with heart failure in the study was highest, and it accounted for almost half of participants) of participants had a diagnosis of heart failure and we pursued a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of mixed diagnoses on the effectiveness of ACP (Sensitivity analysis).

Types of interventions

We included trials that implement ACP practices, such as discussing and considering participants' values, wishes, and life goals; understanding participants' illness and prognosis; and their preferences about future medical care. We compared the ACP intervention with usual care that did not involve any components to promote ACP. Although the current guidelines recommended the implementation of palliative and supportive care including ACP, there was no standardised approach of ACP. Therefore, we included trials that aimed to assess the effectiveness of interventions to promote, improve, or strengthen ACP. We included interventions that involved video or websites to promote ACP. These tools may provide information required for ACP such as resuscitation measures, and may educate patients and their families about the importance of communication about a patient's own values, life goals, and preferences about future medical care between patients, their families, surrogate decision‐makers, and healthcare providers. The eligibility criterion was any study that described an ACP intervention as defined by the trial investigators.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care (measurement defined by trial authors, e.g. comparing end‐of‐life care that participants received with participant‐stated preferences) (yes/no).

Participants' quality of life (e.g. Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), the 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), or other measurement scales, as defined by trial authors).

Participants' satisfaction with care/treatment (measurement defined by trial authors) (yes/no).

Secondary outcomes

Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes (yes/no).

Participants' depression (measurement defined by trial authors, e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9)).

Caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment (measurement defined by trial authors) (yes/no).

Quality of communication (measurement defined by trial authors, e.g. Quality of Communication (QOC) questionnaire).

Use of life‐sustaining treatment, such as intubation (yes/no).

Participants' decisional conflict (measurement defined by trial authors, e.g. Decisional Conflict Scale).

Use of hospice services (yes/no).

All‐cause mortality.

We were interested in effects of the intervention from the longest follow‐up duration; however, the numerous outcome measures were obtained at different time points in patients with serious illness, and thus we also considered the effects of ACP at shorter follow‐up time points where possible and performed subgroup analyses accordingly (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

We did not anticipate ACP to be associated with any adverse effects and thus we decided not to consider adverse effects as a prespecified outcome measure of interest. If adverse effects were reported in the included studies, we decided to describe the findings narratively.

Reporting one or more of the outcomes listed here in the trial was not an inclusion criterion for the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library (2019, Issue 10);

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 8 October 2019; searched 10 October 2019);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2019 week 40; searched 10 October 2019);

CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost, 1937 to 10 October 2019; searched 10 October 2019);

Social Work Abstracts (Ovid, 1977 to 24 October 2019; searched 24 October 2019).

We adapted the preliminary search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) for use in the other databases (Appendix 1). We applied the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter to MEDLINE (Ovid) and adapted it for Embase and CINAHL Plus (Lefebvre 2011).

We conducted a search of the following trial registers for ongoing or unpublished trials:

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; to 21 October 2019);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; to 21 October 2019).

We imposed no restrictions on language of publication or publication status.

We did not anticipate this type of intervention to be associated with any adverse effects and thus did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of ACP.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for additional references to trials. We also examined any relevant retraction statements and errata for included studies.

In the case of unpublished or incomplete data, we contacted the original study authors for further information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (YN screened all titles and abstracts; NH and AM screened by sharing titles and abstracts) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion of all the potential studies identified by the search, and coded them 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. In case of disagreements, a third review author (HF) arbitrated. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publication and two review authors (YN screened all full‐text; NH, HF, and AM screened by sharing the full text) independently screened the full‐text and identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or consulted a third review author (EO). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies table (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form specifically for this Cochrane Review in order to extract relevant information regarding study and population characteristics and outcome data. For consistency during the review development process and to reduce bias and improve validity and reliability, five review authors (YN, NH, HF, AM, MM) first designed the data extraction form by extracting data from a random sample of two studies. We refined/amended the form according to comments or suggestions that arose from the pilot stage before finalising the data extraction form for the full review development process. Two review authors (YN extracted study data from all included studies; NH, HF, AM, and MM extracted study data by sharing the included studies) independently extracted study characteristics and outcome data from the remaining included studies.

We extracted the following study characteristics and reported them in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Methods: study design, total duration of study, number of study centres and location, study setting (community centres, hospices, hospitals, etc.), and date of study.

Participants: number randomised, number lost to follow‐up/withdrawn from studies, number analysed, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition (such as the commonly used classification system, the NYHA Functional Classification; or the ACC/AHA stages of heart failure) and diagnostic criteria (e.g. according to the ESC guideline diagnostic algorithm for diagnosis of heart failure (Ponikowski 2016)), study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention and comparison.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported. Although adverse effects were not our outcome measure of interest, for completeness we also extracted any participant‐ or physician‐reported adverse outcomes in the study publications (Types of outcome measures).

Notes: funding for trial, and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a third review author (EO). One review author (YN) transferred data into the Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second review author (NH) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (YN assessed risk of bias for all of included studies; NH, HF, AM, and MM assessed risk of bias by sharing the included studies) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (EO). We assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs and cluster‐RCTs according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias (e.g. industry funding, lack of individual randomisation).

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Although we had planned to include cluster‐RCTs, our systematic literature search did not identify any eligible ones. Should cluster‐RCTs be included in future updates of this review, we would pay attention to the following sources of bias: recruitment bias; baseline imbalance; loss of clusters; incorrect analysis; and comparability with individually randomised trials (Higgins 2011).

We reported results of our 'Risk of bias' assessment using a 'Risk of bias' summary and a 'Risk of bias' graph, with detailed descriptions of our observations in the Characteristics of included studies table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol (Nishikawa 2018), and reported any deviations in the 'Differences between protocol and review' section of the systematic review.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcome measures, we used risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous endpoints, we used mean differences (MDs) (or standardised mean differences (SMDs) studies used different measuring scales, such as in the case of quality‐of‐life scores) with 95% CIs. We interpreted SMDs based on the approach as illustrated in Cohen 1988.

We stratified analyses by pooling data from measuring scales/scoring systems with a consistent direction of effect. We had planned to analyse the results of the study with the opposite scale (i.e. quality‐of‐life data) separately. However, as we only had one study with a scale in the opposite direction, we reported it narratively.

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with repeated outcome measurements at different follow‐up durations, we included data from the longest follow‐up available. We conducted a subgroup analysis using the longest follow‐up time points for each study, which was divided into short‐term and long‐term follow‐up time points. We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials but did not identify any eligible ones. Should cluster‐randomised trials be included in updates of this review, we plan to analyse their reported data along with those from individually randomised trials. If adjustment for the cluster design effects are missing, we would adjust the relevant summary statistics (such as sample sizes and standard deviations) according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using an estimate of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial, or from a study of a similar population. If we decide to use ICCs from other sources in updates, we would perform sensitivity analyses to test the effects of variation in the ICC.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators or study sponsors in order to verify key study characteristics and obtained missing numerical outcome data where possible (e.g. when a study was identified as abstract only). Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. We used a P value of 0.10 for the Chi2 test for statistical significance and interpreted the I2 statistic according to the following guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

If we had identified substantial heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we would have reported it and explored possible causes by prespecified subgroup analysis. However, none of our analyses had substantial heterogeneity.

We assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visually inspecting forest plots.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we were able to include more than 10 trials, we planned to create and examine a funnel plot to explore possible small‐study biases for the primary outcomes (Higgins 2011). However, since only a small number of studies were eventually included, we did not pursue assessment of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses only if the treatments, participants, and underlying clinical question were similar enough for data pooling. We first used a random‐effects model to pool the studies, and measured the degree of heterogeneity using Tau2 and the I2 statistics. As these results did not indicate substantial heterogeneity, we decided to use the fixed‐effect model.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for the following outcomes (Types of outcome measures).

Concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care.

Participants' quality of life.

Participants' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes.

Participants' depression.

Caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Quality of communication.

Two review authors (YN, NH) independently assessed the overall quality of the evidence and resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving a third review author (EO). We documented and incorporated our corresponding judgements into the reporting of results for each outcome based on the GRADE approach to evaluate the overall quality of evidence and considered the following five GRADE criteria: study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias. We followed methods and recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2015). Our decisions to downgrade the quality of studies are explained in the footnotes of the 'Summary of findings' table and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses for our primary outcomes, if sufficient (stratified) data from included studies allowed for such analyses (Types of outcome measures).

Mean age 70 years or older versus under the age of 70 years.

Gender.

Trial registration status (preregistered in a clinical trial registry, had a published protocol, provided ethics approval, or a combination of these): trials with the above compared to trials without.

Study design (cluster‐RCTs versus parallel RCTs).

Follow‐up periods (defined by trial authors).

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

The incidence and prevalence of heart failure is more common with increasing age (Redfield 2003; Yancy 2013). Since the prevalence of heart failure gradually increases at 70 years of age and older (Gottdiener 2000; Ponikowski 2016; Yancy 2013), we decided a cut‐off at 70 years old.

We conducted a subgroup analysis regarding follow‐up periods for participants' quality of life and participants' depression. The other subgroup analysis which we had planned were not conducted because of lack of data.

Sensitivity analysis

Given that a number of included studies enrolled mixed populations of varied diagnoses, of which only a subset had the diagnosis of interest (heart failure), in addition to the main analysis where we included all participants, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we analysed data from studies that enrolled only participants with the diagnosis of interest, in order to examine the influence of such baseline clinical characteristics on the overall effectiveness of ACP. For updates, we would also consider the possibility of performing a sensitivity analysis by including only studies with an overall low risk of bias (we defined low risk of bias for studies in which we judged at least four domains to be 'low').

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of included studies for this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice and our implications for research suggested priorities for future research and outlined what the remaining uncertainties are in the area.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

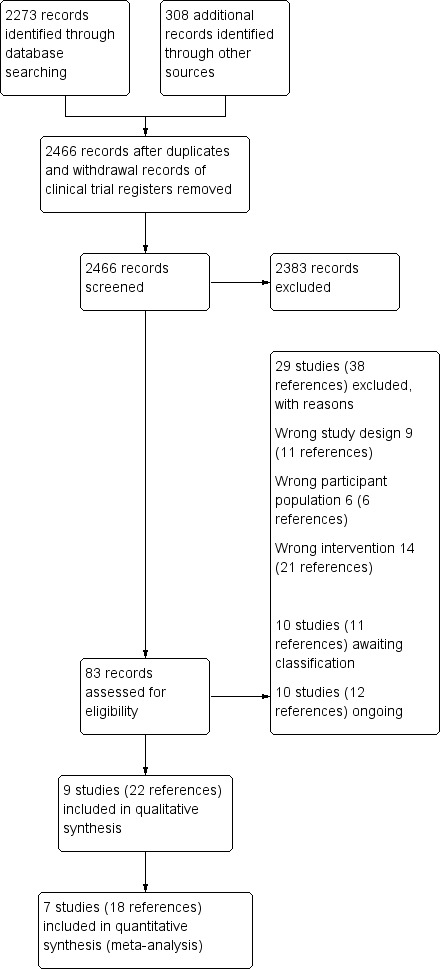

We identified 2273 records through an electronic database search. We also checked reference lists of all included studies and identified 308 additional records. After removing duplicates, 2466 records remained. We assessed the titles and abstracts of these records and excluded 2383. We assessed the remaining 83 records for eligibility, and 29 studies (38 references) were excluded, 10 studies (11 references) were identified as awaiting classification, and 10 studies (12 references) were classified as ongoing. Nine studies (22 references) met the review inclusion criteria, of which seven studies (18 references) were included in the meta‐analyses (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included nine studies involving 1242 patients and 426 patients' surrogate decision‐makers in this systematic review; 1016 people had heart failure. Three of nine studies enrolled participants other than people with heart failure, including people with end‐stage renal disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Briggs 2004; Kirchhoff 2010; Menon 2016). Of these three studies, Menon 2016 did not report any of our prespecified outcomes. For the other two studies, we contacted the trial authors to obtain the outcome data of only people with heart failure. We were able to obtain relevant data from people with heart failure from Briggs 2004; however, although we contacted the trialists of the Kirchhoff 2010 study, we were unable to extract the desired data. Participants of heart failure included in Kirchhoff 2010 accounted for 58.3% of all participants. Therefore, we assessed this study to be eligible for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis, and moreover, we used sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of including a study with a proportion of non‐eligible participants.

We had planned to include cluster‐randomised trials but did not identify any eligible ones.

Participants' mean age ranged from 62.3 to 81.9 years. The proportion of men in each study ranged from 52.7% to 100%. The main inclusion criteria across the included studies were NYHA class III or IV, those who had previous hospitalisation for heart failure within one year, or a predicted poor prognosis. One study focused on participants with left ventricular assist devices (Metzger 2016). Eight studies were implemented in the US (Briggs 2004; El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015), and one study was conducted in the UK (Denvir 2016).

The ACP intervention applied in the included studies consisted of structured discussion, use of tools including video and the Values Inventory, and ACP as a part of palliative care by a multidisciplinary team. Five studies conducted a structured discussion of participants' current clinical condition, prognosis, predictable complications or future treatment, participants' preferences and goals of care, values, concerns, and documentation of preferences (Briggs 2004; Denvir 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018). Of these, four studies conducted the structured discussions with patients and their surrogate decision‐makers or carers (Briggs 2004; Denvir 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Metzger 2016). Trained cardiologists, nurses, social workers, and chaplains facilitated structured discussions. The intervention consisted of one‐time discussions (Briggs 2004; Kirchhoff 2010; Metzger 2016), and multiple times with a follow‐up duration of three to six months (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018). Two studies delivered the intervention via video and the Values Inventory (El‐Jawahri 2016; Menon 2016). The video included an explanation regarding goals of care and treatment about life‐prolonging care, limited medical care, and comfort care. The Values Inventory was used as an ACP discussion aid and to assess participants' own values. Two studies conducted ACP as a part of palliative care by a multidisciplinary team (Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). These participants received palliative care including symptom and psychosocial assessment and management, and they also participated in discussions about ACP. The participants of comparators in the included studies received information about advance directives, ACP materials, or usual care, the details of which were not described.

Four studies assessed the quality of life of participants (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015), and three studies assessed depression (O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). The studies used different tools to assess participants' quality of life and depression (e.g. quality of life was measured using the EuroQol‐5D (EQ5D) instrument, the KCCQ and the MLHFQ.

Although we had planned to describe information on adverse effects and the economic costs associated with ACP narratively, none of the included studies reported such information.

Excluded studies

We excluded 29 studies following the assessment of the full text (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). Fourteen studies' interventions did not meet our criteria regarding types of ACP (Allen 2018; Blue 2001; Doorenbos 2016; Harter 2016; Hjelmfors 2018; Hua 2017; Hughes 2000; McIlvennan 2016; Molloy 2000; NCT01817686; NCT01917188; Ng 2018; Sahlen 2016; Wells 2018). Nine studies were not RCTs (Anonymous 2007; Johnson 2010; Johnson 2018; Miller 1971; Nenner 2012; Newton 2009; Rabow 2004; Svendsen 2006; UMIN000029805). Six studies did not meet our criteria of participant (Detering 2010; Gutheil 2005; Pearlman 2005; Radwany 2014; Skorstengaard 2019; Thoonsen 2015 ). Three studies did not enrol any participants with diagnosed heart failure (Gutheil 2005; Pearlman 2005; Thoonsen 2015). The remaining three studies were excluded owing to ineligibility of participants (Detering 2010; Radwany 2014; Skorstengaard 2019). Detering 2010 included participants of various diagnoses such as respiratory disease; since only a minority of the study population had a diagnosis of heart failure (30%), this study was eventually excluded. Radwany 2014 included various participants other than those with heart failure such as COPD and diabetes with renal disease; there was a lack of information on the rate of each diagnosis among participants. Skorstengaard 2019 included various diagnoses such as cancer and lung disease, and only 17% of participants were patients with heart failure.

Studies awaiting classification

We identified 10 studies as studies awaiting classification (ACTRN12613001377729; ACTRN12618001045202; Hughes 2015; NCT00105599; NCT02463162; NCT03128060; NCT03539510; NCT03649191; O'Riordan 2014; Skorstengaard 2017; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table). Eight studies have not yet been published (ACTRN12613001377729; ACTRN12618001045202; Hughes 2015; NCT00105599; NCT02463162; NCT03128060; NCT03539510; NCT03649191). One study reported in its abstract about the baseline survey of the RCT, however the full‐text has not yet been published (O'Riordan 2014). Further papers are to follow the published Skorstengaard 2017 study. This first paper was a cross‐sectional study describing the place of care and place of death preferred by participants, and their level of anxiety. The second paper was an RCT including a high proportion of patients with conditions other than heart failure. Skorstengaard 2017 plans to publish one more article.

Ongoing studies

We identified 10 ongoing studies (ACTRN12614000590662; ACTRN12617001040358; Ejem 2019; Graney 2019; Malhotra 2016; NCT00489021; NCT02429479; NCT02612688; NCT03170466; NCT03516994; see Characteristics of ongoing studies table). Two studies restricted the study population to participants with diagnosed heart failure (Malhotra 2016; NCT03170466), while the remaining eight studies included participants with different diagnoses such as cancer, COPD, or renal disease.

Risk of bias in included studies

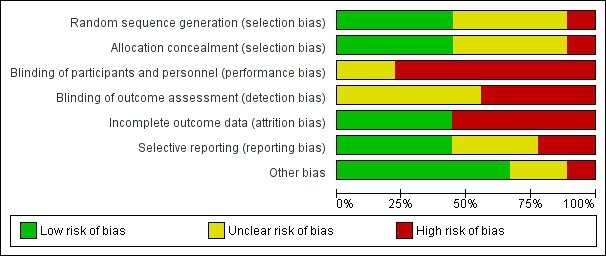

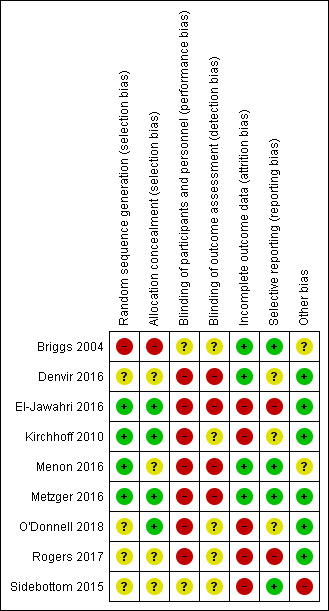

The results of our assessment of risk of bias in the included studies are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

For random sequence generation, four studies were at low risk (El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016). We judged four studies at unclear risk of selection bias due to a lack of sufficient information (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). One study reported the use of alternating group assignment, and we rated it at high risk of selection bias (Briggs 2004).

Four studies reported adequate methods of allocation concealment and we rated them at low risk of bias (El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018). We judged four studies at unclear risk of bias due to insufficient study information (Denvir 2016; Menon 2016; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). One study was at high risk because of predictable allocation (Briggs 2004).

Blinding

As the nature of the ACP intervention involves facilitated discussion with participants, six studies were at high risk of performance bias regarding the blinding of participants and personnel (Denvir 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017). El‐Jawahri 2016 was also assessed at high risk of performance bias because the research assistants showed a video on goals of care to participants as part of the intervention. The other two studies were at unclear risk of performance bias due to insufficient information (Briggs 2004; Sidebottom 2015).

We rated five studies at unclear risk of detection bias in terms of the blinding of outcome assessors due to insufficient information (Briggs 2004; Kirchhoff 2010; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). We judged four studies at high risk (Denvir 2016; El‐Jawahri 2016; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016): Denvir 2016 and Metzger 2016 both employed a structured discussion approach where trial personnel and outcomes were assessed using subjective self‐reported questionnaires; two studies collected outcomes using unblinded research assistants (El‐Jawahri 2016; Metzger 2016), and one study assessed qualitative data about discussions between participants and their physicians (Menon 2016). Metzger 2016 conducted a structured discussion with trial personnel, and outcomes were assessed by a research assistant via telephone.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed four studies at low risk of attrition bias (Briggs 2004; Denvir 2016; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016). We classified the remaining five studies at high risk of attrition bias because of the high rate of loss to follow‐up due to death, withdrawal, refusal by participants' surrogate decision‐makers, or unclear reasons (El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015).

Selective reporting

We rated four studies at low risk of reporting bias because the reported outcomes in the 'Methods' section were described in the 'Results' section of the published papers, or the outcomes that were preregistered in the trial register were reported in the published papers (Briggs 2004; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016; Sidebottom 2015). We judged three studies at unclear risk of reporting bias (Denvir 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; O'Donnell 2018). Although all outcomes of the two studies that were mentioned in the trial register were reported in the published papers, participants' recruitment and enrolment were completed before entry into the trial registry (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018). Kirchhoff 2010 did not report the details of outcome measures in the trial register. We judged two studies at high risk of reporting bias because not all outcomes that were preregistered in the trial register or in the design paper were reported in the published paper (El‐Jawahri 2016; Rogers 2017).

Other potential sources of bias

We rated six studies at low risk of other bias (Denvir 2016; El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017). We judged two studies at unclear risk of other bias (Briggs 2004; Menon 2016). Briggs 2004 showed an imbalance in participants' gender between groups at baseline. However, the effect of gender imbalance on outcomes was uncertain. In Menon 2016, participants were encouraged to have discussions about end‐of‐life care with their physician using the Values Inventory tool, and the contents of the discussions were analysed. Although physicians' characteristics may affect end‐of‐life discussions, the details of physicians' characteristics were not reported. We judged one study at high risk of other bias, because the study showed statistically significant differences between groups at baseline about age (Sidebottom 2015).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1.

Advance care planning versus usual care

Nine studies compared advance care planning with usual care; of these, two studies did not report our prespecified outcomes and thus were not included in our meta‐analyses.

Concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care

One study reported concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care (Kirchhoff 2010). The study included people with heart failure (n = 179; 57.2%) and renal disease (n = 134; 42.8%). Of the 313 participants with heart failure and renal disease, 110 died before the end of the study and their data were included in the analysis of this outcome. Of the 110 decedents, 62 were in the intervention group and 48 were in the control group. In the situation of a low chance of survival, 46/62 (74.1%) participants in the intervention group were consistent with their preferences and received care compared with 30/48 (62%) participants in the control group (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.55; participants = 110; very low‐quality evidence). This corresponded to an assumed risk of 625 per 1000 participants with usual care and a corresponding risk of 744 per 1000 participants (95% CI 569 to 969) for ACP.

Participants' quality of life

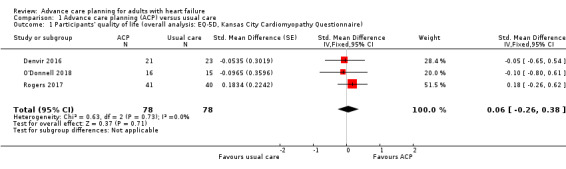

Four studies reported participants' quality of life (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). Three studies reported quality of life using the EQ5D and the KCCQ (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017). Sidebottom 2015 reported quality of life using the MLHF Questionnaire. The MLHF instrument implies that a lower score indicates better quality of life and vice versa, which is opposite to the direction of effect of other quality‐of‐life measuring scales such as the EQ5D and the KCCQ. Although it is possible to align the direction of the MLHF score with EQ5D and KCCQ scores by multiplying by –1 and obtain the consistent direction of effect, we had only one study with a scale in the opposite direction (Sidebottom 2015). In addition, the MLHF has significant differences in the range of the score and the grading policy. Therefore, we decided to conduct a meta‐analysis of three studies (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017), and reported findings of Sidebottom 2015 narratively.

Pooled data analysis on the three studies showed that there was no evidence of a difference in quality of life between ACP and the usual care group (SMD 0.06, 95% CI –0.26 to 0.38; participants = 156; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). The scores were calculated as the degree of changes from the baseline score.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 1 Participants' quality of life (overall analysis: EQ‐5D, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire).

Sidebottom 2015 showed that the mean change of the score in the intervention group was 12.92 points between baseline and one month, and 14.86 points between baseline and three months. In the control group, the mean change was 8.00 points between baseline and one month, and 11.80 points between baseline and three months. The MLHF in the intervention group was improved 4.92 points higher than the control group at one month (P = 0.001), and 3.06 points higher at three months (P = 0.001).

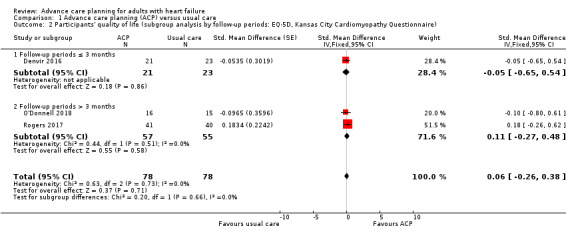

We conducted a subgroup analysis according to the follow‐up duration (three months or less and more than three months). For participants' quality of life, there was no difference by length of follow‐up (test for differences between subgroups P = 0.66; follow‐up duration three months or less: SMD –0.05, 95% CI –0.65 to 0.54; participants = 44; more than three months: SMD 0.11, 95% CI –0.27 to 0.48; participants = 112; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 2 Participants' quality of life (subgroup analysis by follow‐up periods: EQ‐5D, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire).

Participants' satisfaction with care/treatment

None of the included studies reported on participants' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about advance care planning processes

Three studies reported completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Sidebottom 2015). In particular, Sidebottom 2015 assessed the "documented completion of the disease‐specific ACP process in the record within 6 months of the study hospitalization" and calculated the hazard ratio (HR), which was adjusted for age, sex, and marital status (HR 2.87, 95% CI 1.09 to 7.59; P = 0.033); however, the study failed to clearly explain why HR was chosen as an effect measure for completion of ACP documentation.

Pooled data analysis of the other two studies showed that documentation about the ACP process was more often completed in the intervention group compared with the control group (RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.29; participants = 92; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). This corresponded to an assumed risk of 489 per 1000 participants with usual care and a corresponding risk of 822 per 1000 participants (95% CI 602 to 1000) for ACP.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 3 Completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes.

Participants' depression

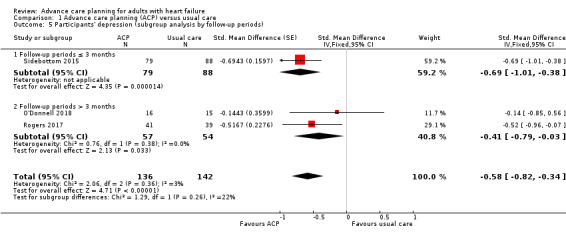

Three studies reported on participants' depression (O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). Depression was reported using the PHQ‐8, the HADS with depression subscale, and the PHQ‐9. Pooled data analysis on the three studies showed that ACP intervention may have improved depression when compared with usual care (SMD –0.58, 95% CI –0.82 to –0.34; participants = 278; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4). The scores were calculated as the degree of changes from the baseline score.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 4 Participants' depression (overall analysis).

We conducted a subgroup analysis according to the follow‐up duration (three months or less and more than three months). Analysis for participants' depression demonstrated that ACP led to improved outcomes in both subgroups, and the test for subgroup differences indicated no difference (three months or less months: SMD –0.69, 95% CI –1.01 to –0.38; participants = 167; more than three months: SMD –0.41, 95% CI –0.79 to –0.03; participants = 111; P = 0.26; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 5 Participants' depression (subgroup analysis by follow‐up periods).

Caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment

We identified no studies reporting caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Quality of communication

One study reported quality of communication which was measured using the Quality of Patient‐Clinician Communication About End‐of‐Life Care (Briggs 2004). We were uncertain about the effects of ACP on the quality of communication when compared to the usual care group (MD –0.40, 95% CI –1.61 to 0.81; participants = 9; very low‐quality evidence).

Use of life‐sustaining treatment

None of the included studies reported use of life‐sustaining treatment, such as intubation.

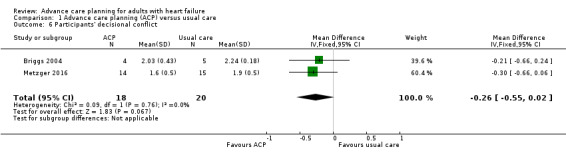

Participants' decisional conflict

Two studies reported participants' decisional conflict using the Decisional Conflict Scale (Briggs 2004; Metzger 2016). Pooled data analysis on the two studies showed no evidence of a difference in participants' decisional conflict between the ACP intervention and usual care group (MD –0.26, 95% CI –0.55 to 0.02; participants = 38; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 6 Participants' decisional conflict.

Use of hospice services

One study reported use of hospice services (Sidebottom 2015). Sidebottom 2015 reported the use of hospice services with HR adjusted for age, sex, and marital status (HR 1.60, 95% CI 0.58 to 4.38; participants = 232). It is unclear why Sidebottom 2015 used an HR as an effect measure for the use of hospice services.

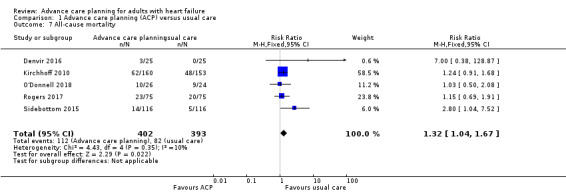

All‐cause mortality

Five studies reported all‐cause mortality (Denvir 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015). Pooled data analysis on the five studies showed that all‐cause mortality might have been increased in participants who received ACP intervention compared with usual care (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.67; participants = 795; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 7 All‐cause mortality.

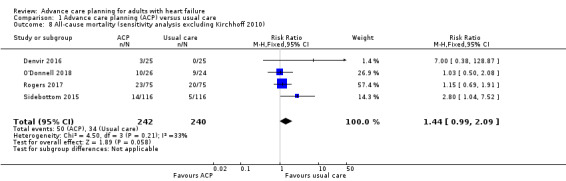

Of these five studies, four studies included only participants with heart failure (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015), and one study enrolled participants with heart failure and participants with renal disease (Kirchhoff 2010). A sensitivity analysis excluding Kirchhoff 2010 was pursued to explore the influence of clinical diagnosis status of study participants on the overall results. Pooled analysis of the four studies enrolling only participants with heart‐failure still showed a higher risk of all‐cause mortality among people who received ACP (RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.09; participants = 482; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Advance care planning (ACP) versus usual care, Outcome 8 All‐cause mortality (sensitivity analysis excluding Kirchhoff 2010).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The main results of this review revealed that the ACP intervention may increase the completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes and may improve individuals' depression compared with usual care. However, the quality of the evidence was low due to small sample sizes, unclear selection bias, and high attrition bias. For depression, there was a statistically significant difference between ACP and usual care (P < 0.00001), with an effect size of –0.58. Although the included evidence was of low quality, due to relatively narrow CIs (–0.82 to –0.34) and a lack of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 3%; P = 0.36 for Chi2), we are confident that this statistically significant finding could also be interpreted as a clinically significant and relevant finding, suggesting that implementation of ACP could lead to at least a moderate level of improvement in depression. The ACP intervention showed no evidence of a difference on participants' quality of life and decisional conflict, but the sample sizes of each study were relatively small and the quality of evidence about quality of life was low.

We are uncertain about the effects of ACP on concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care and quality of communication. Each outcome included only one small study, and the quality of the evidence was very low. The ACP intervention might be associated with a higher risk of all‐cause mortality; our sensitivity analysis by excluding one study that enrolled participants with both heart failure and renal diseases produced a consistently higher risk of all‐cause mortality in the ACP intervention group compared with usual care group. The included studies did not report the outcomes of participants' and caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment and use of life‐sustaining treatment.

The majority of the included studies conducted structured discussions as the ACP intervention, but employed various types of interventions and follow‐up periods: some studies used tools such as video and the Values Inventory to support decision‐making, and other studies had three‐ to six‐month follow‐up periods. Therefore, there were limitations in evaluating the effect of each type of ACP.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Many participants in this review were NYHA class III or IV, had previous heart failure hospitalisation within one year, or a predicted poor prognosis. It is important to discuss ACP early in the disease process and to review ACP regularly (Mullick 2013; Sudore 2010). The AHA also recommended that ACP needs to be discussed and documented (Allen 2012). Since the participants in this review included people with severe heart failure, there were limitations in applying the findings of this review to people with mild heart failure.

Eight out of nine included studies were conducted in the USA (Briggs 2004; El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; Menon 2016; Metzger 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015), and one study was conducted in the UK (Denvir 2016). Previous studies suggested that cultural values and ethnicity may affect general awareness of ACP and acceptability of talking about death (Hong 2018; Ohr 2017). Therefore, careful attention should be paid to this point when applying the findings of this review to a wider range of people with heart failure.

The ACP intervention included structured discussion, the use of tools to understand treatment and care or to promote discussion about ACP, and ACP as a part of palliative care. Therefore, the effect of ACP interventions that use tools such as video and the Values Inventory was uncertain. Furthermore, structured discussion included discussions implemented only once and those with a long‐term follow‐up range of three to six months, including multiple discussions. As each study had a small sample size and the included studies in this review were small, we were unable to show the effect of the ACP intervention based on differences in the number of discussions and each type of ACP. Therefore, there were limitations in generalising the effect of the intervention.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality of the evidence for the main outcomes using the GRADE approach. Since all outcomes had a small sample size, the quality of the evidence for concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care, quality of life, completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes, depression, and quality of communication were downgraded one level. Concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care included only one study (Kirchhoff 2010), and this study included people with congestive heart failure and people with end‐stage renal disease. Therefore, we downgraded the quality of evidence one level due to the indirectness domain, and judged the quality of the evidence to be very low. We judged the quality of the evidence for participants' quality of life, completion of documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants about ACP processes, and participants' depression as low, because the sample size was small and approximately two‐thirds of selection bias and attrition bias was unclear or high. Only one study included quality of communication (Briggs 2004). Since this study had an extremely small sample size of nine participants and a high risk of selection bias, we judged the quality of the evidence as very low. None of the included studies reported patients' satisfaction with care/treatment and caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment.

Potential biases in the review process

We contacted trial authors if there was missing information in the published and unpublished studies. However, we were only able to obtain limited information.

Owing to the nature of ACP and outcomes, the interventions and assessment of outcomes were not blinded to participants and personnel in many trials. Therefore, we considered performance and detection bias as high. Attrition biases were also high because five of nine included trials had incomplete data (El‐Jawahri 2016; Kirchhoff 2010; O'Donnell 2018; Rogers 2017; Sidebottom 2015).

In our review, only nine studies met the inclusion criteria. All trials were small and our primary outcomes were scarcely reported. Therefore, we could not conduct meta‐analyses for two of our three primary outcomes. The power to detect the effect of ACP is currently inadequate.

One source of bias could be the differences in the contents of the intervention to promote ACP among trials. For example, Briggs 2004 and Denvir 2016 mainly provided the scheduled one‐hour interview as the intervention, while El‐Jawahri 2016 utilised a six‐minute video. Furthermore, there were differences in the number of discussion about ACP and the follow‐up duration. Long‐term involvement with patients and healthcare providers might enhance their relationship. It was showed that the therapeutic relationship between patients and healthcare providers may impact on the satisfaction and comfort of discussion about ACP (Miller 2019). The diversity of ACP interventions may affect the effectiveness of the intervention and heterogeneity in future reviews.

Since Kirchhoff 2010 included the study centre which conducted ACP education in the community, effects of intervention might have diminished. Additionally, if colleagues and departments in study centres were interested in ACP, it might have affected the effects of intervention.

The fact that almost all of trials were conducted in the USA could be another source of bias and the effect of ACP should be culturally sensitive. Future trials in other countries or cultural settings could potentially contribute to our review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings showed that the effects of the ACP intervention were uncertain because of low‐ or very low‐quality evidence. One previous systematic review and narrative synthesis reported that the use of hospice services increased with ACP intervention (Kernick 2018). We were unable to conduct a meta‐analysis because the outcome of hospice use was included in only one study in our review (Sidebottom 2015). Sidebottom 2015 indicated that the use of hospice services did not show a significant increase with the ACP intervention. However, since the studies included in Kernick 2018 were part of a cohort study, we were unable to show the effectiveness of the ACP intervention in relation to the use of hospices.

Another systematic review that included participants with various diagnoses besides heart failure reported that the ACP intervention may increase the completion of advance directives (odds ratio 3.26, 95% CI 2.00 to 5.32; participants = 12,012; Houben 2014). The interventions included in Houben 2014 were classified into two types, one focusing on the completion of advance directives and the other focusing on communication about ACP. Completion of advance directives increased in both intervention types. In our review, three studies showed that documentation about ACP processes was more often completed in the intervention group compared with the control group (Denvir 2016; O'Donnell 2018; Sidebottom 2015). Although Houben 2014 included participants with other conditions besides heart failure, it showed findings similar to our review. The ACP intervention may increase ACP documentation for patients with a wide range of diseases.

Houben 2014 also reported that the ACP intervention was able to improve the quality of communication. However, the outcome included only two studies. In our review, only one study reported the quality of communication with a very small sample size (Briggs 2004).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The USA and European guidelines recommend advanced care planning (ACP). In this review, although the quality of evidence was low, we found that the implementation of ACP may promote documentation by medical workers about ACP processes and may lead to improvement in participants' depression. The effect of ACP on concordance between participants' preferences and end‐of‐life care, which was one of the main objectives of ACP, quality of life, quality of communication, and use of hospice services remains unclear. In our review, we were unable to show the effect of the ACP intervention in relation to participants' and caregivers' satisfaction with care/treatment and use of life‐sustaining treatment, because the included studies did not report these outcomes.

Although the sample size of each study was small, our meta‐analysis showed that ACP intervention may increase all‐cause mortality. Patients in the ACP intervention group whose preferences and care plans to not receive invasive and life‐sustaining treatment were followed may have subsequently experienced increased rates of all‐cause mortality. Although we prespecified the use of life‐sustaining treatment as an outcome, none of the included studies reported it. In addition, these studies did not report the reasons for death and types of care received during the end‐of‐life phase. Therefore, the precise rationale behind the effects on all‐cause mortality remains uncertain because it is currently unclear as to the types of medical treatment modalities delivered to the study participants and if participants' preferences of care/treatment were noted and subsequently followed.

The included studies consisted of various ACP interventions, such as structured discussion or ACP as a part of palliative care and different follow‐up periods. The ACP is a process of discussion over time (Stevenson 2015; Sudore 2017). The extent of the relationship between patients and healthcare providers which is related to the follow‐up duration might affect the effects of ACP. Since the follow‐up durations of included studies in this review varied, the effects of long‐term follow‐up interventions remained uncertain.

Some qualitative systematic reviews about ACP for people with cancer and patients with life‐threatening disease showed that patients feel benefit as well as unpleasant feeling on ACP, their perception may change in the ACP process, and relationship with families or therapeutic relationship may also have an effect on the implementation of ACP (Johnson 2016; Zwakman 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to accumulate qualitative studies about patients' and families' experiences of the ACP process as well as quantitative studies about the effects of ACP using effective ACP based on these findings of studies.

Implications for research.

The studies included in this review had small sample sizes. In addition, since the quality of evidence for the main outcomes in this review was relatively low and limited, we need to pay more attention to interpreting the results, and we need further studies to support our conclusion.

It is necessary to confirm whether differences in the severity of heart failure, type of intervention, and follow‐up periods will influence the effect of ACP interventions. Future studies need to